Abstract

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) play a vital role in an economy, providing essential goods and services to citizens. However, they often face governance, transparency, and accountability challenges, leading to poor performance and waste of public resources. Thus, we examine the role of internal auditing in adding value to performance improvement in Ghana’s SOEs. We employ quantitative and cross-sectional survey designs to collect data from 1150 internal auditors across the SOEs and utilize macro-process modeling to analyze the data. We identify four indicators of internal auditing as value addition: internal audit effectiveness, quality, independence and resources; they have strong significant positive relationships with performance improvement (organizational performance and governance and accountability). However, these relationships are negatively moderated by organizational complexity (structural, process and systemic). We provide empirical evidence on the nuanced interplay between internal auditing, organizational complexity, and performance improvement in the context of Ghana’s SOEs, offering actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners to enhance governance and performance in emerging economies. Our findings underscore the need for SOEs to prioritize internal audit effectiveness and manage complexity to maximize performance gains.

1. Introduction

SOEs play a vital role in an economy, providing essential goods and services to citizens. However, they often face governance, transparency, and accountability challenges, leading to poor performance and waste of public resources. These challenges are also related to inefficiency and corruption, which can hinder their performance and impact on the economy (Hilton & Arkorful, 2021). Internal auditing has emerged as a crucial tool for improving performance and accountability in public organizations. Internal auditing is a key module of good governance in SOEs, providing assurance that the organization’s operations are efficient, effective, and compliant with laws and regulations (Quampah et al., 2021). This makes internal auditing inevitable in the effective and efficient management of SOEs. However, not much attention has been paid to the value addition of internal auditing in improving performance of SOEs, particularly in developing economies like Ghana.

The importance of SOEs in Ghana’s economy cannot be overstated, as they operate in a complex environment shaped by government policies, regulations, and stakeholder expectations. They provide critical infrastructure, services, and goods that are essential for the country’s development. Yet, their performance has been a subject of concern, as many of them face governance, accountability and transparency challenges, leading to poor performance and inefficiency (Awaah, 2025). Internal auditing has been identified as a potential solution to this problem, but its effectiveness depends on various factors, including the quality of audit services, independence, and resources (Karikari et al., 2022). This study, therefore, examines the relationship between internal auditing as value addition and performance improvement in Ghana’s SOEs.

Internal auditing can identify areas for improvement and provide recommendations for change, which can help to improve performance and accountability (Appiah et al., 2023). Furthermore, internal audit functions are increasingly crucial for accountability and efficiency due to complex organizational structures and rising risk management expectations (Abubakari et al., 2025). Despite the relevance of internal auditing in SOEs, there is a lack of research on its role in adding value to performance improvement in Ghana’s SOEs. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the role of internal auditing in adding value to performance improvement in Ghana’s SOEs. This study also develops a conceptual framework for internal auditing as a value addition to performance improvement in SOEs. The framework also captures organizational complexity (in terms of structures, processes and systems) to ascertain whether it can enhance or debilitate the effect of internal auditing on performance improvement, thereby further underscoring the explicit novelty of the study. Thus, the study’s findings provide insights into the role of internal auditing in improving performance and accountability in SOEs, offering recommendations for policymakers and practitioners seeking to improve governance and performance in SOEs.

The study is grounded in agency theory and stewardship theory, which provide a framework for understanding the role of internal auditing in improving performance and accountability. The agency theory posits that internal auditing plays a monitoring role in ensuring that agents (managers) act in the best interests of principals (owners) (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The stewardship theory, on the other hand, suggests that internal auditing plays a supportive role in improving performance and accountability (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). These theories provide theoretical framework for the study and basis for the conceptual model, which is underscored by empirical studies. They have guided us in determining the appropriate indicators for the variables, leading to a well-developed conceptual model. Furthermore, we employ a quantitative approach to collect numeric data for statistical assessment of the relationship between internal auditing as a value addition and performance improvement, increasing the generalizability of our findings. Thus, this study is germane because it contributes to the existing body of knowledge on internal auditing and performance improvement in SOEs by providing valuable insights to inform tailored policy and practice in enhancing performance and accountability in SOEs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on the theories, internal auditing and performance improvement and set hypotheses, Section 3 describes the methodology, Section 4 presents the results and discussion, and Section 5 highlights implications and concludes.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Underpinning Theories

Internal auditing is underpinned by several theories, including agency theory and stewardship theory. Agency theory suggests that internal auditing plays a monitoring role, ensuring that agents (managers) act in the best interests of principals (shareholders) (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). This theory posits that managers, as agents, may have different goals and interests than the principals, and therefore, internal auditing is necessary to monitor and control their actions. In the context of SOEs, agency theory is particularly relevant, as the government, as the principal, may have limited control over the actions of managers, and internal auditing can provide assurance that managers are acting in the best interests of the state.

The agency theory perspective on internal auditing is supported by several studies, which suggest that internal auditing can play a crucial role in monitoring and controlling the actions of management. For example, Jensen and Meckling (1976) found that internal auditing can help to reduce agency costs by monitoring the actions of management and ensuring that they act in the best interests of shareholders. Similarly, Adams (1994) argues that internal auditing can provide an independent check on management’s actions, which can help to prevent fraud and corruption. However, some critics argue that agency theory oversimplifies the complexities of organizational behavior and neglects the role of trust and cooperation in governance (Ghoshal, 2005).

In contrast, stewardship theory submits that internal auditing plays a supportive role, providing guidance and advice to management to improve performance (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). This theory posits that managers, as stewards, are motivated to act in the best interests of the organization, and internal auditing can provide valuable insights and recommendations to help them achieve this goal. In the context of SOEs, stewardship theory is relevant, as managers may be motivated to improve performance and contribute to the development of the country.

The stewardship theory perspective on internal auditing is also supported by several studies, which suggest that internal auditing can play a supportive role in improving performance. For instance, Donaldson and Davis (1991) found that internal auditing can provide valuable guidance and advice to management, which can help to improve performance and accountability. Similarly, Hernandez (2012) argues that internal auditing can help to build trust and cooperation between management and stakeholders, which can lead to improved performance. Nevertheless, stewardship theory has been criticized for being overly optimistic about the motivations of managers and neglecting the potential for self-interest (Hernandez, 2012).

