Abstract

This study investigates the determinants of Fraudulent Financial Reporting (FFR) in the banking sector from 2021 to 2024 by integrating the Fraud Hexagon framework within a risk and financial management perspective. Using panel data comprising 140 bank-year observations (35 banks over four years), the research applies an empirical analysis to examine six key elements—pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion—that shape fraud risk behavior in financial institutions. The results indicate that leverage does not significantly influence fraud incentives, suggesting that financial pressure alone is insufficient to drive fraudulent reporting without weak governance structures. In contrast, factors related to ineffective monitoring, auditor switching, and director change show varying effects on FFR. The findings also reveal that CEO image does not reflect arrogance, which has no significant effect on FFR, and political connections of entities do not automatically reduce fraud risk unless supported by strong and independent governance mechanisms. The study underscores the crucial moderating role of the audit committee in enhancing financial reporting integrity. From a policy perspective, the research provides strategic insights for regulators and supervisory bodies such as the Financial Services Authority (OJK) to strengthen governance frameworks, enforce stricter disclosure requirements, and integrate fraud risk management practices into corporate oversight. Overall, this study contributes to the financial governance literature by demonstrating how effective risk management and governance alignment can reduce fraudulent reporting and improve the sustainability of the banking sector.

1. Introduction

Fraudulent financial reporting (FFR) remains a critical concern in global financial markets due to its detrimental effects on corporate sustainability, investor confidence, and economic stability (Zin et al., 2020). The mandatory disclosure of financial statements across reporting periods often creates incentives for management to manipulate earnings, either to maintain market reputation or to achieve performance targets. Consequently, reported financial statements may not accurately represent the firm’s true financial condition (Achmad et al., 2022b; Biduri & Tjahjadi, 2024). Notorious global cases illustrate the devastating consequences of FFR. The Wirecard scandal in Germany involved the fabrication of €1.9 billion in assets, escaping auditor detection and resulting in systemic trust erosion (Hill & Kirby, 2022). Similarly, the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse in the United States was characterized by the concealment of substantial losses in its bond portfolio, undermining transparency and regulatory oversight. These cases demonstrate how FFR not only damages a firm’s reputation but also destabilizes the broader financial ecosystem.

In Indonesia, the phenomenon of fraudulent reporting has become increasingly concerning. According to the Report to the Nations by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE, 2020), the average loss from financial statement fraud reached USD 954,000 per case, underscoring the substantial financial and reputational implications of such misconduct. High-profile domestic cases such as the Maybank Cipulir Branch fraud in 2020 (losses amounting to Rp 22.8 billion) and irregularities in Regional Development Banks (BPD) identified by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK, 2025) (Rp 1.26 trillion) further demonstrate the vulnerability of Indonesian financial institutions to manipulation and weak governance (KPK, 2025). Strengthening governance and oversight mechanisms thus becomes essential to maintain financial integrity and prevent systemic contagion.

The Fraud Hexagon Theory offers a more comprehensive behavioral and structural framework for explaining fraudulent financial reporting (FFR), expanding on the traditional Fraud Triangle and Fraud Diamond by integrating six dimensions: pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion. However, empirical evidence on these determinants remains inconsistent. Several studies support the positive influence of these six elements on fraudulent behavior (Alfarago & Mabrur, 2022; Indrijawati et al., 2025; Junus et al., 2025; Naldo & Widuri, 2023; Sari et al., 2022; Setiawan & Soewarno, 2025a; Sudrajat et al., 2023; Yaumil & Thaifur, 2025), while others report insignificant or even negative associations (Achmad et al., 2024; Bader et al., 2024; Lastanti et al., 2022; Oktaviany & Reskino, 2023; Sari et al., 2024; Sudrajat et al., 2023).

Notably, the inclusion of collusion as a new dimension in the Fraud Hexagon Theory also yields divergent findings. Some studies find that collusion positively drives fraudulent acts (Alfarago & Mabrur, 2022; Bader et al., 2024; Handoko & Salim, 2022; Indrijawati et al., 2025; Oktaviany & Reskino, 2023), while others reveal that collusion may actually reduce the likelihood of fraud (Achmad et al., 2022b; Sari et al., 2024; Setiawan & Soewarno, 2025b; Sudrajat et al., 2023).

These inconsistent findings indicate that the Fraud Hexagon Theory, despite its conceptual comprehensiveness, may not fully capture the dynamic and contextual nature of fraudulent behavior, particularly in environments characterized by different levels of governance quality and audit effectiveness. This limitation highlights a key research gap, namely the absence of an integrative framework that connects behavioral fraud drivers with governance and risk management mechanisms. Addressing this gap requires the incorporation of complementary analytical tools such as digital forensics and enterprise risk management (ERM) to enhance the explanatory power of the model and provide a more holistic understanding of fraud risk in modern organizations.

The selection of the Fraud Hexagon framework in this study is based on its ability to encompass behavioral and structural dimensions underlying fraudulent financial reporting (FFR). It extends beyond the classical Fraud Triangle and Fraud Diamond by including arrogance and collusion, two critical elements that better explain managerial hubris and collaborative unethical behavior in organizations. Nevertheless, prior studies employing this theory have often overlooked the moderating influence of governance mechanisms, resulting in inconclusive empirical outcomes across different sectors and contexts.

Imbalances in the implementation of corporate governance arising from information asymmetry can also contribute to financial fraud (J. Li, 2025). Corporate governance plays a vital role in preventing FFR, particularly in the banking sector, which is highly susceptible to financial statement manipulation. Some companies adopt governance mechanisms to restore their image and credibility following fraud scandals (Kassem, 2022). Governance structures such as audit committees serve as critical mechanisms for minimizing such risks. Evidence from Sari et al. (2022, 2024) demonstrates that audit committees can moderate several aspects of the Fraud Hexagon, such as industry nature, board changes, financial stability, and political connections, indicating that the audit committee functions not merely as a symbolic governance feature but as a practical control tool to reduce FFR.

However, limited empirical research has examined how these governance mechanisms interact with the Fraud Hexagon dimensions to influence FFR, particularly within emerging markets such as Indonesia. This study, therefore, seeks to address this gap by integrating the Fraud Hexagon framework with the audit committee, offering a comprehensive behavioral governance perspective on mitigating financial statement fraud in the banking sector.

