Abstract

Under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world has pledged to “leaving no one behind”. Responding to goal No. 7 on the agenda, efforts to provide modern energy to all the world population must be pushed forward. This is important because electrification in the rural area can indirectly support opportunities for social and economic development resulting in an acceleration of the eradication of poverty. The research goal of this study is to contribute insights about the scale of energy demand in unelectrified villages in the Southeast Asian countries and to discuss some factors that might influence the energy demand growth. This is done by making projections based on surveys and interviews, including a time-use survey, in three off-grid villages located in Myanmar, Indonesia, and Laos. Our analysis presented the living condition, highlight the types of energy sources, how, and in what rhythms people use energy on a daily basis in those villages. The demands in each case study villages were then projected based on several constructed scenarios. It was found that the factors of household size, proximity to the city, climate, and topography may influence the present and future growth of energy demands in the villages. The estimated energy demand may be useful for project managers to design a pilot off-grid energy system project in a similar environment and pointed out important factors to consider when formulating off-grid energy policies in the region.

1. Introduction

While most of the countries in Southeast Asia aim for universal electrification rate by the year 2020 to 2030 [1], it is predicted that some of the rural population in the region might not be able to have access to electricity by then. This might be due to various technical and financial challenges, such as securing funding for off-grid solutions, challenging logistics, and challenge in finding the appropriate business models [2]. Microgrid solutions using renewable energy is often suggested to respond to those challenges, [3]. Either by combination with grid extension [4] or as a stand-alone system. These solutions are considered as having the more appropriate level of investment costs in catering relatively low density and low-income population in off-grid rural areas [5,6,7,8]. Additionally, there are social and sociological challenges that complicate the conditions such as challenges to encourage people’s interest in investing in new technology [9] and their willingness to sustain the energy system [10]. In 2015, the world pledged to “leaving no one behind” under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Based on this commitment, efforts to provide modern energy to these population in the region must be pushed forward.

1.1. Literature Review

Studies have shown that electrification in a rural area can indirectly support opportunities for social and economic development [11]. Improved access to modern energy can influence critical components of poverty, namely; health, education, income, and environment [12] resulting in acceleration of the eradication of poverty. Due to the relatively high population of the Southeast Asian region, a small percentage of the population without access to electricity equals to several millions of people. For example, there are 1.5%, 6%, 4.7%, and 1% of population in Indonesia, Laos, Philippines, and Vietnam of population without access to electricity respectively that equals to 3.9 million, 1 million, 5 million, and 2 millions of people, respectively [13]. Countries such as Cambodia and Myanmar are especially severe as these countries only have 60% and 40% of their population living with access to electricity respectively [13]. Moreover, the rate of electrification does not say anything about the reliability or the stability of electricity supply, especially in rural areas. Evidence shows that electricity blackout is still often experienced by the end-users in many Southeast Asian countries [14,15,16].

Considering the often geographically challenging access to the rural areas still without access to electricity (for example small islands, villages in the middle of wide agricultural or plantation areas, and areas with challenging terrains), a thorough study is important to formulate and plan the most appropriate solution for each local case to avoid sustainability failures. Specifically, the technical, economic, and social factors should be considered at the local scale [17,18]. Research-wise, it is then necessary to note about how such local-level analyses is positioned in terms of critical perspective and transferability issues; case-based approaches do not aim at inferential generalization, but rather present opportunities for knowledge translation across cases based on critical assessment of similarities and links in order to achieve better understandings and practice-oriented knowledge [18,19]. Additionally, the field survey activities in each of the case study villages can also be aimed to create engagement with the participants. In the process of case village field surveys, networks built at the local level can be used to better plan the actual follow-up electrification projects involving the community, and local government, as well as to create a democratic and participatory environment [18,20,21].

1.2. Aims and Scope

The goal of this study is to present some insights about the scale of energy demand in a typical unelectrified Southeast Asian villages by providing an energy demand projection and simulate growth on the basis of several constructed scenarios. While similar works of using the ecosystem approach to discuss energy use in a community have been done [18,22], such works were done in either in the scope of buildings, in urban settings, or in European countries. Rural areas in the Southeast Asian region may appear as less of economic and political interests while actually, the population living in such an environment is quite significant [13]. Agricultural activities in this region also contribute quite significantly to the national economy in general (for example, the palm oil plantation in Indonesia). It is necessary to explore and support data about the energy use in such areas so that actions from the government or other stakeholders to improve people’s livelihoods can be aided. To achieve our research goals, our research tasks are the following: (1) Conducting field surveys that collect both quantitative and qualitative primary data through interviews and questionnaires. (2) Projecting the energy demand in each village using the collected information. (3) Constructing four different scenarios based on the field survey and projecting the energy demand growth.

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Case study Villages

In choosing the case study villages, we communicated with the local government in each country to identify and choose a village that was still unelectrified. The village managers were contacted to inquire about their willingness to take part in the study. We asked whether they could invite their residents to come to the village assembly hall, to the house of the village manager, or by home visits to respond to our survey. The number of participants were achieved by aiming as many respondents as possible but also by considering the proportion to the village population, how diverse the job of the residents is, and our approaches in collecting the survey based on our resource limitations (Table 1). There are 100 invited participants for the Myanmar case study (total households: 300 with a medium job diversity), 60 invited participants for the Indonesian case study (total population: 60 households with low job diversity), and 60 participants for the Laos case study (total population: 305 households with low job diversity). The Myanmar participants gathered in the assembly hall, which was an open-air medium size hut, the Indonesian participants gathered in the village manager’s house, and home visits were conducted in the Laos study with a speed rate of about 5 households per day. The survey questionnaire was written in English and then translated by our research team members in the respective countries to the local languages. We read each question out-loud to the respondents to help those with limited literacy levels. We also assist them when they were unsure about their understanding of the questions.

Table 1.

Participants’ attributes and survey sample size.

2.1.1. Thae Kone Village (Myanmar)

The village has approximately 300 households or equivalent to about 6000 people. Among the case studies in this paper, Thae Kone village has relatively easy access to Mandalay city, through the village entrance on the 19th street. From the 100 invited respondents answering our survey, there were about 85% eligible answers. The average age of our respondents was 40 years old, with about 30% of them have completed junior high school, 20% high school, 16% university, and 9% elementary school as their last education. The rest of the 24% never went to school. Due to the closer proximity to the city compared to the other case studies in this paper, the type of occupation of the Thae Kone village residents is also the most diverse. They work as tailors, in the military, as government staff, drivers, construction workers, school teacher assistants, saleswomen and men, goldsmith workers, and farmers. While most houses in the villages were made of bamboo, some houses were made by wood and very few houses were made of concrete with the support of diesel engines. The average of a household member in each house is 5.1 persons, and the average household income is 39,178 MMK/household/month or about 28.7 USD/household/month (March 2020 conversion rate).

2.1.2. Karya Jadi Village (Indonesia)

Karya Jadi village is divided into seven communities called Rukun Tetangga (RT). RT is a community unit in Indonesian cities and villages, usually consisting of about 200 households. The surveyed RTs in this study were RT number 6 and number 7 of Karya Jadi village. These RTs are surrounded by hectares of palm oil plantation areas. Due to the remoteness of the villages, there are only a total of about 60 households living several hundred meters apart from each other, and all of them were invited for the survey. All of the invited household representatives attended the survey session, and there are more than 90% eligible answers for analysis. The average age of the respondents was 41 years old, 63% of them completed elementary school as their latest education attainment, followed by junior high school (13%), high school (7%), and vocational school (2%). As the village is isolated in the vast area of palm oil plantation, naturally, the type of occupation of the residents is common, as plantation farmers. There are two major types of plantations in the area: palm oil and rubber trees. A smaller number of farmers also work in the rice plantation. The houses of the residents were commonly made of wood with the kitchen area located above a canal or a small river for direct household waste disposal. A toilet is usually attached or detached from the house positioned above the canal or a small river for direct disposal of human waste. Due to the popularization of “Family planning: Two children are better,” by the national population and family planning agency (BKKBN) back in the 1970s through the 1990s, it is common to see families having two children in Indonesia even presently. The average household size in Karya Jadi village RT 6 and 7 is 3.4 persons, and the average household income is 258,636 IDR/household/month or about 17.97 USD/household/month (March 2020 conversion rate).

2.1.3. Houaykhing and Houayha Villages (Laos)

The Houaykhing (HK) and Houayha (HH) villages, our third case study location, are located side by side within the Houaykhing village cluster, Phonsay District, Luang Prabang Province, Laos. The HK village is populated with 1595 people or 245 households, and HH village is populated with 418 people or 60 households. Our survey respondents were 30 households in each of the villages, totaling 60 households. Because we visited each household for the survey purpose, 100% of the collected survey were eligible for analysis. The average age of the respondents was 43 years old, 77% of them have finished elementary school education as their latest education attainment, followed by 17% junior high school, 4% high school, and 2% university level. The village is located near the forest, and most of the residents are having a common occupation as rice farmers or raising livestock animals in small scales. Houses are commonly made of wood, which can be collected easily from the nearby forest. The average household size in the HK and HH villages is 7.9 people, which is significantly larger than our two other case studies. The average household income is 160,725 LAK/month/household or about 18.05 USD/month/household (March 2020 conversion rate).

2.2. Survey Procedures

The survey procedure and methods chosen in this study have gone through trials and applications for primary data collection in various Southeast Asian countries conducted in our previous studies [23,24]. We also have reviewed various methods, both the qualitative one with semi-structured interviews such as the one done by Sarrica et al. [18] and the quantitative one by Guarini et al. [22]. The approaches taken in this study is the combination of both qualitative and quantitative surveys.

In this study, we selected three villages in the Southeast Asian region located in Myanmar, Indonesia, and Laos as our case studies. There are four parts of the survey questionnaire (Table 2); the first one is about the respondent’s necessary demographic information such as household size, migration activities, and education levels. The household characteristics are known as one determining factor in energy consumption [25]. Most of the respondent had no difficulty in answering this part of the questionnaire. The second part is about energy-use for basic needs related information such as their lighting sources, how do the respondents secure clean water for bathing, washing, and drinking purposes, means of food storage, and source of cooking fuel. This part is to see a holistic view of the different types of energy supporting the daily activities of the respondents. The third part is about household income and expenditure. The last part is a time-use questionnaire to identify the pattern of the daily activities of the people. During the survey, it was found that the time-use questionnaire was too challenging for the participant to answer because it required a multidimensional understanding (place, time, and activities) of the answer table on the questionnaire sheet. However, the time-use questionnaire is a necessary aspect of the study because a self-reported activity is a good predictor of electricity demand [26]. Time-use data analysis could identify the relationship between place, time, and expenditure, and their rhythm [27], which will be vital information to formulate dynamic electricity pricing and to design an accurate load shift controller [28]. To cope with this challenge, we did individual interviews with about 10% of the respondents in each village by asking them to elaborate their activities from waking up in the morning to sleeping in the evening, while the researchers filled the questionnaire sheet itself according to the respondent’s answers. Especially in the Indonesian and Laos case study, most of the respondents have similar occupations (working in the agricultural sector), and through the interviews, it was confirmed that their social activity patterns are quite common. A balanced proportion of women and men respondents were maintained whenever possible (for example, our Myanmar respondent was about 50:50 ratio). When the women residents were not visible, we took the initiative to ask for permission to meet and interview them in a different part of the house (for example, in the Indonesian case study, we approached the female household members gathering in the inner part of the house. They were pleased to participate in the survey). Gender is an essential aspect in rural energy issues as it is known that better access to modern energy could eliminate indoor pollutants (from the traditional use of biomass for cooking) and improve participation of women in education and the job market [9,29]. In addition to the questionnaire survey, we also interviewed key stakeholders in each village, such as the head of the village to confirm our findings and the shop owners who sell vehicle fuels and daily necessities to understand about the local prices and whether there are government subsidies taking place.

