Abstract

This paper compares actively managed bond vs. equity mutual fund performance using modified False Discovery Rate () and percent simulated t(α) < Actual t(α). Bond funds are more likely to outperform than equity funds: (%Sim < Act) shows 33.9% (30.0%) of bond funds generate positive t(α) on net excess returns vs. 1.8% (0.0%) for equity funds. shows percent simulated t(α) < Actual t(α)results are sensitive to Type II error. Bond fund outperformance is associated with long-term holdings, and corporate bond fund excess returns tend to decline with fund size.

JEL Classification:

G1; G11

1. Introduction

The extent to which actively managed bond vs. equity mutual funds add value to investors, i.e., on a returns net of expenses basis, is largely unresolved in the finance literature. One the one hand, some evidence suggests bond funds lack investor return contribution when return contribution is defined as precision-adjusted returns (t-statistic of alpha, denoted as t(α)) on a net of expenses basis. Some find US bond mutual funds generate negative precision-adjusted returns (e.g., Blake et al., 1993; Elton et al., 1995). Ferson et al. (2006) show government bond funds underperform indexes, though negative performance diminishes after adjustments are made for the stochastic term structure of interest rates. Moneta (2015) observes bond funds cover costs on a gross returns but not net of expenses returns basis. On the other hand, other evidence shows most equity funds fail to generate excess returns for investors net of expenses (e.g., Fama & French, 2010). Barras et al. (2010) show fund managers are 0.6% skilled (alpha > 0), 75.4% zero-alpha (alpha = 0), and 24.0% unskilled (alpha < 0). Harvey and Liu (2020) show Fama and French (2010) approach results for equity funds exhibit high Type II errors, reducing test power to identify outperforming funds.1 However, the literature is currently silent on the relative performance among bond vs. equity funds after separating mutual funds into outperforming, zero-alpha, and underperforming funds under the False Discovery Rate (FDR) methodology framework.

This paper compares actively managed bond vs. equity mutual fund performance using precision-adjusted returns t(α) on a net of expenses basis as our measure of fund performance, supplemented with FDR statistics proposed by Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004). First, it reports evidence obtained by applying FDR methodology to compute (conventional FDR-adjusted p-value) as a baseline statistic, then modify the p-value simulation process in computation generating adjusted (we call this ) to mitigate low signal-to-noise bias in (Huang et al., 2025a). Following Barras et al. (2010), we break funds into outperforming, zero-alpha, and underperforming funds. Using Huang et al. (2025a)’s modified False Discovery Rate (), we find 33.9% of bond funds generate positive t(α) on net excess returns vs. 1.8% for equity funds. Using Fama and French (2010)’s percent simulated t(α) < Actual t(α) (hereafter referred to as %Sim < Act), 30.0% of bond funds generate positive t(α) on net excess returns vs. 0.0% for equity funds. Second, this paper corroborates Harvey and Liu’s (2020) prediction that %Sim < Act will be prone to Type II errors (i.e., failure to reject the null of no return contribution when the null is false) resulting in mis-discovery of outperforming and underperforming funds. However, imposing a standard 5–95% (10–90%) confidence level threshold on t(α) corrects the propensity of Type II errors, and %Sim < Act yields inferences generally consistent with FDR adjusted probabilities. Third, this paper documents decreasing returns to fund size among corporate bond funds, consistent with Berk and Green (2004) and Huang et al. (2025a). We test our results using different model specifications to mitigate potential bias in model-based measurements. Focusing on corporate bond mutual funds, our comparison of bond vs. equity mutual funds under the FDR and Fama and French (2010) frameworks builds materially on our understanding of relative excess performance in the literature.

In this paper, we use t(α) on a net of expenses basis, rather than alpha used in much of the literature, as a performance measurement to rank funds to control for risk-taking variation across funds. For bond mutual funds, t(α) is estimated using the Fama and French (1993) 5-factor bond return model and the Huang et al. (2025b) 12-factor bond return model motivated by Chen et al. (2010). For the statistical significance of performance measurement, we supplement traditional p-values with FDR q-values to control for the expected proportion of false positives (Type I error or false discovery, a prominent problem in multiple hypothesis testing) among tests. Furthermore, to mitigate low signal-to-noise bias in FDR that tends to underestimate the proportion of outperforming funds (Type II error, or mis-discovery), as discussed in Andrikogiannopoulou and Papakonstantinou (2019), we modify the simulation process in the traditional q-value () calculation. Rather than simulate p-values of the original dataset as in the process of calculation, we simulate the original dataset 10,000 times to recompute p-values for each simulation run and denote the modified as following Huang et al. (2025a). Similar to Fama and French (2010), our simulation runs are random samples with replacement of our sample months, in our case drawn from the 216 months between January 1999 and December 2016, rather than simulate by individual funds as in Kosowski et al. (2006). We also use the same simulation-by-month procedure to compute Fama and French %Sim < Act, which compares the t(α) of 10,000 simulated demean samples (subtract fund’s alpha from its monthly returns) with that of the actual sample.

Distributions of re-estimated t(α) and -values from bootstrap samples are informative. For our bond mutual fund sample, the percentage of outperforming (zero-alpha) funds is higher (lower) on conditional 12-factor benchmark return models than 5-factor models; therefore, our subsequent analysis focuses on the 12-factor models even though results from 5- and 12-factor models are robust.

Although our sample of actively managed bond mutual funds is predominantly zero-alpha, a significant percentage of funds outperform. This result is consistent with a competitive Berk and Green (2004) equilibrium where investors cannot at low cost accurately detect outperforming funds, resulting in these funds being underfunded. As Gârleanu and Pedersen (2018) reason, markets for assets and asset management will be inefficiently efficient when information acquisition by outperforming funds and the search for outperformance by investors are costly.

For all actively managed bond mutual funds, using a conventional 5-factor benchmark model, the percentage of zero-alpha bond funds is 64.5%, and outperforming (positive-alpha) is 33.9%. For the 5-factor model, FDR q-values and %Sim < Act show bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform the benchmark. For economic significance: average annualized alpha for funds classified as outperforming using the 5-factor model is 1.92%. For a conditional 12-factor return model that controls for time-varying risk and reduced residual errors, we show 55.8% of bond funds are zero-alpha, and 41.6% outperform. For the 12-factor model, FDR q-values and %Sim < Act show bond funds at the 80th percentile and above outperform the benchmark. For economic significance: average annualized alpha for funds classified as outperforming using the 12-factor model is 2.91%. As expected, no index bond funds significantly under- or over-perform benchmarks. In contrast, equity funds generate only positive excess alpha of 1.8% using conventional 4-factor, or 2.6% using 8-factor, net excess returns models (Barras et al., 2010, Equations (9) and (10)). Fama and French (2010)-style precision-adjusted alpha t(α) results are qualitatively similar.

Performance of actively managed corporate bond funds is better than for governments, consistent with higher information costs on corporate compared to government bonds. Using the 12-factor return model, the percentage of zero-alpha and outperforming bond funds is 43.5% and 55.7% on corporates, compared to 72.7% and 23.8% on governments. and %Sim < Act show corporate bond mutual funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform using either the 5- or 12-factor model, whereas government bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform using the 5-factor model, but when using the 12-factor model only the 90th percentile and above outperform. In terms of economic significance, the average annualized alpha for outperforming corporate bond funds is 2.59% using the 5-factor model and 3.25% using the 12-factor model for Top 30% funds. For government bond funds, the corresponding figures are 1.51% for Top 30% funds and 2.83% for Top 10% funds.

