Abstract

Tax-aggressive behavior by firms can undermine tax revenues, corporate transparency, and overall economic governance. Corporate governance mechanisms are increasingly recognized as critical tools for mitigating such behavior, particularly in emerging markets such as Morocco. This study investigates how corporate governance structures influence the reduction in tax aggressiveness in a developing-country context, while also assessing the moderating role of audit quality. Using financial data from firms listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange, the hypotheses are tested through OLS regression with firm and year fixed effects to examine the impact of board characteristics and audit quality on tax aggressiveness. The results show that the separation of the CEO and chairman roles and larger board size significantly reduce tax-aggressive behavior. Moreover, audit quality strengthens the negative relationship between board size and tax aggressiveness, with higher-quality audits further constraining aggressive tax practices. Additionally, ownership concentration is associated with higher tax aggressiveness, reflected in lower effective tax rates, whereas board independence exhibits no significant association with tax aggressiveness (p-value = 0.500879). Overall, the findings suggest that robust corporate governance and high-quality audits effectively mitigate tax-aggressive practices among Moroccan listed firms. This study contributes novel evidence from the Moroccan context, highlighting governance structures and audit mechanisms most effective at curbing such behavior. Policymakers and regulators are encouraged to promote stronger governance frameworks and enhance audit quality standards, while firms should reinforce these mechanisms to improve tax compliance and transparency

1. Introduction

Tax compliance represents a crucial challenge for Moroccan tax authorities, given the central role of tax revenues, which constitute nearly 90% of the ordinary resources of the general state budget. Globally, the estimated annual tax avoidance and evasion rose to USD 480 billion in 2023. In Morocco, this issue is particularly acute, with an estimated annual tax loss of about USD 9.8 billion (Tax Justice Network (TJN), 2023). This loss is largely attributed to aggressive tax planning and the limited efficiency of administrative collection mechanisms.

However, tax revenue plays a key and decisive role in financing the state budget, which is why it is essential to improve the tax administration’s capacity to collect revenue legally. Among the main tools for ensuring compliance with tax law is external auditing. The primary role of this tool is to ensure taxpayers’ compliance with tax law, as well as to deter any tax evasion or fraudulent behavior that would undermine confidence in tax administration and deprive the budget of substantial resources (Alm, 2019).

This study argues that the Moroccan context offers a distinct theoretical setting. Characterized by high ownership concentration and a civil law heritage, the primary conflict in Moroccan firms is often between dominant and minority shareholders. In this environment, dominant shareholders may use opaque tax strategies to mask rent extraction. Consequently, the effectiveness of internal governance depends heavily on external oversight, which is materialized by a high-quality audit (Mahouat et al., 2025). We posit that this type of external audit does not act in isolation but serves as a moderating force that strengthens internal governance by reducing information asymmetry. The assurance provided by high-quality auditors enhances financial transparency, which directly contributes to reinforcing the board’s capacity to scrutinize tax strategies and constrain opportunistic practices.

According to the literature, the tax strategy of firms is driven by individual executives who shape tax behavior according to their own views and orientation (Dyreng et al., 2010). Among the solutions to curb this phenomenon is the introduction of financial incentives to diminish their opportunistic behavior (Armstrong et al., 2012).

This study investigates whether corporate governance mechanisms reduce tax aggressiveness in an emerging economy and how audit quality moderates this relationship. Using a sample of non-financial firms listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange from 2020 to 2024, we provide novel empirical evidence on the interaction between internal oversight (board characteristics) and external monitoring (audit quality).

First, we provide empirical evidence that corporate governance characteristics reduce corporate tax aggressiveness due to the major role of audit quality, supporting the central hypothesis that corporate governance mechanisms act not only as a disciplining mechanism but also as a tool to enhance business performance and optimize information dissemination among stakeholders. Second, our study offers a nuanced and granular perspective of this interaction by integrating audit quality and demonstrating how they foster or weakens the relationship. Third, it delivers actionable insights for policymakers and tax authorities, highlighting the benefits of corporate governance mechanisms in enhancing data transparency and compliance, curbing tax aggressiveness, and modernizing tax systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 sets the theoretical and conceptual foundation of this study by reviewing the literature on corporate governance and corporate tax aggressiveness. Section 3 details the research methodology, sample selection, and model designs. Section 4 presents and discusses the results. Finally, Section 5 concludes with theoretical and practical implications, in addition to limitations and avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Corporate Governance Mechanisms and Tax Aggressiveness

Corporate governance and corporate tax aggressiveness have become crucial topics of interest for different researchers and practitioners in the field of management sciences. The theoretical foundations of corporate governance can be traced back to the seminal works of Berle and Means (1932) and Coase (1937). Over time, the link between governance and tax behavior has been further developed by several researchers (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Hart & Moore, 1990; Cohen et al., 2002; Aburajab et al., 2019). The primary theoretical framework that explains this relationship is agency theory (Fama & Jensen, 1983), which indicates that corporate governance mechanisms serve to control a firm’s tax behavior.