Table 2.

Structure of survey questionnaire.

2.3. Energy Demand Estimation Methodology

The methodology used to estimate energy the energy demand in each case study village is the “end-use model” adopted from the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) tools and method for integrated resource planning guideline [30]. While this method is quite old (published in 1997) it is quite fundamental and is still relevant today. The method has also been used in more recent report by the world bank [31]. The formula is as follows:

Qi is quantity of energy service i (hours/year) and Ii (W) is the intensity of energy use for energy service i (W).

The quantity of energy service i, , is identified by the total number of end-use i or (number of household), the penetration levels of appliances for end-use i, or (%), and the number of hours, degree-days or frequency of use for energy service i, or (hours/year). Therefore,

While the survey in this study collected data about all types of energy including non-electricity energy such as the traditional use of biomass, the above equation is only used for electrical appliances powered by various means of off-grid electrification such as the solar panel, diesel, and batteries. Furthermore, because energy demand fluctuates throughout the day, information on social activities from the time-use questionnaire in the survey is used to create the load curve in this study.

2.4. Projection of Energy Demand Future Growth

With the introduction of electricity, the ownership of electricity appliances tend to increase [9,32], on the other hand, many rural electrification programs often neglect the influence of increasing demand [33]. In this study, we addressed this gap by projecting different scenarios of how the energy demand would increase over time, based on observing the current possession of electrical appliances in each case study village and how they would likely to change over time by observing the situations in the three villages and according to the interviewed key stakeholders.

3. The Case Study Country Energy Profile

3.1. Myanmar

Geographically, Myanmar is situated in a strategic location in Southeast Asia with tropical climate and rich in natural resources including arable land, forests, minerals, natural gas, and freshwater and marine resources. The total land area of the country is the widest in Southeast Asia, with 676,577 square kilometers [34]. The country is populated with 53.7 million people [35], and 70% of them are living in a rural area working in the agricultural and forestry sectors [34]. The country has only recently opened up to the outside world after decades of isolation under military rule [36]. As a country with one of the lowest electrification rates in the Southeast Asian region, with only 44% of the population with access to electricity [13], the rural population is facing extreme energy poverty. Improving the electrification rate in the country would be a major opportunity for the government to improve the people’s quality of life, supporting economic growth, and improving healthcare and education facilities. In 2014, the government of Myanmar had introduced the National Electrification Plan (NEP) [37]. Based on its energy roadmap: the national electricity master plan (NEMP), Myanmar aims to electrify 100% of households in the country by 2030. To achieve this goal, Myanmar would have to electrify about 47% of households by 2020 and 76% by 2025 [38]. However, looking at the recent trends of electrification achievement, it is more likely that the target would be missed. The goal has been revised to 80% by 2030 [1].

Energy resource-wise, Myanmar has a relatively abundant resource of gas. However, the country has been exporting about 90% of it to China and Thailand [16,36]. The exporting contract agreement will only expire in 2030 [16]. Due to the larger population living in rural areas, renewable energy could play a significant role in achieving the country’s electrification goal. Myanmar has a rich hydropower potential from the four main basins (Ayeyarwaddy, Chindwin, Thanlwin, and Sittaung rivers) [39]. It is estimated that there is more than 100,000 MW of installed hydropower capacity potential [40]. Among these, there are 92 large hydropower potential projects with a total installed capacity of 46,000 MW, while the current installed capacity of large hydropower plants is 3298 MW [41]. Unlike the long experience with hydropower, there is still not enough available data to assess the suitable areas for wind turbine construction. It is, however, predicted that the western part of the country would have the best potential for harnessing wind power [42]. With more than 270 sunshine days per year, solar radiation is exceptionally good all over the country. The average solar irradiance is 4.5–5.1 kWh/m2/day with minimum fluctuations in the dry regions (Magway, Mandalay, and Sagaing) even during the rainy season [43]. In the biomass energy sector, Myanmar has a lot of potential from the agricultural sector. The country is the seventh largest rice producer in the world [44]; therefore, there is an abundant supply of rice plantation residues such as rice husk and rice straw. However, the readiness level of energy conversion technologies in this sector is still quite limited [45].

Despite these promising renewable energy potentials, in its present condition, grid extension has been taking time to develop, and for a decentralized energy system, many potential customers could not afford the high capital cost of high-quality renewable energy. Worsened by the limited short-term loan availability, some of the population have relied on lower quality, renewable energy technology using solar, hydro, and biomass energy as well as diesel generators through self-financing [36]. Thae Kone, the first case study village in this study, is one example where the population relies on pico-scale solar lanterns and panels for lighting. The village is located in Mandalay, the second-largest city in Myanmar on the east bank of the Irrawaddy River, central-northern part of the country.

3.2. Indonesia

Indonesia has the biggest resource of coal in the Southeast Asia region. There is approximately an annual production of 400 million tonnes of coal equivalent (Mtce) in the region, and a majority of it is from Kalimantan Island alone [1,16]. Despite this fact, the economic development and electrification of Kalimantan Island are lagging behind other major islands such as Java and Bali because most of the energy resources are being transported and used in and around the capital city, Jakarta. With the president’s plan of moving the capital from Java Island to Kalimantan Island by 2024, this unfortunate situation is expected to improve [46]. While Indonesia exports its gas and coal to many other countries from its abundant resources, the country is already importing crude oil because of the lack of newly discovered production wells and to suffice the increasing domestic demand, especially from the transportation sector [16,47]. While most of the population of the country (98.5%) already have access to electricity [48], Indonesia has the opportunities to improve their transmission and distribution efficiency and the reliability of the electricity supply as some regions and sectors still experience occasional blackout [15]. The country is also aiming to improve its share of renewable energy in its energy mix from 9% (2018) to 23% in 2025 and 29% in 2050 [47]. The largest renewable energy potential in Indonesia is from solar energy with 207.8 GWp, followed by hydro energy 94.3 GW, wind energy 60.6 GW, geothermal 28.5 GW, and ocean energy 17.9 GW. From the bioenergy sector, there is 32.6 GW Bio Polypropelene (Bio PP) potential and 200,000 barrel per day of biofuel potential [47]. While the country has high ambitions of biofuel production and commercialization, the results are still limited to certain sectors and areas due to lack of support from the local governments [49].

Kalimantan is geographically located near to the equator; this makes the climate quite warm all year long. The southern part of Kalimantan, where our second case study Karya Jadi village is located, is known as the second-largest coal producer in the island (second to east Kalimantan). However, the electricity generation in this part of the island is characterized by the relatively higher energy generation cost compared to the rest of the country with 1682 IDR/kWh or 0.12 USD/kWh while the national average is 0.078 USD/kWh (March 2020 conversion rate) [50]. While resourcing to affordable wind power has been argued to be able to improve electricity affordability, the fact that the area is a large coal producer has demotivated the development of renewable energy infrastructures [50].

3.3. Laos

Laos is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia, surrounded by Myanmar, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand. The country has provided access to electricity to 94% of its 6.95 million people, which is among the smallest population in the Southeast Asia region, leaving 1 million people having no access to electricity [51]. The opening of the Hongsa coal-fired power plant in 2015 in the country has improved the country’s dependency on coal imports. However, all of the generated electricity from this plant is exclusively for export to Thailand. On the other hand, Laos’ petroleum supplies such as gasoline, diesel oils, and jet fuels are imported from the neighboring countries, including Thailand [52]. Unlike many of its neighboring countries that rely primarily on fossil fuels, hydropower is the major source of electricity production in Laos. While 70% of the country is covered with mountains, it is also blessed with rivers. Therefore, dams were built to support their hydropower supply both for domestic and export use. Moreover, the traditional use of biomass is still the main source of heating and cooking energy for households in the country. Laos is expected to face significant energy demand growth and increase of CO2 emissions in the coming years [52]. To overcome these expectations, the country is targeting to further increase renewable energy share in the energy mix to 30% by 2025.

4. The Respondents’ Energy Related Basic Needs and Social Activities

4.1. Lighting

Historically worldwide, people living without electricity access meet their lighting needs by using candles and kerosene lanterns [53]. These types of lighting could only provide dim lights and entail a number of issues, especially in the health sector, from indoor emission from direct burning. Tuberculosis, asthma, cancer, and lung impairment are among the diseases associated with soot emission from kerosene usage [54,55,56]. Moreover, the emitted black carbon and carbon dioxide put a negative impact to the climate [57,58]. More recent investigations have found that people in the unelectrified villages have been transiting to other means of lighting such as the light-emitting diodes (LED) lamps [53] powered by low power photovoltaics (PV) [59] or the adoption of multiple energy sources [60] and solar home lighting systems (SHLS) [61]. The shift has taken place around the world with or without any governmental or non-governmental assistance [53]. While the system is still imperfect with problems of the technology lifetime and energy storage (Pandyaswargo, Abe, and Hong, 2014), there has been an improvement in the health [62] and climate sectors [59].

