Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of reactive extrusion (thermomechanical and chemical process) on the chemical composition, techno-functional properties, glucose and cholesterol adsorption capacity, and bioactive compound profile of spent coffee grounds (SCG). SCG was extruded using citric acid or alkaline hydrogen peroxide as reagents, and a control sample was extruded without reagents. Treatment with citric acid resulted in the highest levels of total dietary fiber (79.6 g/100 g) and insoluble fiber (76.2 g/100 g), especially cellulose, and significantly improved glucose (32.7 mmol/L) and cholesterol (4.5 mg/g) adsorption at neutral pH. Treatment with alkaline hydrogen peroxide increased water retention capacity (3.9 g/g). Although chemical treatments reduced total polyphenol and antioxidant activity, they effectively broke down the lignocellulosic matrix, thereby increasing fiber availability and functionality. Extrusion without reagents (processes induced by mechanical and thermal factors) favored the retention of caffeine and chlorogenic acids, increasing soluble fiber and maintaining antioxidant capacity. Therefore, reactive extrusion is a technological strategy that aligns with the principles of the circular economy, offering an environmentally friendly alternative to landfill disposal and adding value to spent coffee grounds by transforming lignocellulosic residue into functional ingredients with broad application potential.

1. Introduction

Coffee (Coffea spp.) is one of the most widely consumed beverages worldwide, with a strong cultural, economic, and social presence across regions. It is produced from the roasted seeds of species such as Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora, which are widely grown in tropical countries like Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia, and are among the world’s largest producers [1]. Daily coffee consumption worldwide exceeds 2 billion cups per day [2]. Data from Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Café—ABIC [3] show that between November 2023 and October 2024, there was a significant increase of 1.11% in the consumption of coffee-based beverages. The United States is the largest consumer of coffee, with 66% of Americans consuming the beverage, with 35% of coffee drinkers having their coffee prepared out-of-home, and 61% saying that they believe that coffee is good for their health, being aligned with new FDA (Food and Drug Administration) rule, which automatically qualified plain coffee to be labeled as healthy, for the first time [4].

The preparation of the beverage involves the extraction of soluble compounds with hot water, a process that generates a solid residue known as spent coffee grounds (SCG). In coffee shops and professional preparation establishments, where espresso machines are predominant, this residue is generated on a large scale and with high frequency [5]. According to Ahmed et al. [6], Starbucks alone generates about 91,000 tons of spent coffee grounds per year in the United States.

The increasing demand for coffee has led to several environmental concerns, primarily related to the improper disposal of SCG in landfills, which can produce methane and carbon dioxide, gases responsible for global warming. In addition, the high content of tannins, caffeine, chlorogenic acid, and phenols in SCG can lead to environmental pollution [7].

SCG have a rich and complex composition, including insoluble dietary fibers (cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin), proteins, lipids, and a variety of bioactive compounds such as chlorogenic acids, caffeine, melanoidins, and polyphenols [8,9]. Although disposal is the most common destination, the nutritional and technological characteristics of SCG make it a promising raw material for applications in the food, cosmetics, pharmaceutical, and biorefinery industries [10].

However, the efficient use of this residue faces barriers, including its high moisture content, the structural resistance of the lignocellulosic matrix, and the low bioavailability of functional compounds, which are trapped in the fibrous matrix [11]. These limitations underscore the necessity for technological pre-treatment and structural modification strategies, such as thermal, chemical, or physical processes, to facilitate the sustainable utilization of SCG in new value-added formulations.

Various approaches have been used to modify the structure of SCG and facilitate the extraction or use of its constituents. These include chemical treatments with oxidizing agents, such as alkaline hydrogen peroxide, which can oxidize lignin, break bonds, and solubilize hemicelluloses, thereby increasing the crystallinity of cellulose [12]. In addition, dilute acid treatments have been applied with a similar effect to decrease amorphous fractions and extract oligosaccharides from SCG [13].

At the same time, reactive extrusion is a continuous and combined chemical and thermo-mechanical process in a single step that is carried out under high temperatures, pressures, and shear, effectively breaking down the fibrous matrix of vegetable residue [14]. This technique promotes the breaking of covalent and non-covalent bonds, facilitating the release of bioactive compounds, modifying dietary fiber fractions (both soluble and insoluble), and enhancing techno-functional properties, such as water retention, swelling capacity, and the adsorption of glucose and cholesterol [15].

In this context, although previous studies have demonstrated the potential of different chemical and physical pretreatments in the structural alteration of raw material and lignocellulosic residues [12,13,14], there are still gaps in the integrated understanding of the combined effects between chemical agents and continuous thermomechanical processes, such as reactive extrusion. Thus, the use of reactive extrusion is a promising strategy for enhancing SCG properties, transforming it into a multifunctional ingredient with potential applications in fiber-enriched foods, nutraceuticals, or as pre-treatments in biorefineries.

Thus, this study aimed to investigate the effect of reactive extrusion in the presence of citric acid or alkaline hydrogen peroxide on the chemical composition, techno-functional properties, glucose and cholesterol adsorption capacity, and bioactive compound profile of spent coffee grounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

SCG (100% Arabica coffee with a light-medium roast degree) from an espresso coffee shop in Londrina (Paraná, Brazil) was dried for 12 h at 45 °C in an air-circulating oven (Marconi MA 035, São Paulo, Brazil) until constant weight.

