Abstract

The corporate finance field is inherently engaging, with a strong focus on factors influencing various performance indicators. This study analyzes 66 companies from the Information and Technology sector, all part of the Standard and Poor’s 500 index, over a 22-year period from 2003 to 2024. I applied linear, nonlinear, and interaction-variable models to identify the causal relationship between profitability and key influencing factors. The results reveal that firm size, sales growth rate, current ratio, long-term debt to total capital, free cash flow, asset turnover, receivable turnover, number of board meetings, percentage of women on the board, CEO age, audit committee independence, the presence of compensation and nomination committees, and a pandemic dummy variable all had positive effects on performance. In contrast, firm age, dividend payout ratio, effective tax rate, board size, CEO duality, and the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee negatively impacted firm performance. This research also explores corporate governance by evaluating the role of regulations and internal policies designed to promote financial transparency and protect shareholders’ interests. Additionally, it highlights the importance of board independence, the effectiveness of specialized committees, and the role of ethical leadership in driving long-term corporate success.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context and Theoretical Underpinnings

The topic of profitability has ignited intense debates among businesses and stakeholders. Scholars in corporate finance have begun investigating the variables influencing profitability metric.

This paper is motivated by the need to identify the most relevant indicators influencing firm performance, a topic that has become increasingly important in corporate finance due to its direct impact on decision-making. The study examines 66 companies within the IT sector of the S&P 500 index, covering the period from 2003 to 2024, for several reasons. First, the IT sector was selected because these companies are not only globally influential but also experienced notable changes during the pandemic, many of which had a positive impact on their performance. The rapid adoption of technology and the sector’s continuous evolution make it critical to understand the factors driving profitability in these firms. Second, the S&P 500 index was chosen as it represents a substantial portion of the American market, making it a relevant benchmark for assessing firm performance. Companies within this index are typically well-developed and transparent, providing a robust environment for examining the role of corporate governance. Third, this study is motivated by the importance of corporate governance in shaping firm performance. The American market places a strong emphasis on governance principles, such as the independence of the board of directors, the presence of consultative committees, and the characteristics of CEOs. By including these governance variables, the study aims to shed light on how they influence profitability and overall firm performance.

1.2. Research Gap

Existing research on corporate governance and firm performance has predominantly relied on linear regression frameworks, with limited attention given to nonlinear specifications or interaction effects. This study seeks to bridge this gap by employing advanced econometric models to examine United States IT firms listed in the S&P 500 over the period 2003–2024, thereby offering a more comprehensive and methodologically robust understanding of governance–performance dynamics.

1.3. Study Objective and Research Question

The research question of this study reflects how board and CEO characteristics and variables regarding consultative committee impact the profitability of American IT companies within the S&P 500 index. The topic is highly relevant in today’s business environment, where companies are eager to understand the internal and external factors affecting their performance and to develop strategies to mitigate negative impacts. The findings of this research are particularly valuable for stakeholders of these companies, offering a deeper understanding of long-term trends. These insights enable stakeholders to make more informed decisions about future strategies and actions.

1.4. Contribution Overview and Study Design

This paper’s novelty is grounded in several key aspects. Firstly, it lies in the fact that it used a long period of time for database construction, specifically 22 years. This broad time span allows for the collection of relevant findings, with the paper’s dataset acting as a comprehensive source. Secondly, another element of novelty is that I used nonlinear regression models. Including nonlinear regression models in this study is crucial because they allow for a more nuanced analysis of the relationships between variables that may not follow a linear pattern. In many real-world scenarios, the effects of certain factors on firm performance are complex and may involve interactions that are not adequately captured by linear models. Nonlinear regression models can reveal these intricate relationships and provide a more accurate representation of how various factors impact profitability. This approach enhances the robustness of the study’s findings and offers deeper insights into the dynamics affecting firm performance, leading to more effective and informed decision-making. Thirdly, I incorporated a dummy variable representing the pandemic crisis to examine its impact on firm performance. By including the COVID-19 dummy variable, I aimed to capture not only the financial disruptions generated by the pandemic but also its broader impact on corporate governance mechanisms and decision-making dynamics. The pandemic created an unprecedented environment characterized by uncertainty, operational constraints, and strategic pressure, which directly influenced the behavior and effectiveness of governance structures. Specifically, during this period, boards of directors faced challenges such as remote coordination, increased risk management responsibilities, and the need for accelerated decision-making. Therefore, by developing regression models that incorporate interaction terms based on the COVID-19 dummy variable, the analysis allows for a more nuanced understanding of how the pandemic moderated the relationships between governance indicators (such as board size, meeting frequency, or CEO duality) and firm performance. This approach not only enhances the explanatory power and robustness of the models but also provides valuable insights into how governance practices respond to external shocks. Consequently, the inclusion of this variable strengthens the study’s contribution by linking governance effectiveness to firm resilience under crisis conditions, offering practical implications for policymakers and corporate leaders in managing future systemic disruptions.

Furthermore, this study holds global significance because it explores how different corporate governance factors affect the profitability of the analyzed companies. Such insights can enhance transparency and ethical practices in business management, draw interest from international institutional investors, foster a level playing field, and strengthen ties with global stakeholders. Therefore, effective corporate governance is essential for the sustained growth and profitability of businesses in the context of a globalized economy. This fact is also indicated in the works of Puni and Anlesinya (2020), Naseem and Lin (2020), and Dakhlallh et al. (2020).

This document is organized into several key sections: it begins with an overview of the research topic, followed by a review of prominent scholars and their contributions. The third section outlines the research hypothesis and theoretical framework, while the fourth details the methodology, including data sources and econometric techniques. The fifth section presents the research findings, which are then discussed in the sixth section. The paper concludes with a summary of the main insights and their implications for both academic and practical contexts in the seventh section.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Board Leadership and Governance Practices

Numerous indicators related to corporate governance have been extensively explored within the specialized literature, demonstrating their discernible influence on a company’s profitability. Among these metrics, board size stands out as a widely recognized variable in corporate governance. In their research, Rahman and Yilun (2021) specifically scrutinized this indicator, identifying a positive relationship with profitability; however, it is noteworthy that this association did not reach statistical significance. In contrast to the assertions of previous researchers, Mohan and Chandramohan (2018) reached the conclusion that there exists a negative relationship between board size and firm profitability. The mixed evidence regarding the relationship between board size and firm profitability can be further understood through the lens of established theories such as agency theory, Jensen and Meckling (1976), which suggests that larger boards may exacerbate coordination problems and agency conflicts; the resource-based view, Barney (1991), which highlights the potential advantages of diverse expertise within larger boards, and stewardship theory, Davis et al. (1997), which assumes that directors act as committed stewards, fostering better firm performance.

Another indicator related to corporate governance is the number of board meetings. Thus, Puni and Anlesinya (2020) studied 38 companies listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange during the period 2006–2018 using panel regression. They observed a positive relationship between the frequency of board meetings and profitability. Consequently, a higher number of meetings is associated with improved financial performance, as the directors serving on the board demonstrate an interest in the positive advancement of the company. Contrary to previous results, Temprano and Gaite (2020) studied nonfinancial companies in Spain from 2005 to 2015 and found a negative relationship between this independent variable and profitability, motivating the idea that too many meetings can lead to lower performance because those meetings do not effectively cover the topics of discussion and may require additional meetings.

