Abstract

Islamic finance has experienced rapid growth globally, surpassing the USD 2 trillion mark in 2017. As a result, the literature related to Islamic finance and banking is rather rich. Despite the richness of the literature, our knowledge of the marketing issues related to Islamic finance is modest and somewhat ambiguous. Therefore, we review several decades of research about the Islamic finance in various parts of the world. We identify and discuss three main research themes that draw on different conceptualization and theoretical lenses. After synthesizing their respective findings, we propose several avenues for future research that integrate these three research themes with the goal of developing a more nuanced understanding of Islamic finance and its marketing. While we believe that our review will mainly serve as a crucial reinvigoration and launch point for future research on Islamic finance marketing, it is also of great practical benefit for policymakers of various countries and especially managers of financial service firms interested in marketing Islamic banking and financial services to their customers.

1. Introduction

Over the last several decades, Islamic finance and banking has experienced unprecedented growth globally (IFSB 2018; Khan and Bhatti 2008a; H.F. Khan 2017). This trend is visible mostly in Muslim majority countries because Islamic banking and finance is one of the most practiced aspects of Muslims. However, recently, the growth and popularity of Islamic finance have spread to many non-Muslim countries in Asia and Europe as well (Alam 2019). The reason is that now many countries are diverse culturally with a sizable population of Muslims due to an increase of 49% in international migration between 2000 and 2017 (Vora et al. 2019). Such a high level of immigration in different parts of the world is responsible for this diversity that has resulted in the intermingling of values, interests, and consumption patterns of consumers from a diverse background (Grier and Deshpandé 2001; Oullet 2007; Penaloza and Gilly 1999). Despite this cultural intermingling, many minority groups, particularly Muslims, have found to maintain their own unique consumption behavior due to the intangible elements of religious beliefs and values (e.g., Jamal and Shukor 2014; Jamal et al. 2012; Goldman and Hino 2005; Jamal 2003; Burton 2000; Ackerman and Tellis 2001; Wilson and Liu 2011). This view on the cultural shifts in many countries makes marketing of Islamic finance both in Muslim and non-Muslim countries an important area of inquiry.

Moreover, the literature related to the marketing to Muslim customers in various parts of the world proposes Islamic finance marketing as an important research agenda and suggests that sharia-compliant financial services are a growing niche within the financial service sector of the Muslim countries and the countries which have a sizeable Muslim population (IFSB 2018; Khan and Bhatti 2008b; Ford 2012). Islamic finance marketing has been recognized and addressed by various articles pinpointing several key trends in the Islamic finance industry (Khan and Bhatti 2008b; Ford 2012). While deregulation and technological advancements have resulted in traditional financial services adopting certain highly scrutinized innovative practices, Islamic finance has grown considerably due to more responsible practices (Alam 2013; Lyons et al. 2007).

Consequently, research on Islamic finance has sharply accelerated within the past two decades, first in management, finance, and economics (see, Al Rahahleh et al. 2019; Ayub 2018; Fang 2014; Khan and Bhatti 2008a; Kurpad 2016) and more recently, in international business and marketing literature (see, Belwal and Al Maqbali 2019; Butt et al. 2018; Fang 2016; Amin et al. 2014; Khaliq et al. 2011). Despite its robustness, the literature on Islamic finance remains fragmented, offering little guidance for researchers attempting to conceptualize the marketing strategies of Islamic finance. In addition, the mainstream marketing literature has not focused properly on this growing market niche because only recently Islamic financial service sector has started to gain some legitimacy in the mainstream literature (Fang 2016).

Against this backdrop, the objective of this article is to provide a review of the literature with a view to develop an understanding of the marketing process of Islamic finance and propose a research agenda for Islamic finance marketing strategies. Although the extant literature does provide comprehensive reviews of Islamic finance literature (e.g., Narayan and Phan 2019; M.A. Khan et al. 2017; Abedifar et al. 2015), it takes a more holistic view rather than looking at the issues related to marketing of Islamic finance. Our research provides a key contribution by offering a deep analysis of past Islamic finance marketing scholarship. Specifically, we ask, what have we learned from the various theoretical foundations and empirical findings that underpin the vast Islamic finance and banking literature, particularly as it relates to the marketing of Islamic finance? We use this review to advocate for a broader approach and describe how earlier research can be substantially enriched by a multidimensional focus on Islamic banking and finance customers, organizational factors, and regulatory relationships. Our review also promotes an understanding of the overall Islamic finance concept with a view to minimizing the risks involved in the implementation of the Islamic financial system in various parts of the world. The rest of the article is organized as follows. First, we review the overall Islamic finance literature and then group them into relevant themes. Next, we review the extant literature related to each of the research themes. We conclude the article with a discussion of the implications for the literature and new research agenda.

2. Review Methodology

To conduct a rigorous review of the extant Islamic finance marketing literature that may lead to reliable and insightful findings, we used the multi-stage review approach, including (1) planning, (2) article collection and, (3) analysis (Tranfield et al. 2003). During the planning stage, we determined the goals and scopes of research, selected several keywords, and identified the publication sources. We used several review sources to identify potential publications of interest for our review and particularly focused on screening the Academic Search Complete, EBSCO, Science Direct, and ABI Inform databases for relevant articles.

We used the following search terms in the title, abstract and keywords: “Islamic finance”, “Islamic banking”, “Islamic investment”, sharia compliant finance”, “sharia compliant banking”, “Islamic finance marketing”, “Islamic finance in Muslim countries”, “Islamic finance in non-Muslim majority countries”, “Islamic finance in emerging markets”, “Marketing Sukuk”, and “Islamic finance in secular countries”. We used these search terms for searching Google Scholar as well. Using a snowballing technique, where search results were used to generate new leads (Biernacki and Waldorf 1981), we reviewed all relevant articles cited in retrieved articles as well as relevant articles citing them on Google Scholar. The choice of data sources, review protocol, and keywords reflected our desire to offer a deeper understanding of the present research on Islamic finance and its marketing. The number of articles that we retrieved for this review contains sufficient information to fully comprehend the essence of Islamic finance marketing issues and, therefore, meets the criteria for the systematic review approach (Tranfield et al. 2003). During the article review process, we attempted to identify key research themes, main findings, important research gaps, and research questions discussed next.

