Abstract

Since 2019, Togo has been strengthening financial decentralization through municipalization and the election of municipal councilors. Municipal financial autonomy is a key driver of local governance, allowing municipalities to mobilize their own resources, manage tax and non-tax revenues, and implement development projects. However, despite a legal framework governing local taxation, Togolese municipalities continue to face chronic financial constraints that limit their ability to finance public services and infrastructure. This study examines the mechanisms of financial decentralization in Togo and their contribution to municipal budgets. Using a quantitative approach that combines documentary analysis and interviews with 188 experts and practitioners in local finance, the study identifies the following four primary financing mechanisms: local, national, community-based and international. Among these, own revenues, including tax revenues, non-tax revenues, and revenues from the provision of services, together with government transfers through the Local Authorities Support Fund (FACT) are the main sources of local government finance. However, the results show that several legally defined fiscal instruments remain underutilized or outdated in many municipalities, significantly limiting their effectiveness in mobilizing resources. These results highlight the need to optimize fiscal decentralization strategies in order to strengthen the financial autonomy of municipalities and support sustainable territorial development.

1. Introduction

Decentralization is a governance process that involves transferring fiscal, political, and administrative responsibilities from central governments to local or regional authorities. It is driven by various factors, including democratization, improved local governance, and the pursuit of sustainable development. In particular, decentralization is seen as a key strategy to reduce territorial inequalities, alleviate poverty, enhance local economic development, and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Local governments play a crucial role in providing infrastructure and public services, but their effectiveness largely depends on their financial capacity. This challenge is particularly acute in developing countries, where rapid urbanization coupled with limited local financial resources (Sondou et al., 2024), complicates the effective implementation of decentralization policies (Yatta, 2009).

In Africa, decentralization is often promoted as a means to strengthen democracy, improve public service delivery, and reduce regional disparities (Flan et al., 2022; Gomes Olamba, 2013; Tanoh, 2019). However, its success relies on robust and well-adapted financing mechanisms that ensure the financial autonomy of local governments while maintaining transparency and accountability in public finance management (Flan et al., 2022). Without sufficient financial resources, local authorities struggle to fulfill their responsibilities effectively, limiting the intended benefits of decentralization (Bahl & Martinez-Vazquez, 2006) Decentralization should be based primarily on the principle of transferring powers and resources from a central level to local authorities, which is an essential condition for guaranteeing their autonomy (Yatta, 2009). As Bahl and Martinez-Vazquez (2006) point out, insufficient financial resources can hinder the autonomy of local authorities and limit their ability to carry out their missions.

In sub-Saharan Africa, financing decentralization remains a major challenge due to weak local tax bases, heavy reliance on central government transfers, inefficient tax collection systems, and inadequate financial management practices (Gomes Olamba, 2013; Tanoh, 2019). The United Cities and Local Governments (UCLGs) organization emphasize that effective public financial management is a key pillar of sustainable local governance (CGLU, 2015). Yet, the financial resources available to local governments remain insufficient, exacerbating existing inequalities between urban and rural municipalities (Bahl, 1999). Larger cities often benefit from higher tax revenues and greater investment opportunities, whereas smaller municipalities face structural constraints that hinder their ability to finance development projects (Gomes Olamba, 2013). This highlights the importance of fiscal and budgetary decentralization in addressing these challenges. Fiscal decentralization, which consists of a partial transfer of national taxation to local authorities, allows the central government to delegate some of its administrative control over the financial sector to local authorities with the aim of stimulating economic growth (Zhu & Lu, 2022). This mechanism allows local authorities to mobilize various resources, such as government transfers (subsidies), local service provision, decentralized cooperation, and contributions from sub-regional organizations or technical and financial partners (Gourmel-Rouger, 2015). By encouraging a more targeted allocation of financial resources based on local information, fiscal decentralization could reduce the inequalities observed between different municipalities. However, weak local management capacity remains a major obstacle to the implementation of successful decentralization in sub-Saharan Africa (Awortwi, 2016; Smoke, 2013).

Like many West African countries, Togo faces challenges in financing decentralization, despite reforms since the 1990s. Local authorities struggle with weak fiscal resources and a heavy reliance on government transfers. Fiscal reforms and increased cooperation with international partners are needed to improve decentralization. Innovative financing mechanisms and capacity building strategies could help improve local financial management and promote sustainable local development. Although progress has been made, decentralization remains complex due to structural, financial, and institutional challenges. Despite the strengthening of the legal framework with Law No. 2007-011 and the creation of the Local Authorities Support Fund (FACT) in 2020, the financial autonomy of municipalities is limited by weak local fiscal resources, poor resource mobilization, and legal barriers to better management. Municipal financial management is often characterized by a low revenue collection capacity, a dependence on government transfers, and organizational challenges (Coquart, 2013; Flan et al., 2022; Tanoh, 2019). Municipal budgets remain small—only 2.94% of the national budget in 2021, 3.06% in 2022, and 2.89% in 2023—far below the WAEMU recommendation of 20% fiscal transfers to local authorities. These deficits and difficulties in mobilizing resources limit investment in local development and exacerbate territorial disparities. Despite efforts to promote decentralization, the effectiveness of financing mechanisms remains inadequate. Resources allocated to local authorities are insufficient and poorly distributed, limiting their ability to address local development needs. Improving the decentralization of financing mechanisms is therefore crucial to strengthening the financial autonomy of local authorities and promoting more equitable and sustainable development.

The issue of local authority financing raises a fundamental question: how can the financing mechanisms of decentralization be improved to strengthen the financial autonomy of local authorities and promote more equitable and sustainable local development? In response to this question, this study examines the financing mechanisms available to local authorities in Togo, assesses their effectiveness, and identifies the main challenges they face. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing a detailed analysis of the financing mechanisms used by local authorities in Togo, assessing their impact on financial autonomy and providing information on the financing mechanisms used by local authorities in Togo.

2. Literature Review

The issue of financing decentralization is a major challenge in developing countries as it determines the autonomy of local authorities and their ability to implement sustainable territorial development policies. The literature distinguishes several mechanisms for financing decentralization, classified according to their origin: municipal resources, government transfers, community financing, and international contributions (Bahl & Martinez-Vazquez, 2006; Smoke, 2013).

2.1. Financial Decentralization and Local Budget Autonomy

The theory of fiscal decentralization was largely developed by Oates (1972), who argued that decentralization allows for a more efficient allocation of resources by bringing budgetary decisions closer to local needs. This principle, known as ‘Oates’ decentralization theorem’, emphasizes the importance of local authorities in managing local public finances to meet people’s expectations. This idea is based on public choice theory, which suggests that local authorities, being closer to citizens, are better placed to respond effectively to their needs while reducing waste (Oates, 1972).

