Abstract

The growing complexity of financial markets, driven by globalization and digitalization, has increased the need for individuals to make informed financial decisions. In this context, financial education and personal finance have become crucial areas of study. This systematic review aimed to identify and analyze the existing scientific evidence on these topics, determine the countries contributing to the literature, and extract key conclusions and lessons. A comprehensive search was conducted across the Scopus, Scielo, and La Referencia databases using keywords in Spanish. The initial query yielded 97 documents, which were filtered using seven inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in a final sample of 19 relevant articles. The reviewed studies highlight that financial education is a key factor in promoting economic well-being, reducing over-indebtedness, supporting entrepreneurship, and enhancing social inclusion. The effectiveness of financial education depends on equitable access to information, the use of digital tools, tailored approaches for diverse populations, and systematic program evaluation. The findings suggest that collaborative efforts between governments, educational institutions, and the financial sector are necessary to develop inclusive and practical financial education strategies, particularly for vulnerable populations. Financial education must be approached as a continuous, adaptive process to effectively respond to evolving economic challenges.

1. Introduction

In today’s context, financial education and personal finance have gained increasing relevance due to the complexity of financial markets and the growing need for informed decision-making. Globalization and digitalization have transformed the economic landscape, presenting both opportunities and challenges for individuals (). Recent research highlights the importance of financial education in enhancing decision-making, reducing debt, and promoting savings (; ). The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed the vulnerability of individuals with low financial literacy, underscoring the urgent need to strengthen educational strategies in this domain ().

This study focuses specifically on Latin America due to the region’s pronounced financial inclusion gaps, high levels of economic informality, and institutional efforts to improve financial literacy through national strategies. Countries in this region have implemented diverse policies—such as Mexico’s National Strategy for Financial Education and Chile’s financial literacy programs—which make Latin America an important area for comparative analysis. Furthermore, despite cultural and institutional diversity, many Latin American nations share similar socioeconomic challenges (e.g., youth unemployment, access to banking services, and informal labor markets), making cross-country insights relevant and mutually informative.

Historically, financial education and money management were grounded in traditional practices and personal experience, with limited access to financial products (). However, the growing sophistication of financial markets has increased the demand for specialized financial knowledge to help individuals avoid risks and improve their economic well-being ().

At the international level, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) developed the Financial Education Indicator (FEI), which assesses financial knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors across various countries. Within the G20, the average FEI score stands at 60.47%, with France leading at 70.95%, followed by Norway and Canada. Mexico, by contrast, scores 57.62%, ranking 12th and trailing behind countries like Indonesia. These figures reflect the need to enhance financial education in Mexico to improve financial inclusion and overall economic well-being ().

One of the main obstacles to improving financial education is the increasing complexity of the financial sector. Individuals with limited financial knowledge often struggle to understand and capitalize on available opportunities, which can lead to financial exclusion (; ). Empirical evidence suggests that countries with higher levels of financial literacy tend to experience lower social inequality and greater economic stability (; ).

The future of financial education is being shaped by digitalization and technology, requiring new skills for managing economic resources (). Innovative strategies such as gamification, artificial intelligence, and access to digital educational programs are ushering in a new era of financial literacy (; ). It is also expected that financial education will be increasingly integrated into school and university curricula, supported by both governmental and private sector initiatives ().

Financial inclusion and money management education are essential to reducing economic inequality and promoting social well-being (). Financial literacy empowers individuals to manage their income, expenses, savings, and credit, enabling responsible and sustainable financial decision-making (). This study aimed to contribute to the academic and practical discourse on improving financial education and its implications for individual and collective economic stability.

Despite increasing global attention, there remains a scarcity of systematic analyses that synthesize Spanish-language empirical research on financial education in Latin America. This review fills a critical gap by focusing on contextually specific studies often overlooked in global syntheses dominated by the English-language literature. By concentrating on this linguistic and regional subset, the study offers localized insights that are vital for tailoring financial education policies in Latin American countries. In doing so, it advances the field by providing a unique, culturally grounded understanding of how financial literacy manifests in diverse sociopolitical and economic environments.

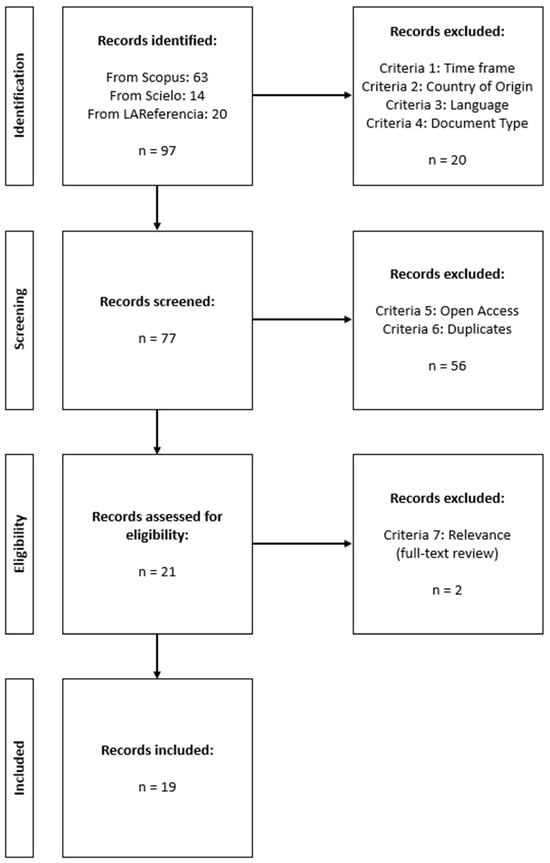

This systematic review seeks to compile and analyze the existing evidence on the relationship between financial education and personal finance. To this end, the PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses), which provide a structured protocol to ensure transparency and replicability in evidence synthesis, were used to rigorously select studies indexed in Scopus and Scielo.

