Abstract

Ocean energy is a promising source of clean renewable energy, with clear development targets set by the European Commission. However, the ocean energy sector faces non-technological challenges and opportunities that are frequently overlooked in deployment plans. The present study aimed to provide a critical evaluation of the ocean energy sector’s legal, institutional, and political frameworks with an identification and analysis of both barriers and enabling features for the deployment of ocean energy. In the first stage, a literature review on the current political and regulatory frameworks of a set of European countries was carried out, setting the basis for the main challenges and enabling factors faced by the sector. Secondly, a critical analysis of the main non-technological barriers and enablers was performed, which was supported by questionnaires sent to regulators, technology developers, and test-site managers. This questionnaire allowed us to collect and integrate the views, perceptions, and personal experiences of the main stakeholders of the ocean energy sector in the analysis. The most relevant insights were collected to guide future policy instruments, supports, and consenting measures in a more informed and effective manner and to help accelerate the development of the sector.

1. Introduction

In the late 1990s, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected that, without new policy initiatives, fossil fuel would account for more than 90% of total primary energy demand in 2020 [1]. Twenty years later, the IEA’s discourse evolved, now emphasizing a shift to low-carbon renewable energy generation, reducing the dependence on fossil fuels in a worldwide context of continued growth in demand [2].

Renewable energy sources have increased from 5.1% of Europe’s TPES in 1990 to 14.6% in 2017 [3], which is the result of long-term strategic plans and ambitious policy mandates aiming to decarbonize all energy sectors. In 2012, in addition to four other cross-cutting policies of the EU’s Integrated Maritime Policy, the European Union (EU) initiated its Blue Growth Strategy. In this policy initiative, the EU recognized ocean energy as a priority, identifying it as an economy driver, to significantly contribute to the objectives of the European 2020 Strategy, to the reduction of long-term greenhouse gas emissions, as well as to the creation of a blue economy and job opportunities [4]. The new roadmap for ocean renewable energy (ORE) adopted in 2020 reinforces this European commitment for the sector.

At the scale of application of these EU political strategies, the energy transition scenarios defined by the member states contribute to implementing a decentralized and territorialized vision of the energy transition [5,6]. This has the effect of bringing to the forefront social, political, economic, and cultural issues specific to these territories. Even though research and development of ocean renewable energy has mostly focused on overcoming existing technological challenges, non-technical issues and their blocking power have been recognized in the literature [7]. Considering the non-technical issues to the development of ORE, the literature emphasizes the major role that specific regulatory frameworks could play in overcoming them [8,9]. Legal and institutional challenges are also highlighted to reduce risks, time, and costs taken to conduct consenting processes and validate the environmental impact assessment [10,11]. Other studies on non-technical barriers to ORE consider economic barriers to the rise of an effective ORE market [12], as well as active energy citizens to enhance public participation and acceptability to consenting processes [13]. Recent research also emphasizes a systemic view to overcome coupled technical and non-technical challenges applied in a social-ecological system in the presence of ORE [14]. Therefore, this research is relevant for the sector because it provides a refined and updated specification of a political and regulatory framework of a set of EU countries among which the technological development of marine renewable energy (MRE) will be increasingly dynamic. The analysis covers existing non-technological issues from the political planning level (marine spatial planning (MSP), national strategies, etc.) to the operational implementation level (consenting, licensing processes). From a methodological point of view, this study is innovative in that, in addition to a complete review of the state of the art on current non-technological issues, it carried out a targeted survey of perceptions among actors directly involved (industrial and administrative) in the processes described.

The present study concerned the analysis of the existing legal, institutional, and political barriers and enabling factors to the ocean energy sector in Europe. The analysis was complemented by the results of a questionnaire to key stakeholders in the sector. The aim was to guide future policy instruments, supports, and consenting measures in a more informed and effective manner. In Section 2, the study methodology is described. The review of National and EU Legal Frameworks is compiled in Section 3. In Section 4, the positive and negative impacts of the existing national and international frameworks on the ocean energy sector are evaluated, supported by the stakeholders’ responses to the questionnaire. The most important outcomes of the work are compiled in Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

An initial review on the current political and regulatory frameworks was carried out, to consolidate up-to-date information and to set the basis for the identification of the main challenges faced by the sector. This review targeted a selected set of nine countries active in the ocean energy sector: Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (UK). The review focused on the following topics:

- EU policies and legislation

- National policies and marine spatial planning

- Administrative and licensing procedures

Most of the research work on the political and regulatory frameworks relevant to the ocean energy sector was carried out between January 2019 and March 2021. A final review was conducted prior to submission to identify and correct potential changes.

Furthermore, in order to evaluate the positive and negative impacts of such frameworks, a critical analysis on main barriers and enablers was performed. This analysis, structured around the same topics examined in the literature review, was supported by a questionnaire of targeted stakeholder groups including regulators, technology developers, and test site managers. This approach aimed to collect the views and perceptions from the selected target groups, in order to enrich and validate the analysis with their personal experiences.

The perceptions of the stakeholders on the bespoke topics were captured based on their responses to the list of score-based questions. Within each topic, relevant outputs from the questionnaires were incorporated in the in-depth analysis on the perceived situation for each parameter to support the arguments. A certain degree of interpretation was required in the applied methodology to analyse and communicate the open answer responses in a simple narrative form.

2.1. Questionnaire Methodology

A questionnaire entitled “Regulatory and Political Barriers to Ocean Energy Deployment” was developed and distributed among key stakeholders to identify the potential non-technological barriers and enablers to ocean energy, based on their individual experiences. It was distributed between March and September 2020.

This questionnaire aimed at:

- Providing an overview on respondents’ past and present experiences interacting with the regulatory framework concerning their project’s deployment, and

- Exploring respondents’ perceptions on what they consider to be key barriers and enablers to ocean energy deployment in the marine governance structure.

2.1.1. Stakeholder Identification

According to the JRC [15], 30 tidal stream energy companies and 31 wave energy companies are actively engaged in the development devices with a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) higher than 5. The stakeholder engagement process started with the identification, by DTOceanPlus [16] project partners, of wave and tidal technology developers representing a range of EU countries with active projects during the period 2009–2019 (10 years) and spread across TRL5 and above. The questionnaire was electronically sent to 99 stakeholders representing approximately 14 countries. The questionnaire was also made public to increase the response rate.

To capture the insights from technology developers with meaningful operational experience, a minimum technology maturity was defined as TRL6, i.e., technology demonstrated in relevant environment. This stage was selected since it meant that it ensures a degree of experience in scale-model testing and operation in sea conditions. Although the TRL of each technology is not always clearly defined, an effort was put into obtaining the most accurate TRL for each company selected. However, it must be noted that such an approach has some limitations since this information is mostly based in publicly available data, which, in turn are based on the reported stage of testing (e.g., tank test, scale test, full scale, electricity generation, prolonged operation). In an effort to obtain the most updated data, respondents were also asked to provide more information and suggest the TRL of their technology.

2.1.2. Questionnaire Structure Design

With these objectives in mind, the questionnaire was structured in three main sections:

- General respondent information—required information regarding organisation name, role in the organisation, contact and group of stakeholders, latest experiences concerning number of regulators involved, timeline of the consenting process, and number of licenses required. This information aimed at assessing systematic preferences/biases of types of stakeholder characteristics towards certain barriers.

