Abstract

The rapid rise in cryptocurrency presents both opportunities and challenges for retail investors due to its volatility and technological complexity. Research on investment decisions has primarily focused on behavioural finance, often overlooking how learning and literacy shape investor actions. This study addresses this gap by examining how herding behaviour, financial literacy, and digital literacy impact cryptocurrency investment decisions. Grounded in Social Learning Theory and supported by UTAUT to operationalise digital literacy, this study examines how herding behaviour, financial literacy, and digital literacy shape cryptocurrency investment decisions. We analyse survey data from 138 Indonesian retail investors through PLS-SEM. Key findings show that financial literacy (β = 0.443, t = 5.041) and digital literacy (β = 0.495, t = 4.246) are primary determinants of investment decisions, while herding behaviour (β = 0.016, t = 0.628) does not directly influence them but does so indirectly by enhancing investor literacy. This demonstrates that social observation and learning can convert herd-driven impulses into rational choices when mediated by literacy. By extending Social Learning Theory into digital investment contexts, this study provides insights for investors and policymakers seeking to enhance financial and digital literacy.

1. Introduction

Technological advances have led to the emergence of cryptocurrencies, which use cryptography to facilitate peer-to-peer transactions without intermediaries (Gupta & Shrivastava, 2022). Since the introduction of Bitcoin in 2008, cryptocurrency adoption has expanded rapidly, especially among Millennial and Gen Z retail investors (Rubasinghe, 2017). Notably, users increased from 5 million in 2016 to 575 million by November 2023 (de Best, 2023), with Millennials and Gen Z representing 48% each, while Generation X accounts for less than 5% and Baby Boomers under 1% (Lim, 2023).

The advancement of digital technology also contributes to the significant use of social media for obtaining information about cryptocurrency investment (Rodpangtiam et al., 2024). Currently, many influencers utilise social media platforms to post marketing content that indirectly encourages herd behaviour among investors, particularly in the cryptocurrency market. Herding is driven by educational content discussing cryptocurrency price prediction based on the influence of economic uncertainty (Bouri et al., 2019), the geopolitical situation in Ukraine-Russia and the Middle East, and trading volume (Mnif et al., 2023). Gurdgiev and O’Loughlin (2020) examined American herding behaviour, focusing on investors’ reactions to fear and uncertainty, and offered insights into the psychological aspects of cryptocurrency investment behaviour. Therefore, herding behaviour may affect financial literacy when individuals use observations of group behaviour to learn about the market, particularly when the herding stems from investment content that provides educational information (Trisno & Vidayana, 2023).

Particularly in volatile markets like cryptocurrency, investors often follow others’ actions due to psychological factors, such as FoMO (fear of missing out) (Kaur et al., 2023), which may lead to impulsive decisions and potential risks, such as overvalued assets or losses during market downturns (Boubaker et al., 2024). Suppose this herding behaviour is driven by competent influencers, investors, or communities. In that case, it may enhance investors’ understanding of cryptocurrency investments, particularly among novice investors, and ultimately help them make informed investment decisions. Financial literacy enables investors to critically evaluate trends, assess risks, and make informed choices based on moral principles rather than peer pressure (Alomari & Abdullah, 2023). Similarly, Digital literacy is essential in the cryptocurrency market, enabling investors to navigate platforms, utilise analysis tools, and identify reliable information (Hartono & Oktavia, 2022). Together, these literacies mediate herding behaviour and support better decision-making. Based on a synthesis of previous studies, the research gap is that few studies have simultaneously examined both financial and digital literacy as mediating variables linking herding behaviour to investment decisions. In this regard, digital literacy complements financial literacy by enabling investors to operate cryptocurrency platforms more effectively and transform socially driven impulses into rational investment decisions.

By 2024, the country recorded 22.9 million registered cryptocurrency users, a figure larger than the population of some nations, making Indonesia one of the world’s most dynamic crypto markets (Liman, 2025). As a collectivist country, Indonesians are prone to herd behaviour, including in investment decisions (Munkh-Ulzii et al., 2018). At the same time, it represents a crucial testing ground for the role of literacy in shaping rational investment behaviour. Although grounded in the Indonesian context, the insights are generalizable to other emerging markets with fast-growing crypto adoption, where rapid diffusion of digital finance meets varying levels of literacy and strong social influence. Several researchers have examined cryptocurrency investment in Indonesia from different perspectives. Paretta et al. (2024) explored how risk and return affect Generation Z’s investment decisions, suggesting that optimal investment outcomes require sound financial behaviour by balancing behavioural bias and financial literacy. Amsyar et al. (2020) Discussed financial risks and blockchain security, emphasising that cryptocurrency investors must remain aware of these technological vulnerabilities. Although the study did not explicitly address literacy, it implicitly highlights the importance of both financial and digital literacy in navigating crypto investments. Dasman (2021) Analysed cryptocurrency as an investment instrument and found that investors need to understand its characteristics in terms of return potential and associated risks, reinforcing the role of financial literacy in guiding rational decisions. Meanwhile, Khuzaini et al. (2024) Examined strategies used by investors to generate profits from cryptocurrency trading, showing that success in this area depends on financial literacy, such as diversification, risk mitigation, and digital literacy related to the use of exchange platforms and crypto wallets. Overall, while these previous studies provide valuable descriptive insights, they lack critical integration and fail to evaluate how behavioural biases, financial literacy, and digital literacy jointly influence investment decisions, leaving a conceptual and empirical gap that this study seeks to address.

Together, these studies underscore the growing relevance of literacy and behavioural understanding in the Indonesian crypto market. Most prior studies on cryptocurrency investment have examined behavioural biases and literacy-related factors separately, without integrating them into a unified explanatory model. No existing study has empirically investigated financial literacy and digital literacy as simultaneous mediators in the relationship between herding behaviour and investment decisions, leaving this mechanism theoretically proposed but empirically untested. Methodologically, earlier research has also not modelled digital literacy as a higher-order construct within a reflective–formative PLS-SEM framework, creating a methodological gap that this study addresses.

To analyse the variables influencing cryptocurrency investment decisions, this study focuses on the roles of herding behaviour, digital literacy, and financial literacy within the framework of Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977). From an academic perspective, it extends the application of Bandura’s theory by illustrating how social observation, imitation, and cognitive learning affect investor behaviour in digital financial environments. Financial and digital literacy serve as cognitive mechanisms through which individuals internalise information and transform socially observed, herd-driven actions into informed, rational investment decisions (Thi Chinh et al., 2024). From a policy perspective, the study provides regulators with insights for designing educational initiatives that enhance investors’ learning processes and literacy, thereby reducing susceptibility to social bias and irrational behaviour (Coşkun et al., 2016). From a practical standpoint, the research emphasises the importance of continuous learning and literacy development among retail investors to strengthen their capacity for responsible, well-informed participation in cryptocurrency markets.

Based on the background of the problem, the research questions that will be answered through statistical hypothesis testing in this study are as follows:

- Does herding behaviour positively affect cryptocurrency investment decisions?

- Does herding behaviour positively affect financial literacy?

- Does financial literacy mediate the effect of herding behaviour on cryptocurrency investment decisions?