In addition to exploring the relationship between financial education and personal finance and identifying the countries contributing to this field, this systematic review pursued several broader objectives. It aimed to synthesize the empirical evidence available in the Spanish-language academic literature from Latin America, while also examining the theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, and analytical tools employed by the selected studies. Moreover, it sought to assess the quality and consistency of the research, identify common patterns and divergences, and evaluate the practical implications of financial education initiatives across different contexts and populations.

The review also aimed to generate evidence-based recommendations for educational policymakers, financial institutions, and community organizations, as well as to propose directions for future research that address current gaps and expand the regional and thematic scope of the literature. Through this comprehensive approach, the study sought not only to document what has been researched but also to offer critical insights that could inform more inclusive and effective financial education strategies in Latin America.

Accordingly, the review addresses the following guiding questions: What scientific evidence exists on the relationship between financial education and personal finance in Latin America? Which countries have contributed to this field through empirical research? What conceptual and methodological frameworks are used in these studies? What are the main findings and practical lessons reported? What contradictions or limitations emerge from the literature? And how can this accumulated knowledge inform future studies and policy development?

2. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Scope

To ensure a rigorous and coherent systematic review aligned with the proposed objectives, it was essential to first establish a theoretical framework to guide the selection, organization, and interpretation of the analyzed literature. Accordingly, an integrated conceptual framework was developed based on the key foundations of financial education, financial literacy, financial behavior, and economic well-being—critical categories for understanding the role of financial education in personal and social decision-making.

The relationship between financial education and personal finance is central to understanding how individuals acquire, interpret, and apply knowledge in real-life situations. Financial education not only increases cognitive understanding of economic concepts but also equips individuals with practical tools to manage income, budgeting, savings, investment, and debt. Several studies suggest that improved financial literacy leads to more informed financial behaviors, which in turn contribute to enhanced financial security and long-term well-being (). This interplay highlights the need to examine both knowledge acquisition and behavioral outcomes in a unified framework.

From an international perspective, the OECD () defines financial education as the process by which individuals improve their understanding of financial products, concepts, and risks, developing the skills and confidence needed to make informed decisions and enhance their financial well-being. This definition has been widely adopted by Latin American countries in the design of national strategies, while also being reviewed and expanded by the contemporary academic literature. For instance, in Mexico, the National Financial Education Strategy has been examined in recent empirical studies. It has been reported that higher levels of financial literacy are significantly associated with a greater likelihood of formal retirement planning (). Additionally, a close relationship between financial inclusion and financial literacy levels in the Mexican context has been identified (). In Chile, it has been found that only 47% of the population understood compound interest, and just 18% understood inflation; nonetheless, a positive correlation between financial literacy and retirement planning behavior has been observed (). Moreover, strategic policy progress in countries such as Mexico, Chile, and Colombia has been highlighted in a recent systematic review of financial literacy research in Latin America and the Caribbean ().

Authors such as () and () propose an analytical between financial literacy—as a basic level of knowledge and understanding of financial concepts—and financial education—as a comprehensive formative process that involves attitudes, habits, and capabilities applied in real-life contexts. This distinction proved useful in coding the approaches of the reviewed studies, particularly those assessing behavioral variables in addition to self-reported knowledge.

The operational framework adopted in this review is the Lusardi and Mitchell model (), widely validated internationally, which measures financial literacy through three domains: understanding compound interest, inflation, and risk diversification. This approach has been replicated and adapted in several Latin American studies, serving as a comparative basis for analyzing the instruments used in the included research.

From a behavioral perspective, the field of behavioral finance was also considered, particularly the contributions of Kahneman () and Thaler (), who demonstrate how financial decisions are influenced by cognitive biases, heuristics, and emotional factors—even among individuals with formal financial knowledge. This framework is essential for understanding why access to financial information alone does not always translate into rational and sustainable economic behavior. This perspective was integrated into the analysis of studies including variables such as financial self-confidence, credit use, or savings propensity.

Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior () was also incorporated to interpret studies evaluating attitudes and perceptions regarding personal financial management. This theory suggests that human behavior is influenced by attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—factors observed in research on students, entrepreneurs, and employees.

From a structural standpoint, Sen’s capabilities approach () was included, which posits that financial education should be seen not merely as a practical tool but as a means of expanding individuals’ real freedoms. This perspective helped contextualize findings from studies conducted in vulnerable sectors (e.g., rural youth, older adults, women, and informal workers), highlighting the need for equity-sensitive and inclusive educational approaches.

Finally, a critical view of public policy was adopted, drawing on authors such as Willis (), who argues that some financial education programs may act as mechanisms for shifting responsibility to individuals without challenging the structural conditions that foster financial exclusion. This lens enabled a deeper interpretation of findings from articles discussing the effectiveness, implementation, and evaluation of financial education policies in the region.

This diverse set of approaches allowed the classification of empirical evidence based not only on methodological rigor but also on theoretical coherence. Accordingly, the analysis of selected articles aimed to identify patterns, contradictions, conceptual gaps, and potential directions for future research, offering a comprehensive and critical synthesis of the current state of knowledge in the field of financial education and its relationship with personal finance.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a systematic review methodology, strictly adhering to the PRISMA guidelines (; ). The selection of this approach was based on its ability to offer a comprehensive and transparent analysis of the existing literature, making it a suitable tool for synthesizing previous research, identifying patterns and emerging trends, and highlighting areas for future inquiry in the field of personal finance ().

