Introduction

During the past two decades, the term “frailty” has become a vogue expression, with an exponentially growing use in the medical literature. This minireview first tries to establish a common understanding of the term “frailty”, then reviews the literature on hypertension in frail patients, and finally tries to formulate some recommendations for clinical practice.

What is frailty?

In people approaching the end of their life, we frequently observe a functional decline before death occurs. Very often this functional decline seemingly starts from healthiness, though of course in most of these persons some chronic comorbidities were preexisting for years or decades. In general, we may observe that physical fitness as well as walking distance decreases in these persons, and very often we may also observe weight loss and sarcopenia. With the progress of this process, sooner or later the person loses autonomy, becomes disabled and needs the support from other people. The term “frailty” in its original sense stands for the pathophysiological process leading to the observed functional decline. Fried et al. were the first to describe this process in detail [1].

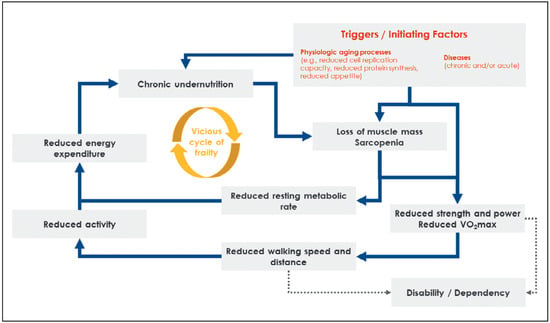

Figure 1 summarises the pathophysiology of the frailty process according to Fried et al. [1], which is a vicious circle if it is not interrupted. The cycle may be initiated by several factors. Usually, the inevitable physiological ageing processes, such as a reduced cell replication capacity or a reduced rate of protein synthesis caused by genetic changes with ageing (e.g., reduced telomere length), as well as chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease) initiate the cycle, but it may also be triggered by acute illness. Important initial steps are the loss of muscle mass and undernutrition. Undernutrition is facilitated by a physiological decrease in appetite with increasing age, but may also be the consequence of chronic disease and/or acute illness. The loss of muscle mass leads to reduced muscle strength and power, and a reduced VO2max. The loss of muscle mass also decreases the resting metabolic rate, which together with the reduced walking speed and distance will decrease total energy expenditure. The reduced energy expenditure further promotes chronic undernutrition and thereby closes the vicious cycle. If the cycle is not interrupted, disability, dependency and death are the consequence.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of the frailty process (adapted from reference [1]). The blue arrows show the causal relationships of the frailty process. The circled arrow symbolises the vicious cycle. The dotted arrows symbolise the probable exit to disability and dependency if the cycle is not interrupted.

How can we measure frailty appropriately? Given the pathophysiological concept, we can determine frailty accurately by measuring the phenotype, namely muscle strength, muscle mass, walking speed, energy expenditure, nutritional status and/or weight loss. Fried et al. proposed a frailty index based on these domains, which to date remains the most influential frailty index [1].

What is the current evidence on hypertension in frail patients in the literature?

As cardiovascular disease (chronic or acute) is an important trigger of frailty, and hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease, frailty has become part of hypertension studies.

Evidence from observational studies

Observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal cohort studies) first captured the topic. Recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis summarised current evidence on hypertension in frail patients from observational studies [2]. The authors concluded from the cross-sectional studies that hypertension was common in frail subjects (72% of frail subjects had hypertension), and that the prevalence of frailty among hypertensive individuals was 14%. These findings are plausible. The prevalence of both hypertension and frailty increase with age. Thus, it is evident that hypertension is frequently found in frail persons. Because hypertension starts much earlier in life than frailty, it is also obvious that the prevalence of frailty among hypertensive individuals is lower.

To date, one important research question remains open, namely whether or not hypertension is a causal factor of frailty. Only four longitudinal studies have investigated this topic and they showed conflicting results [2]. The largest of the four studies found, after adjustment for other factors, no association between systolic blood pressure and later frailty [3]. However, this study may be criticised because it was not done with the primary objective to investigate the association of hypertension with frailty, and that only systolic blood pressure from one measurement was available as independent variable (not a diagnosis of hypertension, and information as to whether or not the systolic blood pressure was treated or untreated). The conflicting results are plausible. Hypertension is a known risk factor of cardiovascular disease, which may initiate the frailty cycle. Thus, there is probably an indirect causal relationship between hypertension and frailty. Depending on the adjustment variables in regression modelling, results will show either a significant or nonsignificant association between hypertension and frailty.