2.2. Internal Auditing as Value Addition

Internal auditing is a critical component of good governance that provides assurance that the organization’s operations are efficient, effective, and compliant with laws and regulations (Quampah et al., 2021). Research has shown that internal auditing can add value to organizations by improving their performance and accountability (Arena & Azzone, 2009). Internal auditing can add value to SOEs by improving risk management (i.e., identifying and assessing risks that can impact the organization’s objectives), enhancing governance (i.e., providing assurance that the organization’s operations are aligned with its objectives and values), increasing efficiency (i.e., identifying areas for improvement and providing recommendations for process improvements), and promoting accountability (i.e., ensuring that the organization’s operations are transparent and accountable). In modern studies, four main determinants of internal auditing as value addition emerged including internal audit effectiveness (IAE), internal audit quality (IAQ), internal audit independence (IAI), and internal audit resources (IAR). These determinants are carefully reviewed in the ensuing paragraphs.

IAE is a crucial determinant of the value addition of internal auditing. Effective internal auditing can lead to improved risk management, better internal controls, and more efficient operations (Chen et al., 2020). IAE is influenced by factors such as the use of a risk-based approach to auditing, the development and execution of audit plans, and the provision of timely and relevant audit reports (COSO, 2017). Moreover, effective internal auditing requires internal auditors to have the necessary skills and competencies to perform audits effectively (Tackie et al., 2016). The internal audit function should also ensure that audit findings and recommendations are communicated to stakeholders in a clear and concise manner, and that follow-up actions are taken to address identified issues (Malhi et al., 2023). Furthermore, IAE can be enhanced by measuring and reporting on stakeholder satisfaction with the audit process (Tackie et al., 2016). This helps ensure that the internal audit function meets the needs of stakeholders and adds value to the organization.

The quality of internal auditing is also an important factor in determining its impact on performance improvement. Research has shown that high-quality internal auditing can lead to improved audit outcomes and better decision-making (Bello, 2018; Deis & Giroux, 1992). IAQ is influenced by factors such as the use of a robust and consistent audit methodology, the maintenance of accurate and complete audit documentation, and adherence to relevant audit standards and guidelines (IIA, 2017). High-quality internal auditing also requires internal auditors to have access to ongoing training and professional development opportunities, enabling them to stay up-to-date with developments in the field and maintain their professional competence (IIA, 2017). Furthermore, IAQ can be enhanced by implementing a quality assurance and improvement program, which involves regular review and assessment of the internal audit function (Chen et al., 2020).

The independence of internal auditors is critical for ensuring objectivity and impartiality (IIA, 2017). IAI is influenced by factors such as the organizational structure, reporting lines, and access to information (IIA, 2024). Internal auditors should be free from interference and influence, allowing them to carry out their work without bias or coercion (Abbood & Maaeni, 2022). Moreover, IAI can be enhanced by ensuring that internal auditors have unrestricted access to information and personnel, and that they are able to report directly to the audit committee or board of directors (Malhi et al., 2023).

The resources available to internal auditors, including funding and personnel, can impact the effectiveness of internal auditing (IIA, 2017). Research has shown that adequate resources are essential for ensuring the success of internal auditing (Al-Twaijry et al., 2003). IAR include factors such as budget and funding, personnel and staffing, training and development, technology and tools, and access to external expertise (IIA, 2017). Adequate resources enable internal auditors to carry out their work effectively, including conducting audits, providing training, and advising management (IIA, 2017). Moreover, IAR can be enhanced by investing in technology and tools, such as audit software and data analytics, which can help to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the internal audit function (Chen et al., 2020).

2.3. Performance Improvement

Performance improvement is a critical goal for organizations across various sectors, including SOEs. Performance improvement can be achieved through efficient use of resources, effective risk management, improved governance, and enhanced accountability (Sawan & Alzeban, 2013). Efficient use of resources involves optimizing the use of resources to achieve organizational objectives, while effective risk management involves identifying and mitigating risks that can impact the organization’s objectives (COSO, 2017). Improved governance ensures that the organization’s operations are aligned with its objectives and values, and enhanced accountability promotes transparency and accountability in the organization’s operations (Malhi et al., 2023).

Performance improvement can be measured in various ways, including financial performance, operational efficiency, and compliance with laws and regulations (Arena & Azzone, 2009). Financial performance can be measured using metrics such as return on investment (ROI) and return on equity (ROE), while operational efficiency can be measured using metrics such as productivity and cycle time (Awaah, 2025). Compliance with laws and regulations can be measured using metrics such as audit findings and regulatory compliance rates (Karikari et al., 2022).

Two key dimensions of performance improvement are organizational performance (OP) and governance and accountability (GA). These dimensions are critical for ensuring that organizations achieve their goals and objectives, while also promoting transparency, accountability, and good governance. According to Kaplan and Norton (1996), OP is a key driver of strategy implementation, while GA are essential for ensuring that organizations are managed in a responsible and transparent manner. Research has shown that OP and GA are interrelated and mutually reinforcing (OECD, 2015). Effective GA can lead to improved OP, while improved OP can also contribute to enhanced GA (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Therefore, it is essential to focus on both OP and GA to achieve sustainable performance improvement.

OP refers to the extent to which an organization achieves its goals and objectives, while also considering the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations (Richard et al., 2009; Hilton et al., 2021). OP is a critical outcome of effective internal auditing, and studies have found that internal auditing can lead to improved OP (Arena & Azzone, 2009). Effective internal auditing can contribute to improved OP by identifying areas for improvement and providing recommendations for change (Al-Twaijry et al., 2003; Appiah et al., 2023). Internal auditing can lead to improved financial performance by reducing costs and increasing revenue and can also improve operational efficiency by streamlining processes and eliminating waste (Sawan & Alzeban, 2013).

GA refer to the systems, processes, and practices that ensure an organization is managed in a responsible and transparent manner, with clear lines of accountability and oversight (OECD, 2015). GA are also important outcomes of effective internal auditing, and research has shown that internal auditing can contribute to improved GA by providing assurance that the organization’s operations are transparent and accountable (Abbood & Maaeni, 2022). Effective GA are critical for ensuring that an organization’s operations are aligned with its objectives and values, and that stakeholders have confidence in the organization’s management and operations (Abbood & Maaeni, 2022). Internal auditing can contribute to improved GA by providing assurance that the organization’s risk management, control, and governance processes are operating effectively (COSO, 2017).

