Abstract

This study investigates how stakeholder pressures (SSTPR) prompt SMEs to perform green innovation (GRNI) activities by grounding the analysis exclusively in stakeholder theory. It employs a survey questionnaire to gather information from 141 top- and mid-level executives working in various SME manufacturing firms (listed in DSE, CSE, foreign SMEs) in Bangladesh. The structural equation modeling (SEM) technique is used to analyze data and test hypotheses. The study’s findings reveal that SSTPR, both primary and secondary, have a significant positive impact on the firm’s degree of GRNI. Moreover, it has also been found that environmental commitment (ENVC) has a positive moderating effect on the relation between stakeholder influences and GRNI. On the other hand, environmental ethics (ENVE) has a partial mediation impact on this relationship. The results shed light on the crucial role of stakeholder influence, ENVC, and ENVE in promoting GRNI behavior. These findings will fill knowledge gaps on the factors that drive SMEs’ investments in GRNIs with insightful implications for regulators, managers, and policymakers. This study also assists Bangladesh’s sustainable agenda by bolstering green and sustainable innovation activities.

Keywords:

stakeholder pressures (SSTPR); small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); green innovation (GRNI); environmental commitment (ENVC); environmental ethics (ENVE) JEL Classification:

M3; Q5; Q1

1. Introduction

In the face of intensifying climate challenges, ecological degradation, and growing demand for sustainable development, GRNI has emerged as a pivotal corporate strategy. It is increasingly recognized not only as a performance indicator but also as a catalyst for long-term business resilience (Hojnik et al., 2024), which involves developing and implementing environmentally sustainable technologies, processes, and practices that reduce ecological harm while strengthening competitive advantage (Ai et al., 2025). Once it was viewed as a cost burden, but now it is increasingly recognized for its ability to enhance efficiency, strengthen product value, and build stakeholder trust—often yielding benefits that surpass initial investments (Rubio-Andrés et al., 2023).

Stakeholder Theory provides a useful lens for understanding this complexity. It views firms as entities embedded within dynamic networks of stakeholders whose expectations, demands, and legitimacy pressures shape organizational behavior (Singh et al., 2021). SSTPR, whether regulatory, social expectations, or peer influence, can encourage firms to adopt green practices. However, the extent to which these pressures translate into substantive innovation depends on firms’ internal orientations (Rui & Lu, 2020). These inconsistencies highlight the need to examine the internal mechanisms through which external pressures become strategic environmental actions, as seen in developing countries. Hence, this study foregrounds two such mechanisms: ENVC and ENVE. These are not passive traits but dynamic organizational capacities that shape how firms respond to stakeholders. ENVC reflects the prioritization of ecological concerns in strategy, while ENVE refers to the values and norms guiding decision-making. Together, they determine whether SSTPR results in symbolic compliance or genuine transformation.

Despite growing interest in green and responsible innovation (GRNI), existing research leaves several critical questions insufficiently answered. While stakeholder theory assumes that firms respond rationally to the demands and expectations of salient actors, empirical evidence suggests that such pressures do not uniformly translate into proactive or transformative green behavior. In many cases, firms engage in symbolic compliance or superficial environmental reporting rather than genuine innovation, indicating that external pressure alone is an insufficient explanatory mechanism (Hasan & Al-Najjar, 2025; Islam, 2025; Qin et al., 2019). This inconsistency points to an underexplored internal dimension within stakeholder theory, such as the cognitive, ethical, and commitment-based filters through which organizations interpret and respond to stakeholder demands. Moreover, existing studies are heavily concentrated in large firms and developed institutional contexts, where legal enforcement, media scrutiny, and civil society activism are relatively strong. This creates systematic bias in the literature and limits theoretical generalizability. In contrast, in emerging economies such as Bangladesh, where regulatory enforcement is inconsistent, corruption may dilute formal institutional pressure, and informal networks often replace formal governance mechanisms; stakeholder influence may operate in fundamentally different ways. SMEs, in particular, lack structured sustainability systems, face severe resource constraints, and often rely on the personal values and ethics of owners or founders in decision-making (Kayani et al., 2023). Yet, this critical organizational segment remains significantly underrepresented in green innovation research. As a result, we know very little about how multiple and sometimes conflicting stakeholder pressures are navigated by SMEs operating under weak institutional conditions.

Previous research by Xie et al. (2024) and Shahzad et al. (2020) confirms that SSTPR can drive green innovation, but this study shows that its impact is highly context-dependent. In Bangladeshi SMEs, only primary stakeholders exert meaningful influence, while secondary stakeholders lack moderating power, even when firms have ENVC, revealing a clear hierarchy of stakeholder salience in weak institutional environments. The study’s key contribution is positioning ENVC as a strategic amplifier: committed firms interpret stakeholder demands as aligned with their own values and long-term goals, making them more willing and capable of converting pressure into genuine green innovation. In contrast, less-committed firms respond defensively or symbolically, treating sustainability as a compliance cost rather than an opportunity. Thus, the research refines and extends Stakeholder Theory by explaining when and why stakeholder pressure translates into meaningful innovation in an emerging economy context.

The remainder of this study is structured in this manner: The study begins by proposing various theoretical assumptions underpinning the stakeholder theory by evaluating our theoretical model using the regression analysis on a sample of 141 SMEs from Bangladesh. Additionally, considering the findings, theoretical and practical implications are addressed.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Stakeholder theory offers a foundational framework for understanding this process, as it conceptualizes firms not as isolated profit-maximizing entities but as actors embedded in networks of relationships whose survival and legitimacy depend on responding to multiple stakeholder expectations (Hannan & Freeman, 1984). Stakeholder demand does not originate from a single source. Rather, it emanates from multiple stakeholder groups who possess varying degrees of power, legitimacy, and urgency (Mitchell et al., 1997), which influence a firm’s strategic environmental management (Hasan & Al-Najjar, 2024). Clarkson (1995) classifies these groups into primary stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, employees, regulators, and investors, who are essential to a firm’s ongoing operations, and secondary stakeholders such as NGOs, media, and local communities who do not engage in direct transactions but can exert reputational and social influence. Theoretically, this distinction is important because it reflects different modes of influence. Primary stakeholders exercise formal, resource-based pressure through contracts, regulation, and market dependence, while secondary stakeholders apply informal, normative pressure through public opinion, activism, and social legitimacy. Together, these diverse pressures form a multi-dimensional construct of stakeholder pressure, justifying its treatment as a second-order variable composed of primary and secondary stakeholder influence.