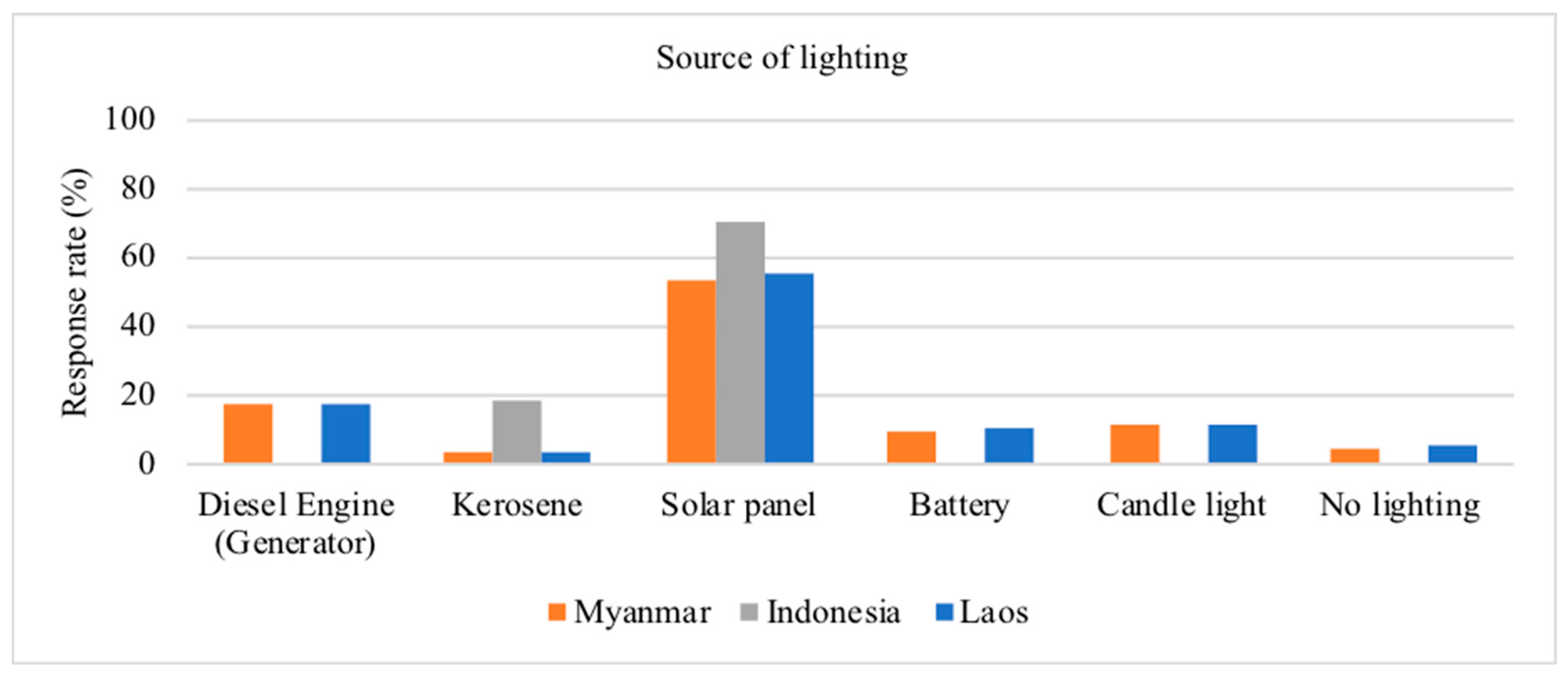

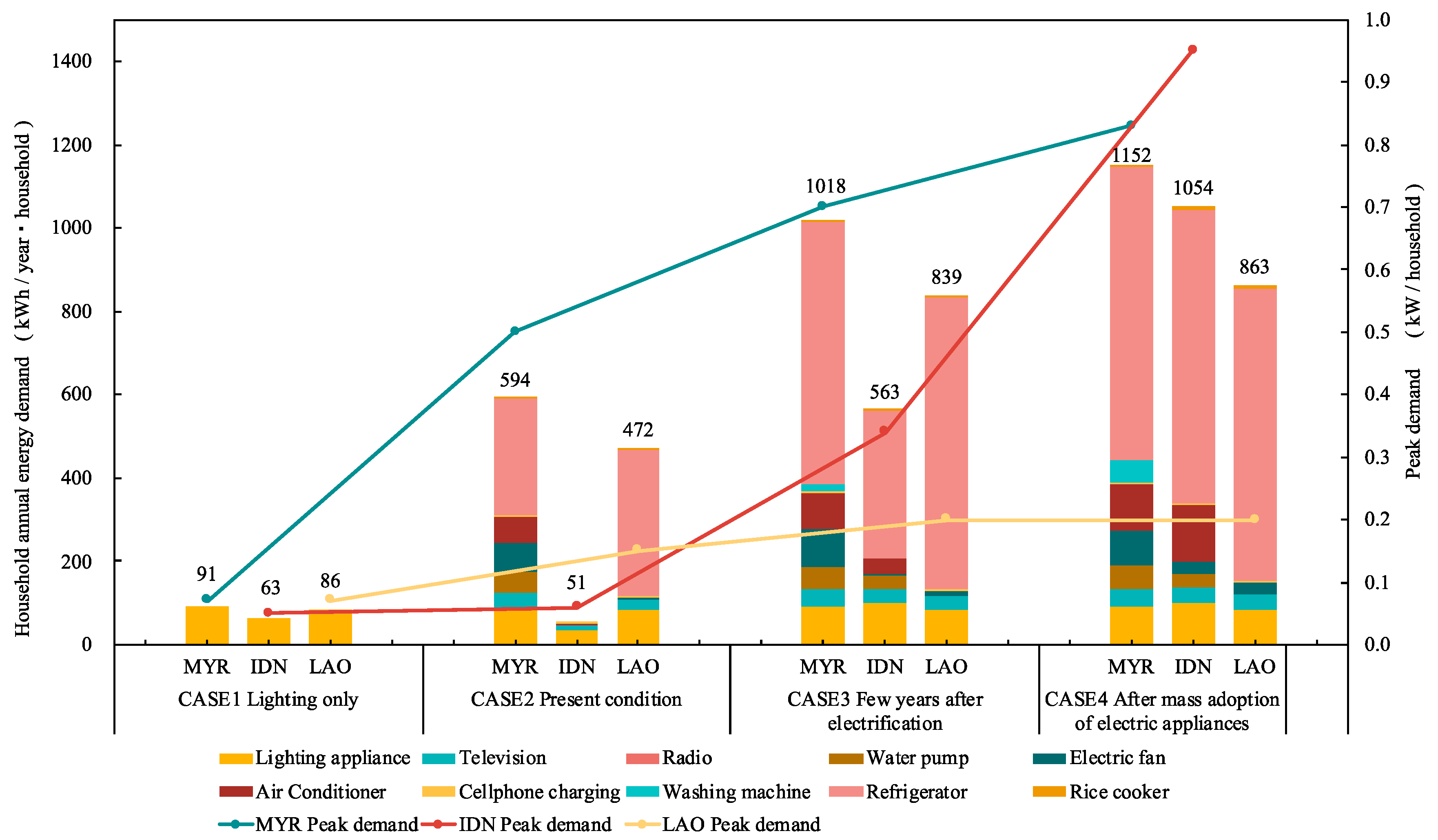

In the three case study villages of this study, low power PV is the most commonly used energy source for lighting (Figure 1). The types of PV and the way they are used varies slightly. In the Myanmar case study village, pico-solar or solar lanterns are the most commonly used type of PV. Each household may own several units of solar lanterns. Each of them has an attached LED lamp that will provide illumination throughout the night after being charged outside throughout the day under the sun. In the Indonesian case study village, each household owns a unit of 80-Watt peak (Wp), which was distributed by the Indonesian government in the year 2014. The batteries that came with the distributed PV have deteriorated about 2 to 3 years after their first use. Respondents reported that one PV is able to light about four lightbulbs in the house; however, they were unable to enjoy the light after dark in the last few years because the batteries have fully deteriorated. Some people have shifted back to kerosene lamps to overcome this situation even though the price of kerosene is relatively high after the government lifted its subsidy in 2016. In the Laos case study, about half of the respondents own a self-purchased solar panel with a 20 cm × 20 cm dimension for lighting purposes. Other than PV, the use of a diesel engine is also used in the Myanmar and Laos case study. The diesel fuel is purchased from the city and used not only for lighting but also to power other electric appliances such as television.

Figure 1.

Sources of electricity in the three case study villages.

4.2. Water for Drinking, Washing, and Bathing

Good accessibility of clean water lays the foundation of economic growth not only because it improves participation of women in education due to the shift of time allocation [63,64,65,66] but also because it improves human health [66,67]. In many parts of the world where electricity is not yet accessible, people collect water by a combination of sources and means to meet their water needs depending on the water availability on various seasons [68,69]. While harvesting rainwater and storage is one of the most affordable options that require minimum maintenance, there are risks of waterborne diseases and unreliability due to the rainfall fluctuation [69]. The introduction of renewable energy such as PV to provide energy for pumping water or water purification has seen a certain level of success [66,70] with a higher rate of sustainability when the project is done in multiple energy systems [71] and done in a participatory style [72].

People living in the three case study villages of this study have not utilized renewable energy to improve their access to water. The people living in the Myanmar case village took advantage of their closer proximity to the city by buying bottled water for their drinking water needs. Respondents reported that in the past, they had consumed collected rainwater, as well as water from the wells and rivers. However, over time people found themselves getting sick from consuming them, and water is unavailable during the dry season; therefore, people shifted to bottled water usually sold in 1-gallon size. The water gallons can be purchased from the local small grocery shop or from the distributors carrying the gallons in a cart pulled with a motorbike. In the Indonesian case, drinking water is obtained from pumping underground water from 120 m below the ground using a hand-handled pump. A pump was installed by the government on several households in the village back in 2008. The pumped water looks clear, but sedimentation of sand and soil can be seen after letting it sit for several hours. For drinking purposes, the water is boiled and cooled down to room temperature before consumption. In the Laos case study, drinking water is obtained from a rainwater catchment located on a higher elevation of the area, distributed by gravity through pipes to households in the village. Bottled water is not commonly consumed by the people except for those who are already in a sick condition.