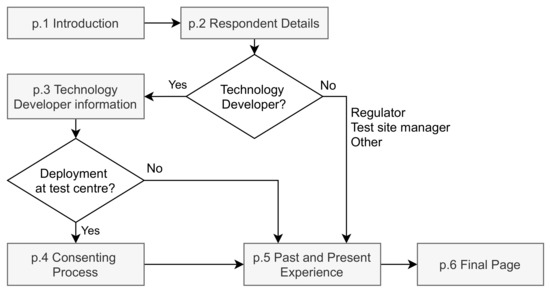

- Detailed respondent information—the questionnaire was designed to show different questions to respondents, depending on the stakeholder group they belong to (Figure 1 shows the different questionnaire routes). Technology developers were asked to answer questions related to their technology such as the name of the company, technology name and description, TRL, country of deployment, and whether it had been deployed in a test centre. Furthermore, technology developers that did not deploy in test centres were asked about how long the consenting process lasted and which permits were required.

Figure 1. Survey map.

Figure 1. Survey map. - Past and present experience—constituted the main section of the questionnaire and evaluated respondents’ perceptions on barriers in the legal and political framework given a set of parameters such as national policies, administrative procedures, and integrated planning.

The first question was to rank the following set of parameters considering the extent to which each one is viewed as either a barrier or enabler to project deployment: EU policies, national policies, stakeholder consultation, entities involved, EIA and monitoring, administrative procedures, and integrated planning. Respondents were given the chance to write more about the parameters they ranked as significant barriers or absolute enablers. Then, three open question answers were posed regarding MSP, the level of communication between technology developers and regulatory entities, and how the current legal framework in their respective countries of deployment applied to ocean energy. Another rank-based question was asked as to which extent the following set of EU policy mechanisms enabled project deployment: renewable energy targets, ORE targets & strategies, technology push, demonstration projects, market incentives, resource allocation and standardization, and information sharing. Finally, respondents were asked two more questions, regarding national policies in place, and were asked to comment on the following sentence: “Lack of long-term political strategy, lack of cooperation between government, industry and research institutions, unrealistic ORE targets, unsuitable funding schemes. These are among the most relevant barriers associated with the current institutional and political framework for ocean energy”.

3. Review of Legal Frameworks and Licensing Procedures

This section comprises information gathered from the following EU Member States on their current legal, political, and regulatory frameworks: Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden. Although the UK is no longer an EU Member State, it was included in this analysis because of its relevance as a global leader in the ocean energy sector. The bulk of EU policies have been transposed into UK law, and they remain aligned for now. The UK Government’s department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is responsible for the over-arching energy policy in the UK, although powers related to planning, fisheries, and the promotion of energy efficiency are devolved to the governments of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland; so, these nations have been addressed separately where relevant.

3.1. EU Policies and Legislation

Ocean energy has been the subject of different policy initiatives in the past years, both at European and national levels. Table 1 shows the most relevant policy fields on the EU level.

Table 1.

EU policy fields for ocean energy. Adapted from [8,9].

The Energy Union, the Blue Growth Strategy, and the SET-Plan are the main policy initiatives currently in place in the European Commission (EC). The EC has proposed an EU Innovation Fund for the period of 2021–2027, which will build on the NER300 program. It aims at enhancing cost-effective emission reductions and low-carbon investments in, among other sectors, innovative renewable energy technologies. Networks such as OES and European Energy Research Alliance (EERA) have also been playing an important role in the advancement of the sector. Additionally, the international environmental regulation of all types of energy generation activities at sea is first and foremost anchored to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [38]. This establishes rules governing all uses of the world’s oceans and seas including their resources. The Revised Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) was approved in December 2018 and includes a mandatory target of 32% of the energy generated through renewable sources by 2030. Following the EC directives, member states were requested to submit their National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), featuring their national Renewable Energy (RE) targets, by December 2019. Now, according to this legal framework, member states are required to develop long-term national strategies that are consistent with their established targets. It is important to stress the ambitious targets several member states have already set through their National Renewable Energy Action Plans (NREAPs).

The European Commission adopted in 2020 a new strategy on offshore renewables containing key provisions on ocean energy, setting deployment objectives for wave and tidal energy: 100 MW by 2025, 3 GW by 2030, and 40 GW by 2050 [39].

Although each member state under analysis has their own planning and development legislation, it is important to note these must comply with EU legislation. While each piece of legislation defines future achievements and goals, their implementation is the responsibility of each member state through their adaptation to national laws. The five major pieces of overarching EU legislation are also shown in Table 1.

3.2. National Policies and Marine Spatial Planning

National governments in several member states are applying a range of policy instruments to promote and accelerate ocean energy deployment in their waters and to enable investment in new technologies. This section covers the operational, legal, and institutional frameworks applicable in each member state. The selection of appropriate policies by national governments depends upon the maturity of the ocean energy sector, their national supply/demand balance, energy system resilience, and willingness to invest in new technologies [9].

Only a few countries in which ocean energy technologies are currently being developed have specific policies to promote ocean energy uptake. Most of them have ocean energy or ocean renewable electricity generation targets, except for Denmark, which has a significant wave energy resource and is a pioneer in wave energy but has not set any target for the sector. Finland, Portugal, and Spain have included ocean energy technology in their NREAPs but have no dedicated market support system.

In France, the “Investment for the Future” program (technology push), managed by the Ministry for the Ecological and Inclusive Transition (MTES) on energy topics, is the major provider of incentives for ocean energy. The latest pluri-annual energy plan (PPE), adopted in April 2020, defines specific objectives for ORE set by the MTES to turn France carbon neutral by 2050. To meet these objectives, France launched in 2017 a Maritime and Coastline Strategy (SNML) to conduct the implementation of its marine spatial planning (MSP). The national strategy is implemented at the sea basins by means of the Sea Basin Strategy Documents (DSF). These documents were completed in 2019 and delineate macro-zones suitable for the deployment of offshore renewable energies (wind and tidal). The plans will be followed by the development of an action plan and a monitoring system by 2021.

In Ireland, the sector is regulated by several legislative acts—the Foreshore Act/Maritime Area and Foreshore (Amendment) Bill, the Electricity Regulation Act 1999, the Planning and Development Regulations 2001, the Grid Code, and the Distribution Code. The spatial planning system is set by the recent Marine Planning and Development Management (MPDM) Bill under the National Marine Planning Framework (NMPF). The Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment (DCCAE) and the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) are central to implementing the Offshore Renewable Energy Development Plan (OREDP) and to enabling research and development of ocean energy (technology push), respectively.

The Portuguese MSP was adopted in 2019 and includes zones for ocean energy development. The Planning and Management of the National Maritime Space (LBOGEM) defines the legal framework that allows for the implementation of MSPs in the whole national maritime space, from the baselines until the extended continental shelf (beyond 200 nm). In 2019, the National Maritime Spatial Plan (PSOEM) was approved, establishing the licensing regime for private use of the maritime space including marine renewable energies. The Ministry of the Sea, through the Ocean Office, is responsible for the National Ocean Strategy (NOS) 2021–2030, the current public policy instrument for the sustainable development of the economic sectors related to the ocean [31] and approved in May 2021. The Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) is the main Portuguese R&D funding body.

