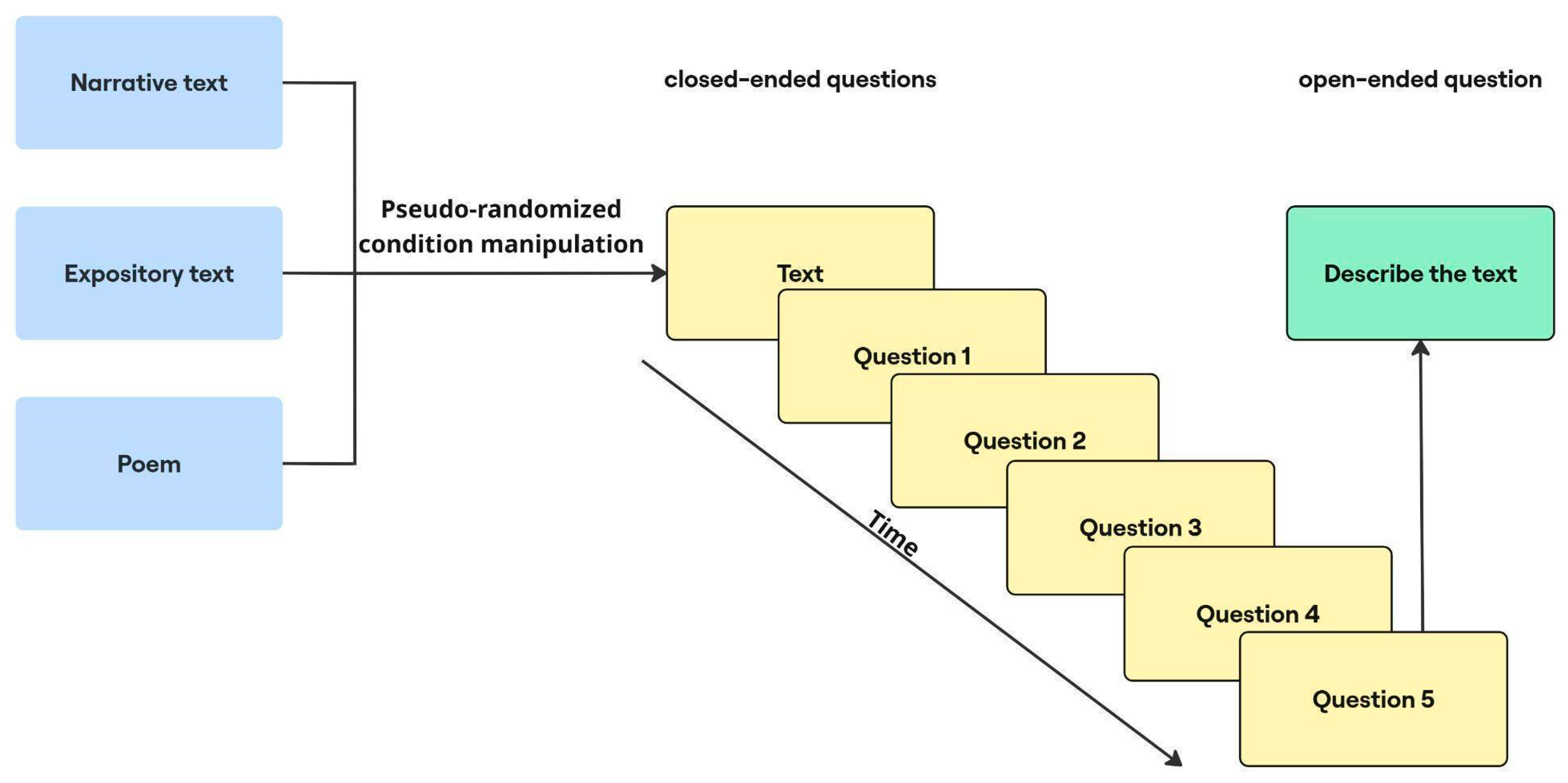

4.1. Reading Comprehension, Number of Returns to Text, Participant’s Age and Text Genre

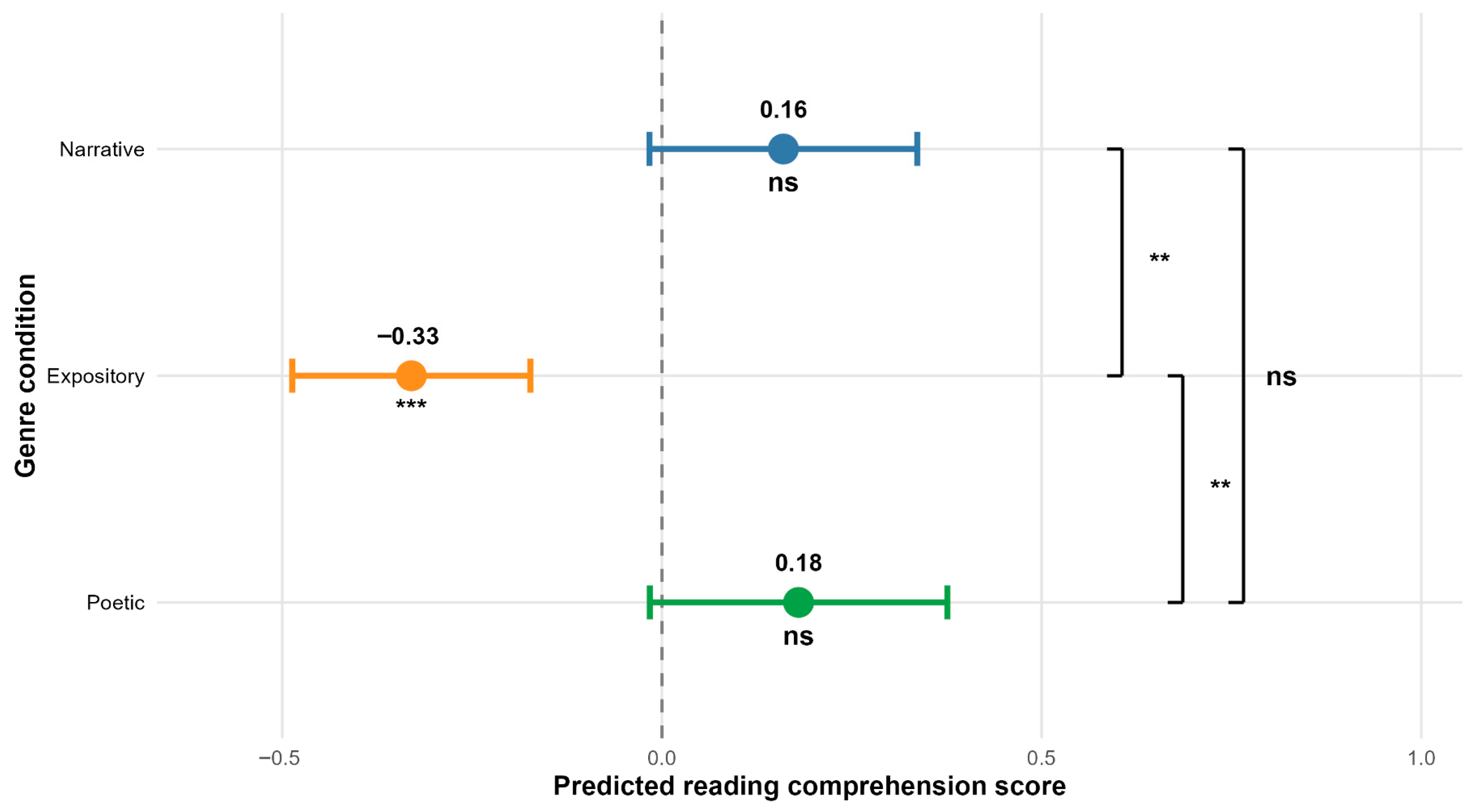

In our study, we showed that narrative text is easier to comprehend than expository text, thereby corroborating the findings of several earlier investigations synthesized in the meta-analysis by Clinton et al. [

43]. This difference likely arises because narrative texts are organized around characters’ goals and a chronological sequence, which helps readers anticipate logical connections among ideas, whereas expository texts employ a more varied structure that hinders their processing; furthermore, the vocabulary of narrative texts is organized more simply—both in terms of word length and usage frequency—than that of expository texts.