2.2. Reactive Extrusion

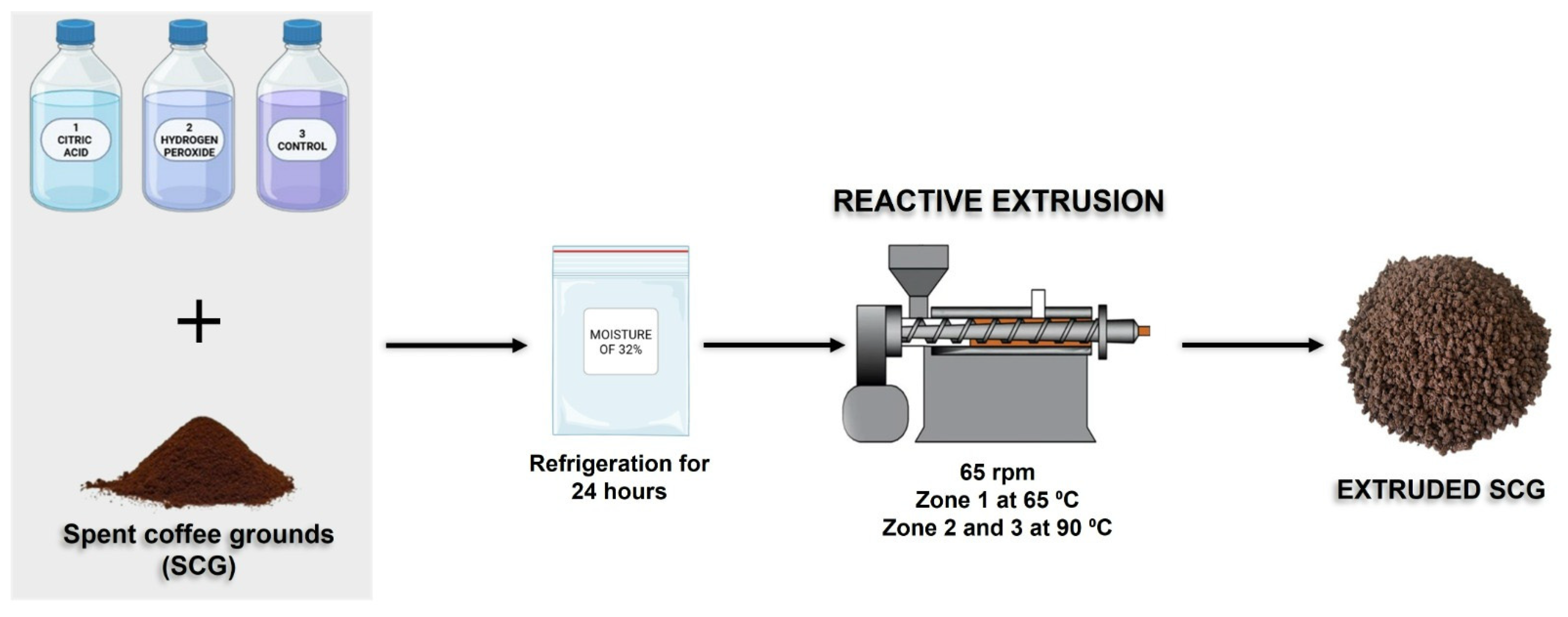

Reactive extrusion was conducted according to the methodology described by Debiagi et al. [14], with some modifications. Initially, the SCG was prepared with different chemical reagents, citric acid (CA) and alkaline hydrogen peroxide (AHP), dissolved in water, following previously defined conditions, in preliminary tests not presented, and adjusted to a moisture of 32%. The treatments applied were (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the reactive extrusion process with SCG and different reagents.

- Acid medium: 5% (m/m) citric acid (SCG-CA);

- Alkaline medium: 2% (m/m) alkaline hydrogen peroxide, pH 11.5 (SCG-AHP);

- Control sample: without reagents, with moisture adjusted to 32% (SCG-Control).

The SCG samples, mixed with reagents or water, were placed in sealed plastic bags and refrigerated for 24 h to ensure homogenization and achieve the desired moisture content before processing.

The reactive extrusion process was carried out in a single screw extruder (AX Plásticos, São Paulo, Brazil), equipped with a 1.6 cm diameter screw and a length to diameter ratio (L/D) of 40. The operating conditions included a speed of 65 rpm, three heating zones (zone 1 at 60 °C; zones 2 and 3 at 90 °C), and a cylindrical die with a diameter of 0.8 cm.

After extrusion, the chemically treated samples were washed with running water until the pH reached neutrality, then dried in an air-circulating oven (Marconi MA 035, São Paulo, Brazil) at 45 °C for 12 h until constant weight.

2.3. Chemical Characterization of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP and SCG-Control

2.3.1. Chemical Composition

The analyses of moisture, ash, lipids, proteins, total dietary fiber, insoluble dietary fiber, and soluble dietary fiber were performed according to the methodologies described by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists-AOAC [16].

2.3.2. Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin

Cellulose and hemicellulose content were quantified according to Van Soest [17], and insoluble lignin using the Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry-TAPPI test method [18].

2.4. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR analysis was performed using an IR PRESTIGE-21 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Dried samples were mixed with potassium bromide and compressed into tablets, and 64 scans were recorded with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 and a spectral range of 4000–400 cm−1. The spectra were not baseline corrected.

2.5. Techno-Functional Properties of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

2.5.1. Water Holding (WHC) and Oil Holding Capacity (OHC)

For the determination of WHC and OHC, 1.0 g of sample was used, and 30 mL of distilled water (WHC) or soybean oil (OHC) was added. Each sample was vortexed for 1 min (MA 140 CFT, São Paulo, Brazil) and then left to stand for 24 h. The suspensions obtained were centrifuged (5804 R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 20 min at 3000× g, and then the supernatant was discarded, and the solid fraction was weighed. WHC was expressed in g H2O/g, and OHC was expressed in g oil/g [19].

2.5.2. Swelling Capacity (SC)

The SC determination was performed using 250 mg of sample, mixed with 5 mL of distilled water and shaken in a shaker (MA 140 CFT, São Paulo, Brazil) for 30 min and left to stand for 20 h. The SC (mL/g) was calculated from the volume (mL) occupied by the sample divided by the sample mass (g) [20].

2.6. Cholesterol (CAC) and Glucose (GAC) Adsorption Capacities of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP and SCG-Control

The CAC was quantified and calculated according to the method described by Jia et al. [21] with some modifications. Fresh egg yolk was diluted (1:9) in distilled water, obtaining ± 25 mL of solution. Then, the sample (1.0 g) was added, and the pH was adjusted to 2.0 and 7.0. Subsequently, the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After homogenization and centrifugation (5804 R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 3500× g for 10 min, CAC was determined using the GOD-PAP triglyceride enzyme kit (Ref. 1770290, Laborlab S.A., Guarulhos, Brazil) for each pH condition. CAC was calculated according to Equation (1), and the result was expressed in mg/g:

where TGi are the initial triglycerides present in the sample without incubation, TGaf is the triglycerides of the final absorption in the sample after incubation, and M is the mass of the sample.

GAC was determined using 1.0 g of sample for 100 mL of glucose solution at different concentrations (50 and 100 mmol/L). The suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 6 h and then centrifuged (5804 R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 15 min at 3500× g [22]. The supernatant was collected to quantify the adsorbed glucose by the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS), and the result was expressed in mmol/L.

2.7. Bioactive Compounds in Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

2.7.1. Extract Preparation

For the determination of the total polyphenol content, melanoidins, antioxidant activity, caffeine and total chlorogenic acids (CGA) an extract with 0.5 g of sample and 30 mL of ultra pure water at 80 °C was prepared by 10 min by 10 min, followed by centrifugation (5804 R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) at 1000× g for 10 min [23]. The supernatant was collected and later filtered through a nylon syringe filter 0.22 μm (Filtrile, Colombo, Brazil) to perform subsequent analyses.

2.7.2. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

TCP was determined using the Folin and Ciocalteu spectrophotometric method [24]. 5-point analytical curves were performed in triplicate measurements with a known concentration of gallic acid (5–50 μmol/L), and absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer (765 nm) (Spectrophotometer SL244, Elico, Hyderabad, India). The TPC was expressed in mg equivalent to gallic acid (GAE) by 100 g sample (mg GAE/100 g).

2.7.3. Antioxidant Properties—Free Radical Scavenging Activity DPPH and ABTS

The determination of the free radical scavenging activity by the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) method was carried out according to Blois et al. [25] and Dinis et al. [26]. The reduction in the free radical was determined by spectrophotometry (SL244 spectrophotometer, Elico, Hyderabad, India) at 517 nm. The antioxidant capacity of the samples was determined using a Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) analytical curve (2–5 mmol/L), and the result was expressed as mg Trolox equivalent/100 g of sample (mg TE/100 g).

The antioxidant radical sequestering capacity by the ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) method was carried out according to Re et al. [27]. The calibration curve was made with a standard Trolox solution (1–8 mmol/L), read in a spectrophotometer at 730 nm (SL244 spectrophotometer, Elico, Hyderabad, India). The result was expressed as mg Trolox equivalent per 100 g of sample (mg TE/100 g).

2.7.4. Melanoidins (ME)

ME estimation was carried out according to Mori et al. [28] with modifications. Diluted extracts (4–10 mg/mL) were read in a spectrophotometer (SL244 spectrophotometer, Elico, Hyderabad, India) at a wavelength of 420 nm. ME content was estimated based on the absorptivity value of 1.1289 L/g.cm proposed by Tagliazucchi et al. [29]. The results were expressed as mg ME/100 g.