- Does herding behaviour positively affect digital literacy?

- Does digital literacy mediate the effect of herding behaviour on cryptocurrency investment decisions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Undepinning Theory

2.1.1. Theoretical Review

This study adopts Social Learning Theory, initially proposed by Bandura (1977, 1986), as the theoretical foundation for explaining cryptocurrency investment behaviour. The theory posits that individuals acquire new knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours through observing others in their social environment. Learning occurs when individuals observe others’ actions and their consequences, then cognitively process and store that information in memory. These observations form the basis for later behavioural expressions, meaning that behaviour is not only shaped by direct experience but also by vicarious experiences gained through social interaction and observation.

In financial and technological contexts, such as cryptocurrency investment, Social Learning Theory is particularly relevant because investors often rely on observing peers, online communities, or influencers before making decisions. Through continuous exposure to social and digital environments, investors learn which strategies appear successful, what risks are involved, and how others react to market fluctuations. These social cues are then internalised and used as reference points in forming investment intentions and behaviours.

Within this framework, herding behaviour is the observable manifestation of social influence, in which investors mimic others’ actions based on perceived expertise or credibility. Financial literacy and digital literacy are cognitive dimensions of learning that help individuals interpret financial data, assess risks, and operate digital investment platforms effectively. These literacies transform imitative behaviour into informed, reasoned, and responsible decision-making processes. As a result, investment decisions emerge as behavioural outcomes of both social observation and cognitive processing. Overall, Social Learning Theory provides an integrative foundation that connects social influence, cognition, and behaviour, offering a comprehensive explanation of how individuals learn and act within digital financial ecosystems.

2.1.2. Conceptual Framework

Grounded in Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), financial literacy and digital literacy are conceptualised as mediating factors that enable individuals to transform socially observed behaviours into informed cryptocurrency investment decisions. Financial literacy reflects the cognitive learning process that enables investors to evaluate risks and returns. In contrast, digital literacy represents the technological competence gained through observation and practice in digital environments (Alomari & Abdullah, 2023). Digital literacy enhances the perceived ease and accessibility of technology-driven investments (Jariyapan et al., 2022). Regarding cryptocurrency investments, this expansion offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between psychological, technological, and educational factors (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Furthermore, digital literacy can be elaborated using the framework of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2012). UTAUT’s constructs, such as facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, and effort expectancy, offer a structured approach to understanding how individuals acquire and apply digital skills in technology-based environments (Mohammadyari & Singh, 2015). Although Social Learning Theory explains the learning process through observation and cognition, UTAUT complements it by clarifying the specific technological factors that determine how learned behaviours translate into the effective use of digital platforms. In the context of cryptocurrency, this framework helps explain how investors’ digital literacy developed through social exposure and experience enhances their ability to navigate exchanges, interpret information, and conduct transactions efficiently. Thus, integrating UTAUT into Social Learning Theory provides a more comprehensive understanding of how digital competence supports rational, informed investment decisions. Building on Khechine et al. (2020), the synthesis of Social Learning Theory with the UTAUT framework indicates that individuals’ adoption choices are shaped not only by their perceptions of usefulness and ease of use, but also by the extent to which they observe and emulate influential actors within their digital surroundings. UTAUT provides a valuable tool that enables decision makers to understand the factors driving e-learning system acceptance (Abbad, 2021).

Herding explains the tendency for individuals to imitate others’ actions in uncertain environments (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2001). In this study, herding behaviour is assumed to enhance investors’ learning and perception processes. Specifically, herd-driven influences can encourage individuals to acquire or strengthen their financial and digital literacy as they attempt to rationalise or validate the collective behaviour they observe. Thus, proposed paths from herding behaviour to financial literacy and digital literacy.

Individuals, according to Social Learning Theory, acquire knowledge and behaviours by observing others, interpreting the information mentally, and eventually reproducing these behaviours when similar situations arise. In this context, herding behaviour reflects a form of social learning, whereby investors mimic the actions of others in times of uncertainty, creating the basis upon which financial and digital competencies can develop (Fatima et al., 2024).

Financial literacy and digital literacy act as the cognitive outcomes of this learning process. Through exposure to others’ investment experiences and interactions within online communities, investors enhance their understanding of financial risks, returns, and regulatory aspects, as well as their ability to operate digital platforms effectively (Khan, 2025). These literacies enable investors to move from imitation to informed judgement, transforming observed behaviours into more rational investment decisions.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Relationship Between Herding Behaviour and Cryptocurrency Investment Decision

The term herding behaviour describes people’s propensity to mimic the behaviour of a larger group, frequently without doing their own research or analysis. This phenomenon occurs when people rely on social cues and group dynamics to guide their decisions, particularly in uncertain or complex environments (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2001). In financial markets, herding behaviour is common as investors react to others’ actions, believing that group decisions are more informed or rational (Munkh-Ulzii et al., 2018). While herding can create a sense of security through conformity, it also leads to irrational market trends, such as bubbles or crashes, driven by collective sentiment rather than intrinsic asset values (Setiyono et al., 2013).

Cryptocurrency investment decisions involve allocating financial resources into digital assets, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, often driven by high-risk, high-reward expectations (Kyriazis, 2020). Market volatility is one of the many elements that affect these decisions, along with regulatory uncertainty and investor psychology (Hall & Jasiak, 2024). Unlike traditional investments, cryptocurrency trading operates in a decentralised, highly speculative environment, which heightens the influence of extraneous factors such as social influence and emotional responses (Islam et al., 2024). Consequently, decision-making in cryptocurrency investment often extends beyond rational analysis, driven by the fear of missing out, incorporating elements of behavioural finance and psychological biases (Gupta & Shrivastava, 2022).

Herding behaviour significantly influences cryptocurrency investment decisions, as investors often rely on the actions and sentiments of others to navigate the volatile, unpredictable market (Samal & Dasmohapatra, 2020). According to the herding theory, individuals are more likely to follow group trends when faced with uncertainty, if collective actions reflect superior information or strategies (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2001). In the context of cryptocurrency, herding often manifests through price surges driven by social media trends, peer recommendations, or the actions of influential market participants (He & Hamori, 2024). Due to this behavioural bias, investors may make suboptimal choices, such as buying assets at price peaks or selling during sudden declines, thereby amplifying market volatility. Understanding the role of herding in cryptocurrency investment decisions is essential to developing strategies that mitigate its adverse effects and promote more informed, rational investment behaviour.

H1.

Herding behaviour positively affects cryptocurrency investment decisions.

2.2.2. Relationship Among Herding Behaviour, Financial Literacy, and Cryptocurrency Investment Decision

Financial literacy is the ability to understand and utilise financial information for risk assessment, resource management, and informed investment decisions. It is essential to navigate the complex cryptocurrency market, enabling investors to understand market trends better and make sound investment choices (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). In cryptocurrency investing, higher financial literacy enables individuals to assess opportunities and risks effectively, fostering confidence in decision-making and improving investment outcomes (Amsyar et al., 2020).