When funds are underperforming, %Sim < Act is less likely to attribute luck to outperformance but more likely to attribute outperformance to luck when funds actually are outperforming.2 We find that when funds are underperforming (t(α) averaged across funds is negative), %Sim < Act attributes underperformance to unlucky zero-alpha funds. When funds are outperforming (t(α) averaged across funds is positive), %Sim < Act attributes outperformance to lucky zero-alpha funds. We show that imposing a standard 5–95% (10–90%) confidence level threshold on t(α) corrects for the propensity of Type II errors to occur, and %Sim < Act yields inferences consistent with and (conventional FDR and Huang et al. (2025a) modified FDR adjusted probabilities).

As predicted in Berk and Green (2004) and corroborated by Huang et al. (2025a), we find diminishing returns to scale in bond mutual funds. The percentages of zero-alpha and outperforming funds are 49.5% and 49.6% in small bond funds, where small funds are USD 5M-250M in assets under management (AUM). This compares to 57.1% and 35.2% in mid-size bond funds, where mid-size bond funds are USD 250M–750M in AUM. In large bond funds, where large funds are over USD 750M in AUM, variation in performance is more extreme. Among large bond funds, the percentage of zero-alpha funds of 28.3% is comparatively low, whereas percentages of underperforming and outperforming funds are 35.7% and 36.0%. FDR adjusted probabilities show small bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform benchmarks, for mid-size and large bond funds at the 80th percentile and above.

High turnover reduces bond fund performance, as shown in the Supplementary Materials, consistent with relatively high spreads and illiquidity that characterize bond markets compared to those of equities. The percentage of zero-alpha bond funds rises to 76.2% from 55.8%, and the percentage of outperforming bond funds declines to 23.8% from 41.6%. and %Sim < Act show actively managed bond mutual funds at the 80th percentile and above are outperforming. We also show in Supplementary Materials that outperformance is more evident in the long term. Over short three-year horizons, the percentage of zero-alpha bond funds is 93.6%, and outperforming bond funds 3.2%. and %Sim < Act show weak evidence bond funds outperform their benchmarks at the 98th percentile and above. The return contribution of active bond fund management comes primarily from long holding periods when time-varying risk is considered.

In the process, this paper makes three material contributions to the literature. It is the first to compare bond vs. equity mutual fund performance using an FDR approach (as in Huang et al., 2025a), supplementing Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act. Second, it is the first to document that for both bond and equity mutual fund managers Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act results are prone to Type II error, consistent with predictions in Harvey and Liu (2020) concerning equity funds. Third, it is the first to compare the relation between fund manager performance vs. fund size (measured as AUM) for corporate bond funds using t(α) supplemented with FDR statistics.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes sample selection, including actively managed bond and equity funds, and indexed bond and equity funds. Section 3 explains methodology. Section 4 describes empirical results. Section 5 compares actively managed government vs. corporate bond funds, and the relation between corporate bond fund performance and fund size. Section 6 reports results of additional robustness tests. Section 7 discusses economic significance. Section 8 concludes.

2. Sample Selection

2.1. Bond Mutual Fund

2.1.1. Actively Managed Bond Mutual Fund Sample

To construct our actively managed bond mutual fund sample, we first download US open-end actively managed domestic bond mutual fund monthly returns from the CRSP Survivor-Bias-Free Mutual Fund Database. Our sample period spans the 216 months between January 1999 and December 2016. As in Kosowski et al. (2006) and French (2008), we combine mutual fund-month observations with more than one share class into a single consolidated mutual fund-month observation using the variable CRSP_CL_GRP available from August 1998. The value weights used to consolidate fund monthly returns are based on the proportion of each share-class to total net assets at month start. Monthly gross returns are monthly net returns (CRSP reported monthly returns) plus the ratio of the annual expense ratio divided by 12. Funds included in the sample have an AUM of more than USD 5 million and at least 12 observations spanning at least 5 years. This mitigates potential mutual fund incubation bias associated with too many funds with short histories (Evans, 2010). Excluded funds are on average 44% smaller in size. We stratify funds by AUM into three categories: small (USD 5–250 million AUM), mid-size (USD 250–750 million AUM), and large (AUM > USD 750 million). AUM is always expressed in 2006 constant dollars. Detailed data selection procedures are in Supplementary Materials S1.1.

Our final bond test sample includes 571 US open-end actively managed domestic bond mutual funds. Table 1 shows the number of observations, average AUM, and equal and value weighted (EW and VW) gross and net returns. From the beginning to the end of our sample period, the number of government bond mutual funds rises by 18%, and corporate bond mutual funds declines by 24%, but the total overall number of bond mutual funds (from 316 to 319) remains almost unchanged. Average AUM grows from USD 671 million to USD 1.081 billion, representing a 61% increase over the sample period. As actively managed bond mutual funds increase in size, the differences between gross and net returns decrease across our sample of bond funds, consistent with diminishing returns to scale (Berk & Green, 2004).

Table 1.

Number, Average Assets Under Management, Equal and Value Weighted Returns on Actively Managed Bond Mutual Funds. This table reports number, average assets under management (AUM), equal-weighted and value-weighted gross and net monthly returns on US open-end actively managed bond mutual funds over the sample period January 1999 to December 2016. Different classes of the same fund are consolidated by AUM using the Center for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP) Mutual Funds Database variable CRSP_CL_GRP. Funds with at least USD 5 million in AUM (in 2006 dollars) and more than twelve observations over five or more years are included. Net excess returns are approximate percent returns received by investors, defined as monthly net excess returns minus lagged one-month T-Bill rate. Net excess returns are returns net of expenses and 12b fees. Gross returns are monthly net excess returns plus annual expense ratio/12. Gross and net excess returns are annualized and expressed as percentages. Panel A reports results for all bond mutual funds, Panel B for government bond mutual funds, and Panel C for corporate bond mutual funds.

2.1.2. Index Bond Mutual Fund Sample

To construct a passively managed index bond mutual fund control sample, we start with the CRSP Survivor-Bias-Free Mutual Fund Database and Morningstar Direct. We use the index flag, Pure Index Fund (D), to identify index bond mutual funds starting March 2003. A pure index fund replicates its benchmark by holding nearly every security in the index, with each security assigned the same value weight as in the index to match the performance of a recognized securities market index. Pure index bond indexes are imperfect instruments because they are imperfectly investible due to bond issue illiquidity, especially among corporates, but it is the best proxy available for a passively managed bond fund control sample. Additional details on our selection procedure are in Supplementary Materials S1.2.

2.2. Equity Mutual Fund

2.2.1. Actively Managed Equity Mutual Fund Sample

The actively managed equity mutual fund sample consists of 3986 actively managed US open-end domestic equity mutual funds between January 1999 and December 2016. It has 485,543 fund-month observations. Monthly returns are obtained from the survivor bias free CRSP database. Funds with at least 60 months of observations and monthly total net assets exceeding USD 5 million in 2006 US dollars are included. Monthly fund-class net returns are consolidated, with monthly total net asset weights, into fund family returns. As with bond mutual funds, we subtract the lagged one month 30-day T-bill rate from consolidated monthly net returns. The number of actively managed equity mutual funds in 1999 is 323, and ranges from 1818 to 2495 between 2000 and 2016. On average, there are 2291 actively managed equity mutual funds each year.