There is no specific ocean energy program nor a specific organisation working on its development in Spain. In 2019, the Spanish Government presented the country’s maritime space management plans under the Strategic Energy and Climate Framework, which includes the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030 setting targets of 25 MW of installed capacity for 2025 and 50 MW for 2030 for ocean energy. MITECO is the MSP authority, sharing maritime and coastal affairs with the regional governments.

The UK Government’s department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) is responsible for the overarching energy policy in the UK, although powers related to planning, fisheries and the promotion of energy efficiency are devolved to the governments of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and Innovate UK are two relevant funding bodies for the development of new technologies. The UK Marine Policy Statement (MPS) provides the overarching policy framework for developing marine plans. The preparation of marine plans is the responsibility of the respective governments within the UK. A total of 11 marine areas are expected to have a marine plan with a long-term view of activities by 2021, which will be reviewed every three years. The Scottish Government continues to support the ocean energy sector including ongoing funding through Wave Energy Scotland and the establishment of the Saltire Tidal Energy Challenge Fund in February 2019 to accelerate the commercial deployment of tidal energy in Scottish waters (technology push). To provide a significant support to marine renewable energy, the Scotland’s National Marine Plan was reviewed in 2018, while the Welsh National Marine Plan was launched in November 2019. Significant funds were allocated to the Welsh European Funding Office Marine Energy Fund, led by Marine Energy Wales, to meet ORE targets for 2030. The marine plan authorities responsible for developing Marine Plans are the MMO, Marine Scotland, the Welsh Government, and the DAERA. The Crown Estate carries out periodic tendering processes for ocean energy areas, for which SEAs are carried out. The Marine Renewables Industry Association (MRIA) supports the development of technology in ocean energy across Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and published a “Discussion Paper on the Marine Spatial Planning Needs of the Marine Renewables Emerging Technologies” in 2018.

In Denmark, the legislation falls under the Energy Agreement (Energy Bill) for the period 2020–2024 and the Promotion of Renewable Energy Act. The “Maritime Spatial Planning Act’,’ which establishes the framework for spatial planning in the Danish marine areas, is expected to enter in force in 2021. In Italy, ORE is regulated by D. Lgs. 387/2003 referring to RE in general. Ricerca di Sistema is the public research program supporting R&D in marine energy. In Norway, ORE falls under the domain of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) and is regulated by the Ocean Energy Act, published in 2020.

There is currently no legally binding MSP for Italy nor has the country declared an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). However, guidelines containing criteria for preparing MSP were published in 2017. In Norway, 15 areas have been identified potentially suitable for large scale offshore wind power deployment. In Sweden, three national plans covering the territorial sea and the EEZ were submitted by the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) to the Government in December 2019. These should be adopted in the second half of 2021.

3.3. Licensing Procedures and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)

The consenting and permitting process starts at the beginning of the project, as even the preliminary investigations and environmental studies require authorisation from the relevant entity. The process includes other requirements, such as the legal right to use the public domain (seabed, sea area, foreshore) for the purposes of ocean energy generation, an authorisation to generate electricity, a grid connection license, and permission for onshore works.

The number of authorities involved in the consenting process depends upon the governance system in place. Some countries have a “one-stop-shop” approach, where a single authority is responsible for the licensing approach, aiming to streamline the process for developers. This is the case in France, Italy, Norway, and Scotland. Conversely, in Spain, there is no specific organisation responsible, and developers must deal with six organisations to obtain the necessary permits. Guidance on the consenting process exists in few countries to assist developers in navigating the consenting process and in addressing uncertainty when making licensing decisions. Countries such as Denmark, France, Portugal, and the UK (Scotland published a Consenting and Licensing Guidance in October 2018) are the exception. In all countries, the issuance of consenting and licensing processes are submitted to the results of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). An EIA is a localised environmental assessment conducted by a developer to ensure policy and legislation decisions permitting development are informed by the best possible evidence about the relative importance of the environmental perturbations generated.

A summary of the consenting process by country showing the typical timescale plus the number of authorities and consents is provided in Table 2. This section presents a summary of the main parameters of the consenting process, including the environmental impact assessment, marine spatial planning, and licensing in test centres, with examples for the different countries under analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of the main aspects of the consenting process for ocean energy. Adapted from [34].

The national Danish Energy Agency (DEA) operates as a “one-stop shop” for the ocean energy project developer, granting all licenses for all projects within 200 nm. The DEA conducts hearings with other regulatory authorities and relevant local municipalities at the pre-establishment phase of a project to address major concerns. On a case-by-case basis, the DEA can require an EIA as part of the licensing process. Three licenses are required: the license to carry out preliminary investigations (e.g., seabed surveys), the license to establish the offshore site, and the license for power generation.

There is still no dedicated consenting process specifically addressing ocean energy in France. The “application decree for envelope” permit was published in December 2018 and grants the obtention of an environmental authorization and the legal right to use the public domain for projects with variable characteristics, giving more flexibility to ocean energy developers. The État au service d’une société de confiance (ESSOC) law, voted in August 2018, streamlines the legal framework, thus significantly reducing delays for the offshore renewable energy sector. This procedure, inspired by procedures put in place in countries such as Denmark and the UK, moves most of the obligations upstream of the actual permit issuance, thereby considerably reducing the risk for project developers and allowing for more flexibility. As a result, once the public consultation and competitive process is complete, the winners will be able to apply for the envelope permit as soon as they are designated. This will include the concession to use the maritime domain, the environmental authorisation, and the operating license. The final environmental approval issued by the Prefect strongly depends on the Environmental Authority report on the EIA. The Prefect operates as a single licensing authority responsible for approvals in the process, which, before the ESSOC law, could take six to nine months to be administered and delivered.

In 2019, Ireland has adopted a revised General Scheme of the Marine Planning and Development Management (MPDM) Bill. It streamlines agreements on the grounds of a new single State consent to be known as Maritime Area Consent granted by the Minister for Communications, Climate Action, and the Environment (MCAAE), substituting the current consent regimes under the Maritime Area and Foreshore Amendment Bill. Currently, to deploy a device at sea, the following five permits are required: (i) Foreshore Licence/Lease; (ii) Planning Permission for onshore development; (iii) EIA or an Appropriate Assessment (AA) if a project is in or near a site designated for nature conservation purposes under the EU Habitats Directive; (iv) a license for electricity generation and supply; and (v) a connection offer by EirGrid.

In Italy, all ocean energy components of a project are subject to a single authorisation procedure for renewable energy production, issued by the Ministry of Infrastructures and Transport (MIT). Nevertheless, such authorisation must comply with the legislation in force as to the protection of the environment, of the landscape, and of cultural heritage, and it must undergo a complex administrative procedure involving a variety of stakeholders.

Whilst there is no over-arching dedicated consenting system for ocean energy in Portugal, the following six consents must be obtained: (i) concession, license, or authorisation for the private use of marine space (TUPEM); (ii) reserve capacity; (iii) production license; (iv) exploration license; (v) accessory facilities onshore; and (vi) an environmental impact assessment. The licensing regime for marine renewable energies development was established by the National Maritime Spatial Plan (PSOEM). Following the PSOEM, a developer can apply for all licenses at the same time; however, the procedure to obtain each of these licenses is sequential and there are legally prescribed timeframes for each step of the procedure. For projects with a power capacity up to 10 MW, the Directorate General for Energy and Geology (DGEG) is the authority in charge of licensing electricity production linking with other authorities for specific permits. Consultation is usually required as part of the legal licensing process.

