Simple Summary

As multiple myeloma (MM) treatments evolve, real-world data is needed to understand how patients are treated and how they respond. The TOTEMM study looked at treatment patterns and outcomes in newly diagnosed MM patients who could not have transplants, using data from private healthcare in Argentina (72 patients) and Brazil (892 patients). Across both countries, many different drug combinations were used, mostly starting with triplet regimens based on bortezomib. Treatment duration shortened with each new line of therapy, while dropout rates increased. Over 75% of patients relapsed within a year, and most relapses happened between the first and second treatment lines. Many were likely to be treated again with the same drug. Around 65% showed disease progression after first-line treatment. The risk of progression or death rose steadily over time. These findings highlight the urgent need for better treatment options for patients with MM.

Abstract

As treatments for multiple myeloma (MM) evolve, there is a need for real-world insights into treatment patterns and outcomes. The treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM (TOTEMM) was a database study (2018–2024) of newly diagnosed transplant-ineligible patients with MM in Argentina (TOTEMM-A) and Brazil (TOTEMM-B) in a private healthcare setting. In TOTEMM-A (n = 72) and TOTEMM-B (n = 892), 37 and 92 different drug regimens were reported, respectively. In each country, treatment duration reduced across lines of therapy (LOT) (TOTEMM-A: range, 6.2–3.4 months; TOTEMM-B: range, 4.4–3.5 months); attrition rates increased across LOT (TOTEMM-A: range, 52.8–86.1%; TOTEMM-B: range, 41.9–88.0%); triplet regimens (mainly bortezomib based) were used most frequently in first-line (1L); >75% relapsed within 12 months, regardless of the drug prescribed; over 90% of relapses occurred between 1L and second-line, and up to half of patients were rechallenged with the same drug; >65% of patients experienced disease progression after 1L; and the 1- to 5-year adjusted cumulative risk of progression or death increased across LOT (TOTEMM-A: range, 47.1–88.5%; TOTEMM-B: range, 40.4–91.7%). The rapid and marked progression underscores the urgent need for novel treatments and regimens.

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell disorder that continues to pose a therapeutic challenge due to its relapsing and incurable nature [1]. Median overall survival (OS) is approximately 5 years, with most patients receiving four or more different lines of therapy (LOT) throughout the course of the disease [2]. Treatments aim to prolong the duration of response, which is critical for newly diagnosed patients [3,4]. The ability to achieve and sustain a meaningful response decreases with every LOT, placing emphasis on the first-line (1L) therapy [5].

Recent epidemiological trends indicate a rise in the prevalence, incidence, disease burden, and mortality for patients with MM in Latin America [6,7,8]. Despite global advances in MM treatment that have improved progression-free survival (PFS) and OS [9,10], the MYCLARE study highlighted persistent disparities in MM management in Latin America [11]. Both Argentina and Brazil provide free public healthcare services, but approximately 16% and 25% of their respective populations opt for coverage by private healthcare insurance [12,13]. Those in the private healthcare setting are considered to have better access to diagnosis and treatment than those in the public healthcare setting [11,14,15,16,17].

Stem cell transplant (SCT) remains the standard of care for eligible patients with MM, but many, often older adults or those with significant comorbidities, are ineligible for this treatment [18]. These transplant-ineligible patients require an alternative, long-term treatment strategy that prioritizes quality of life over aggressive treatment [19,20].

Understanding MM treatment patterns in clinical practice through real-world data is essential for informing decisions made by physicians, payers, and regulators. However, such data, particularly concerning treatment practices beyond 1L and longitudinal treatment patterns including LOT for MM, remain relatively scarce in Latin America (including Argentina and Brazil) [21,22,23]. Much of the existing evidence in the region originates from academic institutions or public reference centers, where access to innovative treatments may be limited [11,17,22,24]. To address this evidence gap, we conducted a real-world study in Argentina and Brazil to evaluate current real-world treatment practices and outcomes in newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients with MM in a private healthcare setting across four LOT.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Population

Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM (TOTEMM) was a retrospective, longitudinal database study that evaluated the treatment patterns of patients with MM using electronic medical records (EMRs) from Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA), Argentina (TOTEMM-A: 1 January 2018–31 May 2024), and administrative claims data from Orizon, São Paulo, Brazil (TOTEMM-B: 1 January 2018–28 February 2024). Included were records of patients from the health insurance companies who were privately insured and aged ≥18 years at the index date and had ≥1 MM-related health term (Table S1)/International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code (C90/C90.0) and ≥1 core drug specific for MM (Table S2). The index date was defined as a proxy of MM diagnosis and could be the first recorded date of an MM-related health term/ICD-10 code (C90/C90.0) or any MM-related treatment or procedure/exam. Eligible patients must have also had their MM classified as an incident case, defined as being treatment-naive for ≥1 year before the first MM treatment (antineoplastic drug, except for corticosteroids [CSs]). Patients who had previously received a SCT (transplant-eligible) were excluded (i.e., patients who received only antineoplastic drugs as a treatment for MM were included in this analysis and were defined as transplant-ineligible). Patients with MM were followed from the index date until lost to follow-up, end of the study period, or death, whichever came first.

2.2. Study Objectives and Variables

The primary objective was to describe treatment practices among transplant-ineligible patients with MM among incident cases, focusing on the LOT (1L; second line [2L], third line [3L], and fourth line [4L]) in a private healthcare community setting in Argentina (TOTEMM-A) and Brazil (TOTEMM-B). Secondary objectives were to describe patient demographics (sex, age at index, and body mass index [BMI] in TOTEMM-A only) and clinical characteristics (duration of follow-up, time to first treatment, time to next treatment [TTNT], duration of treatment, relapse, rechallenge, PFS, and OS) (Table S3).

2.3. Data Source and Collection

For TOTEMM-A, EMRs were obtained from HIBA, a leading private hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina [25]. Among the 16% of the population with private healthcare insurance, more than 175,000 adult members are affiliated with HIBA’s primary insurance provider, Hospital Italiano Medical Care Program [12,25]. The HIBA database reflects patients with private healthcare insurance in Buenos Aires [25]. HIBA offers comprehensive diagnostic and treatment facilities that include more than 40 medical specialties, from primary to tertiary care [25,26]. Patients with MM were identified using relevant health terms (Table S1) related to MM compiled by oncologists from HIBA, who then manually reviewed EMRs to confirm diagnosis.

For TOTEMM-B, administrative health claims data were obtained from Orizon, a database of several private insurers across Brazil. Among the 25% of the population with private healthcare insurance, Orizon covers 59%, encompassing data from 30 million patients, 217,000 health providers, and 14,000 pharmacies [13,27]. The Orizon database reflects patients receiving private care from primary to tertiary levels [27]. Patients with MM were identified using ICD-10 codes (C90, multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms, or C90.0, multiple myeloma).

2.4. Data Analysis

Results were interpreted descriptively and considered the country context of treatment availability, healthcare practices, and the population covered by the database. No country-level generalizations were performed. Analyses were performed using the statistical softwares R (Version 4.2.2) and Stata 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). All analyses were quality controlled by two independent analysts. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviation (SD), interquartile range (IQR), and minimum and maximum values are presented. Categorical variables are presented as absolute counts and percentages. The frequencies of each drug and each combination used were calculated. As the LOT were not explicitly captured through the EMRs and claims data, an algorithm was developed based on the receipt and timing of therapy, along with clinical guidelines, to construct the LOT (Table S4). Therapeutic class combinations related to MM treatment were classified as mono-, doublet, triplet, or quadruplet therapy. For the analysis presented here, monotherapy was defined as the use of a single MM-related drug from one of the drug classes listed in Table S2. Combination therapies were defined as doublet, triplet, and quadruplet therapies when two, three, or four MM-related drugs, respectively, from different classes were prescribed concurrently. Maintenance regimens were reported per the specified LOT rules and were considered part of the treatment line being followed. Kaplan–Meier methodology with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to estimate OS and PFS. Estimated PFS, defined as the time from the beginning of LOT to first progression (new antineoplastic drug or death), and OS, defined as the time from the index date until death (resulting from any cause) The adjusted OS and PFS, including censored time by loss to follow-up, were also evaluated.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

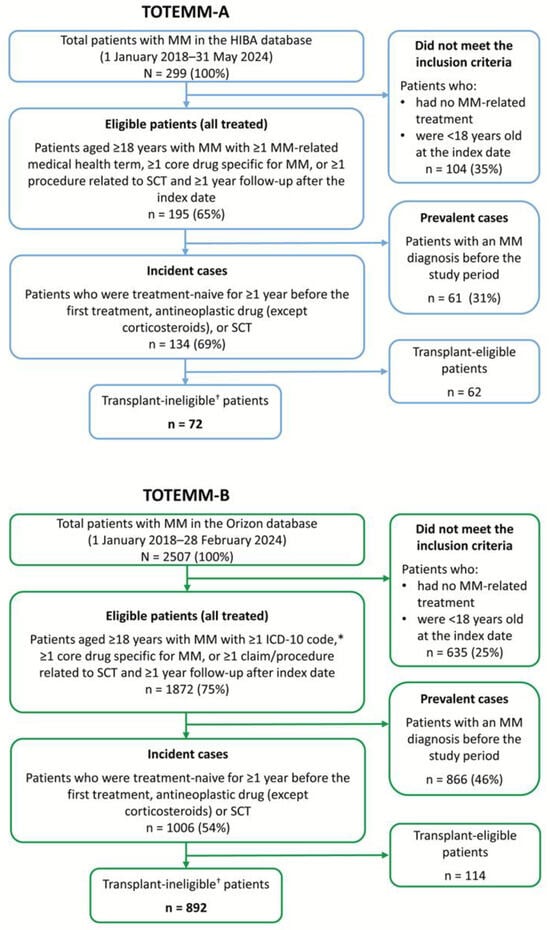

We analyzed data from 72 and 892 transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed MM in Argentina (TOTEMM-A) and Brazil (TOTEMM-B), respectively (Figure 1); their demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, in TOTEMM-A, of the 72 transplant-ineligible patients, 41.7% were male, 90.3% were ≥60 years old, and the mean (SD) age at the index date was 76.5 (9.5) years, with a median (IQR) time to follow-up of 19.1 (35.9) months. The proportions of patients declined across LOT: 47.2% in 2L, 31.9% in 3L, and 13.9% in 4L. In TOTEMM-B, of the 892 transplant-ineligible patients, 58.0% were male, 64.6% were ≥60 years old, and the mean (SD) age at the index date was 64.1 (12.3) years, with a median (IQR) time to follow-up of 20.8 (29.7) months. The proportions of patients declined across LOT: 58.1% in 2L, 29.5% in 3L, and 12.0% in 4L.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study populations. * C90, multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms, and C90.0, multiple myeloma. † Patients who received only antineoplastic drugs as a treatment for MM were included in this analysis. HIBA = Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires; ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision; MM = multiple myeloma; SCT = stem cell transplant.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Transplant-Ineligible Patients With MM.

3.2. LOT Duration and Time to Next Treatment

In TOTEMM-A, the median (IQR) LOT durations (months) for 1L, 2L, 3L, and 4L were 6.2 (6.8), 3.8 (9.0), 5.6 (11.7), and 3.4 (9.7), respectively (Table 1). In TOTEMM-B, the median (IQR) LOT durations (months) for 1L, 2L, 3L, and 4L were 4.4 (5.2), 2.8 (8.0), 4.3 (10.6), and 3.5 (10.9), respectively (Table 1).

The median (IQR) times from the index date until first treatment were 0.4 (1.4) and 0.0 (0.6) months in TOTEMM-A and TOTEMM-B, respectively (Table 1). The median (IQR) TTNT decreased in subsequent LOT from 7.8 (7.6) months (1L to 2L) to 6.2 (7.2) months (2L to 3L) and 5.4 (6.0) months (3L to 4L) in TOTEMM-A (Table 1). Similarly, in TOTEMM-B, median (IQR) TTNT decreased from 7.8 (7.4) months (1L to 2L) to 4.6 (7.7) months (2L to 3L) but then increased to 7.2 (10.2) months (3L to 4L) (Table 1).

3.3. Treatment Tendencies Across LOT

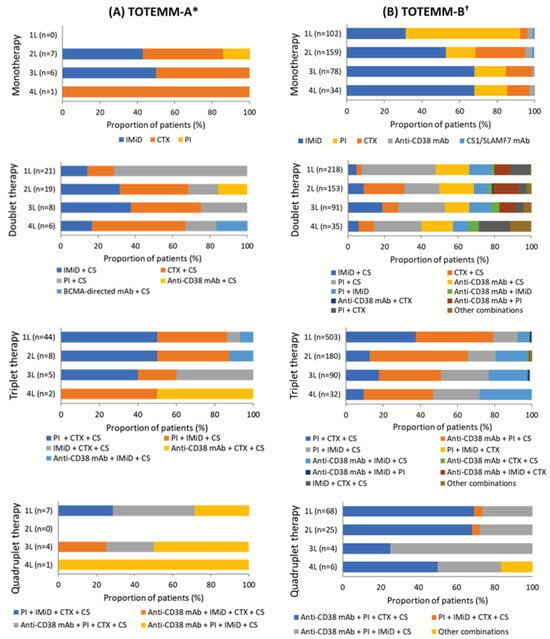

In TOTEMM-A, among the 72 transplant-ineligible patients, there were 17 different therapeutic class combinations (Table S5) and 37 different drug regimens reported across the study period. The proportions of patients who received mono- (range, 0.0–26.1%), doublet (range, 29.2–60.0%), triplet (range, 20.0–61.1%), and quadruplet (range, 0.0–17.4%) therapy in 1L to 4L varied (Figure S1, Table S5). In 1L, triplet therapy was the most frequently prescribed approach (61.1%; n = 44/72). Among these patients, half (50.0%; n = 22/44) received a combination of a proteasome inhibitor (PI) + chemotherapy (CTX) + CS (Figure 2A, Table S5), with all patients within the combination receiving bortezomib + cyclophosphamide + CS (100.0%; n = 22/22). In 2L, doublet therapy was used most frequently (55.9%; n = 19/34), particularly CTX + CS (36.8%; n = 7/19) (Figure 2A, Table S5). Within this combination, melphalan + CS was most frequent (57.1%; n = 4/7). This pattern continued into 3L, in which doublet therapy remained the most common approach (34.8%; n = 8/23). CTX + CS and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) + CS were equally prevalent (each 37.5%; n = 3/8) (Figure 2A, Table S5), with all patients in these groups receiving cyclophosphamide + CS or lenalidomide + CS (each 100%, n = 3/3). In 4L, doublet therapy remained prevalent (60.0%; n = 6/10), with CTX + CS used in half of these cases (50.0%; n = 3/6) (Figure 2A, Table S5). Among these patients, the most common drug combination was cyclophosphamide + CS (66.7%; n = 2/3). Notably, 83.3% (n = 60/72) of patients received PI-based treatment in 1L (Table S7). Moreover, of all patients who received triplet therapy in 1L to 4L, 83.1% (n = 49/59) received PI-based therapy (Table S5).

Figure 2.

Use of therapeutic classes per LOT in transplant-ineligible patients with MM. The drugs considered to be a CS were dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisone, and prednisolone. * Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina; 1 January 2018–31 May 2024. † Orizon, Brazil; 1 January 2018–28 February 2024. 1L/2L/3L/4L = first/second/third/fourth line; BCMA = B-cell maturation antigen; CS = corticosteroid; CTX = chemotherapy; IMiD = immunomodulatory drug; mAb = monoclonal antibodies; MM = multiple myeloma; PI = proteasome inhibitor; SLAMF7 = signaling lymphocyte activation molecule family member 7; TOTEMM = Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM.

In TOTEMM-B, among the 892 transplant-ineligible patients, there were 36 different therapeutic class combinations (Table S6) and 92 different drug regimens reported across the study period in TOTEMM-B. The proportions of patients who received mono- (range, 11.4–31.8%), doublet (range, 24.4–34.6%), triplet (range, 29.9–56.4%), and quadruplet (range, 1.5–7.6%) therapy in 1L to 4L varied (Figure S1, Table S6). In 1L, triplet therapy emerged as the most common approach (56.4%; n = 503/892). Among these patients, 41.6% (n = 209/503) received a combination of anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) + PI + CS (Figure 2B, Table S6). The most frequently used regimen within this group was daratumumab + bortezomib + CS, accounting for 95.2% of cases (n = 199/209). This pattern continued into 2L, in which triplet therapy remained the most common approach (34.7%; n = 180/518). More than half of these patients (52.8%, n = 95/180) received an anti-CD38 mAb + PI + CS combination (Figure 2B, Table S6), with daratumumab + bortezomib + CS again being the most prevalent (85.3%; n = 81/95). In 3L, the uses of doublet and triplet therapy were nearly equal, at 34.6% (n = 91/263) and 34.2% (n = 90/263), respectively (Figure 2B, Table S6). Among those receiving doublet therapy, the most common regimen was PI + CS (25.3%, n = 23/91) (Figure 2B, Table S6), with carfilzomib + CS used in more than half of these cases (52.2%, n = 12/23). For patients on triplet therapy, one-third (33.3%, n = 30/90) received anti-CD38 mAbs + PI + CS (Figure 2B, Table S6), with daratumumab + bortezomib + CS being the most frequent drug combination (46.7%, n = 14/30). In 4L, doublet therapy was the most frequently prescribed approach (32.7%, n = 35/107), with one-quarter of patients receiving PI + CS (25.7%, n = 9/35) (Figure 2B, Table S6); among them, over half received carfilzomib + CS (55.6%, n = 5/9). Monotherapy in 4L followed closely (31.8%, n = 34/107), with IMiDs being the most frequently used class (67.6%, n = 23/34) (Figure 2B, Table S6); notably, all patients in this group received lenalidomide (100.0%, n = 23/23). Similarly, nearly one-third of patients (29.9%, n = 32/107) received triplet therapy in 4L, with anti-CD38 mAbs + PI + CS being the most common combination (37.5%, n = 12/32) (Figure 2B, Table S6) and daratumumab + carfilzomib + CS the most frequently used regimen within this group (66.7%, n = 8/12). Notably, 85.4% (n = 762/892) of patients received PI-based treatment in 1L (Table S7). Moreover, of all patients who received triplet therapy in 1L to 4L, 87.8% (n = 707/805) received PI-based therapy (Table S6).

3.4. Evolving Treatment Tendencies over Time

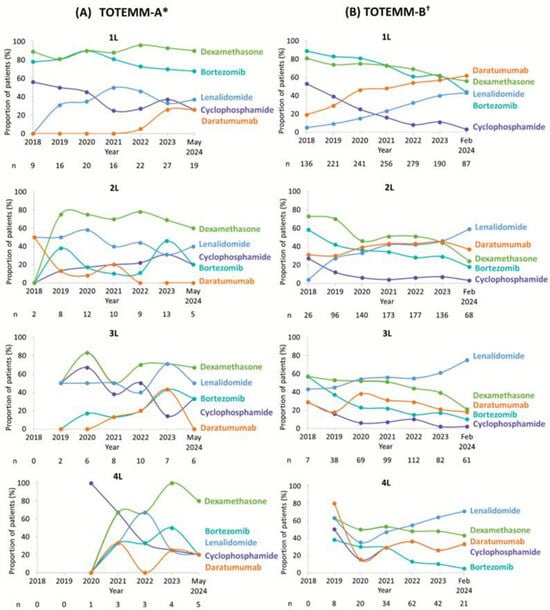

Treatment utilization observations for the most common MM-related treatments in each class across LOT over the study period in TOTEMM-A (1 January 2018–31 May 2024) and TOTEMM-B (1 January 2018–28 February 2024) are shown in Figure 3A,B, respectively.

Figure 3.

MM-related treatments over time per LOT for transplant-ineligible patients with MM. Due to the study design, patients with newly diagnosed MM (i.e., incident cases) in 2018 would not have had time to receive 3L or 4L treatment; therefore, no patients received 3L or 4L (in TOTEMM-B) in 2018. * Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina; 1 January 2018–31 May 2024. † Orizon, Brazil; 1 January 2018–28 February 2024. 1L/2L/3L/4L = first/second/third/fourth line; LOT = line of therapy; MM = multiple myeloma; TOTEMM = Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM.

In TOTEMM-A, 1L usage of dexamethasone and bortezomib was consistently high, whereas cyclophosphamide use declined steadily. Lenalidomide and daratumumab showed increasing uptake over time. In 2L, the use of dexamethasone slightly declined, lenalidomide showed fluctuating use with a downward trend, and cyclophosphamide use slightly increased. Due to the natural course of disease progression, only a small number of newly diagnosed patients with MM in 2018 advanced to 3L or 4L therapy within the same year, resulting in limited availability of data for that period. Moreover, ten or fewer patients per year were included in the analysis for 3L and five or fewer patients per year were included in the analysis for 4L; thus, making any observations is challenging, and no apparent treatment trends are noted.

In TOTEMM-B, in 1L and 2L, there was a clear shift away from bortezomib, dexamethasone, and cyclophosphamide, with all three showing consistent declines in usage. In contrast, daratumumab and lenalidomide usage increased steadily over time. In 3L, a similar downward trend was observed for bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and daratumumab, whereas lenalidomide use rose notably, reaching 75.4% by 2024. In 4L, as mentioned above, no observations regarding treatment use in 4L were possible in 2018; thus, data are shown from 2019 onward. A general decline in bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and daratumumab was noted, while lenalidomide continued its upward trend.

3.5. Relapse and Rechallenge

In TOTEMM-A, among the 33 patients who relapsed during the study period, the median (IQR) time to first relapse (a relapse was considered a progression of LOT; patients should have received ≥2 LOT and ≥1 MM-related core drug) from the start of exposure to bortezomib and/or daratumumab and/or lenalidomide to a subsequent LOT was 7.9 (6.7) months, with 75.8% occurring within 12 months (Table 2). Of these patients, 93.9% (n = 31) experienced relapse at 2L, with a median (IQR) time to relapse of 7.8 (7.3) months. Of the 28 patients exposed to bortezomib, 75.0% (n = 21) relapsed within 12 months of treatment initiation. Among the 11 patients exposed to lenalidomide, 63.6% (n = 7) relapsed within 12 months. Of all three patients exposed to daratumumab, 100.0% (n = 3) relapsed within 12 months (Table 2). Of the number of patients exposed to treatment in 1L who relapsed, rechallenge (use of the same drug at the subsequent LOT) in 2L was reported for 18.5% (n = 5/27) with bortezomib, none with carfilzomib or daratumumab, and 10.0% (n = 1/10) with lenalidomide (Table 3). Attrition rates across LOT were 52.8% from 1L to 2L (n = 38/72), 68.1% from 2L to 3L (n = 11/34), and 86.1% from 3L to 4L (n = 13/23) (Table 1).

Table 2.

Relapse exposure across LOT in transplant-ineligible patients with MM.

Table 3.

Frequency of rechallenge * after relapse † across LOT in transplant-ineligible patients with MM.

In TOTEMM-B, among the 512 patients who relapsed, the median (IQR) time to first relapse from the start of exposure to bortezomib and/or daratumumab and/or lenalidomide to a subsequent LOT was 7.8 (7.2) months, with 75.4% occurring within 12 months (Table 2). The majority of relapses occurred between 1L and 2L. Of the 444 patients exposed to bortezomib, 77.3% (n = 343) relapsed within 12 months of treatment initiation. Among the 85 patients exposed to lenalidomide, 76.5% (n = 65) relapsed within 12 months. Of the 188 patients exposed to daratumumab, 73.9% (n = 139) relapsed within 12 months (Table 2). Of the number of patients exposed to treatment in 1L who relapsed, rechallenge in 2L was reported for 42.7% (n = 189/443) with bortezomib, 35.0% (n = 7/20) with carfilzomib, 44.6% (n = 83/186) with daratumumab, and 53.0% (n = 44/83) with lenalidomide (Table 3). Attrition rates across LOT were 41.9% from 1L to 2L (n = 374/892), 70.5% from 2L to 3L (n = 255/518), and 88.0% from 3L to 4L (n = 156/263) (Table 1).

3.6. Estimated Progression-Free Survival

The estimated PFS time was defined as the time from the beginning of LOT to first progression (new antineoplastic drug or death), considering transplant-ineligible patients with MM in Argentina and Brazil. Progression events after 1L, 2L, 3L, and 4L occurred in 69.4% (n = 50/72), 82.4% (n = 28/34), 69.6% (n = 16/23), and 50.0% (n = 5/10) of patients, respectively, in TOTEMM-A, and 66.3% (n = 591/892), 57.7% (n = 299/518), 49.0% (n = 129/263), and 47.7% (n = 51/107), respectively, in TOTEMM-B (Table 4). In TOTEMM-A, the median (P25–P75) estimated survival times (months) of PFS from the start of LOT were 9.7 (4.4–18.9) in 1L, 6.6 (3.7–29.1) in 2L, 9.6 (5.3–14.3) in 3L, and 13.3 (4.6–na) in 4L (Table 4). In TOTEMM-B, the median (P25–P75) estimated survival times (months) of PFS from the start of LOT (excluding the time of censored patients by loss to follow-up) were 10.0 (5.6–23.4) in 1L, 10.5 (3.4–39.6) in 2L, 15.1 (5.6–50.5) in 3L, and 19.2 (4.1–54.2) in 4L (Table 4).

Table 4.

Survival analysis for estimated PFS per LOT of transplant-ineligible patients with MM.

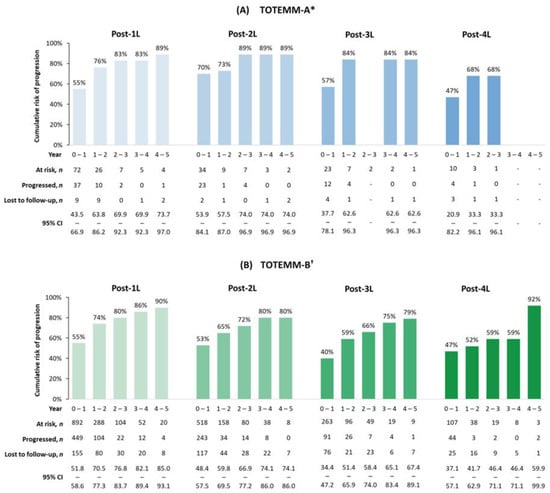

The 1- to 5-year adjusted cumulative risks of progression or death generally increased across all LOT. In TOTEMM-A (Figure 4A), for 1L, the risk ranged from 54.8% in year 1 to 88.5% by year 5. Similarly, in 2L, risks increased from 69.7% in year 1 to 88.5% by year 5. In the 3L setting, the risk ranged from 57.1% to 83.5%, with an absence of progression events observed at year 3. In 4L, there was an initial lower risk of 47.1% at year 1, with an absence of progression events observed from year 3 onward. In TOTEMM-B (Figure 4B), for 1L, the risk ranged from 55.1% in year 1 to 89.5% by year 5. In 2L treatment, there was a similar upward trend, with risks increasing from 52.9% in year 1 to 80.4% by year 5. In 3L, the risk rose from 40.4% in year 1 to 79.3% by year 5. In 4L, risk ranged from 46.6% in year 1 to 91.7% by year 5.

Figure 4.

Cumulative risks of progression or death in transplant-ineligible patients with MM. * Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina; 1 January 2018–31 May 2024. † Orizon, Brazil; 1 January 2018–28 February 2024. 1L/2L/3L/4L = first/second/third/fourth line; CI = confidence interval; MM = multiple myeloma; TOTEMM = Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM.

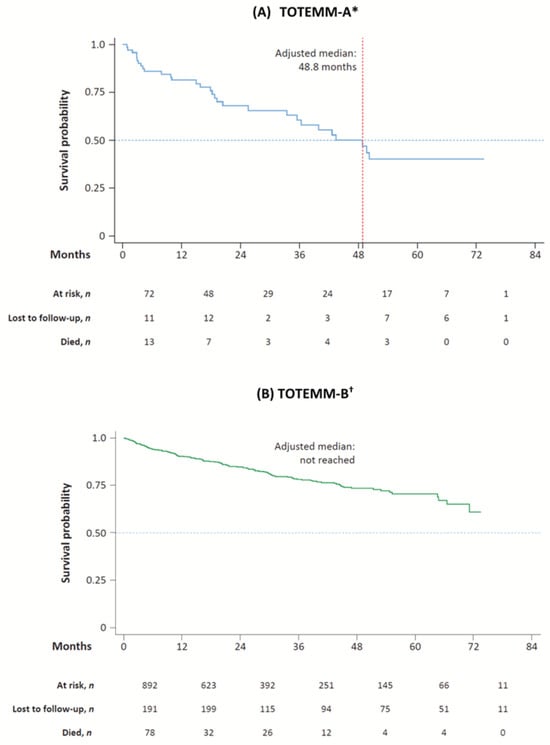

3.7. Overall Survival

Kaplan–Meier curves for adjusted OS estimates among transplant-ineligible patients with MM from Argentina and Brazil are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for OS of transplant-ineligible patients with MM. * Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina; 1 January 2018–31 May 2024. † Orizon, Brazil; 1 January 2018–28 February 2024. MM = multiple myeloma; OS = overall survival; TOTEMM = Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM.

In TOTEMM-A, the adjusted median OS time was 48.8 months; 30 deaths were registered during the study period (41.7% of 72 incident cases), and the median (IQR) time from index to death was 16.8 (31.9) months (Table S8). The 1- to 5-year cumulative survival rates were 80.5%, 67.0%, 59.9%, 49.2%, and 38.3%, respectively (Table S9).

In TOTEMM-B, the adjusted median OS time was not reached; 156 deaths were registered during the study period (17.5% of 892 incident cases), and the median (IQR) time from index to death was 11.9 (22.3) months (Table S8). The 1- to 5-year cumulative survival rates were 90.2%, 84.7%, 78.1%, 73.5%, and 70.8%, respectively (Table S9).

4. Discussion

TOTEMM-A and TOTEMM-B provide valuable insights into current real-world treatment patterns and outcomes (2018–2024) for transplant-ineligible patients with MM within the private healthcare sector in Argentina and Brazil. The studies found that more than 75% of patients experienced disease relapse within 12 months after starting 1L therapy, with most relapses occurring between 1L and 2L, which indicates a consistent pattern of limited durability of response in the frontline setting. There was notable variability in treatment approaches in later LOT, with triplet regimens being prevalent in early LOT. Many patients were rechallenged with the same drug class they received in 1L, particularly in Brazil. The studies highlight the urgent need for more effective and durable therapies, especially at first relapse, to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Despite advances in treatment, the high attrition rates and progressively shorter survival rates across successive LOT underscore this necessity. Our findings are notable given that patients in the private healthcare system have greater access to novel treatments, compared with patients who rely solely on public healthcare systems [11,13,14,15,28]. This is reinforced by the MYLACRE study, which revealed significant shortcomings in the management of MM in Latin America, with disparities in patient profiles, clinical presentation, treatment approaches, transplant eligibility, and long-term outcomes between the public and private healthcare sectors [11].

We observed variation in treatment patterns across LOT among transplant-ineligible patients in both Argentina and Brazil in the private healthcare setting. According to the TOTEMM-A analysis, triplet regimens were used predominantly in 1L, particularly PI + CTX + CS, with bortezomib-based regimens being most common. Doublet therapy regimens gained prominence in subsequent LOT, particularly CTX + CS and IMiD + CS, reflecting a lack of response to previous LOT and limited access to agents with novel mechanisms of action. The diversity of therapeutic strategies was reflected in the 17 class combinations and 37 unique antineoplastic drug regimens across the study period (January 2018–May 2024), with notable shifts in drug utilization trends. Bortezomib and dexamethasone maintained high usage in 1L, whereas cyclophosphamide use declined. The use of bortezomib-based 1L therapy is consistent with the Haemato-Oncology Latin America (HOLA) observational study, which reported a significant increase in bortezomib-based 1L therapy across Latin America from 2008 to 2015 [6,21]. Lenalidomide and daratumumab showed increasing uptake in later years, particularly in 3L, consistent with global recommendations in MM management [2,29]. Likewise, the diversity of treatments was notable in TOTEMM-B, with 36 therapeutic class variations and 92 distinct regimens reported. In Brazil, as in the TOTEMM-A analysis for Argentina and other real-world studies [9,21], triplet regimens were used most commonly in 1L, notably daratumumab + bortezomib + CS. In later LOT, treatment patterns diversified with a transition toward doublet therapy and monotherapy approaches, often involving lenalidomide or carfilzomib. Over the study period (January 2018–February 2024), there was declining use of bortezomib, dexamethasone, and cyclophosphamide, alongside increased adoption of daratumumab and lenalidomide, reflecting evolving clinical practice and drug availability in Brazil’s private healthcare sector [6,30].

In the TOTEMM-A and TOTEMM-B studies, the high rate (>75%) of early relapse observed with 1L agents, including bortezomib, daratumumab, and lenalidomide, indicates a consistent pattern of limited durability of response in the frontline setting and the need for novel agents and treatment combinations. Among those who experienced a relapse, many patients were likely to be rechallenged using the same antineoplastic drug they received in 1L and 2L. These findings align with those of other real-world studies, [31,32] including a US-based real-world study conducted between 2011 and 2017, which reported that a significant proportion of patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) MM were re-treated with a regimen containing agents previously used in 1L [33]. Furthermore, the higher rates of rechallenge in 2L observed in TOTEMM-B compared with TOTEMM-A, particularly for lenalidomide and daratumumab, may reflect evolving clinical practice patterns influenced by variations in access to novel treatments or improved tolerability and efficacy perceptions [6,34]. A recent systematic literature review indicated that anti-CD38–based re-treatment provided limited and variable clinical improvements in PFS and OS in patients with R/R MM [35]. Likewise, the LocoMMotion study demonstrated poor clinical outcomes in triple-class–exposed patients (who received at least a PI, IMiD, and anti-CD38 mAb) with R/R MM in a real-world setting, reinforcing the need for therapies with novel mechanisms of action [36].

The high attrition rates (Argentina, 52.8–86.1%; Brazil, 41.9–88.0%) across LOT seen in this study align with those in a US-based study, which reported attrition rates of 43–57%, emphasizing the necessity for enhanced treatment approaches [5,37]. In addition, the declines in treatment duration in Argentina (6.2 months in 1L to 3.4 months in 4L) and Brazil (4.4 months in 1L to 3.5 months in 2L) were steeper than that observed in the US cohort (6.9 months in 1L to 5.7 months in 4L) [5]. Compared with other regions, a potential reason for the shorter treatment duration and high attrition rates observed in Argentina and Brazil may partly be due to limited or delayed access to novel drugs and treatment combinations in the Latin American region [11,30]. Furthermore, the drugs used may differ among healthcare providers, influenced by access constraints and local guidelines, such as those from the Society of Hematology in Argentina (SAH) and the Brazilian Medical Association (AMB) [30,38,39].

In Argentina and Brazil, more than 65% of transplant-ineligible patients with MM experienced disease progression after 1L therapy, compared with 43% in a US-based study [5]. Moreover, high progression rates across later LOT (TOTEMM-A, 50.0–82.4%; TOTEMM-B, 47.7–57.7%) and increasing 1- to 5-year adjusted cumulative risk of progression or death after 1L (TOTEMM-A, 54.8–88.5%; TOTEMM-B, 55.1–89.5%, respectively) suggest limited durability of response and rapid disease progression despite ongoing treatment. The median PFS durations in 1L and 2L in TOTEMM-A (1L, 9.7 months; 2L, 6.6 months) and TOTEMM-B (1L, 10.0 months; 2L, 10.5 months) were generally consistent with those in previous studies from the region. For instance, in the study in Latin America, median PFS times following 1L and 2L were 15.0 and 10.9 months, respectively, in transplant-ineligible patients diagnosed with MM from 2008 to 2015 [21]. In contrast, in the US-based CONNECT Registry real-world study, patients without a transplant with MM from 2009 to 2016 had median PFS durations of 21.5 and 7.3 months after 1L and 2L, respectively [40].

Recent advancements in MM treatment have raised expectations for median OS beyond 5 years in transplant-ineligible patients [2]. Notably, the OS data (median, 48.8 months) from TOTEMM-A fall short of the global 5-year expectations [2], as many studies have reported median OS figures exceeding this benchmark [41,42,43], although these figures still surpass those of Latin America. In contrast, TOTEMM-B OS data (no median OS reached) align with global expectations and exceed OS data from previous studies in the region [11,21,23]. Although speculative, differences in comorbidities may have contributed to the observed outcomes, given that patients in TOTEMM-A (mean, 76.5 years) are notably older than those in TOTEMM-B (mean, 64.1 years). Between 2016 and 2021, the MYLACRE study reported a median OS of 48.7 months for patients in Latin America, representing those from the public and private sectors and those who have or have not undergone SCT [11]. Among transplant-ineligible patients, the median OS decreased to 37.4 months [11]. It is important to note that methodologies for measuring OS can vary; in the MYLACRE study, OS was measured from treatment onset, whereas in the TOTEMM study, OS was measured from diagnosis. Another consideration is the variability in data collection methods; the MYLACRE study involved expert-led data collection [11], whereas the TOTEMM study reflects data from the treated population followed by physicians with various levels of clinical expertise. These variations highlight the different methodologies used to analyze mortality data and reinforce the importance of contextualizing survival data from the literature.

Since the databases used were not designed primarily for research purposes, the analyses may have been limited by the variables available within them. Notably absent from these datasets were clinically relevant variables such as cancer stage classification, cytogenetic or molecular testing results, and laboratory values, including renal function. Moreover, the potential reasons for a patient’s transplant ineligibility (e.g., frailty score, social support assessment, patient refusal, financial hardship and/or associated comorbidities), loss of follow-up (e.g., switching to a different insurer not included in the database, a change to public healthcare, transferring care to a different hospital, or true cessation of healthcare utilization), and cause of death were not captured in these databases. Clinical care information from outside oncology clinics may be missing or underreported, potentially resulting in misclassification of treatments and outcomes. Of note, although the number of deaths was reported in this study, owing to the nature of the data sources, not all death events were necessarily captured and may be underrepresented. For example, a patient who may have died at home, whose death was not captured in the system, was censored in the dataset instead. As thalidomide is offered in the public setting, its use was not captured in the TOTEMM-B private database setting. Other limitations of the study are typical of retrospective analyses, including those related to the quality of the database, availability of relevant clinical information, and accurate coding of diagnoses, procedures, and medications. Any potential coding inaccuracies may have led to misidentification of cases. To address this limitation, for TOTEMM-A data, oncologists at HIBA manually reviewed the extracted data to confirm diagnoses and verify treatments. In Brazil, healthcare providers are not required to include ICD-10 codes for procedures. As a result, a manual evaluation was conducted on procedures, exams, and treatments related to MM that lacked an ICD-10 code. Moreover, all analyses were quality controlled by two independent analysts. Direct comparisons between the Argentinian and Brazilian data were not performed, as the study was not statistically powered for such analyses, and the databases differed in the context of the source; however, all algorithms used to identify the number of deaths, LOT transitions, and censoring rules were standardized for use in both datasets. Although generalizability is limited to the overall population within the private healthcare setting, the study provides valuable insights relevant to this region.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate high progression, relapse, and attrition rates among transplant-ineligible patients with MM in Argentina and Brazil, with most progression events occurring within 6 months across LOT. Across all LOT, the adjusted cumulative risks of progression and death consistently rose over the 1- to 5-year period. Despite treatment advances, relapse within 1 year of starting 1L therapy was common, particularly between 1L and 2L. Use of triplet regimens, especially anti-CD38–based combinations, was prevalent in early LOT. Treatment variability and frequent rechallenge with the same drug class were notable, and fewer patients reached later LOT over time. These findings highlight the urgency for novel, more effective, durable therapies at first relapse to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. This knowledge is particularly valuable as we navigate the increasingly complex and rapidly evolving treatment landscape for MM, providing essential evidence-based insights for advancing patient care as clinicians gain more experience with novel antineoplastic drugs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol33010016/s1, Table S1: Health terms related to MM; Table S2: Treatment agents indicated for MM treatment; Table S3: Variables related to treatment outcomes; Table S4: Algorithm for identifying LOT based on treatment dates and clinical guidelines; Table S5: 1L–4L treatments in transplant-ineligible patients with MM among incident cases in TOTEMM-A; Table S6: 1L–4L treatments in transplant-ineligible patients with MM among incident cases in TOTEMM-B; Table S7: Core 1L–4L MM drug use in transplant-ineligible patients with MM among incident cases in TOTEMM-A and TOTEMM-B; Table S8: Mortality and OS of transplant-ineligible patients with MM among incident cases; Table S9: OS of transplant-ineligible patients with MM for all incident cases per year of follow-up; Figure S1: Treatment combinations across LOT for transplant-ineligible patients with MM.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported: Conceptualization: V.H., A.M., M.P.d.L., C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A., G.B., S.T., M.C. and R.J.P.d.M.F. Methodology: C.S. (Claudia Soares), J.Q. and G.A. Software: C.S. (Claudia Soares) and J.Q. Validation: C.S. (Claudia Soares), J.Q., G.A. and M.C. Formal analysis: C.S. (Claudia Soares) and J.Q. Investigation: C.S. (Claudia Soares). Resources: C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A. and B.A. Data curation: G.R., P.S., C.S. (Cristian Seehaus), E.B., N.S., D.F., C.S. (Claudia Soares), J.Q., M.C., V.A.S. and T.B.T.F. Writing—Original draft preparation: R.J.P.d.M.F., C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A., J.Q. and B.A. Writing—Review and editing: V.H., A.M., R.J.P.d.M.F., M.P.d.L., G.R., P.S., C.S. (Cristian Seehaus), E.B., N.S., D.F., C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A., J.Q., G.B., S.T., M.C., V.A.S., T.B.T.F. and B.A. Visualization: V.H., R.J.P.d.M.F., C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A., J.Q., S.T. and B.A. Supervision: C.S. (Claudia Soares), G.A., and B.A. Project administration: C.S. (Claudia Soares) and G.A. Funding acquisition: C.S. (Claudia Soares). All authors took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the manuscript; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GSK, Brazil (study numbers 300465 and 300464).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Publication or report of the study data did not include participant identifiers; therefore, neither informed consent nor GSK ethics committee/institutional review board approval was required. The study was approved by Hospital Italiano’s Ethics Committee in line with their ethics policy.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to this study using existing, fully de-identified data and the patient(s) cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers. No direct patient contact or primary collection of individual human patient data occurred in this study; therefore, informed consent was not required. This study complied with all applicable laws regarding patient privacy, according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized subject-level data used for this publication were obtained from the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Orizon, São Paulo, Brazil. GSK was accountable for the statistical analysis of the study. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Thiago Luiz Nogueira, Patricia Menezes, Tatiana Ricca, Vivian Cristina Paneque, Michel Lima de Moraes, and Mariana de Barros Araujo for their valuable contributions to this manuscript. Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including preparation of the draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors, collating and incorporating authors’ comments for each draft, assembling tables, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Pallavi Patel, ISMPP CMPP™, of Luna, OPEN Health Communications, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022; accessed on 19 December 2025). This support was funded by GSK.

Conflicts of Interest

V.H. declares receiving honoraria from Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Takeda. A.M. declares receiving honoraria from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda and consultancy from Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. R.J.P.d.M.F. declares receiving honoraria as a speaker and on advisory boards from Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi. C. Seehaus, M.P.d.L., P.S., E.B., N.S., D.F., V.A.S., and T.B.T.F. have no conflicts of interest to declare. G.R. declares receiving honoraria as a speaker from Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi and for advisory boards for GSK, Janssen, Pfizer, and Sanofi. C. Soares was an employee of GSK and held financial equities in GSK at the time of the study. G.A. and J.Q. are complementary employees of GSK and do not hold financial equities in GSK. G.B., S.T., M.C., and B.A. are employed by GSK and hold financial equities in GSK.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1L/2L/3L/4L | first/second/third/fourth line |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CS | corticosteroid |

| CTX | chemotherapy |

| EMR | electronic medical record |

| HIBA | Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision |

| IMiD | immunomodulatory drug |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| LOT | line(s) of therapy |

| mAb | monoclonal antibody |

| MM | multiple myeloma |

| OS | overall survival |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| PI | proteasome inhibitor |

| R/R | relapsed/refractory |

| SCT | stem cell transplant |

| SD | standard deviation |

| TOTEMM | Treatment practices and clinical outcomes in patients with MM |

| TTNT | time(s) to next treatment |

References

- Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A.; Barsouk, A.; Rawla, P.; Vakiti, A.; Kolhe, R.; Kota, V.; Ajebo, G.H. Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhael, J.; Ismaila, N.; Cheung, M.C.; Costello, C.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; Kumar, S.; Lacy, M.; Lipe, B.; Little, R.F.; Nikonova, A.; et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma: ASCO and CCO joint clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1228–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohty, M.; Terpos, E.; Mateos, M.-V.; Cavo, M.; Lejniece, S.; Beksac, M.; Bekadja, M.A.; Legiec, W.; Dimopoulos, M.; Stankovic, S.; et al. Multiple myeloma treatment in real-world clinical practice: Results of a prospective, multinational, noninterventional study. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018, 18, e401–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguese, A.J.; Banerjee, R.; Chen, G.; Reddi, S.; Cowan, A.J. Novel Treatment Options for Multiple Myeloma. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 950–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, R.; Usmani, S.Z.; Mehra, M.; Slavcev, M.; He, J.; Cote, S.; Lam, A.; Ukropec, J.; Maiese, E.M.; Nair, S.; et al. Frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by subsequent lines of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes Hungria, V.T.; Peña, C.; Gomez-Almaguer, D.; Martínez-Cordero, H.; Schütz, N.P.; Blunk, V. Multiple myeloma in Latin America: A systematic review. EJHaem 2024, 5, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Argentina. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/32-argentina-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Brazil. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/76-brazil-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kumar, S.K.; Dispenzieri, A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Gertz, M.A.; Buadi, F.K.; Pandey, S.; Kapoor, P.; Dingli, D.; Hayman, S.R.; Leung, N.; et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: Changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, N.S.; Baljevic, M.; Adekola, K.; Anderson, L.D.; Campagnaro, E.; Castillo, J.J.; Costello, C.; Devarakonda, S.; Elsedawy, N.; Faiman, M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: Multiple myeloma, version 3.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2022, 20, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, V.; Gaiolla, R.; Galvez, K.; Remaggi, G.; Schutz, N.; Bittencourt, R.; Maiolino, A.; Quintero-Vega, G.; Cugliari, M.S.; Braga, W.M.T.; et al. Health care systems as determinants of outcomes in multiple myeloma: Final results from the Latin American MYLACRE study. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, G.E. Health care organization and delivery in Argentina: A case of fragmentation, inefficiency and inequality. Global Policy 2017, 8, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Hens, N.; Gusso, G.; Lagaert, S.; Macinko, J.; Willems, S. Dual use of public and private health care services in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, A.; Espinola, N.; Rojas-Roque, C. Need and inequality in the use of health care services in a fragmented and decentralized health system: Evidence for Argentina. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, A.; Zerbino, M.C.; Cejas, C.; López, A. Making universal health care effective in Argentina: A blueprint for reform. Health Syst. Reform. 2018, 4, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataife, G.; Courtemanche, C. Is Universal Health Care in Brazil Really Universal? Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1690662 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Giao Antunes, N.T.; Ribeiro, A.; Duval, A.; Moore, R. High-cost oncology drugs in Brazil and Mexico: Access differences between the public and private settings. Value Health 2017, 20, PA879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.; Efebera, Y.; Sharma, N. Role of stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Cancers 2021, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.; Pan, D.; Salinardi, T.; Rice, M.S. Real-world multiple myeloma front-line treatment and outcomes by transplant in the United States. EJHaem 2023, 4, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine-Pepeljugoski, C.; Braunstein, M.J. Management of newly diagnosed elderly multiple myeloma patients. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes Hungria, V.T.; Martínez-Baños, D.M.; Peñafiel, C.R.; Miguel, C.E.; Vela-Ojeda, J.; Remaggi, G.; Duarte, F.B.; Cao, C.; Cugliari, M.S.; Santos, T.; et al. Multiple myeloma treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in the Latin America Haemato-Oncology (HOLA) observational study, 2008–2016. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 188, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, M.P.; Oliveira, M.M.; Silva, D.R.M.; Souza, D.L.B. Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in 17 Latin American countries: An update. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungria, V.T.; Maiolino, A.; Martinez, G.; Duarte, G.O.; Bittencourt, R.; Peters, L.; Colleoni, G.; Oliveira, L.C.; Crusoé, E.; Coelho, E.O.; et al. Observational study of multiple myeloma in Latin America. Ann. Hematol. 2017, 96, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, T.; Martins, R.E.; Kashiura, D.; Saad, R. Real world data on multiple myeloma treatment patterns: First and second-line treatment in the Brazilian public health system. Value Health 2017, 20, A879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires. Acerca del Hospital. Available online: https://www.hospitalitaliano.org.ar/#!/home/hospital/seccion/20507 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Perles, D.C. Hospital Spotlight|Hospital Italiano: Carrying on with Its Expansion Plans. Available online: https://globalhealthintelligence.com/ghi-analysis/hospital-spotlight-hospital-italiano-carrying-on-with-its-expansion-plans/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Orizon. Defending the Health. Available online: https://www.orizonbrasil.com.br/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Ades, F. Access to oncology drugs in Brazil: Juggling innovation and sustainability in developing countries. Med. Access@ Point Care 2017, 1, maapoc-0000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Kumar, S. Multiple myeloma current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa de Magalhaes Filho, R.J.; Crusoe, E.; Riva, E.; Bujan, W.; Conte, G.; Navarro Cabrera, J.R.; Garcia, D.K.; Vega, G.Q.; Macias, J.; Oliveros Alvear, J.W.; et al. Analysis of availability and access of anti-myeloma drugs and impact on the management of multiple myeloma in Latin American countries. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019, 19, e43–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boytsov, N.; McGuiness, C.B.; Zhou, Z.; Huo, T.; Montgomery, K.; Kotowsky, N.; Chen, C.C. Multiple myeloma care, treatment patterns, and treatment durations in academic and community care settings. Future Oncol. 2025, 21, 1905–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.F.; Yee, C.W.; Gorsh, B.; Zichlin, M.L.; Paka, P.; Bhak, R.H.; Boytsov, N.; Khanal, A.; Noman, A.; DerSarkissian, M.; et al. Treatment patterns and overall survival of patients with double-class and triple-class refractory multiple myeloma: A US electronic health record database study. Leuk. Lymphoma 2023, 64, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.S.; Willson, J.L.; Opalinska, J.M.; Nelson, J.J.; Lunacsek, O.E.; Stafkey-Mailey, D.R.; Willey, J.P. Recent real-world treatment patterns and outcomes in US patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2020, 13, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crusoé, E.Q.; Pimenta, F.C.F.; Maiolino, A.; Castro, N.S.; Pei, H.; Trufelli, D.; Fernandez, M.; Herriot, L.B. Results of the daratumumab monotherapy early access treatment protocol in patients from Brazil with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2021, 43, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, F.; Zamagni, E.; Cole, C.E.; Scheid, C.; Hultcrantz, M.; Chorazy, J.; Iheanacho, I.; Pandey, A.; Bitetti, J.; Boytsov, N.; et al. Clinical outcomes associated with anti-CD38-based retreatment in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: A systematic literature review. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1550644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.-V.; Weisel, K.; De Stefano, V.; Goldschmidt, H.; Delforge, M.; Mohty, M.; Cavo, M.; Vij, R.; Lindsey-Hill, J.; Dytfeld, D.; et al. LocoMMotion: A prospective, non-interventional, multinational study of real-life current standards of care in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, K.; Delforge, M.; Driessen, C.; Fink, L.; Flinois, A.; Gonzalez-McQuire, S.; Safaei, R.; Karlin, L.; Mateos, M.V.; Raab, M.S.; et al. Multiple myeloma: Patient outcomes in real-world practice. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiolino, A.; Crusoé, E.Q.; Martinez, G.A.; Braga, W.M.T.; de Farias, D.L.C.; Bittencourt, R.I.; Neto, J.V.P.; Ribeiro, G.N.; Bernardo, W.M.; Tristao, L.; et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma treatment: Associação Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular Project guidelines: Associação Médica Brasileira—2022. Part I. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2022, 44, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, G.; Arbelbide, J.; Basquiera, A.L.; Belli, C.; Crisp, R.; Gonzalez, J.; Iastrebner, M.; Kohan, D.; Kornblihtt, L.; Lincango Yupanki, M.; et al. Neoplasias mielodisplásicas y neoplasias mielodisplásicas/mieloproliferativas. Available online: https://sah.org.ar/docs/guias/2023/Neoplasias_Mielodisplasicas_y_Neoplasias_Mielodisplasicas_Mieloproliferativas.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Jagannath, S.; Rifkin, R.M.; Gasparetto, C.; Toomey, K.; Durie, B.G.; Hardin, J.W.; Terebelo, H.R.; Wagner, L.I.; Narang, M.; Ailawadhi, S.; et al. Treatment (tx) journeys in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients (pts): Results from the Connect MM registry. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leleu, X.; Gorsh, B.; Bessou, A.; Paka, P.; De Nascimento, J.; Colin, X.; Landi, S.; Wang, P.F. Survival outcomes for patients with multiple myeloma in France: A retrospective cohort study using the Système National des Données de Santé national healthcare database. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 111, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadhi, S.; Jagannath, S.; Narang, M.; Rifkin, R.M.; Terebelo, H.R.; Toomey, K.; Durie, B.G.M.; Hardin, J.W.; Gasparetto, C.J.; Wagner, L.; et al. Connect MM registry as a national reference for United States multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, E.; Fe Bitaube, R.; Verdugo Cabeza De Vaca, V.; Gavira, R.; Garzón, S. How much has the overall survival of multiple myeloma patients improved after the incorporation of new drugs in the first line of treatment in real-world experience (RWE)? Blood 2024, 144, 6915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.