While extensive research confirms that SSTPR can encourage environmental practices (Singh et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2024), findings remain inconsistent. In some contexts, firms engage in symbolic or compliant behavior rather than substantive innovation (Testa et al., 2018). This inconsistency suggests that external pressure alone is insufficient to guarantee genuine green innovation. Instead, the translation of stakeholder demands into GRNI depends on how firms interpret, internalize, and act upon these signals (Han et al., 2019). This points to the importance of internal cognitive and normative mechanisms specifically, ENVC and ENVE. Prior research on corporate environmental responsiveness, including the distinction between legitimation motives and internal values (e.g., Bansal & Roth, 2000), provides a useful foundation for linking stakeholder influence with internal ethical and strategic drivers. Positioning this framework within broader discussions of sustainability and ESG-oriented pressures further reinforces the relevance of stakeholder-driven green innovation beyond the SME context.

This internal and external interaction is especially relevant in weak-institutional contexts such as Bangladesh, where regulatory enforcement is fragmented and market structures are often informal. In such settings, external stakeholder pressure alone may lack the institutional strength needed to drive innovation unless it is supported by a strong internal orientation and ethical conviction. Despite this, little empirical research has examined how SSTPR, ENVC, and ENVE interact to shape GRNI in SMEs operating in such environments. Existing studies tend to focus either on external drivers or internal capabilities in isolation, leaving a gap in our understanding of their combined and conditional effects. By integrating SSTPR, ENVE, and ENVC within a single model, this study develops a more nuanced explanation of how stakeholder influence is translated into GRNI outcomes in resource-constrained firms. In doing so, it moves beyond traditional, linear interpretations of stakeholder theory and introduces an interactive mechanism through which both structural pressures and internal values jointly determine firms’ GRNI behavior.

2.2. SSTPR and ENVC

Primary stakeholders, due to their direct economic and regulatory influence, play a particularly dominant role in shaping firms’ environmental orientation. Simultaneously, secondary stakeholders—such as media or community organizations can shape public discourse and indirectly affect firms’ legitimacy. As SSTPR intensifies, both formal and informal expectations influence managerial decisions, fostering a stronger internal commitment to environmental sustainability. While earlier studies have revealed external factors of GRNI regarding a firm’s commitment, norms, and standards to the environment (Adomako et al., 2023; Rui & Lu, 2020), as well as impact on economic performance (Y. Wang et al., 2020), this study suggests how the SSTPR are likely to increase firms’ ENVC and impact on the GRNI adoption. Thus, we hypothesized that:

H1.

SSTPR has a positive impact on the firm’s ENVC.

H1a.

Primary stakeholder environmental pressures are positively related to a firm’s ENVC.

H1b.

Secondary stakeholder environmental pressures are positively related to a firm’s ENVC.

2.3. SSTPR and GRNI Practices

Stakeholder Theory also suggests that external pressure does not merely drive compliance but can stimulate strategic innovation. As stakeholders demand greener products, cleaner operations, and sustainable value chains, firms are incentivized to innovate to meet those expectations. For instance, empirical research indicates a positive relationship between SSTPR and environmental productivity (Murillo-Luna et al., 2008), and it demonstrates that the more the perceived green demands from primary and secondary stakeholders, the more likely enterprises are to raise their environmental consciousness and innovative behavior. This is because such pressure creates legitimacy concerns, strategic opportunities, and institutional expectations that firms must address to remain competitive and socially accepted. Firms that believe in GRNI strive to design products utilizing energy-efficient and recycled resources due to cost-effectiveness, eco-friendly practices, which act as a strategic response to stakeholder expectations, creating shared value for both the organization and society. Hence, Firms choose GRNI based on internal resources, structures, and fundamental competencies, while external forces push proactive, environmentally friendly behaviors (Fahlevi et al., 2023; Garcés-Ayerbe et al., 2019).

Hence, the study responds to the demand for more investigation (Rui & Lu, 2020; Xie et al., 2024) to demonstrate what pushes the SMEs to strive to be green-oriented firms through their actions responding to stakeholder ecological needs (Hasan et al., 2022). When stakeholders, especially those with institutional power, signal the importance of environmental performance, firms become more likely to respond through innovation that meets regulatory, social, and market expectations. Hence, this pressure acts as a catalyst, encouraging firms to integrate environmental concerns into product development and operational strategies. Following the earlier literature, we hypothesized that:

H2.

SSTPR are positively related to a firm’s degree of GRNI.

H2a.

Primary stakeholder environmental pressures are positively related to a firm’s degree of GRNI.

H2b.

Secondary stakeholder environmental pressures are positively related to a firm’s degree of GRNI.

2.4. ENVC and GRNI

ENVC reflects a firm’s internal prioritization of sustainability objectives and values (Adomako et al., 2023). Stakeholder Theory recognizes that internal actors, particularly top management, are also stakeholders whose values shape firm behavior. A strong ENVC from leadership influences how the organization allocates resources and pursues innovation to achieve sustainability goals. Firms with greater ENVC are more likely to proactively develop GRNIs, integrating environmental goals into core business processes. This commitment serves not only as a response to stakeholder demands but also as a foundation for continuous green transformation (Nguyen & Adomako, 2022). Hence, we hypothesized that:

H3.

ENVC is positively related to a firm’s degree of GRNI.

2.5. The Mediating Role of ENVE

ENVE reflect the moral values, principles, and beliefs that guide a firm’s perception of and response to ecological issues (X. Wang & Young, 2014). Within the stakeholder theory framework, organizations are not only influenced by external stakeholder demands but are also expected to internalize these expectations through a value-based lens, transforming pressure into principled action.

SSTPR often triggers not just strategic responses but also normative alignment, internalization of ethical values concerning environmental sustainability. ENVE acts as a moral and cognitive filter that shapes how firms internalize and respond to external SSTPR (Rui & Lu, 2020). While stakeholders may demand environmentally responsible actions, it is the ethical orientation of a firm that determines whether these demands are perceived as strategic opportunities or compliance obligations. When firms uphold strong ENVE, they are more likely to translate SSTPR into authentic GRNI rather than superficial responses. This ethical lens bridges the gap between external demands and internal strategic behavior, fostering initiative-taking innovation rooted in values rather than coercion. Thus, ENVE may mediate by converting external pressures into purposeful, value-driven environmental innovation. Hence, we hypothesized that:

H4.