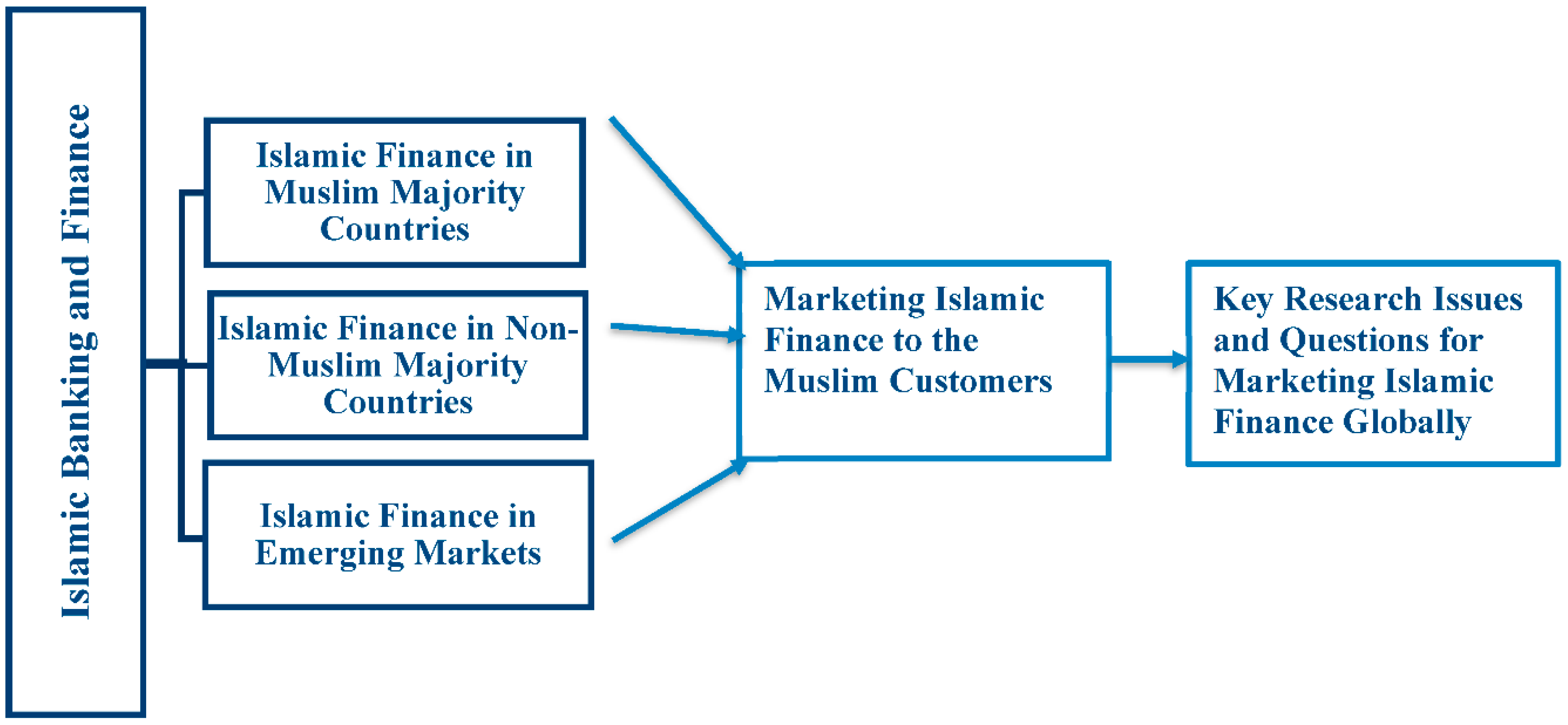

3. Islamic Financial Service Sector

The history of Islamic banking and finance dates backs to the 1960s with the establishment of banking services based on profit sharing and interest-free savings in Egypt (El-Galfy and Khiyar 2012). But the Islamic finance started to gain momentum only in the early 1990s. Over the past three decades, the fields of economics, management, finance, marketing, and international business have answered the foundational question “what is Islamic finance?” in a variety of ways. For this research, the term Islamic finance includes, Islamic banking and financial services, sharia-compliant investment products, and Sukuk (Islamic bonds). Because of the global expansion and growth of Islamic finance, the literature on this topic is rather rich (e.g., Janahi and Al Mubarak 2017; Dariyoush and Hussin 2016; Fang 2016; Setyobudi et al. 2016; Malik et al. 2011; Elbeck and Dedoussis 2010). More than 100 Islamic banks now exist in over 35 Muslim and non-Muslim countries alike (Ariff and Rosly 2011). However, the market penetration of Islamic finance among Muslims in many parts of the world is somewhat slow, because this niche financial services sector is facing several regulatory problems and marketing challenges (Khan and Bhatti 2008b). A small but consistent theme in the literature is that the system of Islamic finance is rather robust in the Muslim majority countries. Yet, the Muslim population has grown sharply in non-Muslim countries leading to a growing demand for Islamic finance worldwide. Furthermore, the extant literature has mainly focused on the performance of the Islamic finance sector, arguing that Islamic finance is distinct from the conventional financial system (Abdull-Majid et al. 2010; Derbel et al. 2011). While the literature has presented a strong case for the global adoption of Islamic finance, it has failed to answer the question, how to market and promote Islamic finance globally? (Alam 2015). Similarly, Azmat et al. (2019) have emphasized the need for studies on how to persuade customers to adopt Islamic finance? With this critique in mind, we provide a review of the growing literature, which we have categorized into several themes, as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework and key research issues.

Interestingly, until now, these three research themes have had limited engagement with each other. This fragmentation limits our understanding of the key challenges facing Islamic finance by delimiting the types of research issues that the researchers pursue. We consider this as an opportunity to expand Islamic finance research.

3.1. Research Theme 1: Islamic Finance Marketing in Muslim Countries

This first research theme, which we label “Marketing of Islamic Finance in Muslim Countries”, includes studies that apply traditional managerial corporate governance questions and theories to the customer adoption and retention of Islamic finance in Muslim majority countries. This body of work focuses on the different roles and responsibilities of key corporate actors within the organizations and the policymakers of a country. The fields of finance, economics, international business, and marketing are at the cusp of a wave of research on Islamic finance, particularly in Muslim countries. The first wave of research relates to the work completed in the Middle East (e.g., Ahmed and Khababa 1999; Chazi et al. 2018; Srairi 2010; Warsame and Ireri 2018; Ireland 2018; Hussein 2010) and North Africa (e.g., Khafafa and Shafii 2013; Souiden and Rani 2015) focusing mainly on corporate governance and efficiency of Islamic financial institutions. Indeed, Islamic finance literature is fragmented due to its many issues and a myriad of factors. Therefore, for the sake of parsimony and also to make a coherent contribution to our understanding of the marketing issues related to Islamic finance, we must first define our focal concept, which is the process of marketing Islamic finance in Muslim countries. As a result, we restrict our review as it relates only to some of the key marketing areas and issues, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected literature on Islamic finance marketing in Muslim countries.

The second wave of research suggests that several non-Arab Muslim majority countries have successfully adopted the Islamic banking system including, Indonesia (Usman et al. 2017), Malaysia (Mahdzan et al. 2017; Amin 2013; Haron et al. 1994), Iran (Estiri et al. 2011; Shokuhi and Nabavi Chashmi 2019; Ezzati 2019), Turkey (Korkut and Özgür 2017), Bangladesh (Zebal 2018), and Pakistan (Butt et al. 2018; Imran et al. 2011). Most of these studies also focus mainly on the performance and efficiency of Islamic financial institutions. The third wave of research, which is imminent, is expected to go beyond the roles and responsibilities of key corporate actors and policymakers, and delve deeper into the evolution of various areas in finance, economics, international business, and marketing, as the effects of Islamic finance trickle down and get more entangled with surrounding institutional arrangements. An in-depth analysis of the literature summarized in Table 1 provides three interesting insights into the limited scope of these studies. First, focusing mostly on the adoption of Islamic finance by the customers, several studies touch upon marketing issues. Yet, the marketing topics covered in the literature mostly relate to consumer behavior and new product or service adoption issues. Second, this literature base tends to be agnostic about how to develop overall marketing strategies for Islamic finance in Muslim countries. Third, most of the marketing-focused studies are conducted in non-Arab Muslim countries, even though the Arab Muslim nations constitute the largest market for Islamic finance. These insights and gaps in the literature point to an urgent need for more research on several Islamic finance marketing issues in many Arab and non-Arab Muslim countries.