2.2.2. Index Equity Mutual Fund Sample

Using the Pure Index Fund (D) flag as an identifier, the index equity mutual fund sample consists of 605 index US open-end domestic equity mutual funds that exist between January 2003 and December 2016, with 67,242 fund-month observations. The number of index equity mutual funds in 2003 is 18 and ranges from 190 to 542 between 2004 and 2016. On average, there are 407 index equity mutual funds each year.

3. Methodology

3.1. Performance Measurement

In this study, rather than use alpha estimated from a model, we use the t-statistic of alpha t(α), so-called precision-adjusted returns, as our performance measurement. This controls for differences in risk-taking behavior of fund managers, making comparisons more informative. Fund performance is evaluated using t(α) estimated from the benchmark and conditional models described below, and funds are ranked by t(α) from low to high.

3.1.1. Benchmark Models for Estimating Bond Mutual Fund t(α)

We employ a 5-factor model proposed by Fama and French (1993) as our baseline asset pricing model to determine whether actively managed bond mutual funds create significant alpha on returns net of expenses:

In Equation (1), Ri,t denotes monthly bond fund returns for fund i at time t, and RF is the one-month T-Bill rate. Denoting the value-weighted CRSP monthly return minus lagged one-month T-Bill rate as MKTRF, RMO is an orthogonal linear projection of MKTRF on SMB and HML as well as TERM and DEF. SMB is the difference in monthly returns between stocks with market capitalization above and below the NYSE median. HML is the difference in monthly returns between stocks with book-to-market equity ratios in the top and bottom 30% of the NYSE. TERM is the difference in monthly returns between long-term treasuries and the one-month lag T-Bill rate. DEF is the difference in monthly returns between corporate and long-term treasury bonds.

To account for time variation in asset pricing factors, we also consider factors proposed in Chen et al. (2010). Following Huang et al. (2025b), we implement a LAR LASSO (Tibshirani, 1996; Efron et al., 2004) procedure to identify the best fitting parsimonious model given our large number of potential regressors to generate our final conditional 12-factor benchmark return model:

In Equation (2), MKTLIQ and EQVOL proxy for economic shocks to discount rates from changes in liquidity and equity risks. PRC/DIV proxies for economic shocks to cash flow and dividends, it is an equity market valuation factor measured as the one-month lag demeaned price/dividend ratio for the CRSP value-weighted index. MKTLIQ, is the difference between 3-month non-financial commercial paper rates and 3-month Treasury yields. EQVOL is the one-month lag demeaned CBOE implied volatility index (VIX-OEX). Timing variables are demeaned, and lagged values interacted with TERM and DEF. Coefficients on interaction terms reflect the effect on expected returns from predictive values of demeaned timing variables used to forecast following month TERM and DEF.

In Equations (1) and (2), we use the baseline and conditional benchmark model precision-adjusted alphas to proxy for fund performance, where and are the estimated alpha and standard deviation of alpha for fund . Compared to alpha, t(α) controls for differences in residual variance and the number of months funds are in the sample period. Supplementary Materials S2 contains further discussion of our 5- and 12-factor models specifications.

The 12-factor model demonstrates strong explanatory power for our application. We construct momentum portfolios following the methodology of Jegadeesh and Titman (1993), employing a “60-month formation, skip 1 month, 60-month holding” strategy to rebalance portfolios ranked by t(α). For a given month t, we use corporate bond mutual fund returns from months t − 60 to t − 1 to estimate the 12-factor model’s t(α) and rank the funds into quintiles in descending order of t(α). We then skip month t and hold the portfolios from t + 1 to t + 60, rebalancing on a rolling monthly basis. The exclusion of the most recent month between portfolio formation and holding is particularly important for investments in less liquid assets (e.g., fixed income securities). This gap helps reduce the influence of microstructure effects—such as price staleness, bid-ask bounce, and limited liquidity—which are especially pronounced over short horizons. Additionally, short-term reversals driven by investor overreaction or transient flows may distort performance signals in the most recent month. By skipping this period, we aim to construct more stable and actionable fund rankings (Jegadeesh & Titman, 1993; Chordia et al., 2001).

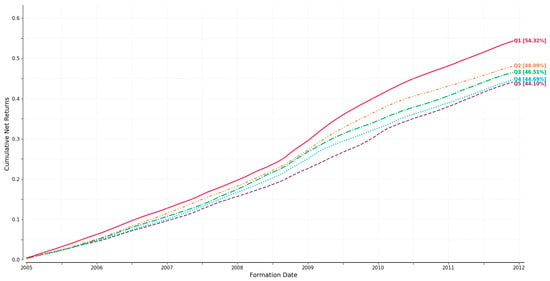

Using this approach, the initial formation occurs in January 2005 and the final one in December 2011. Over this period, the top quintile portfolio ranked by t(α) achieves a cumulative return of 54.32%, while the bottom quintile earns 44.10%. The corresponding annualized returns are 6.39% and 5.36%, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 1, the top quintile portfolio consistently outperforms the bottom quintile over the holding period.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Net Returns of t(α)-Ranked Portfolios by Quintile Based on the 12-Factor Model for Corporate Bond Mutal Funds. We construct momentum portfolios following the methodology of Jegadeesh and Titman (1993), employing a “60-month formation, skip 1 month, 60-month holding” strategy to rebalance portfolios ranked by t(α). For a given month t, we use corporate bond mutual fund returns from months t − 60 to t − 1 to estimate the 12-factor model’s t(α) and rank funds into quintiles in descending order of t(α). We then skip month t and hold the portfolios from t + 1 to t + 60, rebalancing on a rolling monthly basis. Using this approach, the initial formation occurs in January 2005 and the final one in December 2011. Over this period, the top quintile portfolio ranked by t(α) achieves a cumulative return of 54.32%, while the bottom quintile earns 44.10%. The corresponding annualized returns are 6.39% and 5.36%, respectively. Q1–Q5 at the end of the lines represent quintile portfolios, and the numbers in square brackets are the cumulative net returns at the end of the investment horizon.

3.1.2. Benchmark Models for Estimating Equity Mutual Fund t(α)

To estimate t(α) for equity mutual funds, we use the unconditional baseline 4-factor and conditional 8-factor equity benchmark models in Barras et al. (2010, Equations (9) and (10)):

Equation (3) is the unconditional baseline 4-factor model proposed by Carhart (1997), where R denotes monthly bond fund returns, and RF is the one-month T-Bill rate. MKTRF is the monthly excess return on the CRSP value-weighted market portfolio; and SMB, HML and MOM are the factor-mimicking portfolios for size, book-to-market, and momentum from Kenneth French’s website:

Equation (4) is the conditional 8-factor model (Ferson & Schadt, 1996), where B’ is the J × 1 vector of coefficients and the J × 1 vector of end of month demeaned predictive variables. The four predictive variables include the 30-day T-bill rate; the dividend yield of CRSP value-weighted NYSE/Amex stock index; the default spread (yield difference between Moody’s Baa-rated and Aaa-rated corporate bonds); and the term spread (difference between 10-year treasuries and 3-month T-bills rates).

3.2. Statistical Significance

In terms of statistical significance, for the t(α) estimated we provide traditional p-values, conventional Storey FDR-adjusted p-values (denoted as ) and Huang et al. (2025a) modified FDR-adjusted p-values (denoted as ). Detailed discussions on the FDR methodology and comparison of the and are available in Supplementary Materials S3.

