Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between a firm’s working capital policy and the volatility of its stock returns. We find that a firm with an aggressive working capital policy tends to exhibit a higher level of return volatility. This finding is robust across years and industries after controlling for factors such as financial stability and sales growth. Our results further indicate that aggressively managed working capital policy affects return volatility through idiosyncratic risk. A decrease in working capital results in the contemporaneous and subsequent increases of return volatility. Our evidence is consistent with the conjecture that there is an important link between a firm’s working capital policy and its stock return volatility. Thus, firm managers must incorporate the potential costs associated with higher stock return volatility into their working capital decision-making when adopting a tightened working capital policy.

Keywords:

working capital policy; return volatility; market risk; idiosyncratic risk; working capital management JEL Classification:

G32; M11; M40

1. Introduction

During past decades, individual firms’ return volatility has increased, but the market volatility has remained almost at the same level over the same period. Irvine and Pontiff (2009) find that increased stock return volatility is caused by idiosyncratic return volatility and firm-level cash flow fluctuations. Campbell et al. (2023) further confirm that idiosyncratic volatility experienced sharp increases during the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–2021, despite declining after the spike in the 1999–2000 period. Stock return volatility is generally driven by fundamental sources, such as the levels of competition among firms, which have an impact on the cash flow volatility. In this paper, we add to the literature by arguing that an aggressively managed working capital policy may cause greater return volatility, which leads to unintended costs to the firm, and provide evidence to show how the working capital policy is related to the stock return volatility.

Does an aggressively managed working capital policy benefit shareholders?1 The standard textbook usually suggests that firm managers should manage corporate working capital more aggressively in order to create value for shareholders, especially when a firm faces strong competition from its competitors. This is because an aggressively managed working capital policy can generate free cash flows, save financial and operating costs, and raise earnings, thus resulting in a higher share price for the firm. It also increases a firm’s growth opportunities through optimal resource allocations.2 Nonetheless, even though there is a trend that firms tend to adopt aggressively managed working capital policy during recent years, according to the 2023 CFO/The Hackett Group Working Capital Scorecard (The Hackett Group, 2023), the 1000 largest U.S. companies increased their net working capital by 11% in 2022, to surpass $1.54 billion.3 If working capital should be managed aggressively, it is of interest to explore why so many firms still implement conservative strategies in managing their working capital, especially in the world of intense global competition. We conjecture that there is a link between a firm’s working capital policy and its stock return volatility, and the concern of increased return volatility may be one of the reasons that prevent firm managers from adopting an aggressive working capital management policy.

In this paper, we use the net operating working capital, defined as the working capital requirement to sales ratio, as the measure for working capital policy. It is worth devoting attention to topics related to working capital requirements because they are directly related to the firm’s operating cycle. Hill et al.’s (2010) document states that the working capital requirement to total assets ratio is 22.7% between 1996 and 2006. This statistic is greater than the cash to total assets ratio (22.0%), a financial decision-related component. Furthermore, Hawawini et al. (1986) argue that components not closely related to a firm’s operating cycle should not be included to form working capital policy measures. Despite its importance, few studies comprehensively examine operating working capital strategy.

High stock return volatility is an important issue for both firm managers and investors because excess return volatility is undesirable. There are mainly two reasons that return volatility matters. First, it is widely recognized that increases in return volatility lead to higher financing costs because investors will request higher returns for bearing greater risk, and the cost of debt also increases. To avoid a high cost of capital, firm managers may steer clear of higher levels of return volatility for their stocks (Bushee & Noe, 2000). Second, as stock returns serve as a signal for firms’ intrinsic value, an increase in return volatility makes it difficult for investors to determine the true value of a firm and incurs higher monitoring costs, which will prevent shareholders from playing an effective monitoring role (Harris & Raviv, 2008). Moreover, higher return volatility implies more information flows and informed trading, which could reduce shareholders’ trust and thus affect capital structure decisions (Bharath et al., 2009). Karolyi (2001) concludes that excessive return volatility is detrimental to shareholders, making it a concern for investors, analysts, brokers, dealers, and regulators.

Following prior studies (Sias, 1996; Bushee & Noe, 2000), we compute the standard deviation of daily stock returns for a year to measure return volatility and examine whether the firm’s working capital policy affects its stock return volatility. Our results reveal that when firms adopt an aggressive approach to manage working capital, their stock returns are likely to become more volatile. There is a negative correlation between a firm’s working capital policy and its return volatility, and our findings are strongly significant across all sample years. We further estimate that, on average, one standard deviation decrease in the working capital policy measure results in at least a 2.87% increase in return volatility. Given that the average return volatility in our sample is 3.77%, this upswing in return volatility has an economic meaning for the investors. Although the working capital policy may vary from industry to industry, our results are generally consistent across industries using Fama and French’s (1997) 48-industry classification. Our findings are still robust after controlling for various variables employed in the literature. We also find evidence that a firm’s working capital policy is negatively correlated to its level of idiosyncratic risk but positively associated with market risk. In other words, a firm with an aggressive working capital policy tends to have a greater firm-specific risk, which is not related to the market. This finding sheds some light on why aggressively managed working capital policy may be costly to firms: increased idiosyncratic risk implies higher information asymmetry and more informed trading, and a higher level of private information leads to a higher cost of capital.

A potential alternative explanation for our results is that firms in financial distress or with high levels of information asymmetry tend to adopt an aggressive approach to manage their working capital to preserve cash. Aktas et al. (2021) find that financially constrained firms frequently use working capital incentives, particularly in the form of executive bonuses tied to the management of working capital components such as inventories and payables. Also, information asymmetry may affect the costs of external financing (Petersen & Rajan, 1997). Since it is expensive for high-return-volatility firms to seek external financing, they may be forced to adopt aggressive working capital policies to generate cash. We find that working capital policy and return volatility affect each other, but the former has a stronger impact than the latter. Our results demonstrate that changes and levels of working capital policy explain contemporaneous and future return volatility, but changes in return volatility do not influence working capital policy. Thus, when a firm changes its working capital policy, the return volatility will immediately respond to the change, and the impact will last into the future.