2.7.5. Caffeine and Total Chlorogenic Acids (CGA)

The simultaneous determination of caffeine and chlorogenic acids was performed according to Viencz et al. [30] in an ultra-performance liquid chromatograph (Water acquity, Waters, Milford, CT, USA). The SCG extract was diluted with water (1:2 v/v or 1:5 v/v) and filtered. A column to Spheritorb Ods-1 (150 × 3.2 I.D., 3 μm) (Waters, Milford, CT, USA) was used, the mobile phase consisted of acetic acid: water (5:95 v/v) (A) and acetonitrile (B), with gradient elual: 0–5 min 5% B, 6 min 13% B and 25 min 13% B, with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, 10 µL injection volume and 27 min running time. The detection was fixed at 272 nm for caffeine and 320 nm for chlorogenic acids. The analysis was performed in triplicate. Identification was based on retention times and UV spectra. The quantification was performed using a standard 6-point curve (10–60 µg/mL for caffeine and 1–60 µg/mL to 5-CQA). The total content of chlorogenic acids (CGA) was estimated by the sum of composite areas detected at 320 nm. The result was expressed in mg/100 g sample.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation. Data were statistically analyzed using ANOVA, and for mean comparison, Tukey’s tests were employed with a significance level of 5% (p ≤ 0.05). All analyses were performed using R software 4.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with experiments conducted in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

The characterization of the chemical composition of the raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control is shown in Table 1, and the main component of all samples was the total dietary fiber (ranging from 65.5 to 79.6 g/100 g).

Table 1.

Characterization of the chemical composition of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control.

Raw SCG had a high insoluble fiber content (64.1 g/100 g), primarily composed of cellulose (14.1 g/100 g), hemicellulose (23.0 g/100 g), and lignin (36.0 g/100 g) (Table 1). After extrusion, all samples were affected in their composition (Table 1)

SCG-CA, treated with citric acid, had the highest levels of total fiber (79.6 g/100 g), cellulose (27.4 g/100 g), and lipids (11.4 g/100 g) (Table 1). On the other hand, SCG-AHP, treated with AHP, was characterized by a high content of proteins (8.0 g/100 g), total dietary fiber (77.0 g/100 g), and lignin (54.4 g/100 g) (Table 1). Both treatments were effective in modifying the fibrous structure of SCG.

The raw SCG sample had an ash content of 1.9 g/100 g (Table 1), a value consistent with those reported in the literature, which ranged from 1.3 to 2.7 g/100 g [9,10,31] but was lower than values reported by Atabani et al. [32], who reported ash contents ranging from 4.5 to 6.3 g/100 g for SCG samples. Considering the ash content, a statistically significant difference is observed between the samples (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). Samples treated with chemical reagents exhibited the lowest ash contents, suggesting partial removal of mineral components during the post-extrusion washing stage. Guo et al. [33] observed no significant changes in the ash content of garlic peel after processing by twin-screw extrusion, without the use of reagents, conducted at 25% moisture, 170 °C, and 170 rpm.

The lipid content was not affected by treatments (Table 1). Iriondo-DeHond et al. [10] reported lower lipid contents for SCG samples than those observed in this study, ranging from 1.6 to 2.3 g/100 g. However, other authors, such as Campos-Vega et al. [8], Jímenez-Zamora et al. [34], and Atabani et al. [32], have described values that can vary widely, between 10.0 and 29.0 g/100 g.

Guo et al. [33] did not identify statistically significant differences in the lipid content of garlic peel subjected to the extrusion process without reagents. In contrast, Andirigu et al. [35] reported significant increases in lipid content in mixtures composed of white sorghum, millet, and beans extruded at 180 °C, without the use of reagents, with variations between 17.5% and 38.7%, depending on the formulation. Similarly, Yoshida et al. [36] observed significant increases in the lipid content of okara extruded in a single-screw extruder (120 °C and 115 rpm), with moisture contents of 30%, 35%, and 40%, without the presence of reagents, indicating that the behavior of lipids during the extrusion process can be influenced both by the composition of the food matrix and by the operating parameters employed.

The protein content in the raw SCG sample was 1.2 g/100 g (Table 1). According to the literature, the protein content in SCG can vary from 10.3 to 17.4 g/100 g [8,10,31,32,34] values higher than those obtained in this study, possibly due to differences in processing conditions, the origin of the residue, or the analytical method used.

After the extrusion treatment, a statistically significant increase was observed in protein contents for all samples (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05), with increases of 500% for SCG-Control (7.2 g/100 g), 491.6% for SCG-CA (7.1 g/100 g), and 567% for SCG-AHP (8.0 g/100 g) (Table 1). This significant increase may be related to the relative concentration of proteins resulting from the removal of other fractions (such as hemicellulose and ash; Table 1), as well as the increase in availability of previously insolubilized proteins or nitrogen compounds [37].

Table 1 shows that total dietary fiber increased significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) after extrusion compared with the raw SCG sample. The total fiber content was substantially higher in the extruded samples, with SCG-CA (79.6 g/100 g) standing out with an increase of 21.5%, followed by SCG-AHP (77.0 g/100 g) and SCG-Control (73.5 g/100 g) compared to 65.5 g/100 g in the raw sample. This increase can be attributed to the removal of non-fibrous fractions and the improved availability of dietary fiber resulting from extrusion processing.

Compared to raw SCG, which had 64.1 g/100 g of insoluble fibers, all the extrusion conditions increased this component, especially the citric acid treatment (SCG-CA), which had the highest content (76.2 g/100 g), followed by the AHP treatment (SCG-AHP) with 73.5 g/100 g, and the control sample (SCG-Control), which reached 68.7 g/100 g. These results indicate that the reactive extrusion conditions employed in this study effectively preserved the insoluble fraction, particularly cellulose and lignin. In contrast, hemicellulose content decreased across all treatments, indicating the susceptibility of hemicelluloses to thermal and/or chemical degradation [38,39].

The soluble fiber content increased when SCG were subjected to all treatments, suggesting that the thermal and mechanical process (pressure and shear force) of extrusion favored the partial breaking of glycosidic bonds of insoluble polysaccharides and converted them into soluble compounds of lower molecular weight [40,41,42]. These results demonstrate that extrusion, whether applied alone or in combination with chemical treatments, is effective in recovering the fibrous fraction of SCG, with potential for use in dietary fiber–enriched food formulations.

The chemical reactions resulting from the extrusion process, such as the breakdown of polymeric compounds, are highly dependent on the composition of the food matrix and the extrusion parameters [43].

According to Gil Giraldo et al. [38], extrusion, together with the action of citric acid in lignocellulosic matrices, promotes the partial solubilization of hemicelluloses and the breakdown of more sensitive ester and ether bonds, introducing carboxyl groups that alter surface polarity and negative charge density. Together, these effects can result in greater porosity, more irregular surfaces, and increased matrix reactivity.

The combination of AHP with extrusion profoundly modifies the structure and composition of the lignocellulosic matrix, as the peroxide generates oxidizing species (mainly the hydroperoxide anion HOO−, in addition to radicals •OH and O2−), which attack and fragment lignin and promote the solubilization of hemicelluloses [39]. As a result, the residual fraction becomes richer in cellulose, with lower lignin and hemicellulose content, which often increases the relative crystallinity of cellulose and exposes a more accessible and porous surface [44].

According to Konan et al. [45], during extrusion, high shear, pressure, and temperature alter and weaken the covalent and hydrogen bonds of the lignocellulosic matrix, reducing the degree of cellulose polymerization and decreasing part of the hemicellulose and lignin layer, increasing structural disorganization. Zhong et al. [46] report that screw speed, moisture, and temperature are the most significant extrusion factors affecting the conversion of insoluble to soluble fibers. Table 2 describes different studies on the influence of extrusion conditions on the properties of dietary fibers in agro-industrial residues.

Table 2.

Extrusion conditions and effects on total, soluble and insoluble fiber content.

Table 2.