The distinct contribution of this study lies in the introduction of moderating variables. Specifically, this research combines audit committees as moderating factors in analyzing the relationship between the Fraud Hexagon theory and FFR. Previous studies, such as Khamainy et al. (2022), were limited to the Fraud Diamond framework, focusing only on the antecedents of fraudulent behavior. Other studies (Achmad et al., 2022b; Alfarago & Mabrur, 2022; Bader et al., 2024; Indrijawati et al., 2025; Junus et al., 2025; Naldo & Widuri, 2023; Sahla & Ardianto, 2023; Setiawan & Soewarno, 2025a; Sudrajat et al., 2023) applied fraud theories independently without incorporating governance mechanisms as moderating variables. Meanwhile, research by Achmad et al. (2024), Oktaviany and Reskino (2023), and Sari et al. (2022, 2024) only examined the moderating role of audit committees in FFR. The inconsistencies in prior findings and the growing urgency of FFR incidents motivate this study to further analyze factors that can influence fraudulent reporting behavior in the banking sector.

This study enriches the fraud literature by extending the application of the Fraud Hexagon Theory to the Indonesian banking industry, where fraudulent financial reporting can have profound systemic implications. While the Fraud Triangle and Fraud Diamond frameworks have been widely applied, they overlook critical behavioral dimensions such as ability, arrogance, and external pressure. These aspects are particularly relevant in banking, where managers possess advanced technical expertise, exhibit high confidence in complex decision-making, and face substantial regulatory and market pressures. By incorporating these additional elements, the Fraud Hexagon framework provides a more comprehensive and contextually relevant lens to examine fraud risk within financial institutions operating in emerging markets.

Previous research on FFR has predominantly focused on internal managerial and financial determinants, often overlooking the psychological, structural, and institutional aspects that drive fraudulent actions. Traditional theoretical frameworks, including the Fraud Triangle and Fraud Pentagon, have not adequately explained the interaction between cognitive biases, corporate culture, and governance mechanisms that enable fraud in the banking environment. Prominent global cases such as Wirecard, Wells Fargo, and the 2008 financial crisis demonstrate how weaknesses in governance and ethical oversight can trigger financial misconduct and create widespread economic repercussions.

This study is among the few empirical investigations that evaluate the explanatory strength of the Fraud Hexagon Theory in understanding FFR within the banking industry. It also emphasizes the critical moderating role of corporate governance mechanisms, particularly audit committees, in mitigating fraudulent reporting practices. These governance structures enhance monitoring effectiveness, reinforce ethical accountability, and reduce opportunities for misrepresentation in financial statements.

This study, therefore, contributes to both theory and practice by integrating behavioral, organizational, and governance perspectives into a unified framework for detecting and preventing FFR in emerging market banks. The findings are expected to offer practical insights for regulators and policymakers in designing governance structures that strengthen financial reporting integrity, promote transparency, and enhance confidence in the global banking system.

2. Materials and Methods

The Fraud Hexagon Theory is an evolution of previous theories related to the causes of fraud. It begins with the Fraud Triangle by Cressey (1953), which includes pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. This was later expanded into the Fraud Diamond by Wolfe and Hermanson (2004) with the addition of capability and further refined into the Fraud Pentagon by Crowe (2011), which added competence and arrogance. The theory was perfected by Vousinas (2019) through the Fraud Hexagon Theory, which introduced collusion as the sixth factor, making the model more comprehensive in explaining the causes of FFR (Vousinas, 2019). The theory explains that fraudulent actions are driven not only by pressure and opportunity but also by the perpetrator’s ability, self-justification, overconfidence, and collaboration with other parties. If all these factors align, the potential for fraud within an organization, particularly in financial reporting, increases significantly (Sudrajat et al., 2023; Yaumil & Thaifur, 2025).

2.1. Determinant Fraud Hexagon on FFR

External pressure on companies, often referred to as external pressure (Achmad et al., 2022a), may arise from various sources such as shareholder expectations, debt obligations, market competition, or macroeconomic fluctuations. Within the Fraud Hexagon Theory, such external demands represent one of the motivational forces driving individuals to engage in unethical behavior when performance targets cannot be achieved through legitimate means. A common proxy used to measure external pressure is leverage, the ratio of total debt to total assets. Theoretically, a high leverage ratio indicates a company’s dependence on external financing, which increases both contractual constraints and performance pressure on management. From the agency theory perspective, debt holders impose contractual monitoring mechanisms that may intensify an agent’s incentive to behave opportunistically by manipulating financial reports to appear compliant with creditor expectations.

External pressure becomes particularly pronounced when firms face difficulties repaying high-risk debt. The higher the credit risk, the more reluctant lenders are to extend credit (Achmad et al., 2022a). Consequently, elevated leverage levels heighten financial strain on firms to meet debt obligations (Lin, 2024), which may drive management to manipulate financial statements, such as through premature revenue recognition or expense concealment, to portray financial health and avoid reputational or regulatory consequences (Viana et al., 2022; Sari et al., 2022). However, in the presence of strong corporate governance, robust oversight structures, such as active audit committees and transparent debt policies, can effectively mitigate such pressure and restrain managerial tendencies toward fraudulent behavior. Achmad et al. (2022a) similarly emphasize that sound governance reduces the likelihood of unhealthy debt practices.

The opportunity element in the Fraud Hexagon reflects the presence of weak oversight systems that enable management to exploit internal control deficiencies for fraudulent purposes. Within this theoretical context, ineffective monitoring represents a structural failure of internal control mechanisms such as boards of commissioners, audit committees, or internal auditors to identify irregularities promptly. The Fraud Hexagon posits that when the perceived probability of detection is low, the perceived opportunity to commit fraud increases correspondingly. T. Li et al. (2021) provide empirical support for this notion, showing that weak internal oversight increases management’s capacity to manipulate financial statements without detection. Similarly, Rostami and Rezaei (2022) argue that weak supervisory boards undermine accountability in financial reporting. From a governance standpoint, ineffective monitoring implies a lack of transparency and accountability, thereby creating structural vulnerabilities that foster fraud (Babalola et al., 2025). Strengthening governance mechanisms, therefore, directly reduces perceived opportunity, consistent with the theoretical expectation that effective oversight serves as a deterrent to fraudulent acts.

Based on the Fraud Hexagon Theory (Vousinas, 2019), auditor switching is closely related to the rationalization component, in which management justifies manipulative behavior through the selection of more compliant or less experienced auditors. This theoretical linkage demonstrates how rationalization operates not only as an internal cognitive process but also as an organizational strategy. Achmad et al. (2022a) found that auditor switching may facilitate fraud if not accompanied by adequate oversight mechanisms. Likewise, Ghaisani and Supatmi (2023) highlight that auditor switching can serve as a rationalization device for concealing past irregularities, as newly appointed auditors often lack familiarity with the company’s reporting history. The absence of strong governance oversight allows this risk to persist, diminishing the effectiveness of external auditing. Studies by Sari et al. (2022) and Naldo and Widuri (2023) further confirm that frequent auditor changes increase the likelihood of fraud, particularly when audit committees are passive in auditor selection and evaluation processes. Conversely, Wahyuningtyas and Aisyaturrahmi (2022) demonstrate that under strong governance, the audit committee’s involvement in auditor rotation safeguards independence and prevents auditor switching from becoming a rationalization pathway for fraud.