Further research questions captured by observational studies concerned blood pressure levels among frail persons, and whether or not antihypertensive treatment might be beneficial for them. These studies uniformly found lower blood pressure among frail as compared with non-frail persons [4]. The most probable explanation for this phenomenon is that in the final years of life blood pressure levels are known to decrease, hence the finding of low blood pressure in frail persons is plausible [5]. Some recent observational studies also suggested that intensive blood pressure lowering in frail patients might increase their risk of falling or dying [6]. However, there is a considerable risk of confounding and bias inherent in these studies. So far, observational studies were unable to answer the question, whether or not lower blood pressure levels promote adverse events in frail persons (e.g., falls), and whether or not the lower blood pressure levels should give rise to a reduction in antihypertensive treatment.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials

The Hypertension in the Very Old Trial (HYVET) and the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) both showed that intensive blood pressure treatment is beneficial even in the oldest old [7,8]. However, these trials were criticised because the participants in both, even the oldest old, were presumably healthy, fit and non-frail, given the numerous exclusion criteria. Many experts feared that, according to the evidence from the observational studies, a low blood pressure might harm older frail patients. Subsequently, the authors of both trials published secondary analyses involving frailty status and found beneficial results even for the frail old trial participants [9,10]. However, these findings have to be interpreted with great caution. Given the numerous exclusion criteria, it is difficult to imagine that there were any truly frail patients in either trial. Thus, we have to ask how the authors of the HYVET or SPRINT trial found frail patients in their study populations. We have to study their way of defining frailty. Both trials used a multi-item frailty index; for example, the SPRINT trial used a 37-item index [10]. A close look at the single items used for the definition of frailty shows that only one of the 37 items (i.e., gait speed) can be considered as a good indicator of frailty, whereas all other items have little or nothing to do with it [10]. The relative weight of gait speed in the frailty index was 1/37, and it was available for only half of the study participants. Thus, it has to be concluded that the frailty index used in the HYVET and SPRINT trials did not necessarily measure frailty. This statement is supported by the publication of Pajewksi et al., who characterised frailty status in the SPRINT trial [11]. The authors found that participants aged 50 to 60 had nearly the same frailty index as participants aged 80 to 90 years. These results prove that the frailty index in the SPRINT trial measured something different from frailty. The question of what the frailty index measured arises. According to the single items used, the index measured mainly (cardiovascular) comorbidities [10]. However, comorbidities and frailty should not be mixed up. Comorbidities may trigger frailty (see Figure 1), but do not necessarily have to. There are many patients with a high comorbidity burden who are not frail. In the light of these considerations, it also becomes evident why the HYVET and SPRINT trials found beneficial results for “frail” participants, even a trend towards better results for the “frail” vs “non-frail” participants [9,10]. The “frail” participants were simply those with higher cardiovascular comorbidity, and thus those in whom antihypertensive treatment is particularly effective.

Conclusions on current evidence

Evidence on hypertension in frail patients remains sparse with seemingly conflicting results. The crucial point in all studies having investigated the associations between hypertension and frailty or the potential impact of antihypertensive treatment on outcomes and safety in frail patients is how frailty was defined. Most studies used inappropriate, yet misleading, definitions of frailty, in particular the randomised controlled trials [7,8,9,10]. Frailty definitions should be in accordance with the pathophysiological concept of frailty, because this corresponds best to what treating physicians regard as frailty. Most physicians will not treat patients according to the frailty definitions used in the trials, but according to what they subjectively regard as frailty. Thus, it is timely to include appropriately measured frailty definitions for the baseline characterisation of study populations and/or for the outcome assessment in research trials. In conclusion, important research questions remain unanswered, such as the effectiveness and safety of antihypertensive treatment in frail patients identified using appropriate frailty definitions, or the important question of whether rigorous antihypertensive treatment in earlier life may prevent frailty in later life.

