Abstract

Changing risk dynamics and the demand for more personalized, technology-driven services have spurred innovation in insurance through Insurtech, reshaping how insurance is supplied, purchased, and managed. This paper systematically reviews the impact of Insurtech on insurance inclusion, guided by the PRISMA-P protocol. The review finds strong evidence that Insurtech enhances insurance inclusion by lowering transaction costs, improving accessibility, and broadening market participation. These effects are most visible in short-term insurance, where digital platforms and tailored products reach previously underserved populations. Beyond this primary finding, the review highlights how insurance inclusion is conceptualized and measured in the literature. Quantitative measures typically include penetration rates, density, and the proportion of households with insurance coverage, while broader indices account for availability, usage, and accessibility of insurance services. Qualitative approaches often emphasize mismatches between the products offered and those needed, particularly for vulnerable groups. Similarly, studies of Insurtech adopt both demand-side indicators (such as product uptake and coverage per user) and supply-side measures (including patents, capital inflows, and innovation outputs). These insights suggest that fostering Insurtech development, while addressing regulatory, access, and equity concerns, can significantly improve insurance inclusion and narrow protection gaps.

1. Introduction

Organizations that incorporate innovative business models and leverage technology to enhance and disrupt financial services have spearheaded a revolution in how financial systems operate. Analyses of FinTech’s impact on the financial sector have predominantly concentrated on banking and alternative banking (Arner et al., 2020; Philippon, 2019; Senyo & Osabutey, 2020; Wang, 2021). Despite this focus, a significant and growing stream of investment and venture capital is being channeled into InsurTech business models (Holliday, 2019). Financial market reports from Holliday (2019), De Stefano et al. (2023), and Re (2023) document this investment trend in capital markets for FinTech and InsurTech. Holliday (2019) reported that global investment in InsurTech reached USD 4.4 billion in 2018, up from USD 3.2 billion in 2017, with over 200 transactions completed that year.

More recently, De Stefano et al. (2023) noted a sector-wide contraction, with overall FinTech investment decreasing by 43% in 2022; the largest decline occurred in InsurTech, which saw a 50% drop. After peaking at USD 4.9 billion in 2021, InsurTech investment fell to a record low of USD 800 million by the fourth quarter of 2022 (De Stefano et al., 2023). This pattern of growth and subsequent decline can be linked to the urgent need for alternative methods of selling, pricing, and marketing insurance products during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The previous growth in InsurTech investment has contributed to greater accessibility, usage, and availability of insurance products, thereby potentially improving insurance inclusion. Consequently, fostering technological advancement in insurance through investment in InsurTech start-ups remains crucial. For InsurTech start-ups, sustainable growth and investment depend on a corresponding increase in the demand for their services and the proportion of the population participating in insurance. The investment decrease noted by De Stefano et al. (2023) coincides with a decline in global insurance penetration, which fell from 3.3% in 2020 to 3% in 2021 (Re, 2023). Therefore, InsurTech sustainability is intrinsically linked to insurance inclusion, as higher inclusion rates drive greater demand for both front-end and back-end InsurTech products. Existing literature on InsurTech development includes studies on its scientific progress and efficiency (Gabor & Brooks, 2017), its impact on industry structure (Alt et al., 2018; Xu & Zweifel, 2020), and its implications for regulatory systems (Bittini et al., 2022; Sibindi, 2022).

The theoretical framing of this review draws on institutional theory, which connects organizational innovation to market participation. According to Ediagbonya and Tioluwani (2023), functional institutions like insurers evolve through technological modernization, which reshapes norms, governance, and accessibility. Within this framework, InsurTech acts as an institutional innovation, reducing transaction costs, improving contract enforcement, and strengthening trust through digital transparency. By altering how institutions structure incentives and information flows, InsurTech fosters greater inclusion and market efficiency, particularly in emerging economies where institutional gaps are pronounced.

While research exists on insurance inclusion (Mathew & Sivaraman, 2021; Saeed et al., 2022; Zheng & Su, 2022) and on InsurTech’s impact on the insurance industry (Chang, 2023; Chatzara, 2020; Xu & Zweifel, 2020), there is currently no synthesized analysis of the different measures used for InsurTech and insurance inclusion. Furthermore, no systematic literature review consolidates studies examining the relationship between the two. This review investigates InsurTech and insurance inclusion through four key thematic questions derived from the literature, which are pertinent for future empirical analysis:

- What are the determinants and measurements of insurance inclusion?

- What is the impact of InsurTech on the market structure of the insurance industry?

- How is InsurTech measured in the literature?

- Does InsurTech contribute to insurance inclusion?

This study contributes to the emerging body of knowledge on InsurTech and insurance inclusion by systematically synthesizing global evidence using PRISMA-P guidelines. It is among the first to synthesize studies on how digital technologies, institutional mechanisms, and behavioral factors jointly influence inclusive insurance markets. Secondly the study is also among the first studies to focus on synthesis of qualitative and quantitate measures of InsurTech and insurance inclusion and how the differences in measures can yield conflicting results. The growing digitalization of insurance services underscores the importance of understanding how InsurTech promotes inclusive and resilient insurance ecosystems. Recent studies (Kiwanuka & Sibindi, 2024; Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al., 2024; Cosma & Rimo, 2024; Visagamurthy, 2025) have highlighted the strategic role of technology in enhancing consumer trust, accessibility, and participation, particularly in developing economies. These emerging insights reinforce the timeliness and policy relevance of this review. This review is presented in five sections. Following this Introduction, Section 2 describes the review methodology. Section 3 presents the results from the literature. Finally, Section 4 and Section 5 provide a critical discussion of the relationship between InsurTech and insurance inclusion, draw specific inferences, and conclude with recommendations for applying this knowledge.