In hypothesis testing in this paper, the null is that fund managers neither create nor destroy value (alpha = 0). A p-value, say 5%, provides statistically significant evidence to reject the null if it is less than the “acceptable” Type I error (or so-called false positive) rate represented as the significant level predetermined by researchers. The error involves rejection of the null when it is true, leading to a wrong conclusion that fund managers create (alpha > 0) or destroy (alpha < 0) value when the truth is that they generate zero-alpha. Those who are falsely labeled as “managers who create value” are simply “lucky managers,” whereas “managers who destroy value” are simply “unlucky.” The “acceptable” Type I error rate in a single test becomes a prominent problem in multiple hypothesis testing where larger numbers of statistical hypotheses are tested simultaneously because the rate of false positives significantly increases as the number of tests increase, leading to many false discoveries by chance. Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute to control for Type I error. In the process of calculation, one of the key inputs, (overall proportion of null p-value, or zero-alpha funds in this paper) is determined by bootstrapping 10,000 times the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset to obtain the minimum mean squared error, the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as , and the corresponding is denoted as . To mitigate the low signal-to-noise bias in , especially for small samples, we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , where most computation steps remain the same. However, to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we first bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and re-estimate p-values for each simulated sample. The threshold p-value associated with is denoted as , and the corresponding is denoted as . For the sample bootstrapping, we follow the Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach. We bootstrap actual fund-month returns to synthesize the latent data generating process of our sample of bond fund-month returns and reduce potential FDR bias from imprecise estimates of t(α) on actively managed bond funds with low signal-to-noise returns. In the FDR approach, the distribution of -values associated with t(α) plays an important role in determining the percentage of funds that are zero-alpha. Supplementary Materials S3 reports the MSE optimized threshold values of using 10,000 bootstraps of an vector of -values on t(α) estimated on actual fund-month net excess returns (Storey, 2002; Storey et al., 2004), as well as distributions of an vector of -values from re-estimated t(α) on 10,000 simulated bootstrap samples of actual fund-month net excess returns (Huang et al., 2025a). The goal of selection via MSE is to balance bias against variance. However, if the simulated p-value (corresponding t-value) distribution is noisy, the computed MSE will be noisy. The jagged appearance of the distribution following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004) signals high simulation variance (Monte Carlo noise). By contrast, the Huang et al. (2025a) method injects fresh randomness in each replicate (through resampling raw returns), effectively smoothing out peculiar features, making the optimal easier to identify.

3.3. Outperforming, Zero-Alpha and Underperforming

As a supplement to t(α) ranking, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (denoted as ), zero-alpha (denoted as ) and underperforming funds (denoted as ). The byproduct of FDR (and ) is estimated , which is the proportion of zero-alpha funds estimated in the sample. Using the estimated , Barras et al. (2010) take one step further to compute the proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. In their practice, a threshold significant level is identified when it minimizes the mean squared error. When from the computation procedure (where p-values are bootstrapped 10,000 times to obtain ) is used, we bootstrap the t(α) estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold significant level , then compute (denoted as ) and (denoted as , and the results are reported in the bottom section of column. When from the computation procedure (where the actual dataset is bootstrapped 10,000 times and p-values are re-estimated for each simulation run to obtain ) is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times. t(α)s are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold significance level . We then compute (denoted as ) and (denoted as ), and report results in the bottom section of the column. As discussed in Barras et al. (2010), the threshold significance level plays a vital role in controlling for Type II error, i.e., failing to identify the true outperforming and underperforming funds. Also reported as a separate section below %Sim < Act column are , and , where λ and γ are assigned without the minimizing mean squared error bootstrap procedure. Detailed computation steps and different , , , and are reported in Supplementary Materials S3.

3.4. Fama-French Simulation and %Sim < Act

We also compute Fama-French %Sim < Act via 10,000 simulations. First, the estimated alpha is removed from each bond mutual fund’s monthly return to generate the mean-adjusted return sample. Next, a simulation run is a random sample of 216 months drawn with replacement from the period of January 1999 to December 2016. In each simulation run, a bootstrapped alpha and -statistic for each fund is re-estimated. The actual t(α) at each percentile is compared to 10,000 simulated t(α) of the percentile, and the percentage of simulated less than the actual (%Sim < Act) is calculated and reported. Also reported is the mean of simulated t(α) at each percentile. In Supplementary Materials S4, we provide a robustness check for the simulation in terms of true alpha uncertainty, and results show that the simulation has explanatory power for our samples.

3.5. Summary

In summary, fund performance is evaluated in three steps. First, funds are ranked by percentile (Pct) on t(α). Column “Actual” reports t(α) of different models. Column “-value” reports standard p-values of estimated t(α). Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute positive FDR-adjusted probability , which adjusts the probability of a fund at percentile rank for the false positives (lucky) and negatives (unlucky) of zero-alpha funds. Results are shown in column “.” In the calculation, (overall proportion of zero-alpha funds) is determined by 10,000 bootstraps of the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset that minimize mean squared error (the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as ). To mitigate potential low signal-to-noise bias in , we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , which is computed analogously, except to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times to re-estimate p-values (the threshold p-value is denoted as ). The Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach is used for simulation.

Second, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (), zero-alpha () and underperforming funds (). We use from (and ) and a threshold significance level γ to estimate proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. A threshold significant level is identified when the mean squared error is minimized. When from the is used, we bootstrap t(α)s estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. When from the is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and t(α)s are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. Superscript ○ on , or is associated with optimized or , and without superscript, is calculated as a residual, . and are based on optimized or but fixed at -values of 0.05 and 0.10 Also reported are and as well as and using fixed and parameters on estimated t(α) and -values based on actual fund-month net excess returns.

Third, we compute Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act. Column “Sim” reports average t(α) from 10,000 simulated samples of demeaned fund-month net excess returns, and column “%Sim < Act” the percent of 10,000 simulations with lower t(α) than actual.

We base our findings primarily on the 12-factor (8-factor) model for bond (equity) mutual funds and the statistics reported in column , while the 5-factor (4-factor) model and additional statistics provide corroborating evidence. We consider an actual t(α) is statistically significant when the p-value is 10% or less and is 0.20 or below.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Actively Managed vs. Index Bond Mutual Fund Results

In Table 2, active and passively managed bond funds are ranked by percentile (Pct) on precision adjusted alpha t(α)The column Actual reports t(α) estimated from time-series regressions of actual fund-month net excess returns over the sample period using unconditional baseline 5- and conditional 12-factor benchmark models. Panel A covers our sample of 571 actively managed bond mutual funds for 1999–2016, and Panel B our sample of 70 index bond mutual funds for 2010–2016.

Table 2.