Extrusion conditions and effects on total, soluble and insoluble fiber content.

| Residue | Optimal Extrusion Conditions | Effect of Extrusion Compared to the Non-Extruded Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee parchment flour | T: 160–175 °C; Ss: NR; M: 25%; Re: NR | IF: an increase of 9%, from 77.2 to 84.3 g/100 g. | Benítez et al. [47] |

| Soybean residue | T: 115 °C; Ss: 180 rpm; M: 31%; Re: NR | There was no change in TF content. IF: 17.1% decrease. SF: increase from 2.05 to 12.65 g/100 g | Jing et al. [48] |

| Garlic Skin | T: 170 °C; Ss: 170 rpm; M: 25%; Re: NR | 20.8% decrease in TF content compared to the control sample. IF: decrease from 72.01 to 45.29 g/100 g. SF: increase from 5.31 to 15.87 g/100 g. | Guo et al. [33] |

| Okara | T: 120 °C; Ss: 115 rpm; M: 30, 35 and 40%; Re: NR | There was no statistical difference in the IF content (result close to 50.27 g/100 g). An average increase of 70% in SF. | Yoshida et al. [36] |

| Lupin seed coat | T: 140 °C; Ss: 400 rpm; M: 35%; Re: NR | SF increased from 2.9 to 9.0 g/100; IF decreased from 89.9 to 82.9 g/100 g, and no effect on TF. | Zhong et al. [46] |

| Lupin fiber | T: 150 °C; Ss: 200 rpm; M: 20%; Re: NR | SF increased from 1.9 g/100 g to 37.7 g/100 g; IF decreased from 80.5% to 32.4% and TF decreased from 82.4% to 70.0%. | Naumann et al. [49] |

| Coffee hulls | T: 100 °C; Ss: 60 rpm; M: 32%; Re: Sulfuric acid (1% and 3%) and AHP (1% and 3%) | Increased IF (ranging from 77.17 to 78.86 g/100 g) compared to raw coffee hulls (65.97 g/100 g) | Jacinto et al. [50] |

T: Temperature; Ss: Screw speed; M: Moisture; Re: Reagent; NR: Not reported; TF: Total fiber; IF: Insoluble fiber; SF: Soluble fiber.

Benítez et al. [47] extruded coffee parchment flour under different temperature and moisture conditions without the use of chemical reagents. When the residue was processed at 135–150 °C with 15% moisture, a significant reduction of approximately 7% in insoluble fiber content was observed, contrasting with the results of the present study, in which a significant increase in fiber content was found. Conversely, increasing the temperature to 160–175 °C in combination with higher moisture (25%) resulted in a 9% increase in insoluble fiber content, reaching 84.3 g/100 g compared with the control. These values are higher than those observed in the present study (68.7–76.2 g/100 g; Table 1). According to these authors, this increase is related to the composition of the raw material, characterized by the predominance of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, in addition to the low availability of starch, which limits the solubilization of fibers during the extrusion process.

Yoshida et al. [36] extruded okara without the use of chemical reagents (115 rpm, 120 °C and moisture of 30%, 35%, and 40%) and they observed no significant difference in insoluble fiber content, which remained close to that of the control sample (50.27 g/100 g), in contrast to the results obtained in the present study, which had an average increase of 13.6% in the extruded samples (Table 1). On the other hand, the authors reported an average increase of 70% in soluble fiber content after extrusion, possibly due to the conversion of insoluble fibers into soluble fibers via the breakdown of covalent and non-covalent bonds between polysaccharides and between carbohydrates and proteins, resulting in smaller molecules with greater solubility. This behavior regarding the soluble fraction is consistent with that observed in this study, which showed an average increase of approximately 180% in soluble fiber content (Table 1).

Guo et al. [33] reported a significant reduction in insoluble fiber content in garlic skin samples subjected to extrusion without chemical reagents (25% moisture, 170 °C, and 170 rpm). The insoluble fiber content decreased from 72.01 g/100 g in the control sample to 45.29 g/100 g in the extruded sample. This reduction was attributed to structural degradation of the cell wall, with decreases of 26.2% in cellulose, 32.9% in hemicellulose, and 10.7% in lignin. These findings contrast with those of the present study, in which an increase in cellulose content was observed for the SCG-Control (18.9 g/100 g) and SCG-CA (27.4 g/100 g) samples, as well as an increase in lignin content in all extruded samples (37.7 g/100 g–54.4 g/100 g, Table 1).

Jacinto et al. [50], when subjecting coffee hulls to the reactive extrusion process (100 °C, 32% moisture, and 60 rpm) in combination with chemical reagents, sulfuric acid (1% and 3%), and AHP (1% and 3%), observed a significant increase in insoluble fiber content, with values ranging from 77.17 to 78.86 g/100 g, compared to raw coffee hulls (65.97 g/100 g). This increase was mainly attributed to the increase in cellulose content in the treated samples, especially in those subjected to reactive extrusion with AHP, which presented 45.17 g/100 g of cellulose, a value higher than that found in the present study (14.7 g/100 g–27.4 g/100 g, Table 1). Similar results were reported by Vilela et al. [51], who demonstrated that treatment with AHP promotes changes in the physical properties of the fibers, including lignin solubilization and reduction in cellulose crystallinity, contributing to the enrichment of the insoluble fraction.

Debiagi et al. [14] extruded oat hulls to obtain nanofibrillated cellulose. The samples were pretreated in a sequential extrusion protocol with a solution of 10% NaOH followed by a solution of 2% H2SO4, under specific conditions: 32% moisture, temperature of 110 °C, and screw speed of 100 rpm. The extrusion process with chemical reagents resulted in a 70.5% increase in cellulose content (53.14 g/100 g), along with a reduction in hemicellulose (18.38 g/100 g) and lignin (12.76 g/100 g) content. These results contrast with those obtained in the present study, in which an average increase of approximately 25.3% in lignin content (37.7 g/100 g–54.4 g/100 g, Table 1) was observed. These authors stressed that the treatment with chemical reagents is effective in removing the amorphous matrix composed of hemicellulose and lignin, promoting a higher concentration of cellulose in the treated samples.

