1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of Thailand’s economy, accounting for more than 99% of all enterprises and employing over 70% of the workforce (

Leurcharusmee et al., 2022;

Tarapituxwong et al., 2023;

OSMEP, 2022). Their role is particularly vital in rural areas where community enterprises contribute to local livelihoods, promote self-reliance, and reduce regional inequality. Beyond generating income and jobs, these enterprises also act as channels for grassroots innovation and social cohesion. However, rural regions still face persistent poverty, with rates significantly higher than in urban areas (

World Bank, 2024). At the same time, SMEs encounter structural barriers, including limited access to credit, weak financial planning, and vulnerability to external shocks. These challenges highlight the need for SMEs to develop agile financial strategies, adopt digital and technological solutions, and embed sustainable practices into their operations to strengthen resilience and competitiveness in an increasingly uncertain environment (

Hidayat-ur-Rehman & Alsolamy, 2023).

To remain competitive and resilient, SMEs must rely not only on external support and market access but also on the internal competencies of their entrepreneurs. Among these, self-awareness—the ability to objectively recognize one’s strengths, weaknesses, and limitations—emerges as a critical foundation for effective leadership, strategic decision-making, and organizational adaptability (

Lans et al., 2010;

Myyryläinen, 2022). The Johari Window Model (

Luft & Ingham, 1961) illustrates how reducing blind spots through feedback and reflection improves decision-making and adaptability, enabling entrepreneurs to better align strategies with operational realities. At the organizational level, the Upper Echelons Theory (

Hambrick, 2007) highlights how cognitive abilities and self-awareness among top managers shape firm outcomes, particularly in SMEs where owners and managers are often the same individuals. High self-awareness enables them to identify biases, seek expert input, and foster collaborative decisions (

Navis & Ozbek, 2016). This strengthens organizational resilience, enhances long-term performance, and extends to financial awareness, as entrepreneurs who acknowledge their limitations in accounting and planning are more likely to improve their financial literacy and adopt effective practices (

Anggara & Djamaluddin, 2024).

In this study, the primary focus is on how self-awareness functions as a cognitive bridge linking entrepreneurial competencies, specifically business acumen, to the financial performance of community enterprises. Rather than being embedded within these domains, self-awareness supports entrepreneurs in effectively applying their skills by fostering reflective thinking and critical evaluation. Within the context of business acumen, self-aware entrepreneurs are better equipped to assess their decision-making patterns, recognize misjudgments in market perception, and align strategic goals with operational realities (

Ragas & Culp, 2021). This reflective capacity enhances opportunity recognition, risk management, and resource allocation—key drivers of competitive advantage, particularly in localized or community-based enterprises. Likewise, in the area of accounting proficiency, self-awareness enables entrepreneurs to acknowledge gaps in their financial knowledge and proactively seek improvement.

Drury (

2018) emphasized that accurate financial interpretation and reporting are vital to strategic business planning. Entrepreneurs who recognize their limitations are more likely to engage with financial tools, pursue literacy training, or consult experts, thereby improving the quality and precision of their financial decision-making.

Although accounting proficiency is widely acknowledged as essential for sound business management, few studies have investigated how cognitive factors like self-business acumen awareness mediate its impact on financial performance, particularly in the context of community enterprises. This study addresses that gap by examining the mediating role of self-awareness in translating accounting proficiency into improved organizational outcomes. Focusing on SMEs in northern Thailand, the research situates itself within a region where such enterprises play a critical role in local economic development (

Nakhonsong & Chamruspanth, 2024). Despite their contribution to job creation and income generation, many of these enterprises face persistent challenges, including weak financial management systems and limited accounting knowledge (

Anggara & Djamaluddin, 2024). By highlighting the cognitive link between technical skills and business performance, this study provides empirical insights that can inform capacity-building policies aimed at enhancing financial literacy, managerial reflection, and strategic decision-making among community entrepreneurs.

In addition to its empirical contribution, this study employs a hybrid Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network (SEM–ANN) approach, combining theory-based analysis with advanced data-driven modeling techniques. While Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is widely used to test theoretical models and examine linear relationships among latent variables, it has limitations in capturing complex and nonlinear interactions (

Elnagar et al., 2021). To address this short-coming, ANN is applied as second-stage analysis. ANN is well suited for identifying hidden patterns, non-compensatory effects, and complex dependencies among variables that may not be visible through traditional statistical methods (

Al-Emran et al., 2021). By integrating ANN, this study improves the understanding of the factors that influence the financial performance of community enterprises.

This study makes several key contributions by developing a research model that examines how accounting proficiency influences the financial performance of community enterprises in northern Thailand, with self-business acumen awareness acting as a mediating cognitive factor. Unlike previous research that often treats accounting skills and business performance as directly linked or that relies solely on SEM, this study applies a hybrid SEM–ANN approach to capture both theoretical and predictive insights. SEM is used to test the mediation framework and assess linear relationships, while ANN captures complex, nonlinear interactions and enhances model accuracy. By integrating these methods, the study provides a more understanding of how technical skills (accounting proficiency) are internalized and applied through reflective business awareness, shaping financial outcomes in community-based SMEs.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature,

Section 3 delineates the data utilized in this investigation,

Section 4 elucidates the methodological approach employed,

Section 5 presents and analyzes the empirical findings, and

Section 6 offers concluding remarks and implications of the research.

