Abstract

Taking climate funds (e.g., the Green Climate Fund) as the main financial mechanism for providing funding to developing countries, this paper examines a long-term climate funding relationship between two parties—the rich country and the poor country. Conflicts between the rich and poor countries arise when determining (1) the size of climate funding that the rich country contributes to the poor country and (2) the funding allocation between climate adaptation and mitigation projects in the poor country. In addition, the rich country cannot be forced to commit contractual contributions to the poor country, and in each period, there is a probability that the countries can renegotiate the contract. This paper derives two main dynamic comparative–static results: (1) climate funds converge to the first-best in the long run, both in the size of climate funding in adaptation and mitigation projects, if and only if climate damage becomes sufficiently severe; (2) fewer renegotiations between the rich and poor countries make climate funding contracts more efficient, remedying inequality between the poor and rich countries. These results highlight how increasing climate damages and reducing the frequency of renegotiation can push climate funds closer to a first-best allocation, suggesting design principles for climate funding mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund.

1. Introduction

Climate finance plays a foundational role in coordinating international efforts to confront climate change. Through funds such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), high-income countries in the Global North commit multiyear financial assistance to enable low-income countries in the Global South to invest in mitigation and adaptation. Yet, the system is plagued by persistent inefficiencies that reflect a fundamental asymmetry in the benefits of these investments. Adaptation delivers immediate, local, and highly visible returns by reducing climate damages in the near-term in vulnerable countries, whereas mitigation generates delayed global public benefits whose gains are only weakly internalized by individual recipients. These benefit asymmetries help explain three recurring puzzles.

First, although the widely cited pledge to mobilize 100 billion dollars per year was finally met in 2022 after a two-year delay, the composition of these flows remains contested, with a heavy reliance on loans rather than grants (Bhattacharya et al., 2024; OECD, 2024). Second, climate finance is systematically skewed toward mitigation rather than adaptation, despite the heightened exposure of poor countries to immediate climate shocks (Climate Policy Initiative, 2025; UNEP, 2025). Third, climate finance commitments are frequently renegotiated, relabeled, or reversed following political and fiscal shocks in donor countries.

This paper proposes a dynamic contracting framework to explain why international climate finance remains persistently below stated ambitions and why its allocation across project types is repeatedly contested. The analysis asks the following: Will climate funds alleviate global inequality under climate change, and if so, under what conditions? The central contribution is to embed the adaptation and mitigation allocation problem in a long-horizon relationship with limited commitment and stochastic renegotiation. A donor country chooses a sequence of promised contributions and realized transfers, a recipient country allocates these transfers across climate investments, and in each period, the agreement can be renegotiated with a fixed probability due to political turnover, fiscal shocks, or changing priorities. Unlike explanations that emphasize asymmetric information, weak governance, or donor altruism, the mechanism here generates shortfalls and allocation distortions even under full information: when pledges are not fully enforceable, the prospect of renegotiation disciplines what can be credibly promised and weakens the ability to sustain first-best transfers over time.

The model delivers two main results. First, climate funds converge to the first-best in both the level and composition of financing if and only if realized climate damages become sufficiently severe, so that large and stable transfers are ex-post-optimal despite limited commitment. Second, stronger enforceability, interpreted as a lower renegotiation probability, strictly reduces the climate cost by keeping promised contributions and realized transfers closer to the first-best path. These results yield a simple set of design implications for climate funds: improve the credibility of multi-year pledges and reduce the scope for opportunistic renegotiation, complementing rather than substituting for monitoring and governance reforms.

The broader context is the interaction between the well-known climate externality and global inequality. Economists generally interpret climate change as a large-scale externality where emissions accumulate into a global stock, creating widespread damage not priced by markets. However, the incidence of these damages is highly unequal. Empirical studies consistently show that climate impacts fall disproportionately on lower-income economies, widening global income disparities (Burke et al., 2015; Dell et al., 2012; Diffenbaugh & Burke, 2019). While rich countries may eventually face large output losses under unmitigated scenarios (Kahn et al., 2021), poor countries face immediate threats to agriculture, labor productivity, and human health (Acevedo et al., 2020; IPCC, 2022b). This divergence creates a fundamental tension: the “Donor” (Global North) prioritizes mitigation to manage long-term global risks, while the “Recipient” (Global South) prioritizes adaptation and immediate economic development to survive local shocks.

Climate finance is the primary mechanism designed to bridge this gap, but its utilization faces significant economic friction. Theoretically, finance helps by subsidizing the “incremental cost” of low-carbon technologies (mitigation) and building resilience against shocks (adaptation). In practice, however, utilization is constrained by issues of additionality and absorptive capacity. Recent literature highlights that without strict enforcement, climate finance often displaces domestic spending rather than adding to it, or “leaks” into non-climate consumption due to the fungibility of funds (Bhattacharya et al., 2024). Furthermore, developing nations often lack the institutional capacity to absorb large capital inflows efficiently, leading to implementation delays and governance challenges (Climate Policy Initiative, 2025). This friction is exacerbated by the nature of the goods: mitigation is a global public good (benefiting the donor), whereas adaptation is a local private good (benefiting the recipient). This asymmetry creates an incentive for the donor to monitor strict mitigation compliance, while the recipient has an incentive to divert resources toward immediate local needs.

A central benchmark for these flows is the developed-country commitment to mobilize USD 100 billion per year (Eisenstadt et. al., 2021). OECD (2024) shows that realized flows fell short of this benchmark in the target years, reaching USD 83.3 billion in 2020 and USD 89.6 billion in 2021, and exceeded USD 100 billion for the first time only in 2022 (USD 115.9 billion). This pattern is noteworthy because the shortfall persists despite broad public recognition of climate needs, pointing to constraints on sustained delivery rather than a lack of awareness. Moreover, the apparent “success” in 2022 is qualified by composition: most finance was provided as loans, including non-concessional loans, rather than grants, raising concerns about debt burdens in the Global South. Even so, aggregate flows remain far below estimated needs. Bhattacharya et al. (2024) estimate that emerging markets and developing countries, excluding China, will require USD 2.4 trillion per year by 2030 to finance climate action.

Across data sources, climate finance is consistently tilted toward mitigation rather than adaptation (Maina & Parádi-Dolgos, 2024). OECD (2024) reports that in 2022, mitigation accounted for USD 59.9 billion of climate finance, compared with USD 32.4 billion for adaptation. UNEP (2025) emphasizes that the adaptation finance gap is widening, with current flows covering only a fraction of the estimated USD 310–365 billion needed annually by developing countries. This imbalance reflects the deeper incentive problem central to this paper: adaptation delivers immediate, local, and politically salient benefits to the recipient, whereas mitigation generates delayed global benefits. As climate risks intensify, the recipient’s marginal utility from adaptation rises, reinforcing the incentive to prioritize local resilience even if it undermines the donor’s global mitigation objectives.

These conflicting incentives make negotiation a central feature of climate fund governance. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is governed by a Board with equal representation from developed and developing countries, requiring consensus for decisions (GCF, 2025). However, this governance structure is vulnerable to shocks. Unexpected changes in the political or fiscal situation of donor countries often lead to the renegotiation of commitments, stalling project disbursement. It is observed that planned GCF projects are frequently delayed or discarded due to these incentive conflicts in the Board (GCF, 2018). This paper formally models this dynamic, showing how the threat of renegotiation undermines the credibility of long-term climate contracts.