Herding behaviour, the tendency to follow others’ decisions in uncertain situations, can positively influence financial literacy by providing opportunities for collective learning and understanding (Bikhchandani & Sharma, 2001). When investors observe actions from others in the market, they may be inspired to improve their financial knowledge to align with or critically evaluate group trends (Talwar et al., 2021). Herding can serve as a reference point, encouraging individuals to seek a deeper understanding of financial concepts and market dynamics, ultimately enhancing their financial literacy (Angela-Maria et al., 2015). In the context of digital assets, herding is further amplified by social media, online communities, and influencers, which accelerate information diffusion and reinforce collective sentiment (Briola et al., 2023). However, existing findings remain fragmented, while some studies highlight herding as a dominant behavioural bias driving crypto investment (Al-Mansour, 2020). Other research reports its effects as situational or mediated by investor knowledge (Hidayat & Moin, 2023). These inconsistencies suggest the need for a more integrated framework that incorporates cognitive factors, such as literacy levels, to better understand how herding shapes investment decisions.

H2.

Herding behaviour positively affects financial literacy.

Financial literacy can act as a mediator in a favourable association between herding behaviour, crypto investment decisions, and financial literacy. Individuals’ expectations of success drive their behaviours, and in this context (Mu’izzuddin et al., 2017). Herding behaviour may motivate investors to enhance their financial literacy to better participate in group-driven market trends (Lakonishok et al., 1992). Enhanced financial literacy, in turn, enables investors to critically evaluate herd behaviour and leverage it to make informed cryptocurrency investment decisions (Merli & Roger, 2014). This study suggests that herding behaviour, when combined with efforts to improve financial literacy, can lead to more informed and calculated investment decisions in the cryptocurrency market (Setiyono et al., 2013). Empirical studies show that higher financial literacy is associated with more cautious, risk-aware, and goal-oriented crypto investment patterns (Savithri & Rajakumari, 2025). The literature also notes gaps: many studies emphasise its direct influence but rarely examine financial literacy as a mediating mechanism that shapes how behavioural biases are translated into actual investment decisions. This gap creates an opportunity to explore financial literacy not only as a predictor of decision quality but also as a buffer against irrational tendencies such as herding.

H3.

Financial literacy can mediate the effect of herding behaviour on cryptocurrency investment decisions.

2.2.3. Relationship Among Herding Behaviour, Digital Literacy, and Cryptocurrency Investment Decision

Digital literacy refers to the ability to utilise digital technology effectively, encompassing the understanding, evaluation, and engagement with digital tools and platforms (Hartono & Oktavia, 2022). In the context of cryptocurrency investment, digital literacy enables individuals to navigate complex platforms, analyse digital market trends, and access reliable information to support decision-making (El Hajj & Farran, 2024). Investors with more proficient digital literacy are better equipped to utilise advanced tools, such as blockchain explorers or cryptocurrency analytics platforms, thereby enhancing their confidence and accuracy in making investment decisions (Amsyar et al., 2020).

Herding behaviour, characterised by the tendency to follow others’ investment actions, often drives investors to participate in cryptocurrency trading (Bouri et al., 2019). This phenomenon can lead to increased digital literacy, as investors strive to understand and effectively utilise cryptocurrency trading platforms to align their actions with the perceived collective wisdom (Jariyapan et al., 2022). Investors are influenced by herding, anticipating positive outcomes by improving their literacy of digital platforms to make well-informed investment decisions. Consequently, the interaction between herding behaviour and digital literacy reflects a process in which social influence motivates individuals to enhance their technological competencies in order to align with prevailing market trends (El Hajj & Farran, 2024). Recent research suggests that inadequate digital literacy increases exposure to misinformation, scams, and an overreliance on social factors, which may heighten susceptibility to herd-driven decisions (Zheng et al., 2024).

H4.

Herding behaviour positively affects digital literacy.

Herding behaviour encourages individuals to enhance their digital literacy, as they perceive it as a necessary skill for participating effectively in collective trends and achieving better outcomes (Lakonishok et al., 1992). Enhanced digital literacy enables investors to analyses herding behaviour critically, assess the validity of group actions, and make informed cryptocurrency investment decisions (Hartono & Oktavia, 2022). This mediation highlights that herding behaviour, when combined with efforts to improve digital literacy, can lead to more informed and successful crypto-market investment decisions. Although the importance of digital literacy is widely acknowledged, empirical studies remain limited, and few have modelled it jointly with behavioural biases and financial competencies. This lack of integration underscores the need to examine how digital literacy interacts with herding tendencies and financial literacy to shape investment outcomes.

H5.

Digital literacy can mediate the effect of herding behaviour on cryptocurrency investment decisions.

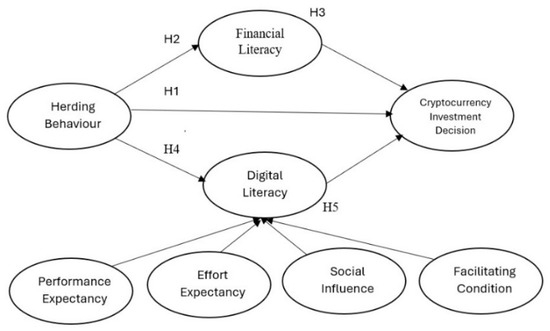

In Figure 1, we present the conceptual model of our research.

Figure 1.

The Conceptual Model.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

This study tested the suggested hypothesis using a cross-sectional quantitative technique. The SurveyMonkey platform was used to target retail investors in cryptocurrency investment instruments, using a convenience sample. The online questionnaire was distributed to cryptocurrency retail investors, members of the Indonesian Crypto Asset Traders Association (ASPAKRINDO), and university students who have already invested in cryptocurrency through the online crypto trading platform. The questionnaire is available in the Appendix A. An intercept survey was also conducted at the government event for Crypto Literacy Month, held in May 2024. The exact number and distribution of active cryptocurrency investors are unknown, so this study’s population is considered unknown. For this unknown population, the minimum required sample size was determined using G*Power version 3.1. We used G*Power with α = 0.05, power = 0.90, and f2 = 0.15 because 0.05 is the accepted significance threshold, 0.90 provides a conservative safeguard against Type II errors in a novel and noisy research domain, and f2 = 0.15 (Cohen’s medium effect) is an appropriate, theory-driven expectation for behavioural effects in financial decision studies (Cohen, 1988). Under these settings, the required sample size is approximately 99 respondents, which is feasible and ensures adequate sensitivity to detect meaningful medium-sized effects (Mayr et al., 2007). This resulted in a minimum sample of 99 respondents, while this research collected 138 respondents. Although the sample size exceeds the minimum statistical requirement, it remains relatively small compared to Indonesia’s estimated 22.9 million cryptocurrency investors in 2024, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future research should draw on larger and more representative samples to strengthen external validity.

The Ethics Committee of Bina Nusantara University approved this study, which was conducted in accordance with ethical standards, reference number 002/HoP.DRM/I/2025. Prior to their participation, all participants received comprehensive information about the study’s goals, methods, and potential risks. Prior to their involvement in the study, all individuals provided written informed consent.