2. Method

This study employs a systematic literature review (SLR) protocol to investigate the relationship between InsurTech development and insurance inclusion. To ensure transparency and reproducibility, the review adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, and the completed PRISMA checklist is provided in the Supplementary Material. The data collection process involved three key stages. First, studies pertaining to insurance technology development and insurance inclusion were sourced based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed in Table 1. The final stage consisted of a synthesis of the literature that explicitly links insurance technology (InsurTech) with insurance inclusion.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.1. Information Sources

The primary literature search was conducted using the Web of Science (WOS) database. To broaden coverage and minimize potential gaps, a supplementary search was performed directly within the databases of major academic publishers including Taylor & Francis, Emerald, Wiley, and Springer as well as on Google Scholar. This approach ensured the inclusion of relevant studies not indexed in WOS. Furthermore, the reference lists of pertinent articles and related documents from the Swiss Re Sigma and United Nations databases were scanned to identify additional publications for a comprehensive search.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy utilized the following key terms and phrases: “Insurtech”, “Insurance technology”, “Digital insurance”, “Mobile insurance”, “Financial inclusion”, “Insurance inclusion”, “Insurance access”, “Microinsurance”, “Insurtech development”, “insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”, and “link between insurance inclusion and insurTech”. Keyword and subject searches were executed across all databases and combined using the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” to refine results. Appendix B provides a more comprehensive summary of the search strategy

2.3. Study Design: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligibility for inclusion was contingent upon meeting the criteria outlined in Table 1 below. A summary of the eligibility criteria, quality assessment process, and synthesis method is provided below. Studies were selected for inclusion from the papers identified by team members using the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussions and the quality assessment criteria.

2.4. Selection Process

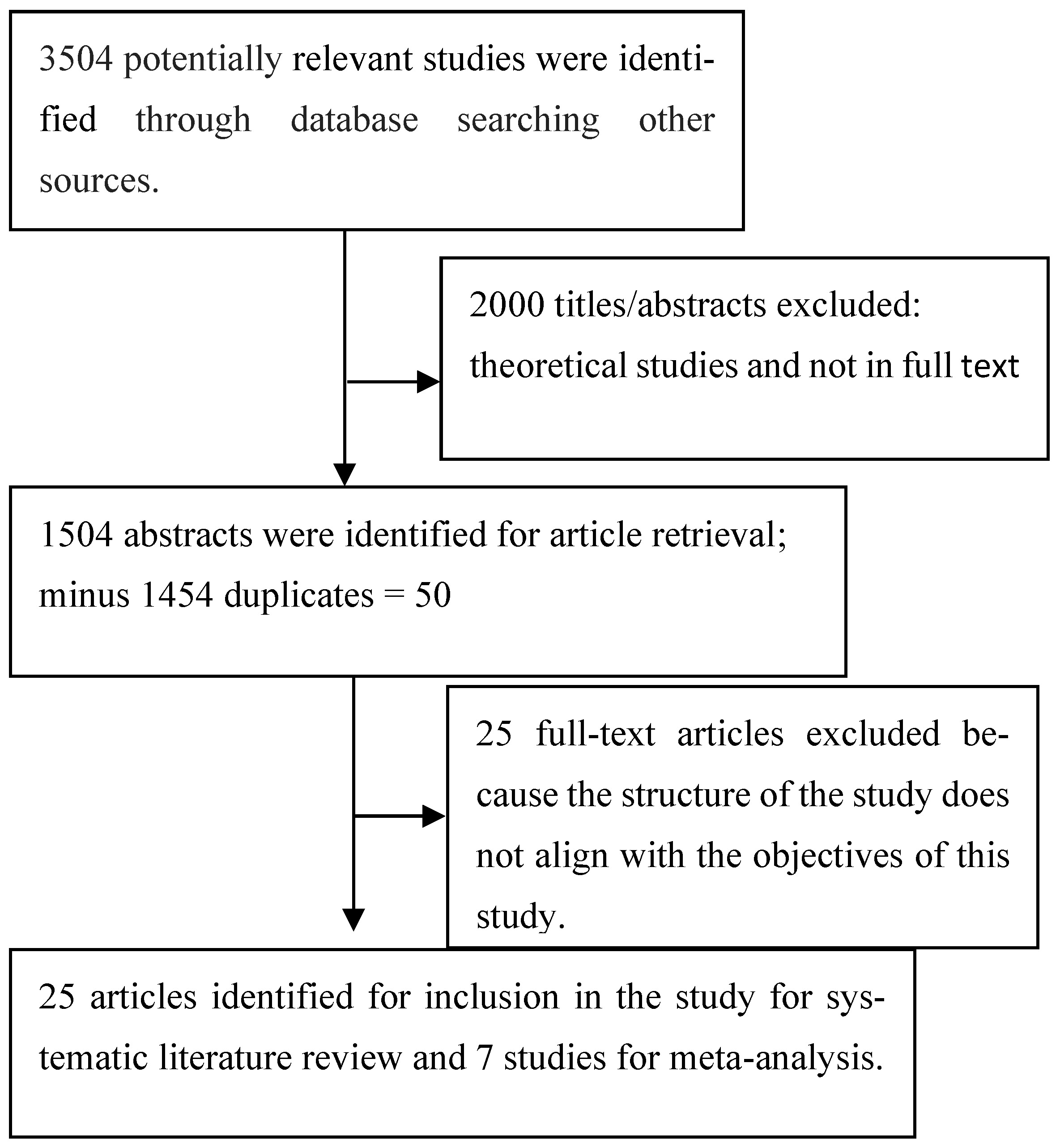

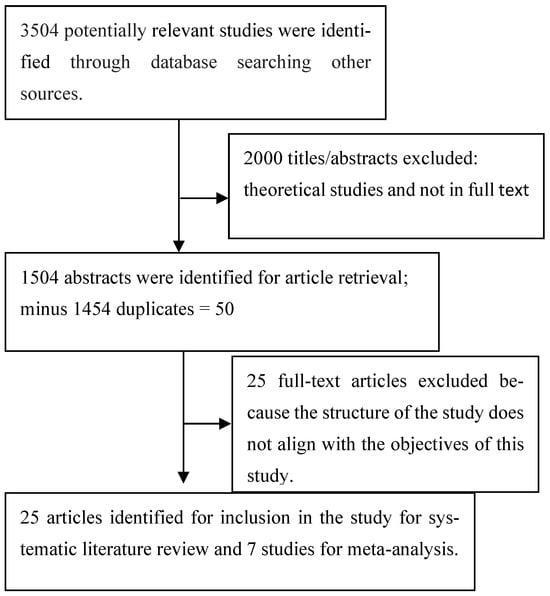

The application of the search strategy yielded 3504 potential studies; 2000 were excluded based on their titles and abstracts. The remaining 1504 papers were retrieved and reduced to 50 after removing duplicates, and 25 papers were ultimately left after thorough assessment of the papers using the outlined inclusion and exclusion criteria, specifically due to lack of empirical data and conceptual focus; most studies focused on financial inclusion, but this study focuses specifically on insurance inclusion and insurance technology studies. Although only 25 studies were ultimately included from an initial pool of 3504 identified publications, this rate of inclusion (<1%) aligns with expectations for systematic reviews that apply stringent quality and relevance filters under PRISMA-P guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). Each study was reviewed for methodological rigor, theoretical alignment, and empirical relevance to Insurtech and insurance inclusion. Excluded papers typically failed to meet design transparency or contextual applicability criteria. The focus on quality rather than quantity ensures robustness and reproducibility of insights. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. All exclusion counts and reasons are explicitly shown to enhance transparency using the model in (Page et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the retrieval of relevant studies.