The influence of SSTPR on the firm’s degree of GRNI is mediated by ENVE.

2.6. Moderating Role of ENVC

SSTPR, such as customer demand, regulatory mandates, or normative expectations, may prompt firms to consider GRNI, the translation of these pressures into strategic action depends on the internal values and convictions embedded within the organization. Firms with strong ENVC are not only more attuned to formal demands but also more responsive to informal influences from secondary stakeholders. This commitment makes them more receptive to reputational risks and normative pressures, amplifying the impact of secondary stakeholder demands on innovation decisions (Garcés-Ayerbe et al., 2019).

Firms with strong environmental commitment (ENVC) do not simply react to stakeholder pressures; they proactively internalize them as opportunities for value creation, innovation, and competitive advantage. In such firms, environmental objectives are embedded in core strategy and shape leadership decisions, resource allocation, and employee engagement in green initiatives. From a stakeholder theory perspective, these organizations are more sensitive to stakeholder expectations and view them as essential to long-term success. This alignment strengthens the link between SSTPR and GRNI. In contrast, firms with weak ENVC tend to respond superficially, often engaging in symbolic or short-term compliance. They may view environmental demands as costs rather than strategic opportunities, reducing innovative outcomes. Thus, ENVC acts as a strategic amplifier that determines whether SSTPR translates into meaningful GRNI (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

H5.

ENVC positively moderates the link between SSTPR and the firm’s degree of GRNI.

H5a.

ENVC positively moderates the link between primary SSTPR and GRNI.

H5b.

ENVC positively moderates the link between secondary SSTPR and GRNI.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Context and Design

Bangladesh, where SMEs are regarded as the fulcrum of the South Asian growing economies, contributes 80% of the total employment (25% of the whole country’s GDP). It also has a considerable market share in the manufacturing sector, accounting for 40–50% of total value added (Alauddin & Chowdhury, 2015). According to BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics), there are almost 7.82 million economic enterprises in Bangladesh, which make up 45% of manufacturing value addition, 80% of industrial employment, 90% of all industrial units, and 25% of the labor force. Thus, within the next decades, SMEs may be a primary driver of interest for businesses to stimulate and motivate entrepreneurial activity. Nevertheless, economic success is not necessarily the sole determinant in the corporate world, but rather, to achieve sustainable performance in SMEs, environmental and societal functions are just as crucial as economic growth. Although Bangladeshi industrial policy is inclined to prioritize technology products, due to a dearth of innovation capacities, it is challenging to balance economic prospects and environmental sustainability. As a result, Climate change exposure has made the situation in Bangladesh increasingly urgent. The lack of defined environmental rules and rising carbon emissions are dangerous to reaching the SDGs. In this context, Bangladesh provides a useful framework for studying SMEs, environmental challenges, and technology and innovation. Our study provides a timely assessment of how SSTPR and management’s environmental concern affect green products and process innovation.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

The study follows a quantitative method that employs a questionnaire survey to gather data from the respondents. The questionnaire follows the study of Nguyen and Adomako (2022) and as it enhances the standardization of the question, translation of research objectives into questions, fostering cooperation and collaboration to respond to the question, and also due to the flexibility of the research topic. Using a 7 Likert-scale questionnaire, the survey was distributed among top- and mid-level executives from the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE), the Chittagong Stock Exchange (CSE) listed manufacturing SMEs, and joint-venture SME manufacturing companies with at least 3 years of management professional expertise in their respective industries. Listed and foreign SMEs are more likely to have formalized data, audited reports, and accessible information, which ensures higher data reliability and validity (Gassen, 2017). In contrast, many local SMEs may lack standardized reporting or be unwilling to participate in academic surveys, increasing the risk of response bias. However, due to a large proportion of Bangladeshi SMEs remain informal and differ substantially in terms of governance structures, the findings may not be fully generalizable to informal SMEs, where stakeholder influence mechanisms may operate differently or weakly.

Choosing an adequate sample size is vital for dependable and accurate study results. The study used a sample size of 141 due to the nature of the research and analysis needed. Bryman (2016) recommends a minimum sample size of 100 in surveys to establish statistical significance. Kothari (2004) suggests a minimum sample size of 30 for each variable in research. This study examined numerous factors impacting GRNI, including SSTPR, ENVC, and ethics. The sample size was calculated employing the formula:

n = (Z2 ∗ p ∗ q)/e2

Here, n = required sample size; Z = Z-value (based on confidence level 95%) from the standard normal distribution; p = proportion of the population estimated (0.5 for maximum variability); q = 1 − p; e = margin of error (0.05).

This formula yielded a minimum sample size of 121 SMEs. To account for anticipated nonresponse and incomplete responses, investigators increased the sample size to 141 (Rigdon, 2016). A sample size of 141 was determined to be appropriate for this study based on the research area, nature, and analysis required.

The study employed a two-wave survey system to reduce the common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The questionnaire was originally written in English, but a team of bilingual professionals translated it into Bangla to improve accessibility and understanding. In wave 1, the respondents were offered socio-demographic data and insights on the pressure from primary and secondary stakeholders and ensuring the confidentiality of the information to minimize social desirability biases. We obtained 176 complete responses after contacting 197 individuals from our network and sending a reminder email after two weeks. We received 158 valid replies for Wave 1, after removing invalid responses from non-manufacturing enterprises, non-SMEs, and lower-level managers and workers with fewer than 3 years of work experience. In wave 2, the data were gathered after 1 month of wave 1 from the participants if they wished to participate, where variables like GRNI, ENVC, and ethics were collected. Waves 1 and 2 had a considerable time distance (1 month) to minimize the memory bias and enhance memory. At the same time, the respondents were given a unique identification number to match anonymously and determine whether there was any duplication of the responses coming from the same organization. In wave 1, a total of 158 responses were collected, and 151 responses were collected in wave 2 during December 2024, but 10 responses were removed from the list due to incomplete information. As a result, a total of 141 responses were taken, constituting a response rate of 89% and Goudy (1976) suggests that the range of response rate between 30% to 70% is acceptable, which implies the response rate was satisfactory for the study.