The percentage of women on the board of directors is another indicator studied in the academic literature. Yurtoglu and Ararat (2021) examined this variable in the case of 20 Turkish companies for the time period 2011–2018. They found a positive relationship between a company’s performance indicators and this independent variable, supporting the idea that gender diversity can lead to high financial performance. This is attributed to the observation that women are generally risk averse, potentially contributing to more carefully managed decisions at the level of a company’s board of directors. Similarly, Bennouri et al. (2018) studied 394 French companies over the period 2001–2010 and obtained the same result. This finding aligns with the resource-based view, which suggests that gender diversity represents a valuable organizational resource that enhances decision-making quality and contributes to superior firm performance, according to Barney (1991).

2.2. Leadership Traits of Chief Executives

CEO duality, serving as another independent variable under scrutiny in this analysis, has garnered attention from researchers such as Pucheta Martínez and Álvarez (2020). These authors, who delved into various variables, including board size and the percentage of women on the board, also addressed the intricacies of CEO duality. Surprisingly, they unearthed a positive relationship between CEO duality and these variables, contrary to their initial expectations. This finding suggests that if the CEO simultaneously holds the position of the chairperson of the board of directors, this leads to an increase in profitability. In contrast, researchers such as Puni and Anlesinya (2020) and Rashid (2017) arrived at a different conclusion, indicating a negative relationship between CEO duality and the aforementioned variables. It is essential to note, however, that this relationship lacked statistical significance in the study conducted by Puni and Anlesinya (2020). These mixed findings can be interpreted through agency and stewardship theories. While agency theory argues that combining the CEO and chairperson roles may weaken oversight and harm performance, according to Jensen and Meckling (1976), stewardship theory suggests that unified leadership can enhance coordination and strategic effectiveness, thereby improving profitability, according to Donaldson and Davis (1991).

The age of the CEO is another crucial variable in corporate governance. Researchers such as Belenzon et al. (2019), who examined several companies in Western Europe between 2002 and 2012, identified a negative relationship between the age of the CEO and firm performance. The authors recommended that companies consider bringing in new and younger executives with prospects for growth and development. Similarly, employing panel regression, Naseem and Lin (2020), who studied 179 firms in Pakistan from 2009 to 2015, also concluded that there is a negative relationship between these variables. Notably, these authors identified turning points on this indicator, finding that up to a certain age, the influence is positive; however, after that age, the influence of CEO age on profitability is negative. The mixed evidence regarding CEO age can be interpreted through stewardship theory and the resource-based view. While stewardship theory suggests that older CEOs contribute positively to firm performance through accumulated experience and strategic insight, according to Donaldson and Davis (1991), the resource-based view implies that beyond a certain threshold, aging leadership may limit innovation and adaptability, thereby reducing profitability, according to Barney (1991).

2.3. Management Committees Within the Governance Framework

Another important indicator is the independence of the audit committee. Thus, Dakhlallh et al. (2020) investigated 180 companies from the financial, industrial and service sectors listed on the Amman Stock Exchange over the period 2009–2017 utilizing panel regression. They identified a positive relationship between audit committee independence and financial performance. Additionally, Alqatamin (2018) studied 165 nonfinancial companies listed on the Amman Stock Exchange, similar to the approach taken by Dakhlallh et al. (2020), although the time span was between 2014 and 2016. Alqatamin (2018) reached a similar conclusion to that obtained by the authors Dakhlallh et al. (2020).

Another important corporate governance variable is the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee. Researchers Kuzey et al. (2021) have analyzed three crucial sectors, namely, tourism, health and finance, using data obtained from the Thomson Reuters platform over the time interval 2011–2018. By scrutinizing the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee, they concluded that its existence negatively influences firm performance. This conclusion was supported by the notion of the high costs associated with corporate social responsibility. In contrast, Yu and Guo (2022) investigated this variable in detail using a broader econometric methodology, and the examined companies are included in the S&P 500 stock market index for the period 2005–2013. They found a positive relationship between CSR committee presence and firm performance.

In the academic literature, there are also papers concerning the presence of compensation committees in companies. Thus, Harymawan et al. (2020) analyzed a database with 847 observations of Indonesian firms during the period 2007–2017 and concluded that there is a positive relationship between the presence of a compensation committee and profitability. The research methodology used by these researchers was panel regression, which is a fairly common approach. A similar perspective is offered by Mintah (2016), who studied 63 financial companies in Great Britain over a period of 12 years using the same research methodology as Harymawan et al. (2020).

Another important committee at the company level is the nominating committee, which has the main objective of appointing the directors in the company and identifying the right individuals to fill management positions. Researchers Zraiq and Fadzil (2018) also considered this type of committee, in addition to the compensation committee, and found a positive relationship between the presence of the nominating committee and financial performance. Additionally, Peter (2015), who analyzed 63 financial firms in Great Britain over 12 years, obtained the same result as the authors Zraiq and Fadzil (2018).

2.4. Firm Oversight and Strategic Decisions During the Pandemic

In the end, it is imperative to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most recent crisis in recent years. Employing panel regression, Shen et al. (2020) investigated companies in the Chinese market during the pandemic crisis and identified a negative impact on the performance of Chinese companies. Similarly, Hu and Zhang (2021) analyzed companies across different global markets during the pandemic crisis, supporting the findings of the study by Shen et al. (2020). In contrast to the results obtained by the aforementioned authors, Rim et al. (2022) examined 3961 global IT companies for the year 2022 and discovered that this crisis nonetheless resulted in enhanced performance for these companies. This development in the IT sector can be attributed to the high demand for technological products and services, which are essential for individuals to conduct various activities during periods of isolation. Therefore, the pandemic crisis has impacted numerous economic and financial indicators, with the effects on the independent variables considered for analysis subject to changes influenced by the crisis period.

2.5. Gaps in the Existing Literature

The review of existing literature reveals that most studies have employed linear regression models with panel data, while the use of nonlinear regression models and models that contain interaction variables remains relatively scarce. Thus, there is a noticeable absence of studies using nonlinear regression models and models that contains interaction variables to explore other governance indicators like audit committee independence, the presence of various governance committees, and remuneration and nomination committees. This study aims to fill this gap by applying this methodology to these underexplored variables.

Additionally, existing research predominantly focuses on companies in Asia (e.g., India, Vietnam, Nigeria, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, China) and Europe (e.g., Spain, Portugal, France, Greece, Croatia). There is a lack of studies concentrating on IT companies within the S&P 500 index in the United States. While this represents primarily an empirical and contextual gap rather than a theoretical one, this research contributes to the literature by addressing this void through a unique dataset of U.S. IT firms in the S&P 500. Furthermore, the analysis is conceptually grounded in agency theory and stakeholder theory, which together provide a robust framework for understanding how governance mechanisms influence firm performance and how the interests of both shareholders and broader stakeholders are balanced within large, complex organizations.

Moreover, while some studies have analyzed relatively short periods, others have extended their time frames. This study will leverage a comprehensive period from 2003 to 2024 to provide a more robust analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the Database and Variables

The present study focuses on a detailed analysis of the 66 companies in the IT sector integrated into the S&P 500 stock market index. In terms of the time interval, the analysis covers the period from 2003 to 2024, providing a sufficiently long timeframe for relevant econometric analyses in the specified sector. All financial data for the variables analyzed in the article were sourced from the Thomson Reuters Eikon platform. It is important to note that I obtained an unbalanced panel database because data for some indicators were not available for certain years.

The choice to focus on the IT sector for this analysis is based on its continuous expansion and growing importance in the aftermath of the health crisis, highlighting its essential role in everyday life worldwide. The extensive reliance on IT resources emphasizes the sector’s current relevance, warranting an in-depth examination of new financial trends and the effects of recent crises on these trends. This paper seeks to reveal these dynamics by thoroughly analyzing and interpreting the financial and governance metrics of firms within the IT sector.