From this perspective, effective governance mechanisms can help mitigate undesirable practices such as aggressive or risky tax behavior, which may expose firms to legal, financial, and reputational risks. Furthermore, agency theory also highlights the conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders frequently exacerbated by information asymmetries and a lack of transparency.

To address these issues, governance mechanisms such as board independence, audit quality, and capital structure play a pivotal role in limiting corporate tax aggressiveness. In particular, board independence and audit quality (Fama & Jensen, 1983; Bhagat & Bolton, 2008) represent a fundamental element of good governance by promoting transparency, accountability, and enhanced reporting quality, ultimately fostering value creation for the company (Peasnell et al., 2000; Y. Liu et al., 2015).

2.1.1. Effect of the Characteristics of Board of Directors on Tax Aggressiveness: The Moderate Role of Audit Quality

The literature reveals that the relationship between board of directors (BoD) characteristics and tax aggressiveness is complex and sometimes inconsistent (Minnick & Noga, 2010; Lanis & Richardson, 2011; Ogbeide & Obaretin, 2018). Several studies show the non-significant impact of board independence of directors on tax aggressiveness; among these studies, the authors of (Jamei, 2017; Prasetyo & Scouts, 2018) argue that the number of independent directors on the board has no impact on tax aggressiveness.

In the Greek context, Dimitropoulos and Asteriou (2010) demonstrated that board independence positively affects financial performance. However, its influence on tax aggressiveness remains inconclusive. Minnick and Noga (2010) suggest that the role of board independence in tax planning may vary according to the legal and tax framework of each country. Overall, the nature of this relationship appears to depend on both the effectiveness of governance mechanisms and the specific tax legal context.

Regarding the dual role of the CEO and board size, most studies have focused on their impact on firm performance, while their influence on tax aggressiveness—particularly considering the moderating role of audit quality—has received relatively little attention and produced mixed results. For instance, Minnick and Noga (2010) found that CEO duality negatively affects tax management, whereas Halioui et al. (2016) report a significant positive association between CEO duality and tax aggressiveness. Conversely, Abdul Wahab et al. (2017) found no significant relationship between the dual CEO–chairman role and aggressive tax practices.

Audit quality, as a key corporate governance mechanism, can moderate the relationship between board characteristics and tax aggressiveness. It plays a crucial role in ensuring reliable financial reporting and in controlling both accounting and tax-related risks (Klein, 2002; Dridi & Boubaker, 2016; Amara et al., 2025). In the Greek context, Kourdoumpalou (2010) observes that firms audited by Big 4 accounting firms exhibit higher tax aggressiveness, whereas those audited by domestic firms tend to engage less in aggressive tax practices. Similarly, Lanis and Richardson (2011) found that a higher number of non-executive directors is significantly and negatively associated with tax aggressiveness. This effect can be reinforced by high-quality audits, which enhance the credibility and transparency of financial statements, thereby reducing firms’ likelihood of engaging in aggressive tax strategies.

Overall, empirical evidence indicates that board characteristics significantly influence tax aggressiveness, particularly when moderated by audit quality. Several studies also highlight that high audit quality negatively affects tax aggressiveness, suggesting that effective auditing can reduce aggressive tax behavior (Annisa & Kurniasih, 2012).

Based on this evidence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

High audit quality strengthens the positive association between CEO duality and tax aggressiveness.

H2.

High audit quality reinforces the negative association between board size and tax aggressiveness.

H3.

High audit quality amplifies the positive association between board independence and tax aggressiveness.

2.1.2. Ownership Concentration Reduces Tax Aggressiveness

Ownership concentration plays a key role in monitoring the activities of a company’s managerial team, as it is widely recognized as an important mechanism for overseeing managerial decisions. In this context, audit quality can also serve as a moderating factor by enhancing the transparency of financial information and supervising managers’ tax-related behavior, thereby reducing tax aggressiveness. According to Chen et al. (2010), non-family firms tend to exhibit higher levels of tax aggressiveness compared to family-owned firms. This difference is attributed to family firms’ greater concern for corporate reputation and public image, whereas non-family firms are generally more inclined to pursue aggressive tax strategies.