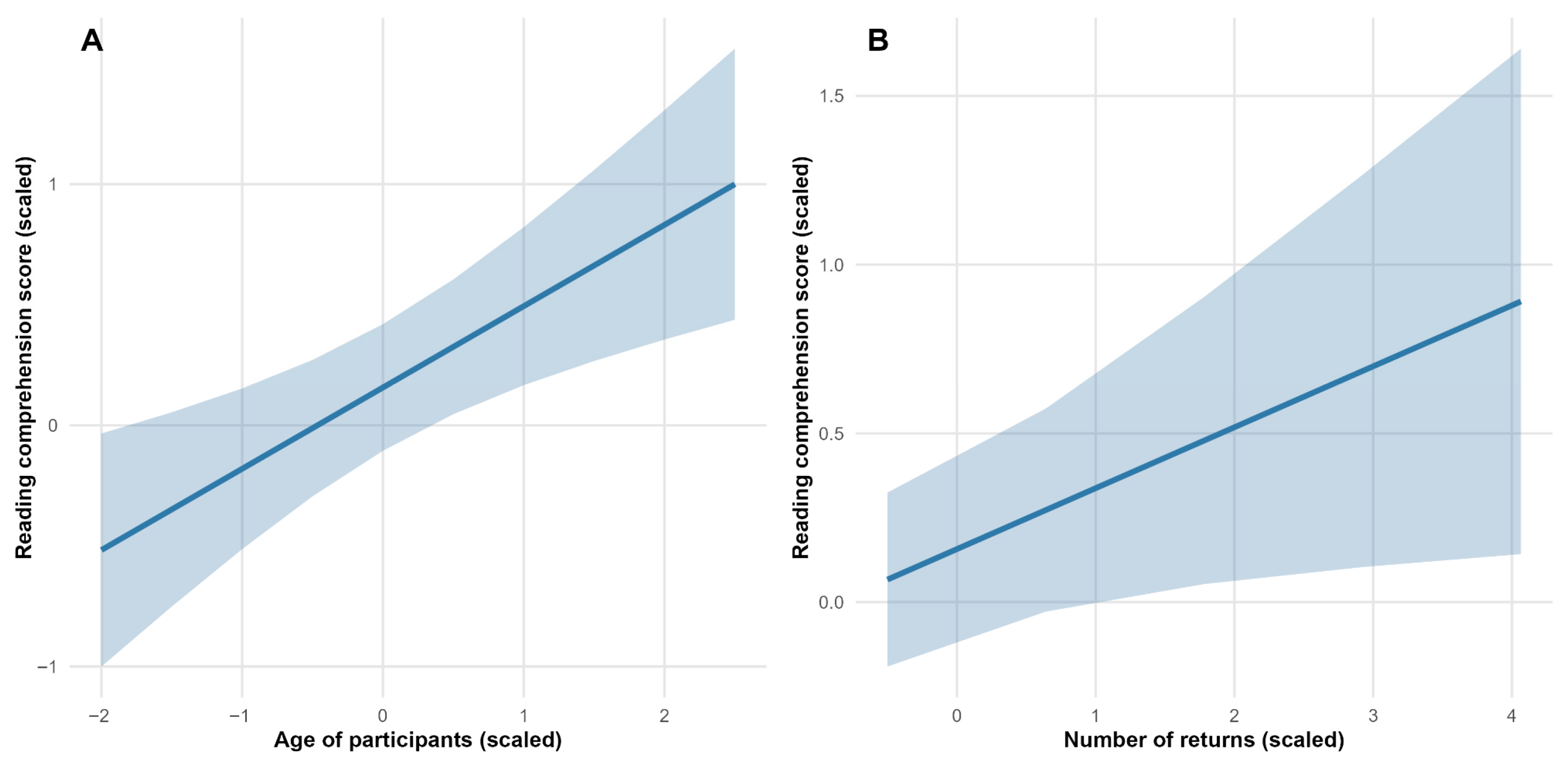

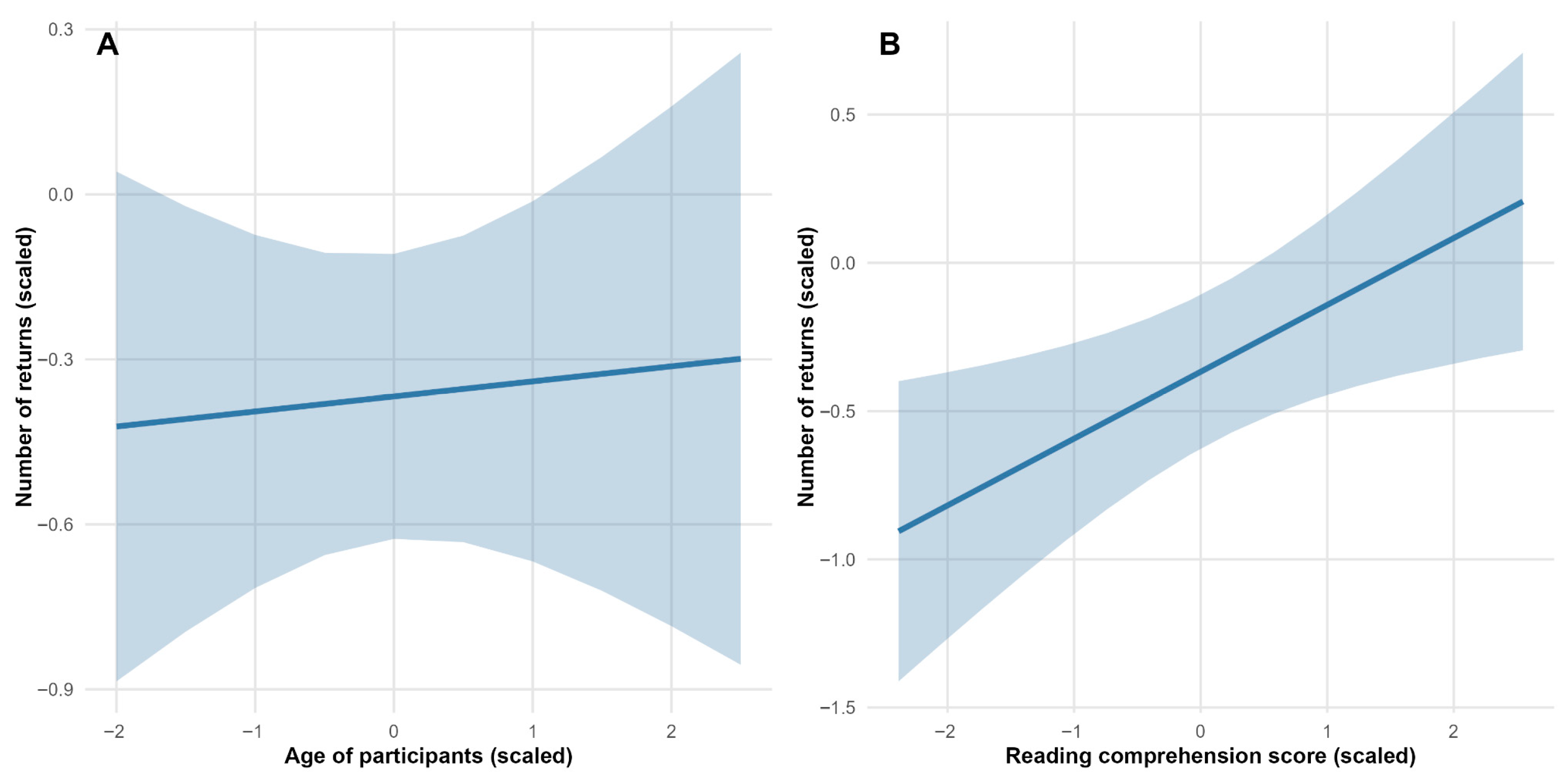

We found that a higher number of returns to the text for rereading predicted better reading comprehension. This result aligns with previous studies demonstrating that increased rereading reflects deeper text processing and leads to improved comprehension. Notably, blocking the opportunity to reread previously read text has been shown to negatively affect comprehension [