We rerun our tests by excluding firms under financial distress and controlling for sales growth. Since the results hold across various levels of sales growth and for non-financially distressed firms, it is unlikely they are driven by financial distress. The findings are also robust to a variety of alternative working capital policy measures commonly used in the literature, including working capital requirement, defined by Shulman and Cox (1985) and Hawawini et al. (1986), and net trade credits, defined by Love et al. (2007), and are robust against popular return volatility measures in French et al. (1987) and Bae et al. (2004). To address the endogeneity issue, we perform additional tests to confirm that a switch to a more aggressive working capital policy immediately increases return volatility with lasting effects. The reverse causality does not exist.

This paper makes significant contributions to several strands of literature. First, we show that working capital policy affects stock return behavior, and aggressive working capital management policy is related to greater return volatility—often undesirable for managers and investors. Our work also represents the first attempt to relate a firm’s working capital policy directly to its stock return volatility. Molina and Preve (2009) find that a significant reduction in the trade receivables will cause financially troubled firms to experience an additional drop in sales and stock returns. This implies that freeing up excess working capital may not necessarily enhance financial and operating performance. Hill et al. (2012) find that relaxing credit policy creates value for shareholders, reduces costs related to uncertain sales, and mitigates asymmetric information about product quality. Using the rankings from the CFO Magazine working capital scorecard, Filbeck et al. (2017) study the working capital management from an investor’s perspective and show that firms with superior working capital strategies have higher returns. We join the debate and introduce another dimension of the potential impacts of aggressive working capital policy—the stock return volatility—and investigate the relationship between working capital policy and the firm’s overall risk. Second, we document that the aggressive working capital policy affects return volatility through firm-specific risk. To the best of our knowledge, this issue has not been addressed in the literature. Our findings underscore the need for managers to weigh the advantages of aggressive working capital management against the potential costs of higher return volatility.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses related literature and develops our hypothesis. Section 3 describes the data and sample selection as well as the research methodology. Section 4 examines the relationship between working capital policy and return volatility. Section 5 studies whether our results are robust to various measures for working capital policy and return volatility. Section 6 concludes our findings.

2. Related Literature and Hypothesis Development

To implement an aggressive working capital policy, that is, to decrease the level of working capital, a manager will decrease receivables and inventory and increase payables. In other words, firms invest a minimum amount of money in short-term capital to keep them operating. Previous literature finds that firms with aggressive working capital policies have better operating performance (Shin & Soenen, 1998; Deloof, 2003). The idea is that an aggressively managed working capital policy can generate more cash flows and internal capital, which help firms reduce financing costs and enhance growth opportunities. However, a tightened working capital policy may create some uncertainties for firms, such as a potential reduction in sales and increased levels of cash flow uncertainty. Gryglewicz (2011) demonstrates that continuous liquidity shocks affect a firm’s level of solvency, and solvency levels, in turn, have an impact on this firm’s probability of default. In addition, return volatility is related to the concern of liquidity uncertainty. Therefore, it is likely that firm performance may be negatively impacted by the aggressively managed working capital because increased return volatility can lead to unintended financial costs to the firms.

While it is not clear whether working capital policy has an impact on the return volatility, a conservative working capital management policy has three distinct features—credit insurance, R&D smoothing, and a buffer of cash reserves (Fazzari & Petersen, 1993; Hall & Kruiniker, 1995; Hall, 2002; Ding et al., 2013). We reason that all these features can reduce the probabilities of liquidation and make the costs of bankruptcy negligible, maintain stable levels of R&D activities, and smooth out short-term fluctuations in cash flows. Moreover, each individual component of working capital also has an impact on sales uncertainty. In the previous literature, any changes to the uncertainty of sales volume will have a direct effect on the cash flow volatility, especially for the stock return volatility (Ang et al., 2006; Wei & Zhang, 2006; Irvine & Pontiff, 2009; Gryglewicz, 2011). Finally, a conservative working capital policy is associated with longer cash conversion cycles, which are reflective of slower information flow for investors, resulting in less informative repricing (Ross, 1989; Glosten & Milgrom, 1985; French & Roll, 1986). Therefore, an aggressively managed working capital can increase cash flow volatility. We detail the rationale to reach our hypothesis below.

A priori, high levels of working capital ensure credit quality. Erel et al. (2015) document that investment in risk capital guarantees debt obligations and retains the firm’s credit scores from credit rating agencies. More risk capital assures credit-sensitive debt holders so that they will not impose monitoring costs or extra risk-bearing costs on the firms (also see Rampini & Viswanathan, 2013). This will reduce default risk and relax financial constraints. They propose that cash, collateral, line of credit, and insurance purchases are good examples of risk capital. Working capital can work as risk capital through two channels—cash and collateral. Working capital (account receivables and inventories) is cash-equivalent assets because it can be easily converted to cash through factoring with some discount on the face value of the assets (Mian & Smith, 1992). Moreover, working capital can be pledged as collateral to absorb losses for debt holders. A higher level of working capital helps firms manage financing and is related to better credit quality. Creditors usually are inclined to avoid lending to a firm with a low level of working capital because the amount of working capital influences a firm’s ability to meet its short-term obligations. Therefore, when dealing with firms with tightened working capital, creditors may charge higher interest rates, which results in an increase of uncertainty in the operating costs.

Second, higher levels of working capital can be used to smooth R&D and fixed investments. Comin and Philippon (2006) argue that firms’ return volatility is positively associated with R&D activities. Brown and Petersen (2011) demonstrate that cash holdings are one of the important tools for firms to finance their R&D expenditures, and firms rely on cash to smooth R&D investments. Fazzari and Petersen (1993) and Ding et al. (2013) find that high levels of working capital can be used as a short-term capital for firms to smooth fixed investments and enable them to alleviate their financial constraints in order to sustain sales growth. Lastly, working capital serves as a buffer to reduce the influence of cash flow fluctuation on a firm’s value. Hall and Kruiniker (1995) argue that working capital is a good measure of a firm’s operating liquidity. If the firm has a higher level of working capital, it has the advantage of accessing cheaper funds or borrowing at favorable interest rates so that stable cash flows can be achieved. Koijen and Van Nieuwerburgh (2011) document that stock prices usually move with fundamentals, and cash flow volatility is positively correlated with stock return volatility (also see Lustig & Van Nieuwerburgh, 2008). When time periods are extended to infinity, stock return volatility is essentially the volatility of cash flows.