Percentile Distributions of on Actively Managed and Index Bond Mutual Funds. Panel A reports results for our sample of 571 actively managed bond mutual funds 1999–2016, and Panel B for our control sample of 70 index bond mutual funds 2010–2016. Fund performance is evaluated in three steps. First, funds are ranked by percentile on . Column “Actual” reports of 5- and 12-factor models. Column “-value” reports standard p-values of estimated . Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute positive FDR-adjusted probability , which adjusts the probability of a fund at percentile rank for the false positives (lucky) and negatives (unlucky) of zero-alpha funds. Results are shown in column “.” In the calculation, (overall proportion of zero-alpha funds) is determined by 10,000 bootstraps of the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset that minimize mean squared error (the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as ). To mitigate potential low signal-to-noise bias in , we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , which is computed analogously, except to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times to re-estimate p-values (the threshold p-value is denoted as ). The Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach is used for simulation. Second, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (), zero-alpha () and underperforming funds (). We use from (and ) and threshold significance level γ to estimate proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. A threshold significant level is identified when the mean squared error is minimized. When from the is used, we bootstrap the estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. When from the is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. Superscript ○ on , or is associated with optimized or , and without superscript, is calculated as a residual, . and are based on optimized or but fixed at -values of 0.05 and 0.10. Also reported are and as well as and using fixed and parameters on estimated and -values based on actual fund-month net excess returns. Third, we compute Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act. Column “Sim” reports average from 10,000 simulated samples of demeaned fund-month net excess returns, and column “%Sim < Act” the percent of 10,000 simulations with lower than actual. Columns shaded in gray highlight Fama and French (2010) results.

When time-varying risk and residual errors matter, the baseline 5-factor benchmark model estimates t(α) imprecisely. Compared to bootstrapping t(α) and -values from estimated alphas on actual fund-month returns, bootstrap samples mitigate potential FDR bias from imprecise t(α). Supporting discussion is in Supplementary Materials S3, with a robustness check in Supplementary Materials S5.3.

In Table 2 Panel A bottom sections of columns and , the percentages of zero-alpha bond funds on the conditional 12-factor benchmark model are = 55.8%. However, the percentage of outperforming funds on the conditional 12-factor benchmark model of 41.6% is higher than of 36.9%. Further, when t(α) is imprecise, bootstrapping t(α) and -values from estimated alphas on actual fund-month returns overestimates percentages of zero-alpha and outperforming funds. and are 58.4% and 41.6% on the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model, and and of 55.8% and 36.9% on the conditional 12-factor benchmark model.

From Table 2 Panel A column , in the upper percentiles, the two-tail of 0.18 (i.e., less than or equal to 0.20, where we selected 0.20 as our FDR cut-off) on the conditional 12-factor model, and 0.13 on the 5-factor benchmark model, indicate actively managed bond mutual funds at the 70th percentile outperform. In the lower percentiles, two-tail of 0.12 on the conditional 12-factor model, and 0.20 on the baseline 5-factor benchmark model, indicate actively managed bond mutual funds at or below the 5th percentile underperform.

In Table 2 Panel A bottom section of column the estimated percentage of zero-alpha funds is 55.8% on the conditional 12-factor, and 64.5% on the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark models, after adjusting for false positives and false negatives. The percentages of underperforming actively managed bond mutual funds of 2.60% and 1.60% are small compared to the percentages of outperforming actively managed bond mutual funds of 41.6% and 33.9%. A substantial percentage of actively managed bond mutual fund managers outperform their benchmarks.

Unsurprisingly, in Table 2 Panel B, two-tail provides no evidence that index bond mutual funds overperform the conditional benchmark. In the bottom section of column , the estimated percentage of zero-alpha index bond funds, is 84.0%, and percentage of underperforming index bond funds , is 16.0%, on the conditional 12-factor benchmark model. The unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model underestimates the percentage of zero-alpha and underperforming index bond funds.

In Fama and French (2010), distributions of t(α) estimated from bootstrap samples of demeaned actual fund-month net excess returns create pseudo zero-alpha funds at each percentile. For each bond mutual fund, we use our unconditional baseline 5- and conditional 12-factor benchmark models to estimate alpha. Estimated alphas are subtracted from actual fund-month net excess returns to obtain demeaned returns. Using demeaned actual fund-month returns, a simulation run is a random sample of 216 months drawn with replacement from the January 1999 to December 2016 period.3 In each simulation run, bootstrapped t(α) for each fund is re-estimated using demeaned actual fund-month returns to produce a cross-section of bootstrapped t(α) across funds sorted into performance percentiles.

On the bottom and top halves of the percentile distribution of t(α) estimated from bootstraps of demeaned fund-month net excess returns, average simulated t(α)s are negative and positive, respectively. Under the null hypothesis that funds generate expected returns that cover all costs, true alphas on net excess returns will be zero on average. As in the FDR approach, we assume which corresponds to a critical t(α) value of and standard confidence interval of 5% to 95%. %Sim < Act is the likelihood that a negative deviation of actual from average simulated t(α) represents either an underperforming fund or an unlucky zero-alpha fund, and a positive deviation, either an outperforming fund or a lucky zero-alpha fund.

In Table 2, the Sim_ column is t(α) averaged across 1 bootstraps at each percentile. %Sim < Act column is the fraction of simulated t(α) less than actual t(α) at each percentile. The mean (median) of the cross-sectional distribution of simulated t(α) on the conditional 12- and unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark models are −0.0680 (−0.0527) and −0.0904 (−0.0807), and standard deviations are 1.264 and 1.242.

In Table 2 Panel A, the conditional 12-factor model results show that actual t(α) is positively significant (p-value less than 10%) and %Sim < Act is 99% at the 80th percentile and above, and for the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model %Sim < Act is 98% at the 70th percentile and above. Following Huang et al. (2025b), we use %Sim < Act of 80% as our cut-off value on the right tail to claim that actual funds are truly outperforming. Our results indicate that a majority of simulated zero-alpha funds at these percentiles and above are worse than actual funds, and actively managed bond funds are more likely to be outperforming than to be lucky zero-alpha funds. On the conditional 12-factor model, at or below the 5th percentile, actual t(α) is negative and significant and %Sim < Act is 43–57% at or below the 5th percentile, and for the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model actual t(α) is negative and significant and %Sim < Act is 17–50% at or below the 4th percentile. Following Huang et al. (2025b), we use %Sim < Act of 20% as our cut-off value on the left tail to claim that actual funds are truly underperforming. Evidence here shows that actively managed bond funds at these percentiles are underperforming rather than unlucky zero-alpha funds. However, q* less than 0.20 shows strong evidence that those funds truly underperform. %Sim < Act is prone to Type II errors.

Table 2 Panel A findings discussed above remain essentially unchanged when we increase to corresponding to a critical t(α) of and standard confidence interval of 10% to 90%. On the conditional 12-factor benchmark model with of , two-tailed is 0.12 (i.e., less than or equal to 0.20) and actual t(α) is negative and statistically significant (p-value less than or equal to 10%) at the 5th percentile and below. This shows that actively managed bond funds at the 5th percentile and lower underperform. Similarly, two-tailed is 0.18 and actual t(α) is positive at the 70th percentile and above, showing that actively managed bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform. On the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model with of , results are similar. Actively managed bond funds from the 5th through 70th percentiles are zero-alpha. Table 2 Panel B shows that our finding of no evidence of index bond mutual fund outperformance is robust to adjustment for .

In Supplementary Materials S4, we repeat simulations with random injections of alpha into each fund’s demeaned 5- or 12-factor benchmark returns, following Fama and French (2010). Our analysis shows that the above findings are robust to uncertainty about true alpha.