Both the issuance of the TUPEM and production license requires a favourable or conditionally favourable Environmental Impact Statement (DIA). MRE projects not covered in the Portuguese EIA legal system (RJAIA) are subject to an Environmental Appraisal (EA) procedure only if located within Natura 2000 Network. If the project is not subject to an EIA or EA, the developer may proceed in the licensing procedure provided favourable advice on the project installation on the proposed location is submitted to the regional authority (CCDR).

In Spain, there is not a specific organisation responsible for the implementation of any ocean energy programme, and no dedicated consenting process exists for ocean energy technologies. However, there are several legal documents affecting ocean energy projects, and all projects subject to the production of energy on the marine environment are subject to a simplified environmental impact assessment process. There is no pre-application consultation, which means project developers directly enter a complex licensing system involving several regulators. Similarly to Portugal, Spain has implemented a parallel processing procedure, but required consents are still interdependent. The Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic challenge (MITECO) is the central authority responsible for passing the applications to the other regulatory authorities for comment and for final approval of the four main permits: environmental assessment, occupation of the marine space, electrical developments, and planning permits. Consultation is usually required after the EIS is delivered to the authorities for approval.

The UK has legislation and regulations dealing solely with the consenting process for ocean energy. The licensing system is complex since consents are required at several levels of government. Consenting processes are different among the constituent jurisdictions of the UK, varying from dedicated procedures for ocean energy in Scotland to more general procedures for Marine Licences in Wales, England, and Northern Ireland. Before applying for a Marine License, developers of small-scale projects must acquire a seabed lease from the Crown Estate. In general, the Marine Management Organization (MMO) consents to construction and operation of any offshore generating stations with a capacity between 1 and 100 MW. The MMO decides on a case-by-case basis during the pre-application consultation if the EIA is required. In England and Wales, projects with a capacity under 100 MW require a marine license under the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009. Furthermore, offshore waters, marine licenses, Section 36/A consents, and safety zones are determined by the MMO. The Marine Scotland Licensing Operations Team (MS LOT) acts as a “one stop shop” for the consenting process in Scotland. The authority administers the complete licensing process for all Section 36 and marine license applications in Scottish waters. Its streamlined consenting process simplifies and consolidates the supporting legal framework for ORE.

To support MSP, some countries use a strategic environmental assessment (SEA). SEA is a systematic decision support process, which identifies the likely significant environmental effects of implementing plans to develop. In contrast to an EIA, a SEA is a broader assessment conducted by a government to manage the use of an area. Sometimes this is part of a broader MSP process, which can remove some of the burden from the developers and helps identify suitable locations for development. Both Scotland and Ireland have conducted SEA for all MRE projects. Spain conducted SEA for offshore wind, and the scoping process for the SEA of the Spanish MSPs is currently being drafted. In Portugal, SEA is mandatory for the SP, which was already performed and published in 2018. In France, suitable areas for development are identified by the state along with any conflict of use and technical constraints in a given area. Other countries such as Norway and Italy have not yet conducted any SEA nor do they have a specific MRE plan.

Licensing Process in Offshore Test Centers

Since open sea test sites are pre-consented, developers do not have to undertake a full consenting application. However, they are still required to demonstrate that they respect pre-defined test site conditions. The level of licensing required at test sites varies by country and site, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Licensing procedure in test centres.

4. Results—Barriers and Enablers to the Legal Framework

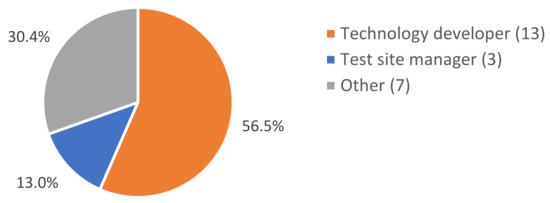

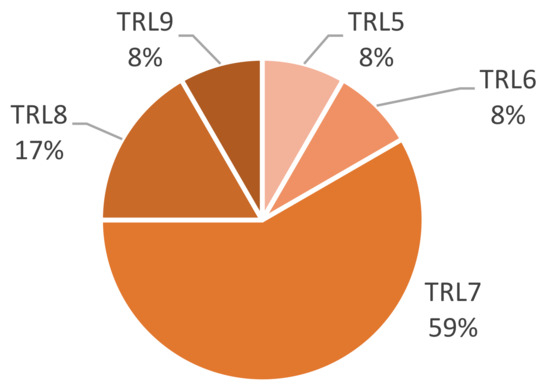

This section presents a thorough analysis of the existing barriers and enablers to the ocean energy legal framework supported by the questionnaire’s results. Twenty-three valid responses were received from stakeholders. According to Figure 2, the largest fraction of responses came from technology developers (77% of those were from the wave energy sector). About 70% of the technology developers were at TRL 7 or above, as shown in Figure 3. Approximately 70% of these have deployed their technologies in test sites. A total of 11 different countries are represented in the sample. The “Other” stakeholder category corresponds mainly to consultants working in the sector but also includes regulators and research and technology organisations.

Figure 2.

Survey respondents—stakeholder categories.

Figure 3.

TRL of concept for technology developers.

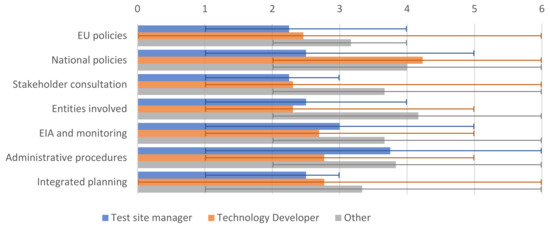

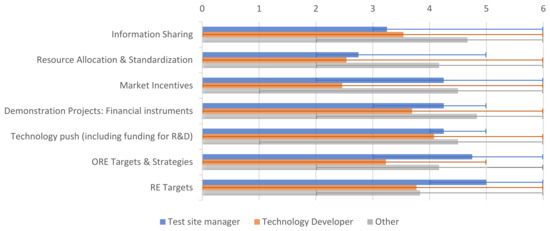

Once the background from survey respondents was collected, respondents were asked an introduction question to set the scene. They were shown a list of factors that had been previously identified in the literature review in Section 3 (e.g., EU policies, administrative procedures) as potential sources of challenge and opportunity to the ocean energy sector. Respondents were then asked to rank each factor, based on their experience, according to the level of challenge that each parameter poses to project deployment. The prioritisation allowed quantitative results to be acquired from a somewhat qualitative assessment. Figure 4 shows the overall perception of the respondents on the level of challenge each of the parameters under analysis pose to project deployment. Each parameter was ranked on a scale from 0 (no barrier) to 6 (significant barrier), and the average scores and range of responses were then represented in Figure 4 for each group of stakeholders. Survey respondents were then asked a list of questions related to each factor, and the analysis of their responses was compiled in the following subsections. The survey responses were compared to the findings in the literature review, and the most relevant statements taken from respondents’ written responses were integrated along the text, highlighted in italics.

Figure 4.

Overview on respondents’ perceptions. Shaded bars show mean result; error bars show range of responses. (0: no barrier/enabler; 6: significant barrier).