The Fraud Hexagon also incorporates the change in management element, often associated with leadership transitions that can reshape the control environment. The appointment of a new CEO introduces significant behavioral and strategic adjustments that, if poorly monitored, may be exploited to justify manipulative reporting practices (Devi et al., 2021). This dimension aligns with both the rationalization and capability aspects of the theory, as new leaders may perceive themselves as having the authority and justification to restructure accounting policies in line with their strategic vision. Wulandari and Maulana (2022) suggest that ambitious new CEOs often rationalize aggressive reporting as part of organizational transformation, while Masruroh and Carolina (2022) emphasize that the absence of early-stage control mechanisms heightens the risk of misconduct.

From a corporate governance standpoint, leadership transitions require vigilant oversight by boards and nomination committees to prevent excessive managerial dominance. Agency theory posits that unchecked CEO authority increases agency costs through moral hazard and opportunistic behavior. Supporting this view, Lee and Bose (2025) find that transparent and formalized succession planning reduces uncertainty and opportunism during CEO transitions. Global evidence from Wang et al. (2023) also reveals that frequent CEO turnover produces only short-term benefits unless supported by strong governance structures. Furthermore, Wang et al. (2023) highlight that forced CEO turnover often reflects weak board oversight, which damages director reputations and erodes shareholder trust through increased voting pressure.

The arrogance dimension of the Fraud Hexagon describes excessive managerial confidence, where individuals believe their status or expertise places them beyond accountability. In this context, the CEO’s image symbolizes a visible manifestation of managerial overconfidence, reflected in media exposure, awards, or self-promotional activities (Capalbo et al., 2018). This behavioral characteristic aligns with the psychological element of the theory, wherein arrogance serves as a self-rationalized belief that ethical norms do not apply to high-performing executives. Empirical studies by Rijsenbilt and Commandeur (2013) and Devi et al. (2021) confirm that image-driven CEOs are more inclined to conceal unfavorable financial information to protect their reputation. From a governance perspective, unchecked executive dominance undermines board independence and distorts decision-making processes. Biduri and Tjahjadi (2024) identify CEO arrogance as a key determinant of fraudulent financial reporting, even in industries with strong ethical norms. Accordingly, effective governance frameworks must establish institutional boundaries that limit executive power and ensure balanced decision-making through active board and audit committee engagement.

The final dimension of the Fraud Hexagon, collusion, captures the interaction between internal corporate actors and external parties that jointly enable fraudulent activities. Salehi et al. (2023) report that politically connected firms are more likely to distort financial statements to maintain political favor and avoid regulatory sanctions. This finding aligns with agency theory, as political connections introduce an additional principal-agent layer, intensifying conflicts of interest between corporate objectives and public accountability. Ahmad et al. (2022) further reveal that relationships with government officials are often exploited to evade scrutiny, while Struckell et al. (2022) emphasize that firms involved in state projects experience short-term performance pressures that encourage manipulation. Within sound governance systems, political involvement must be carefully managed to prevent undue influence and preserve independence in financial oversight. Emphasize that political connections substantially increase the risk of fraud when internal controls are weak, whereas Ariningrum and Diyanty (2017) argue that such affiliations undermine the effectiveness of the board by diverting loyalty from professional integrity toward external interests. Hence, strong corporate governance, through enhanced transparency, independent audit committees, and effective external oversight, is crucial to counterbalance political influence and uphold the integrity of financial reporting.

The reviewed literature collectively suggests that the six dimensions of the Fraud Hexagon—pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion—offer a multidimensional framework for understanding fraudulent financial reporting (FFR). External pressure, proxied by leverage, reflects financial strain that motivates management to manipulate earnings to sustain stakeholder confidence. Opportunity arises when weak governance and ineffective monitoring reduce detection risk. Rationalization manifests through managerial justifications, such as auditor switching or leadership transitions, which serve to legitimize unethical reporting behavior. Capability and arrogance amplify the likelihood of fraud when executives possess both technical expertise and excessive confidence in their ability to conceal misconduct. Collusion highlights the cooperative dimension of fraud, showing how coordination among internal and external actors can circumvent internal controls.

From a corporate governance perspective, mechanisms such as audit committees are designed to counter these behavioral drivers by enhancing oversight and accountability. Prior studies indicate that active audit committees can detect irregularities and constrain managerial discretion, while institutional investors act as external monitors that promote transparency and long-term performance integrity. Nonetheless, empirical findings remain fragmented, particularly concerning how these governance mechanisms interact with the Fraud Hexagon dimensions within emerging market banking contexts.

Accordingly, this study develops hypotheses to empirically examine the relationships between Fraud Hexagon components and fraudulent financial reporting, while assessing the moderating roles of audit committees. By integrating behavioral and governance perspectives, the present research aims to advance theoretical understanding and provide empirical evidence on how multidimensional fraud determinants and governance mechanisms jointly shape the risk of financial statement fraud in Indonesia’s banking sector.

H1:

Leverage has a positive effect on fraudulent financial reporting.

H2:

Ineffective monitoring has a positive effect fraudulent financial reporting.

H3:

Auditor switching has a positive effect on fraudulent financial reporting.

H4:

Director Change has a positive effect on fraudulent financial reporting.

H5:

CEO Picture has a positive effect on fraudulent financial reporting.

H6:

Political connections has an effect on fraudulent financial reporting.

2.2. The Moderating Role of Audit Committee on FFR

In the governance context, the audit committee plays a strategic role in preventing fraud by overseeing financial reporting processes, ensuring auditor independence, and evaluating management accounting policies. An effective audit committee enhances audit quality (Hassan et al., 2025), improves reporting transparency (Babalola et al., 2025), and constrains earnings manipulation (Badolato et al., 2014). The following hypotheses are developed based on the six dimensions of the Fraud Hexagon and the moderating role of the audit committee.