2.4. Organizational Complexity

Organizational complexity refers to the degree of intricacy and interconnectedness within an organization (Duncan, 1972). It is a multifaceted concept that encompasses various aspects of an organization’s design, operations, and environment (Abubakari et al., 2025). It is characterized by three main dimensions: structural complexity (SC), process complexity (PC), and systemic complexity (StC) (Burton & Obel, 2018; Mihret & Yismaw, 2011). Understanding organizational complexity is important, as it can influence the effectiveness of internal auditing and its impact on OP and GA (Burton & Obel, 2018; Daft, 2015). Internal auditors must be aware of the complexities of the organization and adapt their audit approaches accordingly to provide effective assurance and consulting services.

SC refers to the degree of differentiation and integration within an organization’s structure, including the number of departments, levels of hierarchy, and communication channels (Al-Twaijry et al., 2003; Daft, 2015). Organizations with high levels of structural complexity often have multiple layers of management, complex reporting relationships, and a high degree of specialization (Daft, 2015). This can create challenges for internal auditors, who must navigate these complex structures to identify and assess risks.

PC denotes to the degree of intricacy and variability in an organization’s business processes, including the number of processes, process interdependencies, and process changes (Hammer, 2007). Organizations with high levels of process complexity often have multiple interconnected processes that require careful coordination and management (Christensen et al., 2021). This can create challenges for internal auditors, who must understand these processes to identify and assess risks (Christensen et al., 2021).

StC is the degree of interconnectedness and interdependence among an organization’s systems, including the IT infrastructure, organizational culture, and external environment (Senge, 2006). Organizations with high levels of systemic complexity often have complex IT systems, a strong organizational culture, and a high degree of interdependence with external stakeholders (Burton & Obel, 2018). This can create challenges for internal auditors, who must understand these systems to identify and assess risks (Sawan & Alzeban, 2013).

2.5. Internal Auditing as Value Addition and Performance Improvement

2.5.1. Internal Audit Effectiveness, Performance Improvement and Organizational Complexity

IAE is a critical factor in determining the effect of internal auditing on OP. Studies have found that IAE is positively related to OP (Arena & Azzone, 2009; Al-Twaijry et al., 2003). Effective internal auditing can lead to improved risk management, better internal controls, and more efficient operations (IIA, 2017). Recent studies by Appiah et al. (2023) and Shahini-Gollopeni et al. (2022) found that IAE has a significant positive effect on OP. This is because effective internal auditing can help organizations identify and mitigate risks, improve their internal controls, and optimize their operations. IAE can also lead to improved decision-making, as it provides management with accurate and timely information about the organization’s operations (Mihret & Yismaw, 2011). However, the relationship between IAE and OP was not controlled, thereby omitting relevant variables that could change the dynamic of the relationship.

IAE is also important for GA. Effective internal auditing can provide assurance that an organization’s governance processes are operating effectively, and that accountability mechanisms are in place (Appiah et al., 2023). This is because internal auditing can help organizations assess the effectiveness of their governance structures, identify areas for improvement, and provide recommendations for improvement (Bello et al., 2018). A study by Mihret and Yismaw (2011) found that IAE has a positive effect on GA, particularly in terms of transparency and accountability mechanisms. Additionally, IAE can lead to improved stakeholder trust, as it gives an indication that the firm is being managed well and in an accountable manner (Maseer & Flayyih, 2021). Based on the foregoing, we hypothesize that:

H1a.

IAE has a positive effect on OP.

H1b.

IAE has a positive effect on GA.

Despite the established positive relationship between IAE and both OP and GA, the findings are limited in scope as far as SOEs are concerned, which we believe are critical public organizations with complex structures and operations that could breed corruption without effective internal auditing. We are also of the view that given the complex nature of some organizations, including SOEs, the relationship between IAE and OP and GA should have been moderated by organizational complexity to provide nuanced understanding of that relationship. For instance, in organizations with high levels of complexity, IAE may be more important for improving OP, as it can help to identify and mitigate risks associated with complex organizational structures (Abubakari et al., 2025). Similarly, in organizations with high levels of complexity, IAE may be more important for improving GA, as it can help to ensure that governance processes are operating effectively despite the complexity of the organization (Abubakari et al., 2025). But it is imperative to know the extent to which organizational complexity may interfere with the positive relationship between IAE and OP and GA. Hence, we further hypothesize that

H1c.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAE on OP;

H1d.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAE on GA.

2.5.2. Internal Audit Quality and Performance Improvement and Organizational Complexity

IAQ is an essential factor in determining performance improvement as demonstrated by existing studies. For instance, a study by Bello (2018) found that IAQ has a significant positive effect on OP, particularly in terms of financial performance and operational efficiency. This is because high-quality internal auditing can provide management with accurate and timely information about the organization’s operations, and help them identify areas for improvement (Bello, 2018). Furthermore, IAQ can also lead to improved risk management, as it provides assurance that the organization’s risk management processes are operating effectively (Sawan & Alzeban, 2013). However, Adurayemi et al. (2025) revealed that IAQ has no significant effect on employee productivity, which is an aspect of OP. This provides contradicting perspective that must be further investigated.

IAQ can also influence GA. It can provide assurance that a firm’s governance systems and processes are operating effectively, and that there are mechanisms for accountability (Maseer & Flayyih, 2021). This is because high-quality internal auditing can help organizations identify areas for improvement and provide recommendations for improvement (Bello et al., 2018). A study by Abbood and Maaeni (2022) observed that IAQ has a positive influence on GA, particularly in terms of transparency and accountability mechanisms. Furthermore, IAQ can provide assurance to stakeholders that the organization is being managed in an accountable manner (Maseer & Flayyih, 2021). Based on the foregoing, we hypothesize that

H2a.

IAQ has a positive effect on OP;

H2b.

IAQ has a positive effect on GA.

It is probable that the relationship between IAQ and OP and GA can be interfered by how complex the organization is. Given that organizations with high levels of structural complexity often have multiple layers of management and complex reporting relationships (Daft, 2015), internal auditors may face obstacles in navigating the complex structures to identify and assess risks, thereby affecting the quality of their function and ultimately impeding performance and accountability (Burton & Obel, 2018). Thus, the examination of the relationship between IAQ and performance by prior studies without considering organizational complexity in the model creates a significant gap in the literature that this study seeks to fill. We, therefore, hypothesize that

H2c.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAQ on OP;

H2d.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAQ on GA.

2.5.3. Internal Audit Independence, Performance Improvement, and Organizational Complexity

The independence of internal auditors is critical for ensuring objectivity and impartiality (IIA, 2017). Studies such as Al-Twaijry et al. (2003) have found that IAI is positively related to OP. A recent study by Malhi et al. (2023) revealed that IAI has a significant positive influence on OP. This is because independent internal auditors can provide unbiased and objective assessments of the organization’s operations and identify areas for improvement without fear of reprisal. IAI can also lead to improved performance, as it provides management with objective and unbiased information about the organization’s operations (Mihret & Yismaw, 2011).