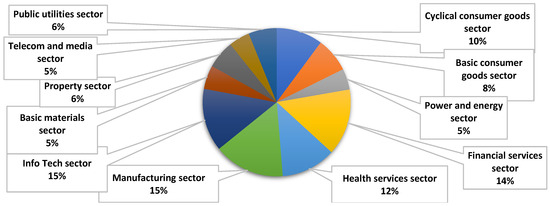

Figure 1 shows that the Information Technology sector represents one of the largest components of the S&P 500 index. Together with the industrial, financial, and healthcare sectors, it constitutes a key pillar of the United States economy.

Figure 1.

Sector Composition of the S&P 500. Source: Authors’ work.

Therefore, the distinct position of the IT sector within the other industries of the index becomes evident, which further enhances the relevance of this study, especially in light of the recent health crisis.

Table 1 presents the variables used in the analysis, along with the symbols used in this paper and the economic explanation of each, providing a clearer outline of the independent variables to be analyzed in this paper.

Table 1.

Variable Presentation.

The formulas specified in Table 1 are consistent with those of several books in the field; they are specialized books, such as those written by Anghelache (2009) and Stancu and Stancu (2012). Moreover, these variables were also used in Danilov’s (2024) study; however, the present work represents an enhanced and more refined version of that research.

The hypotheses for this research are formulated based on the theoretical framework and empirical evidence identified in the existing literature, and are outlined as follows:

H1.

The attributes of the board, including its size and frequency of meetings, have a positive effect on profitability.

H2.

The proportion of women on the board of directors enhances profitability.

H3.

The presence of specific board committees—such as an independent audit committee, a corporate social responsibility committee, and committees for compensation and nominations—has a positive impact on profitability.

H4.

Certain CEO characteristics, including CEO duality and age, have a negative effect on profitability.

3.2. Description of Econometric Methods

The description of the econometric methods used in this paper is primarily based on the econometric analysis conducted in the Stata 15 program. The database was imported into the Stata program, and descriptive statistics, along with the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix, were calculated.

The research methodology employed in this quantitative study comprises several elements. Initially, baseline regression models were constructed without effects to yield specific results. Subsequently, linear regression models with both fixed effects and random effects were executed. The determination of a suitable model for the study was based on the Hausman test. With a significance threshold of 5% set for the Hausman test, models exceeding this threshold were considered random effects models, while models below this threshold were regarded as fixed effects regression models. Furthermore, regression models with interaction variables, formed based on the dummy independent variable COVID-19, were developed to observe the impact of the pandemic crisis on the various indicators recorded by the analyzed companies. Additionally, for regression models utilizing the previously specified interaction variable, a fixed effects model was tested. Subsequently, the random effects model and the Hausman test were performed to ascertain the appropriate regression model. Moreover, the creation of nonlinear regression models through the product of the same two independent variables was also considered. The same research methodology mentioned previously was also applied to nonlinear regression models.

Considering the general form of the regression models, a synthetic presentation follows. For linear regression models, Equation (1) is considered:

Firm performanceit = a0 + a1Financial variables + a2Governance variables + a3COVIDit + εit

The general forms of nonlinear regression models are shown in Equation (2):

Firm performanceit = a0 + a1Financial variables + a2Financial variables2 + a3Governance variables + a4Governance variables2 + a5COVIDit + εit

The general form of regression models with an interaction variable is shown in Equation (3):

where a0 = constant; a1 … a20 = coefficients associated with the independent variables; ε = errors; firm performance = [ROE, ROA, ROIC, NM]; financial variables/control variables = [FS, FA, SRGR, DPR, ETR, CR, LTDTC, FCF, AT, RT]; governance variables = [BS, NBM, WB, CEO_D, CEO_A, ICA, C_CSR, C_C, C_N]; i = [1,66]; t = [2003, 2024].

Firm performanceit = a0 + a1Financial variables + a2Financial variables × COVIDit + a3Governance variables + a4Governance variables × COVIDit + a5COVIDit + εit

Therefore, considering the extensive research methodology, extended tables presenting the obtained results can be found in the appendices. The next chapter is dedicated to the interpretation and detailed commenting of the econometric results obtained and their correlation with the economic environment.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The descriptive statistics of the database are presented in Table 2. Table 2 belongs to Danilov (2024), and the present study will develop the research methodology based on Danilov’s (2024) work. A 95% winsorization was applied to the variables ROA, ROE, ROIC, NM, FS, FA, GW, SRGR, DPR, ETR, AT and LTDTC to reduce the impact of outliers and improve the robustness of the results. Additionally, variables such as FS, SRGW, and FCF were standardized using logarithmic transformation. Considering the average and standard deviation, variables with a standard deviation above the average are quite volatile, while variables with a standard deviation below the average do not exhibit a high degree of volatility. From the perspective of the established database, variables such as long-term debt to total capital and receivable turnover have a standard deviation greater than the average, indicating that these indicators are volatile. Additionally, minimum and maximum values of the variables used in this paper are provided.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

A specific indicator in descriptive analysis, namely, skewness, reflects the level of symmetry of a distribution relative to a certain indicator. In the analyzed database, indicators such as the dividend payout ratio, effective tax rate, long-term debt to total capital, receivable turnover, independence of the audit committee, and presence of the compensation committee have skewness values significantly different from 0, suggesting highly skewed distributions. Furthermore, indicators such as return on equity, return on assets, return on invested capital, net margin, firm size, effective tax rate, free cash flow, CEO duality, CEO age, independence of the audit committee, presence of the corporate social responsibility committee, presence of the compensation committee and nomination committee have negative skewness, indicating highly left-skewed distributions. On the other hand, the rest of the indicators have positive skewness but are different from 0, indicating right-skewed distributions.

The kurtosis indicator represents the degree to which the distribution of the investigated indicators flattens. For indicators such as CEO duality, the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee, board size, the percentage of women on the board and CEO age, this indicator is lower than 3, suggesting that the distributions of these indicators are platykurtic. For other indicators, the kurtosis is greater than 3, indicating that the distributions related to those indicators are leptokurtic, with an excess skew greater than 0.

An important element in database analysis is the correlation between the variables used. Table 3 displays the matrix of correlation coefficients. Table 3 belongs to Danilov (2024), and the present study will develop the research methodology based on Danilov’s (2024) work.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

In this study, a correlation greater than 0.7 was considered to indicate a strong positive relationship, while a correlation of −0.7 was interpreted as a strong negative relationship. This analysis revealed a robust positive correlation of 0.700 between long-term debt to total capital and return on equity. Additionally, a substantial positive correlation of 0.723 was identified between free cash flow and firm size. Consequently, when constructing models with return on equity as the dependent variable, I opted not to include long-term debt to total capital due to the strong correlation between these two indicators. Similarly, in models involving firm size, I excluded the free cash flow indicator to address the observed strong correlation. Consequently, distinct regressions were conducted, featuring the abovementioned indicators separately. This approach was employed to effectively mitigate issues of collinearity between the variables.

