Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming accounting by automating cognitive tasks and redefining mechanisms of governance and risk control. This study examines how AI operates as an intelligent control system—one that substitutes manual accounting procedures while enhancing transparency, internal control, and fraud detection. Integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT), the research develops a behavioral–organizational framework linking perceived usefulness, ease of use, AI literacy, technology readiness, social influence, and facilitating conditions to AI adoption and perceived substitution benefits. A structured survey was administered to accounting students and practitioners in Northern Italy (n = 185) and analyzed through reliability tests and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results show that AI literacy, facilitating conditions, and social influence significantly drive adoption intention, while perceived substitution benefits fully mediate the relationship between adoption and governance outcomes. The findings demonstrate that AI adoption enhances governance and risk management effectiveness by functioning as an intelligent control mechanism. The study introduces the AI-to-Control (A2C) Blueprint to guide responsible integration of AI into accounting systems, reframing AI adoption as a structural evolution in corporate governance rather than a mere technological upgrade.

1. Introduction

The accounting profession is experiencing a profound structural transformation as digital technologies increasingly redefine the boundaries between human judgment and algorithmic intelligence. Among these technologies, artificial intelligence (AI) stands out as the most disruptive, capable of automating not only repetitive procedures but also advanced cognitive tasks such as interpretation, anomaly detection, and decision support. Unlike earlier phases of digitization that focused primarily on efficiency gains, AI introduces adaptive learning and reasoning. As a result, it reshapes how accountants interact with data, exercise control, and uphold governance standards (Leitner-Hanetseder et al., 2021). Its implications for corporate governance, internal control, and the prevention of earnings manipulation are far-reaching, as algorithms begin to underpin assurance and compliance processes once dependent solely on human expertise. Consequently, accounting is moving from manual to intelligent practice, where analytical reasoning and oversight functions are increasingly performed by intelligent systems.

Despite the promises of AI, its adoption within accounting remains uneven across countries, industries, and organizational sizes. Large audit and consulting firms have embraced AI-driven auditing, predictive analytics, and fraud detection, while smaller entities and educational institutions often continue to rely on traditional methods. This asymmetry raises critical questions about perceived usefulness, ease of use, and readiness for integrating AI into established workflows. Moreover, as AI begins to automate oversight and verification functions, its influence extends beyond operational efficiency to touch upon accountability, transparency, and risk management quality (Almufadda & Almezeini, 2022). Understanding these dynamics is especially relevant under growing regulatory scrutiny and ethical debates over algorithmic decision-making.

AI applications in accounting—from automated journal-entry validation to natural-language analysis of financial disclosures—aim to reduce human error and accelerate reporting cycles. Yet these innovations challenge professional identities grounded in judgment, independence, and fiduciary responsibility (Ahmad, 2019).

In this study, AI is conceptualized as an intelligent control system. Rather than treating AI as a generic automation technology, we focus on socio-technical configurations in which algorithms continuously scan transactions, flag anomalies, and generate auditable traces that support human judgment. From this control-oriented perspective, AI partially substitutes manual verification and monitoring activities while expanding the organization’s information-processing capacity. This conceptualization motivates the link we draw between individual adoption constructs and governance outcomes and anchors the empirical analysis in the broader debate on algorithmic forms of internal control.

The resulting tension between innovation and control defines an unresolved research gap: can AI truly substitute, rather than merely support, conventional accounting practices—and how does this substitution affect perceptions of governance and risk management (Odonkor et al., 2024). Existing research in advanced economies links AI to analytical improvements and enhanced assurance quality but also warns of new sources of ethical and operational risk. In the European mid-market context, particularly Italy, adoption patterns are shaped by institutional conditions, educational readiness, and organizational culture. The Italian setting offers an ideal testbed: a strong professional tradition intersects with increasing digitalization among universities and small-to-medium enterprises, allowing investigation into how accountants and students evaluate AI’s substitution potential within entrenched governance frameworks.

To address these questions, this study integrates two complementary theoretical perspectives. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) explains behavioral intention to adopt technology through perceived usefulness and ease of use, while the Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT) (Galbraith, 1973) conceptualizes technology adoption as an adaptive response to environmental complexity. Combined, they frame AI adoption as both an individual behavioral choice and an organizational adaptation mechanism. The study introduces perceived substitution benefit—the belief that AI can effectively replace manual accounting processes—as a bridging construct linking behavioral intention (TAM) to governance and risk outcomes (OIPT). This integrated approach connects acceptance determinants with the organizational consequences of AI adoption, offering a multi-level perspective on intelligent control in accounting.

The current literature on digital transformation provides substantial evidence on adoption drivers but offers limited empirical exploration of how AI’s substitution effects translate into governance outcomes. Prior studies have largely examined technical implementation or educational attitudes without assessing the influence of AI on internal control reliability, fraud detection, or earnings-management prevention. Moreover, comparative evidence from Southern Europe remains scarce. This research addresses these gaps through survey-based evidence from Italy, employing partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze the interrelations between behavioral adoption constructs, substitution perceptions, and perceived governance outcomes. The findings extend TAM by introducing substitution benefit as a mediator between AI adoption and governance quality and enrich OIPT by showing how AI strengthens information-processing capacity, thereby functioning as a governance mechanism rather than a mere efficiency tool.

The integration of TAM and OIPT is theoretically justified because the adoption of AI in accounting simultaneously reflects an individual behavioral decision (captured by TAM) and an organizational response to information-processing requirements (captured by OIPT). TAM explains the cognitive determinants driving intention to use AI, while OIPT describes how organizations deploy technologies to reduce uncertainty and enhance control reliability. In the accounting context, AI adoption cannot be explained by behavioral perceptions alone, nor by organizational adaptation in isolation; rather, both levels jointly determine substitution and governance outcomes. This conceptual alignment has been recognized in recent accounting technology literature (Roos et al., 2025), supporting the appropriateness of the combined framework.

This study makes two distinct sets of contributions.

First, on the theoretical side, it integrates the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT) into a single behavioral–organizational framework for AI in accounting, introduces perceived substitution benefit as a mediating construct linking AI adoption to governance and risk management outcomes, and conceptualizes AI as an intelligent control system rather than a generic automation tool. In doing so, the model connects individual-level adoption drivers with organization-level control structures and enriches ongoing debates on how AI reconfigures internal control and audit processes.

Second, on the practical side, the study provides survey-based evidence from Northern Italy on how accounting students and professionals evaluate AI’s substitution potential and its perceived implications for governance, internal control, and earnings-management risk. It also proposes the AI-to-Control (A2C) Blueprint as a design and policy tool for educators, professional bodies, and managers who seek to embed AI responsibly into accounting workflows and governance architectures.

