Effects of the Recognition, Measurement, and Disclosure of Biological Assets Under IAS 41 on Value Creation in Colombian Agribusinesses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Formulation

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Contextualization of the International Financial Reporting Standards Implementation Process in Colombia

2.1.2. Recognition and Valuation Policies for Biological Assets in the Colombian Context

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Formulation of Hypotheses

2.2.1. Agency Theory

2.2.2. Theory of the Firm

2.2.3. Institutional Theory

2.3. Formulation of Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

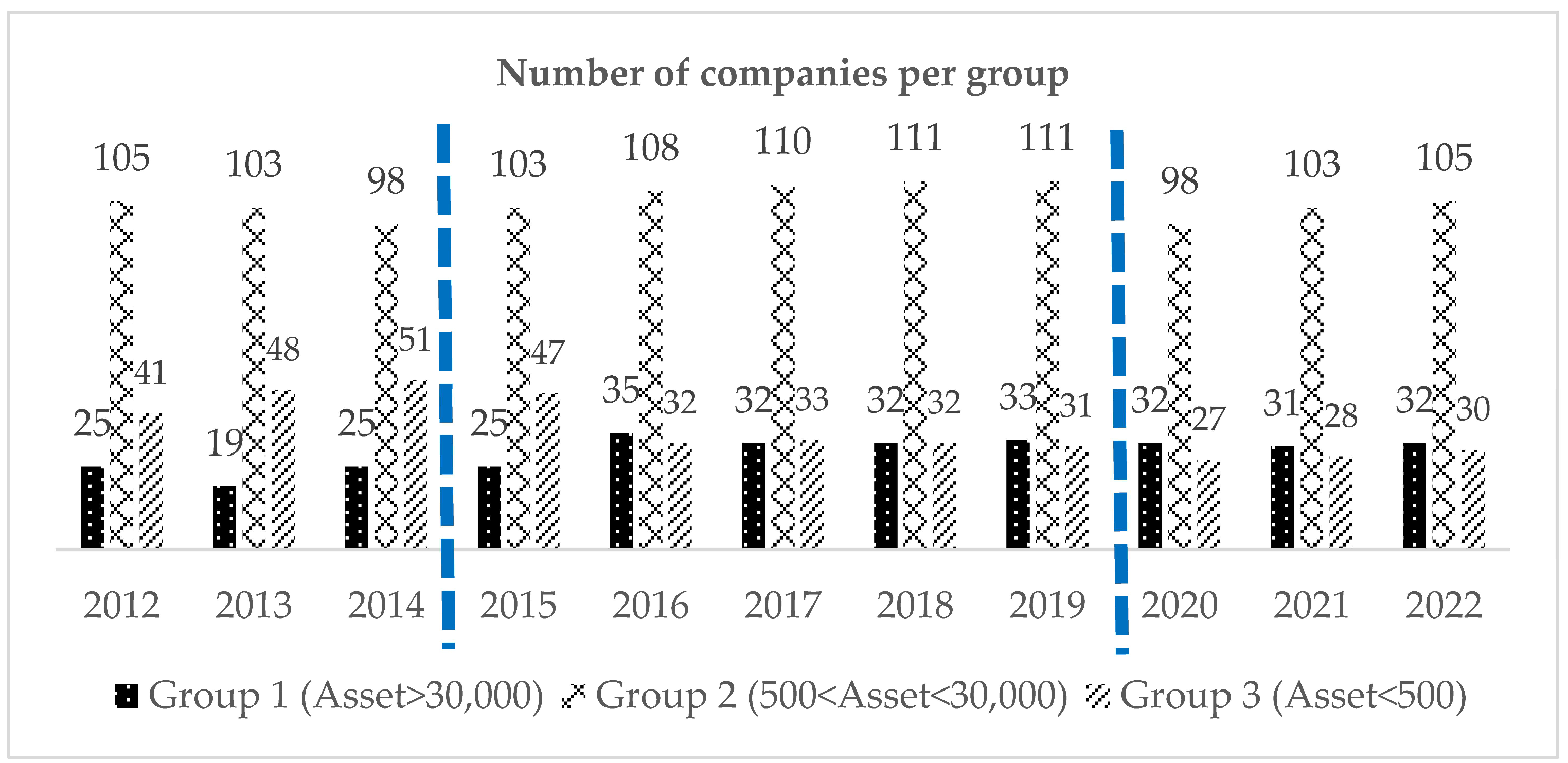

4.1. Sector Description

4.2. Model Selection and Consistency Testing

4.2.1. EBITDA

4.2.2. ROE

4.2.3. ROA

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “Lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés, J. M., Garcia-Blandon, J., & Monllau, T. (2011). Fair value versus historical cost-based valuation for biological assets: Predictability of financial information. Revista de Contabilidad, 14(2), 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés, J. M., & Slof, J. (2000). New opportunities for farm accounting. European Accounting Review, 10(2), 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés-Bosch, J. M., Aliberch, A. S., & Blandón, J. G. (2012). A comparative study of difficulties in accounting preparation and judgement in agriculture using fair value and historical cost for biological assets valuation. Revista de Contabilidad, 15(1), 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés-Bosch, J. M., Miarons, M., Garcia-Blandon, J., Benavente, C., & Ravenda, D. (2018). Usefulness of fair valuation of biological assets for cash flow prediction. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 47(2), 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, A., & Bouaziz, S. M. (2020). The difficulty of measuring biological assets under IAS 41: Agriculture. Revue Du Contrôle, De La Comptabilité Et De l’audit, 3(1), 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baalbaki Shibly, F., & Dumontier, P. (2015). Qui a le plus profité de l’adoption des IFRS en France? Revue Française de Gestion, 41(249), 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B. H. (2008). Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Baltagi, B. H., & Li, Q. (1990). A lagrange multiplier test for the error components model with incomplete panels. Econometric Reviews, 9(1), 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R. (2006). Improving relationships within the schoolhouse. Educational Leadership, 63, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Batca-Dumitru, C.-G., Ilincuta, L.-D., Hurloiu, L.-R., & Rusu, B.-F. (2020). Theoretical study on the accounting treatment prescribed for biological assets and agricultural products by ias 41 agriculture—First part theory. Annals-Economy Series, Constantin Brancusi University, Faculty of Economics, 3, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, N., Desai, H., & Venkataraman, K. (2013). Does earnings quality affect information asymmetry? Evidence from trading costs*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(2), 482–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo, T., & Lopes, A. I. (2022). Exploring the value relevance of biological assets and bearer plants: An analysis with IAS 41. Custos e @gronegocio Online, 18(1), 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Boatright, J. R. (1996). Business ethics and the theory of the firm. American Business Law Journal, 34(2), 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohušová, H., & Blašková, V. (2012). In what ways are countries which have already adopted IFRS for SMEs different. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae et Silviculturae Mendelianae Brunensis, 60(2), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohušová, H., & Svoboda, P. (2016). Biological assets: In what way should be measured by SMEs? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 220, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohušová, H., Svoboda, P., & Nerudová, D. (2012). Biological assets reporting: Is the increase in value caused by the biological transformation revenue? Agricultural Economics (Zemědělská Ekonomika), 58(11), 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A. I., Czaczkes, T. J., & Burd, M. (2017). Tall trails: Ants resolve an asymmetry of information and capacity in collective maintenance of infrastructure. Animal Behaviour, 127, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D., Massoudi, D., Taplin, R., & Tarca, A. (2011). IFRS fair value measurement and accounting policy choice in the United Kingdom and Australia. The British Accounting Review, 43(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameran, M., Campa, D., & Daniele, M. (2025). Does stepping-back from IFRS pay off? Evidence from EUROPEAN unlisted firms’ cost of debt. Finance Research Letters, 85, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos Llerena, L. P., Arias Pérez, M. G., Vayas López, Á. H., & Barreno Córdova, C. A. (2025). Valuation of biological assets and reasonableness of financial information: A systematic review of empirical evidence in the agricultural sector. Sapienza: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 6(3), e25051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Llerena, P., Chávez-Hernández, Z., Jiménez-Estrella, P., & Salazar-Mejía, C. (2025). Application of accounting standards in the valuation of biological assets: An analysis of the poultry sector in Tungurahua, Ecuador. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Técnico de la Contaduría Pública (CTCP). (2012, December 5). Direccionamiento estratégico del proceso de convergencia de las Normas de Contabilidad e Información Financiera y de Aseguramiento de la Información, con estándares internacionales [Strategic direction of the convergence process of accounting and financial information and information assurance standards, with international standards]. Available online: https://cdn.accounter.co/docs/Documentos/Direccionamiento%20dic%20de%202012%20.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Daly, A., & Skaife, H. A. (2016). Accounting for biological assets and the cost of debt. Journal of International Accounting Research, 15(2), 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto 2706 de 2012. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=1482996 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Decreto 2784 de 2012-Gestor Normativo. (n.d.). Función pública. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=75511 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Decreto 3022 de 2013 Nivel Nacional. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=70843 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Decreto 4946 de 2011. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?ruta=Decretos/1554328 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- de Lima, V. S., de Lima, G. A. S. F., & Gotti, G. (2018). Effects of the adoption of IFRS on the credit market: Evidence from Brazil. The International Journal of Accounting, 53(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. W., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 46(4), 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbakry, A. E., Nwachukwu, J. C., Abdou, H. A., & Elshandidy, T. (2017). Comparative evidence on the value relevance of IFRS-based accounting information in Germany and the UK. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 28, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S., Rauter, R., & Baumgartner, R. J. (2016). Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A. M., Ordóñez-Castaño, I. A., & Perdomo, L. E. (2017). Los agentes y la toma de decisiones en las PyMEs frente convergencia a NIIF una observación en seis empresas de algunos sectores en el Valle del Cauca. FACES: Revista de La Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales, 23(48), 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet, G., & Lasserre, P. (2015). The management of natural resources under asymmetry of information. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 7(1), 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigler, F., Kanodia, C., & Venugopalan, R. (2007). Assessing the information content of mark-to-market accounting with mixed attributes: The case of cash flow hedges. Journal of Accounting Research, 45(2), 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R., Lopes, P., & Craig, R. (2017). Value relevance of biological assets under IFRS. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 29, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. Y. (Colly), Wright, S., & Evans, E. (2018). Is fair value information relevant to investment decision-making: Evidence from the Australian agricultural sector? Australian Journal of Management, 43(4), 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, N., Carenys, J., & Moya Gutierrez, S. (2018). Introducing more IFRS principles of disclosure—Will the poor disclosers improve? Accounting in Europe, 15(2), 242–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbohn, K., & Herbohn, J. (2006). International accounting standard (IAS) 41: What are the implications for reporting forest assets? Small-Scale Forestry, 5(2), 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Rodríguez, E. E., & Macagnan, C. B. (2016). Revelación de informaciones sobre capital estructural organizativo de los bancos en Brasil y España. Contaduría y Administración, 61(1), 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera Rodríguez, E. E., & Ordóñez Castaño, I. A. (2019). Intangible resources disclosed in the Panama stock market. Contaduria y Administracion, 64(4), e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houqe, M. N., Easton, S., & van Zijl, T. (2014). Does mandatory IFRS adoption improve information quality in low investor protection countries? Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 23(2), 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. (2014). Analysis of panel data. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS. (2023). Supporting materials for IFRS accounting standards. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/supporting-implementation/supporting-materials-by-ifrs-standards/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- IFRS–IAS 2. (2023). IAS 2 inventories. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-2-inventories/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- IFRS–IAS 8. (2023). Accounting policies, changes in accounting estimates and errors. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-8-accounting-policies-changes-in-accounting-estimates-and-errors/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- IFRS–IAS 16. (2023). Property, plant and equipment. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/supporting-implementation/supporting-materials-by-ifrs-standards/ias-16/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- IFRS–IAS 41. (2023). Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-41-agriculture/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., & Gray, S. J. (2013). Segment reporting practices in Australia: Has IFRS 8 made a difference? Australian Accounting Review, 23(3), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J. (2018). Theories of the firm. International Journal of the Economics of Business, 25(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A. (2014). Decision making by coaches and athletes in sport. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushvakhtzoda (Barfiev), K., & Nazarov, D. (2021). The fuzzy methodology’s digitalization of the biological assets evaluation in agricultural enterprises in accordance with the IFRS. Mathematics, 9(8), 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1994). Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17(1–2), 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P. G. (2016). Why entrepreneurs need firms, and the theory of the firm needs entrepreneurship theory. Revista de Administração, 51(3), 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Swain, S. D. (2014). Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. Journal of Marketing, 78(3), 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley 1314 de 2009-Gestor Normativo. (n.d.). Función pública. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=36833 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Li, B., Siciliano, G., Venkatachalam, M., Naranjo, P., & Verdi, R. S. (2021). Economic consequences of IFRS adoption: The role of changes in disclosure quality*. Contemporary Accounting Research, 38(1), 129–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsen, M. F., & Tronstad, S. (2019). The value relevance of reported biological assets at fair value in the salmon farming industry [Master’s thesis, Handelshøyskolen BI]. [Google Scholar]