Each component of aggressive working capital, namely decreased receivables and inventory, as well as increased payables, also has an impact on cash flow volatility for several reasons. First, reducing accounts receivable by adopting strict collection policies and restricting sales credits could lead to higher asymmetric information about product quality, greater customer financing frictions, and weak customer relationships, thus increasing sales uncertainty. Decreasing inventory also increases the probability that firms lose sales and miss growth opportunities due to running out of stock (see, for example, Long et al., 1993; Deloof & Jegers, 1996; Petersen & Rajan, 1997; Molina & Preve, 2009; Hill et al., 2012). Emery (1987) demonstrates that extending trade credit to customers reduces costs in the inventory and production pertaining to uncertain sales. Moreover, trade credit usually has a much shorter maturity and is subject to a supplier’s ability to access the capital market and institutional loans. Thus, increasing accounts payable may lead to costly financing, higher exposure to interest-rate risk, and unreliable funding sources, resulting in higher uncertainty of costs (e.g., Burkart & Ellingsen, 2004; Atanasova, 2007; Love et al., 2007; Ehrhardt & Brigham, 2008).4 All the uncertainties mentioned above are expected to increase cash flow volatility for aggressive working capital policies.

The arguments above develop the direct relation between conservative working capital and lower levels of stock return volatility. However, there is also one indirect effect strengthening the relation between working capital and return volatility. That is, an aggressive working capital policy is associated with shorter cash conversion cycles, which lead to more information flows; and more information available to the capital market is correlated with higher return volatility because informed trading gives rise to stock return volatility (Ross, 1989; Glosten & Milgrom, 1985; French & Roll, 1986; Lang & Lundholm, 1993; Bushee & Noe, 2000). Roll (1988) further argues that this information might be reflected in idiosyncratic volatility because information collected by investors is usually private information, and this information is incorporated into stock prices in idiosyncratic volatility. Bushee and Noe (2000) support this argument and provide evidence to show that better information disclosure affects institutional investors’ trading behaviors and induces higher levels of return volatility. Mihov and Naranjo (2017) document that firms with more concentrated customer bases are associated with higher idiosyncratic volatility, and such firm-specific return shocks can be smoothed out when firms have diversified customer bases that consist of many clients accounting for sales. Durnev et al. (2003) show that firms with higher levels of idiosyncratic volatility have better future operating performance. They further demonstrate that this higher future operating performance is related to better current stock returns, which imply that current returns reflect information about future earnings. Based upon the above discussion, our hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis.

Ceteris paribus, firms with aggressive working capital management policy have greater return volatility.

We note that there may exist other factors that drive our results. In particular, financially distressed firms tend to adopt more aggressive working capital policies in order to preserve cash. To mitigate this issue, we control for book-to-market ratio, market adjusted return, interest coverage, and leverage ratio in our regression analyses. We further exclude firms under financial distress from the sample to repeat our hypothesis tests. We also group firms into terciles according to their sales growth and rerun our hypothesis test in each of the firm groups. Since firms in financial distress are inclined to have weak operating performance, we expect that the link between aggressively managed working capital policy and greater return volatility will disappear after controlling for sales growth if our findings are mainly driven by financially distressed firms. Otherwise, if our findings are still evident across all these settings, the results do not appear to be sensitive to firms in financial distress.

3. Data and Sample Description

Our sample comes from several sources: (i) stock returns data from CRSP daily and monthly return files; and (ii) accounting information from the Compustat industrial annual file. Industry definition is from Fama and French’s (1997) 48-industry classification. The sample consists of all NYSE-, AMEX-, and NASDAQ-listed stocks that have complete information from the two major data sources (CRSP return files and Compustat accounting information) for the period 1991 to 2010. We also exclude firm-years that have negative sales and total assets or have a missing value for key variables, such as return volatility and measures for working capital policy, due to insufficient observations to compute these variables. To mitigate the potential impact of outliers on our results, variables are winsorized at the top and bottom 1% level of their respective distributions. Financial firms (SIC between 6000 and 6999), utilities firms (SIC between 4900 and 4999), foreign governments (SIC 8888), and international affairs and non-operating establishments (SIC higher than 9000) are excluded from the sample. Our final main sample is comprised of 84,900 firm-year observations and 42 industries.5 However, the sample sizes in certain multivariate analyses and robustness checks may vary due to the availability of information for some control variables.

3.1. Measures for Working Capital Policy and Return Volatility

We employ several different approaches to measure working capital policy. The main measure in this study for the working capital policy (WCP) is the working capital requirement to sales ratio, which is defined as:

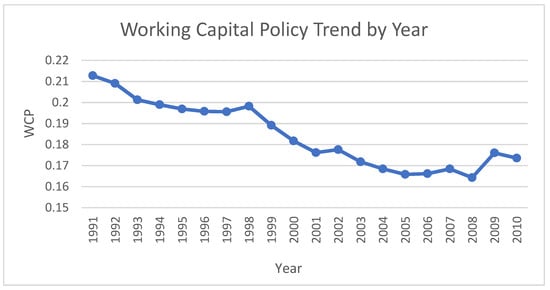

The lower a firm’s WCP, the more aggressive is its working capital management policy. There are several benefits for using this measure as a proxy for working capital policy. First, this measure focuses on the operating components of working capital. Previous literature generally defines working capital as current assets minus current liabilities. As Hawawini et al. (1986) argue, some components in this measure are not related to a firm’s daily operations and, therefore, should not be treated as a part of working capital for a firm.6 Since WCP is working capital requirement scaled by sales, it specifies the amount of working capital required for each dollar of goods sold. It is a better representation of a working capital policy for a firm. Second, the measure also captures the spirit of cash conversion cycle. Third, this measure is comprehensive because it takes into account not only receivables and payables, but also inventory, which is vital for a firm’s operation. Lastly, this measure is comparable to the ones used in practice by practitioners.7 Figure 1 depicts the average WCP over the years. The WCP values show a gradual decline over time, indicating a trend that firms’ choice to adopt more aggressive working capital policy.