2. Review Literature

2.1. Theoretical Framework

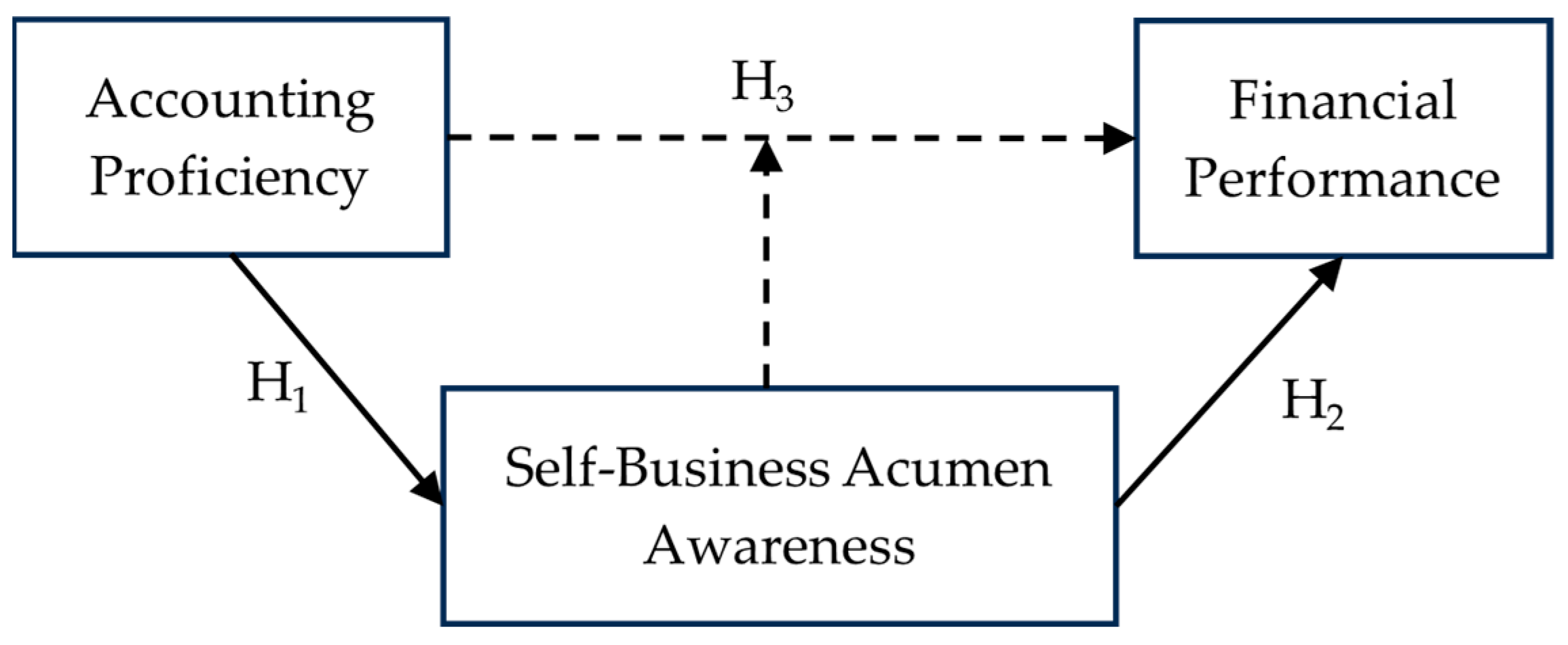

The framework integrates metacognition theory and the resource-based view (RBV) to explain how accounting proficiency and self-awareness interact to influence financial performance.

Metacognition theory posits that individuals improve decision-making by monitoring and reflecting upon their own cognitive processes (

Haynie et al., 2010). Applied to entrepreneurship, accounting proficiency equips entrepreneurs with technical knowledge that stimulates self-reflection and recognition of limitations, thereby enhancing self-business acumen awareness (H

1).

From the perspective of the RBV, accounting proficiency constitutes a valuable and rare intangible resource that can improve financial outcomes when effectively deployed (

Barney, 1991;

Madhani, 2010). However, its impact on performance is not automatic. The effectiveness of accounting proficiency depends on whether entrepreneurs are able to assess and apply their competencies accurately. This makes self-awareness a critical cognitive asset: it enables entrepreneurs to calibrate decisions, align competencies with organizational goals, and transform technical proficiency into meaningful business outcomes. Hence, higher levels of self-awareness are expected to contribute positively to financial performance (H

2). More importantly, self-awareness is conceptualized as a mediator through which accounting proficiency translates into improved performance (H

3).

In summary, this theoretical framework positions self-awareness as a context-sensitive bridge between technical skills and business outcomes. The conceptual model (

Figure 1) illustrates the hypothesized direct and indirect relationships to be tested in this study.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Self-Awareness and Business Performance

Recent research highlights the increasing importance of entrepreneurial self-awareness in enhancing business decision-making and adaptability. However, relatively few studies have explored how self-awareness functions as a mediating cognitive mechanism between technical competencies and business performance—particularly in the context of community enterprises. This study addresses that gap by focusing on self-business acumen awareness as the entrepreneur’s ability to accurately assess and reflect on their business understanding and decision-making, particularly in areas related to accounting and financial management. Despite its growing theoretical relevance, the empirical evidence regarding the role of self-awareness in business performance remains mixed, necessitating a more systematic investigation of its direct, indirect, and mediating effects.

2.2.1. Accounting Proficiency and Self-Awareness

Entrepreneurs with strong accounting skills are better equipped to evaluate their financial decision-making and identify areas requiring improvement. Prior studies highlight that accurate self-reflection on accounting knowledge motivates entrepreneurs to pursue further training, consult experts, or adjust financial practices (

Aránega et al., 2020;

Shepherd & Patzelt, 2017). This process aligns with metacognition theory, whereby individuals enhance future decision-making through self-assessment. Accordingly, accounting proficiency is expected to enhance self-awareness among entrepreneurs. Taken together, these studies indicate that accounting proficiency enhances entrepreneurs’ capacity for accurate self-reflection and metacognitive assessment. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Accounting proficiency positively influences self-business acumen awareness among community entrepreneurs.

2.2.2. Direct Effect of Self-Awareness on Financial Performance

Despite substantial evidence supporting the role of self-awareness in entrepreneurial success, some studies indicate that its direct impact on business performance remains inconclusive. While financial self-efficacy is generally associated with positive business outcomes, its precise influence on profitability, business growth, and entrepreneurial satisfaction remains underexplored, highlighting the need for further research (

Veselinovic et al., 2022). Moreover, self-awareness alone does not always translate into improved performance, particularly when external constraints such as market limitations, financial restrictions, or regulatory burdens prevent entrepreneurs from effectively leveraging their self-assessed competencies. Additionally, cultural factors play a critical role in shaping entrepreneurial self-perception, as varying socio-economic contexts place different levels of emphasis on specific business competencies, which can influence how entrepreneurs evaluate their abilities and make strategic decisions (

Caliendo et al., 2023). In some cultures, individuals may be socialized to either underestimate or over-state their competencies, leading to distortions in self-assessment that affect business decision-making and long-term performance outcomes. These findings suggest that the relationship between entrepreneurial self-awareness and business performance is not universally linear but rather contingent on broader socio-cultural and economic conditions, necessitating further empirical investigation to understand its nuanced effects across diverse entrepreneurial ecosystems. Although findings on the direct effect of self-awareness remain inconclusive, theory and evidence suggest that accurate self-perception generally strengthens entrepreneurs’ decision-making and performance. Therefore, the following hypothesis is advanced:

H2. Self-business acumen awareness positively influences financial performance among community entrepreneurs.

2.2.3. Mediating Role of Self-Awareness Between Accounting Proficiency and Financial Performance

Accounting proficiency constitutes a fundamental capability underpinning small business success. Entrepreneurs with stronger financial management skills tend to allocate resources more effectively, maintain operational discipline, and mitigate risks associated with poor cash flow or mismanagement. Prior research consistently demonstrates that accounting competence contributes to profitability, growth, and long-term survival, particularly among enterprises with limited access to external financial expertise (

Dahmen & Rodríguez, 2014). While financial self-efficacy and financial literacy have also been widely linked to SME performance (

Veselinovic et al., 2022;

Abdallah et al., 2024), this study emphasizes self-awareness as a distinct construct—focused not merely on financial knowledge or confidence, but on the entrepreneur’s ability to evaluate and calibrate their own cognitive and practical limitations. In community enterprises, where accounting systems are often rudimentary, proficiency in financial management alone may not be sufficient to secure sustainable outcomes unless supported by accurate self-awareness.

Cognitive biases can further complicate this relationship. Entrepreneurs with limited expertise may overestimate their competence (Dunning–Kruger effect), leading to poor financial planning, misallocated resources, and reluctance to seek professional advice (

Navis & Ozbek, 2016;

Dahmen & Rodríguez, 2014). Conversely, entrepreneurs who underestimate their competencies—particularly observed among female entrepreneurs—may avoid risk-taking and limit strategic initiatives, despite having adequate or even superior skills (

Brieger et al., 2021). This form of self-underappraisal can also reduce the impact of accounting proficiency on performance by discouraging confidence in financial decision-making. These dynamics highlight the dual-edged nature of entrepreneurial self-awareness: when accurate, it enables entrepreneurs to leverage their accounting skills more effectively; when distorted, it impairs judgment and dampens the potential benefits of technical proficiency.