High leverage increases financial pressure on firms and may drive management to engage in fraudulent behavior to maintain a favorable financial image (Achmad et al., 2022a; Lin, 2024; Viana et al., 2022). However, an active audit committee can mitigate the influence of leverage on fraud by strengthening financial oversight (Badolato et al., 2014). A competent and independent audit committee can objectively assess financing structures and debt risks while ensuring that management remains transparent in financial reporting. Hassan et al. (2025) emphasize that the financial expertise of audit committee members is critical in detecting fraud symptoms arising from leverage-related pressures. Through strong governance and collaboration with external auditors, the audit committee ensures that financing strategies do not become loopholes for manipulation (Wulandari & Maulana, 2022; Yaumil & Thaifur, 2025).

Ineffective monitoring represents a key dimension of the Fraud Hexagon, reflecting weak oversight of managerial activities that creates opportunities for fraud. When internal control mechanisms such as boards of commissioners or internal audit systems are suboptimal, management has greater discretion to manipulate financial statements (Biduri & Tjahjadi, 2024). Under such circumstances, an effective audit committee is vital to closing oversight gaps. The audit committee functions as a secondary control mechanism that compensates for weaknesses in internal control by conducting in-depth reviews of financial reports, external audits, and compliance with accounting standards. Hassan et al. (2025) find that audit committees with high competence and independence can mitigate the negative effects of weak internal monitoring. Likewise, Babalola et al. (2025) show that the frequency and quality of audit committee meetings are positively associated with their ability to detect early indicators of fraud. Hence, an active, integrity-driven audit committee can moderate the effect of ineffective monitoring on fraudulent financial reporting.

Auditor switching can also be exploited by management to rationalize manipulative actions, particularly when new auditors are unfamiliar with the firm’s risk profile (Achmad et al., 2022a; Naldo & Widuri, 2023). A strong audit committee can oversee the auditor-switching process to ensure that it is not used as a means to conceal potential fraud (Quick et al., 2024). The audit committee can evaluate the independence and professional background of new auditors as part of its governance oversight. Studies by Sari et al. (2022), Yodemonstrate that auditor transitions conducted without audit committee involvement increase fraud risk. In contrast, when the audit committee is actively involved, the switching process becomes more transparent and less prone to manipulation (Badolato et al., 2014).

A new CEO often introduces strategic and accounting changes that may be exploited for fraudulent purposes, particularly during poorly monitored transitions (Biduri & Tjahjadi, 2024; Masruroh & Carolina, 2022). An active audit committee can evaluate the risks associated with management changes and assess the consistency of financial reporting throughout leadership transitions (Felix et al., 2024). Wahyuningtyas and Aisyaturrahmi (2022) emphasize the audit committee’s role as a strategic overseer during such transitions. The audit committee can assist the board of commissioners in reviewing new CEO policies and preventing excessive managerial dominance (Yaumil & Thaifur, 2025; Hassan et al., 2025; Gorshunov et al., 2021).

CEOs who prioritize personal image (CEO Picture) often strive to preserve their external reputation, even through manipulative reporting. In the Fraud Hexagon, this reflects the arrogance dimension—overconfidence in the belief that fraudulent acts will go undetected (Capalbo et al., 2018; Rijsenbilt & Commandeur, 2013). CEOs with high media visibility frequently feel insulated from oversight, particularly under weak control systems. An effective audit committee can counterbalance CEO dominance by objectively evaluating corporate reporting and strategic decisions. Hassan et al. (2025) and Badolato et al. (2014) find that audit committees with strong financial expertise and independence are better equipped to identify image-driven manipulation. Therefore, the audit committee’s presence is crucial in preventing reputation-motivated fraud.

In some cases, weak governance structures facilitate collusion between management, internal auditors, and boards. A high-quality audit committee comprising members with independence, board experience, financial expertise, and share ownership has been shown to reduce corruption and financial manipulation (Gorshunov et al., 2021). Even in weak institutional environments, the audit committee can safeguard external stakeholder interests (Ashiru et al., 2024). The audit committee acts as a catalyst for healthy corporate governance. Studies by Yaumil and Thaifur (2025), and Mutmainah and Mahmudah (2025) highlight the importance of an active audit committee in reinforcing governance and preventing executive dominance over oversight processes. Overall, the audit committee serves as a key safeguard for transparency and accountability within organizations.

H7:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of leverage on fraudulent financial reporting.

H8:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of institutional monitoring on fraudulent financial reporting.

H9:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of auditor switching on fraudulent financial reporting.

H10:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of Director Change on fraudulent financial reporting.

H11:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of CEO Picture on fraudulent financial reporting.

H12:

The Audit Committee moderates the influence of political connections on fraudulent financial reporting.

3. Results

This study investigates banking companies in Indonesia from 2021 to 2024 as published on the IDX website. The sample was selected using a purposive sampling method. Out of 49 listed companies, only 35 samples were used in the study due to several criteria. The data were obtained from secondary data sourced from the official IDX website. The researcher used WarpPLS 7.0 with the SEM-PLS analysis method. Corporate governance is implemented through various structural indicators that reflect the quality of oversight. Specifically board size, the proportion of independent commissioners, the effectiveness of the audit committee, the existence of a risk committee, and the quality of the external auditor (e.g., association with the Big Four). This governance structure serves as a variable that can strengthen or weaken the relationship between fraud risk factors and financial statement manipulation. For example, an independent and active audit committee can reduce opportunity-driven fraud, while strong external audit quality can limit ability-driven fraud. The sample criteria used in this study are presented in Table 1. This study applies an analysis using the following model:

FFR = α + β1Lev + β2BDOUT + β3AChange + β4DChange + β5CEOPic + β6PolCon +

β7(Lev × AudCom) + β8(BDOUT × AudCom) + β9(AChange × AudCom) +

β10(DChange × AudCom) + β11(CEOPic × AudCom) + β12(PolCon × AudCom) + e

β7(Lev × AudCom) + β8(BDOUT × AudCom) + β9(AChange × AudCom) +

β10(DChange × AudCom) + β11(CEOPic × AudCom) + β12(PolCon × AudCom) + e

Table 1.

Sample criteria.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all variables used in the study with a total of 140 observations. The results show variations across variables, indicating differences in leverage, internal inefficiency, and governance characteristics among firms. These variations provide a strong basis for further regression analysis on financial fraudulent reporting (FFR). Table 3 demonstrates that all model fit indices meet the recommended statistical thresholds, confirming the robustness and validity of the structural model. The Average Path Coefficient (APC), R-squared measures, and collinearity diagnostics indicate that the model is free from multicollinearity and exhibits strong explanatory power. All variable definitions and data descriptions are provided in the supplementary Excel file (Supplementary File S1).

Table 2.

Descriptive result of statistics.

Table 3.

Model fit test result.

Table 4 defines the operationalization and measurement of variables representing fraud antecedents within the Fraud Hexagon framework, encompassing pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion, along with audit committee competence as moderating factors. These constructs were measured using validated financial and governance proxies adapted from prior empirical studies, ensuring theoretical rigor and methodological consistency.