Figure 1.

Trend of working capital policy over the years.

Shulman and Cox (1985) define working capital requirement (WCR) as current assets net of cash minus current liabilities net of notes payable and current long-term debt due.8 We scale the WCR by sales for consistency and note it includes items such as prepaid expenses that may not fully represent a firm’s operating working capital (Hill et al., 2010). To confirm the robustness of our findings and capture managerial decisions on working capital, we use net trade credit (NTC) as defined by Love et al. (2007).

For the first measure of return volatility, we follow Sias (1996) and Bushee and Noe (2000) to define return volatility as the log of standard deviation of daily returns during a one-year period. To ensure the quality of the measure, a firm must have a minimum of 125 daily return data for a year to compute its volatility.9 Another set of return volatility measures comes from Bae et al. (2004) and French et al. (1987). The first measure is denoted as AvgLnr2 and the second is denoted as AvgSqLnr. Formally, they are defined as:

where rt is daily return and n is the number of trading days in a year. As a robustness check, we also calculate return volatility by using monthly returns to substitute for daily returns.

3.2. Control Variables and Regression Specifications

Following previous studies, we control for several variables that may affect the return volatility. The control variables include:

- Firm size (Size): average log of the monthly market value of equity for a one-year period.

- Liquidity (Tvol): average monthly trading volume divided by total shares outstanding over a one-year period.

- Book-to-market ratio (BM): book value divided by market value.

- Interest coverage (IntCov): ratio of EBITDA to interest expenses.

- Leverage (Leverage): ratio of total debt to total assets.

- Sales growth rate (SaleGrowth): sales growth between year t and t − 1 (Salest/Salest−1).

- Market risk adjusted return (Mret): market model’s alpha using daily stock returns over a year.

When calculating market risk adjusted return, our proxies for monthly and daily factors, such as market return and risk free rate, are similar to those in Fama and French (1993).10 Accounting-based control variables are calculated using the accounting information from the fiscal year ended before June 30 of the year.

Sias (1996) shows that firm size has a negative effect on return volatility, yet better stock performance and higher institutional ownership have a positive effect on the return volatility. Bae et al. (2004) demonstrate that firm size and stock turnover have a significant impact on the return volatility. Considering liquidity’s influence on institutional holdings (Gompers & Metrick, 2001), we control for stock trading volume and exclude institutional ownership to prevent multicollinearity. Molina and Preve (2009) show that a firm’s financial health, indicated by interest coverage and leverage ratio, affects its trade receivables policy. To address stock return volatility among financially distressed firms, we also include sales growth as it affects trade receivables and may drive our results.

Regressions in this study are generally defined as:

The variables date in the Compustat data is used to align other elements calculated from CRSP and Compustat data. To explore the relation between future return volatility and current working capital policy, we also compute Volatility using one-year data after the data date. We implement both Fama-MacBeth regression and panel regression with clustered standard error corrected at firm level (fixed effect regression). We also control for year fixed effects (Petersen, 2009).

Table 1 presents the summary statistics of distributions of return volatility, working capital policy, and each control variable in Panel A, as well as the Pearson cross-correlation coefficients of the variables used in this study in Panel B. In Panel A, Volatility has an average of −3.280 and a standard deviation of 0.560, and WCP has an average of 0.179 and a standard deviation of 0.294. Firms, on average, have a size (Size) of 166.542 million, turnover ratio (Tvol) of 1.372, book-to-market ratio (BM) of 0.700, interest coverage (IntCov) of 24.216, leverage ratio (Leverage) of 0.216, sales growth (SaleGrowth) of 1.207 (or 20.7%), and daily market risk adjusted return (Mret) of 0.001 (or 0.1%). It is interesting to note that the interest coverage has a large standard deviation of 191.411. This indicates some firms hold a lot of cash in hand and do not borrow money, for instance, Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corporation. Since Volatility is calculated in log, it is not surprising that the value of Volatility is, in general, negative.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of main variables. Panel A reports the summary of return volatility (Volatility) and working capital policy measure (WCP), as well as main control variables, for 84,900 firm-year observations from 1991 to 2010. Panel B of this table provides time-series averages of the correlation between each of the two variables. Control variables include firm size in log (Size), trading volume divided by total shares outstanding (Tvol), book-to-market ratio (BM), interest coverage ratio (IntCov), ratio of total debt to total assets (Leverage), sales growth (SaleGrowth), and market risk adjusted return (Mret). WCP is calculated as (receivables + inventory-payables)/sales. Return volatility is the log of standard deviation of daily returns over a year. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

In Panel B, all variables are highly correlated with our return volatility measure, except leverage. The correlation between firm size and return volatility is especially high and negative. This indicates that large firms experience less return volatility, and there is a significant difference in return volatility between large and small firms. The correlation coefficients between WCP and other variables vary from −0.045 (WCP and SaleGrowth) to 0.079 (WCP and BM), implying that firms with relatively high sales growth tend to manage working capital more aggressively and value firms have a more conservative working capital policy. The correlations between the control variables and our main measure for working capital policy (WCP) are moderately low, suggesting no evidence of multicollinearity. Thus, our findings for the relation between return volatility and WCP are less likely affected by the multicollinearity problem.

4. Is Working Capital Policy Related to Return Volatility?

The management of a working capital policy can be classified as either conservative, moderate, or aggressive. While the conventional thinking is that an aggressively managed working policy is preferable, there may be some costs associated with the practice. Therefore, less aggressive policies are still used to manage working capital by firms. In this study, we use the risk-return framework by incorporating the potential cost (return volatility) associated with working capital policy to explore whether the adoption of an aggressive working capital policy is superior to others.

4.1. Regression Analyses by Year and by Industry

We investigate the relation between a firm’s working capital policy and its return volatility using regression analyses. Following Sias (1996), we control for firm size since large stocks may experience less return volatility. Considering that trading volume may also have a significant impact on the return volatility, as Bae et al. (2004) have documented, we add trading volume as a control variable. Given that macroeconomic conditions varied during our long sample period, we run year-by-year regressions to explore whether these conditions have different impacts on the relationship between volatility and working capital policy over time.

