Abstract

This study examines the impact of insurance market development on Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and economic growth in the European Union (EU-15) and Central and Eastern European (CEE-11) countries over the period 1996–2022. Long-run relationships are analysed using panel cointegration tests and Mean Group (MG), Pooled Mean Group (PMG), and Dynamic Fixed Effects (DFE) estimators. At the same time, causal links are assessed through the Granger non-causality test. Results show that in EU-15 countries, insurance development positively affects both environmental quality via reduced CO2 emissions (elasticities between 0.2078 and 0.2860), and economic growth (0.109–0.829). In CEE-11 countries, a positive effect on growth (0.102–0.205) is confirmed, but no significant environmental impact is observed. The findings highlight the need for policies that support green insurance initiatives and investments in low-carbon transition projects, especially in the CEE-11 region.

1. Introduction

The growing importance of corporate responsibility poses a sustainability challenge for insurance companies, encouraging them to reassess their product offerings and align with client expectations by introducing innovative solutions. Insurers’ efforts to assume a more active role in the evolving business landscape have led to the emergence of the concept of green insurance, which retains its core function of providing financial protection and mitigating the consequences of climate-related disasters, pollution, and natural resource degradation, while simultaneously promoting responsible and sustainable behaviour through environmental protection mechanisms. This type of insurance not only addresses environmental challenges but also actively contributes to their mitigation through specialised policies that incentivise companies and individuals to invest in sustainable business practices. Unlike traditional insurance products, green insurance policies are designed to encourage industrial and economic actors to adopt sustainable technologies. In developed insurance markets, such policies support the financial viability of projects based on renewable energy sources—such as solar panels, wind farms, and hydroelectric power plants—thus facilitating the global transition to cleaner energy and a shift toward sustainable energy infrastructure.

A clear research gap remains in understanding how the development of insurance markets impacts environmental quality, as current studies are geographically fragmented and lack theoretical consistency. Specifically, little is known about whether the mechanisms through which insurance operates differ between mature Western European markets and the less developed insurance systems in Central and Eastern Europe.

The nexus between the insurance market and CO2 emissions is a rapidly emerging area of concern and opportunity in the context of climate change and economic uncertainty. CO2 emissions have grown substantially, becoming the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gases (GHG) in recent decades. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on the implications of 1.5 °C global warming, global temperatures could rise by approximately 1.5 °C between 2030 and 2052 if current trends continue. Net GHG emissions in the European Union (EU) EU-27 fell by 31% between 1990 and 2022. Current projections suggest that by 2030, net emissions will have decreased by 49% compared to 1990 levels, falling short of the 55% reduction target set for 2030. In this context, more ambitious policies and measures are required in the ongoing revisions of national energy and climate plans to align the EU with its 2030 climate target and place it on a trajectory toward climate neutrality (European Environment Agency, 2024). Additionally, in the fourth quarter of 2024, GHG emissions in the EU economy were estimated at 897 million tons of CO2 equivalent, a 2.2% increase from the same quarter in 2023. At the same time, the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 1.5% in Q4 2024 compared to Q4 2023 (Eurostat, 2025).

In terms of total premiums, the EU market accounted for 16.7% of the global insurance market in 2023. Insurance penetration—measured as the ratio of premiums to GDP—varies significantly across the EU, with higher penetration levels generally observed in more developed and wealthier economies. While premiums exceeded 10% of GDP in countries like France and the United Kingdom, they accounted for a much smaller share of GDP in several other European countries (e.g., Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania, where the rate was below 2%). The overall insurance market penetration across EU countries stands at 6.2%, while insurance density amounts to USD 2516 per capita. These figures are below the average of developed insurance markets, where penetration reaches 9.5% and per capita premiums amount to 5339 United States dollars (USD).

A coherent theoretical mechanism connects the development of insurance markets with environmental outcomes. Insurance firms serve not only as risk-bearers but also as major institutional investors and sources of information. As risk managers, insurers incorporate climate-related hazards into premiums, limit coverage for carbon-intensive activities, and encourage firms to adopt cleaner technologies to minimise exposure. Through their large investment portfolios, insurers can strengthen these incentives by reallocating capital from high-emission industries to renewable energy, energy-efficient infrastructure, and low-carbon innovation. Effective regulatory frameworks further influence insurers’ underwriting and investment decisions, enabling the sector to serve as a conduit for integrating environmental standards into economic activity. Conversely, in less developed markets, weak regulation, limited product sophistication, and low penetration may perpetuate carbon-intensive growth, demonstrating that the environmental impact of insurance is institutionally dependent rather than automatic.

This paper examines the impact of the insurance market on economic growth and CO2 emissions in the EU-15 and Central and Eastern European (CEE) CEE-11 countries over the period 1996–2022. This study addresses two core research questions: (1) Does the insurance sector increase or reduce CO2 emissions in EU-15 and CEE-11 countries? (2) Does the development of the insurance market stimulate economic growth in the selected countries?

Given the primary objective, this paper offers a twofold contribution. To the authors’ knowledge, it is the first study to empirically analyse the impact of the insurance market on CO2 emissions specifically for European Union countries, which have a unique regulatory framework (EU Green Deal, Solvency II, ESG standards). The EU is particularly relevant given its ambitious climate goals, making this study well-positioned to provide a regional perspective that has been largely missing. Second, beyond examining the relationship between the insurance market and CO2 emissions, the paper also explores the interdependence between the insurance market and economic growth.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The literature review provides an overview of studies examining the relationship between financial system development, economic growth, and CO2 emissions. The data and methodological approach are presented in Section 3, while empirical results are reported in Section 4. Finally, conclusions and policy implications are offered in Section 5.