- Macagnan, C. B. (2013). Institutional theory: A review of the main representatives of the institutionalist school of economics. BASE-Revista de Administração e Contabilidade Da Unisinos, 10(2), 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A. (2016). The pros and cons of fair value accounting in a globalized economy. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 31(4), 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, V. V., & Arora, J. (2021). Accounting constructs and economic consequences of IFRS adoption in India. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 45, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. T. T., Nguyen, H. T. T., & Van Nguyen, C. (2023). Analysis of factors affecting the adoption of IFRS in an emerging economy. Heliyon, 9(6), e17331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordóñez-Castaño, I. A., Herrera-Rodríguez, E. E., Ricaurte, A. M. F., & Mejía, L. E. P. (2021). Voluntary disclosure of gri and csr environmental criteria in colombian companies. Sustainability, 13(10), 5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orthaus-Wahl, S., Pelger, C., & Erb, C. (2025). When living laws collide: FASB/IASB conceptual framework development as a contested discursive space. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 115, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Breffe. (2019). Experiencias en la aplicación de la NIC 41 Agricultura en países de América Latina. Revista Cubana de Finanzas y Precios, 3(2), 66–76. Available online: https://www.mfp.gob.cu/revista/index.php/RCFP/article/view/08_V3N22019_RPB/08_V3N22019_RPB (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Roh, T., Xiao, S., Park, B. I., & Ghauri, P. N. (2025). Stakeholder pressure, democracy levels, and multinational enterprise corporate social responsibility: Stakeholder and institutional theories. Journal of Business Research, 200, 115619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, S., Shroff, N., & Verdi, R. S. (2019). The effects of financial reporting and disclosure on corporate investment: A review. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 68(2–3), 101246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorolla García, J. (2019). Discussion on the valuation of biological assets: Fair value vs. historical cost. Available online: https://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/187229 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Stiglitz, J. (2000). Capital market liberalization, economic growth, and instability. World Development, 28(6), 1075–1086. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:wdevel:v:28:y:2000:i:6:p:1075-1086 (accessed on 4 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T. (1945). Teoría de la clase ociosa. Revista Mexicana de Sociologia, 7(3), 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-hsin Hsu, A., Liu, S., Sami, H., & Wan, T. (2019). IAS 41 and stock price informativeness. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 26(1–2), 64–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). World Bank annual report 2023: A new era in development. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B., Liu, M., Randhir, T. O., Yi, Y., & Hu, X. (2020). Is the biological assets measured by historical cost value-related? Custos e @gronegócio Online Line, 16(1), 122–150. Available online: http://www.custoseagronegocioonline.com.br/numero1v16/OK%206%20assets.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Zucker, L. G. (1987). Institutional theories of organization. Annual Review of Sociology, 13, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Description | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Issuers of securities or companies listed on the stock exchange, public interest entities which are obliged to render accounts. Its description is large companies which have total assets exceeding thirty thousand legal monthly minimum wages in force, or which have a staff of more than 200 workers, as well as organisations that make 50% of imports or exports of their total operations, as well as if it is a parent or subordinate of a national or foreign company. | Decree 4946 de 2011 Decree 2784 of 2012 |

| Group 2 | Includes SMEs, which are distinguished by the fact that they are not listed on the stock exchange and are not of public interest. They are exempt from submitting financial reports. In addition, they prepare their financial statements in accordance with the SME standard. | Decree 3022 of 2013 |

| Group 3 | These are micro and small enterprises that are expressly authorised to issue their financial statements and the respective disclosures in abbreviated form. The relevant conditions include having assets of less than 500 minimum legal salaries in force, revenues of less than 6000 minimum legal salaries in force and having a staff of less than 10 employees. | Decree 2706 of 2012. |

| Reference | Purpose of the Research | Variables | Causal Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Herbohn & Herbohn, 2006) | Measure the effect on the company’s financial structure when recognising BAs. | Net profit | + |

| Total assets | + | ||

| (Argilés et al., 2011) | Compare approaches across studies companies in the agricultural sector in Spain on the valuation of BAs by historical cost and FV, compared to their financial information. | Net profit | + |