4.2. Results of the Regression Models

The results of the regression models are interesting considering the multitude of indicators analyzed. Therefore, most interpretations and comments will be based on the regression models in the appendices of this paper. Thus, first, I used regression models without effects; then, I used fixed–effects regression models and random–effects regression models. Additionally, I performed the Hausman test, which determined that the models with dependent variables ROE and ROA would be regression models with fixed effects, while the models with dependent variables ROIC and NM would be models with random effects. The choice between fixed effects and random effects models was determined based on the Hausman test, using a 5% significance level as the decision threshold. Specifically, when the p-value of the Hausman test was below 0.05, the null hypothesis, that the random effects estimator is consistent, was rejected, and the fixed effects model was selected as the more appropriate specification. Conversely, when the p-value exceeded 0.05, the random effects model was retained, indicating that individual-specific effects were uncorrelated with the explanatory variables. This approach ensured that model selection was guided by statistical evidence and methodological rigor. The aforementioned models are regression models that do not have interaction variables and are not nonlinear regression models. Thus, regression models that present an interaction variable and nonlinear models were treated immediately using the same research methodology. Since the VIF test confirmed the absence of multicollinearity issues, the analysis proceeds by directly reporting the results obtained from the fixed-effects and random-effects models.

Table 4 shows the linear regression models with effects obtained following the implementation of the quantitative research methodology in the Stata program. It should be mentioned that in Table 4, some of the regression models run are presented. Note that fe represents a regression model with fixed effects and re represents a regression model with random effects in this study.

Table 4.

Linear regression models with fixed and random effects.

Also, Table 4 is taken from Danilov (2024), whose work serves as the foundation for the research methodology. The present study significantly improves and expands upon Danilov’s (2024) methodological framework.

The R2 values reported across the models indicate relatively low to moderate explanatory power, suggesting that while the selected variables contribute to explaining variations in firm profitability, other unobserved factors may also play a role. The F-statistics and their corresponding p-values (Prob > F = 0.0000) confirm the overall statistical significance of the regression models, implying that the explanatory variables jointly have a significant effect on the dependent variables. Although some models show lower R2 values, this is common in studies involving firm-level panel data, where profitability is influenced by a wide range of external and firm-specific determinants. The estimated values of R2 within, between, and overall indicate that most of the variation in firm profitability is explained by within-firm differences over time rather than between-firm variations, suggesting that company-specific factors and temporal dynamics play a more significant role in determining performance, both in the fixed and random effects regression models.

In Table 5, the regression models with interaction variables are presented. In Table 5, a substantial improvement can be observed for the purposes of the present study.

Table 5.

Regression models with interaction variables.

From the perspective of Table 5, several interaction variables can be observed based on the dummy variable that captures the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Moreover, Table 6 highlights several nonlinear regression models.

Table 6.

Nonlinear regression models for ROE and ROA.

Table 6 presents nonlinear regression models based on the formation of turning points, with the dependent variables being ROE and ROA. The nonlinear regression models obtained are presented in Table 7, with ROIC and NM as dependent variables.

Table 7.

Nonlinear Regression Models for ROIC and NM.

Therefore, in the following, I will comment on each independent variable, from the point of view of all the results obtained, considering the linear and nonlinear regression models, as well as those with the interaction variable.

4.3. Robustness Checks

To ensure the reliability and robustness of the empirical analysis, a comprehensive set of diagnostic procedures was performed. The Pesaran CD test was applied to all regression models estimated in this study, including both the linear fixed and random effects specifications and those incorporating interaction or nonlinear terms. The purpose of this test was to identify potential cross-sectional dependence among firms, which may arise from common market shocks, macroeconomic influences, or unobserved industry-specific factors.

The results of the Pesaran CD test consistently rejected the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence, indicating significant correlation across the residuals of individual cross-sectional units. This finding suggested that the standard fixed-effects and random-effects estimators could produce biased or inefficient standard errors if cross-sectional dependence is ignored.

To address this issue, all models were subsequently re-estimated using Driscoll–Kraay standard errors, which are robust to heteroscedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence. The re-estimated coefficients maintained similar magnitude, sign, and level of statistical significance, confirming the robustness and consistency of the empirical results across all specifications.

Altogether, the combined use of diagnostic tests, robust estimators, and coefficient stability checks increases the reliability of the econometric results and ensures the robustness of the study’s conclusions. All corresponding outputs can be found in the appendix, in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 from Appendix A.

5. Discussion

In terms of corporate governance variables, I considered the characteristics of the board of directors and board size. According to regression models incorporating interaction variables, during the years marked by the pandemic crisis, the influence of board size was negative on economic profitability and the net margin. An increase of 1% in the board size leads to a rise in ROE by 0.08%, but a decrease in ROA by 0.02%, in ROIC by 0.06%, and in NM by 0.01%. This effect was statistically significant, in contrast to other regression models where the influence was statistically insignificant. Nonlinear models using the net margin as a dependent variable revealed turning points. Up to a level of 10.772988, the influence of board size on the net margin is negative; beyond this point, the influence becomes positive. These results suggest that companies with excessively large boards tend to experience a detrimental effect on profitability, contrary to the Hypothesis 1 of this study, as also noted by Mohan and Chandramohan (2018). These results highlight that, from an economic standpoint, larger boards may have become less efficient in times of crisis due to increased coordination complexity and slower managerial responses, thereby diminishing their positive contribution to firm performance.

Another variable related to the characteristics of the boards is the number of annual meetings attended by board members. From the perspective of regression models, which also incorporate interaction variables, it was found that the number of annual meetings held by the board had a negative influence on financial and economic profitability, as well as on the net margin, during the years when the crisis manifested. In contrast, compared to the years without a crisis, the influence was positive in those years. In the case of the number of board meetings, a 1% increase in this indicator results in an increase in ROA, ROE, and NM by 0.04%, but a decrease in ROIC by 0.02% Therefore, the present study validates the Hypothesis 1 by referring to linear regression models with effects, demonstrating that the number of meetings held by board members positively influences firm performance, as also shown by Puni and Anlesinya (2020). Economically, the findings indicate that while an increased number of board meetings during the crisis years may have signaled managerial pressures and operational challenges that constrained profitability, in non-crisis periods such meetings strengthen governance oversight and contribute positively to firm performance.

From the perspective of the presence of women on the board, in terms of the regression models with interaction variables, it was found that in the years when the pandemic crisis manifested itself, the percentage of women on the board positively affected the return on invested capital. Regarding women on the board, a 1% increase in this indicator decreases ROA and ROE by 0.02% but increases ROIC by 0.02%. This is attributed to the fact that women often exhibit greater aversion to risk than men, bringing new prospects for company development, especially in times of crisis. Additionally, linear regression models with effects confirmed these findings, with the influence being both statistically significant and positive. Therefore, these results align with the Hypothesis 2 of this paper, a conclusion also supported by Yurtoglu and Ararat (2021) and Bennouri et al. (2018).

CEO duality is an important indicator, and the results indicate that the influence is negative and statistically significant in the case of regression models without effects that include return on assets and return on invested capital as dependent variables. This result is also maintained in the case of regression models with effects. An increase of 1% in CEO duality leads to a reduction of approximately 1% in all profitability indicators. Therefore, in companies where the CEO is also the chairperson of the board of directors, this situation will negatively affect the financial performance indicators, a finding supported by Puni and Anlesinya (2020) and Rashid (2017). Thus, Hypothesis 4 of this paper is validated. Overall, the results underline that excessive concentration of decision-making authority within one individual undermines the effectiveness of corporate governance, thereby constraining firms’ ability to achieve optimal financial outcomes.