The research questionnaire consists of two parts: the demographic and psychographic profiles of respondents, and questions related to the research variables. Measurement items of each variable were adopted from the literature. This study considered digital literacy as a second-order construct comprising four dimensions: perceived usefulness (Alomari & Abdullah, 2023), perceived ease of use (Kala et al., 2023), social influence (Kala et al., 2023), facilitating condition (Kala et al., 2023), herding behaviour (Kaur et al., 2023), financial literacy (Alomari & Abdullah, 2023), cryptocurrency investment decisions (Kaur et al., 2023). A 5-point Likert scale was employed to assess the items on the survey.

To incorporate theoretical frameworks and maximise the model’s explanatory power, as reflected in the R2 value, the study’s objective guided the adoption of Structural Equation Modelling with Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM is more suitable for exploratory or predictive research, as well as studies that integrate multiple theoretical viewpoints, in contrast to covariance-based SEM, which focuses on evaluating the viability of established hypotheses (Hair et al., 2019).

Procedural remedies were implemented during questionnaire design to minimise common method bias (CMB). First, psychological separation was introduced by separating the predictor and criterion variables into different sections of the survey. Second, the anonymity of responses and absence of right-or-wrong answers were emphasised to reduce evaluation apprehension. Third, item wording was improved by avoiding ambiguous or leading statements and balancing positively and negatively framed items to reduce acquisition bias. These procedural controls were complemented by a post hoc full collinearity test (Kock, 2015), which confirmed that CMB was not a significant concern.

The statistical analysis employs a two-stage, disjoint approach with reflective-formative modelling for higher-order constructs. This method is particularly effective for handling hierarchical constructs, where the formative higher-order constructions are accompanied by reflected lower-order structures. The justification for using this two-stage approach lies in its robustness for modelling constructs that are reflective at lower levels but operate formatively at a higher level. In this study, the higher-order constructs represent complex phenomena such as digital literacy or cryptocurrency investment decisions, which consist of distinct but interrelated dimensions that collectively influence the overarching construct (Becker et al., 2012).

The initial phase involves evaluating the first-order reflective model of measurement by examining construct reliability, convergent validity (using the AVE), discriminant validity (using HTMT ratios), and indicator reliability. They serve as formative indications for the second-order conceptions after they have been validated. By analysing outer weights and using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess multicollinearity among the formative indicators, the second stage evaluates the formative measurement model. Using bootstrapping, the importance of outer weights is examined to make sure each dimension contributes to the higher-order construct (Hair et al., 2019).

3.2. Operationalization of Variables

The variables in this study were operationalized using established measurement items adapted from prior research. Herding behaviour was measured as the tendency of investors to follow others’ actions in cryptocurrency markets, drawing on items from Kaur et al. (2023). Financial literacy was operationalized as the ability to understand and apply fundamental financial concepts, including risk, return, and investment evaluation, with items adapted from Alomari and Abdullah (2023). Digital literacy was conceptualised as a second-order construct comprising four dimensions adapted from UTAUT: effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. These dimensions reflect individuals’ competence in using, evaluating, and navigating digital platforms for investment decision-making. Measurement items were adapted from Kala et al. (2023). Finally, cryptocurrency investment decisions were measured as respondents’ intentions and actual behaviour regarding cryptocurrency adoption and investment, adapted from prior studies on technology-enabled investment decisions (Zhao & Zhang, 2021). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Operationalisation of the variable is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operationalisation of variable.

4. Results

4.1. Identity of Respondents

Respondents in this study were individuals who met the research objectives’ criteria, specifically retail investors in the cryptocurrency market. The survey was conducted between April and June 2024, yielding 298 responses. After applying screening criteria, 269 responses met the eligibility requirements. Following data cleaning to remove incomplete and inconsistent responses, 138 valid responses were retained for analysis. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identity of Respondents (n: 138).

Based on Table 1, most male respondents (69.89%) indicated that trading activity or interest is more prevalent among men than among women. The dominant age group, 20–29 years (63.06%), indicates that trading is more popular among the younger generation, particularly those at the beginning or middle of their careers.

Most respondents held a bachelor’s degree (71.38%), suggesting that trading is attractive to individuals with higher levels of education. The predominant single status (81.04%) may reflect that unmarried individuals are freer to take risks or have more time to manage their investments.

In terms of experience, most respondents have 2–5 years (36.80%) or 1–2 years (36.43%) of trading experience, suggesting that most perpetrators are new traders still in the exploration and learning stage. The most common trading frequencies are daily (37.17%) and monthly (36.43%), indicating that most traders are active in monitoring and conducting transactions regularly.

For trading limits as a percentage of income, most allocations fall within the 10–20% range (33.46%), indicating that most respondents view trading as an important activity but do not allocate their entire income to it. However, a significant group (22.30%) allocates more than 40% of their income to trading, which could indicate high confidence in their investment returns or a tendency to take greater risks.

4.2. Common Method Bias

Common method bias (CMB) refers to the potential bias that can arise from a study’s independent and dependent variables. It is measured using the same method, particularly in survey research (Kock, 2015). This can affect the internal validity of the research, as it may lead to inaccurate or overly strong relationships among variables due to the use of a single measurement method. Therefore, we performed a standard method bias test using the complete collinearity test method (Kock, 2017). This method involves creating dummy variables that are unrelated to the research variables, regressing all research variables on these dummy variables, and assessing collinearity across variables by calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (Kock, 2015). Kock (2015) states that there are no significant issues if the inner VIF value of each variable is less than the cut-off criterion of 3.3 related to Common Method Bias in the research. The test result is presented in Table 3. In this case, the VIF results ranged from 1.109 for effort expectancy to 2.060 for the cryptocurrency investment decision, indicating that CMB is not a significant problem and does not affect the research results.

Table 3.

Common Method Bias.

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

First, the researcher conducts Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), a method used to evaluate how well empirical data align with a predetermined theoretical model. As part of Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), CFA tests the construct validity by confirming whether the indicators in a lower-order construct truly reflect the intended constructs.

Key stages of CFA in this research include testing outer loadings to gauge the strength of relationships between indicators and latent components, reliability testing to ensure internal consistency, and validity testing for both convergent and discriminant validity. While discriminant validity ensures that constructs are distinct and do not overlap, convergent validity confirms that indicators of a single construct exhibit significant correlations.

In the summarised results (Table 4), internal indicator reliability is assessed using outer loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for convergent validity. The outer loading values should exceed 0.70 to indicate adequate indicator reliability, although values between 0.50 and 0.70 are acceptable in an exploratory study (Shmueli et al., 2019). An internal consistency metric called Cronbach’s Alpha should be higher than 0.60 for exploratory research and higher than 0.70 for confirmatory research to ensure reliability. Composite reliability values should exceed 0.70, with an ideal threshold of 0.80, to demonstrate internal consistency among indicators. For convergent validity, an AVE greater than 0.50 indicates that the construct explains more variance than error variance (Hair et al., 2017).

Table 4.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

In Table 4, we present the indicators we used in our research that have passed confirmatory test analyses, including the outer loading test. Several indicators (FC.3, CID.5) are not valid because their outer loadings are below 0.5, rendering them less representative of the variable/construct.