Financial decentralization rests on two fundamental pillars: fiscal decentralization and budgetary decentralization (Yatta, 2009). Fiscal decentralization involves the transfer of fiscal powers to local authorities, allowing them to levy taxes and manage a portion of public revenues. The second refers to the ability of local authorities to plan and implement their own budgets in accordance with available resources (Ebel & Yilmaz, 2002). Local governments must be able to raise funds autonomously and not rely solely on transfers from the central state (Ndamsa et al., 2022; Otoo & Danquah, 2021). This includes revenue sources such as local taxes, property taxes, market fees, and revenues from the exploitation of local natural resources. However, the management of local finances remains a challenge in many sub-Saharan African countries due to complex institutional, fiscal, and political factors (Holanda Figueiredo Alves et al., 2023; Ndamsa et al., 2022). Autonomy remains limited due to the low capacity of local governments to collect tax and non-tax revenues (Wang & Deng, 2023). Although decentralization can be a driver of local development, it is only effective if it is accompanied by a sound institutional framework with appropriate legal and administrative structures (Holtz & Ordu, 2021). This is why Ndamsa et al. (2022) insist on the need to strengthen institutional capacities and improve the regulatory framework in order to optimize the mobilization of local resources. Institutional reforms are crucial to ensure that local governments have the resources and skills to manage public finances effectively. Sow and Razafimahefa (2017) note that successful decentralization requires not only expenditure decentralization, but also revenue decentralization. In other words, successful fiscal decentralization also requires adequate administrative decentralization, i.e., the ability of local authorities to manage public services independently without excessive interference from the central state (Altunbas & Thornton, 2012).

2.2. Government Transfers: An Essential but Insufficient Lever?

According to Tiebout (1956), citizens choose where to live on the basis of the public services on offer. This implies that local authorities need to be competitive in order to attract and retain residents. This perspective justifies the importance of government transfers to redress territorial imbalances and ensure high-quality public services. In countries where local authorities’ own resources are limited, financial transfers from the state play a crucial role in financing decentralization. Oates (1972) argues that these transfers are essential in developing countries to correct fiscal inequalities between local authorities and to ensure a fair distribution of resources. They make it possible to correct fiscal imbalances between different local authorities (Tanoh, 2019). These transfers can take the form of operating grants, investment grants, or tax equalization (McLure & Martinez-Vazquez, 2011). In the West African context, the WAEMU recommends that government transfers to local authorities should represent at least 20% of the national budget, a threshold that is rarely reached in several countries, including Togo. However, the literature highlights several limitations of government transfers. Firstly, their irregularity and unpredictability make it difficult for local authorities to plan their budgets (Devas & Kelly, 2001). Secondly, these transfers are often insufficient to guarantee real financial autonomy for local authorities, forcing them to turn to other sources of funding (Bahl & Martinez-Vazquez, 2006). As pointed out by Gomes Olamba (2013), Tanoh (2019), and Ndamsa et al. (2022), excessive reliance on transfers can limit the autonomy of local authorities and hinder their development. Transfers are often subject to political and economic conditions, which can lead to delays or shortfalls in local government funding, particularly in developing countries. Ogunnubi (2022) argues that the dependence of local governments on the state puts them at the mercy of the state, which can deny any local government its right to funding. For example, in 2004, the Obasanjo federal government illegally withheld funds due to local governments in Lagos State (Taleat, 2017). Similarly, state governments have often abused their control over the joint account to interfere in local affairs (Doho et al., 2018). As a result, local governments often have to bend at the feet of states to protect their financial allocations (Doho et al., 2018). As Tanoh (2019) points out, central governments in West Africa often centrally control the management of local finances, which can hinder the effectiveness of these mechanisms.

2.3. Community and International Funding: Opportunities and Constraints

Community funding, particularly from sub-regional organizations such as the WAEMU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), aims to support local development through cooperation and investment programs. However, funding remains limited and is often under-utilized due to administrative and technical barriers. International aid and public–private partnerships (PPPs) are also important sources of funding for local authorities. This funding makes it possible to implement structural projects, but access to it is subject to governance and transparency requirements that are often difficult for local authorities to meet (Smoke, 2013). Holtz and Ordu (2021) highlight the challenges of international cooperation in financing local authorities, particularly in terms of access to funds and the ability to manage the projects financed.

2.4. Towards Better Mobilization of Local Resources: Challenges and Prospects

The mobilization of local resources is a major challenge for strengthening the budgetary autonomy of municipalities. There are several obstacles to this mobilization, including insufficient local administrative capacity, lack of taxpayer awareness, and inefficient tax collection systems (Aragon, 2013; Hamilton, 1986).

Holanda Figueiredo Alves et al. (2023) stress the importance of an integrated approach to local government finance, combining strategies for mobilizing their own resources, government transfers, and innovative partnerships to maximize the budgetary efficiency of municipalities.

Reforms are needed to improve local revenue collection. These include (i) adopting a more flexible legal framework that allows municipalities to adapt their taxation to local circumstances (Ebel & Yilmaz, 2002); (ii) strengthening administrative and technical capacity to optimize the management of local finances (Wang & Deng, 2023); and (iii) improving transparency and accountability to encourage people to pay local taxes.

In conclusion, the literature review shows that the financing of decentralization is based on a combination of an area’s own resources, government transfers, and community and international funding. However, the budgetary autonomy of municipalities remains hampered by institutional constraints and weaknesses in mobilizing local resources. A review of the empirical literature also shows that, despite the growing number of studies on local government efficiency, research on the contribution of the financing mechanisms of decentralization to the efficiency of municipalities in sub-Saharan Africa remains relatively limited. This paper therefore seeks to enrich the empirical discussion on this topic by focusing on the specific context of Togo to analyze local government financing mechanisms and their contribution to local government effectiveness.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Administrative Organization of Togo

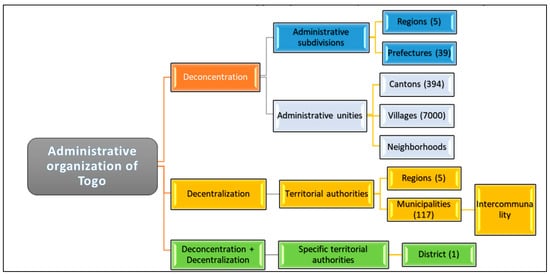

The Togolese Constitution establishes three main levels of state governance: the central level, the regional level, and the communal level (Figure 1). Central governance includes state institutions responsible for managing national affairs, namely the executive power (President of the Republic, Prime Minister, and government), the legislative power (National Assembly and, eventually, the Senate), and the judiciary (Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, Court of Auditors, and other courts). These institutions are complemented by various regulatory and oversight bodies, such as the High Authority of Audiovisual and Communication (HAAC) and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), which ensure institutional balance and the protection of citizens’ rights.

Figure 1.

Administrative organization.

At the territorial level, Togo is divided into regions, which are considered local authorities with regional councils as part of the decentralization process. These five administrative regions—Savanes, Kara, Centrale, Plateaux, and Maritime—provide intermediate governance between the state and local authorities. The final level of governance consists of the 117 municipalities, led by elected mayors and municipal councils, responsible for local management and communal development.

The state oversees local authorities through its representatives, namely the governors and prefects. Governors, as state representatives at the regional level, ensure the implementation of public policies and compliance with national laws within the regions. Prefects, on the other hand, exercise administrative authority at the prefectural level and supervise the actions of municipalities, ensuring coherence between local decisions and national guidelines. This oversight allows the state to ensure the proper functioning of local authorities while supporting their autonomy within the decentralization process.

