Abstract

Purpose—This study examines the interaction of economic openness, governance, and money laundering. The paper’s main objective is to analyze how trade openness, foreign direct investment, and anti-corruption measures influence the risk of money laundering in specific economic blocs. Design/methodology/approach—This study analyzes these economic blocs (EU, G20, BRICS, and CIVETS) using annual data from the Basel Institute on Governance and World Bank statistics for 2012–2021. A panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) estimator is employed to examine the relationships among the variables, accounting for cross-sectional dependence and ensuring robust parameter estimation. The corruption control index is a proxy for governance effectiveness, though it does not directly measure regulatory strength. Future research should incorporate more specific variables to evaluate the regulatory impact. Findings—This study reveals significant variations in money laundering risks by a country’s income category and economic bloc influenced by economic openness and governance structures. Economic growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows exhibit contrasting effects on money-laundering risks; they tend to exacerbate risks in middle-income countries, while high-income nations demonstrated a lower risk of money laundering, likely due to more robust governance structures. Trade openness and anti-corruption measures generally reduced risks in wealthier countries, highlighting the importance of strong governance frameworks. These insights suggest that anti-money-laundering policies should be tailored to fit different regions’ unique economic and institutional contexts for enhanced effectiveness. Originality—This study employs a structured approach to analyzing a decade of panel data from key economic blocs, providing insights into the intricate relationships between governance, economic openness, and money laundering risks. Bridging the gap between theoretical research and practical, actionable strategies serves as a valuable resource for improving the effectiveness of anti-money-laundering (AML) measures on a global scale.

JEL Code:

D73; E02; F10; F21; F36; G00

1. Introduction

Disguising the source of one’s illicit gains through money laundering poses a severe threat to the global financial system’s stability. Money laundering challenges governments and economic systems by infiltrating legal and economic activities, distorting macroeconomic data, and fostering financial criminality (A. Al Qudah & Hailat, 2025). It pervades economies, intertwining macroeconomic data, legal activities, and financial crime. Scholars, politicians, and decisionmakers continue to debate, investigate, and thoroughly analyze the extent and ramifications of this issue.

Money laundering persists despite international efforts to combat it, necessitating a deeper understanding of its sources, methods, and associated defenses. This research examines the interplay between economic openness, governance structures, and money laundering risks, with a focus on how these factors vary across income categories and economic blocs. A careful examination of the released material reveals the complex links and dynamics between governance, economic openness, and money laundering.

Several studies (A. Al Qudah, 2024; Hendriyetty & Grewal, 2017; Kurum, 2023; Magableh et al., 2024) have demonstrated how susceptible nations with high levels of corruption are to money-laundering activities. This vulnerability underscores the importance of governance characteristics, including political stability, the rule of law, and practical efforts to combat corruption, in halting these illicit financial flows. However, governance is not a panacea on its own. A comprehensive defense against money laundering risks is formed by international cooperation and anti-corruption measures; when effectively implemented within organizations, strong corporate governance practices significantly reduce the likelihood of engaging in illegal financial activity, further strengthening this protective barrier. Although primarily associated with financial crimes, money laundering has substantial impacts on other macroeconomic indices. Understanding governance, economic indicators, and money laundering is essential for developing effective policies and initiatives (A. M. Al Qudah et al., 2025).

The primary objective of this research is to investigate the complex relationships between money laundering, governance as measured by the anti-corruption index, and economic openness, which is represented by trade openness and foreign direct investment. The study analyzes the relationship between a nation’s governance structure and its vulnerability to money laundering. It explores how variations in corruption control, trade openness, and foreign direct investment influence money laundering risks across diverse governance and economic contexts. Additionally, the research will investigate how trade openness and foreign direct investment inflows impact money laundering. Real GDP growth and the country’s income category are introduced to account for the nation’s economic performance. The research aims to utilize empirical data to provide policy recommendations that can enhance domestic and global strategies for addressing the problems caused by money laundering.

Due to their significant variability in financial systems and regulatory development, this study meticulously selects the EU, G20, BRICS, and CIVETS as focal economic blocs. The EU is widely recognized for its advanced governance mechanisms and robust anti-money-laundering regulations, as evidenced by its implementation of the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (Directive 2015/849) (Schiavo, 2022). The G20, comprising both mature and emerging economies, provides a diverse backdrop for assessing the impact of economic size on anti-money-laundering (AML) strategies. Emerging markets within BRICS provide insights into the challenges faced during rapid economic changes and regulatory evolution. Finally, the CIVETS countries, known for their dynamic and fast-growing economies, are examined to understand the unique money laundering risks in rapidly evolving markets.

While numerous studies have explored the dynamics of money laundering across different regions, this study addresses critical gaps by focusing on the interplay between economic openness, governance, and money laundering within the economic blocs of the EU, G20, BRICS, and CIVETS. Previous research has predominantly focused on a broad global perspective, often without adequate attention to the nuances of individual economic blocs, or has been limited to single-country analyses that fail to capture the broader implications of regional economic policies. Moreover, the existing literature should examine the comparative analysis of emerging versus developed markets in the context of globalization’s impact on AML efforts. This study enriches the academic discourse by providing a detailed comparative analysis that highlights how variations in governance and economic openness influence the risk and mechanisms of money laundering in these strategically critical economic blocs.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The next section provides a summary of the literature, while Section Three delves into the theoretical framework. Section Four outlines the methodology, Section Five examines the results, and Section Six concludes with policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

Money laundering remains a significant concern for international finance and governance. Research demonstrates its interplay with economic indicators and governmental frameworks, exposing intricate processes and relationships. Money laundering efforts can target nations with high levels of corruption, as shown by Masciandaro (2017) in the following example. His findings suggest that specific aspects of governance, including political stability, a robust legal system, and effective anti-corruption measures, are crucial in mitigating such illicit flows. This viewpoint is supported by a critical study (Fisman & Svensson, 2007), which shows a clear connection between high levels of money laundering and corruption. They emphasized the importance of governance indicators in combating money laundering, particularly in reducing corruption. Mohd-Rashid et al. (2023) showed that countries with high levels of political instability, weak legal systems, and corruption are more likely to have more severe money laundering cases. Additionally, their research presented a novel perspective, namely, that successful anti-money-laundering laws could stimulate more robust governance metrics. The institutional foundation of governance also draws from Acemoglu and Verdier (2000), who argue that in weak states, corruption may arise as an endogenous response to incomplete regulation—a dynamic closely tied to the risks of money laundering in transitional economies.