The systematic review was characterized by a structured and detailed analysis of the available evidence related to a clearly defined research question. The process included a critical appraisal of the identified studies, ensuring a rigorous and consistent approach to the selection and evaluation of sources ().

The literature search was conducted across two main databases: Scopus and Scielo. Scopus was selected due to its recognized academic credibility and broad coverage in the social sciences and humanities (). However, given the initially limited number of results, the search was expanded to include Scielo (), a key regional database in Ibero-America with a significant repository of publications in Spanish.

The review was limited to Spanish-language articles for two main reasons. First, the intent was to explore financial education within its original linguistic and cultural context, as Spanish is the predominant language of academic communication in most Latin American countries. This focus enables deeper engagement with region-specific terminology, policy debates, and educational practices that are often underrepresented in the English-language literature. Second, much of the relevant and context-sensitive research on financial education in Latin America is published in local and regional journals not indexed in global databases or available in English. While this linguistic and regional scope ensures contextual relevance, it also introduces limitations, particularly regarding generalizability and the exclusion of potentially valuable English-language or Portuguese-language studies. These constraints are further discussed in Section 6.

The review included studies published in Spanish. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the topic, the following search terms were used in titles, abstracts, and keywords: Finanzas personales (Personal finance), Gestión financiera personal (Personal financial management), Planificación financiera (Financial planning), Educación financiera (Financial education), Bienestar financiero (Financial well-being), Ahorro personal (Personal savings), Inversión personal (Personal investment), and Presupuesto personal (Personal budgeting).

The database searches were performed on two separate dates: 19 February 2025, in Scopus, and 2 March 2025, in Scielo and LA Referencia. Although the initial plan was to conduct the review exclusively in Scopus, the limited number of retrieved records prompted the inclusion of Scielo to broaden the scope and relevance of the selected studies. The searches were carried out using institutional credentials from Universidad César Vallejo (UCV), yielding a total of 63 results (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Code, search, and initial results.

This methodological approach ensured a structured and transparent selection of the literature, allowing for a thorough and evidence-based review of the topic under study. To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, a structured appraisal was performed based on three criteria: (1) clarity and consistency of research design, (2) validity of instruments used for measuring financial literacy or behavior, and (3) robustness of data analysis methods. Studies that lacked methodological transparency or relied solely on descriptive statistics without justifying their approach were noted. While most studies adopted quantitative cross-sectional designs, only a few utilized multivariate analysis or longitudinal data. This quality assessment informed the weight given to each article in the synthesis, particularly in drawing conclusions and making recommendations.

- Selection Criteria

The following selection criteria were applied:

Criterion 1: Time frame.

A specific time interval was established for the search, covering the period from 2020 to 2025. This delimitation aimed to focus the research on the most relevant years for the topic, considering the most influential factors during that time frame and excluding studies published outside this range. As a result of this temporal criterion, 77 relevant records were identified for analysis. The decision to limit the date range from 2020 to 2025 was based on the need to capture recent developments in financial education, particularly in the post-COVID context where digital tools, behavioral strategies, and policy interventions have evolved rapidly. While it is true that academic publishing delays can result in the late appearance of impactful research, the authors prioritized recency to reflect current trends, policy frameworks, and technological applications in financial literacy.

Criterion 2: Country of origin.

Priority was given to articles whose geographical context focused on Latin American countries, excluding those with a primary focus on other regions. This decision was based on the relevance of personal finance within the Latin American context and the linguistic segmentation of the literature. Based on this geographical selection criterion, 10 records were excluded, reducing the set of relevant articles to 67.

Criterion 3: Language.

Considering the linguistic diversity of Latin America, the search was limited to the predominant language in the region’s scientific communication: Spanish. Based on this language criterion, 2 additional records were excluded, resulting in a total of 59 pertinent articles.

Criterion 4: Document type.

Only original research articles related to personal finance and/or financial education were included. Other types of publications—such as literature reviews, editorials, and letters to the editor—were excluded. This criterion led to the removal of 24 articles, reducing the number of relevant records to 35.

Criterion 5: Open access.

The availability of free access to the preselected articles through Scopus was assessed. However, due to editorial policy restrictions, some studies could not be freely downloaded. Consequently, 13 records were excluded, leaving 22 articles eligible for analysis. The use of an open-access filter was based on practical considerations of accessibility and transparency. Given that many institutions and researchers in Latin America face restrictions in accessing paywalled journals, focusing on open-access sources ensures that the reviewed literature is broadly available for verification, replication, and policy translation. Nonetheless, we recognize that this filter may have excluded high-impact publications that are not freely accessible, which is a limitation we acknowledge and recommend addressing in future research with broader access privileges.

Criterion 6: Duplicates.

A thorough check was conducted to ensure there were no duplicate studies in the final sample, guaranteeing that each included article contributed unique and relevant information to the review. This process confirmed that the 21 selected records were distinct and valid.

Criterion 7: Relevance (full-text review).

Each scientific article was individually evaluated for its relevance to the research question. During this stage, two systematic reviews were identified among the articles. This detailed assessment confirmed that the final 19 records met all previously established selection criteria.

The entire process is summarized in Table 2. Additionally, Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram for systematic reviews and meta-analyses ().

Table 2.

