Simple Summary

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) is a type of chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR T)-cell therapy approved in Canada to treat adults with relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma, which is usually associated with a poor prognosis. In this retrospective study, we analyzed data from a large national registry database to evaluate the real-world effectiveness and safety outcomes of axi-cel across multiple Canadian centres. Our findings demonstrated that the effectiveness of axi-cel was comparable to those reported in clinical trial and real-world studies, with lower rates of adverse events. These findings support the ongoing use of axi-cel for the treatment of R/R LBCL in Canada.

Abstract

CD19 CAR T-cell therapy has significantly improved the survival of patients with relapsed or refractory large B cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL) and is considered standard of care for eligible patients in Canada. Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) is an autologous CAR T-cell therapy, initially approved by Health Canada for adults with R/R LBCL after 2 or more lines of therapy. This multi-centre analysis, with registry data collected from CIBMTR, aims to present a Canadian perspective on the real-world experience of axi-cel in patients with R/R LBCL. With a median follow-up of 12.4 months, the best objective response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) rate among all patients were 77% and 59%, respectively. At 12 months, estimated progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 49% and 59%, respectively. Notably, the incidence and severity of adverse events were lower in this cohort compared to ZUMA-1 and other real-world reports, with CRS occurring in 77% (grade ≥ 3, 3%) and ICANS occurring in 38% (grade ≥ 3, 10%) of patients. Outcomes remained largely consistent across patient and disease characteristics. These findings demonstrate effectiveness and safety profiles comparable to international real-world studies and the ZUMA-1 trial, supporting the use of axi-cel as an effective treatment across broad Canadian populations.

1. Introduction

The advent of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a revolutionary cancer immunotherapy, has offered transformative outcomes for patients with a variety of hematological malignancies, including those with relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL). These patients have typically had a very poor prognosis with a median overall survival (OS) of 6.3 months and an objective response rate (ORR) of 26% despite salvage chemotherapy and other interventions [1].

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) is an autologous anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, which was approved by Health Canada in February 2019 for the treatment of adult patients with R/R LBCL after two or more lines of systemic therapy, including DLBCL not otherwise specified, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBL), and DLBCL arising from follicular lymphoma [2]. The approval was based on the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial, which demonstrated that axi-cel offers a high ORR at 83% and complete response (CR) rate of 58% in adults with refractory LBCL [3]. In a 5-year follow-up analysis of the trial, median OS was reported at 25.8 months, with an estimated disease-specific survival of 51.0% at 5 years, demonstrating its curative potential [4]. Furthermore, in March 2023, the findings of the ZUMA-7 trial resulted in the approval of axi-cel in the second-line setting, specifically in patients with DLBCL or HGBL that is refractory to or that relapses within 12 months of first-line chemoimmunotherapy [2,5].

While the clinical trial data demonstrate impressive effectiveness outcomes, real-world evidence is needed to validate the effectiveness and safety of CAR T-cell therapy in broader patient populations, where eligibility criteria and monitoring are less controlled. Multiple real-world studies evaluated the use of axi-cel in patients with R/R LBCL [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Several US real-world studies have reported comparable effectiveness and safety outcomes of axi-cel to pivotal trials, despite large proportions of patients (43–57%) who would have been ineligible for ZUMA-1 [6,7]. Similarly, a national real-world study from the UK also demonstrated consistent effectiveness and a reduced trend of adverse events (AEs) over time, due to improved patient monitoring and better supportive care [9]. The GLA/DRST real-world data also further confirmed the real-world effectiveness and safety of axi-cel in a German R/R LBCL cohort [11].

In Canada, several single-centre studies have described their initial experience with toxicity and effectiveness outcomes of axi-cel comparable to the pivotal trials and international real-world data [12,13,14,15]. These studies highlight that, despite the complexity in administrating CAR T-cell therapy, and large referral catchment area or geography, patients can be effectively treated across Canada. These publications also highlight some of the challenges in access to CAR T-cell therapy, including radiation bridging therapy as a modality to achieve disease control and impact of travel distance on timely CAR T cell infusion [12,15,16]. In contrast to the US and Europe, Canada currently lacks studies to assess outcomes across the broader Canadian population.

Here, we aim to characterize the real-world effectiveness and safety of axi-cel in patients with R/R LBCL treated across Canadian CAR T centres in third- and later-line settings and provide a national perspective on the Canadian experience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This registry-based, noninterventional cohort study is a secondary use of real-world data from the observational database of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR®, Milwaukee, WI, USA) registry in collaboration with Cell Therapy Transplant Canada (CTTC) for adult patients (≥18 years) receiving commercial axi-cel for R/R LBCL between February 2020 and June 2023 in Canada (data cut-off 1 October 2024). Patients who died or discontinued prior to data cut-off were also included. All patients provided informed consent for participation in the CIBMTR for research studies, and the use of data for research was approved and overseen by the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) central institutional review board.

Information on patient, treatment and disease characteristics were reported by participating treatment centres at the time of axi-cel infusion, along with follow-up forms for 100-day, 6 months and then annually following infusion. Eligible patients must also have had both pre-infusion and at least 100-day follow-up data available. Data reporting requirements are further described in Supplemental Materials.

2.2. Treatment and Endpoint Assessments

Effectiveness endpoints assessed included ORR, CR rate, partial response (PR) rate, time to overall response (TTOR), time to complete response (TTCR), duration of response (DOR), duration of complete response (DOCR), progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and relapse or progressive disease (REL/PD). Disease response was assessed according to the Lugano classification scheme [5]. Relapse and disease progression were determined by the investigator at the treatment centre.

These endpoints were defined as follows: TTOR—Time from date of infusion to the initial response for subjects with PR or CR as best response. Post-infusion REL/PD or death were treated as competing risk events. TTCR—Time from date of infusion to initial response of CR, for subjects with CR as best response. DOR—Time from first CR or PR to REL/PD through radiological and/or clinical assessment, or death due to any causes (i.e., PFS since initial response as CR/PR) (only applies to subjects with CR (including CCR) or PR as best response). DOCR—Time from first CR to REL/PD through radiological and/or clinical assessment, or death due to any causes (i.e., PFS since initial response as CR) (only applies to subjects with CR (including CCR) as best response). PFS—Time from the first axi-cel infusion to the earliest documented REL/RD through imaging assessment (CT, PET, MRI) and/or clinical/hematologic assessment (including pathology and laboratory assessment, as well as physical examination) or death due to any cause. OS—Time from the first axi-cel infusion to death due to any cause. REL/PD—Time from the first axi-cel infusion to earliest documented REL/PD through imaging assessment (CT, PET, MRI) and/or clinical/hematologic assessment (including pathology and laboratory assessment, as well as physical examination).

Safety outcomes assessed were CRS and ICANS as per grading by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus criteria [17], prolonged cytopenia (those failed to resolve within the first 30 days after infusion), clinically significant infections (diagnosed after the initial infusion of axi-cel that requires treatment), and non-relapse mortality (NRM).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Dichotomous outcomes (ORR, CR rate, PR rate, CRS, ICANS, prolonged cytopenia, clinically relevant infections, and time from infusion to infection) were summarized using percentages with 95% Clopper–Pearson confidence intervals. Time to event outcomes without competing risk (DOR, DOCR, PFS, OS) were summarized using the Kaplan–Meier estimator. Time to event outcomes with competing risk (TTOR, TTCR, REL/PD, NRM) were summarized using the cumulative incidence function. Reported p-values were two-sided, with a p-value of <0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software, version 9.4 M8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patients

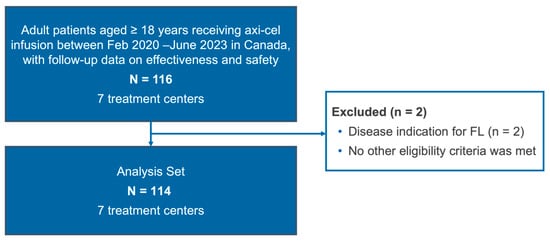

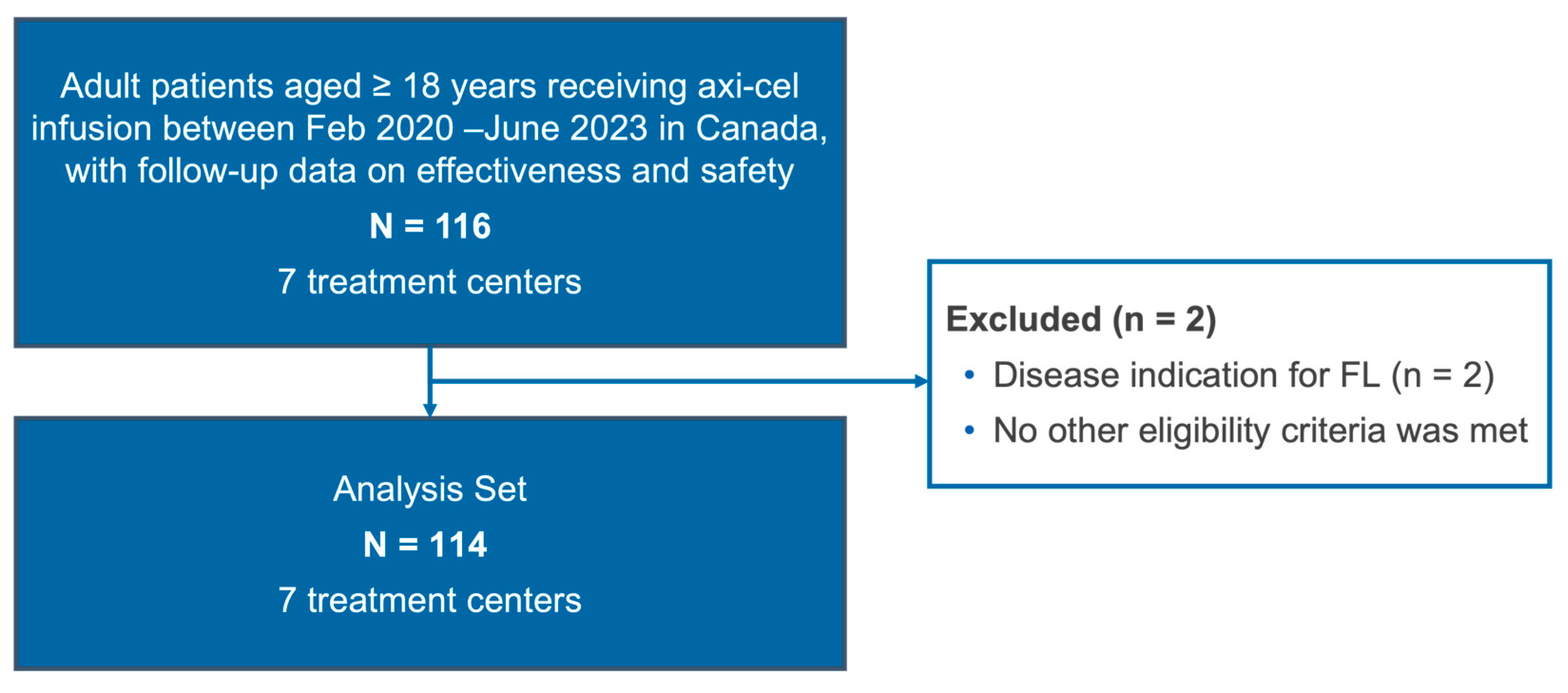

A total of 114 eligible patients were identified in the CIBMTR registry (Appendix A, Figure A1). At the time of data cut-off (1 October 2024), the median follow-up was 12.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.1–13.0). Patients were treated across 7 CAR T treatment centres. The median age of the patients was 63 years (range 20–81; 39% ≥ 65 years and 11% ≥ 75 years), and 67% were male (Table 1). The majority of the patients (94%) demonstrated a baseline ECOG performance score of 0 or 1, and clinically significant co-morbidities were present in 64% of patients (Table 1). Approximately, one-third (34%) of the patients would have been ineligible for ZUMA-1, mainly due to organ impairment (Appendix B, Table A1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics.

At initial diagnosis, histology subtypes included 92 diffuse LBCL (81%), 17 high-grade BCL (15%), 4 primary mediastinal BCL (4%), and 1 monomorphic PTLD (<1%). The majority of patients (77%) were diagnosed with stage III or IV disease, and 81% of the patients had extranodal involvement. Prior to infusion, approximately half of the patients (54%) demonstrated elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. Among patients with reported parameters to calculate CAR-HEMATOTOX score (n = 61), the majority (70%) of the patients had a score of 2+, indicating higher risk of CAR T-cell-related hematotoxicity [19]. Most (98%) of the patients presented non-bulky disease, with extranodal involvement being observed in 56% of the patients. Patients had received a median of 3 prior lines of therapy (IQR, 2–4), and 30% received autologous HCT. In addition, 40% of patients were treated with axi-cel within 12 months of initial disease diagnosis. Prior to leukapheresis, 81% of the patients were refractory after last line of therapy. Median time from leukapheresis to infusion was 32 days (IQR, 28–34), during which 51 patients (52%) received bridging therapy (35% systemic, 34% radiation). Among patients who received bridging therapy with reported response data, 9% and 41% achieved a CR and PR, respectively.

3.2. Effectiveness

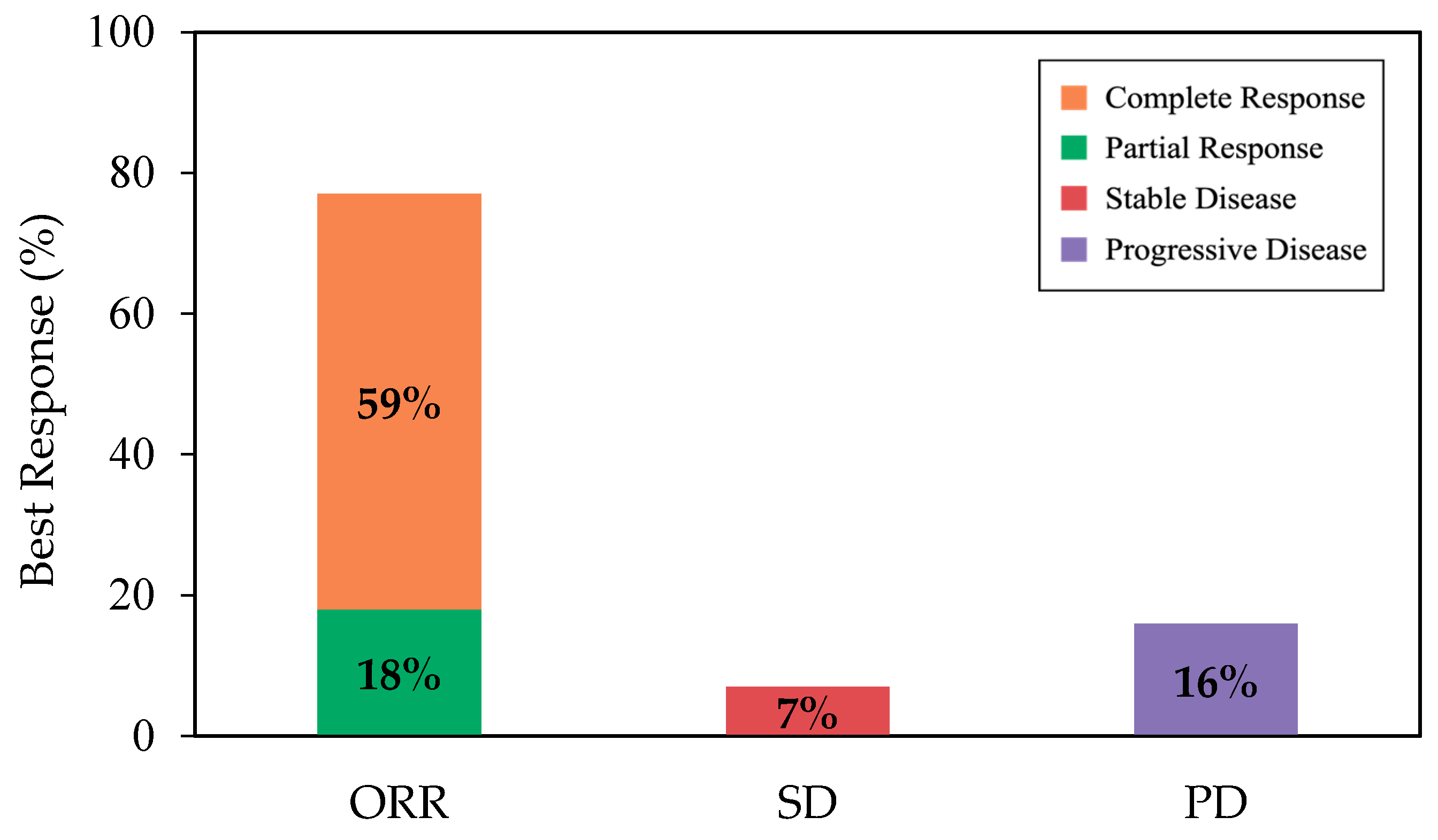

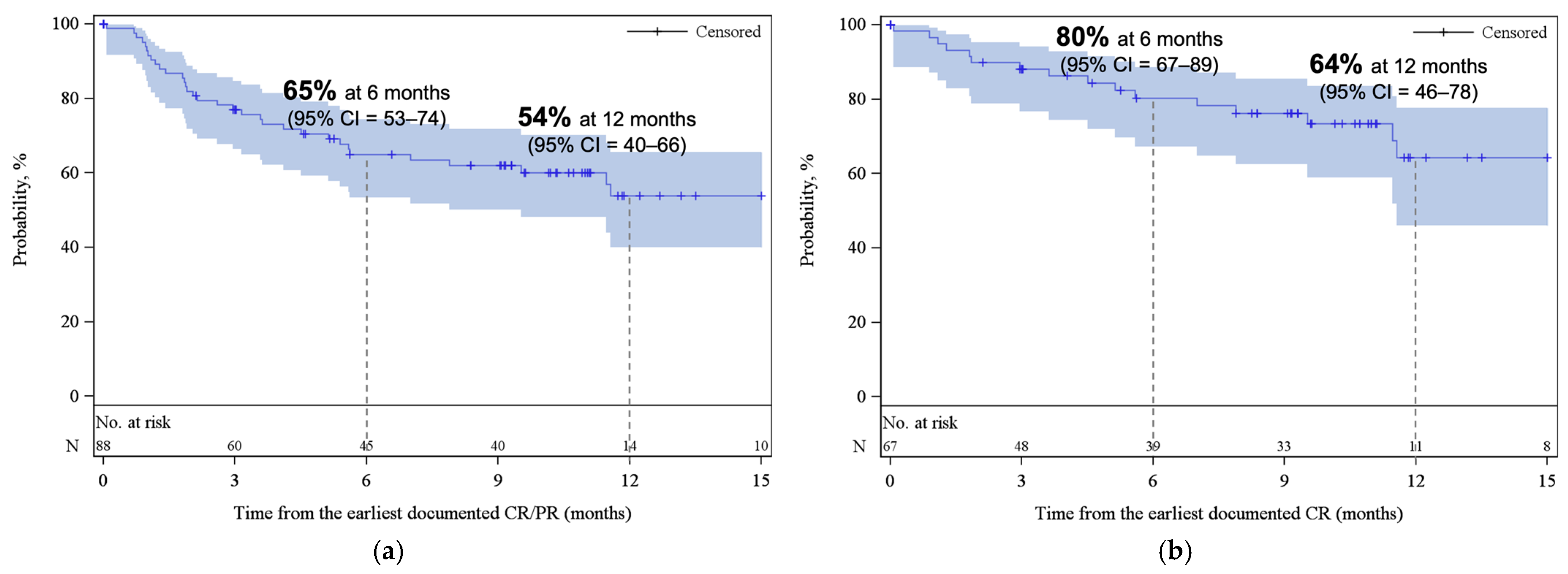

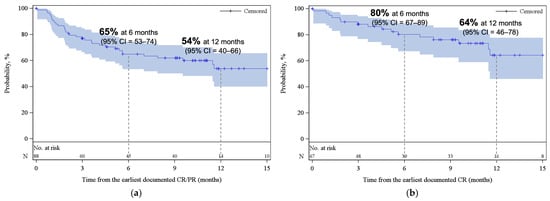

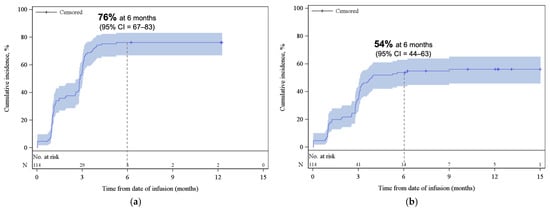

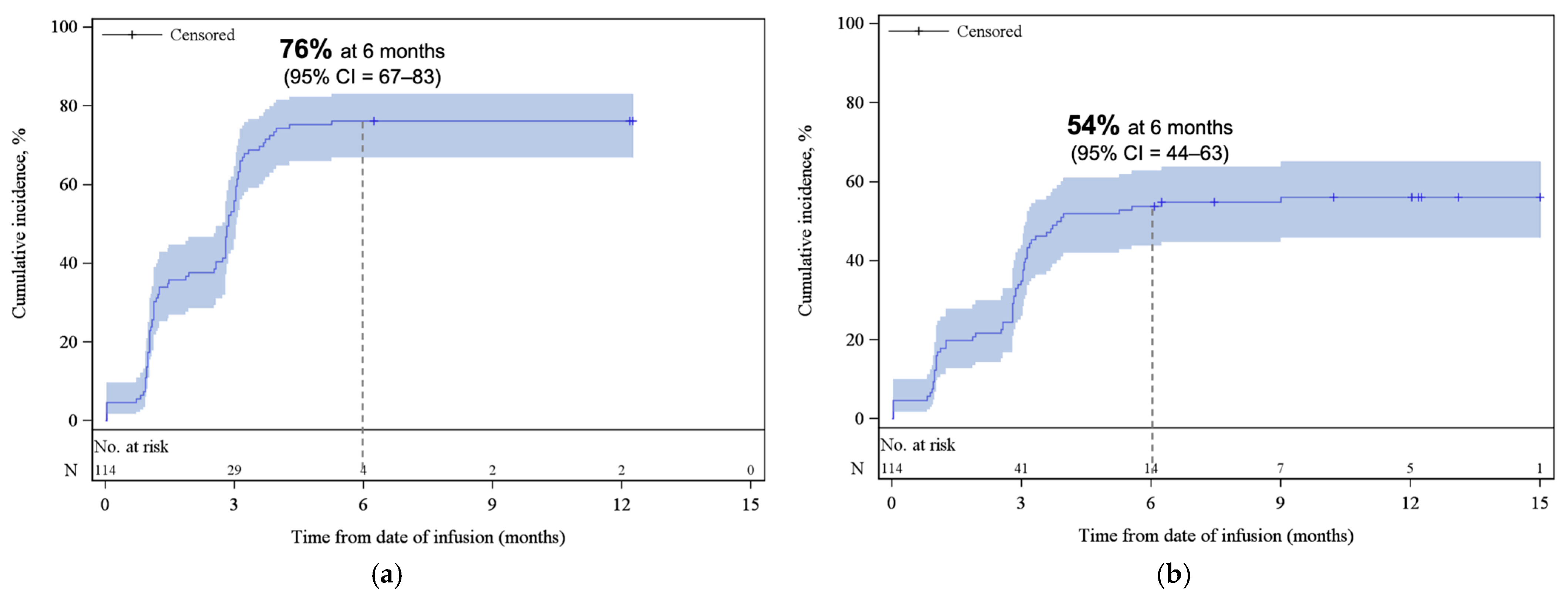

With a median follow-up of 12.4 months from infusion, the best ORR and CR among all patients were 77% (95% CI, 68–85) and 59% (95% CI, 49–68), respectively (Figure 1). Cumulative incidences of ORR and CR at 6 months were 76% (95% CI, 67–83) and 54% (95% CI, 44–63), respectively (Appendix A, Figure A2). While the median DOR was not reached, among responders, 65% (95% CI, 53–74) and 54% (95% CI, 40–66) remained in response for 6 months and 12 months, respectively (Figure 2a). Among patients who achieved CR, 80% (95% CI, 67–89) and 64% (95% CI, 46–78) remained in response for ≥6 months and 12 months, respectively (Figure 2b).

Figure 1.

The rate of best ORR (as complete response + partial response), SD, and PD, among all patients. Abbreviations: ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for duration of response (a) among patients who achieved CR/PR as best response and (b) among patients who achieved CR as best response. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated DOR at 6 and 12 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

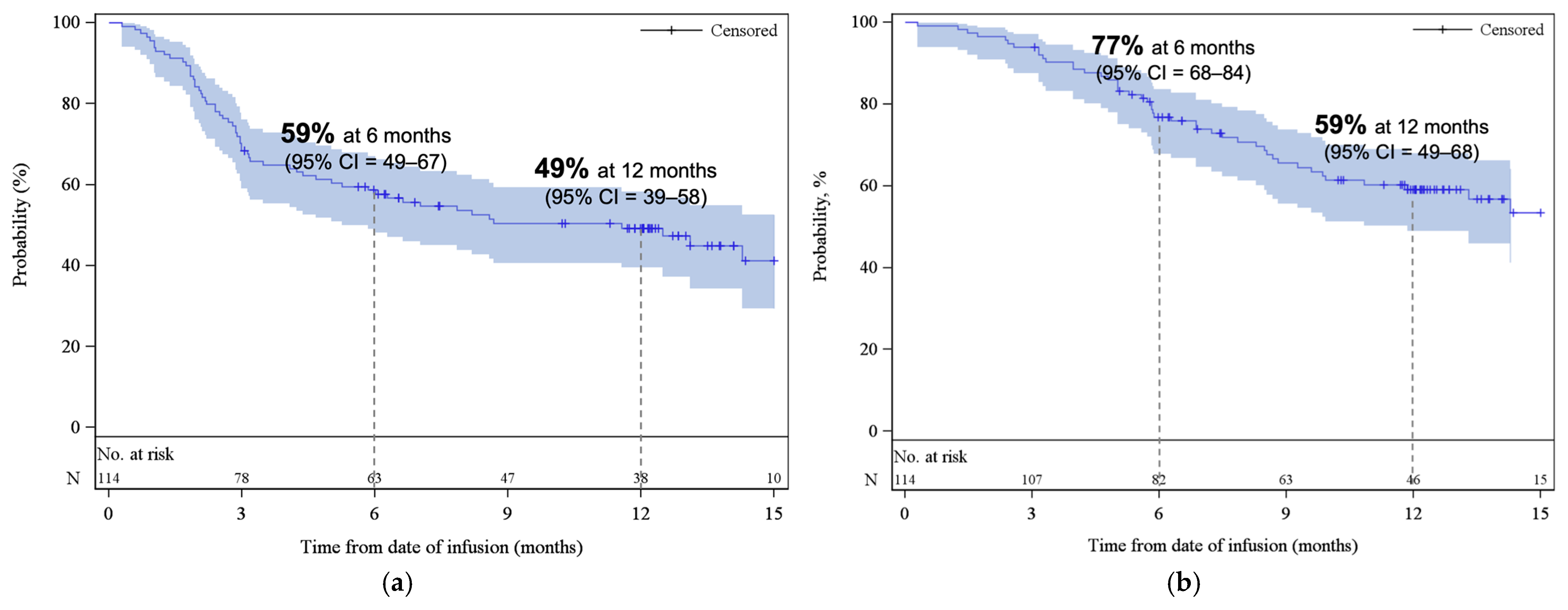

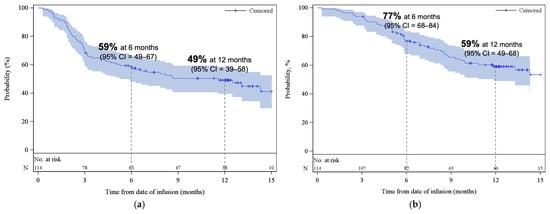

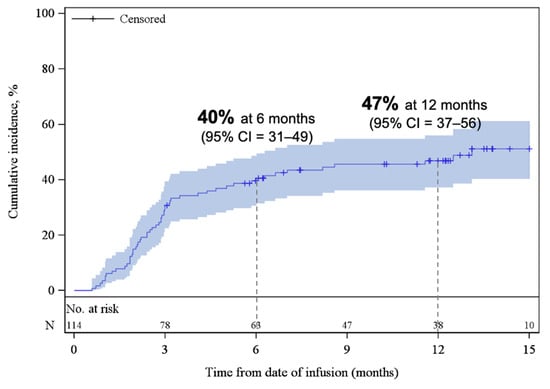

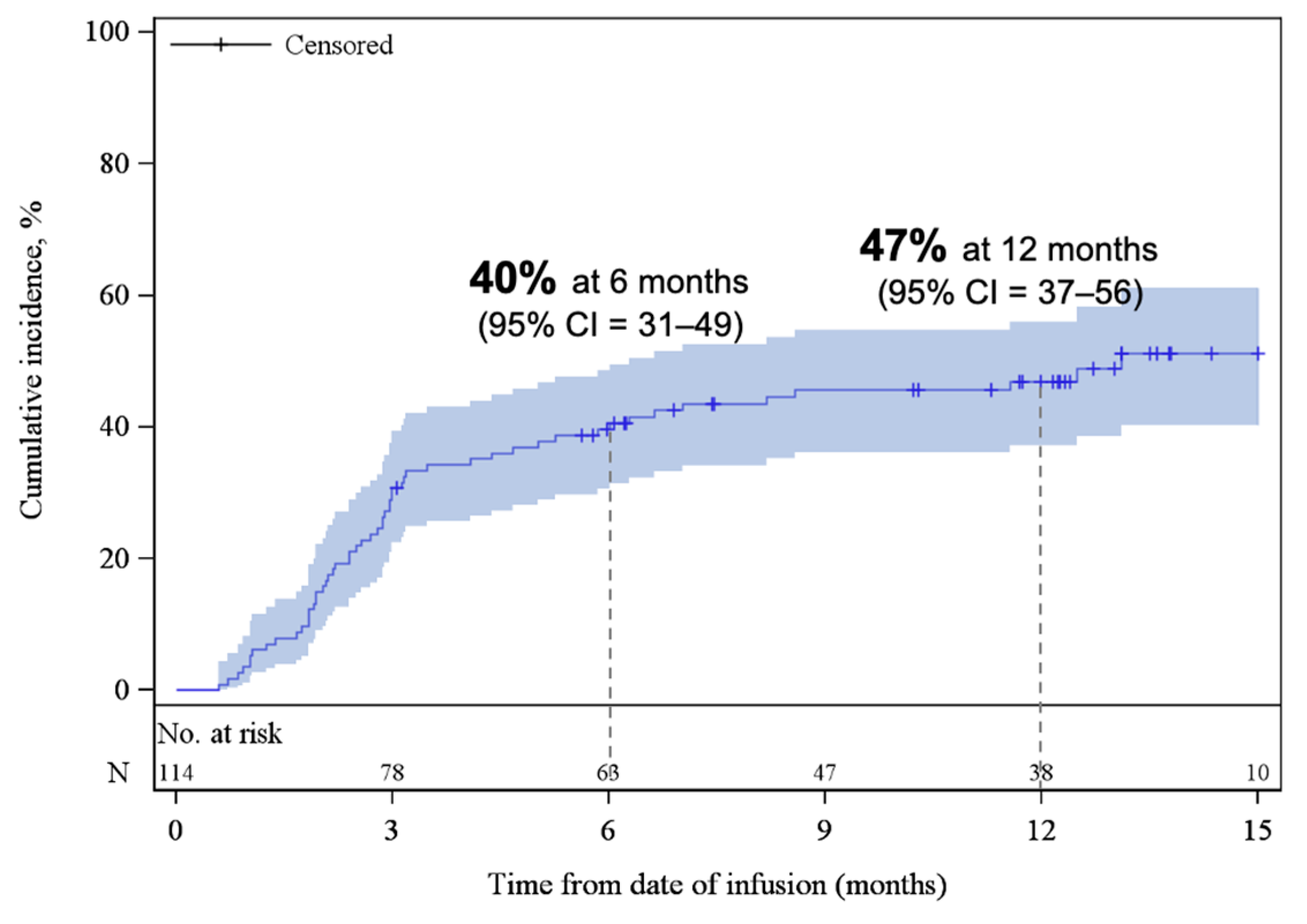

The median PFS was 11.6 months (95% CI, 5.3–NE), with estimated PFS rates of 59% (95% CI, 49–67) at 6 months and 49% (95% CI, 39–58) at 12 months (Figure 3a). The median OS was 18.2 months (95% CI, 11.9–NE), with estimated OS rates of 77% (95% CI, 68–84) at 6 months and 59% (95% CI, 49–68) at 12 months (Figure 3b). At the time of data cut-off, 59% of patients remained alive. At 3 and 6 months, the cumulative incidence of REL/PD were 31% (95% CI, 22–39) and 40% (95% CI, 31–49), respectively (Appendix A, Figure A3). The response rates and survival rates were largely consistent across subgroups of key baseline and disease characteristics, including HCT-CI index, and age at infusion (Supplemental Table S1). Only ECOG PS of ≥2 appeared to be associated with inferior outcomes; however, this subgroup contained a small number of patients (n = 7).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of (a) progression-free survival and (b) overall survival. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated (a) PFS and (b) OS at 6 and 12 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

3.3. Safety

Among patients with reported data, CRS occurred in 77% of patients (95% CI, 68–85), with grade ≥ 3 events in 3 patients (3%) and no reported cases of Grade 4 or higher CRS (Table 2). The median time from infusion to the onset of CRS was 4 days (IQR, 2–6), and median time from onset to resolution was 5 days (IQR, 4–8).

Table 2.

Safety outcomes.

Neurotoxicity occurred in 38% of patients (95% CI, 29–48), with ICANS Grade ≥ 3 occurring in 10% patients and no reported cases of Grade 4 or higher ICANS. The median time from infusion to onset was 8 days (IQR, 6–8), and median time to resolution was 7 days (IQR, 4–9.5).

Of the 98 patients with complete data on both CRS and neurotoxicity, 72 patients (73%) were without CRS and ICANS at Day 14 and beyond, including patients whose toxicities resolved prior to Day 14 (48 patients, 49%), as well as patients without any onset of either CRS or neurotoxicity (24 patients, 24%). The remaining 26 patients either experienced ongoing CRS and/or neurotoxicities on Day 14 (23 patients; 23%) or had onset CRS or ICANS after Day 14 (3 patients; 3%). Among the three patients with CRS and/or ICANS onset after Day 14, two patients had CRS onset on Day 15, one with a maximum grade of 1 and the other a maximum grade of 2. One patient also experienced neurotoxicity onset on Day 15 with a maximum ICANS Grade of 3 and resolution of ICANS on Day 23. No specific patient or disease characteristic related to late-onset events was identified. Among patients experiencing CRS and/or ICANS (n = 87), 44% received corticosteroids, 85% received tocilizumab, and 5% received anakinra. Nearly all events associated with CRS were resolved, except for two cases ongoing at data cut-off. All ICANS events were fully resolved.

Prolonged cytopenia after Day 30 occurred in 17% of patients (12% neutropenia, 5% thrombocytopenia). Clinically significant infection that required treatment occurred in 46% of patients. Median time from infusion to infection was 0.9 months (25th to 75th percentile, 0.2–2.4). The occurrences of safety events remained largely consistent across different subgroups. NRM occurred in 2% (95% CI, <1–6) by month 6 and 4% (95% CI, 1–9) by month 12. Among all patients who received infusion, 47 patients (41%) died during follow-up; this was due to primary disease in 42 patients (89%), organ failure in 3 patients (6%; 2 pulmonary failures, 1 cardiac failure), and malignancy in 2 patients (4%) (Appendix B, Table A2). The safety outcomes remained largely consistent across various subgroups (Supplemental Table S2).

4. Discussion

This is the first multi-centre national registry study of patients on axi-cel for R/R LBCL in real-world settings in Canada. Our findings demonstrate an ORR of 77% and a CR rate of 59%, which are comparable to outcomes reported in the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial (ORR of 82%, CR rate of 54%) [3] and other real-world datasets, with CR rates ranging from 42 to 78% [6,9,11,12,13,14,15,20]. In particular, our findings strongly align with a Canadian single-centre study that reported a 12-month response rate of 72% with axi-cel [12]. In contrast, another Canadian single-centre study reported a poor early response rate (3-month ORR of 47% with axi-cel). This discrepancy may be attributed to the high prevalence of bulky disease in the patient cohort, which was identified as a strong predictor of poor early response [14]. The variability in efficacy across centres may be attributed to the small cohorts included in single-centre reports, which can increase variability, and heterogeneity in patient characteristics, particularly disease status at the time of infusion. Importantly, these outcomes were achieved despite 34% of the patients not meeting ZUMA-1 eligibility criteria, largely due to organ impairment. Additionally, 64% of patients presented clinically significant comorbidities, and 25% were 70 years or older, highlighting the robustness of axi-cel effectiveness in a broader patient population. Moreover, effectiveness outcomes were largely consistent across subgroups, including age and HCT-CI index at infusion, which further supports the finding that older patients and non-transplant-eligible patients can still benefit from axi-cel [21,22,23,24].

Overall, the incidence of CRS and ICANS observed in our study (77% and 38%, respectively) was largely consistent with those reported in the clinical trial and other real-world studies [3,6,7,9,10,11], although some variability was observed compared to other Canadian single-centre reports. In particular, the overall incidence of CRS and ICANS was lower than that reported in other Canadian single-centre studies [12,15,16]. The multi-centre nature of our study may potentially normalize centre-to-centre differences in patient selection and toxicity management, thereby providing a wider perspective of Canadian experiences with axi-cel. Importantly, the occurrences of grade ≥3 AEs (3% grade ≥3 CRS and 10% grade ≥3 ICANS) were markedly lower compared to the ZUMA-1 trial (11% grade ≥3 CRS and 32% grade ≥3 ICANS), which can be attributed to several factors. First, most institutions in the current study implemented an early toxicity management similar to the ZUMA-1 cohort 4, where patients received tocilizumab and/or corticosteroids earlier than the ZUMA-1 cohorts 1 and 2 [25]. This suggests that earlier toxicity intervention may reduce the severity and incidence of high-grade CRS/ICANS without compromising the effectiveness of axi-cel. In addition, unlike the ZUMA-1 trial, where bridging therapy was not permitted, approximately half (52%) of the patients in this study received bridging therapy, where systemic therapy and/or radiation were most frequently used. Among patients with reported data on response to bridging therapy, 50% achieved CR or PR as best response to bridging therapy. Previous studies suggest that response to bridging therapy is strongly correlated with more favourable CAR T outcomes [12,26,27], suggesting that disease control prior to axi-cel can improve the treatment-related toxicities seen in this study.

A small number of patients had onset of CRS or ICANS after Day 14 (3 out of 98 patients), which is consistent with recent real-world evidence looking at new-onset CRS/ICANS beyond Day 14 [28]. Furthermore, most patients (73%) did not experience CRS/ICANS symptoms at Day 14 and beyond. These data are notable given the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) decision to eliminate the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programme for autologous CAR T therapies [29]. The FDA no longer requires US CAR T treatment centres to be specially certified and has reduced the requirement for patients to remain within proximity of a healthcare facility from 4 weeks to 2 weeks. This may improve access to CAR T in the US and may be relevant to Canadian regulators as well.

Canada’s large geography and limited number of CAR T centres present various challenges to access, especially for patients treated outside of their province of residence or those from remote regions. In addition, shipping commercial CAR T products from the US to Canada may contribute to longer vein-to-vein time. While the median vein-to-time in our study was longer compared to the US CIMBTR report (32 days vs. 27 days), the majority of patients (87%) received infusion within <40 days after leukapheresis, a timeframe previously associated with favourable CAR T outcomes [5]. Interestingly, a study from the Ottawa CAR T centre reported that patients treated out-of-province experienced significantly longer times from relapse to referral compared to in-province patients (34 days vs. 9 days) [15]. However, the vein-to-vein time did not differ between the two groups, suggesting that inequality in timely access to CAR T in Canada may extend beyond vein-to-vein time. Multi-centre analyses are required to assess the impact of patient location on the timeline of axi-cel infusion and their outcomes.

There are several limitations to this study. Despite being a national registry, reporting to the CIBMTR/CTTC registry has not been nationally mandated; thus, not all authorized CAR T centres in Canada actively participated in reporting data. Specific CIBMTR reporting forms were required to be completed to ensure sufficient data capture for analysis. Despite this, data for various parameters remain incomplete, which may impact data interpretation. Increased resources and support are needed for data managers across Canadian sites to improve the completeness and accuracy of registry data. Another limitation within the CIBMTR datasets is that reoccurrences of safety events are not specifically captured. Whether CRS or ICANS recurs in the same patient after an initial resolution cannot be assessed. Whether the data reported here on the onset and resolution of these events represents the first instances only or includes recurrences in patients who experience them is also unclear. As such, the data on the number of patients who are without CRS or ICANS at Day 14 and beyond should be interpreted with caution. Recent data from several axi-cel clinical trials suggest that in patients who have durable remission of CRS/ICANS, defined as 3 consecutive days, the risk of recurrence is low [30].

This report focuses on third-line patients who were refractory to, or had relapsed after, two or more prior lines of systemic therapy. Prior to the approval of CAR T-cell therapy in second-line, patients who were refractory to or relapsed within 12 months of first-line therapy who responded to second line salvage chemotherapy would have proceeded to the standard second-line approach of high-dose therapy, followed by autologous SCT. Consequently, CAR T-cell therapy would have been administered only after a patient was unable to proceed to transplant (e.g., did not achieve a response to salvage or not eligible for transplant) or had relapsed following transplant. Therefore, no comparison between CAR T-cell therapy versus autologous SCT could be performed in this study. Notably, 30% of patients in this cohort had received a prior autologous transplant, as shown in Table 1.

The treatment landscape for R/R LBCL is rapidly evolving with the introduction of additional treatment options, such as bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) and CAR T treatment in earlier lines of therapy [31,32]. As of this report, second-line axi-cel is available in Canada. However, during the infusion period of data reporting, there was no access to axi-cel in the second-line setting. The ZUMA-7 trial demonstrated that axi-cel significantly improves EFS, response rates, and OS compared to standard care (chemoimmunotherapy followed by auto-SCT in those who are responsive), suggesting that earlier introduction of axi-cel may significantly improve outcomes [5]. While treatment sequencing remains an increasingly important question with the advent of additional therapeutic options for these patients, the use of BsAbs is currently recommended in those ineligible for, or relapsing after, CAR T therapy [31,32]. Future studies are needed to assess the real-world experience of axi-cel in earlier lines of therapy.

Overall, our findings demonstrate comparable effectiveness and safety profiles in a broad Canadian patient population consistent with those observed in trials and in international real-world studies, supporting the ongoing use of axi-cel for the treatment of R/R LBCL in Canada.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol33020085/s1, Supplemental Methods; Table S1: Efficacy outcomes by subgroups; Table S2: Safety outcomes by subgroups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., K.P., S.Z.L.L., L.B., F.N., Z.-H.H., M.C.P. and K.H.; Formal analysis, C.L., S.Z.L.L., L.B., F.N., H.-L.W., Z.-H.H. and K.H.; Methodology, H.-L.W., Z.-H.H., B.L. and Z.F.; Visualization, K.P. and H.-L.W.; Writing—original draft, C.L., J.K., M.S., K.D., K.P., S.Z.L.L., L.B., F.N., H.-L.W., J.J.K., G.L., Z.-H.H., B.L., Z.F., M.C.P. and K.H.; Writing—review and editing, C.L., J.K., M.S., K.D., S.Z.L.L., L.B., F.N., H.-L.W., J.J.K., G.L., Z.-H.H., B.L., Z.F., M.C.P. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is a collaboration between CTTC, CIBMTR, and Kite, a Gilead Company. CIBMTR® is a research collaboration between NMDP (formerly known as National Marrow Donor Program® and Be The Match®) and the Medical College of Wisconsin and is funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NCI—Cellular Immunotherapy Data Resource (CIDR)—U24CA233032; and NCI, NHLBI, and NIAID for the Resource for Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and Adoptive Cell Therapy—U24CA076518). This research was funded by Kite, A Gilead Company. CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); U24HL138660 from NHLBI and NCI; U24 CA233032 (1998–2023) from NCI; 75R60222C00008, 75R60222C00009, and 75R60222C00011 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014-24-1-2057 and N00014-25-1-2146 from the Office of Naval Research. Additional federal support is provided by OT3HL147741, P01CA111412, R01CA100019, R01CA218285, R01CA231838, R01CA262899, R01AI128775, R01AI150999, R01AI158861, R01FD008187, R01HL171117, U01AI069197, U01AI184132, U24HL157560, and UG1HL174426.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved/overseen by the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) central institutional review board (IRB-2002-0063, NCT 01166009; date of approval: 6 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this study; their families, caregivers, and friends; the study investigators, coordinators, data managers and healthcare staff. Support is also provided by Australian Bone Marrow Donor Registry; Boston Children’s Hospital; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center; Gateway for Cancer Research, Inc.; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; Medical College of Wisconsin; NMDP; Patient Center Outcomes Research Institute; PBMTF; St. Baldricks’s Foundation; Stanford University; Stichting European Myeloma Network (EMN); and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptimmune LLC; Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation; ADC Therapeutics; Adienne SA; Alexion; AlloVir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics; Autolus Limited; Beam; BeiGene; BioLineRX; Blue Spark Technologies; bluebird bio, inc.; Blueprint Medicines; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; CareDx Inc.; Caribou Biosciences, Inc.; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; DKMS; Elevance Health; Eurofins Viracor, DBA Eurofins Transplant Diagnostics; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Gift of Life Biologics; Gift of Life Marrow Registry; HistoGenetics; ImmunoFree; In8bio, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Iovance; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Japan Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Data Center; Jasper Therapeutics; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Karius; Kashi Clinical Laboratories; Kiadis Pharma; Kite, a Gilead Company; Kyowa Kirin International plc; Labcorp; Legend Biotech; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; Med Learning Group; Medac GmbH; Medexus; Merck & Co.; Mesoblast, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miller Pharmacal Group, Inc.; Miltenyi Biomedicine; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; MorphoSys; MSA-EDITLife; Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; OriGen BioMedical; Ossium Health, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacyclics, LLC, An AbbVie Company; Pierre Fabre Pharmaceuticals; PPD Development, LP; Registry Partners; Rigel Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi; Sarah Cannon; Seagen Inc.; Sobi, Inc.; Sociedade Brasileira de Terapia Celular e Transplante de Medula Óssea (SBTMO); Stemcell Technologies; Stemline Technologies; STEMSOFT; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Talaris Therapeutics; Tscan Therapeutics; Vertex Pharmaceuticals; Vor Biopharma Inc.; Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Conflicts of Interest

Christopher Lemieux: Adboard/Speaker bureau: Kite-Gilead, BMS, Roche, Abbvie, Incyte. John Kuruvilla: Research Funding: BeOne, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Merck, Consulting: Abbvie, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Roche, OmniaBio Honoraria: Abbvie, Amgen, Arvinas, Astra Zeneca, BeOne, BMS, Incyte, Janssen, Karyopharm, Kite/Gilead, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Seattle Genetics DSMB: Karyopharm. Mona Shafey: AbbVie, BMS, BeOne, AstraZeneca, Incyte, Janssen, Kite-Gilead, Roche. Kelly Davison: Advisory board/consulting: Kite-Gilead, BMS, Roche, Abbvie, Incyte, BeOne, AstraZeneca, Janssen. Kristjan Paulson: N/A. Sue Z. L. Li: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Lieven Billen: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Francis Nissen: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Hai-Lin Wang: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company; and stock or other ownership in Gilead Science. Jenny J. Kim: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Grace Lee: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Zhen-Huan Hu: Employment with Kite, a Gilead Company. Brent Logan: N/A. Zhongyu Feng: N/A. Marcelo C. Pasquini: Consultant: AstraZeneca, Honoraria: Gilead Sciences. Kevin Hay: Adboard: Kite-Gilead, BMS, Novartis, Janssen; Speaker Honorarium Miltenyi BioTec.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AE | Adverse events |

| ALK | Anaplastic lymphoma kinase |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| ANLL | Acute non-lymphomic leukemia |

| ANC | Absolute neutrophil count |

| ASTCT | American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy |

| axi-cel | Axicabtagene ciloleucel |

| BCL | B-cell lymphoma |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BsAbs | Bispecific antibodies |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CIBMTR | Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CR | Complete response |

| CRS | Cytokine release syndrome |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| CTTC | Cell Therapy Transplant Canada |

| DLBCL | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| DOCR | Duration of complete response |

| DOR | Duration of response |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EFS | Event-free survival |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FL | Follicular lymphoma |

| HCT | Hematopoietic cell transplantation |

| HCT-CI | Hematopoietic cell transplantation Comorbidity Index |

| HGBL | High-grade B-cell lymphoma |

| ICANS | Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LBCL | Large B-cell lymphoma |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MDS | Myelodysplasia |

| NE | Not evaluable |

| NMDP | National Marrow Donor Program |

| NOS | Not otherwise specified |

| NRM | Non-relapse mortality |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| PFS | Progression free survival |

| PMBCL | Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma |

| PR | Partial response |

| PTLD | Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder |

| REL/PD | Relapse or progressive disease |

| REMS | Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy |

| R/R LBCL | Relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma |

| SAS | Statistical Analysis System |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TTCR | Time to complete response |

| TTOR | Time to overall response |

| WBC | White blood cell |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Patient disposition diagram. Abbreviations: Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; FL, follicular lymphoma.

Figure A1.

Patient disposition diagram. Abbreviations: Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; FL, follicular lymphoma.

Figure A2.

Cumulative incidence function plot for (a) ORR and (b) CR. REL/PD or death were treated as competing risks. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence of (a) ORR and (b) CR at 6 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; ORR, overall response rate.

Figure A2.

Cumulative incidence function plot for (a) ORR and (b) CR. REL/PD or death were treated as competing risks. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence of (a) ORR and (b) CR at 6 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; ORR, overall response rate.

Figure A3.

Cumulative incidence function plot for REL/PD. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence of REL/PD at 6 and 12 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; REL/PD, relapse or progressive disease.

Figure A3.

Cumulative incidence function plot for REL/PD. The shaded areas represent the 95% CI. The dotted lines represent the estimated cumulative incidence of REL/PD at 6 and 12 months. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; REL/PD, relapse or progressive disease.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Reasons for ZUMA-1 ineligibility.

Table A1.

Reasons for ZUMA-1 ineligibility.

| Reason | N (%), N = 39 |

|---|---|

| Other B-cell lymphoma | 1 (3) |

| ECOG > 1 | 7 (18) |

| Organ impairment | 28 (72) |

| Renal (moderate/severe), at the time of infusion or prior renal transplant | 2 (5) |

| Hepatic (moderate/severe), any history or at the time of infusion | 1 (3) |

| Pulmonary (moderate), at the time of infusion | 12 (31) |

| Pulmonary (severe), at the time of infusion | 4 (10) |

| Cardiac, any history | 14 (36) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, any history | 3 (8) |

| Heart valve disease | 1 (3) |

| Infection | 4 (10) |

| Autoimmune disease | 4 (10) |

| CNS involvement | 3 (8) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Table A2.

Primary cause of death.

Table A2.

Primary cause of death.

| Cause a | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Primary disease | 42 (37) |

| Organ failure b | 3 (3) |

| Malignancy c | 2 (2) |

a % of all patients. Number of patients who died during follow-up (n = 47). b Cases of organ failure were reported as two pulmonary failures and one cardiac failure, occurring at 4.2 months, 7.9 months, and 0.3 months, respectively. c One patient reported onset of MDS on Day 142, died on Day 435 without REL/PD of primary disease. One patient reported onset of AML on Day 160, died on Day 264 without REL/PD of primary disease. There were no malignancies of T cell origin.