However, the impact of ownership concentration on tax aggressiveness varies depending on the type of firm, distinguishing between family-owned and non-family firms. For instance, Gaaya et al. (2017) found that high audit quality strengthens the negative impact of ownership concentration on tax aggressiveness, indicating that audit quality moderates the relationship between these variables. Moreover, audit quality reduces the incentives for family-owned firms to engage in aggressive tax strategies (Gaaya et al., 2017). Other studies, such as those by Karim (2017) and Cahyono et al. (2016), also confirm that ownership concentration significantly affects tax aggressiveness.

Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4.

Audit quality moderates the positive relationship between ownership concentration and tax aggressiveness.

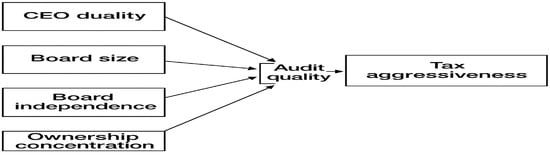

Based on this conceptual model in Figure 1, this study hypothesizes that audit quality plays a significant moderating role in the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and tax aggressiveness. Specifically, H1 proposes that high audit quality strengthens the negative association between CEO duality and tax aggressiveness, suggesting that when a CEO also serves as the board chair, a strong audit function can mitigate aggressive tax behavior. H2 posits that high audit quality reinforces the positive association between board size and tax aggressiveness, indicating that larger boards may facilitate strategic tax planning, and this effect is more pronounced when audits are of high quality. H3 argues that high audit quality amplifies the negative association between board independence and tax aggressiveness, implying that independent boards, together with rigorous audits, can constrain opportunistic tax strategies.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model on the role of corporate governance mechanisms and audit quality on tax aggressiveness. Source: Author’s own contribution.

Finally, H4 argues that audit quality moderates the positive relationship between ownership concentration and tax aggressiveness, suggesting that in firms with concentrated ownership, rigorous audits may strengthen the inclination to engage in tax planning. Importantly, these relationships are investigated for the first time in the Moroccan context, offering new insights into how corporate governance and audit quality interact to influence firms’ tax behaviors in an emerging market setting.

2.2. Determinants of Tax Aggressiveness

The concept of tax aggressiveness refers to the means and strategies employed by firms to lower their tax liabilities (Dunbar et al., 2010). It is situated in a grey area, at the intersection between legal tax planning activities using loopholes in the tax code (tax avoidance) and illegal means referred to as evasion (Kouroub et al., 2022).

The measurement is diverse; they mainly include the effective tax rate (ETR), the cash effective tax rate (CETR), or the book tax difference (BTD), among many other ratios used by scholars (Aronmwan & Okafor, 2019). This shapes the complexity of the concept and sheds light on the debate among scholars about the most meaningful proxy to capture this behavior.

The ETR, as an example, is the most used for its simplicity, but it can be affected by temporary differences. The BTD also presents weaknesses, as it can reflect both legal and aggressive accounting practices depending on the company’s strategy (Xavier et al., 2022).

Among the factors affecting it are corporate governance structure, ownership concentration, and the firm’s own financial characteristics (Hamonangan, 2023). For example, a higher ownership concentration is associated with a higher tax aggressiveness; the presence of independent directors on the board can mitigate it, and bigger firms with complex structures are associated with more tax planning (Boussaidi & Hamed-Sidhom, 2021).

In order to mitigate tax aggressiveness, scholars like Desai and Dharmapala (2006), who focused on the managerial opportunism aspect of tax avoidance and the impact of corporate structure on the proliferation of such strategies, conceptualized solutions like linking the salary of managers to the performance of the company through equity-based packages, in addition to strengthening governance with the inclusion of independent directors on the board and audit committee.

There are also external factors that influence it, like the oversight capacity of tax administration and its use of cutting-edge technologies to evaluate tax risk and enhance its control effectiveness (Amri et al., 2023). The presence of clear laws that prevent and impose severe fines for such transactions also prevents this behavior and contributes to the fairness of the tax system (Prawira & Sandria, 2021). The financial constraints imposed on the firm, such as access to credit, also shape its tax behavior, with firms facing more distress when engaging in more aggressive tax planning (Adela et al., 2023).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

