Abstract

This is the summary of the 2023 SGHC Senning Lecture, in which surgical developments and the components of education and training in cardiovascular surgery are discussed. Special emphasis is placed on the problems, challenges, education models, and the dynamics of education and training for the benefit of the trainees and, ultimately, the patients.

1. Introduction

Guten Tag, meine Damen und Herren, liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen; Bonjour mesdames et messieurs, chers collègues; Buongiorno signore e signori, cari colleghi. It is a pleasure to be here today with you, in Basel, at the time of the Swiss Society of Cardiology (SSC)/Swiss Society for Heart and Thoracic Vascular Surgery (SGHC) Joint Annual Meeting 2023. I must thank the SGHC for the honour that has been bestowed upon me, delivering this very prestigious Senning Lecture, which is associated with the Honorary Membership of the SGHC. I will try my best to pass on to you the messages associated with the topic suggested to me for this occasion.

My disclosures are simple: my opinion is good but not the only one; my opinion is good, but not necessarily the best, and I have no moral conflicts of interest. I will discuss a variety of aspects of surgery, identifying them separately to facilitate their integration.

2. The Title

The title suggested by the President of the SGHC, Professor Peter Matt, is too long and too difficult for a lecture like this, regardless of the language we may use. However, I accepted straightaway for different reasons. First, if you accept such an invitation, it is appropriate to stick to the suggestions of the one inviting you. Second, it obliged me to be very strict in the definition of my objectives and my goals when facing this very select audience. I do not want to fail.

3. The Senning Lecture

The SGHC established the Senning Lecture to honour the memory of Professor Åke Senning (1915–2000), who, as you know, was the Director of Surgical Clinic A at the Kantonsspital Zürich (KSZ—currently Universitätsspital Zürich—USZ) between 1961 and 1985 (Figure 1). It is superfluous that I highlight the immense contributions of Professor Senning to the development of surgery, in general, and cardiothoracic surgery in particular. The 2022 SGHC Senning Lecturer, Professor Markus Heinemann, who is present here today, briefly went through them in one of his introductory slides entitled “Ars longa—Vita brevis” or “Art is long, life is short”. That is worth remembering.