2. Literature Review

The academic literature remains relatively scarce on the applicability of sustainability standards to insurance companies’ day-to-day operations. Golnaraghi (2018) identified key challenges faced by insurers aiming to support the transition to a low-carbon economy, which are also relevant to ESG issues: (a) the lack of common standards and definitions, (b) regulatory capital requirements, (c) uncertainties, (d) the risk-return profile in green technology markets, and (e) the standardization of reporting and stress testing.

Gatzert et al. (2020) provided a comprehensive overview of sustainability-related risks and opportunities within the insurance industry. They addressed both assets and liabilities from a broad corporate perspective. Their study emphasised that, although climate change is an important factor in this context, it is by no means the only one. They also highlighted various key barriers, particularly the lack of knowledge, standardisation, and data, which further reduce transparency and comparability among firms, especially in light of the aforementioned reporting requirements. Stricker et al. (2022) presented a concrete managerial roadmap outlining actions across product development, marketing and sales, risk management and underwriting, and operations and claims management. They found that insurance coverage and services must include environmentally friendly elements supporting sustainable transitions, and that operational processes—especially claims management—should be evaluated against greenhouse gas emission indicators and targets established based on the overall set of activities.

Below, we provide an overview of studies examining two key relationships that constitute the focus of this research: the insurance–CO2 emissions nexus and the insurance–economic growth nexus.

2.1. Insurance vs. CO2 Emissions Nexus

High exposure to climate risks increases awareness and demand for environmental policies. Countries with a developed insurance market are more resilient to climate disasters (floods, droughts, storms). A developed insurance sector plays an institutional role in managing climate risks. Insurers collect information on risks, model climate catastrophes, and incorporate them into premiums. In this way, they can exert pressure on traditional forms of insurance, such as higher premiums for “dirty” activities, limiting coverage for CO2-intensive industries, and encouraging firms to adopt environmental standards. Insurance companies possess significant financial capacity through their investment portfolios. Regulatory frameworks can direct them toward green investments, including withdrawing capital from polluting sectors (coal divestment), investing in renewable energy sources and green infrastructure, and ensuring transparency and reporting on climate risks.

From an economic perspective, the development of the insurance market can have either a positive or negative impact on CO2 emissions. The insurance sector, as part of the financial system, can accelerate industrial growth by financing heavy industries (fossil fuels), thereby increasing CO2 emissions (scale effect). On the other hand, the insurance sector can finance clean technologies, thereby reducing CO2 emissions (innovation effect). Hien et al. (2024) showed that gross insurance premiums act as a mediator between GDP and various environmental indicators, including carbon dioxide emissions, greenhouse gas emissions, material resource use, and renewable energy. These results highlight the crucial role of insurance premium policies, environmental taxation, bank lending practices, and corporate debt management as key instruments for reducing the environmental impacts associated with sustainable development.

The expansion and implementation of green insurance still face several fundamental challenges. Mills (2009) conducted one of the earliest studies in this field, examining how the insurance industry has responded to climate change. Using questionnaires directed at insurance companies, the findings showed that despite the sector’s significant contribution to combating climate change, there were limitations at the time regarding the risks insurers could cover. More recently, Desalegn (2023) notes that insurance companies are responding to the global challenge of climate change by introducing green insurance policies to promote sustainable projects. These policies provide financial protection and coverage for initiatives related to renewable energy, energy efficiency, and other sustainable ventures, while encouraging investments through lower premiums or other monetary incentives. The study analyses various forms, instruments, and measures of green insurance and concludes that its success faces numerous obstacles, including inadequate infrastructure, limited awareness and education among individuals and businesses, the absence of supportive regulatory frameworks and policies, insufficient demand, political instability, corruption, and security risks. It recommends that insurance companies offer incentives to investors engaged in sustainable projects, such as premium adjustment strategies. Similar views are shared by other authors who emphasise that green insurance is designed to address environmental risks and promote sustainability (Vyas et al., 2021), and that the insurance industry has a unique opportunity to contribute to these goals by providing coverage for environmentally friendly projects, promoting sustainable business practices, and encouraging investments in green technologies (Stepanova, 2021). Eling (2024) demonstrates that the insurance industry operates as a sustainable sector by integrating and supporting sustainability objectives across environmental, social, economic, and technological areas.

International organisations such as the United Nations and the World Bank play a key role in these processes by defining global standards for sustainable business and financing. The 2015 Paris Climate Agreement represents a fundamental framework for the global fight against climate change and the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, which, in turn, indirectly affects the insurance sector (Krogstrup & Oman, 2019). The development of a regulatory framework for green insurance and sustainable finance highlights the importance of climate risks and the need for greater transparency in the financial sector. Key elements of this framework include initiatives such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Principles for Sustainable Insurance (PSI). Established in 2015 by the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the TCFD aims to improve transparency regarding climate risks and opportunities in the financial sector. Its recommendations include climate risk governance, advising companies to report on the oversight and management of climate risks, including their integration into overall governance and business strategy.