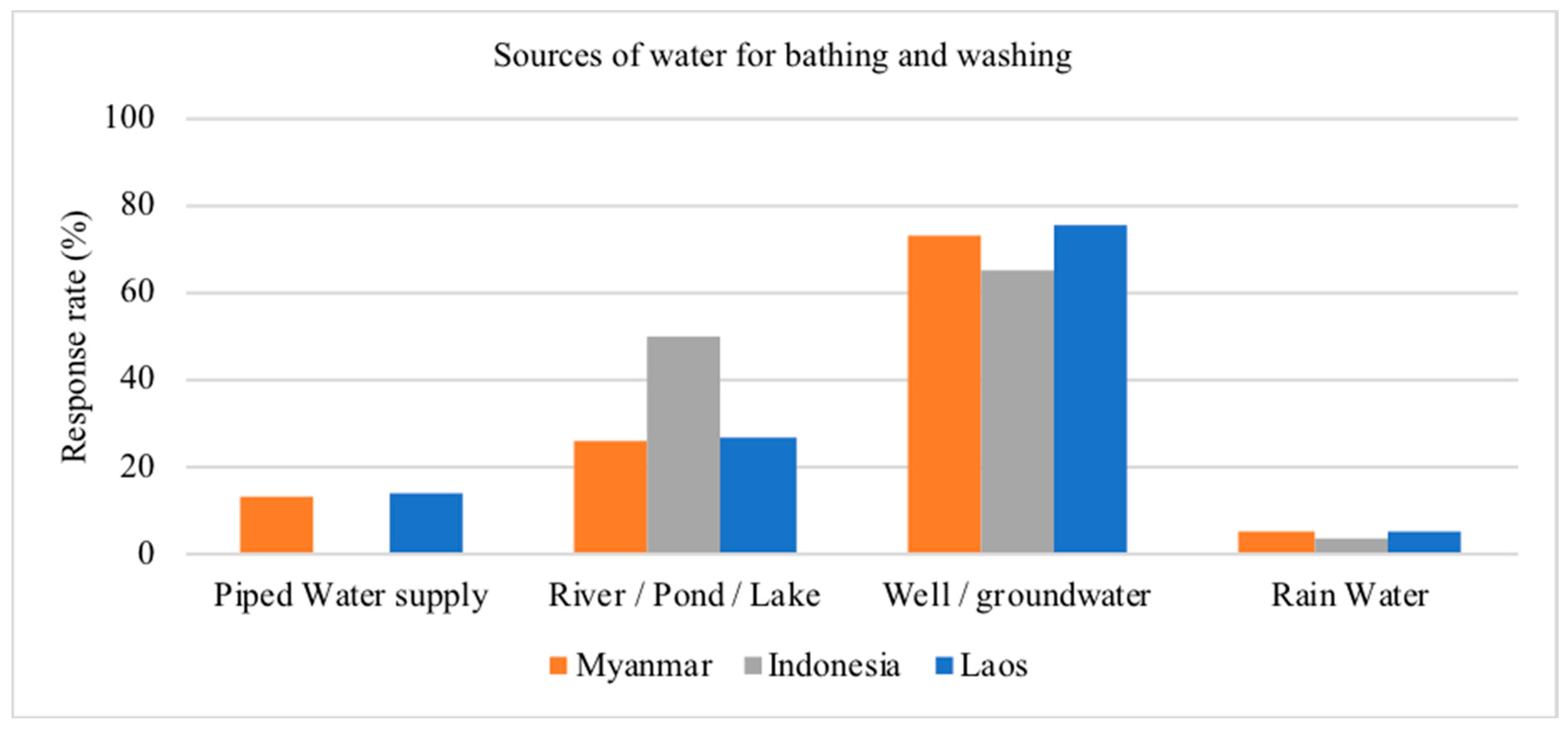

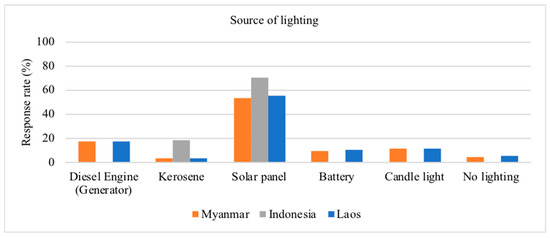

For bathing and washing purpose, the largest population of the respondents use water from the well or the pumped groundwater (Figure 2). During the rainy seasons, and for those who do not own a pump in Indonesia, people collect water from the nearby river. The Laos respondents would go to a common bathing facility where drinkable clear water is also supplied from.

Figure 2.

Sources of water for bathing and washing in the three case study villages

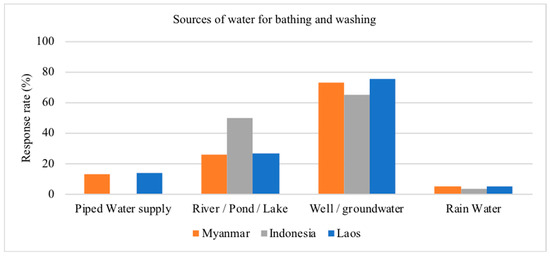

4.3. Food Storage and Cooking

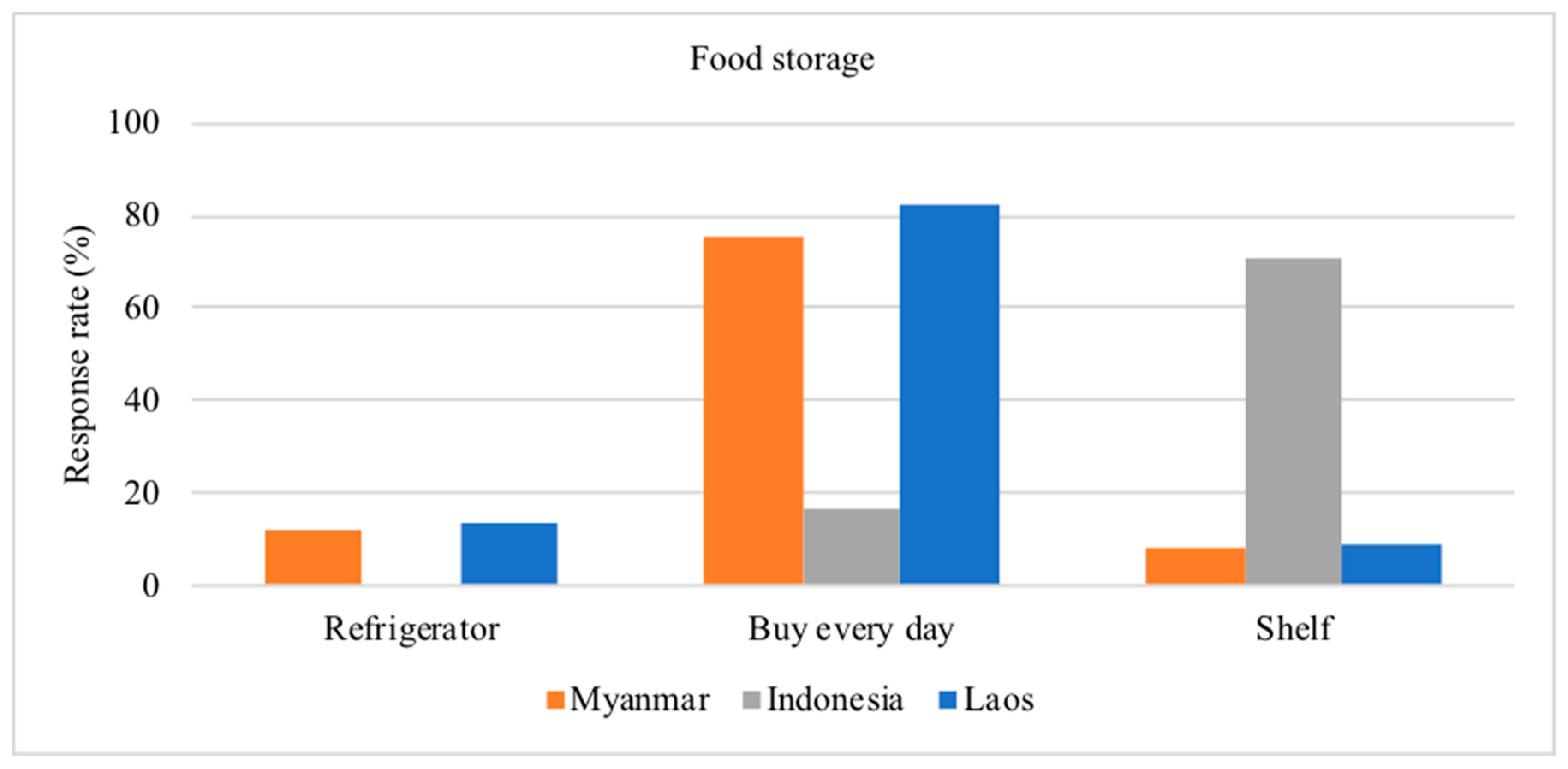

As the majority of livelihood in rural places without electricity is usually coming from the agricultural sector, food storage becomes essential. There are challenges that people in this area need to cope with a proper way of storing food, to name a few; uncertainties from limited means of knowing the weather forecast, a time gap between harvest seasons, the threat of pests infestation and humidity, and price drops when selling harvest during the productive time of the year (might encourage farmers to store it until prices climb up) [73]. Without electrification and with lower income, refrigeration becomes a hard option. In our three case studies, the means of storing food for household consumption was inquired. While the Myanmar and Laos case study showed a significantly high answer of buying the food every day from the local sellers, the Indonesian respondent mainly answers simple storage on the shelf (especially rice) without any additional way to preserve their food (Figure 3). The significant difference between the Indonesian case study with the other two is because the Indonesian respondents reported that they receive 8 kg of rice/household/month from the government. The Indonesian government has introduced the distribution of rice to the poorest population of the country since 2003 (formerly known as beras miskin (RASKIN) or “rice for the poor,” and later known as beras sejahtera (RASTRA) or “rice for prosperity”).

Figure 3.

Ways of food storage in the three case study villages.

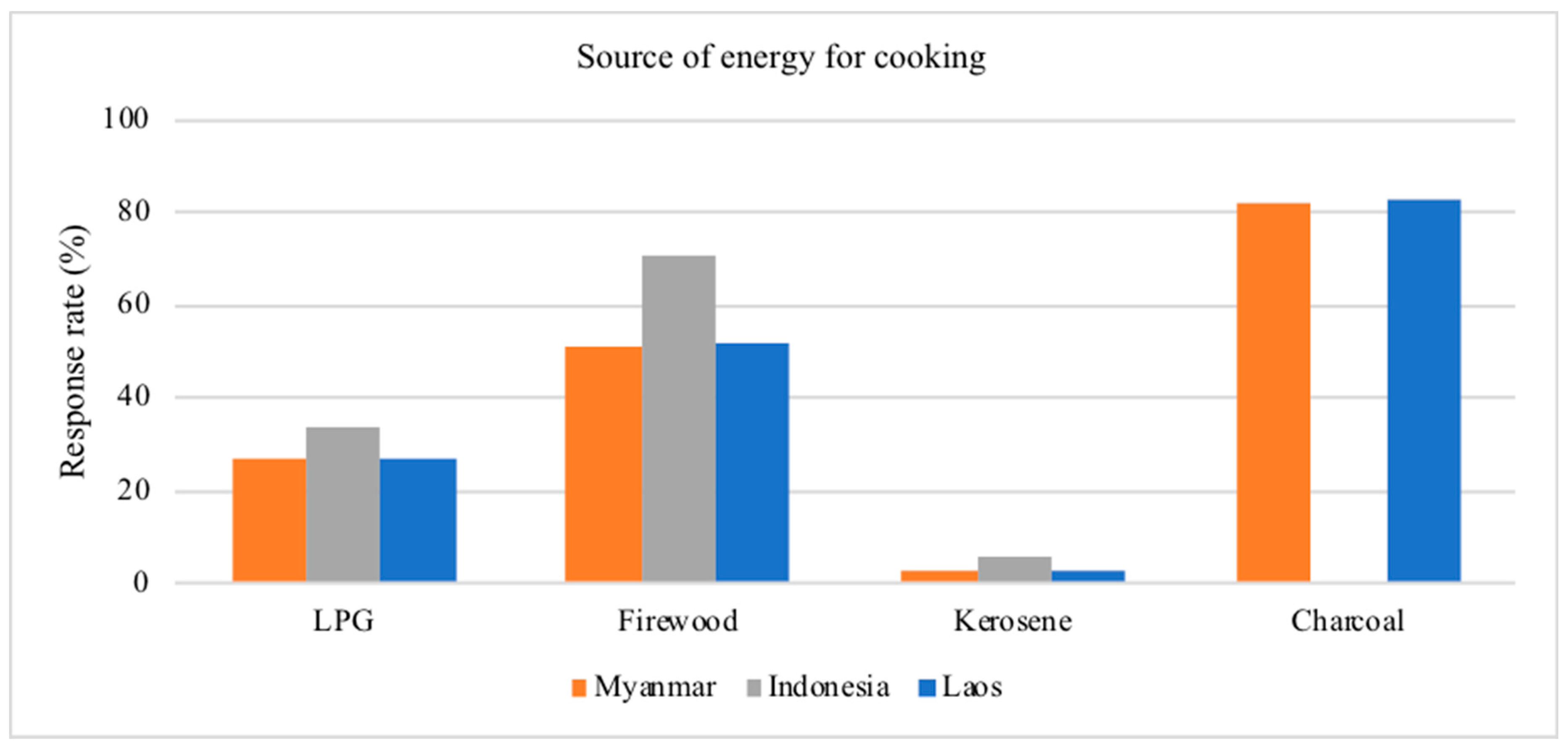

Cooking fuel is known to be a type of energy that is most stubborn to change in the off-grid villages. Despite the considerable amount of time required to collect biomass for cooking fuel [74] typically by women [75] and the high mortality rate associated with indoor air pollution from solid cooking fuels [76,77], many households in the rural area still choose to use it as their main source of cooking [78]. The most popular identified reasons are known to be the cost competition with the practically free biomass to collect from the surrounding area, low education and, limited knowledge about the risks of the traditional use of biomass [75,79].

