Abstract

Small and medium-sized enterprises around the world play a key role in building economic growth and maintaining environmental sustainability. This strategic role in the economy depends on the possessed competitive advantage, which will increasingly depend on the ecological behavior of SMEs. Therefore, it is justified to undertake research the main goal of which is to identify the pro-ecological activities of SMEs conducive to achieving a competitive advantage. The original empirical research was conducted in 2021 on a sample of 452 small and medium-sized enterprises in Poland. The research was based on a questionnaire. The research allowed for the assessment of sustainable energy management by assessing the awareness of entrepreneurs, assessing the pro-ecological activities undertaken, and assessing the impact of pro-ecological activities on shaping the competitive advantages of enterprises in 2015–2020. The surveyed entrepreneurs considered the most important components of the company’s competitive advantage and sustainable energy management to be those investments aimed at achieving a high input–result ratio in a short time. In order to review the pro-ecological activities in Poland against the background of international data, other research results in this area are presented. The cited data confirm the results of the conducted extensive survey research. In the case of many countries and SMEs, environmental awareness is relatively low. Where it occurs, it is not translated into real activities in the field of sustainable energy management in the absence of economic efficiency.

1. Introduction

Competitiveness is the driver of the global economy and a strategic priority for almost every business owner. The ability to maintain a good competitive position is also the greatest challenge of the 21st century. This statement is invariably true, especially in the cases of small and medium-sized enterprises, the functioning of which largely determines the business cycle. The direct inspiration for writing this article was the megatrends that have been observed for many years, dominating the socio-economic space, which are well summarized in the conclusions of experts presented in The Global Risk Report in 2021. In the Report published by the World Economic Forum, extreme weather events ranked first among the most serious threats in the world for the next 10 years, followed by the failure of climate-related activities, and then by environmental damage. The next places are held by infectious diseases (which can be explained by the current situation related to the COVID-19 pandemic) and the loss of biodiversity [1]. Therefore, the most serious threats in the world are related to non-compliance with the principles of sustainable development (including sustainable energy management). An additional argument in favor of undertaking research in this area is the significant role of small and medium-sized enterprises in the economy, measured by their roles in generating GDP, in adding value and in employment.

The proposed combination of shaping the competitive advantage of enterprises with pro-ecological activities and enacting sustainable energy management is innovative, and thus fills a certain gap in the theoretical and empirical research on competitiveness. Recent research on SMEs has focused on one of these areas, and most concerns production enterprises [2], or applies to all EU enterprises and does not take into account the specificity of SMEs in Poland [3].

The main aim of this research is to identify the pro-ecological activities of SMEs that are conducive to achieving a competitive advantage.

The subsidiary goals were formulated as follows:

- Auxiliary objective 1—Assessment of entrepreneurs’ awareness of environmental protection;

- Auxiliary objective 2—Assessment of pro-ecological activities undertaken by entrepreneurs;

- Auxiliary objective 3—Assessment of the impact of pro-ecological activities on shaping the competitive advantage of enterprises.

As part of the theoretical and empirical research, the main hypothesis and three detailed hypotheses will be verified. The main hypothesis was formulated as follows: pro-ecological activities can be an important element in shaping the competitive advantage of small and medium-sized enterprises and a sustainable energy economy.

In contrast, the auxiliary hypotheses were defined as follows:

- Auxiliary hypothesis 1—Entrepreneurs from the SME sector are aware of the need to take actions in the field of environmental protection;

- Auxiliary hypothesis 2—Entrepreneurs from the SME sector undertake more important pro-ecological activities than the competition;

- Auxiliary hypothesis 3—Pro-ecological activities undertaken by entrepreneurs from the SME sector have a significant impact on the competitiveness of enterprises.

This research was carried out via a classic scheme: theoretical research (concepts of competitive advantage, theory of pro-ecological activity of enterprises), empirical research (primary and secondary), and conclusions. The primary research was carried out among SMEs in Poland. This was complemented by studies of secondary data for all EU countries. This allowed for international comparisons and drawing conclusions that may apply to all EU countries.

2. Classic Concepts of Competitive Advantage

The concept of a competitive advantage in economic theory emerged relatively slowly, and was the result of growing interest in distinguishing between market entities. Among the pioneers of the concept of “competitive advantage” is W. Alderson, who in 1937 pointed out that “the key aspect of adapting to competitive conditions is the specialization of enterprises in order to meet diversified demand” [4]. W. Alderson recognized (but only in 1965) that economic operators should strive to acquire features that distinguish them from their competitors. The way to achieve the so-called differential advantage was supposed to be as follows: advertizing, product/service innovations, lowering prices. In 1980, W. Alderson’s theses were empirically confirmed by W.K. Hall. He stated that a company’s survival and development is determined by them holding one of two positions: the lowest cost position, or the most differentiated position [5]. The new concept was introduced in 1983 by B.D. Henderson, who wrote about unique advantage [6]. In his concept, he referred to Darwin’s theory of the origin of species by comparing competition in the market to competition between species.

The exact concept of competitive advantage was introduced by the positional school, which emerged as another trend in strategy theory. According to this trend, “the essence of the strategy is to achieve a competitive advantage” [7]. This school focuses on building techniques and methods for analyzing the company and its environment. The information collected in this way is passed on to entities of strategic management. The essence of the strategy is gaining a competitive advantage, i.e., developing the technique of being a market leader so that the company is highly competitive. The sources of competitive advantage were to be [8]:

- The optimization of production decisions consisting of determining such a production volume that would guarantee the most favorable level of stocks;

- Economies of scale, occurring in relation to types of activity related to reductions in unit costs along with jumps in the production volume [9];

- Economy of scope, based on the benefits derived from the elements of many products, and occurring when a wide range is offered (created as a result of segmentation, based on a broad analysis of buyers’ needs), enabling the maximum use of the market potential.

The positional school operates within a short time horizon and does not take into account many elements, e.g., the value system and the company’s culture. Its placing of competitiveness first and foremost is the basis for criticizing this school—critics list other factors that may define success (e.g., viability, profit, company reputation, new product, new technology).

An attempt to synthesize early concepts of competitive advantage in the 1980s was undertaken by M.E. Porter, who based the initial period of his research on the foundations of the economics of industrial organization. M.E. Porter concluded that despite the significant impact of the environment on a company’s operations, it is possible to choose the source of competitive advantage. The result of an enterprise’s operation is the effect of an interaction between the structure of the sector and the source of its competitive advantage (generic strategies). The development of a comprehensive means of analysis of the sector and sources of advantage contributed to the formulation of such conclusions, which summarizes the significant contribution of the author to the concept of competitive advantage. Each sector, according to M.E. Porter, has a structural basis or set of fundamental economic and technical characteristics that contribute to the emergence of competitive forces [10].