44]. Similarly, Strukelj and Niehorster [

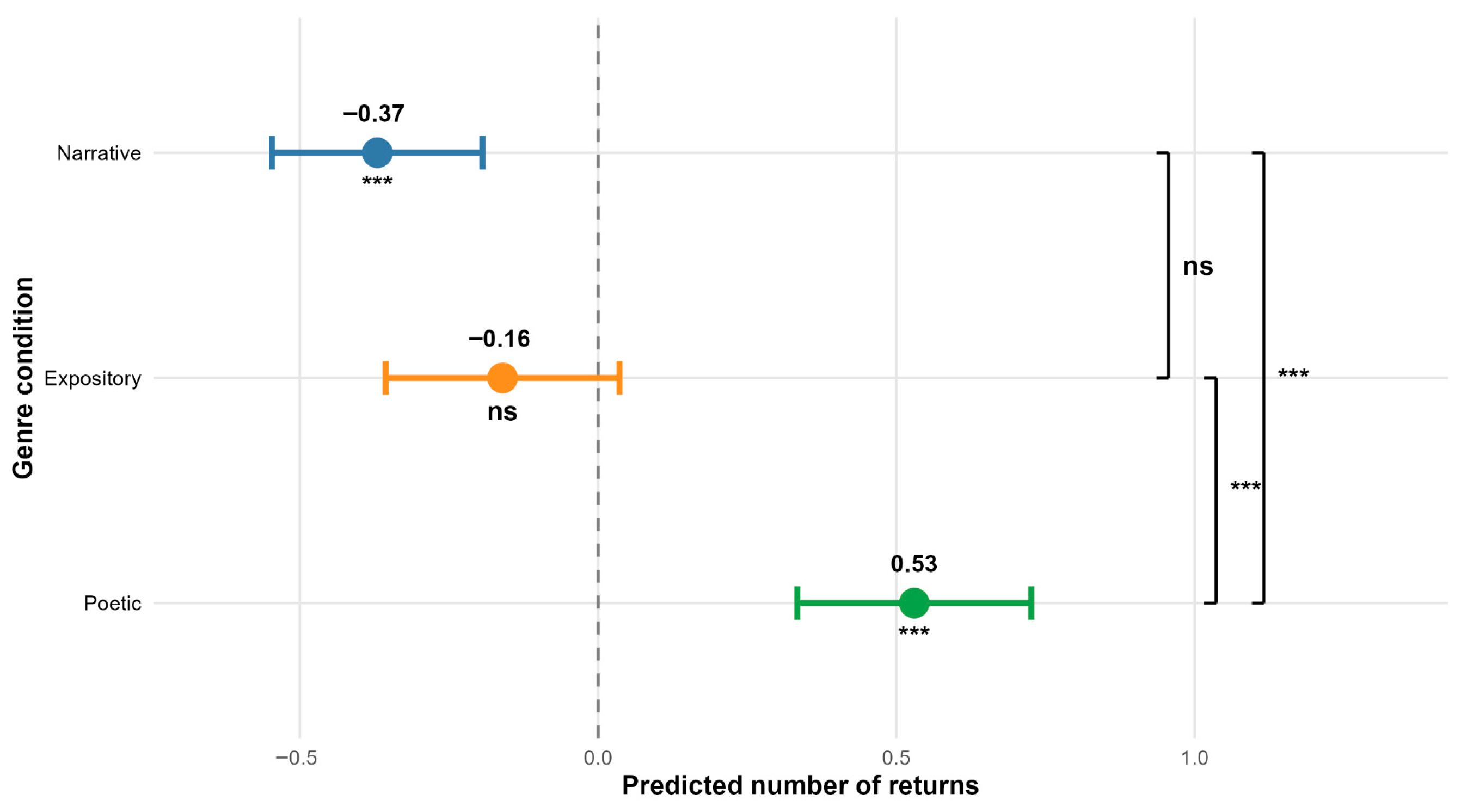

45] observed that thorough reading—characterized by longer total reading times and more rereading—resulted in higher comprehension scores compared to regular reading, skimming, or spell-checking tasks. These findings underscore the importance of revisiting textual content for constructing coherent meaning representations. In addition, we found that there was a greater number of returns to the text in the poetry text condition, which on one hand may indicate a need for deeper processing of the abstractions inherent in poetry. Interpreting poetry often requires additional cognitive effort on the part of the reader, as poetry is often characterized by figurative language. In other words, poetry cannot always be understood if interpreted literally. Thus, rereading may indicate additional cognitive operations that the reader performs in order to understand metaphors and other stylistic devices. However, figurative language often allows poetry to be interpreted in different ways. Understanding of poetry depends on individual differences and according to their life experiences and preferences [

17]. In narrative and expository texts, the number of interpretations is limited, as the linguistic means used in these texts do not allow for such variability in terms of possible interpretations. For the narrative text, the number of returns to the text decreased, which may indicate a simpler structure of the narrative text that does not require deeper processing.

Our results showed a positive correlation between age and reading comprehension in the adolescent group, suggesting that as age progresses, reading comprehension levels also increase. This finding is consistent with the findings of numerous studies that have demonstrated that older adolescents employ reading strategies that facilitate enhanced comprehension [

46,

47]. In our previous work, Berlin Khenis et al. [

27] also demonstrated a positive correlation between the age of participants within the adolescent group and their working memory and vocabulary scores. This may also explain why reading comprehension increased with age in the current study.