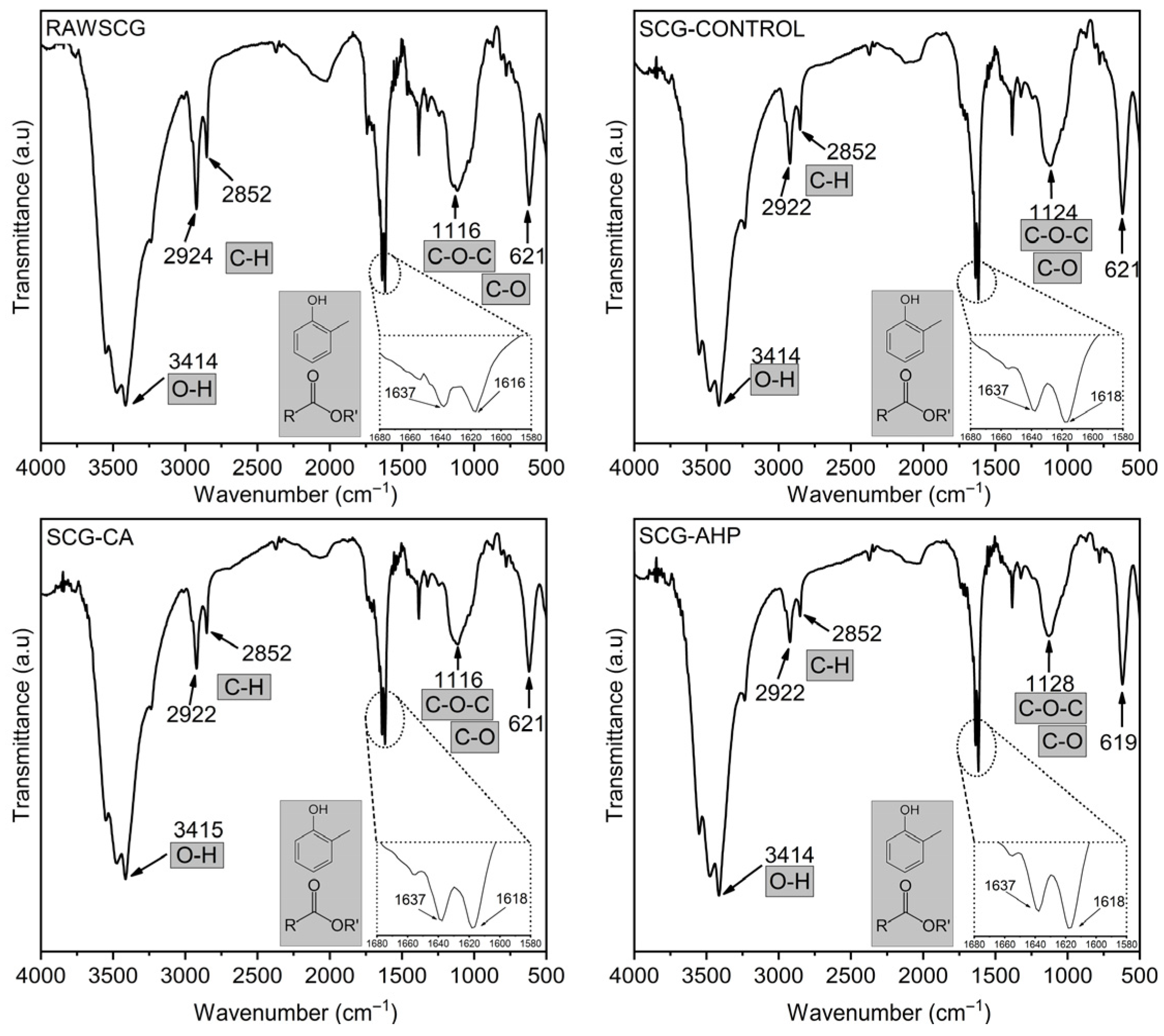

3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

The profile of structural chemical functional groups was identified by FTIR analysis, and the corresponding spectra are shown in Figure 2. The broad band observed around 3414 cm−1 is associated with O–H stretching vibrations [52,53]. Although the position of this band remains essentially unchanged among the samples, variations in its relative intensity are observed, suggesting modifications in hydrogen-bonding interactions resulting from the applied treatments.

Figure 2.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of Raw SCG, SCG-Control, SCG-CA, and SCG-AHP.

The doublet located at approximately 2922 cm−1 and 2852 cm−1 can be attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of C–H bonds in methoxy groups (–OCH3), which are abundant in hemicelluloses. Previous studies involving coffee residues and spent coffee grounds have also reported the presence of this doublet in FTIR spectra [53,54,55]. Comparative analysis of the relative intensities of these bands, after normalization to the C–O–C region (~1116 and 1128 cm−1), reveals a progressive reduction in the aliphatic fraction, particularly for the SCG-AHP sample. This trend is consistent with the compositional data presented in Table 1, which indicates a significant decrease in hemicellulose content.

In the region between 1637 cm−1 and 1618 cm−1, an overlap of bands characteristic of aromatic structures is observed. This region can be mainly assigned to C=C stretching vibrations of aromatic rings and, to a lesser extent, to C=O stretching of conjugated carbonyl groups, which are typical of phenolic units associated with lignin, such as ferulic and p-coumaric acids [56,57]. A comparative analysis of the relative intensities in this region reveals a more pronounced increase for the SCG-AHP sample, indicating a higher relative contribution of aromatic structures after treatment, in agreement with the data reported in Table 1. Some authors [58,59] associate the increased intensity in this region with chlorogenic acids and caffeine.

The bands between 1116 cm−1 and 1128 cm−1 can be assigned to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of C–O–C linkages in cellulose and hemicelluloses, as well as to C–O stretching of alcohols, ethers, and glycosidic bonds [57,60]. The lower variation observed in this spectral region among the samples supports the preservation of the main polysaccharide backbone, justifying its use as a reference band for the semiquantitative analysis of the other spectral regions.

3.3. Techno-Functional Properties of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

The techno-functional properties of food ingredients refer to their physico-chemical characteristics that influence their performance during processing and functionality in the final products. They are fundamental for the development of products with desirable texture, stability, appearance, and sensory acceptance [61].

Our results indicated that the treatments applied to raw SCG influenced its techno-functional properties in different ways (Table 3). Treatment with AHP (SCG-AHP) favored water retention, whereas treatment with citric acid (SCG-CA) improved the swelling capacity. Therefore, the choice of treatment should consider the desired functionality of the ingredient in the final formulation.

Table 3.

Techno-functional Properties of Raw SCG, SCG-Control, SCG-CA, and SCG-AHP.

WHC increased significantly (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) in the SCG-AHP sample (3.9 g/g) compared with the other samples, which showed similar values (3.5–3.6 g/g) (Table 3). This increase may be attributed to structural modifications induced by AHP treatment, which likely enhanced the exposure of hydrophilic groups and, consequently, increased affinity for water molecules [62]. In addition, Yoshida et al. [36] reported that the higher content of soluble fibers may contribute to this property. This property is desirable in food and technological applications where moisture retention is relevant, such as in the formulation of products with greater juiciness or stability.

OHC showed no significant difference (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) between the samples, with values varying between 2.7 and 2.8 g/g (Table 3). This indicates that the treatments applied, including the chemical ones, did not alter the hydrophobic characteristics or the structure of the fiber matrix related to lipid retention. This stability may be advantageous for applications in which consistent behavior in oily environments is required.

The extruded samples (SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control) presented statistically higher SC values (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05), ranging from 4.2 to 4.5 mL/g (Table 3), when compared to the raw SCG (3.9 mL/g). This behavior can be attributed to the combined effects of extrusion, which promotes structural changes in the fibrous matrix, making it more porous and hydrophilic. These changes enhance fiber hydration and volumetric expansion, thereby contributing to higher water retention compared with the raw material [37].

Okara extruded in a single-screw extruder without the addition of chemical reagents (115 rpm, 120 °C) and under different moisture levels (30%, 35%, and 40%) showed a significant increase in WHC compared to the control sample (non-extruded), reaching values between 10.73 and 11.09 g/g, higher than those observed in the present study (3.5 to 3.9 g/g; Table 3). As for OHC and SC, the samples processed with 35% and 40% moisture did not show statistically significant differences compared to the control sample. In contrast, samples with 30% moisture showed a 21.5% reduction in OHC (2.51 g/g), a result comparable to that observed in this study (2.7–2.8 g/g; Table 3). The same formulation also showed an 11.6% reduction in SC (6.47 mL/g), a value higher than that recorded in the present study (3.9–4.5 mL/g; Table 3) [36].

Jacinto et al. [50] subjected coffee hulls to reactive extrusion (100 °C, 32% moisture, 60 rpm) using sulfuric acid (1% and 3%) and AHP (1% and 3%) as reagents, and observed an increase in WHC in the extruded samples, with values ranging from 1.47 to 1.96 g/g, which were lower than those observed in the present study (3.5–3.9 g/g; Table 3). According to these authors, this increase is associated with physical and structural changes induced by the process, notably increased porosity, which makes the fibers more susceptible to interaction with water.

3.4. Cholesterol (CAC) and Glucose (GAC) Adsorption Capacities of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

The CAC and GAC of the different treatments applied to raw SCG resulted in significant differences (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) depending on pH (for CAC) and the glucose concentration in the medium (for GAC). These variations indicate structural and/or functional changes in the fibrous matrix resulting from the physical and chemical combined treatments.

The data (Table 4) demonstrate that chemical treatments, especially with citric acid (SCG-CA), promote changes in the fibrous matrix of SCG that favor the adsorption of glucose and cholesterol, especially under neutral pH conditions and at higher glucose concentrations. These changes can be exploited to develop functional ingredients with hypoglycemic and hypocholesterolemic potential, highlighting SCG as a promising source of functional dietary fiber.

Table 4.

Cholesterol (CAC) and glucose (GAC) adsorption capacities of raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control.

At pH 2, representative of the gastric environment, raw SCG showed the highest cholesterol adsorption capacity (CAC = 2.7 mg/g), significantly higher than the other treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) (Table 4). At pH 7, which simulates the intestinal environment, the behavior was the opposite: SCG-CA had the highest CAC (4.5 mg/g), followed by SCG-AHP (3.6 mg/g) and SCG-Control (3.2 mg/g). The lower CAC of raw SCG (1.6 mg/g) at this pH reinforces the importance of structural modifications in improving the functionality of dietary fiber-rich ingredients.

Similar results were obtained by Qiao et al. [63] when evaluating sweet potato residue subjected to extrusion at 40% moisture, 150 °C, and 180 rpm, without the addition of reagents. The CAC was 5.7 mg/g at pH 7 and 1.5 mg/g at pH 2, while in the raw sample it was 3.7 mg/g at pH 7 and 1.2 mg/g at pH 2, indicating a higher cholesterol adsorption capacity in a neutral medium than in an acidic one for the extruded residue.

GAC was evaluated at two glucose concentrations (50 and 100 mmol/L). At a concentration of 50 mmol/L, the SCG-CA sample showed the highest adsorption value, reaching 8.3 mmol/L of glucose, a result significantly higher than the other treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05; Table 4). At a concentration of 100 mmol/L, the treatments with citric acid (SCG-CA) and AHP (SCG-AHP) exhibited similar values, ranging from 32.7 to 31.1 mmol/L (Table 4), both significantly higher than the other treatments (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05). These findings indicate that acidic and oxidative conditions applied in reactive extrusion were particularly effective in increasing the affinity of the treated residues for glucose.

Raw SCG exhibited the lowest adsorption capacity at both glucose concentrations, suggesting that the native structure of the residue has limited potential for interaction with glucose, possibly due to structural constraints or the lack of functional groups capable of promoting effective interactions.

According to Zhang et al. [64], the increase in GAC in treated food fibers is probably related to greater porosity and an increase in the contact surface area. In addition, the exposure of cellulose functional groups and the easier access of solutes to the interior of the fibers intensify van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonds with glucose molecules, thus increasing GAC.

3.5. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control

Table 5 presents the bioactive compounds concentrations and antioxidant activity of raw SCG and treated samples. The raw SCG had the highest levels of total phenolic compounds (TPC, 1.38 g GAE/100 g), accompanied by the highest antioxidant capacity in the ABTS (267.4 mg TE/100 g) and DPPH (2015.2 mg TE/100 g) analyses (Table 5). These data confirm the essential role of polyphenols in the antioxidant activity of SCG, as already demonstrated by Zhang and Tsao [65], who reported a strong correlation between TPC and free radical scavenging potential.

Table 5.

Bioactive compounds concentrations and antioxidant activity of raw SCG, SCG-CA, SCG-AHP, and SCG-Control.

Treatments with citric acid (SCG-CA) and AHP (SCG-AHP) caused drastic reductions in TPC and antioxidant capacities (Table 5). SCG-CA showed a drop of 85.5%, 95.1%, and 53.2% in TPC, DPPH, and ABTS, while SCG-AHP reduced it by 71.0%, 94.7% and 52.3%, respectively. This decrease may be due to the oxidation of compounds due to the chemical reagents, but also, according to Arribas et al. [66], to the leaching process in the washing stages.

SCG-Control presented a decrease in TPC (1.28 g GAE/100 g), which differed statistically (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) from raw SCG, but more significant losses in antioxidant activity by DPPH (94.6%) and ABTS (30.9%), which suggests that although total phenolics are preserved, there may be degradation of more reactive fractions or changes in the chemical structure of these compounds. Studies by Aguilar-Ávila et al. [67] suggested that extrusion heat and high moisture can reduce the antioxidant activity of polyphenols.

Zhang et al. [68] reported that extrusion without the use of chemical reagents can lead to variations in the phenolic compound profiles among different rice fractions. In contrast to the findings of the present study, rice bran exhibited a 7.3% increase in free phenolic content after extrusion. However, the findings regarding polished rice and brown rice corroborate the results obtained here, since there was a 53.7% and 57.0% reduction, respectively, in the free phenolic content.

ME are polymeric compounds formed during the Maillard reaction throughout the coffee roasting process, and the highest statistically significant value (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) was observed for the raw SCG sample (6640.8 mg/100 g; Table 5). Montemurro et al. [69] reported lower concentrations than those obtained in the present study for raw SCG, recording 1192.0 mg/100 g of ME. The SCG-Control sample showed a 27.1% reduction compared to raw SCG, while SCG-CA and SCG-AHP showed even more pronounced losses, corresponding to 60.2% and 68.6%, respectively (Table 5).

According to Montemurro et al. [69], ME can incorporate chlorogenic acids during the roasting process and contribute significantly to antioxidant activity. Thus, the decrease in the content of these molecules may be related to the reduction in antioxidant activity in the DPPH and ABTS analyses observed for the SCG-Control, SCG-CA, and SCG-AHP samples (Table 5).

As shown in Table 5, SCG-Control exhibited the highest caffeine (1082.5 mg/100 g) and CGA (2698.2 mg/100 g) contents, differing statistically (Tukey’s test, p ≤ 0.05) from the other treatments. These results suggested that moderate heating associated with shear stress promotes the release of these compounds without causing their degradation. This behavior is consistent with the findings of Ortiz-Cruz et al. [70], who report that extrusion heating is capable of breaking the interactions between the matrix and bioactive compounds, increasing their availability for extraction.

However, treatments with citric acid and AHP resulted in substantial reductions in the levels of these compounds. For caffeine, decreases of 85.0% (SCG-CA) and 46.5% (SCG-AHP) were observed, while for CGA, the reductions corresponded to 38.8% (SCG-CA) and 25.1% (SCG-AHP) (Table 5), when compared to the raw sample. Such losses may be related to the instability of these compounds under acidic pH conditions or in oxidizing environments. This behavior corroborates Bevilacqua et al. [11], who highlight that, although extrusion is a technology capable of modulating bioactive compounds in SCG, its effects are dependent on the processing parameters and subsequent treatments applied to the material.

In this study, chemically assisted extrusion promoted significant structural modifications in the dietary fiber matrix, such as the partial solubilization of hemicellulose and the breakdown of lignin, which contributed to the improvement of the fiber’s functional properties. However, these same structural alterations likely facilitated the degradation, oxidation, or leaching of low molecular weight bioactive compounds, particularly phenolics, and consequently the antioxidant activity, due to their greater exposure to reactive chemical species and processing conditions. Thus, the results indicate that the applied treatments favored the functionality of the fiber, although they partially compromised the retention of bioactive compounds, reflecting that there must be an inherent balance between structural enhancement and bioactive preservation.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that reactive extrusion is an effective strategy for reconfiguring the lignocellulosic matrix of SCG, resulting in significant improvements in chemical composition, techno-functional properties, and bioactivity. Among the treatments evaluated, the reactive extrusion treatment with citric acid, SCG-CA, promoted greater enrichment in total and insoluble fibers, especially cellulose, and resulted in materials with high glucose and cholesterol adsorption capacity at neutral pH, suggesting promising application in foods with functional claims. Treatment with alkaline hydrogen peroxide increased the lignin content and water retention capacity, desirable characteristics for technological applications.

However, chemical treatments associated with extrusion (SCG-CA and SCG-AHP) intensified losses of bioactive compounds, with significant reductions in TPC, melanoidins, caffeine, and chlorogenic acid contents. These results reinforce that, although extrusion facilitates the release of compounds from the lignocellulosic matrix, the choice of reagent and pH conditions is decisive for preserving the functional quality of the ingredient.

Extrusion without reagents, SCG-Control, proved to be effective for the preservation and release of caffeine and chlorogenic acids. In addition, it increased soluble fibers and antioxidant capacity, although it partially reduced the antioxidant capacity measured by DPPH, possibly due to the degradation of highly reactive phenolic fractions.

Overall, extruded SCG showed potential for application as an ingredient in fiber-enriched food formulations. From both environmental and industrial perspectives, the valorization of SCG contributes to waste reduction and aligns with the principles of a circular economy. In this context, reactive extrusion emerges as a promising, sustainable, and economically feasible approach for transforming lignocellulosic residues into value-added ingredients, with potential applications in various food systems.

This study has limitations that should be considered; the results cannot be generalized to other agro-industrial residues, since lignocellulosic materials are highly complex and heterogeneous, with compositions that vary widely in terms of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and associated bioactive compounds. This compositional variability strongly influences their response to thermomechanical processing and chemical treatments. Furthermore, the use of chemical reagents can sensitize these raw materials, promoting selective degradation or transformation of structural polymers and bioactive fractions. Therefore, the observed effects are specific to the characteristics of SCG and the processing conditions applied, and extrapolation to other residues or pilot and industrial scales should be investigated in subsequent stages of this work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and M.T.B.; methodology, J.B.M.D.S.; formal analysis, J.B.M.D.S., F.A.C., E.L., N.S. and M.T.P.P.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation J.B.M.D.S.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; supervision, S.M. and M.T.B.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. and M.T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CAPES-DS (Brazil), FINEP (01.21.0126.00—REF. 0128/2021), and Fundação Araucária. The APC was funded by Superintendência de Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior (SETI), Fundação Araucária and Universidade Estadual de Londrina (PROPPG).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAC | Cholesterol adsorption capacity |

| CGA | Total chlorogenic acids |

| GAC | Glucose adsorption capacity |

| ME | Melanoidins |

| OHC | Oil holding capacity |

| SC | Swelling capacity |

| SCG | Spent coffee grounds |

| SCG-Control | Spent coffee grounds extruded without the use of reagents |

| SCG-CA | Spent coffee grounds treated with citric acid and reactive extrusion |

| SCG-AHP | Spent coffee grounds treated with alkaline hydrogen peroxide and reactive extrusion |

| WHC | Water holding capacity |

References

- Navajas-Porras, B.; Castillo-Correa, M.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Montalbán-Hernández, C.; Peña-Guzmán, D.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Romero-Márquez, J.M. The Valorization of Coffee By-Products and Residue Through the Use of Green Extraction Techniques: A Bibliometric Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.-T.; Zwicker, M.; Wang, X. Coffee: One of the Most Consumed Beverages in the World. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 3rd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- ABIC—Associação Brasileira da Indústria de Café. Indicadores da Indústria de Café. 2025. Available online: https://www.abic.com.br/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- National Coffee Data Trends Report 2025. More Americans Drink Coffee Each Day Than Any Other Beverage, Bottled Water Back in Second Place. Available online: https://www.ncausa.org/Newsroom/More-Americans-Drink-Coffee-Each-Day-Than-Any-Other-Beverage-Bottled-Water-Back-in-Second-Place (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Tavares, M.P.F.; Mourad, A.L. Coffee beverage preparation by different methods from an environmental perspective. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Toward Circular Economy: Potentials of Spent Coffee Grounds in Bioproducts and Chemical Production. Biomass 2024, 4, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidło, W.; Latosińska, J. Reuse of Spent Coffee Grounds: Alternative Applications, Challenges, and Prospects—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Vergara-Castañeda, H.A.; Oomah, B.D. Spent coffee grounds: A review on current research and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, Q.; Brooks, M.S.-L.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Innovative technologies used to convert spent coffee grounds into new food ingredients: Opportunities, challenges, and prospects. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo-Dehond, A.; Casas, A.R.; Del-Castillo, M.D. Interest of coffee melanoidins as sustainable healthier food ingredients. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 730343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, E.; Rose’Meyer, R.; Singh, I.; Grice, D.; Mouatt, P.; Brown, L.; Cruzat, V. Bioactive compounds of spent coffee grounds and their potential use as functional food. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2024, 83, E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, B.Y.; Prudencio, S.H. Alkaline hydrogen peroxide improves physical, chemical, and techno-functional properties of okara. Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarin, H.M.; Murillo-Franco, S.L.; Santos, M.C.M.; Silva, D.D.V.; Dussán, K.J. Acid hydrolysis pretreatment for extraction of oligosaccharides derived from spent coffee grounds: Valorization of a promising biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiagi, F.; Faria-Tischer, P.C.S.; Mali, S. A green approach based on reactive extrusion to produce nanofibrillated cellulose from oat hull. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Coţovanu, I.; Mironeasa, C.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M. A Review of the Changes Produced by Extrusion Cooking on the Bioactive Compounds from Vegetal Sources. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 19th ed.; AOAC International: Arlington, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J. Symposium on factors influencing the voluntary intake of herbage by ruminants: Voluntary intake in relation to chemical composition and digestibility. J. Anim. Sci. 1965, 24, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappi test method T222 om-88. Acid-insoluble lignin in wood and pulp. In Tappi Test Methods; Tappi Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, V.; Cantera, S.; Aguilera, Y.; Mollá, E.; Esteban, R.M.; Díaz, M.F.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A. Impact of germination on starch, dietary fiber and physicochemical properties in non-conventional legumes. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Aparicio, I.; Mateos-Peinado, C.; Rupérez, P. High hydrostatic pressure improves the functionality of dietary fiber in okara by-product from soybean. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Xie, M.; Nie, S.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Yu, Q. Structural characteristics and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber from defatted rice bran obtained through Trichoderma viride fermentation. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 94, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, V.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Hernanz, S.; Chantres, S.; Aguilera, Y.; Martin-Cabrejas, M.A. Coffee parchment as a new dietary fiber ingredient: Functional and physiological characterization. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, J.A.; Bassoli, D.G.; Benassi, M.T. Antioxidant activity of roasted and instant coffees: Standardization and validation of methodologies. Coffee Sci. 2012, 7, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Folin, O.; Ciocalteu, V. On tyrosine and tryptophane determinations in proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1927, 73, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinis, T.C.; Maderia, V.M.; Almeida, L.M. Action of phenolic derivatives (acetaminophen, salicylate, and 5-aminosalicylate) as inhibitors of membrane lipid peroxidation and as peroxyl radical scavengers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 315, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, A.L.B.; Viegas, M.C.; Ferrão, M.A.G.; Fonseca, A.F.A.; Ferrão, R.G.; Benassi, M.T. Coffee brews composition from Coffea canephora cultivars with different fruit ripening seasons. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, D.; Verzelloni, E.; Conte, A. Effect of dietary melanoidins on lipid peroxidation during simulated gastric digestion: Their possible role in the prevention of oxidative damage. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 2513–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viencz, T.; Acre, L.B.; Rocha, R.B.; Alves, E.A.; Ramalho, A.R.; Benassi, M.T. Caffeine, trigonelline, chlorogenic acids, melanoidins, and diterpenes contents of Coffea canephora coffees produced in the Amazon. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 117, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.; Ali, H.; Bareh, G.; Farouk, A. Influence of spent coffee ground as fiber source on chemical, rheological and sensory properties of Sponge Cake. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 22, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, A.; Mahmoud, E.; Aslam, M.; Naqvi, S.R.; Juchelková, D.; Bhatia, S.K.; Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.Y.; Hoang, A.T.; Palacky, P. Emerging potential of spent coffee ground valorization for fuel pellet production in a biorefinery. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 7585–7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, W.; Wu, B.; Wu, P.; Duan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Ma, H. Modification of garlic skin dietary fiber with twin-screw extrusion process and in vivo evaluation of Pb binding. Food Chem. 2018, 268, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Zamora, A.; Pastoriza, S.; Rufían-Henares, J.A. Revalorization of coffee by-products. Prebiotic, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 61, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andirigu, A.R.; Nyanga, L.K.; Chopera, P. Effects of extrusion on nutritional and non-nutritional properties in the production of multigrain ready-to-eat snacks incorporated with NUA45 beans. N. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 7, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, B.Y.; Da Silva, P.R.C.; Prudencio, S.H. Soybean residue (okara) modified by extrusion with different moisture contents: Physical, chemical, and techno-functional properties. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2022, 29, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ryu, G.-H. Effects of pea protein content and extrusion types on physicochemical properties and texture characteristics of meat analogs. JSFA Rep. 2023, 3, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Giraldo, G.A.; Mantovan, J.; Marim, B.M.; Kishima, J.O.F.; Mali, S. Surface Modification of Cellulose from Oat Hull with Citric Acid Using Ultrasonication and Reactive Extrusion Assisted Processes. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Kumar, D.; Girdhar, M.; Sharma, A.; Mohan, A. Steam Explosion Pretreatment with Different Concentrations of Hydrogen Peroxide along with Citric Acid: A Former Step towards Bioethanol Production. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 2492528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Ain, H.B.; Saeed, F.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Niaz, B.; Tufail, T. Improving the physicochemical properties of partially enhanced soluble dietary fiber through innovative techniques: A coherent review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Mao, J.W.; Cai, C.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, J.; Yuxin, S.; Sha, R. Effects of twin-screw extrusion on physicochemical properties and functional properties of bamboo shoots dietary fiber. J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2017, 11, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapana, F.; Vidaurre-Ruiz, J.; Linares-García, L.; Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R. Exploring the Future of Extrusion with Andean Grains: Macromolecular Changes, Innovations, Future Trends and Food Security. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Barros, L.; Fernandes, Â.; Berrios, J.D.J.; Cámara, M.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of extruded snack-type products developed from novel formulations of lentil and nutritional yeast flours. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, P.-N.; Han, S.-Y.; Park, C.-W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, N.-H.; Lee, S.-H. Effect of alkaline peroxide treatment on the chemical compositions and characteristics of lignocellulosic nanofibrils. BioResources 2019, 14, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konan, D.; Koffi, E.; Ndao, A.; Peterson, E.C.; Rodrigue, D.; Adjallé, K. An Overview of Extrusion as a Pretreatment Method of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Energies 2022, 15, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Fang, Z.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Hodgson, J.M.; Johnson, S.K. Extrusion cooking increases soluble dietary fibre of lupin seed coat. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 99, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, V.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Aguilera, Y.; Bejerano, S.; Cañas, S.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A. Extruded coffee parchment shows enhanced antioxidant, hypoglycaemic, and hypolipidemic properties by releasing phenolic compounds from the fibre matrix. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1097–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Chi, Y.-J. Effects of twin-screw extrusion on soluble dietary fibre and physicochemical properties of soybean residue. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, S.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Martin, A.; Schuster, M.; Eisner, P. Effects of extrusion processing on the physiochemical and functional properties of lupin kernel fibre. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 111, 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacinto, J.S.; Mantovan, J.; Da Silva, J.B.M.D.; Mali, S. Reactive extrusion process to obtain a multifunctional fiber-rich ingredient from coffee hull. Rev. Principia 2025, 62, e8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, W.F.; Leão, D.P.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Effect of peroxide treatment on functional and technological properties of fiber-rich powders based on spent coffee grounds. Int. J. Food Eng. 2016, 2, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košťálová, Z.; Manavaki, M.; Christaki, S.; Papadakis, E.-N.; Mourtzinos, I. Structure Investigation of Polysaccharides Extracted from Spent Coffee Grounds Using an Eco-Friendly Technique. Processes 2024, 12, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, M.T.P.; Da Silva, J.B.M.D.; De Carvalho, F.A.; MALI, S. Cellulose from coffee hulls: Chlorine-free extraction using a green single-step process with peracetic acid. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 4555–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.R.; El-Sayed, S.A.; Eltaher, M.A.; Mohammad, A.; Almitani, K.H.; Mostafa, M.E. Pyrolysis kinetics and thermal degradation characteristics of coffee, date seed, and prickly pear residues and their blends. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.O.; Batista, M.J.A.; Ávila, A.F.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Development and characterization of biopolymeric films of galactomannans recovered from spent coffee grounds. J. Food Eng. 2021, 289, 110083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, P.J.R.; Ascheri, D.P.R.; Santos, M.L.S.; Morais, C.C.; Ascheri, J.L.R.; Signini, R.; Dos Santos, D.M.; De Campos, A.J.; Devilla, I.A. Soybean hulls: Optimization of the pulping and bleaching processes and carboxymethyl cellulose synthesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsa, P.; Phatikulrungsun, P.; Prathumthong, S. FT-IR characteristics, phenolic profiles and inhibitory potential against digestive enzymes of 25 herbal infusions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.S.; Salva, T.J.; Ferreira, M.M.C. Chemometric studies for quality control of processed brazilian coffees using drifts. J. Food Qual. 2010, 33, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Chemical, Functional, and Structural Properties of Spent Coffee Grounds and Coffee Silverskin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejenari, V.; Marcu, A.; Ipate, A.-M.; Rusu, D.; Tudorachi, N.; Anghel, I.; Şofran, I.-E.; Lisa, G. Physicochemical characterization and energy recovery of spent coffee grounds. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4437–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, D.; Latrofa, V.; Caponio, F.; Pasqualone, A.; Summo, C. Techno-functional properties of dry-fractionated plant-based proteins and application in food product development: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Xie, C.; Hang, F.; Li, K.; Shi, C. Effect of alkaline hydrogen peroxide assisted with two modification methods on the physicochemical, structural and functional properties of bagasse insoluble dietary fiber. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1110706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Shao, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Guan, W. Modification of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) residues soluble dietary fiber following twin-screw extrusion. Food Chem. 2021, 335, 127522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, J. Fine extraction of cellulose from corn straw and the application for eco-friendly packaging films enhanced with polyvinyl alcohol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arribas, C.; Cabellos, B.; Cuadrado, C.; Guillamón, E.; Pedrosa, M.M. The effect of extrusion on the bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of novel gluten-free expanded products based on carob fruit, pea and rice blends. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 52, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Avila, D.S.; Martinez-Flores, H.E.; Morales-Sanchez, E.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Garnica-Romo, M.G. Effect of extrusion on the functional properties and bioactive compounds of tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) shell. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2023, 73, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Khan, S.A.; Chi, J.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M. Different effects of extrusion on the phenolic profiles and antioxidant activity in milled fractions of brown rice. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 88, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemurro, M.; Casertano, M.; Vilas-Franquesa, A.; Rizzello, C.G.; Fogliano, V. Exploitation of spent coffee ground (SCG) as a source of functional compounds and growth substrate for probiotic lactic acid bactéria. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 198, 115974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Cruz, R.A.; Ramírez-Wong, B.; Ledesma-Osuna, A.I.; Torres-Cháves, P.I.; Sánchez-Machado, D.I.; Montaño-Leyva, B.; López-Cervantes, J.; Gutiérrez-Dorado, R. Effect of Extrusion Processing Conditions on the Phenolic Compound Content and Antioxidant Capacity of Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) Bran. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.