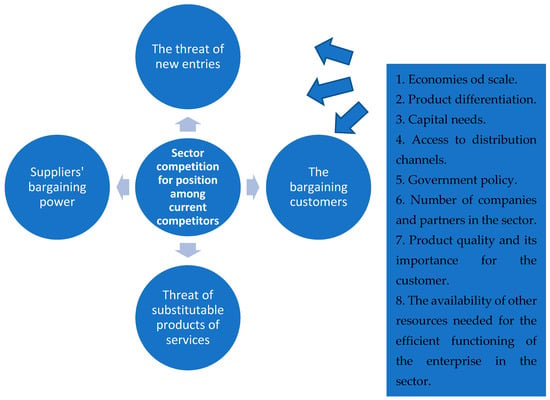

These forces include the threat of new entries, the bargaining power of customers, the threat of substitutable products and services, the bargaining power of suppliers, as well as competition for a position among current competitors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of Porter’s five forces. Source: own work based on [10].

The intensity of these forces is different for each of the sectors, and the strength of each of them is determined by such features as [10]: economies of scale, product differentiation, capital needs, access to distribution channels, government policy, number of companies and partners in the sector, product quality and its importance for the customer, and the availability of other resources needed for the efficient functioning of the enterprise in the sector.

In each of the sectors, the company has several available paths of action aimed at achieving a competitive advantage [11]:

- Cost leadership, the aim of which is to achieve a privileged cost position in relation to rivals and attract a lower price of a product or service;

- Differentiation, thanks to which the unique features of a product or service become the attribute of competitive advantage;

- Focus, enabling one to gain an advantage by limiting the company’s field of operation to selected market segments.

According to M.E. Porter, the main source of competitive advantage is not the efficiency of the enterprise as a whole, but the efficiency of various types of activities that the enterprise undertakes when delivering its product or service to the market [12]. Competitive advantage is a function of the company’s value chain [10], which is a system of interdependent and related activities that determines the impact of performing one of them on the cost and effectiveness of the others. Porter listed and characterized nine activities in the value chain, including [10]:

- Basic activities related to the physical production of the product, its marketing, delivery to buyers, as well as service and after-sales service;

- Supporting activity, which provides the resources and infrastructure to carry out the basic activities.

Value chain analysis enables a company to identify the activities that most contribute to achieving a competitive advantage. Summing up, it should be stated that despite the lack of a clearly formulated definition of competitive advantage, the contribution of M.E. Porter’s theory is quite important. He identified possible sources of competitive advantage, in which he included [10]:

- The environment in which the company operates;

- The selection of the source of advantage related to the analysis of competitors;

- Applying one of the three possible action strategies;

- Deciding on extreme (small or large) scales of operation, because they guarantee the achievement of a high level of profitability.

M.E. Porter tried to answer the question of how to achieve a competitive advantage, without considering the dilemmas of maintaining it. Attempts to supplement the theory with this trend were undertaken, among others, by:

- G.S. Day [13], by creating a systematics of strategies that guarantee the maintenance of competitive advantage;

- P. Ghemawat [14], who recognized that the persistence of an advantage is easier to maintain in markets where there is a wide variety of strategies pursued by individual market participants. However, this returned to the classic sources of competitive advantage, related to the volume of production, access to resources and buyers, and barriers to entry;

- K. Coyone [15] considered that advantage can be permanent only when competitors cannot copy the offer quickly, i.e., if there is a so-called capacity gap. The gap may be functional (it arises when the entity has unique skills in terms of a certain function, e.g., design), decision-making (resulting from decisions and actions taken earlier in the enterprise), regulatory (based on favorable legal regulations) or managerial (arises when the entity undertakes innovative activities faster than the competition);

- G.S. Day and R. Wensley [16] claimed the durability of the advantage is based on the subject’s ability to diagnose the environment and draw the right conclusions. They distinguished between the concepts of sources of advantage, positional advantages and performance outcomes. A company achieves above-average results as a result of their competitive advantage, the source of which is their unique skills and resources.

3. Contemporary Concepts of Competitive Advantage

The next stage in the development of the theory of competitive advantage was creating the Resource Based View (RBV) at the turn of the eighties and nineties last century.

However Under the name of the resource-based theory of the firm, had already come into being thanks to the merits of E. Penrose in 1959 [17,18]. A significant contribution to the development of this trend was made by I. Dierickx and K. Cool, who in 1989 introduced the concept of the accumulation of resources [19]. The basic assumption of this idea is that enterprises use two types of resources in their activities:

- Tangible (available for purchase);

- Intangible (they arise from the accumulation of streams, including decisions about various activities, e.g., research). The enterprise cannot buy these resources, but it can produce them in the long run, e.g., image, prestige, loyalty of buyers.

Due to the fact that intangible resources cannot be purchased, competition over an advantage may lead one to imitation or substitution (gathering other resources). Thus, the achievement and maintenance of a competitive advantage depends on the degree of difficulty with which the intangible assets held may be subject to substitution or imitation by competitors. The lower the possibilities of substitution and imitation by competitors, the more permanent the competitive advantage of the enterprise. The durability of the advantage is also influenced by the low mobility of intangible resources, which was particularly emphasized by the authors of the concept of the accumulation of resources.

The real flourishing of the school of resources and skills, however, was due to C.K. Prahalad and G. Hamel [20,21], who presented the organization as a set of resources and capabilities that serve as the basis for the company’s key competences.

K. Obłój claims that “The fundamental premise of the resource school is the assumption that an organization is a set of assets (resources) and skills”, and further, “An organization builds a competitive advantage by confronting resources and skills into key competences of the company (…). Resources, skills and the key competences built on their basis are all the more valuable as a strategy material, the more the organization is able to defend them against imitation and substitution by rivals (…). The last main premise of the resource school is the assumption that there must be dynamic tension between the resources and the intentions of the company (dynamic fit, stretch)” [7]. According to this concept, a strategy to ensure the efficient use of available resources is the best way to gain a competitive advantage by effectively engaging one’s internal potential. “The knowledge and skills of managers come to the fore in building and configuring the strategic resources of the company. They are treated as factors determining the company’s efficiency to a greater extent than the environment and the structure of the industry. Building a strategy becomes an art again, because its creation are intangible resources and fleeting competences (skills), but an art disciplined by the achievements of evolutionary economics and modern organization theory” [22].

The RBV school assumed that the company’s unique and often intangible resources and skills were essential to its success in any setting [18].