Due to limited access, the niche nature of the target population, and given the absence of comprehensive databases on environmentally oriented SMEs in Bangladesh, using a nonprobability sampling method (snowball and convenience) 141 responses were collected through offline surveys and personal visits through a structured questionnaire. Firstly, a pilot survey was conducted with 25 SME managers, which represents more than 10% of the sample size and is probably sufficient when the size of population effect is moderate or larger (Hertzog, 2008), and then the questionnaire was partially modified in the initial stage to boost the comprehension and context relevance. To reduce the likelihood of the social desirability bias, particularly in culturally sensitive circumstances due to the self-reported measures, all responses were gathered anonymously to encourage truthful disclosure. The questionnaire utilized in this study is broken into two major sections, which are represented in Table 1. The first section posed questions about the firm’s profile, such as its year of business and ownership structure. The survey also included demographic questions such as age, gender, years of experience, and level of education. The second portion of the questionnaire asked respondents to rate each component using a 7-point Likert scale.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

3.3. Measurement Tools

The study employs the research model that was used by the earlier studies. The main constructs that are primary and secondary SSTPR, and GRNI were adopted from (Charan & Murty, 2018; Singh et al., 2021) with 6 items and 3 items, respectively. Environment commitment was adopted from (Nguyen & Adomako, 2022) with 3 constructs, and the organizational ENVE was adopted from the (Rui & Lu, 2020) using 2 measurement scales. The study uses the subjective-oriented measurement of GRNI due to the unavailability of secondary data. The scales for primary and secondary SSTPR range from 1 (to a very large extent) to 7(to a very low extent), and the remaining scales range from 1 to 7 (strongly agree to strongly disagree).

4. Findings and Analysis

4.1. Measurement Model

This study employs SEM (structural equation modeling) to examine robustness as it is regarded as the correct estimation of the underlying model (J. Hair et al., 2017). To quantify the cause-and-effect relationship among the variables, the explanatory factor analysis and path model analysis were employed using SPSS and Amos Graphics (version 21.00). Moreover, the common method bias and multicollinearity issues will also be measured.

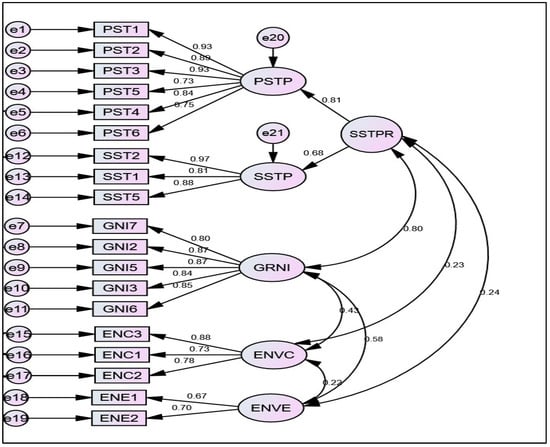

The measurement model was examined to assess the fitness of the intended variables that were studied. Since the dimension of SSTPR is not explicitly distinct to ensure internal consistency of the constructs with others, the EFA (Exploratory factor analysis) presented in Table 2 reflects a 2-dimensional solution with 9 items. To ensure the model’s authenticity and robustness, the reliability, validity, and CFA were estimated to represent the constructs by taking SSTPR as a second-order construct. Due to poor loadings of the regression weight, 2 items from ENVC and 3 items from ENVE had to drop out, which was employed as a theory-consistent purification step to enhance measurement precision while preserving the conceptual integrity of the ENVC and ENVE constructs. Figure 2 is illustrated with all the regression weights of the factor analysis, where each construct yields a regression weight of more than 0.70, and the representing variable also depicts a good fit model (χ2/df = 2.824, GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.914, NFI = 0.938, CFI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.061, p-value = 0.000) (J. F. Hair et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

Table 3 and Table 4 illustrate reliability and validity estimation in terms of cross-loading, convergent validity, composite reliability, and discriminant validity to examine the construct’s dependability and validity recommended by (J. Hair et al., 2017). Indicator loading is known as the relationship between a specific factor and its associated items. Indicator loadings and convergent validity are represented by the outer loadings of the variable items, which should exceed 0.70 for the study to be deemed valid. Furthermore, the reliability score should exceed 0.70, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which also indicates convergent validity, should be approximately 0.50 or higher. The reflective measurement model, along with the results for outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and AVE, have met acceptable threshold values.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion).

Table 4.

Heteriotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

The table shows that the minimum Average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.626 and 0.755, which are greater than the minimum threshold value of 0.50. The composite reliability is more than 0.70, respectively (J. F. Hair et al., 2014). The discriminant validity (represented in a diagonal line with bolded values), which exhibits the square root of AVE, is greater than their correlation with other inner constructs. It indicates no issues with discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). To ensure discriminant validity, each variable’s HTMT Value must be less than 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2015). Table 4 discovered discriminant validity. Moreover, the composite reliability is higher than the correlation coefficient of each construct with a cut-off value of 0.7. The correlation of the control variables (firm size and firm age) is also significant. Additionally, the values of Cronbach’s α range from 0.752 to 0.959, which is greater than the threshold value of 0.7 (Lance et al., 2006). The total variance that accounts for the 4 factors is 83.08. Thus, the above-mentioned criteria result in the conclusion that the model is free from any discriminant validity issues.

4.2. Common Method Bias and Multicollinearity Issue

The study employs common method bias due to self-reported instruments, which is an issue for the survey-based measurement. As suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003), we remained conscious of the respondents’ transient moods and assured them of anonymity. Therefore, Harman’s single-factor test was examined, where the result of explanatory factor analysis reveals that only 37% variation is explained by the unrotated principal component. Since the result is below 50% (J. Hair et al., 2017), it ensures the study is free from common method bias. Moreover, for the multicollinearity issues, the result of the maximum inner variance inflation (VIF) value shows 4.907, which is lower than the threshold of 10, representing negligible multicollinearity. Finally, we employed the measured latent marker variable approach to assess common method bias by analyzing the comparison of the coefficients of determination (R2) between two models (with and without the marker variable). The marker variable was operationalized using a social desirability scale (Hays et al., 1989). The questionnaire item ‘How important is achieving financial security in your life?’ was used as a marker variable. The analysis revealed that incorporating the marker variable led to minimal changes (less than 5%) in the R2 values (Table 5). Additionally, a comparison of the path coefficients across both models indicated no differences in the significance of the paths. As the inclusion of the marker variable resulted in only negligible changes in the R2 values for all endogenous constructs, it suggests that common method variance was not a significant threat to the validity of this study.

Table 5.