2.5. Quality of Assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed as stipulated in the PRISMA-P statement in relation to the screening process. The protocol of the screening process involved looking into the research aim of each study and identifying if it answered any of the research questions of this study. Secondly, the quality assessment also focused on the studies that explain the development of insurance technology in the insurance market and insurance inclusion. Lastly, the sample size of these studies was reduced as some studies did not meet this quality assessment procedure.

2.6. Quality Assessment Tool

Quality appraisal of included studies followed standardized instruments appropriate to study design. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist was applied for qualitative and mixed-method studies, while the AMSTAR 2 tool was used for reviews and meta-analyses. Each article was rated on a 0–10 scale covering methodological transparency, theoretical alignment, and data reliability. Inter-rater reliability between the two authors yielded Cohen’s κ = 0.82, indicating substantial agreement. Studies below a threshold score of 5 were excluded from synthesis to minimize bias and enhance validity. Appendix A below reflects the different scores of the studies included on the CASP and the AMSTAR 2 tool.

2.7. Synthesis

A sample of 25 studies is included in this study, and the geographical precinct of these studies is not restricted to a particular area; instead, there are studies from South Africa, India, the United States of America, the Sub-Saharan Region, China, and Nigeria. A range of techniques was employed to form the synthesis of the evidence, based on the recommendation by Popay et al. (2006). Although the review follows PRISMA-P standards, a meta-analysis was not performed due to heterogeneity across studies in research design, measurement indicators, and outcomes. Instead, a narrative and thematic synthesis approach (Popay et al., 2006) was applied to capture conceptual convergence and contrast across qualitative and quantitative findings.

3. Results

By analyzing the data as captured from the synthesis stage discussed above, the following themes emerged, which are now discussed: (1) synthesis of insurance inclusion studies focusing on measurement, importance, and level of inclusion followed by theme; (2) synthesis of Insurtech studies focusing on measurement, importance, and impact on the market; and (3) synthesis of insurance inclusion and Insurtech to analyze the impact of Insurtech on insurance inclusion.

3.1. Insurance Inclusion (Measurement, Importance, and Level of Inclusion)

To establish a foundation for assessing the impact of Insurtech, it is essential first to understand how insurance inclusion is conceptualized and measured in the literature. The measurement of insurance inclusion is dominated by two complementary approaches. The first is the development of quantitative, multi-dimensional indices that seek to capture the core facets of inclusion. The foundational work of Sadayan (2023) established a paradigm by creating an Insurance Inclusion Index that equally weighted availability (number of corporations per 10,000 people) and usage (life and non-life policies per 10,000 adults). This methodology was refined in subsequent studies; for instance, Sankaramuthukumar and Alamelu (2011), in their analysis of India, expanded the usage dimension to include new premiums per 100,000 population while maintaining a focus on the density of offices and agents for availability. A slightly different quantitative framework was employed by Zheng and Su (2022), who focused on penetration (using density and depth), use efficiency (via coverage and payout levels), and accessibility (proxied by institutional presence and premium growth), thereby linking inclusion to market scale and consumer exposure.

Complementing these quantitative efforts is a second strand of research that employs qualitative and needs-based assessments. This perspective contends that numerical availability alone is an insufficient gauge of true inclusion. The study by Bakko and Kattari (2021) on the transgender community in the USA is a prime example, identifying a critical “inclusion gap” where the lack of coverage for transition-related healthcare constitutes a form of exclusion based on the unavailability of tailored products. This highlights that inclusion is inherently linked to how well products align with the specific risk-management needs of diverse populations.

When these measurement approaches are applied across different regions, stark disparities and distinct challenges come to the fore. The global landscape, as mapped by Sadayan (2023), reveals a widespread inclusion deficit, with 41 out of 58 studied countries reporting low levels. This is particularly acute in low-income regions, especially Sub-Saharan Africa. Research by Horvey et al. (2023) quantifies this, noting a penetration rate of just 2.7% for Africa compared to a 7% global average. The challenges in this region are often foundational. In Nigeria, Agbo and Nwankwo (2020) identify structural weaknesses such as a reliance on foreign underwriting and a lack of innovative distribution systems as primary barriers, even when channels like bancassurance are promoted.

In contrast, the context in large emerging economies like India and China involves different nuances. In India, studies like Sankaramuthukumar and Alamelu (2011) confirm low inclusion indices at the state level but also point to a growing recognition of the problem and efforts to measure it systematically. In China, Zheng and Su (2022) analyze inclusive insurance in relation to income distribution, finding that stronger inclusion is correlated with higher accessibility and efficiency at the provincial level, suggesting that the challenge is one of internal disparity as much as overall national penetration.

The discourse has been further expanded by recent studies highlighting the role of digital and behavioral factors as emerging determinants of inclusion, particularly in developing regions. Research in Uganda by Kiwanuka and Sibindi (2024) demonstrates that digital literacy, mediated by Insurtech adoption, is a critical pathway to inclusion. Similarly, in Morocco, Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al. (2024) show that digital transformation strengthens trust and behavioral commitment among policyholders. These findings signify a regional convergence on a new understanding: in technologically advancing economies, inclusion is increasingly determined not just by traditional affordability or physical access, but by an individual’s digital capability and willingness to engage within a digital ecosystem.

In summary, the measurement of insurance inclusion has matured to capture its multifaceted nature, while regional comparisons highlight a deeply uneven global landscape. Developed and technologically advanced economies generally exhibit higher inclusion, whereas low-income regions face compounded barriers of infrastructure, awareness, and product relevance. This evolving understanding, which now incorporates digital and behavioral dimensions, sets the stage for evaluating how Insurtech directly influences these dynamics. A summary of these studies is provided in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Summary of studies on measurement of insurance inclusion and determinants.

While these insights clarify how insurance inclusion is captured and why it matters, they do not explain the technological forces reshaping the insurance market. The next subsection therefore turns to the concept of Insurtech, focusing on how it is measured and how it is transforming insurance markets globally.

