Abstract

Curcumin is widely used for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, but its poor oral bioavailability has driven the development of advanced formulations such as CAVACURMIN®, a γ-cyclodextrin-based curcumin complex with enhanced absorption. Given recent regulatory scrutiny of high-bioavailability curcumin products, we evaluated the subacute oral safety of CAVACURMIN® in Wistar rats. Animals received 2000 mg/kg/day (low dose) or 3500 mg/kg/day (high dose) for 28 days, with controls receiving vehicle or γ-cyclodextrin alone. No mortality or systemic toxicity occurred, except for one incidental death unrelated to treatment. Transient post-dosing signs (salivation, bedding displacement) were attributed to local sensory or irritant effects. Clinical chemistry showed modest, non-adverse variations—including decreased urea (up to −25% in males) and increased albumin (up to +9% in females)—that were not associated with pathological or clinical abnormalities. All other parameters, including body weight, food intake, haematology, organ weights (except for a small, non-adverse liver-weight increase in high-dose females), and gross pathology, were comparable to controls. These findings demonstrate that CAVACURMIN® was well tolerated at doses up to 3500 mg/kg/day and provide a basis for subsequent OECD 408-compliant 90-day toxicity studies.

1. Introduction

Curcumin, the principal bioactive compound in the spice turmeric, has attracted global attention in recent decades after its discovery in 1870 due to its potential health benefits and therapeutic properties [1]. Promising results from both preclinical and clinical studies suggest that it possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-carcinogenic effects [2,3,4]. However, the clinical evidence remains mixed, often limited by issues such as low bioavailability, small sample sizes, and variability in study design. Despite these challenges, curcumin-containing products are widely used in food supplements, traditional medicine, and, increasingly, in pharmaceutical applications [5,6]. Curcumin is poorly soluble in water, which significantly limits its bioavailability. In addition to its low aqueous solubility, curcumin also exhibits poor gastrointestinal absorption, undergoes rapid Phase II metabolism in the liver and intestinal wall, and is quickly eliminated from the body [7,8,9].

These pharmacokinetic limitations result in low plasma and tissue concentrations after oral administration. Various strategies have been developed to improve its bioavailability, including complexation with carrier systems such as cyclodextrins, liposomes, micelles, or nanoparticles [10]. Co-administration with fatty foods and the use of bioenhancers such as piperine—a compound found in black pepper that not only improves absorption but also inhibits hepatic metabolism—can further enhance systemic availability and therapeutic potential [11].

In recent years, regulators and toxicologists have increasingly emphasised that improvements in curcumin’s oral absorption may alter its metabolic and safety profile [12,13]. Formulations that markedly increase systemic exposure—such as micellar, phospholipid, or cyclodextrin complexes—can reach plasma levels several hundred times higher than those achieved with unformulated curcumin. While this improvement enhances potential efficacy, it also raises legitimate toxicological questions regarding long-term exposure, metabolic saturation, and possible tissue accumulation [14].

Millions of people worldwide consume curcumin, either as dietary supplements or as an ingredient in functional foods. There is an international consensus that orally administered unmodified curcumin is safe across a wide range of doses. Toxicity studies on unmodified curcumin have established an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) of 3 mg/kg body weight per day, derived from a No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) of 250–320 mg/kg body weight per day by applying an uncertainty factor of 100 [15].

JECFA has derived an extremely conservative ADI from a NOAEL from a No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) of 250–320 mg/kg body weight per day by applying an uncertainty factor of 100. While the authors concluded on the next higher dose level as the NOAEL, JECFA has used some minor effects of questionable toxicological relevance for the ADI [16]. For an average 60 kg person, the ADI of 3 mg/kg body weight per day corresponds to approximately 180 mg per day.