Table 4.

(A) Operational definition and measurement of variables: relative data used in the study. (B) Operational definition and measurement of variables: binary data used in the study.

4. Discussion

This study adopts the Fraud Hexagon framework by Vousinas (2019) to analyze the relationship between pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion in influencing FFR. Understanding these interconnected elements helps organizations enhance corporate governance and reduce fraud risks through accountability and transparency.

Before discussing the hypothesis results, it is important to note several technical aspects in Table 4A,B that require correction. The variable CeoCha should be clearly defined as “1 if there is a change in CEO/President Director.” This definition should not be combined with the operational definition of the Achange variable. In addition, the variable names (BDOUT, AudCom, Dchange) should remain consistent with those listed in the operational variable table. Furthermore, the coefficient β5 was written twice for the variables CEOPic and PolCon, indicating a possible typographical or model specification error. These inconsistencies should be addressed to ensure data integrity and model reliability.

The hypothesis tests (H1) reveal that leverage does not significantly affect FFR. This suggests that external pressure from creditors due to high leverage does not necessarily lead to fraud, possibly because of stronger internal controls and governance structures (Guo et al., 2019). This finding aligns with Fitriana et al. (2024), who argue that ethical decision-making in response to financial pressure is shaped by market dynamics and governance quality. Similarly, Anisykurlillah et al. (2023) found that companies emphasizing ethics and stakeholder engagement tend to have lower FFR levels, even under high leverage.

Ineffective monitoring occurs when a company lacks an internal unit that effectively oversees its performance (Biduri & Tjahjadi, 2024). The test results for H2 indicate that ineffective monitoring has a positive and significant effect on FFR, confirming that when independent commissioners fail to perform their oversight duties effectively, management gains greater latitude to manipulate financial statements. The absence of effective supervision increases the likelihood of dishonest behavior. This result supports the findings of Owusu et al. (2022), Rashid et al. (2023), and Biduri and Tjahjadi (2024).

For H8, which examines the moderating role of the audit committee on the relationship between ineffective monitoring and FFR, the result is rejected, showing that this mechanism does not significantly reduce the risk. This finding is consistent with Yang et al. (2017), who found that audit committee characteristics and supervisory boards may not effectively control financial fraud in China.

The results for H3 show that auditor switching positively and significantly affects FFR. Frequent auditor changes provide opportunities for management to obscure fraudulent practices, consistent with Erena et al. (2022) and Sari et al. (2024). However, the moderating test (H9) for the audit committee is rejected, implying limited moderating power.

The results for H4 indicate that director change significantly affects FFR. This finding supports Sari et al. (2024) and Biduri and Tjahjadi (2024), who also observed that leadership replacement tends to enhance governance credibility rather than facilitate fraud. Nonetheless, the moderation test (H10) again shows no significant effect, confirming the limited influence of the audit committee in this context.

For H5, the CEO image variable is found to have no significant direct effect on FFR, aligning with Handoko and Salim (2022) which highlight that visual representation in reports reflects professionalism rather than arrogance. However, H11 testing the moderating effect of the audit committee is accepted (p < 0.001, β = 0.281), showing that the audit committee effectively mitigates the impact of managerial arrogance on FFR. This finding strengthens the role of the audit committee in controlling symbolic self-presentation and ensuring ethical disclosure (Hassan et al., 2025; Badolato et al., 2014).

The results for H6 indicate that political connections of agencies do not significantly affect FFR, consistent with the notion that collaboration alone does not ensure compliance. Yet, H12 is accepted, showing that the audit committee strengthens the fraud-reducing effect of political connections. This emphasizes that the audit committee’s active oversight can translate interorganizational cooperation into improved ethical performance.

Table 5 summarizes the hypothesis results and highlights several important considerations. The study tested one moderator (Audit Committee) across six Fraud Hexagon variables, producing 12 interaction hypotheses. With a total of 35 firms (140 observations over four years), this design provides a balanced approach while minimizing the risk of overfitting.

Table 5.

Summary of results.

Overall, the findings suggest that while direct effects such as ineffective monitoring, auditor switching, and director change significantly influence FFR, only certain moderating effects, specifically those involving the audit committee with the CEO picture and political connections are statistically significant. This implies that governance mechanisms play a selective yet meaningful role in mitigating fraudulent financial reporting within the Fraud Hexagon framework.

4.1. Moderating Effect of Audit Committee on Fraudulent Financial Reporting: The Two-Stage Approach

Due to the exogenous and/or moderator variables being formative, the pairwise multiplication of indicators is not feasible. ‘Since formative indicators are not assumed to reflect the same underlying construct (i.e., they can be independent of one another and measure different factors), the product indicators between two sets of formative indicators will not necessarily tap into the same underlying interaction effect’ (Chin et al., 2003). Therefore, we use a two-stage PLS approach to estimate moderating effects when formative constructs are involved. This makes use of the advantage of PLS path modeling in explicitly estimating latent variable scores. The two stages are set out as follows:

Stage 1: In the first stage, we run the main effect PLS path model to obtain estimates for the latent variable scores. These scores are then calculated and saved for further analysis.

Stage 2: In the second stage, the interaction term (X) × Moderator (M) is formed as the element-wise product of the latent variable scores of X and M, and this interaction term, along with the latent variable scores of X and M, is used as an independent variable in a multiple linear regression of the latent variable scores of Y. The second stage can be realized by implementation within PLS path modeling by means of single-indicator measurement models.

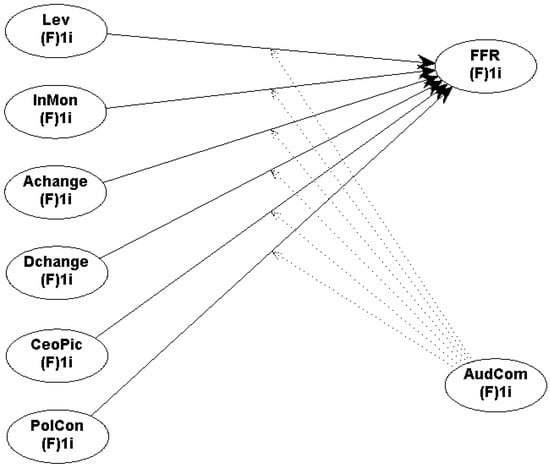

Figure 1 illustrates the two-stage approach. Whilst in the first stage the latent variable scores are estimated, these are used in the second stage to determine the coefficients of the regression function in the form of Formula.