Skills enable a company to use resources better than other competitors. Together, the company’s resources and skills create the company’s core competencies. Competitive advantage is built at the level of the entire company. This school shows which resources and skills are particularly important. This resources can be, for example, the company’s brand, location, design or technology. The company should not only efficiently introduce resources to current ventures, but also use these resources in a mobilizing, strategic way, more efficiently than competitors. The school has been criticized for ignoring companies that have not survived on the market. It is not able to identify what competencies were missing in companies, or when and why these competences met the market requirements. The essence of the considerations made within the resource school is the analysis by J. Barney carried out in 1991 [23]. The initial hypothesis was that enterprises differ in terms of the physical, human and organizational resources at their disposal, and that these resources are not perfectly mobile, which may result in the long-term diversification of enterprises. Important in Barney’s concept was the precise definition of competitive advantage, understood as “the state of a company implementing a strategy that creates value that neither current nor potential competitors have” [23]. Another important issue under development within the resource school is the balanced—in relation to environment—resource development of the company. Hart’s works prove that resources and skills are in a company’s interests, rooted in its interactions with the environment, as they can also lead to a competitive advantage. They connect these issues with the importance of corporate social responsibility, believing that it is also relevant today as a source of competitive advantage [24].

On the other hand, the leverage strategy school, whose representatives include J. Hagel III and J. Brown, focused on development opportunities and achieving a competitive advantage via the use of external resources located outside the company, and not on the potential inherent in the company. According to this concept, a company, in order to gain a strategic advantage, should use all available resources for its development to the maximum extent, and these exist outside of a single enterprise. J. Hagel III and J. Brown distinguished the so-called three waves, leading to the rapid building of a company’s potential thanks to the use of external resources located outside the company [18]:

- The “wave of dynamic specialization” consists of “moving from constant attempts to generate savings from operations to looking for ways to narrow down specialization and entrust some operations to other companies specialized in outsourcing and offshoring processes”. During this wave, the company makes choices focusing on world-class potential areas and abandoning all other activities, and then the developed so-called “Dynamic specialization” ensures the development of the company;

- The “connectivity wave through the ability to connect and coordinate” focuses all the attention of the company on the coordination of activities and processes between multiple cooperating companies in order to use joint potential more effectively in terms of opportunities created by the market. To this end, companies master loose association techniques to create more flexible process networks. During this wave, the company learns and develops ways to access and mobilize the resources of other equally specialized companies to create even more value for customers;

- The “assisted capacity building wave” is that wherein companies shift from coordinating existing resources to more advanced techniques that will amplify capacity-building opportunities in large enterprise networks. The companies that make up the network conclude that the most effective way to accelerate capacity building is to work closely with other specialized companies, mobilizing each other to achieve better results quickly.

According to this concept, companies are able to achieve a strategic advantage only if they focus primarily on internal development, while exploiting the complementary external potential of other economic entities.

Subsequent concepts of competitive advantage that emerged in the 1990s were an attempt to extend the earlier theories. The most important thinkers include the following:

- R. Hall, who, in an attempt to expand the resource theory, classified and identified the impact of intangible resources on competitive advantage [25];

- Ch. Olivier (1997), who defined the determinants and the course of the resource selection process as factors influencing the achievement of a sustainable competitive advantage. At the same time, he recognized that the achievement of such an advantage has an institutional context (it includes principles, norms and beliefs about economic activity) [26];

- U. Jüttner, H.P. Wehrli (1994), S. D. Hunt and R. Morgan (1995), who raised the issue of the relationship of marketing to the resource concept of competitive advantage. At the same time, marketers were assigned the role of a transformer, taking an active role in creating resources [16];

- N. P. Hoffman (2000), according to whom the determinants of building and maintaining a competitive advantage may be, inter alia: the learning process of the organization, innovation, cooperation, relationship marketing, brand and value for the buyer [27].

The concept of competitive advantage has been, is, and will probably remain the subject of researchers’ interest for many years to come. The achievements so far in this field are not satisfactory. While much has been established in terms of the sources of competitive advantage and its durability, the achievements of fundamental importance for researchers are modest—there is no precise definition of competitive advantage. In the 21st century, researchers of the subject try to fill this gap by defining it in relation to the enterprise, sector and economy. An example is the interpretation of W. Wrzosek, according to which the competitive advantage of an enterprise is associated with a more advantageous location on the market compared to the location of competitors. The aforementioned more favorable location transforms into a competitive advantage when it increases the effects of the operation without incurring additional expenditures, or with lower expenditures in relation to the expenditures of competitors, and reduces the size of expenditures via the effects of the operation without fear of reducing them, which cannot be avoided by competitors [28].

The striving of the enterprise and its competitors to achieve a competitive advantage is one of the forces that will contribute to the development of competition, and will also motivate enterprises into even more intense activities in their competitive processes.

4. Pro-Ecological Activities of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Terms of Sustainable Energy Management

The mutual relations between the economy and the natural environment have been studied for many years. In the 1987 Brundtland Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, attention was drawn to a balanced approach to the perception of these interdependencies [29]. This definition was referred to by the authors of the Declaration on Environment and Development from Rio de Janeiro in 1992, where 1 of the 27 principles stated explicitly that the right to development must be enforced so as to fairly take into account the developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations [30]. In turn, in 1997, Nick Hanley, Jason Shogren and Ben White, based on a simplified model of the economy, concluded that these relationships significantly affect quality of life [31].

In a simplified model of the economy, in which there are two sectors (production and consumption), there is a mutual exchange of goods, services and factors of production. In the natural environment, there is a circular motion between three factors: energy and materials, waste sink and amenities. Additionally, these elements contribute to the global life-support services. The manufacturing sector obtains energy resources (e.g., oil) and material resources (e.g., iron) from the environment. These are turned into end products, some of which are useful (e.g., goods and services delivered to consumers) and others are waste (e.g., sulfur dioxide). There is recycling in both the production and consumption sectors.

Therefore, the natural environment plays a double role: a supplier of raw materials and resources, and a recipient of waste resulting from production or consumption. In some cases, these wastes can be biologically or chemically treated in the environment. However, the ability of the environment to assimilate waste is limited by many factors, including by the volume of waste. Hence the importance of corporate social responsibility, realized through pro-ecological activities. The added value of such an attitude is building a positive image and increasing the competitiveness of enterprises [32]. Ecological responsibility often becomes a factor influencing the shaping of the competitive advantages of small and medium-sized enterprises, on global, regional and local scales. The motives that mobilize enterprises to pro-ecological attitudes and sustainable energy management include:

- Increasing social pressure to improve the quality of the environment;

- The growing ecological requirements of consumers, who are becoming more and more sensitive to environmental issues and demand a friendly use of the product;

- The loss of value of technologies and products that do not meet ecological standards, and those that take these standards into account are gaining in importance. The more they protect the environment, the greater their chance in a competitive market;

- Taking into account the requirements of the international market, including the EU market, where it is not possible to sell goods that do not meet the standards in accordance with the needs of environmental protection. This market consistently strives to eliminate environmentally harmful goods;

- Stricter environmental protection regulations and increasing costs of inaction to protect resources and improve the conditions of their exploitation;

- changing the positions of companies on the market that apply pro-ecological management, e.g., operating in accordance with the ISO 14001 series or EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme);

- The field of activities important for achieving profit and a favorable position in the environment is expanding, such as by creating and maintaining the best possible public relations [33,34,35].