Initial, partial, and final results for each database and in total.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

4. Results

The nineteen identified records are shown in Table 3. In addition, it indicates the assigned code, title of the scientific article, authors, and name of the journal.

Table 3.

Citation, title, and journal of the scientific research identified.

The research presented in Table 2 consistently explores several critical aspects of financial education. A dominant theme is the impact of financial education on various demographics, particularly university students (e.g., ; ), youth (), and specific professional sectors like metalworking employees () or food sector workers (). This focus underscores a recognition of the importance of financial literacy across different life stages and professions.

Another significant area of inquiry revolves around the relationship between financial education and indebtedness, especially concerning the use of credit cards () and microcredit services (). This highlights a practical concern with how financial knowledge translates into responsible financial behavior and debt management.

Furthermore, several studies explore the broader concept of financial well-being (; ), examining its drivers and implications for different consumer groups, including digital consumers. The table also reveals an interest in behavioral aspects of financial decision-making and bias mitigation (), suggesting a move beyond purely knowledge-based approaches to financial education. Emerging themes include the social impact of technology on financial education () and the role of public policy and media in financial education strategies (). The impact of external events like COVID-19 on personal finances also features, indicating a responsiveness to contemporary challenges.

The journals in Table 2 predominantly cater to economics, finance, management, and social sciences, with a strong regional presence. The Revista Venezolana de Gerencia stands out as a highly recurring publication venue, indicating its prominence for research originating from and focusing on the region. Similarly, the Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas is frequently cited, underscoring its relevance for financial and economic studies in Mexico and potentially the wider Latin American context.

Other notable journals include Revista Latinoamericana de Economía, European Public & Social Innovation Review, and Sapienza: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, suggesting a mix of regional and broader international outlets. The inclusion of journals like Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodistico, Revista pedagogía universitaria y didáctica del derecho, and CONDUCIR. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to financial education research, extending beyond traditional economic and financial disciplines to incorporate areas like communication, pedagogy, and law. This diverse range of journals reflects the interdisciplinary nature of financial education as a field of study.

It is fundamental to specify the country of origin for the experiences detailed in each of the identified scientific articles. This information is crucial for contextualizing the findings and evaluating the applicability of the results in different geographical contexts. In that regard, Table 4 presents this information.

Table 4.

Citation and country of country of origin for the experiences detailed in each of the identified scientific articles.

According to Table 4, the identified scientific articles primarily originate from a limited number of countries, which is crucial for contextualizing findings and assessing the applicability of results across diverse regional settings. Of the 19 articles included in this review, the majority, specifically 9 studies (47.4%), originate from Mexico. Colombia is the second most represented country, contributing four articles (21.1%). Peru, Chile, and Ecuador each account for two articles, representing 10.5% of the total. This distribution highlights a predominant focus on experiences from Mexico and Colombia within the selected literature, providing a valuable but geographically concentrated perspective on the phenomena explored.

Although the sample leans heavily toward studies conducted in Mexico and Colombia, this pattern may reflect publication dynamics in regional academic networks and access to indexed Spanish-language sources rather than an actual research monopoly. Notably absent are contributions from Central American countries, the Caribbean, and parts of the Andean region such as Bolivia or Paraguay. Future reviews should intentionally include broader regional coverage by expanding database reach (e.g., Latindex, RedALyC), including Portuguese-language studies from Brazil, and considering the gray literature where appropriate. This would offer a more inclusive and representative view of Latin American financial education efforts.

Finally, Table 5 presents the conclusions drawn from each article, accompanied by key lessons learned. This is important as it allows for a synthetization of the diverse findings, identifying common themes, best practices, and recurring challenges. It also facilitates the transferability of knowledge by highlighting practical implications and potential future research directions derived from the collective experiences.

Table 5.

Citation, conclusion and lessons learned for the experiences detailed in each of the identified scientific articles.

5. Discussion

The systematic review of financial education in Latin America between 2020 and 2025 underscores the multidimensional and context-sensitive nature of financial literacy. The results emphasize that financial education cannot be addressed as a one-size-fits-all approach but rather must consider the complex interaction of demographic, socio-economic, cultural, and behavioral factors that shape how individuals engage with financial knowledge and services.

First, the persistent gender gap in financial literacy, observed in studies such as that of millennials in Ciudad Victoria, reflects broader structural inequalities. These gaps, particularly in quantitative skills, indicate that financial literacy programs must consider gender-sensitive strategies and address systemic barriers that limit women’s access to financial knowledge and tools. At the same time, the pivotal role of the family, particularly maternal education, as demonstrated in the case of Celaya, highlights the importance of early financial education within the household. This affirms that financial literacy must begin at home and be reinforced through formal education and lifelong learning opportunities.

Second, the role of behavioral finance reveals that knowledge alone is insufficient for changing financial behaviors. The influence of cognitive biases, emotional responses, and social norms on financial decisions must be addressed through educational programs that go beyond technical instruction. Integrating behavioral insights into financial education can improve outcomes by helping individuals recognize and manage their own biases.

Third, the diversity of institutional and sectoral contexts, from small businesses in Tunja to digital consumers in Riobamba, illustrates the wide range of applications for financial education. Each sector faces distinct challenges and therefore requires tailored strategies. The struggles of micro-entrepreneurs, for example, underscore the need for practical, business-focused financial training that enhances sustainability and financial inclusion.

On a systemic level, the findings indicate a disconnection between innovative financial systems and the population’s ability to use them effectively. This is particularly relevant in Mexico and Colombia, where exclusion from the financial system persists despite technological advancements. Education must therefore be aligned with broader policies of financial inclusion and regulation, ensuring that users can navigate and benefit from financial services responsibly and efficiently.