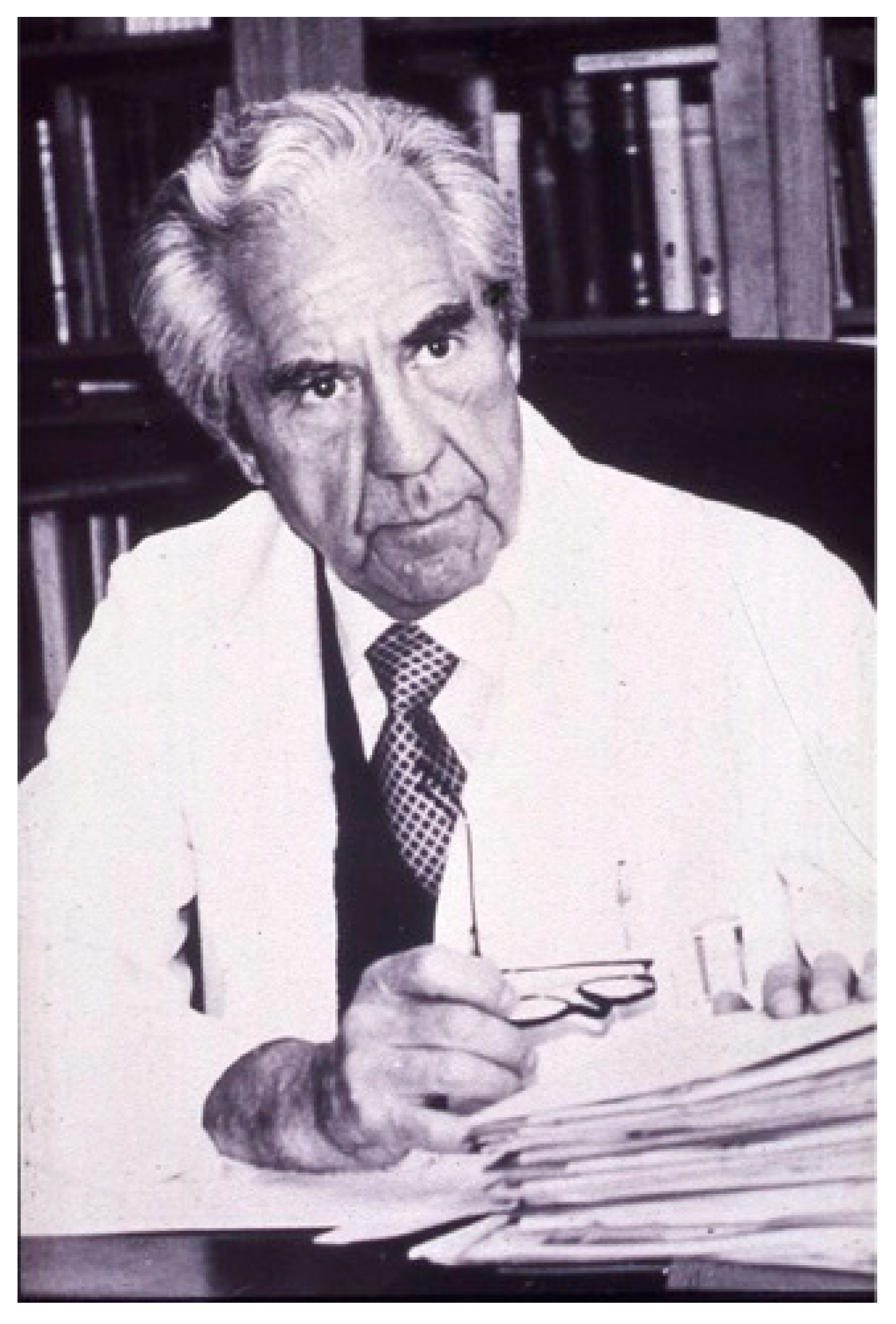

Figure 1.

Professor Åke Senning (Image courtesy of Prof. Marko I. Turina).

Among his numerous contributions, we will always remember him for his seminal and pioneering contribution to surgery for congenital heart defects, the atrial inversion technique for correction of transposition of the great arteries, published in 1959 [1]. This was an incredibly innovative procedure that still plays a role in the management of specific patients with very complex lesions today. His passing represented a major loss for the medical community, and his personality, surgical genius, and contributions were lovingly recognized worldwide [2,3,4,5].

4. Why Am I Here?

Having been invited to deliver this prestigious lecture, my question is, why am I here? I positively responded to the SGHC and flew over to Basel, but I do not know exactly why. I am not a famous local celebrity like Roger Federer, but the April 2023 SGHC newsletter stated that this lecturer addressing you was invited “…for his services in the education and training of young Swiss Cardiac Surgeons in the past years…” [6]. Then, I understood that perhaps there would have been something in my professional career resulting in some use to others, even if this may sound somewhat pretentious and presumptuous.

5. Switzerland

Why Switzerland? I was born in Barcelona, Spain, and graduated from the School of Medicine of the University of Barcelona (UB) in 1979. I practised at the Hospital Clinico, the teaching Hospital of the UB, for three decades until 2014, transitioning thereafter to the United Arab Emirates to join the staff at the Cleveland Clinic in Abu Dhabi when this new, beautiful facility opened. It was late in 2017 when I joined the Clinic for Cardiac Surgery at USZ at the invitation of Professor Francesco Maisano, who was leading at the time. My relationship with Switzerland is a long one, out of the professional affairs, as my mother’s younger brother married a former teacher at the Swiss School in Barcelona, originally from St. Gallen. They settled later in a small village close to the Austrian border, also in the Kanton St. Gallen. For years, I was a regular visitor, and I still have two younger cousins of mine living in the region. Thus, I was very familiar with the country by the time I joined the surgical staff at USZ. For obvious reasons, I knew well the cardiovascular surgery at USZ and had an excellent relationship with several colleagues.

On the other hand, due to my long-lasting involvement in the European Board of Cardiothoracic Surgery (EBCTS)—formerly the European Board of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgeons (EBTCS)—I had the opportunity to be an examiner for some Swiss surgeons during my 15-year tenure starting in 2005. Table 1 shows the names of those Swiss surgeons with whom I interacted at the EBCTS who later had prominent roles across the country. It was a privilege to interact at different levels with all of them over the past two decades. Some are attending this Lecture today, and I am very grateful that they took their time to join. It looks clearly that I developed a special bond with the country.