The literature on the subject presents numerous tools, concepts and strategies for the pro-ecological activities and sustainable energy management of enterprises, which include [36]:

- formal separation of environmental management as part of enterprise management;

- application of environmental principles within the concept of sustainable development;

- application of the concept of ecological corporate social responsibility (ECSR);

- implementation of standard environmental strategies (dilution or filtering) and preventive environmental strategies (recirculation or prevention);

- implementation of environmental management systems (e.g., according to ISO 14001 or EMAS);

- implementation of the Cleaner Production Program;

- implementation of technological and non-technological eco-innovations;

- use of environmentally friendly additive technologies (pipe end);

- use of environmentally friendly integrated technologies;

- introducing ecological labels for raw materials, materials, products, packaging (e.g., FSC, PEFC, Blue Angel, Ecolabel);

- application of the Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) directive and BAT guidelines (best available techniques);

- designing and offering environmentally friendly products (eco-products);

- designing environmentally friendly solutions (ecodesign);

- striving to minimize waste in production processes;

- reuse of waste in manufacturing processes (recycling);

- creating “green” alliances with other enterprises;

- the use of ecological tools and techniques to improve eco-efficiency, e.g., checklist (MET), strategic scorecard;

- BSC, environmental product life cycle, LCA, or environmental indicators.

The pro-ecological activities undertaken by small and medium-sized enterprises are an expression of innovation that shapes a permanent competitive advantage. They are also consistent with sustainable energy management. According to LG Action, “sustainable energy is not only a problem of durability, but also the approval of energy sources that cause little damage to the environment and human health” [37]. A sustainable energy system “should be based on a combination of renewable energy technologies, renewable fuel transport, renewable heat, demand reduction, efficiency use as well as cogeneration of energy production” [38]. It is also important that it is compatible with other elements of sustainable development [39]. This can be important for the labor market [40]. All this may be favored by the adopted legal framework for the energy transformation in a country [41,42], as well as its politics [43,44]. The renewal of individual elements of a sustainable energy system is widely considered in the literature on this subject [42,45], which proves the importance of the subject matter.

5. Material and Methods

In 2021, the initial empirical research was undertaken on the pro-ecological activities of small and medium-sized enterprises in Poland in terms of shaping their competitive advantage. The study covered the SME sector (2,211,604 enterprises). The choice of the research subject resulted from the domination of small and medium-sized enterprises in the economy, measured by their share in generating GDP, added value and employment.

The decision to choose this research technique resulted from the following premises [46]:

- Need to test a large sample. The large number of cases in this study was extremely important due to the fact that many variables were analyzed;

- A carefully selected random sample combined with a standardized scenario makes it impossible to formulate sophisticated descriptive statements;

- Standardized questionnaires have an important advantage in terms of measurement in general. Most of the concepts are ambiguous. While you should be able to define the concepts in the way that best suits your research goals, it may not be easy to apply the same definitions in all studies. Meanwhile, the use of a questionnaire assumes the fulfilment of this requirement, because all respondents receive exactly the same questions and the same meanings are assumed for all respondents giving a specific answer;

- The possibility of conducting research in a relatively short time, which is important due to the risk of rapid obsolescence;

- The possibility of performing an audit with a relatively small financial commitment.

Surveys conducted on the basis of a questionnaire, apart from their advantages, also have disadvantages. The most important of these are that they can lead to artifacts (the research subject may not be measurable by a questionnaire, or the research files of the subject may have an impact on the answers it gives) and they are inflexible. While being aware of the shortcomings related to the design of the study, significant steps were taken:

- The structure of the questionnaire was prepared on the basis of a “brainstorming”, to which representatives of the world of science (persons with at least a doctoral degree) and persons holding managerial positions in SMEs were invited to participate;

- Despite the careful design of the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted in order to exclude the possibility of mistakes in the form of, for example, ambiguous questions. These studies showed the need to clarify (reformulate) a few questions, which was carried out.

The respondents were presented with a form consisting of 27 closed questions, of which 7 were a record. The survey was anonymous, given the specific nature of the analyzed sector. Most of them are micro-enterprises with no legal obligation to publish financial data, but there are questions on this area of activity. There was concern about the reluctance to answer questions in this area.

In the form, next to the certificate, three other parts are separated:

- Assessment of entrepreneurs’ awareness of environmental protection;

- Assessment of pro-ecological activities undertaken by entrepreneurs;

- Assessment of the impact of pro-ecological activities on the competitiveness of enterprises.

In part, the respondents were asked to assess the significance of individual features and to compare them to competing companies. The solution we used, resulting from, among other things, the various interpretations of the concept of eco-innovation and the lack of real secondary data, is commonly used in the study of enterprises. An example of this is the extensive analyses conducted by M. Gorynia [47] regarding the international competitiveness and internationalization of the company. Competitiveness, assessed by comparing the tested object to the competition, was also assessed by entrepreneurs in a study conducted by B. Jankowska [48] in relation to the international competitiveness of the industry, based on the example of the Polish construction industry. The adopted methodology, giving satisfactory results in the cited studies, was also used in this article.

The survey questionnaire was posted on social media. A total of 452 entities completed the survey, which gave an overall questionnaire return rate at the level of 0.02%. It is worth adding that at the significance level of 0.1 and with an acceptable estimation error of 8%, the necessary sample size was 423 enterprises. Thus, the number of forms obtained exceeded the required minimum sample size, and was sufficient to generalize the obtained results to all small and medium-sized enterprises in Poland.

The respondents were dominated by natural persons running a business (54%) and civil law partnerships (25%). Limited liability companies constituted 16% of the surveyed enterprises, and other legal forms only 5%.

In total, 60% of the respondents employed no more than 9 employees, 22% of entities employed from 10 to 49 people, while the share of enterprises with 50 to 249 employees was only 18%. The size structure of enterprises was verified in the question regarding the value of revenues (net turnover from the sale of goods, services and financial operations) as of 31 December 2020. The vast majority of the surveyed companies (77%) did not exceed revenues of EUR 2 million; 13% of entities generated a turnover in the range of EUR 2 to 10 million, while only 10% of enterprises achieved revenues in excess of EUR 10 million, but no more than EUR 50 million. The vast majority of the surveyed companies (72%) gave a balance sheet total of up to EUR 2 million, and 18% of entities indicated a value of assets between EUR 2 and 10 million, while a small percentage of enterprises (10%) had assets between EUR 10 and 43 million.