Importantly, while entrepreneurial self-awareness may not directly enhance financial performance, it plays a critical role by enabling entrepreneurs to more effectively translate their accounting proficiency into sound financial decisions and strategic behavior. This framing supports a more nuanced understanding of the entrepreneur’s internal decision-making process, where self-awareness serves as a cognitive bridge between technical skill (accounting) and financial outcomes. In the context of Thai community enterprises, many of which face limited resources and financial knowledge (

Anggara & Djamaluddin, 2024), enhancing self-awareness may help entrepreneurs leverage their existing accounting skills more effectively, indirectly contributing to improved business sustainability and growth. Collectively, the literature points to self-awareness as a cognitive bridge that channels technical skills into performance outcomes. Based on this reasoning, we hypothesize the following mediating relationship:

H3. Self-business acumen awareness positively mediates the relationship between accounting proficiency and financial performance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Description

This study draws on a sample of 210 Thai community enterprises, evenly distributed across eight provinces in the upper northern region of Thailand. Data was collected during the second quarter of 2024 through a structured questionnaire administered to enterprise owners or managers.

To evaluate the financial performance of these enterprises, the study initially considered multiple dimensions, such as balance sheet composition, Cash Flow from Operating Activities (CFO), Return on Equity (ROE), and Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratios. However, due to the limited availability of formal financial records among community enterprises, the study employs more accessible proxies. Specifically, two cross-sectional indicators, minimum monthly revenue and percentage of monthly business profit, were used to represent financial performance. These indicators were derived directly from entrepreneurs’ self-reported responses in the survey and serve as practical measures suitable for the context.

The research design incorporates a multidimensional survey instrument structured around five core domains: Financial performance proxies, fundamental business characteristics, entrepreneurial traits, accounting proficiency, and self-business acumen awareness. These variables function within the study’s structural model, where accounting proficiency serves as the primary independent variable, financial performance as the outcome, and self-business acumen awareness as a mediating factor. Additional controls include key business characteristics and entrepreneurial background traits.

The self-business acumen awareness construct captures this reflective capacity, serving as a cognitive mechanism that mediates the effect of technical skills on financial outcomes. Each category includes at least five sub-dimensions, providing a comprehensive understanding of the micro-foundations of business performance in Thai community enterprises. This structure allows the study to investigate not only the direct effects of accounting proficiency and business fundamentals on performance, but also the indirect pathways shaped by self-awareness.

Table 1 provides a detailed explication of each component, elucidating their respective roles in the investigative process.

In

Table 1, a comprehensive delineation of the study’s variables is presented. Continuous variables are expressed as means, while categorical variables are represented as percentages. Analysis of the data reveals that firms in the study demonstrated an average minimum monthly revenue of 19,824.70 Baht, coupled with a mean profit percentage of 15.43%.

With respect to fundamental business factors, the landscape of community enterprise establishments exhibits notable diversity. Manufacturing enterprises dominate the sample, comprising 56.21% of surveyed firms. In contrast, the service sector represents the smallest portion, accounting for a mere 18.05% of the sample. The study’s examination of business registration types yields interesting insights: 42.25% of firms reported commercial business registration, whereas only 6.35% were registered as juristic persons.

On average, the surveyed businesses have been operational for 8.73 years since their establishment. Financial indicators paint a picture of the firms’ fiscal health: the mean business debt stands at 6476.19 Baht, while average current assets amount to 113,326.19 Baht.

Examining entrepreneurs’ characteristics reveals significant demographic and educational trends. Notably, females constitute more than two-thirds of the sample, indicating a strong presence of women in entrepreneurship within the studied context. The mean age of entrepreneurs is 43.09 years, suggesting a mid-career demographic. Educational attainment among the entrepreneurs is predominantly high, with 63.81% holding bachelor’s degrees and 5.24% having completed postgraduate studies. Regarding technological proficiency, entrepreneurs self-assessed their technology and innovation adoption level at an average of 3.43 on a 5-point scale, indicating a moderate to high level of technological engagement. Professional development patterns vary considerably: while 31.42% of entrepreneurs participate in training sessions once or twice annually, a substantial 40.00% report no participation in any training sessions.

Regarding accounting skills and knowledge factors, the study employed 10 measurement components, as detailed in

Table 1. Notably, all components scored an average of more than 3.85 points on a 5-point scale, indicating generally high levels of accounting competency among entrepreneurs. Within the awareness factor, entrepreneurs’ self-assessment of business acumen revealed interesting disparities. The highest average score of 4.35 was achieved in organizational culture, reflecting strong confidence in this area. Conversely, organizational improvement and strategic planning received the lowest average score of 3.80, suggesting potential areas for skill development among the entrepreneurial cohort.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

In this study, we investigate the awareness factors that exert influence on the financial performance of community enterprises in northern Thailand, employing Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as the analytical tool. SEM has garnered widespread adoption due to its capacity to simultaneously analyze multiple variables and elucidate both direct and indirect effects within complex relational frameworks (

Memon et al., 2021). The conceptual framework is illustrated in

Figure 1. The analysis is conducted in two stages. This study employs a cross-sectional research design, utilizing primary data collected from community enterprises in northern Thailand in 2024. The initial phase scrutinizes variables that potentially influence entrepreneurs’ self-awareness of business acumen. These variables include observed variables comprising fundamental business elements and entrepreneurial characteristics, and accounting proficiency and knowledge, which are conceptualized as latent constructs. This latent construct is measured using ten indicators, as shown in

Table 1. In this context, self-awareness of business acumen acts as the dependent variable and is defined as a latent variable operationalized across five distinct dimensions: strategy, organization, information, process, and culture. The variables from the initial phase are mathematically represented in Equation (1). The subsequent phase evaluates the consequential effect of self-awareness of business acumen on the financial performance of the enterprise, as Equation (2).

In Equation (1), entrepreneurs’ self-awareness of business acumen (

) specified as a latent dependent variable. The independent variables (

) include fundamental business factors, such as the type of business (

), registration (

), business age (

), business debt (

), and current assets (

). In addition, entrepreneurial characteristics, encompassing gender (

), age (

), education level (

), and the degree of technology and innovation implementation (

), are incorporated. Further, factors related to accounting knowledge development training (

), as well as accounting skills and knowledge (

), are also treated as independent variables. The omitted category within each factor serves as the baseline variable. The latent construct accounting knowledge and skills (

) was operationalized using ten self-assessment items (KL1 to KL10), and are modeled as reflective indicators, as they are manifestations of underlying accounting competency. In Equation (2), the financial performance of the enterprise (

) is indicated as the dependent variable, while self-awareness of business acumen is identified as the independent variable. Furthermore, in both Equations (1) and (2), the latent construct awareness of business acumen (

) was measured using five conceptual dimensions according to

Table 1. These five dimensions are also treated as reflective indicators, as they are assumed to reflect an underlying unidimensional awareness construct. The parameters

denote the intercept term or the baseline level, while

represent the path coefficients in the structural model, indicating the strength and direction of the relationships between the latent or observed predictors and their outcomes, the coefficient

captures the effect of entrepreneurs’ self-awareness of business acumen on financial performance in Equation (2). Here,

denotes the observational unit, representing each individual community enterprise.

indexes each of the

independent variables included in the model to explain variations in entrepreneurs’ self-awareness of business acumen. The terms

represent the disturbance term or residual variance.