For clarity, the core contribution of this study lies in conceptualizing artificial intelligence as an intelligent control in accounting and empirically demonstrating that perceived substitution benefits mediate the relationship between AI adoption and governance and risk management outcomes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and formulates hypotheses; Section 3 describes the research design and analytical methods; Section 4 presents the empirical results; Section 5 discusses theoretical and practical implications; and Section 6 concludes with policy recommendations and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Literature Synthesis (AI, TAM, OIPT)

Artificial intelligence (AI) is redefining accounting by transforming labor-intensive, rule-based procedures into intelligent, data-driven systems capable of prediction, reasoning, and decision support. The latest multivocal literature review by Roos et al. (2025) shows that the success of AI implementation depends on adequate IT infrastructure, data quality, regulatory compliance, and employee upskilling. Their review concludes that AI contributes to efficiency gains and higher analytical accuracy in tasks such as invoice processing, anomaly detection, financial forecasting, and tax compliance. In parallel, Odonkor et al. (2024) emphasize that AI improves accuracy, timeliness, and fraud detection in financial reporting, although high costs, skills shortages, and data-governance concerns still limit adoption. Collectively, these studies illustrate how AI has evolved from a simple automation tool into a mechanism for governance, transparency, and accountability. Earlier research also points to the complementary role of emerging technologies such as robotic process automation (RPA), cloud computing, and blockchain. Leitner-Hanetseder et al. (2021) highlight that AI can extend RPA by incorporating adaptive learning, thereby automating cognitive functions and improving financial-reporting reliability. Kureljusic and Karger (2023) further identify predictive analytics and machine-learning models as essential tools for modern accounting forecasting, stressing that data-driven approaches improve precision in audit planning and valuation. These findings confirm that AI integration enhances both operational performance and the strategic dimension of accounting.

At the individual level, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) and its later extensions—TAM2, UTAUT, and UTAUT2—remain the most robust frameworks for predicting technology adoption. The 2025 Vietnamese study by Bui et al. demonstrates that perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), AI literacy (AL), technology readiness (TR), social influence (SI), and facilitating conditions (FC) are all significant determinants of AI adoption among accounting students. Using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), their model revealed that SI strengthens the relationship between PEOU and adoption, implying that peer and institutional encouragement accelerate behavioral change. This behavioral evidence aligns with the findings of Damerji and Salimi (2021), who showed that technology readiness and user perceptions mediate AI adoption in accounting. Sudaryanto et al. (2023) confirmed that TR and digital competence are key antecedents of PU and PEOU in technology adoption models. These studies collectively suggest that AI adoption in accounting depends not only on technical availability but also on cognitive and social factors that influence individual intention. AI literacy, defined as the ability to understand and apply AI principles in decision-making (Ng et al., 2021), has emerged as a powerful predictor of acceptance. Dai et al. (2020) argue that AI literacy fosters readiness for the AI age by increasing confidence in algorithmic interpretation, while Chen et al. (2022) found that AI literacy enhances self-efficacy and perceived usefulness. In accounting education, incorporating AI literacy into curricula improves future accountants’ capability to work with data analytics tools (Kong et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021). Therefore, behavioral acceptance and competence development are intertwined in shaping AI integration.

While TAM explains technology use at the individual level, the Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT) provides an organizational lens by linking information-processing capacity with environmental uncertainty (Galbraith, 1973). OIPT posits that organizations adopt richer information systems to handle complex data and improve decision quality. Recent evidence from Abu Afifa et al. (2024) in Vietnam shows that digital transformation and transformational leadership (TL) both significantly influence AI integration in accounting (Al Mashalah et al., 2022). Their PLS-SEM results (β_DT → AI = 0.42; β_TL → AI = 0.45; R2 = 0.66) reveal that transformational leadership moderates the relationship between digital transformation and AI adoption, amplifying organizational adaptation (Burmeister et al., 2020). These results confirm that AI can act as a governance instrument—improving transparency, internal control, and accountability—when supported by digital infrastructure and leadership commitment. This perspective is consistent with global research linking digital transformation to information-processing enhancement. Singh et al. (2021) demonstrate that digital transformation improves flexibility, integration, and efficiency in manufacturing contexts. Similarly, Dubey et al. (2020) found that big data analytics and AI collectively boost operational performance by aligning information flows with decision needs (Belhadi et al., 2024). From an OIPT standpoint, AI functions as an advanced processing system that transforms accounting data into predictive insights, reducing uncertainty in governance and risk management.

A new dimension gaining traction is the perceived substitution benefit (PSB)—the belief that AI can replace manual accounting processes while improving governance outcomes. Roos et al. (2025) identify PSB as a critical bridge between technological adoption and process reengineering, emphasizing that AI can substitute repetitive, data-intensive tasks such as reconciliations and invoice matching while augmenting human oversight. In practice, PSB reflects a shift from augmentation to intelligent substitution, where AI complements rather than competes with professional judgment (Lehner et al., 2022; Odonkor et al., 2024). Empirical studies show that substitution perceptions directly affect behavioral intention. Bui et al. (2025) note that students with higher AI literacy perceive stronger substitution benefits, believing that AI can automate low-value operations and enhance decision quality. These perceptions correspond to the finding by Abu Afifa et al. (2024) that organizational readiness and leadership vision determine whether substitution produces efficiency without compromising ethical accountability. Consequently, PSB acts as a mediator connecting TAM variables (PU, PEOU) with OIPT outcomes (governance and risk control).

AI’s impact extends beyond efficiency into the domain of governance and risk management (El Hajj & Hammoud, 2023). Numerous studies identify AI as a governance enabler that strengthens internal control systems and reduces the scope for earnings manipulation (Zhang et al., 2023; Schweitzer, 2024). Noordin et al. (2022) demonstrate that AI tools enhance audit quality by improving data reliability and fraud detection. Peng et al. (2023) link AI adoption to several Sustainable Development Goals by enhancing transparency, compliance, and decision-making speed. Nevertheless, ethical and regulatory issues persist. Lehner et al. (2022) caution that algorithmic bias and opacity may threaten trust in financial reporting, while Pierotti et al. (2024) stress that data-protection and auditability mechanisms are prerequisites for responsible AI use. These findings underscore that AI’s governance potential must be balanced with ethical oversight, clear accountability, and professional skepticism. The convergence of AI ethics, governance, and information assurance forms the foundation of the intelligent control framework proposed in this study.