The surveyed enterprises are mainly service companies (51%), followed by trade (24%), while a smaller group of entities operate in the fields of production (13%) and construction (12%).

The surveyed enterprises are mostly (62%) entities with a stable position on the market, operating for more than 10 years; almost every fourth enterprise (22%) has been in business for more than 5 years and less than 10 years, while the least numerous (16%) have been operating for no more than 5 years.

6. Results

The first part of the original empirical research concerned the assessment of the degree of awareness of entrepreneurs in the field of environmental protection in terms of sustainable energy management. The vast majority of entrepreneurs (81%) are aware that their economic activity has an impact on the natural environment. A smaller percentage of respondents (12%) were unable to assess this impact, while few entrepreneurs (7%) stated a belief that their business has no impact on the environment. Almost half of the surveyed companies (47%) were convinced that their conducted business activity does not pose a threat to the natural environment, while 42% of entrepreneurs saw such threats, and a small percentage (11%) of the respondents were unable to comment on this topic.

Most of the surveyed entrepreneurs positively assessed their knowledge about the necessity to adapt their enterprise to legal regulations in the field of environmental protection; as many as 54% of the respondents stated that they know the regulations to a good level, and 12% to a very good level. However, every third entrepreneur (34%) admitted that they have little or very little knowledge of environmental protection law. The biggest barriers preventing entrepreneurs from knowing and applying legal provisions in the light of the conducted research include:

- frequent changes of legal norms and their updating;

- dispersed access to regulations in many normative acts;

- the illegibility and heterogeneity of regulations.

The second part of the research was aimed at assessing pro-ecological activities, understood as investments aimed at reducing the negative impact of economic activity on the natural environment (sustainable development), undertaken by entrepreneurs in the last 5 years. Most of the surveyed entities (57%) undertook pro-ecological activities on their own (265 responses) and in cooperation with other entities (123 responses). It is disturbing that entrepreneurs rarely cooperate with local government units (only 45 responses), and very rarely cooperate in this respect with research units or universities (15 responses). This is due to the structural and systemic barriers that hinder cooperation between the business sector and public institutions, the most common of which are:

- the lack of developed strategies and the poor reallocation of EU funds;

- the imperfection and excess of legal acts regulating cooperation between business and public institutions;

- the low level of competence of public administration and university staff;

- the reluctance of employees of public institutions to cooperate with entrepreneurs.

Nevertheless, enterprises—independently or in cooperation with other entities—undertake many pro-ecological activities, including those aimed at sustainable energy management (Table 1). The most common pro-ecological investments that have been undertaken in the last 5 years in Poland, in every fifth enterprise, include:

Table 1.

Environmentally friendly investments financed in 2015–2020 by Polish enterprises.

- education of employees, customers and interested parties;

- improvement of energy efficiency of buildings—thermal modernization of buildings, replacement of windows and doors;

- limiting the use of materials and raw materials in production—circular economy;

- introduction of innovative waste management systems;

- use of renewable energy sources—photovoltaic installations;

- replacement of heat sources with more energy-efficient ones.

The vast majority of enterprises (73%) allocated small funds to pro-ecological investments, not exceeding EUR 10,965, while investment outlays above EUR 10,965, but below EUR 32,895, were incurred by 16% of the surveyed companies, and the largest investments (above EUR 32,895) were undertaken by only 11% of entities. It is worth noting that pro-ecological investments were financed by enterprises’ own funds and bank loans. Only 21% of entities took advantage of national funds (instruments financed by the Provincial Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management, and the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management), as well as European Union funds under regional programs (Regional Operational Programs for Voivodeships) and the central program (Operational Program Infrastructure and Environment).

The vast majority, as many as 79% of the surveyed entities, did not take advantage of the possibility of co-financing pro-ecological investments via dedicated national funds or European Union funds, because of the encountered limitations and difficulties. In light of the conducted research, the biggest barriers preventing entrepreneurs from using external sources of funding include:

- poor access to funds, as it is not known where to look for information on co-financing, and information about competitions is scattered on many websites;

- difficulties in collecting own contributions necessary to finance the investment;

- unclear competition regulations, making it difficult to understand the awarding criteria and complicated fields of application generators;

- limited access to loans enabling the pre-financing of investments.

Interesting results were obtained from entrepreneurs regarding their interest in pro-ecological investments that would be undertaken if the audited entity received external funds for their financing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Expectations of entrepreneurs with regard to financing pro-ecological investments.

Expectations for financing pro-ecological investments, stated in every fifth enterprise, refer to the following activities:

- application of renewable energy sources—photovoltaic installations;

- introducing innovative waste management systems;

- improving the energy efficiency of buildings—thermal modernization of buildings, replacement of windows and doors;

- introduction of an energy-saving machine park;

- introduction to the fleet of vehicles with electric or hybrid drive;

- use of renewable energy sources;

- replacement of heat sources with more energy-efficient ones;

- application of renewable energy sources—solar collectors.

The last part of the study was aimed at assessing the impact of pro-ecological activities on the company’s competitiveness, understood as the ability to present a more advantageous offer than other companies operating in the same industry. Most of the surveyed entrepreneurs (61%) were aware that their pro-ecological activities affect the company’s competitiveness, and only every fifth surveyed company (21%) stated a belief that pro-ecological activities do not affect its competitiveness. Almost half (43%) of entrepreneurs believed that the pro-ecological activities carried out in the company do not result from linking them with the competitiveness of the entity, while 39% of the surveyed companies believed that the pro-ecological activities undertaken by them result from the awareness of linking them with the competitiveness of enterprises, and the remaining 18% of entities were not able to assess the above dependence. More than half of the respondents (55%) shared the opinion that the company should be perceived as an environmentally friendly entity, while only 21% of the respondents had a different opinion, and 24% of companies were unable to comment on this issue.

In subsequent questions, the management staff of the surveyed enterprises assessed the significance of the elements shaping their competitive advantage. For this purpose, entrepreneurs were asked to rank the elements of competitive advantage from the most important to the least important, and they had the option of adding their own element. During the conducted research, none of the entrepreneurs added their own element of competitive advantage. Table 3 presents the ranking based on the significance of individual elements of competitive advantage in the surveyed enterprises.

Table 3.

Assessment of the significance of individual elements shaping the competitive advantage.

Among the listed elements, the entrepreneurs considered the most important components of the entity’s competitive advantage (significance from 1 to 6):

- the amount of equity;

- the possibility of co-financing projects with foreign capital;

- corporate image;

- quality of the management staff;

- cooperation between management and employees;

- quality of employees.