Despite general consensus on the importance of financial education, several points of contention emerged. Some studies advocate for behaviorally oriented education that accounts for psychological biases (), while others remain rooted in traditional economic models (). This reflects a deeper debate: should financial literacy be taught as technical knowledge or as a behavioral adaptation process? Additionally, while financial education is widely promoted as a pathway to empowerment, critical voices argue that it may shift the burden of systemic financial failure onto individuals without addressing structural inequities (). These tensions highlight the need for financial education to be both pedagogically sound and socially conscious.

While digital technology offers promising tools for expanding access to financial information, its effectiveness depends on the existence of appropriate communication strategies and digital literacy. The Chilean case study shows that the absence of an effective communication plan can undermine the potential of educational initiatives, reinforcing the importance of integrating digital tools with community-based education and public policy.

The review also reveals underlying tensions within the academic discourse. While some studies emphasize the role of formal curricula and policy frameworks, others argue that grassroots, community-driven models are more effective in fostering lasting financial behavior change. Moreover, inconsistencies emerge regarding the impact of financial literacy on behavioral outcomes: in some cases, higher knowledge levels did not translate into responsible credit use or improved savings, highlighting the complex mediation by psychological, cultural, and institutional factors. There is also debate about the responsibility of financial education—whether it should rest on the individual or be seen as a collective, structural endeavor. These points of divergence reflect the multifaceted nature of financial literacy and call for a more pluralistic approach to both research and intervention.

Last, it is acknowledged that the final sample includes studies from only five Latin American countries: Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Ecuador. While these countries provide valuable insights into financial education practices in the region, they do not fully represent the institutional, economic, and cultural heterogeneity of Latin America. Mexico and Colombia, for example, are among the largest economies in the region, whereas Ecuador and Peru represent smaller but increasingly relevant cases. As such, the findings should be interpreted with caution when generalizing to the entire Latin American context. Nevertheless, the thematic and methodological diversity of the included studies offers a foundation for comparative insights and suggests directions for expanding future research to other countries in the region.

6. Recommendations

Based on the insights gained from the systematic review, the following recommendations are proposed to guide the development and implementation of effective financial education policies and programs.

6.1. Integrate Financial Education into National Curricula

There is a pressing need for financial education to be incorporated as a mandatory component of national education systems from early childhood through to tertiary education. The reviewed studies have highlighted the existence of curricular gaps in the formal training of youth, particularly among students from non-finance disciplines, where content is fragmented and often lacks practical application (). In addition, the family environment, particularly the role of mothers as financial role models, has been shown to significantly influence financial habits and attitudes among Generation Z youth (). This underscores the importance of introducing financial education at a young age to complement family-based learning and ensure equity in early financial socialization.

A curriculum that is culturally relevant and aligned with local realities is essential to address socioeconomic diversity across Latin American regions. Teaching methods should emphasize experiential learning, including simulations, problem-solving, budgeting games, and storytelling, to translate abstract concepts into real-life applications. The use of context-specific examples, such as informal labor and local saving strategies, can enhance relevance and engagement. Additionally, teacher training programs must be expanded to equip educators with the pedagogical and financial competencies required to deliver this content effectively.

6.2. Target Vulnerable Populations Through Community-Based Programs

Community-based financial education programs should be designed to specifically target vulnerable and underserved populations such as informal workers, rural youth, women, older adult citizens, and migrants. The reviewed literature indicates that these groups often face significant financial exclusion due to geographic, educational, and socioeconomic barriers (; ). In rural areas of Colombia and Ecuador, for example, financial literacy is limited by a lack of access to information, banking infrastructure, and formal identification documents ().

Mobile literacy centers, radio-based education, and culturally embedded workshops led by community leaders have been identified as effective outreach strategies in similar contexts. Programs should integrate adult learning principles, accommodate low literacy levels, and reflect local cultural and gender norms. Interventions must be co-designed with the community to ensure relevance and build trust. Evidence also suggests that financial education initiatives are most effective when delivered in the context of practical needs (such as managing household expenses, microenterprise development, or accessing remittance services).

Furthermore, public–private partnerships and civil society involvement are crucial in reaching these populations. Local NGOs, microfinance institutions, and cooperatives often serve as trusted intermediaries and can facilitate access to these populations more effectively than centralized state programs.

6.3. Promote Workplace Financial Education

Financial education should also be embedded into workplace training programs, particularly for low- and middle-income employees. Studies conducted among metalworking employees in Mexico () and food sector workers () confirm the positive relationship between financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction. Improved financial literacy among workers has been associated with better personal budgeting, lower financial stress, and increased productivity, ultimately benefiting both employees and employers.

Workplace programs can be delivered through periodic workshops, digital platforms, and mentoring sessions. Topics should include retirement planning, debt management, insurance literacy, and emergency savings. Incentives such as financial wellness certifications or recognition awards can increase participation and reinforce behavioral change. Employers should be encouraged—through tax benefits or corporate social responsibility metrics—to institutionalize these programs as part of employee wellness and human capital development.

Moreover, financial education should not be limited to salaried employees. Freelancers, gig workers, and informal traders represent a growing segment of the labor market and face heightened financial insecurity. Tailored programs that address irregular income patterns, taxation, and basic rights are urgently needed for these groups.