4.2. Eye Movement Patterns

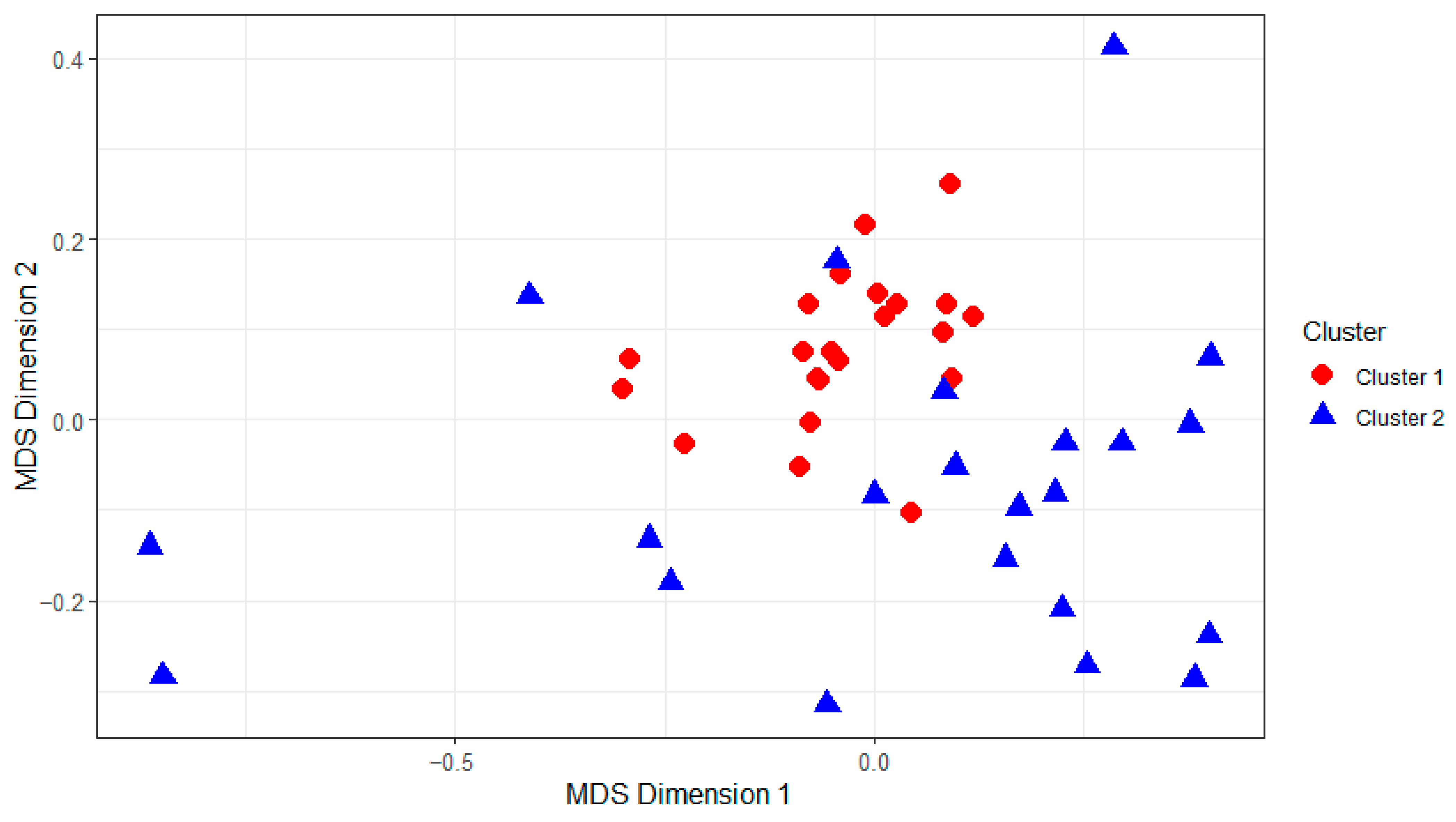

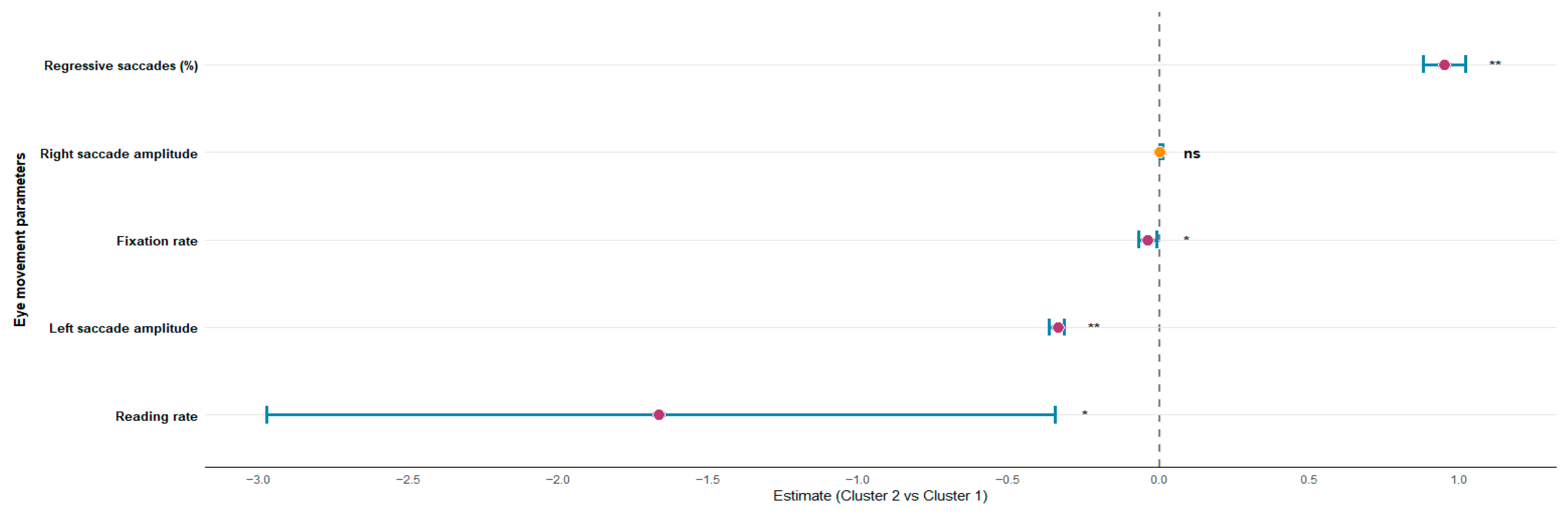

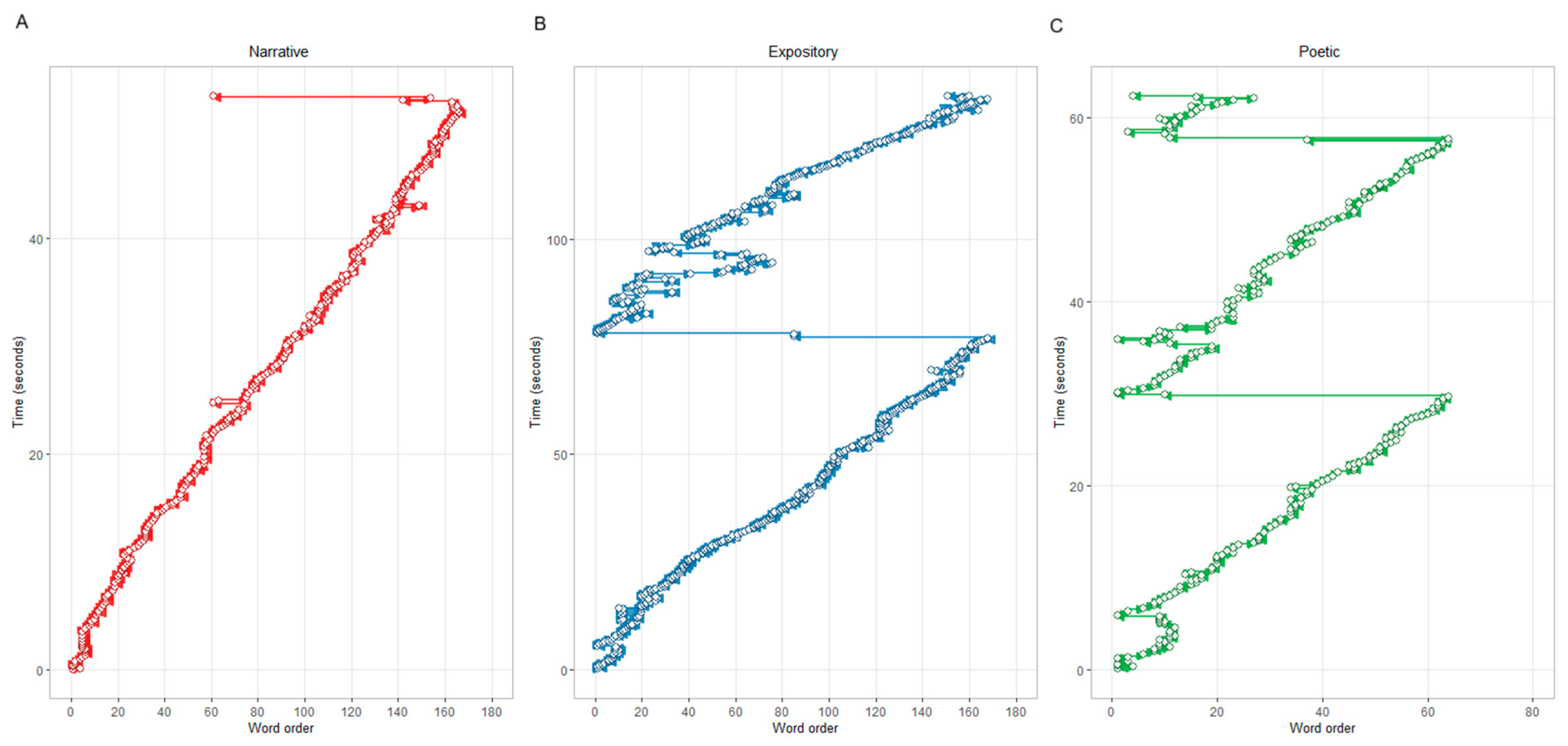

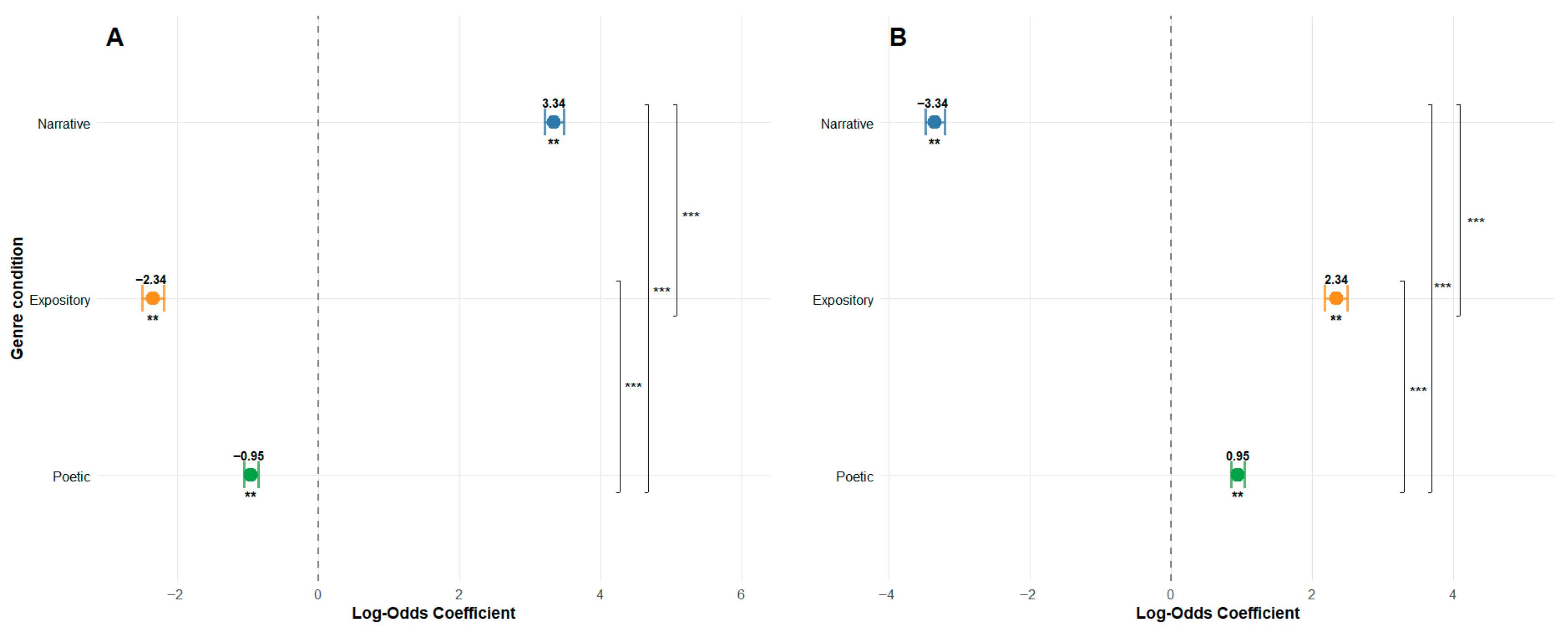

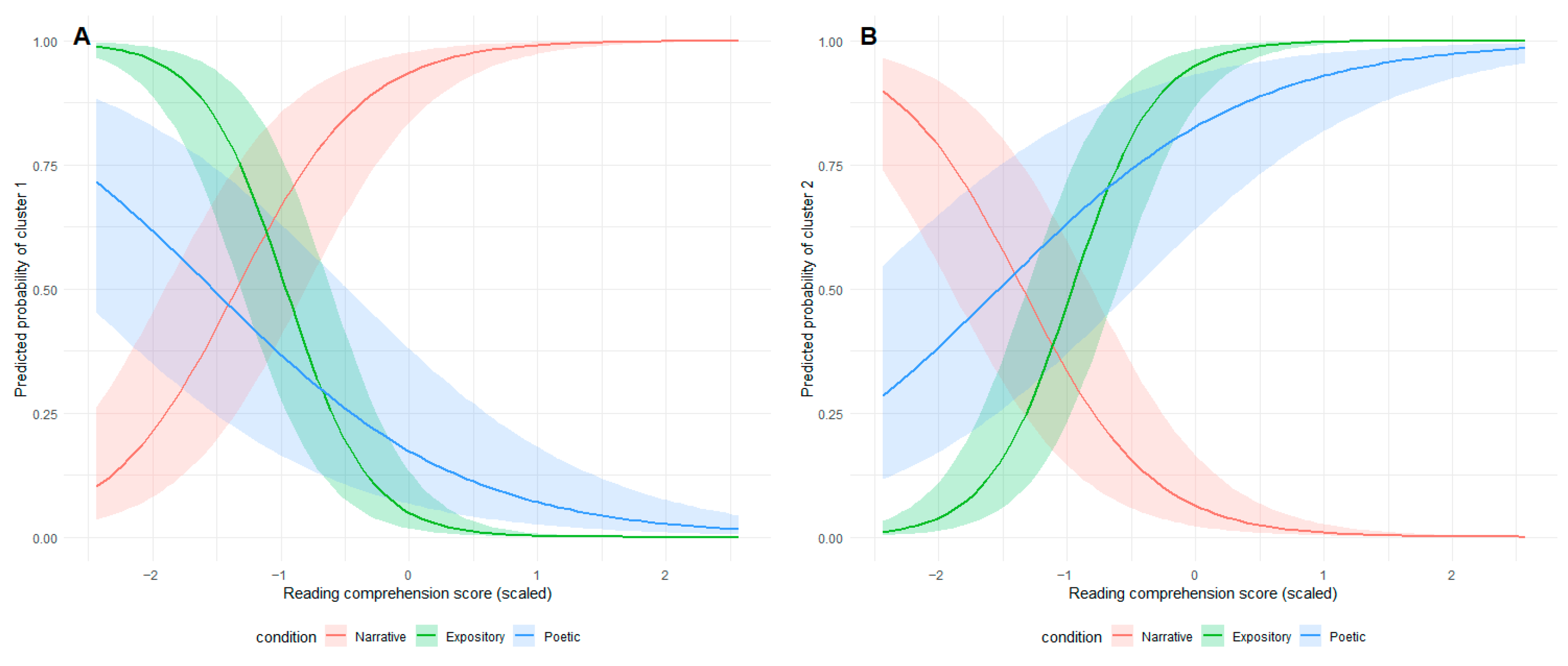

During the eye movement analysis, we identified two groups of scanpaths. Based on the combination of eye movement characteristics, we classified the reading patterns in the first group as the forward reading patterns and those in the second group as regressive reading patterns. This classification arose from the observation that the first group is represented by the reading patterns with fewer regressions with greater amplitude, along with higher reading and fixation rates. In contrast, the second group is characterized by patterns with a higher number of regressions with shorter amplitude and lower reading and fixation rates. Analyzing the relationship between these clusters and text genres, the level of reading comprehension and age, we found that the likelihood of employing forward reading patterns increases when reading narrative texts. Moreover, a higher comprehension score of such texts enhances this tendency. Interestingly, expository and poetic texts have a negative effect on the probability of using this pattern, and higher comprehension scores only increased this effect. Conversely, the use of the regressive reading pattern becomes more likely when reading expository and poetic texts and this tendency also grows with enhancing comprehension of these texts. In contrast, narrative