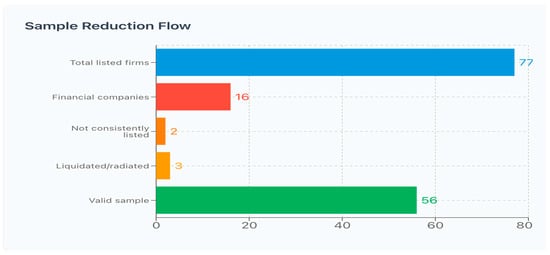

The initial sample for this study comprises all non-financial firms listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange (CSE) over the period of 2020–2024. As portrayed in Figure 2, we excluded financial institutions and insurance companies due to their distinct regulatory and tax frameworks, as well as firms that were delisted or not consistently traded during the observation window. This selection process yielded an initial dataset of 56 firms and 272 firm-year observations. The study period was restricted to 2020–2024 to ensure data consistency and relevance; this timeframe aligns with significant post-COVID-19 regulatory reforms and the acceleration of digitalization under the “Digital Morocco 2030” strategy. Furthermore, comprehensive reporting on governance and tax practices became more standardized only from 2020 onwards. Data were hand-collected from annual reports available on the Moroccan Capital Market Authority (AMMC) website. To mitigate the influence of outliers, continuous variables were trimmed at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Following these cleaning procedures, the final balanced panel dataset consists of 185 firm-year observations.

Figure 2.

Sample screening.

3.2. Model Design

The variables used for the study are defined in Table 1, containing the dependent variable ETR, which is used as a proxy for tax aggressiveness and represents the tax burden of the firm. The independent variables are related to governance mechanisms: ownership concentration, CEO duality, board size, and independence of the board. We also test the moderating effect of audit quality, defined as the presence of a Big 4 auditor, in addition to controlling for firm-specific characteristics like the return on assets, age, leverage, and size.

Table 1.

Variable definitions.

In order to study the effect of corporate governance variables on the effective tax rate, OLS regression with fixed year and industry effects was applied, controlling for a set of variables. The econometric model is presented as follows:

ETRi,t = β0 + β1ROAi,t + β2Sizei,t + β3Levi,t + β4Agei,t + β5Quali,t + β6Duali,t + β7Top1i,t + β8BoardSzi,t

+ β9Indepi,t + εit

+ β9Indepi,t + εit

4. Results

4.1. The Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics in Table 2 show that the ETR takes values between 0.033 and 1.09, which shows diversity in the sample. The ROA also shows the difference in profitability, ranging from −0.028 to 0.1821. The firms also vary in their size, board structure, and ownership concentration. Concerning audit quality, despite being listed on the stock market and being among the bigger firms in the economy, we found that there are companies with no Big 4 signing their financial statements, while others have both auditors being a Big 4 company.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. The Linearity and Correlation Matrix

The VIF values reported in Table 3, together with the correlation coefficients presented in Table 4, indicate the absence of any multicollinearity concerns within the dataset. All variables display VIF scores that fall well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, which is widely recommended in the methodological literature as an indicator of acceptable collinearity levels. This suggests that the explanatory variables are sufficiently independent from one another and that the estimated regression coefficients are unlikely to be biased or unstable due to multicollinearity.

Table 3.

Variance inflation factor (VIF).

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

4.3. The Robustness Test

In Table 5, the baseline results without the interaction term show that ownership concentration (Top1) is negatively and significantly associated with a firm’s effective tax rates (ETR), suggesting that the concentration of shares in the hands of a few shareholders is linked to higher levels of tax aggressiveness. However, when the interaction term between ownership concentration and audit quality is introduced, the main effect of ownership concentration becomes statistically insignificant. Although the interaction coefficient is negative, consistent with the literature that extols the benefits of audit quality on curbing shareholders’ potential abuse of their controlling power, it remains statistically insignificant, rejecting the hypothesis of a moderating effect, even though the interaction slightly improves the explanatory power of the model. Overall, the results suggest that while ownership concentration affects tax avoidance directly, there is no empirical evidence that audit quality moderates this relationship.

Table 5.

Regression with ownership concentration.

Model 1: Ownership concentration and audit quality

- Model 1a: ETR regressed on ownership concentration (Top1) and control variables.

- Model 1b: ETR regressed on ownership concentration (Top1), audit quality (Qual), and interaction term (Top1 × Qual), including control variables.

Model 2: CEO duality and audit quality

- Model 2a: ETR regressed on CEO duality (Dual) and control variables.

- Model 2b: ETR regressed on CEO duality (Dual), audit quality (Qual), and their interaction term (Dual × Qual), including control variables.

In Table 6, the baseline regression shows that CEO duality is negatively and significantly associated with firms’ effective tax rates (ETRs), indicating that when the CEO also serves as board chair, firms tend to engage in higher levels of tax aggressiveness. When the interaction term between CEO duality and audit quality is introduced, the main effect of CEO duality remains statistically significant with a slightly weaker coefficient, suggesting that its influence on tax outcomes remains regardless of audit quality levels. The interaction coefficient is negative, consistent with the notion that higher audit quality lowers the power concentration of leadership, even though the term is statistically insignificant. This lack of significance indicates that audit quality does not moderate the relationship between CEO duality and tax avoidance. Moreover, the inclusion of the interaction provides virtually no improvement in model explanatory power.

Table 6.

Regression with CEO duality.

Model 3: Board size and audit quality

- Model 3a: ETR regressed on board size (BoardSz) and control variables.

- Model 3b: ETR regressed on board size (BoardSz), audit quality (Qual), and interaction term (BoardSz × Qual), including control variables.

In Table 7, the baseline estimation indicates that board size (BoardSz) is positively and significantly associated with a firm’s effective tax rates (ETRs), suggesting that larger boards are linked to lower levels of tax aggressiveness. However, once the interaction term between board size and audit quality is introduced, the main effect of BoardSz becomes statistically insignificant, implying that the influence of board size on tax outcomes depends on the level of audit quality. Concerning audit quality, when introducing the interaction, it becomes statistically significant with a coefficient of −0.19067, meaning that audit quality enhances large boards’ effectiveness in lowering tax aggressiveness. This interaction also increases the model’s overall explanatory power, enhancing it from 0.0732 to 0.0890.

Table 7.

Regression with board size.

Model 4: Board independence and audit quality

- Model 4a: ETR regressed on board independence (Indep) and control variables.

- Model 4b: ETR regressed on board independence (Indep), audit quality (Qual), and interaction term (Indep × Qual), including control variables.

Table 8 reveals that board independence (Indep) is negatively associated with the effective tax rate (ETR), though this relationship is not statistically significant. This indicates that, contrary to expectations, independent directors do not appear to exert a measurable impact on tax aggressiveness. When testing for moderation, the interaction term between board independence and audit quality also proves insignificant. While the negative coefficient might theoretically imply a specific interaction, the lack of statistical significance prevents us from confirming any moderating role. Thus, our findings offer no evidence that audit quality enhances the influence of independent directors on tax practices in this setting.

Table 8.

Regression with board independence.

5. Discussion

Hypothesis (H1) is validated. This study finds that ownership concentration is associated with more tax aggressiveness as defined by a decrease in the effective tax rate. In this concentration, especially when there is weak governance and transparency, the shareholder might deviate from the tax strategy to maximize their private benefit at the expense of the firm’s long-term interest. This is materialized by the entrenchment hypothesis that argues that dominant shareholders can reduce monitoring effectiveness. Kałdoński and Jewartowski (2024) find that ownership concentration, particularly with family firms, increases agency issues, increasing aggressive tax behavior by majority shareholders. The authors find that long-term institutional investors increase this aggressiveness by pushing managers to engage in these activities to maximize the value of the firm, and this aligns with recent evidence from Shahrour et al. (2024), who demonstrate that higher CEO ownership is associated with a focus on private or financial metrics at the expense of broader social and environmental responsibilities. However, authors like Khurana and Moser (2013) find that institutional ownership has a governance role and could reduce opportunistic and opaque managers’ behavior thanks to their long-term vision and the necessity to have transparent financial statements. Our finding that ownership concentration influences tax aggressiveness aligns with Gaaya et al. (2017), who demonstrated that in high-ownership concentration settings (like family firms), audit quality becomes a critical moderator in limiting opportunistic tax behaviors.

This study finds that the separation of the CEO and chairman of the board negatively impacts tax aggressiveness and curbs this behavior. Abd-Elmageed and Abdel Megeid (2020), using a panel of Egyptian listed firms, find the same conclusion, with the separation between the two roles having a negative impact on opportunistic tax behavior, in accordance with agency theory, which posits that too much power in the hands of one actor could lead to a deviation from the long-term goals of the firm. This study’s findings are also in accordance with Armstrong et al. (2015), who argue that dual leadership fosters strategic coherence and accountability, especially in a regulatory environment where high scrutiny is available (Azenzoul et al., 2025).

Concerning the board size, we find that a bigger board is related to less tax-aggressive behavior, with a moderate role of audit quality, as they bring more diverse perspectives and increased monitoring capacity and experience to the company. This argument is supported by Shahrour et al. (2024), who provide evidence that board diversity, particularly female representation, enhances market efficiency and stock liquidity. According to the resource dependence theory, a larger board brings more financial and legal resources to the company, contributing to its compliance with tax regulations. Richardson et al. (2013) find, in their study, that larger boards tend to adopt less aggressive tax strategies because they have more scrutiny and board members with more sophisticated legal and accounting expertise.