3.2.2. Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

The initial step involves performing SEM to validate the structural relationships between latent constructs. SEM is used to test the linear relationships based on the hypothesized model. Upon achieving a satisfactory model fit, latent variable scores are generated. These scores, derived from observed variables, serve as proxies for the underlying constructs identified through SEM analysis. Subsequently, the latent variable scores extracted from the SEM analysis are utilized as input data for training the ANN model. In this context, two-step ANNs are employed to corroborate the robustness of the SEM results by evaluating their predictive capacity and performance metrics between SEM and ANN methodologies.

Once the latent variable scores have been extracted from the SEM model, they are utilized as input data for training the ANN model to predict entrepreneurs’ awareness and financial performance of community enterprises.

Step 1: ANN Architecture for Awareness Prediction

Input Layer: The latent and significant independent variable from SEM are fed into the input layer of the ANN. These scores serve as the independent variables (inputs) that ANN will use to predict the target variable ()

Hidden Layers: The ANN model includes one or more hidden layers, where neurons process the

-th input (

) to the hidden layer by applying weights (

), biases (

), and activation functions (

). Here

represents the weight associated with the

-th hidden node for a specific input,

denotes the bias term associated with the

-th hidden node, and superscript

indicates the path between input and hidden layer. This process captures both linear and nonlinear interactions among the variables, allowing ANN to potentially discover complex relationships that SEM might overlook. The output of each neuron (

) in the hidden layers is calculated as Equation (3):

where

is activation function as assumed to be sigmoid function.

Output Layer: The output layer of the ANN model provides the predicted values

as follows:

where

represents the predicted values of entrepreneurs’ self-awareness of business acumen,

is the output of each neuron from hidden layer as shown in Equation (3).

denotes the weight associated with the

-th output node for a specific input,

is the bias term associated with the

-th output node, and superscript

indicates the path between hidden layer and output layer.

In the second step, the predicted

Awareness score from Step 1 is used as the input to predict the financial performance (

) of the community enterprises. The financial performance prediction is formulated as

Then, the ANN model is trained using the backpropagation algorithm, which adjusts the weights and biases to minimize the error between predicted values

and actual outcomes

. The loss function used to measure this error is the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), which is the square root of MSE, is calculated as Equation (6):

The iterative training process of the ANN model employs gradient descent to minimize the RMSE through the systematic adjustment of network weights and biases across the dataset. Upon completion of the ANN model training, a comparative analysis of its performance and the SEM model is conducted, utilizing RMSE as the primary metric for assessing predictive accuracy.

The comparison of RMSE values between the SEM and ANN models facilitates an evaluation of the SEM structure’s robustness. A substantial reduction in RMSE within the ANN model would indicate the presence of significant nonlinear relationships that the SEM framework is unable to capture, suggesting that these nonlinear patterns are crucial for enhancing predictive accuracy. Conversely, comparable RMSE values between the two models would imply that the SEM model provides a robust representation of the inter-relationships among latent variables, with no substantial nonlinear patterns unaccounted for.

3.2.3. SEM–ANN-Based Approach

The SEM–ANN-based approach integrates SEM and ANN, providing a robust framework for modeling complex systems across various disciplines. This methodology combines SEM’s theoretical rigor with ANN’s nonlinear modeling capabilities, enhancing predictive power and interpretability. While traditional SEM has been limited to single-stage linear data analysis (

Elnagar et al., 2021), the incorporation of ANN as a second-stage analysis addresses this constraint (

Al-Emran et al., 2021). Recent advancements have seen a shift from shallow ANN (single hidden layer) to deep ANN (multiple hidden layers), further improving effectiveness and accuracy in capturing complex relationships (

Ahmed et al., 2023). This evolution towards a hybrid SEM–ANN procedure based on deep learning represents a significant methodological advancement. Despite challenges such as increased computational complexity and interpretation difficulties, the SEM–ANN approach continues to gain traction, offering researchers a sophisticated tool to bridge theoretical constructs with data-driven insights in fields ranging from business and psychology to environmental sciences and healthcare.

The hybrid SEM–ANN framework has gained growing popularity in the recent business and finance research due to its ability to enhance predictive accuracy and offer deeper insights into variable relationships (

Ahmed et al., 2023;

Hidayat-ur-Rehman & Alsolamy, 2023;

Soomro et al., 2025).

Albahri et al. (

2022) highlights the increasing importance of hybrid methodologies that integrate Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) across a range of disciplines, particularly in applications involving topical treatments. While SEM is effective in identifying relationships among latent constructs, including independent, mediating, moderating, control, and dependent variables, it remains limited in its ability to capture non-compensatory relationships. To address this limitation, a dual-stage SEM–ANN analysis has been proposed, enabling the examination of both linear and non-compensatory relationships among constructs.

Hidayat-ur-Rehman and Alsolamy (

2023) employed the Structural Equation Modeling–Artificial Neural Network (SEM–ANN) approach to validate their proposed model, which examines the interrelationships and dynamics within small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Their study specifically investigates the interplay between FinTech adoption, competitiveness, circular economic practices, transformational leadership, and sustainable performance. The findings highlight the intricate linkages between technological adoption, leadership, and sustainability practices, underscoring their collective role in enhancing SMEs’ overall performance. Recently,

Soomro et al. (

2025) used SEM–ANN to analyze key drivers of AI adoption, including top management support, employee capability, customer pressure, complexity, vendor support, and relative advantage.

3.3. Measurement Model Validity

3.3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is a statistical technique employed to uncover the underlying structure of a dataset by identifying relationships between observed variables and latent constructs (

Fabrigar & Wegener, 2012). It is widely used for theory development, psychometric validation, and data dimensionality reduction (

Costello & Osborne, 2019). EFA serves three primary functions: detecting patterns in data, establishing relationships among variables, and refining factor structures. The appropriateness of data for factor analysis is assessed through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (acceptable at KMO ≥ 0.70) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Factors are extracted based on eigenvalues, with scree plots aiding in determining the optimal number of factors. Factor loadings, which quantify the strength of associations between observed variables and latent constructs, provide the basis for interpretation, with values exceeding 0.30 considered meaningful (

Raut et al., 2018;

Hair et al., 2010). To enhance interpretability, factor rotation techniques such as orthogonal rotation (e.g., varimax) and oblique rotation (e.g., promax) are applied to optimize the alignment of factors within a multidimensional space. EFA operates under key assumptions, including sufficient sample size, normality, linearity, and factorability of data. Given its capacity to reveal latent structures and explain observed correlations, EFA is a fundamental tool in empirical research for validating theoretical models and refining measurement instruments (

Husain & Aziz, 2022)

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was employed to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model prior to structural testing. Following the recommendations of

Gerbing and Anderson (

1988), the evaluation of construct validity comprised tests of unidimensionality, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE) were computed to evaluate the internal consistency and convergent validity of the latent constructs (

Benton et al., 2020). A CR value greater than 0.70 indicates adequate reliability, while an AVE above 0.50 suggests that the construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicators (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981). According to this approach, the square root of the AVE for each construct is compared with its correlations with other constructs. Discriminant validity is established when the square root of a construct’s AVE exceeds its highest correlation with any other construct, indicating that the construct shares greater variance with its own measures than with measures of other constructs (

Hair, 2014). This procedure is widely used in financial and management research as a robust test to confirm that latent variables are conceptually distinct.