Again, IAI is crucial for GA. Independent internal auditors can provide assurance that an institution’s governance processes are operating effectively, and that accountability mechanisms are in place (Appiah et al., 2023; IIA, 2017). This is because independent internal auditors can assess the effectiveness of the organization’s governance structures without fear of reprisal and provide recommendations for improvement. In their study, Mihret and Yismaw (2011) revealed that IAI has a positive effect on GA, particularly in terms of transparency and accountability mechanisms. In addition, IAI can lead to improved stakeholder confidence, as it provides assurance that the organization is being managed in a responsible and accountable manner (IIA, 2017; Maseer & Flayyih, 2021). Consequently, we hypothesize that:

H3a.

IAI has a positive effect on OP.

H3b.

IAI has a positive effect on GA.

Organizational complexity may moderate the relationship between IAI and OP and GA such that the positive relationship may be enhanced or lessened. However, previous studies overlooked this possibility, creating a research gap that must be filled. For example, since organizations with high levels of process complexity often have multiple, interconnected processes that require careful coordination and management (Christensen et al., 2021), coupled with a high degree of specialization (Daft, 2015), internal auditors must understand these processes and engage everyone that matters, thereby affecting their smooth functions. In firms with high levels of complexity, IAI may be essential for improving OP and GA, as it can help to ensure that internal auditors are able to operate independently and effectively (Malhi et al., 2023). Thus, it is important to include organizational complexity in the model for assessing the relationship between IAI and OP and GA to statistically affirm the interplay among these variables. Hence, we hypothesize that:

H3c.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAI on OP.

H3d.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAI on GA.

2.5.4. Internal Audit Resources, Performance Improvement and Organizational Complexity

The resources available to internal auditors, including funding and personnel, can make internal audit functions more effective to contribute to performance and accountability (Chen et al., 2020; IIA, 2017). A study by Chen et al. (2020) ascertained that IAR has a significant positive relationship with OP, particularly in terms of financial performance and operational efficiency. This is because adequate resources enable internal auditors to perform their duties effectively and provide management with accurate and timely information about the organization’s operations (Bello et al., 2018). Furthermore, IAR can lead to improved risk management, as they provide assurance that the organization’s risk management processes are operating effectively (IIA, 2024).

Adequate IAR is germane for GA. IAR can provide assurance that an organization is well-resourced to operate effectively, and be accountable to stakeholders (Karikari et al., 2022). This is because adequate resources enable internal auditors to assess the effectiveness of the organization’s governance structures, identify areas for improvement, and provide recommendations for improvement. A study by Tackie et al. (2016) noted that IAR has a positive influence on GA, particularly in terms of transparency and accountability mechanisms. Moreover, IAR can lead to improved performance confidence, as it provides assurance that the organization is well-resourced and being managed responsibly and accountably (IIA, 2024). Based on the foregoing, we hypothesize that:

H4a.

IAR has a positive effect on OP.

H4b.

IAR has a positive effect on GA.

Though the above findings are useful, they might not be applicable in the case of SOEs, as such firms have more complex structures and systems of operation. This means that the empirical evidence on the nexus between IAR and OP and GA without the consideration of organizational complexity as a moderator does not provide deeper insight into the dynamic relationship among the variables. This is because in institutions with high levels of complexity, IAR may be crucial for improving OP and GA, as it can help to ensure that internal auditors have the necessary skills and expertise to operate effectively (Mihret & Yismaw, 2011). Similarly, organizations with high levels of systemic complexity often have complex IT systems, a strong organizational culture, and a high degree of interdependence with external stakeholders (Burton & Obel, 2018), creating challenges for internal auditors with limited resources to understand these systems to identify and assess risks (Sawan & Alzeban, 2013). Thus, it is imperative to know whether the positive relationship between IAR and OP and GA can be increased or decreased by organizational complexity. Since this possibility has been overlooked by prior researchers, we seek to test the moderating effect of organizational complexity on the relationship between IAR and OP and GA, and so hypothesize that:

H4c.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAR on OP.

H4d.

Organizational complexity will moderate the positive effect of IAR on GA.

2.6. Conceptual Model

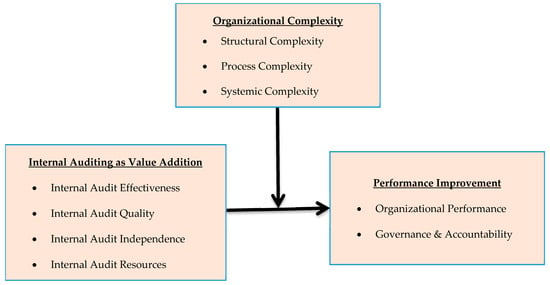

Subsequent to the above theoretical and empirical review, we design a conceptual model (Figure 1) to pictorially illustrate the potential interplay between internal auditing as value addition and performance improvement, including the moderating effect of organizational complexity. The model clearly depicts the relationship between the determinants or indicators (IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR) of internal auditing as value addition and the dimensions (OP and GA) of performance improvement. It also depicts the organizational complexity dimensions (SC, PC and StC). The model demonstrates that though internal auditing can add value to performance improvement, the effect can either be enhanced or debilitated by organizational complexity. Thus, the model serves as a guide to measure the variables and collect data to test the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Source: Authors’ model (2025).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

We employed quantitative and cross-sectional survey designs to examine the relationship between internal auditing as value addition and performance improvement in SOEs. We adopted the quantitative approach because it involves the use of numeric data for statistical analysis or to test hypothesis (Saunders et al., 2016). Since we seek to ascertain the potential effect of internal auditing as value addition on performance improvement, numeric data is necessary so that statistical tests can be conducted. Furthermore, a cross-sectional survey design is suitable to conduct this study within a single moment by using a survey method to collect the data (Hilton et al., 2024). Thus, these designs enabled us to collect numerical data and analyze it using statistical methods to achieve our aim.