Stage 1: Y = α + β1X1 + β2X2 + β3X3 + β4X4 + β5X5 + β6X6 + β7M.

Stage 2: Y = α + β1X1 + β2X2 + β3X3 + β4X4 + β5X5 + β6X6 + β7M + β8X1 × M + β9X2 × M + β10X3 × M + β11X4 × M + β12X5 × M + β13X6 × M.

Figure 1.

A two-stage PLS approach to model interaction effects with formative constructs involved.

4.2. Interpreting Moderating Effects

To analyze the moderating effects, we examine the direct relationships between the exogenous and moderator variables (Figure 1 and Formula (1)), as well as the relationship between the interaction term (Formula (1)) and the endogenous variable FFR. The hypothesis of a moderating effect is supported if the path coefficient (β9–β13) is significant, regardless of the values of β1–β7 (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Firstly, it must be determined whether the moderating effects exist in the population to which the researcher wishes to generalize the research results. In other words, a test must be conducted to establish whether the path coefficient capturing the moderating effect differs significantly from zero. Secondly, the strength of the identified moderating effect must be assessed.

4.2.1. Determining the Significance of Moderating Effects

As PLS path modeling does not rely on distributional assumptions, statistical tests for direct inference and model fit are not available. Bootstrapping is recommended as a solution to this (Chin, 2009). Bootstrapping is a non-parametric technique used to estimate the standard errors of model parameters (Tibshirani & Efron, 1993). The ratio of a model parameter to its standard deviation is asymptotically distributed according to a student’s t-distribution. The significance of the model parameters, and particularly the interaction term coefficient, can be determined using the relevant tables.

4.2.2. Determining the Strength of Moderating Effects

The estimated path coefficient β1–β7 describes the influence of the exogenous variable’s (Leverage, Ineffective Monitoring, Auditor Switching, Director Change, CEO Picture, Political Connections) influence on the endogenous variable (FFR) when the moderator variable (auditor committee) is zero (i.e., its mean). The path coefficient (β9–β13) of the interaction term shows how much the influence of the exogenous variable on the endogenous variable changes depending on the moderating variable. In the case of standardized variables, the following interpretation is possible: If the moderator variable is one, i.e., one standard deviation higher than its mean, the influence of the exogenous variable on the endogenous variable is (β1–β7) + (β9–β13) (in the nomenclature of Figure 1 and Formula (1)). Furthermore, the moderating effect can be assessed by comparing the proportion of variance explained by the main effect model (i.e., the model without the moderating effect) with that explained by the full model (i.e., the model including the moderating effect). This concept also underpins the effect size. Drawing on Cohen (1988), we suggest calculating the effect size f2 using the following Formula (3):

Moderating effects with effect sizes f2 of 0.02 may be regarded as weak, effect sizes from 0.15 as moderate, and effect sizes above 0.35 as strong (Chin et al., 2003).

Table 6 summarizes the results obtained in the two-stage analysis; the R2 value increased to 0.152 from 0.124, which is an increase of 22.6%. The path coefficient of Leverage β increased to −0.251 from −0.206, which is an increase (negative sign) of 21.8%, and the strength of the relationship between leverage and FFR decreased when the audit committee increased in the presence of the audit committee as a moderator. The effect size is 0.003 (p < 0.001), which is weak according to (Chin et al., 2003).

Table 6.

Moderating effect of audit committee on FFR.

The path coefficient of Ineffective Monitoring β increased to 0.228 from 0.205, which is an increase of 11.2%, and the strength of the relationship between ineffective monitoring and FFR increased when the audit committee acted as a moderating variable. The effect size is 0.000 (p < 0.001), which is weak according to (Chin et al., 2003).

The path coefficient of Auditor Change β decreased to 0.144 from 0.156, which is a decrease of 7.7%, and the strength of the relationship between auditor change and FFR decreased when the audit committee increased in the presence of the audit committee as moderator. The effect size is 0.003 (p < 0.001), which is weak according to (Chin et al., 2003).

The path coefficient of Director Change β decreased to 0.153 from 0.176, which is a decrease of 13.1%, and the strength of the relationship between director change and FFR decreased when the audit committee increased in the presence of the audit committee as moderator. The effect size is 0.000 (p < 0.001), which is weak according to (Chin et al., 2003).

The path coefficient of CEO Picture β increased to −0.132 from −0.072, which is an increase (negative sign) of 83.3%, and the strength of the relationship between CEO Picture and FFR increased (negative sign) when the audit committee increases in the presence of audit committee as a moderator. The effect size is 0.028 (p < 0.001), which is moderate according to (Chin et al., 2003).

The path coefficient of Political Connections β decreased to −0.096 from −0.126, which is a decrease (negative sign) of 23.8%, and the strength of the relationship between Political Connections and FFR decreased (negative sign) in the presence of the audit committee as a moderator. The effect size is 0.017 (p < 0.001), which is weak according to (Chin et al., 2003).

5. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence on how corporate governance mechanisms and fraud risk management practices influence the occurrence of Fraudulent Financial Reporting (FFR) within the Indonesian banking sector from 2021 to 2024. Drawing on the Fraud Hexagon framework, which incorporates six elements: pressure, opportunity, rationalization, capability, arrogance, and collusion, the research aims to identify how governance and risk structures mitigate financial misreporting risks in a highly regulated industry.

The findings reveal that although banks with high leverage levels face stronger external pressures from creditors and investors, such financial stress does not necessarily result in fraudulent reporting. This is attributed to the implementation of robust internal control systems, governance oversight, and compliance mechanisms, which serve as integral components of a bank’s fraud risk management system. Institutions that prioritize ethical leadership, transparency, and stakeholder accountability tend to exhibit lower fraud risk exposure, even under high leverage conditions.

However, the results indicate that ineffective monitoring, characterized by weak internal audit functions and passive board supervision, significantly increases the likelihood of FFR. This emphasizes the critical role of independent commissioners and board-level risk oversight in maintaining the integrity of financial reporting. The analysis of audit committees as moderating variables shows that while theoretically positioned to strengthen accountability, their influence on reducing FFR is statistically insignificant. This suggests that governance effectiveness depends not merely on structural presence but also on the independence, competence, and proactivity of oversight bodies.

The study also finds that auditors switching positively affects FFR, implying that frequent changes in external auditors weaken continuity and audit quality, increasing fraud risk. Conversely, symbolic indicators of managerial arrogance, such as CEO picture disclosure and political connections, do not have significant direct effects on FFR. These results suggest that in the banking context, reputational signaling does not necessarily reflect arrogance or increased fraud propensity. Nonetheless, active audit committees can mitigate potential manipulation by enforcing risk-based audit practices and ethical standards.