3.2. Insurtech (Measurement, Importance, and Impact on the Market)

Having outlined how insurance inclusion is measured and its importance, this subsection examines Insurtech’s measurement, purpose, and growing impact on insurance markets utilizing studies in Table 3 below. Furthermore the study analyses the use and application of technology such as blockchain and artificial intelligence in the designing, pricing, marketing and claims of insurance products, which have been termed Insurtech, whereas the term FinTech is a broad term used for all technology in financial services (Wang, 2021). Wang (2021) further explained that the emergence of FinTech started in the banking sector, and it is anticipated that growth will move across the sectors. The studies that have analyzed Insurtech, focusing on its impact on the market structure, include Bian et al. (2023) and Saeed and Arshed (2022), whilst other studies such as Wang (2021), Wilamowicz (2019), and Zheng and Su (2022) have looked at the development and evolution of the Insurtech industry. Bian et al. (2023) explain that Insurtech in the insurance sector can be explained in three main categories, which are distributors, technology solution providers, and full-stack carriers. Distributors and solution providers are a form of outsourced third-party service provider, whereas full-stack carriers are full Insurtech registered insurance companies.

Table 3.

Summary of studies on measurement of Insurtech.

The studies that have analyzed the development of Insurtech at industry level and how it has impacted the market structure have used supply- and demand-side measures of Insurtech. Bian et al. (2023) measured the impact of Insurtech on the demand side (of insurance market) by proxying it with the number of insured people per 10,000 users of Airplay in each city, the average number of insurance products purchased by each account in each city on Airplay, and the average coverage per account in each city. Airplay is a technological platform that sells a range of products including insurance products and it is particularly popular in Asian countries. The supply side is measured using patents related to Insurtech with keywords such as big data, block chain, machine learning or cloud computing (Bian et al., 2023). Patents proxy the level of innovation and development of new products and can also show the level of research and development in Insurtech (Bian et al., 2023). The study also looks at the time that the insurance company started to sell insurance products on Airplay as a supply-side measure of development (Bian et al., 2023). Bian et al. (2023) further argues that these supply-side measures can also reflect the level of digital marketing, whilst patents also show the level of development of Insurtech based on newly designed products. Whilst Bian et al. (2023) looked at the supply side using patents, Liu et al. (2023) also looked at technological innovation using the sum of patents and trademark applications as a measure of the development of the supply side of Insurtech.

In a study of Insurtech start-ups and how they have disrupted the industry in the United States, Chang (2023) analyzed the different categories in which start-ups can affect the market. The initial measure of disruption is based on the new Insurtech innovations that lead to new ways of doing business, and this is measured using the total number of new creations or innovations throughout the year for Insurtech and new start-ups. Chang (2023) also looked at the capital market and how money is channeled into new start-ups that are related to Insurtech, which can also assist in understanding the level of financial support that has been attributed to Insurtech in the industry. Chang (2023) used the total amount of capital that is channeled in a year for Insurtech start-ups in the US. The growth of the Insurtech industry can also be identified by a demand-side measure of the number of people participating in the Insurtech industry. Chang (2023) classified companies based on their number of employees to measure the total human capital input for the year of Insurtech start-ups in the US (e.g., if the number of employees is 1–10, the firm is graded 1), up until grade 7; this also shows the size of the Insurtech company (Chang, 2023).

Other studies that have analyzed Insurtech have looked at other methods, such as a survey method with questions on user experience, and analysis of the general media conversation on Insurtech, such as in Xu and Zweifel (2020) and Cao et al. (2020), respectively. Cao et al. (2020) looked at the media prevalence and what the media has been communicating regarding Insurtech and focused on term frequency to check the evolution of the conversation on Insurtech as a measure of development. The International Telecommunication Union (2023) designed a generic index for measuring the development of technological products in the market known as the ICT development index. Xu and Zweifel (2020) also investigated Insurtech using a survey with items which include firm specifics, experience with Insurtech, perceived threats and opportunities, and the response of incumbents to Insurtech.

The growth and development of Insurtech has been found to have disruptive effects on the market of non-life insurance more than it affects the life insurance market (Bian et al., 2023). Bian et al. (2023) explained that the nature of the life insurance business requires trust, high levels of capital and licensing systems, which have affected the entrance of Insurtech into the life insurance market. Wang (2021) states that, internally, the impact of Insurtech heavily affected the liability and asset side of insurance companies’ balance sheets and further increased their risk-taking behavior. Wang (2021) found that Insurtech alleviates financing constraints and then improves technological innovation in the insurance sector. Secondly, Wang (2021) also found that investment in Insurtech has significant differences in the impact on insurance businesses depending on the size. Chang (2023) found a substantial disruptive impact on the competitiveness of incumbents while exerting a weakly stimulating effect on premium growth. Chang (2023) found that firm size is critical in determining the degree of stimulation; specifically, smaller insurers with limited investments in Insurtech are more vulnerable to disruption. The study on media salience regarding Insurtech also found that the results of the word frequency analysis show that “insurance,” “science and technology,” and “finance” are the core concepts in conversations about Insurtech, while “platform” and “innovation” comprise the main content. “Financing” and “investment” were hot topics in the industry in both 2015 and 2016, but their importance dropped from 2017 to 2019 (Cao et al., 2020).

The scope of Insurtech innovation now spans both operational transformation and ethical governance. Cosma and Rimo (2024) describe how technology redefines insurance architecture into a data-driven, customer-centric ecosystem, emphasizing big data and automation as drivers of new value creation. The Holland and Kavuri (2024) study similarly shows that incumbents, not only start-ups, are leading this transformation by embedding Insurtech across processes and value chains. In developing economies, Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al. (2024) highlight that effective digital transformation also requires cultural and behavioral alignment within organizations. Complementing these, Visagamurthy (2025) brings an ethical dimension, arguing that algorithmic transparency and data integrity underpin the sustainability of digital insurance ecosystems. Together, these findings illustrate that Insurtech’s impact extends beyond technological disruption as a multidimensional transformation integrating innovation, human behavior, and digital ethics. Integrating cross-regional evidence reveals that Insurtech’s influence on inclusion is both technological and ethical. In Africa, Kiwanuka and Sibindi (2024) show that digital literacy enables inclusion through Insurtech adoption, while the FT Partners (2024) report identifies South Africa as a continental leader where Insurtech has boosted penetration to over 12 percent by expanding affordable access.

Together, these studies depict an industry where Insurtech is diffusing institutionally across firm types and geographies, moving from isolated technological adoption to system-wide transformation that integrates AI, blockchain, and customer-centric platforms. Across studies, Insurtech emerges as a disruptive yet enabling force. Supply-side indicators (e.g., patents, venture capital inflows) reveal rapid innovation, whereas demand-side measures (e.g., digital policy uptake) capture diffusion. The synthesis suggests that Insurtech reshapes market structure by improving efficiency, transparency, and consumer choice, though its benefits remain uneven across regions and firm sizes (Bian et al., 2023; Chang, 2023).