4.2. Actively Managed vs. Index Equity Mutual Fund Results

To investigate potential differences between actively managed bond vs. equity mutual funds, we also apply our analysis to monthly returns on US open-end domestic equity mutual funds and pure index equity funds. FDR bootstrap results on actively managed and index equity mutual funds are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentile Distributions of on Actively Managed and Index Equity Mutual Funds. Panel A reports results for our sample of 3986 actively managed equity mutual funds 1999–2016, and Panel B for our control sample of 605 index equity mutual funds 2003–2016. Fund performance is evaluated in three steps. First, funds are ranked by percentile on . Column “Actual” reports of 4- and 8-factor models. Column “-value” reports standard p-values of estimated . Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute positive FDR-adjusted probability , which adjusts the probability of a fund at percentile rank for the false positives (lucky) and negatives (unlucky) of zero-alpha funds. Results are shown in column “.” In the calculation, (overall proportion of zero-alpha funds) is determined by 10,000 bootstraps of the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset that minimize mean squared error (the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as ). To mitigate potential low signal-to-noise bias in , we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , which is computed analogously, except to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times to re-estimate p-values (the threshold p-value is denoted as ). The Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach is used for simulation. Second, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (), zero-alpha () and underperforming funds (). We use from (and ) and a threshold significance level γ to estimate proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. A threshold significant level is identified when the mean squared error is minimized. When from the is used, we bootstrap the estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. When from the is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. Superscript ○ on , or is associated with optimized or , and without superscript, is calculated as a residual, . and are based on optimized or but fixed at -values of 0.05 and 0.10. Also reported are and as well as and using fixed and parameters on estimated and -values based on actual fund-month net excess returns. Third, we compute Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act. Column “Sim” reports average from 10,000 simulated samples of demeaned fund-month net excess returns, and column “%Sim < Act” the percent of 10,000 simulations with lower than actual. Columns shaded in gray highlight Fama and French (2010) results.

Table 3 Panel A reports results for actively managed equity mutual funds that are generally consistent with those of Barras et al. (2010). Based on MSE optimized of 0.65 and 0.50 on distributions of -values from bootstraps of actual -values, the percentages of zero-alpha equity funds shown in column are 73.1% and 72.6% for conditional 8- and baseline 4-factor equity benchmark models. Supplementary Materials S3.3 shows that our bootstrap samples mitigate potential FDR bias from imprecise t(α), compared to bootstrapping t(α) and -values from estimated alphas on actual fund-month returns, corroborating findings in Huang et al. (2025a) for bond mutual funds. The distribution of -values from bootstraps of actual -values has attenuated peak densities and greater volatility than the distribution of -values from re-estimated t(α) on bootstraps of actual equity fund-month net excess returns. MSE optimized of 0.15 and 0.20 in Supplementary Materials Figure S6 correspond to critical t(α) of ±1.09 and ±0.84.

Table 3 Panel A two-tail and %Sim < Act confirm actively managed equity mutual funds are largely zero-alpha. Two-tail is 0.12 (less than or equal to 0.20) for the 1st through 5th percentiles when t(α) is negative and significant for the conditional 8-factor equity benchmark model. This is consistent with actively managed equity mutual funds underperforming at the 5th percentile and below. Two-tail of 0.16 with positive t(α) for the 8-factor model suggests actively managed equity funds only outperform at the 99th percentile and above. Results from the baseline 4-factor benchmark model show equity mutual funds underperform at the 10th percentile and below and only outperform at the 98th percentile and above.

Table 3 Panel A results also corroborate findings in Fama and French (2010, Table 3) concerning equity mutual funds. Using MSE optimized of 0.15 and 0.20 with a cut-off value of %Sim < Act of less than 0.20 (Huang et al., 2025b) with negative and significant t(α), we find actively managed equity mutual funds are zero-alpha or underperform on a net returns basis. %Sim < Act is 0.00 (less than our below 0.20 cut-off) with a negative and statistically significant t(α) for the conditional 8-factor model at the 10th percentile and lower, and for the baseline 4-factor benchmark model at the 20th percentile and lower. Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act shows no evidence of outperformance for either model. In contrast, in the bottom section of FDR adjustment column shows 2.6% of actively managed equity mutual funds outperform based on the conditional 8-factor benchmark model, and 1.8% based on the baseline 4-factor benchmark model. These results are consistent with the fact that Fama and French (2010) methodology can be prone to Type II error (i.e., failure to detect outperformance).

Overall, we find that there are relative differences in ability to outperform between actively managed bond vs. equity mutual funds. From Table 2 Panel A, only 41.6% of actively managed bond mutual funds outperform and 55.8% are zero-alpha, compared to Table 3 Panel A that shows only 2.6% of actively managed equity mutual funds outperform and 84.0% are zero-alpha.

5. Government vs. Corporate Bond Funds, and Corporates by Fund Size

5.1. Government vs. Corporate Bond Mutual Funds

Table 4 shows more corporate bond funds outperform than government bond funds, particularly after controlling for time-varying risk. Table 4 Panel B corporate shows that for the conditional 12-factor benchmark model, two-tail is 0.04 (less than below 0.20 cut-off) with t(α) positive and significant, consistent with actively managed corporate bond funds outperforming at the 70th percentile. Two-tail also shows outperformance for higher percentiles. %Sim < Act also shows corporate bond fund outperformance for percentiles at and above the 70th percentile. In contrast, Table 4 Panel B government two-tail shows actively managed government bond funds at the 90th percentile and above outperform, and %Sim < Act shows actively managed government bond funds outperform at the 80th percentile and above. Table 4 Panel B column bottom section shows percentages of outperforming corporate bond funds based on the conditional 12-factor benchmark model are 55.7% (, compared to only 23.8% for government bond funds.

Table 4.

Percentile Distributions of on Actively Managed Government and Corporate Bond Mutual Funds. Panel A reports results for our sample of 345 actively managed government bond mutual funds and our sample of 226 actively managed corporate bond mutual funds 1999–2016 using our baseline 5-factor model, and Panel B using our conditional 12-factor model. Fund performance is evaluated in three steps. First, funds are ranked by percentile on . Column “Actual” reports of 5- and 12-factor models. Column “-value” reports standard p-values of estimated . Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute positive FDR-adjusted probability , which adjusts the probability of a fund at percentile rank for the false positives (lucky) and negatives (unlucky) of zero-alpha funds. Results are shown in column “.” In the calculation, (overall proportion of zero-alpha funds) is determined by 10,000 bootstraps of the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset that minimize mean squared error (the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as ). To mitigate potential low signal-to-noise bias in , we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , which is computed analogously, except to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times to re-estimate p-values (the threshold p-value is denoted as ). The Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach is used for simulation. Second, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (), zero-alpha () and underperforming funds (). We use from (and ) and a threshold significance level γ to estimate proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. A threshold significant level is identified when the mean squared error is minimized. When from the is used, we bootstrap the estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. When from the is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. Superscript ○ on or is associated with optimized or , and without superscript, is calculated as a residual, . and are based on optimized or but fixed at -values of 0.05 and 0.10. Also reported are and as well as and using fixed and parameters on estimated and -values based on actual fund-month net excess returns. Third, we compute Fama and French (2010) %Sim < Act. Column “Sim” reports average from 10,000 simulated samples of demeaned fund-month net excess returns, and column “%Sim < Act” the percent of 10,000 simulations with lower than actual. Columns shaded in gray highlight Fama and French (2010) results.

Table 4 Panel A also shows baseline 5-factor benchmark results. Two-tail and %Sim < Act show 50.5% of corporate bond mutual funds outperform. In contrast, two-tail and %Sim < Act show only 29.2% of government bond funds outperform.