As shown in Table 4, the mean values for most indicators exceed 4.0 on a five-point Likert scale, indicating that respondents generally strongly agreed with the questionnaire statements. Meanwhile, the standard deviation values above 1.0 suggest a relatively wide dispersion of responses, reflecting varying perceptions and experiences among participants.

All constructs in Table 4 meet the required reliability and validity criteria. The outer loading for all indicators is above 0.5, which remains acceptable. Additionally, all structures’ Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values were above 0.6, indicating sufficient internal consistency. In addition, each construct’s Composite Reliability (CR) value exceeds 0.7, indicating strong and reliable reliability (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016).

We also conducted discriminant validity tests using the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) method. The primary function of HTMT is to determine whether the constructs in the model are more similar to each other than they should be. HTMT does this by contrasting the ratio of correlations within a single construct with correlations across constructs. High HTMT values indicate that the constructs may not have sufficient discriminant validity, meaning they may not actually measure distinct concepts. In contrast, low HTMT values (below 0.9) indicate proper fit, meaning each construct is distinct from the others and each measure something unique in the model. We present the HTMT values in Table 5.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

Based on Table 5, all HTMT values are below 0.9, indicating that the constructs in this model exhibit good discriminant validity. This means that each construct can measure a distinct concept in the model, as defined by accepted criteria for discriminant validity.

After confirming that all indicators for the lower-order constructs (LOC) meet the criteria for discriminant validity, the investigation proceeds to the evaluation of the higher-order constructs (HOC) structural model. At this stage, the relationships among the model’s constructs are examined to determine the significance of their effects. The purpose of the structural model assessment is to evaluate the study hypothesis and confirm the strength of the causal relationship between the variables. The result is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Formative Measurement Model.

Table 6 presents the outcomes of the formative measurement framework. The direct formation of a latent variable from its indicators is characteristic of a formative measurement model, in which each indicator makes a unique contribution and does not correlate with the others. Evaluations are conducted to ensure that there is no multicollinearity between indicators. The results of this model include path coefficients indicating the impact of each indicator on the latent variable, which in turn affects the overall findings of the structural analysis.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is conducted to determine whether the proposed correlations between the model’s constructs are statistically significant. Before proceeding with testing the measuring model for the digital literacy dimensions and variables, it is crucial to ensure validity and reliability in the structural model analysis. This involves assessing the constructs and indicators to confirm that they adequately measure the intended latent variables, using criteria for reflective or formative measurement models. After that, hypothesis testing is conducted using p-values and t-statistics. The alternative hypothesis is accepted if the p-value is less than 0.05, indicating a substantial association between the constructs. The researchers also examined the coefficient of determination (R2) reported in the structural model assessment to evaluate predictive power. In an order construct, an indicator is considered to adequately represent its construct if the p-value < 0.05, indicating statistical significance. Additionally, the absence of multicollinearity is ensured by examining the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF); if the VIF is less than 10, there is no multicollinearity among the indicators.

Digital literacy in this study is conceptualised as a second-order construct composed of four UTAUT dimensions, incorporating Performance Expectancy (PE), Effort Expectancy (EE), Social Influence (SI), and Facilitating Conditions (FC). Prior empirical research has used a similar approach. For example, a longitudinal study of Chinese engineering students applied UTAUT and measured digital literacy adapted to PE, EE, SI, and FC dimensions, showing high reliability and validity (Liu et al., 2025). In another study among administrative staff in higher education, digital literacy was found to be associated with UTAUT constructs, specifically effort expectancy and facilitating conditions, and to have significant effects on technology acceptance (Kabakus et al., 2023). These examples support our operationalisation: digital literacy is understood not only as skills but also as beliefs, social influences, and enabling conditions surrounding the use of technology.

Table 6 presents the findings of these evaluations, which are analysed using a structural model for hypothesis testing. We use a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples. The Bias-Corrected and Accelerated (BCA) bootstrap method was applied to generate more accurate confidence intervals for statistical estimates (Grün & Miljkovic, 2023), using a one-tailed test at the 0.05 significance level. The f2 statistic was used to measure the contribution of exogenous factors to endogenous variables, with effect sizes categorised as high (f2 > 0.15), medium (f2 > 0.01), and small (f2 < 0.01), according to Cohen (1988). To better interpret the findings, combined p-values and effect sizes were employed, following the approach by Lakens (2021).

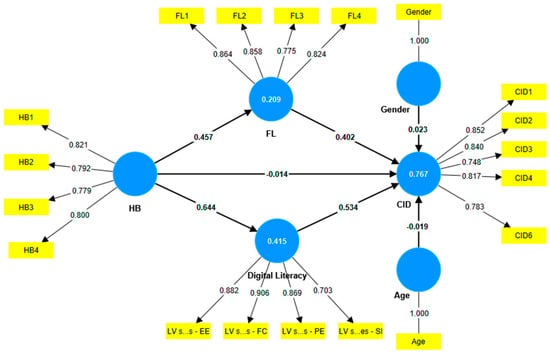

The results of hypothesis testing in Table 7 illustrate various relationships between variables related to investment decisions in cryptocurrency. Herding behaviour positively affects financial literacy (β = 0.457, t = 5.974, p < 0.001), with a large effect size (f2 = 0.203). Herding behaviour has a significantly positive effect on digital literacy (β = 0.643, t = 9.039, p = 0.000), with a substantial effect size (f2 = 0.529). Financial literacy has a strong, positive, and significant effect on cryptocurrency investment decisions (β = 0.443, t = 5.041, p = 0.000), with a large effect size (f2 = 0.182). Digital literacy also significantly influences cryptocurrency investment decisions (β = 0.495, t = 4.246, p = 0.000), with a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.128).

Table 7.

Hypothesis Testing.

The relationship between herding behaviour and cryptocurrency investment decisions shows a weak and statistically insignificant effect (β = −0.016, t = 0.628, p = 0.265), indicating that in this model, herding behaviour has no discernible impact on investment decisions (f2 = 0.003).

The R2 values show that herding behaviour explains 20.9% of the variance in financial literacy and 41.5% in digital literacy. In contrast, financial literacy, digital literacy, and herding behaviour together account for 76.7% of the variance in cryptocurrency investment decisions.

When age group and gender were introduced as control variables, their paths to CID remained statistically insignificant (β = −0.019, t = 0.642, p > 0.05; β = 0.023, t = 0.340, p > 0.05, respectively). This indicates that demographic characteristics do not materially alter investors’ decision-making behaviour in the cryptocurrency context. The model’s explanatory power, therefore, remains primarily driven by cognitive mechanisms underlying financial and digital literacy rather than by demographic differences.

For research models with mediating variables, it is necessary to test the indirect-effect hypothesis (Hayes & Preacher, 2010). With financial and digital literacy as mediating variables, hypothesis testing for indirect effects was also conducted. Table 8 displays the results of the indirect effect test.

Table 8.

Indirect Effect Testing.