4. Analysis of the Results

4.1. Results of EFA and Measurement Model

According to our analysis of the measurement and Structural Equation Model presented in

Figure 2, two key latent variables require Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to assess their underlying structure. First, the accounting skills and knowledge (

) construct was directly measured using ten items, labeled KL1 to KL10 (refer to

Figure 2). Each item was assessed using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The construct, consisting of these ten items, was subjected to Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to assess its underlying structure. The results indicated that Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (

(45) = 3250.936,

< 0.001), confirming that the data was suitable for factor analysis. Additionally, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was found to be 0.730, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.6 (

Husain & Aziz, 2022). These results validate the appropriateness of the dataset for further factor analysis.

The latent construct accounting skills and knowledge was operationalized using ten perception-based indicators adapted from

Putsom (

2021), who validated the scale among Thai dairy farm entrepreneurs. These indicators reflect self-perceived competency and are conceptually aligned with the dimension of self-awareness. This operationalization ensures both theoretical relevance and contextual appropriateness for capturing accounting awareness among community enterprise entrepreneurs. To empirically validate this construct, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed. The determination of the number of factors to be extracted was based on the eigenvalues and the percentage of variance explained. In accordance with the Kaiser criterion, only factors with eigenvalues equal to or greater than one were considered significant, and a minimum cumulative variance of 60% was deemed satisfactory (

Hair et al., 2010). As presented in

Table 2, a single factor was extracted with an eigenvalue of 6.84, accounting for 68.46% of the total variance. Furthermore, the construct was effectively represented by ten items, with factor loadings as follows: KL8 (0.915), KL4 (0.908), KL6 (0.862), KL5 (0.825), KL3 (0.823), KL2 (0.813), KL1 (0.819), KL10 (0.771), KL9 (0.766), and KL7 (0.755). All variables exhibited sufficiently high loadings (>0.70), with KL7 having the lowest and KL8 the highest. These findings indicate that the construct is unidimensional and statistically robust, justifying its use as a latent variable in the structural model.

Second, the awareness factor was evaluated using five key dimensions: strategy (

Rivera, 2015), organization (

Rivera, 2015), information (

Gandini et al., 2024), process (

Gandini et al., 2024), and culture (

Showry & Manasa, 2014) (refer to

Figure 2). Each dimension utilized a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The results confirmed that the dataset met the necessary assumptions for factor analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a statistically significant result (

(10) = 953.370,

< 0.001), indicating that the correlation matrix was sufficiently different from an identity matrix. Furthermore, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.814, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.6. These findings suggest that the dataset was well suited for factor extraction and subsequent analysis.

As shown in

Table 3, the EFA identified a single underlying factor with an eigenvalue of 3.75, explaining 75.09% of the total variance. This result suggests that a single component effectively captures the variance within the awareness construct. Further examination of the factor loadings reveals that the construct is well represented by five items, each demonstrating a sufficiently high loading (>0.6). The highest loading was observed for method (0.952), followed by strategy (0.926), organization (0.884), information (0.862), and culture (0.617), with culture exhibiting the lowest but still acceptable factor loading. These results confirm the unidimensionality of the construct and reinforce the reliability of the factor structure, supporting its appropriateness for further analysis.

4.2. Convergent, Discriminant Validity, and Nonlinearity Test

Before proceeding with the structural model, the measurement model was evaluated through CFA to ensure that the constructs satisfy the required standards of reliability and validity.

Table 4 presents the results of the confirmatory factor analysis for financial performance (

), awareness (

), and accounting skills and knowledge (

). The composite reliability (CR) values are 0.922 for awareness, 0.949 for

, and 0.710 for

, all of which exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70 (

Nunnally, 1978), thereby confirming internal consistency reliability. Similarly, the average variance extracted (AVE) values of 0.708, 0.639, and 0.561, respectively, are greater than the minimum acceptable level of 0.50 (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981), supporting convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion. The square roots of AVE, reported on the diagonal of

Table 4, are 0.842 for

, 0.799 for

, and 0.749 for

. These values are all greater than their corresponding inter-construct correlations (ranging from −0.088 to 0.105), indicating that each construct shares more variance with its own measures than with other constructs. Therefore, discriminant validity is adequately established for the measurement model (

Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

To test the validity of our hypothesis regarding the nonlinear structure between the variables of interest, we employed the Ramsey RESET test (

Maneejuk et al., 2024). The results, presented in

Table 5, provide evidence of nonlinearity in both the financial performance–awareness nexus and the awareness–accounting knowledge nexus. These findings suggest that linear regression models may be inadequate for fully capturing the underlying relationships. Consequently, the adoption of the SEM–ANN approach is justified, as it better accommodates nonlinear patterns and improves explanatory accuracy.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling Results

Prior to interpreting the structural relationships, a full residual diagnostic was conducted to assess the adequacy of the model specification. The standardized residuals indicated no substantial sources of misspecification, with the mean raw residuals of observed variables approximating zero, suggesting a good overall fit between observed and model-predicted values. Overall model fit statistics further confirmed that the model provides an acceptable to good fit. The chi-squared statistic was χ

2(341) = 971, yielding a χ

2/df ratio of 2.85, within the acceptable range of less than 3 (

Kline, 2023). The RMSEA was 0.089, slightly above the ideal 0.08 cutoff, but still within a tolerable range (

MacCallum et al., 1996). Additional fit indices supported this conclusion: SRMR = 0.078, CFI = 0.918, and TLI = 0.905, all meeting or exceeding conventional benchmarks for adequate model fit (

Hu & Bentler, 1999). Moreover, the Coefficient of Determination (CD) was 0.961, indicating that the model explains 96.1% of the variance in the observed variables. Collectively, these results validate the adequacy of the model and support the subsequent interpretation of its structural pathways.

In

Table 6, we present the coefficients estimated from the Structural Equation Model. Within the domain of fundamental business factors, this study examines the relationship between business type and self-awareness. The analysis reveals that businesses operating in the commercial sector demonstrate a statistically significant positive association with self-awareness (

= 0.359). This finding suggests a robust correlation between commercial sector operations and enhanced levels of self-awareness in business acumen. Comparatively, enterprises in the commercial sector exhibit higher degrees of self-awareness in business acumen than their counterparts in the service sector. This finding aligns with existing literature suggesting that the competitive nature of commercial environments foster greater self-awareness (

Hägg & Jones, 2021).

Further analysis of business registration types reveals noteworthy findings. Enterprises registered as commercial businesses and juristic persons exhibit negative coefficients of −0.436 and −0.776, respectively, in relation to self-awareness in business acumen. These results suggest that community enterprises falling into these registration categories demonstrate lower levels of self-awareness in business acumen compared to their counterparts with no formal registration. The inverse relationship between formal business structures and self-awareness in business acumen stems from two main factors. Unregistered businesses often develop keener self-awareness as a survival mechanism in less formal environments (

Fuentelsaz et al., 2019). Conversely, formalized structures may breed complacency, reducing the perceived need for ongoing self-evaluation.