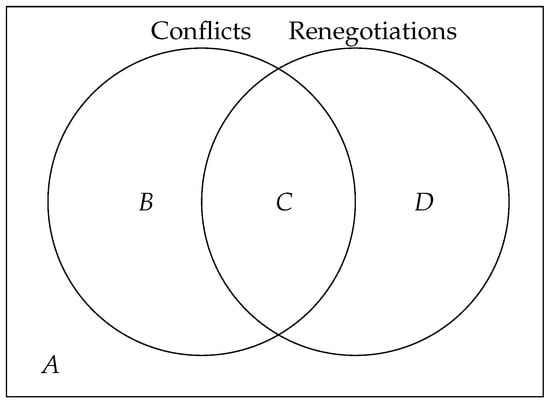

Figure 1 provides a conceptual overview of the two central frictions in international climate finance: conflicts of interest between rich and poor countries and the possibility of renegotiation over time. The horizontal dimension captures the extent of conflict regarding both the level of climate funding and its allocation between adaptation and mitigation, while the vertical dimension represents the frequency and institutional relevance of renegotiation. Together, these dimensions summarize the political and contractual constraints that shape long-term climate finance arrangements.

Figure 1.

Conflicts and renegotiations in climate finance. Letters denote: A = low conflict and rare renegotiation; B = high conflict and rare renegotiation; C = high conflict and frequent renegotiation; D = low conflict and frequent renegotiation. Source: Author’s own elaboration.

The left circle highlights conflicts of interest between rich and poor countries. These conflicts arise because donor countries bear the fiscal cost of climate finance, while recipient countries internalize most of the local benefits from adaptation and mitigation investments. Moreover, countries that are highly exposed to near-term climate damages, or that primarily internalize local benefits, have stronger incentives to prioritize adaptation projects with immediate and visible payoffs. By contrast, countries that internalize more of the global benefits from emissions reductions, or that face stronger pressure to deliver measurable emissions outcomes, have stronger incentives to prioritize mitigation.

In the absence of conflict, a rich country would optimally increase its climate funding contributions over time and allow the poor country to allocate funds flexibly to minimize present and future climate damages. In practice, disagreements over funding levels and the appropriate balance between adaptation and mitigation constrain feasible agreements and often necessitate tighter allocation rules.

The right circle represents the possibility of renegotiation. Renegotiation may be triggered by learning about realized climate damages and project effectiveness, by macroeconomic or fiscal shocks, by political turnover, or by shifts in domestic priorities. When renegotiation occurs, previously agreed funding levels and allocation rules may be revised; when it does not, countries continue to operate under the original agreement despite changed circumstances. I interpret renegotiation broadly as imperfect enforcement of past commitments rather than as a purely voluntary re-optimization. This interpretation also helps distinguish information-driven renegotiation, which updates terms in response to credible learning, from politically driven renegotiation, which reflects short-run shocks to bargaining power or willingness to honor commitments.

The four regions in Figure 1 illustrate distinct institutional environments. Region A represents an ideal benchmark with low conflict and rare renegotiation, corresponding to highly cooperative and well-enforced climate finance arrangements. In Region A, agreements are sustained not because circumstances never change, but because institutions can absorb change without reopening core commitments: monitoring and enforcement are strong, and any revisions that do occur are typically rules-based and tied to verifiable learning (e.g., scheduled reviews, independent evaluation, or transparent updating of needs and effectiveness). As a result, renegotiation in Region A is more likely to reflect adaptive updating rather than opportunistic political resetting.

Region B captures settings with substantial conflict but relatively strong enforcement, where agreements are contested yet largely upheld.

Region C depicts situations characterized by both high conflict and frequent renegotiation; this region is empirically the most relevant and closely reflects the current reality of international climate finance, where commitments are repeatedly revised, and enforcement is weak.

Finally, Region D reflects low-conflict environments in which renegotiation is frequent for reasons unrelated to fundamental disagreement, such as political cycles, administrative turnover, or procedural reauthorizations.

The model developed in this paper is designed to capture the dynamics of Region C. By allowing for persistent conflicts over funding and recurrent renegotiation, the framework highlights how limited commitment and imperfect enforcement shape long-run climate finance outcomes. In this sense, Region C represents not only the worst-case scenario in terms of cooperation, but also the most realistic benchmark against which alternative institutional designs and policy interventions—especially those that separate learning-based revisions from politically driven renegotiations—can be evaluated.

Corruption and asymmetric information between rich and poor countries are not the primary mechanisms emphasized in this paper. Instead, the model shows that distributional conflicts and renegotiation between rich and poor countries can jointly explain (i) an overall shortfall in climate finance and (ii) a persistent imbalance between adaptation and mitigation funding in recipient countries.1

Applying a theory of dynamic contracts (Kovrijnykh, 2013; Ljungqvist & Sargent, 2012), this paper examines a long-term climate-funding relationship between rich and poor countries, in terms of the size of funding and the allocation of funding between adaptation and mitigation projects.2

Section 2 discusses climate finance puzzles and related literature on adaptation–mitigation trade-offs, additionality and renegotiation, enforcement of international environmental agreements, and heterogeneous damages and carbon prices, and maps each to components of the model. Section 3 introduces the dynamic contract environment and characterizes the poor country’s first-best allocation. Section 3.5 presents the functional forms and calibration used for numerical illustration and analyzes the first-best benchmark. Section 4 characterizes the optimal recursive contract, derives the main comparative statics, and shows how convergence to the first-best depends on climate damage and the frequency of renegotiation. Section 4.4 uses a simulated transition path to illustrate the dynamics of promised contributions and climate-funding levels under the second-best contract. Section 5 interprets the results for the design of climate funds, and Section 6 concludes. Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C derive the optimality conditions for the first-best benchmark and the recursive contract and provide the proofs for all lemmas, propositions, and corollaries.

2. Literature Review

This paper is related to several strands of research on the scale of climate finance, the allocation of funding across adaptation and mitigation, the effects of climate policies (including carbon pricing), and the economic consequences of climate change. To connect these studies to the model, it is useful to organize them into three themes:

- Adaptation–mitigation mix;

- Renegotiation, additionality, and multiyear pledges;

- Enforcement in international environmental agreements and climate clubs.

2.1. Adaptation–Mitigation Mix

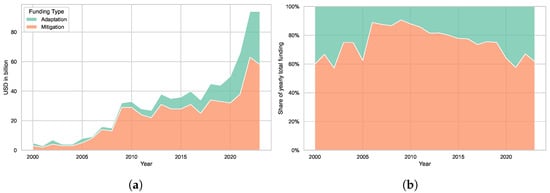

Fan et al. (2025) compile a comprehensive dataset on international public climate finance, covering bilateral and multilateral flows by recipient country, financial instrument, and climate objective. Their data show that adaptation finance remains persistently lower than mitigation finance, particularly for climate-vulnerable developing countries. Using their dataset, Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of international public climate finance for mitigation and adaptation over time. Panel (a) plots inflation-adjusted annual funding levels, showing that mitigation finance has consistently exceeded adaptation finance throughout the sample period. While both categories increase over time, mitigation funding grows more rapidly and exhibits larger absolute fluctuations, reflecting the scale and revenue-generating potential of mitigation projects. Panel (b) presents funding shares, highlighting that mitigation typically accounts for 60–80% of total public climate finance, with adaptation rarely exceeding one-third of annual flows.

Figure 2.

Yearly trend in international public climate finance, 2000–2023. (a) Funding levels for mitigation and adaptation. (b) Funding shares for mitigation and adaptation. Data are from Fan et al. (2025); Author’s visualization.

Kane and Shogren (2000) use an endogenous risk model to address the optimal balance between adaptation and mitigation policies with considerations such as the interactive effects of the two policies and how an increase in climate risk affects those interactive effects. Heal and Kriström (2002) discuss uncertainty about climate change in relation to adaptation and mitigation policies. Due to concerns about the uncertain effects of the two policies, adaptation can be a better policy option than mitigation because the adaptation option is more flexible than the mitigation option in response to new information about the effectiveness of each. Wilbanks et al. (2003) also discuss the optimal balance between adaptation and mitigation practice. They argue that adaptation and mitigation are complements: if mitigation achieves a desired level of climate risks, then adaptation can manage the resulting damage of climate change. In the Kane and Shogren (2000) framework, complementarity exists only when the marginal productivity of mitigation increases in the level of adaptation, and vice versa.