What can be recommended for clinical practice?

Based on current evidence, the following recommendations may be formulated:

- The HYVET and SPRINT trials have shown that, for their participants, even the oldest old, antihypertensive treatment is beneficial for important outcomes – outcomes that are important even in the last years of life [7,8,9,10]. However, it is important to note that the older participants in these trials were relatively healthy, fit and non-frail. Thus, in such patients, rigorous antihypertensive treatment is an important therapeutic strategy to prevent cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As cardiovascular morbidity is a trigger of frailty and disability, it has to be presumed that rigorous antihypertensive treatment in these patients prevents frailty and disability, but evidence-based proof for this statement is pending.

- For patients who are already frail, evidence on antihypertensive treatment is sparse. Current recommendations for target blood pressure levels depend rather on remaining life span and on concomitant chronic diseases than on frailty per se [12]. Among geriatricians, it is widely accepted that tight blood pressure control <140/90 mm Hg is no longer recommended if the remaining life span is less than 1 to 2 years [13]. Frailty is a marker of a reduced remaining life span. To determine target blood pressure in frail patients, the remaining life span has to be estimated based on life-limiting diseases. In frail hypertensive patients with a markedly reduced life span, the target blood pressure goal may be gradually increased with a shorter life span. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule of thumb depending on concomitant chronic diseases. For example, patients with severe systolic heart failure need continuation of their heart failure medication, and low blood pressures are preferable in most of these patients even though their life span is markedly reduced, because discontinuation of the drugs could lead to an increase in the symptom burden.

- Current recommendations for target blood pressure levels in frail patients also depend on the tolerability of antihypertensive drugs [12]. If there is already relevant vascular disease, tight blood pressure control may lead to organ dysfunction distal to macroand/or microvascular stenoses. For example, in patients with vascular leukoencephalopathy, vertigo and/or cognitive dysfunction may be encountered with a too tight blood pressure control. As another example, patients with coronary artery disease may be prone to myocardial ischaemia and increased mortality if diastolic blood pressure is lower than 50–60 mm Hg [14]. Thus, a too tight blood pressure control in frail hypertensive patients with vascular disease may lead to critical organ hypoperfusion. Higher blood pressure goals have to be accepted in some of these patients.

- Orthostatic hypotension is frequently found among frail hypertensive patients with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy [15]. Thus, blood pressure should always be measured in both the sitting (or lying) and the standing position in frail patients. In general, blood pressure measurement is recommended in the sitting/lying position and then 1 and 3 minutes after standing up. If there is orthostatic hypotension (generally defined as drop of the systolic blood pressure ≥20 mm Hg and/or the diastolic blood pressure ≥10 mm Hg after standing up), the first step, besides support stockings and the instruction in the usual behavioural rules, is to do a polypharmacy check. Most frail patients are on several drugs, and many of these drugs may lead to orthostatic hypotension. Of course, all antihypertensive drugs may lead to orthostatic hypotension. However, before reducing the antihypertensive therapy, check for other drugs that may induce orthostatic hypotension, such as antidepressants, dopamine and its agonists, and opiates. Nearly all antidepressants may provoke orthostatic hypotension, but tricyclic and heterocyclic (i.e., trazodone) antidepressants and the monoamine oxidase inhibitors are the worst. In most instances, the antidepressant may be replaced by another. If orthostatic hypotension occurs with dopamine, domperidone may be tried 30 minutes before the intake of dopamine (domperidone is a peripheral dopamine antagonist that does not cross the blood-brain barrier). Among the antihypertensive drugs, alpha blockers are the worst; almost always they are easily replaceable. Remember that tamsulosin is an alpha-blocking drug, which can lead to orthostatic hypotension. Sometimes, it may be advisable to replace it with a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and orthostatic hypotension. Diuretics frequently induce orthostatic hypotension; therefore, they should be periodically adjusted, especially during summertime.

- Last but not least, frailty is considered to be a potentially reversible condition. Therefore, the treating physician should always evaluate whether the diseases that promoted frailty are treatable. For example, severe aortic stenosis may induce frailty; with aortic valve replacement, frailty may completely vanish [16]. If there is no treatable cause of frailty, the physician should always evaluate whether geriatric rehabilitation is indicated. The intensive physical training together with nutritional intervention, which are part of any geriatric rehabilitation, may reverse the vicious cycle of frailty and prevent its progression to disability and care dependency [17].

Key points

- Frailty is a pathophysiological vicious cycle based on chronic undernutrition and loss of muscle mass, leading to disability and care dependency if the cycle is not interrupted.

- There is practically no evidence on when and how to treat hypertension in frail patients. Further research is needed.

- Therefore, current recommendations for target blood pressure depend rather on tolerability of antihypertensive drugs, remaining life span and concomitant chronic diseases than on frailty per se.

Disclosure statement

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; et al. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.M.; Galluzzo, L.; Giampaoli, S.; Marengoni, A.; Bernabei, R.; et al. Joint Action ADVANTAGE WP4 group. Hypertension and frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e024406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, J.I.; Blaum, C.; Moore, T.; Xue, Q.L.; Hirsch, C.H.; Walston, J.D.; et al. Insulin resistance and inflammation as precursors of frailty: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007, 167, 635–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anker, D.; Santos-Eggimann, B.; Zwahlen, M.; Santschi, V.; Rodondi, N.; Wolfson, C.; et al. Blood pressure in relation to frailty in older adults: A population-based study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019, 21, 1895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindrarajah, R.; Hazra, N.C.; Hamada, S.; Charlton, J.; Jackson, S.H.; Dregan, A.; et al. Systolic Blood Pressure Trajectory, Frailty, and AllCause Mortality >80 Years of Age: Cohort Study Using Electronic Health Records. Circulation. 2017, 135, 2357–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Han, L.; Lee, D.S.; McAvay, G.J.; Peduzzi, P.; Gross, C.P.; et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014, 174, 588–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, N.S.; Peters, R.; Fletcher, A.E.; Staessen, J.A.; Liu, L.; Dumitrascu, D.; et al. HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358, 1887–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.T., Jr.; Williamson, J.D.; Whelton, P.K.; Snyder, J.K.; Sink, K.M.; Rocco, M.V.; Reboussin, D.M.; Rahman, M.; Oparil, S.; et al.; SPRINT Research Group A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373, 2103–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Warwick, J.; Falaschetti, E.; Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A.; Thijs, L.; Beckett, N.; et al. No evidence that frailty modifies the positive impact of antihypertensive treatment in very elderly people: an investigation of the impact of frailty upon treatment effect in the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antihypertensives in people with hypertension aged 80 and over. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.D.; Supiano, M.A.; Applegate, W.B.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Campbell, R.C.; Chertow, G.M.; et al. SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016, 315, 2673–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajewski, N.M.; Williamson, J.D.; Applegate, W.B.; Berlowitz, D.R.; Bolin, L.P.; Chertow, G.M.; et al. SPRINT Study Research Group. Characterizing Frailty Status in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016, 71, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; et al. Authors/Task Force Members. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018, 36, 1953–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onder, G.; Landi, F.; Fusco, D.; Corsonello, A.; Tosato, M.; Battaglia, M.; et al. Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults: results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging. 2014, 31, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denardo, S.J.; Gong, Y.; Nichols, W.W.; Messerli, F.H.; Bavry, A.A.; Cooper-Dehoff, R.M.; et al. Blood pressure and outcomes in very old hypertensive coronary artery disease patients: an INVEST substudy. Am J Med. 2010, 123, 719–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biaggioni, I. Orthostatic Hypotension in the Hypertensive Patient. Am J Hypertens. 2018, 31, 1255–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertschi, D.; Moser, A.; Stortecky, S.; Zwahlen, M.; Windecker, S.; Carrel, T.; et al. Evolution of Basic Activities of Daily Living Function in Older Patients One Year after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021, 69, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, S.; Finger, C.; Huss, A.; Egger, M.; Stuck, A.E.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c1718, Edifix has not found an issue number in the journal reference. Please check the volume/issue information. (Ref. 17 “Bachmann, Finger, Huss, Egger, Stuck, Clough-Gorr, et al., 2010”). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2021 by the author. Attribution Non-Commercial NoDerivatives 4.0.