As reported in Table 2, working capital policy (WCP) is negatively and significantly related to return volatility, and the relation is stable over time. The overall average of WCP for the whole sample period is −0.155, while the average for the period from 1991 to 2007 is −0.160. It is fair to say that the financial crisis in 2008 has little impact on our findings—aggressive working capital policy is associated with higher levels of return volatility. Consistent with existing studies, firm size has a strong negative effect, and trading volume has a positive effect on the return volatility.

Table 2.

Relation between working capital policy and return volatility across years. This table reports the contemporaneous relation between working capital management policy and return volatility by year with regression estimates of the following model: , where the dependent variable is the return volatility (Vol) and the variable of interest is the measure of working capital policy (WCP). ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

Hawawini et al. (1986) provide evidence to show that the type of industry affects its working capital management practice. We next examine the relation between WCP and return volatility by industry using Fama and French’s (1997) 48-industry classification system to group firms. To ensure proper sample size in our regression analyses, we set the minimum number of firms in each industry to be 12 for any given sample year. Table 3 reports the results. Fama-MacBeth regressions are used to adjust time-series correlation.

Table 3.

Relation between working capital policy and return volatility by industry. This table reports the Fama-MacBeth regressions of return volatility on working capital policy (WCP) and control variables of firm size (Size) and trading volume (Tvol) by industry. Regressions are specified in Table 2. To ensure the quality of regression estimates, an industry in this table must have a minimum of 12 or 36 firm observations for any given year (Min N.). Coefficient estimates are reported with their corresponding t-statistics. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

In Table 3, the Apparel industry has the most negative and significant coefficient loading (−0.801) with WCP, while Restaurants, Hotels, and Motels industry has the highest positive coefficient with WCP (0.191), but is not statistically significant. Among all 32 industries, 18 industries have negative and significant coefficients with WCP, and two industries (Automobiles and Trucks, and Machinery) have positive and significant coefficients. When we use a stricter rule, such as a minimum of 36 firm observations in an industry for any given year, 14 out of 25 industries have negative and significant coefficients, and two industries still have positive and significant coefficients for WCP. The negative relation between working capital policy and return volatility applies to most industries, even though firms from different industries may adopt different working capital policies.11

4.2. Regressions with More Control Variables

Existing literature documents that book-to-market ratio and stock performance are related to return volatility. Financial conditions and sales growth have a large effect on the working capital policy and the use of trade credit (Petersen & Rajan, 1997; Molina & Preve, 2009; Hill et al., 2010). We explore the relation between working capital policies and return volatility by controlling for other factors that may affect volatility.

In Table 4, the dependent variable is return volatility calculated with daily returns in Panel A and with monthly returns in Panel B. In Panel A, WCP is negatively correlated with return volatility, even after controlling for a broader range of control variables. The coefficients of WCP across models are all significant, indicating that firms with aggressive working capital policy have a higher level of return volatility—one standard deviation decrease in the WCP will result in an increase of return volatility in 4.45%, 3.38%, 3.32%, 3.24%, 2.53%, and 2.87% for Models 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively. Fixed effect regressions also provide similar results.

Table 4.

Contemporaneous relation between return volatility and working capital policy. The dependent variable is return volatility calculated with daily returns in Panel A and with monthly returns in Panel B. Each panel also reports estimations of both Fama-MacBeth regressions and fixed effect regressions. Regressions are specified in Table 2, with additional control variables of book-to-market ratio (BM), interest coverage (IntCov), total debt-to-total assets ratio (Leverage), sales growth (SaleGrowth), market-adjusted return (Mret), and short-term debt-to-sales ratio (Sdebt). ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

Considering that daily stock returns may be noisier, we also use monthly returns to calculate return volatility. In unreported tables, we further use weekly returns to calculate return volatility. The results are still qualitatively similar. In the interest of space, we only report results using monthly returns. From Panel B, WCP is negatively associated with return volatility across all models, indicating that firms with higher investment in working capital experience lower return volatility.

We next look into the question concerning how aggressively managed working capital policy affects return volatility. Karolyi (2001) argues that a reasonable risk is desirable but that excess risk should be minimized. If aggressive working capital policy affects return volatility through increasing beta, investors will be rewarded with higher returns. However, if aggressively managed working capital affects the return volatility through an increase in idiosyncratic risk, investors will not benefit from bearing such risk because it adversely affects stock returns. Both firms and investors will experience additional asymmetric information induced by the increase in firm-specific risk.

4.3. Systematic (Beta) or Unsystematic (Idiosyncratic) Risk

If aggressive working capital policy increases uncertainty for firms, it is noteworthy to investigate through which channel—systematic and/or idiosyncratic risk—the aggressively managed working capital affects the return volatility. Idiosyncratic risk is measured as the standard deviation of the residuals from the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). We require at least 125 non-missing daily return observations during the year in calculating the standard deviation. Additionally, we estimate beta and idiosyncratic risk using three-year (t − 1, t, t + 1) monthly returns, requiring a minimum of 24 observations. Table 5 reports the relation between beta and WCP, and between idiosyncratic risk and WCP. We also control all variables included in Model 6 of Table 4. To save space, we only show the results on WCP, the variable of interest.

Table 5.

Market and firm-specific risk. This table presents the relation between working capital policy and risk with regression estimates of the following model: , where the dependent variable is the risk- market risk (Beta) and idiosyncratic risk (Idio Risk), and WCP is the measure of working capital policy. Control variables include variables used in Model 6 of Table 4. In Panel A, beta and idiosyncratic risk are calculated by using daily returns over a year with the same ending date of annual financial report (with a minimum of 125 observations). In Panel B, monthly returns in year (t − 1, t, t + 1) (with a minimum of 24 observations) are used to calculate dependent variables. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

In Panel A, when idiosyncratic risk is the dependent variable, the coefficient of the WCP is negative and significant, indicating that firms with aggressive working capital policy tend to have a higher level of firm specific risk. However, when systematic risk is the dependent variable, WCP is positively and significantly associated with beta. This implies that firms with conservative working capital policy have greater systematic risk. It is noteworthy that under the fixed effect regression analysis, the coefficient loading on WCP becomes insignificant after we control for industry and year fixed effects and correct for firm-level clustered standard errors. That is, the working capital policy has no significant effect on beta. This result suggests that aggressive working capital policy affects return volatility mainly through idiosyncratic risk.

