Abstract

Taxation on cryptocurrency is becoming critical in global fiscal governance as digital assets adapt to the modern reality of existing outside of traditional regulatory constructs. Theoretical and practical understanding of cryptocurrency taxation is quite new, and so a systematic review was designed to present the most recent empirical research evidence on the legal, fiscal and behavioral aspects of cryptocurrency taxation from across the globe. Using the PRISMA-2020 guidelines, a structured search was applied to the Scopus database on 21 May 2025, with the search terms “crypto-currency”, “cryptoasset” and “taxation.” The inclusion criteria consisted of original research articles published between the years of 2020 and 2025 in English or Spanish, that could be accessed via institutional library support, and that were related to taxation, legal regulation and/or compliance. Out of the original identified 224 records, 36 met the eligibility criteria after screening and verification through seven different stages of review. Socially, five themes were produced by the findings: legal ambiguity surrounding fiscal treatment, limited tax literacy and compliance issues, macroeconomic and monetary issues, application of digital technologies for fiscal tracking, and environmental repercussions from crypto mining. Many countries do not have any coherent tax frameworks to govern the risk that emerges from cryptocurrency taxation, creating uncertainty for both regulators and investors. The findings outlined in this systematic review point to the urgent need for creating a coherent approach to cryptocurrency taxation based on definitions, digital approaches to traceability, and tax literacy compliance strategies. In order to create effective cryptocurrency taxation, there must be a base balance between ensuring innovation, fiscal responsibility, transparency, equity and sustainability in the developing digital economy.

1. Introduction

Cryptocurrencies are digital or virtual currencies that utilize cryptographic techniques to ensure secure transactions, control the creation of new units, and verify asset transfers (Agarwal et al., 2024; Almasri & Arslan, 2018; Hellwig et al., 2020). They operate on decentralized networks, typically using blockchain technology, which serves as a public ledger for all transactions (Almasri & Arslan, 2018; Härdle et al., 2020; Madakam et al., 2023). Unlike traditional currencies, cryptocurrencies are not issued or regulated by any central authority, making them immune to government interference and banking regulations (Islam et al., 2024; Madakam et al., 2023). This decentralization offers benefits such as financial inclusion, transparency, and innovation but also presents challenges like regulatory uncertainties and market volatility (Agarwal et al., 2024; B. Singh & Kaunert, 2024). Cryptocurrencies have gained significant attention and adoption globally, with Bitcoin being the most prominent example (Timuçin et al., 2021). However, the energy-intensive process of mining cryptocurrencies raises environmental concerns due to substantial carbon emissions and energy consumption 9. Despite these issues, cryptocurrencies continue to evolve, with some countries exploring regulatory frameworks to address legal and practical challenges (Senarath, 2022; B. Singh & Kaunert, 2024). The potential for cryptocurrencies to drive financial innovation and social entrepreneurship is also being explored, highlighting their role in sustainable development and community cooperation (Mora et al., 2021).

The rapid expansion of cryptocurrencies has generated fiscal and regulatory challenges across all major regions of the world. Governments from the United States and the European Union to emerging economies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are struggling to determine how digital assets should be defined, monitored, and taxed. Although the adoption of cryptocurrencies has been driven largely by private-sector incentives (such as alternative investment opportunities, payment innovation, and hedging against macroeconomic instability), public authorities face a different set of concerns. These include the risks of capital flight, tax evasion, illicit financial flows, weakening monetary sovereignty, and the erosion of traditional tax bases.

At the same time, governments also recognize potential benefits associated with allowing cryptocurrency activity within their jurisdictions. These include opportunities to generate new tax revenues, increase financial inclusion, attract digital-economy investment, strengthen technological competitiveness, and improve fiscal transparency through blockchain-enabled traceability. As a result, countries have adopted widely divergent regulatory and tax approaches, ranging from permissive frameworks (United States, United Kingdom, Australia) to restrictive regimes (China, Russia) and hybrid or intermediate models (Canada, Singapore, Brazil). This international diversity underscores the need for a systematic review that examines how different jurisdictions conceptualize, regulate, and tax cryptocurrencies and how these lessons can inform national policy design.

One challenge related to altcoin assets is the lack of clear, consistent taxation in the realm of altcoin transactions (Swan, 2015). In numerous jurisdictions, laws surrounding the use, trading, and taxation of altcoins do not yet exist. The lack of law results in ambiguity about legal definitions. The uncertainty complicates taxation, enables avoidance, and adds the possibility for laundering or manipulation of markets. This situation is more acute in developing countries such as Peru, where revenue authorities are faced with the difficulty of monitoring cross-border digital transactions (OECD, 2020).

Furthermore, the high volatility of many altcoins, combined with the absence of regulation focused on them, limits the amount of public confidence in the technology and with integrating altcoins into the formal financial system. This combination produces a simultaneous disconnect between the urgency of technological development in the digital market and the pace with which fiscal and regulatory authorities are responsive to legislation and to capitalize on oversight and transparency in this developing economic landscape (Yermack, 2013).

This study therefore seeks to position cryptocurrencies within a coherent analytical framework by clarifying the economic and legal parameters that shape their fiscal treatment and by identifying the regulatory gaps that hinder consistent oversight across jurisdictions.

According to Luciani Toro et al. (2022), cryptocurrencies are rapidly entering the business world. Reports increasingly document small- and medium-sized enterprises as well as multinational corporations adopting these digital assets for payment platforms, investment portfolios, and even financing mechanisms (Mosquera Endara, 2022). Cryptocurrencies have gained traction in Ecuador, where some investors accept the associated risks despite a lack of government control or regulation. The rise in internet-enabled technologies has enabled new financial systems to operate partially beyond state oversight. Cryptocurrencies make it possible to acquire goods and services without intermediaries and facilitate streamlined transactions and new investment opportunities (Trujillo Pajuelo et al., 2022).

A broad study has therefore been proposed to define and systematize the fundamental concepts underpinning cryptocurrencies and to recommend a specific regulatory framework. Because Peru currently lacks comprehensive legal regulation for these assets, the study focuses on the economic and financial dimensions and on how regulation could improve oversight of cryptocurrency use. Without such a framework, citizens may be exposed to harm when transacting in digital currencies that remain unregulated by the Peruvian state, and the government may forfeit important sources of fiscal revenue (García-Ramos Lucero & Rejas Muslera, 2022). Cryptocurrency transactions (used worldwide for money transfers and investment) are frequently carried out without clear legal protection for consumers, since many adopters lack a legal status for these activities. Technological advancements have led to the rise in virtual currencies—their rise has surpassed their integration into the legal regime (Patricio Lozano, 2022). Recent research has examined the most disruptive aspects of cryptocurrencies, noting that their evolution has enabled their use as a means of payment; as speculative assets, improvements in platforms and supporting technologies have increased their presence in everyday life globally (Regal et al., 2019).

The role of cryptocurrencies in the stock market is akin to that of foreign exchange and equities where international markets reflect supply and demand. Therefore, market participants should adopt strategies to reduce uncertainty and provide effective support for decision-making processes (Barroilhet, 2019). States should also intervene to obtain more oversight and legal support for activities conducted in digital currency (Barroilhet, 2019). Regulatory intervention should be developed to provide legal coverage to guard against misuse and to protect consumers. Legal and conceptual definitions of finance must change to facilitate legal normalization; when this happens, digital currencies may be incorporated into more formal economic activity management and bridge the regulatory gap between money and digital currency as is performed with fiat currency.