texts exhibit the opposite effect, reducing the probability of using such patterns. Thus, following our first research question we confirm that reading patterns vary depending on the text genre. However, the answer to the second research question was less clear and contradicted initial expectations. Contrary to the hypothesis that increased comprehension would lead to an overall reduction in regressions, we found that comprehension modulated different reading patterns (forward or regressive reading pattern) depending on genre. Moreover, the overall trend, independent of genre, showed that increased reading comprehension generally increased the likelihood of the regressive reading pattern and decreased the likelihood of using forward reading patterns.

Many models of discourse comprehension focus on examining the nature of mental representations that emerge during reading [

48]. Text comprehension depends on multiple factors, including genre and associated with genre expectations, which are based on previously acquired knowledge about textual structures, genre-specific reading strategies, genre functions, and communicative purposes [

49,

50,

51,

52]. Genre expectations may influence the reading strategies which readers employ when approaching a text. Furthermore, as previous research has demonstrated, such strategic choices may be determined by accumulated experience with a particular genre, its typical text length or genre-specific coherence expectations, all of which affect which reading strategies are adopted [

52,

53,

54]. Thus, the patterns we identified—distinguished by oculomotor activity and showing differential probabilities of being employed with different text genres—fit well within this theoretical framework.

Our results indicate that expository and poetic texts increase the likelihood of employing the regressive reading pattern, which is characterized by a higher frequency of regressions compared to forward reading patterns. Current research associates regressive eye movements with problem-solving strategies during reading, whether related to lexical access difficulties, syntactic processing challenges, or discourse-level comprehension issues [

44,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Furthermore, recent scanpath analysis studies have demonstrated that reading patterns with more regressions tend to correlate with a lower level of text comprehension skill [

3,

27]. This suggests that the adoption of regressive reading patterns may reflect attempts to overcome comprehension difficulties. However, previous studies have shown that there are differences in reading strategies between prose and poetry. Specifically, several studies have found a difference in reading time, with poetic texts being read more slowly, and in eye movement patterns, with more regressions when reading poetry as compared to prose [

16,

17]. Given these established differences between poetic and prose genres, we hypothesize that the underlying cognitive mechanisms driving these regressions likely differ between genres.