Although Insurtech has significantly reshaped the insurance landscape, the extent to which these technological developments translate into improved insurance inclusion remains unclear. The following subsection directly synthesizes evidence on how Insurtech affects insurance inclusion across different contexts.

3.3. The Impact of Insurtech on Insurance Inclusion

Following the establishment of how insurance inclusion is measured, this section examines the parallel evolution in quantifying InsurTech itself and its consequential impact on insurance markets with studies shown in Table 4 below. InsurTech, defined as the application of technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence to the design, pricing, marketing, and claims handling of insurance products, represents a specialized segment of the broader FinTech landscape (Wang, 2021). To capture the development and influence of this phenomenon, the literature has developed a suite of measurement approaches, primarily categorized into supply-side and demand-side indicators.

Table 4.

Summary of studies on Insurtech and insurance inclusion.

Supply-side metrics are designed to gauge drivers of innovation within the InsurTech ecosystem. A common proxy is the level of research and development, measured through patent filings and trademark applications related to core technologies such as big data, machine learning, and blockchain (Bian et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). These indicators serve as a barometer for the technological sophistication and innovative capacity of the industry. Beyond R&D, financial backing is a critical supply-side measure. Chang (2023), in a study of the US market, utilized the total amount of capital channeled into InsurTech start-ups, arguing that venture capital inflows reflect market confidence and the financial fuel for disruption. Similarly, human capital investment, measured by the employment size and growth within InsurTech firms, provides an indicator of the sector’s expansion and scaling potential (Chang, 2023).

Complementing these are demand-side and qualitative measures, which assess market adoption and perception. Bian et al. (2023) exemplified demand-side measurement by tracking the number of insureds per user, average products per account, and coverage per account on digital platforms like Airplay. Alternatively, qualitative approaches capture the industry’s evolving discourse. Cao et al. (2020) employed text mining of media reports, using term frequency analysis to reveal shifting conversations from “financing” and “investment” to “platform” and “innovation,” signaling the sector’s maturation. Surveys, such as those conducted by Xu and Zweifel (2020), offer another vital qualitative lens, capturing industry perceptions of threats, opportunities, and the experiential impact of InsurTech on traditional business models.

The application of these metrics reveals that InsurTech’s impact on market structure is significant yet heterogeneous. A consistent finding across studies is that the disruptive effect is most pronounced in the non-life insurance sector. Bian et al. (2023) attribute this disparity to the nature of life insurance, which demands high levels of trust and significant initial capital and operates within stringent licensing systems, thereby presenting higher barriers to entry for new InsurTech carriers. Furthermore, the impact varies considerably by firm size. Research by Wang (2021) and Chang (2023) converges on the conclusion that smaller insurers with limited capacity to invest in new technologies are more vulnerable to competitive disruption from agile start-ups. However, for those that can invest, InsurTech can alleviate financing constraints and spur further technological innovation, indicating a bifurcated effect within the incumbent market (Wang, 2021).

The scope of InsurTech’s influence is now understood to extend beyond mere operational disruption to encompass a broader multidimensional transformation. Contemporary research describes a shift towards a data-driven, customer-centric ecosystem where big data and automation are key drivers of value creation (Cosma & Rimo, 2024). This transformation is not limited to start-ups; incumbents are increasingly embedding InsurTech across their processes and value chains to maintain competitiveness (Holland & Kavuri, 2024). This institutional diffusion highlights that InsurTech is maturing from a peripheral novelty into a core component of the industry’s strategic fabric.

Regional analyses add further nuance to this picture. In advanced and large emerging economies, the focus is on market structure disruption and competitive dynamics, as seen in the studies of the US (Chang, 2023) and China (Bian et al., 2023; Wang, 2021). In contrast, evidence from developing regions like Africa highlights InsurTech’s role in fostering inclusion. In Uganda, Kiwanuka and Sibindi (2024) demonstrate that digital literacy, mediated by InsurTech adoption, is a critical pathway to insurance inclusion. Success stories, such as South Africa where InsurTech has helped boost penetration, underscore the potential for technology to expand affordable access (FT Partners, 2024). However, as Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al. (2024) note in the context of Morocco, this requires cultural and behavioral alignment within organizations, while Visagamurthy (2025) emphasizes that ethical governance and algorithmic transparency are crucial for building the sustainable trust necessary for inclusive digital ecosystems.

In synthesis, the measurement of InsurTech reveals a dynamic and rapidly evolving field. Supply-side indicators point to vigorous innovation, while demand-side metrics capture its growing market integration. The collective evidence confirms that InsurTech is a powerful force reshaping insurance markets by enhancing efficiency, transparency, and consumer choice. Yet its benefits are not uniform, varying significantly by insurance segment, firm size, and regional context, with its potential for fostering inclusion being most critical in developing economies.

4. Discussion

This systematic review sought to synthesize global evidence on the relationship between InsurTech and insurance inclusion. The findings confirm that InsurTech acts as a potent institutional innovation capable of enhancing inclusion by fundamentally altering the availability, accessibility, and affordability of insurance services. However, a critical interpretation of the literature reveals that its efficacy is not automatic but is profoundly mediated by the institutional and behavioral contexts in which it is embedded.

The synthesis of measurement approaches underscores a critical theoretical insight: the conceptualization of insurance inclusion itself is evolving. The transition from simple penetration rates to multi-dimensional indices (Sankaramuthukumar & Alamelu, 2011; Sadayan, 2023) and qualitative needs-based assessments (Bakko & Kattari, 2021) reflects a deeper understanding of inclusion as a function of institutional design. This aligns with institutional theory, which posits that functional institutions evolve to reshape norms, governance, and accessibility (Ediagbonya & Tioluwani, 2023). The identified inclusion gap for specialized communities is not merely a market failure but an institutional one, where existing structures and product norms fail to incorporate diverse populations. InsurTech, from this perspective, serves as an external shock that can disrupt these entrenched institutional arrangements.

The differential impact of InsurTech across market segments and regions can be powerfully explained by this institutional lens. The finding that InsurTech disrupts non-life insurance more than life insurance (Bian et al., 2023) is not just a technical observation but a testament to the resilience of deeply institutionalized sectors. The life insurance market is built on long-term contracts requiring high trust and significant capital—institutional attributes that are less susceptible to purely technological disruption. Similarly, the vulnerability of smaller firms (Chang, 2023; Wang, 2021) highlights how pre-existing institutional resources and capabilities determine an organization’s ability to adapt to innovation, a core tenet of institutional theory.