| Total assets | + | ||

| Cash flow | + | ||

| Equity | + | ||

| ROA | + | ||

| ROE | + | ||

| Asset turnover | + | ||

| (Cairns et al., 2011) | Measure the effect on BAs accounting policy choices and financial statement comparability in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia around the adoption of international financial reporting standards (IFRS). | BAs | N/R |

| Equity | + | ||

| (Bohušová & Blašková, 2012) | Measuring the effect on future cash flows and the variation in assets that are variables considered in the research | Profit | + |

| Operating Cycle | - | ||

| Cash flow | + | ||

| (Daly & Skaife, 2016) | Clarify how between the cost of debt and the method of recognition of the BAs are connected. | Debt | - |

| Sales | + | ||

| Total Assets | + | ||

| (Gonçalves et al., 2017) | Clarify fundamental concepts and offer methodological guidance on company size and value creation | Size | + |

| BAs | N/R | ||

| (He et al., 2018) | Measure the effect of the BAs on future operating cash flows. | Net profit | + |

| Cash flow | + | ||

| BAs | + | ||

| (Argilés-Bosch et al., 2018) | Measure the effect on future cash flows. | Sales | N/R |

| ROA | + | ||

| Cash flow | + | ||

| Change in Assets | + | ||

| (Wen-hsin Hsu et al., 2019) | Clarify fundamental concepts and offer practical guidance for the variables of size, leverage, ROA, sales and returns | Size | + |

| Leverage | + | ||

| ROA | + | ||

| Sales | + | ||

| Share | N/R | ||

| Returns | + | ||

| (Sorolla García, 2019) | A comparison of BA valuation models -FV and HC- identifies which more effectively reflect improvements in financial reporting and supports decision-making. | BA Recognition | + |

| (Azhari & Bouaziz, 2020) | Recognition of the FV of the BA | Profit | + |

| BAs | + | ||

| Total Assets | + | ||

| Market value | + | ||

| (Ludvigsen & Tronstad, 2019) | Differences in BA values following the 2005 IFRS adoption in Norway’s salmon industry. | BA Recognition (before 2005) | N/R |

| BA Recognition (after 2005) | N/R | ||

| (Roychowdhury et al., 2019) | to which financial information facilitates the allocation of capital to appropriate investment projects, based on empirical evidence, to reduce information asymmetry. | Market liquidity | + |

| Information asymmetry | - | ||

| (Batca-Dumitru et al., 2020) | Accounting treatment of agricultural products and assets under Romanian Accounting Standards aligned with IFRS—applying IAS 41 Agriculture or, for agricultural products, IAS 2 Inventories. | BA Recognition | + |

| (Xie et al., 2020) | Differences in the market value of Shanghai-listed agro-industrial firms before vs. after biological asset re-recognition. | Debt | - |

| Market value | + | ||

| BA Recognition (before 2007) | N/R | ||

| BA Recognition (after 2007) | N/R | ||

| (Khushvakhtzoda (Barfiev) & Nazarov, 2021) | Fuzzy set–based estimates of BA costs and operational risks in Tajikistan’s agro-industrial enterprises. | Profit | + |

| Total Assets | + | ||

| Market value | + | ||

| BAs | + | ||

| (Meshram & Arora, 2021) | Effects of IFRS adoption, based on International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), on the quality and comparability of Indian companies’ financial reports, focusing on market liquidity and information asymmetry. | Market liquidity | + |

| Information asymmetry | - | ||

| (Ordóñez-Castaño et al., 2021) | Asymmetry in the disclosure of GRI criteria using financial and non-financial information. | Information asymmetry | - |

| Bispo and Lopes (2022). | Relationship between market valuation of shares and accounting information on factories and BAs | BA NIC 41 | + |

| Stages of Accounting Treatment According to IFRS | Definition | Categorical Variables | Category Description | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Includes aspects addressed in IFRS (which are applicable to certain elements of the Financial Statements) or those that are not applicable or are not addressed in the standard. | PPE_Scope Inv_Scope BA_Scope | It corresponds to the entire context of the IFRS system | 1 = Have |

| When the company uses another financial information system | 2 = Does not have | |||