Pickering et al. (2015) analyze how contributor countries make decisions on climate finance, including the adaptation–mitigation balance, based on interviews with governmental officials. They argue that, regarding the adaptation–mitigation balance, there exist conflicts between agencies, such as the Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Development in one country, and they find that such conflicts influence countries’ decisions on climate finance. Brechin and Espinoza (2017) argue that the GCF’s 50:50 adaptation and mitigation target need not be efficient, and they recommend allocating a larger share to mitigation while still accounting for climate vulnerability in low-income countries. Wildowicz-Szumarska and Owsiak (2024) provide evidence that climate change significantly exacerbates income inequality, particularly in low-income economies and among the poorest populations globally, due to varying vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities.

In contrast to these contributions, which typically treat adaptation and mitigation choices within a single jurisdiction, my framework embeds the adaptation–mitigation allocation into a dynamic contracting problem between a donor (rich country) and a recipient (poor country). This allows for conflicts over the adaptation–mitigation mix to arise endogenously from asymmetric preferences and marginal climate costs in the two countries and connects the evolution of the mix to the enforcement of long-term climate finance promises.

2.2. Renegotiation, Additionality, and Pledges

This paper also examines how climate funds, as a climate finance mechanism, can be undermined by renegotiation shocks that disrupt funding decisions over time. Markandya et al. (2015) use a dynamic computable general equilibrium model to study the trade-off between economic growth and low-carbon targets in developed and developing economies. Their simulations show that mitigation contributions to the GCF can generate mutual gains for both groups of countries, which highlights the potential effectiveness of climate finance in an environment without renegotiation.

Stadelmann et al. (2011) and Kumar (2015) discuss problems in climate finance pledges in relation to additionality to development assistance. Many climate finance pledges are actually relabeled from preexisting development assistance. This “renamed” climate funding is usually not specifically for adaptation and mitigation projects. Stadelmann et al. (2011) suggest two baseline options—(1) “new sources only” and (2) “above pre-defined business as usual level of development assistance”—which potentially reduce the frequency of renegotiation in climate finance. Pauw et al. (2022) argue that much of the reported climate finance is not “new and additional,” but rather a relabeling of existing development aid, which undermines the principle of additionality. Bhandary et al. (2021) evaluates the practical implementation of climate finance policies and highlights the need for more efficient and equitable climate finance mechanisms. Kleinnijenhuis (2024) suggests that self-interest, beyond altruism, should drive increased climate finance contributions.

In my model, a random renegotiation shock captures these political and fiscal pressures that lead to relabeling of funds, failures to honor pledges, or ad hoc adjustments to previously agreed climate finance contributions. Thus, renegotiation risk provides a microfoundation for why climate funds may be unstable and why realized contributions fall short of announced targets.

2.3. Enforcement of International Environmental Agreements and Climate Clubs

This paper derives conditions under which climate funds work in the long run. Enforcement of international environmental agreements (IEAs) can be closely related to whether or not climate funds function well. Hoel (1991) shows that unilateral GHG emission reductions by one country may crowd out other countries’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Furthermore, Hoel (1991) finds that total GHG emissions may rise and global welfare may decline as a consequence of that leadership. The intuition behind these findings is that such unilateral actions do not change the behavior of other self-interested countries, which is consistent with conflicts and renegotiations in climate finance. Barrett (1994) shows that (1) a climate agreement needs to be self-enforcing, meaning that all countries should have no incentive to deviate from the agreement; and (2) a self-enforcing climate agreement may not be so effective, so the outcome of the agreement is similar to a non-cooperative outcome. Even if the condition for a self-enforcing climate agreement exists, the size of a stable coalition is small, which corresponds to the lack of funding in climate finance.

A punishment regime can be incorporated into climate funds. Nordhaus (2015) proposes a “climate club” in which participation is voluntary but backed by a top–down enforcement mechanism, typically trade sanctions against nonmembers. The sanctions are intended to make membership attractive, thereby encouraging broad participation and supporting substantial emissions reductions. Unlike the pessimistic result from Barrett (1994), he shows that a climate club achieves a large and stable coalition of climate agreement compared to the bottom-up approach that Barrett (1994) uses. Building on the idea of climate clubs, Carraro (2017) suggests climate clubs with rewards using green R&D and climate finance, as trade sanctions might not be politically feasible. Mason et al. (2017) analyze a self-enforcing climate treaty in a dynamic emissions game among countries. They show that an efficient level of mitigation can be sustained in subgame perfect equilibrium using a two-part punishment strategy that deters deviations and supports ongoing cooperation. Karp and Sakamoto (2018) study a dynamic model of IEAs with pre-play communication and belief updating, but without commitment devices, sanctions, or rewards. They find that even in the presence of a free-rider problem, countries can cooperate by forming not-too-pessimistic beliefs based on repeated negotiation, which is related to the effect of fewer conflicts in climate finance.

Relative to this literature, the present paper abstracts from explicit trade sanctions and formal punishment regimes. Instead, the model represents punishment in reduced form as an adverse renegotiation shock within the dynamic contract. This choice keeps the focus on how limited commitment and renegotiation risk, by themselves, constrain what can be promised credibly and shape the long run level and composition of climate finance.

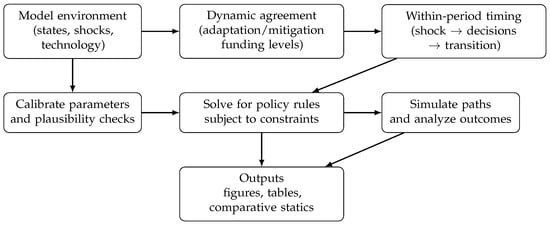

3. Model

Building on a dynamic contracting framework with limited commitment and stochastic renegotiation (e.g., Kovrijnykh (2013)), I study a long-term climate finance relationship between a rich country (the contributor) and a poor country (the recipient). In each period, the contributor makes transfers, and the recipient allocates them across adaptation and mitigation. The agreement is constrained by imperfect enforceability and may be renegotiated after political, fiscal, or institutional shocks. For readability, I present the model in three parts: (i) states and shocks; (ii) climate technology and law of motion; and (iii) preferences and prices. Figure 3 is a roadmap rather than an additional modeling assumption. It shows how the paper moves from the primitives (the state space, shocks, and technology) to the dynamic agreement and within-period timing, and then to the recursive solution. Arrows indicate the logical flow and dependence across steps from the primitives and timing to the recursive problem, and from the solved policy rules to simulated outcomes.

Figure 3.

Methodology overview: model environment, agreement structure, solution, and simulation. Arrows indicate the logical flow and dependence across steps: the model environment (states, shocks, and technology) and within-period timing jointly determine feasibility and incentive constraints; together, these define the recursive problem used to compute equilibrium policy rules. Calibrated parameters provide the quantitative inputs required for the solution. The resulting policy rules are then used to simulate first-best and second-best outcomes in this and the next section. Author’s own elaboration.

3.1. Environment and Basic Elements

3.1.1. States and Shocks

Let denote the history of climate (weather) states from date to t, where and , with and . Climate states are i.i.d. over time. In addition, each period features a renegotiation shock : with probability , (the agreement continues without renegotiation), and with probability , (the agreement is renegotiated). This reduced-form shock captures events such as elections, recessions, or shifts in domestic priorities that can disrupt previously agreed climate-finance terms.

Decisions can depend on past histories; formally, allocations may be written as and . For notational simplicity, I write and with this history dependence understood.

3.1.2. Technology and Climate

Let denote money-metric climate damages in the poor country, where is adaptation funding, is the global atmospheric GHG stock, and is the climate state. Mitigation funding affects next period’s stock through . The GHG stock evolves as

where is the baseline (pre-industrial) stock and is a reduced-form annual persistence parameter for deviations from baseline.

3.1.3. Dynamic Agreement

A dynamic agreement specifies, for each date , a climate-finance level and an allocation , satisfying

with determined before the period-t climate state is realized (so that current funding is not conditioned on ).