Furthermore, the stark contrast in InsurTech’s inclusion outcomes between developed and developing economies underscores the theory’s emphasis on the wider institutional environment. In more technologically advanced economies, robust digital infrastructure, high consumer trust, and adaptive regulatory frameworks provide a fertile institutional ground for InsurTech’s efficiency gains to translate directly into broader inclusion. In contrast, the weaker institutional settings of many developing nations reveal a critical caveat: technological innovation alone is insufficient. The findings from Uganda (Kiwanuka & Sibindi, 2024) and Morocco (Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al., 2024) introduce a crucial behavioral and cognitive layer to this institutional analysis. They demonstrate that for InsurTech to fulfill its inclusive potential, the institutional environment must also foster digital literacy and trust. This bridges institutional theory with behavioral economics, suggesting that the “modernization” of market structures must be accompanied by a corresponding enhancement of human capabilities and confidence. Mueller’s (2018) caution that efficiency does not automatically equate to inclusion is validated here; without complementary investments in digital literacy and infrastructure, the institutional gaps that hinder inclusion will persist, and technological efficiency may even exacerbate inequalities by excluding the digitally marginalized.

In conclusion, this review demonstrates that the impact of InsurTech on insurance inclusion is best understood not as a simple technological causal chain, but as a complex interplay between innovation, institutional context, and behavioral factors. InsurTech functions as a powerful enabling force, but its ultimate effect on inclusion is contingent upon the institutional readiness to support it and the behavioral readiness of the population to adopt it. This synthesized framework provides a more nuanced explanation for the varying outcomes observed in the literature and highlights that fostering inclusion requires a holistic strategy that targets technology, institutional regulation, and human capital simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

The study shows a holistic analysis of literature about Insurtech and Insurance inclusion and gives a comprehensive analysis of the measures, determinants, and country-specific issues. The results of the study also show that there are different measures of the two variables in question from quantitative and qualitative measures depending on the context of the study. The study also found that the link between Insurtech and insurance inclusion is sparsely researched, and the following areas need to be further investigated:

- The impact of Insurtech on the market structure in the African context;

- The impact of Insurtech and insurance inclusion on a country-specific and regional scale;

- The impact of Insurtech on the adaptation of natural disaster insurance;

- The link between Insurtech uptake, bancassurance and insurance inclusion on a regional and national scale.

5.1. Recommendations of the Study

The review demonstrates that InsurTech acts as a disruptive institutional innovation, challenging legacy market structures and norms. To channel this disruption positively, policymakers must transition from static regulatory models to adaptive, evidence-based frameworks. This approach is directly justified by the identified risks of algorithmic bias in pricing, data privacy concerns, and the potential exclusion of non-digital customers, as highlighted by Chatzara (2020) and Mueller (2018). The establishment of regulatory sandboxes, as implied by the need for institutional modernization (Ediagbonya & Tioluwani, 2023), would create a controlled environment for testing new business models while safeguarding consumer interests. Furthermore, guidelines for algorithmic transparency and data governance are no longer optional but essential to build the trust that underpins sustainable inclusion, a concern elevated by Visagamurthy (2025). Without this proactive and balanced regulatory posture, the review suggests that the efficiency gains of InsurTech could inadvertently widen the very protection gaps they aim to close.

Another key recommendation concerns the critical human moderating role, and infrastructural capacity demands a dual-pronged investment strategy focused on both digital infrastructure and literacy. The stark contrast in inclusion outcomes between developed and developing economies, and the specific micro-level evidence from Uganda (Kiwanuka & Sibindi, 2024), proves that technological access is futile without the capability to use it. Therefore, investments must be concurrent and synergistic. Governments and development partners must prioritize building robust digital foundations, including widespread internet connectivity and mobile payment systems as a public good. Simultaneously, and with equal vigor, they must fund and implement large-scale digital and financial literacy campaigns. As the findings show, building this human capital is not a secondary concern but a primary prerequisite; it is the crucial mechanism that translates technological availability into genuine adoption and usage, thereby activating the inclusion pathway.

Furthermore the review underscores that true inclusion is measured not only by quantitative access but by qualitative relevance. The documented inclusion gaps for communities such as the transgender population in the U.S. (Bakko & Kattari, 2021) and smallholder farmers in China (An et al., 2023) serve as a powerful mandate for fostering inclusive product design through strategic partnerships. Insurers must leverage the very technologies driving this change such as AI and data analytics not merely for operational efficiency but for hyper-personalization and needs assessment. This can be achieved by moving beyond traditional silos and forming collaborations with community organizations, agricultural boards, and distribution channels like bancassurance networks (Agbo & Nwankwo, 2020). Such partnerships provide the vital market intelligence required to co-create affordable, micro-coverage products that are directly tailored to the unique and localized risks faced by underserved groups.

Finally, the identified geographical bias in the literature itself, with a scarcity of focused research on regions like Africa where insurance gaps are most severe (Horvey et al., 2023), points to a final, overarching implication and the need for strategic, targeted funding to bridge regional InsurTech development gaps. The promising results from specific cases, such as the role of InsurTech in boosting penetration in South Africa, demonstrate the latent potential. To unlock this more broadly, venture capital, impact investors, and international development agencies must deliberately channel resources into InsurTech start-ups and research initiatives based in and focused on emerging economies. Supporting homegrown solutions that understand local institutional, cultural, and risk landscapes is imperative to ensure that the global InsurTech revolution does not bypass the populations who stand to benefit from it the most.

In conclusion, the journey toward deeper insurance inclusion in the digital age is not a simple matter of deploying technology. It is a complex endeavor that requires a holistic ecosystem approach. By implementing adaptive regulation, building dual digital and human foundations, championing relevant product design, and directing capital strategically, stakeholders can ensure that the promise of InsurTech is translated into tangible, equitable, and sustainable inclusion for all.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

While this review provides actionable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, most of the included studies originate from Asia, Europe, and North America, resulting in a geographical bias that limits the generalizability of findings to Africa and Latin America, where insurance inclusion challenges are most severe. Future research should address this imbalance through regional case studies and cross-country comparative analyses. Second, the dataset largely covers publications up to 2022, whereas Insurtech developments—particularly in AI-driven underwriting, blockchain-enabled microinsurance, and embedded finance—have accelerated thereafter (Re, 2023). Continuous updates are therefore required to maintain the practical relevance of conclusions. Third, despite systematic procedures, variations in definitions and indicators of insurance inclusion may constrain comparability across studies.