2.2. Literature and Research Gaps Synthesis

Across these strands of research, three broad conclusions emerge. First, AI and related digital technologies (such as robotic process automation, predictive analytics, and cloud-based platforms) have pushed accounting beyond rule-based automation toward data-driven, learning systems that support prediction, anomaly detection, and continuous auditing, thereby strengthening internal control and risk management. Second, behavioral studies grounded in TAM and its extensions show that perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, AI literacy, technology readiness, social influence, and facilitating conditions are central drivers of individual intention to adopt AI-based tools in both accounting education and practice. Third, organization-level research inspired by OIPT demonstrates that digital transformation and leadership support enable firms to leverage AI for transparency, governance, and performance improvements (Govindan et al., 2022).

Despite this progress, important gaps remain. Existing TAM-based studies rarely examine how adoption intentions translate into concrete governance outcomes such as fraud detection, earnings-management constraints, or internal-control quality, and substitution perceptions are typically treated implicitly rather than as a formal construct. OIPT-based research, in turn, tends to focus on operational performance or digital transformation in general, without explicitly theorizing AI as an intelligent control system embedded in accounting architectures. Empirical evidence from Southern European settings, and from Italy in particular, is also limited. The present study addresses these gaps by proposing an integrated TAM–OIPT model in which perceived substitution benefit links AI adoption to governance and risk outcomes and by testing this model empirically with respondents from Northern Italy.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Building on the preceding literature synthesis, the hypotheses are developed to reflect the dual nature of AI adoption in accounting. At the individual level, constructs derived from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) explain behavioral intention to use AI tools. At the organizational level, Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT) explains how such adoption translates into governance and risk management outcomes. In particular, perceived substitution benefit captures whether AI is viewed as capable of replacing manual control activities, thereby linking behavioral intention with perceived governance effects.

Based on the integrated TAM–OIPT framework and prior empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H1a.

Facilitating conditions (FC) are positively associated with perceived usefulness (PU).

H1b.

Facilitating conditions (FC) are positively associated with perceived ease of use (PEOU).

H1c.

Facilitating conditions (FC) are positively associated with AI adoption intention (Bui et al., 2025; Andrews et al., 2021).

H2a.

AI literacy (AL) is positively associated with perceived usefulness (PU).

H2b.

AI literacy (AL) is positively associated with perceived ease of use (PEOU).

H2c.

AI literacy (AL) is positively associated with AI adoption intention (Dai et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Bui et al., 2025).

H3a.

Technology readiness (TR) is positively associated with perceived usefulness (PU).

H3b.

Technology readiness (TR) is positively associated with perceived ease of use (PEOU).

H3c.

Technology readiness (TR) is positively associated with AI adoption intention (Damerji & Salimi, 2021; Sudaryanto et al., 2023).

H4.

Perceived usefulness (PU) positively influences AI adoption intention (Davis, 1989; Bui et al., 2025).

H5.

Perceived ease of use (PEOU) positively influences AI adoption (Damerji & Salimi, 2021).

H6a.

Social influence (SI) positively affects AI adoption intention (Chatterjee et al., 2023; Andrews et al., 2021).

H6b.

The relationship between PEOU and AI adoption is stronger under high social influence (Bui et al., 2025).

H7.

Perceived substitution benefit (PSB) mediates the relationship between AI adoption and governance/risk management outcomes (Roos et al., 2025; Odonkor et al., 2024; Lehner et al., 2022).

H8.

Perceived substitution benefit (PSB) positively affects perceived governance and risk management outcomes (Abu Afifa et al., 2024).

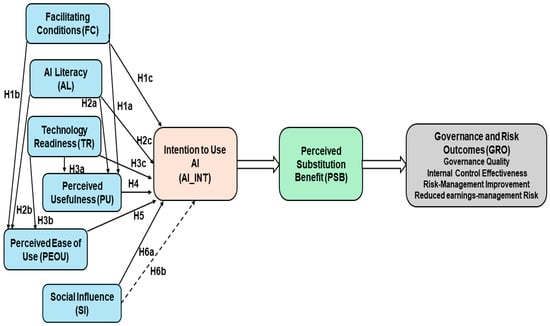

Drawing on the reviewed literature, the conceptual model integrates TAM’s behavioral constructs—PU, PEOU, AL, TR, FC, and SI—with OIPT’s organizational outcomes. The model posits that AI adoption mediates the influence of cognitive and environmental factors on governance and risk management outcomes, while perceived substitution benefit acts as a mechanism translating behavioral intention into governance impact. The framework shown in Figure 1, reflects the dual nature of AI in accounting: a behavioral innovation process at the individual level and an organizational adaptation mechanism enhancing control and transparency.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model. The model depicts behavioral determinants derived from the Technology Acceptance Model (PU, PEOU, AL, TR, FC, SI) influencing intention to use AI (AI_INT). Perceived substitution benefit (PSB) mediates the relationship between AI adoption intention and perceived governance and risk outcomes (GRO). Governance and risk outcomes are operationalized as a single latent construct capturing perceived governance quality, internal control effectiveness, risk management improvement, and reduced earnings-management risk. Solid arrows represent direct hypotheses, while the dashed arrow represents the moderation effect.

Building on this integrative framework, the next section details the research design, measurement model, and data collection strategy used to empirically test the hypothesized relationships in the Italian context. This methodological transition connects the conceptual logic of AI as an intelligent control with its operationalization through validated behavioral and governance constructs.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This section describes the empirical approach in sufficient detail to ensure replicability and transparency, outlining the research design, measurement strategy, data collection procedures, and analytical steps employed to test the integrated TAM–OIPT framework. The study follows standard guidelines for quantitative research in behavioral and organizational accounting.

This study relies exclusively on primary survey data because the constructs analyzed—perceptions of usefulness, literacy, readiness, substitution, and governance effects—cannot be reliably captured through secondary or archival sources.

The investigation employs a quantitative, cross-sectional, hybrid design that integrates behavioral and organizational perspectives to examine how artificial intelligence (AI) functions as an intelligent control in accounting. The model combines the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)—capturing individual behavioral intention toward AI adoption—with the Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT), which conceptualizes AI as an information-processing and governance mechanism. This integrative approach enables simultaneous assessment of how perceptions such as usefulness, ease of use, literacy, readiness, and social influence translate into governance and risk management outcomes. The design bridges micro-level behavioral determinants and macro-level control implications, reflecting the hybrid nature of AI’s transformation of accounting systems.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

Data were collected from accounting students and professionals located in Northern Italy, representing universities, regional professional accounting orders, and small- to medium-sized enterprises. A structured questionnaire was distributed online via Google Forms during October 2025. Invitations were disseminated through university mailing lists, professional bodies, and partner SMEs using a non-probability convenience sampling approach. Because the survey link was cascaded across institutional contacts and professional networks, the total number of individuals reached could not be reliably tracked; thus, a precise response rate cannot be calculated. This sampling strategy is appropriate for exploratory PLS-SEM applications but limits statistical generalizability, a limitation acknowledged in the Conclusions.