Table 1.

EBCTS Swiss examinees.

6. General Considerations

Before progressing on this presentation, I must say that Guest/Prize/Honorary lectures are dangerous for the presenter. There are several reasons to be careful when accepting them. First, these lectures have a very important load of responsibility, and the audience’s expectation is very high, especially when such an honour has been entrusted to a supposed-to-be stranger [7]. This means those attending expect a lot from the speaker!!! Second, consequently, the risk of failure is very high. And in some cases, it is a good way of telling you, “Listen, the door is there, and please close it when you leave.” I hope that the latter does not apply to me, at least today. As I said earlier, I do not want to fail.

7. Developments, Education, Training

7.1. Developments in Surgery

The term “development” has several meanings, such as “the process in which someone or something grows or changes and becomes more advanced”, “a recent event that is the latest in a series of related events”, or “the process of developing something new” [8]. This is all about medicine and surgery in particular. There have been numerous developments in the surgery of the chest, from the introduction of pleural and pericardial drainage and the treatment of tuberculosis to coronary and valve surgery, intrathoracic transplantation, or surgery of cardiac arrhythmias. If I must pick those most significant to me, I will opt for the developments in cardiopulmonary bypass and myocardial protection, surgery for congenital heart defects, coronary artery bypass surgery as part of therapy for vascular disease, and the care for advancement in surgical knowledge through surgical research, especially investigator-initiated research. While not everyone would agree with my picks, in my view, these represent milestones in the history of our specialty. A good example is surgery for congenital heart defects, pioneered by Professor Senning, offering excellent results: despite the risk of mortality in patients older than 18 years with congenital heart defects being thrice as high as that of the matched population, at least 75% of those alive at 18 will become sexagenarians [9]. All these developments and advances confirm that we are doing something good for our patients, the ultimate recipients of our communal knowledge and expertise.

7.2. Education in Cardiac Surgery

Education is “the process of teaching or learning, especially in a school or college, or the knowledge that you get from this”, and education is also “the study of methods and theories of teaching” [8]. Education entails the acquisition of information and knowledge, and we have a variety of ways, such as lectures, textbooks, publications, videos… The value of reading and gaining reading comprehension is of utmost importance in current times when all is left to the discretion of computer/device screens. Although devices and digital technology were supposed to assist in training and education, this has proven to be more than controversial, and reading comprehension is under threat today. It seems that some responsible people understand the advice from health professionals aiming to reduce excessive time in front of computer screens. Luckily, the Minister of Schools of Sweden chose to invest a million-dollar sum to bring back textbooks instead of computers in 2024 to avoid functional illiteracy of the adults-to-be [10]. This can be extrapolated to medical and surgical education. We must follow them, as the intellectual component in medicine and surgery is fading away.

Education in cardiac surgery, then, entails the acquisition of information and knowledge made possible through the implementation of solid programmes, meaning high-level organization; education cannot be left to the department alone and needs to be organized at the national level. On the other hand, professional education currently has some challenges which include but are not limited to chronicity, ageing, social demand and scrutiny, Dr. Google and lawsuits, to name a few [11,12].

7.2.1. The Problems—The Challenges

The evolution of society has an impact on every activity. In education, the design of a regionally or internationally reproducible training programme for cardiothoracic surgery remains a challenge [13]. The traditional apprentice model produced generations of competent surgeons, but this model is not completely suited for present-day programmes due to a multitude of factors. Modernization and standardization of training may be required to enhance different regional responses to these dynamic challenges in the field [13,14].

Our challenges include ethical considerations as there are growing demands from the public to challenge whether a surgeon-to-be has the right to train with someone specific of given relatives [15]. Patient outcomes, especially hard outcomes such as crude mortality, are an important part of the business today, as this may affect individual surgeons or institutions, as it happened in the past [15], or because this will lead institutions to enrol in “League” competitions with the known risks of gaming and statistical play [16]. The increasing complexity of procedures clearly poses increasing difficulties in teaching [17,18], and there are many differences among countries, systems, and specific training environments [19].

More problems are already out there, such as caseload requirements for certification because of the diversity of standards by country, assessment models, as there is no standardization, resource allocation, and lack of international conformity in training programmes, being Europe a good example of established differences among systems [20,21].

And there is even more to come. There are trainee-related factors such as prior training and trainee demographics [14,22]. There are trainer-related factors which have even stronger impact on the training process, including decreased incentive to teach, lack of educational training, public scrutiny of results, and, legitimate if you wish, that not everyone is willing to spend time teaching [23,24]. Finally, general issues affecting the profession include newer technologies, financial constraints, and political decisions such as the European Working Time Directive [25,26].

7.2.2. Education Models

All this suggests that we entered a new era in education. It looks like education in cardiac surgery will move into the integration of models with simulation and competency-based medical education without leaving behind the strong intellectual component of surgery [27,28].

7.3. Training

Again, as per sources, training is the process of learning the skills you need to do a particular job or activity [8]. Training is complex and related to skill acquisition, which has cognitive and psychomotor stages [29]. There are several components of training.

7.3.1. Deliberate Practice

This addresses the consistent, deliberate, and intense repetition of the same movement through continuous practice. Hence, this is the evidence for the so-called 10,000 h rule [30,31,32]. Nowadays, it promotes discussion about quality versus quantity in surgical training, too. The pathway to mastering surgery should combine practice routines and current complementary techniques in the study of the patient and the procedure to be undertaken [32].

7.3.2. Proficiency Versus Competency Training

Proficiency is the fact of having the skill and experience for doing something, and competency is an important skill that is needed to do a job [8]. These components entail seeking the minimum competency level to avoid error, which is what the EBCTS aims to assess, and establishing that all certified surgeons have this minimum competency at the time of training. The Dreyfus five-stage model of skill acquisition—novice, competence, proficiency, expertise, and mastery—helps in understanding the complexity of training and that of its goal [33].

Skill development includes psychomotor muscle memory and pattern recognition, the latter of which requires a long period of time. Other components of training are the development of specific metrics, mandatory feedback, and assessment of the entire process. The objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) [34] for surgical residents is an established and reliable method of assessing a diversity of surgical skills [13,14].

As said earlier, there are a few challenges in surgical training, such as the decrease in surgical volume, increasing case complexity, and public reporting. However, very likely one of the most dangerous is the heavy scrutiny of complications, which is uniquely rigorous in cardiac surgery. Training has a major burden of limitations and barriers that have an impact on the planning and implementation of programmes. This has been addressed by Carrel and Schoenhoff, who discussed the appropriate approach for training and the major pressure on training programmes [35]. Other authors have elaborated deeply into the subject by analyzing a diversity of non-cardiac and cardiac operations, looking at safety [22,36,37]. Specific policies, especially in overregulated regions such as the declining European Union, brought confusion and disarray to the institutional, departmental, and individual perception and realization of training [25,26]. And finally, surgery represents an unstable system in which all components and stakeholders respond to the pattern of chaos, as elegantly depicted by Heinemann [38].

Training is a dynamic process undergoing sequential changes over time. Some disrupting models are being proposed, considering that some interdisciplinary boundaries are nowadays blurred [39]. Simulation plays an increasing role as an adjunct to active programmes, not only in basic training but in retraining of established professionals. Interdisciplinary programmes will add value to training and education [13] as part of the team building process, the latter being a complex structure which includes forming, norming, storming, performing, and adjourning/briefing in a similar way as the aviation industry behaves [40], understanding the essential differences between it and surgical practice. All this goes around the major goals of training and education in cardiothoracic surgery, which are safety and outcomes, aiming at reaching the goal of certifying that our trainees will be better than the generation training them for the benefit of our patients. There are good examples of teamwork out there that underline the value of education and training to establish a mature practice pattern. I am very proud of several of these [41,42].

8. The Young

Young refers to having lived or existed for only a short time or to being at an early stage of development [8]. In other words, not old. Leadership and mentorship play a fundamental role in shaping the future personality of the trainee as a creative and smart individual and professional. The role of the mentor cannot be overemphasized; it holds value and has an impact on future practices and performances [43]. As the mentor is, as I just said, interested in the mentee’s career to progress, it is our responsibility to guide the younger generations across the complex and frequently gusty process of training to turn them into good professionals interested in delivering the best patient care. On the other hand, the mentees should not forget that they bear responsibility for responding to the support given in the form of pursuing an established plan and delivering through hard and dedicated work. The mentor–mentee relationship, when appropriately established and developed, will be rewarding for both parties, as was my case. From the late Dr. Gerald D. Buckberg, I learnt that leadership and mentorship are summarized under “Give credit and take the blame” [44] (Figure 2).

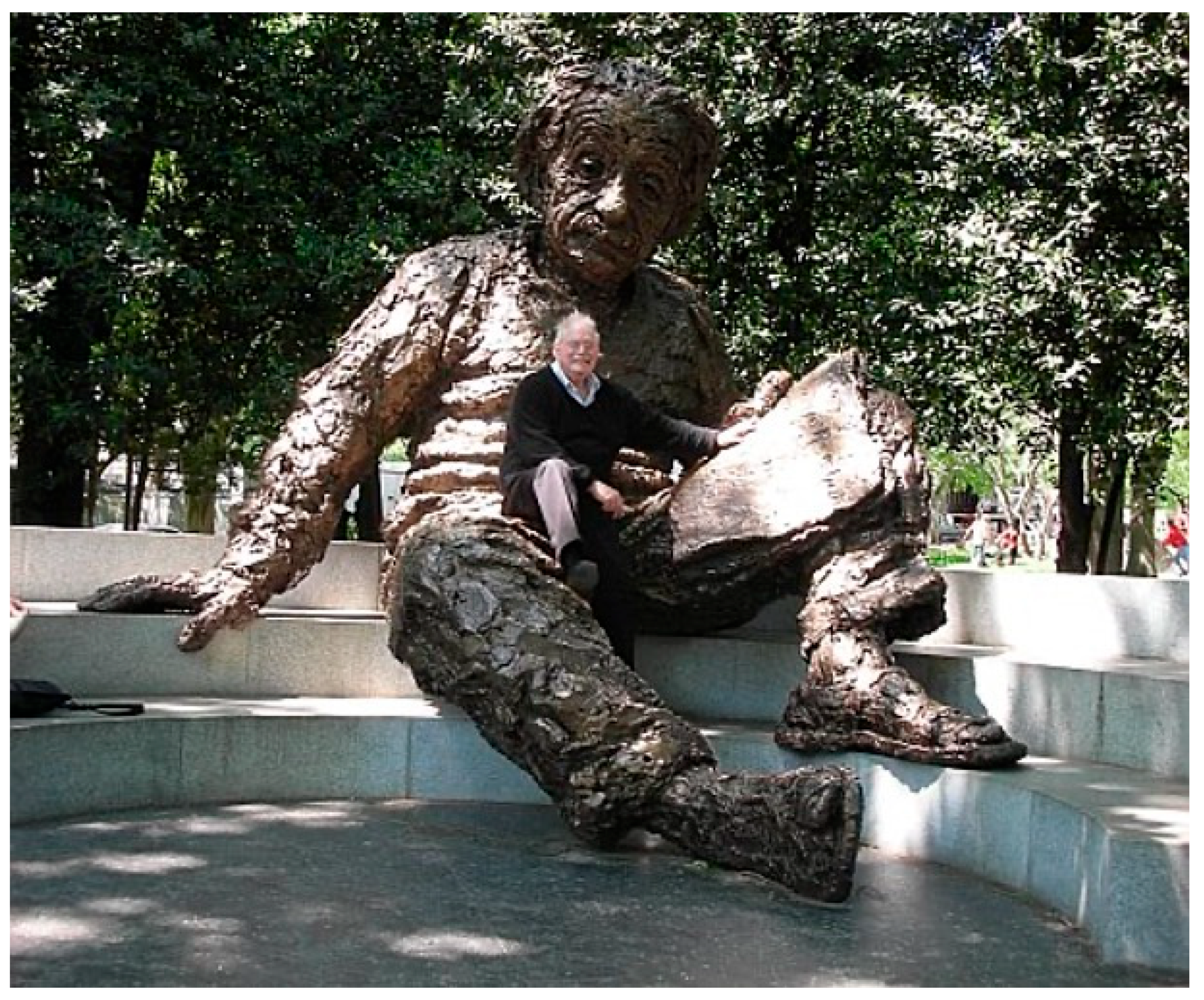

Figure 2.