Finally, the rapidly evolving nature of Insurtech represents a further challenge. Technological innovations such as blockchain, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things are advancing quickly, and findings from earlier studies may not adequately capture the current landscape. This dynamism underscores the need for continuous, updated research that can keep pace with the industry’s evolution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jrfm19020122/s1. Morgan (2022) and Zia and Kalia (2022) are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.M. and S.M.; methodology, F.B.M. and S.M.; software, F.B.M. and S.M.; validation, F.B.M. and S.M.; formal analysis, F.B.M. and S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.M.; writing—review and editing, F.B.M.; visualization, F.B.M.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, F.B.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Each study was scored on a 0–10 scale, adapted from CASP/AMSTAR2 criteria (high quality (8–10), medium quality (6–7), low–medium quality (5–6)).

| Author and Year | Study Type | Quality Tool | Score (0–10) | Quality Rating |

| Sankaramuthukumar and Alamelu (2011) | Quantitative index | CASP | 8 | High |

| Sadayan (2023) | Quantitative index | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Agbo and Nwankwo (2020) | Case analysis | CASP | 6 | Medium |

| Zheng and Su (2022) | Econometric model | CASP | 9 | High |

| Bakko and Kattari (2021) | Survey | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Horvey et al. (2023) | Panel econometrics | CASP | 8 | High |

| Mamta (2022) | Descriptive | CASP | 6 | Medium |

| Mathew and Sivaraman (2021) | ARDL econometrics | CASP | 8 | High |

| Nechyporuk (2018) | Macro analysis | CASP | 6 | Medium |

| Vimala and Alamelu (2018) | Index measurement | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Kiwanuka and Sibindi (2024) | PL-SEM survey | CASP | 8 | High |

| Abdallah-Ou-Moussa et al. (2024) | Case study | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Bian et al. (2023) | Panel regression | CASP | 9 | High |

| Wang (2021) | Econometric | CASP | 8 | High |

| Liu et al. (2023) | Innovation model | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Chang (2023) | Econometric + descriptive | CASP | 8 | High |

| Cao et al. (2020) | Text mining | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Xu and Zweifel (2020) | Delphi + AHP | AMSTAR2 | 8 | High |

| Braun and Schreiber (2017) | Survey | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Cosma and Rimo (2024) | Conceptual | AMSTAR2 | 6 | Medium |

| Holland and Kavuri (2024) | Comparative analysis | AMSTAR2 | 7 | Medium–High |

| Visagamurthy (2025) | Conceptual | AMSTAR2 | 5 | Medium–Low |

| Chatzara (2020) | Conceptual | AMSTAR2 | 6 | Medium |

| Mueller (2018) | Industry mapping | CASP | 6 | Medium |

| Holliday (2019) | Analytical | CASP | 7 | Medium–High |

| Murad (2023) | Survey | CASP | 8 | High |

Appendix B. Detailed Search Strategies Used Across Databases

This appendix provides the exact search phrases and Boolean combinations used for identifying eligible studies across all databases. Keyword and subject-heading searches were executed and adapted to each database’s syntax.

- 1. Core Search Terms and Phrases (Applied Across All Databases)

The search strategy utilized the following key terms and phrases:

- “Insurtech”;

- “Insurance technology”;

- “Digital insurance”;

- “Mobile insurance”;

- “Financial inclusion”;

- “Insurance inclusion”;

- “Insurance access”;

- “Microinsurance”;

- “Insurtech development”;

- “Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”;

- “Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”.

Keyword and subject-heading searches were executed across all databases and combined using the Boolean operators “OR” (within concept groups) and “AND” (between concept groups) to refine results.

- 1.1. Boolean Search Structure (All Databases)

Across all databases, the following general Boolean logic was applied:

Insurtech-related terms (combined with OR):

“Insurtech” OR

“Insurance technology” OR

“Digital insurance” OR

“Mobile insurance” OR

“Insurtech development”.

Inclusion-related terms (combined with OR):

“Financial inclusion” OR

“Insurance inclusion” OR

“Insurance access” OR

“Microinsurance” OR

“Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries” OR

“Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”.

Final Boolean Combination (Insurtech AND Inclusion Concepts):

(“Insurtech” OR “Insurance technology” OR “Digital insurance”

OR “Mobile insurance” OR “Insurtech development”)

AND

(“Financial inclusion” OR “Insurance inclusion” OR “Insurance access”

OR “Microinsurance” OR “Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”

OR “Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”)

This structure was adapted slightly per database depending on truncation rules and advanced search options.

- 1.2. Database-Specific Application

Web of Science

Search applied in “Topic” field (TS=):

TS = (“Insurtech” OR “Insurance technology” OR “Digital insurance”

OR “Mobile insurance” OR “Insurtech development”)

AND

TS = (“Financial inclusion” OR “Insurance inclusion” OR “Insurance access”

OR “Microinsurance” OR “Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”

OR “Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”)

Emerald Insight/Taylor & Francis/SpringerLink/Wiley

Search adapted to platform syntax:

(“Insurtech” OR “Insurance technology” OR “Digital insurance”

OR “Mobile insurance” OR “Insurtech development”)

AND

(“Financial inclusion” OR “Insurance inclusion” OR “Insurance access”

OR “Microinsurance” OR “Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”

OR “Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”)

Google Scholar

Due to platform limitations, searches were executed in multiple combinations:

Primary searches

Insurtech “insurance inclusion”;

Insurtech “financial inclusion”;

“Digital insurance” “insurance access”;

“Mobile insurance” microinsurance.

Secondary searches

“Insurtech development”/“financial inclusion”;

“Insurance inclusion in developing and developed countries”;

“Link between insurance inclusion and Insurtech”.

Manual filtering ensured only empirical and relevant studies were retained.

- 1.3. Manual Reference Screening

Backward and forward reference checking of all included articles resulted in three additional eligible studies, improving coverage and minimizing reporting bias.

- 1.4. Search Timeline

All database searches were conducted and last updated on 15 October 2024.

No date limits were imposed.