3.2. Research Theme 2: Islamic Finance Marketing in Non-Muslim Majority Countries

The Islamic banking system is thriving in several non-Muslim majority secular countries including, Australia (Rammal and Zurbruegg 2007), Britain (Abdullrahim and Robson 2017), Singapore (Gerrard and Cunningham 1997), and in several other Asian and European countries (see Fang 2016; Hafsa Orhan Åström 2013). This trend is driven by calls to reconceptualize sharia and its role in business in many secular countries (e.g., Islam and Rahman 2017). Many financial service firms in these secular countries are responding to the needs of the Muslim minority customers because they are looking for growth outside of North America and the European Union (El-Bassiouny 2014). In addition, the policymakers in several non-Muslim majority nations had eagerly adopted the concepts of Islamic banking and finance many years ago to promote the growth of their financial system (Imran et al. 2011; Fang 2016). In addition, due to the large migration trend, Europe has become the center of Islamic finance among non-Muslim countries. For example, although the population of Muslims in the UK is only three million, London has become a hub for Islamic finance in Europe (Volk and Pudelko 2010; Bershidsky 2013). This rapid adoption of Islamic finance in some of the non-Muslim secular countries has recently received considerable attention in the literature. Yet, we believe that a renewed endeavor is also needed to continue research on the marketing of Islamic finance in non-Muslim majority countries. A summary of the key Islamic finance studies in non-Muslim majority countries, as reported in the literature, is given in Table 2. Starting with Europe, Opromolla (2012) studied the feasibility of Islamic banking in Italy and reported that the legislators are taking some steps to accommodate Islamic finance in the Italian banking system. Similarly, Richardson (2011) strongly supports the idea of establishing Islamic financial institutions in Ireland despite the small Muslim population in that country. In the case of the United Kingdom, Hussain (2014) argues that Islamic finance will flourish if financial service firms create more awareness among the customers about the availability of the services. Abdullrahim and Robson (2017) investigated the importance of service quality among the U.K Muslim customers and reported that the adoption of products depends on proper service delivery by financial institutions. Several other European studies (e.g., Trakic 2012; Kaakeh et al. 2018; Hamad and Duman 2014; Volk and Pudelko 2010) have also advocated the adoption of Islamic finance in their respective countries, yet they narrowly focused on customer behavior issues leaving a wide gap on the overall marketing of Islamic finance in many European countries containing sizable Muslim population.

Table 2.

Selected literature on Islamic finance marketing in non-Muslim majority countries.

Several countries in Asia pacific have also shown a keen interest in accepting and promoting Islamic finance as a viable financial system. In the case of Australia, Rammal and Zurbruegg (2007) have argued for more promotion of Islamic finance in the country. Similarly, Abdur Razzaque and Chaudhry (2013) have illustrated the customers’ purchase decision process for Islamic finance. In the same vein, Mirza and Halabi (2003) reported the risks and challenges in the adoption of Islamic finance in Australia. Moving on to another Asian pacific country Singapore, Gerrard and Cunningham (1997) emphasized the need for more marketing and promotion of Islamic finance in that country. However, Lai and Samers (2017) adopted a holistic approach and focused on the overall governance issue of the Islamic financial system in the country. In the case of the United States, the literature is rather mute on the issue of marketing and adoption of Islamic finance. Although Taylor (2003) and more recently Schmidt (2019) had argued that there was a potential for Islamic finance to grow in the US, not much effort has been expended on studying the adoption and marketing of Islamic finance in that country or even in North America.

All in all, the literature related to Islamic finance marketing has started to gain some strength in many non-Muslim secular countries across the globe. Yet, more needs to be done to elevate the Islamic finance as a viable financial system in various parts of the world. The focus should be on the secular countries that have shown an interest in adopting Islamic finance. To that end, more research on a variety of strategies for marketing and promoting Islamic finance is needed.

3.3. Research Theme 3: Islamic Finance Marketing in Emerging Countries

According to the United States Department of Commerce, the ten Big Emerging Markets (BEMs) are Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey. These emerging markets have become a force in a global economy that offers great opportunities to discover new perspectives in marketing and finance. As Seth (2011) has argued, the sheer size of the consumer base in countries, such as India and China, has shifted the emerging markets from periphery to the core of global competition. As these emerging markets have become more diverse, scholarly interest in these countries has grown concomitantly. Of the ten BEMs, Indonesia and Turkey are the Muslim majority countries with a well-established Islamic banking and finance system that were discussed previously in this article. Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Poland have a very small Muslim population, and, therefore, the issue of Islamic finance in these countries is insignificant. Consequently, we confine our review to three emerging markets of India, China, and South Africa, which have a larger Muslim population. In addition, we consider South Korea, which, despite its small population, has taken some steps for the establishment of Islamic finance. Some of the key Islamic finance marketing studies in these emerging countries are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected literature on Islamic finance marketing in emerging countries.

Like other emerging markets, India is having a disruptive impact on marketing practice and theory (Seth 2011; Bello et al. 2016). India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is expanding by more than 9% per year, and the country is the 4th largest economy in the world. Muslims are the second-largest ethnoreligious group after the majority Hindu community and thus the largest minority group in India. The Muslim minority, with a population exceeding over 170 million, constitutes about 14.6 percent of India’s total population. The population is expected to grow to 236 million by 2030, and the share is likely to be 18%–19% of India’s population (Potluri et al. 2017). By 2050, India’s Muslim population is projected to become the largest in the world (Kurpad 2016).

Despite India’s large Muslim population, the concept of Islamic finance in the country is still in its infancy. Notably, India’s mainstream financial service sector is growing by more than 40% annually (Jain 2013). Many financial service firms have been quick to take advantage of the corresponding surge in demand for various banking products. Given the growth rate in the financial service sector and the growing needs of the large population of Muslims, India has the potential to become the largest market for Islamic finance worldwide (Islam and Rahman 2017). However, surprisingly many Indian financial services firms are rather slow in entering the new market niche of Islamic finance. With this phenomenon in mind, there have been calls for the introduction of Islamic finance in India (e.g., Mohan 2014). In addition, the Indian government formed the National Minority Development Finance Corporation (NMDFCI) to further ease the flow of banking services among Muslim customers (Jamaluddin 2013). The Mumbai stock exchange also promoted an Islamic Index to meet the needs of Muslim investors. These developments point towards the initial steps that both the Indian companies and policymakers have adopted to offer financial products specifically for Muslim customers. Although, the issue of sharia-compliant banking has attracted some attention from both scholars, and policymakers alike, (Ahmed 2013; Hammond 2012; Bose and Yedukumar 2013), India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recently decided against the introduction of Islamic finance mainly due to political reasons (Arora 2018). Indeed, with an enormous Muslim population and the significant requirement of the capital in the country, there is a scope for massive growth in Islamic banking in India. Recently, Alam (2019) studied the process of developing new sharia-compliant financial services in India and suggested that more studies related to the marketing of Islamic finance are needed in that emerging country. Similarly, Kurpad (2016) made a strong case for a dual banking system in India, where Islamic finance can coexist with other traditional financial and banking systems. Furthermore, in the opinion of Chakrabarty (2015), India must adopt Islamic finance as a tool for poverty alleviation of Muslims as well as other communities. In the same vein, Kumar and Sahu (2017) argued for the introduction of sharia-compliant stock indices in India. As the debate on the issue of Islamic finance is heating up in India, more scholarly studies on the process of developing and marketing Islamic financial services are needed. These phenomena offer an opportunity for Islamic finance scholars to study the process of developing and marketing Islamic finance in India.