From a risk management perspective, the study highlights that corporate governance mechanisms, including board independence, audit committee effectiveness, and risk committee authority, function as the first line of defense against financial reporting fraud. Strengthening risk governance structures not only minimizes internal control failures but also enhances the resilience of banks against operational and reputational risks. Regulatory agencies such as Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority (OJK) and the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises (BUMN) are advised to reinforce governance disclosure requirements, enforce auditor rotation policies, and restrict CEO duality to enhance transparency and accountability across the sector.

Overall, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on governance-based fraud risk management by providing empirical evidence from a developing financial system. By linking the Fraud Hexagon model with corporate governance mechanisms and financial data from the banking sector, the study demonstrates how effective governance frameworks operate as a form of strategic risk control, reducing the likelihood of fraudulent reporting and strengthening financial stability. The findings underscore that governance is not merely a compliance tool but a core component of enterprise risk management in safeguarding the integrity of financial systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jrfm18120698/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, resources, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, I.D.P.; writing—original draft, software, methodology, visualization, data curation, P.A.S. and M.A.A.A.; writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, A.A.P.; formal analysis, writing—original draft, R.K.; review and editing, validation, resources, M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.A.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors have declared that this research is based on publicly available data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACFE. (2020). Report to the nations, 2020 global study on occupational fraud and abuse. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. Available online: https://acfepublic.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/2020-Report-to-the-Nations.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Achmad, T., Ghozali, I., & Pamungkas, I. D. (2022a). Hexagon fraud: Detection of fraudulent financial reporting in state-owned enterprises Indonesia. Economies, 10(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, T., Ghozali, I., & Pamungkas, I. D. (2024). Detecting fraudulent financial statements with analysis fraud hexagon: Evidence from state-owned enterprises Indonesia. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 21, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, T., Ghozali, I., Rahardian, M., Helmina, A., Hapsari, D. I., & Pamungkas, I. D. (2022b). Detecting fraudulent financial reporting using the Fraud Hexagon model: Evidence from the banking sector in Indonesia. Economies, 11(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F., Bradbury, M., & Habib, A. (2022). Political connections, political uncertainty and audit fees: Evidence from Pakistan. Managerial Auditing Journal, 37(2), 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarago, D., & Mabrur, A. (2022). Do Fraud Hexagon components promote fraud in Indonesia? Etikonomi, 21(2), 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisykurlillah, I., Ardiansah, M. N., & Nurrahmasari, A. (2023). Fraudulent financial statements detection using fraud triangle analysis: Institutional ownership as a moderating variable. Accounting Analysis Journal, 11(2), 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariningrum, I., & Diyanty, V. (2017). The impact of political connections and the effectiveness of board of commissioner and audit committees on audit fees. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 11(4), 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiru, F., Adegbite, E., Frecknall-Hughes, J., & Daodu, O. (2024). Reliability of the audit committee in weak institutional environments: Evidence from Nigeria. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 57, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, F. I., Kokogho, E., Odio, P. E., Adeyanju, M. O., & Sikhakhane-Nwokediegwu, Z. (2025). Audit committees and financial reporting quality: A conceptual analysis of governance structures and their impact on transparency. International Journal of Management and Research, 4(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A. A., Abu Hajar, Y. A., Weshah, S. R. S., & Almasri, B. K. (2024). Predicting risk of and motives behind fraud in financial statements of Jordanian industrial firms using hexagon theory. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(3), 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badolato, P. G., Donelson, D. C., & Ege, M. (2014). Audit committee financial expertise and earnings management: The role of status. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biduri, S., & Tjahjadi, B. (2024). Determinants of financial statement fraud: The perspective of pentagon fraud theory (evidence on Islamic banking companies in Indonesia). Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capalbo, F., Frino, A., Lim, M. Y., Mollica, V., & Palumbo, R. (2018). The impact of CEO narcissism on earnings management. Abacus, 54(2), 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (2009). Bootstrap cross-validation indices for PLS path model assessment. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 83–97). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. R. (1953). Other people’s money, dalam “detecting and predicting financial statement fraud: The effectiveness of the fraud triangle and SAS no 99”. Journal of Corporate Governance and Firm Performance, 13, 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, H. (2011). Why the fraud triangle is no longer enough. Horwath, Crowe LLP. Available online: https://www.fraudconference.com/uploadedFiles/Fraud_Conference/Content/Course-Materials/presentations/23rd/ppt/10C-Jonathan-Marks.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Dechow, P. M., Ge, W., Larson, C. R., & Sloan, R. G. (2011). Predicting material accounting misstatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(1), 17–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P. N. C., Widanaputra, A. A. G. P., Budiasih, I. G. A. N., & Rasmini, N. K. (2021). The effect of fraud pentagon theory on financial statements: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 1163–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Erena, O. T., Kalko, M. M., & Debele, S. A. (2022). Corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance: Empirical evidence from medium and large-scale manufacturing firms in Ethiopia. Corporate Governance (Bingley), 22(2), 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, R., Mansi, S., & Pevzner, M. (2024). Audit committee–CFO political dissimilarity and financial reporting quality. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 45, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriana, L., Sinarasri, A., & Nurcahyono, N. (2024). Factors affecting financial statement fraud in banking sector: A agency perspective. Maksimum, 14(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaisani, A. A., & Supatmi, S. (2023). Detection of financial statement fraud using the fraud pentagon theory. OWNER: Journal of Accounting and Research, 7(1), 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshunov, M. A., Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G., & Walker, H. J. (2021). Quad-qualified audit committee director: Implications for monitoring and reducing financial corruption. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Huang, P., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Do debt covenant violations serve as a risk factor of ineffective internal control? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 52(1), 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, B. L., & Salim, A. S. J. (2022, June 24–27). Fraud detection using Fraud Hexagon model in top index shares of KOMPAS 100. 2022 12th international workshop on computer science and engineering, WCSE 2022 (pp. 112–116), Xiamen, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. W. U., Kiran, S., Gul, S., Khatatbeh, I. N., & Zainab, B. (2025). The perception of accountants/auditors on the role of corporate governance and information technology in fraud detection and prevention. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(1), 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J., & Kirby, P. (2022). Wirecard trial of executives opens in German fraud scandal. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-63893933 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Indrijawati, A., Fitri, Y., & Ningsih, N. (2025). Antecedents of corruption in the perspective of local government employees: A Fraud Hexagon theory approach. Public and Municipal Finance, 14(1), 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junus, A., Sundari, S., & Azzahra, S. Z. (2025). Fraudulent financial reporting and firm value: An empirical analysis from the Fraud Hexagon perspective. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 22(1), 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, R. (2022). Elucidating corporate governance’s impact and role in countering fraud. In Corporate governance (Bingley) (Vol. 22, Issue 7, pp. 1523–1546). Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamainy, A. H., Ali, M., & Setiawan, M. A. (2022). Detecting financial statement fraud through new fraud diamond model: The case of Indonesia. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(3), 925–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPK. (2025). KPK ungkap fraud kredit di bank daerah capai Rp1,2 T—Nasional. Bloomberg Technoz. Available online: https://www.bloombergtechnoz.com/detail-news/71215/kpk-ungkap-fraud-kredit-di-bank-daerah-capai-rp1-2-t (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Lastanti, H. S., Murwaningsari, E., & Umar, H. (2022). The effect of hexagon fraud on fraud financial statements with governance and culture as moderating variables. Media Riset Akuntansi, Auditing & Informasi, 22(1), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H., & Bose, S. (2025). CEO turnover in family firms: The corporate transparency perspective. China Accounting and Finance Review, 27(2), 275–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. (2025). Corporate governance, fraud learning cycles, and financial fraud detection: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Research in International Business and Finance, 76, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Kou, G., Peng, Y., & Yu, P. S. (2021). An integrated cluster detection, optimization, and interpretation approach for financial data. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, 52(12), 13848–13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D. (2024). Key considerations to be applied while leveraging machine learning for financial statement fraud detection: A review. IEEE Access, 12, 168213–168228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masruroh, S., & Carolina, A. (2022). Beneish model: Detection of indications of financial statement fraud using CEO characteristics. Asia Pacific Fraud Journal, 7(1), 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutmainah, I., & Mahmudah, D. A. (2025). The moderation effect of Islamic corporate governance on fraud financial statement detection using fraud hexagon. Jurnal Akuntansi Aktual, 11(2), 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldo, R. R., & Widuri, R. (2023). Fraudulent financial reporting and fraud hexagon: Evidence from infrastructure companies in ASEAN. In Economic affairs (New Delhi) (Vol. 68, Issue 3, pp. 1455–1468). AESSRA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktaviany, F., & Reskino, R. (2023). Financial statement fraud: Pengujian Fraud Hexagon dengan moderasi audit committee. Jurnal Bisnis Dan Akuntansi, 25(1), 91–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, G. M. Y., Koomson, T. A. A., Alipoe, S. A., & Kani, Y. A. (2022). Examining the predictors of fraud in state-owned enterprises: An application of the fraud triangle theory. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 25(2), 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, R., Toledano, D. S., & Toledano, J. S. (2024). Measures for enhancing auditor independence: Perceptions of Spanish non-professional investors and auditors. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 30(2), 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M., Khan, N. U., Riaz, U., & Burton, B. (2023). Auditors’ perspectives on financial fraud in Pakistan—Audacity and the need for legitimacy. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 13(1), 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijsenbilt, A., & Commandeur, H. (2013). Narcissus enters the courtroom: CEO narcissism and fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, V., & Rezaei, L. (2022). Corporate governance and fraudulent financial reporting. Journal of Financial Crime, 29(3), 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahla, W. A., & Ardianto, A. (2023). Ethical values and auditors fraud tendency perception: Testing of fraud pentagon theory. Journal of Financial Crime, 30(4), 966–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M., Ammar Ajel, R., & Zimon, G. (2023). The relationship between corporate governance and financial reporting transparency. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 21(5), 1049–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M. P., Mahardika, E., Suryandari, D., & Raharja, S. (2022). The audit committee as moderating the effect of hexagon’s fraud on fraudulent financial statements in mining companies listed on the Indonesia stock exchange. Cogent Business and Management, 9(1), 2150118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M. P., Sihombing, R. M., Utaminingsih, N. S., Jannah, R., & Raharja, S. (2024). Analysis of hexagon on fraudulent financial reporting with the audit committee and independent commissioners as moderating variables. Quality—Access to Success, 25(198), 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, N., & Soewarno, N. (2025a). Corporate culture and managers fraud tendency perception: Testing of Fraud Hexagon theory. Cogent Social Sciences, 11(1), 2434953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, N., & Soewarno, N. (2025b). The examination of asset misappropriations in managers’ workplaces using hexagon’s fraud and the moderating impact of perceived strength of internal control. Journal of Financial Crime, 32(4), 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struckell, E. M., Patel, P. C., Ojha, D., & Oghazi, P. (2022). Financial literacy and self employment–The moderating effect of gender and race. Journal of Business Research, 139, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudrajat, S., Suryadnyana, N. A., & Supriadi, T. (2023). Fraud hexagon: Detection of fraud of financial report in state-owned enterprises in Indonesia. Jurnal Tata Kelola Dan Akuntabilitas Keuangan Negara, 9(1), 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. J., & Efron, B. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability, 57(1), 1–436. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20170808144050id_/http://cindy.informatik.uni-bremen.de/cosy/teaching/CM_2011/Eval3/pe_efron_93.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Viana, D. B. C., Jr., Lourenço, I., & Black, E. L. (2022). Financial distress, earnings management and big 4 auditors in emerging markets. Accounting Research Journal, 35(5), 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousinas, G. L. (2019). Advancing theory of fraud: The S.C.O.R.E. model. Journal of Financial Crime, 26(1), 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningtyas, E. T., & Aisyaturrahmi, A. (2022). The incidence of accounting fraud is increasing: Is it a matter of the gender of chief financial officers? Journal of Financial Crime, 29(4), 1420–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lin, Y., Fu, X., & Chen, S. (2023). Institutional ownership heterogeneity and ESG performance: Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 51, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D. T., & Hermanson, D. R. (2004). The fraud diamond: Considering the four elements of fraud. CPA Journal, 74(12), 38–42. Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2546&context=facpubs (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Wulandari, R., & Maulana, A. (2022). Institutional ownership as moderation variable of fraud triangle on fraudulent financial statement. Jurnal ASET (Akuntansi Riset), 14(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D., Jiao, H., & Buckland, R. (2017). The determinants of financial fraud in Chinese firms: Does corporate governance as an institutional innovation matter? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaumil, I., & Thaifur, M. (2025). Exploratory study of factors influencing fraud in the national health service in Buton Islands from a hexagon model perspective. Healthcare in Low Resource Settings, 13(1), 12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zin, S. F. B. M., Marzuki, M. M., & Abdulatiff, N. K. H. (2020). The likelihood of fraudulent financial reporting: The new implementation of Malaysian code of corporate governance (MCCG) 2017. International Journal of Financial Research, 11(3), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).