3.2. Population and Sampling

The population of this study consists of all SOEs in Ghana. Ghana has 47 SOEs that are overseen by the State Interests and Governance Authority (SIGA). Some of the SOEs include Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), Ghana Grid Company (GRIDCo), Bulk Oil Storage and Transport Company (BOST), Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC), and Ghana Airports Company Limited. These entities operate in various sectors, including finance, energy, transportation, and more. The SIGA is responsible for ensuring good corporate governance practices among these entities. It is worth noting that SIGA responsibility is not limited to the SOEs. According to the 2023 State Ownership Report, SIGA covered 147 entities, including 47 SOEs, 37 Joint Venture entities, and 63 Other State Entities. Nevertheless, the scope of our study covered only SOEs given their poor performance in the recent past but have the potential to significantly contribute to economic growth and employment creation. The target population consists of internal auditors of the SOEs. These personnel directly engage in auditing both financial and operational activities, making them most suitable target.

We employed purposive sampling method to select the respondents to ensure that only those with rich information participate in the survey. This sampling method is also useful for recruiting respondents with desired information, willing and available to participate in the survey (Etikan et al., 2016). Thus, this sampling technique is appropriate for obtaining the right internal auditors with similar characteristics to provide more accurate, reliable, and credible information. It has been widely adopted in similar contexts (see Hilton et al., 2024; Martins et al., 2024; Puni et al., 2022). This method allowed us to set criteria to guide the sampling which might not be possible using other methods (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The criteria included: working as an internal auditor for not less than 10 years, directly engaging in internal audit activities for any SOEs for not less than 10 years, directly involving in internal audit reporting and feedback for not less than 10 years, directly involving in both financial and operational performance appraisal or review for not less than 10 years, and directly or indirectly involving in operations of any SOEs for which performance reports are generated or reviewed for not less than 10 years. Given these criteria, we homogenously purposively selected the respondents from a sample frame to ensure that only those who strictly meet the criteria take part in the survey (Sekaran, 2003). As a result, 25 respondents were selected from each of the 47 SOEs, making a total sample size of 1175. This sample size determination approach is consistent with Saunders et al.’s (2016) recommendation, widely applied in social science studies (see Hilton et al., 2024, 2025; Martins et al., 2024; Puni et al., 2022; etc.).

3.3. Variables Measurement and Data Collection

We collected primary data using a survey questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to collect data on the independent variables (IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR) with adapted items from Arena and Azzone (2009) the dependent variables (OP and GA) with adapted items from Gunday et al. (2011), and the moderators (SC, PC and StC) with adapted items from Duncan (1972) and Burton and Obel (2018). All constructs were measured using a 5-point Likert scale: (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The definition of the variables together with their measuring items have been attached as Appendix A. The data collection lasted seven weeks. To ensure non-response bias, we kept the items simple, straightforward, and brief. We also gave the respondents a few days or weeks to complete the questionnaire. At the end of the survey, we retrieved 1150 valid responses, constituting 97.9% of the total sample size, an acceptable response rate for the analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013; Hilton et al., 2021). Finally, in line with ethical considerations, we obtained permission from heads of various Internal Audit Units of the SOEs. The respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, and their consent was obtained before administering the questionnaire. We also ensured the confidentiality and anonymity of the respondents.

3.4. Data Analysis

We analyzed the data using statistical methods, including descriptive statistics and inferential statistics. Specifically, the descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis. We also conducted common method bias (CMB) check, reliability and validity test, and multicollinearity test. Next, we employed macro-process modeling by Hayes (2018) to perform the moderation-regression analysis to examine the relationship between internal auditing as value addition and performance improvement, including organizational complexity as a moderator. The regression models are specified as follows:

where OP = organizational performance; GA = governance & accountability; IAE = internal audit effectiveness; IAQ = internal audit quality; IAI = internal audit independence; IAR = internal audit resources; OC = organizational complexity; α1–α4 are constants; β1–β8 are coefficients; and μ1–μ4 are the error terms.

OP = α1 + β1IAE1 + β2IAQ2 + β3IAI3 + β4IAR4 + μ1,

OP = α2 + β1IAE1 + β2IAQ2 + β3IAI3 + β4IAR4 + β5IAE_OC5 + β6IAQ_OC6 + β7IAI_OC7 + β8IAR_OC8 + μ2,

GA = α3 + β1IAE1 + β2IAQ2 + β3IAI3 + β4IAR4 + μ3,

GA = α4 + β1IAE1 + β2IAQ2 + β3IAI3 + β4IAR4 + β5IAE_OC5 + β6IAQ_OC6 + β7IAI_OC7 + β8IAR_OC8 + μ4,

3.5. Diagnostic Tests

3.5.1. Common Method Bias

This is a cross-sectional study, where data was collected from the same respondents at the same time or using the same technique for predictors and outcome variables, hence to measure the bias, Harman’s single factor was conducted to determine the extent of CMB in the data. If Harman’s single factor explains more than 50% of the total variance, there is CMB in the data (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The single factor (total variance) extracted is 12.664 and it explains 30.9% of the total variance in the data. Given that the percentage of variance explained (30.9%) is less than 50%, CMB is not dominant in the data. Thus, the data used is bias-free.

3.5.2. Reliability and Validity

For reliability assessment, we performed Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) tests. These tests were used to examine how reliable the instrument used for the study was. CA, which is a value between 0 and 1, is used to measure the internal consistency of the scales. It can be observed from Table 1 that all the scales recorded CA coefficients above the 0.70 prescribed threshold (Field, 2015), illustrating that the instrument was strongly reliable for this study (Hilton et al., 2025). Additionally, CR is a measure of internal consistency that assesses the degree to which a set of indicators measure a single underlying construct. CR values range from 0 to 1, with a value of 0.70 or higher indicating greater reliability and generally considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2019). In this study, CR values were calculated based on the factor loading of each construct in Excel using the formula below. From Table 1, the CR values for all constructs ranged from 0.81 to 0.90, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. This indicates that the constructs (IAE, IAQ, IAI, IAR, SC, PC, StC, OP, and GA) have good internal consistency and reliability.

Table 1.

Reliability and Convergent Validity.