Participation was voluntary, and responses were recorded anonymously. After screening for completeness and consistency, 185 valid questionnaires were retained for analysis. Approximately two-thirds of respondents were accounting or finance students and one-third practitioners, providing both educational and professional perspectives on AI adoption. All respondents confirmed prior exposure to accounting or auditing activities for at least six months. The final sample size satisfies the thresholds for PLS-SEM estimation, exceeding the ten-times rule for the most complex regression path (Hair et al., 2019).

3.3. Sample Size Adequacy and PLS-SEM Justification

Following Hair et al. (2019), the updated interpretation of the ten-times rule is based on the largest number of structural paths directed at any construct, rather than the total number of indicators. In the present model, the construct with the highest number of incoming paths receives seven predictors, implying a minimum recommended sample size of 70 observations. With 185 valid responses, the study exceeds methodological requirements for PLS-SEM estimation and is appropriate for models of moderate complexity.

3.4. Data Analysis Procedure

Although the sample size is adequate for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) estimation, it is not intended to be nationally representative of the entire population of Italian accounting professionals. Respondents were drawn from universities, professional accounting orders, and small- to medium-sized enterprises located in Northern Italy, a context that may differ from other regions in terms of digital infrastructure, institutional support, and educational offerings. In addition, approximately two-thirds of the sample consists of students, while one-third comprises accounting practitioners. This composition is consistent with the exploratory objective of capturing early-stage perceptions of artificial intelligence (AI) adoption among both future and current professionals. However, it implies that external validity to the broader Italian accounting population should be interpreted with caution. Accordingly, the Discussion and Conclusions frame the findings as context-specific, and future research is encouraged to employ larger, stratified samples that allow for systematic comparisons across professional status and organizational environments.

As shown in Table 1, the measurement instrument comprised 31 reflective Likert-type items measured on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree), organized into nine latent constructs adapted from validated prior studies. The full list of constructs, item codes, and representative items is reported in Appendix A, together with contextual vignettes and demographic control variables.

Table 1.

Measurement constructs, item codes, and theoretical sources.

Each construct captures a specific theoretical dimension of the integrated TAM–OIPT framework. Behavioral constructs (PU, PEOU, AL, TR, SI, FC) reflect cognitive and contextual determinants of AI adoption. Perceived substitution benefit (PSB) and intention to use AI (AI_INT) capture substitution perceptions and adoption processes, respectively. Governance and Risk Outcomes (GRO) measure respondents’ perceived effects of AI on governance quality, internal control effectiveness, risk management improvement, and reduced earnings-management risk, rather than objective archival outcomes.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29.0) following standard PLS-SEM procedures (Hair et al., 2019). The analytical process involved: (1) preliminary screening for missing values and outliers, ensuring that all indicators satisfied acceptable distributional properties (|skewness| < 2); (2) computation of descriptive statistics and internal consistency measures; (3) evaluation of the measurement model through indicator loadings, composite reliability (CR > 0.70), and average variance extracted (AVE > 0.50) to establish convergent validity; (4) assessment of discriminant validity using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio; (5) evaluation of the structural model by estimating path coefficients, coefficients of determination (R2), and effect sizes (f2); and (6) non-parametric bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to assess the statistical significance of hypothesized relationships. All reported t-values and p-values are based on two-tailed tests with a significance level of α = 0.05. Mediation effects were examined by testing the indirect effect of perceived substitution benefit (PSB) between AI adoption intention (AI_INT) and governance and risk outcomes (GRO) using bias-corrected bootstrapping.

3.5. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Analysis

As reported in Table 2, mean values across all behavioral constructs exceed 3.5, indicating generally positive perceptions toward AI adoption in accounting. Cronbach’s α coefficients for eight of the nine constructs exceed the conventional threshold of 0.70, confirming satisfactory internal consistency for exploratory research. The relatively high mean scores for perceived usefulness (PU) and technology readiness (TR) suggest that respondents recognize the potential value of AI and perceive themselves as technologically prepared to engage with such tools.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Reliability of Constructs.

The AI literacy (AL) construct exhibits a lower Cronbach’s α (0.44), which can be attributed to the brevity of the three-item scale and the heterogeneous composition of the mixed student–practitioner sample. Importantly, AL’s composite reliability (0.77) and average variance extracted (0.53) meet recommended thresholds, supporting its retention in the model. Nevertheless, results involving AI literacy are interpreted as exploratory and discussed with appropriate caution.

3.6. Assessment of Common Method Bias

Because all constructs were measured using self-reported Likert-type items collected through a single questionnaire, the potential presence of common method bias (CMB) was assessed using both procedural and statistical remedies (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Procedurally, anonymity was ensured, items from different constructs were intermingled, and neutral wording was employed to reduce evaluation apprehension. Statistically, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted by loading all 31 reflective indicators into an unrotated principal components analysis. Multiple factors with eigenvalues greater than one emerged, and the first factor accounted for 26.8% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold commonly associated with substantial CMB.

In addition, full collinearity variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated following Kock (2015). All latent constructs exhibited VIF values below 3.70, with the highest value observed for perceived substitution benefit (PSB). These values fall well below the conservative cutoff of 5.0 recommended for PLS-SEM, indicating that neither multicollinearity nor common method variance is likely to bias the estimated structural relationships. Taken together, these diagnostics suggest that CMB is unlikely to materially affect the results, although it cannot be entirely ruled out and is therefore acknowledged as a limitation.

3.7. Ethical Considerations and Data Availability

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and no personally identifiable information was collected. Respondents were informed that their data would be used exclusively for academic research purposes and that they could withdraw at any time. The study followed institutional ethical guidelines and adhered to principles of responsible research conduct.

The anonymized dataset supporting this study has been deposited in Zenodo under the title “AI as an Intelligent Control: Survey Data from Italy on Accounting Governance and Risk Management” and is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17562178 (accessed on 7 November 2025). These data are provided as Supplementary Materials via an external repository (Zenodo) (Bonelli, 2025). Generative AI tools were not used in the generation, analysis, or interpretation of the data; their use was limited exclusively to language polishing and formatting to improve readability without affecting the substance or results of the research.

4. Results

The following section presents the empirical outcomes derived from the PLS-SEM analysis, translating the theoretical framework and measurement design into quantitative evidence on how AI adoption functions as an intelligent control within the Italian accounting context.