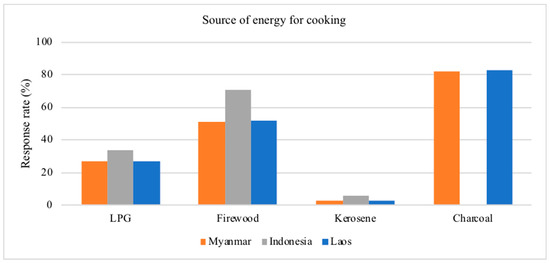

The results from our three case studies also show that firewood and charcoal are the most popular source of energy for cooking (Figure 4). While the firewood mostly can be collected from the respondents’ house vicinity for free, it is also sold in the local shops along with charcoals. The result also shows the limited use of liquified petroleum gas (LPG) in all of the three countries. In 2007, the Indonesian government introduced a household fuel conversion program for cooking from kerosene to LPG [80,81]. While the program was reported to last for five years, at the time of our field survey in 2019, the respondents reported that they still receive two filled 3 kg LPG tanks on a monthly basis provided for free by the government.

Figure 4.

Source of cooking fuel in the three case study villages.

5. Estimation of Electricity Demand

5.1. Data from the Questionnaire as Estimation Parameters

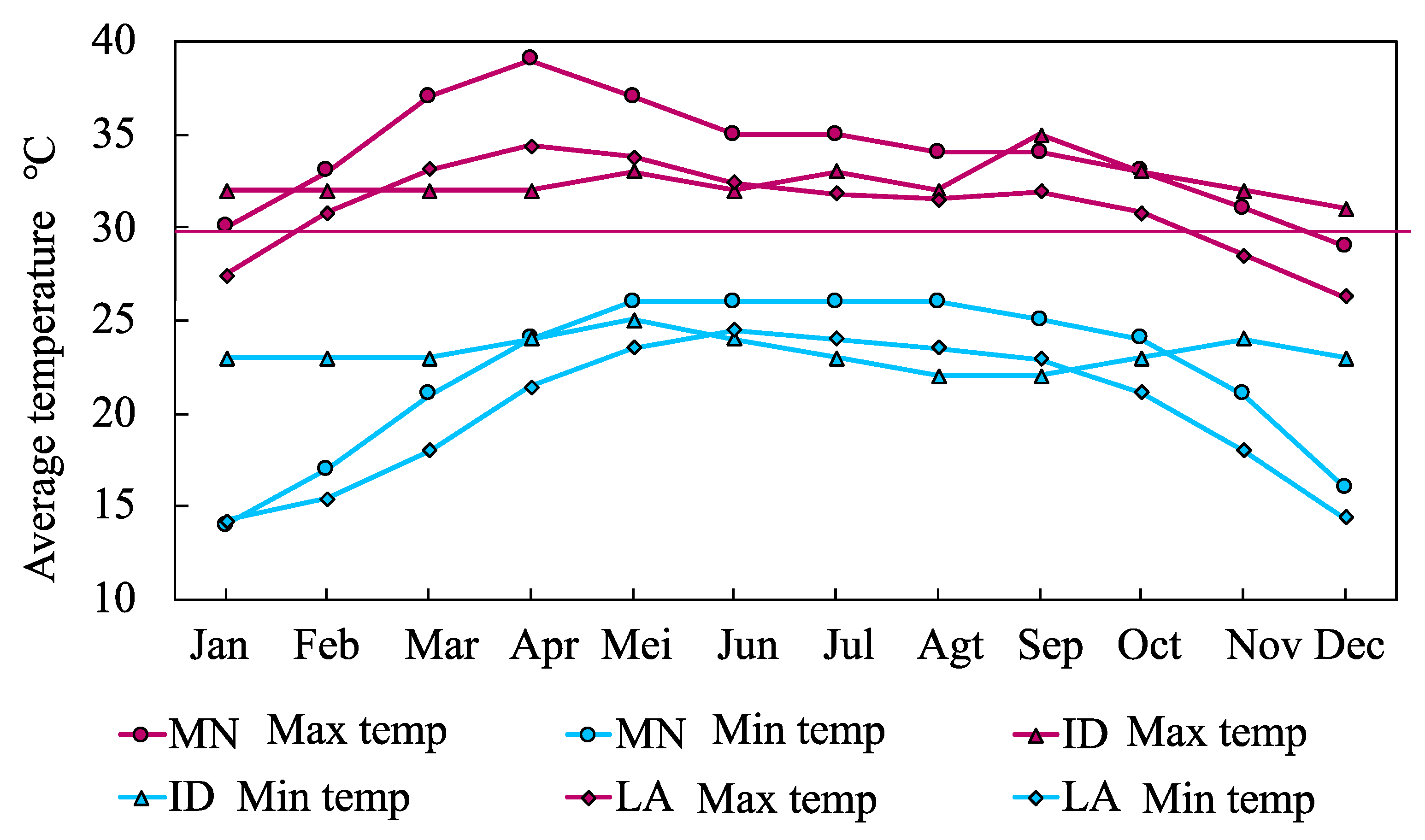

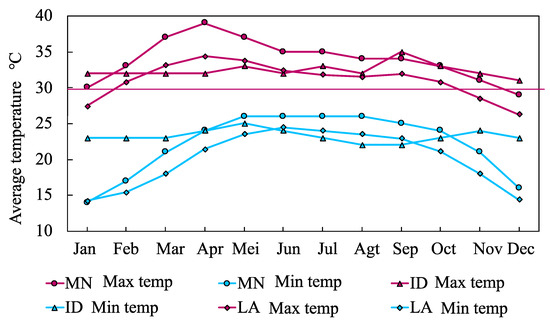

About 10% of the total respondents in each village were interviewed in the local language to answer the time-use questionnaire. From the questionnaire, information such as the order and duration of the daily activities, place, and whether a number of electrical appliances are used simultaneously could be identified. We used those data and information from the interview with key stakeholders in each village (summarized in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5) as well as assumptions from secondary data (such as the yearly temperature presented in Figure 5) to estimate the energy demand in each village.

Table 3.

Main time and duration of energy related activities in each case study village from the time-use questionnaire.

Table 4.

Rate of appliance ownership in each case study village from the survey questionnaire.

Table 5.

Other parameters used to estimate the energy demand in each case study village from key stakeholder interview and secondary data.

Figure 5.

Monthly average temperature in each case study village, constructed from Merra-2 data [82]. MN: Myanmar; ID: Indonesia; LA: Laos.