3.2. Timing

The state of the relationship at the start of period t is summarized by , where is the inherited promised contribution value, and is the current atmospheric GHG stock. The variable is a compact summary of relevant past events (including past shocks, renegotiations, and funding histories) and therefore governs the feasible set of current funding choices through promise-keeping.

Figure 4 summarizes the within-period timing of the dynamic climate finance contract. At the beginning of period t, the state variables are inherited from the previous period: is the current promised contribution (the continuation promise to the recipient) and is the GHG stock. Next, a renegotiation shock is realized, which determines whether the parties renegotiate the contract. Conditional on , the parties determine the next-period continuation promise : if renegotiation does not occur, the promise follows the enforcement branch (), whereas under renegotiation, it follows the renegotiation branch (). Given the resulting continuation terms, the recipient then chooses how to allocate current climate funding across adaptation and mitigation, with total funding . Adaptation affects contemporaneous damages through , while mitigation affects the evolution of the carbon stock through . Finally, nature draws the climate state , which pins down realized damages and closes period t. This timing makes clear that renegotiation and promise-setting occur before the allocation decision, and that climate damages are realized after choices are made, so incentives depend on how promised continuation values respond to renegotiation risk and to the evolution of .

Figure 4.

Within-period timing: renegotiation shock, funding/promise choices, and climate damages. The arrow indicates the sequence of events within period t (left to right), from the predetermined state , to the renegotiation shock , to negotiations over next period’s promise and current allocations , and finally to the realization of the climate state and damages . Author’s own elaboration.

3.3. Assumptions

Table 1 summarizes the assumptions used in the analysis. For ease of reference, they are grouped into (i) technology and damages; (ii) stochastic environment; and (iii) preferences and intertemporal trade-offs.

Table 1.

Model assumptions.

In the model, a (adaptation) and m (mitigation) are reduced-form policy effort aggregates rather than literal project expenditures. This abstraction is intentional because it isolates the allocation problem between actions that reduce contemporaneous climate damages and actions that slow the evolution of the GHG stock and hence future damages. The baseline specification also treats these efforts as operating contemporaneously and does not model the accumulation of long-lived adaptation or mitigation capital, which keeps the set of state variables small and makes the dynamic properties of the contract easier to interpret.

If adaptation and mitigation had stock effects, today’s finance would generate benefits that persist into future periods. Optimal funding would then depend more on past investment histories, because earlier spending would continue to influence current damages or abatement effectiveness. This persistence would tend to smooth funding paths and could shift the timing of spending, for example, making front-loaded finance more attractive when early investments yield long-lasting returns. It could also change the relative trajectories of adaptation and mitigation if one instrument is more durable than the other, although the main implications would be quantitative and would change the levels and the speed of transition rather than the underlying mechanisms.

The main contractual mechanism is provided in Section 3.1 and Section 4; however, it would remain the same and is unlikely to weaken. Limited commitment and stochastic renegotiation matter precisely because they create uncertainty about future transfer, and uncertainty is even more consequential when the returns to climate investments are long-lived and require sustained support. As a result, allowing for stock effects would generally strengthen the model’s dynamic implications: frequent renegotiation would distort incentives more strongly by discouraging durable investments, while stronger enforcement and fewer renegotiations would move outcomes closer to the first-best. Thus, stock effects would enrich the transitional dynamics and smoothing properties of the model, but they would not alter the key comparative statics driven by commitment and renegotiation frictions.

3.4. First-Best Benchmark

The first-best funding allocation is that it can freely fund its climate change projects as it desires. The first-best allocation for each level of G solves

subject to

is the multiplier on the GHG accumulation constraint in Equation (4). The following scenario is plausible in the first-best.

In the first-best, I impose the following convexity condition on the climate cost function. For all , the first-best climate cost, , is strictly convex:

where denotes the steady-state level of the GHG stock.

This scenario arises when the expected marginal climate damage of the GHG stock, , is sufficiently large relative to the marginal effectiveness of adaptation and mitigation. In this case, increases in G raise expected damages at an accelerating rate, and adaptation–mitigation investments cannot fully offset this acceleration. As a result, the shadow cost of the GHG stock increases more than proportionally, yielding a strictly convex first-best cost function. This global convexity of is the key condition underlying the paper’s main result: when climate damages are sufficiently severe, the dynamic benefits of sustained and stable climate funding transfers dominate their costs, making convergence to the first-best feasible under the optimal contract.

The properties of the first-best allocation are summarized in the following lemma.

Lemma 1

(First-Best Adaptation and Mitigation). The first-best level of adaptation funding, , never decreases with the level of the GHG stock G. The first-best level of mitigation funding, , strictly increases with the level of the GHG stock G. The first-best price of one unit of GHG emissions is a discounted marginal climate cost , which is also strictly increasing in G.

3.5. Calibration and First-Best Simulations

For numerical illustration, I adopt the following functional forms and parameterization for climate damages and net GHG accumulation :

where , , , and . The parameter values and admissible ranges for a and m are chosen so that and throughout the simulation. Adaptation and mitigation effectiveness enter through the logarithmic terms. The log specification captures diminishing marginal returns: early spending on adaptation and mitigation is relatively effective, while additional spending yields progressively smaller marginal reductions in expected damages and in the growth rate of the GHG stock.3 This formulation reflects the idea that low-cost, high-impact measures are implemented first, and it guarantees strictly positive but declining marginal effects, avoids implausibly large benefits at high spending levels, and improves numerical stability when funding varies over several orders of magnitude.

Given these functional forms, the first-best solutions for adaptation and mitigation funding are

where and .

The parameter values used in the simulations are summarized in Table 2. The pre-industrial level of the GHG stock is set to GtC (gigatons of carbon equivalent), following Mason et al. (2017), and the initial stock is GtC, corresponding to the observed atmospheric level in the year 2015.4 I model excess atmospheric greenhouse gases (or -equivalent) using the law of motion

where is a reduced-form annual persistence parameter for deviations from the baseline stock , rather than a literal physical “lifetime” of atmospheric . Following the integrated-assessment tradition (e.g., Mason et al. (2017); Newell and Pizer (2003); Nordhaus (1994); Nordhaus and Yang (1996)), I adopt an annual carbon decay rate of , so that . Under this calibration, the implied exponential half-life for deviations is years for deviations . I use this half-life calculation as a transparent calibration check against carbon-cycle assessments. IPCC (2021) emphasizes that atmospheric exhibits multiple residence times—ranging from years to many thousands of years—and that key carbon-cycle processes operate on timescales spanning decades to millennia. Accordingly, although a single parameter cannot match the carbon cycle’s full range of adjustment speeds, it can be calibrated to represent the long-lasting persistence of atmospheric carbon in an empirically plausible way.

Table 2.

Baseline parameter values.

The remaining parameters govern preferences, damages, technology, and uncertainty. The discount factor is set to , corresponding to a standard annual social discounting factor commonly used in climate-economics applications. The damage scale parameter A determines the overall magnitude of climate damages, while governs climate damage’s curvature with respect to the GHG stock and climate state. Together, these parameters control the convexity of damages without altering the qualitative structure of optimal policies. The parameter M represents the baseline (no-mitigation) emissions level: . Mitigation m reduces emissions relative to this baseline through the term , so a larger M shifts the entire emissions schedule upward.

The technology parameters and govern the cost and effectiveness of adaptation and mitigation investments. In particular, scales the overall cost of climate investment, while determines the curvature of abatement costs. Uncertainty in climate damages is captured through two climate states, indexed by and , with associated probabilities . The parameters and scale the severity of climate impacts across states, allowing the model to capture stochastic variation in damages while preserving analytical tractability. Equal state probabilities are imposed for simplicity; alternative probability assignments do not materially affect the qualitative results.