4.1. Overview of Analysis

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied using the 185 valid responses from the Italian survey. The analysis followed a two-stage process: (1) assessment of the measurement model for reliability and validity, and (2) evaluation of the structural model to test the hypotheses derived from the integrated TAM–OIPT framework.

4.2. Measurement-Model Assessment

Following Hair et al. (2019), all standardized loadings exceeded the 0.60 threshold typically considered acceptable in exploratory PLS-SEM applications, confirming that individual items contributed meaningfully to their respective constructs. Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged between 0.73 and 0.89 and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) between 0.52 and 0.67, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency and convergent validity.

Cronbach’s α values reported in Table 3 are consistent with exploratory-level reliability and broadly confirm the earlier descriptive analysis in Table 1. Detailed reliability and validity results for all constructs are summarized in Appendix B.

Table 3.

Reliability and Validity Indicators of Constructs.

Discriminant validity was supported by the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981): each construct’s AVE square root exceeded its correlations with other constructs, and HTMT ratios remained below the conservative 0.85 threshold recommended by Henseler et al. (2015), confirming conceptual distinctiveness among behavioral, substitution, and governance dimensions.

PLS Algorithm Output Summary

The PLS algorithm results confirmed adequate indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity across all constructs. All standardized loadings exceeded the recommended 0.60 threshold, and both Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) met the criteria for internal consistency and convergent validity. The algorithm also produced satisfactory discriminant validity results following the Fornell–Larcker and HTMT criteria. The complete PLS algorithm output, including cross-loadings and diagnostics, is provided in Appendix B.

4.3. Structural Model Results

The structural model exhibited strong explanatory power with R2 = 0.71 for AI Adoption (AI_INT) and R2 = 0.64 for Governance Outcomes (GRO). Bootstrapping (5000 resamples) provided path coefficients and significance levels summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural Model Path Coefficients.

All hypothesized paths except H3c were significant at p < 0.05, confirming that facilitating conditions, AI literacy, technology readiness, and social influence jointly drive AI adoption. Among the behavioral antecedents of AI adoption, AI literacy (β = 0.26) and perceived usefulness (β = 0.21) displayed the largest standardized coefficients, although their magnitudes remain in the moderate range.

4.4. Mediation Effects of Perceived Substitution Benefit

A bias-corrected bootstrapping test confirmed the mediating role of Perceived Substitution Benefit (PSB) between AI Adoption and Governance Outcomes. The indirect effect (β_indirect = 0.41, p < 0.001) was significant, while the direct path (AI_INT → GRO) dropped from β = 0.33 to β = 0.12 (p = 0.09) when PSB was included, indicating full mediation. This supports the proposition that the governance and risk management benefits attributed to AI stem primarily from its perceived capacity to substitute manual procedures effectively.

4.5. Predictive Relevance and Effect Sizes

Cohen’s f2 analysis showed medium effects for PU → AI_INT (0.15) and PSB → GRO (0.26), and small effects for FC → PU (0.07) and AL → PEOU (0.09). Using Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks (0.02 = small, 0.15 = medium, 0.35 = large), these values indicate that PSB → GRO exerts a moderate-to-strong influence on perceived governance outcomes, whereas the behavioral predictors of AI adoption exhibit small to medium effects. Overall, the model exhibits both explanatory and predictive adequacy.

4.6. Interpretation

The empirical evidence demonstrates that Italian accounting students and professionals perceive AI primarily as a governance-enhancing tool rather than merely an automation technology. AI literacy and social influence were critical enablers of adoption, underscoring the importance of collective learning and peer encouragement. Facilitating conditions—training availability and institutional support—reinforced perceived usefulness and ease of use.

The strong mediation of PSB indicates that users translate behavioral intention into governance confidence only when they believe AI can replace rather than augment manual control activities. This substitution logic transforms AI into an “intelligent control,” bridging behavioral adoption with organizational assurance functions. Consistent with this pattern, the structural path from AI adoption to perceived substitution benefit (AI_INT → PSB, β = 0.68) and from PSB to governance and risk outcomes (PSB → GRO, β = 0.61) are markedly stronger than the other coefficients in the model. These paths reinforce the interpretation that perceived substitution benefit is the primary mechanism through which adoption translates into governance-related perceptions.

4.7. Summary of Findings

- Behavioral Drivers: AI literacy, facilitating conditions, perceived usefulness, and social influence all make meaningful, moderate contributions to AI adoption.

- Organizational Impact: Governance and risk management benefits depend on perceived substitution rather than on adoption per se.

- Model Fit: R2 values above 0.60 and satisfactory reliability confirm the robustness of the integrated TAM–OIPT framework in the Italian context.

- Implication: Accounting education and professional training should prioritize AI literacy and substitution-scenario simulation to enhance responsible adoption.

From a robustness standpoint, the analysis should be interpreted in light of the exploratory design and moderate sample size. The mediation test already compares a baseline model with a direct path from AI adoption to governance outcomes with a more complete model including perceived substitution benefit, showing that the substantive pattern of relationships is stable while governance perceptions are largely captured by the substitution mechanism. However, the study is not powered for formal robustness analyses such as multi-group PLS-SEM or measurement invariance testing by role (student versus practitioner), firm size, or digital maturity. These contextual factors are therefore discussed qualitatively in the next section and are explicitly identified as boundary conditions and directions for future research.

5. Discussion and Implications

Building on the empirical results, this section interprets their significance for theory, practice, and policy, introducing the AI-to-Control (A2C) Blueprint to explain how behavioral adoption translates into governance outcomes in accounting. The findings provide empirical confirmation of the integrated TAM–OIPT framework and extend both theories within the context of AI-driven accounting. Within the Technology Acceptance Model, perceived usefulness, AI literacy, and facilitating conditions emerged as dominant antecedents of adoption. This reinforces the behavioral assumption that cognitive beliefs and environmental enablers jointly shape users’ readiness for technological change (Davis, 1989; Bui et al., 2025). However, the present study moves beyond classic acceptance logic by incorporating perceived substitution benefit (PSB) as a bridging construct. The strong mediation effect of PSB indicates that users translate behavioral intention into governance confidence only when they believe that AI can replace, rather than merely augment, manual control activities. From the Organizational Information Processing Theory perspective (Galbraith, 1973), the results suggest that AI adoption enhances organizational information-processing capacity, reducing uncertainty in financial monitoring and risk management. By empirically linking individual behavioral intentions to collective governance outcomes, the study operationalizes OIPT in a novel manner, showing how micro-level adoption decisions aggregate into macro-level control structures. In doing so, the research contributes to the emerging discourse on AI as an intelligent control system (Roos et al., 2025; Odonkor et al., 2024).