Furthermore, the constructs’ validity assessment was done by testing for convergent and divergent or discriminant validity. Convergent validity deals with the degree to which a construct converges with its indicators, capturing the underlying phenomenon it is intended to measure. We evaluated the convergent validity using average variance extracted (AVE). AVE values range from 0 to 1, with a value of 0.50 or higher indicating greater validity and generally considered acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). We calculated the AVE values in Excel using the output of the factor loading analysis. Specifically, the squared factor loadings of each indicator on its respective construct were averaged to obtain the AVE values (see formula above). The results in Table 1 show that the AVE values for all constructs were above 0.50, ranging from 0.56 to 0.76, indicating that the constructs capture a substantial amount of variance in their respective indicators. This provides evidence of convergent validity. Regarding divergent validity, it deals with the degree to which a construct is distinct from other constructs in the model (i.e., whether the indicators of a construct are not strongly related to the indicators of other constructs). We evaluated divergent validity by comparing the square roots of the AVE values with the correlations between constructs based on Fornell-Larcker criterion that the square root of the AVE value for each construct should be greater than the correlation between the construct and any other construct in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). It can be seen from Table 2 that the square root of the AVE values for each construct is indeed greater than the correlations with other constructs, providing evidence of divergent validity. It follows that the constructs demonstrate good convergent validity, capturing a substantial amount of variance in their respective indicators, and discriminant validity, being distinct from other constructs in the model. This ensures that the constructs are well-defined and accurately measured, providing solid foundation for further analysis and interpretation of the results.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix and Discriminant Validity.

3.5.3. Normality and Multicollinearity

We checked whether the data is parametric or non-parametric using a normality test. This evaluation is essential because we aim to estimate regression models. Applying the rule of thumb (i.e., skewness and kurtosis should fall within +1 and −1 for normally distributed or parametric data) by Tabachnick and Fidell (2013), we utilized skewness and kurtosis to assess the normality of the data. This approach has been widely applied in social science studies (e.g., Hilton et al., 2024, 2025; Martins et al., 2024, Puni et al., 2022; etc.). This procedure is more appropriate because it has no limitation regardless of the sample size like other procedures, such as Kolmogorov–Smirnov, which applies to a sample size of less than 500 (Hair et al., 2010). Tabachnick and Fidell’s (2013) criteria also provide better power than the Lilliefors normality (Steinskog et al., 2007). Given that the skewness and kurtosis for the constructs fall within +1 and −1 (Table 3), it can be concluded that the data is parametric, hence a regression analysis can be carried out. Furthermore, we carried out a multicollinearity test to confirm whether the independent constructs are highly correlated. Applying a rule of thumb on multicollinearity which says that the correlations among the independent variables should not be more than 0.80 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013), it can be noticed from the correlation matrix (Table 3) that there is no case of multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 3 presents descriptive statistical results for the constructs. All independent variables scored mean nearly 4, affirming the indicators (IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR) of internal auditing as value addition just as the indicators (SC, PC and StC) of organizational complexity. Performance improvement can be said to be relatively effective given the mean scores of the indicators (OP and GA). The standard deviations for the constructs show that there are less variations in the responses, which is good. The results show that internal auditing as value addition can be measured by factors such as effectiveness, quality, independence and resources. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of these factors in ensuring the value of internal auditing (Arena & Azzone, 2009).

We estimated the regression models and presented the results in Table 4 and Table 5, where Table 4 relates to the regression results for OP and Table 5 relates to the regression results for GA. Each table contains four blocks, where each block relates to the entry of the individual indicators (IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR) of internal auditing as value addition (predictors), moderators (SC, PC and StC) as controlling variables and interaction terms (predictors × moderators). Thus, the analysis followed a three-step procedure which allowed us to test the main effect (step 1), controlling effect (step 2) and interaction effect (step 3). The results of the tests were entered under coefficients and t-values.

Table 4.

Summary of regression result for organizational performance.

Table 5.

Summary of regression results for governance and accountability.

Regarding the model fitness, the R-square (R-sq), mean squared error (MSE), F-statistics (F-stat) and p-value (p) for the models of the respective blocks are recorded. The R-sq fall between 22% and 50%, indicating the variance in the outcome variable that is explained by the respective models. This range represents a moderate effect size, suggesting that the models captured notable portions of the data’s variability. The MSEs across the models are low given the 1–5 scale, meaning that there are reasonable predictive accuracies. The F-stats across the models are large and their respective p-values are <0.001, indicating that the models are highly statistically significant. This finding shows that the predictors collectively explained a significant portion of the variance in the outcome variable. Overall, the models show moderate explanatory power (R-sq) and reasonable predictive accuracy (MSE), with strong statistical significance (F-stat and p-value), affirming the models’ fitness.

For the main effects, all indicators of internal auditing as value addition have strong significant positive relationship with OP (Table 4). These empirical results mean that IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR will significantly predict OP by the magnitude of the coefficients should there be an increase in them by one unit. Comparing the individual effects, IAI has greater effect on OP. Furthermore, in the exception of IAR which shows negative effect, all indicators of internal auditing as value addition have strong significant positive relationship with GA (Table 5). It follows that an increase in IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR by one unit will lead to significant change in GA by their respective coefficients. Comparatively, IAI has greater effect on GA.

The results of the main effect analysis are consistent with previous studies that have found a positive relationship between IAE and OP (Arena & Azzone, 2009; Appiah et al., 2023; Shahini-Gollopeni et al., 2022). The significant positive relationships between internal audit quality, independence and resources, and OP, are also in line with the findings of Adurayemi et al. (2025), Bello (2018), Chen et al. (2020) and Mihret and Yismaw (2011). These findings support the agency theory, which posits that internal audit functions can help reduce agency costs and improve OP by providing assurance and monitoring management’s actions (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Additionally, the stewardship theory suggests that internal audit functions can also play a stewardship role by providing advice and guidance to management to improve OP (Donaldson & Davis, 1991).

Regarding GA, the findings reveal that internal audit effectiveness, quality, and independence are significant predictors of GA. This is consistent with the study of Maseer and Flayyih (2021), which found that internal audit functions play a critical role in improving GA in organizations. This finding also confirms Abbood and Maaeni’s (2022) finding that IAQ has a positive influence on GA, particularly in terms of transparency and accountability mechanisms. Furthermore, the agency theory supports this finding, as these internal auditing indicators can help improve governance by making management more responsible and accountable (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). The finding that IAI has the greatest effect on OP and GA is also in line with the study of Mihret and Yismaw (2011), which found that IAI is a critical factor in determining the effectiveness of internal audit functions.