4.4. Changes in Working Capital Policy vs. Changes in Return Volatility

The previous findings have established the link between working capital policy and stock return volatility. Since we are testing the contemporaneous relation, it may be argued that working capital policy and return volatility are simultaneously determined. For example, firms that are vulnerable to financial crisis may have a higher level of return volatility and aggressive working capital policy during a financial event. Moreover, it is likely that the change in a firm’s stock return volatility may lead to a contemporaneous and/or a lagged shift in its working capital policy. On the other hand, it is also possible that a shift in a firm’s working capital practice may result in a concurrent and/or a lagged increase (or decrease) of its stock return volatility. In this subsection, we designed the following tests to study these relationships:

In Equation (5), we explore whether the change in working capital policy (ΔWCP), and the lagged working capital policy (WCPt−1), would have an impact on current (or future) stock return volatility. Additionally, in Equation (6), we study if the change in stock volatility (ΔVolatility) and the lagged level of return volatility (Volatilityt−1) would affect the current (or future) working capital policy. The control variables used in Equations (5) and (6) are the same control variables in Model 6 of Table 4 in year t. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Changes in working capital policy vs. changes in return volatility. Dependent variables are return volatility and the measure of working capital policy (WCP) with regression estimates of the following models: , , where ΔWCPt = WCPt − WCPt−1 and ΔVolatilityt = Volatilityt − Volatilityt−1. Control variables include variables used in Model 6 of Table 4. t-statistics are calculated based on clustered firm-level heteroscedasticity-adjusted standard errors and controlling for industry and year fixed effects. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

The results in Panel A use the Fama-Macbeth regressions to show that coefficients associated with changes in WCP (ΔWCP) negatively and significantly affect the current and future levels of return volatility. Lagged WCP (WCPt−1) also predicts the current and future return volatility levels. On the contrary, the changes of return volatility (ΔVolatility) do not have a statistically significant impact on the current and future working capital practices. Similar results are confirmed using the fixed effect regressions, as shown in Panel B of Table 6.

Table 6 shows that changes in a firm’s working capital policy and return volatility are not necessarily simultaneous. A shift to a more aggressive working capital policy immediately increases return volatility, with effects persisting into the future. However, changes in return volatility do not immediately impact working capital policy, though the level of volatility does negatively affect future policy. Hence, a switch to a more aggressive working capital policy may serve as a signal and, thus, has important implications for investors and managers.

5. Robustness Checks and Additional Analyses

5.1. Using Various Measures for Working Capital Policies

We test the robustness of our main results using several popular working capital policy measures. Traditionally, a firm’s investment in working capital is measured as the difference between current assets and current liabilities. However, many researchers criticize this concept of working capital by arguing that some components are not related to the firm’s operation (e.g., see, Hawawini et al., 1986). Shulman and Cox (1985) define working capital requirement as current assets net of cash minus current liabilities net of notes payable and current long-term debt due. We follow this definition to calculate the measure (WCR). We also apply the definition from Hawawini et al. (1986) as another proxy for working capital policy. Since the results from both are similar, we do not report the latter in the paper.

To further validate our findings and capture a manager’s intention about working capital policy, we use net trade credit (NTC) as a proxy for the working capital policy (Love et al., 2007). A tight net trade credit or smaller value of net trade credit indicates that firms are inclined to have an aggressive working capital policy. Results are reported in Panel A of Table 7. The findings are consistent confirming that our primary conclusion holds across different definitions of working capital policy.

Table 7.

Robustness check with various measures for working capital policy and return volatility. The table reports results using various measures for working capital policy and return volatility to run both Fama-MacBeth regressions (columns 1 and 3) and fixed effect regressions (columns 2 and 4). The regression model is specified in Table 2. Control variables include variables used in Model 6 of Table 4. t-statistics reported with fixed effect regressions are calculated based on clustered firm-level heteroscedasticity-adjusted standard errors and incorporate industry and year fixed effects. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

5.2. Relation Between Working Capital Policy and Future Return Volatility

To further address the endogeneity issue, we regress return volatility in year t + 1 against WCP and control variables in year t.12 Panel B of Table 7 reports the results. The negative relation between WCP and return volatility still exists and is significant at conventional levels. Considering that investors may need some time to digest accounting information, we also set July 1st as the start date to calculate return volatility for the future one year. The results are similar and consistent with our previous findings.

5.3. Using Various Measures for Return Volatility

Bae et al. (2004) and French et al. (1987) implement two different measures for return volatility. To explore whether our results are sensitive to the definition of return volatility, we also use these two measures and report the results in Panel C and Panel D of Table 7. The coefficients of WCP are generally negative and significant across all models. Thus, our conclusion that aggressive working capital policy is associated with volatile stock returns still holds.

5.4. Deleting Financially Distressed Firms

Firms in financial distress tend to tighten their accounts receivable policy and increase accounts payable to boost cash. Since firms in financial distress tend to have volatile stock returns, it is possible that our results are mostly driven by this type of firm. We repeat our analysis from Table 4 by first excluding firms in financial distress and then excluding firms in partial financial distress. Molina and Preve (2009) combine interest coverage and leverage ratio as a major proxy for the financial distress—distressed firms are firms with (i) interest coverage ratio less than 0.8 for one year, or less than 1 for two consecutive years, and (ii) leverage ratio in the top two deciles. We further define partially distressed firms as those satisfying either one of these two conditions. Panel A of Table 8 presents the results. The coefficients of WCP are still negative and significant when we exclude distressed firms. Thus, our main results are not driven by the behavior of financially distressed firms.

Table 8.

Robustness check by excluding financially distressed firms and by controlling for sales growth. This table reports the relation between working capital policy (WCP) and return volatility (i) by excluding financial distress firms in Panel A and (ii) by grouping firms into high-, mid- and low-levels of sales growth in Panel B. ***, **, and * denote significance at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively.