Regarding CEO age, it was found that, in the case of regression models without effects, this variable positively influences all rates of return but only return on assets is statistically significantly influenced. An increase of 1% in CEO age results in a decrease in ROE by 0.21%, but an increase in the other profitability indicators by around 0.05%. From the perspective of regression models with effects, a positive influence of CEO age on financial performance was also found, an indicator that is statistically significant for a 1% threshold in its relationship with economic profitability. These results indicate that, despite contradicting the stated hypothesis, the positive association between CEO age and profitability may reflect the value of accumulated expertise, leadership maturity, and prudent risk management practices that typically accompany longer professional experience. This result is not consistent with Hypothesis 4. The positive association between CEO age and firm performance may be explained by the greater managerial experience, strategic maturity, and risk-awareness that often characterize older executives. Such attributes can lead to more prudent decision-making and long-term stability, which may outweigh the innovative advantages typically associated with younger leaders.

The independence of the audit committee exerts a positive and statistically significant influence on the net margin in both models, with and without effects. An increase of 1% in audit committee independence causes a 0.02% decrease in ROE, but an increase of 0.01% in the other performance indicators. Consequently, increased independence within the audit committee and a greater proportion of independent members correlated with a more substantial improvement in company profitability. These findings substantiate the research Hypothesis 3, a conclusion also supported by existing scholarly works, including Dakhlallh et al. (2020) and Alqatamin (2018).

From the perspective of the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee, the results show that, in the case of models without effects, this indicator negatively influences the return on invested capital and the net margin. Regarding the CSR committee, a 1% increase in its presence leads to a 0.4% increase in ROE, while decreasing the other performance indicators by 0.01%. The influence of these variables on financial returns and economic returns is positive but not statistically significant. Therefore, it can be inferred that the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee may lead to a decrease in profitability because, for a firm to carry out certain corporate social responsibility programs, these activities involve costs that reduce the company’s profit. These results do not validate the Hypothesis 3 of this study; a conclusion was also reached by Kuzey et al. (2021). The negative relationship between the presence of a corporate social responsibility (CSR) committee and profitability may be attributed to the additional financial and operational costs involved in implementing CSR initiatives. While such committees enhance a company’s social and ethical profile and strengthen stakeholder trust over the long term, the short-term impact often translates into reduced profitability due to higher expenditures and resource allocations toward sustainability programs. This result suggests that firms may face a trade-off between social responsibility objectives and immediate financial performance, emphasizing the need for a balanced strategy that integrates CSR activities with long-term value creation.

Another important variable is the presence of the compensation committee. Thus, concerning the regression models without effects, this variable was found to positively influence firm performance, but the influence was not statistically significant. From the perspective of regression models with effects, this variable positively influences the rates of return but significantly impacts the return on equity. Considering these results, the presence of a compensation committee has a positive effect on firm performance, aligning with the hypotheses 3 of this study. Several researchers have obtained similar results, namely, Harymawan et al. (2020) and Mintah (2016). From an economic standpoint, the presence of a compensation committee supports better alignment between executive pay and profitability.

The nomination committee is another common committee. Thus, it was found that within the models without effects, this indicator has a positive and statistically significant impact on financial returns. According to the regression models with effects, the independent variable no longer has a statistically significant influence on return on equity but has a significant impact on return on assets, and the influence is also positive. An increase of 1% in the remuneration and nomination committees results in an improvement in performance indicators by approximately 0.05%. These results validate Hypothesis 3 of the study, and similar findings have been reported by other researchers Zraiq and Fadzil (2018) and Peter (2015). Overall, these results emphasize the economic importance of structured and transparent board nomination processes, as they contribute to a more competent and balanced leadership team, ultimately enhancing firms’ profitability and long-term performance.

The final variable examined in this study pertains to the dummy variable, which is designed to capture the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. The results indicate that, both in the case of regression models without effects and those with effects, the dummy variable significantly and positively influenced return on equity at a threshold of 1%. Thus, the pandemic crisis appears to have had a positive impact on the profitability of IT companies. These findings align with those of other scholars, as exemplified by Rim et al. (2022). In light of these results, it can be asserted that IT companies were relatively unaffected by the pandemic crisis compared to companies in diverse industries. This resilience could be attributed to increased reliance on technological resources and products by the general population during the crisis.

In summary, the results provide partial empirical support for the proposed hypotheses. Regarding board characteristics, the influence of board size was found to be negative and statistically significant, thereby not supporting Hypothesis 1, while the number of board meetings showed a positive effect on firm profitability, confirming this hypothesis. The findings related to women on the board validate Hypothesis 2, suggesting that gender diversity contributes positively to governance effectiveness and firm performance. Concerning governance committees, the study provides support for Hypothesis 3 in the cases of the audit, compensation, and nomination committees, while the CSR committee exhibited an inverse or statistically insignificant effect, contradicting the initial assumption. Finally, in the context of CEO characteristics, CEO duality negatively affects profitability, confirming Hypothesis 4, whereas CEO age demonstrates an opposite trend, indicating that accumulated experience may enhance performance, thus not supporting the same hypothesis. Overall, these findings highlight the multifaceted and context-dependent nature of corporate governance mechanisms, emphasizing that their effects on firm performance are influenced by both internal organizational dynamics and external conditions such as the pandemic crisis.

The findings of this study are broadly consistent with the main body of literature on corporate governance and firm performance, while also revealing some distinctive patterns specific to the IT sector. The positive effects identified for variables such as board meetings, gender diversity, and governance committees (audit, nomination, and compensation) are in line with previous research, including the studies of Puni and Anlesinya (2020), Yurtoglu and Ararat (2021), and Zraiq and Fadzil (2018), which emphasized the contribution of effective governance mechanisms to improved profitability. Conversely, the negative relationship observed for CEO duality and the mixed results regarding board size and CSR committees reflect findings reported by Mohan and Chandramohan (2018) and Kuzey et al. (2021), suggesting that certain governance features may generate adverse effects under specific contextual or crisis conditions. Overall, these results enrich the existing empirical evidence by confirming, refining, and, in some cases, challenging established theoretical assumptions within the field of corporate governance.

6. Conclusions

In the framework of this quantitative research, I investigated the most important variables that have an effect on the profitability of companies in the information and technology sector, integrated into the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock market index. Therefore, this paper focused on 66 enterprises, and the period of time covered was 2003–2024. The primary objective of this study was to establish the relationship between the main independent variables analyzed in the academic literature and firm performance. To achieve this goal, an elaborate methodology incorporating linear and nonlinear regression models, along with models featuring interaction variables formed based on a dummy variable capturing the COVID-19 crisis, was employed. Given the progressive development of companies in the technology field and the growing interest among investors in monitoring their evolution, this type of study becomes imperative for a broad spectrum of stakeholders. Furthermore, the findings reveal that investors hold optimistic expectations regarding the future profitability of these companies, underscoring their keen interest in the trajectory of firms within the IT sector.