The late Dr. Gerald D. Buckberg is sitting on the monumental bronze statue of Albert Einstein, located in central Washington, DC (USA), on the grounds of the National Academy of Sciences. To me, the epitome of the mentor–mentee relationship is the mentor supporting the mentee who grows towards professional and personal excellence (Image courtesy of the late Dr. Gerald D. Buckberg).

9. The Future

The future is a period that is to come [8]. This means that the future starts today. Our present, as society, seems dark and seems to forecast even less light as, for different reasons, we currently live with uncertainty and mortality, with global new controls and biosecurity regimes, massive state security protocols, frequent unbearable living adjustments with someone in full control of our personal lives which leaves us with the feeling, doubtful to me, of having privacy only at home and with the real need for guarantees to protect us from state abuse [45]. The future sounds even worse, with absolute control of the individual by the state, possible disappearance of cash, entering the world of implantable subcutaneous chips, and the loss of individual freedom.

In cardiovascular surgery, the changes observed in the past, the good, such as coronary surgery—the gold standard for triple-vessel and left main coronary artery disease—as well as mitral valve repair for degenerative disease, aortic surgery, surgery for infective endocarditis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, transplantation, and mechanical circulatory support, and many more, are established and routine therapies globally. The bad has been a steady and slow migration of cardiac pacing towards cardiology departments due to improvements and miniaturization of hardware and ease of implantation, among other factors. The ugly is a complex future scenario including, but not restricted to, new technologies, the changing profile of the cardiac patient, increasing complexity, educational differences, professional issues, and the booming of transcatheter therapies as recently highlighted by EACTS President De Paulis [46]. To add more to this multifaceted scenario, trends are towards radical and immediate incorporation of artificial intelligence in daily medical practice, aiming at improving diagnostic accuracy, process efficiency, and refining personalized care. However, there are also major concerns regarding the exact dangers posed by artificial intelligence, such as disinformation and loss of control, further leading to interference with brain activity [47,48].

10. Conclusions

The conclusion is the final part of something [8]. I shall then conclude this presentation by saying the following:

- 1.

- Education and training in surgery are a very complex process.

- 2.

- Committed teachers are a must—they should be givers.

- 3.

- Committed trainees must think wide, well beyond their access.

- 4.

- Current trends are towards competency-based training.

- 5.

- A combination of technical skills and a solid clinical background is required.

- 6.

- Critical thought above all.

In any case, the future of surgery is bright, and we should not forget that the frontier of cardiac surgery is, essentially, intellectual [49].

11. When You Go…

There is an old Spanish saying, “es de bien nacidos ser agradecidos”, that can be translated into “gratitude is the mark of a noble soul”. It is then my call of duty to express my gratitude to all those who made possible that I today stood up before you with the aim of transmitting to you, respected audience, some of my thoughts and feelings about the transfer of knowledge, limited in my case, and experience to those who will take over from us, as those of my generation did with those who preceded us. Therefore, my gratitude goes to the Board Members of the SGHC, personalizing on my dear colleagues and friends, the President, Professor Peter Matt, and Vice-President Professor Enrico Ferrari, once more, for thinking of me to join you for this prestigious Lecture. The SGHC Secretary, Professor Christoph Huber, together with Professor Piergiorgio Tozzi, was instrumental in favouring my participation in several specific teaching activities organized in the past few years. I am particularly proud of having participated in teaching and training for the SGHC. A part of this was harmoniously described in a recent publication that was thoroughly discussed by all of us, but especially with Professor Tozzi [50].

And, of course, I am particularly very grateful to the young members of the SGHC, to whom this Senning Lecture goes, with whom I had the opportunity and the pleasure, over the years, to work and to learn from. I would like to personally thank Drs. Hector Rodriguez, Devdas Inderbitzin, Mathias van Hemelrijck, Juri Sromicki, Alberto Pozzoli, Martin Schmiady, Vedran Savic, and Maurizio Taramasso for their support. It has been very rewarding discussing with them the problems arising in our daily practice, listening to their frequently wise opinions, and sharing with them the time spent in the operating room and seeing patients in the ward or the emergency room. My hope is that the time spent together has been useful in the development of their respective careers and, hopefully, personalities.

By saying this, I take the risk of inadvertently leaving others behind that may fall within this category of young—and not-so-young—surgeons and colleagues to whom I offer my sincere apologies, asking for forgiveness and understanding. And finally, it is my obligation to thank the one for his unconditional support and sound advice for more than thirty years, Professor Marko I. Turina.