| Initial and final measurement | Process of determining monetary value from which the elements of the financial statements are recognised and accounted for. | PPE_InitMeasur_Field PPE_InitMeasur_Equip PPE_InitMeasur_Plant Inv_InitMeasur BA_InitMeasur PPE_FinMeasur_Field PPE_FinMeasur_Equip PPE_FinMeasur_Plant Inv_FinMeasur BA_FinMeasur | It includes the amount of cash and other items paid, or the fair value of the consideration given in exchange at the time of acquisition. | 1 = Historical cost |

| Estimated sale price of an asset in the normal course of operations less the estimated costs to complete its production and those necessary to carry out the sale. | 2 = realisable value | |||

| It is the discounted value of the net cash inflows expected to be generated by the asset in the normal course of operations. | 3 = Present value | |||

| It is the amount for which an asset can be exchanged on the market. | 4 = Fair value | |||

| When the observed company did not reveal a method of asset valuation | 5 = Not evident | |||

| Recognition | The process of presenting financial information related to the event | PPE_Rev Inv_Rev BA_Rev | These are the comments and explanations found in financial reports, explaining the meaning of the data and figures presented in said reports. | 1 = Explicit |

| When the information in the reports reveals the value, but the explanatory notes do not detail it | 2 = Implicit | |||

| It is not shown in either financial information or the supplementary information of the observed firms. | 3 = Not evident |

| Time | Before 2014 | After 2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | G1 | G2 | G3 | Total | G1 | G2 | G3 | Total |

| Change in assets | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.17 |

| Change in net income | 0.45 | 3.52 | −1.46 | 1.84 | 0.49 | 2.37 | −0.96 | 1.19 |

| Change in equity | 0.13 | 0.22 | 1.31 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.23 | −0.49 | −0.27 |

| Net profit | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.03 |

| ROA | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| ROE | 0.11 | 0.10 | −0.20 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.13 | −0.20 | 0.03 |

| Operating profit | 0.13 | 0.00 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Debt | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.56 |

| Leverage | 0.84 | 1.20 | 3.62 | 1.77 | 1.26 | 1.77 | 5.67 | 2.90 |

| Short-term liabilities | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.69 |

| Operating cycle * | 83.09 | 90.28 | 93.83 | 90.25 | 93.12 | 95.60 | 89.31 | 92.68 |

| Current ratio | 1.26 | 1.46 | 1.66 | 1.48 | 1.19 | 1.51 | 1.18 | 1.29 |

| Explained Variable = EBITDA | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Variables | |||

| Net profit | 0.8666 *** | 0.5174 *** | 0.8091 *** |

| Change in assets | 97.9866 | 89.3518 *** | 204.0139 ** |

| Change in net income | 17.6282 *** | 8.3196 *** | 27.0247 *** |

| Change in equity | 321.2802 | 18.1119 *** | 41.3916 |

| Operating margin | 3242.0262 ** | 3213.7014 *** | 373.4251 * |

| Indebtedness | −20,633.0923 * | −4327.4740 ** | −6101.1137 * |

| Leverage | 41.8719 | 12.5766 | 201.6417 ** |

| Short-term liabilities | 2788.2673 | 11,745.2002 *** | 8619.2248 *** |

| Operational Cycle | −65.6208 ** | −20.0617 *** | −7.1040 |

| Current Ratio | 1323.4591 | 317.4229 * | 284.7860 |

| Working Capital | 0.1249 ** | 0.1116 *** | 0.3659 *** |

| D_BA_Scope | 31,436.7581 ** | 1554.4796 | 703.5211 |

| BA_InitMeasur | 8122.3327 | 1116.4721 | 4760.4637 ** |

| BA_FinMeasur | 36,512.3244 *** | 2377.3877 * | 691.2184 |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_pv | 76,264.7645 *** | 1541.9201 | 640.8598 |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_pv | 78,253.9530 *** | 3341.3153 | 1618.9965 |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_rv | 58,397.8543 * | 2700.8357 | 11,024.6893 |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_rv | 78,204.4062 ** | 5980.4530 | 23,384.7483 * |

| BA_Rev | 363.8037 | 125.8415 | 3457.5060 |

| D_BA_Rev_ex | 14,163.6509 | 2777.9720 | 6631.6394 |

| Explained Variable = ROE | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Variables | |||