Entrepreneurs agreed that the key elements of a company’s competitive advantage result primarily from the amount of current and potential capital, the company’s image, the quality of management staff and cooperation with employees, and the quality of employees. On the other hand, in the opinion of entrepreneurs, taking pro-ecological actions was ranked in the 16th position as an element of competitive advantage.

Another question addressed to the management staff concerned the assessment of their competitive position based on the elements shaping their competitive advantage. For this purpose, entrepreneurs were asked to rank the position of their enterprise in relation to their competitors on a scale from −2 to +2 for the elements indicated in the questionnaire (Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of the competitive positions of enterprises according to the elements shaping their competitive advantage.

In the case of all the examined elements of competition indicated in Table 4, the surveyed entrepreneurs assessed themselves at a level comparable with other competing enterprises (dominant). Entrepreneurs assessed the following factors shaping their competitive advantage in their own country most highly:

- quality of employees;

- cooperation between employees;

- market information.

On the other hand, the factors shaping competitive advantage assessed the lowest are:

- possibility of financing with external capital;

- undertaking pro-ecological activities;

- marketing activities;

- the size of the enterprise.

Then, the management staff of the surveyed companies were asked to assess the significance of individual elements of pro-ecological activities as an element of competitive advantage. For this purpose, entrepreneurs ranked the given elements of competitive advantage from the most important to the least important, with the respondents having the option of adding their own element. During the research, none of the entrepreneurs added their own pro-ecological activity as an element of competitive advantage. Table 5 presents the ranking by significance of individual pro-ecological activities of the surveyed enterprises.

Table 5.

Assessment of the significance of pro-ecological activities as elements shaping a competitive advantage.

Among the pro-ecological activities, the following were considered to be the most important components of the companies’ competitive advantages:

- use of renewable energy sources—photovoltaic installations;

- improvement of the energy efficiency of buildings—thermal modernization of buildings, replacement of windows and doors;

- energy-saving machinery park;

- introduction to the fleet of vehicles with electric or hybrid engines;

- use of other renewable energy sources.

The indicated factors shaping competitive advantage coincided with the expectations of entrepreneurs in terms of the need to finance pro-ecological investments aimed at economic efficiency.

Another question addressed to the management concerned the assessment of competitive advantage based on selected elements of pro-ecological activities. For this purpose, entrepreneurs were asked to rank the position of their enterprise in relation to competitors on an appropriate scale from −2 to +2, for each of the elements shaping a competitive advantage, in relation to pro-ecological activities, as indicated in the questionnaire (Table 6).

Table 6.

Assessment of the competitive advantage of enterprises as regards pro-ecological activities.

For all the examined elements of pro-ecological activity indicated in Table 4, the surveyed entrepreneurs assessed themselves at a level comparable to other competing enterprises (dominant). Entrepreneurs assessed the following pro-ecological activities the best:

- education of employees, customers and interested parties;

- improvement of energy efficiency of buildings—thermal modernization of buildings, replacement of windows and doors;

- limiting the use of materials and raw materials in production—circular economy.

On the other hand, the pro-ecological activities assessed as the worst were:

- application of renewable energy sources—photovoltaic installations;

- introducing innovative waste management systems;

- introduction of an energy-saving machine park.

The last issue examined was the identification of the motivation for pro-ecological activities undertaken by Polish entrepreneurs. The respondents indicated that the following factors motivate them to make investment decisions:

- reduction in operating costs in the long run;

- obtaining financial benefits.

The following factors were important aspects:

- being perceived on the market as an ecological entity by contractors, customers and employees;

- the possibility of using funding;

- competitive struggle.

The above statements confirm that the main motivators for pro-ecological investments in Polish enterprises are economic.

The last issue examined was the identification of motivations of pro-ecological activities undertaken by Polish entrepreneurs. The respondents indicated that the following factors motivate them to make investment decisions:

- reduction in operating costs in the long run;

- obtaining financial benefits.

The following factors were important:

- being perceived on the market as an ecological entity by contractors, customers and employees;

- the possibility of using funding;

- competitive struggle.

The above statements confirm that the main motivators for pro-ecological investments in Polish enterprises are economic.

7. International Review

In order to compare pro-ecological investments in Poland against the background of European Union countries, the concept of eco-innovation can be used, which is understood as a new or significantly improved product, process, or organizational or marketing method bringing benefits to the environment [49]. Focusing on eco-innovation, in general, researchers define it in two ways: by its effect on the environment, and/or by the intention of the innovator [50]. Eco-innovation can be defined by its effect as “the production, assimilation or exploitation of a product, production process, service or management or business method that is novel to the organisation (developing or adopting it) and which results, throughout its life cycle, in a reduction of environmental risk, pollution and other negative impacts of resources use (including energy use) compared to relevant alternatives” [51]. Eco-innovation by motivation can be defined as “innovation processes toward sustainable development” [52].

Eco-innovations contribute to improvements in resource efficiency in the economy and reductions in the negative impact of human activity on the environment. In addition to the ecological dimension, the economic aspect is also important, because the introduction of eco-innovation contributes to a reduction in operating costs, the use of new development opportunities, and the creation of a positive image of the entity; as a result, it contributes to an increase in the company’s competitiveness.

Based on 16 indicators grouped into five thematic sets (inputs, activities, results, environmental effects, socio-economic effects), we used the so-called Eco-Innovation Scoreboard to comprehensively compare the eco-innovation results achieved among European Union countries over the last 5 years (Table 7). This indicator comprehensively compares the eco-innovation results achieved by individual Member States in relation to the EU average (EU-28 = 100).

Table 7.

Eco-innovation index for European Union countries in 2015–2019.

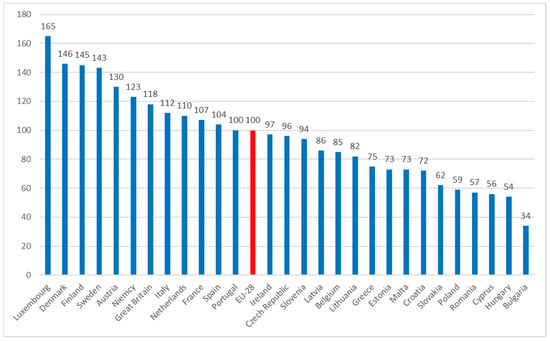

According to the ranking presented in Table 7, Poland is one of the countries with the lowest eco-innovation scores among the European Union countries. When making an assessment for the last year, one can form groups from the highest to the lowest eco-innovation rates (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

When making an assessment for the last year, one can form groups from the highest to the lowest eco-innovation rates [49].