Multi-collinearity statistics.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

The study employs a structural model equation with a good model fitness, which is represented in Table 6. The overall fit indices (χ2/df = 2.546, GFI = 0.936, AGFI 0.911, NFI 0.930, CFI 0.918, TLI 0.910, RMSEA 0.073), which satisfy the value of the suggested range recommended by J. F. Hair et al. (2014).

Table 6.

Model fit measurement.

Cohen et al. (2013) suggest that values of β and R2 higher than 0.12 are considered satisfactory and suitable for the study. Utilizing 5000 bootstrapping sampling times, Table 7 shows the value of the β coefficient (t-values) and the R2 for ENVC and GRNI (ranging from 0.214 to 0.613) were higher than the onset value of 0.12. Moreover, f2 values showed in the relationship of the model between the constructions varied from 0.027 to 0.476, and they are presented in Table 6. An f2 value higher than 0.02 indicates that the model presents a robust association, although this value close to zero was biased and irrelevant. Hence, f2 values greater than 0.02 represent the relationship intensity between each independent and dependent variable (J. Hair et al., 2017).

Table 7.

For structural model assessment.

Here, Figure 3 represents the structural model equation, and Table 8 exhibits the results of hypothesis testing through 5 consecutive models. Among the 5 hierarchical models, in model 1, the direct relation between SSTPR (primary and secondary) and ENVC will be represented, and the direct relation between SSTPR (primary and secondary) and GRNI is also represented in model 2, while the relation between ENVC and GRNI will be illustrated in model 3. However, model 4 depicts the effect of SSTPR on GRNI, with ENVE (ENVE) acting as a mediating variable, while model 5 is an augmentation of model 4 where ENVC serves as a moderating variable.

Figure 3.

Structural Equation Model.

Table 8.

Hypothesis-testing model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1) proposed that SSTPR has a positive influence on ENVC, which was found to be statistically significant (Model 1, β = 0.233, t-value = 2.627, p-value = 0.009). Moreover, H1a and H1b suggest that both PSTP and SSTP have positive influences on ENVC, which was also found to be significant statistically (H1a: β= 0.243, t-value = 2.580, p-value = 0.011; and H1b: β = 0.231, t-value = 2.112, p-value = 0.036).

Again, Hypothesis 2 (H2) proposed that SSTPR has a positive relation with GRNI, which is confirmed as the path between SSTPR and GRNI was found to be significant statistically (Model 2, β = 0.561, t-value = 5.058, p-value = 0.000). Additionally, H2a and H2b suggest that both PSTP and SSTP have a positive influence on GRNI, which was also found to be significant statistically (H2a: β = 0.618, t-value = 7.843, p-value = 0.000; and H2b: β = 0.664, t-value = 8.935, p-value = 0.000).

Furthermore, H3 suggests that ENVC has a positive impact on GRNI, which also results in a significant (Model 3, β = 0.194, t-value = 2.096, p-value = 0.038).

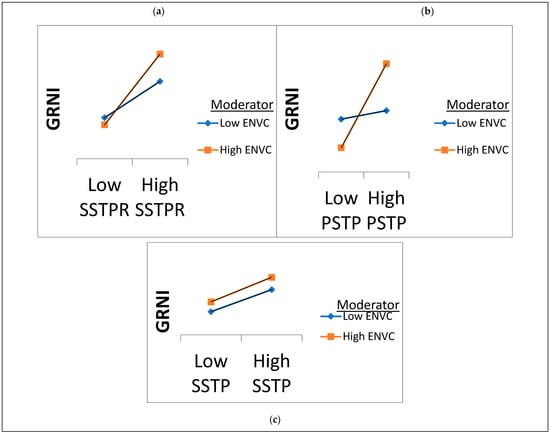

Figure A1 in Appendix A also illustrates the moderating effect of ENVC on SSTPR and GRNI (H5), on PSTP and GRNI (H5a), and SSTP and GRNI (H5b). H5 suggests that the influence of SSTPR on GRNI is moderated by ENVC, which asserts that the higher appearance of ENVC strengthens the positive influence of SSTPR on GRNI, whereas the lower appearance of ENVC weakens the positive influence of SSTPR on GRNI (Model 5, β = 0.158, t-value = 2.132, p-value = 0.033) with a positive slope. Similarly, the H5a and H5b were also tested, where H5a was supported (β = 0.612, t-value = 6.429, p-value = 0.000), affirming that the influence of PSTP on GRNI is moderated by ENVC, which asserts that the higher appearance of ENVC strengthens the positive influence of PSTP on GRNI, whereas the lower appearance of ENVC weakens the positive influence of PSTP on GRNI. However, H5b portrays the positive moderation of ENVC on the relationship between SSTP and GRNI (β = 0.032, t-value = 0.449, p-value = 0.654), though their relationship is not significant, which does not support the hypothesis, suggesting that firms may not respond to secondary stakeholders unless strongly committed to environmental values. This divergence from Western contexts, where NGOs and media often directly shape firm behavior, emphasizes the contextual role of institutional strength and societal awareness. In weakly institutionalized environments like Bangladesh, secondary stakeholders’ signals may lack enforcement power, and resource-constrained SMEs are likely to prioritize pressures that have immediate strategic or economic consequences. This underscores the need for comparative research across institutional contexts to examine how the relative influence of secondary stakeholders varies between strong and weak institutional environments, and how ENVC interacts with these pressures under differing cultural, regulatory, and resource conditions.

H4 states that ENVE is the mediating variable between SSTPR and GRNI, which was also supported in examining the mediating role of ENVE. At first, this study examined the indirect effect of SSTPR on GRNI through ENVE, and it exhibits a significant effect with a β value of 0.142. Then, the direct effect of SSTPR on GRNI was also examined after removing ENVE as a mediator and found a significant positive impact with a β value of 0.597 (Table 9), which indicates ENVE complementary partial mediation. The results extracted from the model exhibit that the indirect effect is significant in the presence of a mediator, where the value of the indirect effect path is less than the total effect path, and as a rule of thumb, the relationship between SSTPR and GRNI is partially mediated by the ENVE, which supports the hypothesis (Ghadi et al., 2013). The value of R2 increased from 0.443 to 0.548, and the Sobel test was also run to rationalize the mediation effect decision, where the estimate suggests a significant value of indirect effect (z-statistics = 2.121 > 1.96, p = 0.033 < 0.05). Hence, H4 is supported. However, this contrasts with prior studies where ethics served as the primary mediating pathway, highlighting a context-specific gap likely shaped by Bangladesh’s institutional weaknesses, resource constraints, and socio-cultural norms. Firms may thus rely on a combination of strategic considerations, resource availability, and ethical judgment to respond to stakeholder expectations.