5.2. Corporate Bond Mutual Funds by AUM

Substantial evidence exists in the literature to suggest decreasing returns to scale among equity mutual fund returns. For example, Berk and Green (2004) use all mutual funds from CRSP mutual funds database to show that managers’ ability to generate high average returns decreases as the scale of operations increases. Zhu (2018) confirms diseconomies of scale exist among actively managed domestic equity-only US mutual funds from MorningStar database. Barras et al. (2022) find 82.4% of the entire population of open-end actively managed US equity funds from CRSP database experience diseconomies of scale, and a statistically significant magnitude of the scale coefficient. Specifically, they find that, on average, gross alpha is lower by 1.3% per year for a one-standard-deviation increase in fund size. They also document that the majority of value-destroying funds in the sample could create value if they were to scale down their fund size. Comparatively limited evidence exists for bond mutual funds—Huang et al. (2025a) is an exception.

To examine the effects of fund size in bond mutual funds, we categorize actively managed corporate bond mutual funds by AUM as small (USD 5M to 250M AUM), mid-size (USD 250M to 750M AUM), and large (AUM > USD 750M). Table 5 shows performance declines with fund size, consistent with diseconomies of scale (Berk & Green, 2004) and Huang et al. (2025a). Table 5 Panel B column bottom section shows that for the conditional 12-factor model, the percentages of outperforming bond funds () are 49.6% for small, 35.2% for mid-size, and 36.0% for large corporate bond funds. Table 5 Panel A column bottom section reports that for the unconditional baseline 5-factor benchmark model, the percentages of outperforming bond funds () are 40.6% for small, 33.4% for mid-size, and 24.2% for large corporate bond funds.

Table 5.

Percentile Distributions of on Actively Managed Corporate Bond Mutual Funds Sorted by AUM. This table sorts a sample of 226 actively managed corporate bond mutual funds over the period 1999–2016 sorted by assets under management (AUM). Number of funds are shown in parentheses. Fund performances are evaluated by two approaches. First, rank funds by percentile on . Column “Actual” reports of 5- and 12-factor models. Column “-value” reports standard p-value of estimated . Following Storey (2002) and Storey et al. (2004), we compute positive FDR-adjusted probability , which adjusts the probability of a fund at percentile rank for the false positives (lucky) and negatives (unlucky) of zero-alpha funds. Results are shown in column “.” In the calculation, (overall proportion of zero-alpha funds) is determined by 10,000 bootstraps of the p-values of alpha from the actual dataset that minimize the mean squared error (the threshold p-value associated with is denoted as ). To mitigate potential low signal-to-noise bias in , we follow Huang et al. (2025a) to estimate , which is computed analogously, except to determine , rather than bootstrap the actual p-values as in computation, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times to re-estimate p-values (the threshold p-value is denoted as ). The Fama and French (2010) bootstrap-by-month approach is used for simulation. Second, we follow Barras et al. (2010) to separate funds into outperforming (), zero-alpha () and underperforming funds (). We use from (and ) and a threshold significance level γ to estimate proportions of outperforming and underperforming funds. A threshold significant level is identified when the mean squared error is minimized. When from the is used, we bootstrap the estimated from the actual dataset to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. When from the is used, we bootstrap the actual dataset 10,000 times, and are re-estimated for each simulation to find the threshold , then compute and . The bottom section of column “” reports results. Superscript ○ on or is associated with optimized or , and without superscript, is calculated as a residual, . and are based on optimized or but fixed at -values of 0.05 and 0.10.

6. Robustness Tests

Finally, we report results from three robustness tests for bond mutual funds in Supplementary Materials S5. In the first test, because bonds, particularly corporate bonds, are traded infrequently and in relatively opaque and illiquid over-the-counter markets, purchases and sales of bonds can involve large bid-ask spreads. We therefore consider secondary market illiquidity and turnover to show their adverse (negative) effects on returns. We find active management generates lower but still significant t(α). In the second test, we examine mutual funds’ short-term performance. The literature on mutual fund performance examines persistence of short-term returns (Carhart, 1997; Fama & French, 2010) for evidence of outperformance. For comparison purposes, we therefore partition our sample into six non-overlapping contiguous sub-periods of 36 months each and repeat our analysis. When time-varying risk is considered, the value of active management generally comes from longer holding periods. In the third test, we show that potential low signal-to-noise bias in FDR is mitigated using re-estimated t(α) and p-value from bootstrap samples. These findings are consistent with those of Huang et al. (2025b).

7. Economic Significance of Outperformance

While this paper focuses on the question whether US actively managed domestic bond vs. equity mutual funds tend to outperform, its authors recognize that some readers, particularly practitioners, may be interested in the economic significance of this outperformance. For investors, we therefore report average annualized alphas in percentage terms for all actively managed bond funds, government bond funds, and corporate bond funds, categorized as outperforming, in the Supplementary Materials S5.4.

For all actively managed bond mutual funds, recall that for the 5-factor model, FDR q-values and %Sim < Act show bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform. For economic significance, Supplementary Materials Table S9 shows average annualized alpha for all actively managed bond mutual funds classified as outperforming using the 5-factor model (top 30th percentile and above) is 1.92%. For the 12-factor model, FDR q-values and %Sim < Act show bond funds at the 80th percentile and above outperform. For economic significance, Supplementary Materials Table S9 shows average annualized alpha for funds classified as outperforming (top 20th percentile and above) using the 12-factor model is 2.91%. Separating corporates from governments, Supplementary Materials Table S9 shows and %Sim < Act show corporate bond mutual funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform using either the 5- or 12-factor model, whereas government bond funds at the 70th percentile and above outperform using the 5-factor model, but when using the 12-factor model only the 90th percentile and above outperform. For economic significance, average annualized alpha for corporate bond funds that outperform using the 5-factor (12-factor) models are 2.59% (3.25%), and for government bond funds 1.51% (2.83%).

Other measures of the economic significance of fund performance, such as value added to the fund (Berk & van Binsbergen, 2015), the Information Ratio, Sortino Ratio, or CvaR adjusted alpha, for bond funds, could also be of interest. However, raw and FDR-adjusted Skill Ratio results building on Berk and van Binsbergen (2015) are reported in detail in Huang et al. (2025a) for bond mutual funds. In the interests of brevity, we leave a combination of this paper with Huang et al. (2025a) that compares Skill Ratios of bond vs. equity funds to future research. Similarly, conciseness dictates that we also leave reporting of additional variables such as the Information Ratio, Sortino Ratio, and CvaR adjusted alpha, to future research.

8. Conclusions

This paper makes three contributions to the literature on mutual fund manager performance and FDR. First, it is the first to compare bond vs. equity mutual fund performance using modified FDR-adjusted p-value () from Huang et al. (2025a) and %Sim < Act from Fama and French (2010). Second, it is the first to demonstrate that Fama and French (2010)-style precision adjusted returns results are prone to Type II error both for bond and equity mutual funds, consistent with predictions made only for equity mutual funds in Harvey and Liu (2020). Third, it confirms the relationship between fund performance vs. fund size (as measured by AUM) for corporate bond mutual funds, consistent with Berk and Green (2004) and Huang et al. (2025a).