Relative to prior TAM-based studies that focus primarily on behavioral intention (e.g., students’ willingness to use AI tools) and to OIPT-inspired work that emphasizes digital transformation and performance outcomes, the present model offers a distinct theoretical contribution. By introducing perceived substitution benefit as a bridge between AI adoption and governance and risk management outcomes, the study shows how individual-level acceptance constructs aggregate into changes in the architecture of internal control. In other words, AI is not only another technology to be accepted, nor merely an additional information system that increases processing capacity; it is theorized as an intelligent control system that reconfigures how governance and assurance functions are performed. This positioning differentiates the TAM–OIPT integration proposed here from earlier frameworks that treat adoption and governance as separate domains.

The positive and significant effects of AI literacy and social influence highlight the social-cognitive dimension of technological transition in accounting. When users possess baseline AI knowledge and receive normative support from peers and institutions, adoption intention strengthens. This resonates with Chen et al. (2022) and Ng et al. (2021), who identified literacy as the linchpin of confidence and self-efficacy in AI contexts. The relatively high coefficients for facilitating conditions confirm that institutional scaffolding—training programs, digital resources, and managerial encouragement—remains essential for sustained adoption. In Italy’s mixed ecosystem of universities and small firms, where technological infrastructure and digital culture vary considerably, these findings stress the need for coordinated capability-building across educational and professional domains. The full mediation of PSB between AI adoption and governance outcomes reveals that perceived substitution is not a peripheral perception but a structural mechanism connecting behavioral acceptance with organizational assurance. Users attribute governance improvements—such as error detection and fraud reduction—to AI only when they believe it replaces traditional controls effectively. This aligns with Lehner et al. (2022) and Noordin et al. (2022), who describe AI as a hybrid governance agent capable of combining analytical precision with continuous monitoring.

Synthesizing these insights, the study proposes the AI-to-Control (A2C) Blueprint, a conceptual pathway describing how behavioral, technological, and governance dimensions converge:

- Awareness Phase (Literacy and Readiness): Building cognitive and infrastructural readiness through education and organizational support.

- Adoption Phase (Behavioral Intention): Fostering ease of use, perceived usefulness, and peer endorsement to trigger utilization.

- Substitution Phase (Intelligent Replacement): Achieving confidence that AI can autonomously execute and verify accounting procedures.

- Control Phase (Governance Integration): Translating substitution into enhanced internal control, transparency, and risk mitigation.

The A2C Blueprint extends prior models of digital transformation (Abu Afifa et al., 2024) by treating AI not as a technological endpoint but as a governance infrastructure that closes the loop between decision automation and ethical oversight.

For educators, the evidence underscores the necessity of embedding AI literacy and ethics modules into accounting curricula. Universities in Italy and elsewhere should integrate simulation-based learning where students interact with AI audit and analytics platforms to observe substitution effects in real time. For practitioners, the results highlight the importance of institutional support and cross-functional collaboration. Accountants, auditors, and IT professionals must jointly design workflows where AI complements human judgment while maintaining accountability lines. Training should emphasize explainability and data-governance compliance to prevent algorithmic opacity (Pierotti et al., 2024). The organizational environment also conditions how AI functions as an intelligent control. The sampling frame focuses on universities, professional orders, and small- to medium-sized enterprises in Northern Italy, where resource constraints and heterogeneous legacy systems may limit the speed at which advanced AI can be embedded into existing ERP and accounting infrastructures. In organizations with more developed digital architectures, AI tools can be integrated more tightly into transaction processing and monitoring, making substitution effects and governance improvements more salient. By contrast, in settings with fragmented or manual systems, AI may initially be used in a more peripheral, advisory manner. These contextual differences reinforce the need to treat firm size, digital maturity, and existing technology as boundary conditions for the A2C Blueprint and as candidates for explicit control or moderator variables in future multi-group or multi-level analyses. For regulators and professional bodies, the perceived link between AI substitution and governance quality suggests that AI tools can strengthen compliance monitoring if accompanied by transparent audit trails and ethical frameworks. Policymakers should consider updating standards to address algorithmic decision-making in assurance processes.

The Italian evidence reveals a hybrid professional landscape anchored in strong governance traditions yet increasingly open to technological modernization. The combination of high usefulness perception and moderate literacy signals an evolving readiness stage. The study thus positions Italy as a transitional laboratory where educational innovation can accelerate the shift from manual to intelligent accounting. Regional professional orders, particularly in the North, could pioneer AI certification programs linking academic training with applied governance analytics.

While the behavioral drivers identified here echo those found in Vietnam (Bui et al., 2025) and the Nordic region (Lehner et al., 2022), the Italian case emphasizes governance and ethics more strongly. This cultural framing supports the notion that AI adoption patterns are path-dependent: in institutional environments valuing accountability and prudence, AI is adopted not for speed but for control reliability. Cross-country replication could validate this institutional conditioning and enrich international accounting-technology theory.

In summary, the study demonstrates that AI’s transformative power in accounting lies not in automation per se but in its capacity to become an intelligent control—a socio-technical mechanism that blends behavioral acceptance with governance assurance. By empirically validating the mediating role of substitution benefit and proposing the A2C Blueprint, the research reframes AI adoption as a systemic reconfiguration of control architecture rather than a linear process of technology diffusion.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how artificial intelligence (AI) functions as an intelligent control in accounting, capable of substituting traditional manual processes while enhancing governance, transparency, and risk management. The findings indicate that governance improvements emerge not from AI adoption alone, but from users’ confidence in AI’s ability to substitute manual control activities reliably. By integrating the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Organizational Information Processing Theory (OIPT), the research developed and empirically validated a behavioral–organizational framework using data from 185 accounting students and professionals in Northern Italy. The analysis confirmed that AI adoption is driven not only by perceived usefulness and ease of use, but also by literacy, readiness, and social context. Importantly, the results show that AI’s perceived substitution capacity mediates the translation of adoption intention into governance outcomes, reframing digital transformation as a reconfiguration of control mechanisms rather than a mere technological upgrade.

The results indicate that AI literacy, facilitating conditions, perceived usefulness, and social influence are the key behavioral drivers of AI adoption, each exerting a moderate effect size rather than a dominant influence. Respondents with greater competence and institutional support show higher adoption intention, while technology readiness has a smaller effect, emphasizing the importance of awareness and training during early diffusion stages. The mediation analysis confirmed that perceived substitution benefit fully mediates the link between adoption and governance outcomes—users perceive improvements in control and fraud detection only when AI is viewed as a substitute for manual oversight. The strong association between PSB and governance outcomes supports the conceptualization of AI as an intelligent control mechanism that reduces manipulation risk and enhances internal control effectiveness, aligning with Zhang et al. (2023) and Noordin et al. (2022).