However, it is important to recognise that safety data derived from unmodified curcumin may not directly apply to formulations with enhanced bioavailability. This concern came to the forefront in the last five years, when several cases of hepatotoxicity were reported and appeared to be associated with the consumption of curcumin [12,17,18]. These case reports prompted renewed scrutiny by national and international regulatory bodies. Between late 2023 and 2024, several European and North American agencies initiated coordinated safety evaluations of bioavailability-enhanced curcumin products. The European Heads of Food Safety Agencies (HoA) specifically highlighted the need for standardised, OECD-compliant toxicological testing to differentiate formulation-related effects from those intrinsic to curcumin itself. This regulatory focus reflects a wider movement toward evidence-based risk assessment of food supplements that employ pharmaceutical-grade delivery technologies.

The use of dietary supplements containing turmeric, curcumin, or CAVACURMIN® has increasingly come under scrutiny, as regulators cannot exclude the possibility that (high) doses of curcumin—particularly those with enhanced bioavailability—may exert off-target or even toxic effects. However, the database of reported human cases is limited and complex. A clear relationship to bioavailability enhancement could neither be proven nor refuted. Consequently, the Heads of Food Safety Agencies (HoA) requested, in a letter dated 6 June 2024, that the safety of CAVACURMIN® be evaluated through an Article 8 procedure under EC Regulation No 1925/2006 (First report of the HOA working group “Food supplements”, BVL 6 June, 2024).

For this reason, products designed to increase the bioavailability of curcuminoids must undergo a thorough safety assessment, especially given the wide variety of technologies employed and their potential specific effects related to the active compound curcumin. Against this backdrop, CAVACURMIN®—a γ-cyclodextrin complex that increases curcumin’s systemic availability up to forty-fold compared with native curcumin—represents an important model system for evaluating the safety of such enhanced formulations [19]. Although its pharmacokinetic advantages are well established, comprehensive subacute and subchronic toxicity data have not been publicly available. Filling this gap is critical not only for regulatory evaluation but also for guiding safe dosage limits in future human studies.

Conducting a toxicity study for CAVACURMIN®, which is currently sold as a food supplement, is essential for both consumer protection and scientific and regulatory evaluation. As a dietary supplement, it is not subject to pre-market approval by regulatory authorities but was instead placed on the market following a notification procedure. Moreover, CAVACURMIN® is reported to have GRAS status and to be recognised as a novel food ingredient. A systematic investigation of its potential toxic effects would help define clear limits for safe intake and provide a basis for evidence-based recommendations. This is particularly important as curcumin is increasingly explored as a future potential therapeutic agent in conditions such as cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and inflammatory disorders [20,21,22]. Without a sound toxicological assessment, clinical trials could be jeopardised, and the development of curcumin-based therapeutics could stall.

Regulatory authorities, including the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), require comprehensive safety data before a substance can be classified as safe or approved for therapeutic use. Therefore, this investigation was conceived in direct response to the 2024 HoA request for updated safety information on γ-cyclodextrin-complexed curcumin preparations. By adhering to internationally accepted OECD principles and focusing on both local and systemic tolerability, it contributes to the evidence base required by food safety and health authorities in the EU, the US FDA, and other jurisdictions.

In 2024, the European Heads of Food Safety Agencies (HoA) requested a renewed safety evaluation of high-bioavailability curcumin formulations under an Article 8 procedure of Regulation 1925/2006. This reflected emerging regulatory scrutiny following isolated reports of hepatic adverse events and the recognition that enhanced-absorption systems may alter curcumin’s kinetic and metabolic profile. To address this evidence gap, the current 28-day study was designed as an OECD-compliant dose-range-finding investigation to establish systemic and local tolerability data for CAVACURMIN® and to define an appropriate top dose for subsequent 90-day studies [23]. By linking regulatory needs with standardised toxicological endpoints, this work provides the first transparent preclinical safety dataset for γ-cyclodextrin-complexed curcumin.

The present study addresses this regulatory and scientific gap by evaluating the subacute oral toxicity profile of CAVACURMIN® in Wistar rats. Using two dose levels (2000 and 3500 mg/kg/day) and including both vehicle and γ-cyclodextrin controls, this investigation aimed to achieve the following:

- Identify any treatment-related systemic or local adverse effects over a 28-day period.

- Assess potential biochemical or liver weight changes, with interpretation in the context of historical control ranges.

- Establish an appropriate high dose for subsequent OECD 408-compliant 90-day studies [23].

- Clarify if γ-cyclodextrin, which makes up a major part of the formulation, may be responsible for any observed effect and should be examined as a 2nd control group in the subchronic study.

Collectively, these objectives align with current regulatory expectations for establishing a scientifically robust foundation for subsequent 90-day studies and for supporting future submissions under OECD 408 and EU Regulation 1925/2006 [23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterisation of the Test Item

The identity of the test item, CAVACURMIN® (Batch No.: N385030522), was confirmed upon delivery by comparing the test item name, batch number, and other provided data with the label specifications. CAVACURMIN® was received as an orange, solid powder containing 18.3% curcuminoids (a mixture of CAS 458-37-7, CAS 22608-11-3, and CAS 24939-16-0) and 73%

γ-cyclodextrin (CAS 17465-86-0). Impurities were not included in the final formulation. The material was stored at 2–8 °C, protected from light, and had an expiry date of March 2025. Routine hygienic procedures were deemed sufficient to ensure personnel safety.

2.2. Characterisation of the Control Substance

The second control group (C2) received CAVAMAX® W8 (Batch No.: 801278), consisting of 98.7% γ-cyclodextrin (CAS 17465-86-0). The substance was stored at 2–8 °C and protected from light. The expiry date was February 2025. Standard hygienic protocols were followed to ensure safe handling.

2.3. Characterisation of the Vehicle

The vehicle used in the study was a 1% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) solution prepared using carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, Batch No.: SLCK1957) and aqua ad injectionem (Deltamedica, Reutlingen, Germany, Batch No.: 2210342). CMC was a solid stored at room temperature (expiry: 18 May 2027), and aqua ad injectionem was a liquid stored at room temperature (expiry: September 2025). Both were handled under standard hygienic conditions.

2.4. Preparation of the Test Item and Control Formulations

Formulations were prepared to contain 200 mg/mL and 350 mg/mL of CAVACURMIN® for the low- and high-dose groups, respectively, and were freshly prepared each administration day. Each formulation was suspended in 1% CMC, which was selected based on the test item’s properties and prepared weekly. The weighed test item or control substance was combined with the vehicle to achieve target concentrations and stirred until visually homogenous. During administration, formulations were kept under continuous magnetic stirring. The vehicle alone served as the control item.

2.5. Test System

The experimental phase was conducted from 16 May to 3 July 2023 at Eurofins BioPharma Product Testing Munich GmbH (Planegg, Germany) under GLP-like conditions. The study used Wistar rats (Crl: WI [Han]) sourced from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). Both male and female animals were used (non-pregnant and nulliparous females). Animals were 7–8 weeks old at treatment initiation. Body weights at group allocation were 239–269 g for males (mean: 252.85 g) and 155–175 g for females (mean: 166.45 g). Animals were bred under SPF conditions, and the study was conducted in an AAALAC-accredited facility, with ethical approval from the Bavarian animal welfare authority. Carcasses were disposed of according to institutional biosafety and German hazardous-waste regulations (TierSchG § 17).

2.6. Housing and Feeding Conditions

Animals were housed five per sex per cage (minimum floor area 1800 cm2) in Makrolon® Type IV cages. Environmental conditions included a temperature of 22 ± 3 °C, relative humidity of 40–70%, and a 12 h light/dark cycle. Room air was exchanged 10 ± 2 times per hour by central ventilation. Documentation for feed, water, and bedding quality was archived according to institutional procedures (Study No. 2200461) for 10 years. Animals had ad libitum access to Altromin 1324 diet and acidified tap water (pH ~2.8). Food, water, and bedding were certified, and records were archived. Animals were acclimatised for 7 days prior to treatment.

2.7. Number and Sex of Animals

A total of 40 animals (20 males and 20 females) were used, with five animals per sex per group. That equates to five rats per sex per group (n = 10 per dose level). Each sex was treated as an independent replicate group.