Table 9.

Result of mediation (ENVE as a mediating variable).

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine how SSTPR influence GRNI adoption among SMEs in Bangladesh. Moreover, the study contributes to the literature by unpacking the internal mechanisms: environmental ethical orientation and strategic commitment through which external pressures are filtered and translated into substantive GRNI. Drawing on Stakeholder Theory, the findings yield several important theoretical and practical insights.

First, the findings indicate that primary stakeholders exert a significantly stronger influence on firms’ ENVC than secondary stakeholders (H1a supported more strongly than H1b). This aligns with Mitchell et al.’s (1997) salience model, which posits that stakeholders possessing power, legitimacy, and urgency are more likely to shape organizational behavior. In the Bangladeshi SME context, actors such as export buyers, regulatory agencies, and supply chain partners directly affect firms’ operational continuity and access to markets. Consequently, pressure from these primary stakeholders appears to drive a more substantive strategic commitment toward environmental responsibility, which SMEs increasingly view not only as a compliance requirement, but also as a means of market retention and competitiveness (Adomako et al., 2023). While secondary stakeholders such as NGOs, media, and community groups also demonstrated a statistically significant relationship with ENVC (H1b), their effect was noticeably weaker, suggesting that their influence is more indirect and mediated through reputational channels rather than immediate economic consequences. Furthermore, the findings underscore a gradual cultural shift in Bangladeshi enterprises, particularly among younger entrepreneurs and family-owned SMEs, where environmental consciousness is being integrated into business values, not solely as a response to regulation, but as part of a broader commitment to sustainable development. This is particularly important in the context of Bangladesh’s vulnerability to climate change, where SMEs are beginning to view ENVC not as a cost center, but as a source of strategic differentiation, reputational capital, and futureproofing.

Secondly, the results confirm that SSTPR significantly and positively influence GRNI (H2, H2a, H2b). Again, the effect of primary stakeholders was stronger than that of secondary stakeholders. This suggests that in the Bangladeshi SME context, stakeholder-induced legitimacy pressures operate primarily through economic and market-based incentives rather than through social or moral persuasion alone. Although NGOs and media contribute to shaping broader environmental expectations, SMEs appear more responsive when such pressures are tied to tangible benefits or risks, such as export contracts, certification requirements, or regulatory penalties. This finding reinforces the argument that stakeholder salience in emerging economies is often closely connected to resource dependence rather than normative authority (Majeed et al., 2024; Ullah et al., 2023).

Importantly, these findings also raise a critical issue highlighted in stakeholder theory: the risk of symbolic compliance. While SSTPR encourage the adoption of environmentally oriented practices, it cannot be assumed that all observed innovation is substantive. As Delmas and Toffel (2008) and Lian et al. (2022) argue, some firms may engage in “window dressing” or greenwashing to preserve legitimacy in the eyes of powerful stakeholders. Given the weak enforcement mechanisms in Bangladesh, the possibility remains that some SMEs adopt GRNI selectively or superficially, particularly when compliance is driven by external pressure rather than internalized values. This underscores the need to interpret GRNI not merely as an instrumental response to pressure, but as an outcome closely tied to internal organizational orientation.

Third, the positive relationship between ENVC and GRNI (H3) reinforces that innovation is not driven solely by coercive pressures but by strategic internal alignment. Firms with stronger ENVC tend to integrate environmental considerations into long-term planning, resource allocation, and technology-related decisions. In Bangladeshi SMEs, where ownership and management are often centralized, managerial values play a crucial role in shaping this strategic direction. Thus, GRNI emerges not only as a reaction to stakeholders but also as a manifestation of leadership priorities and organizational intent (Karim et al., 2024). Rather than claiming a generalized “cultural shift,” the findings more cautiously suggest that among the sampled SMEs, particularly formal, listed, and joint-venture firms, there is emerging evidence of managerial recognition that environmental responsibility can contribute to reputation, resilience, and long-term competitiveness.

The partial mediating effect of ENVE (H4) further clarifies that stakeholder pressure does not operate through a single channel. While SSTPR directly influence GRNI, they also act by shaping the firm’s internal ethical orientation, which affects how environmental issues are interpreted and prioritized. However, since the mediation is partial, ethics alone do not fully translate pressure into innovation. This suggests that although moral reasoning matters, it is not always sufficient to overcome structural barriers such as limited capital, weak infrastructure, and technological constraints. In line with Yazıcı and Çiçeklioğlu (2025) and Rui and Lu (2020), ethical awareness may initiate sensitivity to environmental issues, but in the absence of strategic commitment and organizational capacity, it may not lead to sustained innovation.

The moderating role of ENVC (H5) further reinforces this distinction. Firms with stronger ENVC were significantly more capable of transforming stakeholder pressure, especially from primary stakeholders into actual GRNI (H5a supported). This indicates that ENVC acts as an internal amplifier, strengthening the responsiveness of firms to stakeholder demands which is consistent with M. Wang et al. (2024). In contrast, the moderating effect of ENVC on secondary stakeholder pressure was not significant (H5b unsupported). This is a critical and theoretically meaningful result. It implies that even committed firms prioritize pressures that are more economically and operationally salient, while the diffuse influence of NGOs or media may not be sufficient to drive innovation in the absence of direct market or regulatory consequences. This nuance directly addresses the apparent inconsistency in earlier interpretations and highlights that secondary stakeholders may be influential, but not decisive, in shaping innovation outcomes in this context. One explanation is that resource constraints and short-term survival pressures limit the strategic attention SMEs can devote to broader societal expectations unless they align with commercial imperatives (Amer & Bonardi, 2023). This asymmetry in moderating effects highlights an important nuance: ENVC enhances the firm’s sensitivity to stakeholder influence, but the type of stakeholder matters. A plausible explanation may be the low societal pressure or awareness in Bangladesh’s institutional context, where reputational threats are less immediate for SMEs. This invites future inquiry into the cultural and institutional enablers of secondary stakeholder effectiveness. For instance, Qualitatively, export-oriented SMEs face intense pressure from buyers to meet international environmental standards, while government regulations provide baseline legitimacy and sanction threats. Recognizing these dominant pressures helps explain why ENVC significantly moderates primary stakeholder influence but not secondary stakeholder influence (H5b), and highlights the contextual specificity of the stakeholder–green innovation relationship in emerging economies.