Both indirect effects are statistically significant, as indicated in Table 8. Herding behaviour influences cryptocurrency investment decisions through financial literacy, which has a t-statistic of 4.022 and a p-value of 0.000, suggesting a strong indirect effect. Similarly, the finding that herding behaviour influences cryptocurrency investment decisions through digital literacy also shows a significant indirect effect, with a t-statistic of 3.829 and a p-value of 0.000. These findings confirm that both financial and digital literacy effectively mediate the relationship between bitcoin investment decisions and herding behaviour.

Figure 2 provides the SEM path diagram of the tested model, visually summarising the estimated relationships between herding behaviour, literacy, and cryptocurrency investment decisions.

Figure 2.

The SEM path diagram.

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Findings

This study aims to investigate the factors that influence individuals’ decisions to invest in Bitcoin. All antecedents have a moderate predictive power for cryptocurrency investment decisions. This study finds that financial literacy has a slightly greater effect on cryptocurrency investment decisions than digital literacy. Financial literacy significantly influences cryptocurrency investment decisions by equipping investors to evaluate risks, understand market dynamics, and make informed, rational decisions in a highly volatile market. This finding supports the work of Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), who emphasised that financial literacy enhances the capacity to assess investment opportunities and avoid irrational behaviour. This finding is also consistent with Amsyar et al. (2020), who stated that greater financial literacy enables individuals to evaluate opportunities and risks more effectively. In the context of cryptocurrency, where price fluctuations and speculative trends are common, financial literacy is pivotal for investors to discern between potential gains and associated risks.

Digital literacy has a significant impact on cryptocurrency investment decisions, enabling investors to effectively utilise trading platforms, interpret data, and identify credible information sources. This result aligns with the findings of Hartono and Oktavia (2022), who highlighted the importance of digital skills in navigating complex online environments. This finding supports El Hajj and Farran (2024), who demonstrated that mobile technology literacy has significantly boosted cryptocurrency adoption by improving access to digital financial services. For cryptocurrency investors, digital literacy is crucial for accessing tools such as market analysis, price alerts, and secure transactions (Kumari et al., 2023), enabling them to make informed and efficient investment decisions in a digital-first market.

However, this study fails to provide evidence for the direct influence of herding behaviour on cryptocurrency investment decisions, as its impact is mediated by financial and digital literacy, contrary to Gupta and Shrivastava’s (2022) findings, which identified a significant impact of herding on retail investor investment decisions. The initial explanation that the non-significant direct effect may be attributed to Indonesian cryptocurrency investors being predominantly Millennials and Generation Z requires a stronger empirical basis. Recent evidence indeed shows that younger cohorts in Indonesia tend to exhibit higher levels of digital financial capability. Thung and Wihardja (2024) report that Millennials and Gen Z demonstrate comparatively stronger digital financial literacy, particularly in navigating online financial platforms and processing investment-related information. Similarly, Amran et al. (2024) finds that these generations dominate Indonesia’s retail investment landscape and are more familiar with digital investment tools than older cohorts. These studies suggest that younger, digitally adept investors may rely more on their own knowledge and platform-based information when making cryptocurrency decisions, thereby reducing the direct influence of herding behaviour. These individuals tend to rely on analytical tools and self-acquired knowledge rather than merely imitating others’ actions, thereby reducing their direct reliance on herding behaviour (Pangestu & Karnadi, 2020).

However, herding behaviour influences financial literacy by motivating individuals to seek a better understanding of financial concepts, as they observe others engaging in the cryptocurrency market. This finding is consistent with Angela-Maria et al. (2015), who noted that herding can encourage individuals to improve their financial literacy, thereby justifying their investment decisions. Similarly, herding behaviour impacts digital literacy, as it drives investors to learn how to use digital platforms effectively to access information and use digital media (Furinto et al., 2023). This aligns with the research by El Hajj and Farran (2024), which highlighted that social influence often compels individuals to enhance their digital skills to participate effectively in digital markets.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This study contributes to the theoretical development of cryptocurrency investment behaviour by integrating behavioural and cognitive perspectives into a single explanatory model. The findings demonstrate that herding behaviour does not operate in isolation but influences investment decisions through investors’ financial and digital literacy, explaining the mechanism through which socially driven tendencies are translated into actual decision outcomes. This provides empirical clarification to a previously theorised but untested pathway in behavioural finance. Furthermore, by situating the model in a rapidly expanding digital finance context, the study extends the existing literature, which is predominantly shaped by developed-market settings, offering new conceptual insights relevant to emerging economies where technological adoption advances faster than investor capabilities. Collectively, these contributions strengthen the theoretical understanding of how social influence and literacy interact to shape decision quality in highly speculative digital asset environments.

The theoretical novelty of this study lies in integrating Social Learning Theory (SLT) and UTAUT to explain cryptocurrency investment behaviour. The findings extend SLT by showing that herding behaviour acts not only as imitation but also as a mechanism through which investors develop financial and digital competencies. At the same time, the study offers a new application of UTAUT by reframing its constructs as the underlying dimensions of digital literacy rather than direct drivers of technology adoption. This integrated SLT–UTAUT perspective provides a fresh theoretical lens for understanding how social learning processes and technology-related capabilities jointly shape investment decisions in digital asset markets.

This study extends social learning theory by showing that literacy mediates the relationship between social influence and investment behaviour, transforming herd-driven impulses into informed choices. It thus broadens the theory’s relevance to technology-driven financial instruments, underscoring the role of cognitive and skill-based factors in rational decision-making.

5.3. Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, the findings highlight the importance of designing cryptocurrency investment platforms that support informed and rational decision-making. Exchanges and fintech firms should embed user education features, such as risk alerts, simplified asset information, and guided decision-making tools, to help users evaluate crypto assets independently rather than relying solely on market sentiment. Enhancing accessibility to tutorials, platform literacy programmes, and investment analytics can further strengthen investor competence in navigating digital transactions securely and responsibly. In addition, firms may adopt responsible communication strategies by avoiding excessive emphasis on trending assets that could trigger herding behaviour. By implementing these measures, platform providers and industry stakeholders can foster a healthier investment ecosystem that mitigates irrational herding and encourages more sustainable market participation.

6. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of retail cryptocurrency investment by offering an integrated behavioural–cognitive explanation of decision-making in highly speculative digital markets. Rather than viewing herding behaviour and literacy factors in isolation, the findings highlight their interdependent roles, demonstrating that financial and digital literacy serve as essential cognitive mechanisms through which herd-driven influences shape investor decisions. This adds theoretical novelty by empirically validating a previously untested pathway in behavioural finance research. The study contributes to the broader literature by contextualising these insights within an emerging-market environment, showing how rapid digital adoption without commensurate investor capability creates fertile ground for socially driven behaviours. Collectively, the contributions reinforce the importance of literacy-driven empowerment as a strategic foundation for fostering healthier and more rational participation in cryptocurrency ecosystems.

Despite offering meaningful insights, this study is constrained by the inherent boundaries of its research design. The cross-sectional approach captures investor behaviour at a single point in time, limiting the ability to observe how decision-making evolves under changing market conditions. In addition, the exclusive use of quantitative modelling does not fully capture the deeper cognitive and social mechanisms that shape how investors interpret and respond to herd-driven signals.