4.1. EU Policies and Legislation

Figure 4 shows that all respondents who considered that international policies do not represent any form of barrier (ranked as a 0) were technology developers. At the same time, technology developers’ replies ranged from 0 to 6 when asked to rank this parameter. According to the answers to the open question on this parameter, it seems that EU policies have been increasingly perceived as being enablers to project deployment. Within this parameter, respondents were also asked about their views on the extent to which each of the main policy mechanisms enable project deployment (see Figure 5). Each parameter was ranked on a scale from 0 (no enabling potential) to 6 (significant enabling potential), and the average scores and range of responses were then represented in Figure 4 for each group of stakeholders.

Figure 5.

International policy mechanisms—respondents’ perceptions in respect to enabling potential of EU policy mechanisms. Shaded bars show mean result; error bars show range of responses. (0: no enabling potential; 6: significant enabling potential).

Following the analysis carried out, international policies might be perceived as barriers or enablers on the grounds of the following set of seven aspects:

- Transposition of EU legislation into national law. Often the way EU Directives have been translated into national legislation presents hurdles. This can be difficult to surpass where there is a lack of clarity on how these should be applied to ORE. Additionally, specificities and implementation vary across member states. Natura Directives promotes precaution and can weaken risk-based consenting such as Survey Deploy Monitor (SDM) methodology. Requirements from the Birds and Habitats Directives are leading countries such as Spain to avoid these designated sites. In France e.g., there are many designated sites, which makes it inevitable to overlap projects in such areas. In the UK, there is a perception that these Directives have been adapted too harshly and that the regulators’ interpretation is too strict, especially concerning the precautionary principle. According to the literature, several developers choose not to move forward when confronted with the requirement to conduct long-term monitoring and mitigation actions in compliance with the MSFD. The newly reviewed EIA Directive [36] does not include specific considerations on wave and tidal energy. EU legislation fails at requiring member states to report the status of receptors such as water bodies and seabed bathymetry (some obligations are in place for seabed mapping but with a focus in the presence of particular habitats and species), which hinders information gathering.

- Unrealistic ORE targets. Policies do not work well where policy makers and funding agencies have excessively high expectations regarding time and cost, which may come as a result from unrealistic ORE targets. For developers, this leads to significant pressures for fast deployment in short timescales, both at an economic and a political level, and to a race towards commercial readiness. Consequently, there is an incentive towards the development of end products, rather than engineering results. Although RED II approval was overall considered a success, the new target did not reach the 35% intended by some national governments in the European Parliament (including Portugal), which believe that the approved target is insufficient to reach the desired impact. Nevertheless, survey results show that ORE targets are seen as an international policy mechanism with enabling potential.

- Unsuitability of funding schemes. Optimistic deployment forecasts, which have pushed the sector to achieve large-scale deployments in the short-term, are possibly misaligned with the type, and level, of funding available to the ocean energy sector. There is a widespread concern about the suitability of certain funding mechanisms made available and their ability to realistically meet the level of expectation placed on the sector in terms of deployment capacity and performance. However, the allocation of funding support mechanisms is not suitable to allow initial deployments to take place [40]. Survey results show that technology developers feel Technology Push mechanisms (including funding for R&D) to be a significant barrier to project development (Figure 5). As one technology developer responded, “With no clear market, through grants or feed-in tariffs from EU or national funds, there will be no projects deployed”. There should be consideration for developers of small-scale technology that may also have array projects in the pipeline, as there is currently not a route to securing similar funding support as for the larger scale projects [41].

- Policies dedicated to the RE sector as a whole. The results suggest there are concerns over the development of the sector being hindered because of frequent not-fit-for-purpose policy support mechanisms to ORE in particular [42]. Political pressures arise from competition with other renewable energy sectors that may offer a more competitive and attractive cost for policymakers [43]. Where policies and regulatory regimes are applied at an aggregate level, the less-developed ocean energy sector cannot compete with, e.g., offshore wind. The literature points to the notion that tidal and wave energy are at different stages of development and would therefore need different models of financial support. Furthermore, positive feedback on the precommercial procurement model chosen by Wave Energy Scotland is repeatedly given. In both the cases, the scheme aims to trigger convergence, while spreading support to sustain competition [44]. Nevertheless, there is a general view that obstacles are being overcome, and public policies are slowly being put in place at international level to tackle barriers originated from risks and challenges associated to ORE development. A technology developer stated that “There is a significant number of European projects currently dedicated to marine energy projects”, while another mentioned that “At present, EU policies support the industry through capital and operating costs associated with construction and deployment, mainly for tidal energy.”

- Pressure into reaching large scale. The industry recognizes the need for large utility scale deployments as an essential part of meeting the EU ocean energy deployment targets. However, the ambition to quickly reach large-scale deployment has historically led to premature project failures in the ocean energy sector. Enhanced technology push support should help address the continued requirement for earlier stage R&D funding in the EU, in a structured manner. This will facilitate development of technologies and subsystems that may play a future role in cost reduction and performance improvement within ocean energy technologies. Pressure into reaching commercial readiness usually come in the form of financial pressures through the requirement to provide returns to investors.

- Benefits of information sharing. Openness about results, be it successes or failures, is essential to accelerate the commercial readiness of the sector. Hence the crucial role of platforms for information sharing. Experience shows that policies work well where funding policies are flexible. This is the case where they change quickly in response to industry needs (as in Scotland; see Section 3) or where agents work closely with industry. Policies also succeed when there is collaboration with universities and utilization of local resources (positive for market development). Shared information and experiences improve investor confidence, which in turn accelerates investment and commercialization. Nevertheless, there seems to be a lack of cooperation within the sector, i.e., on a public–private level, amongst industrial actors and between national and European funding authorities.

4.2. National Policies

Figure 4 shows dispersed opinions across participants regarding the role of national policies as to whether it should be considered a barrier or enabler to project deployment. These results can be justified by the diversified level of development of the ORE sector in the countries represented in the sample. The following four aspects were identified:

- Unrealistic targets lead to loss of credibility: As previously mentioned, most countries active in the sector have set firm targets, which demonstrates their willingness to invest and develop the sector, but very few have specific policies to promote ocean energy uptake. Under the EU27 NREAP scheme, the ambitious targets set for renewable energy in 2020 are not substantiated with actual projects, as these targets were driven by the top-level member states’ energy policy. With recent adjustments to the 2020 deployment targets across various member states, deployment trajectories for the ORE sector have been drastically reduced compared to the earlier 2020 targets. Ocean energy technology must deliver on the updated targets; otherwise, there is a real risk that the sector could lose credibility amongst supply chain companies and policy makers. As one technology developer mentioned “There is no national or investor expectation to wave energy [in Denmark]”. On the other hand, some experts argue that National Renewable Energy Action Plans (NREAP)/National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) targets, despite being realistic, could be set at a higher benchmark with a more encouraging policy framework.