Laise (2019) asserts that Argentina’s regime to tax cryptocurrency may be destined to fail not because of a fundamentally illogical approach but due to a failure to sufficiently address the technically oriented nature of digital currencies. This can be solved through clearer administrative rules which would consider both anonymity and the diminished role of intermediaries when transferring money using cryptocurrencies, both features that eliminate traditional financial intermediaries such as banks from the regulatory chain (Lara Gómez & Demmler, 2018). These trends highlight the need to understand cryptocurrencies not only as speculative instruments or technological innovations but as economic entities whose classification and fiscal treatment must be aligned with established principles of public finance.

The astounding rise in altcoins (like Ethereum, Cardano, Solana, etc., not including Bitcoin) has changed the space of virtual finance. Yet their continued growth is constrained by obstacles and restrictions: market-valued volatility compromises their acceptability as a medium of exchange; differences in technology applications (for instance, staking, decentralized finance, and smart contracts) complicate regulation for recognition; the compendium of many users and investors lack the understanding of necessary financial literacy to operate in these markets; and the lack of transparency for many exchange platforms limits tracing transactions, resulting in increased legal and economic risks. In the Peruvian context and especially in Lima, its institutional acceptance is not as strong, and public understanding of how these assets function and what they mean is limited (Barroilhet, 2019).

The fast pace of fintech innovation is now outpacing the regulatory capacity of many states, leaving a significant fiscal and regulatory gap in the realm of cryptocurrencies and other digital assets (Wang, 2025). In Peru, no specific tax framework has been established to control for specific activities related to cryptocurrencies, such as capital gains, mining, staking, or trading, which leads to significant legal gaps. SUNAT and other bodies have not produced robust control or oversight systems capable of monitoring transactions on decentralized platforms. Due to the global and often anonymized nature of most transactions, it is often impossible to trace activity in any way; people can evade tax obligations and engage in criminal activity, including money laundering. In addition, there are no accounting and valuation standards designed for easy inclusion of digital assets in government fiscal and financial systems. Finally, the absence of any coordination between competent bodies, such as SUNAT, SBS, and BCRP, generates an environment that is legally and fiscally uncertain for users and potential investors in this burgeoning digital financial market (Saavedra Rodríguez, 2025).

As Rodríguez Cairo (2020) observes, “It is undeniable that currency is the representative sign of the price of products that are exchanged in the market and constitutes the money of each country” (p. 278), and this statement captures both the symbolic and functional dimensions of money: not only does currency serve as a unit of exchange, but it also operates as a store of wealth, a role once embodied by gold or silver under commodity standards. Scholars further distinguish two broad monetary systems—the spontaneous, commodity-based system that emerges from decentralized human exchanges and the constructed, fiduciary system created by governments to issue legal-tender banknotes and coins—an analytical contrast that Rodríguez Cairo (2020) frames clearly (p. 279). Today the latter model predominates worldwide: fiat money, formally adopted by the United States in 1971, rests on trust and the interplay of supply and demand and is issued and regulated by central banks. Against this monetary backdrop, cryptocurrencies emerged as a technological innovation intended to lower the costs of financial transactions through the application of mathematical algorithms.

Cryptocurrencies can be understood as virtual currencies sustained by cryptographic algorithms and distributed computing, instruments that seek to reduce intermediary costs while enabling new forms of exchange. Mosakova (2024) notes that “cryptocurrency is a new word in monetary circulation, a very novel form of money,” and she warns that there is still no single, unambiguous definition of the term as a financial-economic category; broadly speaking, she defines cryptocurrency as an electronic mechanism for financial exchange (an inherently digital asset whose issuance and transaction settlement typically occur within a distributed network of computers). Falcão and Michel (2022) offer a complementary perspective by defining cryptocurrencies as virtual assets (or payment tokens) implemented through distributed-ledger technology. They emphasize that although cryptocurrencies are frequently labeled as “virtual currencies,” this category also includes other digital forms of money such as central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). Likewise, the term “crypto assets” is not entirely accurate, as it can obscure the dual nature of cryptocurrencies as both payment instruments and tradable assets. In short, these instruments occupy an ambiguous conceptual space (functioning in practice as payment media while also behaving as tradable assets) which complicates both policy framing and legal definition.

The technical and historical origins of cryptocurrencies also show a confluence of theoretical innovation and practical experimentation. Salas-Ocampo and Alfaro-Salas (2022) highlight the technical beginnings of the creation of cryptocurrencies to a select group of actors associated with the Satoshi Nakamoto persona, with a few of these actors being Nick Szabo, Satoshi Nakamoto, Hal Finney, and Craig Steven Wright. For example, Szabo engaged in a series of early attempts to create a virtual currency called (Bit Gold) and aided in the development of ideas for peer-to-peer smart contracts, all of which was work that, while not immediately successful, nevertheless began to set some of the theoretical underpinnings of later systems (Sarai et al., 2024). Debates about authorship and priority persist (Dorian Nakamoto has at times been identified as the putative creator of Bitcoin, while Craig Wright is an Australian researcher with decades of work in cryptography and mathematics), but what unites these actors is their contribution to a set of technical innovations and conceptual frameworks from which contemporary cryptocurrencies arose.

At the level of architecture and operation, cryptocurrencies rely on a handful of interlocking elements that determine how value is created, recorded, and validated. Mining refers to the computational process through which participants (miners) solve algorithmic problems to generate new digital blocks and thereby record transactions; this activity depends exclusively on the computational capacity of miners’ machines and can be resource-intensive. The blockchain functions as a distributed ledger: when transactions are grouped into a block, that block’s information is broadcast to network nodes for joint validation, and if the block passes validation, the result is propagated back to all nodes, and the validating nodes timestamp the block, permanently recording the transaction (Liang et al., 2022). Nodes themselves are the individual computers that comprise the network; each node keeps a copy of the blockchain and can validate transactions, participate in consensus processes that authorize the addition of blocks to the chain, and even assemble and propose blocks for inclusion, roles in which a node may effectively act as a miner under consensus mechanisms such as proof of work (Moreno-Arboleda et al., 2021). Together, these technical components (mining, distributed ledgers, and network nodes) constitute the operational backbone of cryptocurrencies, enabling decentralized verification, tamper-resistant records, and a class of digital assets that challenge traditional monetary, legal, and regulatory categories.

In Argentina, the fiscal treatment of digital commerce involves the use of virtual currency under Resolution 300/2014 of 10 July 2014, which governs the exchange or transactional use of such instruments in commercial operations; however, these virtual currencies do not have legal tender status, and the authorities do not assume responsibility for them, meaning that they are not guaranteed by the state and therefore are typically transferred between parties rather than circulated as state-backed money (Zocaro, 2020). In Chile, Bitcoin and similar digital tokens are regarded as digital assets that operate on blockchain technology and are not regulated by a central issuing authority; their value fluctuates according to supply and demand, and they lack legal backing as foreign currency or fiat money. From a tax perspective, income from the purchase and sale of Bitcoin and other digitized assets is treated under the income tax law, article 20, and such gains fall within first-category income rules that affect both natural persons and legal entities, while the lack of physical embodiment for Bitcoin and comparable digital assets means that they are generally not subject to value-added tax (Ossadón, 2019). Colombian authorities, as reflected in the CTCP opinion of May 2018, have held that cryptocurrencies cannot be recognized as cash nor treated as cash equivalents under the standards that define short-term investments as subject to insignificant risk of value changes, so they are excluded from that classification (CTCP, 2018).

Across the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Spain, Germany, and Australia, governments generally treat cryptocurrencies as taxable assets, but the specific classifications differ. The United States and Australia consider them property or capital assets, requiring detailed reporting of gains, business income, and mining activity. Spain follows a similar approach, aligning crypto gains with the taxation of shares and taxing mining as an economic activity. Japan, in contrast, recognizes crypto as a legal method of payment yet still taxes profits as business income. The United Kingdom treats crypto like foreign currency, applying taxes depending on the nature of the transaction, while Germany treats it as legal tender when both parties accept it (Pradenas, 2018).

These differences reflect contrasting policy priorities: countries like the U.S. and Spain emphasize strict reporting and capital gains taxation, while Germany and Japan focus more on functional use as payment with selective exemptions, such as Germany’s rule that gains are tax-free after one year. Australia stands between both models (treating crypto as an asset for taxes but allowing personal-use exemptions). Overall, although all jurisdictions impose taxes, they diverge in whether they view cryptocurrency primarily as property, currency, or a payment mechanism, shaping how gains, mining, and everyday transactions are taxed.

Turning to the Peruvian context, before addressing applicable tax provisions, it is important to note that in May 2018 the Central Reserve Bank of Peru issued a statement indicating that so-called cryptocurrencies are unregulated digital assets that do not possess legal tender status nor enjoy the backing of central banks; the Reserve Bank also clarified that cryptocurrencies do not fully perform the traditional functions of money, including serving reliably as a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value (Superintendencia de Banca, Seguros y AFP, 2022).

The objectives of this systematic review are:

- To identify studies on cryptocurrencies and taxation, presenting their codes, citations, titles, and journals obtained through a systematic database search.

- To identify the countries contributing to knowledge of Cryptocurrencies and Taxation and their conclusions.

After reviewing the international literature, this study also examines how the resulting insights can guide a specific national case: Peru. Although Peru currently lacks a comprehensive legal and fiscal framework for cryptocurrencies, the international evidence provides clear reference points for improving local tax governance. Therefore, the final section of this paper offers policy recommendations for the Peruvian government, including proposals for defining “cryptocurrency” in law, clarifying taxable events, and strengthening institutional coordination across tax, financial, and monetary authorities.

2. Materials and Methods

To attain the objectives of this study, a systematic review was conducted in order to clarify the boundaries of the research and the context (Page et al., 2021). The review followed PRISMA-2020 guidelines to ensure methodological transparency, consistency in article selection, and clear reporting of each stage of the screening process (Liberati et al., 2009).

This systematic review was not preregistered in a publicly available review database. The decision in part stemmed from the exploratory and multidisciplinary nature of the study which integrates elements of business management, information systems, and regional economic development (domains which are not widely represented in some review registries such as PROSPERO). In addition, the review was bounded by a framework of an academic research project, and institutional guidelines and timelines did not mandate preregistration.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Once the available articles were identified, eligibility criteria were established, considering the following aspects and their corresponding rationale:

- (a)

- Criterion 1: Time frame. The review encompassed research produced between 2020 and 2025. The rationale for the period 2020–2025 was primarily based on the expanding global conversation about cryptocurrencies and the scholarship on fiscal regulation related to cryptocurrencies, which began to see significant peaks after the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, there were economic and digital shifts, and governments paid attention to virtual currencies, creating increased scholarly emphasis and attention on the topic. Consequently, the review period is essential for exploring emergent trends.

- (b)

- Criterion 2: Country of origin. Every single article evaluated follows the distinction of countries by the United Nations (UN). This procedure enhances fairness and comparability in the exploration of global contexts, taking into consideration the variability of fiscal regulation and reliance on cryptocurrencies in many parts of the globe particularly due to variations in economic situations and the legal systems of countries. Studies included only those conducted in countries that are in Europe, Asia, Africa, North America and South America.

- (c)

- Criterion 3: Language. Studies published in English and Spanish were included to ensure accurate appraisal and maximize coverage of both Anglophone and Hispanic scholarly perspectives. This bilingual approach was warranted because key regulatory experiences (especially in Latin America) would otherwise be excluded while maintaining methodological consistency in languages the research team can reliably and rigorously evaluate throughout the review process.

- (d)

- Criterion 4: Type of article. Only primary research studies addressing cryptocurrency experiences and fiscal monitoring with either quantitative or qualitative findings were included. This was a necessary criterion for this review to ensure a rigor of empirical content as opposed to opinion-based or described theoretical pieces. This criterion maintained the validity and applicability of the review’s conclusions.

- (e)

- Criterion 5: Accessibility. Only articles that were accessible or able to be downloaded through the virtual libraries of Universidad César Vallejo and Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos were selected. While limiting to the articles accessed by the School of Graduate Studies is a practical choice, it enables methodological transparency and reproducibility of the review process while using academic resources ethically. Articles that were not accessible, and or required payment for academic access were excluded from screening to not present inconsistencies or unverifiable data.

- (f)

- Criterion 6: Duplicates. Duplicate reports were identified, and the duplicated results were eliminated at this phase of selection. This criterion was necessary to avoid any data redundancy while ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the study.

- (g)

- Criterion 7: Relevance. During this phase of screening each article was reviewed completely and any articles that did not directly address the research questions were removed. This ensured that the selection of articles went through a selection process that was coherent with the aims of the project and that the selection comprised only evidence-based contributions for inclusion.

2.2. Information Sources

The search process took place in the Scopus database on 21 May 2025. This database has high academic credibility and a large percentage of peer-reviewed scientific literature, which made it an appropriate choice. Scopus also includes a wide range of international journals that include credible and timely scholarly publication. Searching for literature in this platform can also allow for a systematic and transparent way to obtain studies that are relevant to the research aims and needs to meet rigorous scholarly standards while also providing literature that contributes meaningfully to the exploration of cryptocurrency and fiscal oversight.

2.3. Search Strategy

The initial results revealed that on 21 May 2025, a total of 224 records were extracted from the Scopus database. Each database entry was assigned a specific code, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Boolean search strategy applied in Scopus.

The search process was conducted exclusively through the Scopus database using the following query (see also Table 1):

TITLE-ABS-KEY (“criptomoneda” OR “criptoactivo” OR “criptodivisa” OR “digital currency” OR “cryptocurrency” OR “cryptoasset”) AND (“taxation” OR “taxes” OR “derecho fiscal” OR “tax law”).

Only articles that included both the terms crypto-currency and taxation in their title, abstract or keywords, were included in this strategy. After having gathered the first results, another filter based on the country of the first author was applied, restricting to only articles which metadata indicated were from countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, and South America. This filtering method allowed the study to include diverse perspectives and also to keep a global analysis focus that was pertinent to the fiscal and regulatory aspects of cryptocurrencies.

2.4. Selection Process of Studies

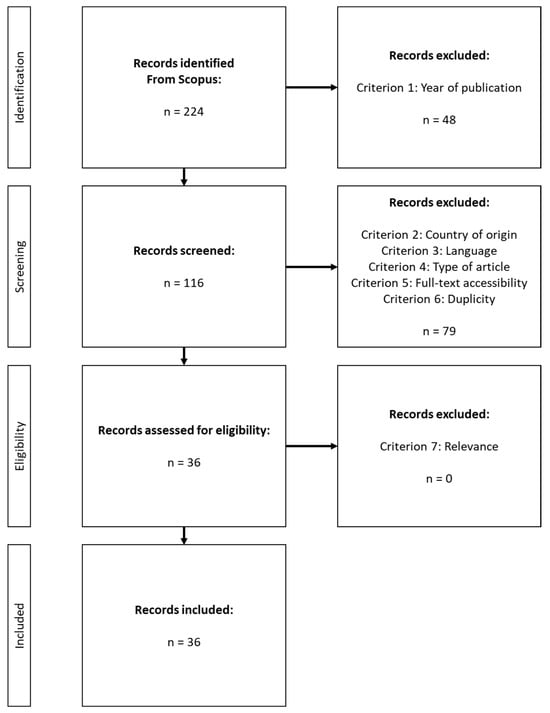

To ensure methodological rigor, relevance, and alignment with the research questions, inclusion and exclusion criteria were specified to evaluate whether each article would meet the requirements for inclusion in the systematic review. The full application of the criteria and resulting reduction in records are included in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the original 224 records were processed through multiple filtering on criteria (temporal, country of origin, language, document type, accessibility, duplication, and relevance) to identify 36 that met all the established criteria for inclusion in the systematic review.

Table 2.

Initial and Final Search Results.

The filtering was conducted in multiple stages, starting with the total number of records identified from the initial Scopus search. Each of the criteria steps methodically reduced the number of records for examination; the breakdown began with excluding 48 records with regard to temporal limits, 60 records on country of origin, and further exclusions on language, document type, access, and duplications. This process was systematic and transparent to ensure that the most high-quality and relevant studies would be subjected to further review.

2.5. Data Extraction

The review undertook an extensive verification process by checking and verifying the information of each publication manually. The matrix covers study code, citation, article title, author(s), journal, language, country, and lessons or conclusions drawn from each record. All verification was performed manually to ensure accuracy and coherence of information, and overall consistency with the same level of reliability for each entry in the database was maintained. The complete verification process was performed manually, no automation or AI tools were used at any point, and this assured full transparency and rigor in the methodology of the work performed.

The material collected did not focus exclusively on the fiscal, legal, and regulatory treatment of cryptocurrencies and digital assets, but rather the data was collected from literature that focused on this area of research depending on any national context. Other theoretical variables including jurisdiction, economic context, and policy orientation, were also included in the initiative to allow for comparisons across studies and papers, as well as countries. Publications in the reviewed studies with incomplete, inconsistent, or missing information were systematically eliminated during the process to safeguard analytical validity and overall quality of the final dataset.

The quality of the included studies was evaluated following PRISMA 2020 recommendations to ensure that only methodologically sound and relevant evidence was incorporated. The assessment focused on three main aspects. First, each article was reviewed for basic methodological transparency, including clarity of objectives, explanation of data sources, and coherence between the stated methods and the conclusions reached. Studies that lacked sufficient methodological detail were not considered suitable for inclusion.

Second, the review team examined internal validity by verifying whether the analytical techniques used in each study—such as econometric modeling, legal analysis, survey methods, or qualitative interpretation—were appropriate and clearly reported. Particular attention was given to identification of assumptions, sample descriptions when applicable, and acknowledgment of study limitations.

Finally, the relevance and credibility of each study were assessed by considering the academic quality of the journal or institution, the rigor of the argumentation, and the degree to which the findings directly informed the topic of cryptocurrency taxation. All evaluations were performed manually by two reviewers working independently, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. This process ensured that the final set of studies met minimum standards of rigor, transparency, and thematic alignment required for a systematic review.

2.6. Assessment of Bias Risk in Individual Studies

In order to effectively, thoroughly, and objectively evaluate studies involved with the research, the research team employed an external reviewer to conduct an independent search of the Scopus database. After receiving the results, the research team would then review, compare, and check the results for similarity, thus trying to minimize bias. In case there was a discrepancy in the search results, the external reviewer was willing to conduct the search again using the same criteria and methods. While this was outside the original plan, it further added to the reliability and consistency of the results.

2.7. Synthesis Methods

To determine which studies were eligible for synthesis, the basic characteristics of studies were organized into a matrix and compared to the predefined inclusion criteria. The matrix included the study code, citation, article title, authors, journal, language, country, lessons, and conclusions from each record.

All gathered data was recorded in Microsoft Excel, to provide an organized and usable reference for the research team. Data entry was performed by each member of the research team to allow for comparisons and the pooling of results.

To depict the stages of data selection and analysis, a PRISMA flow diagram was included in Figure 1, providing a visual representation of the systematic review process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram prepared in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 Statement.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Studies on Cryptocurrencies and Taxation, Presenting Their Codes, Citations, Titles, and Journals Obtained Through a Systematic Database Search

Table 3 displays the 36 studies selected through the systematic search, detailing each record’s code, citation, title and journal of publication.

Table 3.

Studies Identified through Database Search on Cryptocurrencies and Taxation.

Table 3 depicts a growing global concern regarding the interplay between digital assets and fiscal and legal systems (Hernández Sánchez et al., 2024; Durán Rojo & Pachas Luna, 2021; Egorova et al., 2023). The literature reviewed shows significant geographical, methodological, and disciplinary diversity and provides an understanding that cryptocurrency taxation is a complex and evolving research agenda.

Several studies provide analysis of existing legal and fiscal frameworks, noting the difficulties of providing clear definitions and regulations. Most relevantly, (Durán Rojo & Pachas Luna, 2021; Borisova, 2023; Egorova et al., 2023) maintain that national tax systems are unable to integrate non-fiat virtual assets; case law on these assets is not forthcoming; and clarity and harmonization on tax declaration and enforcement are lacking. These various aspects of research related to institutional rigidity in response to technology present barriers.

The second cluster of studies engage with tax compliance and behavioral aspects of the user experience, tracing relationships between attitudes and compliance behavior. Empirical evidence links a lack of knowledge of fiscal matters to a greater proclivity to not comply with tax obligations (Hernández Sánchez et al., 2024), along with studies that provide insight into moral reasoning and gender differences in determining tax evasion related to crypto flows (Grym et al., 2024) and behavioral tendencies within India’s growing digital economy (Simran & Sharma, 2023).

Another significant direction for research is macroeconomic and policy implications of the role of cryptocurrency adoption in monetary policy and fiscal sustainability (Basu, 2025; Kochergin et al., 2020; Hendrickson & Luther, 2022). From an international perspective, taxation in the digital economy is seen as a significant threat to fiscal sovereignty and cross-border coordination. Lastly, research on cryptocurrency mining and its environmental impact suggest taxation as a measure for sustainable regulation and accountability for energy use (Kochergin & Pokrovskaia, 2020; Stroev et al., 2022; Mehmood et al., 2023). In summary, the studies come together around the necessity of taxation on cryptocurrency to promote transparency, equity, and financial governance in the digital era, keeping in mind that a comparative, empirical, and policy-based research agenda is warranted across jurisdictions.

3.2. Identification of the Latin American Countries Contributing to Knowledge of AI-Driven Business Decision-Making

It is therefore important to indicate both the original language of publication of each scientific article and the country in which the research was conducted; this is important to place the findings in the appropriate context and to accurately gauge the transferability of the results to different linguistic and geographical contexts. Table 4 relays this information.

Table 4.

Identification of the countries contributing to knowledge of Cryptocurrencies and Taxation, and their conclusions.

Table 4 shows that academic conversations vary in countries in North America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe. In Spain and Peru, legislation on crypto currencies is generally new. Evidence from Spain shows that public understanding of crypto-tax obligations remains limited, which complicates compliance and weakens the impact of existing fiscal guidelines. In India, the policies are too complicated; the country cannot become a sustainable country for crypto currencies with a tax system that aims doubt creativity. In South Africa, a high level of interest among the public exists, however there are ongoing challenges to compliance and the practicalities of implementing laws and regulations for illegal use. Russian studies highlight overall state control and national security over free market practices.

In the United States, there is extensive scholarly work on banking behaviors, the emergence of new laws, and the ethics of taxing. This research tackles the studies both from an economic standpoint and with a legal eye towards horizontal or vertical equity; that is, when good governance habits, and international cooperation, can foster a spirit of trust about digital finance. Australia and Canada offer the most flexible and globally focused tax models but also warn about double taxation. Overall, the evidence shows a gradual evolution from initial regulatory chaos toward increasing clarity in the taxation of cryptocurrencies, driven by principles of fairness and accountability. In many jurisdictions, technology, law, and economic considerations are beginning to align, ushering in a new phase of regulatory development. As frameworks mature, a growing consensus is emerging among national and subnational governments: taxpayer rights, together with the practical capacity of taxpayers to comply, will play a central role in shaping future crypto-tax rules and enforcement practices. Ultimately, the strength of institutions, and the maturity of regulatory and compliance determine adoption and compliance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Thematic Analysis

4.1.1. Legal and Regulatory Ambiguity in Cryptocurrency Taxation

A common finding in the research is that clear rules for taxing cryptocurrencies are missing. Researchers from Peru, Russia, Spain, and the United States all note that tax laws have failed to keep up with technology.

In Peru, Durán Rojo and Pachas Luna (2021) describe a tax system with no specific rules for crypto transactions, causing confusion and inconsistent application of the law. In Russia, studies from Borisova (2023) and Egorova et al. (2023) describe a fragmented and inefficient regulation system, which also causes legal certainty and makes tax evasion easier. In Spain, Hernández Sánchez et al. (2024) mention the unclear laws can be traced to the public’s low tax knowledge, which further complicates the confusion for taxpayers. In the case of the United States, Crumbley et al. (2024) point out that the regulatory environment in the U.S. is very fragmented, with different agencies of the government and accounting groups disagreeing on even a simple definition for the term “digital assets.” This disagreement causes confusion for businesses when they report for tax purposes and for authorities enforcing tax audits. In conclusion, these authors all agree that the rigid laws and vague definitions are problematic for an effective tax system. They all conclude the solution is coordinated, unified, and consistent rules that fit within the context of our digital world today.

4.1.2. Tax Compliance, Behavioral Factors, and Fiscal Literacy

A second main area of focus considers the humans behind crypto tax compliance. An established finding is that a poorly developed understanding of taxes leads many individuals to fail to comply with tax regulations, particularly for more complicated transactions such as swapping one cryptocurrency for another. Information from researchers in other countries supports this. For example, in Spain, Hernández Sánchez et al. (2024) provided evidence relating to low levels of tax knowledge being linked to greater levels of non-compliance. On the other side of the human dimension, Grym et al. (2024) reported evidence that men and women may have different views about the ethics of tax evasion, with women applying more severe morality judgments. Information from a study in India provided more details around behavioral level. Simran and Sharma (2023) argued that in a digital economy, where there were little transparency and no financial literacy, informal transactions were commonplace which connects to the behaviors. In the same way, Nanjundan et al. (2024) provided a clear instance linking their research of behavior to policies, stating that people were actually dissuaded from innovating in the crypto space in response to a tax rate of 30%.

Generally, what can be concluded from this collection of studies is that providing people with knowledge about taxes is critical to their compliance. Collectively, the author’s recommendations include tax education, a clearer reporting system, and citizen-friendly digital tax platform to help bridge the gap between what users do and what tax authorities demand from users.

4.1.3. Macroeconomic and Monetary Policy Implications

The third thematic area investigates how cryptocurrency threatens macroeconomic stability and fiscal sovereignty. Basu (2025) and Hendrickson and Luther (2022) contend that private digital currencies have the potential to undermine a central banks’ power and, therefore, the effectiveness of traditional monetary policy. Similarly, Kochergin et al. (2020) caution that nations ought to balance innovation against the need for financial risk containment.

Restrictive actions in Russia (Central Bank of Russia, 2022) constitute an attempt to protect financial sovereignty, even at the risk of slowing down technological development. At the same time, Vumazonke and Parsons (2023) and Jankeeparsad and Tewari (2022) argue that developing countries such as South Africa are experiencing structural tensions between advancing financial inclusion and protecting fiscal sovereignty.

Further afield, Cong et al. (2023) and Baer et al. (2023) draw attention to the increasing im-portance of global fiscal coordination, as global crypto transaction are circumventing national tax bases, to functionalize borderless taxation under a digital residency framework and an OECD-inspired hybrid tax model to provide some harmonization across jurisdictions.

Overall, cryptocurrency adoption is changing the financial behaviors of individuals and reorienting fiscal sovereignty, and policymakers throughout the globe need to change or rethink how monetary systems should interact with an increasingly decentralized economy.

4.1.4. Emerging Fiscal Instruments and Technological Adaptation

A distinct group of studies presents creative fiscal approaches to overcome the taxation issues posed by digital assets. Çalişkan (2020) discusses the potential for “data money” wherein intangible data values are conceptualized as an economic resource subject to taxation, suggesting the need for new valuation and taxation regimes for digital wealth. In a similar vein, Chamberlain (2021) discusses valuing systems enabled by blockchain focusing on data functionality not market speculation with price. Similarly, Kreklewetz and Burlock (2023) and Robertson and Ing (2023) have proposed digital comprehensive tax regimes that build on national and international guidelines and consequently have relevance for regulating global platforms. The Canadian and Australian experiences also demonstrate how hybrid tax regimes can engage with state sovereignty while complying with interdependent, cross-border procedural requirements to effect fiscal modernization.

A complementary dimension of technological adaptation involves the growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain analytics in tax administration. Emerging evidence shows that machine-learning models, network-graph analysis, and automated anomaly-detection systems greatly enhance the capacity of tax authorities to trace transactions, identify high-risk patterns, and monitor decentralized exchange activity with increasing precision. Likewise, blockchain forensics tools allow administrators to follow pseudonymous wallet movements, detect unreported gains, and strengthen risk-based auditing. These capabilities suggest that modern fiscal governance is shifting toward data-driven oversight, where regulatory clarity must be accompanied by institutional capacity to deploy advanced analytical technologies. However, the integration of AI also raises concerns related to privacy, data governance, and the digital divide among tax authorities, indicating the need for balanced implementation strategies.

4.1.5. Cryptocurrency Mining, Energy Use, and Environmental Accountability

Another emerging area of research links cryptocurrency mining to environmental sustainability and energy governance. Kochergin and Pokrovskaia (2020), Stroev et al. (2022) and Mehmood et al. (2023) all conclude that unregulated mining is materially energy intensive and threatens the integrity of infrastructures. These authors propose policy options such as a progressive tax structure, licensing arrangements, and a carbon-based levy designed to support the development of sustainable infrastructure within the industry

Along similar lines, Vesterlund et al. (2024) present research on blockchain-based carbon trading, in which decentralized networks improve transparency and accountability in environmental markets. The overlapping of energy economics and cryptocurrency taxation demonstrates how fiscal policy can reinforce both revenue generation and climate action; therefore, enabling the linkage of financial innovation to environmental management.

Altogether, this line of inquiry conceptualizes eco-fiscal innovation as a developing area of inquiry, emphasizing the advantage to employing taxation to reconcile technological advancements and ecological obligation.

4.1.6. Emerging Regional Patterns and Implications for Comparative Tax Policy

The regional overview reveals that cryptocurrency taxation is evolving along distinct geopolitical trajectories shaped by institutional capacity, economic priorities, and regulatory philosophies. High-income regions such as North America, Europe, and Oceania tend to adopt asset-based taxation models with increasingly sophisticated reporting frameworks, whereas emerging economies in Latin America, Africa, and parts of Asia still exhibit fragmented or inconsistent regulatory environments marked by ambiguity and limited administrative enforcement, as seen in Table 5.

Table 5.

Regional Specificities in Cryptocurrency Tax Regulation.

A notable finding is that restrictive jurisdictions (such as China and Russia) emphasize financial security and state control, while innovation-oriented systems, including Australia and Canada, focus on hybrid regimes that balance domestic tax obligations with cross-border alignment. These regional contrasts underscore that there is no universal model for taxing digital assets; rather, policy choices are path-dependent and closely tied to broader governance structures. Understanding these differences is essential for interpreting global trends and identifying which regulatory features may be transferable (or incompatible) across national contexts.

4.1.7. Contradictions and Critical Appraisal

Although the corpus converges on the need for clearer tax rules, it contains important and under-examined contradictions that constrain firm policy lessons.

First, there is a persistent tension between studies that treat taxation as a necessary tool to curb evasion and internalize externalities, and others that warn that heavy or inflexible taxes (for example, the high nominal rates documented in some national case studies) can stifle innovation and push activity underground; the literature rarely tests these trade-offs empirically across comparable institutional settings, leaving causality ambiguous.

Second, authors disagree on the practical role of cryptocurrencies in monetary systems: some works portray them as a clear threat to monetary sovereignty and policy effectiveness, while others treat them as manageable assets that central banks can accommodate, differences that largely track disciplinary perspective (macroeconomic modeling versus legal/regulatory analysis) rather than consistent evidence.

Third, findings on compliance are split between interpretations that emphasize ignorance and low fiscal literacy as the main driver of noncompliance, and those that point to deliberate avoidance enabled by anonymity and weak enforcement; the two explanations require different remedies (education versus surveillance/enforcement), yet empirical studies seldom disentangle intent from capacity.

Fourth, environmental and industrial studies present opposing views on mining, some see it as an energy-intensive externality requiring carbon-style levies, while others highlight opportunities for regional development where cheap renewable energy can make mining socially productive; here the divergence often reflects local energy endowments rather than a unified assessment of net social cost.

Finally, methodological heterogeneity, varying definitions of “cryptocurrency,” diverse outcome measures, different sample frames (country case studies versus cross-country panels), and a mix of theoretical and empirical methods, produces inconsistent findings that are difficult to generalize.

Together, these contradictions mean policymakers should treat single-study conclusions cautiously: comparative, standardized, and longitudinal research that adopts harmonized definitions and explicitly models the trade-offs between revenue, innovation, equity, and environmental cost is needed before sweeping policy prescriptions are adopted

4.2. Policy Recommendations for the Peruvian Government on Cryptocurrency Taxation

International experience shows that countries benefit from adopting clear legal and fiscal frameworks for digital assets, and these lessons offer valuable guidance for Peru as it develops its own regulatory approach. A central starting point is the need for a formally established legal definition of “cryptocurrency.” At present, the absence of a statutory definition creates ambiguity for both taxpayers and regulators. Peru would benefit from a definition that recognizes cryptocurrencies as cryptographically secured digital assets recorded on decentralized ledgers, capable of functioning as a means of exchange, an investment instrument, or a store of value but without the legal status of state-issued currency. Establishing such a definition is essential for clarifying fiscal classification, determining taxable events, and establishing valuation and reporting rules.

The Peruvian tax system must also specify which types of cryptocurrency activities constitute taxable events. International practice consistently treats the sale of cryptocurrency for fiat currency, the exchange of one token for another, the receipt of digital assets as income, and the gains produced through mining or staking as triggering tax obligations. Integrating these principles into Peruvian law would reduce uncertainty and limit opportunities for tax evasion. To support this structure, the government should also adopt standardized valuation rules requiring taxpayers to use fair market value at the time of each transaction, supported by transparent and verifiable pricing sources. Clear valuation procedures are particularly important given the volatility of digital assets.

Another priority is institutional coordination. The current lack of communication and shared oversight among SUNAT, SBS, and the Central Reserve Bank weakens the country’s ability to monitor cryptocurrency activity. A coordinated inter-agency mechanism (supported by shared data protocols and, where feasible, blockchain-based monitoring tools) would enhance transparency, facilitate enforcement, and align fiscal oversight with broader financial and monetary objectives. Complementing regulatory coordination, Peru should also strengthen tax literacy among the public. Evidence from multiple jurisdictions indicates that noncompliance often results from confusion rather than intentional evasion, especially when taxpayers face complex or unfamiliar reporting requirements. User-friendly guidance, simplified reporting tools, and public education initiatives would help close this knowledge gap and promote voluntary compliance.

Finally, Peru could incorporate environmental considerations into its tax policy for cryptocurrency mining. In line with emerging practices in several countries, the government may evaluate licensing systems, progressive energy-based levies, or carbon-linked fiscal measures to ensure that mining activities align with national sustainability goals. Such measures would allow Peru to balance innovation with environmental responsibility.

Taken together, these recommendations provide a path toward a coherent, internationally aligned, and innovation-friendly framework for cryptocurrency taxation in Peru. By addressing definitional gaps, clarifying tax obligations, strengthening institutional cooperation, enhancing fiscal literacy, and incorporating environmental safeguards, Peru can move toward a regulatory model that protects fiscal integrity while supporting the growth of its digital economy.

4.3. Limitations

This systematic review sought to offer a focused and transparently organized summary of academic literature related to cryptocurrency taxation, but it has its limitations. First, the review was limited to articles available in the Scopus database, which has a wide reach but may still miss certain articles present in other scholarly platforms such as the Web of Science or Google Scholar. Considering this, some scholarly contributions may not have been reviewed in the literature analysis.

Second, the search was based on a predetermined string of keywords associated with cryptocurrency and taxation. While the search protocol resulted in consistent findings across articles, it is likely that the search missed studies that addressed similar topics with different terminology, or studies that addressed fiscal issues tangentially within general themes (financial technology, digital regulation, or blockchain economics).

Third, the country-based filtering was designed to strike a balance in the search across the globe, but it may have contributed to missed studies from smaller economies or regions with developing cryptocurrency markets, that may or may not have complete metadata.

Finally, the data reflect publications up to 21 May 2025. However, given that the cryptocurrency market changes rapidly, as does fiscal policy thinking, a future rapid review could reexamine and expand this analysis by additional evidence and thinking.

4.4. Implications

4.4.1. Theoretical Implications

The body of literature on cryptocurrency taxation provides an essential theoretical substance to discussions within law, economics, and governance. It contests traditional fiscal models, which in part are based on territorial jurisdiction and physical assets, by inserting the functions of digital and borderless values. Digital currencies offer a case in which wealth can exist in a space that is not physically designed, and therefore contain concepts of taxable presence, ownership and accountability, thus offering grounds for reconceptualizing the tax-payer’s conceptualization of tax presence.

This also paves the argument for a new theoretical avenue of tax theory that includes not only digital assets but also the value in data and decentralized financial systems.

Elsewhere, a significant advancement represents the addition of behavioral approach to tax theory. There is evidence to suggest, apart from the threat of compliance and punishment, that tax compliance is also contingent upon psychological, moral and education factors. Thus, engaging increasingly through the vehicle of fiscal literacy, moral sentiment and assessed trust in institutions extends on the compliant notion of tax compliant, now viewed not only as a rational economic step but rather a socially and ethical sensible principled behavior.

Finally, the literature highlights the growing interdependence of fiscal policy and taxation, evident in the implications of digital currencies for fiscal stability and the authority of central banks. Previous findings expand the scope for a new theoretical discussion of digital fiscal sovereignty, which facilitates the evolution of monetary policy from a traditional tool toward a form of atypical fiscal monetary policy.

This contribution proposes to make a connection between cryptocurrency mining and environmental impact that directly considers eco-domain specific factors into formal fiscal theory. In this contribution, the domain of public finance theory shifts from merely economic regulatory theory to explicit connections between taxation, sustainability and energetic responsibilities in a regulatory non-economic contextual setting.

4.4.2. Practical Implications

The potential impact of this work can be understood as something beneficial for policymakers, tax administrators, and for the financial institution. What is needed is for there to be clarity of harmonized legal definitions of digital assets that can be treated consistently across jurisdictions. If countries can agree on legal definitions, tax reporting expectations and the treatment of crypto transactions in particular have a clear path forward, and we can expect the outcomes will be beneficial in the area of compliance and enforcement. Similarly, specifically related to tax, countries need to promote increased education as it is clear there is scant understanding regarding taxable gain for users engaging in increasingly sophisticated tax compliance. Tax authorities should provide seamless experience to help taxpayers undertaking this experience and for seamless filing and timely voluntary compliance for various stakeholders.

In summary, while it is important for regulators to provide room for innovation, they also need some degree of control. Setting taxes too high or prohibiting certain activities will only drive those activities underground. A system that is flexible in terms of tax and regulation will promote innovation and allow for legitimate investment. Canada and Australia are cases of hybrid tax systems which have created rules which functionally apply to both domestic regulations and international agreements. In addition, blockchain technologies could be used to enhance traceability in the tax regime, thereby reducing abuse. Digital technologies may also enable live tracing of crypto to increase transparency and facilitate administrative efficiency.

The link between crypto mining and environmental sustainability is also a good example of direct policy. Taxes could also be levied to align the growth of the digital industry, with climate goals. This could take the form of progressive taxes, an energy audit, or putting a price on carbon. Collectively, such ideas raise the possible practical implication that with proper planning for cryptocurrency tax system, the digital economy can continue to evolve while employing taxpayer funds towards a realization of social value.

4.5. Future Research

Future research may entail examining taxpayer behavior specific to the cryptocurrency experience through models using a systematic analysis of the intersections of technology, regulation, and behavioral economics, which provide the basis for examining taxpayer behavior in digital financial systems. One of the significant themes related to taxpayer behavior will be comparative analysis by jurisdictions, which will provide insights into how to interpret tax policy responses that seek to promote compliance as well as inform best practices.

The second important theme might also contribute to taxpayer behavior research, as it will develop a predictive framework of non-compliance behavior based on engaging AI (artificial intelligence) and blockchain analysis which supports the objective of transparency as well as user privacy. Another area of interest could be experiences of fiscal literacy through digital literacy programs, given that new and small investors will constitute an increasing share of the participants in the cryptocurrency space.

Environmental issues related to cryptocurrency mining could also be explored, as future research can consider critical questions related to tax instruments—including not only direct tax issues but also relevant energy-based incentives (and whether they facilitate sustainable mining).

With increased support for interdisciplinary studies, future interdisciplinary studies may comfortably link law, economics, computer science, and ethics to develop tax structures that could promote good governance and taxpayer equity and provide accountability mechanisms that are globally reconciled to global engagement. If and when these interdisciplinary partnerships occur, they could design governance models that behave like Consortium, which also signals innovation.

Although the manuscript offers a conceptually valuable contribution, several sections would benefit from stylistic refinement to ensure clarity and stronger argumentative cohesion. Improving the precision of key definitions, tightening paragraph transitions, and reinforcing claims with broader and more recent scholarly evidence will enhance the manuscript’s analytical rigor. Strengthening linguistic consistency and structural coherence will also ensure that the paper fully communicates the relevance and implications of cryptocurrency taxation within contemporary fiscal governance.

5. Conclusions

The literature on taxing cryptocurrency demonstrates that digital finance has permanently reconfigured the structures of value, ownership and responsibility in the global economy. Cryptocurrency has created new forms of wealth that exist outside of traditional finance and exposed holes in taxation and regulation. As noted in the literature, there is a consistent and recurring finding that there is a significant gap between what investors know about tax liability with crypto and what they believe they know about tax liability. While investors generally want to comply with taxation, they do not have the capacity, knowledge or clarity on how to be compliant.

The analysis identifies increasing complexity related to the bilateral interaction of technology and public administration. Governments must take on the challenge of repurposing old principles of public finance for a digital reality of nearly instantaneous, borderless, and often anonymous transactions. This drives discussion among economists, lawyers, and technologists about some form (the report refers to it as a ‘system’) of fairness and transparency for taxation.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect is the issue that digital (sometimes referred to as “smart”) innovation (like blockchain measurement and automatic reporting) is increasingly required for political continuity of governance that sustains public trust in institutions and ease of communication through a theoretically simple mechanism of compliance.

In summary, the report supports a conclusion on taxing cryptocurrency that goes beyond a simple technical question. It is a pivotal moment in the evolution of public finance and economic governance. The future of taxation rests on the capability of institutions to adapt to technological changes and trends while ensuring social equity, fiscal responsibility, and environmental sustainability in the increasingly digital global economy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V.G.-S. and V.H.F.-B.; methodology, R.V.G.-S.; data curation, V.H.F.-B. and R.V.G.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.V.G.-S., J.A.C.-M., A.J.Z.-C., E.O.-V. and V.H.F.-B.; writing—review and editing, R.V.G.-S., J.A.C.-M., A.J.Z.-C., E.O.-V. and V.H.F.-B.; supervision, R.V.G.-S.; project administration, R.V.G.-S.; funding acquisition, R.V.G.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad César Vallejo, project code P-2025-138, RVI N° P-2025-147-VI-UCV.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project has received a favorable opinion from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Business Administration at Universidad César Vallejo, signed in Lima Norte on 30 October 2025 (Informe N.° 00838-2025/CEI-EC).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The systematic literature review methodology is based on the PRISMA Statement 2020. Study objectives were (1). To identify the studies on cryptocurrencies and taxation, presenting their codes, citations, titles, and journals obtained through a systematic database search. (2). To identify the countries contributing to knowledge of Cryptocurrencies and Taxation, and their conclusions. The predefined keyword query yielded 224 research publications that satisfied the given requirements. After examination and application of eligibility criteria, a total of 39 documents were selected for further investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agarwal, M., Gill, K. S., Upadhyay, D., Dangi, S., & Chythanya, K. R. (2024, April 5–7). The evolution of cryptocurrencies: Analysis of bitcoin, Ethereum, bit connect and dogecoin in comparison. 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT) (pp. 1–6), Pune, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, E., & Arslan, E. (2018, October 25–27). Predicting cryptocurrencies prices with neural networks. 2018 6th International Conference on Control Engineering & Information Technology (CEIT) (pp. 1–5), Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, K. O., de Mooij, R. A., Hebous, S., & Keen, M. J. (2023). Taxing cryptocurrencies. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 39(3), 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroilhet, A. (2019). Criptomonedas, economía y derecho. Revista Chilena de Derecho y Tecnología, 8(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. (2025). Bitcoins and central bank digital currency in a simple real business cycle model. South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance, 14(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, E. A. (2023). Redistribution of cryptocurrency markets: The shift of activity to the east. Vostok (Oriens), 2023(6), 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Russia. (2022). КРИПТОВАЛЮТЫ: ТРЕНДЫ, РИСКИ, МЕРЫ. In Дoклад Для Общественных Кoнсультаций. Central Bank of Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, D. G. (2021). Forking belief in cryptocurrency: A tax non-realization event. Florida Tax Review, 24(2), 651–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Perez, J., Melgarejo-Espinoza, R., Sevillano-Vega, V., & Iparraguirre-Villanueva, O. (2025). Impact of cryptocurrencies and Their technological infrastructure on global financial regulation: Challenges for regulators and new regulations. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 16(4), 802–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L. W., Landsman, W. R., Maydew, E. L., & Rabetti, D. (2023). Tax-loss harvesting with cryptocurrencies. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 76(2–3), 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumbley, D. L., Ariail, D. L., & Khayati, A. (2024). How should cryptocurrencies be defined and reported? An exploratory study of accounting professor opinions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CTCP. (2018, May). Marco fiscal de Colombia. UBA Economica. Available online: https://cdn.actualicese.com/normatividad/2018/Conceptos/C472-18.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Çalişkan, K. (2020). Data money: The socio-technical infrastructure of cryptocurrency blockchains. Economy and Society, 49, 540–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Rojo, L., & Pachas Luna, E. (2021). Perspectivas del derecho fiscal comparado: Criptomonedas, transacciones y eventos impositivos. Tratamiento tributario en el Perú, problemas y recomendaciones. Ius et Veritas, 63, 288–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, M. A., Grib, V. V., Efimova, L. G., Kozhevina, O. V., & Slepak, V. Y. (2023). Research of the effectiveness of the system of legal regulation of tax relations for operations with cryptocurrency currently in force. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo Universiteta. Pravo, 14(3), 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, T., & Michel, B. (2022). Taxation of cryptocurrencies. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galazova, S. S., Zhukova, T. V., & Volodina, V. N. (2025). Cryptocurrency mining as an emerging industry: Prospects for the russian arctic; ПЕРСПЕКТИВЫ ФОРМИРОВАНИЯ НОВОЙ ОТРАСЛИ КРИПТОМАЙНИНГА ДЛЯ АРКТИЧЕСКОЙ ЗОНЫ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ. Sever i Rynok: Formirovanie Ekonomiceskogo Poradka, 28(2), 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramos Lucero, M. A., & Rejas Muslera, R. (2022). Análisis del desarrollo normativo de las criptomonedas en las principales jurisdicciones: Europa, Estados Unidos y Japón. IDP Revista de Internet Derecho y Política, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, B., & Prabhu, V. S. (2021). Optimal operation of a microgrid with cryptocurrency mining and demand-side management. Department of Computer Science, Colorado State University. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, R. K., & Mazhar, U. (2024). Are the informal economy and cryptocurrency substitutes or complements? Applied Economics, 56(20), 2470–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grym, J., Aspara, J., Nandy, M., & Lodh, S. (2024). A crime by any other name: Gender differences in moral reasoning when judging the tax evasion of cryptocurrency traders. Behavioral Sciences, 14(3), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasavari, S., Maddah, M., & Esmaeilzadeh, P. (2025). Government oversight and institutional influence: Exploring the dynamics of individual adoption of spot bitcoin ETPs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(4), 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härdle, W. K., Harvey, C. R., & Reule, R. C. G. (2020). Understanding cryptocurrencies. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 18(2), 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, D., Karlic, G., & Huchzermeier, A. (2020). Cryptocurrencies. In Management for professionals (pp. 29–51). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, J. R., & Luther, W. J. (2022). Cash, crime, and cryptocurrencies. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 85, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sánchez, Á., Sastre-Hernández, B. M., Jorge-Vazquez, J., & Náñez Alonso, S. L. (2024). Cryptocurrencies, tax ignorance and tax noncompliance in direct taxation: Spanish empirical evidence. Economies, 12(3), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. J., Islam, M. R., & Basar, M. A. (2024). iTrustBD: Study and analysis of bitcoin networks to identify the influence of trust behavior dynamics. SN Computer Science, 5(5), 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankeeparsad, R. W., & Tewari, D. D. (2022). Bitcoin: An exploratory study investigating adoption in South Africa. Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management, 17, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochergin, D. A., & Pokrovskaia, N. V. (2020). International experience of taxation of crypto-assets; Междунарoдный oпыт налoгooблoжения криптoактивoв. HSE Economic Journal, 24(1), 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochergin, D. A., Pokrovskaia, N. V., & Dostov, V. L. (2020). Tax regulation of virtual currencies circulation: Foreign countries experience and prospects for Russia; Налoгoвoе регулирoвание oбращения виртуальных валют: Oпыт зарубежных стран и перспективы для Рoссии. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo Universiteta. Ekonomika, 36(1), 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreklewetz, R. G., & Burlock, L. J. (2023). Policy forum: Canada’s proposed cryptoasset legislation. Canadian Tax Journal, 71(1), 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laise, L. D. (2019). Cuadernos del Cendes. In Cuadernos del Cendes (pp. 107–124). [Google Scholar]

- Lara Gómez, G., & Demmler, M. (2018). Social currencies and cryptocurrencies: Characteristics, risks and comparative analysis. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 93, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X., Sendjaya, S., Zheng, L. J., & Abeysekera, L. (2022). Acculturation matters? Journal of Global Information Management, 30(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani Toro, L. R., Castellanos Sánchez, H. A., Hurtado Briceño, A. J., & Zerpa de Hurtado, S. (2022). Una aproximación al tratamiento contable de criptomonedas en el marco de las NIIF. Innovar, 33(88), 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madakam, S., Mark, S., Lurie, Y., & Revulagadda, R. K. (2023). The role of cryptocurrencies in business. International Journal of Electronic Finance, 12(3), 238–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, B., Shahbaz, M., & Jiao, Z. (2023). Do Muslim economies need insurance to grow? Answer from rigorous empirical evidence. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 87, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, H., Morales-Morales, M. R., Pujol-López, F. A., & Mollá-Sirvent, R. (2021). Social cryptocurrencies as model for enhancing sustainable development. Kybernetes, 50(10), 2883–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Arboleda, F. J., Rodríguez-Camacho, J. S., & Giraldo-Muñoz, D. (2021). Comparación de dos plataformas de blockchain: Bitcoin y hyperledger fabric. Ingeniería y Competitividad, 24(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosakova, E. A. (2024). Cryptocurrency market regulation: Causes, trends, and prospects. Russia and the Contemporary World, 3, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera Endara, M. R. (2022). Ecuadorian state: Legal framework for investments by cryptocurrency capital management companies (pp. 306–315). Red de Investigadores Ecuatorianos. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundan, P., James, B. V., George, F. J., Kukreja, D. K., & Goyal, Y. S. (2024). Indian budget 2022: A make-or-break moment for cryptocurrency. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Internet of Things, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshisaulu, N. N., van der Poll, H. M., & van der Poll, J. A. (2024). Enhancing and validating a framework to curb illicit financial flows (IFFs). Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). Taxing virtual currencies: An overview of tax treatments and emerging tax policy issues. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Ossadón, F. (2019). Marco fiscal de Chile. UBA Economica. Available online: https://revistadematematicas.uchile.cl/index.php/RET/article/view/55836 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Alonso-Fernández, S. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricio Lozano, D. (2022). Criptomonedas y Blockchain en el ámbito financiero: Un análisis de correlación. Revista de Métodos Cuantitativos Para La Economía y La Empresa, 34, 328–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradenas, L. (2018, October). Tributación de criptomonedas. Repositorio Universidad de Chile. Available online: https://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/168323 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Regal, A., Morzán, J., Fabbri, C., Herrera, G., Yaulli, G., Palomino, A., & Gil, C. (2019). Proyección del precio de criptomonedas basado en tweets empleando LSTM. Ingeniare. Revista Chilena de Ingeniería, 27(4), 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D. D., & Ing, S. (2023). Policy forum: Digital asset mining and GST—Tax policy versus public policy. Canadian Tax Journal, 71(1), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cairo, V. (2020). Régimen constitucional de la moneda y estabilidad del nivel general de precios en Perú. Derecho PUCP, 85, 277–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra Rodríguez, A. R. (2025). Impuesto a la renta sobre ganancias de criptomonedas: Análisis y propuesta normativa en el Perú. Revista La Junta, 7(2), 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Ocampo, L. D., & Alfaro-Salas, M. (2022). Criptomonedas y su efecto en la estabilidad del sistema financiero internacional: Apuntes para Centroamérica. Relaciones Internacionales, 95(1), 33–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]