Theoretically, the study enriches TAM by introducing perceived substitution benefit as a key mediator connecting behavioral intention to organizational outcomes, and it extends OIPT by empirically demonstrating how AI enhances information-processing capacity and governance reliability. From a policy perspective, the findings highlight the need for transparent, ethical AI integration. Regulators and professional bodies in Italy should establish standards ensuring algorithmic auditability, fairness, and explainability. Embedding AI ethics in assurance frameworks would reinforce institutional trust while safeguarding accountability in digitalized financial systems.

Educational and managerial implications are equally significant. AI literacy should become a core competence in accounting curricula, supported by interdisciplinary modules on data governance and ethics. Organizations should invest in training and mentoring programs that build user confidence and align AI applications with internal audit goals, ensuring that substitution enhances rather than replaces professional judgment.

While the study provides good evidence, several limitations offer opportunities for further inquiry. First, because the sample includes both students and practitioners, perceptual differences across subgroups may exist. This hybrid composition, however, is appropriate for exploratory research and aligns with prior accounting-technology studies that examine early-stage AI adoption across heterogeneous respondent groups. Second, the cross-sectional design captures perceptions at a single point in time; longitudinal or multi-country investigations could trace how attitudes, substitution beliefs, and governance expectations evolve as AI tools mature. Third, although common method bias diagnostics—Harman’s single-factor test and full collinearity VIFs—indicated no substantial threat, the reliance on a single self-report instrument remains a methodological constraint. Future studies could incorporate multi-source data or marker-variable techniques to further mitigate this risk. A related measurement limitation is that GRO is operationalized as a perceptual construct rather than through objective governance indicators such as fraud detection outcomes, audit error rates, or anomaly identification accuracy. As a result, the study reflects how respondents perceive AI’s governance role, and future research should triangulate these perceptions with hard performance metrics. A further measurement limitation concerns the relatively low internal consistency of the AI literacy scale. Although the construct exhibits satisfactory CR and AVE, future research should refine and extend the AL item set to capture literacy more reliably across different respondent groups. Fourth, the model was estimated on the pooled sample, and the study was not powered for formal robustness analyses such as multi-group PLS-SEM or measurement invariance testing by role (student versus practitioner), firm size, or digital maturity. Larger stratified samples would allow tests of measurement invariance and comparisons of structural relations across organizational contexts. Fifth, future work should integrate objective governance indicators—such as fraud detection efficiency, audit error rates, or anomaly identification accuracy—to complement perceptual measures and strengthen causal inference. Future research could also formalize these ethical dimensions into an algorithmic governance construct—capturing fairness, explainability, and auditability—that may mediate or moderate the relationship between perceived substitution benefit and governance outcomes.

Finally, applying and validating the AI-to-Control (A2C) Blueprint in real corporate environments would provide deeper insights into how individual readiness and substitution beliefs translate into structural governance transformation in practice.

Overall, this research demonstrates that the shift from manual to intelligent accounting is both institutional and behavioral. AI becomes an intelligent control when users perceive it as a trustworthy substitute for traditional governance systems, reshaping the architecture of accountability. By validating the mediating role of substitution benefit, the study offers theoretical clarity and practical guidance: education builds readiness, substitution builds trust, and trust builds governance. As AI continues to transform the accounting profession, its true promise will depend not on algorithms alone, but on the human capacity to integrate them responsibly within ethical systems of control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17562178 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study involved only anonymous survey responses and did not require ethical approval under institutional guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at “AI as an Intelligent Control: Survey Data from Italy on Accounting Governance and Risk Management” under the DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17562178.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank his former student, Giacomo Pagliaro, for providing valuable assistance in conducting the survey. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025) for language polishing and formatting. The author has reviewed and edited all outputs and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| A2C | AI-to-Control Blueprint |

| AL | AI Literacy |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| FC | Facilitating Conditions |

| GRO | Governance and Risk Outcomes |

| OIPT | Organizational Information Processing Theory |

| PEOU | Perceived Ease of Use |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| PSB | Perceived Substitution Benefit |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness |

| SI | Social Influence |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| TR | Technology Readiness |

Appendix A. Survey Instrument (English Version)

This appendix presents the English version of the survey instrument used in the study and outlines the construct structure, scale format, and coding scheme.

Appendix A.1. Purpose and Administration

The structured questionnaire was designed to measure the perceived substitution of traditional accounting practices by artificial intelligence (AI) and its implications for governance and risk management.

Data were collected via Google Forms between 15 October and 5 November 2025, from accounting students and professionals in Northern Italy. All responses were anonymous and used solely for academic purposes.

Appendix A.2. Scale and Response Format

Participants rated their agreement on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree). Each construct was operationalized using multiple reflective indicators adapted from validated prior studies.

Appendix A.3. Construct Blocks and Sample Items

| Construct | Code Range | Example Item |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | PU1–PU4 | Using AI improves detection of accrual irregularities compared to traditional methods. |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | PEOU1–PEOU4 | AI tools for accounting would be easy to learn and operate. |

| AI Literacy (AL) | AL1–AL3 | I understand the main capabilities and limitations of AI in accounting. |

| Technology Readiness (TR) | TR1–TR3 | My university/organization provides adequate digital tools for analytics. |

| Social Influence (SI) | SI1–SI3 | People important to me think I should use AI in accounting tasks. |

| Facilitating Conditions (FC) | FC1–FC3 | I can obtain training or support to use AI in accounting. |

| Perceived Substitution Benefit (PSB) | PSB1–PSB4 | AI can replace manual checks while improving error detection. |

| Intention to Use AI (AI_INT) | AI_INT1–AI_INT3 | I intend to use AI-based tools for accounting within the next 3 months. |

| Governance and Risk Outcomes (GRO) | GRO1–GRO4 | AI reduces opportunities for earnings management and strengthens internal control effectiveness. |

Appendix A.4. Contextual Scenarios (Vignettes)

Two short decision vignettes were used to enhance realism and situational judgment.

- Abnormal accruals: An AI system flags specific customer segments as risky; respondents rated perceived changes in detection accuracy and decision time.

- Narrative analysis (MD&A): An AI algorithm highlights optimistic disclosure language; respondents rated confidence in the assessment and expected reduction in false negatives.

Appendix A.5. Control and Demographic Items

Additional variables collected included: prior AI use (yes/no; task type), weekly hours using Excel/ERP, attention-check items, and respondent characteristics (role—student/professional, years of accounting study/work, gender, institution, and region).