2.8. Preparation of the Animals

Prior to treatment, animals underwent detailed clinical observation and were weighed. Only healthy animals were selected. Animals were randomised into groups using IDBS E-WorkBook 21.9.0 to ensure homogenous body weight distribution.

2.9. Experimental Groups and Doses

Four groups of 5 animals for each sex were established (total 40): two control groups (C1: vehicle; C2: CAVAMAX® W8 at 2555 mg/kg bw/day), a low dose (CAVACURMIN LD: 2000 mg/kg bw/day), and a high dose (HD: 3500 mg/kg bw/day) group. Doses were administered twice daily (2 × 10 mL/kg bw) for 28 consecutive days. Animals were weighed weekly, and the administration volume for each animal was calculated from its most recently recorded body weight.

2.10. Administration of Doses

Formulations were administered by oral gavage twice daily, in the morning between 06:15 and 11:59, and in the afternoon between 12:00 and 17:00. Individual dosing volumes were based on the most recent body weights.

2.11. Body Weight and Food Consumption

Body weights were recorded pre-treatment, and on Days 1, 8, 15, 22, and 28, and at necropsy. Food consumption was recorded for intervals Day 1–8, 8–15, 15–22, and 22–28.

2.12. Clinical Observations

Clinical signs were assessed daily, including morbidity and mortality checks (twice daily on weekdays, once on weekends/public holidays). Observations were timed to detect peak effects. Salivation incidence was recorded daily as presence/absence per animal; percentages were calculated relative to the total animals per group. Hairless areas were scored semi-quantitatively (0 = none, 1 = <25%, 2 = 25–75%, 3 = >75%), with baseline values established during acclimatization.

2.13. Haematology, Clinical Biochemistry, Pathology, and Organ Weights

At study end, following overnight fasting, blood from the abdominal aorta was collected in EDTA tubes for haematology analysis using an ADVIA®120 (Siemens, Munich, Germany) and in serum separator tubes for biochemical analysis using an Olympus AU 480 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). All surviving animals were euthanised on Day 29 under anaesthesia (ketamine/xylazin) and subjected to gross necropsy, including examination of external and internal organs. Macroscopic abnormalities and all livers were preserved in 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde. Animals that died or were euthanised prematurely were also necropsied. The wet weight of livers from all animals was recorded immediately after necropsy.

2.14. Evaluation of Results

Body weight gain and food consumption were calculated weekly. Data were presented in summary tables or individual listings. Toxicological and pathological results were recorded in compliance with SOPs, either on paper or via the Ascentos® System (version 1.3.4, Pathology Data Systems Ltd., Basel, Switzerland).

2.15. Guidelines and Archiving

This study followed the procedures as indicated in the following internationally accepted guidelines and recommendations:

- OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4, No. 408, “Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents,” adopted 25 June 2018 [1].

- Commission Regulation (EC) No. 440/2008, L 142, Annex Part B, 30 May 2008 [2].

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes [3].

The national animal protection law, which governs the protection of animals used in experimental and scientific procedures [4].

All original data generated during the conduct of the study, including raw data and the final report, are stored in the archives of Eurofins Medical Device Testing Munich GmbH (Robert-Koch-Str. 3a, 82152 Planegg, Germany) for a period of 10 years.

2.16. Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluations were performed separately for each sex using Ascentos™ (version 1.3.4, Instem plc, Stone, UK). Normality and variance homogeneity were tested before selecting the appropriate test. Parametric data were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test; non-parametric data by Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn’s test. Outliers were excluded according to predefined criteria. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Sex was included as a factor in a two-way ANOVA to test for sex × dose interactions in body weight and clinical parameters. No significant sex-related effects were detected (p > 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Mortality

To determine whether CAVACURMIN® induces mortality or moribund conditions at the tested dose levels, mortality was monitored throughout the 28-day study. Four groups were evaluated: C1 (vehicle), C2 (CAVAMAX® W8 at 2555 mg/kg bw/day), LD (2000 mg/kg bw/day CAVACURMIN® = 366 mg/kg bw/day curcuminoids), and HD (3500 mg/kg bw/day CAVACURMIN® = 640.5 mg/kg bw/day curcuminoids) administered twice daily via oral gavage.