However, in resource-constrained settings like Bangladeshi SMEs. Ethics may shape awareness and moral responsibility, but without strong strategic backing or organizational capabilities, ethical concerns alone may fail to drive consistent GRNI. In contrast, ENVC, being a strategic and action-oriented construct, entails deliberate resource allocation, long-term planning, and managerial willpower to embed environmental goals into core operations. This makes it a stronger enabler in converting SSTPR into substantive innovation outcomes. Therefore, while ethics initiate a moral lens through which pressures are interpreted, it is ENVC that determines the extent to which these pressures are acted upon.

Theoretical, Practical, and Policy Implications

This study advances stakeholder theory by illustrating the dynamic interaction between external SSTPR and internal psychological drivers specifically, ENVC and ethical awareness in shaping SMEs’ GRNI practices. The finding that ENVE partially mediates, and ENVC significantly moderates, the stakeholder and GRNI relationship suggests that stakeholder influence is most effective when firms have already internalized sustainability as both a moral value and a strategic priority. In this sense, the study refines stakeholder theory by highlighting that internal ethical orientation and commitment function as critical transmission mechanisms through which external pressures are converted into substantive green innovation behaviors. This nuanced explanation is particularly important for resource-constrained and weak-institutional environments, where regulatory force and reputational risk may be insufficient drivers of pro-environmental conduct. By empirically situating internal ethical and attitudinal capacities as key enablers of external influence, the findings offer a more context-sensitive theoretical account of how green innovation emerges in emerging-market SMEs.

From a policy perspective, the results support a targeted, multi-level intervention approach for accelerating green innovation in Bangladesh. First, because environmental ethics partially mediates stakeholder influence, agencies such as the SME Foundation and the Ministry of Industries could integrate sector-sensitive environmental ethics and sustainability training into existing SME support schemes. These programs should move beyond compliance awareness and focus on embedding long-term ecological responsibility into managerial decision-making. Second, given the amplifying role of environmental commitment, policymakers and financial institutions could consider linking green financing instruments, tax benefits, or concessional credit facilities to demonstrated environmental commitment (e.g., adoption of environmental policies, sustainability targets, or internal green practices). Such conditional incentives align with the study’s finding that stakeholder pressure is more effective when internal commitment is high. Finally, rather than mandating immediate compliance, a phased encouragement of basic ESG disclosure practices among medium-sized enterprises could be considered. Even simplified ESG reporting would increase transparency, enhance stakeholder engagement, and progressively align firms with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while remaining sensitive to SMEs’ technical and financial constraints.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to advancing Stakeholder Theory by unpacking how GRNI adoption among SMEs in Bangladesh is shaped by the interplay of external SSTPR and internal organizational factors, namely, ENVC and ethics. Unlike conventional studies that examine these drivers in isolation, our findings emphasize a relational and layered mechanism—while SSTPR (from both primary and secondary groups) strongly influence firms’ GRNI behavior, the translation of these pressures into actionable outcomes depends significantly on the internal environmental values and strategic intent of the firm. Importantly, the partial mediation of ENVE suggests that ethical orientation alone is not sufficient to drive GRNI unless coupled with external stakeholder expectations and strategic commitment. Likewise, ENVC strengthens the firm’s responsiveness to both coercive and normative pressures—but fails to significantly moderate secondary stakeholder influence, highlighting a potential hierarchy of stakeholder salience in weakly institutionalized environments like Bangladesh. This divergence challenges assumptions of equal stakeholder influence and underscores the need to distinguish between symbolic and substantive engagement with sustainability.

These insights contribute theoretically by contextualizing Stakeholder Theory within emerging economies, where informal pressures, resource constraints, and legitimacy concerns interact differently than in developed contexts. Practically, the findings call for multi-stakeholder alignment strategies that strengthen both ethical infrastructure and strategic readiness within SMEs. GRNI is not merely the outcome of regulation or ethics but emerges through the strategic internalization of stakeholder signals into firm identity, routines, and capabilities.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study offers valuable insights, several limitations warrant consideration. First, although common method bias reflects no issues, the use of self-reported data from single respondents may introduce common method variance and social desirability bias, particularly on subjective constructions like GRNI, ENVE and ENVC. Although we applied two-wave data collection to mitigate this risk, future studies should incorporate multi-source data (e.g., supplier, regulator, or employee perspectives) and use objective green performance indicators where possible. Second, while the sample of formal manufacturing SMEs offers relevance to the Bangladeshi context, it limits generalizability across sectors and countries where a substantial portion of Bangladeshi SMEs operate in the informal sector. Extending this research to cross-country or cross-sectoral comparisons, particularly between emerging and developed economies, could reveal how variations in institutional strength, market maturity, and stakeholder activism shape the stakeholder–green innovation nexus. Firms in sectors like services, textiles, or agriculture may experience different stakeholder dynamics. Future studies should adopt stratified or probability-based sampling and expand across multiple industries and regions, particularly in South and Southeast Asia, where environmental regulation is evolving. Thirdly, while this study focused on ENVE as a mediator, it is also theoretically plausible for ENVE to act as a moderator, especially in contexts where stakeholder signals are weak or ambiguous. Finally, cultural and institutional context remains a critical, underexplored variable. In Bangladesh, contextual factors, such as weak institutional enforcement, limited media influence, or low societal awareness, and resource and capability constraints, may have reduced the perceived urgency or legitimacy of secondary H5b. Future studies should refine measurement instruments for secondary stakeholder pressure, conduct comparative research between high- and low-institutional environments or incorporate qualitative methods (e.g., case studies, stakeholder interviews) to understand how informal norms, corruption, or political ties shape GRNI pathways. Exploring intersectionality—specifically with respect to how firm size, owner gender, or export orientation affects green responsiveness—would also be a valuable future direction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.K.; Investigation, A.H.; Formal analysis, F.H. and U.K.; Writing—review and editing, R.H., F.H., A.H. and U.K.; Supervision, U.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Chittagong (protocol code AERB and date of 15 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available on request. Please contact the corresponding author (Fakhrul Hasan) for data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

(a) Moderating effect of ENVC on SSTPR and GRNI, (b) moderating effect of ENVC on PSTP and GRNI, and (c) moderating effect of ENVC on SSTP and GRNI.