This research aims to analyze the contribution of local mechanisms to municipal budgets, after mapping the sources of funding for decentralization in Togo. To this end, a mixed approach was adopted, combining descriptive statistics and empirical analysis. The study is based on a structured analytical framework that tests the hypothesis that the resources of Togolese municipalities are still insufficient to guarantee their financial autonomy, despite the fact that they represent the majority of municipal budgets.

The research algorithm comprises several stages: (i) identification and classification of financing mechanisms (local, national, community and international) from official administrative sources; (ii) sampling of municipalities and local finance experts; (iii) collection of primary and secondary data; and (iv) statistical analysis and empirical tests to verify the central hypothesis. The aim is to assess whether local revenues actually provide sustainable financing for municipal budgets, or whether they are structurally supplemented by national transfers, in particular through the FACT.

3.2. Sample Collection

The study covered the 117 communes of Togo. A quota sampling method was used to ensure a balanced representation of the different categories of commune. The sample included 40 communes, or 34% of all communes, divided into four strata according to the number of municipal councilors established by Decree No. 2018-029/PR of 1st February 2018. The breakdown of the selected municipalities is shown in Table 1. Local finance experts were interviewed in each of the communes.

Table 1.

Distribution of sample municipalities by stratum.

In this study, stratified sampling was used to ensure adequate coverage of all categories of municipalities in Togo according to the number of municipal councilors. There are several reasons for using this method in this context. The 117 communes are very diverse in terms of size, financial resources, and governance structure. Stratified sampling ensures that each type of municipality (based on the number of councilors) is represented in the sample, giving more accurate and meaningful results. By dividing the population into four strata based on the number of councilors, stratified sampling ensures proportional representation of each group of municipalities. This reduces the bias that could arise from the under- or over-representation of certain categories of municipality. By ensuring that each stratum is properly represented, the sample is more representative of all municipalities. This increases the reliability of the conclusions drawn from the study. This method also makes it easier to compare results between different categories of local authority by providing separate and comparable data for each group. This is crucial for understanding the differences between municipalities, whether they relate to the management of local finances, taxation, or budgetary capacity.

The selected sample consists of 40 municipalities out of a total of 117. The number of municipalities selected in each stratum is based on a proportional distribution. This means that a certain number of municipalities were selected according to their weight in the total population (Table 1).

In each stratum, the sample is selected so that the proportion of selected municipalities in each stratum is representative of the proportion of municipalities in that stratum in the total population. For example, municipalities with 11 councilors (stratum 1) represent 76/117 of the total population of municipalities, or about 64.9%. However, they represent 24/40 of the sample, or 60% of the sample. This proportion is quite close to that of the total population, which shows a reasonably proportional distribution.

The aim of this approach is to ensure that each sub-group (or stratum) of municipalities is represented in the sample, thereby better reflecting the diversity of municipalities according to their size (number of councilors). This method made it possible to draw a sample representative of the different sizes of municipalities without the need for a complex drawing procedure. In short, this sample is selected in such a way as to guarantee proportional representation of municipalities according to the number of councilors, whilst at the same time allowing a more targeted and relevant analysis of the data according to the different sizes of municipalities.

The sample also includes 188 local finance experts and practitioners, selected using a purposive approach to include the main actors involved in the management of municipal finances. Respondents were selected on the basis of their expertise and their role in the preparation and management of local government budgets. The advantage of including both those responsible for the local government budgetary chain and national experts is that it provides a comprehensive and detailed view of local government finance. This approach provides a better understanding of the differences between municipalities, the regulatory obstacles, and the existing fiscal room for maneuver. These actors come from different structures involved in budget management and local tax legislation. A list of these actors is available from the Department of Decentralization and Local Government (DDCL).

The sample of 188 local finance experts was purposively selected to include key players in the management of local finances. This approach ensures that those with direct expertise in the management of local budgets and local tax legislation are included in the study, which improves the quality of the data collected.

3.3. Data Collection and Processing

The study relies on both primary and secondary data collected from local actors and relevant institutions. Secondary data come from the administrative accounts of municipalities collected from the DDCL. These data allows for an analysis of municipal revenues from individual financing mechanisms (local taxation, state allocations, partnerships, etc.) and helps track the evolution of investments funded by these resources. Primary data were collected using two types of questionnaires administered during July and August 2024. The first questionnaire, addressed to municipal officials, explores the availability of a taxpayer database, limitations to budget growth, and the impact of financing mechanisms on inter-municipal solidarity. The second questionnaire, aimed at national experts and practitioners, covers the same themes except for the management of local fiscal databases.

The surveys were conducted electronically using the KoBoCollect 2024.2.4 application, installed on the smartphones of survey agents. This tool allowed for immediate and secure data entry, minimizing collection errors.

Data processing was carried out in two phases:

- Data cleaning and structuring was performed in Excel 2019 to harmonize responses and prepare the files for analysis.

- Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS 26, including, (i) descriptive analyses (averages, proportions, standard deviations) to measure the importance of different financing mechanisms; (ii) hypothesis tests to assess whether municipalities with a more developed local taxation system are less dependent on national transfers; (iii) multiple regression analysis to identify the main determinants influencing the ability to mobilize their own resources.

3.4. Hypotheses and Analytical Model

The study is based on the following main hypothesis: the individual resources of Togolese municipalities, although they constitute the majority of the municipal budget, are still insufficient to ensure complete financial autonomy.

This hypothesis is tested using the following indicators: (i) the financial autonomy rate, defined as the ratio between own revenues and the total budget; (ii) the correlation between state allocations and local tax levels, to identify a possible inverse relationship suggesting a crowding-out effect of individual resources by public transfers; (iii) the effect of municipality size on the diversification of financial resources.

By integrating a structured analytical framework and empirical tests, this approach goes beyond a simple description of municipal finances to propose a quantitative assessment of local financing mechanisms. The results obtained will then be discussed in the next section, comparing them with existing studies on decentralization and the financial autonomy of local authorities.

4. Results

This section first describes the characteristics of the municipalities surveyed, then presents a map of the financing mechanisms of decentralization in Togo, and finally, the contribution of these mechanisms to the municipalities’ budgets.

4.1. Characteristics of the Sampled Municipalities

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the sampled municipalities. This information relates to the 2022 financial year. The municipalities’ names are coded for anonymity, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of municipalities in 2022 (budget and population in thousands).

An examination of the different levels of municipalities reveals significant differences in terms of surface area, population, budget, and staff. At level 1, the total area is 12,546 km2 with a population of 1,117,348 inhabitants and a total budget of FCFA 2,514,138,000 (Franc of the African Financial Community). This gives an average per capita budget of FCFA 2250 and FCFA 200,000 per km2. Some communes, such as Com 17, have a high budget, while others, such as Com 5, have more limited resources. This level also has different population densities, suggesting a dynamic of urbanization.

Level 2 has an area of 6282 km2 and a population of 665,375. The average budget is FCFA 1,129,525,000, which is lower than the first level. This can be explained by a lower population density and a smaller surface area. This budget corresponds to an average allocation of FCFA 1698 per inhabitant and FCFA 180,000 per square kilometer. Nevertheless, some communes, such as Com 25, have significant budgets, reflecting development priorities.

Level 3 has a total area of 1745 km2 and a population of 764,635 inhabitants. The total budget of FCFA 1,657,190,000 shows a concentration of resources. This result corresponds to an average budget of FCFA 2167 per capita and FCFA 950,000 per square kilometer. These communes have relatively high budgetary resources for their size, probably indicating strong economic activity in these areas. This concentration of resources could further stimulate the local economy and finance infrastructure and public service projects.

Finally, level 4 municipalities are characterized by advanced urbanization, with a total area of 956 km2 and 794,540 inhabitants. The total budget of FCFA 2,900,901,000 translates into an average allocation of FCFA 3651 per inhabitant and FCFA 3,034,000 per square kilometer. Level 4 thus benefits from higher funding per square kilometer, suggesting a concentration of public investment in areas with greater needs for infrastructure and public services.

Regarding the number of municipal employees at each level and its correlation with resource mobilization and the population of the municipalities, it can be observed that municipalities with a higher number of employees show a better mobilization of financial resources. For example, at level 1 the average number of employees per municipality is 21, with an average productivity of FCFA 5,089,000. Level 2 has an average of 18 employees. with an average productivity of FCFA 6,887,000. On the other hand, level 3 has an average of 63 employees with an average productivity of FCFA 6,070,000. Finally, level 4 has an average of 115 employees with an average productivity of 6,433,000 FCFA. These results are consistent with decreasing productivity. There is an optimal number of staff above which budgetary performance decreases. It is 10 for level 1, 20 for level 2, 50 for level 3, and 100 for level 4 Municipalities with more councilors tend to have larger budgets, which may be associated with more complex governance needs. Balancing budgets and services across municipalities will be essential to promote harmonious and equitable development.

4.2. Financing Mechanisms for Decentralization in Togo

The Togolese legislative and regulatory framework for decentralization has provided local authorities with financial resources to enable them to exercise the powers transferred to them. These sources comprise four mechanisms with different categories of revenue, mainly local taxes and fees. Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of these different revenue categories, whether operational or non-operational. A revenue source is operational when it is put into collection status by the authorizing officer or collected by the public accountant (municipal receiver) or the OTR. The OTR collects several taxes and levies on behalf of the municipalities.

Table 3.

Degree of operationalization of different financing mechanisms of decentralization by municipal level.

The documentary analysis shows that there are four main financing mechanisms in Togolese municipalities: local mechanisms made up of allocated taxes and taxes generated by the municipalities; the national mechanism (FACT); community mechanisms supported by sub-regional organizations, notably the UEMOA, the ECOWAS, and the African Union; and international mechanisms supported by TFPs and decentralized cooperation.

Among these mechanisms, those at the local level are the most numerous and provide more resources to municipalities. However, it should be noted that some mechanisms are more operational than others, i.e., the revenue elements of these mechanisms are or are not collected in certain municipalities. According to the degree of operation of the mechanisms in the municipalities (Table 3), there are, among others, the housing tax (98.3%), the single professional tax (99.1%), market taxes (100%), advertising taxes (95.7%) and taxes for sending, registering, and legalizing administrative and civil status documents (99.1%). The degree of non-operation of the mechanisms in the municipalities is more pronounced for fees for emptying and cleaning gutters and septic tanks (87.1%), road tax (99.1%), a tax on the distribution of water, electricity, and telephone services (85.2%), and a tax on local communication companies (87.1%). However, there are differences between and within the levels of local government. For example, the degree of operation of the housing tax (98.3%) is 63.2% in level 1 municipalities, compared with 23.1% in level 2, 7.7% in level 3, and 4.3% in level 4. Road tax, which is 99.1% non-operational, is 64.7% in level 1 municipalities, compared with 22.4% in level 2, 7.8% in level 3, and 4.3% in level 4 (Table 3). Loans are not used by any municipality, although the law authorizes municipalities to borrow from specialized municipal financial institutions and banks.

The FACT, a national mechanism for transferring state subsidies to local authorities, is operational in all Togolese communes. On the other hand, community mechanisms is notoperational in 98.3% of municipalities. The same goes for international mechanisms (88.9%).

4.3. Contribution of Local Mechanisms to Municipal Budgets

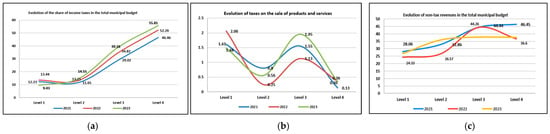

Appendix A shows the shares of the different revenue categories from local mechanisms in the total annual budget of each of the forty municipalities in the sample. Figure 2 shows the curves of means, standard deviations, and coefficients of variation in the contributions of local mechanisms to the municipal budgets between 2021 and 2023. The total contributions of sales of products and services, tax revenues, non-tax revenues, and FACT transfers are presented by sector in Figure 2 for 2021, 2022, and 2023.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the shares of local mechanisms in municipal budgets between 2021 and 2022: (a) taxes in the total municipal budget; (b) taxes on the sale of products and services; (c) Non tax revenues in the total municipal budget.

In most municipalities, sales of products and services make a small contribution to the municipal budget (Appendix A). In level 1 municipalities, sales of products and services contributed only 1.61% in 2021, 2.06% in 2022, and 1.48% in 2023. In level 2 they are estimated to have contributed 0.8% in 2021, 0.25% in 2022, and 0.56% in 2023. For level 3 municipalities, sales of goods and services remain marginal, rising from 1.55% in 2021 to 1.13% in 2022 and then to 1.95% in 2023. This result indicates a minimal contribution from this source. It also means that municipalities are not significantly dependent on the sale of products and services to finance their operations. In level 4 municipalities, the sale of products and services is almost negligible in the municipal budget, with percentages close to zero: 0.13% in 2021, 0.36% in 2022, and 0.35% in 2023.

Tax revenues for level 1 municipalities fluctuates from 12.23% in 2021 to 13.44% in 2022 and 9.43% in 2023. This fluctuation could reflect difficulties in mobilization or changes in the tax base of the municipalities in this level. The share of this category of revenues in level 2 is 11.65% in 2021, rising to 14.55% in 2023, which could indicate an increase in collection efforts or a broadening of the tax base. At levels 3 and 4, tax revenues are a significant and growing part of local government budgets. Their share is 29.02% in 2021 and 39.16% in 2023 in level 3 municipalities. Tax revenue accounts for 52.26% and 55.81% of the budget of level 4 municipalities in 2022 and 2023, respectively.

Non-tax revenues constitute an essential component of municipal budgets, primarily derived from the exploitation of municipal assets and other non-taxable revenue sources. They encompass various categories of income, including rents collected from the leasing of municipal properties (markets, bus stations, land, administrative and commercial buildings), fees for temporary occupation of public spaces, parking fees, and proceeds from the sale of municipal assets. Additionally, they include dividends from municipal stakes in local businesses, revenues from concessions and public–private partnerships, as well as certain fines and administrative penalties.

These resources play a predominant role in financing local governments due to their relative stability and ability to generate funds without directly depending on state transfers. In level 1 municipalities, they accounted for 28.06% of the municipal budget in 2022 and 26.74% in 2023, illustrating a certain consistency in their contribution. In level 2 municipalities, non-tax revenues increased from 32.86% in 2021 to 35.94% in 2023. In levels 3 and 4, they also constituted a significant share of municipal resources, decreasing from 44.44% in 2021 to 37.86% in 2023 for level 3, and from 46.45% in 2021 to 37.68% in 2023 for level 4.

However, these mechanisms are not uniformly utilized across the territory. A distinction can be made between operational mechanisms, meaning those whose revenues are effectively collected and mobilized by municipalities, and non-operational mechanisms, which, although provided for by regulations or local strategies, are not always implemented for various reasons.

The lack of operationalization of certain mechanisms can be attributed to several factors, such as the absence of a clear regulatory framework, administrative difficulties in revenue collection, a lack of structuring of municipal assets, or resistance from local economic actors to paying these fees.

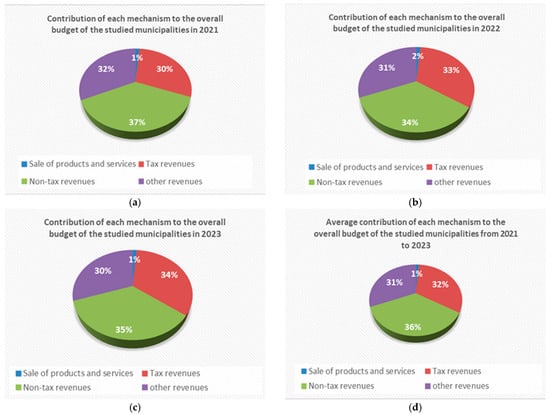

In 2021, ‘non-tax revenues’ dominate the contribution to local government budgets with a share of 37%. This is closely followed by ‘tax revenue’, which accounts for 30% of the budget, and ‘other revenue’, including national, community, and international mechanisms, which accounts for 32% (Figure 3a). It also shows that the sale of products and services accounts for only a small part of the budget (1%). This distribution highlights the importance of tax and non-tax revenues for local government finances, while revenues from the sale of products and services remain marginal.

Figure 3.

Weight of local and national mechanisms in municipal budgets between 2021 and 2023, (a) in 2021; (b) in 2022; (c) in 2023; and (d) cumulative period (2021 to 2023).

The year 2022 shows a similar distribution to 2021, with some slight variations. The share of ‘non-tax revenues’ decreases slightly to 34%, while ‘tax revenues’ increases to 33%. The share of ‘other mechanisms’ remains stable at 31%, and ‘sales of goods and services’ increases slightly to 2% (Figure 3b). These small changes may reflect a slight increase in economic activity in municipalities, although the overall structure of the contribution to the budget remains constant.

In 2023, the percentages show a further slight evolution. The share of ‘tax revenue’ continues to rise, reaching 34%, while ‘non-tax revenue’ falls slightly to 35%. The share of ‘other mechanisms’ is 30% and ‘sales of products and services’ remains stable at 1% (Figure 3c). These trends indicate that tax revenue is gradually becoming a more important source of financing for local governments, although the general structure remains similar to previous years.

In the average period from 2021 to 2023, ‘non-tax revenues’ represent the largest share at 36%, followed by ‘tax revenues’ at 32% and the category ‘other mechanisms’ at 31%. The ‘sale of products and services’ remains marginal, accounting for only 1% on average (Figure 3d). This stability in average proportions confirms the dependence of local government budgets on tax and non-tax revenues, with a slight increase in the importance of tax revenues over the years. This finding also highlights the potential of initiatives aimed at strengthening tax collection to improve local government budgets.

4.4. Municipal Capacity to Mobilize Own Resources

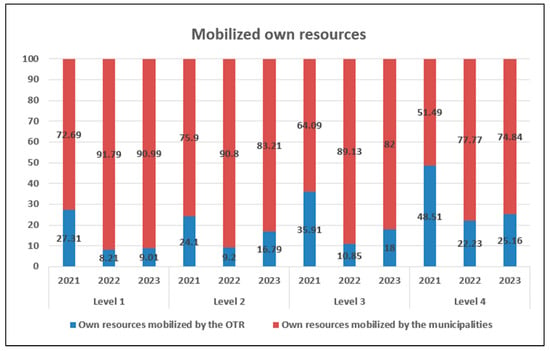

One of the challenges to the effectiveness of decentralization in terms of its potential impact on the territories is the mobilization of their own resources to improve the financial base of the municipalities. To maintain their economic, social, and political rationale, Togolese communes must mobilize sufficient financial resources to be self-sufficient. Figure 4 shows the share of resources of the communes and the OTR.

Figure 4.

Capacities for mobilizing own resources.

An analysis of the mobilization of their own resources by the municipalities and the OTR over the period 2021–2023 reveals several significant trends. The municipalities rely more on their own resources than on those mobilized by the OTR. The average of the resources mobilized by the municipalities is higher than that of the OTR for all levels, except for level 4, where the two parts are relatively close in 2021.

Looking at the different levels, level 1 shows an OTR mobilization of 27.31% in 2021, while the municipalities’ share is 72.69%. In 2022 and 2023, the share mobilized by the OTR decreased, while that of the municipalities remains stable, reaching 91.79% and 90.99%, respectively (Figure 4). This trend shows that the resources of the level 1 municipalities come from the mobilization of the municipalities. This finding indicates a growing dependence of the municipalities on their resource mobilization.

For level 2, the percentages also favor the municipalities, with a mobilization by the OTR of 24.10% in 2021, which then decreased over the years. The average of 16.41% for the OTR and 83.59% for the municipalities reinforces the idea of their dependence on their own resource mobilization. Level 3 shows more marked variations, particularly in 2021 when the OTR mobilizes a higher proportion (35.91%). Nevertheless, the trend is towards an increase in the autonomy of the municipalities, especially in 2022 and 2023 when their share exceeds 89%.

In level 4, the OTR has the greatest influence, especially in 2021 when it was 48.51%. However, the following years show a decrease in this mobilization, while the municipalities’ share increased, reaching 74.84% in 2023. The average of 31.19% for the OTR shows that, even at this level, the municipalities are becoming less dependent on the mobilization of their own resources. Contrary to the assertions of Hamilton and Aragon (Aragon, 2013; Hamilton, 1986), according to which local authorities are less efficient than the central government in collecting taxes, we observe the performance of Togolese municipalities in mobilizing their own resources, all other things being equal.

4.5. Factors Limiting the Ability of Local Authorities to Mobilize Their Own Resources

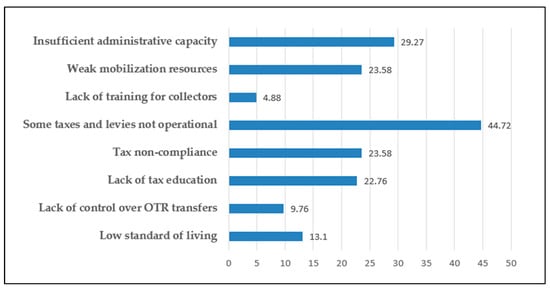

The mobilization of resources remains a major challenge for local authorities. This may be due to a number of factors that do not favor the optimal mobilization of their own financial resources. This section, including the data in Figure 5, allows us to identify the difficulties faced by local authorities in Togo in mobilizing their own resources.

Figure 5.

Factors hindering revenue growth according to the survey of experts and practitioners.

Municipal finance experts and practitioners identified several major obstacles to own resource mobilization, some of which stand out. Figure 4 shows that the non-operational nature of services, cited by 44.72% of respondents, is the most frequently cited obstacle, illustrating a structural inability to effectively implement local mechanisms. This problem is exacerbated by insufficient administrative capacity (29.27%), indicating gaps in skills and management within the collection services.

In addition, tax incivility and poor mobilization each account for 23.58% of the causes of non-productivity, highlighting the low level of taxpayer cooperation and the lack of material and human resources to reach taxpayers effectively. The lack of tax education (22.76%) reinforces this observation; the lack of awareness of the importance of taxes hampers collection, while the low standard of living (13.01%) and the lack of transfer of certain taxes collected by the OTR to the municipalities (9.76%) limit the incentive for taxpayers to pay taxes (Figure 5). Elected officials also report a marked reluctance on the part of taxpayers, fueled by insufficient action by the authorities to build trust.

The lack of training for collectors (4.88%), although less frequently cited, remains a challenge and contributes to the lack of commitment and skills among agents. Other obstacles such as the inaccessibility of certain areas and internal organizational problems (sometimes due to inappropriate behavior by some agents) complete the picture. Respondents insist on the need for better organization and an effective recovery strategy to address these challenges. The combination of structural failures, administrative shortcomings, and intransigent behavior thus calls for reforms on several fronts to increase the mobilization of local resources.

Table 4 shows that the vast majority of stakeholders interviewed support the transfer of certain additional taxes and levies from the state to municipalities. Indeed, mayors, administrative, and financial directors (DAFs), as well as secretaries-general (SG) demonstrate high levels of approval (20.8%, 19.2%, and 19.2% for “Yes”, respectively), with very little opposition.

Table 4.

Stakeholders’ opinions on the necessity of additional transfers of certain taxes and levies to municipalities.

Finance committee chairpersons, while slightly less pronounced, also follow this trend (12.8% in favor versus 3.2% against), whereas the financial controller appears more divided, with a balanced distribution of opinions. These results indicate a general willingness among local financial officials to see increased state participation to help address municipalities’ budgetary challenges.

4.6. The Challenges to Local Resource Mobilization in Togo Are Manifold

Firstly, the local tax base is weak, with municipalities relying mainly on underutilized taxes such as those on housing, businesses, and administrative documents, without adequately including the informal sector. Secondly, there is a lack of administrative and technical capacity within municipalities, with officials often inadequately trained in financial management, budget planning, and tax collection, which limits the effectiveness of financial management. In addition, collection mechanisms are inefficient due to poor organization, lack of modern infrastructure for tax monitoring, and low citizen awareness of their fiscal obligations. Moreover, excessive dependence on national subsidies prevents municipalities from strengthening their fiscal autonomy and financing their own development projects. Inequality of resources between municipalities, with higher revenues in urban areas such as Greater Lomé, exacerbates regional disparities. Finally, the lack of a tax culture and low levels of citizen participation contribute to a limited commitment to local taxation, which hampers tax collection efforts.

These combined causes explain the limited contribution of local financing mechanisms to municipal budgets and highlight the need for structural reforms to strengthen the financial autonomy of municipalities, improve their management capacity, and diversify their funding sources.

5. Discussion

This study provides a better understanding of the financing mechanisms for decentralization in Togo and their contribution to local government budgets. Based on their origin, the sources of revenue for municipalities were grouped into the following four main mechanisms: local, national, community, and international. The analysis shows that communal resources and state subsidies via FACT are the main sources of funding for their budgets. However, some local mechanisms still have to operate in several municipalities due to structural and regulatory constraints.

5.1. Municipal Own Resources

An analysis of the mechanisms for financing decentralization in Togo reveals a number of shortcomings. Togolese communes face serious difficulties in providing adequate basic infrastructure. This is mainly due to the lack of local financial resources. This phenomenon is also observed throughout Africa (Ndamsa et al., 2022; Otoo & Danquah, 2021; Tanoh, 2019). Local taxation is still underdeveloped and, with the exception of the communes of Greater Lomé, few Togolese communes have revenue-generating resources.

Local taxation, an important counterpart to devolution, accounted for only 30% of municipal budgets in 2021, while local non-tax revenues (mainly from the sale of products and services) accounted for 37% over the period studied. These results confirm the work of Bird and Smart (2002) and Faguet (2012), who have analyzed similar issues in other developing countries. According to Bird and Slack (2004), the limited access of local governments to a sound tax base is a major obstacle to their financial autonomy. Fjeldstad (2013) point out that the appropriate pricing of local services can strengthen the financial sustainability of municipalities and reduce their dependence on government transfers. The difficulties associated with setting local taxes are manifold and have a profound impact on the financial autonomy of local authorities, thus hampering their ability to respond effectively to citizens’ needs (Otoo & Danquah, 2021). These difficulties can be analyzed from several angles, including local taxation, the identification of taxpayers, and the management of tax resources.

Togolese municipalities have little power to set and collect taxes. They continue to face major structural and institutional challenges. Legal and regulatory restrictions, such as those imposed by Article 332 of the LRDLL and Decree No. 2021-039, limit their ability to adjust tax rates or create new taxes tailored to local circumstances. National laws determine the list of taxes and their maximum rates. This situation leads to a kind of passivity at the local level as municipalities cannot adapt these taxes to their specific needs Adjahi and Traore (2021) have also pointed out that local authorities in West Africa do not have taxing powers. This limits their ability to generate their own resources and ensure adequate funding for their development projects. According to Ndamsa et al. (2022) and Tanoh (2019), the lack of decision-making power over local taxation hinders the financial autonomy of local authorities and makes them largely dependent on the state.

Another major difficulty is the identification of taxpayers. Due to the lack of human, technical, and financial resources in the tax and treasury departments, tax collection is particularly inefficient. These findings corroborate those of Gomes Olamba (2013), Ndamsa et al. (2022), and Tanoh (2019), who argue that local authorities often lack reliable information on businesses and citizens likely to contribute to local taxes. This leads to under-reporting and low collection rates, undermining the efficiency of the local tax system.

Tax evasion is another problem that complicates local tax collection. The informal sector, which makes up a large part of the economy in many regions, largely escapes local taxation (Holtz & Ordu, 2021). Often poorly identified by tax authorities, this sector is rarely taxed, depriving local authorities of significant resources. Moreover, tax evasion increases when citizens believe that the public services provided by local authorities are insufficient or of poor quality (Flan et al., 2022). This situation creates a vicious circle in which a lack of trust in the tax authorities and weak public services lead to low tax compliance. The development of the informal sector contributes to this evasion, making it even more difficult for local authorities to ensure efficient and fair tax collection.

These various difficulties have a direct impact on local finances. If local authorities do not have the means to set and collect local taxes efficiently, they become more dependent on transfers from the state, which limits their room for maneuver in financing their development projects.

5.2. State Transfers and Attracting Donor Funding

Although local resources account for around 70% of municipal budgets, Togolese municipalities still need support to achieve full financial autonomy. Municipal investment remains mainly dependent on FACT transfers, which accounted for 32% of budgets in 2021. This conclusion was reached in studies by Holanda Figueiredo Alves et al. (2023), Ndamsa et al. (2022), Otoo and Danquah (2021), and Tanoh (2019). According to Otoo and Danquah (2021), Metropolitan and Municipal District Assemblies (MMDAs) in Ghana are heavily dependent on central government for funding. In 2014, only 21% of total revenue came from local income tax (IGF), indicating that MMDAs are highly dependent on government grants and transfers, as well as donor funding (Otoo & Danquah, 2021). Tanoh (2019) made the same observation for local governments in Côte d’Ivoire. Financial transfers, often in the form of grants or subsidies, play a crucial role in the financing of local governments. However, several factors limit their effectiveness and impact on local development. These grants can be either general or earmarked, but their inadequacy, irregularity, and late disbursement are significant obstacles to the ability of local governments to exercise their responsibilities (Adjahi & Traore, 2021).

In addition, the financial dependence of Togolese municipalities on the central government poses a number of challenges in terms of financial autonomy and the management of local resources. This dependence limits their ability to manage their own resources independently. As noted by Otoo and Danquah (2021) and Ndamsa et al. (2022), communes often lack decision-making power. According to them, local governments lack the necessary flexibility to respond quickly and effectively to the needs of citizens. Decisions on allocating funds, implementing projects, or prioritizing local needs are often influenced by central government priorities rather than the specific needs of local communities.

This reliance on government transfers reflects weak local fiscal and administrative capacity, exacerbated by management problems, tax evasion, and inefficient tax collection (Devas & Kelly, 2001). Tanoh (2019) also found that Ivorian local governments lack the capacity to strengthen their own resource mobilization systems. This limits their ability to generate sustainable revenues and independently finance their projects (Otoo & Danquah, 2021). One of the main causes of this weak resource mobilization in Togo is often tax non-compliance and the inefficiency of local administrations in collecting taxes. Local authorities may have difficulties in identifying taxpayers, administering local taxes, and effectively collecting tax revenues, which prevent them from developing their own resources. However, decentralization funds and state grants to local governments remain insufficient.

The inadequacy of local governments’ own financial resources and the weakness of government financial transfers are major obstacles to achieving decentralization goals and promoting local development. Sufficient financial resources are essential for municipalities to ensure the provision of quality public services, finance basic infrastructure, and support local economic development initiatives. However, in the face of these challenges, Togolese municipalities are turning to community mechanisms and development partners.

In addition to government funding, municipalities also depend on international donors to support some of their development projects. Although these external funds can be crucial for financing large infrastructure and development projects, this dependence makes municipalities vulnerable to the conditions imposed by these donor partners. Sometimes, these funds are tied to specific conditions that are not necessarily in line with local priorities, and their availability can be affected by external factors such as changes in donor priorities or international crises (Adjahi & Traore, 2021; Tanoh, 2019).

5.3. Inefficiency and Inadequacy of Fiscal Transfers

While public transfers are essential to address inter-municipal disparities, they also have limitations. As Bird and Smart (2002) point out, poorly designed transfer mechanisms can discourage local resource mobilization and weaken the fiscal autonomy of local governments. However, Faguet (2012) stresses that well-structured transfers and genuine decision-making autonomy can significantly improve public service delivery. In the Togolese context, the FACT Management Commission has set clear conditions for the use of transferred grants, whether earmarked or not, to ensure greater mobilization of local resources.

The disparities between local resources and government allocations raise critical questions about the effectiveness of fiscal decentralization in Togo. A thorough fiscal and budgetary reform is needed to strengthen the capacity of local governments to mobilize their own resources. As Faguet (2012) notes, without greater fiscal autonomy and better transfer mechanisms, local governments will remain dependent on the central state and will not have the means to meet the needs of their populations.

Transfers to cover operating costs, such as equalization grants or solidarity funds, are intended to ensure that local governments can maintain basic public services such as education, health, infrastructure maintenance, and security. However, their inadequacy directly affects the quality of these services (Tanoh, 2019). For example, some Togolese communes may struggle to pay staff salaries, leading to strikes, a decline in the quality of services, or a shortage of staff in key sectors. According to Flan et al. (2022) and Ndamsa et al. (2022), operating grants are often designed to fill the gap between local revenues and expenditures, but in a context where these grants are insufficient, local governments face difficult choices, sometimes at the expense of essential services.

Finally, in order to optimize the contribution of local mechanisms, local governments must commit themselves to strengthening their administrative and technical capacities while developing resource mobilization strategies adapted to local realities. More efficient management of local taxes and greater awareness of the importance of fiscal contributions could play a key role in this effort. The success of decentralization in Togo will depend not only on structural reforms, but also on political will and the active involvement of local actors. It is also crucial to promote borrowing as a source of financing. Borrowing can increase the autonomy of municipalities by enabling them to finance short-term projects without being entirely dependent on government grants. This could contribute to more effective resource management and encourage better project planning. However, it is essential that decentralization policies promote transparent borrowing management, fiscal responsibility, and the ability of the municipality to manage its resources effectively. Decentralization policies must also take into account the financial autonomy of local governments to ensure that they can develop infrastructure projects and public services tailored to the specific needs of local populations.

5.4. Practical Implications of the Findings

The results of the study show that Togo’s municipalities are too dependent on national subsidies and generate little local tax revenue. This highlights the need to reform the local tax system, in particular by introducing local taxes (property, business, etc.) and incentive mechanisms to improve tax collection. It is also essential to strengthen the financial management capacity of local authorities, in particular through training programs for municipal officials. In addition, the study identifies public–private partnerships (PPPs) and municipal loans as solutions for diversifying funding sources, requiring a revision of decentralization laws to allow municipalities to take out compulsory loans to finance local projects.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive mapping of the financing mechanisms of decentralization in Togo, analyzing the role of local taxation, levies, and intergovernmental transfers in municipal budgets. The findings reveal that despite a diversity of funding sources—local, national, community-based, and international—local governments remain heavily dependent on central government transfers, particularly through the Local Authorities Support Fund (FACT). Several constraints limit the effectiveness of these financing mechanisms, including administrative and legal barriers, the requirement for central approval of certain local taxes, and the absence of a regulatory framework to facilitate municipal borrowing. These obstacles hinder the capacity of local authorities to mobilize resources and finance development projects autonomously. Municipal budgets remain small and insufficient to meet growing urbanization challenges, reinforcing the urgent need for fiscal reforms that enhance local revenue generation.

This study makes a significant contribution to research and policymaking by providing an empirical analysis of the financial structures supporting decentralization in Togo. By identifying key limitations and challenges, it offers insights to guide reforms toward more efficient and context-specific financial governance. However, several methodological limitations should be noted. The analysis is primarily based on municipal budget data and legal frameworks, without a comparative perspective from other West African countries that have implemented similar reforms. Additionally, while local actors’ perspectives are considered, a more detailed investigation through case studies could enrich the understanding of the practical challenges municipalities face.

For future research, a comparative study of the financing models of decentralization in West Africa would provide valuable lessons on best practices and strategies tailored to local contexts. Furthermore, an in-depth assessment of fiscal reforms and their impact on municipal revenues over time would offer a clearer picture of the effectiveness of existing financial mechanisms. Finally, incorporating a longitudinal dimension—tracking the evolution of local finances over multiple years—would allow for a more nuanced analysis of decentralization financing trends and their implications for sustainable territorial development in Togo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P methodology, E.P.; validation, E.P., C.C.A. and F.P.Y.; formal analysis, E.P.; investigation, E.P.; data curation, E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.; writing—review and editing, E.P.; visualization, E.P.; supervision, C.C.A. and F.P.Y.; project administration, C.C.A.; funding acquisition, E.P., C.C.A. and F.P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by World Bank through the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON), University of Lomé, grant number IDA 5360 TG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization and Customary Chieftaincy (previously Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization and Territorial Development).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FACT | Local Authorities Support Fund |

| OTR | Togolese Tax Office |

| PPP | public–private partnerships |

| DDCL | Directorate of Decentralization and Local Authorities |

| WAEMU | West African Economic and monetary Union |

| ECOWAS | Economic Community of West African States |

| UCLG | United Cities and Local Governments |

| PPP | public–private partnerships |

| HAAC | High Authority of Audiovisual and Communication |

| CNDH | National Human Rights Commission |

References

- Adjahi, D. M., & Traore, A. B. (2021). Atelier régional d’échanges sur les dispositifs de financement des collectivites territoriales en Afrique de l’ouest (31p). CONAFIL Bénin, la GIZ, CGLU-Afrique, UNCDF et les Partenaires de l’Observatoire Mondial des Finances et de l’Investissement des Collectivités Territoriales. Available online: https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/rapport_atelier_regional_dechanges_dispositifs_de_financement_des_ct.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Altunbas, Y., & Thornton, J. (2012). Fiscal decentralization and governance. Public Finance Review, 40(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, F. M. (2013). Local spending, transfers, and costly tax collection. National Tax Journal, 66(2), 343–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awortwi, N. (2016). Decentralization and local governance approach: A prospect for implementing the post-2015 sustainable development goals. In G. M. Gómez, & P. Knorringa (Eds.), Local governance, economic development and institutions (pp. 39–63). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, R. (1999). Fiscal decentralization as development policy. Public Budgeting & Finance, 19(2), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, R., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2006). Sequencing fiscal decentralization. The World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R. M., & Slack, E. (Eds.). (2004). International handbook of land and property taxation. Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, R. M., & Smart, M. (2002). Intergovernmental fiscal transfers: International lessons for developing countries. World Development, 30(6), 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGLU. (2015). Priorités stratégiques 2016–2022. Available online: https://www.cglu.org/sites/default/files/priorites_strategiques_2016-2022.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Coquart, P. (2013). La décentralisation fiscale en Afrique—Enjeux et perspectives (2009), Karthala, et « La gouvernance financière locale » (non daté), partenariat pour le développement municipal (PDM), de François Paul Yatta. Techniques Financières et Développement, 112(3), 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devas, N., & Kelly, R. (2001). Regulation or revenues? An analysis of local business licences, with a case study of the single business permit reform in Kenya. Public Administration and Development, 21(5), 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doho, A. W., Ahmed, A., & Umar, A. (2018). Local government autonomy in Nigeria: Struggles and challenges. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(5), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, R. D., & Yilmaz, S. (2002). On the measurement and impact of fiscal decentralization. The World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faguet, J.-P. (2012). Decentralization and popular democracy: Governance from below in Bolivia. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fjeldstad, O.-H. (2013). Mobilization des recettes des administrations locales en Afrique anglophone. Centre International Pour La Fiscalité et Le Développement, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Flan, M. C., Christian, B., Mamadou Hafiziou, B., Thierno, M. D., & Blanche, S. (2022). Le financement des collectivités territoriales décentralisées en Afrique de l’Ouest: Un défi pour le développement local (22p). Solution Think Tank. Available online: https://solutionthinktank.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/PP_STT_2022_Financement-collectivites-territoriales_20240206.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Gomes Olamba, P. N. (2013). Décentralisation, démocratie et développement local au Congo-Brazzaville. l’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Gourmel-Rouger, C. (2015). Financement des collectivités locales par les émissions socialement responsables: Quelles perspectives? Cas des régions françaises. Revue d’Economie Financiere, 118(2), 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. H. (1986). The flypaper effect and the deadweight loss from taxation. Journal of Urban Economics, 19(2), 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda Figueiredo Alves, P. J., Araujo, J. M., Acris Melo, A. K., & Mashoski, E. (2023). Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: Evidence from Brazilian states. Public Sector Economics, 47(2), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, L., & Ordu, U. A. (2021). The role of fiscal decentralization in promoting effective domestic resource mobilization in Africa. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-role-of-fiscal-decentralization-in-promoting-effective-domestic-resource-mobilization-in-africa/ (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- McLure, C., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2011). The assignment of revenues and expenditures in intergovernmental fiscal relations (41p). World Bank Institute’s Decentralization. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252586054_The_Assignment_of_Revenues_and_Expenditures_in_Intergovernmental_Fiscal_Relations (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Ndamsa, D. T., Sevidzem, M. C., & Tangwa M., W. (2022). Fiscal decentralization and intergovernmental fiscal relations in Sub-Saharan Africa: A critical literature survey and perspectives for future research in cameroon. PanAfrican Journal of Governance and Development (PJGD), 3(2), 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal federalism. Harcourt; Brace; Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunnubi, O. O. (2022). Decentralization and local governance in Nigeria: Issues, challenges and prospects. Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, (27). 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, I., & Danquah, M. (2021). Fiscal decentralization and efficiency of public services delivery by local governments in Ghana. African Development Review, 33(3), 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoke, P. (2013). Why theory and practice are different: The gap between principles and reality in subnational revenue systems. In J. Martinez-Vazquez, & R. M. Bird (Eds.), Taxation and development: The weakest link? (p. 37). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondou, T., Anoumou, K. R., Aholou, C. C., Chenal, J., & Pessoa Colombo, V. (2024). Urban growth and land artificialization in secondary African cities: A spatiotemporal analysis of Ho (Ghana) and Kpalimé (Togo). Urban Science, 8(4), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, M., & Razafimahefa, I. (2017). Fiscal decentralization and fiscal policy performance. Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Fiscal-Decentralization-and-Fiscal-Policy-Sow-Razafimahefa/69626cfa2961f8f4620061055feafd8cac83080f (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Taleat, B. A. (2017). Governance and the rule of law in Nigeria’s fourth republic: A retrospect of local government creation in Lagos state. Canadian Social Science, 13(10), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoh, M. A. (2019). Décentralisation et bonne gouvernance des états francophones ouest africains: Contribution à l’étude du cas de la Côte d’Ivoire [Ph.D. thesis, Université de Perpignan]. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-02972019v1/document (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., & Deng, W. (2023). Fiscal decentralization and county natural poverty: A multidimensional study based on a BP neural network. Sustainability, 15(18), 13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatta, F. P. (2009). La décentralisation fiscale en Afrique: Enjeux et perspectives. Éd. Karthala Direction du Développement et de la Coopération. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F., & Lu, Y. (2022). Carbon emission reduction effect of China’s financial decentralization. Sustainability, 14(22), 15003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).