6.4. Hold Financial Institutions Accountable for Education

Financial institutions play a critical role in shaping consumer behavior and must be held accountable for promoting financial literacy. The review revealed that many users—especially of credit products—lack the foundational knowledge to make informed financial decisions, leading to cycles of over-indebtedness (; ). Studies also show that mistrust in financial institutions and self-exclusion are common among low-income populations in Colombia and Peru, driven in part by a lack of transparency and support in customer interactions.

Regulators should require banks and credit providers to develop standardized, accessible educational resources, such as credit cost calculators, loan simulators, budgeting guides, and financial rights handbooks. These tools should be available in multiple languages and literacy levels, including audio and visual formats. Branch staff should be trained in financial empowerment principles and incentivized to guide customers through product selection and risk assessment.

Additionally, financial institutions should be evaluated based on their contributions to financial education as part of their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) or corporate social responsibility (CSR) indicators. Public reporting on education initiatives and outcomes would enhance transparency and motivate meaningful engagement beyond token compliance.

6.5. Strengthen Monitoring and Evaluation Systems

Despite increasing investment in financial education, few programs rigorously evaluate their effectiveness. Several studies emphasized the lack of consistent indicators and the reliance on self-reported knowledge metrics, which may not correlate with actual behavior change (; ). To improve accountability and learning, all financial education interventions must be accompanied by robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks.

These frameworks should assess not only knowledge acquisition but also attitudinal shifts, behavioral outcomes, and longer-term economic impacts. Mixed-methods approaches—combining quantitative indicators with qualitative interviews and focus groups—can offer a more comprehensive understanding of program performance. Longitudinal studies are particularly valuable for assessing habit formation, resilience to financial shocks, and intergenerational transmission of financial attitudes.

Digital platforms provide opportunities for real-time data collection and adaptive programming. For example, interactive modules can track user engagement, learning progression, and behavioral intentions, providing rich data for continuous improvement. National financial education strategies should include dedicated funding for independent evaluation and public dissemination of results to promote transparency and cross-institutional learning.

6.6. Leverage Technology Without Exacerbating Inequality

Digital technologies (such as mobile apps, gamified learning platforms, and e-wallet simulations) offer innovative ways to deliver financial education at scale. The literature points to the growing use of digital tools among young and urban populations, particularly in Ecuador and Mexico (; ). However, technological solutions also risk deepening existing inequalities if access to devices, connectivity, and digital literacy is not simultaneously addressed.

Effective programs must therefore combine online and offline modalities, especially in regions with limited infrastructure or high levels of digital exclusion. Hybrid models, including in-person facilitation, printed materials, and community radio, can complement app-based learning. Programs targeting older adults or rural populations should integrate technology gradually, with hands-on training and peer support.

Public investment in broadband access, community tech centers, and low-cost devices is essential to support the equitable rollout of digital financial education. Additionally, developers of educational technology must consider inclusivity in design—using simple interfaces, local dialects, and culturally resonant imagery—to ensure usability by marginalized users.

6.7. Align Financial Education with Broader Development Goals

The role of financial education extends beyond individual competence to collective well-being and thus should be explicitly linked to national development agendas. Research grounded in the human development theory () positions financial education as a mechanism for expanding freedoms, fostering civic engagement, and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Evidence from Mexico shows that increased financial literacy correlates with improved income, consumption patterns, and social inclusion ().

Policymakers should embed financial literacy objectives into strategies for poverty reduction, gender equity, youth employment, and economic formalization. This would require intersectoral coordination between ministries of finance, education, labor, and social protection. For instance, financial education can be integrated into conditional cash transfer programs, entrepreneurship grants, and school-to-work transition schemes.

By positioning financial literacy as a public good and human right, governments can elevate its political visibility and justify sustained investment. Furthermore, aligning financial education with national development goals opens opportunities for international cooperation, donor funding, and regional benchmarking.

6.8. Address Structural Determinants of Financial Exclusion

Finally, the effectiveness of financial education is limited unless accompanied by broader structural reforms that remove systemic barriers to financial inclusion. Several reviewed studies point to issues such as lack of formal identification, geographic distance from banking institutions, discriminatory lending practices, and predatory credit terms (; ). These constraints disproportionately affect low-income, rural, and marginalized populations.

Policymakers must therefore implement complementary measures, such as simplified know-your-customer (KYC) procedures, expanded rural banking networks, capped interest rates for microloans, and consumer protection laws. Financial education programs should be aligned with these efforts, ensuring that newly acquired knowledge can be applied in safe and accessible environments.

Multi-stakeholder coalitions (including regulators, consumer advocacy groups, fintech developers, and civil society) should be established to coordinate efforts and ensure systemic coherence. These coalitions can also monitor unethical practices, develop inclusive product standards, and promote innovation that prioritizes equity and transparency.

7. Future Research Agenda and Study Limitations

While this systematic review provides important insights into the state of financial education in Latin America, it also reveals significant gaps in current knowledge and practice that warrant further academic exploration. Future research should address the following areas:

Most existing studies rely on cross-sectional designs. There is an urgent need for longitudinal research that tracks individuals over time to assess the long-term impact of financial education on behavior, resilience to economic shocks, and intergenerational financial knowledge transmission.

Financial behavior is shaped by a combination of economic, psychological, sociological, and cultural factors. Future studies should adopt interdisciplinary frameworks that incorporate behavioral economics, cultural studies, gender theory, and educational psychology to better understand how different populations engage with financial concepts.

Given the rise of informal employment and gig work in Latin America, research should explore how financial education can be tailored to the needs of workers with irregular income streams, lack of access to formal credit, and limited social protections.