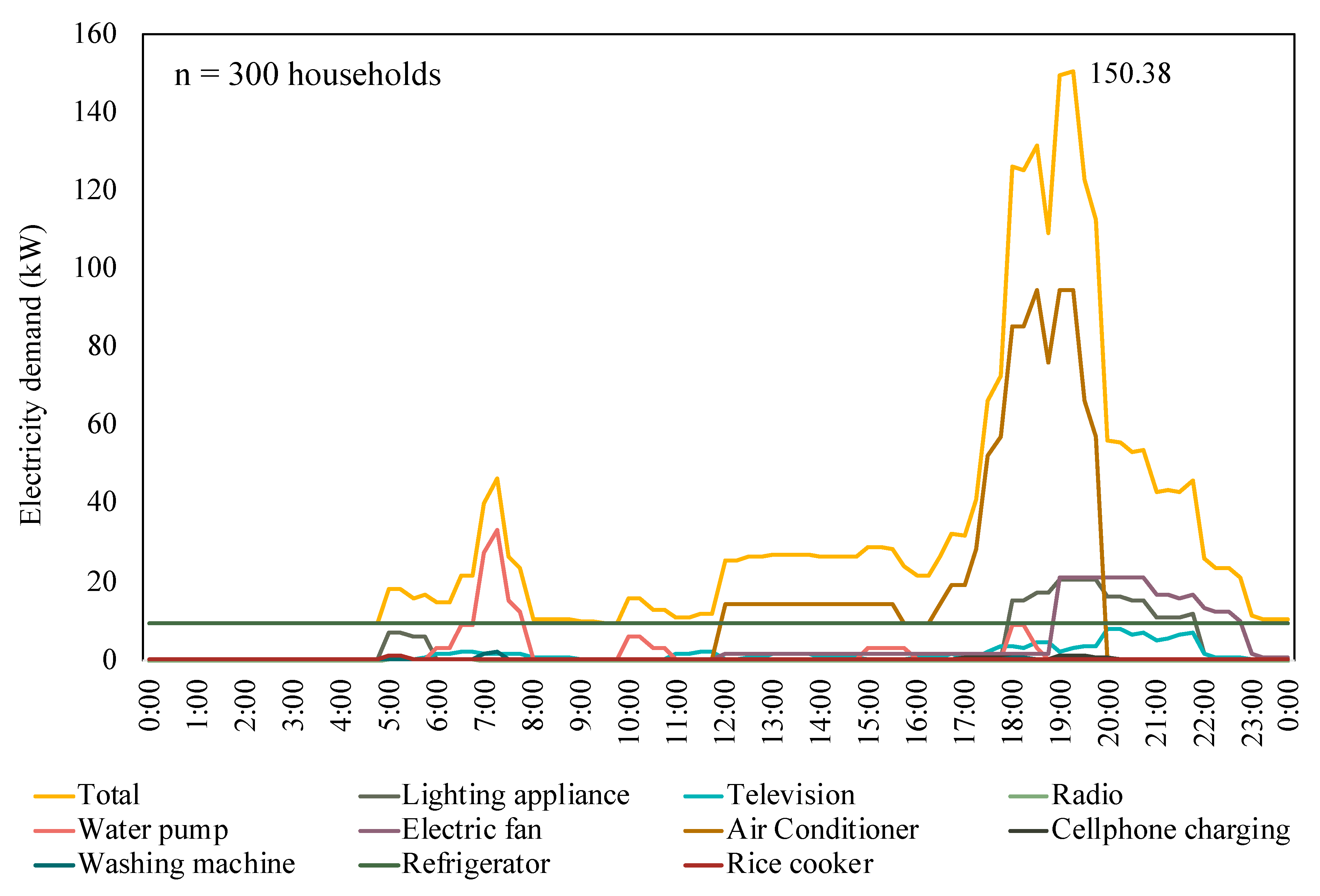

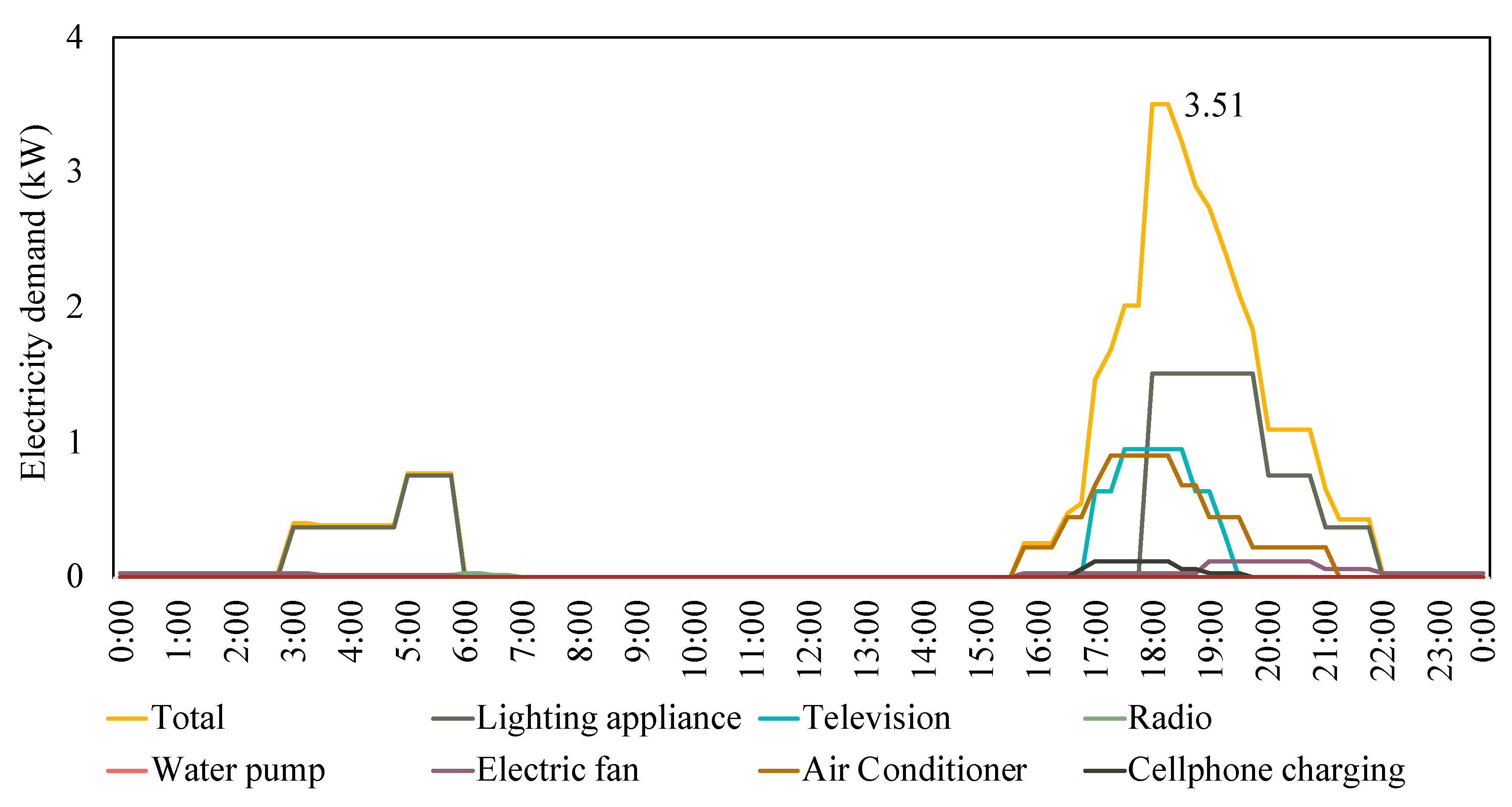

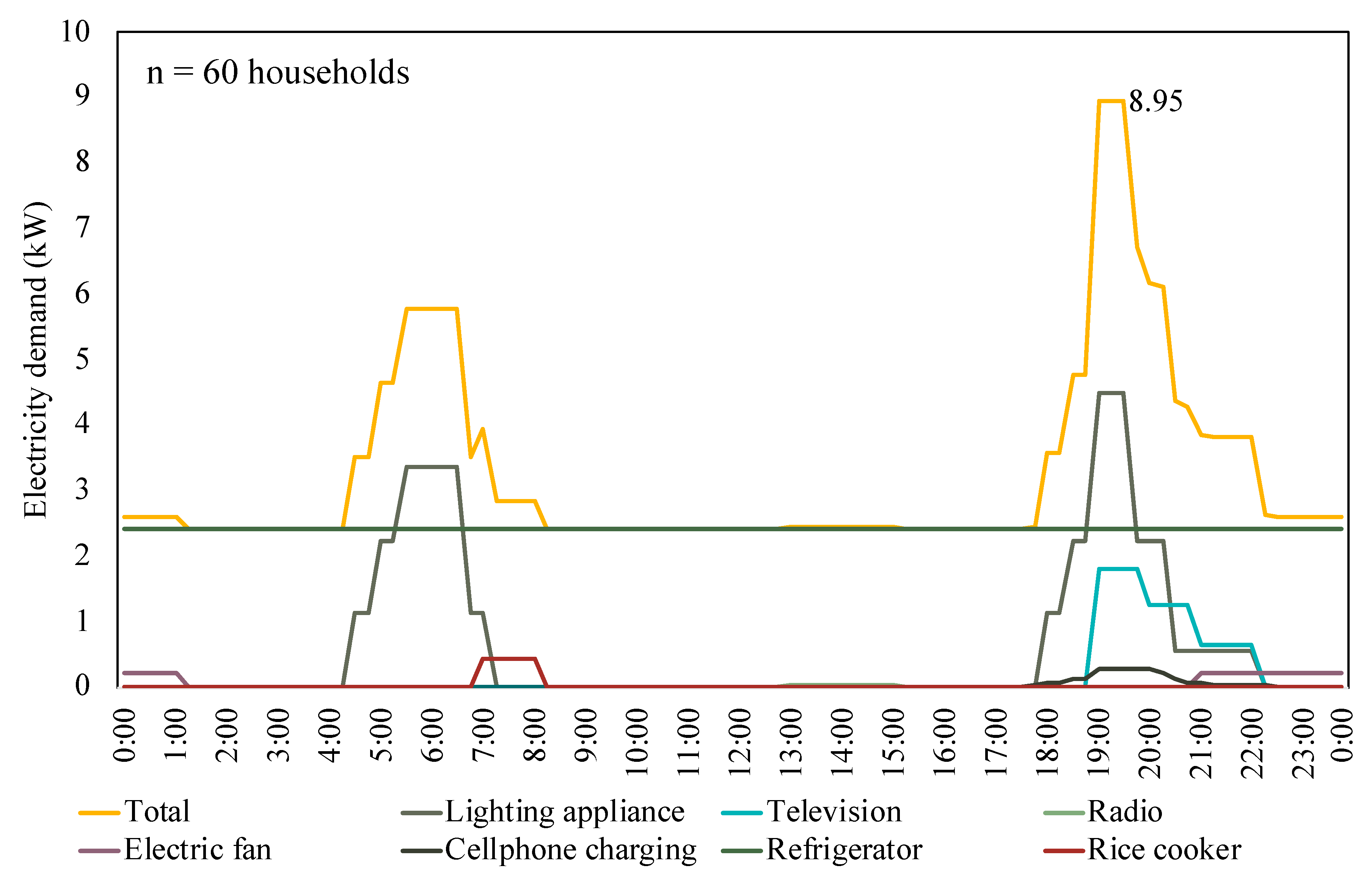

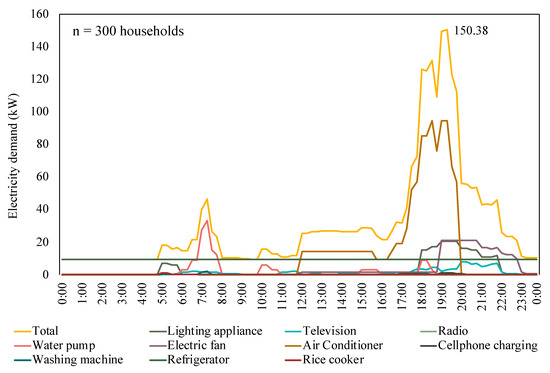

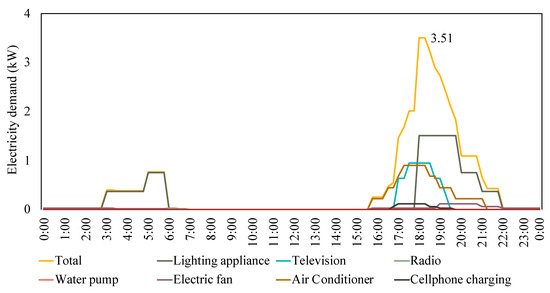

5.2. Energy Demand and Load Pattern

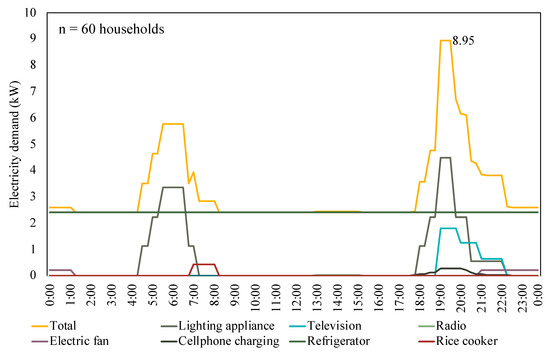

The collected data was used to estimate the load pattern of electricity demand using the “end-use model” presented earlier in the methodology section. Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the load pattern of each case study. In all of the case studies, it can be observed that there is an increase in demand in the morning and the evening time with a higher peak in the evening. The evening peaks are mainly caused by lighting for the dinner time and studying as the night gets dark, cellphone charging after full day use, an electric fan for more comfortable sleeping during the warm night. Due to easier access to get diesel fuel in the Myanmar case study, there is a higher use of air conditioners and electric fans in the warmest seasons. The first increase of demands in the morning is mainly caused by taking a shower, cooking, and washing clothes before the respondents leave for work and for the laundry to be hung under the day sun heat and light for drying. A significant difference can be seen in the Indonesian case study where the need for lighting in the morning started as early as 3 a.m. This is because of the predominantly Muslim population in the village where they have a morning prayer to be done before the sun rises. In the Laos case study, the significant increase in demand in the morning is caused by the use of rice cookers, which is owned by 40% of the respondents. It turned out, some of the households, especially those living in the HK village, have some access to electricity from the grid since 2014. This has allowed them to run higher wattage appliances such as the rice cooker and appliances requiring stable electricity supply such as the refrigerator.