Future research could expand the sample size to include participants from a broader range of demographics and geographic areas to overcome these constraints and improve the results’ applicability across various investor communities. Qualitative techniques, such as focus groups and interviews, could be used to explore investors’ underlying motivations and thought processes. Furthermore, longitudinal studies would provide a more dynamic understanding of how investor behaviour evolves, especially in response to regulatory shifts or advancements in cryptocurrency technologies. These approaches would deepen the understanding of cryptocurrency investment behaviour and offer practical insights for industry stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.H., A.M.S. and E.H.; methodology, A.M.S.; software, A.M.S.; validation, A.M.S. and E.H.; formal analysis, B.L.H.; investigation, B.L.H.; resources, B.L.H.; data curation, E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.H.; writing—review and editing, A.M.S. and E.H.; visualization, B.L.H.; supervision, A.M.S. and E.H.; project administration, B.L.H., A.M.S. and E.H.; funding acquisition, B.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Bina Nusantara University (No 147/VRRTT/VII/2025, 15 July 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are available on https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14557337 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

- Questionnaire:

- Identity of respondents

- Email:

- Gender:

- __Male __Female

- Education level:

- __High school __Diploma __Bachelor __Master __Doctor

- Age:

- __<20 years __20–29 years __30–39 years __40–49 years __>49 years

- Marital status:

- __single __married __divorced

- Cryptocurrency investing experience:

- __<1-year __1–2 years __2–5 years __5–10 years __>10 years

- Frequency of cryptocurrency investment:

- __daily __weekly __monthly __quarterly __six-monthly __yearly

- Percentage of income invested in cryptocurrencies:

- __no active income __<10% __10–20% __20–30% __30–40% __>40%

- Question related to variables and indicators, using likert scale from 1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree

- Performance Expectancy

- PE1: Cryptocurrency use will increase my chances of achieving my primary objectives

- PE2: I will be able to achieve my objectives more quickly if I use cryptocurrency

- PE3: Using cryptocurrencies will raise my quality of life

- Effort Expectancy:

- EE1: It will be simple for me to learn how to use cryptocurrency

- EE2: Understanding and using cryptocurrencies will not be difficult for me

- EE3: Using cryptocurrency will be easy for me

- Social Influence:

- SI1: Those who influence my decisions think I should invest in cryptocurrency.

- SI2: People I respect give me advice on cryptocurrency investments

- SI3: People who have an impact on my actions agree that cryptocurrency has many advantages

- Facilitating Condition

- FC1: I have access to trustworthy resources regarding cryptocurrency usage

- FC2: I can purchase and trade cryptocurrency on trustworthy and practical platforms

- FC3: I have the technology necessary to use cryptocurrency investment platforms effectively.

- FC4: I can get help or customer service for problems relating to cryptocurrencies

- Financial Literacy

- FL1: I believe that my understanding of cryptocurrency investing is adequate.

- FL2: I feel that I understand how to calculate the profit from index movements in cryptocurrency investments

- FL3: I feel that I understand the nature of the problems with cryptocurrency investment

- FL4: I know how to diversify risk in cryptocurrency investments

- Herding Behaviour

- HB1: Other investors’ crypto choices influence my investment choices

- HB2: My investing choices are influenced by the cryptocurrency volume selections made by other investors

- HB3: Usually, I respond quickly to shifts in the choices made by other investors and observe how they respond to the cryptocurrency market

- HB4: Other investors’ decisions on buying and selling cryptocurrencies have an impact on my investment decisions

- Cryptocurrency Investment Decision:

- CID1: I mostly earn more than the average return generated by the crypto market