In the realm of empirical analyses, we highlight recent studies. Leo et al. (2024) examined the relationship between global GHG emissions and insurance premium pricing, with a special focus on implications for climate risk mitigation in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. This study emphasises the importance of incorporating environmental issues into risk assessment and insurance pricing models to adequately account for climate-related risks. Rizwanullah et al. (2022) empirically analysed the dynamic impact of insurance market development on CO2 emissions in emerging markets over the period 1991–2018. The authors found that growth in life insurance significantly reduces CO2 emissions, while the impact of non-life insurance on emissions varies across countries. Samour et al. (2024) found that the development of the insurance market positively influences a country’s environmental quality. As a result, policymakers in the UAE are encouraged to design policies and strategies that strengthen the sustainability of insurance markets, reduce environmental pollution, and reward those who generate low carbon emissions or use environmentally friendly materials. These goals can be supported by promoting green investments and developing eco-focused insurance products, thereby enhancing environmental quality while improving insurers’ profitability and creditworthiness. Conversely, Appiah-Otoo and Acheampong (2021) found that insurance market development (measured via life, non-life, and composite insurance indices) significantly contributes to increased CO2 emissions in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates) countries. Altarhouni et al. (2021) observed in Turkey that the development of the insurance market drives CO2 emissions.

Looking more broadly at the financial system, studies have investigated the relationship between financial development and CO2 emissions. Dong et al. (2024), applying entropy methods and panel VAR analysis to China (the world’s largest CO2 emitter), found that financial system development contributes to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Similarly, Al-Zubairi et al. (2025) concluded that financial development reduces CO2 emissions. Apeaning and Labaran (2025) showed that in BRICS countries, strong financial development enhances the impact of climate innovations on emissions reductions. Abbas et al. (2025), using panel analysis for the Next Eleven (NEXT-11) countries, also confirmed that financial system development reduces CO2 emissions. Conversely, Xu et al. (2022), analysing 34 European economies, found that financial system development (measured by domestic credit to the private sector) increases CO2 emissions. Petrović and Lobanov (2022) used econometric techniques to demonstrate a positive, long-term impact of financial system development on CO2 emissions during 1970–2014, using a sample of 24 selected countries. Habiba and Xinbang (2022), examining developed and emerging markets, showed that financial system development reduces emissions. Jiang and Ma (2019) examined the relationship between financial development and carbon emissions using the system generalised method of moments and data from 155 countries, finding that globally, financial development can significantly increase carbon emissions, especially in emerging and developing countries.

2.2. Insurance-Economic Growth Nexus

Researchers have examined the causal relationship between insurance market development and economic growth at various levels and from different perspectives—ranging from the global level to individual countries, and from the entire insurance market to specific types of insurance. Below is an overview of recent studies that have empirically analysed this issue using panel econometric methods.

Before presenting the findings, it is important to note that Singh et al. (2025) emphasised the need for more comprehensive and systematic research on the insurance–economic growth nexus. They conducted a literature review of existing studies that addressed this topic. Scharner et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between economic growth and insurance expenditure using a panel of 130 countries over the period 2003–2016. The authors found that the share of household income allocated to life insurance increases as economies become wealthier. Their findings support the demand-following and feedback hypotheses, suggesting that economic growth contributes to the development of the insurance sector. Additionally, the effects were found to be stronger in middle-income economies compared to high-income ones.

Zouhaier (2014) conducted a study on 23 OECD countries using a fixed-effects panel model for the period 1990–2011. He examined the insurance industry as a whole, as well as the life and non-life sectors separately. He found an adverse effect of aggregate and non-life insurance on economic growth when measured by insurance density. Conversely, non-life insurance had a significant positive impact on economic growth when measured by penetration rate. Peleckienė et al. (2019) explored the relationship between insurance and economic development in EU-27 countries over the period 2004–2015. They identified a statistically significant positive relationship between insurance penetration and economic growth in Luxembourg, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland. Additionally, a significant negative relationship was found in Austria, Belgium, Malta, Estonia, and Slovakia. The primary econometric method used was the Granger causality test, which indicated unidirectional causality from GDP to insurance in Luxembourg and Finland, and from insurance to GDP in the Netherlands, Malta, and Estonia. In Austria, bidirectional causality was confirmed, whereas in Slovakia, no causality was found between the variables.

Bayar et al. (2021) analysed the impact of insurance sector development on economic growth in a sample of 14 Central and Eastern European (CEE) transition economies over the period 1998–2016. The authors concluded the following: (1) life insurance does not have a significant impact on economic growth, neither in the panel analysis nor at the individual country level, and (2) non-life insurance positively affects economic growth both in the panel and country-specific analyses. Lojanica et al. (2022) examined the interdependence between insurance market parameters and economic growth in the former Yugoslav countries. They demonstrated that the insurance sector and economic growth are linked in the long run, and that insurance has a positive, statistically significant effect on economic growth. Similar conclusions were drawn by Tran and Huynh (2023) and Tasdemir and Alsu (2024). Mitrašević et al. (2022) investigated the relationship between insurance market development and economic growth in EU member states over the period 1998–2018. The results show a statistically significant, long-term positive relationship between per capita insurance premiums and per capita GDP growth in the panel analysis across all observed countries, as well as among emerging-market countries. On the other hand, panel data analysis for developed market countries also revealed a long-term positive relationship, but it was not statistically significant.

A fascinating finding comes from Dawd and Benlagha (2023), who applied linear dynamic panel data models to examine the relationship between insurance (life, non-life, and total insurance) and economic growth across 16 OECD countries for the period 2009–2020. Their analysis revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between insurance premiums and economic development, supporting the hypothesis of a nonlinear connection between insurance and economic performance.