References

- Adomako, S., Simms, C., Vazquez-Brust, D., & Nguyen, H. T. T. (2023). Stakeholder green pressure and new product performance in emerging countries: A cross-country study. British Journal of Management, 34(1), 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M., Yu, Y., & Bu, Y. (2025). The impact of digital transformation of resource-based enterprises on green innovation: Mechanism analysis based on TOE framework. Innovation and Green Development, 4(4), 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, M. D., & Chowdhury, M. M. (2015). Small and medium enterprises in Bangladesh-prospects and challenges. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 15(7), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, E., & Bonardi, J. P. (2023). Firms, activist attacks, and the forward-looking management of reputational risks. Strategic Organization, 21(4), 772–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methodology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charan, P., & Murty, L. S. (2018). Secondary stakeholder pressure and organizational adoption of sustainable operations practices: The mediating role of primary stakeholders. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(7), 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M. A., & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlevi, M., Hasan, F., & Islam, M. R. (2023). Exploring consumer attitudes and purchase intentions: Unraveling key influencers in China’s green agricultural products market. Corporate and Business Strategy Review, 4(3), 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ayerbe, C., Rivera-Torres, P., & Suárez-Perales, I. (2019). Stakeholder engagement mechanisms and their contribution to eco-innovation: Differentiated effects of communication and cooperation. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(6), 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassen, J. (2017). The effect of ifrs for smes on the financial reporting environment of private firms: An exploratory interview study. Accounting and Business Research, 47(5), 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, M. Y., Fernando, M., & Caputi, P. (2013). Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 34(6), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudy, W. J. (1976). Nonresponse effects on relationships between variables. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40(3), 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M., Lin, H., Wang, J., Wang, Y., & Jiang, W. (2019). Turning corporate environmental ethics into firm performance: The role of green marketing programs. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(6), 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49(2), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F., & Al-Najjar, B. (2024). Green investment and dividend payouts: An intercontinental perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 370, 122626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F., & Al-Najjar, B. (2025). Consumer confidence as a mediator between dividend announcements and stock returns. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 65(4), 1571–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F., Islam, M. R., & Siddique, M. (2022). Management challenges analyses and information system development in SMEs due to COVID 19 fallout: Prescriptive case study. International Journal of Critical Accounting, 13(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R. D., Hayashi, T., & Stewart, A. L. (1989). A five-item measure of socially desirable response set. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 49(3), 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M. A. (2008). Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 31(2), 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hojnik, J., Ruzzier, M., Konečnik Ruzzier, M., Sučić, B., Soltwisch, B., & Rus, M. (2024). Review of EU projects with a focus on environmental quality: Innovation, eco-innovation, and circular-economy elements. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 8(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H. (2025). Nexus of economic, social, and environmental factors on sustainable development goals: The moderating role of technological advancement and green innovation. Innovation and Green Development, 4(1), 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, R., Roshid, M. M., Dhar, B. K., Nahiduzzaman, M., & Kuri, B. C. (2024). Audit committee characteristics and sustainable firms’ performance: Evidence from the financial sector in Bangladesh. Business Strategy and Development, 7(4), E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, U. N., Haque, A., Kulsum, U., Mohona, N. T., & Hasan, F. (2023). Modeling the green consumption values to promote the attitude towards organic food consumption. Sustainability, 15(17), 13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G., Xu, A., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Substantive green innovation or symbolic green innovation? The impact of er on enterprise green innovation based on the dual moderating effects. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(3), 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M. A., Ahsan, T., & Gull, A. A. (2024). Does corruption sand the wheels of sustainable development? Evidence through green innovation. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(5), 4626–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salien. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Luna, J. L., Garcés-Ayerbe, C., & Rivera-Torres, P. (2008). Why do patterns of environmental response differ? A stakeholders’ pressure approach. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11), 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. P., & Adomako, S. (2022). Stakeholder pressure for eco-friendly practices, international orientation, and eco-innovation: A study of small and medium-sized enterprises in Vietnam. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(1), 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y., Harrison, J., & Chen, L. (2019). A framework for the practice of corporate environmental responsibility in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 235, 426–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E. E. (2016). Choosing PLS path modeling as analytical method in european management research: A realist perspective. European Management Journal, 34(6), 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Andrés, M., Ramos-González, M. D. M., Sastre-Castillo, M. Á., & Gutiérrez-Broncano, S. (2023). Stakeholder pressure and innovation capacity of smes in the COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating and multigroup analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 190, 122432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z., & Lu, Y. (2020). Stakeholder pressure, corporate environmental ethics and green innovation. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 29(1), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M., Qu, Y., Zafar, A. U., Ding, X., & Rehman, S. U. (2020). Translating stakeholders’ pressure into environmental practices—The mediating role of knowledge management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 124163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K., Del Giudice, M., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Latan, H., & Sohal, A. S. (2021). Stakeholder pressure, green innovation, and performance in small and medium-sized enterprises: The role of green dynamic capabilities. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(1), 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K., Del Giudice, M., Nicotra, M., & Fiano, F. (2020). How firm performs under stakeholder pressure: Unpacking The role of absorptive capacity and innovation capability. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 69(6), 3802–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F., Boiral, O., & Iraldo, F. (2018). Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? Journal of Business Ethics, 147(2), 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S., Ahmad, T., Lyu, B., Sami, A., Kukreti, M., & Yvaz, A. (2023). Integrating external stakeholders for improvement in green innovation performance: Role of green knowledge integration capability and regulatory pressure. International Journal of Innovation Science, 16(4), 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Li, Y., Wang, Z., Shi, Y., & Zhou, J. (2024). The synergy impact of external environmental pressures and corporate environmental commitment on innovations in green technology. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(2), 854–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Young, M. N. (2014). Does collectivism affect environmental ethics? A multi-level study of top management teams from chemical firms in China. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(3), 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Font, X., & Liu, J. (2020). Antecedents, mediation effects and outcomes of hotel eco-innovation practice. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Abbass, K., & Li, D. (2024). Advancing eco-excellence: Integrating stakeholders’ pressures, environmental awareness, and ethics for green innovation and performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 352, 120027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, A. M., & Çiçeklioğlu, H. (2025). The moderating role of environmental ethics in the effect of green innovation awareness on corporate social responsibility. Social Responsibility Journal, 21(4), 826–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).