All animals survived to scheduled sacrifice except one female in the LD group (Animal No. 34), which was euthanised in a moribund state on Day 8. Clinical signs in this animal included abnormal breathing, hunched posture, half-closed eyelids, reduced spontaneous activity, slow movement, and pronounced piloerection. These signs first appeared on Day 8. Macroscopic necropsy revealed a thoracic cavity filled with brown, pasty fluid, and adhesions between the heart, lungs, and thymus.

Although no histopathology was performed, the presence of fluid—presumably the test item—in the thoracic cavity could suggest a test item-related incident. However, given the isolated occurrence, lack of similar findings in the HD group, and absence of supportive histopathological data, the death was considered incidental and likely due to a pre-existing congenital defect or a gavage error. All other animals showed no abnormalities across any organ system (see Supplementary Materials S1).

3.2. Clinical Observations

To determine whether administration of the test items results in observable clinical signs indicative of systemic or local toxicity, daily clinical observations were conducted. No systemic toxicity was observed in this study.

3.3. Local Tolerance

3.3.1. Local Toxicity

Minor local reactions were observed in control animals: one male in the C1 group (Animal No. 2) presented with a superficial head scratch, and one male in the C2 group (No. 10) exhibited transient clinical signs—abnormal breathing, wasp waist, hunched posture, half eyelid closure, and mild-to-moderate piloerection—which resolved within 3 days. These findings were considered incidental.

In contrast, local signs post-dosing were common in the curcumin-treated groups and appeared to be related to the test item:

- -

- LD group: Increased salivation was observed in 2/5 males and 1/5 females. Bedding displacement was noted in 3/5 males and 1/5 females.

- -

- HD group: Increased salivation occurred in all males (5/5) and 3/5 females. Bedding displacement was observed in all animals (5/5 males and 5/5 females).

These signs appeared immediately after gavage and were transient, indicating a local irritant or sensory effect of CAVACURMIN® rather than systemic toxicity.

3.3.2. Clinical Signs in Female and Male Animals

Throughout the 28-day observation period, the incidence of clinical signs increased with dose level, with no signs observed in the C2 control group and only a single minor event (a superficial scratch) noted in 1/5 animals (20%) in the C1 control group. In the low-dose CAVACURMIN® (LD) group, 2/5 females (40%) exhibited clinical signs, while all animals (5/5, 100%) in the high-dose (HD) CAVACURMIN® group were affected.