Another emerging market, China, has almost 22 million Muslims constituting about 1.6% percent of China’s population. Yet, due to many restrictive and regulatory measures adopted by the Chinese government, Islamic finance has not thrived in that country. Only a few articles provide merely a comparative analysis of Chinese Islamic finance and its effect on the country’s economy (Majdoub and Sassi 2017; Bo et al. 2016) and a commentary on China’s sharia-compliant equity market (Saiti and Masih 2016). Although in comparison to India, China has a small Muslim population, being an economic powerhouse of the world, China offers great potential and opportunity to study the marketing of Islamic finance in that country. Moving on to another emerging country, South Africa, the number of Muslims in South Africa is about one million, constituting approximately 1.9 percent of the country’s population (Statistics South Africa 2016). An extensive search of the literature reveals only two empirical studies related to the marketing of Islamic finance in South Africa (Kholvadia 2017; Vahed and Vawda 2008). Both studies have argued that the adoption of Islamic finance among South African Muslims is rather low, and as a result, the market penetration of Islamic finance in that country is still in its infancy. Lastly, in South Korea, despite its very small Muslim population, Wan Ahmad et al. (2019) have emphasized the need for creating awareness about Islamic finance among both Muslim and non-Muslim customers in that country. In that study, South Korean citizens who have resided in Muslim majority countries were found to be very little informed about various aspects of Islamic finance. However, exposure to information regarding Islamic financial services was found to generate significant interest among them. Although the size of the Islamic market both in South Africa and South Korea is rather small, the dearth of empirical studies in these two countries points to an interesting research gap.

In summary, the literature on Islamic finance in emerging markets has enhanced our understanding of several key theoretical lenses in finance and marketing. Extant literature suggests that emerging markets are not only viable markets for Islamic finance but also critical sources of global innovation and competency. Dariyoush and Hussin (2016) also opined that the large and growing population of Muslim customers in some of the big emerging markets provides a large platform for the use of Islamic financial services. Yet, many emerging markets differ among themselves in their competitive and institutional environments. Particularly, larger emerging markets, such as India and China, are characterized by severe market complexities because of sectorial heterogeneity and intense competition. The literature sheds light on the lack of a thorough analysis of how the marketers of Islamic finance shall manage these complexities. Therefore, we see considerable scope for future research in this area. The literature further changes our view towards the theory of marketing to minority customers in non-Muslim majority countries.

4. Conclusions and Implications

Prior literature on Islamic finance has largely focused on the feasibility and efficiency of Islamic finance in various parts of the world. More recent research shows that Islamic finance has been evolving from a “foundational paradigm” into a “strategic implementation paradigm,” which adds value to the conventional financial system of a country (e.g., Shokuhi and Nabavi Chashmi 2019; Ezzati 2019; Alam 2019). Our review identifies key theoretical insights and empirical findings and shows that there has been significant progress in the last three decades towards consensus on several issues. We undertook this study to advance our understanding of one key issue, which is the marketing of Islamic finance, an area that has largely been overlooked in the extant literature.

Our review provides several contributions to the literature of Islamic finance. First, we identify three dominant themes of research and illustrate how each theme relies on the different conceptualization of Islamic finance, different analytical foci, different theoretical approaches, and underlying mechanisms. Second, we offer a comprehensive review of each of these research themes. In particular, we propose that while these three research themes have collectively produced several key scholarly insights, they have mostly evolved independently from one another in terms of research hypotheses and perspectives. Third, our review helps in abstracting the particularities of the topic and explaining how to advance the theoretical understanding of Islamic finance by connecting to other fields, such as marketing, customer adoption behavior, and several other issues to facilitate cross-fertilization.

5. Future Research Agenda

Our rigorous review of existing literatures reveals two key areas for future research. The first relates to the subject matter of Islamic finance marketing, and the second is about the overall maturity of Islamic finance as the mainstream research area in various parts of the world. To this end, we have identified several research questions that we think warrant greater attention. First, we propose several research questions related exclusively to key marketing issues of Islamic finance globally. Next, we develop research questions related to other relevant subject matters surrounding the development and adoption of Islamic finance in both non-Muslim majority and Muslim majority countries.

6. Marketing Related Research Questions

Although we argue for interdisciplinary research and especially for teaming up with economics, law, and finance scholars, from our perspective, there is an urgent need for a more exclusive focus on the marketing of Islamic finance due to the major gaps in this area. For example, our current review of the literature points to only limited coverage of the marketing issues in a limited number of countries. Some of the issues covered are product adoption (e.g., Islam and Rahman 2017; Richardson 2011), advertising and promotion (e.g., Schottmann 2014; Rammal and Zurbruegg 2007), service innovation (e.g., Alam 2015; Moktar et al. 2006), consumer behavior (e.g., Kaakeh et al. 2018; Korkut and Özgür 2017), and service quality analysis (e.g., Al-Jazzazi and Sultan 2014). With this in mind, several future research questions offer the substantial potential to extend our collective thinking about challenges in marketing of Islamic finance. This list is by no means comprehensive. However, it outlines some of the most noticeable gaps given the current state of research.

- RQ1: How to brand Islamic financial products and services in various parts of the world?

- RQ2: How the current developments in emerging technology and digital marketing, such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality, impact the marketing of Islamic financial services?

- RQ3: What is the development process of new Islamic financial services?

- RQ4: How to involve Muslim customers in developing new Islamic financial services?

- RQ5: What regulatory factors and legal issues affect the marketing of Islamic financial products and services?

- RQ6: How to use marketing communications to promote Islamic financial products?

- RQ7: What digital and social media marketing strategies are appropriate for marketing and promoting Islamic finance?

- RQ8: What are the optimal delivery process and channel strategies for distributing Islamic financial services?

- RQ9: What sales strategies are needed to help a firm sell more Islamic financial services?

- RQ10: What competitive positioning strategies are appropriate in differentiating Islamic finance from traditional financial services?

- RQ11: How to measure the service quality and customers’ satisfaction and their mutual relationship in the context of Islamic finance?

- RQ12: What marketing strategies are needed to market Islamic financial products and services to non-Muslim customers in various parts of the world?

7. Research Questions Related to Other Issues

Opportunities also abound for scholars to contribute to the broadly defined body of research we have revealed, and to offer nuanced approaches to understanding how Islamic finance may evolve into the mainstream financial services sector in different parts of the world. Indeed, the growing need for Islamic banking and finance is a global phenomenon (Bershidsky 2013; El-Bassiouny 2014). Particularly, in the context of non-Muslim majority countries, marketing Islamic financial services should be a key area of inquiry because ignoring the importance of Muslim customers can prove costly, considering the fact that the Muslim customers are a growing market niche. Although the marketing of Islamic finance poses political, regulatory, and administrative constraints to many service firms worldwide, it is a worthwhile venture and needs to be investigated further. In addition, the low population growth of the majority group, coupled with the large population increase in the Muslim minority group in many countries, means it is time to target this growing niche more aggressively.

As Muslim customers and their purchasing power grow, they will demand that the firms be responsive to their needs for financial services. Firms that can successfully offer Islamic financial services for the Muslims customers will create a win–win situation for their businesses and for their customers. Furthermore, business managers are increasingly under pressure to find ways to achieve growth. Developing and offering Islamic financial services to fulfill the unmet needs of Muslim customers is one key strategy for achieving growth. Yet, as with any new venture, marketing Islamic finance, particularly in non-Muslim majority countries, can also be risky. An investigation of the research questions proposed by this review article can offer an understanding of how to manage the risks that are inherent in implementing and marketing Islamic financial products and services particularly in emerging and non-Muslim majority countries with complex business environments.

Policymakers of the countries with a sizable Muslim population must take proactive measures for the massive penetration of Islamic financial services among their minority Muslim population for several reasons. First, the process will contribute to a greater financial stabilization and open the door for better inclusion of Muslim customers. Second, Islamic finance will further boost the economy of a country because it will result in the free flow of finance to millions of new and emerging customers. Third, it will introduce a new mode of banking, making the financial market of a country more robust, competitive, and mature. Finally, it will offer diplomatic advantages in dealing with the Muslim dominant and rich nations in the Middle East, especially to attract more lucrative direct investment in the country. Moreover, in the case of many non-Muslim majority countries, the scholars have only focused on some marketing issues as well as on the feasibility and regulatory constraints in marketing Islamic finance (e.g., Opromolla 2012; Petracci and Rammal 2014; Trakic 2012; Hussain 2014; Tameme and Asutay 2012; Mirza and Halabi 2003). Considering the above phenomena, future studies can contribute to the topic by going deeper into the following research questions.

- RQ1: How can the Islamic financial system and the mainstream financial system coexist in a country with a sizable Muslim population?

- RQ2: How does Islamic finance contribute to the economic wellbeing of non-Muslim majority countries?

- RQ3: How would the introduction of Islamic finance in non-Muslim majority countries dispel the notion of marginalization of the Muslim population?

- RQ4: What critical steps should the policymakers in non-Muslim majority countries take to develop and promote Islamic finance?

- RQ5: How can a financial services firm take advantage of the growth in the emerging market by offering Islamic finance to Muslim customers?

- RQ6: What cross-country differences exist in the marketing, adoption, and promotion of Islamic finance in various non-Muslim majority countries?

- RQ7: What are some of the key cross-country differences in the marketing, adoption, and promotion of Islamic finance within the emerging markets with a sizable Muslim population?

- RQ8: What decision models do customers use in selecting Islamic financial services over the mainstream traditional financial services in non-Muslim countries?

Moving on to the Islamic finance literature related to Muslim majority countries, the scholars are unanimous on the need for more studies in this area because there is a dearth of infrastructure and technical knowhow for managing Islamic finance worldwide, including Muslim majority countries (see Chaudhury and Bhatti 2017; H.F. Khan 2017). Scholars have recommended that the managers and practitioners must develop the market segment of Islamic banking more aggressively because, despite the popularity of Islamic finance in Muslim countries, the adoption rate is somewhat lower (Usman et al. 2017). The findings from our present review also support these conclusions. For example, most studies in the Muslim majority countries have focused only on the issue of efficiency of the Islamic finance system and customer satisfaction (e.g., Moktar et al. 2006; Sufian 2010; Kaabachi and Obeid 2016; Ltifi et al. 2016; Chazi et al. 2018; Hussein 2010; Butt et al. 2018; Estiri et al. 2011). We have identified numerous critically important yet unexplored opportunities to integrate insights from the global Islamic finance literature with a focus on Muslim majority countries. The following sample of research questions suggests the issues we consider to be most urgent regarding the marketing, promotion, and adoption of Islamic finance in Muslim majority countries.

- RQ1: What critical steps should policymakers of the Muslim majority countries take to develop and promote Islamic finance in their respective countries?

- RQ2: How do various institutional and organizational factors in Muslim majority countries affect the overall promotion of Islamic finance?

- RQ3: Taking a cross-country perspective, how do varying rules and regulations in different Muslim and non-Muslim majority countries affect the decisions of a financial services firm to develop and introduce Islamic financial services?

- RQ4: What are the main motivating factors for the customers to adopt Islamic finance in Muslim majority countries?

In summary, the marketing of Islamic finance as an area remains largely in need of empirical research. We believe that this article is only a catalyst for future research in a field growing in theoretical and practical importance. It is hoped that the themes that emerged from this review will help lay the foundation upon which later analysis and research of this topic can be built.

Author Contributions

I.A. conceptualized the article; undertook literature review, wrote conclusions; P.S. undertook literature review, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdull-Majid, Mariani, David S. Saal, and Giuliana Battisti. 2010. Efficiency in Islamic and conventional banking: An international comparison. Journal of Productivity Analysis 34: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullrahim, Najat, and Julie Robson. 2017. The importance of service quality in British Muslim’s choice of an Islamic or non-Islamic bank account. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 22: 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdur Razzaque, Mohammed, and Sadia Nosheen Chaudhry. 2013. Religiosity and Muslim consumers’ decision-making process in a non-Muslim society. Journal of Islamic Marketing 4: 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedifar, Pejman, Shahid M. Ebrahim, Philip Molyneux, and Amine Tarazi. 2015. Islamic banking and finance: Recent empirical literature and directions for future research. Journal of Economic Surveys 29: 637–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Youssef, Mariam Mourad Hussein, Wael Kortam, Ehab Abou-Aish, and Noha El-Bassiouny. 2015. Effects of religiosity on consumer attitudes toward Islamic banking in Egypt. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 33: 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, David, and Gerrad Tellis. 2001. Can culture affect prices? A crosscultural study of shopping and retail prices. Journal of Retailing 77: 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Abu Umar Faruq, and M. Kabir Hassan. 2007. Regulation and performance of Islamic banking in Bangladesh. Thunderbird International Business Review 49: 251–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Ashfaque, Kashifur-Ur-Rehman, Iqbal Saif, and Nadeem Safwan. 2010. An empirical investigation of Islamic banking in Pakistan based on perception of service quality. African Journal of Business Management 4: 1185–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Syed. 2013. Asia focus: Sun rises in the east. Islamic Finance Asia, October 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Abdulkader Mohamed, and Noureddine Khababa. 1999. Performance of the banking sector in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Financial Management & Analysis 12: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, Muhammad N., Ahmed Imran Hunjra, Syed Waqar Akbar, Kashif-Ur-Rehman, and Ghulam Shabbir Khan Niazi. 2011. Relationship between customer satisfaction and service quality of Islamic banks. World Applied Sciences Journal 13: 453–59. [Google Scholar]

- Al Rahahleh, Naseem, M. Ishaq Bhatti, and Farida Najuna Misman. 2019. Developments in risk management in Islamic finance: A review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 12: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Intekhab. 2013. Customer interaction in service innovation: Evidence from India. International Journal of Emerging Markets 8: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Intekhab. 2015. Developing Sharia-compliant Financial Services for the Muslim Customers in India. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance 11: 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Intekhab. 2019. Interacting with Muslim customers for new service development in a non-Muslim majority country. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 1017–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, Aye Mengistu. 2012. Factors influencing consumers’ financial transactions in Islamic banks compared with conventional banks: Empirical evidence from selected middle-east countries with a dual banking system. African & Asian Studies 11: 444–65. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jazzazi, Akram M., and Parves Sultan. 2014. Banking service quality in the Middle Eastern countries. International Journal of Bank Marketing 32: 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salem, Fouad, and Mhamed M. Mostafa. 2019. Clustering Kuwaiti consumer attitudes towards sharia-compliant financial products. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 37: 142–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, Hussein, and Abdullah Al-Amiri. 2003. Analysing service quality in the UAE Islamic banks. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 8: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, Hussein, Adel Shehadah Lafi, and Md Hamid Uddin. 2009. Bank image in the UAE: Comparing Islamic and conventional banks. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 14: 232–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hanudin. 2013. Factors influencing Malaysian bank customers to choose Islamic credit cards: Empirical evidence from the TRA model. Journal of Islamic Marketing 4: 245–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Muslim, Ziadi Isa, and Rordrigue Fontaine. 2013. Islamic banks. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 31: 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hanudin, Abdul-Rahim Abdul-Rahman, and Dzuljastri Abdul Razak. 2014. Theory of Islamic consumer behaviour. Journal of Islamic Marketing 5: 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Hanudin, Abdul-Rahim Abdul-Rahman, and Dzuljastri Abdul-Razak. 2016. Malaysian consumers’ willingness to choose Islamic mortgage products: An extension of the theory of interpersonal behaviour. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 34: 868–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, Mohamed, and Saiful Azhar Rosly. 2011. Islamic banking in Malaysia: Unchartered waters. Asian Economic Policy Review 6: 301–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Sunit. 2018. Dropping the idea of Islamic banking in India will leave millions shortchanged. The Wire, January 17. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, Madiha, Samina Aslam, Amir Razi, and Syed Atif Ali. 2011. A comparative analysis of bankers’ perception on Islamic banking in Pakistan. International Journal of Economics and Research 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Åström, Hafsa Orhan. 2013. Survey on customer related studies in Islamic banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing 4: 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, Muhammad. 2018. Islamic finance crossing the 40-years milestone—The way forward. Intellectual Discourse 26: 463–84. [Google Scholar]

- Azmat, Saad, Haiqa Ali, Kym Brown, and Michael T. Skully. 2019. Persuasion in Islamic Finance (24 January 2019). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3322056 (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Bello, Daniel, Radulovich Lori, Rajshekhar Javalgi, Robert Scherer, and Jennifer Taylor. 2016. Performance of professional service firms from emerging markets: Role of innovative services and firm capabilities. Journal of World Business 51: 413–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, Rakesh, and Ahmad Al Maqbali. 2019. A study of customers’ perception of Islamic banking in Oman. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 150–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bershidsky, Leonid. 2013. Islamic finance can save the world. Bloomberg News, October 29. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, Patrick, and Dan Waldorf. 1981. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research 10: 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bizri, Rima. 2014. A study of Islamic banks in the non-GCC MENA region: Evidence from Lebanon. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 32: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Ding, Engku Rabiah Adawiah, and Buerhan Saiti. 2016. Sukuk issuance in china: Trends and positive expectations. International Review of Management and Marketing 6: 1020–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, Suprio, and Puja Yedukumar. 2013. Finally waking up to Islamic finance opportunities. Islamic Finance Asia, February 15. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Dawn. 2000. Ethnicity, identity and marketing: A critical review. Journal of Marketing Management 16: 853–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, Irfan, Nisar Ahmad, Amjad Naveed, and Zeeshan Ahmed. 2018. Determinants of low adoption of Islamic banking in Pakistan. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 655–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, Amit Kumar. 2015. Islamic micro finance: Theoretical aspects and Indian status. The Journal of Commerce 7: 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, Shiv, and Dave Crick. 2004. Attempts to more effectively target ethnic minority customers: The case of HSBC and its South Asian business unit in the UK. Strategic Change 13: 361–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, Masudul Alam, and Ishaq Bhatti. 2017. Heterodox Islamic Economics: The Emergence of an Ethico-Economic Theory. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chazi, Abdelaziz, Ashraf Khallaf, and Zaher Zantout. 2018. Corporate Governance and Bank Performance: Islamic Versus Non-Islamic Banks in GCC Countries. Journal of Developing Areas 52: 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariyoush, Jamshidi, and Nazima Hussin. 2016. Forecasting patronage factors of Islamic credit card as a new e-commerce banking service: An integration of TAM with perceived religiosity and trust. Journal of Islamic Marketing 7: 378–404. [Google Scholar]

- Derbel, Hatem, Taoufik Bouraoui, and Neila Dammak. 2011. Can Islamic finance constitute a solution to crisis? International Journal of Economics and Finance 3: 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bassiouny, Noha. 2014. The one-billion-plus marginalization: Toward a scholarly understanding of Islamic consumers. Journal of Business Research 67: 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeck, Matt, and Evangellos-Vagelis Dedoussis. 2010. Arabian Gulf innovator attitudes for online Islamic bank marketing strategy. Journal of Islamic Marketing 1: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Galfy, Ahmed, and Abdalla Khiyar. 2012. Islamic banking and economic growth: A review. Journal of Applied Business Research 28: 943–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estiri, Mehrdad, Farshid Hosseini, Hamidreza Yazdani, and Hooman Javidan Nejad. 2011. Determinants of customer satisfaction in Islamic banking: Evidence from Iran. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 4: 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, Morteza. 2019. Contributing factors on the allocation of funds in the Islamic society. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 1074–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Eddy. 2014. Islamic finance in global markets: Materialism, ideas and the construction of financial knowledge. Review of International Political Economy 21: 1170–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Eddy. 2016. Three decades of “repackaging” Islamic finance in international markets. Journal of Islamic Marketing 7: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Neil. 2012. The rise and rise of Islamic finance. African Banker, September 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard, Philip, and Barton Cunningham. 1997. Islamic banking: A study in Singapore. International Journal of Bank Marketing 15: 204–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Arieh, and Hyiel Hino. 2005. Supermarkets vs. traditional retail stores: Diagnosing the barriers to supermarkets’ market share growth in an ethnic minority community. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 12: 273–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, Sonya, and Rohit Deshpandé. 2001. Social dimensions of consumer distinctiveness: The influence of social status on group identify and advertising persuasion. Journal of Marketing Research 38: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, Mohammad, and Toeman Duman. 2014. A Comparison of Interest-Free and Interest-Based Microfinance in Bosnia and Herzegovina. European Researcher 79: 1333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Abdul, M. Shabri Abd Majid, and Lilis Khairunnisah. 2017. An empirical re-examination of the Islamic banking performance in Indonesia. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences 6: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Chris. 2012. Could India allow offshore Islamic bonds? Asia Money, November 4. [Google Scholar]

- Haron, Sudin, Norafifah Ahmad, and Sandra L. Planisek. 1994. Bank patronage factors of Muslim and non-Muslim customers. International Journal of Bank Marketing 12: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Kabir, Benito Sanchez, and M. Faisal Safa. 2013. Impact of financial liberalization and foreign bank entry on Islamic banking performance. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 6: 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Mohammad Enamul, Nik Mohd Hazrul Nik Hashim, and Mohammad Hafizi Bin Azmi. 2018. Moderating effects of marketing communication and financial consideration on customer attitu de and intention to purchase Islamic banking products. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Mohammed, and Shirley Leo. 2009. Customer perception on service quality in retail banking in Middle East: The case of Qatar. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 2: 338–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Mareem. 2014. Performance and potential of Islamic finance: A contextual study in the UK. Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies 7: 441–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Kassim. 2010. Bank-level stability factors and consumer confidence—A comparative study of Islamic and conventional banks’ product mix. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 15: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFSB. 2018. Financial Services Industry Stability Report. The Islamic Financial Services Board. Available online: https://www.ifsb.org/download.php?id=4811&lang=English&pg=/index.php (accessed on 14 December 2019).

- Imran, Muhammad, Shahzad Abdul Samad, and Rass Masood. 2011. Awareness level of Islamic banking in Pakistan’s two largest cities. Journal of Managerial Science 5: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, John. 2018. Just how loyal are Islamic banking customers? The International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 410–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Jamidul, and Zillur Rahman. 2017. Awareness and willingness towards Islamic banking among Muslims: An Indian perspective. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 10: 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Yogesh. 2013. Financial services sector at the center stage of Indian economy: Opportunities and challenges. Asia Pacific Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research 2: 209–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, Ahmad. 2003. Marketing in a multicultural world: The interplay of marketing, ethnicity and consumption. European Journal of Marketing 37: 1599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Ahmad, and Syadiyah Abdul Shukor. 2014. Antecedents and outcomes of interpersonal influences and the role of acculturation: The case of young British-Muslims. Journal of Business Research 67: 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, Ahmad, Sue Peattie, and Ken Peattie. 2012. Ethnic minority consumers’ responses to sales promotions in the packaged food market. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 19: 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddin, Nasiruddin. 2013. Marketing of shariah-based financial products and investments in India. Management Research Review 36: 417–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janahi, Muhamed Abdulnaser, and Muneer Mohamed Saeed Al Mubarak. 2017. The impact of customer service quality on customer satisfaction in Islamic banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabachi, Souheila, and Hassan Obeid. 2016. Determinants of Islamic banking adoption in Tunisia: Empirical analysis. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 34: 1069–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakeh, Abdulkader, Kabir Hassan, and Stefan van Hemmen Almazor. 2018. Attitude of Muslim minority in Spain towards Islamic finance. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 11: 213–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, Ahmad, and Saima Ahmad. 2010. Bankers’ perception towards bai salam method for agriculture financing in Pakistan. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 15: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbhari, Yusuf, Kamla Naser, and Zerrin Shahin. 2004. Problems and challenges facing the Islamic banking system in the West: The case of the UK. Thunderbird International Business Review 46: 521–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafafa, Ali Joma, and Zurina Shafii. 2013. Measuring the perceived service quality and customer satisfaction in Islamic bank windows in Libya based on structural equation modelling (SEM). Afro Eurasian Studies 2: 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq, Ahmad, Ghulam Ali Rustam, and Michael Dent. 2011. Brand preference in Islamic banking. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2: 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Omar. 2004. A proposed introduction of Islamic banking in India. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services 5: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Hajera Fatima. 2017. Islamic banking: On its way to globalization. International Journal of Management Research and Reviews 7: 1006–14. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Mansoor, and Ishaq Bhatti. 2008a. Islamic banking and finance: On its way to globalization. Managerial Finance 34: 708–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Mansoor, and Ishaq Bhatti. 2008b. Development in Islamic banking: A financial risk-allocation approach. The Journal of Risk Finance 9: 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Mohammad Saif Noman, Kabir Hassan, and Abdullah Ibneyy Shahid. 2007. Banking behavior of Islamic bank customers in Bangladesh. Journal of Islamic Economics, Banking and Finance 3: 159–94. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Muhammad Asif, Muhammad AfaqHaider, Shujahat Haidar Hashemi, and Muhammad Atif Khan. 2017. Islamic finance service industry and contemporary challenges: A literature outlook (1987–2016). Marketing and Branding Research 4: 310–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Naveed Azeem, and Kashifur Rehman. 2010. Customer satisfaction and awareness of Islamic banking system in Pakistan. African Journal of Business Management 4: 662–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kholvadia, Fatima. 2017. Islamic banking in South Africa—Form over substance? Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, Cem, and Önder Özgür. 2017. Is there a link between profit share rate of participation banks and interest rate? The case of Turkey. Journal of Economic Cooperation & Development 38: 135–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Kiran, and Bhawna Sahu. 2017. Dynamic linkages between macroeconomic factors and Islamic stock indices in a non-Islamic country India. Journal of Developing Areas 51: 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpad, Meenakshi Ramesh. 2016. Making a case for Islamic finance in India. Law & Financial Markets Review 10: 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Karen, and Michael Samers. 2017. Conceptualizing Islamic banking and finance: A comparison of its development and governance in Malaysia and Singapore. Pacific Review 30: 405–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, Mark. 2010. Attitudes and perceptions towards Islamic banking among Muslims and non-Muslims in Malaysia: Implications for marketing to baby boomers and X-generation. International Journal of Arts and Sciences 3: 453–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ltifi, Moez, Lubica Hikkerova, Boualem Aliouat, and Jameleddine Gharbi. 2016. The determinants of the choice of Islamic banks in Tunisia. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 34: 710–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Richard K., Jennifer A. Chatman, and Caneel K. Joyce. 2007. Innovation in services: Corporate culture and investment banking. California Management Review 50: 174–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdzan, Nurul Shahnaz, Rozaimah Zainudin, and Sook Fong Au. 2017. The adoption of Islamic banking services in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, Jihed, and Salim Ben Sassi. 2017. Volatility spillover and hedging effectiveness among China and emerging Asian Islamic equity indexes. Emerging Markets Review 31: 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Muhammad Shaukat, Ali Malik, and Waqas Mustafa. 2011. Controversies that make Islamic banking controversial: An analysis of issues and challenges. American Journal of Social and Management Sciences 2: 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehree, Iqbal, Nabila Nisha, and Mamunur Rashid. 2018. Bank selection criteria and satisfaction of retail customers of Islamic banks in Bangladesh. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 931–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mehtab, Humna, Zafar Zaheer, and Shahid Ali. 2015. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) Survey: A Case Study on Islamic Banking at Peshawar, Pakistan. FWU Journal of Social Sciences 9: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, Abdul Malik, and Abdel-Karim Halabi. 2003. Islamic banking in Australia: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 23: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohan, Brij. 2014. Islamic Banking: Importance, growth and future with special reference to Indian economy. International Journal in Management & Social Science 2: 286–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Thas Thaker, Mohamed Asmy Bin, Anwar Bin Allah Pitchay, Hassanudin Bin Mohd Thas Thaker, and Md Fouad BinAmin. 