Summarizing the results obtained during this study, it was found that indicators such as firm size, sales revenue growth rate, current ratio, long-term debt to total capital, free cash flow, asset turnover, receivable turnover, number of board meetings, percentage of women on board, CEO’s age, independence of the audit committee, presence of the compensation committee, presence of the nomination committee, and the dummy variable that captures the COVID-19 crisis have a positive impact on firm performance. Furthermore, variables such as firm age, dividend payout ratio, effective tax rate, board size, CEO duality, and the presence of a corporate social responsibility committee have negative impacts on firm performance. Regarding the COVID-19 crisis, variables such as the dividend payout ratio, effective tax rate, current ratio, long-term debt to total capital, free cash flow, asset turnover, receivable turnover, board size, and number of board meetings are influenced by the presence of this crisis. In some cases, these variables intensify the impact of the crisis on performance through higher coefficients associated with independent variables; in other cases, the impact is the opposite compared to the years in which the crisis did not occur. Additionally, the presence of turning points was found through the implementation of nonlinear regressions for the following variables: firm size, firm age, sales revenue growth rate, dividend payout ratio, long-term debt to total capital, asset turnover, receivable turnover, and board size. The complexity and, in some cases, the contradictory nature of the results can be attributed to the multidimensional effects of corporate governance mechanisms, which may interact differently depending on company size, market conditions, and managerial behavior. For instance, variables such as CSR commitment or CEO age reflect both strategic and behavioral dimensions that can produce diverse outcomes across firms and time periods.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study provide valuable guidance for managers, investors, and regulators. Managers are encouraged to enhance board independence, promote gender diversity, and ensure transparency in decision-making, as these practices strengthen corporate governance and support sustainable profitability. For investors, the governance indicators identified, such as board structure, committee composition, and leadership duality, can serve as useful benchmarks for evaluating firm quality, governance effectiveness, and long-term value potential. Regulators, in turn, may use these insights to refine corporate governance codes, encourage best practices across listed firms, and design policies that promote transparency, accountability, and board diversity. Overall, applying these findings can improve firm performance, boost investor confidence, and contribute to a more stable and efficient corporate environment.

Considering the limitations of this study, I focused on 20 independent variables influencing the profitability of 66 companies in the IT sector from the S&P 500; the time horizon analyzed was between 2003 and 2024. Thus, the results obtained in this quantitative research are relevant to the specified companies and the period analyzed, not for a longer period of time. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the potential data bias and the limited generalizability of the findings, as the results may not fully apply to companies outside the S&P 500 or to other sectors beyond the IT industry.

Exploring future directions for this research, one could explore the analysis of several independent variables at both the microeconomic and macroeconomic levels. At the microeconomic level, variables such as the CEO’s tenure and the proportion of institutional investors in the shareholding structure could be included. At the macroeconomic level, factors such as economic growth, the inflation rate and the interest rate, the unemployment rate, market cycles and the exchange rate could be considered. Additionally, the time horizon could be extended, and the research methodology could incorporate logit regression models or other pertinent regression models.

While this analysis is limited to IT firms in the United States, the underlying relationships between governance mechanisms and firm performance may also be applicable to other industries. Further studies could validate these results across diverse sectors and institutional environments to enhance their generalizability.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data were collected from the Refinitiv Eikon platform, https://eikon.refinitiv.com/. Accessed on 1 September 2025. The corresponding author may provide the datasets employed and/or examined in the current paper upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AT | Asset turnover |

| BS | Board size |

| CEO | Chief executive officer |

| CEO_A | Chief executive officer age |

| CEO_D | Chief executive officer duality |

| C_C | Presence of the committee compensation committee |

| C_N | Presence of the committee nomination committee |

| COVID | Covid |

| CR | Current ratio |

| C_CSR | Presence of the corporate social responsibility committee |

| DPR | Dividend payout ratio |

| ETR | Effective tax rate |

| FA | Firm age |

| FCF | Free cash flow |

| fe | regression models with fixed effects |

| FS | Firm size |

| GMM | Generalized method of moments |

| ICA | Independence of the audit committee |

| IT | Information and Technology |

| LTDTC | Long term debt to total capital |

| NBM | Number of board meetings |

| NM | Net Margin |

| ROA | Return on assets |

| re | Regression models with random effects |

| ROE | Return on equity |

| ROIC | Return on invested capital |

| RT | Receivable turnover |

| S&P 500 | Standard and Poor’s 500 |

| SRGR | Sales revenue growth rate |

| WB | The percentage of women on the board of directors |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Fixed and random regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors.

Table A1.

Fixed and random regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE fe | ROE fe | ROA fe | ROA fe | ROIC re | ROIC re | NM re | NM fe | |

| FS | 0.168 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.043 | 0.007 | ||||

| (−0.041) | (−0.004) | (−0.033) | (−0.006) | |||||

| FA | 0.013 | 0.014 | −0.003 * | −0.004 ** | 0 | 0 | 0.001 *** | 0.003 |

| (−0.019) | (−0.02) | (−0.002) | (−0.002) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (0) | (−0.004) | |

| SRGR | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.044 *** | 0.039 *** | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.001 | 0.028 * |

| (−0.078) | (−0.081) | (−0.009) | (−0.008) | (−0.014) | (−0.015) | (−0.002) | (−0.016) | |

| DPR | 0.018 | 0.017 | −0.007 ** | −0.004 * | −0.026 | −0.025 | −0.029 *** | −0.027 *** |

| (−0.022) | (−0.028) | (−0.003) | (−0.002) | (−0.026) | (−0.026) | (−0.005) | (−0.005) | |

| ETR | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0 | 0 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.002 ** | −0.003 ** |

| (−0.007) | (−0.006) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (−0.004) | (−0.004) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | |

| CR | 0.004 | −0.007 | 0.011 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.033 ** | 0.031 ** | 0.021 *** | 0.018 *** |

| (−0.016) | (−0.016) | (−0.002) | (−0.001) | (−0.016) | (−0.015) | (−0.003) | (−0.003) | |

| AT | 0.088 | 0.071 | 0.126 *** | 0.129 *** | 0.398 *** | 0.419 *** | −0.002 | 0.037 ** |

| (−0.076) | (−0.078) | (−0.008) | (−0.008) | (−0.085) | (−0.089) | (−0.012) | (−0.016) | |

| RT | −0.003 ** | −0.004 *** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 * | 0.012 *** | 0.012 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 ** |

| (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (−0.004) | (−0.004) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | |

| BS | 0 | 0.009 | –0.002 | –0.001 | –0.007 | –0.005 | –0.001 | –0.002 |

| (−0.012) | (−0.012) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | (−0.012) | (−0.012) | (−0.002) | (−0.003) | |

| NBM | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0 | 0 | –0.001 | –0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (−0.005) | (−0.005) | (0) | (0) | (−0.005) | (−0.005) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | |

| WB | −0.003 | −0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 * | 0.001 |

| (−0.002) | (−0.002) | (0) | (0) | (−0.002) | (−0.002) | (0) | (0) | |

| CEO_D | −0.058 | −0.040 | −0.014 *** | −0.010 ** | −0.109 ** | −0.110 ** | −0.011 | −0.013 |

| (−0.045) | (−0.046) | (−0.005) | (−0.004) | (−0.051) | (−0.052) | (−0.008) | (−0.009) | |

| CEO_A | −0.022 | −0.020 | 0.007 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.001 | −0.002 |

| (−0.018) | (−0.019) | (−0.002) | (−0.002) | (−0.006) | (−0.006) | (−0.001) | (−0.004) | |

| ICA | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** |

| (−0.004) | (−0.004) | (0) | (0) | (−0.006) | (−0.006) | (−0.001) | (−0.001) | |

| C_CSR | 0.041 | 0.053 | –0.001 | –0.001 | –0.067 | –.061 | –.001 | –.004 |

| (−0.043) | (−0.044) | (−0.005) | (−0.004) | (−0.054) | (−0.053) | (−0.008) | (−0.009) | |

| C_C | 0.239 ** | 0.224 ** | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.077 | 0.064 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| (−0.111) | (−0.113) | (−0.013) | (−0.013) | (−0.298) | (−0.301) | (−0.027) | (−0.027) | |

| C_N | 0.055 | 0.052 | 0.011 ** | 0.012 ** | 0.049 | 0.057 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| (−0.047) | (−0.048) | (−0.005) | (−0.005) | (−0.07) | (−0.071) | (−0.009) | (−0.01) | |

