Abstract

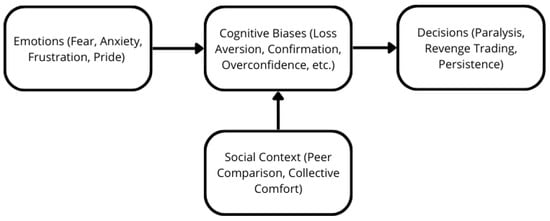

Our paper investigates how emotions and cognitive biases shape small investors’ decisions in a bearish market or are perceived as such. Using semi-structured interviews and a focus group, we analyze the behavior of eight management science students engaged in a three-day trading simulation with virtual portfolios. Our findings show that emotions are active forces influencing judgment. Fear, often escalating into anxiety, was pervasive in response to losses and uncertainty, while frustration and powerlessness frequently led to decision paralysis. Early successes sometimes generated happiness and pride but also resulted in overconfidence and excessive risk-taking. These emotional dynamics contributed to the emergence of cognitive biases such as loss aversion, anchoring, confirmation bias, overconfidence, familiarity bias and herd behavior. Emotions often acted as precursors to biases, which then translated into specific decisions—such as holding losing positions, impulsive “revenge” trades or persisting with unsuitable financial strategies. In some cases, strong emotions bypassed cognitive biases and directly drove behavior. Social comparison through portfolio rankings also moderated responses, offering both comfort and additional pressure. By applying a qualitative perspective—not commonly used in behavioral finance—our study highlights the dynamic chain of emotions → biases → decisions and the role of social context. While limited by sample size and the short simulation period, this research provides empirical insights into how psychological mechanisms shape investment behavior under stress, offering avenues for future quantitative studies.

1. Introduction

Financial decision-making has long been framed by traditional finance, where investors are assumed to be rational agents maximizing utility through systematic cost–benefit calculations (Singh, 2012). Behavioral finance has challenged this view, showing that bounded rationality, emotions and cognitive biases often shape real-world decisions (Pak & Mahmood, 2015; Treffers et al., 2020). Psychological forces frequently drive market behavior, particularly among individual investors who are more vulnerable to emotional pressures (Mouna & Anis, 2015; Tian, 2024).

Emotions such as fear, anxiety or frustration may alter risk perception and encourage defensive choices (Lo et al., 2005; Bishop & Gagne, 2018). Conversely, positive emotions like pride or early success may generate overconfidence and lead to excessive risk-taking (Hutcherson & Gross, 2011; Gosling & Moutier, 2017). Emotions do not always lead to irrationality but rather interact with cognitive mechanisms in ways that can produce adaptive decisions (Matsumoto & Wilson, 2023).

Cognitive biases—including loss aversion, anchoring, overconfidence, familiarity and herd behavior—further influence how investors process information and act in uncertain environments (Konteos et al., 2018; Y. Wang, 2023). Recent work emphasizes that these biases often emerge dynamically under stress, especially when combined with strong emotional responses (Utari et al., 2024). However, most studies rely on quantitative approaches, which can miss the nuanced pathways linking emotions → biases → decisions.

This study adopts a qualitative perspective to explore these dynamics. We conducted semi-structured interviews and a focus group with eight management science students participating in a three-day trading simulation designed to reproduce a bearish context. Our aim is the identification of psychological mechanisms and the lived experiences of decision-making under pressure.

The research question guiding this study is: How do emotions and behavioral biases interact to shape investment decisions in a bearish market simulation, and what role does social context play?

For this purpose, we propose a conceptual framework where (i) emotions act as precursors that result in biases, (ii) biases influence specific decision patterns (e.g., paralysis, “revenge” trading or persistence with unsuitable strategies), and (iii) social interactions moderate these processes. This framework contributes to the literature by highlighting not only what investors feel and do but how and why these dynamics emerge.

2. State of the Art

Traditional finance assumes that investors act rationally to maximize utility. However, this assumption has been increasingly challenged as the evidence shows that decision-making is bounded by limited information, time constraints and cognitive limitations (Simon, 1972; Pak & Mahmood, 2015). Behavioral finance emphasizes how emotions and cognitive biases shape judgment, particularly among individual investors, who appear more vulnerable to uncertainty than institutional ones (Treffers et al., 2020; Tian, 2024).

Emotions are central to financial decision-making. Fear and anxiety increase risk aversion and decision paralysis (Lo et al., 2005; Hassan et al., 2013; Bishop & Gagne, 2018), while frustration or anger can lead to impulsive trades and excessive risk-taking (Lerner & Tiedens, 2006; Hutcherson & Gross, 2011; Yang et al., 2018). Positive emotions, such as happiness and pride, may boost confidence but also generate overconfidence, leading to poor risk assessment (H. Wang et al., 2014; Gosling & Moutier, 2017). Recent studies confirm that emotional dynamics develop rapidly in uncertain markets, influencing both perception and decisions (Matsumoto & Wilson, 2023; Meissner et al., 2021).

Behavioral finance has identified a range of biases relevant to our study:

- Loss aversion and the disposition effect: investors resist realizing losses, extending losing positions (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Fan & Neupane, 2024).

- Anchoring: reliance on initial performance or familiar indicators (Sharma & Firoz, 2020).

- Confirmation bias: selective attention to information supporting prior beliefs (Konteos et al., 2018).

- Overconfidence: overestimating skills and underestimating risks, especially after early success (Y. Wang, 2023).

- Familiarity and herd behavior: preference for well-known assets or imitation of peers (Utari et al., 2024).

While emotions and biases have been studied separately, growing evidence suggests they are interdependent: emotions often act as triggers for biases, which shape decisions (Lerner et al., 2015). For example, fear may result in loss aversion, while pride reinforces overconfidence. Moreover, social context—peer comparisons, rankings or collective discussions—can amplify or mitigate emotional and cognitive effects (Kitzinger et al., 2004; Utari et al., 2024).

Most studies rely on quantitative data, which do not capture the lived experience of decision-making. This research adopts a qualitative approach to investigate how emotions and biases interact dynamically in a bear market context, with attention paid to the moderating role of social context. By focusing on processes rather than outcomes, we provide a complementary perspective to behavioral finance, highlighting the mechanisms through which biases emerge and shape behavior.

3. Selected Methodological Perspective and Data Collection

3.1. Selected General Methodological Perspective

Our study follows a qualitative research design, which remains underused in behavioral finance despite its capacity to capture complex, lived experiences (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Our objective was not to test hypotheses statistically, but to explore how emotions and cognitive biases dynamically interact in stressful market conditions. It is also about studying complex phenomena in their natural environment. Researchers using qualitative methods aim at discovering underlying meanings, patterns and categories from unstructured data, such as interviews, observations and textual analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A key feature of qualitative research is its inductive perspective. Rather than testing a pre-existing hypothesis, the inductive perspective builds theories from the data; in other words, a bottom-up approach, allowing ideas and patterns to emerge from the information collected. The inductive perspective focuses on exploration and flexibility, ensuring that the research reflects the experiences of the participants, rather than forcing a rigid format (Maykut & Morehouse, 1994). Qualitative research is underutilized in finance but crucial to understanding the emotional dimensions of decision-making processes. Our objective is not to quantify the frequency or magnitude of some biases or emotions but to address the interactions and dynamics underlying decision-making in stressful situations, as experienced and interpreted. In the context of behavioral finance, a qualitative approach facilitates the identification of patterns and decisions that would be difficult to accurately capture through statistical measures. For example, the transition from fear to paralysis, or from frustration to a desire for “revenge” are dynamics that only a qualitative analysis can address (Bendassolli, 2013).

Regarding sample size, qualitative research does not aim at generalizing statistically to a larger population (Morse, 2000). Its goal is to gain a deep understanding of a phenomenon, explore lived experiences, identify emerging themes and build a nuanced understanding (Sandelowski, 1995). A small number of participants provides detailed information about each individual and also presents the opportunity to spend more time with each of them, builds trust and explores nuances, contradictions and complexities that quantitative methods would not be able to detect. Qualitative research is an iterative process where data collection and analysis happen in parallel. The questions and the perspective followed are adjusted as new themes arise. A small sample provides flexibility to adapt and explore new avenues of research as the study progresses (Guest et al., 2006).

In short, our results are indicative of psychological patterns and mechanisms at work in a simulated environment and are not intended to be statistically generalized. They could serve as a basis for generating hypotheses that could then be tested quantitatively on larger samples.

For the emotions taken into consideration, the Harmon-Jones et al. (2016) classification was first chosen, with adjustments made to achieve more pronounced polarities for surprise and anticipation: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, anticipation (positive or negative), happiness, surprise (bad or good) and optimism. It should be noted that, based on the analyses carried out, we, secondly, extended the scope of the classifications to consider emotional patterns (such as regret, resignation or abandonment) that were not noticeable in the initial classification (Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Qin, 2015; Frydman & Camerer, 2016).

For biases, we consider availability bias (the inclination of individual investors to rely on readily available information without conducting additional research, Sadi et al., 2011), overconfidence (individuals may overestimate their skills and have an overoptimistic view of their abilities, Y. Wang, 2023), anchoring bias (individual investors make decisions based on a specific reference or piece of information, Sharma & Firoz, 2020), herd behavior (individuals follow the market trend, Utari et al., 2024) and prospect theory (a loss has a greater emotional impact than an equivalent gain, Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Summers & Duxbury, 2012), including loss aversion (the tendency of individual investors to be reluctant to sell losing positions, Shefrin & Statman, 1985; Padmavathy, 2024) and the disposition effect (individuals prefer to sell a winning position and hold on to losing positions in the hope that the stock market trend will reverse, Talpsepp & Vaarmets, 2019; Kiky et al., 2024; Cheung & Rogut, 2024).

3.2. Selected Qualitative Methodological Tools and Data Collection

In order to collect participants’ experiences and perceptions, two qualitative methods were selected. On the one hand, semi-structured interviews were conducted immediately after the simulation by a single researcher with no academic ties to the participants to guarantee open responses (see Table 1). The interviews were organized using a guide with open-ended questions on topics related to biases and emotions and their impact on decision making processes (see Appendix A.2). Semi-structured interviews provide significant flexibility in terms of tailoring the interview to the context and building trust with the participant (Longhurst, 2009). Follow-up questions also help understanding the underlying motivations behind behaviors. Depending on the discussion, new topics may arise, opening up avenues for future research (Oliveira, 2022).

Table 1.

Statistical summary of semi-structured interviews.

On the other hand, focus groups generate context-specific data by collecting different perspectives on an issue. Some authors (Kitzinger et al., 2004) relate focus groups to the psycho-sociological theory of social representations, considering them to be “miniature thinking societies” They can be used to analyze how social representations are constructed, transmitted and maintained through communication. The focus group was organized with all participants at the end of the three days of trading. Participants were asked to express the importance they attached to each of the themes selected and additional questions were asked to collect their feelings (see Appendix A.3). This discussion was designed to encourage them to explain the differences in opinion. A focus group provides insights into social norms (Morgan, 1997), power dynamics and collective decision-making processes that are often difficult to identify in face-to-face interviews. Focus groups are particularly effective for exploring how participants experienced the stock market simulation, by taking advantage of spontaneous discussions. As with the individual interviews, the focus group discussions were recorded (with the participants’ consent) and fully transcribed.

Data triangulation was carried out by cross-referencing information from the two methods. For example, aversion to loss, identified individually in interviews, was given context by group discussions, which revealed the moderating effect of “collective comfort.” Similarly, the overconfidence found in individual narratives was linked to group ranking dynamics.

For both semi-structured interviews and focus group, data analysis was carried out using a dual coding process: Taguette (a free analysis tool) and Maxqda (a paid analysis tool offering more features). The researchers focused on the emotional factors and biases shaping individual investors’ decisions. The two separate tools facilitated a comparison of the results and adjustment of the themes and codes identified, reducing the risk of individual bias and strengthening the robustness of the analysis. In addition, an analysis based on a careful reading of the semi-structured interviews and focus group was also carried out. Even though software can provide an “objective” analysis of information, it was not—from a human perspective—involved in the experiment.

Using a focus group and semi-structured interviews provides a research perspective that helps reduce the weakness of a small sample size (Creswell & Miller, 2000). This combination allowed for cross-validation: the conclusions from the focus group could be examined and deepened during the individual interviews, and vice versa. When similar themes emerged, this convergence reinforced the validity of our findings. At the same time, the dual approach helped identify nuances: differences between what participants expressed collectively and individually revealed nuances that a single method could not have captured. Furthermore, it compensated for the shortcomings of each method. Sensitive or divergent perspectives, which were more difficult to voice in a group setting, were more expressed in private interviews, while the focus group created a “synergy effect” that stimulated ideas that participants might not have formulated without the presence of others.

For the analysis, we conducted a thematic analysis based on the procedure proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). First, we became familiar with the data by repeatedly reading the transcripts of interviews and the focus group. This immersion, complemented by the use of two analysis software programs, provided an overall understanding of participants’ narratives and facilitated the identification of initial ideas regarding the emotions and biases. Second, the interviews were coded line by line in order to assign codes to specific manifestations of emotions and biases, thereby breaking down the discourse into meaningful units relevant to this research. Finally, the codes were grouped to create themes, a step that involved organizing them to highlight the recurrent patterns and central dynamics that structure our analysis.

A final report was produced participant by participant: the analysis was written, explaining the dynamics of each emotion and bias as highlighted through the thematic analysis, illustrating key points with statements.

Concerning reflexivity, we were careful to hold an objective perspective. Using double coding mechanisms (software-assisted and manual reading) for data analysis helped reduce the risk of individual bias. In addition, a single researcher with no academic connection to the participants conducted semi-structured interviews to ensure open responses, which is, according to us, another method of reducing researcher bias.

4. Experimental Protocol

4.1. Participants in This Study

This study was conducted with eight management science students from the University of Mons (Belgium). Although students differ from professional traders, prior research shows they display comparable behavioral patterns under simulated conditions (Abbink & Rockenbach, 2006; Fréchette, 2011). This study was conducted with eight management science students (7 men, 1 woman) from the University of Mons (Belgium). Although students differ from professional traders, prior research shows they display comparable behavioral patterns under simulated conditions (Abbink & Rockenbach, 2006; Fréchette, 2011). Participants received compensation for time spent and a performance-based incentive. We collected demographic data (see Appendix A.1), including age, gender and prior knowledge of stock markets. These variables provide context for interpreting emotion regulation and decision-making styles.

Even though our sample is too small to be statistically representative, in qualitative research, the size of the sample is not based on statistical generalization requirements, but rather on reaching “data saturation” (Morse, 2000; Sandelowski, 1995; Guest et al., 2006; Fusch & Ness, 2015). Saturation is achieved when the additional data collected no longer reveal any new information, themes or perspectives. For our study, the use of two complementary qualitative methods—semi-structured individual interviews and a focus group—facilitated data triangulation, which was used to achieve theoretical saturation.

Using student samples is sometimes questioned because of a potential psychological difference with professional traders (Harrison & List, 2004; Alevy et al., 2022); this choice is widely justified and accepted in experimental finance (Abbink & Rockenbach, 2006; Fréchette, 2011). Participants followed courses in finance, providing them with basic financial knowledge, and the empirical research suggests that students can express behavioral patterns and judgment skills similar to professional traders. As previously said, we restricted the experiment to three days and the sample to eight people due to financial constraints (the students were paid). Moreover, the coordination of a focus group did not allow us to increase the sample size. Focus groups generally consist of 6 to 10 participants (Morgan, 1997). Our sample, built for focusing on psychological mechanisms (emotions, biases) rather than complex trading performance, seems to be well suited to our study.

4.2. Organization of the Experiment

Participants were involved in a trading simulation on the “ABC Bourse” platform. The simulation was based on the French CAC40 index, which the participants were familiar with. Each student was given a virtual portfolio worth EUR 100,000 that they could use to buy or sell shares in companies included in the index. The experiment took place over three consecutive days (from 27 to 29 January 2025), divided into twelve one-hour sessions (no limits were set on the volume or number of transactions). To simulate real market pressure, participants had access to real-time data on the performance of their peers. A non-monetary incentive (a hotel stay worth EUR 200 for the best-performing portfolio at the end of the experiment) was also offered to increase commitment in addition to direct compensation for time spent.

4.3. Stock Market Conditions During the Three-Day Experience

The experiment took place in a market environment characterized by a slight downward trend (see Table 2) and marked by some negative news events (news on DeepSeek, LVMH results, announcement by the Federal Reserve).

Table 2.

Change in reference index over the three days.

Market conditions were experienced very negatively. Even though the stock market was in a bearish configuration, the losses recorded were quite low. The students’ perceptions of a structurally very negative market could be potentially explained by their high expectations and the (false) belief that stock markets are places where significant financial gains could be systematically made.

This perceived bearish context was likely to amplify negative emotions, especially the fear of financial losses and frustration caused by pessimistic signals from the markets. Such an environment is also favorable to the activation of specific biases, such as loss aversion and the disposition effect. The decisions taken cannot be analyzed without considering the perceived bearish climate, a significant factor influencing risk perception, the financial strategies and the process of information assimilation.

5. Results from Semi-Structured Interviews and the Focus Group

Our results are presented according to three main themes (emotions, biases and decision-making), codes (types of emotion, types of bias and decision-making orientation), with illustrative statements underlying each theme and code, distinguishing between semi-structured interviews (SSIs) and the focus group (FG) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews (SSIs) and the focus group (FG).

Table 3 summarizes the themes that emerged from the thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews and the focus group. It illustrates how emotions experienced by participants acted as precursors to specific cognitive biases, which shaped decision-making patterns. Full verbatim excerpts are provided in Appendix A.4 to ensure the transparency of the coding process.

6. Results Analysis and Discussion

Our results are strongly contingent on the size of the sample and the market configuration at the time of the experiment; our qualitative data suggest causal connections without necessarily proving them.

6.1. The Role of Emotions

Emotional reactions connected to market performance and virtual portfolio performance were identified. The majority of participants experienced negative emotions (fear or disappointment) in response to financial losses, with these emotions evolving in response to market uncertainty: market uncertainty triggered many emotional responses, which evolved to a greater or lesser extent over the experiment. These trends and descriptions of emotional states are not a simple confirmation of the existence of emotions, but illustrations of their dynamics and impact on the investor’s experience.

Initially, the decline in the markets generated underlying fear. Gradually, this fear intensified into deep and persistent anxiety. One participant explained, “When the markets started to fall and it didn’t stop, I felt real anxiety. I thought it would never end, that I didn’t know where it would stop. It was total uncertainty and it paralyzed me.” And “When I left for my break or shut down my computer, I felt anxious and fearful about the next day.” For one participant, this anxiety caused nightmares about empty wallets, highlighting the distress he felt. An initial fear could turn into persistent anxiety, even interfering with participants’ sleep.

As time went by, fear also turned into frustration and powerlessness. As a result, the financial strategies became less and less effective as prices continued to fall, sometimes leading to desperate moves. “It was extremely frustrating to see my strategies not working while the market continued to fall. I felt like I was fighting against a wall, unable to do anything,” said one participant, even referring to “complete resignation” or paralysis.

Initial hopes gradually were replaced by growing disappointment. This disappointment gave rise to a lack of motivation. Participants became stuck in a kind of stagnation, where “Nothing was happening. So we lost motivation,” reflecting the gradual decline in their commitment.

At first, success could create positive emotions: “I was number one. It felt pretty good.” Pride could also be a risk factor: “I took the risk because of my pride.” The desire to be first “affected decision-making.” Early successes, even virtual ones, can result in overconfidence and increased risk-taking, driven by ego (Quoidbach et al., 2010).

In summary, our findings show that fear often escalated into anxiety, sometimes resulting in decision paralysis. This observation is consistent with prior research showing that uncertainty-induced anxiety alters cognitive flexibility and generates inaction (Lo & Repin, 2002; Grupe & Nitschke, 2013; Bishop & Gagne, 2018). Similarly, frustration and helplessness were frequent when strategies failed, leading to resignation, in line with learned helplessness (Maier & Seligman, 2016), or to impulsive “revenge” trades, reinforcing evidence that anger and frustration bias decision-making toward riskier or less rational choices (Lerner & Tiedens, 2006; Gambetti & Giusberti, 2012). Positive emotions, such as pride, following early success often generated overconfidence, reinforcing excessive risk-taking (Barber & Odean, 2001; Gosling & Moutier, 2017; Y. Wang, 2023).

6.2. Cognitive Biases at Work

The simulated bear market environment acted as a catalyst for the emergence of several distinct cognitive biases, which significantly shaped the participants’ investment strategies and reactions. A sense of loss aversion was the most prominent finding, with the fear of realizing a loss—even of virtual money—proving to be a powerful paralyzing force (Brown et al., 2024; Yechiam & Zeif, 2025). Participants consistently described an emotional inability to sell depreciating assets, often holding onto losing positions in the hope that the market would rebound and they would not face psychological pain. This behavior was frequently exacerbated by an anchoring bias, where individuals became mentally tethered to specific reference points. For many, this anchor was their initial success or a stock’s purchase price, which distorted their perception of its value and prevented them from adapting their strategy to the downward trend (Chen et al., 2024; Lasfer & Ye, 2024). The anxiety also resulted in a confirmation bias, leading to disproportionately valuing any piece of information that supported their desire for a recovery (Hsu et al., 2021; You, 2025). When participants experience success, this often results in overconfidence. Early gains to overestimate skills and underestimate market risks, resulting in aggressive strategies rather than a defensive posture suitable for the bearish context (Inghelbrecht & Tedde, 2024). This was coupled with familiarity bias, a tendency to favor investing in well-known companies, which limited portfolio diversification and increased exposure to sector-specific risks (Gaar et al., 2022; Dlugosch et al., 2023). Furthermore, the social design of the experiment implied herd behavior. The real-time visibility of peer rankings created social comparisons. This dynamic provided collective comfort during periods of loss and also served as a source of informational influence, where participants looked to the actions of their peers to find hidden clues in an environment of high uncertainty (Chmura et al., 2022; Andraszewicz et al., 2023).

6.3. Impact on Decision-Making

The relationship between emotions and biases influenced decisions and the development of not necessarily relevant strategies. Firstly, faced with powerlessness, many students have withdrawn. “Faced with the decline, I was paralyzed. I didn’t sell, I didn’t buy, I was just in “wait and see” mode. It’s terrible to feel incapable of taking a decision.” The feeling that “there was no point in trying anything” led to “doing nothing” or “cutting everything off” and “leaving your wallet empty” (in other words, containing only cash). Feelings of helplessness lead to withdrawal (“paralyzed,” “wait-and-see,” “empty wallet”). This is a key behavioral finding that is often difficult to quantify. Secondly, the management of losing positions was strongly influenced by loss aversion. While some “cut their losses quickly,” saying, “I cut right away because I thought, no, this isn’t possible,” others “refused to cut their positions, hoping for a rebound.” We found contrasting reactions: some cut their losses quickly, while others refused to do so in the hope of a rebound, thereby exacerbating their losses. The emotional pain of “accepting the loss” is an important qualitative factor. Thirdly, frustration sometimes resulted in irrational decisions: “After a big loss, I would sometimes make very quick moves, without really thinking, just to try and get some of it back. It was impulsive, I knew it wasn’t the right approach, but I was so angry.” Intense frustration and anger can lead to irrational decisions and excessive risk-taking, described as a “vicious circle, an endless cycle”. Finally, anchoring to initial performance and overconfidence prevented some from adjusting their strategy despite negative signals: “I remain convinced that I need to take this risk, and if I’ve taken it, I’m going to stick with it until the end. That’s it. OK. So you’re sticking with this risk until the end, even though I know it could hurt me.” And “In all situations, I tend to hold my position rather than take risks and sell and try something else.”

Our findings contribute to the behavioral finance literature by illustrating how emotions translate into cognitive mechanisms. Specifically, the aversion to losses experienced by participants—often described as more painful than equivalent gains were pleasurable—directly echoes Kahneman’s and Tversky’s prospect theory (1979). The qualitative evidence, with statements such as “This feeling eats away at us. We ask ourselves, ‘Could I have done better?’”, highlights the emotional cost of losses. This dimension is in line with subprior work on the disposition effect (Shefrin & Statman, 1985; Richards et al., 2018) and is consistent with more recent findings documenting investors’ reluctance to sell losing positions (Fan & Neupane, 2024). Beyond confirming established theories, our data show why this bias persists: loss aversion is an embodied affective state that erodes confidence and sustains inaction. This perspective underscores the value of qualitative insights for understanding the mechanisms through which classical biases emerge under stress.

From our results, in most cases, emotions induce biases, which result in specific decision-making patterns. However, in some cases, some emotions directly influence decision-making processes without passing through biases. In times of strong emotional intensity—such as panic in the face of big losses or extreme frustration due to ineffective financial strategies—emotion seems to exert an immediate influence on behavior, bypassing cognitive biases. For example, “decision paralysis” was not always the result of loss aversion, but a direct response to anxiety or strong feelings of powerlessness. This finding suggests that, in extreme market contexts, rationality can be directly overwhelmed by emotions, refocusing the debate on the influence of “raw emotional states”.

7. Conclusions

Our results provide an insight into how emotions or/and biases shape traders’ investment decisions. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and a focus group, allowing for an in-depth exploration of the individual experiences. Although the existence of emotions and biases in behavioral finance has been proven, our study is innovative in showing how these phenomena arise and interact dynamically in a simulated bear market context. Our qualitative perspective illustrates how emotions and biases work and, in some cases, evolve, rather than just simply existing.

A key finding across both studies is that emotions act as forces that actively shape judgment and decision-making. Fear frequently evolved into anxiety under conditions of uncertainty and loss, often becoming a paralyzing influence. Frustration, discouragement and feelings of powerlessness emerged when participants perceived themselves as unable to develop strategies capable of countering market decline.

Although they were less common, positive emotions (happiness after an initial positive trade) were also found. They could result in overconfidence. In all cases, managing emotions emerged as a “necessity” for effective decision-making, with participants realizing that “emotions are not good friends in trading”.

Emotional patterns contributed to the development of the following biases. Loss aversion was particularly strong, as students perceived their virtual losses as real and the emotional pain of accepting them or the fear of losing more made them reluctant to close losing positions, often resulting in a state of paralysis. Furthermore, an anchoring bias became evident through an attachment to the initial positive emotions associated with successful early trades; the subsequent disappointment and demotivation from falling rankings made it challenging for participants to adjust their expectations to the new market reality. This emotional state also contributed to the emergence of a confirmation bias, as students actively looked for information that validated their hopes for a market recovery, even when the underlying signals were negative. Finally, overconfidence, driven by the satisfaction of early success, leads to underestimating the risks of the bearish context and persisting with inappropriate strategies. Other biases were present even if less well-documented: familiarity bias (focusing on well-known companies), the use of heuristics (relying on intuition) and availability bias (relying on easily available information).

The interaction between emotions and biases had consequences on trading decisions. Decision-making paralysis and resignation were common behavioral responses to feelings of powerlessness. Some participants even preferred to “let their wallet empty” (only cash) or “avoid looking at it for hours”. Loss management was also strongly influenced by loss aversion, leading either to quick cuts to avoid emotional pain or, more often, to a reluctance to accept losses in the hope of a rebound, thereby increasing losses. Moreover, impulsive decision-making and the desire for “revenge” on the market, explained by intense frustration and feelings of anger, prompted some to take excessive risks. The persistence of inappropriate strategies was found in participants who focused on their initial performance or overconfident, preventing them from adjusting their strategy despite the trend.

In addition, other factors were identified as influencing decision-making: The social context had a significant impact, as the ranking generated a dynamic of social comparison that influenced motivation and stress. However, collaboration reduced anxiety and facilitated information sharing, making the group a place of comfort, and theoretical implications could be highlighted. This collective comfort, from a shared negative experience, potentially moderates the intensity of loss aversion by making losses more “acceptable” than if suffered alone. Furthermore, this social dynamic underscores the concept of bounded rationality, demonstrating how the psychological need to conform can often override rational analysis. Group dynamics can amplify irrational decisions or promote a kind of “collective resilience” that helps participants. Moreover, financial performance—specifically, unmet financial expectations and the decline in the portfolio’s value—exerted a strong influence on the emotional state, motivation and decisions.

Our analysis demonstrates that staying rational in a bearish context is difficult because emotions and biases are at play. Emotions often overcome rational analysis, leading to cognitive biases and paralysis in decision-making, impulsiveness or the persistence of irrelevant strategies. Our findings are consistent with behavioral finance, moving from the traditional view of investors as “purely” rational agents. Our results also suggest that emotions and cognitive biases are key components of decision-making processes, particularly in a bearish context. We believe that rationality can be defined as a combination of emotional and logical dimensions in the management of risk, rather than being purely “homo economicus.” The originality of our study lies in its qualitative process-oriented approach, which reveals the chain of mechanisms linking emotions, biases and decisions under stress. Our findings explain when and how these biases emerge, evolve and sometimes dissipate. This dynamic perspective complements quantitative studies that typically focus on outcomes rather than processes.

In conclusion, we showed how emotions and biases play out and interact in a stressful context. As summarized in Figure 1, our study does not aim to provide generalizable conclusions, but rather to:

Figure 1.

Conceptual schema of emotional–bias dynamics in market contexts.

- Generate hypotheses: emotional and behavioral mechanisms identified qualitatively can be used as a basis for future quantitative studies;

- Identify mechanisms: we highlight how emotions and biases influence decisions, providing insights into the underlying cognitive and emotional processes;

- Illustrate complex decisions: decision paralysis, revenge bias and the perseverance of inappropriate strategies are complex behaviors that are extensively described and put into context by our qualitative data.

8. Limitations of This Study

Our findings must be considered in light of several limitations. First, the small sample size (eight participants) and the qualitative nature of the research mean that the results are not intended for statistical generalization. The objective was to achieve “theoretical saturation,” where new data no longer yield new thematic patterns. The use of two complementary methods allowed for data triangulation, enriching the density and depth of the analysis. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted as exploratory of the psychological mechanisms at work within the specific context of a bearish context, serving as a basis for generating hypotheses to be tested quantitatively on larger samples in the future.

Second, the use of a student sample from management science, rather than professional traders, raises a question of external validity. Experienced traders are likely to possess more financial knowledge, refined risk-management strategies and potentially better emotional regulation techniques developed through repeated market exposure. Their reactions to a bearish context might therefore differ. However, the selection of students was a deliberate methodological choice for this study. The primary goal was to examine the fundamental psychological mechanisms believed to be universal components of human decision-making under uncertainty. Students, with basic financial knowledge, provide a “clean” sample less influenced by professional heuristics, thus offering insights into the basic architecture of biases, even if their expression may vary with expertise.

Third, although conducted in a simulated environment with virtual money, this study’s ecological validity is supported by the fact that participants perceived their virtual losses as real. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the absence of real financial consequences means that the intensity of emotions and the magnitude of biases might be different in a real-world trading context where actual capital is at risk.

Fourth, the short duration of the experiment necessarily compresses the emotional and behavioral timeline inherent to investing. This study captures acute, initial reactions to stress and loss, but cannot observe how these dynamics evolve over a longer period. Participants might have developed different coping strategies with more time. This short timeframe was a deliberate choice to intensify the experience of a bearish context, which was precisely the condition this study aimed to investigate.

Finally, this research focused exclusively on a bearish context. Therefore, the conclusions regarding the predominance of negative emotions and specific biases, like loss aversion, are specific to this environment. They cannot be extrapolated to bull, stable or highly volatile markets, where the interplay of emotions and biases might manifest differently.

9. Further Research Avenues

Future research should seek to validate the biases and emotional responses identified through quantitative methods. For example, emotions could be measured using physiological indicators, such as heart rate during market fluctuations, while specific biases could be quantified through controlled experimental tasks. Such an approach would allow the statistical validation of the relationships observed qualitatively, addressing the issue of generalizability and facilitating the transition from identifying mechanisms to quantifying their impact. Beyond methodological reinforcement, comparative studies across different market environments would also be valuable. Since our analysis focused on a bearish context, future research could examine investor behavior in bullish, stable or highly volatile contexts. This would shed light on the extent to which emotions and biases are context-dependent.

Another direction could involve comparing novice and professional investors. Our participants often displayed reactions such as paralysis or resignation in the face of losses. More experienced traders, having developed strategies to regulate emotions, may exhibit different dynamics. Exploring these differences would provide insights into the role of adaptation in financial decision-making. Finally, the influence of social context deserves greater attention. Our findings suggest that collective comfort and social comparison affected participants’ emotional and cognitive responses. Investigating the contrast between an individual and a group could help us understand how social dynamics moderate the impact of emotions and biases. By linking these research avenues to the limitations of our study, we propose a roadmap that can guide progress in understanding the psychological foundations of financial decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.; investigation, A.F., K.K. and J.L.; resources, K.K. and J.L.; data curation, K.K. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F., K.K. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, A.F., K.K. and J.L.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, A.F.; funding acquisition, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Walloon-Brussels Federation (Belgium) through a Concerted Research Action (Grant Number: ARC-25/29 UMONS5).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as the research involved minimal risk to participants and data were collected anonymously through a simulation-based educational activity.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper. Participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the simulation, and participation was voluntary.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

| ID | Gender | Age | Prior Trading Experience | Participation in Trading Contests | Self-Rated Financial Knowledge | Notes |

| I.1. | Male | 21 | None | No | Moderate | – |

| I.2. | Male | 22 | Limited (personal trading apps) | Yes (1 contest) | High | – |

| I.3. | Male | 23 | None | No | Low | Expressed strong anxiety |

| I.4. | Female | 21 | None | No | Moderate | Only woman in the group |

| I.5. | Male | 22 | Limited (crypto trading) | Yes (2 contests) | High | Displayed strong overconfidence |

| I.6. | Male | 21 | None | No | Moderate | Initially optimistic, later resigned |

| I.7. | Male | 22 | Limited (virtual portfolio practice) | No | Moderate | Strong emotional reactivity |

| I.8. | Male | 23 | None | No | Low | Reported feelings of abandonment |

Appendix A.2. Guide for Semi-Structured Interviews

Availability Bias

- Can you tell me about your research on the companies you wanted to invest in?

- What kind of information did you look for?

- What type of information did you prioritize?

- How has information accessibility impacted your operations?

Overconfidence

- How do you rate your trading skills?

- How did you feel after a successful series of moves?

- How has this influenced your trading behavior?

- Do you think you underestimated the risks at times?

Anchoring Bias

- When you decided to sell a stock, how did the price you bought it at influence it?

- How have past price levels influenced your decisions?

- Why did the initial purchase value prevent you from adapting to new information?

Herd Behavior

- What was the main influence on you choosing one action over another?

- How have general trends influenced your decisions?

- How did you react to market movements in situations of high activity?

Prospect Theory

- What would you do if you had a winning stock or a losing stock in your portfolio?

- What were your motivations for selling winning positions, even though they could still bring you additional profits in the future?

- What were your motivations for maintaining a losing position?

General Emotions

- In your opinion, what role did emotions play in this experiment?

Emotions Changes

- After a session where you made several decisions that were unsuccessful, how did you react emotionally and how did this influence the next session?

- Have you noticed changes in your emotions or behaviors when you have several successive losses?

- Do you feel like your emotions have changed the way you’ve structured your strategy over time?

Impact of Emotions on Decision-Making

- Before placing an order, what emotions did you usually feel?

- Can you describe a situation where your emotions directly influenced your decision-making, whether in a losing or winning situation?

- Have there been times when, despite feeling stressed or anxious, you were able to make a successful decision?

- Do you feel like your emotions have changed the way you’ve structured your strategy over time?

Reactions to Gains or Losses

- How did you react to loss?

- Have the losses affected your behavior or decisions?

- How did you react to a gain?

- Did you react more impulsively afterward?

Emotion Management

- How did you handle the pressure of making decisions quickly?

- Did the fact that there were breaks between each session influence your emotions?

Appendix A.3. Guide for the Focus Group

Emotional Influence on Decision-Making

- How important do you think the influence of emotions on decision-making is?

- What do you think are the positive/negative effects of emotions on your decision-making?

- When you decide to close a position, which emotions (among those displayed on the board) influence this decision?

- When you decide to buy stocks, which emotions (among those displayed on the chart) influence this decision?

Cognitive and Behavioral Biases

- Do you think that recent or high-profile events influence your decisions more than less visible but relevant facts?

- Do you think some choices seem more likely or valid just because they resemble what you expect a good decision to be?

- Have you ever felt very confident about a decision, only to find that you underestimated some of the risks?

- When taking a decision, do you sometimes remain influenced by the initial information you receive, even in case of new data?

- Do you think you often use your intuition in your investment decisions? If so, why?

- Do positions with extreme gains or losses influence your behavior?

- Would you rather sell a losing stock or a winning stock? Why?

Investment Decisions

- Please briefly describe an important decision made during the experiment and the main factors that influenced their choice.

- What do you think makes a good investment decision?

- Do you think your financial performance triggers any particular emotions? Have these emotions led you to rethink your approach to trading?

Appendix A.4. Complete Thematic Analysis of Semi-Structured Interviews (SSI) and Focus Group (FG)

| Student | Emotions | Biases | Decision-Making Process |

| I.1. | Emotions were strongly linked to stock market performance, fluctuating between happiness (code 1) and disappointment (code 2). He said: “Our mood depended on the stock market and the shares we had bought. If they went up, we were happy; if they went down, we were a little disappointed.” (SSI) “When we made a profit, we felt happiness, satisfaction and pride.” (FG) “Whether we made a profit or a loss, I still felt anxious.” (FG) “The next day, I felt anxious and afraid. Because I thought, that’s it, it’s over, there’s nothing I can do now.” (FG) | A strong loss aversion (code 1) was present, perceiving virtual losses as real: “This feeling eats away at us. We ask ourselves: ‘Could I have done better? Did I make the right choice? What if…?’” (SSI) “We say to ourselves it’s just a simulation. But inside, it’s not just a simulation, because we want to perform, we want to be the best. And it’s that feeling, that desire, that drives us.” (SSI) | Faced with losses, the student chose to cut his losses (code 1) by closing his positions and adopting a resigned attitude: “I bought shares at the very beginning and then I saw that they weren’t moving much because the market was down. Then I saw that we were losing money, so I cut my losses.” (SSI) “We decided to cut our losses and go into passive mode. And we’ll see if we can do anything else.” (SSI) |

| I.2. | The student experienced fear turning into anxiety (code 1a) in response to the continuing market decline and uncertainty: “When the markets started to fall and it didn’t stop, I felt real anxiety. I thought it was never-ending, that I didn’t know where it would stop. It was completely unknown and it paralyzed me.” (SSI) Fear turned into frustration and a feeling of helplessness (code 1b) also emerged: “It was extremely frustrating to see my strategies not working while the market kept falling. I felt like I was fighting a wall, unable to do anything.” (SSI) | A pronounced loss aversion (code 1) prevented him from reducing his positions in the hope of a rebound: “When I saw the losses mounting on my positions, I found it very difficult to reduce them. I kept waiting for a rebound, even when all the signs were pointing to a fall.’ It was unbearable to accept the loss, even though I knew it was only virtual.” (SSI) Confirmation bias (code 2) is evident in the search for positive information to validate hopes of a recovery: “I started looking for articles and analysts who said the market was going to rebound, even though the majority said the opposite. I wanted it to go back up so badly that I clung to every little bit of positive news.” (SSI) “If I see something that confirms my idea, I think that news will have a certain impact, and if I see other news that confirms it, it will have a confirmation bias.” (FG) | His reaction was decision paralysis (code 1): “There were times when I just couldn’t look at my portfolio for hours. I didn’t know what to do, I was overwhelmed, so I did nothing. I hoped it would sort itself out.” (SSI) and impulsive decision-making (code 2) or “revenge” strategies after big losses: “After a big loss, I would sometimes make very quick moves, without really thinking, just to try to recoup a little. It was impulsive, I knew it wasn’t the right approach, but I was so angry.” (SSI) |

| I.3. | Being at the top of the rankings generated feelings of happiness (code 1) and satisfaction: “I was in first place. It was quite a thrill. What’s more, I knew I was going to win, but I also knew I was taking a big risk because I was already in first place on the second day, and I said to myself, either I cut everything out and stay in first place, or I go for it. But I took the risk because of my ego.” (SSI) He also expressed fear (code 2): “I even dreamed that my accounts were empty. It was stressful not knowing where things were going.” (SSI) | A strong loss aversion (code 1) and a belief that prices always come back led him to hold on to losing positions: “I didn’t want to cut my losses. I don’t really like that. Because for me, the price always comes back.” (SSI) “But anyway, in three days, there was little chance that the price would return to its previous level, but I still hoped it would. That’s what you shouldn’t do, hope.” (SSI) Overconfidence (code 2) linked to his ego and initial performance encouraged him to maintain a high-risk stance: “I remain convinced that I have to take this risk and that if I’ve done it, I’ll continue to do so until the end.” (SSI) “It’s important not to be self-deprecating, to be confident, and to take mitigated risks.” (FG) | The student was caught in a vicious cycle of impulsive decision-making (code 1) and “revenge,” taking more risks after losses: “Then you try to take more risks. And you try to get revenge. And then it’s even worse. It’s a vicious cycle, it’s a never-ending cycle.” (SSI) He admitted that he mismanaged the size of his positions, leading to accelerated losses: “Or sometimes I get the position size wrong. Then the market moves 10 times faster. And it’s very difficult, because it’s really strange. I mean, the blood rushes to your head. You think, ‘Oh, what am I doing?’” (SSI) Confirmation bias led him to reinforce his winning positions: “And often, when I get my confirmations, I get back into the position to increase the risk a little bit, and the risk paid off because I went up to 4%, I think.” (SSI) |

| I.4. | The student began with optimism (code 1): “I have a week off, so there’s no reason I can’t do this. Instead of staying at home or doing something else, why not do this during the week?” (SSI) The inactivity of the market quickly turned into fear (code 2), frustration, helplessness, and a lack of motivation: “But nothing was happening. So we lost motivation.” and “We were there. Disappointed.” (SSI) | An anchoring bias (code 1) was observed, with disappointment arising when the situation did not improve despite initial investment: “I tell myself that there’s nothing more to be done, because it’s the last day, and you’ve seen the stock market, there’s going to be no miracle.” (SSI) “I would prefer to anchor myself to something I know, such as indicators, because I believe they slightly improve performance. In the end, it was the only thing I could base my decision on.” (FG) | Emotions and bias led to decision paralysis (code 1) and resignation, with the student feeling that there was nothing left to do in the absence of a market miracle: “We realized that, well, there was nothing else we could do.” (SSI) |

| I.5. | The student experienced fear (code 1) of losing his money, even if it was virtual, which he found “frustrating”: “The moment that struck me the most was at the very end, at the end of the third day, when we got the rankings and saw what we had lost, even if it wasn’t real money. It’s still pretty frustrating to see that you’ve lost so much money.” “I still felt a little stressed when I was making transactions, when I was buying or selling, because I was afraid of losing my money, even if it wasn’t real money.” (SSI). He also had trouble adapting to the bear market: “It’s true that the market was down. So I had a little trouble adapting.” (SSI) “I was already desperate that it could change positively all of a sudden.” (FG) “My emotions about the situation took over and encouraged me to stop doing anything. If there’s something you can do, do it. But it won’t be something that will change the situation much.” (FG) | A confirmation bias (code 1) drove him to look for signs of recovery on the charts: “I was trying to look at the charts all the time to see if there was a chance it would go back up, if there was a small dip and then it would go back up.” (SSI) “Basically, I was following companies that I knew a little bit about, but since others were telling me that these were companies that were making big profits, I thought, why not? If it can bring me the same thing as him, but I didn’t dare to put in the same amounts.” (FG) He also looked for social comfort (herd effect, code 2): “When I saw that I had lost quite a lot too, I told myself that it wasn’t just me and that others were also experiencing significant losses.” (SSI) He also tried to copy others (herd effect, code 2) “I took other people’s ideas and thought I could use them to get into the same situation as them, but I didn’t do it at the right time, and it had a negative impact on me.” (FG) | Impulsive decision-making (code 1) (about sales) His decisions were focused on selling to limit losses: “I was more interested in selling than buying.” (SSI) “I kept selling anyway, and I’m going to try to limit my losses.” and “I told myself that as I made gains, I would sell again.” (FG) “On the one hand, because I’ve taken a step back, I think it’s a bit like what you said yesterday, that it’s a bit screwed up and all, but hey, let’s go for it, we might as well take the risk.” (FG) |

| I.6. | A strong emotion of disappointment (code 1) was reported when moving from first to last place: “It was disappointing because… Actually, on the first day, I was in first place. So I was very happy and very motivated.” (SSI) and “And then I saw that I had dropped down anyway. It was disappointing. From first to last. Yes. That was the disappointment.” (SSI) He maintained optimism (code 2) despite the losses: “Up until then, you said to yourself, ‘Come on, I believe in it, I hope things will change.’ When there was a small gap, like 1% or 1.5%, I said to myself that with a lot of luck, it could work out, but at that point, I knew it wasn’t possible.” (SSI) “And so I said to myself that it’s true that you have to take risks, and so the desire to be first, let’s say, had an impact on decision-making.” (FG) | The anchoring bias (code 1) on initial performance (being first) made the downfall even harder to deal with: “At that point, I thought, ‘I shouldn’t have invested so much in companies that were… well, that were underperforming.’ So that was like a letdown. I was disappointed.” (SSI) | Disappointment was followed by decision paralysis (code 1) and resignation, with the student eventually “deleting” everything from his portfolio: “So it was just small gains and small losses. And that’s why, in the end, I realized it wasn’t working, so I deleted everything. I preferred to just leave it empty.” (SSI) “At the last minute, you say to yourself, ‘There’s no point anymore.’ Yes, at that point, I was actually 3% away from finishing, it wasn’t possible.” (SSI) |

| I.7. | The student expressed fear (code 1) of losing and intense stress: “A lot of stress. I felt a little stressed because if the share price went up, it was okay. If it went down, I felt a little stressed.” and “I was afraid of losing. Even though it was only virtual money, I was still afraid of losing it.” (SSI) “When you’re losing, you don’t want to sell, you don’t want to validate a loss.” (FG) “I tend to hold on to my position rather than take risks and sell and try something else.” (FG) | Even if biases were not noticeable, the absence of emotional regulation was noted: “No, I didn’t do anything to manage my stress. I don’t know how you can manage it in real life. But no, I didn’t do anything.” (SSI) “Emotions are not necessarily known. It wasn’t instantaneous. I didn’t even know to what degree. It was more or less precise.” (FG) | Fear prompted him to make impulsive decisions (code 1) (sales) to cut his losses, rather than wait for a rebound: “I was afraid of losing more. So I said to myself, ‘I’m just going to stop.’ So I think when it [the stock] started to fall, I sold it right away. Instead of waiting for it to go up again”. (SSI) |

| I.8. | The student quickly experienced fear (code 1a), which turned into frustration and a feeling of not being “good enough” compared to the other participants: “Right away, I quickly felt, how can I put it, that I wasn’t up to the task. I felt left behind compared to the others, because they had already participated in scholarship competitions or were trading on their own, so they were talking about things, but I thought to myself, we didn’t take the same classes, it’s not possible.” (SSI) “When I was winning, I knew very well that it was just pure luck.” (FG) His fear (code 1b) turned into abandonment and resignation: “Complete abandonment” and “In the end, I told myself it was a lost cause.” (SSI) | A strong loss aversion (code 1) caused him to hesitate about what decision to make: “I didn’t really know when to sell, whether to sell now or wait for the market to recover.” (FG). The participant then quickly cut his positions: “So I cut everything because I thought, no, this isn’t possible.” (SSI) “I decided to cut my losses at the end because I thought, after doing some research, that it was better to cut your losses than let them fall indefinitely.” (SSI). He noted that the feeling of loss is twice as strong as that of gain: “But I read that when you lose something, you suffer a loss, and the feeling you get is twice as strong as a gain. I think that’s what I took away from that book.” (SSI). This passage shows a search for information to understand the phenomenon of loss. | His frustration led to decision-making paralysis (code 1) facing a market he considered hopeless: “The market is still bearish, there’s no point in trying anything.” and “On the afternoon of the third day, yes. Because there comes a point when you say to yourself, the market is down, there’s no point in trying anything.” (SSI) |

References

- Abbink, K., & Rockenbach, B. (2006). Option pricing by students and professional traders: A behavioural investigation. Managerial and Decision Economics, 27(6), 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevy, J. E., Haigh, M. S., & List, J. (2022). Information Cascades: Evidence from an experiment with financial market professionals. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w12767/w12767.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Andraszewicz, S., Kaszás, D., Zeisberger, S., & Hölscher, C. (2023). The influence of upward social comparison on retail trading behaviour. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 22713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendassolli, P. F. (2013). Theory building in qualitative research: Reconsidering the problem of induction. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S. J., & Gagne, C. (2018). Anxiety, depression, and decision making: A computational perspective. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 41(1), 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. L., Imai, T., Vieider, F. M., & Camerer, C. F. (2024). Meta-analysis of empirical estimates of loss aversion. Journal of Economic Literature, 62(2), 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., He, F., & Lin, L. (2024). Anchoring effect, prospect value and stock return. International Review of Economics & Finance, 89, 1539–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S. L., & Rogut, N. (2024). Portfolio framing and diversification in a disposition effect experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 44, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmura, T., Le, H., & Nguyen, K. (2022). Herding with leading traders: Evidence from a laboratory social trading platform. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 203, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugosch, D., Horn, K., & Wang, M. (2023). New experimental evidence on the relationship between home bias, ambiguity aversion and familiarity heuristics. Journal of Economics and Business, 125, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z., & Neupane, S. (2024). Investor horizon, experience, and the disposition effect. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 44, 101003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchette, G. R. (2011). Laboratory experiments: Professionals versus students. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1939219 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Frydman, C., & Camerer, C. F. (2016). The psychology and neuroscience of financial decision making. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we There Yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Walden Faculty and Staff Publications. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/facpubs/455 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Gaar, E., Scherer, D., & Schiereck, D. (2022). The home bias and the local bias: A survey. Management Review Quarterly, 72(1), 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetti, E., & Giusberti, F. (2012). The effect of anger and anxiety traits on investment decisions. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(6), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, C. J., & Moutier, S. (2017). High but not low probability of gain elicits a positive feeling leading to the framing effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grupe, D. W., & Nitschke, J. B. (2013). Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016). The discrete emotions questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emotions. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0159915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G. W., & List, J. A. (2004). Field experiments. Journal of Economic Literature, 42(4), 1009–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, E. U., Shahzeb, F., Shaheen, M., Abbas, Q., Hameed, Z., & Hunjra, A. I. (2013). Impact of affect heuristic, fear and anger on the decision making of individual investor: A conceptual study. World Applied Sciences Journal, 23(4), 510–514. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/92679200/11-libre.pdf?1666155977=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DImpact_of_Affect_Heuristic_Fear_and_Ange.pdf&Expires=1756722599&Signature=T9iVf4RNLw6iVdDVXUIieAuusBoGbfjn4Tl3G45exslLtrRr6KXYF4z8ljqWE5GzwGX4aG8sYr0-Kf2~af3X1dz36PfX7EDv3vRq6zNuxXHdMgmupK-Hs8-tvchUejknKHHduSy8SA~uLKD8Qt0cu2SDbQdC~LhcvXX2lh5JQBCOjgXippFY3n5n5KtePkMHFogx4DXykD0yMbrzCNJR~RhXpd-sbCvgIZvscb3JIRJupk4YQA9O~AkfTfZcy3pZrvvtgfQEZd4BnBAf49c8ObBFoksIMjHnBhAo-tOYFw~PMG1yToXQHJXybJF3Zkz0xfO1JXTRSxVmot3CVlRoCQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y. L., Chen, H. L., Huang, P. K., & Lin, W. Y. (2021). Does financial literacy mitigate gender differences in investment behavioral bias? Finance Research Letters, 41, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcherson, C. A., & Gross, J. J. (2011). The moral emotions: A social–functionalist account of anger, disgust, and contempt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inghelbrecht, K., & Tedde, M. (2024). Overconfidence, financial literacy and excessive trading. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 219, 152–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiky, A., Atahau, A. D. R., Mahastanti, L. A., & Supatmi, S. (2024). Framing effect and disposition effect: Investment decisions tools to understand bounded rationality. Review of Behavioral Finance, 16, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J., Markova, I., & Kalampalikis, N. (2004). Qu’est-ce que les focus groups? Bulletin de Psychologie, 57(3), 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konteos, G., Konstantinidis, A., & Spinthiropoulos, K. (2018). Representativeness and investment decision making. Journal of Business and Management, 20(2), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E., & Ayduk, O. (2011). Making meaning out of negative experiences by self-distancing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasfer, M., & Ye, X. (2024). Corporate insiders’ exploitation of investors’ anchoring bias at the 52-week high and low. Financial Review, 59(2), 391–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2006). Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger’s influence on cognition. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A. W., & Repin, D. V. (2002). The psychophysiology of real-time financial risk processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(3), 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A. W., Repin, D. V., & Steenbarger, B. N. (2005). Fear and greed in financial markets: A clinical study of day-traders. American Economic Review, 95(2), 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, R. (2009). Interviews: In-depth, semi-structured. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S. F., & Seligman, M. E. (2016). Learned helplessness at fifty: Insights from neuroscience. Psychological Review, 123(4), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D., & Wilson, M. (2023). Effects of multiple discrete emotions on risk-taking propensity. Current Psychology, 42(18), 15763–15772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (1994). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophic and practical guide. Falmer Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, P., Poensgen, C., & Wulf, T. (2021). How hot cognition can lead us astray: The effect of anger on strategic decision making. European Management Journal, 39(4), 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (Vol. 16). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouna, A., & Anis, J. (2015). A study on small investors’ sentiment, financial literacy and stock returns: Evidence for emerging market. International Journal of Accounting and Economics Studies, 3(1), 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G. (2022). Developing a codebook for qualitative data analysis: Insights from a study on learning transfer between university and the workplace. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 46(3), 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathy, M. (2024). Behavioral finance and stock market anomalies: Exploring psychological factors influencing investment decisions. Shanlax International Journal of Management, 11(S1), 191–197. Available online: https://storage.prod.researchhub.com/uploads/papers/2024/05/31/6438_odEUckg.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pak, O., & Mahmood, M. (2015). Impact of personality on risk tolerance and investment decisions: A study on potential investors of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Commerce and Management, 25(4), 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J. (2015). A model of regret, investor behavior, and market turbulence. Journal of Economic Theory, 160, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J., Berry, E. V., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D. W., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Rutterford, J., & Kodwani, D. G. (2018). Is the disposition effect related to investors’ reliance on System 1 and System 2 processes or their strategy of emotion regulation? Journal of Economic Psychology, 66, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, R., Asl, H. G., Rostami, M. R., Gholipour, A., & Gholipour, F. (2011). Behavioral finance: The explanation of investors’ personality and perceptual biases effects on financial decisions. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(5), 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., & Firoz, M. (2020). Behavioural finance-review and synthesis of behavioural biases. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(6), 1754–1762. [Google Scholar]

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1985). The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. (1972). Theories of bounded rationality. In C. B. McGuire, & R. Radner (Eds.), Decision and organization (pp. 161–176). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. (2012). Investor irrationality and self-defeating behavior: Insights from behavioral finance. The Journal of Global Business Management, 8(1), 116. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, B., & Duxbury, D. (2012). Decision-dependent emotions and behavioral anomalies. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 118(2), 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpsepp, T., & Vaarmets, T. (2019). The disposition effect, performance, stop loss orders and education. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 24, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. (2024). Behavioral finance: Loss aversion, market anomalies, and prospect theory in financial decision-making. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management, 28, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers, T., Klarner, P., & Huy, Q. N. (2020). Emotions, time, and strategy: The effects of happiness and sadness on strategic decision-making under time constraints. Long Range Planning, 53(5), 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utari, D., Wendy, W., Azazi, A., Giriati, G., & Irdhayanti, E. (2024). The influence of psychological factors on investment decision making. Journal of Management Science (JMAS), 7(1), 299–309. Available online: https://www.exsys.iocspublisher.org/index.php/JMAS/article/view/379 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Wang, H., Zhang, J., Wang, L., & Liu, S. (2014). Emotion and investment returns: Situation and personality as moderators in a stock market. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(4), 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2023). Behavioral biases in investment decision-making. Advances in Economics, Management and Political Sciences, 46, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Zhao, D., Wu, Y., Tang, P., Gu, R., & Luo, Y. J. (2018). Differentiating the influence of incidental anger and fear on risk decision-making. Physiology & Behavior, 184, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yechiam, E., & Zeif, D. (2025). Loss aversion is not robust: A re-meta-analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 107, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T. (2025). Confirmation bias and herding behavior across the housing markets. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).