Based on the above data, it can be concluded that Poland was placed 24th (with a score of 59) in the ranking of 28 EU countries. Poland, along with Bulgaria, Hungary, Cyprus, Romania, Slovakia, Croatia, Malta, Estonia, Greece and Lithuania, was classified as one of the countries with a large backlog in eco-innovation, achieving results below 85% of the EU average. The following countries qualified above the EU average in terms of eco-innovation: Luxembourg, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Austria, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, France, Spain and Portugal. Poland’s unfavorable position in the ranking may result from many factors, including financial barriers on the part of entrepreneurs and consumers, their insufficient awareness of the benefits of implementing innovative ecological technologies, and insufficient government spending on R&D, including in the field of the environment.

The quoted international data confirm the extensiveness of the survey research conducted. For many countries and businesses, environmental awareness is relatively low. When it occurs, it is not translated into real activities in the field of sustainable energy management in the absence of economic efficiency.

Research related to the eco-innovation of SMEs is carried out by many institutions and organizations. The research results prepared by the European Commission are interesting. They cover all EU countries. These studies confirm the results of our own research. They indicate that the main motive for introducing eco-innovation is the savings premise. SMEs can adopt the following strategies in this regard:

- Reactive (introduction of legal requirements)—driven by compliance. Cost savings are generally a driver, and may also be a side-effect of compliance with legislation;

- Follower—fear of being left behind and reputational loss. Offers financial aid for investment. Has the intention of being eco-innovative via cost-savings. Seeks to imitate strategic or disruptor positions—can do so successfully by squeezing costs and offering cheaper products than competitors. Cost savings may arise via the drive to increase efficiency and retain market share;

- Strategic—proactive enterprise development strategy. Networking and financial support for research and innovation. Recognition of superior performance through labels and prizes. Not particularly motivated by cost-saving behavior during the strategic phase—aiming to lead the existing market, and realize a price premium for leadership. Generally aiming to achieve a higher price from a smaller market. An SME may only be able to maintain a “strategic” position for a few years, before “followers” catch up, at which point cost savings may again become an important factor to retain market share for a product;

- Disruptor—longer-term policies and/or equity funds. Motivation is to change complete value chains—cost savings may play one part of the bigger picture.

- Intrinsically motivated disruptor—mission- or value-based innovation strategy. Funds, incentives or interventions that bridge business and social entrepreneurship. Driven by improving public good, and environmental and working conditions, not by maximizing cost savings [51].

The results of the research carried out in Great Britain are also interesting. They show that half of the enterprises (53%) have undertaken eco-innovation activities. The vast majority of SMEs (94%) have undertaken at least one physical activity. More than half (56%) of smaller companies did not take any action to improve their knowledge and skills. Cost was the most important barrier to action (35%) and feasibility (32%). “Another perspective on this approach is to consider this in terms of how intrinsic (i.e., personal), extrinsic (i.e., firm), and external (i.e., market or regulatory) factors influence different aspects of SMEs’ environmental orientation. This suggests that personal motivations may be important in driving relatively low-cost organizational changes, but it is external drivers—related to market or regulatory changes—which prove more important in driving more costly technological interventions” [53].

The cited research results confirm the hypothesis adopted in the article. Despite the research being carried out in different countries, the conclusions are similar.

8. Conclusions

The subject of sustainable energy management is being more and more widely taken up by theoreticians and practitioners of economics and management. Improved products, processes and organizational methods bring significant economic and social benefits to the environment. They reduce the negative impact of human activity on the environment. They also contribute to reducing operating costs, creating a positive image of the entity, and building a competitive advantage for enterprises.

Extensive primary empirical research has confirmed that entrepreneurs are aware of the impacts of their activities on the natural environment. Most of them are familiar with the law in the field of environmental protection. At the same time, they judge it as illegible and scattered in many normative acts, which creates problems in its interpretation and application, even for experts. Many enterprises undertake pro-ecological activities on their own, and others do so in cooperation with other entities. Unfortunately, the cooperation of entrepreneurs is very rarely conducted with local government units, research units and universities.

Most often, pro-ecological investments with a low budget are implemented, such as the education of employees or customers. The second group consists of activities ensuring a high rate of return on investment. These included, in particular, measures aimed at improving the energy efficiency of buildings, limiting the use of materials and raw materials in production, the use of photovoltaic installations as alternative energy sources, and the replacement of heat sources with more energy-efficient ones.

The vast majority of enterprises allocated small funds to pro-ecological investments, which were financed from their own funds and bank loans. Only every fifth entity took advantage of national funds or European Union funds, resulting from the numerous barriers and difficulties encountered when applying for external funds, which force enterprises to use the services of specialists.

The most frequently mentioned pro-ecological investments, implemented by every fifth Polish enterprise if it had received funds to finance them, include activities allowing them to minimize the costs incurred. These include, in particular, investments allowing the use of renewable energy sources (photovoltaic installations, solar collectors) and investments improving the energy efficiency of buildings, replacing heat sources with more efficient ones, and introducing an energy-saving machine park and electric or hybrid vehicles.

Most of the surveyed entrepreneurs were aware that their pro-ecological activities affect the company’s competitiveness, and shared the opinion that the company should be perceived as an ecological entity. Less than half of the surveyed companies held the opinion that the pro-ecological activities they undertook resulted from an awareness of linking them with the competitiveness of enterprises, which confirms the tendency of entrepreneurs to undertake cost-effective pro-ecological activities.

The most important components shaping the companies’ competitive advantages were, among the several elements indicated in the questionnaire, the amount of equity, the possibility of financing projects with foreign capital, the company’s image, the quality of the management staff and cooperation between the management and employees. On the other hand, taking pro-ecological actions, in the opinion of entrepreneurs, is not a significant factor of competitive advantage.

In the case of the examined elements of competition, the surveyed entrepreneurs assessed themselves at a level comparable to that of other competing enterprises. The indicated elements coincided with the expectations of enterprises in terms of potential pro-ecological activities, which would be undertaken with unlimited financial resources.

Secondary empirical research, based on international data, confirmed the primary research. In the cases of many countries and enterprises, environmental awareness is relatively low. Where it occurs, it is not translated into real action in the event of a lack of economic efficiency.

Under the conditions of the enormous competition on the market, the pro-ecological orientation of a company currently means not only acting in accordance with the regulations. The conscious building of the business model of a modern enterprise must assume that a “green” attitude is a source of competitive advantage, a basis for development, a platform for the implementation of the company’s strategy, a chance to improve the social acceptance of the company’s development path, a company’s distinguishing feature on the market (including by creating a positive image and reputation), the basis for building the company’s value, the basis for social dialogue, the balance point between shareholders and other stakeholders, and a comparative criterion in the process of assessing the company’s competitiveness [54]. It is also the basis of sustainable energy management, which can be implemented by prepared leaders [55] using the attributes of innovation [56].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.-P. and M.M.; methodology, M.K.-P. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.K.-P. and M.M.; investigation, M.K.-P. and M.M.; resources, M.K.-P. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.-P. and M.M.; supervision, funding acquisition, M.K.-P. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results can be found in Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the companies’ representatives for participating in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Data supporting reported results: “Results of the research study of pro-ecological activities undertaken by enterprises”.