Regarding board independence, and contrary to the predictions of agency theory and prior findings by Lanis and Richardson (2011)—who found that firms with a higher percentage of independent directors on their board are more tax-compliant and show less aggressive tax planning—and Minnick and Noga (2010), our results do not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between the proportion of independent directors and tax aggressiveness (p-value = 0.50). This could be attributed to the high ownership concentration in the sample, which could curb the monitoring power of independent members on the board. Furthermore, the interaction with audit quality is also not significant, showing that even with high-quality external auditors, independent directors do not exert sufficient power on tax strategy. The absence of a significant direct link between board independence and tax aggressiveness in our sample reflects the “governance paradox” highlighted in the review by Kovermann and Velte (2019), where governance mechanisms show mixed effectiveness depending on the institutional environment.

This study also finds that the quality of audit, as proxied by the presence of a Big 4 auditor in the company, enhances the negative effect of board size on tax aggressiveness, acting as a catalyst through external oversight. These external auditors complement internal control structures, enhancing the credibility of financial statements and contributing to board scrutiny mechanisms. This is in accordance with the study of Hanlon et al. (2012), who proxied audit quality with audit fees, and they found that firms audited by high-quality auditors tend to engage in fewer tax avoidance activities, with these auditors having higher standards. Khlif and Acheck (2015) emphasize that high-quality external audits contribute to increasing governance effectiveness by reducing information asymmetry and compliant tax disclosures.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the impact of corporate governance mechanisms on tax aggressiveness in the Moroccan context, with a specific focus on the moderating role of audit quality. Consistent with our empirical results, the findings demonstrate that specific governance structures play a role in curbing aggressive tax practices.

First, we find that ownership concentration is a significant driver of tax aggressiveness. When capital is concentrated in the hands of a few major shareholders, firms are more likely to engage in aggressive tax planning, potentially to maximize short-term cash flows at the expense of minority interests. Second, the separation of CEO and chairman roles (CEO duality) proves effective in reducing tax aggressiveness, supporting the agency theory view that dividing power enhances monitoring and reduces opportunistic behavior. Regarding board characteristics, our results show that larger boards are associated with lower tax aggressiveness.

Crucially, we find that audit quality significantly moderates this relationship: The presence of a Big 4 auditor strengthens the monitoring capacity of large boards, acting as a catalyst for effective oversight. However, contrary to expectations derived from developed markets, we found no significant evidence that board independence reduces tax aggressiveness in the Moroccan context. This suggests that independent directors may not yet wield sufficient influence to counterbalance dominant shareholders in this specific institutional setting.

From a practical standpoint, this study provides actionable insights to firms, regulators, and investors. It shows that strengthening corporate governance mechanisms is a necessity for focusing on tax compliance. It also shows the necessity for firms to separate the CEO and chairman roles to reduce opportunism and information opacity, and it calls for larger and more diverse boards to harness the advantage of having a panoply of expertise and experience coming from different backgrounds. The results demonstrate how governance structures serve both as internal and external control mechanisms for mitigating tax aggressiveness.

From a theoretical standpoint, our research aligns with the findings of agency theory, which posits that the divergence of interest between managers and stakeholders, each serving their own personal benefits, can be alleviated by introducing strong and adequate corporate governance structures in order to redirect short-term visions to align with the company’s long-term interests.

This study is not without limitations. Most notably, the final sample consists of 185 firm-year observations after sample screening and outlier treatment, a size constrained by the structural reality of the Casablanca Stock Exchange. While this sample is representative of the listed non-financial sector in Morocco, the limited statistical power warrants caution in generalizing these findings to other markets without further validation.