3. Data and Methodology

To examine the impact of the insurance market on the environment and economic growth in the EU-15 countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) and the CEE-11 countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and the Slovak Republic), we utilized panel data covering the period from 1996 to 2022. CO2 emissions and GDP are the dependent variables in the models. CO2 is measured as CO2 emissions excluding Land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) per capita (tCO2e/capita), and GDP is measured as GDP per capita (constant 2015 USD). DENS_T refers to insurance density, measured per capita in US dollars. It represents the total density, calculated as the sum of life and non-life insurance.

A set of control variables, including ENERGY (energy consumption) and TO (trade openness), is included to mitigate omitted variable bias. All variables are log-transformed (L) before estimation. Table 1 provides further explanations regarding the variables used, their abbreviations, data sources, and methodological clarifications. For methodological clarity, the assumptions underlying each estimator were explained to justify the use of second-generation panel tests and to ensure the empirical approach follows best practices in panel econometrics.

Table 1.

Abbreviations, Variable descriptions, and Sources.

The study tests two models. The first model examines the effect of the insurance market on CO2 emissions, including energy consumption as a control variable. The second model tests the impact of the insurance market on economic growth, with trade openness serving as the control variable. The dependence of the investigated variables can be presented in the following general form:

The functional relationship between the variables can be expressed as follows:

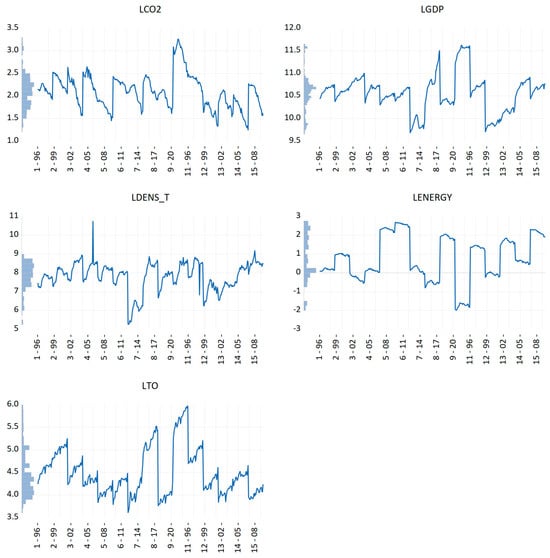

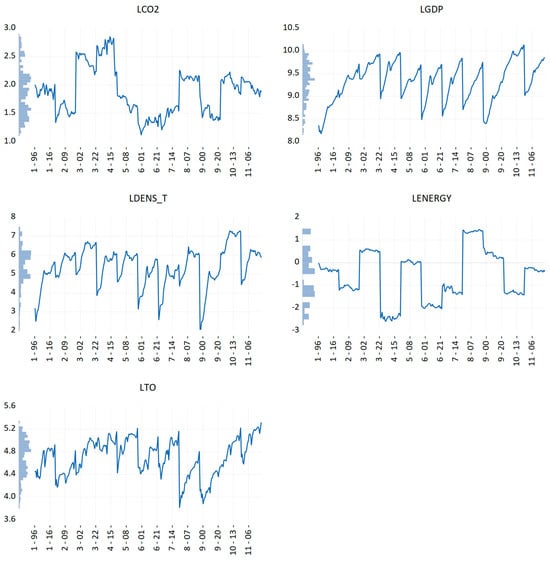

where i denotes the cross-sectional units (countries), t represents the time dimension, LCO2 refers to carbon dioxide emissions, LDENS_T to insurance density, LENERGY to energy consumption, and LGDP to gross domestic product per capita. The coefficients β1, β2, γ1, and γ2 correspond to the independent variables; LTO represents trade openness; and ε and μ are the error terms. In the Appendix A, the time-series dynamics of each variable are displayed for each cross-sectional unit, with the corresponding histogram shown on the vertical axis. We test for potential multicollinearity to assess whether the explanatory variables in the models are independent. They indicate that the tolerance values are well above the benchmark value of 0.2, and the VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values are below 5, suggesting the absence of multicollinearity among the regressors. This implies that the selected factors can be considered valid explanatory variables for the dependent variables LCO2 and LGDP.

Prior to examining potential cointegration relationships among the key variables, unit root tests are conducted. Traditional panel unit root tests, which assume either homogeneity or heterogeneity across cross-sectional units, can be affected by size bias and specific dataset characteristics. In the presence of cross-sectional dependence, second-generation unit root tests—such as the CIPS test proposed by H. M. Pesaran (2007)—are more appropriate and thus employed. The CIPS is represented as follows:

Westerlund’s (2007) test can produce consistent and robust results under the condition of cross-sectional dependence. Westerlund (2007) uses a combination of heterogeneous cross-sectional dependencies in the presence of nonstationary and heterogeneous issues in the data. For instance, unlike first-generation tests, Westerlund’s approach considers both cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneous trajectories. The equation can be presented in the following form:

where t = 1, …, T and i = 1, …, N denote the time series and cross-sectional units, respectively; dt contains the deterministic components, and pi and qi are used for lags and leads.