| COVID | 0.114 ** | 0.121 *** | −0.001 | −0.003 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| (−0.047) | (−0.048) | (−0.005) | (−0.005) | (−0.041) | (−0.041) | (−0.009) | (−0.01) | |

| FCF | 0.084 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.038 ** | 0.018 *** | ||||

| (−0.024) | (−0.002) | (−0.018) | (−0.005) | |||||

| LTDTC | 0 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.001 *** | 0.001 | ||

| (0) | (0) | (−0.005) | (−0.005) | (0) | (−0.001) | |||

| _cons | –3.111 *** | –1.214 * | −0.597 *** | −0.581 *** | –1.339 * | –1.245 * | 0.133 | −0.082 |

| (−0.902) | (−0.656) | (−0.099) | (−0.061) | (−0.779) | (−0.693) | (−0.122) | (−0.132) | |

| Observations | 818 | 799 | 698 | 681 | 355 | 349 | 718 | 701 |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.024 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.163 | 0.183 | 0.248 | 0.082 |

| Mean VIF | 1.33 | 1.29 | 1.4 | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.32 | 1.4 | 1.28 |

| F-stat (Driscoll-Kraay) | 3.421 | 3.005 | 34.112 | 35.021 | 8.443 | 7.791 | 7.902 | 8.015 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are reported in parentheses. Note: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. Source: Authors’ work.

Table A2.

Interaction variables regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors.

Table A2.

Interaction variables regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE re | ROE fe | ROA re | ROA fe | ROA fe | ROIC re | |

| FS | 0.05 ** | 0.013 *** | ||||

| (0.024) | (0.003) | |||||

| FA | 0 | 0.011 | 0 | −0.004 ** | −0.003 ** | 0 |

| (0.001) | (0.020) | (0) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| SRGR | −0.006 | 0.042 | 0 | 0.038 *** | 0.038 *** | −0.008 |

| (0.012) | (0.082) | (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.016) | |

| DPR | 0.029 | 0.014 | −0.008 *** | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.041 |

| (0.022) | (0.029) | (0.004) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.025) | |

| ETR | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.003 |

| (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.005) | |

| CR | −0.006 | −0.008 | 0.009 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.008 *** | 0.033 ** |

| (0.013) | (0.016) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.016) | |

| LTDTC | 0 | −0.003 | 0 | 0.042 ** | ||

| (0) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.019) | |||

| AT | 0.14 ** | 0.07 | 0.115 *** | 0.131 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.426 *** |

| (0.058) | (0.078) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.088) | |

| RT | −0.003 *** | −0.003 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.005) | |

| BS | −0.002 | 0.008 | −0.003 ** | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.004 |

| (0.012) | (0.013) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.013) | |

| NBM | 0.01 * | 0.005 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −0.002 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0) | (0) | (0.002) | |

| WB | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0.003) | |

| CEO_D | −0.037 | −0.042 | −0.016 *** | −0.01 ** | −0.009 ** | −0.103 ** |

| (0.038) | (0.045) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.052) | |

| CEO_A | 0.001 | −0.019 | 0.003 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.004 |

| (0.004) | (0.019) | (0) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.007) | |

| ICA | 0.002 | 0 | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0.001 |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0.007) | |

| C_CSR | 0.032 | 0.062 | −0.003 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.067 |

| (0.039) | (0.044) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.053) | |

| C_C | 0.201 * | 0.221 ** | 0 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.011 |

| (0.107) | (0.112) | (0.015) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.297) | |

| C_N | 0.062 | 0.042 | 0.005 | 0.012 ** | 0.011 ** | 0.059 |

| (0.043) | (0.048) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.071) | |

| COVID | 0.382 *** | −0.86 * | −0.003 | −0.007 | −0.026 *** | 0.053 |

| (0.079) | (0.474) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.010) | (0.046) | |

| FCF | 0.081 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.042 ** | ||

| (0.024) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.019) | |||

| NBMxCOVID | −0.032 *** | |||||

| (0.011) | ||||||

| FCFxCOVID | 0.047 ** | |||||

| (0.023) | ||||||

| RTxCOVID | 0.001 * | |||||

| (0) | ||||||

| LTDTCxCOVID | 0.004 * | −0.039 ** | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.018) | |||||

| ATxCOVID | 0.033 *** | |||||

| (0.02) | ||||||

| _cons | −0.944 * | −1.177 * | −0.346 *** | −0.584 *** | −0.575 *** | −1.145 * |

| (0.562) | (0.654) | (0.078) | (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.692) | |

| Observations | 818 | 799 | 698 | 681 | 681 | 349 |

| R2 | 0.0765 | 0.0088 | 0.2747 | 0.0759 | 0.0795 | 0.1962 |

| Mean VIF | 1.79 | 1.84 | 2.25 | 4.13 | 1.53 | 3.64 |

| F-stat (Driscoll-Kraay) | 3.082 | 33.900 | 34.55 | |||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are reported in parentheses. Note: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. Source: Authors’ work.

Table A3.

Nonlinear regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors for ROE and ROA.

Table A3.

Nonlinear regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors for ROE and ROA.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE re | ROE fe | ROA fe | ROA fe | ROA fe | ROA fe | |

| FS | 0.048 ** | 0.019 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.013 *** | ||

| (0.025) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||

| FA | 0.004 * | 0.002 | −0.003 * | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.002 |

| (0.004) | (0.021) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| SRGR | −0.004 | 0.044 | 0.049 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.032 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.082) | (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| DPR | 0.007 | 0.019 | −0.006 ** | −0.026 *** | −0.005 * | −0.003 |

| (0.03) | (0.029) | (0.004) | (0.009) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| ETR | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.005) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0) | |

| CR | −0.003 | −0.006 | 0.01 *** | 0.01 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.008 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.016) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| AT | 0.126 ** | 0.092 | 0.128 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.264 *** | 0.253 *** |

| (0.057) | (0.078) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.018) | (0.017) | |

| RT | −0.003 *** | −0.003 *** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| BS | 0.003 | 0.007 | −0.002 | −0.002 ** | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.002) | |

| NBM | 0 | 0.004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.008) | (0.006) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| WB | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| CEO_D | −0.03 | −0.043 | −0.013 *** | −0.011 ** | −0.01 ** | −0.008 * |

| (0.040) | (0.048) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| CEO_A | 0 | −0.011 | 0.007 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.005 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.019) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| ICA | 0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| C_CSR | 0.027 | 0.054 | 0 | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.004 |

| (0.040) | (0.045) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| C_C | 0.195 * | 0.251 ** | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.001 |

| (0.109) | (0.13) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.015) | (0.013) | |

| C_N | 0.051 | 0.068 | 0.01 ** | 0.011 ** | 0.006 | 0.009 * |

| (0.045) | (0.049) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| COVID | 0.137 *** | 0.13 *** | 0 | −0.001 | 0 | −0.002 |

| (0.043) | (0.047) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| FCF | −0.879 *** | 0.019 *** | ||||

| (0.273) | (0.002) | |||||

| LTDTC | 0 | −0.001 ** | 0 | 0 | ||

| (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |||

| FAxFA | −0.00003 * | |||||

| (0.0009) | ||||||

| FCFxFCF | 0.024 *** | |||||

| (0.009) | ||||||

| SRGRxSRGR | −0.003 ** | |||||

| (0.002) | ||||||

| DPRxDPR | 0.003 *** | |||||

| (0.002) | ||||||

| ATxAT | −0.055 *** | −0.049 *** | ||||

| (0.009) | (0.007) | |||||

| _cons | −1.007 * | 8.233 *** | −0.584 *** | −0.565 *** | −0.569 *** | −0.611 *** |

| (0.566) | (2.738) | (0.099) | (0.099) | (0.095) | (0.062) | |

| Observations | 818 | 799 | 698 | 698 | 698 | 681 |

| R2 | 0.0778 | 0.0344 | 0.1004 | 0.0683 | 0.1199 | 0.1456 |

| Mean VIF | 2.34 | 2.60 | 3.20 | 3.12 | 2.45 | 2.10 |

| F-stat (Driscoll-Kraay) | 3.689 | 28.585 | 28.568 | 34.859 | 39.598 | |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are shown in parentheses. Note: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. Source: Authors’ work.