Furthermore, the analysis revealed a statistically significant negative association between current assets and self-awareness in business acumen, as evidenced by a coefficient of −0.110. This inverse relationship suggests that as a firm’s current assets increase, there is a corresponding decrease in the levels of self-awareness pertaining to business acumen. These imply that elevated levels of liquid assets may engender a heightened sense of financial stability, which inadvertently attenuates the perceived imperative for rigorous self-evaluation and market vigilance (

Thurmond, 2019).

The analysis highlights that entrepreneurs who attend 3–5 training sessions annually significantly improve their self-awareness in business acumen, with a coefficient of 0.330, supporting the role of continuous professional development in enhancing business skills. Additionally, the study finds a positive relationship between accounting skills and business acumen, as indicated by a 0.125 coefficient, emphasizing the importance of financial literacy in better understanding business decisions (

Eniola & Entebang, 2017).

Unfortunately, the relationship between self-awareness in business acumen and a firm’s financial performance appears to be tenuous. Current research suggests that heightened self-awareness among business leaders does not significantly correlate with improved financial outcomes for their organizations. This result aligns with the research of

Bratton et al. (

2011), which emphasizes that while self-awareness contributes to personal and professional growth, it does not necessarily translate into positive organizational outcomes or enhanced financial performance.

While the direct link between self-awareness and financial performance is weak, the mediating role of awareness also appears limited. The indirect pathway, derived from the product of accounting knowledge’s effect on awareness (

β = 0.125,

p < 0.1) and awareness’s effect on performance (

β = −0.038,

p > 0.1), results in a negligible coefficient (

β = −0.005). This outcome indicates that self-awareness does not significantly mediate the proficiency–performance relationship in this study. Instead, awareness appears to function more as a cognitive enabler that enhances the effective use of technical skills under certain conditions rather than as a decisive mechanism linking accounting proficiency to financial outcomes (

Veselinovic et al., 2022).

4.4. Artificial Neural Network Results

To assess model robustness, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) study was conducted, focusing exclusively on the critical predictors identified by the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) findings. The ANN analysis incorporated six input neurons corresponding to key variables: business in the commercial sector, commercial business, juristic person, current assets, accounting training, and accounting skills. The model featured a single output neuron (

Awareness) and employed a two-hidden-layer deep ANN architecture to facilitate more profound learning at each neuron node. Both hidden and output neurons utilized the sigmoid function as the activation function. To optimize model performance, input and output neuron values were normalized to the range [0, 1]. Then, the predicted awareness is fed as the input to predict the financial performance (

F_perf). The ANN model architecture is depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The study implemented a ten-fold cross-validation technique, with an 80:20 ratio for training and testing data, respectively, to mitigate overfitting in the ANN model. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) is selected as the performance metric.

To determine the optimal number of nodes in each layer, this study initially employs the Halfway Rule, which estimates the appropriate number of nodes per layer. Based on this principle, the first ANN structure, comprising six input neurons (

Acc_know, commer, com_bus, juris, cur_ass, semi3_5) and one output neuron (

Awareness), yields an estimated optimal hidden layer size of four nodes. Similarly, for the second ANN structure, where one input neuron (

Awareness) maps to one output neuron (

F_Perf), the optimal number of nodes per hidden layer is estimated at one node. To further refine the ANN architecture and ensure the most effective configuration, this study employs a grid search approach with neurons ranging from 1 to 6, systematically evaluating various neuron allocations and selecting the structure that minimizes the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The results of this optimization process are presented in

Table 7.

To further evaluate the predictive validity of the proposed framework, this study compared the performance of alternative ANN structures against a benchmark model (

Table 7) and the SEM baseline. The benchmark model was constructed by selecting the best-fitting hidden layer structure for each ANN configuration, while constraining both hidden and output neurons to use the identity (linear) activation function. This design ensures that any performance improvement observed in ANN models can be attributed to their capacity to capture nonlinear patterns beyond linear specifications. The results yielded RMSE values of 0.2063 and 0.2162 for the ANN model’s training and testing phases, respectively. When compared with the SEM’s RMSE of 0.1226, the higher ANN values suggest that SEM provides a more robust representation of the interrelationships among latent variables. This comparison indicates the absence of significant nonlinear patterns unaccounted for in SEM, thereby affirming its robustness. Moreover, the findings imply that although ANN models can outperform purely linear benchmark networks, the lack of additional nonlinear patterns beyond those already captured by SEM confirms the adequacy of the SEM framework in this empirical context.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine the role of self-business acumen awareness in shaping financial performance among community enterprises in northern Thailand, focusing on how technical and cognitive factors interact in resource-constrained entrepreneurial contexts. The results provide new evidence that accounting proficiency does not operate in isolation; rather, its influence on financial outcomes is conditioned by entrepreneurs’ capacity for self-awareness.

The analysis demonstrates a positive association between accounting proficiency and self-business acumen awareness. This supports metacognition theory (

Haynie et al., 2010), which suggests that individuals with greater technical competence are more capable of reflecting on their cognitive processes and assessing the adequacy of their knowledge. Entrepreneurs with stronger accounting skills are therefore better positioned to recognize gaps in decision-making and to take corrective action through training, consultation, or practice adjustments. This finding is consistent with prior studies linking financial literacy and technical competence with enhanced reflective capacity and adaptive behavior (

Aránega et al., 2020;

Shepherd & Patzelt, 2017). Unlike financial self-efficacy, which signals confidence, or financial literacy, which signals knowledge, self-awareness emerges as a distinct mechanism that enables critical evaluation of one’s own competence. In the Thai context, where accounting systems are often rudimentary and institutional support is limited, accounting proficiency appears to act as a catalyst for self-reflection and cognitive vigilance.

Empirical patterns within the data further illuminate this dynamic. Community enterprises operating in the commercial sector display significantly higher levels of self-business acumen awareness compared with those in the service sector. This suggests that competitive markets foster greater vigilance and self-reflection, as entrepreneurs must continually evaluate and adjust strategies to survive. Conversely, formally registered enterprises, whether as commercial registrations or juristic entities, exhibit lower levels of self-awareness than their unregistered counterparts. This result may reflect a “formalization paradox,” where legal structures provide a sense of security that dampens the perceived need for self-assessment. Informal firms, by contrast, appear to rely more heavily on self-awareness as a survival mechanism in environments with limited external protections. Similarly, financial stability shows a counterintuitive effect: enterprises with higher current assets tend to demonstrate lower self-awareness, implying that resource abundance may foster complacency or overconfidence, thereby discouraging critical self-evaluation. These findings point to the contextual contingencies of cognitive processes, where structural and financial conditions shape whether entrepreneurs engage in self-reflective practices.

At the individual level, participation in training programs emerges as a significant enabler of self-business acumen awareness. Beyond simply building technical skills, training appears to cultivate reflective thinking and awareness of personal limitations, strengthening entrepreneurs’ ability to align managerial choices with strategic goals. This underscores the importance of continuous learning and professional development not only for knowledge acquisition but also for nurturing the cognitive competencies required for adaptive decision-making.

The results also indicate that self-business acumen awareness contributes only modestly to financial performance. This aligns with the resource-based view (

Barney, 1991), which conceptualizes self-awareness as an intangible capability that can enhance decision calibration and strategic alignment. However, the weak and statistically insignificant effect suggests that awareness alone is insufficient to generate measurable financial outcomes. Structural barriers such as limited market access, capital constraints, and regulatory burdens may prevent entrepreneurs from converting self-awareness into tangible improvements in performance (

Caliendo et al., 2023). This finding echo prior research emphasizing that awareness should be regarded as a cognitive enabler rather than a standalone driver of performance (

Veselinovic et al., 2022). Its primary value appears to lie in amplifying the use of technical competencies, particularly accounting proficiency, by fostering better judgment, planning, and adaptive decision-making.

The mediation analysis further reveals that self-awareness does not significantly transmit the effect of accounting proficiency to financial performance. While accounting knowledge positively influences awareness, the subsequent path from awareness to performance is negative and statistically insignificant. The resulting indirect effect is minimal, indicating that self-awareness does not function as a strong mediating mechanism in this context. Instead, awareness appears to play a complementary role by supporting the more effective application of technical skills under certain conditions, rather than serving as a decisive link between proficiency and outcomes. This helps explain why entrepreneurs with comparable accounting knowledge may still achieve divergent financial results, as awareness supports reflective practice but does not consistently transform technical proficiency into superior performance (

Brieger et al., 2021;

Abdallah et al., 2024).

In the specific context of Thai community enterprises, these insights hold substantial practical relevance. Capacity-building initiatives that focus solely on technical training are unlikely to achieve lasting impact if entrepreneurs lack the cognitive ability to assess and adapt their behavior. Interventions that combine accounting proficiency development with reflective practices such as peer learning, coaching, or structured self-assessment are likely to be more effective in cultivating both technical and cognitive assets. At the same time, the findings suggest that excessive self-awareness may also have unintended consequences. In the Thai context, where community entrepreneurs often operate under conditions of financial precarity, regulatory uncertainty, and high competition, heightened awareness can generate stress, anxiety, or decision paralysis. Such pressures may hinder the effective translation of accounting knowledge into performance, as entrepreneurs become overburdened by self-criticism or fear of failure. Recognizing this dual role of awareness as both an enabler and a potential constraint underscores the importance of designing interventions that balance technical training with supportive mechanisms for stress management and resilience. By integrating these dimensions, policymakers and development agencies can strengthen the financial sustainability and competitiveness of community enterprises in resource-constrained environments.

In sum, our findings highlight the dual importance of technical and cognitive resources in entrepreneurial performance. While existing literature has often emphasized technical skills such as accounting proficiency as direct predictors of outcomes, this study demonstrates that their impact is contingent on self-awareness. In doing so, it advances theory by conceptualizing self-awareness not merely as an individual trait but as a mediating mechanism that governs how technical knowledge is deployed. This integrated perspective extends the application of metacognition theory and the RBV to small-scale enterprises, offering a more nuanced account of decision-making and performance in contexts often overlooked in mainstream entrepreneurship research.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This research conducts a quantitative analysis to evaluate how accounting proficiency influences the financial performance of community enterprises in northern Thailand, with particular emphasis on the role of entrepreneurial self-awareness. The study aims to identify both cognitive and technical factors that shape financial outcomes in resource-constrained, entrepreneur-led enterprises. To achieve this, a hybrid SEM–ANN approach is employed, integrating the strengths of both statistical and machine learning methodologies. SEM is used to test the theoretical mediation framework, while ANN captures nonlinear patterns and complex interactions, thereby enhancing predictive accuracy and uncovering dynamics not easily detected through traditional methods.

The findings demonstrate three central contributions. First, accounting proficiency is positively associated with entrepreneurial self-awareness, confirming that technical competence can trigger reflective processes that enhance metacognitive vigilance. Second, self-awareness contributes positively, albeit modestly, to financial performance, indicating that while it is a valuable cognitive resource, its impact is constrained by broader institutional and market conditions. Third, the mediating role of self-awareness between accounting proficiency and financial performance appears to be limited and statistically insignificant. This suggests that technical skills alone are not sufficient, yet awareness by itself does not consistently convert knowledge into measurable financial outcomes.

The study contributes to entrepreneurship and management theory in three key ways. First, it extends metacognition theory by showing that accounting proficiency stimulates reflective processes that enhance self-awareness. Second, it advances RBV by conceptualizing self-awareness as an intangible cognitive enabler rather than a decisive mediator, highlighting that its role is to condition how technical competence translates into financial outcomes under contextual constraints. Third, by incorporating a hybrid SEM–ANN methodology, the study demonstrates that entrepreneurial performance is shaped by both linear structural relationships and nonlinear patterns, offering methodological insights for future research in small enterprise contexts.

For entrepreneurs, the findings emphasize the importance of cultivating self-awareness alongside technical accounting skills. Continuous training, self-reflection practices, and peer-learning mechanisms can help entrepreneurs critically evaluate their competencies and adapt strategies to changing market conditions. At the same time, excessive self-awareness may generate stress, anxiety, or decision paralysis, particularly in resource-constrained environments such as Thailand. Managers should therefore balance reflective practices with resilience-building and stress management strategies to ensure that awareness enhances rather than hinders performance

From a policy perspective, capacity-building programs should integrate technical accounting education with interventions designed to foster self-awareness and reflective thinking. Training curricula can incorporate diagnostic tools, mentoring, or cognitive coaching to encourage entrepreneurs to recognize limitations and adjust decision-making processes. Special attention should also be given to informal enterprises, which tend to rely more heavily on self-awareness for survival, and to resource-rich enterprises that may risk complacency without reflective practices. Importantly, policymakers should also recognize the psychological burden that heightened self-awareness may impose, and design support systems, such as stress management modules or peer networks, that enable entrepreneurs to convert reflective insights into actionable strategies. Such interventions can strengthen the financial resilience and competitiveness of community enterprises in developing country settings.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the study’s cross-sectional design restricts causal inference; longitudinal or panel data would provide stronger evidence on how self-awareness evolves over time and influences performance trajectories. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures of financial performance and awareness introduces potential bias. Moreover, the financial proxies used (e.g., minimum monthly revenue and profit ratio) may not fully capture the multidimensional nature of enterprise financial health. Future studies could integrate objective financial data and behavioral measures of awareness. Third, while the focus on northern Thailand provides important context-specific insights, it also limits the generalizability of the findings. Comparative studies across regions or countries would help test the robustness of these relationships in different institutional environments. Finally, although the hybrid SEM–ANN approach improves predictive power, the interpretability of ANN outputs remains limited. Future research could explore explainable AI techniques to increase transparency in modelling nonlinear dynamics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Y.; methodology, N.C.; validation, N.C. and R.T.; formal analysis, N.C.; investigation, K.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.; writing—review and editing, R.T.; supervision, R.T.; project administration, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Center of Excellence in Econometrics, Chiang Mai University and Chiang Mai Rajabhat University. Grant number: cee2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was reviewed and approved under the Exemption Review by the Institutional Review Board of Chiang Mai Rajabhat University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Accountancy, Faculty of Management Sciences, Chiang Mai Rajabhat University, for its financial support. This research was also partially supported by Chiang Mai University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdallah, W., Harraf, A., Ghura, H., & Abrar, M. (2024). Financial literacy and small and medium enterprises performance: The moderating role of financial access. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/jfra/article-abstract/doi/10.1108/JFRA-06-2024-0337/1253292/Financial-literacy-and-small-and-medium?redirectedFrom=fulltext (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Ahmed, S. F., Alam, M. S. B., Hassan, M., Rozbu, M. R., Ishtiak, T., Rafa, N., Mofijur, M., Shawkat Ali, A. B. M., & Gandomi, A. H. (2023). Deep learning modelling techniques: Current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artificial Intelligence Review, 56(11), 13521–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, A. S., Alnoor, A., Zaidan, A. A., Albahri, O. S., Hameed, H., Zaidan, B. B., Peh, S. S., Zain, A. B., Siraj, S. B., Masnan, A. H. B., & Yass, A. A. (2022). Hybrid artificial neural network and structural equation modelling techniques: A survey. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 8(2), 1781–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Emran, M., Abbasi, G. A., & Mezhuyev, V. (2021). Evaluating the impact of knowledge management factors on M-learning adoption: A deep learning-based hybrid SEM-ANN approach. In Recent advances in technology acceptance models and theories (pp. 159–172). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anggara, B., & Djamaluddin, A. S. (2024). Empowering entrepreneurs: Financial strategies for community-based SME. Golden Ratio of Community Services and Dedication, 4(2), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aránega, A. Y., Núñez, M. T. D. V., & Sánchez, R. C. (2020). Mindfulness as an intrapreneurship tool for improving the working environment and self-awareness. Journal of Business Research, 115, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, W. C., Jr., Prahinski, C., & Fan, Y. (2020). The influence of supplier development programs on supplier performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 230, 107793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, V. K., Dodd, N. G., & Brown, F. W. (2011). The impact of emotional intelligence on accuracy of self-awareness and leadership performance. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 32(2), 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brieger, S. A., Bäro, A., Criaco, G., & Terjesen, S. A. (2021). Entrepreneurs’ age, institutions, and social value creation goals: A multi-country study. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 425–453. [Google Scholar]

- Caliendo, M., Kritikos, A. S., Rodriguez, D., & Stier, C. (2023). Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial performance of start-ups. Small Business Economics, 61(3), 1027–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2019). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmen, P., & Rodríguez, E. (2014). Financial literacy and the success of small businesses: An observation from a small business development center. Numeracy, 7(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C. M. (2018). Management and cost accounting (10th ed.). Cengage Learning EMEA. [Google Scholar]

- Elnagar, A., Afyouni, I., Shahin, I., Nassif, A. B., & Salloum, S. A. (2021). The empirical study of e-learning post-acceptance after the spread of COVID-19: A multi-analytical approach based hybrid SEM-ANN. arXiv, arXiv:2112.01293. [Google Scholar]

- Eniola, A. A., & Entebang, H. (2017). SME managers and financial literacy. Global Business Review, 18(3), 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R., & Wegener, D. T. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentelsaz, L., González, C., & Maicas, J. P. (2019). Formal institutions and opportunity entrepreneurship. The contingent role of informal institutions. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 22(1), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, A., Kurniawati, E. D., & Suhartini, D. (2024). Self-awareness dalam perilaku etis profesi akuntansi: Bibliometric literature review. Nominal Barometer Riset Akuntansi Dan Manajemen Indonesia, 13(2), 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D. C. (2007). Upper echelons theory: An update. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Jones, C. (2021). Educating towards the prudent entrepreneurial self–an educational journey including agency and social awareness to handle the unknown. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(9), 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat-ur-Rehman, I., & Alsolamy, M. (2023). A SEM-ANN analysis to examine sustainable performance in SMEs: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(4), 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, H., & Aziz, H. (2022). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to measure the validity and reliability constructs of historical thinking skills, Tpack, and application of historical thinking skills. International Journal of Education, Psychology, and Counseling, 7(46), 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lans, T., Biemans, H., Mulder, M., & Verstegen, J. (2010). Self-awareness of mastery and improvability of entrepreneurial competence in small businesses in the agrifood sector. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(2), 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurcharusmee, S., Maneejuk, P., Yamaka, W., Thaiprasert, N., & Tuntichiranon, N. (2022). Survival analysis of Thai micro and small enterprises during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 23(5), 1211–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1961). The johari window. Human Relations Training News, 5(1), 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, P. M. (Ed.). (2010). Resource based view (RBV) of competitive advantage: An overview. In Resource based view: Concepts and practices (pp. 3–22). The Icfai University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maneejuk, P., Sukinta, P., Chinkarn, J., & Yamaka, W. (2024). Does the resumption of international tourism heighten COVID-19 transmission? PLoS ONE, 19(2), e0295249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, M. A., Ramayah, T., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Chuah, F., & Cham, T. H. (2021). PLS-SEM statistical programs: A review. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 5(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myyryläinen, H. (2022). Educating social entrepreneurship competences in the higher education: Towards collaborative methods and ecosystem learning. The Publication Series of LAB University of Applied Sciences, Part 44. LAB University of Applied Sciences. ISBN 978-951-827-409-7. [Google Scholar]

- Nakhonsong, P., & Chamruspanth, V. (2024). Promoting community enterprises in Thailand: Challenges and opportunities. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 18(4), e06505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navis, C., & Ozbek, O. V. (2016). The right people in the wrong places: The paradox of entrepreneurial entry and successful opportunity realization. Academy of Management Review, 41(1), 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. In Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook (pp. 97–146). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- OSMEP. (2022). White paper on MSME 2022. Office of Small and Medium Enterprises Promotion. Available online: https://www.sme.go.th/uploads/file/20240520-095343_MSME_White_Paper_on_2022.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Putsom, S. (2021). The testing of the reliability and validity of accounting and financial skills measures: An empirical evidence of Thai dairy farm entrepreneurs. St. Theresa Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 7(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ragas, M. W., & Culp, R. (2021). Business acumen and professional development. In Business acumen for strategic communicators: A primer (pp. 197–211). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Raut, R. D., Priyadarshinee, P., Gardas, B. B., & Jha, M. K. (2018). Analyzing the factors influencing cloud computing adoption using three stage hybrid SEM-ANN-ISM (SEANIS) approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 134, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, R. (2015). Organizational self-awareness in the key to knowledge superiority. Naval Postgraduate School. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/AD1009207.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Shepherd, D. A., & Patzelt, H. (2017). Trailblazing in entrepreneurship: Creating new paths for understanding the field. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Showry, & Manasa, K. V. L. (2014). Self-awareness—Key to effective leadership. Social science research network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2506605 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Soomro, R. B., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Dahri, N. A., Almuqren, L., Al-Mogren, A. S., & Aldaijy, A. (2025). A SEM–ANN analysis to examine impact of artificial intelligence technologies on sustainable performance of SMEs. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapituxwong, S., Chimprang, N., Yamaka, W., & Polard, P. (2023). A lasso and ridge-cox proportional hazard model analysis of thai tourism businesses’ resilience and survival in the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability, 15(18), 13582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurmond, L. R. (2019). The entrepreneurial experience of business loss: Grounded theory [Doctoral dissertation, Capella University]. [Google Scholar]

- Veselinovic, D., Antoncic, J. A., Antoncic, B., & Grbec, D. L. (2022). Financial self-efficacy of entrepreneurs and performance. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 27(01), 2250002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024, April). Thailand overview: Development news, research, data. World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/overview (accessed on 30 April 2024).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).