Simple Summary

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive and highly metastatic cancer that shows therapy resistance and poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Due to the lack of expression of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, hormonal therapy is unable to target TNBC and mostly relies on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy as treatment options in the clinic. Downregulation of dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1 (DUSP1/MKP-1) in TNBC may promote TNBC cell proliferation and metastasis by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). In this brief review, we analyzed the expression profile of DUSP1 and discussed its correlation, significance, and therapeutic potential in TNBC with the current literature.

Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive breast cancer subtype characterized by high rates of recurrence, limited targeted treatment options, and frequent resistance to standard therapies. Dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), a stress-responsive regulator of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, has emerged as a context-dependent modulator of tumor progression and therapeutic response in TNBC. While reduced DUSP1 expression has been associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor prognosis, accumulating evidence indicates that therapy-induced upregulation of DUSP1 can promote resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy by attenuating pro-apoptotic MAPK signaling and fostering immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). Emerging evidence highlights that DUSP1’s role is context-dependent on human cancers, including breast cancer (BC). This review synthesizes current evidence on DUSP1 biology in TNBC, with emphasis on its mechanistic involvement in chemotherapy resistance, radiation-induced immune modulation, and emerging implications for immunotherapy response.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the second most common heterogeneous cancer among women globally, and in 2025, about 316,950 invasive BC cases will be estimated in the United States alone. One in eight women is diagnosed with BC in the United States, and overall, 5-year survival is about 91.7%. The worst 5-year survival rate, 78.4%, is observed in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (American Cancer Society). TNBC accounts for approximately 15–20% of breast cancer cases and is associated with early recurrence, high metastatic potential, and poor overall survival (OS). BC is heterogeneous cancer and the heterogeneity of BC subtypes is mainly categorized as luminal A: hormone receptor HR+/HER2- (hormone receptor +/human epidermal growth factor 2-), luminal B: (HR+/HER2+ or HR+/HER2- with high Ki-67), HER2 enriched: (HR-/HER2+), and triple-negative: estrogen receptor (ER)-/progesterone receptor (PR)-/HER2-) [1]. The heterogeneity in BC also depends on the level of expression of specific genes, such as ESR1, GATA3, HER2, ERBB2, and is also associated with genetic mutations in TP53 and BRCA1/2, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) around the TNBC tumor. Specifically, TNBC lacks the expression of ER, PR, and HER2 receptors [2,3], and the lack of these receptors and the mutation of genes are crucial for personalized treatment and predicting prognosis in TNBC patients [4,5].

Several strategies are applied to treat these BC-subtypes in the clinic that include chemotherapy, immunotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy (RT) to improve loco-regional control of BC against metastasis and recurrence [6]. Importantly, each therapy interacts and interplays with other therapies; for example, chemotherapy sensitizes the BC tumor to death and increases the efficacy of RT, whereas RT improves systemic response to immunotherapy [7,8,9]. In most secondary metastatic BC cases, RT is used with adjuvant therapy, neoadjuvant therapy, and palliative therapy [10]. Since TNBC lacks HRs and HER2, targeting TNBC presents many more challenges.

Dual-specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1), also known as MAP kinase phosphatase 1, is a key negative regulator of MAPK signaling that dephosphorylates both threonine and tyrosine residues on activated MAPKs. Multiple studies have reported reduced DUSP1 expression in TNBC compared with other breast cancer subtypes, with low DUSP1 levels associated with aggressive tumor behavior, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and poor clinical outcomes. In contrast, therapy-induced upregulation of DUSP1 has been implicated in resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiotherapy through regulation of MAPKs activities (JNK, ERK, and p38), modulation of inflammatory signaling pathways, and promotion of tumor cell survival. Importantly, these findings indicate that the role of DUSP1 in TNBC may be highly context-dependent and cannot be defined as uniformly tumor suppressive or tumor-promoting. Therefore, in this report, we specifically analyzed the regulatory role of dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1 (DUSP1/MKP-1), a MAPK phosphatase, in the therapy resistance of TNBC.

2. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

The origin and risk of TNBC start from the mutations or changes in 19p13.1 locus on chromosome 19, the MDM4 locus, and a unique pattern of germline mutations in the BRCA1 gene [11,12]. Due to the high gene mutation rate in TNBC, especially in genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2, it lacks a DNA repair mechanism, leading to increasing genomic instability and frequently losing ER, PR, and HER2 cell surface receptor expression [13,14]. Due to the lack of ER, PR, and HER2 expression, and increased expression of basal cytokeratin, TNBC adopts a basal-like (BL) cell profile, one of the BC subtypes. Although the BC subtype consists of 90% of other subtypes, luminal A (HR+/HER2-) 68%, luminal B (HR+/HER2+) 10%, HER2-overexpressing (HR-/HER2+) 4%, and unknown subtype 7%, whereas only 10 to 11% basal-like (HR-/HER2-) BC subtype population belongs to TNBC [15]. TNBC is further classified based on the percentage of basal-like cell profile, mesenchymal (M) like cell profile, and expression of luminal androgen receptor (LAR) cell profile [16,17]. TNBC consists of basal-like 1 (BL1) 35%, basal-like 2 (BL2) 22%, mesenchymal (M) 25%, luminal androgen receptor (LAR) 16% cell population [18].

TNBC is an aggressive breast cancer that mostly occurs in young women (~40 ages) as well as in older women, and a high incidence is reported in non-Hispanic black women [19]. Due to a lack of ER, PR, and HER2 receptors, treating TNBC with standard targeted therapies is difficult and mostly relies on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy [20]. The five-year overall relative survival rate of patients with TNBC is worse compared with other BC subtypes. The five-year relative survival rate of the localized TNBC was 92.4%, regional TNBC was 76.5%, whereas distant TNBC was only 14.9% [21]. TNBC is an aggressive disease with a high rate of metastasis and recurrence, and the development of TNBC is associated with race, premenopausal status, and BCRA1/2 inherited mutations; however, if diagnosed at stage I, II, or III, 80% to 90% of TNBC patients can potentially be cured. Treatment of TNBC depends on the stage of the cancer, ranging from Stage 0 (abnormal and non-invasive cells) to Stage IV (metastatic cancer cells) [22]. Generally, in the treatment plan at Stage I, chemotherapy followed by surgery (either a lumpectomy or mastectomy) and radiotherapy, TNBC at Stage II or III chemotherapy and immunotherapy, then surgery and possible radiotherapy may apply [22]. However, TNBC with Stage IV is not curable, but rather treatable. In such cases, molecular profiling, including immune cell-related PD-L1 expression, genomic testing (such as mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2), and therapy resistance tumor factors, as well as patient-specific clinical trials, are considered for further treatment options. Patients with metastatic TNBC (Stage IV) about 50% patients show an average survival of 1 ½ to 2 years [23]. Therefore, understanding the role of molecular factors that are associated with therapy resistance and TNBC recurrence is essential.

Recently, we reviewed the TNBC tumor microenvironment (TEM) and analyzed how RT modulated immune changes in TNBC-TEM [24]. We also analyzed the regulation and therapeutic significance of DUSP1 in various cancers [25]. In this brief report, we mainly focus on how DUSP1 modulates chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy sensitivity or resistance in TNBC.

3. DUSP1 Regulation in Breast Cancer (BC) Subtypes

DUSP1 is a dual-specificity phosphatase that dephosphorylates both threonine and tyrosine residues of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and controls several key cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, stress responses, and drug resistance in cancer cells [25]. The activated MAPKs, through phosphorylation, induce resistance against chemotherapeutic drugs in several human cancers [25,26], and dysregulation of DUSP1 expression in BC tumors, particularly TNBC, disproportionately activates MAPKs and modulates the response of oncologic therapies.

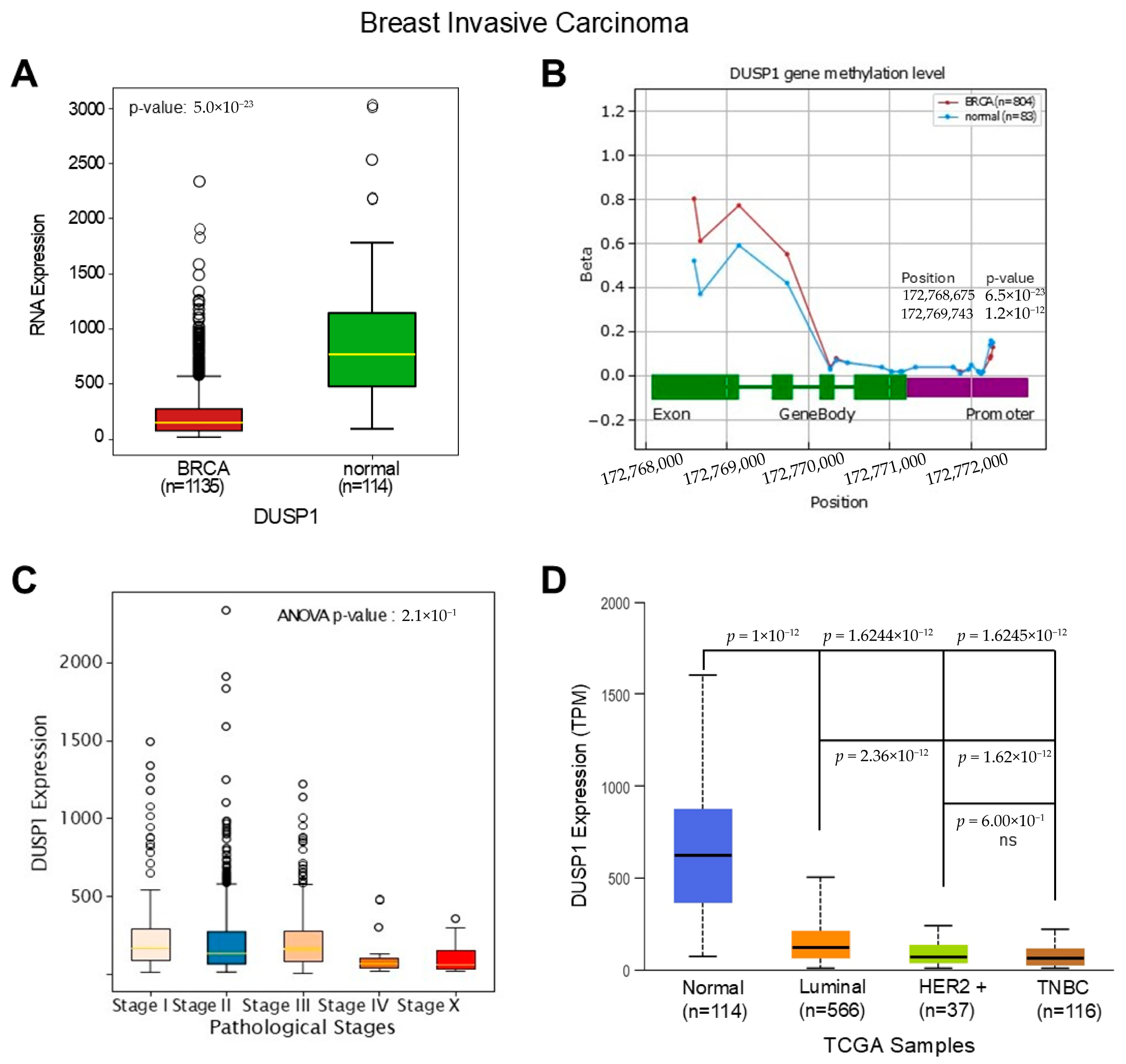

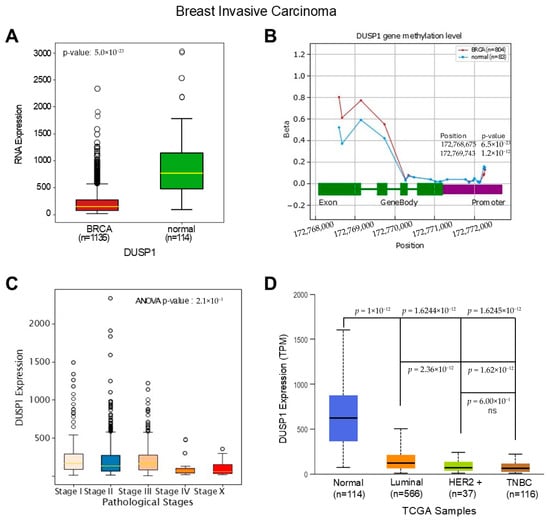

To understand the deregulatory role of DUSP1 in BC subtypes first, we analyzed the expression of DUSP1 transcripts in invasive BC tumors and compared them to normal breast tissues. TCGA data analysis suggests that DUSP1 transcript expression is significantly downregulated in invasive BC tumors (n = 1135) compared to normal breast tissue (n = 114) (Figure 1A) (https://oncodb.org/cgi-bin/expression_profile.cgi (accessed on 20 December 2025)) [27]. The downregulation of DUSP1 expression may occur due to the DUSP1 gene methylation; however, as shown in Figure 1B, no significant change in methylation was found in the DUSP1 promoter region in BC tumors compared with the normal breast cells’ DUSP1 gene promoter. An increased methylation pattern was found in the exon and intron region of the DUSP1 gene (primarily DNA methylation (5mC) and m6A) in BC tumor cells (Figure 1B). The promoter methylation often silences gene expression, whereas exon and intron methylation profoundly impacts gene expression by dysregulation of transcription, mRNA splicing, and mRNA stability [28,29]. The role of the exon and intron methylation on DUSP1 transcript expression is not yet clear.

Figure 1.

DUSP1 expression in BC and TNBC. (A) The expression of DUSP1 transcripts between BC tumor (n = 1135) and normal breast (n = 114) was analyzed from the TCGA data set, and the data were extracted from the OncoDB portal (https://oncodb.org/cgi-bin/expression_profile.cgi (accessed on 20 December 2025)) and presented. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, and the p-value was presented. (B) DUSP1 gene methylation profile from BC tumor (n = 804) and normal breast (n = 83) was analyzed from the TCGA data set and OncoDB portal and presented. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, and significant p-values with positions were presented. (C) DUSP1 expression levels in different Stages of BC were presented using the TCGA data set and OncoDB portal analysis. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA, and the p-value was presented in the graph. (D) DUSP1 expression levels in different BC subtypes were presented using the TCGA data set and UALCAN portal (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025)). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, and the p-values are presented between the two groups. p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Because DUSP1 expression is downregulated in invasive BC tumors, and to understand the significance of DUSP1 downregulation, we further analyzed the expression levels of DUSP1 in various Stages of BC tumors (Figure 1C). The expression of DUSP1 transcripts decreased as BC pathological Stages increased, and at Stage IV presumably metastatic BC, the lowest expression of DUSP1 was observed suggesting the reduction in DUSP1 expression promote advanced BC progression. Further, we analyzed the expression of DUSP1 in BC subtypes. The DUSP1 expression profile clearly indicates that, compared to normal breast, the DUSP1 expression in Luminal, HER2+, and TNBC BC subtypes significantly decreased, and the lowest expression of DUSP1 was observed in TNBC tumors (Figure 1D) (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025)) [30]. Moreover, DUSP1 expression was significantly downregulated in HER2+ and TNBC compared with luminal BC subtypes, whereas there was no significant change in DUSP1 expression observed between HER2+ and TNBC BC tumors (Figure 1D).

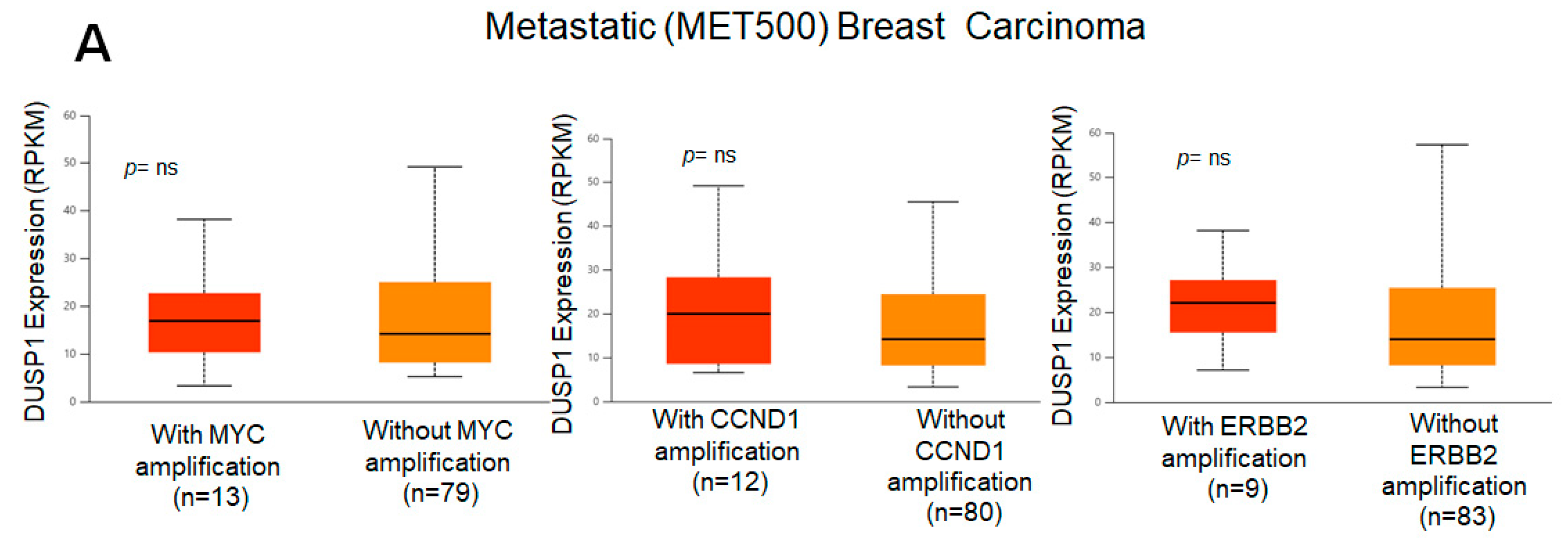

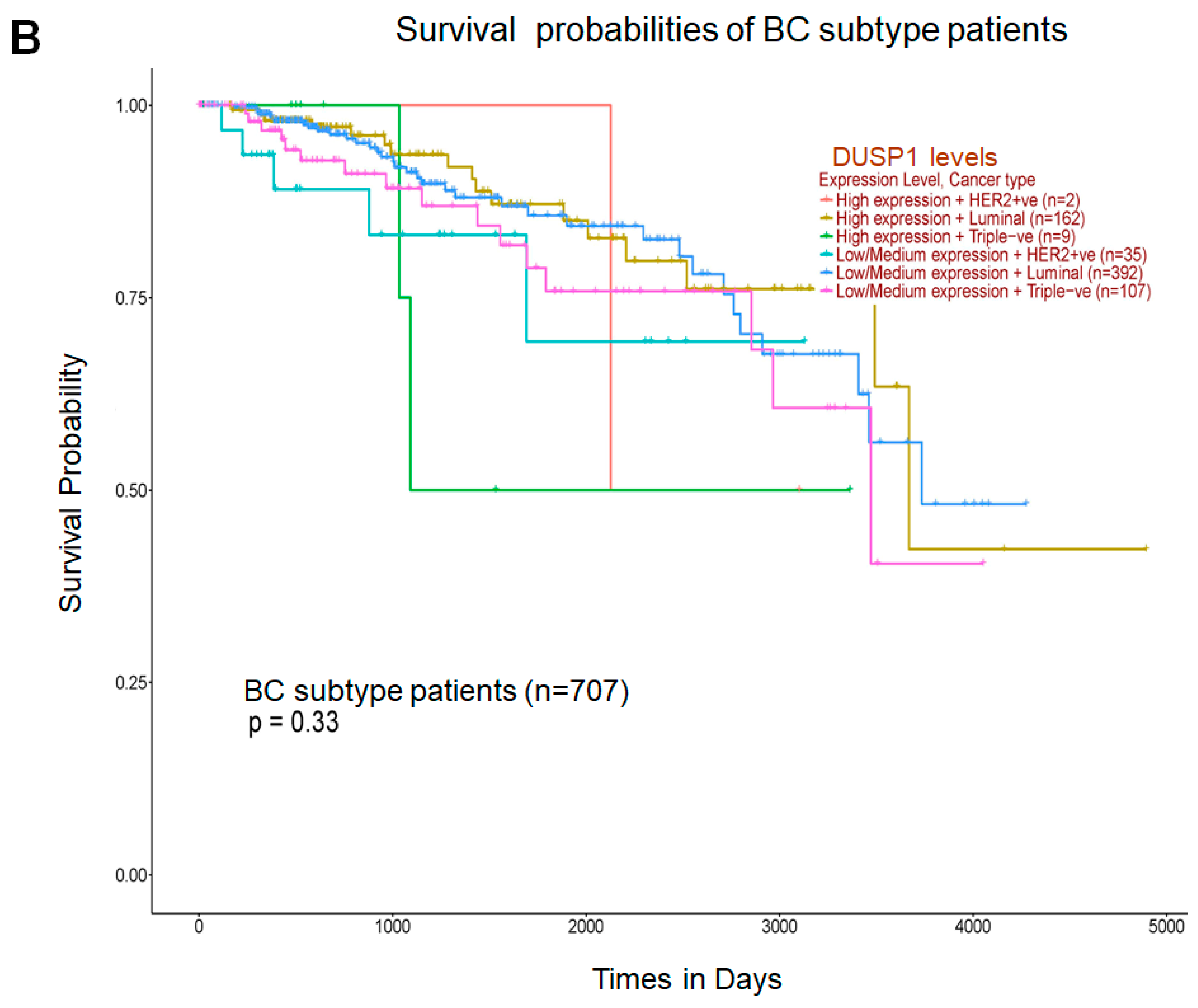

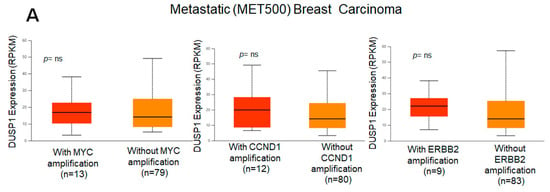

Because DUSP1 expression was downregulated in the highly aggressive and metastatic TNBC tumor, we analyzed the correlation of DUSP1 expression with three important genes that participate in BC aggressiveness and metastasis, such as MYC [31], CCND1 [32], and ERBB2 (HRE2) [33]. TCGA correlation analysis suggests that the expression of DUSP1 shows a weak positive linear relationship (R = 0.2) with MYC gene expression and a weak and no relationship with CCND1 or ERBB2 expression in BC tumors [34]. Interestingly, in metastatic BC tumors, the expressions of MYC, CCND1, and ERBB2, and the expression of DUSP1 did not significantly change, suggesting that DUSP1 expression may contribute to BC metastasis like MYC, CCND1, and HER2 expression (Figure 2A). The role of DUSP1 expression and cell metastasis needs further investigation. Finally, we analyzed the survival probabilities of BC subtype patients associated with DUSP1 expression (Figure 2B). Although the patient size is small, as indicated in Figure 2B, TNBC patients with low DUSP1 expression (n = 107) show a better prognosis but lower survival compared to high DUSP1-expressing TNBC patients (n = 9). Overall, these data suggest that DUSP1 is a key regulator of survival in BC patients, particularly in those with advanced and metastatic TNBC.

Figure 2.

DUSP1 expression and BC subtype patient survival. (A) Co-relation of DUSP1 expression with and without MYC, CCND1, and ERBB2 in metastatic (MET500) BC patients was presented. (B) Survival probabilities of BC-subtype patients with low and high DUSP1 expression were presented from the UALCAN portal. (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html (accessed on 12 December 2025)). Statistical significance between the groups was determined by the t-test, and the p-values are presented. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In the following sections, we will review the interference, significance, and therapeutic modulatory role of DUSP1 in highly metastatic TNBC.

4. DUSP1 Regulation and Its Role in TNBC Chemotherapy

Although the low expression of DUSP1 is reported in TNBC, several studies suggest that DUSP1 plays a crucial role in modulating TNBC progression. He et al. utilized the microarray technique to characterize the molecular gene profiling between TNBC and non-TNBC subclasses [35]. Functional annotation for these differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and validation of gene expression clearly suggest that the expression of DUSP1 is downregulated in several TNBC cell lines compared to HR-positive BC cells [35]. The protein–protein interaction network analysis suggests that DUSP1 may be considered as a potential therapeutic target for TNBC treatment [35]. Several factors contribute to the regulation of DUSP1 in TNBC. For example, the cause of low expression of DUSP1 in TNBC is due to the DUSP1 gene methylation in ER/PR-negative BC. A high frequency of DUSP1 methylation was found in TNBC patients, not only in tumor DNA samples but also in the peripheral blood leukocyte (PBL) DNA [36]. The increased DUSP1 methylation in TNBC is associated with several diet factors (fruit and soybean intake), irregular menstruation, environmental factors, and the ER/PR status in the BC tumor [36]. Since circRNAs bind with microRNA and prevent them from inhibiting their target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and regulate gene expression [37]. A recent study suggests that the aggressiveness of TNBC can be controlled by circular DUSP1 (circDUSP1) RNA in TNBC. Jian et al. identified and analyzed circDUSP1 RNA, which was significantly downregulated in TNBC cells, and overexpression of circDUSP1 RNA inhibits TNBC cell proliferation, migration, invasion in vitro, and TNBC tumor growth in vivo [38]. Mechanistically, circDUSP1 RNA binds with microRNA-429 to relieve its repression of the tumor suppressor Deleted in Liver Cancer (DLC1) gene, thus circDUSP1 RNA acts as a molecular sponge for microRNA-429 to upregulate DLC1, which then suppresses TNBC growth.

The high expression of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) in the early stage of TNBC correlates with chemotherapy resistance and increased recurrence. An earlier study revealed that the GR antagonist mifepristone alone does not show a significant effect on TNBC cell viability or clonogenicity; however, with mifepristone and chemotherapeutic drugs, dexamethasone/paclitaxel treatment increased cytotoxicity and apoptosis. Mechanistically, mifepristone antagonized GR-induced SGK1 and DUSP1 gene expression while significantly increasing tumor shrinkage in paclitaxel-induced MDA-MB-231 TNBC xenograft in vivo, suggesting that GR antagonist mifepristone may be useful for suppression of chemotherapy-resistant GR + TNBC [39]. On the other hand, high levels of β2-adrenergic receptor expression were observed in TNBC, which directly modulate the activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2. Exposure of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists increased dephosphorylation of basal pERK1/2 in TNBC (MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468) cells. Interestingly, β2-adrenergic receptor activation by agonists increased DUSP1 expression and the active form of PP1, and the inactivation of DUSP1 by (E)-2-benzylidene-3-(cyclohexylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one (BCI) and PP1/PP2 by calyculin A or downregulation of DUSP1 and PP1 decreased the β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 suggesting DUSP1 and PP1 activity required for dephosphorylation of ERK1/2. Indeed, the study further suggests that the use of β2-adrenergic blockers may be useful for TNBC patient treatment via DUSP1 regulation [40]. Basal-like breast cancer (BLBC) and TNBC show significant biological overlaps (around 60–90%), and BLBCs show resistance to endocrinotherapy or hormone therapy. Recent studies suggest that paclitaxel (PTX) resistance in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells shows downregulation of DUSP1 and DUSP5 and is negatively associated with higher histological tumor grade in BC patients. Interestingly, the study revealed that low expression of DUSP1 was found in HER2+ basal-like cells, whereas DUSP5 low expression was mainly observed in basal-like cells compared with other subtypes, suggesting that not low DUSP1 expression but loss of DUSP5 expression was associated with PTX resistance and poor survival of BLBC patients, thus restoring DUSP5 level may improve therapeutic potency of BLBC [41]. Since the expression of DUSP1 is downregulated in TNBC. Several compounds may activate DUSP1 expression and activity; for example, an organic c-glycosyl compound, aurovertin B (AVB), exposure to TNBC cells upregulates DUSP1 expression and, by interacting with DUSP1, AVB-DUSP1 activates activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) and subsequently suppresses TNBC metastasis [42].

As we indicated earlier, the role of DUSP1 is context-dependent in cancers [25]. Several studies analyzed the effect of DUSP1 on MAPK signaling under the influence of chemotherapeutic drugs. In human mammary epithelial cells A1N4-myc, BC BT-474 triple-positive, and TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells, a transient and stable overexpression of DUSP1 and treatment of mechlorethamine (DNA alkylating agents), doxorubicin (an anthracycline drug), and paclitaxel (microtubule inhibitor) show high suppression of JNK1 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 and BT-474 cells, decreased DNA fragmentation, apoptosis, and increased chemoresistance by increasing cell proliferation [43]. In contrast, DUSP1 knockdown (siRNA) or inhibition (SD-282 inhibitor) followed by single or combined exposure to doxorubicin and mechlorethamine increased drug sensitivity through JNK activation, suggesting that targeting DUSP1 may overcome the drug resistance and promote chemo-sensitization [43]. Similarly, the reduction in DUSP1 by using CRISPR/Cas9 and siRNA or the inhibition of DUSP1 by BCI exposure suppressed cell proliferation, migration, and tumor growth in the TNBC xenograft model [44]. Downregulation of DUSP1 increased the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK, but not ERK1/2, and increased anticancer response induced by cisplatin. Importantly, cisplatin exposure increased p38 phosphorylation by reducing DUSP1 expression in TNBC cells [44]. Collectively, these in vitro studies suggest that targeting or downregulation of DUSP1 increases the efficacy of anticancer drugs.

Furthermore, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays a crucial role in chemotherapy resistance in TNBC, enabling TNBC cells to acquire a stem-like appearance, thereby promoting invasiveness and chemoresistance [45]. The DUSP family members play a crucial role in EMT and cancer stem cell (CSC) regulation in BC and TNBC [46]. In BC cells, immunocytochemical data suggest that DUSP1, DUSP4, and DUSP6 differentially co-exist with enhancer and permissive active histone post-translational modifications and modulation of EMT and CSC-like transitions. Importantly, MDA-MB-231 cells, DUSP1, and DUSP4 were mostly localized in the nucleus, while DUSP6 showed strong cytoplasmic localization. In TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells, DUSP1 showed high levels of co-localization with the active promoter marks H3K9me1 (PCC = 0.65) and H3K4me3 (PCC = 0.72), indicating DUSP1 plays distinct roles in EMT gene regulation in TNBC cells. The study further revealed that knockdown of DUSP1, DUSP4, and DUSP6 regulates the formation of CD44hi/CD24lo/EpCAM+ breast CSCs. Interestingly, DUSP1 knockdown reduces CSC formation, while DUSP4 and DUSP6 knockdown enhance CSC formation in BC [46]. In addition, in TNBC cells, the lack of tumor suppressive microRNA-200 expression and loss of 3’UTR may increase DUSP1 expression and promote EMT, and miR-200b-3p overexpression represses EMT [47]. Yuan et al. have identified differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes in TNBC patients and found that seven genes, such as DUSP1, STEAP3, CISD1, HMOX1, CA9, TAZ, and HBA1, were associated with the overall survival (OS) of TNBC patients [48]. High expression of STEAP3 was associated with overall survival rates of TNBC patients, although the role of DUSP1 is not clear.

Indeed, DUSP1 is a negative regulator of the MAPK pathway to maintain cell proliferation and survival; however, in TNBC, downregulation of DUSP leads to aberrant expression of several pathways, and the exact mechanisms by which DUSP1 modulates EMT, metastasis, and chemotherapy escape remain unknown so far.

5. DUSP1’s Role in TNBC Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy not only kills or shrinks the cancerous tumor but also plays a crucial role in cancer treatment to enhance chemotherapy or immunotherapy efficacy [49]. Several cancer tumorigenic factors can cause radioresistance; for example, activation of transcription factors and signaling pathways (Wnt, Notch, STAT, PI3K/AKT, NF-κB, and Hedgehog), induction of DNA repair mechanisms, EMT, tumor-derived production of cancer stem cells (CSCs), and dynamics of tumor microenvironment (TME), which prompts stemness in the tumor [50]. Early studies indicate that DUSP1 and MAPKs play a role in redioresistance [51]. For example, overexpression of DUSP1 inactivates stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) and MAPK (p38) and protects human monocyte-like histiocytic lymphoma cells against UV-induced apoptosis [52], whereas mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in DUSP1 show increased UV sensitivity due to activation of MAPKs (p38α and JNK) [53], suggesting DUSP1 modulates radiation response in tumor cells. In BC MCF7 cells and TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells, radiation exposure (2 h) induced DUSP1 expression and translocated into mitochondria, by interacting with JNK, reduced phosphorylated active forms of JNK kinase [54]. To analyze the radiosensitivity and radioresistance between BC cell-subtypes, the authors have utilized MCF7 wt (HER2-low), SKBR3 (HER2-positive), MCF7/C6 (HER2-overexpressing), MDA-MB-231 (HER2-negative), and HER2-positive BCSCs (HER2+/CD44+/CD24−/low) cells. The silencing of DUSP1 expression and radiation exposure clearly indicated that HER2-positive breast cancer cells were more sensitive to radiation compared with HER2-low/negative cell lines. Clonogenic survival assay suggests that knocking down DUSP1 in HER2-overexpressing SKBR3 (ER-/PR-) cells and TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells inhibit 65% and 20% cell colony formation, respectively. However, MDA-MB-231 cells show high radiosensitivity after DUSP1 knockdown compared to SKBR3 cells, suggesting that DUSP1 is important for HER2-positive breast cancer cells for survival compared to HER2-negative or TNBC MDA-MB-231cells [54]. The author further suggests that combined inhibition of DUSP1 and HER2 may enhance radiosensitivity in HER2-positive BC cells [55].

Radioresistance in BC is common [24,56] because of BC tumor heterogeneity/subtypes, genetic mutation, presence of CSCs [57], impaired DNA repair mechanisms, dysregulated oncogenic signaling, and cell cycle traits [58]. Recently, in our laboratory, we analyzed the impact of radiation therapy (RT) on targeted gene expression (NanoString nCounter approach) and comparatively analyzed the differential gene expression (DGE) profile between biopsy (pre-RT) vs. surgical (post-RT) BC tumors. Our data suggest RT induced expression of DUSP1 and macrophage M2-associated CD163 in BC tumors. Importantly, DUSP1 expression is not only found in tumor cells but also in immune cells, such as macrophages, and is also released in the serum upon cell damage or during apoptosis [59,60,61], and serum circulating levels of DUSP1 can be measured with ELISA [61] for monitoring any correlation with patient prognosis. In addition, our data suggest that RT also enhanced residual cancer burden (RCB) in BC tumors, thus creating an immunosuppressive TME. Because DUSP1 plays a complex role in BC tumor growth, metastasis, therapy resistance, and context-dependent function, currently, in our laboratory, we are analyzing the impact of RT on tumor and serum-associated DUSP1expression in patients with BC and TNBC tumors with various pathology grades, TNM staging, and HR status, to understand the role of DUSP1 in radiation efficiency and radioresistance.

6. DUSP1’s Role in Immunotherapy

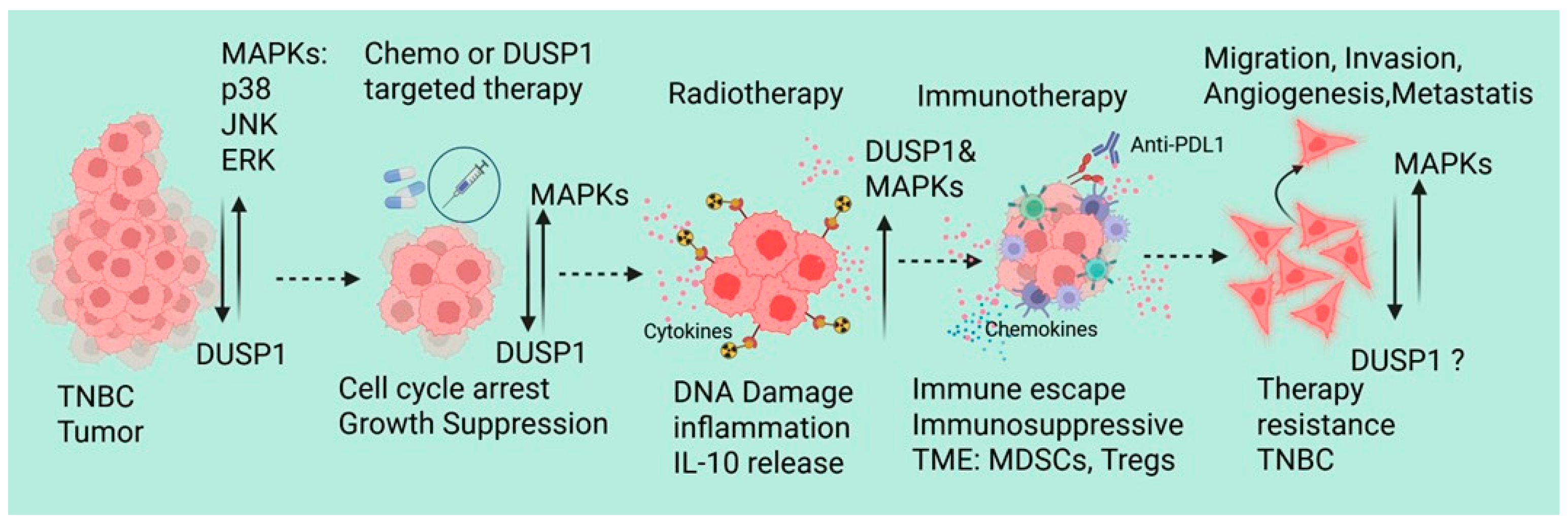

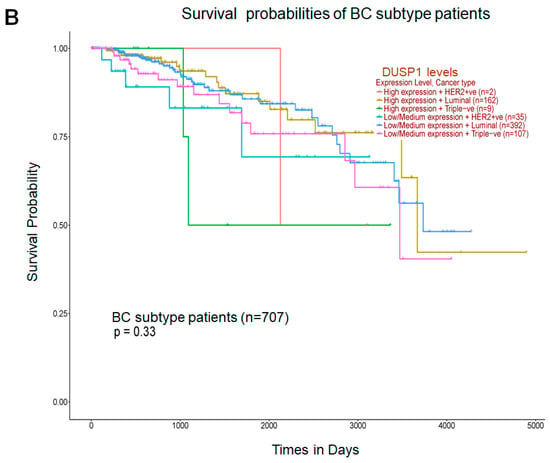

Since DUSP1 modulates chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistance in TNBC, recent emerging evidence also supports that the dysregulation of DUSP1 in TNBC affects immune response and immunotherapy resistance. Lui et al. identified and analyzed the single-cell RNA-sequencing data of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 22 TNBC patients, including 11 pretreatment (PR), 7 stable disease (SD), and 4 partial response (PR) patients who received paclitaxel in combination with anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab) immunotherapy [62]. RNA-sequencing data suggest that there is a significant increase in the myeloid cells in the PR and SD groups, also show an increase in the population of C8: CD8+ NKT cells and C2: classical monocytes in the immunotherapy response group, whereas dendritic cells and non-classical monocytes derived from classical monocytes were decreased. In CD8+ NKT cells and classical monocytes from these treatment groups shows a downregulated ferroptosis-related gene (DDIT4) in CD8+ NKT cells, which can inhibit the activity or proliferation of CD8+ NKT cells. In classical monocytes, the expressions of DUSP1, FTL, BID, CD44, SLC2A3, DDIT4, and JUN genes were significantly associated with the immune response. Further analysis of mutation profiles of differentially expressed FRGs (TCGA transcriptomic data) suggests that in TNBC patients, an increased copy number of DUSP1 and DDIT4 genes, missense mutations in the DUSP1 gene, and nonsense mutations in the DDIT4 gene. Interestingly, the DUSP1 mutation shows worse prognoses for TNBC patients, indicating that DUSP1 may play a crucial role in immunotherapy resistance in TNBC [62]. During neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), patients with TNBC show distinct immune cell-associated gene expression signatures [63]. In the NAC responder, lymphocyte and monocyte populations consistently produce stress response factors such as FOSB, JUN, and JUNB. In monocyte clusters, DUSP1 and DUSP2 showed similar expression patterns in both patients (responder and non-responder). In T/NK cells, however, DUSP1 and DUSP2 remained stable in the responder patient but increased by day 21 in the nonresponder. The exact role of the differential expression DUSP1 in monocyte clusters and T/NK cells, and immune modulation and NAC resistance, remains unknown [63]. Metastatic BC and single-cell transcriptomes of circulating immune cells suggest upregulation of HLA-DQA1, a B-cell-specific gene marker that is associated with antigen presentation. However, DUSP1, CD69, and FOS inflammatory markers expression is downregulated, indicating a less active inflammatory signature in metastatic BC tumors [64]. It will be interesting to investigate the DUSP’s role in immunotherapy modulation and resistance in TNBC. Although TNBC-associated molecular mechanisms, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic implications have been reviewed recently [65], we also represented the possible role of DUSP1 in TNBC during therapies (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A schematic represents the possible role of DUSP1 in TNBC during chemotherapy, RT, and immunotherapy. Created in BioRender. Seneviratne, D. (2026) https://BioRender.com/ll2fa9d (accessed on 10 December 2025).

7. Conclusions

DUSP1 functions as a central, context-dependent regulator of therapeutic response in triple-negative breast cancer, integrating stress-activated MAPK signaling with tumor cell survival and immune modulation across chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. Rather than acting as a uniformly tumor suppressive or tumorigenic factor, DUSP1 exerts divergent effects determined by cellular compartment, treatment context, dominant MAPK axis, and disease stage. Activation of MAPKs drives chemotherapy resistance against doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and cisplatin drugs; however, the impact of these drugs in acquiring chemotherapy resistance in TNBC was not known. Radiation therapy may activate/stabilize DUSP1, as well as MAPKs independently, and activation of anti-inflammatory signaling may attract immunosuppressive MDSCs and macrophages into the tumor microenvironment in order to boost TNBC cell aggressiveness and metastasis. Indeed, for better management of TNBC clinically, increasing TNBC patients’ clinical trials, examining the context-dependent mechanisms of DUSP1, and developing a selective therapeutic approach will be the first steps in pursuing DUSP1-based therapy for TNBC patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.N.; investigation, S.N. and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N., D.S. and D.T.; review and editing, S.N., D.S., J.J. and D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are sincerely thankful for the investigator-initiated trials grant (MDSCC309) to D.S. from Stephenson Cancer Center, Oklahoma University, United States.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DUSP1 | Dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1 |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| HR+ | Hormone receptor positive |

| BRCA1/2 | Breast Cancer gene ½ |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| TP53 | Tumor protein 53 |

| RT | Radiation therapy |

| BC subtypes | Brest cancer subtypes |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| CCND1 | Cyclin D1 gene |

| circRNAs | Circular RNAs |

| BCI | (E)-2-benzylidene-3-(cyclohexylamino)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-one |

| BLBC | Basal-like breast cancer |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