Appendix A.6. Construct Coding Summary

Construct blocks and item codes are provided in Appendix A, with the full list of reflective items for PU, PEOU, AL, TR, SI, FC, PSB, AI_INT, and GRO, alongside the vignette prompts and demographic controls.

| Code Group | Number of Items |

| PU | 4 |

| PEOU | 4 |

| AL | 3 |

| TR | 3 |

| SI | 3 |

| FC | 3 |

| PSB | 4 |

| AI_INT | 3 |

| GRO | 4 |

| Total | 31 core items + 2 vignettes (6 questions) |

Appendix B. Reliability and Validity Summary

Table A1.

Construct reliability and convergent validity results.

Table A1.

Construct reliability and convergent validity results.

| Construct | Items | Cronbach’s α | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 4 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.58 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | 4 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.55 |

| AI Literacy (AL) | 3 | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.53 |

| Technology Readiness (TR) | 3 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.59 |

| Social Influence (SI) | 3 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.66 |

| Facilitating Conditions (FC) | 3 | 0.73 | 0.87 | 0.69 |

| Perceived Substitution Benefit (PSB) | 4 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| Intention to Use AI (AI_INT) | 3 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.65 |

| Governance and Risk Outcomes (GRO) | 4 | 0.78 | 0.88 | 0.64 |

Note: For eight constructs, Cronbach’s α exceeded the conventional 0.70 threshold, and all constructs, including AI literacy (AL), demonstrated Composite Reliability (CR) greater than 0.70 and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) above 0.50, consistent with Hair et al. (2019). The lower α value for the three-item AI literacy scale (0.44) reflects the brevity of the scale and the heterogeneous composition of the sample. Accordingly, AL is retained for analysis, but its effects are interpreted as exploratory and discussed with appropriate caution.

References

- Abu Afifa, M. M., Nguyen, T. H., Le, M. T. T., Nguyen, L., & Tran, T. T. H. (2024). Accounting going digital: A Vietnamese experimental study on artificial intelligence in accounting. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 55(1), 1031–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. (2019). Scenario-based approach to re-imagining higher education for the future of work. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 10(1), 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mashalah, H., Hassini, E., Gunasekaran, A., & Bhatt, D. (2022). The impact of digital transformation on supply chains. Transportation Research Part E, 165, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almufadda, G., & Almezeini, N. A. (2022). Artificial intelligence applications in the auditing profession: A literature review. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting, 19(2), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J. E., Ward, H., & Yoon, J. (2021). UTAUT as a model for understanding intention to adopt artificial intelligence and related technologies among librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(6), 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A., Mani, V., Kamble, S. S., Khan, S. A. R., & Verma, S. (2024). AI-driven innovation for supply chain resilience and performance. Annals of Operations Research, 333(1), 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, M. I. (2025). AI as an intelligent control: Survey data from Italy on accounting governance and risk management [Data set]. Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H. Q., Phan, Q. T. B., & Nguyen, H. T. (2025). AI adoption: A new perspective from accounting students in Vietnam. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 32(1), 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, A., Li, Y., Wang, M., Shi, J., & Jin, Y. (2020). Team knowledge exchange and transformational leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Rana, N. P., Khorana, S., Mikalef, P., & Sharma, A. (2023). Assessing organizational users’ intentions and behavior to AI-integrated CRM systems: A meta-UTAUT approach. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(4), 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Y., Su, Y. S., Ku, Y. Y., Lai, C. F., & Hsiao, K. L. (2022). Exploring the factors of students’ intention to participate in AI software development. Library Hi Tech, 42(2), 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y., Chai, C. S., Lin, P. Y., Jong, M. S. Y., Guo, Y., & Qin, J. (2020). Promoting readiness for the AI age. Sustainability, 12(16), 6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerji, H., & Salimi, A. (2021). Mediating effect of use perceptions on technology readiness and AI adoption in accounting. Accounting Education, 30(2), 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Childe, S. J., Bryde, D. J., Giannakis, M., Foropon, C., Roubaud, D., & Hazen, B. T. (2020). Big data analytics and AI pathways to operational performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 226, 107599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M., & Hammoud, J. (2023). Unveiling the influence of AI and machine learning on financial markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(10), 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, J. R. (1973). Designing complex organizations. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K., Kannan, D., Jørgensen, T. B., & Nielsen, T. S. (2022). Supply chain 4.0 performance measurement. Transportation Research Part E, 164, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S. C., Cheung, W. M. Y., & Zhang, G. (2021). Evaluating an AI literacy course. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureljusic, M., & Karger, E. (2023). Forecasting in financial accounting with AI: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 25(1), 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O. M., Ittonen, K., Silvola, H., Ström, E., & Wührleitner, A. (2022). AI-based decision-making in accounting and auditing: Ethical challenges. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 35(9), 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner-Hanetseder, S., Lehner, O. M., Eisl, C., & Forstenlechner, C. (2021). A profession in transition: AI-based accounting. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 22(3), 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. H., Yu, C. C., Shih, P. K., & Wu, L. Y. (2021). STEM-based AI learning for non-engineering undergraduates. Educational Technology & Society, 24(3), 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordin, N. A., Hussainey, K., & Hayek, A. F. (2022). The use of artificial intelligence and audit quality: Evidence from external auditors. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(8), 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odonkor, B., Kaggwa, S., Uwaoma, P. U., Hassan, A. O., & Farayola, O. A. (2024). The impact of AI on accounting practices: A review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 21(1), 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Ahmad, S. F., Ahmad, A. Y. B., Al Shaikh, M. S., Daoud, M. K., & Alhamdi, F. M. H. (2023). Riding the waves of artificial intelligence in advancing accounting. Sustainability, 15(19), 14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, M., Monreale, A., & Santis, F. (2024). Artificial intelligence in accounting and auditing. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, D., Schlegel, D., & Kraus, P. (2025). Adopting artificial intelligence in accounting: Prerequisites and applications. Journal of Electronic Business & Digital Economics, 4(2), 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, B. (2024). Artificial intelligence ethics in accounting. Journal of Accounting, Ethics & Public Policy, 25(1), 67–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Sharma, M., & Dhir, S. (2021). Modeling the effects of digital transformation in manufacturing. Technology in Society, 67, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudaryanto, M. R., Hendrawan, M. A., & Andrian, T. (2023). The effect of technology readiness, digital competence, perceived usefulness, and ease of use on accounting students artificial intelligence technology adoption. E3S Web of Conferences, 388, 04055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Zhu, W., Dai, J., Wu, Y., & Chen, X. (2023). Ethical impact of AI in managerial accounting. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 49, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.