While governance is at the forefront of the discourse, it is imperative to maintain a balance about the critical role that control of corruption plays in mitigating the risks of money laundering. Masciandaro and Romelli (2015) provide more details on this argument. Their results suggest that countries with strong governance structures have a higher propensity to implement and maintain efficient anti-money-laundering policies. Their results support the view that enhanced legislative frameworks and international cooperation are the most effective preventive measures. Corporate governance is relevant in this situation. Companies with stringent corporate governance procedures are far less likely to participate in money laundering operations (Liu & Atuahene-Gima, 2018). Sivaprasad and Mathew (2021) further corroborate this by examining the relationship between corporate governance and financial performance, finding a positive correlation.

At the forefront of financial sector growth, Ofoeda et al. (2022b) emphasize the growing susceptibility of countries with less-developed financial infrastructures to money laundering. However, nations with well-developed financial sectors bolstered by vital governance metrics are practical barriers to money laundering. One unique feature of this conversation is e-governance and how it affects corruption. In an optimistic assessment, Ali et al. (2021) and Saxena (2017) state that implementing e-government services has led to a discernible decrease in corruption and encouraged a more transparent and trustworthy administrative environment.

Local research offers nuanced perspectives. Sharma (2020) and S. Goel (2022) highlight the inconsistent nature of India’s 2002 Prevention of Money Laundering Act, pointing to the challenges associated with implementing such frameworks. On the other hand, despite persistent difficulties, China’s post-2002 reforms demonstrate a sincere attempt to combat money laundering (Ping, 2008; Sham, 2006). Defossez (2017) and Orlova (2008) claim that systemic banking problems have impeded Russia’s efforts in this field. Significant modifications were implemented to South Africa’s legal system after 1998 to bolster the nation’s stance against money laundering (Chitimira, 2021).

Global efforts to combat money laundering have significant implications for economic and financial sectors, particularly in developing economies. This literature review synthesizes findings from recent scholarly research to explore the multifaceted impacts of (AML) regulations, focusing on economic growth, sustainable development, and financial sector development. Ofoeda et al. (2022b) explore the relationship between AML regulations and financial sector development, highlighting how stringent AML measures can support and constrain financial growth. Their study indicates that while AML regulations help stabilize financial institutions by reducing illicit flows, they can impose regulatory burdens that may inhibit financial innovation and sector expansion. Expanding on this theme, Ofoeda et al. (2022a) delve into how AML frameworks impact foreign direct investment (FDI) and economic growth. They find that robust AML systems are associated with increased FDI flows, suggesting that effective regulation curtails illicit finance, enhances economic confidence, and attracts foreign investments.

F. M. Ajide and Ojeyinka (2023) examine the broader implications of AML regulations on sustainable development in developing economies. Their exploratory analysis argues that while AML frameworks aim to reduce financial crimes, they may challenge sustainable development by straining the limited regulatory resources in these economies. Another pertinent study F. Ajide (2023) assesses the impact of AML regulations on entrepreneurship in Africa. The findings suggest that while AML measures are critical for ensuring a clean financial system, they can also create barriers for new entrepreneurs who face higher compliance costs and bureaucratic hurdles.

Amjad et al. (2021) focus on the interaction between money laundering and institutional quality in developing countries. Their research underscores that stronger institutions are vital for effectively enforcing AML regulations, which supports overall economic stability. Brandt (2023) comprehensively reviews methods for studying illicit financial flows and their effects on developing countries. The study highlights the complexity of quantifying these flows and underscores the need for robust methodologies to accurately assess their economic impact. Slama and Gueddari (2022) investigate the economic implications of money laundering in the MENA region using a simultaneous equation model. Their findings underscore the adverse impact of money laundering on economic growth, underscoring the need for robust AML policies in the region.

The reviewed literature collectively illustrates the critical role of AML regulations in shaping the economic landscapes of developing economies. While AML measures are essential for preventing financial crimes and enhancing economic stability, they also present trade-offs that may impact economic growth, entrepreneurship, and sustainable development. Effective policymaking will require striking a balance among these aspects to optimize the benefits of AML regulations while minimizing their drawbacks. Significant research underscores the correlation between economic indicators and money laundering. This study broadens this perspective by incorporating international finance and trade theories, such as the imperfect markets theory, which explains how market imperfections and asymmetric information facilitate money laundering. Additionally, we explore economic crime theories, such as the routine activity theory, to elucidate the relationship between economic activities, corruption control, and the incidence of money laundering. These theories are crucial for understanding the nuanced dynamics within our selected economic blocs.

3. Theoretical Framework

Money laundering is primarily recognized as a financial crime, but its ramifications extend deep into the macroeconomic fabric of nations, influencing economic stability and governance. This section outlines the theoretical connections between money laundering and key economic indicators, providing a robust framework for the subsequent empirical analysis. By integrating established economic theories with contemporary research findings, this study examines the nuanced effects of money laundering across various economic contexts.

3.1. Economic Crime Theory

Money laundering involves incorporating illicit funds into the legitimate economy, distorting economic indicators, and leading to misleading policy decisions. The concept of economic crime posits that financial offenses, including money laundering, are not solely the result of individual criminal acts but are intricately linked to the overall macroeconomic environment, which either enables or discourages such practices. Based on this theoretical standpoint, macroeconomic stability, as exemplified by GDP growth, might unintentionally hide the inherent dangers posed by money laundering operations. Therefore, governments and regulatory bodies must establish robust frameworks and stringent measures to combat money laundering effectively. These measures should include enhanced due diligence procedures, thorough monitoring of financial transactions, cooperation among international law enforcement agencies, and public awareness campaigns that highlight the consequences of engaging in money laundering. By implementing comprehensive and proactive strategies, countries can work toward eliminating the vulnerabilities that allow money laundering to thrive, safeguarding the integrity of their financial systems, and promoting a fair and transparent global economic environment (AlQudah et al., 2022). Economic crime theory suggests that macroeconomic stability may inadvertently conceal vulnerabilities that are exploited by illicit financial flows, thereby justifying the hypothesis that GDP growth increases the risk of money laundering in weakly regulated nations.

3.2. Financial Stability and Investment Theory

According to established theories on financial stability, foreign direct investment (FDI) has long been regarded as a reliable and robust indicator of an economy’s attractiveness and strength. It is crucial in promoting economic growth, advancing technology, and creating job opportunities. However, it is essential to recognize that the existence of money laundering in an economy can significantly undermine the credibility and reliability of this perception, potentially resulting in increased volatility and irreparable damage to reputation. Given these considerations, the goal of this study is to use the aforementioned theoretical framework to propose an intriguing hypothesis. The hypothesis suggests that while foreign direct investment (FDI) undoubtedly brings numerous benefits and opportunities to a nation’s economy, it is not immune to the destabilizing effects of money laundering. By exploring this uncharted territory, the researchers aim to shed light on the complex relationship between foreign direct investment (FDI) and money laundering and uncover the potential consequences of this intricate interplay. Researchers Barone et al. (2018) conducted extensive analyses, utilizing empirical evidence, case studies, and theoretical perspectives to support this hypothesis. Their thorough investigations aim to comprehensively understand the vulnerabilities FDI faces when exposed to a widespread money-laundering network. By unraveling the various dynamics at play, these scholars seek to provide policymakers, financial institutions, and governments with valuable insights to strengthen their anti-money-laundering measures and safeguard the stability and attractiveness of their economies.

In conclusion, while FDI has long been praised as a crucial measure of economic well-being and stability, it is essential to acknowledge the potential risks posed by money laundering. This expanded text reminds us that even the most substantial economic forces can be susceptible to destabilization without proper measures to combat money laundering. Therefore, by recognizing and addressing the connections between FDI and money laundering, societies can strengthen their economies, preserve their reputations, and ensure long-term prosperity (Ofoeda et al., 2022a).

3.3. International Trade Theory

Trade openness is frequently championed for economic growth; however, it also presents opportunities for money laundering through large-scale trade-invoicing practices. Drawing on international trade theory, which emphasizes the efficiency and risks of open trade systems, this hypothesis examines how trade openness may be correlated with increased opportunities for money laundering, thereby affecting the transparency and integrity of financial transactions.

An additional and relevant aspect of trade worth noting is captured by one of the Corruption Perceptions Index’s variables, namely, trade transparency. According to the Institute for Liberty and Democracy, openness in trade activities enables the economy to engage in global competition and promotes economic growth. Therefore, the latter essentially acts to reduce money laundering activities. Stylized facts also support this claim, as exemplified by the case of the BRICS countries (comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which are known for their emerging market economies and relatively high levels of corruption and money laundering. A Baker McKenzie and the Economist Intelligence Unit report shows that China is placed in the lowest position for transparency and that, according to Chinese authorities, annual losses in 2014 due to money laundering amounted to between USD 975 billion and USD 1.3 trillion (Qian et al., 2020).

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), trade openness is an index of the degree to which an economy participates in international trade over time. According to previous research, a high propensity to trade increases the likelihood of money laundering activities. According to García-Pérez (2023), for example, with all other factors remaining constant, a one percent increase in trade leads to a little more than half a percent increase in total financial transactions. Some positive impacts of trade openness on money laundering can be expected from tenants of the so-called Piketty hypothesis. According to this, if r > g, where r is the annual return to wealth and g is the nation’s economic growth, as Piketty stated at the beginning of the 21st century, current policy measures should emphasize international monetary and fiscal cooperation, promotion of entrepreneurship, and globalization. To prevent loss of wealth, rich people are likely to use money laundering to avoid tax payments to a fiscal authority. When this hypothesis of Piketty’s is applied to the context of the present research, the findings presented in the first paragraph could indicate that multinational companies, according to Uhlenbruck et al. (2006), may be significant money laundering channels, acting in harmony in countries with higher turnover (Piketty’s r is high for rich people) and in-symmetry. International trade theory emphasizes how trade openness fosters transparency and economic growth, supporting the hypothesis that trade openness reduces money laundering risks in regions with strong governance.

3.4. Socioeconomic Theory

Generally, money laundering occurs when the proceeds of crime are laundered in international or transnational flows, which are subject to differences in the financial systems of the countries involved. Banks in low- and middle-income countries imitate the success of financial innovations in high-income countries. They also face high degrees of competition in their pursuit of survival and are, thus, prone to higher risks than those operating in high-income countries. Size also explains the variation in money laundering risk across income categories. Large volumes of transactions increase banks’ regulatory costs and pose risks. A highly speculative sector is typically associated with high-income countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom. Regulatory costs increase with the volume of non-core activities in which funds circulate. Therefore, the United Nations’ International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) uses measures of trading volume as the third indicator of money laundering risk. According to Issac and Gureje (2009), low- and middle-income countries are more susceptible to politically exposed transactions because of the level of corruption due to the weak structures and, therefore, higher risk levels in these countries, since weak structures silently boost the risk of money laundering by corrupt officials (Sultan & Mohamed, 2023).

3.5. Governance and Corruption Theory

The interplay between corruption and money laundering is extensively documented. Governance theories highlight how weak institutional frameworks facilitate more extensive corruption and, by extension, easier money laundering. This perspective aligns with Acemoglu and Robinson’s (2012) institutional theory, which argues that extractive political and economic institutions foster corruption and hinder development. Their findings emphasize that nations with inclusive institutions can more effectively resist illicit financial flows, including money laundering. This study hypothesizes that more robust governance mechanisms, particularly those that control corruption, are crucial in mitigating the risks associated with money laundering.

Fisman and Svensson (2007) stated that financial secrecy allows citizens from less transparent countries to hide their savings from their governments and argued that there should be a relationship between capital flight and financial secrecy. Most researchers studying capital flight and money laundering turn to the Index of Economic Freedom or cross-sectional quantitative analysis by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) for a list of countries. R. K. Goel and Saunoris (2022) concluded that countries that are well governed have fewer illicit financial flows as a share of GDP. The correlation is robust to changes in the Index of Economic Freedom. Davidson and Judah (2023) found that external threats, such as terrorism and political violence, are positively associated with money laundering. Fries concluded that better governance practices result in lower illicit financial flows.

The theoretical frameworks applied herein are integral to understanding the complex dynamics between money laundering and macroeconomic indicators. By empirically testing these well-founded hypotheses, this study aims to provide meaningful insights into the economic implications of money laundering, thereby informing both policy formulation and academic discourse on financial crime and governance. Governance theories demonstrate how robust institutional frameworks limit corruption and illicit financial flows, aligning with the hypothesis that corruption control is negatively associated with money laundering risk.

4. Methodology

This study uses annual data from the Basel Institute on Governance and World Bank statistics for the European Union (EU), G20, BRICS, and CIVETS countries. Because the Anti-Money-Laundering Index, the primary variable, has only been available since 2012, the study period was considered to span from 2012 to 2021. The EU group of nations includes Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Republic of Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. The members of the G20 are Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Similarly, EU member countries are excluded from the G20 group and treated separately. Brazil, the Russian Federation, China, India, and South Africa are collectively known as the BRICS countries. The CIVETS countries are Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa. As can be seen, several countries hold formal membership in multiple economic alliances. Several countries, including Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, hold membership in both the BRICS and the G20. In this study, we intentionally allow for such overlaps. Countries are included in each group according to their formal membership to explore the internal dynamics of each bloc, rather than compare them directly. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of how money laundering risks behave within each economic alliance, acknowledging that some countries are part of more than one bloc.

Using panel-corrected standard error models, our research methodology is tailored to dissect the nuanced relationships between trade openness, foreign direct investment, governance measures, and their collective impact on money laundering within selected economic blocs. The use of the PCSE estimator was chosen to address the heteroskedasticity and cross-sectional dependencies observed in the dataset, ensuring robust and unbiased estimations of the relationships among variables. This study analyzes a decade-long dataset from the Basel Institute on Governance, the World Bank, and other publicly available sources, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Transparency International, and the World Economic Forum. Our approach enables a robust examination of both cross-sectional and time-series data, providing comprehensive and comparative insights. This fills the gap in longitudinal and cross-regional studies, thereby enhancing our understanding of the effectiveness of various controls in mitigating money laundering risks.

4.1. Variables: Operational Definitions

The Basel Institute of Governance developed the Anti-Money-Laundering Index, which measures the risk of money laundering. Our empirical analysis uses real GDP growth, FDI net inflows, trade openness, corruption control, and the country’s income category as explanatory variables. Table 1 below lists the study variables, their abbreviations, definitions from the variable source, and the measurement scales.

Table 1.

Variables of the study.

This study focuses on critical, independent variables—real GDP growth, FDI net inflows, trade openness, control of corruption, and a country’s income category—based on their direct theoretical relevance and established empirical linkages with the risk of money laundering. While these variables are robust predictors within the scope of the analysis, the model does not account for other potentially significant factors, such as political stability, cultural influences, or institutional quality, which may also affect money laundering risks.

The decision to exclude these variables is based on two considerations. First, the scope of this research prioritizes economic openness and governance variables, which are central to the study’s objective of examining their interplay with the risk of money laundering. Second, data availability and consistency across the study’s time frame (2012–2021) and selected economic blocs (EU, G20, BRICS, and CIVETS) limited the inclusion of certain variables, such as cultural factors, for which comparable longitudinal data are not uniformly available.

Table 2 presents the variations across the groups in terms of trade, FDI inflows, economic growth, the anti-corruption index, and the risk of money laundering. The European Union group was examined separately due to its favorable performance in all other categories, except economic growth. The EU group had the lowest average risk of money laundering (4.4), while the BRICS and CIVETS groups had the most significant moderate risks (5.6). From 2012 to 2021, the real GDP growth rate of both the EU and G20 was 2.1%, whereas the economies of the BRICS and CIVETS experienced growth rates of 3.9% and 3%, respectively. The EU reported positive figures, with the most significant trade and net FDI influx rates, as well as a higher degree of anti-corruption initiatives. The G20 saw the lowest average net inflows of FDI, while the BRICS saw the lowest levels of trade and corruption control.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

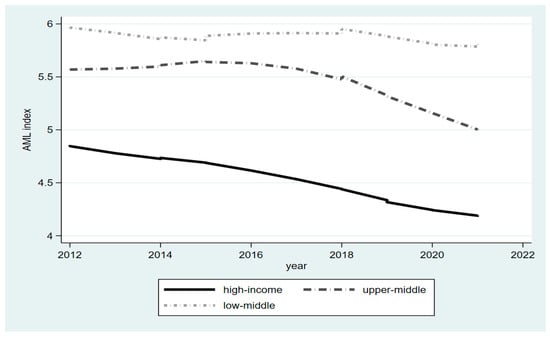

Figure 1 plots the mean money-laundering-risk index by income category throughout the studied period. It demonstrates that, compared to high-income and middle-income nations, lower-middle-income countries faced a higher risk of money laundering. While high-income nations kept lowering the risk of money laundering, upper-middle-income nations adopted a similar stance after 2016. These patterns suggest that money-laundering incentives are more alluring in low- and middle-income nations.

Figure 1.

Money-Laundering Risk Index by income category. Source: created by the authors based on the collected dataset.

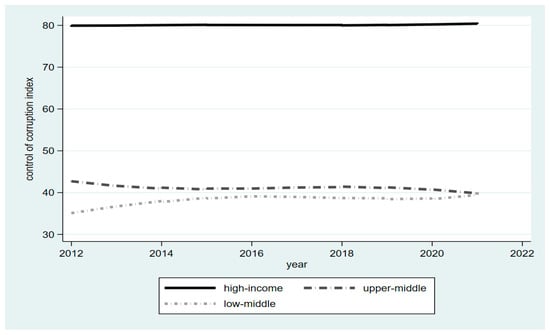

Figure 2 displays the corruption index control. As expected, high-income countries have a high ranking of anti-corruption measures. Although upper-middle countries have more stringent anti-corruption policies than lower-middle-class ones, they are cutting back on anti-corruption efforts. In contrast, low- and middle-income countries are strengthening their anti-corruption measures over the study period. The danger of money laundering is most significant in upper-middle-income countries, as illustrated in Figure 1 above, which can be attributed to these patterns of corruption control efforts.

Figure 2.

Control of corruption index by income category. Source: created by the authors based on the collected dataset.

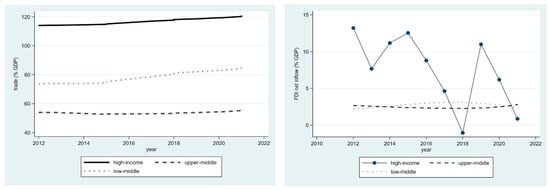

The economic openness indices, trade, and FDI net inflows are expressed as a percentage of GDP by income category, as shown in Figure 3. Trade is expanding in lower-middle-class and high-income countries, with a notable disparity between the two groups (trade is approximately 40 percentage points more in the high-income group). In contrast, trade in upper-middle-income countries remained steady at around 55%, with a minor increase after 2018. Conversely, high-income countries are seeing some sharp fluctuations in the net foreign direct investment inflows. While FDI inflows into upper-middle-income countries remained relatively constant at roughly 3%, they increased in lower-middle-income countries between 2012 and 2018 before declining.

Figure 3.

Economic openness (trade and FDI) by income category. Source: created by the authors using the collected dataset.

4.2. Diagnostic Tests

The outcomes of the multicollinearity test among the independent variables, the Pesaran (2004) test for cross-sectional dependency, the likelihood ratio test for heteroscedasticity, and the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in the panel data are shown in Table 3 and Table 4. The matrix in Table 3 displays low-correlation values, indicating no concerns about a perfect linear relationship among the independent variables, as none of the coefficients in Table 3 are close to −1 or +1. Given the p-values in Table 4, the null hypothesis of the cross-country independence is rejected based on the panel independence test, from Pesaran (2015), and, thus, cross-country reliance is concluded. Table 5 presents the likelihood ratio test results, which reject the hypothesis of homoscedastic errors and indicate the presence of heteroscedasticity in the residuals. Meanwhile, the Wooldridge test indicates the presence of serial correlation among the variables.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation matrix—multicollinearity test.

Table 4.

Pesaran test for cross-sectional (country) dependence.

Table 5.

Heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation test.

While we report the Wooldridge autocorrelation test for the full sample model, all group-specific models share the same panel structure and time dimension. Given this structural consistency, we infer that autocorrelation exists across all models. Therefore, the decision to use panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) and feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) remains valid and consistent across subsamples.

4.3. Model

In the presence of heteroscedasticity and serial correlation, fixed-effects estimates may have biased standard errors, which can affect statistical inference (Huang et al., 2018). The panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) and feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) serve as potential substitutes (Beck & Katz, 1995; Prais & Winsten, 1954). The PCSE calculate adjusted estimates for linear cross-sectional time-series models where the parameters are estimated using either OLS or Prais–Winsten regression. When computing the standard errors and the variance–covariance estimates, the PCSE assume that the disturbances are heteroskedastic and contemporaneously correlated across panels. Based on our diagnostics, we examine the influence of our explanatory variables on money laundering risk using PCSE when N > T (the number of panels exceeds the number of periods) and the FGLS model when N < T.

The Basel Institute of Governance defines money laundering as the process by which criminals and other illicit actors conceal the proceeds of their illegal activities, making them appear to originate from legitimate sources. Trade openness and net foreign direct investment inflows are introduced as independent variables because they facilitate the flow of money across borders. Due to the strong correlations among governance indicators, such as accountability, rule of law, regulatory quality, and corruption control, the corruption control index is included in the model as a proxy for national institutions and governance. The percentile rank of a nation indicates how it compares to other countries in the aggregate assessment; a score of 0 signifies it is highly corrupt, while a rank of 100 suggests it is entirely clean. The World Bank states that indicators of economic performance and size include economic growth and a country’s income distribution. Therefore, real GDP growth and the country’s income category are also incorporated into our model. The model is expressed as follows:

where is the money-laundering index for country (i) in the year (t); is a vector of independent variables, including real GDP growth, FDI net inflows, trade openness, control of corruption, and the country’s income category; is a constant term; is a vector of parameters that estimate the effects of j regressors on the dependent variable AML; and is the error term.

5. Results

Table 6 displays the regression results in eight columns, as follows: column 1 shows the full sample’s results; columns 2, 3, and 4 (Table 6a) display the results by a nation’s income category, while columns 5 through 8, in panel b of the table, show the results for each economic bloc. The entire sample’s results show that economic growth was a poor indicator of the risk of money laundering, while FDI inflows increased it. Promoting trade and fighting related risks reduced the risk of money laundering. The risk of money laundering was inversely related to income level, making the income category a powerful predictor of money laundering. Relative to high-income nations, the danger of money laundering was estimated to be 0.56 points higher in upper-middle-income nations and 0.96 points higher in lower-middle-income nations. These notable variations in wealth categories imply that money laundering was more common in the world’s poorest countries.

Table 6.

(a) AML regression by income category; (b) AML regression by economic bloc.