- CID2: I decided all of my own cryptocurrency investments

- CID3: My cryptocurrency portfolio’s return validates my investment choices

- CID4: I would use cryptocurrency if I had the option

- CID5: I make all crypto investment decisions myself

- CID6: When an opportunity arises, I intend to use cryptocurrency

References

- Abbad, M. M. M. (2021). Using the UTAUT model to understand students’ usage of e-learning systems in developing countries. Education and Information Technologies, 26(1), 7205–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mansour, B. Y. (2020). Cryptocurrency market: Behavioral finance perspective. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(12), 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A. S. A., & Abdullah, N. L. (2023). Factors influencing the behavioral intention to use cryptocurrency among Saudi Arabian public university students: Moderating role of financial literacy. Cogent Business and Management, 10(1), 2178092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, K. M., Adrianto, F., & Hamidi, M. (2024). Exploring digital literacy, financial literacy, and social media’s impact on cryptocurrency investment decisions. Jurnal Riset Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsyar, I., Christopher, E., Dithi, A., Khan, A. N., & Maulana, S. (2020). The challenge of cryptocurrency in the era of the digital revolution: A review of systematic literature. Aptisi Transactions on Technopreneurship (ATT), 2(2), 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angela-Maria, F., Maria, P. A., & Miruna, P. M. (2015). An empirical investigation of herding behavior in CEE stock markets under the global financial crisis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 25(15), 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. In Englewood cliffs. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. In Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (pp. xiii, 617–xiii, 617). Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S., & Sharma, S. (2001). Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Staff Papers, 47(3), 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S., Karim, S., Naeem, M. A., & Rahman, M. R. (2024). On the prediction of systemic risk tolerance of cryptocurrencies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 198(3), 122963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, E., Gupta, R., & Roubaud, D. (2019). Herding behavioral in cryptocurrencies. Finance Research Letters, 29(1), 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briola, A., Vidal-Tomás, D., Wang, Y., & Aste, T. (2023). Anatomy of a Stablecoin’s failure: The Terra-Luna case. Finance Research Letters, 51(1), 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, A., Şahin, M. A., & Ateş, S. (2016). Impact of financial literacy on the behavioral biases of individual stock investors: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Business and Economics Research Journal, 7(3), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasman, S. (2021). Analysis of return and risk of cryptocurrency bitcoin asset as investment instrument (pp. 1–14). IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- de Best, R. (2023). Estimate of the monthly number of cryptocurrency users worldwide 2016–2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1202503/global-cryptocurrency-user-base/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- El Hajj, M., & Farran, I. (2024). The cryptocurrencies in emerging markets: Enhancing financial inclusion and economic empowerment. Journal of Risk Nad Financial Management, 17(10), 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S., Jennings, N. R., & Wooldridge, M. (2024). Learning to resolve social dilemmas: A survey. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 79(1), 895–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furinto, A., Tamara, D., Yenni, & Rahman, N. J. (2023). Financial and digital literacy effects on digital investment decision mediated by perceived socio-economic status. E3S Web of Conferences, 426, 02076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, B., & Miljkovic, T. (2023). The automated bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals for risk measures. North American Actuarial Journal, 27(4), 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Shrivastava, M. (2022). Herding and loss aversion in stock markets: Mediating role of fear of missing out (FOMO) in retail investors. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(7), 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurdgiev, C., & O’Loughlin, D. (2020). Herding and anchoring in cryptocurrency markets: Investor reaction to fear and uncertainty. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 25, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M. K., & Jasiak, J. (2024). Modelling common bubbles in cryptocurrency prices. Economic Modelling, 139, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, K. W., & Oktavia, T. (2022). The influence of cryptocurrency transaction as a currency in nft-based game transactions. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering, 12(8), 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2010). Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 45(4), 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X., & Hamori, S. (2024). The higher the better? Hedging and investment strategies in cryptocurrency markets: Insights from higher moment spillovers. International Review of Financial Analysis, 95(1), 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, R., & Moin, A. (2023). The influence of financial behavior on capital market investment decision making with mediating of financial literacy in yogyakarta. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(8), 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K. M. A., Omeish, F., Islam, S., Sarea, A. M. Y., & Abdrabbo, T. (2024). Exploring individuals’ purchase willingness for cryptocurrency in an emerging context. Innovative Marketing, 20(2), 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariyapan, P., Mattayaphutron, S., Gillani, S. N., & Shafique, O. (2022). Factors influencing the behavioural intention to use cryptocurrency in emerging economies during the COVID-19 pandemic: Based on technology acceptance model 3, perceived risk, and financial literacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(1), 814087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakus, A. K., Bahcekapili, E., & Ayaz, A. (2023). The effect of digital literacy on technology acceptance: An evaluation on administrative staff in higher education. Journal of Information Science, 51(4), 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, D., & Chaubey, D. S. (2023). Cryptocurrency adoption and continuance intention among Indians: Moderating role of perceived government control. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 25(3), 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, D., Chaubey, D. S., & Al-Adwan, A. S. (2023). Cryptocurrency investment behaviour of young Indians: Mediating role of fear of missing out. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 1, 2047–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M., Jain, J., & Sood, K. (2023). “All are investing in Crypto, I fear of being missed out”: Examining the influence of herding, loss aversion, and overconfidence in the cryptocurrency market with the mediating effect of FOMO. Quality & Quantity, 58(1), 2237–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A. (2025). Digital literacy and retail investing: Exploring market dynamics, efficiency, and stability in the digital era. Journal of Digital Literacy and Learning, 1(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Khechine, H., Raymond, B., & Augier, M. (2020). The adoption of a social learning system: Intrinsic value in the UTAUT model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(6), 2306–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuzaini, Wahyuni, A., Irpan, M., & Setiadi, B. (2024). Investment behavior and strategy in cryptocurrency in Indonesia. Journal of Business and Management Studies, 6(4), 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration (IJEC), 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2017). Common method bias: A full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In H. Latan, & R. Noonan (Eds.), Partial least squares path modeling: Basic concepts, methodological issues and applications (pp. 245–257). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, V., Bala, P. K., & Chakraborty, S. (2023). An empirical study of user adoption of cryptocurrency using blockchain technology: Analysing role of success factors like technology awareness and financial literacy. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 18(3), 1580–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, N. A. (2020). Herding behaviour in digital currency markets: An integrated survey and empirical estimation. Heliyon, 6(8), e04752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. (2021). The practical alternative to the p value is the correctly used p value. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(3), 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakonishok, J., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1992). The impact of institutional trading on stock prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 32(1), 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. (2023). Top crypto exchanges in Indonesia (2023 analysis). Available online: https://www.coingecko.com/research/publications/indonesia-crypto-exchanges (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Liman, U. S. (2025). The financial services authority (OJK) noted that crypto transactions surged 335.91 percent in 2024. Antaranews.com. Available online: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/4642781/ojk-catat-transaksi-kripto-melonjak-33591-persen-pada-2024 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Liu, X., Wang, J., & Luo, Y. (2025). Acceptance and use of technology on digital learning resource utilization and digital literacy among chinese engineering students: A longitudinal study based on the UTAUT2 model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, S., Buchner, A., Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Universität, C. A. (2007). A short tutorial of GPower. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3(2), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, M., & Roger, T. (2014). What drives the herding behavior of individual investors? Finance, 34(3), 67–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, E., Mouakhar, K., & Jarboui, A. (2023). Energy-conserving cryptocurrency response during the COVID-19 pandemic and amid the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Journal of Risk Finance, 24(2), 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadyari, S., & Singh, H. (2015). Understanding the effect of e-learning on individual performance: The role of digital literacy. Computers and Education, 82, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu’izzuddin, Ghasarma, R., Putri, L., & Adam, M. (2017). Financial literacy; strategies and concepts in understanding the financial planning with self-efficacy theory and goal setting theory of motivation approach. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7(4), 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Munkh-Ulzii, Moslehpour, M., & Van Kien, P. (2018). Empirical models of herding behaviour for asian countries with confucian culture. Studies in Computational Intelligence, 753, 464–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestu, S., & Karnadi, E. B. (2020). The effects of financial literacy and materialism on the savings decision of generation Z Indonesians. Cogent Business and Management, 7(1), 1743618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paretta, A., Ameylia, R., & Hendratno, S. (2024, September 26). Analysis of the impact of cryptocurrency loss risks and returns on Gen Z investment decisions. 7th International Research Conference on Economics and Business (IRCEB 2023), Malang, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodpangtiam, A., Boonchutima, S., & Mazahir, I. (2024). Perception of social media users regarding cryptocurrency investment adoption: A case of social media platform—Reddit. Cogent Business and Management, 11(1), 2402513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubasinghe, D. I. (2017). Transaction verification model over double spending for peer-to-peer digital currency transactions based on blockchain architecture. International Journal of Computer Applications, 163(5), 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, A., & Dasmohapatra, A. K. (2020). Impact of behavioral biases on investment decisions: A study on selected risk averse investors in india. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(6), 2408–2425. [Google Scholar]

- Savithri, M., & Rajakumari, D. (2025). Analysis of investment factors and decisions among generation Z and generation X in Indian capital market. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 15(1), 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill builing approch (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Setiyono, Tandelilin, E., Hartono, J., & Hanafi, M. M. (2013). Detecting the existence of herding behavior in intraday data: Evidence from the indonesia stock exchange. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 15(1), 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(1), 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, M., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., Tripathy, N., & Dhir, A. (2021). Has financial attitude impacted the trading activity of retail investors during the COVID-19 pandemic? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Chinh, N., The Anh, K., Nguyen Duc, D., Phuong Kim Quoc, C., & Linh, L. D. (2024). Impact of self-efficacy and mediating factors on Fintech adoption in the VUCA era. Journal of Eastern European and Central Asian Research (JEECAR), 11(4), 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thung, J. L., & Wihardja, M. M. (2024). Understanding the role of indonesian millennials in shaping the nation’s future. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Trisno, B., & Vidayana. (2023). Understanding herding behavior among Indonesian stock market investors. E3S Web of Conferences, 426, 01088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Davis, F. D., & College, S. M. W. (2012). Theoretical acceptance extension model: Field four studies of the technology longitudinal. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., & Zhang, L. (2021). Financial literacy or investment experience: Which is more influential in cryptocurrency investment? International Journal of Bank Marketing, 39(7), 1208–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., Xia, P., Wang, K., & Wang, H. (2024). ScamRadar: Identifying blockchain scams when they are promoting. In J. Chen, B. Wen, & T. Chen (Eds.), Communications in computer and information science: Vol. 1896 CCIS (pp. 19–36). Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.