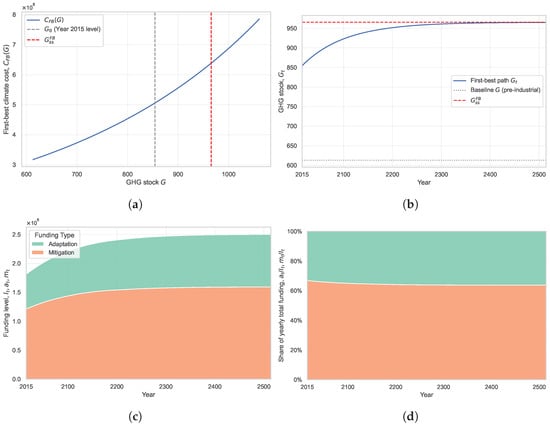

Panel (a) in Figure 5 shows that the first-best climate cost is increasing and globally convex in G over the range considered, so marginal climate cost rises as the GHG stock grows. Panel (b) plots the associated first-best transition path , which converges toward the steady state . I calibrate the parameters so that, in the first-best steady state, the GHG stock is GtC (453 ppm of ), which, according to prevailing climate science, is consistent with a 2 °C warming stabilization target (Athanassoglou & Xepapadeas, 2012).

Figure 5.

First-best benchmarks: (a) Climate cost . (b) Dynamics of GHG stock. (c) Dynamics of adaptation and mitigation funding levels. (d) Dynamics of adaptation and mitigation funding shares. Author’s own elaboration.

As G approaches , the optimal mitigation path becomes relatively flat. This follows from the first-order condition at the steady state:

together with two features of the calibration. First, along the transition, the shadow value of lowering next period emissions, , varies only slowly once is near its steady state, because changes little as the economy approaches convergence. Second, the emissions technology exhibits diminishing marginal effectiveness, so becomes small in magnitude when mitigation spending is already high.

Panels (c) and (d) report the implied composition of climate funding. Panel (c) plots simulated funding levels for adaptation and mitigation, which are model-based units and do not correspond to USD amounts. Panel (d) reports the corresponding shares. Panel (c) shows that both adaptation and mitigation spending rise during the transition, while panel (d) shows that the mitigation share declines modestly and the adaptation share rises as increases. This shift reflects the different nature of the two instruments in the model. Mitigation affects the future evolution of the stock and therefore generates persistent benefits through slower accumulation of G, whereas adaptation primarily reduces contemporaneous damages for a given G. When G is low or moderate, the persistent effect of mitigation dominates, so the first-best allocates most funding to mitigation. As G becomes high and damages become large, the marginal value of reducing current damages increases, so the planner gradually tilts the funding mix toward adaptation, even though mitigation remains the majority component in this calibration.

I choose parameter values so that, in the first-best steady state, adaptation represents about 40% of total climate funding. The purpose of this target is to place the benchmark allocation in a policy-relevant region that is both empirically plausible and informative for the model’s mechanism. In the data summarized in Figure 2, adaptation shares rarely exceed the 40% range, so 40% can be interpreted as an “upper bound” level of adaptation emphasis that is observed in practice. At the same time, the target is broadly consistent with the GCF’s stated aspiration to move toward a balance between adaptation and mitigation, providing a natural reference point for interpreting how the model’s allocations compare to a widely discussed policy objective.

Changing the target adaptation share would mainly rotate the first-best benchmark between adaptation and mitigation and therefore shift the levels of the two components in the numerical paths, but it would not overturn the model’s qualitative dynamics or comparative statics. A lower target (for example, 20 to 30%) would correspond to a calibration in which mitigation is relatively more attractive at the margin, because adaptation is effectively more costly or less productive, so simulated allocations would tilt toward mitigation along the transition and in the steady state. A higher target (for example, closer to 50% or above) would imply the opposite, raising the adaptation component throughout the simulated paths and lowering mitigation for a given state, with total funding changing only to the extent that the altered technology shifts the marginal value of climate spending. In all cases, the contract frictions operate through the same channels: promised contributions, enforceability, and renegotiation. So, the key numerical patterns described in Section 4.4 remain, while the adaptation and mitigation composition is rescaled around the chosen benchmark.

4. Theoretical Results

This section develops the paper’s theoretical mechanism linking limited commitment and renegotiation risk to persistent shortfalls in international climate finance. The key object is a recursive climate finance contract between a rich donor and a poor recipient. The contract is summarized by two state variables: the promised contribution value w, which captures the maximum present value of resources the rich country is willing to transfer under the agreement, and the GHG stock G, which determines expected climate damages in the poor country. The contract is enforced with probability and is renegotiated with probability , in which case continuation promises are stochastically weakened.

I first present the optimal recursive formulation and define the benchmark pair that characterizes when the contract implements the first-best allocation. I then impose a transparent pattern for the equilibrium climate cost that captures two empirically relevant forces: higher promised contributions reduce climate cost with diminishing marginal returns to climate funding, while a higher GHG stock raises climate cost at an increasing rate. Building on this structure, the subsequent results describe how partial commitment improves outcomes relative to business as usual (Proposition 1), why a higher enforcement probability strictly lowers the climate cost by reducing renegotiation driven promise erosion (Proposition 2), how promised contributions evolve differently under enforcement versus renegotiation (Lemma 2 and Proposition 3), and how total climate funding co-moves with the promise process (Proposition 4 and Corollaries 1–2). Finally, Proposition 5 characterizes convergence to the first-best in terms of the limiting behavior of , and Section 4.4 uses a reduced form simulation to illustrate how promise accumulation and renegotiation shocks jointly shape second-best (SB) transition dynamics.

4.1. An Optimal Recursive Contract

Contract theory studies the design of an incentive system such that one economic agent gets other economic agents to cooperate with him or her. A dynamic contract between two agents—the rich and the poor countries—can directly examine the long-term climate funding relationship. In the dynamic contract literature, the promised value is used as a state variable, which makes it possible to employ dynamic programming techniques to study contract problems with history dependence (Ljungqvist & Sargent, 2012, Part 5).

The rich and poor countries make an agreement on the size of climate funding to the poor country and how much to fund adaptation and mitigation projects, respectively. The long-term contractual climate funding relationship between the rich and poor countries is recursively formulated as follows:

where the branch value functions are

subject to, for each branch ,

where governs the severity of promise erosion under renegotiation. A lower value of k corresponds to more severe losses in continuation promises following renegotiation, whereas k close to one implies that renegotiation only modestly weakens future climate finance commitments. The parameter denotes the probability that the existing agreement is honored (the no-renegotiation branch), while is the probability that the agreement is renegotiated. In the no-renegotiation branch n, the countries implement the agreed-upon allocation and determine a continuation promise for the next period. The corresponding value function is Equation (10). In the renegotiation branch y, the countries re-enter negotiations and choose current funding levels , taking the renegotiated continuation promise as given. The branch value function is Equation (11).

In each branch , the agreement is subject to three sets of constraints. First, the law of motion for the GHG stock is given by Equation (12), where mitigation effort reduces the future GHG stock. Second, the promise-keeping constraint in Equation (13) requires that the rich country’s current funding outlays and future promised contributions do not exceed the promised value w. This constraint captures limited commitment by the rich country: the promised contribution value w summarizes the maximum present value of resources that the rich country is willing to transfer to the poor country under the agreement.

Renegotiation affects future promises through a stochastic reset of the continuation value. Specifically, when renegotiation occurs, the continuation promise is given by Equation (15), which captures the idea that renegotiation weakens the credibility of future climate finance commitments and introduces endogenous risk into the continuation of the agreement.

4.2. Properties of the Optimal Contract

The following definition considers a pair of greatest lower bounds for the promised contribution values and the corresponding GHG stocks that lead to the first-best allocation.

Definition 1.

A pair of values is such that

The set is the constrained Pareto frontier. For any , the rich country can be better off without making the poor country worse off by reducing w to , so the relevant frontier in the space is . In two dimensions, the frontier shifts upward in C as G rises. The point corresponds to the poor country’s first-best climate cost .