References

- Abdallah-Ou-Moussa, S., Wynn, M., Kharbouch, O., El Aoufi, S., & Rouaine, Z. (2024). Technology innovation and social and behavioral commitment: A case study of digital transformation in the Moroccan insurance industry. Big Data and Cognitive Computing, 9(2), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, E. I., & Nwankwo, S. N. (2020). Bancassurance in Africa: Avenue for insurance inclusion. Business Management and Entrepreneurship Academic Journal, 2(9), 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Alt, R., Beck, R., & Smits, M. T. (2018). FinTech and the transformation of the financial industry. Electronic Markets, 28(3), 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C., He, X., & Zhang, L. (2023). The coordinated impacts of agricultural insurance and digital financial inclusion on agricultural output: Evidence from China. Heliyon, 9(2), e13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arner, D. W., Buckley, R. P., Zetzsche, D. A., & Veidt, R. (2020). Sustainability, FinTech and financial inclusion. European Business Organization Law Review, 21(1), 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakko, M., & Kattari, S. K. (2021). Differential access to transgender inclusive insurance and healthcare in the United States: Challenges to health across the life course. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 33(1), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W., Ge, T., Ji, Y., & Wang, X. (2023). How is Fintech reshaping the traditional financial markets? New evidence from InsurTech and insurance sectors in China. China Economic Review, 80, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittini, J. S., Rambaud, S. C., Pascual, J. L., & Moro-Visconti, R. (2022). Business models and sustainability plans in the FinTech, InsurTech, and PropTech industry: Evidence from Spain. Sustainability, 14(19), 12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A., & Schreiber, F. (2017). The current InsurTech landscape: Business models and disruptive potential. No. 62. I. VW HSG Schriftenreihe. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S., Lyu, H., & Xu, X. (2020). InsurTech development: Evidence from Chinese media reports. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, V. Y. L. (2023). Do InsurTech startups disrupt the insurance industry? Finance Research Letters, 57, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzara, V. (2020). FinTech, InsurTech, and the regulators. AIDA Europe Research Series on Insurance Law and Regulation, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., & Rimo, G. (2024). Redefining insurance through technology: Achievements and perspectives in insurtech. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 198, 123112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefano, G., Loh, I., Koserski, J., de T’Serclaes, J.-W., Bohrmann, J., Schreiber, T., Ng, G., & Lebefromm, R. (2023, May 22). InsurTech’s hot streak has ended. What’s next? Boston Consulting Group. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/navigating-the-insurtech-funding-decline (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Ediagbonya, V., & Tioluwani, C. (2023). The role of fintech in driving financial inclusion in developing and emerging markets: Issues, challenges and prospects. Technological Sustainability, 2(1), 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FT Partners. (2024). Fintech in Africa: InsurTech trends. Network International. Available online: https://investors.networkinternational.ae/media/1410/ft-partners-research-fintech-in-africa.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Gabor, D., & Brooks, S. (2017). The digital revolution in financial inclusion: International development in the fintech era. New Political Economy, 22(4), 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C. P., & Kavuri, A. S. (2024). Insurtech strategies: A comparison of incumbent insurance firms with new entrants. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice, 50(1), 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, S. (2019). How insurtech can close the protection gap in emerging markets. International Finance Corporation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvey, S. S., Osei, D. B., & Alagidede, I. P. (2023). Insurance penetration and inclusive growth in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from panel linear and nonlinear analysis. International Economic Journal, 37, 618–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. (2023). Measuring digital development: The ICT development index 2023. Available online: https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/D-IND-ICT_MDD-2023-2-R1-PDF-E.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kiwanuka, A., & Sibindi, A. B. (2024). Digital literacy, Insurtech adoption and Insurance inclusion in Uganda. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Ye, S., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, L. (2023). Research on InsurTech and the technology innovation level of insurance enterprises. Sustainability, 15(11), 8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamta. (2022). An analysis of insurance penetration and insurance density in India. Asian Journal of Multidimensional Research, 11(6), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B., & Sivaraman, S. (2021). Financial sector development and life insurance inclusion in India: An ARDL bounds testing approach. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(4), 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P. J. (2022). Fintech and financial inclusion in Southeast Asia and India. Asian Economic Policy Review, 17(2), 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. (2018). InsurTech rising: A profile of the InsurTech landscape (Vol. 10). Milken Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, I. F. A. (2023). Measuring the impact of electronic insurance service quality on profitability of Saudi insurance companies. Journal of Financial and Commercial Studies, 33(1), 610–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechyporuk, L. V. (2018). Financial inclusion in the context of insurance services. Financial and Credit Activity: Problems of Theory and Practice, 3(26), 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippon, T. (2019). On fintech and financial inclusion. No. w26330. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., & Roen, K. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Methods Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Re, G. (2023). Global InsurTech report. Available online: https://www.ajg.com/gallagherre/-/media/files/gallagher/gallagherre/global-insurtech-report-q1-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Sadayan, S. M. K. (2023). Insurance inclusion index: A two-dimensional measurement of international insurance inclusiveness. Journal of Insurance and Financial Management, 7(4), 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M., & Arshed, N. (2022). Revolutionizing insurance sector in India: A case of blockchain adoption challenges. International Journal of Contemporary Economics and Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 300–324. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M., Arshed, N., & Zhang, H. (2022). The adaptation of Internet of Things in the Indian insurance industry—Reviewing the challenges and potential solutions. Electronics, 11(3), 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaramuthukumar, S., & Alamelu, K. (2011). Insurance inclusion index: A state-wise analysis in India. IUP Journal of Risk & Insurance, 8(2), 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Senyo, P. K., & Osabutey, E. L. C. (2020). Unearthing antecedents to financial inclusion through FinTech innovations. Technovation, 98, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibindi, A. B. (2022). Information and communication technology adoption and life insurance market development: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(12), 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimala, B., & Alamelu, K. (2018). Insurance penetration and insurance density in India—An Analysis. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews (IJRAR), 5(4), 229–236. Available online: https://www.ijrar.com/upload_issue/ijrar_issue_20542543.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Visagamurthy, G. (2025). Digitizing trust: Ethical dimensions of InsurTech in the era of financial inclusion. Journal of Computer Science and Technology Studies, 7(5), 1007–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. (2021). The impact of insurtech on Chinese insurance industry. Procedia Computer Science, 187(2019), 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilamowicz, A. (2019). The great FinTech disruption: InsurTech. Banking & Finance Law Review, 34(2), 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., & Zweifel, P. (2020). A framework for the evaluation of InsurTech. Risk Management and Insurance Review, 23(4), 305–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., & Su, Y. (2022). Inclusive insurance, income distribution, and inclusive growth. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 890507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, A., & Kalia, P. (2022). Emerging technologies in insurance sector: Evidence from scientific literature. In Big data: A game changer for insurance industry (pp. 43–63). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.