| Net profit | 1.5730 × 10−6 *** | 2.4527 × 10−6 * | 8.3300 × 10−6 ** |

| Change in assets | 0.0016 | 0.0003 | 0.0103 ** |

| Change in net income | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 |

| Change in equity | 0.0020 | 0.0001 | 0.0063 * |

| Operating margin | 0.0416 *** | 0.0332 | 0.1681 ** |

| Indebtedness | 0.2833 *** | −0.0928 | 1.6723 *** |

| Leverage | 0.0157 *** | 0.0495 *** | 0.1418 *** |

| Short-term liabilities | 0.0862 | 0.0425 | 0.1670 |

| Operational Cycle | −0.0011 *** | −0.0004 | −0.0006 |

| Current Ratio | 0.0014 | 0.0075 | 0.0182 |

| Working Capital | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| D_BA_Scope | 0.3632 *** | 0.1888 | 0.4546 |

| BA_InitMeasur | 0.1342 *** | 0.0806 | 0.2074 ** |

| BA_FinMeasur | 0.0653 | 0.0371 | 0.2668 ** |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_pv | 0.0574 | 0.2521 | 0.5238 |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_pv | 0.0895 | 0.0540 | 0.2211 |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_rv | 0.1178 | 0.0567 | 1.1935 ** |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_rv | 0.2989 * | 0.5677 * | 0.4511 ** |

| BA_Rev | 0.1165 ** | 0.0540 | 0.3523 ** |

| D_BA_Rev_ex | 0.1481 | 0.3723 ** | 0.4175 * |

| Explained Variable = ROA | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Variables | |||

| Net profit | 5.3311 × 10−7 *** | 8.9200 × 10−7 *** | 1.9800 × 10−6 *** |

| Change in assets | 0.0011 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 |

| Change in net income | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 |

| Change in equity | 0.0015 | 0.0001 ** | 0.0012 ** |

| Operating margin | 0.0258 *** | 0.0211 *** | 0.0095 *** |

| Indebtedness | −0.0306 | −0.1046 *** | −0.0564 *** |

| Leverage | 0.0006 ** | 0.0004 ** | 0.0023 ** |

| Short-term liabilities | 0.0289 | 0.0200 * | 0.0321 * |

| Operational Cycle | −0.0005 *** | −0.0002 *** | |

| Current Ratio | 0.0140 | 0.0023 * | 0.0031 * |

| Working Capital | 0.0000 ** | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| D_BA_Scope | 0.1585 *** | 0.0042 | 0.0789 |

| BA_InitMeasur | 0.0243 * | 0.0197 ** | 0.0168 ** |

| BA_FinMeasur | 0.0484 *** | 0.0203 ** | 0.0479 ** |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_pv | 0.1057 * | 0.0426 | 0.0211 |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_pv | 0.0570 * | 0.0262 | 0.0860 |

| D_BA_InitMeasur_rv | 0.1575 | 0.0292 | 0.1020 |

| D_BA_FinMeasur_rv | 0.1894 *** | 0.0196 | 0.2307 |

| BA_Rev | 0.0036 | 0.0148 | 0.0465 |

| D_BA_Rev_ex | 0.0357 | 0.0492 ** | 0.0544 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ordóñez-Castaño, I.A.; Franco-Ricaurte, A.M.; Herrera-Rodríguez, E.E.; Perdomo Mejía, L.E. Effects of the Recognition, Measurement, and Disclosure of Biological Assets Under IAS 41 on Value Creation in Colombian Agribusinesses. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2026, 19, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010011

Ordóñez-Castaño IA, Franco-Ricaurte AM, Herrera-Rodríguez EE, Perdomo Mejía LE. Effects of the Recognition, Measurement, and Disclosure of Biological Assets Under IAS 41 on Value Creation in Colombian Agribusinesses. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2026; 19(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrdóñez-Castaño, Iván Andrés, Angélica María Franco-Ricaurte, Edila Eudemia Herrera-Rodríguez, and Luis Enrique Perdomo Mejía. 2026. "Effects of the Recognition, Measurement, and Disclosure of Biological Assets Under IAS 41 on Value Creation in Colombian Agribusinesses" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 19, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010011

APA StyleOrdóñez-Castaño, I. A., Franco-Ricaurte, A. M., Herrera-Rodríguez, E. E., & Perdomo Mejía, L. E. (2026). Effects of the Recognition, Measurement, and Disclosure of Biological Assets Under IAS 41 on Value Creation in Colombian Agribusinesses. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 19(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm19010011