Specifically, we compare bond vs. equity mutual fund performance using the FDR approach to actively managed bond vs. equity mutual funds. Using and Fama and French (2010) methodology, we find bond funds tend to outperform more than equity funds, with 33.9% (30.0%) of bond funds generating + t(α) on net returns vs. 1.8% (0.0%) for equities. We find Harvey and Liu’s (2020) prediction that %Sim < Act (Fama & French, 2010) is prone to Type II errors among bond funds and mutual funds alike.

While most of our bond funds demonstrate zero-alpha, a significant amount exhibit outperformance. This finding reflects Berk and Green (2004)’s competitive equilibrium where investors cannot effectively detect outperforming funds. Equity mutual funds comparatively underperform more than bond mutual funds. Fama and French (2010)-style precision-adjusted alpha t(α) results are qualitatively similar. Performance of actively managed corporate bond funds tends to be better than for governments, consistent with higher information costs on corporate vs. government bonds. However, even government bond funds demonstrate comparatively better fund manager outperformance compared to equity fund managers. To examine the relation between scale and performance for bond mutual funds, we separate corporate bond mutual funds into three groups based on AUM. As predicted in Berk and Green (2004), we find diminishing returns to scale in bond mutual funds as well as equity mutual funds. Finally, we find (in Supplementary Materials S5.1) that high turnover reduces bond fund performance, consistent with higher spreads and relative illiquidity of bonds vs. equities. In Supplementary Materials S5.2, we show that outperformance is more evident in the long term. When time-varying risk is considered, we find that the value of active bond fund management comes primarily from long holding periods.

This paper’s sample period covers 1999–2016. Our empirical tests focus on this period due to data availability (pre-1999 data are unavailable) and to ensure results are comparable with related papers, namely Huang et al. (2025a, 2025b). On the one hand, our sample period misses 2017 low interest rates, COVID-19 market stresses, and post-COVID market conditions. On the other hand, 2017 interest rates are reminiscent of post-Great Recession interest rates, and the Great Recession and its aftermath are in the sample. Arguably, COVID-19 and post-COVID conditions are once-in-a-lifetime events, with their most recent precedent being the 1919 Swine Flu and aftermath. Practitioners should nevertheless bear in mind our time period limitations when assessing implications of our conclusions.

All tests in this paper are for US-based domestic actively managed bond vs. equity mutual funds. US markets are arguably more developed than those of some other countries, rendering generation of excess returns by mutual funds covering other countries potentially easier. One interesting extension of our work that we leave to future research could be a comparison of US-based domestic actively managed vs. international developed vs. emerging market bond and equity mutual funds. It would also be interesting to determine the degree to which our results hold for non-US-based actively managed funds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jrfm19010089/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, L.H., W.Y.L., C.G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from CRSP Mutal Funds and Morningstar Direct and are available from the authors with the permission of CRPS and Morningstar.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based in part on the doctoral dissertation of Lifa Huang at the University of Arkansas. We thank Daniel Pu Liu, Scott Hsu, Xi Li, Alexey Malakov, Tim Riley, and seminar participants at the University of Arkansas for their valuable comments. We especially thank Gjergji Cici, Campbell R. Harvey, Fabio Moneta, Russ Wermers, and other seminar participants at the 2019 American Finance Association annual meeting where a related version of this paper, “Selection and Timing Skill in Bond Mutual Fund Returns: Evidence from Bootstrap Simulations,” was presented. We also thank Stefan Nagel and anonymous reviewers at Journal of Finance, Financial Management, and Journal of Banking and Finance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Berk and van Binsbergen (2015) measure manager performance as a function of fund value-added. This measure is addressed in Huang et al. (2025a). |

| 2 | Harvey and Liu (2020) point out that Type I false discoveries must be balanced against Type II missed discoveries—a failure to identify positive-alpha managers as skilled. Using a double-bootstrap approach, Harvey and Liu (2020) show the Fama and French (2010) single-bootstrap approach is less likely to attribute luck to skill when fund managers are unskilled but more likely to attribute skill to luck when fund managers are skilled. |

| 3 | See Fama and French (2010, p. 1925). Kosowski et al. (2006) introduce potential bias by simulating funds rather than months. |

References

- Andrikogiannopoulou, A., & Papakonstantinou, F. (2019). Reassessing false discoveries in mutual fund performance: Skill, luck, or lack of power? Journal of Finance, 74, 2667–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barras, L., Gagliardini, P., & Scaillet, O. (2022). Skill, scale, and value creation in the mutual fund industry. Journal of Finance, 77, 601–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barras, L., Scaillet, O., & Wermers, R. (2010). False discoveries in mutual fund performance: Measuring luck in estimated alphas. Journal of Finance, 65, 179–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J. B., & Green, R. C. (2004). Mutual fund flows and performance in rational markets. Journal of Political Economy, 112, 1269–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, J. B., & van Binsbergen, J. H. (2015). Measuring skill in the mutual fund industry. Journal of Financial Economics, 118, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C. R., Elton, E. J., & Gruber, M. J. (1993). The performance of bond mutual funds. Journal of Business, 66, 371–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Ferson, W., & Peters, H. (2010). Measuring the timing ability and performance of bond mutual funds. Journal of Financial Economics, 98, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordia, T., Roll, R., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2001). Market liquidity and trading activity. The Journal of Finance, 56(2), 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B., Hastie, T., Johnstone, I., & Tibshirani, R. (2004). Least angle regression. Annals of Statistics, 32, 407–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elton, E. J., Gruber, M. J., & Blake, C. R. (1995). Fundamental economic variables, expected returns, and bond fund performance. Journal of Finance, 50, 1229–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. (2010). Mutual fund incubation. Journal of Finance, 65, 1581–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in stock and bond returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2010). Luck versus skill in the cross-section of mutual fund returns. Journal of Finance, 65, 1915–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferson, W. E., Henry, T., & Kisgen, D. (2006). Evaluating government bond mutual funds using stochastic discount factors. Review of Financial Studies, 19, 423–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferson, W. E., & Schadt, R. W. (1996). Measuring fund strategy and performance in changing economic conditions. Journal of Finance, 51, 425–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K. R. (2008). The cost of active investing. Journal of Finance, 63, 1537–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gârleanu, N., & Pedersen, L. H. (2018). Efficiently inefficient markets for assets and asset management. Journal of Finance 73, 1663–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C. R., & Liu, Y. (2020). False (and missed) discoveries in financial economics. Journal of Finance, 75, 2323–2849. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L., Lee, W. Y., & Rennie, C. G. (2025a). Bond mutual fund performance: Evidence from the skill ratio and false discovery rate. The Financial Review, 60(3), 865–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Lee, W. Y., & Rennie, C. G. (2025b). Selection and timing skill in bond mutual fund returns: Evidence from bootstrap simulations. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesh, N., & Titman, S. (1993). Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. The Journal of Finance, 48(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowski, R., Timmermann, A., Wermers, R., & White, H. (2006). Can mutual fund “stars” really pick stocks? New evidence from a bootstrap analysis. Journal of Finance, 61, 2551–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, F. (2015). Measuring bond mutual fund performance with portfolio characteristics. Journal of Empirical Finance, 33, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J. D. (2002). A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 64, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J. D., Taylor, J. E., & Siegmund, D. (2004). Strong control, conservative point estimation and simultaneous conservative consistency of false discovery rates: A unified approach. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 66, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M. (2018). Informative fund size, managerial skill, and investor rationality. Journal of Financial Economics, 130, 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.