Figure 6.

Current electricity demand daily load pattern of the Myanmar case study (during the warm season).

Figure 7.

Current electricity demand daily load pattern of the Indonesian case study (during the warm season).

Figure 8.

Current electricity demand daily load pattern of the Laos case study (during the warm season).

6. Projection of Energy Demand Future Growth

6.1. Constructed Scenarios

To construct several demand growth projection scenarios, we considered several factors in the three villages. At first, we looked at the yearly temperature (Figure 5), where especially in Myanmar and Indonesia cases, the dry seasons can get quite warm. While this may imply the need for air conditioner, electric fan, and refrigerator for cooling and food preservation, the current rates of the electric appliance (Table 2) do not show this trend. This may have been caused by the high wattage and electricity supply stability requirement of air conditioners and the fact that many of the respondents are working in the forestry and agricultural sector where food can be obtained fresh on a daily basis. While respondents expressed that lighting is one of the most urgent needs of electrical appliance, the pico-solar, and solar panels have been able to provide the required small amount of electricity to light the lamps. Other evidence (Table 2) that we observed shows that cellphone and television have relatively high adoption rates. It is predicted that it is because these two appliances have low energy consumption and crucial for communication and entertainment in remote villages where other forms of entertainment are quite rare. Based on these observations, we have constructed four different scenarios (CASE1 to 4). These scenarios are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Constructed scenarios for energy demand growth projections.

6.2. Projection Results

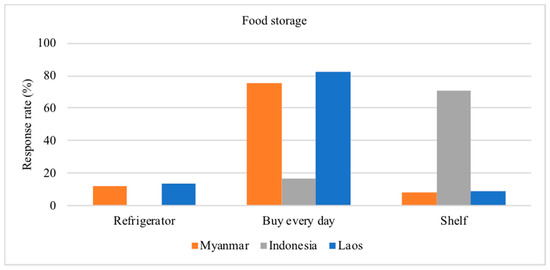

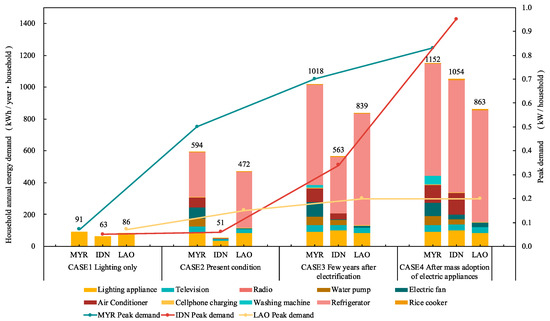

Based on the constructed scenarios elaborated in Table 6, the household annual energy demand and the peak demand in each case study villages are projected (Figure 9). In the CASE1 scenario, the demand difference between case studies is significantly influenced by the size of the household, with the Indonesian case as the smallest one. In the CASE2 scenario, the Myanmar case study village has the most diverse types of electricity appliances already in possession by the respondents, with the refrigerator as the most energy-consuming appliance. In the CASE3 scenario, the gaps between case studies become closer as more appliances are adopted in each village, with the exception of Laos where water pump and air conditioner are unnecessary due to the topography and climate of the village. Finally, in the CASE4 scenario, it is predicted that the energy demand of the Indonesian village will surpass the Laos village mainly due to the increase of demand from air conditioners, especially because of the significant difference of all-year temperature between the two villages. The variation of peak demands throughout the scenarios is mainly influenced by how many electricity-supported activities are conducted at a time during the day, and the wattage the supporting appliances used at those times.

Figure 9.

Projection of household annual energy demand and peak demand in each case scenarios and case study villages. MYR: Myanmar; IDN: Indonesia; LAO: Laos.

7. Discussions and Conclusions

7.1. Findings

This study had analyzed the findings of case-based off-grid villages surveys in Myanmar, Indonesia, and Laos to identify the current energy demand and project the future energy demand based on several constructed scenarios. It was found that the factors of household size, proximity to the city, climate, and topography may influence the present and future growth of energy demands in the villages. Some specific findings are as follows:

- The solar panel is among the earliest adopted renewable energy for lighting in rural households.

- Lighting appliance, television, and cellphones are the earliest adopted electric appliances in the case studies.

- The possession of food preservation appliance such as the refrigerator is less prioritized as food can be obtained on a daily basis from the vicinity.

- The village location that was closer and with better access to the city created a more diverse job for the residents resulting in a more diverse activities and time variation of the use of energy at home.

- In the colder climate village, there is less need of air conditioning.

- In the steep topography or the mountainous case study village, there is less need of energy for pumping because water can be distributed by gravity.

- Peak energy demand could be found early in the morning and late in the afternoon.

Although the results are case-specific, compared to other energy demand projection studies, our results are quite similar to the other publications by major international development banks and national governments. For example, the Myanmar CASE4 projection result in this study is close to the Mandalay average energy demand at 1294 kWh in the Myanmar energy consumption survey by Asian Development Bank (ADB) [83], Indonesia CASE4 projection result is close to the 2030 projection at around 950 kWh presented in [84] by the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) [85]. The Laos CASE4 is, however, below the average baseline consumption of 705 kWh/month/household shown in the Lao PDR Energy Statistics 2018 [86]. This is presumably due to the gravity-based water distribution as well as the mild temperature all-year-long that makes room air conditioning unnecessary. The growth of these energy demand may depend on several things including how drastically access to the city improves, whether electricity line from the main grid would finally extends to the village, whether the climate would change significantly, and other factors. Based on our four constructed scenarios, the demand would increase significantly in either case especially with the assumption that there might be need for faster communication following globalization and higher global temperature due to the global warming, leading to the need of room cooling and food refrigeration.

7.2. Limitations and Challenges

There were several limitations and challenges faced while conducting this study. Notably, the remoteness of the villages made multiple trips to the location quite costly and challenging. Hence, the surveys were only taken once in each village. Secondly, a time-use questionnaire is ideally taken for both the weekday and the weekend, and in several days, and best to be filled by the respondents themselves. However, due to the area’s remoteness, our limited resources, and low literacy level of some of the respondents, filling the questionnaires was supported by facilitators and only done once. Another limitation was the sample size of the study. It was challenging to gain a 100% response level against the population especially for the Myanmar case study because some of the residents are employed in places where they cannot leave the workplace during the time of the survey. Gathering the Indonesian and Laos case village residents were more doable due to the more flexible nature of farmers’ work, which is the typical job of the respondents. This situation has caused an imbalance of sample proportion against the population of the case study villages. A challenge that we felt have successfully overcame was the language barrier. A local language was spoken by each of the respondents in the case study village that differs from the national language. A native facilitator has supported the survey to avoid any misunderstandings. Something that was asked by the participants in all of the case study villages is whether the survey would be followed-up by an actual electrification project and whether it has anything to do with the government. This is something that other scholars who plan to conduct similar studies have to be prepared to answer.

7.3. Future Perspectives and Venues for Further Studies

While village electrification is the responsibility of the government, the relatively smaller population size of unelectrified village can be an interesting ground for the private sector to build smart community pilot projects that often take place in a costly manner in the developed world such as the Smart town in Japan and the Statdwerke in Germany. The absence of a grid extension is an opportunity to optimize renewable energy. While the relatively lower income of the residence is a challenge in itself to provide energy affordably, it is a chance to showcase the true benefit of utilizing the renewable energy resources from the local environment. Furthermore, there is assistance from the government for smaller capacity renewable energy in the form of Feed-in-Tariffs. Agricultural residues from the plantation area that is of the industrial nature of an electrified village is also a good area to explore waste-to-energy recovery. For example, the Indonesian case study village is surrounded by palm plantation and the palm oil mills generating a significant amount of biomass waste that can be used to electrify the village. In the Myanmar case study, the river and rice plantation nearby may have potential for hydro and biomass energy generation. In the Laos case study, geothermal, hydro, and woody biomass may have potential to provide electrification in the villages.

There are venues for further study. Firstly, the Indonesian case in this study has shown an extensive government intervention in the basic needs and energy sector, such as LPG for cooking, solar panel for lighting, and hand handled water pump for clean water supply. Whether or not such intervention effectively accelerated the transition to modern energy and how to sustain the government-distributed technologies that are appropriate to the capacity of the people, requires further studies.

Secondly, the energy demand projection results and analysis in this study have, to some extent, filled the gap of the neglection of demand projections often found in other off-grid energy demand estimation studies [33]. Our findings have provided some bases for estimating the size of a centralized, off-grid village energy system in a similar area. The most concrete next stage following-up this study would be to create a pilot project of an energy system in the area. Some additional steps that may benefit such pilot project creation would be to develop a detailed inventory of the renewable energy potential and design the appropriate mix of those potentials to respond to the expected peak demand and the fluctuation of energy demand that has been presented in this study.