In terms of the moderating effect, we first checked the controlling effects and the coefficients for organizational complexity indicators (SC, PC and StC) are significant in all blocks of Table 4 and Table 5. These results show that the moderators have strong positive associations with OP and so they are relevant controls that may augment the effects of IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR on OP and GA. Furthermore, the coefficients for the interaction terms are negative and significant in block 1, 2 and 4 (Table 4). These empirical results show that the positive relationship between IAE, IAQ, IAR and OP is negatively moderated by SC, PC and StC such that the positive effect will likely be decreased by the moderators. However, under block 3, only the coefficient for the interaction term (IAI × StC) is positively significant, indicating a positive moderating effect of StC on the relationship between IAI and OP. Here, the positive effect of IAI on OP will likely be increased by StC. Moreover, the effect of the interaction terms on GA are significant in some cases (Table 5). Specifically, under block 1, only IAE × StC has significant negative effect on GA. Under block 2, IAQ × SC has significant positive effect on GA while IAQ × StC has significant negative effect on GA. Under block 3, IAI × SC has significant positive effect on GA whereas IAI × StC has significant negative effect on GA. Under block 4, only IAR × PC has significant negative effect on GA.

The moderating effects of organizational complexity provide valuable insights into the relationships between internal auditing variables and performance improvement indicators. The negative interaction terms suggest that structural, process, and systemic complexity negatively moderate the relationships between internal audit effectiveness, quality, resources, and OP. However, the positive interaction term (IAI × StC) suggests that StC enhances the positive relationship between IAI and OP. This finding is consistent with the study of Mihret and Yismaw (2011), which found that IAI is more effective in complex organizations. Regarding GA, the findings suggest that organizational complexity has a significant moderating effect on the relationships between internal audit variables and GA. Specifically, the results show that StC negatively moderates the relationship between IAE and GA, while SC positively moderates the relationship between IAQ and GA. Thus, our findings have demonstrated the nuanced understanding of the dynamic relationship between internal auditing and performance improvement by the inclusion of organizational complexity in the model, which had been overlooked by prior researchers.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Our study provides insights into the role of internal auditing in adding value to performance improvement in Ghana’s SOEs. Our main effect analysis has established that all indicators of internal auditing as value addition have significant positive effects on OP. Furthermore, in the exception of IAR which shows negative effect, all indicators of internal auditing as value addition have significant positive effect on GA. Our empirical results also show that the moderating variables (SC, PC and StC) have positive associations with OP and GA such that they could be relevant factors to augment the positive relationship between the independent variables (IAE, IAQ, IAI and IAR) and the outcome variables (OP and GA). However, the interaction effects prove that the moderators rather weaken the positive effect of the independent variables on the outcome variables as all the significant interaction terms depict negative moderating effects. This demonstrates that internal auditing as value addition to performance improvement can be debilitated by organizational complexity.

From a practical perspective, our findings suggest that SOEs should prioritize internal audit independence, quality, effectiveness and resources to improve OP and GA. This can be achieved by ensuring that internal auditors have unrestricted access to information and resources and are not influenced by management or other stakeholders. Additionally, SOEs should invest in IAQ by providing training and development opportunities for internal auditors and ensuring that internal audit functions are adequately resourced. Our findings also suggest that internal audit functions should be tailored to address the unique challenges and complexities of the organization. Specifically, the activities or operations of SOEs should be broken into divisions or specialized units with internal auditors assigned to each unit to reduce the negative impact of complexities on the operations of the internal auditors. Reporting lines should be seamless and perhaps digitalized to enhance the work of internal auditors and their objectivity and independence. This will enable internal auditors to provide more effective assurance and consulting services and contribute to performance improvement.

Theoretically, our findings provide support for the agency theory, which posits that internal audit functions can help reduce agency costs and improve OP by providing assurance and monitoring management’s actions. The findings suggest that IAI is a critical factor in reducing agency costs and improving performance, which is a key tenet of the theory. Our findings also provide support for the stewardship theory, which suggests that internal audit functions can play a stewardship role by providing advice and guidance to management to improve OP. The findings suggest that internal audit functions can play a critical role in promoting OP and GA by providing assurance and consulting services. Furthermore, our findings highlight the importance of contextual factors, such as organizational complexity, in shaping the effectiveness of internal audit functions. This suggests that the agency and stewardship theories should be adapted to consider the specific contextual factors of the organization. Our findings also suggest that internal audit functions should be designed and implemented in a way that considers the specific needs and complexities of the organization.

Our findings also have significant social and economic implications. Effective internal audit functions can improve GA in organizations, which can lead to improved social outcomes and reduced corruption. Additionally, effective internal audit functions can contribute to improved OP, which can lead to improved economic outcomes and increased competitiveness. From an economic perspective, our findings suggest that effective internal audit functions can lead to cost savings and improved competitiveness. SOEs with effective internal audit functions are likely to be more competitive and better equipped to respond to changing market conditions. Our findings also demonstrate that effective internal audit functions can contribute to improved economic growth and development by improving GA, and promoting OP.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, we used a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to establish causality between variables. Future research should consider using longitudinal designs to examine the relationships between internal audit variables and performance improvement indicators over time. Secondly, we focused on a limited number of internal audit variables and organizational complexity indicators. Future research should examine other internal audit variables, such as internal audit competence and internal audit technology, and other organizational complexity indicators, such as environmental complexity and cultural complexity. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to other contexts and industries. Future research should consider examining the phenomenon in different contexts and industries.

Author Contributions

S.K.A. was involved in the conception and data collection and participated in the initial draft, focusing mainly on literature review. S.K.H. was involved in the methods and analysis of the data as well as the final approval of the version to be published. We agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it involved anonymous social science research with no collection of personal or health-related or sensitive information. Participants provided informed consent, and the research was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Variable Definition and Measurement

| Variable | Definition | Items for Measurement |

| IAE | The ability of the internal audit function to achieve its objectives, such as providing assurance on the effectiveness of risk management and internal controls (IIA, 2017). |

|

| IAQ | The quality of the internal audit process, including the skills and expertise of internal auditors, the adequacy of resources, and the use of best practices. |

|

| IAI | The ability of the internal audit function to operate independently and objectively, free from undue influence or interference (IIA, 2017). |

|

| IAR | The resources available to the internal audit function, including budget, staffing, and technology (IIA, 2017). |

|

| SC | The degree of differentiation and integration within an organization’s structure, including the number of departments, levels of hierarchy, and communication channels (Al-Twaijry et al., 2003; Daft, 2015). |

|

| PC | PC denotes to the degree of intricacy and variability in an organization’s business processes, including the number of processes, process interdependencies, and process changes (Hammer, 2007). |

|

| StC | The degree of interconnectedness and interdependence among an organization’s systems, including the IT infrastructure, organizational culture, and external environment (Senge, 2006). |

|

| OP | The extent to which an organization achieves its goals and objectives, while also considering the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations (Richard et al., 2009; Hilton et al., 2021). |