The limitations of this study include its quantitative nature, which could not fully capture the nuance and behavioral aspect of tax decisions that are also influenced by the psychological characteristics of both managers and shareholders. Future research could delve deeper into the intricacy of the interaction between the concepts and adopt more qualitative approaches by asking stakeholders about their views, incorporating case studies and interviews with auditors, tax inspectors, and investors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M. and A.A.; methodology, N.M., A.A., S.N.S., M.E.-S., K.M. and M.J.; software, A.A.; validation, N.M., A.A., K.M. and M.J.; formal analysis, N.M. and A.A. investigation, A.A.; resources, N.M., A.A., S.N.S., M.E.-S., K.M. and M.J.; data curation, N.M. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, N.M., A.A., S.N.S., M.E.-S., K.M. and M.J.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, N.M., A.A., K.M. and M.J.; project administration, N.M. and A.A.; funding acquisition, M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from the Autorité Marocaine du Marché de Capitaux (AMMC) repository (https://www.ammc.ma). These data were collected from publicly accessible sources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abd-Elmageed, M. H., & Abdel Megeid, N. S. (2020). Impact of CEO duality, board independence, board size and financial performance on capital structure using corporate tax aggressiveness as a moderator. Al Fikr Al Muhasabi (The Accounting Thought), 24(4), 724–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Wahab, E. A., Ariff, A. M., Madah Marzuki, M., & Mohd Sanusi, Z. (2017). Political connections, corporate governance, and tax aggressiveness in Malaysia. Asian Review of Accounting, 25(3), 424–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburajab, L., Maali, B., Jaradat, M., & Alsharairi, M. (2019). Board of directors’ characteristics and tax aggressiveness: Evidence from Jordanian listed firms. Theoretical Economics Letters, 9(7), 2732–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adela, V., Agyei, S. K., & Peprah, J. A. (2023). Antecedents of tax aggressiveness of listed non-financial firms: Evidence from an emerging economy. Scientific African, 20, e01654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J. (2019). What motivates tax compliance? Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(2), 353–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, N., Bourouis, S., Alshdaifat, S. M., Bouzgarrou, H., & Al Amosh, H. (2025). The impact of audit quality and female audit committee characteristics on earnings management: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(3), 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, K., Ben Mrad Douagi, F. W., & Guedrib, M. (2023). The impact of internal and external corporate governance mechanisms on tax aggressiveness: Evidence from Tunisia. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(1), 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annisa, N. A., & Kurniasih, L. (2012). Pengaruh corporate governance terhadap tax avoidance. Jurnal Akuntansi dan Auditing, 8(2), 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, C. S., Blouin, J. L., Jagolinzer, A. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2015). Corporate governance, incentives, and tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 60(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C. S., Blouin, J. L., & Larcker, D. F. (2012). The incentives for tax planning. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 53(1–2), 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronmwan, E. J., & Okafor, C. (2019). Corporate tax avoidance: Review of measures and prospects. International Journal of Accounting & Finance, 8(2), 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Azenzoul, A., Mahouat, N., Mokhlis, K., & Moussaid, A. (2025). Digital transformation and corporate tax avoidance: Evidence from Moroccan listed firms. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, S., & Bolton, B. (2008). Corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(3), 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaidi, A., & Hamed-Sidhom, M. (2021). Board characteristics, ownership nature, and corporate tax aggressiveness: New evidence from the Tunisian context. EuroMed Journal of Business, 16(4), 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, D. D., Andini, R., & Raharjo, K. (2016). Pengaruh audit committee, institutional ownership, dewan komisaris, ukuran perusahaan (size), leverage (DER) dan profitabilitas (ROA) terhadap tindakan tax aggressiveness pada perusahaan perbankan yang listing BEI periode tahun 2011–2013. Journal of Accounting, 2(2). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., & Shevlin, T. (2010). Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family firms? Journal of Financial Economics, 95(1), 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Krishnamoorthy, G., & Wright, A. (2002). Corporate governance and the audit process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(4), 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2006). Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 79(1), 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, P. E., & Asteriou, D. (2010). The effect of board composition on the informativeness and quality of annual earnings: Empirical evidence from Greece. Research in International Business and Finance, 24(2), 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dridi, W., & Boubaker, A. (2016). Corporate governance and book-tax differences: Tunisian evidence. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(1), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontier, P., Chtourou, S., & Ayedi, S. (2006). La qualité de l’audit externe et les mécanismes de gouvernance des entreprises: Une étude empirique menée dans le contexte tunisien. In Comptabilite, controle, audit et institutions. Association Francophone de Comptabilité (AFC). [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, A., Higgins, D. M., Phillips, J. D., & Plesko, G. A. (2010, November 18–20). What do measures of tax aggressiveness measure? Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association (Vol. 103, pp. 18–26), Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2008). Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., & Maydew, E. L. (2010). The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting Review, 85(4), 1163–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaaya, S., Lakhal, N., & Lakhal, F. (2017). Does family ownership reduce corporate tax avoidance? The moderating effect of audit quality. Managerial Auditing Journal, 32(7), 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, L., & Schatt, A. (2005). Caractéristiques et fonctionnement des conseils d’administration français. Revue Française de Gestion, 158(5), 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halioui, K., Neifar, S., & Ben Abdelaziz, F. (2016). Corporate governance, CEO compensation and tax aggressiveness: Evidence from American firms listed on the NASDAQ 100. Review of Accounting and Finance, 15(4), 445–462. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eme/rafpps/raf-01-2015-0018.html (accessed on 18 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hamonangan, S. (2023). Influencing factors tax aggressiveness: Liquidity, leverage, and profitability. Gema Wiralodra, 14(3), 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, M., Krishnan, G. V., & Mills, L. F. (2012). Audit fees and book-tax differences. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 34(1), 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O., & Moore, J. (1990). Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1119–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, R. (2017). Tax aggressiveness and corporate governance mechanisms: Evidence from Tehran stock exchange. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 7, 638–644. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, A. (2017). Faktor-Faktor Yang Berpengaruh Terhadap Tax aggressiveness. Jurnal Ilmu Manajemen Dan Akuntansi Terapan, 8(1), 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kałdoński, M., & Jewartowski, T. (2024). Tax aggressiveness under concentrated ownership: The importance of long-term institutional investors. Finance Research Letters, 65, 105541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlif, H., & Achek, I. (2015). The determinants of tax evasion: A literature review. International Journal of Law and Management, 57(5), 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, I. K., & Moser, W. J. (2013). Institutional shareholders’ investment horizons and tax avoidance. The Journal of the American Taxation Association, 35(1), 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A. (2002). Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33(3), 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourdoumpalou, S. (2010). Estimation of determinants and development of prediction models of tax evasion of Greek listed companies [Doctoral dissertation, University of Macedonia]. [Google Scholar]