References

- Crump, M.; Neelapu, S.S.; Farooq, U.; Van Den Neste, E.; Kuruvilla, J.; Westin, J.; Link, B.K.; Hay, A.; Cerhan, J.R.; Zhu, L.; et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood 2017, 130, 1800–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite Pharma Inc. YESCARTA® Product Monograph. 2019. Available online: https://www.gilead.com/en-ca/-/media/gilead-canada/pdfs/science/yescarta-english-pm.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Neelapu, S.S.; Locke, F.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Lekakis, L.J.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Braunschweig, I.; Oluwole, O.O.; Siddiqi, T.; Lin, Y.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Jacobson, C.A.; Ghobadi, A.; Miklos, D.B.; Lekakis, L.J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Lin, Y.; Braunschweig, I.; Hill, B.T.; Timmerman, J.M.; et al. Five-year follow-up of ZUMA-1 supports the curative potential of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2023, 141, 2307–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, F.L.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Perales, M.A.; Kersten, M.J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Ghobadi, A.; Rapoport, A.P.; McGuirk, J.; Pagel, J.M.; et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second-Line Therapy for Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.A.; Locke, F.L.; Ma, L.; Asubonteng, J.; Hu, Z.H.; Siddiqi, T.; Ahmed, S.; Ghobadi, A.; Miklos, D.B.; Lin, Y.; et al. Real-World Evidence of Axicabtagene Ciloleucel for the Treatment of Large B Cell Lymphoma in the United States. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2022, 28, 581.e1–581.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nastoupil, L.J.; Jain, M.D.; Feng, L.; Spiegel, J.Y.; Ghobadi, A.; Lin, Y.; Dahiya, S.; Lunning, M.; Lekakis, L.; Reagan, P.; et al. Standard-of-Care Axicabtagene Ciloleucel for Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma: Results From the US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3119–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, R.; Le Gouill, S.; Bachy, E.; Cartron, G.; Beauvais, D.; Le Bras, F.; Gros, F.X.; Choquet, S.; Bories, P.; Feugier, P.; et al. Outcomes of patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma after failure of anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy: A DESCAR-T analysis. Blood 2022, 140, 2584–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, S.; Roddie, C.; O’Reilly, M.; Menne, T.; Norman, J.; Gibb, A.; Lugthart, S.; Chaganti, S.; Gonzalez Arias, C.; Jones, C.; et al. Improved outcomes of large B-cell lymphoma patients treated with CD19 CAR T in the UK over time. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 204, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, M.; Iacoboni, G.; Reguera, J.L.; Corral, L.L.; Morales, R.H.; Ortiz-Maldonado, V.; Guerreiro, M.; Caballero, A.C.; Dominguez, M.L.G.; Pina, J.M.S.; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel compared to tisagenlecleucel for the treatment of aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2023, 108, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethge, W.A.; Martus, P.; Schmitt, M.; Holtick, U.; Subklewe, M.; von Tresckow, B.; Ayuk, F.; Wagner-Drouet, E.M.; Wulf, G.G.; Marks, R.; et al. GLA/DRST real-world outcome analysis of CAR T-cell therapies for large B-cell lymphoma in Germany. Blood 2022, 140, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverdure, E.; Mollica, L.; Ahmad, I.; Cohen, S.; Lachance, S.; Veilleux, O.; Bernard, M.; Marchand, E.L.; Delisle, J.S.; Bernard, L.; et al. Enhancing CAR-T Efficacy in Large B-Cell Lymphoma with Radiation Bridging Therapy: A Real-World Single-Center Experience. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Elsawy, M.; Nielsen, R.; Harrigan, A.M.; DiCostanzo, T.T.; Minard, L.V. Real-World Characterization of Toxicities and Medication Management in Recipients of CAR T-Cell Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Nova Scotia, Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 32, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, A.; Boies, M.-H.B.; Dery, N.; Garcia, L.M.; Simard, M.; Poirier, M.; Delage, R.; Canguilhem, B.L.; Doyle, C.; Larouche, J.-F.; et al. CAR T-Cells for the Treatment of Refractory or Relapsed Large B-Cell Lymphoma: A Single-Center Retrospective Canadian Study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.X.S.; Maltez, M.T.; Mallick, R.; Hamelin, L.; McDiarmid, S.; Cieniak, C.; Granger, M.; Bredeson, C.; Kennah, M.; Atkins, H.L.; et al. Distance to CAR-T Treatment Center Does Not Impede Delivery. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 114, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyakoon, C.; Bhella, S.; Hueniken, K.; Aitken, R.; Waldron, C.; Prica, A.; Kukreti, V.; Kridel, R.; Vijenthira, A.; Chen, C.; et al. Inferior survival in double refractory large B-cell lymphoma eligible for third-line CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Neoplasia 2025, 2, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Santomasso, B.D.; Locke, F.L.; Ghobadi, A.; Turtle, C.J.; Brudno, J.N.; Maus, M.V.; Park, J.H.; Mead, E.; Pavletic, S.; et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorror, M.L.; Logan, B.R.; Zhu, X.; Rizzo, J.D.; Cooke, K.R.; McCarthy, P.L.; Ho, V.T.; Horowitz, M.M.; Pasquini, M.C. Prospective Validation of the Predictive Power of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Study. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015, 21, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejeski, K.; Perez, A.; Sesques, P.; Hoster, E.; Berger, C.; Jentzsch, L.; Mougiakakos, D.; Frolich, L.; Ackermann, J.; Bucklein, V.; et al. CAR-HEMATOTOX: A model for CAR T-cell-related hematologic toxicity in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2021, 138, 2499–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachy, E.; Le Gouill, S.; Di Blasi, R.; Sesques, P.; Manson, G.; Cartron, G.; Beauvais, D.; Roulin, L.; Gros, F.X.; Rubio, M.T.; et al. A real-world comparison of tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T cells in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houot, R.; Bachy, E.; Cartron, G.; Gros, F.X.; Morschhauser, F.; Oberic, L.; Gastinne, T.; Feugier, P.; Dulery, R.; Thieblemont, C.; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy in large B cell lymphoma ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation: A phase 2 trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2593–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnl, A.; Kirkwood, A.A.; Roddie, C.; Menne, T.; Tholouli, E.; Bloor, A.; Besley, C.; Chaganti, S.; Osborne, W.; Norman, J.; et al. CAR T in patients with large B-cell lymphoma not fit for autologous transplant. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 202, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.C.; Mustafa, J.; Lombardo, A.; Khatun, F.; Joseph, F.; Gillick, K.; Naik, A.; Elkind, R.; Abreu, M.; Fehn, K.; et al. Safety of axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma in an elderly intercity population. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1761–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easwar, N.; Fein, J.; Pasciolla, M.S.; Abramova, R.; Shore, T.B.; Yamshon, S. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel in Patients Aged 75 and Older: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Blood 2023, 142, 6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topp, M.S.; van Meerten, T.; Houot, R.; Minnema, M.C.; Bouabdallah, K.; Lugtenburg, P.J.; Thieblemont, C.; Wermke, M.; Song, K.W.; Avivi, I.; et al. Earlier corticosteroid use for adverse event management in patients receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 195, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddie, C.; Neill, L.; Osborne, W.; Iyengar, S.; Tholouli, E.; Irvine, D.; Chaganti, S.; Besley, C.; Bloor, A.; Jones, C.; et al. Effective bridging therapy can improve CD19 CAR-T outcomes while maintaining safety in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2872–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnix, C.C.; Gunther, J.R.; Dabaja, B.S.; Strati, P.; Fang, P.; Hawkins, M.C.; Adkins, S.; Westin, J.; Ahmed, S.; Fayad, L.; et al. Bridging therapy prior to axicabtagene ciloleucel for relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2871–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Wesson, W.; Lutfi, F.; Porter, D.L.; Bachanova, V.; Nastoupil, L.J.; Perales, M.A.; Maziarz, R.T.; Brower, J.; Shah, G.L.; et al. Optimizing the post-CAR T monitoring period in recipients of axicabtagene ciloleucel, tisagenlecleucel, and lisocabtagene maraleucel. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 5346–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Eliminates Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for Autologous Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T cell Immunotherapies. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/fda-eliminates-risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems-autologous-chimeric-antigen-receptor (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Kersten, M.J.; Oluwole, O.O.; Speth, K.; Song, Q.; Martin, L.J.; Shu, D.; Kim, J.J.; Adhikary, S.; Perales, M.A. Incidence of Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurological Events in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma at and Beyond 2 Weeks Following Axicabtagene Ciloleucel Infusion. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2025, 31, S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, I.; MacDonald, D.; Shafey, M.; Christofides, A.; Sehn, L.H. Optimal Use of Bispecific Antibodies for the Treatment of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, I.Y.; Kuruvilla, J. Management of relapsed/refractory DLBCL in the era of novel agents and new approaches. Leuk. Lymphoma 2026, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.