|

| GA | The systems, processes, and practices that ensure an organization is managed in a responsible and transparent manner, with clear lines of accountability and oversight (OECD, 2015). |

|

Source: Authors’ construction (2025). | ||

References

- Abbood, S. K., & Maaeni, S. S. A. (2022). The impact of added value of internal audit in the transparency and accountability: An applied research in a sample of the Ministry of Water Resources companies in Iraq. Studies of Applied Economics, 40(3), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z., Ayimpoya, R. N., & Namoog, S. (2025). Assessing the determinants and challenges of external auditors’ reliance on internal audit work in Ghana. African Journal of Empirical Research, 6(2), 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. B. (1994). The audit committee: A crucial role in safeguarding the interests of shareholders. Managerial Auditing Journal, 9(7), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Adurayemi, A. C., Tunde, O. A., & Ade, A. A. (2025). Internal auditing and organizational performance in Nigeria. International Journal of Sustainability in Research, 3(3), 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Twaijry, A. A., Brierley, J. A., & Gwilliam, D. R. (2003). The internal audit function in the Arabian Gulf: An empirical study. Managerial Auditing Journal, 18(5), 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- Appiah, M. K., Amaning, N., Tettevi, P. K., Owusu, D. F., & Opoku Ware, E. (2023). Internal audit effectiveness as a boon to public procurement performance: A multi mediation model. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M., & Azzone, G. (2009). Identifying internal audit effectiveness indicators. Managerial Auditing Journal, 24(7), 646–668. [Google Scholar]

- Awaah, F. (2025). Indigenous—Foreign culture fit and public employee performance: The case of Ghana. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 41(2), 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, S. M. (2018). Internal audit quality and organizational performance in Nigerian federal universities: The moderating effects of top management support [Ph.D. thesis, Universiti Utara Malaysia]. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, S. M., Ahmad, A. C., & Yusof, N. Z. M. (2018). Internal audit quality dimensions and organizational performance in Nigerian federal universities: The role of top management support. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 13(1), 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R. M., & Obel, B. (2018). Strategic organizational diagnosis and design: The dynamics of fit. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Lin, B., Lu, L., & Zhou, G. (2020). Can internal audit functions improve firm operational efficiency? Evidence from China. Managerial Auditing Journal, 35(8), 1167–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B. E., Newton, N. J., & Wilkins, M. S. (2021). Archival evidence on the audit process: Determinants and consequences of interim effort. Contemporary Accounting Research, 38(2), 942–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSO. (2017). Enterprise risk management—Integrating with strategy and performance. COSO. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R. L. (2015). Organization theory and design. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Deis, D. R., & Giroux, G. A. (1992). Determinants of audit quality in the public sector. The Accounting Review, 67(3), 462–479. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R. B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Sampling and purposive sampling. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Comparison of Convenience American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. P. (2015). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gunday, G., Ulusoy, G., Kilic, K., & Alpkan, L. (2011). Effects of innovation types on firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 133(2), 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M. (2007). The process audit. Harvard Business Review, 85(4), 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M. (2012). Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S. K., & Arkorful, H. (2021). Remediation of the challenges of reporting corporate scandals in governance. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 37(3), 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S. K., Arkorful, H., & Martins, A. (2021). Democratic leadership and organisational performance: The moderating effect of contingent reward. Management Research Review, 44(7), 1042–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S. K., Effisah, E. D., Khalid, A. A., & Nyarko, S. (2025). Tax compliance: A catalyst for business growth for indigenous contractors. Rajagiri Management Journal, 19(2), 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, S. K., Puni, A., & Yeboah, E. (2024). Leadership practices and job involvement: Does workplace spirituality moderate the relationship? Cogent Business and Management, 11(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIA. (2017). International standards for the professional practice of internal auditing. IIA. [Google Scholar]

- IIA. (2024). Global internal audit standards. Available online: https://www.theiia.org/en/standards/2024-standards/global-internal-audit-standards/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karikari, A. M., Tettevi, P. K., Amaning, N., Opoku Ware, E., & Kwarteng, C. (2022). Modeling the implications of internal audit effectiveness on value for money and sustainable procurement performance: An application of structural equation modeling. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, S. N., Bashir, A., Haseeb Mirza, M., & Abdullah, M. (2023). Impact of internal auditor on organizational performance: Mediation through independence of internal auditor and support of management team. Minhaj International Journal of Economics and Organization Sciences, 3(2), 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A., Hilton, K., Quaye, G., & Khalid, A. A. (2024). Relationship marketing and customer loyalty: The moderating effect of relationship duration, strength, and intensity. Journal of African Business, 26(3), 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseer, R. W., & Flayyih, H. H. (2021). Use a decision tree to rationalize the decision of accounting information users under the risk and uncertainty: A Suggested Approach. Estudios de Economia Aplicada, 39(11), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihret, D. G., & Yismaw, A. W. (2011). Internal audit effectiveness: Evidence from Ethiopia. Managerial Auditing Journal, 26(7), 615–635. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2015). G20/OECD principles of corporate governance. OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Lee, J. Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A., Hilton, S. K., Mohammed, I., & Korankye, E. S. (2022). The mediating role of innovative climate on the relationship between transformational leadership and firm performance in developing countries: The case of Ghana. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 43(3), 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quampah, D. K., Salia, H., Fusheini, K., & Adoboe-Mensah, N. (2021). Factors affecting the internal audit effectiveness in local government institutions in Ghana. Journal of Accounting and Taxation, 13(4), 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, P. J., Devinney, T. M., Yip, G. S., & Johnson, G. (2009). Measuring organizational performance: Towards methodological best practice. Journal of Management, 35(3), 718–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sawan, N., & Alzeban, A. (2013). The impact of internal audit function quality on the reliance of external auditors. Managerial Auditing Journal, 28(1), 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. (2003). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency. [Google Scholar]

- Shahini-Gollopeni, K., Rexha, D., & Hashani, M. (2022). The importance of internal audit in increasing performance of microfinance institutions: The case of the developing country. Corporate Governance and Organizational Behavior Review, 6(3), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinskog, D. J., Tjøstheim, D. B., & Kvamstø, N. G. (2007). A cautionary note on the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality. Monthly Weather Review, 135(3), 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tackie, G., Marfo-Yiadom, E., & Oduro Achina, S. (2016). Determinants of internal audit effectiveness in decentralized local government administrative systems. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(11), 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.