I would like to thank you all for your presence and attention.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board approval, as it did not represent human research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data in this contribution are public. As a review article, data have been extracted from the available literature on this topic.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Senning, A. Surgical correction of transposition of the great vessels. Surgery 1959, 45, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Turina, M. Ake Senning (1915–2000). Cardiol. Young 2000, 11, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, D.A. In memoriam. Tribute to Ake Senning, pioneering cardiovascular surgeon. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2000, 27, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brunckhorst, C.; Candinas, R.; Furman, S. Ake Senning 1915–2000. Pace Clin. Electrophysiol. 2000, 11, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, C.B. Commentary: The genius of Ake Senning. JTCVS Tech. 2020, 4, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer Gesellschaft für Herz- und Thorakale Gefässchirurgie News. Available online: https://www.sghc.ch/news (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Virchow, R. The Huxley Lecture of recent advances in science and their bearing on Medicine and Surgery. South. Med. Rec. 1898, 28, 669–693. [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org (accessed on 16 March 2024).

- Dellborg, M.; Giang, K.W.; Eriksson, P.; Liden, H.; Fedchenko, M.; Ahnfelt, A.; Rosengren, A.; Mandalenakis, Z. Adults with congenital heart disease: Trends in event-free survival past middle age. Circulation 2023, 147, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hivert, A.F. Le Monde. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/health/article/2023/05/21/too-fast-too-soon-sweden-backs-away-from-screens-in-schools_6027454_14.html?search-type=classic&ise_click_rank=1 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Exworthy, M.; Gabe, J.; Jones, I.R.; Smith, G. Professional autonomy and surveillance: The case of public reporting in cardiac surgery. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, U.; Dimagli, A.; Gibbison, B.; Sinha, S.; Pufulete, M.; Fudulu, D.; Cocomello, L.; Bryan, A.J.; Ohri, S.; Caputo, M.; et al. Disparity in clinical outcomes after cardiac surgery between private and public (NHS) payers in England. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2020, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, F.E.; Jones, T.J.; Mestres, C.A.; Sadaba, J.R.; Pillay, J.; Yankah, C.; Pomar, J.L.; Turina, M.I. Integrated interdisciplinary simulation programmes: An essential addition to national and regional cardiothoracic surgical training and education programmes. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin-Cuartas, M.; Vervoort, D.; Contreras, J.R.; Garcia-Villarreal, O.; Escobar, A.; Ferrari, J.; Quintana, E.; Sadaba, R.; Mestres, C.A.; Carosella, V.C.; et al. Perspectives in Training and Professional Practice of Cardiac Surgery in Latin America. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, B.; Spiegelhalter, D.; Bailey, A.; Roxburgh, J.; Magee, P.; Hilton, C. The legacy of Bristol: Public disclosure of individual surgeons’ results. BMJ 2004, 329, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashef, S.A.; Roques, F. Risk assessment, league tables, and report cards: Where is true quality monitoring? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2002, 74, 1748–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolis, G., Jr.; Spencer, P.J.; Bloom, J.P.; Melnitchouk, S.; S’Alessndro, D.A.; Villavicencio, M.A.; Sundt, T.M., III. Teaching operative cardiac surgery in the era of increasing patient complexity: Can it still be done? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter Mehaffey, J.; Kron, I. General principles of teaching cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 164, e487–e490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.S.; Mestres, C.A. The safe surgeon. Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 27, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cerqueira, R.J.; Heuts, S.; Gollmann-Tepeköylü, C.; Syrjälä, S.O.; Keijzers, M.; Zientara, A. Challenges and satisfaction in Cardiothoracic Surgery Residency Programmes: Insights from a Europe-wide survey. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 32, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zientara, A.; Hussein, N.; Bond, C.; Jacob, K.A.; Naruka, V.; Doerr, F. Basic principles of cardiothoracic surgery training: A position paper by the European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Residents Committee. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 35, ivac213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolis, G., Jr. Training the next generation of cardiac surgeons: Is it time to redesign the case requirements? Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 36, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musselman, L.J.; MacRac, H.M.; Reznick, R.K.; Kingard, L.A. ‘You learn better under the gun’: Intimidation and harassment in surgical education. Med. Educ. 2005, 39, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Hopkins, L.; Robinson, D.; Brown, C.; Abdelrahman, T.; Egan, R.; Iorwerth, A.; Pollitt, J.; Lewis, W.G. Influence of trainer role, subspecialty and hospital status on consultant workplace-based assessment completion. J. Surg. Educ. 2019, 76, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, E.; Tsui, S. Registrars and Consultant Cardiac Surgeons of Papworth Hospital 2003–2005. Impact of the European Working Time Directive on exposure to operative cardiac surgical training. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2006, 30, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestres, C.A.; Revuelta, J.M.; Yankah, A.C. The European Working Time Directive: Quo vadis? A well-planned and organized assassination of surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2006, 30, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reznick, R.K.; MacRae, H. Teaching surgical skills—Changes in the wind. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2664–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaporciyan, A.A.; Yang, S.C.; Baker, C.J.; James, J.I.; Verrier, E.D. Cardiac surgery residency training: Past, present and future. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013, 146, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.A.; Ivry, R.B. The role of strategies in motor learning. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1251, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reider, B. Too Much? Too Soon? Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 1249–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krompe, R.T.; Tesch-Romer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearani, J.A.; Gold, M.; Leibovich, B.C.; Ericsson, K.A.; Khabbaz, K.R.; Foley, T.A.; Julsrud, P.R.; Matsumoto, J.M.; Daly, R.C. The role of imaging, deliberate practice, structure, and improvisation in approaching surgical perfection. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 154, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfus, S.E. The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2004, 24, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.A.; Regehr, G.; Reznick, R.; MacRae, H.; Murnaghan, J.; Hutchison, C.; Brown, M. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br. J. Surg. 1997, 84, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carrel, T.; Schoenhoff, F.S. Teaching Cardiac Surgery: A Major Contemporary Issue in the Academic Institutions. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2021, 69, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, J.; Göbölös, L.; Miskolczi, S.; Barlow, C. How safe is it to train residents to perform mitral valve surgery? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 23, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canal, C.; Scherer, J.; Birrer, D.L.; Vehling, M.J.; Turina, M.; Neuhaus, V. Appendectomy as Teaching Operation: No Compromise in Safety-An Audit of 17,106 Patients. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 78, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, M.K. Shaving with William. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 67, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, I.; Maisano, F.; Mestres, C.A. Mind the gap versus filling the gap. The heart beyond specialties. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 74, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crespigny, R. QF 32; MacMillan: Sydney, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mestres, C.A.; Paré, J.C.; Miró, J.M. Working Group on Infective Endocarditis of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. Organization and Functioning of a Multidisciplinary Team for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis: A 30-year Perspective (1985–2014). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2015, 68, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hemelrijck, M.; Schmid, A.; Breitenstein, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Bode, P.; Siemer, D.; Cuevas, O.A.; Greutmann, M.; Gruner, C.; Ruschitzka, F.; et al. Five years’ experience of the endocarditis team in a tertiary referral centre. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 25, w10142. [Google Scholar]

- Odell, D.D.; Edwards, M.; Fuller, S.; Loor, G.; Antonoff, M.B. Society of Thoracic Surgeons Workforce on Career Devlopment. The Art and Science of Mentorship in Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 113, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyersdorf, F.; Athanasuleas, C. 2007 American Association for Thoracic Surgery Scientific Achievement Award Recipient: Gerald D. Buckberg, MD, DSc. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 134, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brown, K. Manual for Survival. A Chernobyl Guide to the Future; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Paulis, R. EACTS News. Available online: https://www.eacts.org (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Metz, C. What exactly are the dangers posed by AI? The New York Times, 1 May 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/01/technology/ai-problems-danger-chatgpt.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Whang, O. AI is getting better at mind-reading. The New York Times, 1 May 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/01/science/ai-speech-language.html (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Mestres, C.A.; Pozzoli, A.; Taramasso, M.; Zuber, M.; Maisano, F. The frontier of cardiac surgery is intellectual. Vessel Plus 2019, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, P.; Ferrari, E.; Reuthebuch, O.; Matt, P.; Huber, C.; Eckstein, F.; Kirsch, M.; Mestres, C.A. Humanoids for teaching and training coronary artery bypass surgery to the nextgeneration of cardiac surgeons. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2022, 34, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.