- Lack of dedicated policy mechanisms: A rather insufficient number of governments have national research & innovation, market deployment, and market-based energy policies that are open to ocean energy. Learning costs cannot be funded exclusively by research or innovation grants. Alternative mechanisms currently in place for ocean energy translate in feed-in tariffs but are often absent or are not specific for ocean energy. As one test site manager put it, “At the moment, in Spain, there are no national policies to push renewables and the governmental lack of support tends to hinder this kind of projects”. Few countries use industry or supply chain initiatives specifically for ORE developments. Countries such as France, Ireland, Portugal, and the UK have implemented upfront capital and funding programs for the deployment of ocean energy projects [45]. Some respondents state that “There’s a lack of streamlined policies and market support for tidal stream energy at national level”. A technology developer emphasized this view by answering that “There are no clear and specific policies on different levels—municipal, governmental, and regional—for wave energy promotion”.

- Governance fragmentation and lack of motivation: Most countries have a fragmented governance structure with responsibilities spread across numerous Government departments, agencies, etc. There is little political appetite for greater integration e.g., in Ireland and Portugal. Moreover, policies may change according to government mandates and parties. “In some countries, the relevant organizations lack processes and are not able to clearly communicate the steps necessary for project execution”, as claimed by a technology developer. The long-term nature of ORE might lead to a lack of political will [46] and ambition regarding prioritization, strategy, and support to the sector. Additionally, “National policies are constantly changing, especially in the UK, which makes it very difficult for tech and project developers to plan for project and investors”, as backed up by a technology developer. As a result, no bold aims or targets are set, making it more difficult to push for action. Government motivation and investment is critical to making ocean energy technologies viable. Moreover, government commitments also encourage and support the larger contribution from public and private investors. Support from policy makers is crucial for the development of the sector. As a consultant in the sector mentioned, “National policies are very important to implement and/or promote initiatives to support the development of the ORE administrative and regulatory context as well as national financial incentives”. Very few countries have long-term government ambitions regarding prioritization, development strategy, and support.

- Insufficient national funding schemes: In Ireland, for example, developers highlight “difficulties with funding”, particularly the cost of testing devices in the lab and at sea. On the one hand, the Irish Government is unwilling to take environmental risk. On the other hand, national policy has been a significant driver for economic growth in the marine sector, and the recent revision of foreshore consenting through the publication of the MPDM Bill (Marine Planning and Development Management Bill (MPDM), General Scheme, Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government.2019) presents a significant opportunity to enable the ocean energy sector in the country [47]. The lack of national investments in Italy impairs the participation of Italian actors in co-funded EU programs and their access to co-funded financial instruments. One dampener relates to the unknown impact of Brexit on ocean energy and the general difficulty surrounding tariff supports and policy generally for renewable energy in the UK.

4.3. Administrative and Licensing Procedures

As Figure 4 shows, opinions regarding the role of licensing procedures are fairly spread among the respondents. This can be justified with the fact that the consenting process varies in great degree from country to country. This topic received more attention from the survey respondents, judging by the number of opinions provided through open-ended answers. A first set of six issues is detailed in this section for the licensing procedures as a whole. This is followed by a detailed description of barriers and enablers identified for three subtopics that comprise the licensing procedure: environmental impact assessment (EIA), integrated planning, and stakeholder consultation. In general, respondents across all groups of stakeholders mentioned the high complexity of administrative procedures.

- Lack of a streamlined process: Overall, there is a lack of streamlined processes for the licensing and permitting of ocean energy projects. “The lack of streamlined admin between EU countries and UK countries as well as different organizations within one country adds significant administrative burden to our company,” according to one of the technology developers. On an international level, there is an absence of recognized performance assessment guidelines and standards, with few exceptions, e.g., in Portugal [48]. In some countries, guidance has been produced for offshore wind, but it is unclear to developers whether it can also apply to ocean energy. As one technology developer put it, “If consenting and insurance is required as if it was an offshore oil and gas installation, it is a showstopper for young companies”.

- Challenging interpretation of legislation: Lack of dedicated legislation for ORE leads to unsuccessful attempts to apply existing legislation to developments and responsibilities distributed among entities in the sector. This can make it difficult for a developer to interpret legislation and navigate the process. This poses a barrier as getting a clear view on who should be involved, at what stage and for what purpose, can be very time consuming. As a result, technology developers do not move forward with certain projects because of delays and extra costs, and financiers become reluctant to invest. This is backed up by several respondents (particularly technology developers): “Administrative procedures may compromise the timeline of approval with effects on investment availability”. A test site manager also shared concerns on the potential risks of this barrier: “The licensing procedure [in Spain] is long and hard to follow and, in the end, can last around five years, which could end hindering and even bringing down a project”. Exceptionally, in Portugal, all the consents required have been adapted to better suit wave energy developments, i.e., there is a specific law or instrument on every topic of the consenting process, which makes the laws easier to understand.

- Fragmented approach: Generally, countries that have complex jurisdictional arrangements and no dedicated legislation for ORE tend to have more entities involved, and a larger number of permits required. This fragmented approach in most countries suggests there is limited experience with one coordinating authority or a “one-stop shop” approach [41]. One successful exception could be the UK, which seems to be the most streamlined, operating a “one window” approach to the administration of consents. The consenting process for a 10-device farm in an EU country required a developer to submit 35 copies of the technical report to be then submitted to 35 different entities. In BiMEP, Spain, the consenting process took almost five years because of the number of authorities involved, and for many of them it was their first experience processing an application for an ORE: “We spent 5 years to obtain the permits for wave energy at BiMEP. And another 5 years to modify them including wind energy”. In Ireland, developers point at difficulties obtaining a foreshore license to test their devices in the sea, with a number of government entities involved in a process that can take years [47]. Another technology developer shared a similar experience: “We were supposed to install a demo system in a non-test site. Due to a very long consenting process we will probably have to re-locate to another location resulting in delay and extra costs”. These diverse experiences in the role of entities involved in the consenting process is illustrated by the respondents’ dispersed answers when ranking the topic, as shown in Figure 4.

- Lack of specified timeframes: A lack of specified timeframes for decision making hinders development as it can result in a lengthy process. If one stage is delayed, the developer cannot proceed to the next. “Depending on the country of deployment, the administrative procedures due to paperwork, translations, etc. can delay the whole project plan,” a technology developer mentioned. Criteria used to support decision making are unknown to the public and missing in several countries. As an example of good practice, Scotland has a policy target of deciding on an application within a certain timeframe, which is helpful to developers as they can plan and budget for their project more precisely. There are also fixed timeframes in Portugal, but these have had limited success in practice.

- The consenting process is in constant change: This is a commonly felt barrier, as the feedback provided through the survey’s open-ended questions show, that leads to hardship in following the updated procedures, which in turn hinders the development of the sector. Changes in government or internal restructuring can result in a loss of knowledge within the consenting authorities. The changing nature of the consenting process coupled with a lack of communication and cooperation between different government bodies affects the overall process efficiency and duplication of effort.

4.3.1. EIA Process

The EIA process is predominantly felt as a barrier by the “others,” which is understandable as this includes consultants, regulatory bodies, and stakeholder groups more directly involved in the consenting process of ORE projects (Figure 4). On the one hand, planning environmental monitoring is considered a challenging process. On the other hand, methodologies such as the survey deploy monitor approach, already successfully implemented in Scotland, have been drawing attention given its effectiveness in addressing the typical weaknesses in the EIA process. According to the results of the survey, the challenges imposed by the EIA process can be grouped into eight different points:

- Lack of data from previous experience: In other sectors, environmental impact assessments are based upon knowledge and data from past experiences. This allows regulators to put in place rules, based on pre-established risks, that prevent environmentally damaging projects from moving forward. However, to date, there have been few deployments for ocean energy, so this knowledge base is still being built. There is still no comprehensive body of evidence that regulators can use as a basis for consenting and licensing decisions. The lack of baseline databases for marine environments along with non-strict monitoring requirements (in amount and length) in countries like Ireland and France requires developers to submit up to two years’ worth of monitoring data. This poses a barrier to the implementation of risk-based methodologies such as the SDM approach in place in Scotland.