A plausible curvature pattern for the equilibrium climate cost function is the following: For all , suppose satisfies

- Higher promised contributions reduce climate cost, with diminishing marginal returns:

- Higher greenhouse gas stocks raise climate cost at an increasing rate:

- Promised contributions weakly reduce marginal climate damage:

Equation (18) implies that higher promised contributions reduce the climate cost, but the marginal cost reduction diminishes as promised contributions increase. When promised contributions are low, the contract directs scarce resources toward the most cost-effective adaptation and mitigation projects, such as basic infrastructure protection or readily available emissions reductions, because these options deliver large reductions in expected damages per unit of funding. As w increases, these high-return opportunities are exhausted, and further increases in promised contributions are directed toward projects with lower marginal effectiveness or toward relaxing intertemporal constraints rather than generating immediate damage reductions.5 Equation (19) is standard: climate damages typically accelerate with the stock of greenhouse gases. Equation (20) shows that higher promised contributions make it feasible for the poor country to undertake climate policies that are both more capital-intensive and more effective precisely in high-emissions states, such as large-scale mitigation or climate-resilient infrastructure. By enabling these actions when the GHG stock is high, greater promised contributions attenuate the marginal increase in climate cost associated with additional greenhouse gas accumulation.

4.3. Dynamics of Climate Funding

Under the optimal-contract scenario, the following results are obtained.

Proposition 1

(Commitment and the Quality of Equilibrium Funding).

- (i)

- If , then the equilibrium climate costs are for some .

- (ii)

- If , then the equilibrium climate costs are for some and .

In the case of no commitment, the rich country’s promises are not credible. Therefore, if the poor country expects the rich country to make a minimum amount of contribution under its minimal promise , its best response is to use as small a contribution as it wants. But as long as both countries at least partially commit to the contract, the contract equilibrium is weakly better for the poor country than the “business as usual” equilibrium, .

Proposition 2

(Fewer Renegotiations, More Efficient Contracts). For any given , the equilibrium climate cost is strictly decreasing in the enforcement probability ρ.

A higher enforcement probability reduces the likelihood of renegotiation and thereby strengthens the effective commitment embodied in the promised contribution value w. When renegotiation occurs, the continuation promise is stochastically reduced, which lowers expected future climate finance and weakens intertemporal smoothing of funding. An increase in mitigates this erosion of continuation promises by shifting probability mass toward states in which the existing contract is enforced.

As enforcement becomes more likely, the rich country can credibly sustain higher continuation promises without violating Equation (13). This relaxes the intertemporal resource trade-off faced by the contract and allows climate funding to be allocated more efficiently over time. In particular, higher expected continuation funding reduces the need for costly front-loaded distortions in adaptation and mitigation, leading to lower expected climate damages in the poor country.

Although a higher increases the expected present value of climate finance delivered by the rich country, it strictly lowers the poor country’s total expected climate cost. Consequently, is strictly decreasing in for all .6

Lemma 2

(Continuation Promises Under Enforcement and Renegotiation). The optimal is such that if Equation (13) binds, and otherwise.

Proposition 3

(Dynamics of Promised Contributions). Let with be a sequence of renegotiation shocks. Denote the sequences of the promised contribution value and the GHG stock by and , respectively, such that with . Then:

- (i)

- if .

- (ii)

- if .

Proposition 4

(Higher Promised Contributions Raise Total Climate Funding). Total climate funding is weakly increasing in w. Moreover, if Equation (13) binds at in branch n, then is strictly increasing in w.

Corollary 1

(Dynamics of Climate Funding). Let denote the sequence of total climate funding, where

For any , total climate funding is weakly increasing as a function of the promised contribution value , and strictly increasing for all whenever Equation (13) binds.

Lemma 2 and Proposition 3 characterize how the promised contribution value evolves under enforcement and renegotiation. Proposition 4 links these promise dynamics to the contract’s funding choices, and Corollary 1 follows immediately: since total climate funding is (weakly) increasing in w, any movement in promised contributions translates into a corresponding movement in funding.

The state variable w summarizes the maximum present value of resources the rich country is willing to transfer under the contract. A higher w relaxes Equation (13) and enlarges the feasible set of allocations in each branch. Because additional spending reduces expected climate damages and does not tighten any other constraint, the optimal contract never responds to an increase in w by lowering total climate funding.

Under enforcement, promised contributions do not decline. If Equation (13) is slack, the continuation promise is unchanged, so . If the constraint binds, implementing the optimal allocation requires raising the continuation promise, so and therefore whenever . In this sense, enforcement histories generate a gradual buildup of promised contributions.

Renegotiation instead produces downward adjustments. When , continuation promises are reset according to the renegotiation rule, reflecting an erosion of commitment when the existing agreement is not honored. Promised contributions therefore evolve asymmetrically over time: they weakly increase during enforcement but fall following renegotiation shocks.

Finally, when Equation (13) binds in the enforcement branch, the contract is locally resource-constrained. A marginal increase in w must then be absorbed through a higher continuation promise and or greater contemporaneous funding. Because renegotiation risk weakens continuation promises on average, part of the additional slack is optimally allocated to higher current spending, implying that increases strictly with w whenever Equation (13) binds. Combining this strict monotonicity with Proposition 3 implies that climate funding tracks the credibility of the arrangement along the equilibrium path: enforcement phases tend to raise funding through rising promises, while renegotiation episodes generate discrete funding declines through downward resets of w.

Corollary 2

(Total Funding Increases in the Overall Contract). The overall funding is weakly increasing in w, and strictly increasing whenever at least one branch has a binding Equation (13).

Corollary 2 follows from Propositions 4. Overall climate funding is a probability-weighted average of branch-specific funding levels. Since higher promised contributions weakly increase funding in each branch, they also weakly increase expected funding across branches. Strict monotonicity arises whenever additional promised resources relax a binding Equation (13) in at least one branch, inducing a strictly higher allocation to adaptation and mitigation in that branch. Consequently, larger promised contribution values translate into higher expected climate funding under the optimal contract.

Proposition 5

(Severe Damage and Convergence to the First Best). The optimal contract converges to the first-best allocation if and only if the state variables converge to , where is the minimal promised contribution value at which Equation (13) ceases to bind and is the corresponding steady state GHG stock under the first-best allocation.

Proposition 5 is not tied to a particular functional form for damages. It remains valid under alternative curvatures of the damage function so long as marginal damages in the upper range of G become sufficiently large, which raises the shadow value of climate finance and the continuation value of cooperation. Greater convexity or a more steeply increasing marginal damage schedule typically makes convergence easier because the contract reaches the region where the gains from sustaining funding are high enough that promised contributions optimally accumulate, eventually making Equation (13) slack. By contrast, if damages are too flat in G over the relevant range, the marginal value of additional funding rises only weakly, promised contributions grow slowly, and the economy may fail to enter the slack constraint region, preventing first-best implementation.

The stochastic structure of climate states plays an analogous role through the frequency and persistence of high marginal damage episodes. Convergence can occur with transitory shocks if sufficiently severe realizations occur with nontrivial probability, because rare but large shocks can push the system into states where the value of continued funding is high, and promises rise along enforcement histories. More persistent processes or heavier upper tails increase the time spent in high damage states and therefore strengthen the convergence mechanism. Conversely, if the climate state is thin-tailed and strongly mean-reverting so that severe damages are very unlikely or short-lived, the contract rarely visits the severe damage region, Equation (13) continues to bind, and convergence may fail. In sum, the key requirement is that the joint process for generates sufficiently frequent or sufficiently persistent states with high marginal climate damage, rather than a knife-edge assumption about curvature or a specific shock process.

4.4. Simulations of the Contract

The second-best dynamics in Figure 6 are generated using a reduced form simulation of the recursive contract that implements the paper’s characterization of the optimal contract, rather than by numerically solving the full second-best Bellman equation.7 This reduced form implementation isolates the central mechanisms of the contract, promise accumulation, and stochastic renegotiation, while avoiding the computational burden of deriving the full second-best value function .