Table A4.

Nonlinear regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors for ROIC and NM.

Table A4.

Nonlinear regression results with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors for ROIC and NM.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROIC re | ROIC re | NM fe | NM fe | NM fe | NM fe | |

| FS | 0.049 | |||||

| (0.033) | ||||||

| FA | 0 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.004 | −0.001 | 0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| SRGR | −0.008 | −0.007 | 0.041 *** | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.028 * |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| DPR | −0.035 | −0.035 | −0.031 *** | −0.083 *** | −0.027 *** | −0.028 *** |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.006) | (0.016) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| ETR | −0.002 | −0.003 | −0.003 ** | 0 | −0.002 ** | −0.003 ** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| CR | 0.038 ** | 0.034 ** | 0.018 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| AT | 0.394 *** | 0.417 *** | 0.039 ** | 0.029 * | 0.039 ** | 0.038 ** |

| (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| RT | 0.013 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.003 ** | 0.003 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.003 ** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| BS | −0.006 | −0.004 | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.046 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.016) | |

| NBM | −0.001 | −0.002 | 0.002 * | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| WB | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 * |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0) | (0) | (0) | (0) | |

| CEO_D | −0.109 ** | −0.111 ** | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.013 | −0.012 |

| (0.07) | (0.052) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| CEO_A | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| ICA | 0 | 0.002 | 0.002 ** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| C_CSR | −0.071 | −0.062 | 0.002 | −0.005 | −0.002 | −0.005 |

| (0.055) | (0.053) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| C_C | 0.097 | 0.083 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.01 | 0 |

| (0.295) | (0.299) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| C_N | 0.034 | 0.044 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| (0.072) | (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| COVID | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.007 |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.010) | (0.02) | (0.010) | (0.02) | |

| FCF | 0.018 *** | −0.259 *** | 0.02 *** | |||

| (0.006) | (0.066) | (0.006) | ||||

| LTDTC | 0.034 ** | 0.033 ** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| FCFxFCF | 0.007 *** | |||||

| (0.003) | ||||||

| DPRxDPR | 0.009 *** | |||||

| (0.003) | ||||||

| FSxFS | 0.011 *** | |||||

| (0.004) | ||||||

| LTDTCxLTDTC | −0.001 ** | −0.001 * | ||||

| (0.00003) | (0.00003) | |||||

| BSxBS | 0.002 *** | |||||

| (0.002) | ||||||

| _cons | −1.34 * | −1.186 * | 5.687 *** | −0.068 | 2.663 *** | 0.104 |

| (0.779) | (0.689) | (1.419) | (0.14) | (0.646) | (0.147) | |

| Observations | 355 | 349 | 718 | 701 | 701 | 701 |

| R2 | 0.1775 | 0.1922 | 0.0673 | 0.0875 | 0.0585 | 0.1096 |

| Mean VIF | 2.11 | 1.20 | 3.07 | 2.44 | 1.97 | 3.88 |

| F-stat (Driscoll-Kraay) | 7.977 | 8.425 | 8.626 | 7.966 | ||

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are shown in parentheses. Note: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at 1, 5, and 10%, respectively. Source: Authors’ work.

References

- Alqatamin, R. M. (2018). Audit committee effectiveness and company performance: Evidence from Jordan. Accounting and Finance Research, 7(2), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelache, G. (2009). Piața de capital în context european. Economică. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenzon, S., Shamshur, A., & Zarutskie, R. (2019). CEO’s age and the performance of closely held firms. Strategic Management Journal, 40(6), 917–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennouri, M., Chtioui, T., Nagati, H., & Nekhili, M. (2018). Female board directorship and firm performance: What truly matters? Journal of Banking & Finance, 88(1), 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakhlallh, M. M., Rashid, N., Abdullah, W. A., & Shehab, H. J. (2020). Audit committee and Tobin’s Q as a measure of firm performance among Jordanian companies. Journal of Advanced Research in Dynamical and Control Systems, 12(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, G. (2024). The impact of corporate governance on firm performance: Panel data evidence from S&P 500 information technology. Future Business Journal, 10(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harymawan, I., Agustia, D., Nasih, M., Inayati, A., & Nowland, J. (2020). Remuneration committees, executive remuneration, and firm performance in Indonesia. Heliyon, 6(2), e03452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., & Zhang, Y. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and firm performance: Cross-country evidence. International Review of Economics and Finance, 74(1), 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzey, C., Uyar, A., Nizaeva, M., & Karaman, A. (2021). CSR performance and firm performance in the tourism, healthcare, and financial sectors: Do metrics and CSR committees matter? Journal of Cleaner Production, 319(1), 128802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintah, P. A. (2016). Remuneration Committee governance and firm performance in UK financial firms. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 13(1), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohan, A., & Chandramohan, S. (2018). Impact of corporate governance on firm performance: Empirical evidence from India. International Journal of Research in Humanities, 6(2), 209–218. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3133491 (accessed on 3 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Naseem, M. A., & Lin, J. (2020). Does capital structure mediate the link between CEO characteristics and firm performance? Management Decision, 1(1), 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, A. M. (2015). The nomination committee and firm performance: An empirical investigation of UK financial institutions during the pre/post financial crisis. Corporate Board: Role, Duties & Composition, 11(3), 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta Martínez, M. C., & Álvarez, G. I. (2020). Do board characteristics drive firm performance? An international perspective. Review of Managerial Science, 14(1), 1251–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puni, A., & Anlesinya, A. (2020). Corporate governance mechanisms and firm performance in a developing country. International Journal of Law and Management, 62(2), 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, J., & Yilun, L. (2021). Firm size, firm age, and firm profitability: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting, Business and Management, 28(1), 101–115. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3867566 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. (2017). Board independence and firm performance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Future Business Journal, 4(1), 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, E. K., Nohade, N., & Etienne, H. (2022). Did the intensity of countries’ digital transformation affect IT companies’ performance during COVID-19? Journal of Decision Systems, 1(1), 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H., Fu, M., Pan, H., Yu, Z., & Chen, Y. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on firm performance. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(10), 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, I., & Stancu, D. (2012). Finanțe corporative cu excel. Economică. [Google Scholar]

- Temprano, M. F., & Gaite, T. F. (2020). Types of director, board diversity and firm performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 20(2), 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., & Guo, J. (2022). CSR committees, politicians and CSR efforts. Asian Review of Accounting, 30(3), 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtoglu, B., & Ararat, M. (2021). Female directors, board committees, and firm performance: Time-series evidence from Turkey. Emerging Markets Review, 48(1), 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zraiq, M. A., & Fadzil, F. H. (2018). The impact of nomination and remuneration committee on corporate financial performance. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 22(3), 1–6. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/f94b0ba421bfba09d8e7d5ae0f2f7efe/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=29414 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |