The Role of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Biology, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Opportunities

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 1.

- Published in English;

- 2.

- Conducted both in vitro for preclinical evidence and in human subjects for clinical trials;

- 3.

- Evaluated the role of HRD in solid tumors with a particular focus on RCC;

- 4.

- Clinical trials, cohort studies, comparative studies, or reviews specifically addressing the activity of drugs involved in the DNA repair system dedicated to, and performed with, a cohort of RCC patients.

- Articles that were not published in English;

- Focused on hematological diseases;

- Case reports/commentaries/editorials/opinion pieces without original data included;

- HRD variants of uncertain significance were excluded.

3. Results

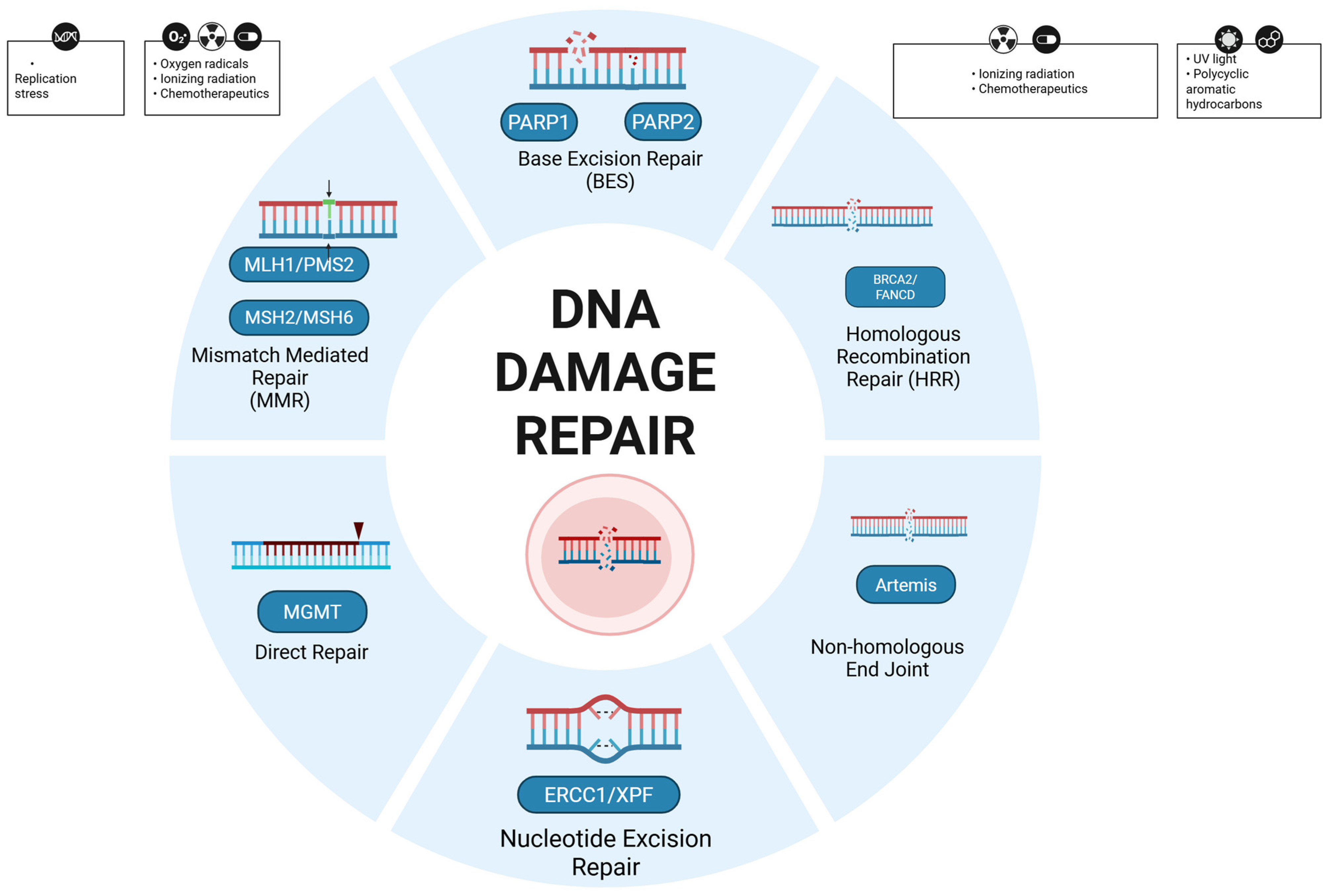

3.1. DNA Damage Response

3.2. BAP1 (BRCA1-Associated Protein 1)

3.3. RAD51

3.4. PBRM1

3.5. SETD2 (Homologous Recombination/Chromatin)

3.6. CHEK2

3.7. ATM

3.8. BRCA1 and BRCA2

3.9. PALB2

3.10. HRD Scores/Signatures in RCC

3.11. HRD Variants and Therapeutic Options

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ccRCC | Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| DDR | DNA damage repair |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| NHEJ | Non homologous End-joining |

| nccRCC | Non clear cell Renal Cell carcinoma |

| PARPi | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors |

| PDx | patient-derived xenograft |

| RCC | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| SSB | Single Strand Break |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F.; et al. Global Cancer Observatory; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alaghehbandan, R.; Siadat, F.; Trpkov, K. What’s new in the WHO 2022 classification of kidney tumours? Pathologica 2022, 115, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moch, H.; Amin, M.B.; Berney, D.M.; Compérat, E.M.; Gill, A.J.; Hartmann, A.; Menon, S.; Raspollini, M.R.; Rubin, M.A.; Srigley, J.R.; et al. The 2022 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosco, L.; Van Poppel, H.; Frea, B.; Gregoraci, G.; Joniau, S. Survival and impact of clinical prognostic factors in surgically treated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Ferguson, T.; Symeonides, S.N.; Hajek, J.; Chang, Y.H.; Lee, J.L.; Sarwar, N.; et al. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.K.W.; Siu, B.W.H.; Teoh, J.Y.C. Adjuvant treatment for renal cell carcinoma: Current status and future. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2025, 35, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, F.; Vavassori, I.; Rossitto, M.; Dottorini, L. Management of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Following First-Line Immune Checkpoint Therapy Failure: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Ławiński, J.; Franczyk, B.; Gluba-Sagr, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugman, M.; Jaime-Casas, S.; Zang, P.D.; Shah, K.; Nguyen, C.B. Immunotherapy in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2025, 129, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aweys, H.; Lewis, D.; Sheriff, M.; Rabbani, R.D.; Lapitan, P.; Sanchez, E.; Papadopoulos, V.; Ghose, A.; Boussios, S. Renal Cell Cancer—Insights in Drug Resistance Mechanisms. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 4781–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.; Lawson, K.; Prinos, P.; Finelli, A.; Arrowsmith, C.; Ailles, L. PBRM1, SETD2 and BAP1—The trinity of 3p in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2023, 20, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajewska, M.; Fehrmann, R.S.; de Vries, E.G.; van Vugt, M.A. Regulators of homologous recombination repair as novel targets for cancer treatment. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Ahn, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Park, Y.S.; Lim, H.Y.; Kang, W.K.; et al. The prevalence of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) in various solid tumors and the role of HRD as a single biomarker to immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 2427–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisman, Y.; Schejbel, L.; Schnack, T.H.; Høgdall, C.; Høgdall, E. Clinical Characteristics and Survival of Ovarian Cancer Patients According to Homologous Recombination Deficiency Status. Cancers 2025, 17, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yap, T.A.; Dhawan, S.D.; Hendifar, A.E.; Maio, M.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Quintela-Fandino, M.; Shapira, R.; Saraf, S.; Qiu, P.; Jin, F.; et al. A phase II study of olaparib in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with previously treated advanced solid tumors with homologous recombination repair mutation (HRRm) and/or homologous recombination repair deficiency (HRD): KEYLYNK-007. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, TPS3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalomeris, T.; Assaad, M.A.; la Mora, J.D.; Gundem, G.; Levine, M.F.; Boyraz, B.; Manohar, J.; Sigouros, M.; Medina-Martínez, J.S.; Sboner, A.; et al. Whole genome profiling of primary and metastatic adrenocortical carcinoma unravels significant molecular events. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 266, 155725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witz, A.; Dardare, J.; Betz, M.; Michel, C.; Husson, M.; Gilson, P.; Merlin, J.L.; Harlé, A. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) testing landscape: Clinical applications and technical validation for routine diagnostics. Biomark Res. 2025, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhmoud, J.F.; Woolley, J.F.; Al Moustafa, A.E.; Malki, M.I. DNA Damage/Repair Management in Cancers. Cancers 2020, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.L.; Mostoslavsky, R. DNA repair as a shared hallmark in cancer and ageing. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 3352–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzei, D.; Foiani, M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, H.M.; Mohammad, H.P.; Baylin, S.B. Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.P.; Bartek, J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 2009, 461, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczykowski, S.C. An overview of the molecular mechanisms of recombinational DNA repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a016410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannunzio, N.R.; Watanabe, G.; Lieber, M.R. Nonhomologous DNA end-joining for repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10512–10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Tho, L.M.; Xu, N.; Gillespie, D.A. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2010, 108, 73–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Sun, X.; Zhao, H.; Guan, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, P.K. Double-strand DNA break repair: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2023, 4, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. Therapeutic advances and application of PARP inhibitors in breast cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 57, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleday, T. The underlying mechanism for the PARP and BRCA synthetic lethality: Clearing up the misunderstandings. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.Y.; Khaleq, M.A.A.; Mohammed, R.Q. Comparative analysis of the roles of PBRM1 and SETD2 genes in the pathogenesis and progression of renal cell carcinoma: An analytical review. Wiadomości Lek. 2025, 78, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, F.; D’Andrea, V.; Buoso, A.; Cea, L.; Bernetti, C.; Beomonte Zobel, B.; Mallio, C.A. Advancements in Radiogenomics for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Understanding the Impact of BAP1 Mutation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsayed, A.M.; Kittaneh, M.; Cebulla, C.M.; Abdel-Rahman, M.H. An overview of BAP1 biological functions and current therapeutics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189267, Erratum in Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2025.189301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, P.; Rajaram, S.; Brugarolas, J. The expanding role of BAP1 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2023, 133, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turajlic, S.; Litchfield, K.; Rowan, A.; Horswell, S.; Chambers, T.; O’Brien, T.; Lopez, J.I.; Watkins, T.B.K.; Nicol, D.; Stares, M.; et al. Deterministic Evolutionary Trajectories Influence Primary Tumor Growth: TRACERx Renal. Cell 2018, 173, 595–610.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posada Calderon, L.; Dawidek, M.T.; Tang, C.; Kim, M.; Zong, G.; Bandlamudi, C.; Mehine, M.; Sheikh, R.; Kemel, Y.; Eismann, L.; et al. Defining the Histopathological, Clinical, and Genetic Characteristics of Familial BAP1-associated Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2025, 88, 630–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, P.; Pena-Llopis, S.; Christie, A.; Zhrebker, L.; Pavía-Jiménez, A.; Rathmell, W.K.; Xie, X.J.; Brugarolas, J. Effects on survival of BAP1 and PBRM1 mutations in clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, Y.C.; Moon, A.; Jung, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Bang, S.S.; Jang, K.; Paik, S.S.; Shin, S.J. Loss of Nuclear BAP1 Expression Is Associated with High WHO/ISUP Grade in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2018, 52, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joseph, R.W.; Kapur, P.; Serie, D.J.; Eckel-Passow, J.E.; Parasramka, M.; Ho, T.; Cheville, J.C.; Frenkel, E.; Rakheja, D.; Brugarolas, J. Loss of BAP1 protein expression is an independent marker of poor prognosis in patients with low-risk clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2014, 120, 1059–1067, Erratum in Cancer 2014, 120, 1752–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano Segura, R.N.; Hoang, M.P. BAP1 Tumor Predisposition Syndrome. Adv Anat Pathol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, M.N.; Schmidt, L.S.; Mester, J.L.; Pena-Llopis, S.; Pavia-Jimenez, A.; Christie, A.; Vocke, C.D.; Ricketts, C.J.; Peterson, J.; Middelton, L.; et al. A novel germline mutation in BAP1 predisposes to familial clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Gao, F.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Q.; Yang, M.; Huang, Y. Homologous recombination deficiency serves as a prognostic biomarker in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2023, 26, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Roberts, C.W.M. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ged, Y.M.; Rifkind, I.; Tony, L.; Daugherty, K.; Michalik, A.; Wang, H.; Carducci, M.; Markowski, M. ORCHID: A phase II study of olaparib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients harboring a BAP1 or other DNA repair gene mutations—Interim analysis. Oncologist 2023, 28 (Suppl. 1), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCT03786796: Study of Olaparib in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients with DNA Repair Gene Mutations. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03786796 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Cruz, C.; Castroviejo-Bermejo, M.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Ibrahim, Y.H.; Gris-Oliver, A.; Bonache, S.; Morancho, B.; Bruna, A.; Rueda, O.M.; et al. RAD51 foci as a functional biomarker of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitor resistance in germline BRCA-mutated breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijk, L.M.; Kramer, C.J.H.; Vermeulen, S.; Ter Haar, N.T.; de Jonge, M.M.; Kroep, J.R.; de Kroon, C.D.; Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Vrieling, H.; Bosse, T.; et al. The RAD51-FFPE Test; calibration of a functional homologous recombination deficiency test on diagnostic endometrial and ovarian tumor blocks. Cancers 2021, 13, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, H.; Jogo, T.; Kawazoe, T.; Kamori, T.; Nakaji, Y.; Zaitsu, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Baba, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Iwata, N. RAD51 Expression as a biomarker to predict efficacy of preoperative therapy and survival for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A large-cohort observational study (KSCC1307). Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castroviejo-Bermejo, M.; Cruz, C.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.; Ducy, M.; Ibrahim, Y.H.; Gris-Oliver, A.; Pellegrino, B.; Bruna, A.; Guzmán, M.; et al. A RAD51 assay feasible in routine tumor samples calls PARP inhibitor response beyond BRCA mutation. EMBO Mol Med. 2018, 10, e9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreira, S.; Porta, N.; Arce-Gallego, S.; Seed, G.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Bianchini, D.; Rescigno, P.; Paschalis, A.; Bertan, C.; Baker, C.; et al. Biomarkers associating with PARP inhibitor benefit in prostate cancer in the TOPARP-B trial. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2812–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonasch, E.; Walker, C.L.; Rathmell, W.K. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma ontogeny and mechanisms of lethality. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Liu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, S.; Guo, J.; Xu, J. Dual-loss of PBRM1 and RAD51 identifies hyper-sensitive subset patients to immunotherapy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2024, 73, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Li, X.; Zhan, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, J.; Bi, M.; Wang, Q.; Gu, X.; Xie, B.; Liu, T.; et al. PARP inhibitors suppress tumours via centrosome error-induced senescence independent of DNA damage response. eBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Varela, I.; Tarpey, P.; Raine, K.; Huang, D.; Ong, C.K.; Stephens, P.; Davies, H.; Jones, D.; Lin, M.L.; Teague, J.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature 2011, 469, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowski, R.; Muhl, S.M.; Sulser, T.; Krek, W.; Moch, H.; Schraml, P. Loss of PBRM1 expression is associated with renal cell carcinoma progression. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 132, E11–E17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, M.A.; Kouzarides, T.; Huntly, B.J. Targeting epigenetic readers in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.A.; Hou, Y.; Bakouny, Z.; Ficial, M.; Sant’ Angelo, M.; Forman, J.; Ross-Macdonald, P.; Berger, A.C.; Jegede, O.A.; Elagina, L.; et al. Interplay of somatic alterations and immune infiltration modulates response to PD-1 blockade in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenbabaoğlu, Y.; Gejman, R.S.; Winer, A.G.; Liu, M.; Van Allen, E.M.; de Velasco, G.; Miao, D.; Ostrovnaya, I.; Drill, E.; Luna, A.; et al. Tumor immune microenvironment characterization in clear cell renal cell carcinoma identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant messenger RNA signatures. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, D.F.; Huseni, M.A.; Atkins, M.B.; Motzer, R.J.; Rini, B.I.; Escudier, B.; Fong, L.; Joseph, R.W.; Pal, S.K.; Reeves, J.A.; et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, D.; Margolis, C.A.; Gao, W.; Voss, M.H.; Li, W.; Martini, D.J.; Norton, C.; Bossé, D.; Wankowicz, S.M.; Cullen, D.; et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science 2018, 359, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosellini, M.; Marchetti, A.; Mollica, V.; Rizzo, A.; Santoni, M.; Massari, F. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2023, 20, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, P.M.; Chambers, A.L.; Cloney, R.; Bianchi, A.; Downs, J.A. BAF180 promotes cohesion and prevents genome instability and aneuploidy. Cell Rep. 2014, 6, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.A.; Ishii, Y.; Walsh, A.M.; Van Allen, E.M.; Wu, C.J.; Shukla, S.A.; Choueiri, T.K. Clinical Validation of PBRM1 Alterations as a Marker of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response in Renal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1631–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Chen, D.; Wang, P.I.; Marker, M.; Redzematovic, A.; Chen, Y.B.; Selcuklu, S.D.; Weinhold, N.; Bouvier, N.; Huberman, K.H.; et al. Genomic Biomarkers of a Randomized Trial Comparing First-line Everolimus and Sunitinib in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Banchereau, R.; Hamidi, H.; Powles, T.; McDermott, D.; Atkins, M.B.; Escudier, B.; Liu, L.F.; Leng, N.; Abbas, A.R.; et al. Molecular subsets in renal cancer determine outcome to checkpoint and angiogenesis blockade. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 2013, 499, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Mao, G.; Tong, D.; Huang, J.; Gu, L.; Yang, W.; Li, G.M. The histone mark H3K36me3 regulates human DNA mismatch repair through its interaction with MutSα. Cell 2013, 153, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Ho, T.H.; Kapur, P.; Joseph, R.W.; Serie, D.J.; Eckel-Passow, J.E.; Tong, P.; Wang, J.; Castle, E.P.; Stanton, M.L.; Cheville, J.C.; et al. Loss of histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation is associated with an increased risk of renal cell carcinoma-specific death. Mod Pathol. 2016, 29, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.H.; Park, I.Y.; Zhao, H.; Tong, P.; Champion, M.D.; Yan, H.; Monzon, F.A.; Hoang, A.; Tamboli, P.; Parker, A.S.; et al. High-resolution profiling of histone H3 lysine 36 trimethylation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma reveals dynamic epigenomic changes associated with aggressive disease. Oncogene 2016, 35, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-D.; Zhang, Y.-T.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lam, T.; Hoang, A.; Hasanov, E.; Manyam, G.; Peterson, C.B.; Zhu, H.; et al. SETD2 loss and ATR inhibition synergize to promote cGAS signaling and immunotherapy response in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 4291–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sekino, Y.; Li, H.-T.; Fu, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, S.; Gujar, H.; Zu, X.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Gill, I.S.; et al. SETD2 deficiency confers sensitivity to dual inhibition of DNA methylation and PARP in kidney cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 3813–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Fang, C.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Weng, G. CHEK2 is a potential prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannini, L.; Delia, D.; Buscemi, G. CHK2 kinase in the DNA damage response and beyond. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 6, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolarova, L.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Soukupova, J.; Zemankova, P.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. CHEK2 Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition: Stalemate Rather than Checkmate. Cells 2020, 9, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huszno, J.; Kołosza, Z. Checkpoint Kinase 2 (CHEK2) Mutation in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Center Experience. J. Kidney Cancer VHL 2018, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Xue, B.; Chen, M.; Liu, L.; Zu, X. Low Expression of ATM Indicates a Poor Prognosis in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2019, 17, e433–e439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, P.; Rubarth, A.; Zodel, K.; Peighambari, A.; Neumann, F.; Federkiel, Y.; Huang, H.; Hoefflin, R.; Adlesic, M.; Witt, C.; et al. ATR represents a therapeutic vulnerability in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e156087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Tolcher, A.W.; Plummer, R.; Mukker, J.K.; Enderlin, M.; Hicking, C.; Grombacher, T.; Locatelli, G.; Szucs, Z.; Gounaris, I.; et al. First-in-Human Study of the Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-Related (ATR) Inhibitor Tuvusertib (M1774) as Monotherapy in Patients with Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2057–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiwi, S.A.; Nassar, A.; Adib, E.; Akl, E.; Groha, S.; Esplin, E.D.; Nielsen, S.; Yang, S.; McGregor, A.B.; Pomerantz, M.; et al. Prevalence of pathogenic germline risk variants (PVs) in 1829 renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients (pts). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Vogelzang, N.J. Biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma: Are we there yet? Asian J. Urol. 2021, 8, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heeke, A.L.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Lynce, F.; Xiu, J.; Brody, J.R.; Chen, W.J.; Baker, T.M.; Marshall, J.L.; Isaacs, C. Prevalence of Homologous Recombination-Related Gene Mutations Across Multiple Cancer Types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Złowocka-Perłowska, E.; Debniak, T.; Słojewski, M.; Lemiński, A.; Soczawa, M.; van de Wetering, T.; Trubicka, J.; Kluźniak, Z.; Wokolorczyk, D.; Cybulski, C.; et al. Recurrent PALB2 mutations and risk of bladder/kidney cancer—Polish series. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, K.A.; Rich, J.M.; Kumar, S.S.; Cen, H.; Duddalwar, V.A.; D’Souza, A. Comprehensive Systematic Review of Biomarkers in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Predictors, Prognostics, and Therapeutic Monitoring. Cancers 2023, 15, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telli, M.L.; Timms, K.M.; Reid, J.; Hennessy, B.; Mills, G.B.; Jensen, K.C.; Szallasi, Z.; Barry, W.T.; Winer, E.P.; Tung, N.M.; et al. Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score Predicts Response to Platinum-Containing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3764–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, H.; Glodzik, D.; Morganella, S.; Yates, L.R.; Staaf, J.; Zou, X.; Ramakrishna, M.; Martin, S.; Boyault, S.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulhan, D.C.; Lee, J.J.; Melloni, G.E.; Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Park, P.J. Detecting the mutational signature of homologous recombination deficiency in clinical samples via SigMA. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Prosz, A.; Sahgal, P.; Huffman, B.M.; Sztupinszki, Z.; Morris, C.X.; Chen, D.; Börcsök, J.; Diossy, M.; Tisza, V.; Spisak, S.; et al. Mutational signature-based identification of DNA repair deficient gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas for therapeutic targeting. npj Precis. Onc. 2024, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Han, Y.; Liu, X.; Xue, L.; Ji, Z.; Ye, H. High intratumoral heterogeneity in clear cell renal cell carcinoma is associated with reduced immune response and survival. Transl Androl Urol. 2025, 14, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sanromán, Á.; Fendler, A.; Tan, B.J.Y.; Cattin, A.L.; Spencer, C.; Thompson, R.; Au, L.; Lobon, I.; Pallikonda, H.A.; Martin, A.; et al. Tracking Nongenetic Evolution from Primary to Metastatic ccRCC: TRACERx Renal. Cancer Discov. 2025, OF1–OF23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijk, L.M.; Vermeulen, S.; Meijers, M.; van Diest, M.F.; Ter Haar, N.T.; de Jonge, M.M.; Solleveld-Westerink, N.; van Wezel, T.; van Gent, D.C.; Kroep, J.R.; et al. The RECAP Test Rapidly and Reliably Identifies Homologous Recombination-Deficient Ovarian Carcinomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijk, L.M.; Vermeulen, S.; Ter Haar, N.T.; Kramer, C.J.H.; Terlouw, D.; Vrieling, H.; Cohen, D.; Vreeswijk, M.P.G. Performance of a RAD51-based functional HRD test on paraffin-embedded breast cancer tissue. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023, 202, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Cheng, W.F.; Lin, P.H.; Chen, Y.L.; Huang, S.H.; Lei, K.H.; Chang, K.Y.; Ko, M.Y.; Chi, P. An activity-based functional test for identifying homologous recombination deficiency across cancer types. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano Gauna, D.E.; Duran, I.; Mellado, B.; Duran, M.A.C.; del Muro, X.G.; González, N.S.; Gordoa, T.A.; Sevillano, E.; Domenech, M.; Paramio, J.; et al. Phase I-II study of niraparib plus cabozantinib in patients with advanced urothelial/kidney cancer (NICARAGUA trial). Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, R.R.; Doshi, S.D.; Knezevic, A.; Chaim, J.; Chen, Y.; Jacobi, R.; Zucker, M.; Reznik, E.; McHugh, D.; Shah, N.J.; et al. A Phase 2 Trial of Talazoparib and Avelumab in Genomically Defined Metastatic Kidney Cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 7, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. A Phase 2 Study of Pamiparib (BGB-290) Plus Temozolomide for Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer (HLRCC) (Clinical Trial Registration No. NCT04603365). 2021. Available online: https://www.mycancergenome.org/content/clinical_trials/NCT04603365/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Ceralasertib (AZD6738) Alone and in Combination with Olaparib or Durvalumab in Patients with Solid Tumors NCT03682289. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03682289 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Maldonado, E.; Rathmell, W.K.; Shapiro, G.I.; Takebe, N.; Rodon, J.; Mahalingam, D.; Trikalinos, N.A.; Kalebasty, A.R.; Parikh, M.; Boerner, S.A.; et al. A Phase II Trial of the WEE1 Inhibitor Adavosertib in SETD2-Altered Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies (NCI 10170). Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Munster, P.; Mita, M.; Mahipal, A.; Nemunaitis, J.; Massard, C.; Mikkelsen, T.; Cruz, C.; Paz-Ares, L.; Hidalgo, M.; Rathkopf, D.; et al. First-In-Human Phase I Study Of A Dual mTOR Kinase And DNA-PK Inhibitor (CC-115) In Advanced Malignancy. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 10463–10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nguyen, L.; Martens, J.W.M.; Van Hoeck, A.; Cuppen, E. Pan-cancer landscape of homologous recombination deficiency. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, F.; Girotto, S. Structure-based approaches in synthetic lethality strategies. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2024, 88, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Harbour, J.W.; Brugarolas, J.; Bononi, A.; Pagano, I.; Dey, A.; Krausz, T.; Pass, H.I.; Yang, H.; Gaudino, G. Biological Mechanisms and Clinical Significance of BAP1 Mutations in Human Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1103–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okonska, A.; Buhler, S.; Rao, V.; Ronner, M.; Blijlevens, M.; van der Meulen-Muileman, I.H.; de Menezes, R.X.; Wipplinger, M.; Oehl, K.; Smit, E.F.; et al. Functional Genomic Screen in Mesothelioma Reveals that Loss of Function of BRCA1-Associated Protein 1 Induces Chemoresistance to Ribonucleotide Reductase Inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Qin, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Qin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, S.; Fan, X. DNA damage response alterations in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Clinical, molecular, and prognostic implications. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ged, Y.; Chaim, J.; Knezevic, A.; Knezevic, A.; Kotecha, R.R.; Carlo, M.I.; Lee, C.H.; Foster, A.; Feldman, D.R.; Teo, M.Y.; et al. DNA damage repair pathway alterations in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma and implications on systemic therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Habib, S.; Tantry, I.Q.; Islam, S. Addressing the Challenges of PD-1 Targeted Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2024, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabjerg, M. Identification and validation of novel prognostic markers in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Dan Med J. 2017, 64, B5339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scaglione, G.L.; Lombardo, V.; Polano, M.; Scandurra, G.; Pettinato, A.; Giunta, C.; Iemmolo, R.; Scollo, P.; Capoluongo, E.D. Real-World Analysis of HRD Assay Variability in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Impacts of BRCA1/2 Mutation Subtypes on HRD Assessment. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Medicine: Challenges Across Diagnostic Imaging, Clinical Decision Support, Surgery, Pathology, and Drug Discovery. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial | Phase | Population (Biomarker/Histology) | Treatment | Status/Key Read-Outs | NCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORCHID | II (single-arm) | mRCC with DDR mutations (e.g., BAP1, BRCA1/2, ATM, etc.) | Olaparib monotherapy | Recruiting with interim activity: responses seen, including in BAP1-mutated RCC; expansion ongoing. | NCT03786796 |

| NCT04068831 | II (single-arm) | mRCC, VHL-def ccRCC; FH/SDH-def RCC; renal medullary carcinoma | Talazoparib + Avelumab | Negative: no objective responses; median PFS 3.5 mo (cohort 1) and 1.2 mo (cohort 2); safety acceptable. | NCT04068831 |

| NICARAGUA | I/II | Advanced urothelial and RCC (mixed cohorts) | Niraparib + Cabozantinib | Phase I established dosing with preliminary activity; phase II emphasized urothelial cancer; RCC-specific efficacy not yet confirmed. | NCT03425201 |

| NCT04603365 | II | Hereditary leiomyomatosis and RCC (can present as mRCC) | Pamiparib + Temozolomide | Ongoing; evaluating response rate and PFS in FH-deficient RCC. | NCT04603365 |

| Target | Agent | Administration Modality | Study Design | Status/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATR | Ceralasertib (AZD6738) | Monotherapy; +durvalumab; +olaparib | Phase I/II solid tumor studies that include RCC cohorts/eligibility. | Ongoing/active; early signal mainly outside RCC so far. |

| WEE1 | Adavosertib (AZD1775) | Monotherapy in SETD2-altered tumors (incl. ccRCC) | Phase II: no ORR in SETD2-altered ccRCC; some durable DCR. | Negative for RCC as monotherapy; combinations under exploration. |

| DNA-PK | CC-115 (dual DNA-PK/mTOR inhibitor) | Monotherapy | Phase I safety in mixed solid tumors (not RCC-specific). | Investigational; no RCC efficacy data in patients. |

| DNA-PK | Peposertib (M3814) | With radiation/with ATR inhibitor (tuvusertib/M1774) | Ongoing early-phase combo trials in solid tumors. | Very early; no RCC clinical outcomes yet. |

| POLθ | Novobiocin | Monotherapy (DDR-altered cancers) | First-in-human phase I; histology-agnostic. | Dose-finding/biomarker-driven; efficacy unknown in RCC. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bongiovanni, A.; Conte, P.; Conteduca, V.; Landriscina, M.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Cognetti, F. The Role of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Biology, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120690

Bongiovanni A, Conte P, Conteduca V, Landriscina M, Di Lorenzo G, Cognetti F. The Role of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Biology, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Current Oncology. 2025; 32(12):690. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120690

Chicago/Turabian StyleBongiovanni, Alberto, Pierfranco Conte, Vincenza Conteduca, Matteo Landriscina, Giuseppe Di Lorenzo, and Francesco Cognetti. 2025. "The Role of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Biology, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Opportunities" Current Oncology 32, no. 12: 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120690

APA StyleBongiovanni, A., Conte, P., Conteduca, V., Landriscina, M., Di Lorenzo, G., & Cognetti, F. (2025). The Role of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) in Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC): Biology, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Current Oncology, 32(12), 690. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol32120690