Estimating the regression by income category reveals that economic growth is a statistically insignificant indicator of money laundering risk in high-income nations. However, it increased risk in both blocs of middle-income nations. Net inflows of FDI exhibited varying effects, increasing the risk of money laundering in high-income countries and decreasing the risk in the upper-middle-income group. However, this effect was insignificant in the case of lower-middle-income countries. These varying effects of economic growth and FDI inflows may be linked to the similarities and variability in the financial performance and institutional structures of countries within classes. For example, economic growth promoted money laundering behaviors in middle-income countries. At the same time, it did not in wealthy nations, as institutions and regulations are expected to be more stringent in these rich countries. Trade openness and anti-corruption measures reduced the risk of money laundering in high-income and upper-middle-income countries. However, trade increased the risk of money laundering in low- and middle-income nations, while the anti-corruption measures are still not mature enough in these poorer nations.

Since there was insufficient variability in the country’s income classification in the group-specific regressions, the income category variable (high-income, upper-middle income, and lower-middle income) was excluded from the analysis. Group-specific results are presented in Table 6b. While economic growth was a negligible indicator of the danger of money laundering in the EU, it was a significant indicator of risk in the G20, BRICS, and CIVETS groups. The volume of trade and FDI inflows raised the risk of money laundering in the EU, whereas they had the opposite effect on the risk of money laundering in the remaining groups. FDI inflows in the G20 countries were statistically negligible, but the negative sign indicates a potential inverse impact on money laundering risk. Money laundering and the fight against corruption had a consistent negative relationship across groups; when additional measures reduced corruption, the risk of money laundering also decreased.

The findings of this study shed new light on the differential impacts of economic policies and governance structures on money laundering risks within the European Union (EU), the G20, the BRICS, and the CIVETS. Unlike prior studies that have provided general overviews, our focused analysis reveals that trade openness and foreign direct investment have complex, varied impacts on money laundering depending on each bloc’s specific governance frameworks and economic conditions. For instance, our results demonstrate that while FDI inflows generally increase money laundering risks, robust governance can significantly mitigate these risks, a nuance that needs to be comprehensively addressed in the existing literature.

5.1. Response Analysis

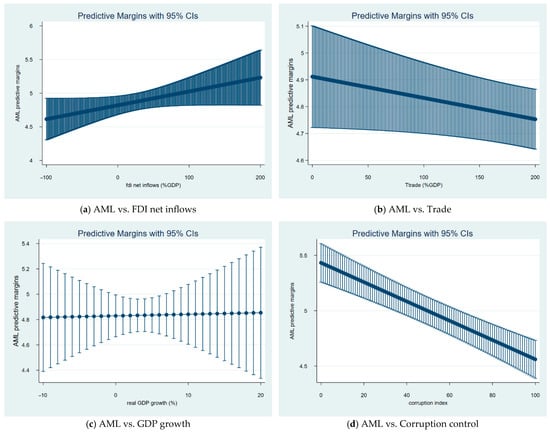

This section provides a predictive analysis of how the explanatory variables—trade, economic growth, FDI net inflows, and corruption control—will affect the money-laundering index. Panels (a) through (d) of Figure 4 show the predictive margins (at a 95% confidence level) of the AML Index to a range of values that have been postulated for each explanatory variable based on the actual min–max values of the variables in this study.

Figure 4.

AML response to GDP growth, trade, FDI, and corruption control (predictive margins). Source: created by the authors using the collected dataset.

As shown in panel (a), for values of FDI net inflow ranging between [−100, 200] as a percentage of GDP, the AML Index is expected to climb with an increasing variance at large magnitudes of inflows. When trade size increases from 0 to 200% of GDP, the risk of money laundering seems to be mitigated, and as the trade size increases, so does the variability of these expectations. The AML Index’s values are expected to rise modestly, within a range of −10% to 20%, in response to economic growth. The variability is more significant at higher growth magnitudes, and it is lowest when growth ranges from 3% to 8%. Lastly, more substantial efforts to combat corruption are anticipated to influence the risk of money laundering significantly; the AML shows a significantly declining response for the anti-corruption index throughout a range of [0, 100].

Comparison with Prior Studies

Our findings align with prior studies that emphasize the role of governance quality and economic openness in shaping money laundering risks. For example, Ofoeda et al. (2022b) found that while anti-money-laundering (AML) regulations enhance financial sector credibility, they may constrain investment in less-developed economies—a nuance also reflected in our results for middle-income countries. Similarly, Amjad et al. (2021) emphasize the necessity of a strong institutional quality for effective AML implementation, which is consistent with our finding that control of corruption significantly reduces money laundering risks across all blocs.

Mohd-Rashid et al. (2023) also highlight the inverse relationship between corruption control and financial crime, a relationship we confirm empirically in both bloc-level and income-based models. In contrast, García-Pérez (2023) reported a more linear association between trade openness and reduced financial crime. Our findings suggest this relationship is more nuanced, with trade openness reducing laundering risk primarily in countries with robust governance systems.

These comparisons reinforce the broader applicability of our empirical conclusions and support policy recommendations that emphasize governance quality and differentiated AML strategies across economic contexts.

5.2. Policy Implications

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature on money laundering, managerial practices, and public policy, particularly within the context of economic blocs such as the European Union (EU), the G20, the BRICS, and the CIVETS. First, academically, it enhances our understanding of the complex interplay between economic openness, governance quality, and money laundering risks. Unlike previous studies, this research provides a comparative analysis by income classification and across diverse economic blocs, highlighting how variations in financial and governance structures influence the effectiveness of anti-money-laundering (AML) strategies. This adds depth to the existing literature by illustrating the differential impacts of similar policies in different economic contexts.

Second, from a managerial perspective, this study’s findings offer valuable insights into corporate governance and risk management within multinational corporations operating across these blocs. The detailed analysis of how trade openness and foreign direct investment influence money laundering risk provides critical information that can aid in refining corporate strategies to mitigate such risks. This study suggests that companies operating across diverse economic blocs should consider regional variations in governance and economic openness when developing compliance strategies, as these factors significantly influence the effectiveness of anti-money-laundering measures.

Third, this paper makes substantial contributions to public policy. This research informs policymakers about the reforms most likely to succeed in their respective economic blocs by identifying specific governance measures that effectively reduce money laundering risks. For instance, our findings highlight the critical role of robust legal systems and transparent control of corruption measures in mitigating the risks associated with high levels of foreign direct investment and trade openness. This study advocates for targeted policy interventions that are responsive to economic conditions and adaptive to the evolving tactics of money launderers.

Furthermore, this research contributes to the ongoing dialogue among international regulatory bodies, providing empirical evidence that supports the need for enhanced international cooperation in combating money laundering. The comparative nature of the study highlights the need for a coordinated global approach to AML regulation, particularly in a world where economic activities are becoming increasingly cross-border and interconnected.

The impact of FDI on money laundering risk varies across different income categories. In middle- and low-income countries, where financial systems may lack robust anti-money-laundering (AML) mechanisms, FDI provides a channel for illicit actors to integrate illegal funds. Conversely, in high-income countries, stringent governance may mitigate these risks, although gaps in sectoral oversight can still be exploited. This finding underscores the need for targeted foreign-direct-investment (FDI) screening policies to prevent illicit financial flows.

To mitigate the money laundering risks associated with foreign direct investment (FDI), policymakers should prioritize implementing enhanced due diligence measures for cross-border investments. These include rigorous verification of the source of funds, stricter enforcement of beneficial ownership transparency, and international cooperation to monitor high-risk sectors. Strengthening these safeguards can ensure that FDI contributes to economic development without being misused for illicit purposes.

In conclusion, this study’s contributions extend beyond its methodological rigor and comprehensive data analysis, offering substantial implications for academia, industry, and policymaking. By bridging the gap between theoretical research and practical, actionable strategies, this paper serves as a valuable resource for enhancing the effectiveness of AML measures globally.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the relationship between economic openness, governance, and money laundering risk in the EU, G20, BRICS, and CIVETS blocs from 2012 to 2021. Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows increase the risk of money laundering, despite being vital for many economies. However, measures to enhance trade liberalization and step up anti-corruption campaigns have reduced this risk. Interestingly, the risk of money laundering varies with income; countries with low- to middle-income levels tend to be the most at risk, while those with higher incomes appear to be more protected.

The complicated nature of these interactions is highlighted by the differences in the relationship between economic growth and money-laundering susceptibility among various groupings, particularly its substantial impact in the G20, BRICS, and CIVETS groups, as opposed to its minor effect within the EU. The unquestionable importance of governance is the recurring theme among these organizations. Robust control of corruption and strict anti-corruption measures, hallmarks of solid governance, are crucial in the fight against money laundering. The study conclusively highlights the imperative for tailored anti-money-laundering strategies, considering the different economic and regulatory peculiarities of various global blocs. As economic landscapes evolve, so too must our approaches to combating money laundering, ensuring that they are responsive to both the challenges presented by economic development and the opportunities for regulatory innovation. Future research should continue to explore these relationships, focusing on integrating more granular data and evolving economic theories to keep pace with the dynamic nature of global finance.

The predictive response analysis provides a detailed view of how our variables affect the likelihood of money laundering. To anticipate and reduce such risks, policymakers and stakeholders must integrate these insights into their strategic frameworks. Region-specific measures are urgently needed, because economic growth affects various groups differently in terms of money laundering. Instead of using a one-size-fits-all approach, policymakers should develop anti-money-laundering plans that take into account the unique challenges and circumstances of each region.

Nations must exercise caution even as they enthusiastically support trade openness and FDI as the cornerstones of economic progress. Stringent controls and transparency measures should accompany economic openness policies to prevent them from unintentionally serving as a channel for money laundering. The ongoing unfavorable correlation between anti-corruption measures and money laundering underscores the imperative to strengthen them. Investing in systems, technology, and training that detect and discourage corruption becomes essential, especially for low- and middle-income countries. Due to their marked vulnerability, low- and middle-income countries require increased international cooperation. Rich countries and international organizations can play crucial roles in helping these more vulnerable countries strengthen their anti-money-laundering defenses by exchanging technical expertise, resources, and best practices.

Policymakers must adopt region-specific AML measures. High-income countries should protect FDI inflows. They should enhance transparency and check cross-border transactions. Middle-income countries, particularly those with weak institutions, should prioritize anti-corruption and governance reforms. Low- and middle-income countries are vulnerable to money laundering. They require international cooperation and resource sharing to enhance their regulations.

Also, trade liberalization and open-economy policies must be strictly controlled to prevent their misuse for illicit financial flows. Investing in e-governance and capacity building can boost resilience to money laundering. Finally, public awareness campaigns are vital; they mobilize support to fight financial crimes.

This study’s analysis offers valuable insights for academia, industry, and policymakers, who can utilize it to enhance global AML strategies. Future research should explore additional variables, such as political stability and culture. This could help us better understand the causes of money laundering risk. Stakeholders can utilize these findings to enhance defenses against money laundering, thereby promoting global economic stability and sustainable development.

Ultimately, the public needs to be more aware of the dangers associated with money laundering. Knowledge of the complexities of money laundering can empower the public to become a powerful partner in the fight against these illicit acts. Governments and organizations should support public education initiatives that inform the public and companies about common money laundering tactics and how to report suspicious activities. Ultimately, governments must stay one step ahead in this dynamic environment, where money launderers continually innovate and adapt. Their commitment to regular reviews ensures the’ potency, relevance, and alignment of their anti-money-laundering policies with new threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and M.H.; methodology, A.A.; software, A.A.; validation, A.A., M.H. and D.S.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A.; resources, A.A.; data curation, A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration A.A.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements and privacy restrictions. However, they may be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D., & Verdier, T. (2000). The choice between market failures and corruption. American Economic Review, 90(1), 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, F. (2023). Anti-money laundering regulations and entrepreneurship: The case of Africa. In Concepts and cases of illicit finance (pp. 61–82). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Ajide, F. M., & Ojeyinka, T. A. (2023). Benefit or burden? An exploratory analysis of the impact of anti-money laundering regulations on sustainable development in developing economies. Sustainable Development, 32(3), 2417–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Raza, S. A., Puah, C. H., & Arsalan, T. (2021). Does e-government control corruption? Evidence from South Asian countries. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(1), 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qudah, A. (2024). Unveiling the shadow economy: A comprehensive review of corruption dynamics and countermeasures. Kurdish Studies, 12(2), 4768–4784. [Google Scholar]

- AlQudah, A., Bani-Mustafa, A., Nimer, K., Alqudah, A. D., & AboElsoud, M. E. (2022). The effects of public governance and national culture on money laundering: A structured equation modeling approach. Journal of Public Affairs, 22, e2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qudah, A., & Hailat, M. A. (2025). Deciphering the links: Evaluating central bank transparency impact on corruption perception index in G20 countries. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 28(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qudah, A. M., Al-haddad, L., & Aljabali, A. A. (2025). Combatting medical corruption: A global review of root causes, consequences, and evidence-based interventions. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies, 8(2), 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M. M., Arshed, N., & Anwar, M. A. (2021). Money laundering and institutional quality: The case of developing countries. In Money laundering and terrorism financing in global financial systems (pp. 91–107). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, R., Delle Side, D., & Masciandaro, D. (2018). Drug trafficking, money laundering and the business cycle: Does secular stagnation include crime? Metroeconomica, 69(2), 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, K. (2023). Illicit financial flows and developing countries: A review of methods and evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37(3), 789–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimira, H. (2021). An exploration of the current regulatory aspects of money laundering in South Africa. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 24(4), 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C., & Judah, B. (2023). How financial secrecy undermines democracy. Journal of Democracy, 34(4), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defossez, D. (2017). The current challenges of money laundering law in Russia. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 20(4), 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R., & Svensson, J. (2007). Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 83(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, R. (2023). Some certainties and some uncertainties in European Union trade mark law. GRUR International, 72(11), 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R. K., & Saunoris, J. W. (2022). Foreign direct investment (FDI): Friend or foe of non-innovating firms? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47(4), 1162–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S. (2022). Money laundering or foreign contribution! The spirit of governance in NGOs of India. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 25(2), 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriyetty, N., & Grewal, B. S. (2017). Macroeconomics of money laundering: Effects and measurements. Journal of Financial Crime, 24(1), 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Liu, Q., Cai, X., Hao, Y., & Lei, H. (2018). The effect of technological factors on China’s carbon intensity: New evidence from a panel threshold model. Energy Policy, 115, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M., & Gureje, O. (2009). Low-and middle-income countries. In L. Gask, H. Lester, T. Kendrick, & R. Peveler (Eds.), Primary care mental health (pp. 72–87). RCPsych Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kurum, E. (2023). RegTech solutions and AML compliance: What future for financial crime? Journal of Financial Crime, 30(3), 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Atuahene-Gima, K. (2018). Enhancing product innovation performance in a dysfunctional competitive environment: The roles of competitive strategies and market-based assets. Industrial Marketing Management, 73, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magableh, S., Hailat, M., Al-qalawi, U., & Al Qudah, A. (2024). Corruption suppression and domestic investment of emerging economies: BRICS and CIVETS groups–panel ARDL approach. Journal of Financial Crime, 31(1), 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciandaro, D. (2017). Global financial crime: Terrorism, money laundering and offshore centres. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Masciandaro, D., & Romelli, D. (2015). Ups and downs of central bank independence from the Great Inflation to the Great Recession: Theory, institutions and empirics. Financial History Review, 22(3), 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Rashid, R., Mehmood, W., Ooi, C.-A., Che Man, S. Z., & Ong, C. Z. (2023). Strengthened rule of law to reduce corruption: Evidence from Asia-Pacific countries. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 26(5), 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoeda, I., Agbloyor, E. K., & Abor, J. Y. (2022a). How do anti-money laundering systems affect FDI flows across the globe? Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2058735. [Google Scholar]

- Ofoeda, I., Agbloyor, E. K., Abor, J. Y., & Osei, K. A. (2022b). Anti-money laundering regulations and financial sector development. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(4), 4085–4104. [Google Scholar]

- Orlova, A. V. (2008). Russia’s anti-money laundering regime: Law enforcement tool or instrument of domestic control? Journal of Money Laundering Control, 11(3), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Cambridge Working Papers. Economics, 1240(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H. (2015). Testing weak cross-sectional dependence in large panels. Econometric Reviews, 34(6–10), 1089–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, H. (2008). The measures on combating money laundering and terrorism financing in the PRC: From the perspective of financial action task force. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 11(4), 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prais, S., & Winsten, C. (1954). Trend estimators and serial correlation, cowles commission monograph, no. 23. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J., Wu, W., Yu, Q., Ruiz-Garcia, L., Xiang, Y., Jiang, L., Shi, Y., Duan, Y., & Yang, P. (2020). Filling the trust gap of food safety in food trade between the EU and China: An interconnected conceptual traceability framework based on blockchain. Food and Energy Security, 9(4), e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S. (2017). Factors influencing perceptions on corruption in public service delivery via e-government platform. Foresight, 19(6), 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, G. L. (2022). The Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the EU Anti-Money Laundering framework compared: Governance, rules, challenges and opportunities. Journal of Banking Regulation, 23(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sham, A. (2006). Money laundering laws and regulations: China and Hong Kong. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 9(4), 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. (2020). Independence and temporality: Examining the PMLA in India. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 23(1), 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprasad, S., & Mathew, S. (2021). Corporate governance practices and the pandemic crisis: UK evidence. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 21(6), 983–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, M. B., & Gueddari, A. (2022). The relationship between money laundering and economic growth in the MENA region—A simultaneous equation model. In Key challenges and policy reforms in the MENA region: An economic perspective (pp. 123–141). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, N., & Mohamed, N. (2023). Challenges faced by financial institutes before onboarding politically exposed persons in undocumented Eastern economies: A case study of Pakistan. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 26(3), 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenbruck, K., Rodriguez, P., Doh, J., & Eden, L. (2006). The impact of corruption on entry strategy: Evidence from telecommunication projects in emerging economies. Organization Science, 17(3), 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).