- Difficulty in predicting potential impacts: There is still a lack of understanding of the interactions of ocean energy devices with the environment. Monitoring potential impacts of these devices is likely to be extremely challenging given the relatively small spatial scale of existing sites, coupled with natural stochastic variation that will inevitably influence how animals use and respond to the marine environment. From a test site manager’s experience, “This usually requires developers to demonstrate that any potential impact is going to be mitigated even though there is no research on that so far”.

- Mismanagement of monitoring requirements: Insufficient guidance and legislation that addresses small scale and time-limited projects such as ocean energy projects is specially felt on EIA matters. Developers are often required to gather what they feel is unnecessary or duplicated information. At the same time, the precautionary and overly risk-averse approach adopted by regulators because of unfamiliarity with the sector [49] leads to EIA specifications based on “what” a consenting authority wants a developer to assess instead of “why” these issues need assessment. This results in developers being asked to study the effects of a small project as if it were a full-scale development. Conversely, the more available data there is in the beginning of the consenting process, the easier it is for the developer to go through the early stages of the consenting process. As a member from a Research & Technology organization states: “According to my experience, the administrative procedure in Spain is long and difficult. In one hand because marine renewable energy projects are not included in the EIA legislation. This forces the administration to undertake a long consultative procedure involving different stakeholders. During this procedure, different entities with different competencies and interests are involved”.

- Excessive EIA studies costs on developers: According to the literature, there is a general opinion that public funds are needed to enable deployment but also to partly cover costs associated with EIA studies that are currently entirely paid for by developers. The burden should therefore be shared between developers and governments from all EU member states interested in the output.

- Lack of integration with onshore EIA requirements: There is currently no single EIA procedure that includes both onshore and offshore elements. Consequently, and according to the survey results, some developers have experienced issues during the project’s onshore installations’ planning, which were paused by the local governments.

- Pre-application consultation benefits: In some countries like Portugal and Spain, the scoping phase is not strictly mandatory (in Spain for Annex I projects, the decision is left for the developer; for Annex II, it is mandatory). This means the developer and the competent authority meet for the first time when already submitting application for consenting. In other cases, like France and Ireland, pre-application consultation is compulsory (in Scotland, it is only compulsory for marine licenses but not for consenting application, but it is common practice), which allows developers to benefit from regulators’ expertise early in the process.

- Inefficiency of post-consent monitoring: There is growing evidence that post-consent monitoring programs often result in data-rich information-poor (DRIP) studies that are unable to meaningfully reduce scientific uncertainty and thereby provide information that can offer greater confidence to decision makers regarding future project proposals (or meaningfully inform future decision making).

- EIA in pre-designated areas: EIA occurs late in the project after the developer and the main characteristics of the project have been chosen, which makes it difficult to introduce changes in the project design accordingly.

4.3.2. Integrating Planning

The respondents’ perception on the role of integrated planning in the development of the sector varied across the spectrum of scoring. A total of four topics were identified as barriers related to this parameter:

- Early stage of MSP implementation: Marine spatial management is a critical issue to regulate potential conflicts with other maritime activities over the use of coastal space. As detailed previously, few countries are at an advanced stage of MSP implementation, but those that do rarely reflect ocean energy developments such as reserved and pre-allocated ones, or future needs of the sector. This could be attributed to a lack of communication with ocean energy representative entities. “…the lack of clear national policies and MSP for future marine renewable energy project developments makes more difficult the consenting procedures of this kind of projects”, as a respondent mentioned. A consultant in the sector stated that “MSP can help discussions among developers and other users and stakeholders on marine spatial occupation”.

- Lack of flexibility: There is a lack of flexibility in the planning system to incorporate changes in the technology or overarching project plan. “Marine spatial planning tends to over-generalize and be less fit for purpose at the local level”.

- Incompleteness of information: On the one hand, information on constraints in areas proposed for project development is not enough for a technology developer since they feel the need to specify the best areas. This approach empowers the developer with a higher level of certainty. Furthermore, there is a general belief that outcomes from the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) process do not provide developers enough confidence regarding decision making on the most suitable areas for project development. On the other hand, investors do not have access to information in advance on the available areas for project development: differences between acceptable areas and sensitive areas that may pose additional regulatory hurdles.

- Effectiveness of pre-allocated zones: Technology developers show indecision on the effectiveness and helpfulness of MSP at its current level of development. There are mixed opinions on whether pre-allocated zones (excluding test centres) are advantageous since they have resulted in very few deployments. Existence of pre-allocated zones could make it more difficult to deploy in other areas of the sea. It is a particularly relevant concern since ocean energy has different technologies with differing/distinct operating environments. On the other hand, the designation of dedicated areas for ocean energy can lead to shorter consenting timelines and fewer risks and thus help advance the development of the sector.

4.3.3. Stakeholder Consultation

The majority of respondents perceive stakeholder engagement as an enabler to development of the sector. This section however analyses the parameter in deeper detail, identifying both advantages and disadvantages associated to it.

- Inappropriate stakeholder engagement: Ocean energy deployments can experience significant delays resulting from local communities’ opposition if stakeholders are not correctly engaged, as mentioned by one survey respondent: “Stakeholder consultation and entities involved: may compromise project execution and installation schedule if not done in a proper way (considering all stakeholders—being inclusive—and listen to stakeholders opinions trying to integrate their views in project decisions)”. This can be especially challenging in regions with strong fishery or tourism sectors. These tend to be more reluctant to embrace marine energy projects, which can compete for space with such activities. Issues potentially arise when consultation is not transparent and realistic enough about the desired achievements regarding effects of the project for the local community, be it employment schemes and local share of profits or potential negative environmental impact. However, it seems to be generally easier to secure participation at the regional level than the national level. Beyond 12 nm, marine users are international, and therefore it is more challenging to engage stakeholders in the planning and development process.

- Inadequate consultation: Informal consultation is seen as more constructive but tends to be focused only on high level groups, often excluding the public in general. For example, local government knowledge of relevant environmental impacts is often poor, leading to poorly supported opinions on negative impacts. They need more time and money to become familiar with the scientific state of the art knowledge of impacts. However, a technology developer that participated in the survey shared an opposite view based on their experience, “Proper stakeholder consultation at the local level has been an enabler—90+% of locals are supportive of what we do and the local benefits we bring”.

- Effective dissemination of the sector achievements: Sharing successes of the sector is crucial to increase stakeholder acceptance. Currently, not enough success stories about ocean energy projects are disseminated on a national level to the general public and consenting authorities. This does not help increasing acceptance of this relatively unfamiliar sector. Regulators, for example, are still unfamiliar with the ocean energy sector, which leads to a precautionary and “risk averse” approach to project consenting. A technology developer shared the same views, “We see the involvement of entities and stakeholders as a strength and not a barrier, and our technology has the advantage to be invisible, clean and silent so we have no problem”.