Lastly, it can be predicted that the social activities in unelectrified villages may change with the introduction of modern energy due to time saved from using electric appliances. A thorough study on such changes may help in creating a dynamic energy system and pricing to provide better sustainability of the system for the long term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.P. and H.O.; methodology, A.H.P., M.R., and H.O.; software, A.H.P., M.R., and A.D.W.; validation, A.H.P., M.R., and H.O.; formal analysis, A.H.P., M.R., A.D.W., and H.O.; investigation, A.H.P., M.R., E.H., M.H., and A.D.W.; resources, A.H.P., M.R., E.H., M.H., Y.N., and A.D.W.; data curation, A.H.P., M.R., M.H., and A.D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.P. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, A.H.P.; visualization, A.H.P., M.R., and A.D.W.; supervision, A.H.P., M.H., Y.N., and H.O.; project administration, A.H.P. and Y.N.; funding acquisition, A.H.P., E.H., M.H., Y.N., and H.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Japan Science and Technology (JST) Agency, Strategic International Collaborative Research Program (JST SICORP), under the e-Asia Feasibility Study on Social Implementation of Bioenergy in East Asia and by Waseda University Grants for Special Research Projects (Tokutei Kadai). APC is paid by the authors’ token from the voluntary review activities on MDPI and by Waseda University.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the local government, head of villages, and village managers who assisted in inviting the respondents in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IEA. Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2019; IEA: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PWC-APLSI. Alternating Currents: Indonesian Power Industry Survey 2018; PWC-APLSI: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naimoly, S.; Nakano, J. The Role of Renewables in Achieving Universal Access to Electricity in Southeast Asia; Center for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar, M.; Pesaran, M.; Mohammadi-ivatloo, B. Transactive energy integration in future smart rural network electrification. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 190, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Mumata, M.; Mogi, G. Economic Comparison of Microgrid Systems for Rural Electrification in Myanmar. Energy Procedia 2019, 159, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, F.C.; Gopalan, S. Low cost, highly reliable rural electrification through a combination of grid extension and local renewable energy generation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.K.; Sarkar, S. Modeling of hybrid energy system for futuristic energy demand of an Indian rural area and their optimal and sensitivity analysis. Renew. Energy 2018, 118, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberilla, J.M.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental sustainability of small-scale biomass power technologies for agricultural communities in developing countries. Renew. Energy 2019, 141, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, J.; Urpelainen, J. Electrification and appliance ownership over time: Evidence from rural India. Energy Policy 2019, 133, 110862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.W.; Abe, N.; Baclay, M.; Arciaga, L. Assessing users’ performance to sustain off-grid renewable energy systems: The capacity and willingness approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2015, 28, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torero, M. The Impact of Rural Electrification: Challenges and Ways Forward. Rev. Econ. Dev. 2015, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagawa, M.; Nakata, T. Assessment of access to electricity and the socio-economic impacts in rural areas of developing countries. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 2016–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEDS. ASEAN Energy Database System (AEDS). 2019. Available online: https://aeds.aseanenergy.org/country/brunei-darussalam/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Kunaifi, K.; Veldhuis, A.J.; Reinders, A.H.M.E. Experiences of End-Users of the Electricity Grid. In SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Falentina, A.T.; Resosudarmo, B.P. The impact of blackouts on the performance of micro and small enterprises: Evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 2018, 124, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2017; IEA: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, J.; Sebestyén, T.T.; Bartók, B. Evaluation of renewable energy sources in peripheral areas and renewable energy-based rural development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrica, M.; Richter, M.; Thomas, S.; Graham, I.; Mazzara, B.M. Social approaches to energy transition cases in rural Italy, Indonesia and Australia: Iterative methodologies and participatory epistemologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, D.J.; Stolte, O.E.E. Case-based Research in Community and Social Psychology: Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 22, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T.; Ferri, F. Environmental sustainability and participatory approaches: The case of Italy. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarini, M.R.; Morano, P.; Sica, F. Integrated Ecosystem Design: An Evaluation Model to Support the Choice of Eco-Compatible Technological Solutions for Residential Building. Energies 2019, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Abe, N.; Hong, G.W.C. Participatory Workshop on Bottom-Up Study Contributing to the Realization of Sustainable Development Goals: Pangan-an Island Case Study; Technical Report of International Development Engineering; Tokyo Institute of Technology: Tokyo, Japan, May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, M.; Pandyaswargo, A.H.; Onoda, H.; Htwe, E. Development of energy demand forecasting method in non-electrified area of Myanmar. In Proceedings of the Society of Environmental Science, Nagoya, Japan, 13–14 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wiedmann, T.; Yao, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y. Urban-rural disparities of household energy requirements and influence factors in China: Classification tree models. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, K.; Eyers, D.; Ford, R.; Stephenson, J.; Anderson, B.; Jack, M. Detailed comparison of energy-related time-use diaries and monitored residential electricity demand. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. The dynamics of energy demand: Change, rhythm and synchronicity. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torriti, J. Understanding the timing of energy demand through time use data: Time of the day dependence of social practices. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.E. Rethinking gender and identity in energy studies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Tools and Methods for Integrated Resource Planning Improving Energy Efficiency and Protecting the Environment; UNEP Collaborating Centre on Energy and Environment: Roskilde, Denmark, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Govinda, S.C.B.; Timilsina, R. Energy Demand Models for Policy Formulation A Comparative Study of Energy Demand Models; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, K.B.; Mourshed, M.; Chew, S.P.K. Modelling and Forecasting Energy Demand in Rural Households of Bangladesh. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2731–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente, F.; Lundblad, A.; Campana, P.E.; Zhang, Y.; Cabrera, S.; Lindbergh, G. Photovoltaic/battery system sizing for rural electrification in Bolivia: Considering the suppressed demand effect. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADBI. ADBI Working Paper Series Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia Asian Development Bank Institute; ADBI: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Population, Total-Myanmar|Data. 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=MM (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- CSIS. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Department of Population, Ministry of Immigration and Population, The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census; CSIS: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy and Electricity (MOEE). 2020. Available online: https://www.moee.gov.mm/en/ignite/page/80 (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Castalia Strategic Advisor. Myanmar National Electrification Program (NEP) Roadmap and Investment Prospectus Final Road Map and Investment Prospectus; Castalia Strategic Advisor: Sidney, NSW, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saw, M.M.M.; Li, J.Q. Review on hydropower in Myanmar. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, K. The Role of Hydropower in Myanmar; Myanmar Government: Nay Pi Taw, Myanmar, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Baseline Assessment Report Hydropower Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Hydropower Sector in Myanmar; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ADB. Myanmar: Energy Sector Initial Assessment; ADB: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ADB. Developing Renewable Energy Mini-Grids in Myanmar a Guidebook; ADB: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Faostat-Countries by Commodity. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/countries_by_commodity (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Pandyaswargo, A.; Pang, D.; Ihara, I.; Onoda, H. Japan-Supported Biomass Energy Projects Technology Readiness and Distribution in the Emerging Southeast Asian Countries: Exercising the J-TRA Methodology and GIS. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nasional, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan. Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Nasional 2020–2024; Nasional, Kementerian Perencanaan Pembangunan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DEN. Indonesia Energy Outlook; DEN: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AEDS. Indonesia—ASEAN Energy Database System (AEDS). 2019. Available online: https://aeds.aseanenergy.org/country/indonesia/ (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Putrasari, Y.; Praptijanto, A.; Santoso, W.B.; Lim, O. Resources, policy, and research activities of biofuel in Indonesia: A review. Energy Rep. 2016, 2, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish Energy Agency. South Kalimantan Regional Energy Outlook 2019; Danish Energy Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AEDS. Lao PDR—ASEAN Energy Database System (AEDS). 2019. Available online: https://aeds.aseanenergy.org/country/lao-pdr/ (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Ministry of Energy and Mines. Lao PDR Energy Outlook 2020 Ministry of Energy and Mines Supported by ERIA; ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bensch, G.; Peters, J.; Sievert, M. The lighting transition in rural Africa—From kerosene to battery-powered LED and the emerging disposal problem. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 39, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Barnes, D.F. Energy Policies and Multitopic Household Surveys: Guidelines for Questionnaire Design in Living Standards Measurement Studies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, N.L.; Smith, K.R.; Gauthier, A.; Bates, M.N. Kerosene: A review of household uses and their hazards in low-and middle-income countries. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B Crit. Rev. 2012, 15, 396–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.B.; Bates, M.N.; Arora, N.K.; Balakrishnan, K.; Jack, D.W.; Smith, K.R. Household fuels, low birth weight, and neonatal death in India: The separate impacts of biomass, kerosene, and coal. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2013, 216, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Regional Report on Efficient Lighting in Sub-Saharan African Countries; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, N.L.; Chen, Y.; Weyant, C.; Venkataraman, C.; Sadavarte, P.; Johnson, M.A.; Smith, K.R.; Brem, B.T.; Arineitwe, J.; Ellis, J.E.; et al. Household light makes global heat: High black carbon emissions from kerosene wick lamps. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 13531–13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlinger, B.; Reinders, A.; Toxopeus, M. A comparative life cycle analysis of low power PV lighting products for rural areas in South East Asia. Renew. Energy 2012, 41, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, E.; Athavankar, A.; Hsu, D. Variation in rural household energy transitions for basic lighting in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, M.; Mahapatra, S.; Palit, D.; Chaudhury, M.K. Performance and impact evaluation of solar home lighting systems on the rural livelihood in Assam, India. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 38, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, G.Y.; Akuffo, F.O.; Braimah, I.; Evers, H.D.; Mensah, E. Impact of solar photovoltaic lighting on indoor air smoke in off-grid rural Ghana. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2008, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuwal, H.; Bohara, A.K. Biogas: A promising renewable technology and its impact on rural households in Nepal. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2668–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauges, C.; Strand, J. Water Hauling and Girls’ School Attendance: Some New Evidence from Ghana. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 66, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. A qualitative factor analysis of renewable energy and Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) in the Asia-Pacific. Energy Policy 2013, 59, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasrotia, S.; Kansal, A.; Kishore, V.V.N. Application of solar energy for water supply and sanitation in Arsenic affected rural areas: A study for Kaudikasa village, India. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; Marwa, D.; Stephen, M.; Joakim, Ö.; Anthony, T. Trans-Boundary Water Cooperation as a Tool for Conflict Prevention and for Broader Benefit; University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Dhital, R.P. Water for life: Ceaseless routine efforts for collecting drinking water in remote mountainous villages of Nepal. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahinda, J.M.M.; Taigbenu, A.E.; Boroto, J.R. Domestic rainwater harvesting to improve water supply in rural South Africa. Phys. Chem. Earth 2007, 32, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.S.; Ramos, H.M. Solar powered pumps to supply water for rural or isolated zones: A case study. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2009, 13, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Sharma, R. Feasibility study of hybrid energy system for off-grid rural water supply and sanitation system in Odisha, India. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2016, 37, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barde, J.A. What Determines Access to Piped Water in Rural Areas? Evidence from Small-Scale Supply Systems in Rural Brazil. World Dev. 2017, 95, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesseri, G.P.; Aikaeli, J. Stepping up Indigenous Knowledge and Technologies for Higher Incomes for Women in Rural Tanzania: A Case of Food Processing and Storage. Indegineous Knowl. 2016, 4, 95–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ljung, P. Energy Sector Reform: Strategies for Growth, Equity and Sustainability; Sida Studies Series: Stockholm, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rahut, D.B.; Ali, A.; Mottaleb, K.A.; Aryal, J.P. Wealth, education and cooking-fuel choices among rural households in Pakistan. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2019, 24, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO | Household Air Pollution. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/phe/indoor_air_pollution/en/ (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- WHO. WHO | Mortality from Household Air Pollution. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/phe/indoor_air_pollution/burden/en/ (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Makonese, T.; Ifegbesan, A.P.; Rampedi, I.T. Household cooking fuel use patterns and determinants across southern Africa: Evidence from the demographic and health survey data. Energy Environ. 2018, 29, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hou, B.; Ke, R.Y.; Du, Y.F.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, T.; Teng, M.; Liu, J.; et al. Residential Fuel Choice in Rural Areas: Field Research of Two Counties of North China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoday, K.; Benjamin, P.; Gan, M.; Puzzolo, E. The Mega Conversion Program from kerosene to LPG in Indonesia: Lessons learned and recommendations for future clean cooking energy expansion. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 46, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NBruce, G.; Aunan, K.; Rehfuess, E.A. Liquefied Petroleum Gas as a Clean Cooking Fuel for Developing Countries: Implications for Climate, Forests, and Affordability. Mater. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- NASA. MERRA-2. 2016. Available online: https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-2/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- ADB. Myanmar Energy Consumption Surveys; ADB: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, M.A.; Karali, N.; Letschert, V. Forecasting Indonesia’s electricity load through 2030 and peak demand reductions from appliance and lighting efficiency. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2019, 49, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEMR. Handbook of Energy and Economic Statistics of Indonesia; Final Edition; Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy and Mines Lao PDR. Lao PDR Energy Statistics 2018; Ministry of Energy and Mines Lao PDR: Vientiane, Laos, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).