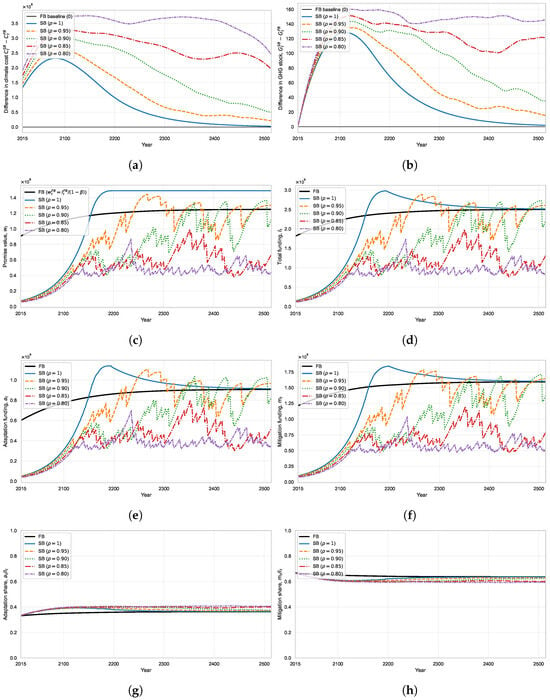

Figure 6.

Comparison of dynamics under the first-best and the second-best (SB) contract for , with initial total funding set to of the first-best level in 2015. (a) Difference in climate cost, . (b) Difference in GHG stock, . (c) Promised contribution value, . (d) Total funding, . (e) Adaptation funding, . (f) Mitigation funding, . (g) Adaptation share, . (h) Mitigation share, . Author’s own elaboration.

Figure 6 compares the first-best allocation with the second-best recursive contract along a simulated transition that begins in 2015 from a low initial funding level equal to 8% of the first-best benchmark, consistent with observed climate finance shortfalls. The 8% initial condition is derived from two empirical inputs. First, international public climate finance in 2015 was about USD $36 billion (Fan et al., 2025). Second, a benchmark for aggregate public finance needs in 2015 is calculated at USD $440 billion, based on contemporaneous scientific and policy assessments of required adaptation and mitigation support. On the adaptation side, UNEP (2016, Chapter 5)) estimated annual financing needs for developing countries of roughly $140–$300 billion by 2030; I adopt a conservative baseline of $140 billion from the lower end of this range. On the mitigation side, IEA (2015) estimated non-OECD investment requirements of approximately $1.2 trillion per year under the 450 scenario.8 Using a standard development finance leverage ratio of 1:3 to translate total investment needs into an implied public contribution that covers incremental costs and risk premia (i.e., public funds cover 25% of the total) (MDBs, 2015; UN AGF, 2010), the corresponding public component for mitigation is $300 billion. Combining the adaptation baseline of $154 billion with the mitigation public component of $300 billion yields a total requirement of $440 billion, so that provides a realistic calibration target for the initial funding gap. The parameter governs the persistence of the relationship, with a higher implying fewer effective renegotiation disruptions and therefore a second-best path that tracks the first-best more closely.

Panels (a) and (b) summarize the welfare and state distortions induced by limited commitment and renegotiation. Panel (a) shows that the second-best climate cost is above the first-best benchmark, and that this wedge is larger and more persistent when is lower. Panel (b) shows a parallel pattern for the GHG stock: the second-best path features a higher stock than the first-best, with the gap shrinking as rises. When is close to one, both gaps decline over time, indicating gradual convergence toward the first-best.

Panel (c) illustrates the key endogenous state variable in the contract, the promised contribution value . Across simulations, tends to build up as the relationship proceeds, but it exhibits discrete setbacks that reflect the contract’s exposure to renegotiation risk. Lower values of are associated with a lower and more volatile promise process, which in turn limits the extent to which the second-best contract can sustain funding levels near the first-best benchmark.9

Panels (d)–(f) translate these promise dynamics into funding outcomes. Total funding in panel (d) rises over time but is repeatedly pulled away from the smooth first-best path when promises are disrupted. Panels (e) and (f) show that both adaptation and mitigation move with these funding adjustments: periods of weaker promises are accompanied by sharp declines in both components, followed by gradual rebuilding as recovers. The departures from first-best funding are smallest when is highest, consistent with stronger effective enforcement of continuation promises.

Finally, panels (g) and (h) show that the composition of funding is comparatively stable. Adaptation and mitigation shares remain close to the first-best shares throughout the transition, and differences across are small relative to the differences in levels shown in panels (d)–(f). In this model calibration, renegotiation risk primarily distorts the overall scale of climate finance rather than generating large swings in the allocation shares.

5. Discussion

This section interprets the model’s dynamic comparative–static results in terms of real-world climate finance institutions and discusses policy implications. In particular, I relate the key model objects—the enforcement probability , the promised contribution w, and the erosion of the promised contribution —to observable features of climate funds such as the stability of GCF replenishment cycles, the legal strength of multi-year pledges, and what happens to vulnerable countries if donors walk away.

5.1. Why Is There a Lack of Commitment to the Contract?

Full commitment is unlikely for several reasons. First, when both countries are sufficiently self-interested, the rich and poor countries disagree about the preferred climate projects in the poor country. This preference gap makes it difficult to sustain a contract that fully reflects the poor country’s interests, because the rich country has limited incentives to commit to such an arrangement.

Second, it is not politically feasible to avoid renegotiation in the UN climate talks, due to each country’s sovereignty. In a sequence of the UNFCCC Conferences, the rich country can always walk away from what it promises the poor country, and the financial mechanism cannot force the rich country to keep its promise. Even though both countries have made an agreement for a huge contribution in the future, it can be reversed later. This possibility of renegotiation means a lack of commitment to the contract by the rich country. In the model, this shows up as a low probability of enforcement and frequent realizations of .

Third, the contract is usually incomplete in reality, which leads to renegotiation. Both countries might not be able to foresee all possible contingencies of climate states. In addition, the large transaction costs of writing and enforcing the contract can prevent a complete contract from being written.

Fourth, both countries can behave in an unpredictable way due to time-inconsistency and or bounded rationality. Time inconsistent countries may reverse earlier promises when future incentives change. Boundedly rational countries may also revise commitments because they cannot fully anticipate the dynamic consequences of their decisions in a long-horizon, uncertain environment. In particular, they may misforecast how current funding and mitigation affect future GHG stocks and damages, misperceive the likelihood of extreme climate or fiscal shocks, or rely on simplified rules of thumb that ignore intertemporal feedback effects. As new information arrives and the true costs and benefits become clearer, previously announced pledges may be reconsidered or renegotiated.

Lastly, political situations, macroeconomic business cycles, rich countries’ austerity plans, energy market booms and recessions, and changes in climate policy can cause both countries to renegotiate their original agreement. In the model, such events are represented through the renegotiation shock and the floor of the promise erosion k: when donors walk away from the prior promise, the poor country falls back on business-as-usual damage or alternative—often much more limited—sources of finance.

5.2. Design Principles for Climate Funds

The model suggests two broad design principles.

First, mechanism design for climate funds should raise the enforcement probability . In practice, this means lengthening commitment periods (for example, multi-year replenishment cycles with legal force), embedding climate finance in broader international agreements (such as trade arrangements or IMF programs) that make withdrawal costly, and improving transparency so that reneging on pledges carries reputational costs.

Second, efficiency improves when institutions make it harder for renegotiation to reduce previously promised support. In the model, renegotiation is treated as an external shock rather than as the outcome of an explicit disagreement payoff. It is captured by an exogenous reset of the continuation promise: when renegotiation occurs, the promised value is replaced by a new draw . Under the specification , the parameter k sets the minimum fraction of the current promise that survives renegotiation. A higher k means smaller downward jumps in when renegotiation occurs, which in turn reduces the distortions created by the risk that promises will be eroded.