- Unsuitability of stakeholder consultation: Insufficient attention is often provided to the inter-personal elements of stakeholder consultations. Firstly, the inconvenience of timing and the location of consultations for stakeholder groups can lead to low attendance and engagement with the process. The unsuitability of the consultation methods to the audiences whose input is sought can be illustrated by e.g., the use of a limited range of communication media or by not selecting suitable people who are respected and trusted by individual target audiences. It can also be revealed through overformal procedures and under-use of informal and interactive consultation methods and lack of opportunities for regulators and developers to listen to stakeholder opinions [50]. Moreover, national strategies for stakeholder engagement are not always accepted at the local level.

4.4. Summary of Main Findings

Table 4 summarizes the main findings and key issues derived from the analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of main findings.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate and identify the main legal and political barriers and enablers to deployment of ocean energy. The study was structured in two main parts. Firstly, a literature review on the existing policies, legislation, and consenting processes for ocean energy projects was carried out for European countries. In a second stage, the positive and negative impacts of the existing national and international frameworks on the ocean energy sector were evaluated. For this purpose, a questionnaire was conducted amongst targeted stakeholder groups to identify potential barriers and enablers and to quantify impacts of the established national frameworks. The questionnaire was mostly aimed at technology developers, test site managers, and regulators.

The results from the analysis suggest that there are several non-technological forces hindering the development of the ocean energy sector. Firstly, legislation governing ocean energy as a specific sector is rare, both at national and international levels. ORE targets are often unrealistic, and funding schemes are unsuitable, leading to loss of credibility and making investors reluctant to invest in the sector. There is also a general governance fragmentation and a lack of political ambition, which is illustrated by insufficient national funding.

Moreover, the consenting process appears to be a major source of barriers. Lengthy procedures linked to a lack of clarity, fragmentation of the consenting authority across multiple consenting agencies, and a lack of a streamlined process are some of the most frequently cited barriers to issuing consent for ocean energy projects. Regarding the environmental impacts, uncertainty resulting from an absence of data from previous experiences, mismanagement of monitoring requirements, and lack of integration with onshore EIA requirements are some of the main perceived barriers. Finally, issues also arose regarding the early stage of MSP implementation and the lack of flexibility and incompleteness of information regarding integrated planning as well as doubts as to the effectiveness of pre-allocated zones for the deployment of ocean energy devices.

Conversely, although in a more discrete approach, some topics seem to be considered enabling features depending on the perspective adopted. Among them, the analysis carried out identified the growing supportiveness of the current EU policies and the importance of national policies as enablers to the creation of national financial incentives. Furthermore, MSP is considered a supporting tool for stakeholders involved in the process, and the involvement of the most relevant entities in the consenting process is mainly seen as a strength or enabling factor.

The present study reinforces the need for a dedicated legal framework for ocean energy. Moreover, more financial support for continued research and demonstration should be provided at the international level by launching new funding mechanisms specific to the sector. Consenting procedures need to be transparent, more efficient, and cooperative. The implementation of a “one-stop-shop” approach should be a priority at the national level to improve the management of the consenting process. Results also show the importance of the development of guidelines and strategic and integrated plans such as MSP. The present analysis represents an important step in the development of the sector, clarifying barriers and potential enabling factors so that these can be addressed and enabled, respectively.

Author Contributions

Methodology, M.A.; formal analysis, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A., R.F.-G., D.R.N., F.X.C.d.F. and J.H.; visualization, M.A. and D.R.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partially supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 785921, project DTOceanPlus (Advanced Design Tools for Ocean Energy Systems Innovation, Development and Deployment).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data (anonymised) that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to ensure privacy of survey participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 1998. Paris. 1998. Available online: https://jancovici.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/World_energy_outlook_1998.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2019. OECD. 2019. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2019 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Available online: https://www.dtoceanplus.eu/Publications/Deliverables/Deliverable-D8.2-Analysis-of-the-European-Supply-Chain (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Press Release: Blue Growth Strategy to Create Growth and Jobs in the Marine and Maritime Sectors Gets Further Backing (June 2013). 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_13_615 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuindeau, B. Territorial Equity and Sustainable Development. Environ. Values 2007, 16, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uihlein, A.; Magagna, D. Wave and tidal current energy—A review of the current state of research beyond technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 1070, 2016, 58–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outka, U. Environmental Law and Fossil Fuels: Barriers to Renewable Energy (15 August 2012). Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2012, 65, 1679. [Google Scholar]

- Boillet, N.; Guéguen-Hallouët, G. A Comparative Study of Offshore Renewable Energy Legal Frameworks in France and the United Kingdom. Ocean Yearb. Online 2016, 30, 377–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bald, J.; Menchaca, I.; O’Hagan, A.M.; Le Lièvre, C.; Culloch, R.; Bennet, F.; Simas, T.; Mascarenhas, P. Risk-Based Consenting of Offshore Renewable Energy Projects (RICORE). In Evolution of Marine Coastal Ecosystems under the Pressure of Global Changes; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ocean Energy Systems. Consenting Processes for Ocean Energy on OES Member Countries. 2015. Available online: https://tethys.pnnl.gov/sites/default/files/publications/OES-AnnexI-Report-2015.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Painuly, J. Barriers to renewable energy penetration; A framework for analysis. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, C.; Guilherme, P.L.; Esther, M.-G.; Swantje, G.; Stephen, H.; Lars, H. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niquil, N.; Scotti, M.; Fofack-Garcia, R.; Haraldsson, M.; Thermes, M.; Raoux, A.; Le Loc’h, F.; Mazé, C. The Merits of Loop Analysis for the Qualitative Modeling of Social-Ecological Systems in Presence of Offshore Wind Farms. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagna, D. Ocean Energy Technology Market Report 2018. Luxembourg. 2018. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2760/019719 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- European Commission. Horizon2020 DTOceanPlus: Advanced Design Tools for Ocean Energy Systems Innovation, Development and Deployment. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/785921 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- European Commission. Going Climate-Neutral by 2050: A Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate-Neutral EU Economy. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/92f6d5bc-76bc-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law). 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2020-0162_EN.html (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission—The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/communication-european-green-deal_en (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Strengthening Innovation in Europe’s Regions: Towards Resilient, Inclusive and Sustainable Growth at Ter. 2017. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Regional Policy Contributing to Smart Growth in Europe 2020. 2010. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- European Commission. Research and Innovation. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/themes/research-innovation/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Oceanera-net Cofund, Oceanera-net Cofund: Supporting Collaborative Innovation in the Ocean Energy Sector. 2021. Available online: https://www.oceancofund.eu/ (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- European Commission. Horizon 2020 Work Programme 2018–2020. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/wp/2018-2020/main/h2020-wp1820-energy_en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Council of the European Union. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing Horizon Europe—The Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, Laying Down Its Rules for Participation and Dissemination. 2020. Available online: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14239-2020-INIT/en/pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- European Commission. Innovative Financial Instruments for First-of-a-Kind, Commercial-Scale Demonstration Projects in the Field of Energy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7fc3beff-2b55-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 10 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Budget: Commission Proposes a New Fund to Invest in the Maritime Economy and Support Fishing Communities. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4104 (accessed on 30 July 2021).