References

- Cheang, M.C.; Martin, M.; Nielsen, T.O.; Prat, A.; Voduc, D.; Rodriguez-Lescure, A.; Ruiz, A.; Chia, S.; Shepherd, L.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; et al. Defining breast cancer intrinsic subtypes by quantitative receptor expression. Oncol. 2015, 20, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Nowak, A.Z.; Romanowicz, H. Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis and Treatment (Review of Literature). Cancers 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aysola, K.; Desai, A.; Welch, C.; Xu, J.; Qin, Y.; Reddy, V.; Matthews, R.; Owens, C.; Okoli, J.; Beech, D.J.; et al. Triple Negative Breast Cancer—An Overview. Hered. Genet. 2013, 2013, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, G. The treatment of breast cancer in the era of precision medicine. Cancer Biol. Med. 2025, 22, 322–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamino, M.A.; López-Knowles, E.; Morani, G.; Tovey, H.; Kilburn, L.; Schuster, E.F.; Alataki, A.; Hills, M.; Xiao, H.; Holcombe, C.; et al. HER2-enriched subtype and novel molecular subgroups drive aromatase inhibitor resistance and an increased risk of relapse in early ER+/HER2+ breast cancer. eBioMedicine 2022, 83, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahvi, D.A.; Liu, R.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Colson, Y.L.; Raut, C.P. Local Cancer Recurrence: The Realities, Challenges, and Opportunities for New Therapies. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, M.; Spada, S.; Van Nest, S.J.; Demaria, S. Radiation therapy-induced remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, S.C.; Rudqvist, N.-P.; Golden, E.; Cooper, B.; Wennerberg, E.; Lhuillier, C.; Vanpouille-Box, C.; Friedman, K.; Ferrari de Andrade, L.; Wucherpfennig, K.W.; et al. Radiotherapy induces responses of lung cancer to CTLA-4 blockade. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1845–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jing, J. Cancer Immunotherapy in Combination with Radiotherapy and/or Chemotherapy: Mechanisms and Clinical Therapy. Medcomm (2020) 2025, 6, e70346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackstone, M.; Baldassarre, F.G.; Perera, F.E.; Cil, T.; Chavez Mac Gregor, M.; Dayes, I.S.; Engel, J.; Horton, J.K.; King, T.A.; Kornecki, A.; et al. Management of the Axilla in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Ontario Health (Cancer Care Ontario) and ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3056–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purrington, K.S.; Slager, S.; Eccles, D.; Yannoukakos, D.; Fasching, P.A.; Miron, P.; Carpenter, J.; Chang-Claude, J.; Martin, N.G.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 25 known breast cancer susceptibility loci as risk factors for triple-negative breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 1012–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.N.; Vachon, C.M.; Couch, F.J. Genetic susceptibility to triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogra, A.K.; Prakash, A.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, M. Prognostic Significance and Molecular Classification of Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Breast Heal 2025, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagami, P.; Carey, L.A. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. npj Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovcaricek, T.; Frkovic, S.; Matos, E.; Mozina, B.; Borstnar, S. Triple negative breast cancer—Prognostic factors and survival. Radiol. Oncol. 2011, 45, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnery, S.E.; Mayer, I.A.; Balko, J.M. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Breast Tumors With an Identity Crisis. Cancer J. 2021, 27, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensenyat-Mendez, M.; Llinàs-Arias, P.; Orozco, J.I.J.; Íñiguez-Muñoz, S.; Salomon, M.P.; Sesé, B.; DiNome, M.L.; Marzese, D.M. Current Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Subtypes: Dissecting the Most Aggressive Form of Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 681476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M.V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes: Implications for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Selection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Altekruse, S.F.; Li, C.I.; Chen, V.W.; Clarke, C.A.; Ries, L.A.; Cronin, K.A. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidiro, O.; Battogtokh, G.; Akala, E.O. Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatment Options and Limitations: Future Outlook. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlader, N.; Cronin, K.A.; Kurian, A.W.; Andridge, R. Differences in Breast Cancer Survival by Molecular Subtypes in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranova, A.; Krasnoselskyi, M.; Starikov, V.; Kartashov, S.; Zhulkevych, I.; Vlasenko, V.; Oleshko, K.; Bilodid, O.; Sadchikova, M.; Vinnyk, Y. Triple-negative breast cancer: Current treatment strategies and factors of negative prognosis. J. Med. Life 2022, 15, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, D.; Al Sendi, M.; Kelly, C.M. Overview of recent advances in metastatic triple negative breast cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 12, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niture, S.; Ghosh, S.; Jaboin, J.; Seneviratne, D. Tumor Microenvironment Dynamics of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Under Radiation Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niture, S.; Mooers, B.H.; Wu, D.H.; Hart, M.; Jaboin, J.; Seneviratne, D. Dual-specificity protein phosphatase 1: A potential therapeutic target in cancer. iScience 2025, 28, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rauch, J.; Kolch, W. Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Tang, G.; Rogers, C.S.; Dove, M.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. OncoDB 2.0: A comprehensive platform for integrated pan-cancer omics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 54, D1537–D1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev Maor, G.; Yearim, A.; Ast, G. The alternative role of DNA methylation in splicing regulation. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shivakumar, M.; Han, S.; Sinclair, M.S.; Lee, Y.-J.; Zheng, Y.; Olopade, O.I.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y. Population-dependent Intron Retention and DNA Methylation in Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Olopade, O.I. MYC and Breast Cancer. Genes Cancer 2010, 1, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffreys, S.A.; Becker, T.M.; Khan, S.; Soon, P.; Neubauer, H.; de Souza, P.; Powter, B. Prognostic and Predictive Value of CCND1/Cyclin D1 Amplification in Breast Cancer With a Focus on Postmenopausal Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 895729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurti, U.; Silverman, J.F. HER2 in breast cancer: A review and update. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2014, 21, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.R.; Wu, Y.-M.; Lonigro, R.J.; Vats, P.; Cobain, E.; Everett, J.; Cao, X.; Rabban, E.; Kumar-Sinha, C.; Raymond, V.; et al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature 2017, 548, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, W.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, G.; Sun, J.; Yu, L. Molecular Features of Triple Negative Breast Cancer: Microarray Evidence and Further Integrated Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Tian, J.; Yuan, F.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.; et al. DUSP1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood leukocyte is associated with triple-negative breast cancer risk. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.T.; Liu, J.; Li, F.; Yang, B.B. Targeting circular RNAs as a therapeutic approach: Current strategies and challenges. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, C.; Tian, X.; Luo, S.; Zeng, J.; Li, J.; Xu, T.; Wang, J. The circDUSP1/miR-429/DLC1 regulatory network affects proliferation, migration, and invasion of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skor, M.N.; Wonder, E.L.; Kocherginsky, M.; Goyal, A.; Hall, B.A.; Cai, Y.; Conzen, S.D. Glucocorticoid Receptor Antagonism as a Novel Therapy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6163–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuglu, M.M.; Bostanabad, S.Y.; Ozyon, G.; Dalkiliç, B.; Gurdal, H. The role of dual-specificity phosphatase 1 and protein phosphatase 1 in β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated inhibition of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 in triple negative breast cancer cell lines. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Sun, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Yao, N.; Cheng, S.; Dong, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, C.; et al. The suppression of DUSP5 expression correlates with paclitaxel resistance and poor prognosis in basal-like breast cancer. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.-J.; Yang, X.; Yu, M.; Li, Q.-C.; Wang, R.-Y.; Yu, W.-Y.; Zhang, J.-L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Zhu, W.-T.; Li, J.; et al. Discovery of aurovertin B as a potent metastasis inhibitor against triple-negative breast cancer: Elucidating the complex role of the ATF3-DUSP1 axis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2025, 392, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, G.W.; Shi, Y.Y.; Higgins, L.S.; Orlowski, R.Z. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Phosphatase-1 Is a Mediator of Breast Cancer Chemoresistance. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 4459–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metin, S.; Altan, H.; Tercan, E.; Dedeoglu, B.G.; Gurdal, H. DUSP1 protein’s impact on breast cancer: Anticancer response and sensitivity to cisplatin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gene Regul. Mech. 2025, 1868, 195103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błaszczak, E.; Miziak, P.; Odrzywolski, A.; Baran, M.; Gumbarewicz, E.; Stepulak, A. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression and Drug Resistance in the Context of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Cancers 2025, 17, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, T.; Wu, F.; McCuaig, R.; Dunn, J.; Sutton, C.R.; Hardy, K.; Tu, W.; Bullman, A.; Yip, D.; Dahlstrom, J.E.; et al. Differential Roles for DUSP Family Members in Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cell Regulation in Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.V.; Martin, E.C.; Segar, H.C.; Miller, D.F.B.; Buechlein, A.; Rusch, D.B.; Nephew, K.P.; Burow, M.E.; Collins-Burow, B.M. Dual regulation by microRNA-200b-3p and microRNA-200b-5p in the inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 16638–16652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Bao, L.; Qu, H.; Xiang, J.; Sun, P. Upregulation of the ferroptosis-related STEAP3 gene is a specific predictor of poor triple-negative breast cancer patient outcomes. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1032364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J.; Ren, F.; Song, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, K.; Li, N. Synergies between radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A systematic review from mechanism to clinical application. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1554499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeaz, C.; Totis, C.; Bisio, A. Radiation Resistance: A Matter of Transcription Factors. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 662840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Shen, B.; Liang, Y.; Jin, R.; Liu, X.; Shi, L.; Cai, X. Role of DUSP1/MKP1 in tumorigenesis, tumor progression and therapy. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, C.C.; Srikanth, S.; Kraft, A.S. Conditional expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1, MKP-1, is cytoprotective against UV-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3014–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staples, C.J.; Owens, D.M.; Maier, J.V.; Cato, A.C.B.; Keyse, S.M. Cross-talk between the p38α and JNK MAPK Pathways Mediated by MAP Kinase Phosphatase-1 Determines Cellular Sensitivity to UV Radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25928–25940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candas, D.; Lu, C.-L.; Fan, M.; Chuang, F.Y.; Sweeney, C.; Borowsky, A.D.; Li, J.J. Mitochondrial MKP1 Is a Target for Therapy-Resistant HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 7498–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candas, D.; Li, J.J. MKP1 mediates resistance to therapy in HER2-positive breast tumors. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 2, e997518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Anorve, I.X.; Gonzalez-De la Rosa, C.H.; Soto-Reyes, E.; Beltran-Anaya, F.O.; Del Moral-Hernandez, O.; Salgado-Albarran, M.; Angeles-Zaragoza, O.; Gonzalez-Barrios, J.A.; Landero-Huerta, D.A.; Chavez-Saldana, M.; et al. New insights into radioresistance in breast cancer identify a dual function of miR-122 as a tumor suppressor and oncomiR. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 1249–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.S.; Pajonk, F.; McCloskey, S.; Low, D.A.; Kupelian, P.; Steinberg, M.; Sheng, K. Radioresistance of the breast tumor is highly correlated to its level of cancer stem cell and its clinical implication for breast irradiation. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 124, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Turnbull, A.K.; Ward, C.; Meehan, J.; Martínez-Pérez, C.; Bonello, M.; Pang, L.Y.; Langdon, S.P.; Kunkler, I.H.; Murray, A.; et al. Development and characterisation of acquired radioresistant breast cancer cell lines. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xie, D.; Bai, C.; Mao, C.; Wang, F.; Guo, X. Serum dual-specificity phosphatase 1 reflects decreased exacerbation risk, correlates with less advanced exacerbation severity and lower inflammatory cytokines in children with asthma. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2022, 50, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemmari, A.; Paukkeri, E.; Hämäläinen, M.; Leppänen, T.; Korhonen, R.; Moilanen, E. MKP-1 promotes anti-inflammatory M(IL-4/IL-13) macrophage phenotype and mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadir, A.; Kavalakatt, S.; Dehbi, M.; Alarouj, M.; Bennakhi, A.; Tiss, A.; Elkum, N. DUSP1 Is a Potential Marker of Chronic Inflammation in Arabs with Cardiovascular Diseases. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 9529621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Gong, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, X. Regulation of ferroptosis-related genes in CD8+ NKT cells and classical monocytes may affect the immunotherapy response after combined treatment in triple negative breast cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2023, 14, 3369–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patysheva, M.R.; Iamshchikov, P.S.; Fedorenko, A.A.; Bragina, O.D.; Vostrikova, M.A.; Garbukov, E.Y.; Cherdyntseva, N.V.; Denisov, E.V.; Gerashchenko, T.S. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of immune landscape in triple-negative breast cancer during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2025, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiola, S.; Brown, R.; Zhan, C.; Berthelet, J.; Guleria, S.; Liyanage, C.; Ostrouska, S.; Wilcox, J.; Merdas, M.; Fuge-Larsen, P.; et al. Circulating immune cells exhibit distinct traits linked to metastatic burden in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2025, 27, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Q. Immunotherapy resistance in triple-negative breast cancer: Molecular mechanisms, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic implications. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1630464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.