5.5. Sorting Firms into Groups by Sales Growth

Since high sales growth is associated with reduced accounts receivable and aggressive working capital policy, our findings may be driven by the behavior of high-sales-growth firms. If this conjecture is true, we expect that our findings will be less robust when firms are split into groups with different levels of sales growth. To test this hypothesis, we examine the association between WCP and return volatility in three firm-year categories: high-, mid-, and low-growth firms based on their sales growth rates. The results are reported in Panel B of Table 8.

Consistent with our previous findings, the coefficients of WCP are still significantly negative in each growth category, i.e., firms with aggressive working capital policy tend to have greater stock return volatility regardless of their sales growth opportunity. Considering that there is a time lag for firms to adjust their working capital policy in response to their high sales growth, we also use their sales growth in the previous year to group firms into three levels. The results (not tabulated) are still qualitatively similar.

6. Conclusions

Previous literature and mass media usually suggest that firms should adopt a more aggressively managed working capital policy because it may benefit both shareholders and corporations. Given the development of global supply chain networks, just-in-time inventory models, electronic payment systems, electronic data interchange, and financial information technology systems, firm managers are supposed to be able to develop a more efficient working capital policy to reduce unnecessary investment in the working capital. Nonetheless, several survey articles indicate that U.S. firms still have billions of dollars tied up in excess working capital. This paper is an attempt to shed some light on this puzzle by studying why many firms still implement a conservative working capital management practice instead of pursuing a more aggressive working capital strategy. Molina and Preve (2009) provide a possible explanation by claiming that a significant reduction in trade receivables actually hurts a firm’s performance. We provide additional evidence to show that a tightened working capital increases uncertainty and causes greater return volatility. Increased return volatility leads to more expensive financing options and higher financing costs. Greater return volatility also implies higher asymmetric information between the firm and its investors. Little attention has been given to investigating the relationship between a firm’s working capital policy and its stock return behavior.

In this paper, we focus on operating components of working capital and find that firms with an aggressive working capital policy tend to exhibit a higher level of return volatility. Our findings remain consistent and robust even after controlling for time, industry, financial health, and sales growth. We also show that aggressive working capital policy affects return volatility through idiosyncratic risk, supporting Sartoris and Hill’s (1983) theory that tightened working capital increases uncertainty.

We further find that both changes and levels of working capital policy affect contemporaneous and future return volatility. However, changes in return volatility do not have a significant effect on working capital policy. This evidence indicates that the working capital policy has a stronger and more direct effect on the return volatility. While the change of return volatility does not affect a firm’s working capital policy, the level of return volatility will have an impact on the working capital management policy in the future. It implies that working capital policies are often influenced by internal considerations (e.g., liquidity needs, operational efficiency, credit terms) rather than reacting to external volatility. Firms may not adjust their working capital decisions in direct response to changes in market fluctuations. However, firm managers need to be cautious when adopting aggressive working capital policies, as these can lead to sustained stock return volatility. For investors, the results provide evidence that working capital management can serve as an indicator of financial risk, helping them assess firms’ risk exposure and make more informed investment decisions. Hence, a switch to a more aggressive working capital policy may serve as a signal and, thus, has important implications for investors and firm managers. The transmission mechanism between the working capital policies and idiosyncratic risk and how a potential investor could use this signal to reduce the overall risk are beyond the scope of this paper and need exploration in subsequent studies. The overall evidence suggests that firm managers must weigh the potential benefits of aggressively managed working capital policy against the potential costs associated with higher return volatility when deciding on their working capital management policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.; methodology, J.C.; validation, J.C. and K.D.; formal analysis, J.C.; writing—original draft, J.C.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.C. and J.C.; visualization, J.C. and K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data was obtained through academic subscriptions obtained by our institution, and the authors cannot, under the terms of the agreements, have the data sets available for deposit.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In general, the management approach toward working capital can be classified as conservative, moderate and aggressive based on how a firm’s working capital policy differs as compared to norms. See Ehrhardt and Brigham (2008) for a discussion. |

| 2 | The zero working capital management pioneered by companies such as American Standard, General Electric and Campbell Soup stems from the concept of aggressively managed working capital policy that managers can use payables to finance receivables and inventory. Brigham and Daves (2007) document the advantages of this policy and show “a movement toward this goal not only generates cash but also speeds up production and helps businesses make more timely deliveries and operate more efficiently”. |

| 3 | Ernst & Young (2011) also reports that “the surveyed companies still have an aggregate total of up to US$1.1 trillion in cash unnecessarily tied up in WC. This is equivalent to nearly 7% of their sales”. |

| 4 | For example, Ehrhardt and Brigham (2008) estimate the nominal annual rate is 37.2% for a credit of 2/10, net 30. This rate is much higher than borrowing from banks. |

| 5 | Sample includes industry 1 (Agriculture) to industry 43 (Restaurants, Hotels, Motels) except industry 31 (Utilities) from Fama and French’s (1997) industry classification. Industry 44 through industry 48 (Banking, Insurance, Real Estate, Trading, and almost nothing) are also excluded from our sample. |

| 6 | Hawawini et al. (1986) regard these components (items such as cash and marketable securities, and short-term borrowings) as ‘purely financial decisions’. |

| 7 | One common measure for the working capital in the reports from REL and Ernst & Young is defined as (receivables+inventory-payables)/revenue. |

| 8 | Hawawini et al. (1986) compute working capital requirement as current assets minus current liabilities minus cash and marketable securities plus short term debt. This definition is generally consistent with Shulman and Cox’s (1985) definition for working capital requirement. We also substitute short term debt in Compustat for notes payable and current long-term debt due to find working capital requirement (WCR). The results are generally consistent and robust. |

| 9 | In the paper, if not specified, we refer to return volatility (Volatility) as the measure defined by Sias (1996) and Bushee and Noe (2000). |

| 10 | We thank Kenneth French for providing us with these data. The data are available on French’s website. |

| 11 | When we include all industries into the sample, there are 21 out of 42 industries having a negative and significant coefficient on WCP; and two industries having a positive and significant coefficient on WCP. |

| 12 | For example, the return volatility is measured over one year after the datadate in Compustat files and the control variables and WCP are obtained by using accounting information in the year before the datadate. |