5.3. Good and Bad Renegotiation

In the baseline model, renegotiation is treated as a friction that tends to reduce promised contributions w when the rich country’s participation constraint binds, moving the economy away from the first-best. This captures “bad renegotiation” episodes in which donors use political or fiscal shocks as justification for cutting transfers or relabeling existing development aid as climate finance. In reality, however, renegotiation can also be efficiency-enhancing. For example, if new information reveals that climate damages are worse than anticipated, or that mitigation technology has become cheaper, it may be desirable to renegotiate contributions upward and rebalance adaptation and mitigation portfolios.

Formally incorporating “good renegotiation” would mean allowing renegotiation to adjust the post-renegotiation promise in a state-dependent way, rather than treating renegotiation as a purely one-directional erosion of promises. For example, the renegotiation shock could capture not only political turnover but also learning about realized damages or about the costs and effectiveness of climate spending. In states where new information implies that climate action is more valuable or less costly than previously believed, renegotiation could increase promised contributions and thus accelerate convergence toward the first-best. A simple way to capture this idea is to let renegotiation raise the reset rule for . For example, in those states, the support of the uniform draw can shift from to with , so that may exceed the pre-renegotiation promise. This extension clarifies when flexibility mainly erodes commitments and when it instead allows the contract to adjust efficiently to improved information.

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper studies climate funds as a dynamic climate finance contract between a rich country and a poor country in the presence of limited commitment and renegotiation. The model delivers a sharp long-run characterization: the equilibrium funding path converges to the poor country’s first-best funding level if and only if climate damages in the poor country become sufficiently severe so that sustained high funding is jointly optimal and self-enforcing. When this severe condition fails, promised contributions remain vulnerable to downward renegotiation, and the relationship settles into an inefficient funding path shaped by how much promises are cut in renegotiation and by the strength of enforcement.

The model highlights several practical levers for improving the performance of climate funds. First, policies that reduce the frequency of opportunistic renegotiation increase efficiency by protecting promised contributions. In the model, such reforms operate by raising the enforcement probability and by increasing the cost of deviating from agreed commitments. Second, strengthening the poor country’s institutional and fiscal position improves its continuation payoff, which can be interpreted as a better outside option (a higher continuation value associated with ). This shifts the renegotiation frontier and supports higher equilibrium promised contributions w. Third, commitment devices that lengthen effective commitment periods and make funding cuts more difficult (for example, multi-year appropriation rules, rule-based replenishment, or credible penalties for shortfalls) move the equilibrium allocation toward the first-best benchmark, especially in states where damages are rising (higher s or a higher likelihood of high damage states).

The analysis intentionally abstracts from several features that matter in practice. The contract is stylized as a bilateral relationship, while real climate funds involve multiple donors, multiple recipients, and intermediary institutions that may create additional strategic interactions. The enforcement probability and the outside option process are treated as reduced form objects; endogenizing them through domestic politics, fiscal shocks, or institutional design would strengthen the empirical mapping. The framework also focuses on renegotiation that weakens commitments. A natural extension is to incorporate learning processes about damages, abatement costs, and the effectiveness of adaptation and mitigation, together with heterogeneous climate costs across countries. Renegotiation could then depend on the state. State-contingent renegotiation allows contributions to increase when updated information or widening cost differentials make additional finance more valuable, while funding cuts are restrained when they mainly reflect short-run political or fiscal pressures.

Overall, the model interprets under-provision in climate finance as a dynamic commitment problem rather than as a purely technological or informational limitation. An efficient long run funding path emerges when climate damages become sufficiently severe that continued support can be justified and enforced within the contract; otherwise, renegotiation risk constrains what can be promised. This perspective implies that improving climate finance requires not only mobilizing more resources but also building institutions that strengthen enforcement and raise the recipient’s continuation value, so that high promised contributions can be maintained over time. A direct policy implication is that reforms should prioritize credible multi-year commitment and enforcement mechanisms, not only larger headline pledges.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All scripts and associated datasets are publicly available in the GitHub repository at https://github.com/bcecon/climate-finance-contract (accessed on 13 January 2026). No additional data were generated beyond those provided in the repository.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT 5.2 (OpenAI) for assistance with language editing, code debugging, and figure formatting. The author has reviewed and edited all generated content and takes full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CES | Constant Elasticity of Substitution |

| Carbon Dioxide | |

| FB | First-best |

| GCF | Green Climate Fund |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GtC | Gigatons of Carbon |

| IDB | Inter-American Development Bank |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IEA | International Environmental Agreement |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| IPCC AR6 | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report |

| MDB | Multilateral Development Bank |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| ppm | Parts Per Million |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation Plus |

| SB | Second-best |

| UN AGF | United Nations High-level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| USD | United States Dollar |

Appendix A. Characterizations of the First-Best Allocation to the Poor Country

This section characterizes the first-best allocation to the poor country by deriving the associated optimality conditions.

The Lagrangian associated with problem in Equations (3)–(5) is

where is the multiplier on Equation (4), and and are the multipliers associated with the non-negativity constraints.

The necessary first-order conditions for an interior optimum are as follows:

Applying the envelope theorem yields the envelope condition

The complementary slackness conditions associated with the nonnegativity constraints are

Appendix B. Characterizations of the Optimal Contract

This section characterizes the optimal dynamic contract under limited commitment. In each contractual branch, the planner chooses adaptation and mitigation expenditures subject to promise keeping, feasibility, and the law of motion of the greenhouse gas stock.

Appendix B.1. Branch n

In branch n, both countries choose . The associated Lagrangian is

where is the multiplier on Equation (13), is the multiplier on Equation (12), and and are the multipliers associated with the lower bounds on adaptation and mitigation.

The first-order conditions for branch n are

The complementary slackness and feasibility conditions are

Applying the envelope theorem, the envelope conditions for branch n are

where .

Appendix B.2. Branch y

In branch y, both countries choose , taking the continuation promise as given.

The corresponding Lagrangian is

where and are the multipliers on Equations (12) and (13), respectively.

The first-order conditions for branch y are

The complementary slackness conditions are

Because w affects both Equation (13) and the continuation value through , where , the envelope condition with respect to w is

while the envelope condition with respect to the greenhouse gas stock is

Finally, combining both branches using yields the overall envelope conditions

Appendix C. Proofs

Appendix C.1. Lemma 1

Appendix C.2. Proposition 1 and Proposition 2

These follow directly from the definitions of , C, and the properties of the punishment equilibrium and enforcement probability discussed above.

Appendix C.3. Lemma 2

Let be optimal for state .

- Step 1 (Slack case). Suppose Equation (13) is slack, soBecause the continuation promise enters the objective only through the continuation term and (in branch n) does not feed back into any other constraint besides Equation (13), can increase without violating feasibility as long as Equation (A29) remains satisfied. If the optimal policy selected , then there exists such that still satisfies Equation (A29). Since is weakly decreasing in w (a larger promise relaxes future promise keeping and cannot increase the minimal cost), raising weakly lowers the objective, contradicting optimality. Hence, under slackness, the optimizer sets the continuation promise at the upper bound: .

- Step 2 (Binding case). Now suppose Equation (13) binds:Since and with , we have . Rearranging Equation (A30) yieldsWith , . Therefore , implying whenever Equation (13) binds.

Appendix C.4. Proposition 3

Fix any date .

(i) Enforcement. If , then . If Equation (13) is slack at , Lemma 2 implies . If Equation (13) binds, Lemma 2 implies . Therefore, in all cases, when .

(ii) Renegotiation. If , then by assumption with . Hence, .

Appendix C.5. Proposition 4

Fix a branch and a GHG stock G. Binding constraint in Equation (13) is

for any . Thus

Suppose w increases by . Then, we have

Thus

Therefore, strictly increases with .

Appendix C.6. Corollary 1