This study employs three estimators simultaneously—the pooled mean group (PMG) estimator, the mean group (MG) estimator, and the dynamic fixed effects estimator. The rationale behind using this set of estimators is as follows: the PMG estimator allows short-run coefficients, error variances, and slope coefficients to vary across countries, while constraining long-run coefficients to remain homogeneous. This makes PMG suitable in contexts where the data exhibit slope heterogeneity. By contrast, the MG estimator imposes no parameter restrictions and fully accounts for cross-country heterogeneity. The DFE estimator assumes that slope coefficients and error variances are common across countries, while intercepts are free to differ, thus providing an alternative benchmark specification. To further strengthen the robustness of the panel cointegration analysis, this study additionally applies a Juodis et al. (2021) non-causality test.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Variance

The test for cross-sectional dependence (CSD) is used to determine the appropriate analytical techniques for empirical research (Table 2). Based on the outcomes of the CSD test, researchers decide whether to apply first or second-generation panel data tests. Failure to conduct this diagnostic may lead to biased and unreliable results. The primary sources of cross-sectional dependence include standard shocks and unobserved components (Hao et al., 2021). Globalisation and international economic integration are among the main drivers of increasing interdependence among countries. In order to ensure the accuracy and consistency of empirical findings, it is essential to formally test for cross-sectional dependence. When the time dimension (T) exceeds the cross-sectional dimension (N), the Breusch-Pagan LM test is recommended.

Table 2.

Results of the Variance Inflation Factor.

Variation in slope parameters can lead to biased panel regression results. Slope heterogeneity refers to unit-specific differences across cross-sectional units (Zeraibi et al., 2021). Given the inherent differences among the countries under study, it is important to determine whether the corresponding slope coefficients exhibit heterogeneity. In line with H. M. Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) and Blomquist and Westerlund (2013), a slope heterogeneity test was employed. The subsequent step involved examining the stationarity properties of the panel series—specifically, testing whether the series are stationary at the level or after differencing. This study applied the second-generation panel stationarity test, CIPS (H. M. Pesaran, 2007). Furthermore, cointegration among the observed variables was tested using the Westerlund (2007) test. The Westerlund test provides reliable and robust results, particularly in the presence of cross-sectional dependence.

The following three cointegration techniques were employed in the subsequent analysis: Pooled Mean Group (PMG) (M. H. Pesaran et al., 1999), Mean Group (MG) (M. H. Pesaran & Smith, 1995), and Dynamic Fixed Effects (DFE) (Weinhold, 1999). The MG estimator reflects the standard practice in panel data analysis of estimating N separate regressions and averaging the coefficients, a method referred to as MG estimation. In addition, the PMG estimator assumes that long-run coefficients are homogeneous across groups, while allowing short-run coefficients and error variances to differ.

The DFE model assumes that the intercepts and coefficients on lagged endogenous variables are specific to each cross-sectional unit. In contrast, the coefficients on exogenous variables are normally distributed across units. This model possesses several desirable properties. Specifically, it allows for substantial heterogeneity across cross-sectional units, both in dynamics and in the relationships between independent and dependent variables. Moreover, the DFE model does not produce biased estimates when the panel’s time dimension is relatively short.

It is important not to rely on a single class of panel estimators, as doing so may lead to inconsistent results. Therefore, to enhance the robustness of the panel cointegration analysis, this study also employs the Granger non-causality test. Unlike the Dumitrescu-Hurlin test, the method proposed by Juodis et al. (2021) is valid in models with either homogeneous or heterogeneous coefficients. The novelty of the proposed approach lies in the fact that, under the null hypothesis, the Granger causality coefficients are all zero and thus assumed to be homogeneous. Consequently, the authors propose using a pooled least-squares (fixed-effects) estimator for these coefficients. This represents a more realistic assumption in many empirical applications.

4.2. Panel Research Results

The results of the cross-sectional dependence test are presented in Table 3. The null hypothesis of no cross-sectional dependence among units is rejected by formal testing for both the EU-15 and CEE-11 groups. This indicates that there is no mutual independence among the cross-sectional units of the selected indicators in the countries under analysis.

Table 3.

The results of Breusch- Pagan LM cross-sectional dependence test.

Determining the integration properties of the variables involves testing for panel stationarity. Conventional unit root tests (first-generation tests) may yield biased results when cross-sectional dependence is present among panel units. Given the findings presented in Table 3, this study employs the second-generation panel unit root test developed by H. M. Pesaran (2007). The null hypothesis assumes that the panel series contains a unit root, i.e., that the variables are non-stationary. The results indicate that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected when applied to the original data, suggesting that the variables become stationary only after being transformed into first differences. Thus, it can be concluded that the variables are integrated of order one, I(1) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Findings from the CIPS Panel Unit Root Test.

Table 5 presents the results of the slope homogeneity tests proposed by H. M. Pesaran and Yamagata (2008) and Blomquist and Westerlund (2013). The results confirm the presence of variation in slope parameters. The null hypothesis of slope homogeneity is rejected across all estimated models.

Table 5.

Slope Coefficient Heterogeneity Testing.

Furthermore, to examine whether the variables in the empirical analysis are cointegrated, the Westerlund cointegration test was employed. Table 6 presents the results of the Westerlund (2007) test, providing evidence of cointegration among the variables. The results presented in Table 7 demonstrate the impact of insurance market development on CO2 emissions in the EU-15 and CEE-11 countries.

Table 6.

Testing for Cointegration with the Westerlund approach.

Table 7.

Long-Run Relationship Analysis—Dependent Variable: LCO2.

Specifically, the findings indicate that in the EU-15, the development of the insurance market—measured by the percentage growth in insurance density—coincides with a reduction in CO2 emissions ranging from 0.2078 to 0.2860 percentage points. More precisely, CO2 emissions decrease by 0.2078 to 0.2860 units (depending on the estimation technique applied) for each unit increase in insurance density. This suggests that the development of the insurance market contributes to enhanced environmental sustainability. The insurance sector in the EU-15 appears aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals, thereby exerting a positive, statistically significant effect on environmental outcomes.