- Kouroub, S., & Oubdi, L. (2022). Tax planning: Theory and modeling. Journal of Applied Business, Taxation and Economics Research, 1(6), 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovermann, J., & Velte, P. (2019). The impact of corporate governance on corporate tax avoidance—A literature review. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 36, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanis, R., & Richardson, G. (2011). The effect of board of director composition on corporate tax aggressiveness. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30(1), 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Tian, G., & Wang, X. (2011). The effect of ownership structure on leverage decision: New evidence from Chinese listed firms. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16(2), 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Miletkov, M., Wei, Z., & Yang, T. (2015). Board independence and firm performance in China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 30, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loderer, C., & Waelchli, U. (2010). Firm age and performance (Working paper). University of Bern. [Google Scholar]

- Mahouat, N., Azenzoul, A., Chaiboub, M., Daoudi, L., Lemsieh, H., Aftiss, A., & Mokhlis, K. (2025). Exploratory study on the role of digitalization in improving the external audit quality in public institutions: Evidence from Morocco. Qubahan Academic Journal, 5(3), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, P. J., & Weir, C. (2009). Agency costs, corporate governance mechanisms and ownership structure in large UK publicly quoted companies: A panel data analysis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49(2), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnick, K., & Noga, T. (2010). Do corporate governance characteristics influence tax management? Journal of Corporate Finance, 16(5), 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeide, S. O., & Obaretin, O. (2018). Corporate governance mechanisms and tax aggressiveness of listed firms in Nigeria. Amity Journal of Corporate Governance, 3(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peasnell, K. V., Pope, P. F., & Young, S. (2000). Accrual management to meet earnings targets: UK evidence pre- and post-Cadbury. The British Accounting Review, 32(4), 415–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, I., & Scouts, B. A. (2018). The effect of institutional ownership, managerial ownership and the proportion of independent commissioners on tax aggressiveness. Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting (JEBA), 20, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Prawira, I. F. A., & Sandria, J. (2021). The determinants of corporate tax aggressiveness. Studies of Applied Economics, 39(4), 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G., & Lanis, R. (2007). Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates and tax reform: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(6), 689–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G., Taylor, G., & Lanis, R. (2013). The impact of board of director oversight characteristics on corporate tax aggressiveness: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 32(3), 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrour, M. H., Lemand, R., & Wojewodzki, M. (2024). Board diversity, female executives and stock liquidity: Evidence from opposing cycles in the USA. Review of Accounting and Finance, 23(5), 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tax Justice Network (TJN). (2023). State of tax justice 2023. Available online: https://taxjustice.net/reports/the-state-of-tax-justice-2023/ (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Titman, S., & Wessels, R. (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M. B., Theiss, V. I., & Ferreira, M. P. (2022). Impact of tax aggressiveness on the profitability of publicly traded companies listed on B3. Revista Catarinense da Ciência Contábil, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermack, D. (1996). Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal of Financial Economics, 40(2), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.