2019. Factors influencing consumers’ adoption of Islamic mobile banking services in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 1037–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktar, Hamim S. Ahmad, Naziruddin Abdullah, and Syed M. Al-Habshi. 2006. Efficiency of Islamic banks in Malaysia: A stochastic frontier approach. Journal of Economic Cooperation among Islamic Countries 27: 37–70. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, Mohsin Butt, and Muhammad Aftab. 2013. Incorporating attitude towards halal banking in an integrated service quality, satisfaction, trust and loyalty model in online Islamic banking context. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 31: 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, Paresh Kumar, and Dinh Hoang Bach Phan. 2019. A survey of Islamic banking and finance literature: Issues, challenges and future directions. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 53: 484–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, Kamal, and Luiz Moutinho. 1997. Strategic marketing management: The case of Islamic banks. International Journal of Bank Marketing 15: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, Kamal, Ahmad Jamal, and Khalid Al-Katib. 1999. Islamic banking: A study of customer satisfaction and preferences in Jordan. International Journal of Bank Marketing 17: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, Saduman. 2005. Interest free banking in Turkey: A study of customer satisfaction and bank selection criteria. Journal of Economic Cooperation 26: 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- Opromolla, Gabriella. 2012. Islamic finance: What concrete steps is Italy taking? The Journal of Investment Compliance 13: 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, Ismah, Husniyati Ali, Anizah Zainuddin, Wan Edura Wan Rashid, and Kamaruzaman Jusoff. 2009. Customers satisfaction in Malaysian Islamic banking. International Journal of Economics and Finance 1: 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oullet, Jean-Fracois. 2007. Consumer racism and its effects on domestic cross-ethnic product purchase: An empirical test in the United States, Canada, and France. Journal of Marketing 71: 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penaloza, Lisa, and Mary Gilly. 1999. Marketer acculturation: The changer and the changed. Journal of Marketing 63: 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracci, Barbara, and Hussain Rammal. 2014. Developing the Islamic financial services sector in Italy: An institutional theory perspective. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 19: 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potluri, Rajasekhara, Rizwana Ansari, Saqib Rasool Khan, and Srinisava Rao Dasaraju. 2017. A crystallized exposition on Indian Muslims’ attitude and consciousness towards halal. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammal, Hussain, and Ralf Zurbruegg. 2007. Awareness of Islamic banking products among Muslims: The case of Australia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 12: 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Edana. 2011. Islamic Finance for Consumers in Ireland: A Comparative Study of the Position of Retail-level Islamic Finance in Ireland. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 31: 534–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosly, Saiful Azhar, and Mohd Afandi Abu Bakar. 2003. Performance of Islamic and mainstream banks in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Economics 30: 1249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiti, Buerhan, and Munsur Masih. 2016. The co-movement of selective conventional and Islamic stock indices: Is there any impact on shariah compliant equity investment in china? International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6: 1895–905. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, Md Abu, Ali Quazi, Byron Keating, and Sanjaya S. Gaur. 2017. Quality and image of banking services: A comparative study of conventional and Islamic banks. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 35: 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, Abdus. 1999. Comparative efficiency of the Islamic Bank Malaysia vis-à-vis conventional banks. Journal of Economics and Management 7: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, Md Abdul Awwal. 1999. Islamic banking in Bangladesh: Performance, problems and prospects. International Journal of Islamic Financial Services 1: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Alex Paton. 2019. The impact of cognitive style, consumer demographics and cultural values on the acceptance of Islamic insurance products among American consumers. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 37: 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottmann, Sven Alexander. 2014. From duty to choice: Marketing Islamic banking in Malaysia. South East Asia Research 22: 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, Jagdish. 2011. Impact of emerging markets on marketing: Rethinking existing perspectives and practices. Journal of Marketing 75: 166–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyobudi, Wahyu, Sudarso Kaderi Wiryono, Reza Ashari Nasution, and Mustika Sufiati Purwanegara. 2016. The efficacy of the model of goal directed behavior in explaining Islamic bank saving. Journal of Islamic Marketing 7: 405–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokuhi, Akbar, and Seyed Ali Nabavi Chashmi. 2019. Formulation of Bank Melli Iran marketing strategy based on Porter’s competitive strategy. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 26: 209–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, Nizar, and Marzouki Rani. 2015. Consumer attitudes and purchase intentions toward Islamic banks: The influence of religiosity. International Journal of Bank Marketing 33: 143–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srairi, Samir Abderrazek. 2010. Cost and profit efficiency of conventional and Islamic banks in GCC countries. Journal of Productivity Analysis 34: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. 2016. Community Survey 2016 in Brief; Report Number 03-01-06; Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Sufian, Fadzlan. 2010. Productivity, technology and efficiency of de novo Islamic banks: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 15: 241–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, Dwi. 2019. Predicting behavioural intention toward Islamic bank: A multi-group analysis approach. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 1091–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tameme, Mohammed, and Mehmet Asutay. 2012. An empirical inquiry into marketing Islamic mortgages in the UK. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 30: 150–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Michael. 2003. Islamic banking—The feasibility of establishing an Islamic bank in the United States. American Business Law Journal 40: 385–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakic, Adnan. 2012. Europe’s approach to Islamic banking: A way forward. Journal of Islamic Finance and Business Research 1: 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Md Mahi, Mohammad Aktaruzzaman Khan, and Kazi Deen Mohammad. 2015. Interest-Free Banking in Bangladesh: A Study on Customers’ Perception of Uses and Awareness. Abasyn University Journal of Social Sciences 8: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, Haridus, Prijono Tjiptoherijanto, Tengku Ezni Balqiah, and I. Gusti Ngurah. 2017. The role of religious norms, trust, importance of attributes and information sources in the relationship between religiosity and selection of the Islamic bank. Journal of Islamic Marketing 8: 158–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahed, Goolam, and Shahid Vawda. 2008. The viability of Islamic banking and finance in a capitalist economy: A South African case study. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 28: 453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, Stefan, and Markus Pudelko. 2010. Challenges and opportunities for Islamic retail banking in the European context: Lessons to be learnt from a British–German comparison. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 15: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, Davina, Lee Martin, Stacey Fitzsimmons, Andre Pekerti, C. Lakshman, and Salma Raheem. 2019. Multiculturalism within Individuals: A review, critique, and agenda for future research. Journal of International Business Studies 50: 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajdi Dusuki, Asyraf, and Nurdianati Irwani Abdullah. 2007. Why do Malaysian customers patronize Islamic banks? International Journal of Bank Marketing 25: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Ahmad, Wan Marhaini, Mohamed Hisham Hanifa, and Kang Choon Hyo. 2019. Are non-Muslims willing to patronize Islamic financial services? Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 743–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsame, Mohammed Hersi, and Edward Mugambi Ireri. 2018. Moderation effect on Islamic banking preferences in UAE. The International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Jonathan, and Jonathan Liu. 2011. The challenges of Islamic branding: Navigating emotions and halal. Journal of Islamic Marketing 2: 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebal, Mostaue Ahmad. 2018. The impact of internal and external market orientation on the performance of non-conventional Islamic financial institutions. Journal of Islamic Marketing 9: 132–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).