In contrast, such findings are not confirmed for the CEE-11 group. In two out of the three estimation techniques applied (MG and DFE), the development of the insurance market does not have a statistically significant impact on CO2 emissions. Furthermore, results from the PMG estimator indicate that insurance market development actually increases CO2 emissions. Specifically, a percentage increase in insurance density is associated with a 0.115-point increase in CO2 emissions. This outcome may be attributed to the fact that insurance market development policies in CEE-11 countries are not environmentally sustainable, as reflected by either the absence of a correlation or a positive one between insurance market development and environmental degradation. Additionally, across both groups of countries, an increase in energy consumption is associated with a rise in CO2 emissions—a result that aligns with expectations.

The estimated elasticities offer insight into the channels through which insurance development influences emissions. In the EU-15, negative elasticities indicate that insurers allocate capital to cleaner technologies and adopt ESG-aligned underwriting practices that discourage high-emission activities. In the CEE-11, weak or positive elasticities reflect less developed markets where limited product variety and weaker regulatory incentives reduce the sector’s capacity to shift behaviour towards low-carbon outcomes.

The differences in outcomes between the EU-15 and the CEE-11 are due to underlying institutional structures. EU-15 insurers benefit from robust regulations, greater ESG integration, and more mature markets, which allow them to promote green investments and price climate risks effectively. Conversely, in CEE-11 nations, weaker oversight, lower market penetration, and slower uptake of sustainability standards restrict insurance markets’ ability to impact environmental outcomes.

Several factors can explain this result for the EU15. EU15 countries have developed liquid insurance markets and sophisticated products (e.g., green insurance policies and investments in renewable energy), reflecting the sector’s maturity. EU directives encourage insurers to invest in environmentally friendly projects and limit financing of polluting industries. Insurers finance low-emission technologies, promote energy-efficient projects, and support green infrastructure, which directly reduces CO2 emissions.

In the CEE11 countries, no significant impact of the insurance market on CO2 emissions was observed. This can be explained by several factors: low insurance penetration and limited market liquidity make it difficult to finance green projects, indicating a less developed insurance market. The lack of adequate policies, weaker supervision, and insufficient implementation of ESG standards, combined with insurance financing of traditional sectors (heavy industry, fossil fuels), neutralises the potential positive effect on emission reduction. Additionally, lower environmental awareness among companies and insurers leads to weaker demand for green products.

The results presented in Table 8 provide an overview of the effects of insurance market development on economic growth in the EU-15 and CEE-11 countries. In the EU-15, insurance market development—measured by the percentage increase in insurance density—leads to higher economic activity, with estimated effects ranging from 0.109 to 0.829 across estimation techniques.

Table 8.

Long-Run Relationship Analysis—Dependent Variable: LGDP.

A similar effect is observed in the CEE-11 group, where the percentage increase in insurance density is associated with economic growth ranging from 0.102 to 0.262. Although the EU-15 and CEE-11 countries differ in their economic structure, the effect of insurance market development on economic growth is the same in both regional blocs. Growth in premium levels and the improvement in the creditworthiness of businesses and households contribute to the overall increase in investments and economic activity in both the EU-15 and CEE-11. The control variable, LTO, has a positive, statistically significant effect on economic growth in both the EU-15 and CEE-11 countries. To ensure the robustness of the results, panel causality was examined. The findings are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Panel Granger Non-Causality Test (Juodis et al., 2021).

For the EU-15 countries, it was established that insurance density Granger-causes changes in CO2 emissions and economic growth. The direction of causality is consistent with the results obtained from the previously applied estimation techniques. Similarly, for the CEE-11 countries, the panel causality analysis reveals effects that align with those identified by the earlier methods.

5. Conclusions

The 2015 Paris Agreement set a goal of limiting the average global temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, with each country contributing through nationally determined contributions to achieve this target. The European Green Deal aims to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. Climate policy plays a crucial role in achieving this goal. Therefore, finding alternative solutions to reduce CO2 emissions is of great importance for economic policymakers. Motivated by these objectives and the identified gaps in the literature, we examined the impact of insurance market development on CO2 emissions for EU-15 and CEE-11 countries using panel econometrics over the period 1996–2022. In addition, given the recent slowdown in economic growth across the European Union, we investigated whether the development of the insurance market can stimulate economic activity in these two regional blocs.

We found that the development of the insurance sector reduces CO2 emissions in the EU-15, while it has no statistically significant impact in the CEE-11 countries. Additionally, the insurance sector promotes economic growth in both regional blocs. Specifically, a 1% increase in insurance development reduces CO2 emissions in the EU-15 by between 0.2078% and 0.2860%, while the same increase has no effect on CO2 emissions in the CEE-11. A 1% increase in insurance development boosts economic growth in the EU-15 and CEE-11 countries by between 0.109–0.829% and 0.102–0.205%, respectively. These findings have important practical implications for insurers and economic policymakers in both the EU-15 and CEE-11.

The findings of this study may serve as a foundation and provide valuable recommendations for the further development of the insurance sector. Although banking services dominate the financial sectors of the analysed economies, there remains considerable potential for enhancing the insurance market. In light of the significant positive effects that insurance development has on economic growth, economic policymakers should prioritise the formulation of appropriate regulatory and legal frameworks that facilitate the sustainable development of the insurance sector. This would enable the sector’s core functions to operate at a higher level of effectiveness and contribute more substantially to broader economic goals. Particularly notable is the room for improvement in the life insurance segment across CEE-11 and EU-15 countries. Progress in this area could be achieved by highlighting the role of insurance in reducing future uncertainty, by promoting efficient pricing of insurance services, and by fostering greater trust in the insurance sector. Moreover, to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), policymakers must integrate the insurance sector into broader sustainable development strategies.

The increasing frequency of environmental incidents and disasters—such as chemical spills and pollution—has motivated insurers to offer coverage that includes the costs of environmental remediation and the legal consequences arising from such events. These developments underscore the importance of the insurance industry’s active involvement in promoting sustainable behaviour throughout the broader social and economic landscape—not only by responding to existing risks, but also by encouraging environmentally responsible practices. Green insurance policies are becoming increasingly standard in industries particularly vulnerable to environmental risks, such as energy, chemical manufacturing, and agriculture.

Furthermore, the development of a robust regulatory framework for green insurance and sustainable finance is essential. Such a framework should recognise the significance of climate-related risks and promote transparency and accountability in the financial sector. In light of our empirical findings, which indicate that the development of the insurance market stimulates economic activity, insurers in EU-15 and CEE-11 countries should intensify their engagement in climate change mitigation, particularly by supporting carbon-reduction efforts. This may include facilitating financing for green projects, such as renewable energy sources, energy efficiency improvements, and circular economy initiatives. Policymakers, in turn, should encourage reforms in the insurance sector that align with carbon mitigation goals. In doing so, two major objectives can be achieved simultaneously: stimulating economic growth and generating positive environmental outcomes.

EU15 countries should continue supporting green financial products and insurance, strengthen transparency and reporting on climate risks, and promote the integration of ESG criteria into insurance portfolios. CEE11 countries need to reinforce their regulatory frameworks so that the insurance market can effectively contribute to emission reductions, introduce tax incentives, subsidies, and support for green insurance products, and provide education for insurers and businesses on climate risks and green investments. Additionally, it is crucial to promote partnerships between EU15 and CEE11 countries to facilitate knowledge and technology transfer within the EU.

In the EU15, the insurance sector operates within a well-established regulatory framework that encourages sustainable finance and integrates ESG considerations into investment and underwriting decisions. High market maturity, sophisticated financial instruments, and strong enforcement of EU directives enable insurers to finance low-carbon projects, promote green technologies, and support energy-efficient initiatives. As a result, the “innovation effect” dominates, leading to measurable reductions in CO2 emissions.

In contrast, CEE11 countries face a less developed institutional environment. Insurance markets are characterised by lower penetration, limited product diversity, and weaker regulatory oversight. ESG integration is still in its early stages, and policies incentivising green investments are often insufficient. Consequently, the insurance sector in these countries tends to support traditional, carbon-intensive industries, thereby essentially muting the potential positive impact on emissions.

Regarding the limitations, we highlight the following: First, future research could benefit from a broader sample of countries, extending beyond the European context, to allow for more generalizable findings; Second, the application of additional econometric techniques would enhance the robustness and validity of the results; Third, future studies should consider incorporating more detailed indicators of insurance market development—such as insurance penetration rates and disaggregated data for life and non-life insurance—as well as alternative measures of environmental degradation, such as the ecological footprint. These enhancements would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between insurance market development, economic activity, and ecological sustainability.

Overall, the empirical evidence suggests that the development of insurance markets has varied long-term impacts across EU regions. In the EU-15 countries, expanding insurance services improves both environmental quality and economic growth, indicating that established markets can direct insurance funds toward sustainable projects. Conversely, the absence of ecological benefits in the CEE-11 countries highlights how institutional and regulatory shortcomings restrict the insurance sector’s ability to aid decarbonisation efforts. Therefore, enhancing green insurance frameworks could help achieve more uniform sustainability results throughout Europe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and V.S.; methodology, V.S.; software, N.L.; validation, N.L., V.S. and S.G.; formal analysis, N.L.; investigation, V.S.; resources, V.S.; data curation, N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L., V.S. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, N.L., V.S. and S.G.; visualization, S.G.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, N.L.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Graphs and Histograms of Each Variable by Cross-Sectional Units in EU-15.

Figure A2.

Graphs and Histograms of Each Variable by Cross-Sectional Units in CEE-11.

References

- Abbas, K., Amin, N., Khan, F., Begum, H., & Song, H. (2025). Driving sustainability: The nexus of financial development, economic globalization, and renewable energy in fostering a greener future. Energy & Environment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarhouni, A., Danju, D., & Samour, A. (2021). Insurance market development, energy consumption, and Turkey’s CO2 emissions: New perspectives from a bootstrap ARDL test. Energies, 14(23), 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zubairi, A., Al-Akheli, A., & Elfarra, B. (2025). The impact of financial development, renewable energy and political stability on carbon emissions: Sustainable development perspective for Arab economies. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27, 15251–15273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeaning, R. W., & Labaran, M. (2025). Does financial development moderate the impact of climate mitigation innovation on CO2 emissions? Evidence from emerging economies. Innovation and Green Development, 4(2), 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Otoo, I., & Acheampong, A. O. (2021). Does insurance sector development improve environmental quality? Evidence from BRICS. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28, 29432–29444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y., Dan Gavriletea, M., & Danuletiu, D. C. (2021). Does the insurance sector really matter for economic growth? Evidence from Central and Eastern European countries. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 22(3), 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, J., & Westerlund, J. (2013). Testing slope homogeneity in large panels with serial correlation. Economics Letters, 121(3), 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawd, I., & Benlagha, N. (2023). Insurance and economic growth nexus: New evidence from OECD countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2183660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, G. (2023). Insuring a greener future: How green insurance drives investment in sustainable projects in developing countries. Green Finance, 5(2), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K., Wang, S., Hu, H., Guan, N., Shi, X., & Song, Y. (2024). Financial development, carbon dioxide emissions, and sustainable development. Sustainable Development, 32(1), 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, M. (2024). Is the insurance industry sustainable? The Journal of Risk Finance, 25(4), 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2025). International energy data and statistics. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- European Environment Agency. (2024). Total net greenhouse gas emission trends and projections in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/total-greenhouse-gas-emission-trends (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Eurostat. (2025). EU economy greenhouse gas emissions up 2.2% in Q4 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250515-1 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Gatzert, N., Reichel, P., & Zitzmann, A. (2020). Sustainability risks & opportunities in the insurance industry. Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Versicherungswissenschaft, 109(5), 311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Golnaraghi, M. (2018). Climate change and the insurance industry: Taking action as risk managers and investors. The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Habiba, U., & Xinbang, C. (2022). The impact of financial development on CO2 emissions: New evidence from developed and emerging countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 31453–31466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, L.-N., Umar, M., Khan, Z., & Ali, W. (2021). Green growth and low carbon emission in G7 countries: How critical the network of environmental taxes, renewable energy and human capital is? Science of the Total Environment, 752, 141853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hien, T. T. L., Tri, H. T., & Tuong Van, P. T. (2024). Role of insurance in promoting sustainable development in OECD countries: Mediation analyses. WSB Journal of Business and Finance, 58(1), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C., & Ma, X. (2019). The impact of financial development on carbon emissions: A global perspective. Sustainability, 11(19), 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juodis, A., Karavias, Y., & Sarafidis, V. (2021). A homogeneous approach to testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Empirical Economics, 60, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstrup, S., & Oman, W. (2019). Macroeconomic and financial policies for climate change mitigation: A review of the literature (IMF Working Paper, WP/19/185). International Monetary Fund.

- Leo, J., Bernick, R., Velankanni, A., & Nandakumar, D. C. (2024). Climate risk management in insurance: Exploring the relationship between global greenhouse gas emissions and premium pricing. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(22s), 441–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lojanica, N., Stančić, V., & Luković, S. (2022). Insurance market development and economic growth: Evidence from Western Balkans region. Teme, 46(2), 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E. (2009). A global review of insurance industry responses to climate change. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice, 34(3), 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrašević, M., Pjanić, M., & Novović Burić, M. (2022). Relationship between insurance market and economic growth in the European Union. Politická Ekonomie, 70(4), 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleckienė, V., Peleckis, K., Dudzevičiūtė, G., & Peleckis, K. (2019). The relationship between insurance and economic growth: Evidence from the European Union countries. Economic Research—Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H. M. (2007). A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22(2), 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H. M., & Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. Journal of Econometrics, 142(1), 50–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1999). Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(446), 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. P. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, P., & Lobanov, M. M. (2022). Impact of financial development on CO2 emissions: Improved empirical results. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24, 6655–6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwanullah, M., Narsullah, M., & Liang, L. (2022). On the asymmetric effects of insurance sector development on environmental quality: Challenges and policy options for BRICS economies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 10802–10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samour, A., Onwe, J. C., Inuwa, N., & Imran, M. (2024). Insurance market development, renewable energy, and environmental quality in the UAE: Novel findings from a bootstrap ARDL test. Energy & Environment, 35(2), 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharner, P., Sonnenberger, D., & Weiß, G. (2023). Revisiting the insurance–growth nexus. Economic Analysis and Policy, 79, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D., Srivastava, A. K., Malik, G., Yadav, A., & Jain, P. (2025). Insurance and economic growth nexus: A comprehensive exploration of the dynamic relationship and future research trajectories. Journal of Economic Surveys, 39(3), 841–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, M. N. (2021). The place and role of insurance in shaping a “green” economy. Vestnik Universiteta, 10, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stricker, L., Pugnetti, C., Wagner, J., & Zeier Röschmann, A. (2022). Green insurance: A roadmap for executive management. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(5), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Re Institute. (2025, July 9). Sigma 2/2025: World insurance in 2025—A riskier, more fragmented world order. Available online: https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2025-02-world-insurance-riskier-fragmented-world.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Tasdemir, A., & Alsu, E. (2024). The relationship between activities of the insurance industry and economic growth: The case of G-20 economies. Sustainability, 16(17), 7634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q. T., & Huynh, N. (2023). Can insurance ensure economic growth in an emerging economy? Fresh evidence from a non-linear ARDL approach. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 15(6), 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S., Dalhaus, T., Kropff, M., Aggarwal, P., & Meuwissen, M. P. (2021). Mapping global research on agricultural insurance. Environmental Research Letters, 16(10), 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, D. (1999). A dynamic “fixed effects” model for heterogeneous panel data. CORE Connecting Repositories. [Google Scholar]

- Westerlund, J. (2007). Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(6), 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (n.d.). World development indicators. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Xu, B., Li, S., Afzal, A., Mirza, N., & Zhang, M. (2022). The impact of financial development on environmental sustainability: A European perspective. Resources Policy, 78, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraibi, A., Balsalobre-Lorente, D., & Murshed, M. (2021). The influences of renewable electricity generation, technological innovation, financial development, and economic growth on ecological footprints in ASEAN-5 countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28, 51003–51021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouhaier, H. (2014). Insurance and economic growth. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(12), 102–113. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).