There is a need for comparative studies that examine how different countries and regions approach financial education, particularly in terms of curriculum design, implementation models, and evaluation strategies. Such studies can provide valuable lessons and foster regional cooperation and policy harmonization.

Further investigation is needed into the role of fintech applications, mobile banking platforms, and social media in disseminating financial information. Research should examine both the opportunities and risks associated with digital financial education, particularly for youth and low-literacy users.

More research is needed on how children acquire financial attitudes and behaviors from parents, schools, and media. Understanding early socialization processes can inform the design of interventions aimed at building financial competence from a young age.

Future studies should seek to include a broader range of Latin American countries. The present review draws primarily from five nations—Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Ecuador—which, although informative, do not fully capture the institutional, economic, and cultural heterogeneity of the region. While Mexico and Colombia represent two of the largest economies in Latin America, countries such as Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, or the Central American nations remain underrepresented in empirical financial education research. Including a more geographically diverse set of countries would strengthen the regional applicability of future findings and allow for comparative analyses that reflect the full complexity of financial literacy challenges and policy responses across Latin America.

This review is subject to several limitations that future studies should consider addressing. First, the decision to include only articles published in Spanish and within the 2020–2025 period may have excluded relevant studies published earlier or in English and Portuguese, particularly research from Brazil, a key player in Latin American financial education. While the aim was to reflect the most recent developments in a shared linguistic context, this necessarily restricted the breadth of perspectives considered.

Second, the geographic concentration of the reviewed studies—particularly the dominance of research from Mexico—limits the generalizability of findings across the broader Latin American region. Countries such as Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and many Caribbean and Central American nations were not represented, either due to lack of indexed publications or exclusion during filtering.

Third, although the review followed PRISMA guidelines and applied multiple inclusion criteria, no formal quality scoring tool (e.g., MMAT or GRADE) was used. While methodological rigor was qualitatively assessed, future reviews should consider applying standardized appraisal tools to ensure comparability and to weigh evidence strength systematically.

Finally, the exclusion of paywalled articles may have led to an underrepresentation of high-impact studies. This limitation was a practical choice to ensure accessibility and transparency, but future research could benefit from institutional support to access a wider range of the literature, including restricted-access journals.

8. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that financial education is a critical but complex driver of economic well-being, inclusion, and social equity. Across Latin America, the evidence suggests that while progress has been made in recognizing the importance of financial literacy, significant disparities remain in both access to and the effectiveness of educational interventions.

The findings reveal that effective financial education must move beyond traditional, one-dimensional approaches. It must be integrated into formal education systems, adapted for different populations, informed by behavioral insights, supported by digital tools, and aligned with public policy goals. Importantly, financial education must be conceived not only as a tool for managing personal finances but as a foundational element of active citizenship and social empowerment.

By embracing an inclusive, context-sensitive, and life-course approach to financial education, policymakers, educators, and financial institutions can help build more resilient, informed, and equitable societies. The integration of financial literacy into national development strategies, coupled with robust evaluation mechanisms and cross-sector collaboration, can ensure that all individuals—regardless of gender, income, or background—have the knowledge and tools they need to navigate an increasingly complex economic world.