As previously discussed, studies have identified consistent differences in processing strategies, as well as in the speed and accuracy of comprehension, between expository and narrative genres. Schmitz et al. [

59] suggest that the differences they observed in text comprehension between these genres may largely be due to variations in global cohesion. The authors build on the claim that reading literary fiction is typically associated with pleasure [

53] and operates in a “wait-and-see” mode [

51]. Readers naturally construct causal connections as they progress through the text [

60], integrating fragments into a unified mental representation. Despite the narrative genre used in our study not being directly related to literature, the coherence effects highlighted by Schmitz et al. [

59] may still explain the likelihood of distinct reading patterns for these genres. Thus, the higher frequency of regressive eye movements in expository texts might reflect not merely their greater complexity compared to narratives, but specifically their lower coherence, which requires readers to revisit earlier segments to establish connections independently.

The influence of text coherence can also be applied to poetic texts as well, since processing metaphorical language and figurative devices may challenge the construction of propositional text models. However, when examining poetry comprehension, we must account for the additional effects of meter and rhythm [

18,

61,

62] as well as layout used in the traditional presentation of poetic texts [

63,

64]. Early theoretical work proposed that text comprehension can be explained through the structural building framework [

65,

66]. This framework posits that reading comprehension involves constructing a mental structure of the text. During initial reading stages, readers establish a foundation for these mental structures, which they subsequently develop by creating coherent information maps that connect new input with prior context. Blohm et al. [

16] suggested that during the early stages of poetry reading, readers form a rhythmic pattern foundation, which facilitates better rhythm perception as they progress through the poem. In contrast, when reading prose, after establishing an initial propositional model, readers may adopt a riskier strategy, where readers skip more words and progress faster through the text. This occurs because the established discourse model provides thematic constraints that enable faster processing as readers encounter more contextual information. This logic may also apply to silent reading, potentially explaining the differences between the reading patterns we identified. However, the exact mechanisms behind regressive patterns in poetry reading remain unclear. Beyond the challenges posed by metaphorical language processing, we must consider rhythmic and metrical influences. Beck and Konieczny [

62] demonstrated that metrical anomalies increased rereading, while Menninghaus and Wallot [

18] found no global changes in eye movement patterns when varying rhythm and meter conditions. Interestingly, they observed fewer regressions when readers gave high esthetic ratings, suggesting that esthetic appreciation may influence poetry reading strategies. Additionally, layout may contribute to poetry’s higher regression frequency compared to other genres. Fechino et al. [

64] compared eye movement characteristics when reading sonnets presented in either poetic or prose layout. The original poetic layout led to an increase in the number of regressions. The authors suggested that the initial categorization of the text, based on the reader’s experience and expectations of the structure of the text, influences their reading strategy.

Previous research has identified that a faster, more linear reading pattern with fewer regressions is typically associated with reading expository texts [

57,

67]. However, as discussed earlier, increased regression frequency generally indicates the use of reading strategies when encountering text difficulties. The finding that both expository and poetic texts show increased probability of regressive reading patterns when comprehension is considered provides further support for this interpretation. Drawing on different models of discourse comprehension (for instance, the Construction–Integration Model, the Structure-Building Framework, or the Landscape Model [

48]), our findings reflect an active reading process in which readers strive to construct a coherent mental representation of the text. In the case of narrative texts, which, as noted earlier, are typically organized around characters’ goals and a chronological sequence that helps readers anticipate logical connections among ideas, readers appear to build this representation relatively automatically, as evidenced by a forward reading pattern. In contrast, for expository and poetic texts—due to the specific challenges outlined above—readers experience greater difficulty in constructing a coherent representation. Under these conditions, they resort to an increased number of regressions, which facilitates the integration of textual elements into a unified mental model and, consequently, enhances comprehension. Notably, the comprehension factor itself demonstrated a significant main effect, increasing the likelihood of using a regressive reading pattern, which is consistent with prior research. This suggests that while genre characteristics and genre-based expectations undoubtedly influence reading strategy selection, the actual level of text comprehension achieved also plays a crucial role in modulating reading patterns.

The identified clusters differed in reading rate and fixation rate, indicating that texts read with the forward reading pattern were processed longer than those read with the regressive pattern. Previous research has shown that more regressions typically indicate a pattern where readers resolve comprehension difficulties, which is usually associated with increased reading time. Our results contradict these earlier findings. However, although the difference between clusters in reading rate and fixation rate reached statistical significance, the effect size was extremely small. Therefore, its interpretation remains questionable and requires further verification.

4.3. Limitations

The present study design has certain limitations and assumptions that should be considered when interpreting the results and planning future research. Previous studies have demonstrated that text topic, background knowledge, and personal preferences can significantly influence reading strategies and comprehension levels. We did not include these factors in the analysis. However, they represent a major issue that warrants dedicated investigation with consideration of genre-specific effects. Furthermore, the study was related to a single linguistic and cultural context and did not involve measures of cognitive factors like working memory or linguistic proficiency.

Although the stimulus materials were close to those that adolescents interact with at school, the use of the EyeLink equipment did not allow for the creation of a naturalistic setting. Reading with the chin and head fixed before a vertical screen might have influenced the results. Another limitation is that the study was conducted on a relatively small sample (N = 44).

The texts used in this study did not vary in terms of difficulty, though this factor is also important in reading analysis and genre research. We found that genres inherently differ in complexity regarding perception accuracy. However, it would be important to consider how reading patterns and text comprehension levels change depending on text difficulty within one genre.

Moreover, this study was focused on average adolescent readers. In future research, it would be worth analyzing whether the findings might extend to populations with reading difficulties or neurodiverse profiles.