References

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report. 2021. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2021.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Wysocki, W. Innovative Green Initiatives in the Manufacturing SME Sector in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Data Eco-Innovation Scoreboard and Eco-Innovation Index|Eco-Innovation Action Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/ecoap/indicators/index_en (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Alderson, W.A. Marketing View of Competition. J. Mark. 1937, 1, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.K. Survival Strategies in a Hostile Environment. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1980, 9–10. Available online: https://hbr.org/1980/09/survival-strategies-in-a-hostile-environment (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Henderson, B.D. The Anatomy of Competition. J. Mark. 1983, 17, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Obłój, K. Strategia Organizacji; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M.C. The Past and Future of Competitive Adventage. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2001, 42, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Stonehouses, G.; Hamill, J.; Campbell, D.; Purdie, T. Globalizacja, Strategia i Zarządzanie; Felberg SJA: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Porter o Konkurencji; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Strategia Konkurencji. Metody Analizy Sektorów i Konkurentów; Wydawnictwo MT Biznes Spzo.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grudzewski, W.M.; Hejduk, I.K. Przedsiębiorstwo Wirtualne; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Day, G. Continuous learning about markets. Calif Manag. Rev. 1984, 36, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghemawat, P. Competition and business strategy in historical perspective. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2002, 76, 37–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K. Sustainable Competitive Advantage: What it is and what it isn’t. Bus. Horiz. 1986, 29, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyżanowska, M. Nowoczesne koncepcje przewagi konkurencyjnej. Mark. I Rynek 2007, 8, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hagel, J., III; Brown, J.S. Organizacja jutra. In Zarządzanie Talentem, Współpracą i Specjalizacją; Wydawnictwo Helion: Gliwice, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dierickx, I.; Cool, K. Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 2–15. Available online: https://hbr.org/1990/05/the-core-competence-of-the-corporation (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Hamel, G.; Prahalad, C.K. Przewaga konkurencyjna jutra. In Strategie Przejmowania Kontroli Nad Branżą i Tworzenia Rynków Przyszłości; Business Press: Warszawa, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J. Research In Strategy. Economics and Michael Porter. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/014920639101700108 (accessed on 4 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, R.A. Framework Linking Intangible and Capabilities to Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 607–618. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2486860 (accessed on 27 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Combining Institutional and Resource-Based Views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3088134 (accessed on 10 August 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffman, N.P. An Examination of the sustainable competitive advantage. Concept: Past, present, and future. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2000, 4, 1–16. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.200.7948&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Wrzosek, W. Przewaga konkurencyjna. Mark. I Rynek 1999, 6, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Raport Światowej Komisji do Spraw Środowiska i Rozwoju. Nasza Wspólna Przyszłość; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dokumenty Końcowe Konferencji Narodów Zjednoczonych. Środowisko i Rozwój; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, N.; Shogren, J.F.; White, B. Environmental Economics in Theory and Practice; MacMillan Press: Hampshire, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penc, J. Zarządzanie w Warunkach Globalizacji; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Penc, J. Gospodarka w dobie przełomu. Probl. Ekol. 2007, 11, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Żak, K. Proekologiczne modele biznesu przedsiębiorstwa. Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Katowicach 2017, 322, 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, J. Strategic approach to pro-ecological activities of companies. Eur. J. Serv. Manag. 2016, 18, 63–66. Available online: https://wnus.edu.pl/ejsm/en/issue/122/article/1251/ (accessed on 10 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Prandecki, K. Teoretyczne podstawy zrównoważonej energetyki. Studia Ekon. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Katowicach 2014, 166, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchel, C. The Political Economy of Sustainable Energy; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Belke, A.; Dreger, C.; Dobnik, F. Energy consumption and economic growth–new insights into the cointegration relationship. Energy Econ. 2010, 33, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gawrycka, M.; Szymczak, A. A panel analysis of the impact of green transformation and globalization on the labor share in the national income. Energies 2021, 14, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-X.; Liou, H.M.; Chou, K.T. National Energy Transition Framework toward SDG7 with Legal Reforms and Policy Bundles: The Case of Taiwan and Its Comparison with Japan. Energies 2020, 13, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pietrzak, M.B.; Igliński, B.; Kujawski, W.; Iwański, P. Energy transition in Poland—Assessment of the renewable energy sector. Energies 2021, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiał, W.; Zioło, M.; Luty, L.; Musiał, K. Polityka energetyczna krajów Unii Europejskiej w kontekście rozwoju odnawialnych źródeł energii. Energies 2021, 14, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianguo, L. Diversification and localization of energy systems for sustainable development and energy security. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Skrzatek, M.; Kujawski, W.; Cichosz, M.; Buczkowski, R. SWOT analysis of renewable Energy sector in Mazowieckie Voivodeship: Current progres, prospects and policy implications. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. Badania Społeczne w Praktyce; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Gorynia, M.; Jankowska, B. Klastry a Międzynarodowa Konkurencyjność i Internacjonalizacja Przedsiębiorstwa; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, B. Międzynarodowa Konkurencyjność Branży na Przykładzie Polskiej Branży Budowlanej w Latach 1994–2001; Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. Eco-Innovations in SMEs. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/17af0982-52ca-11ea-aece-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of Eco-innovations: Reflections from selected case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Pearson, P. Final Report of the MEI Project Measuring Eco Innovation. UM Merit Maastricht. 2007. Available online: http://www.merit.unu.edu/MEI/deliverables/MEI%20D15%20Final%20report%20about%20measuring%20eco-innovation.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-Innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enterprise Research Centre. The State of Small Business Britain 2021. Enabling the Triple Transition. 2021. Available online: https://www.enterpriseresearch.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/96202-ERC-State-of-Small-Business-2022-WEB.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Chodyński, A.; Jabłoński, A.; Jabłoński, M. ECSR–koncepcja strategiczna oparta o ekologiczną i społeczną odpowiedzialność biznesu. In W Poszukiwaniu Nowych Paradygmatów Zarządzania; Hejduk, I.K., Grudzewski, W.M., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karaszewski, R.; Drewniak, R. The Leading Traits of the Modern Corporate Leader: Comparing Survey Results from 2008 and 2018. Energies 2021, 14, 7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Kędzierska-Szczepaniak, A.; Szczepaniak, K.; Cheba, K.; Gajda, W.; Ioppolo, G. Innovation in sustainable development: An investigation of the EU context using 2030 agenda indicators. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).