As Latin America continues to face the dual challenges of economic uncertainty and social inequality, financial education stands as a vital strategy for promoting sustainable development, reducing vulnerability, and fostering a culture of informed decision-making. The path forward lies not only in expanding access to knowledge but in transforming that knowledge into meaningful, lasting change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.A.-C. and V.H.F.-B.; methodology, E.J.A.-C.; software, E.J.A.-C.; validation, E.J.A.-C.; formal analysis, E.J.A.-C.; investigation, E.J.A.-C.; resources, E.J.A.-C.; data curation, E.J.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.A.-C., L.M.V.-V., and V.H.F.-B.; writing—review and editing, E.J.A.-C., L.M.V.-V., and V.H.F.-B.; visualization, E.J.A.-C.; supervision, E.J.A.-C.; project administration, E.J.A.-C.; funding acquisition, E.J.A.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad César Vallejo, in accordance with FAI 2025 program (project ID 3650).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguilar Ham, P., Beltrán Godoy, J. H., & Gaxiola Laso, S. R. (2024). Autoeficacia financiera, bienestar financiero y satisfacción laboral de los empleados del sector metalmecánico en Chihuahua, México. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 29(106), 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology and Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza García, E. d. J. (2022). Alfabetización financiera de los productores de yuca industrial en Colombia. Panorama Económico, 30(2), 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A., & Messy, F. (2012). Measuring financial literacy. No. 15. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Avad, N., Braiz Panduro, C., Pizzán Tomanguillo, S. L., & Villafuerte de la Cruz, A. S. (2022). Educación financiera y endeudamiento por uso de las tarjetas de crédito de los clientes de Plaza vea—Perú. Sapienza: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 3(1), 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Lievano, J. A., & Parra Ramirez, S. M. (2024). Educación financiera y servicios de microcrédito en empresas de la ciudad de Bogotá—Colombia. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 29(105), 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzo, S. A., & Remeseiro Reguero, R. (2021). Hacia un currículo que fortalezca la educación financiera en las carreras de Derecho. Revista Pedagogía Universitaria y Didáctica del Derecho, 8(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpena, F., Cole, S., Shapiro, J., & Zia, B. (2011). Unpacking the causal chain of financial literacy. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, L., Morales-Vargas, A., Rodríguez-Martínez, R., & Pérez-Montoro, M. (2020). Uso de Scopus y Web of Science para investigar y evaluar en comunicación social: Análisis comparativo y caracterización. index.comunicación, 10(3), 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J. M. (2013). The impacts of mandatory financial education: Evidence from a randomized field study. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 95, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Décaro-Santiago, L. A., Soriano-Hernández, M. G., Benítez-Guadarrama, J. P., & Soriano-Hernández, J. G. (2021). La conducta financiera entre estudiantes universitarios emprendedores. Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios, 89, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education and downstream financial behaviors. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2333898 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Garabato Moure, N. (2016). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 15(2), 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mata, O. (2021). Alfabetismo financiero entre millennials en Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, México. Estudios Gerenciales, 37(160), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santillán, A. (2022). Educación financiera en los trabajadores del sector alimenticio en México. Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas, 18(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). The role of Google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0138237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Mejía, S., & Moreno-García, E. (2023). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Mexico. Economics & Sociology, 16(3), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, A., Parker, A. M., & Yoong, J. (2009). Defining and measuring financial literacy. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S. J. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jappelli, T. (2010). Economic literacy: An international comparison. The Economic Journal, 120(548), F429–F451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T., & Lusardi, A. (2024). Financial literacy and financial education: An overview. NBER. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, W. (2014). Kahneman, D. (2011): Thinking, fast and slow. Statistical Papers, 55(3), 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitin, A. J. (2013). The consumer financial protection bureau: An introduction. SSRN Electronic Journal, 32, 321–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Prete, A. (2013). Economic literacy, inequality, and financial development. Economics Letters, 118(1), 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Prats, G. (2023). Tecnología y su impacto social en la educación financiera. TECHNO REVIEW. International Technology, Science and Society Review/Revista Internacional de Tecnología, Ciencia y Sociedad, 13(4), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino González, E. L. (2023). Factores que influyen en la educación financiera de los jóvenes de Celaya, Guanajuato, México. Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas, 18(3), e890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Prado, S. M., Zambrano Franco, M. J., Zambrano Zapata, S. G., Chiluiza García, K. M., Everaert, P., & Valcke, M. (2022). A systematic review of financial literacy research in Latin America and The Caribbean. Sustainability, 14(7), 3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O. S., & Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: Evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3(1), 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R. S. (2021). Household finance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academia Letters, 2237, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Hurtado, Y. A., & Ríos Matta, Y. J. (2024). Tenderos de tunja: Análisis de la gestión financiera personal. Semestre Económico, 27(62), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya Ramos, C. (2019). El papel de los medios en la comunicación de la política pública de la estrategia nacional de educación financiera en Chile. Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico, 25(3), 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno López, W., & Villarreal Cerquera, D. T. (2024). Educación financiera desde la Teoría del desarrollo humano: Un aporte conceptual para la gestión de los ODS. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungaray, A., Gonzalez Arzabal, N., & Osorio Novela, G. (2021). Educación financiera y su efecto en el ingreso en México. Problemas Del Desarrollo. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía, 52(205), 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. (2014). Financial education for youth. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2017). G20/OECD INFE report on adult financial literacy in G20 countries. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2017/07/g20-oecd-infe-report-on-adult-financial-literacy-in-g20-countries_021d12ec/04fb6571-en.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Owuor, H. O., & Jagongo, A. (2023). Financial literacy on financial performance of small and medium enterprises in Kajiado County, Kenya. Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management, 10(2), 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paker, A. L. (2014). SciELO—15 años de acceso abierto: Un estudio analítico sobre acceso abierto y comunicación científica. In SciELO—15 años de acceso abierto: Un estudio analítico sobre acceso Abierto y comunicación científica. UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñarreta-Quezada, M.-Á., Salas-Tenesaca, E.-E., Álvarez-García, J., & de la Cruz del Río-Rama, M. (2023). Variables sociodemográficas y niveles de educación financiera en jóvenes universitarios de Ecuador. Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas, 19(19), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences. In M. Petticrew, & H. Roberts (Eds.), Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrich, A. C. G., Vieira, K. M., & Kirch, G. (2015). Determinantes da alfabetização financeira: Análise da influência de variáveis socioeconômicas e demográficas. Revista Contabilidade & Finanças, 26(69), 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S. (2017). Richard H. Thaler, Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics. The Review of Austrian Economics, 30(1), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remund, D. L. (2010). Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus González, N. N., Campos Reyes, V., Reus González, T., & Macías Ocampo, M. J. (2022). Efecto COVID-19 en las finanzas personales en alumnos de pregrado. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana Para La Investigación y El Desarrollo Educativo, 13(25), e040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, M. J., & VIllegas, A. (2022). Financial exclusion and financial literacy. Evidence from Mexico. Latin American Economic Review, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cairo, V., Vílchez Olivares, P. A., Oscanoa Ponce, B. F., & Barrantes Martínez, A. M. (2024). Educación financiera con enfoque conductual y mitigación de sesgos en decisiones crediticias. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 29(108), 1560–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. (1990). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Montoya, M. M., López Torres, V. G., & Aguilar Sandoval, K. G. (2022). Endeudamiento y educación financiera en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 27(97), 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, L. E. (2008). Against financial-literacy education. Iowa Law Review, 94(1), 197–285. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J. J., & Li, H. (2011). Sustainable consumption and life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 104(2), 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambay Hernández, E. A., Chávez Hernández, Z. del R., Ortega Mosquera, J. M., & Montoya Lunavictoria, J. K. (2024). Bienestar financiero en los consumidores digitales: Un enfoque relacional de preferencia marca. Revista Venezolana de Gerencia, 29(108), 1544–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucman, G. (2019). Global wealth inequality. Annual Review of Economics, 11(1), 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).