References

- Aktas, N., Croci, E., Ozbas, O., & Petmezas, D. (2021). Executive compensation and deployment of corporate resources: Evidence from working capital. Review of Corporate Finance, 1, 43–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A., Hodrick, R., Xing, Y., & Zhang, X. (2006). The cross-section of volatility and expected returns. Journal of Finance, 51, 259–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasova, C. (2007). Access to institutional finance and the use of trade credit. Financial Management, 36, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.-H., Chan, K., & Ng, A. (2004). Investibility and return volatility. Journal of Financial Economics, 71, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, S. T., Pasquariello, P., & Guojun Wu, G. (2009). Does asymmetric information drive capital structure decisions? Review of Financial Studies, 22, 3211–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, E. F., & Daves, P. R. (2007). Intermediate financial management (9th ed.). Thomson/South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J. R., & Petersen, B. C. (2011). Cash holdings and R&D smoothing. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17, 694–709. [Google Scholar]

- Burkart, M., & Ellingsen, T. (2004). In-kind finance: A theory of trade credit. The American Economic Review, 94, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushee, B. J., & Noe, C. F. (2000). Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y., Lettau, M., Malkiel, B., & Xu, Y. (2023). Idiosyncratic equity volatility two decades later. Critical Finance Review, 12, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, D. A., & Philippon, T. (2006). The rise in firm-level volatility: Causes and consequences (NBER Working Paper). The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deloof, M. (2003). Does working capital management affect profitability of Belgian firms? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30, 573–587. [Google Scholar]

- Deloof, M., & Jegers, M. (1996). Trade credit, product quality, and intragroup trade: Some European evidence. Financial Management, 25, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S., Guariglia, A., & Knight, J. (2013). Investment and financing constraints in China: Does working capital management make a difference? Journal of Banking and Finance, 37, 1490–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnev, A., Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Zarowin, P. (2003). Does greater firm-specific return variation mean more or less informed stock pricing? Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 797–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, M. C., & Brigham, E. F. (2008). Corporate finance: A focused approach (3rd ed.). South-Western Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, G. (1987). An optimal financial response to variable demand. Journal of Financial Quantitative Analysis, 22, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, I., Myers, S. C., & Read, J. A. (2015). A theory of risk capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 118, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst & Young. (2011). All tied up—Working capital management report 2011. EYGM Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33, 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzari, S. M., & Petersen, B. C. (1993). Working capital and fixed investment: New evidence on financing constraints. RAND Journal of Economics, 24, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbeck, G., Zhao, X., & Knoll, R. (2017). An analysis of working capital efficiency and shareholder return. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 48, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K. R., & Roll, R. (1986). Stock return variances: The arrival of information and the reaction of traders. Journal of Financial Economics, 17, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K. R., Schwert, G. W., & Stambaugh, R. F. (1987). Expected stock returns and volatility. Journal of Financial Economics, 19, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, L. R., & Milgrom, P. (1985). Bid, ask and transaction prices in a specialist market with heterogeneously informed traders. Journal of Financial Economics, 14, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompers, P. A., & Metrick, A. (2001). Institutional investors and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryglewicz, S. (2011). A theory of corporate financial decisions with liquidity and solvency concerns. Journal of Financial Economics, 99, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B. H. (2002). The financing of research and development. Review of Economic Policy, 18, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B. H., & Kruiniker, H. (1995). The role of working capital in the investment process (NBER Working Paper). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (2008). A theory of board control and size. Review of Financial Studies, 21, 1797–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawawini, G., Viallet, C., & Vora, A. (1986). Industry influence on corporate working capital decisions. Sloan Management Review, 27, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M. D., Kelly, G. W., & Highfield, M. J. (2010). Net operating working capital behavior: A first look. Financial Management, 39, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M. D., Kelly, G. W., & Lockhart, G. B. (2012). Shareholder returns from supplying trade credit. Financial Management, 41, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, P. J., & Pontiff, J. (2009). Idiosyncratic return volatility, cash flows, and product market competition. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 1149–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karolyi, G. A. (2001). Why stock return volatility really matters. In Strategic investor relations. Institutional Investor Journals Series. [Google Scholar]

- Koijen, R., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2011). Predictability of returns and cash flows. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 3, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1993). Cross-sectional determinants of analysts ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 31, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. S., Malitz, I. B., & Ravid, S. A. (1993). Trade credit, quality guarantees, and product marketability. Financial Management, 22, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, I., Preve, L. A., & Sarria-Allende, V. (2007). Trade credit and bank credit: Evidence from recent financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 369–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, H., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2008). The returns on human capital: Good news on wall street is bad news on main street. Review of Financial Studies, 21, 2097–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S., & Smith, C. (1992). Accounts receivable management policy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Finance, 47, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihov, A., & Naranjo, A. (2017). Customer-base concentration and the transmission of idiosyncratic volatility along the vertical chain. Journal of Empirical Finance, 40, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C. A., & Preve, L. A. (2009). Trade Receivables policy of distressed firms and its effect on the cost of financial distress. Financial Management, 38, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 435–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1997). Trade credit: Theories and evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 10, 661–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampini, A. A., & Viswanathan, S. (2013). Collateral and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 109, 466–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, R. (1988). R2. Journal of Finance, 25, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S. (1989). Information and volatility: The no-arbitrage martingale approach to timing and resolution irrelevancy. Journal of Finance, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sartoris, W. L., & Hill, N. C. (1983). A generalized cash flow approach to short-term financial decisions. Journal of Finance, 38, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.-H., & Soenen, L. (1998). Efficiency of working capital management and corporate profitability. Financial Practice and Education, 8, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, J. M., & Cox, R. A. K. (1985). An integrative approach to working capital management. Journal of Cash Management, 5, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sias, R. W. (1996). Volatility and the institutional investor. Financial Analysts Journal, 52, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hackett Group. (2023). The 2023 CFO/The Hackett group working capital scorecard. CFO Magazine. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S. X., & Zhang, C. (2006). Why did individual stocks become more volatile? Journal of Business, 79, 259–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).