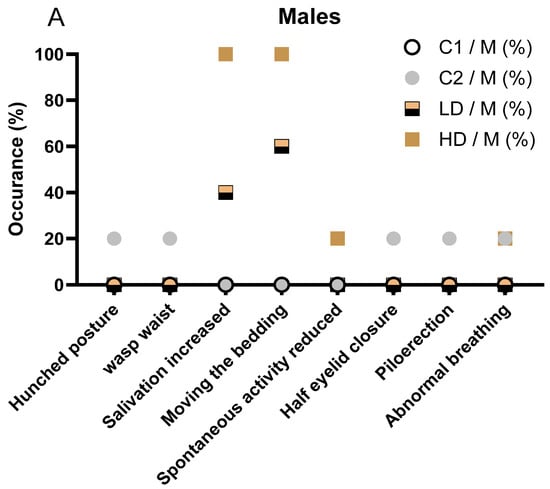

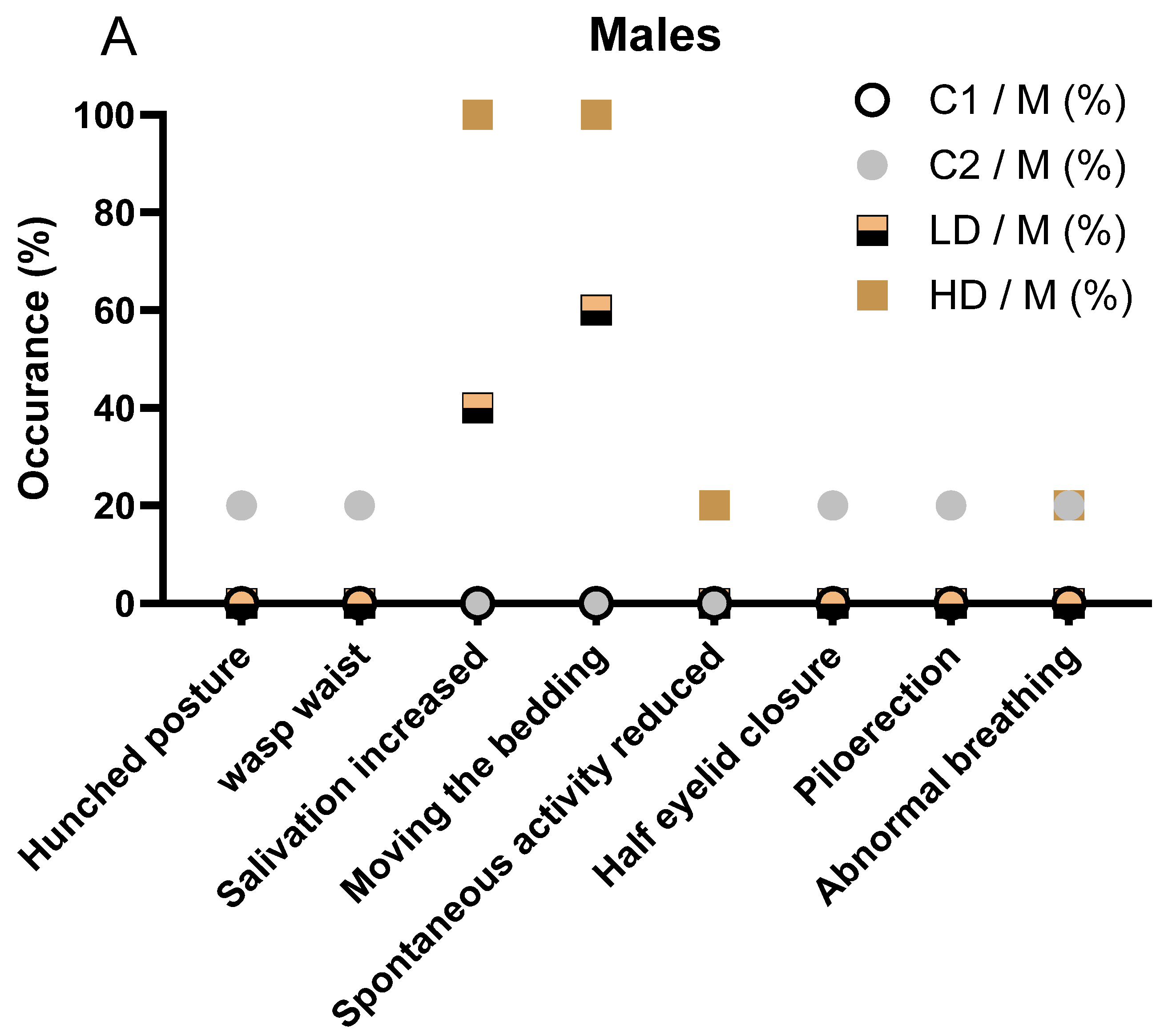

In detail, in male animals, the incidence and severity of clinical signs increased with dose level. No clinical signs were observed in the C1 control group. One animal (1/5, 20%) in the C2 control group displayed multiple transient signs, including hunched posture, wasp waist, half eyelid closure, piloerection, and abnormal breathing. These signs were short-lived and considered unrelated to treatment. In the low-dose CAVACURMIN® (LD) group, 3 out of 5 males (60%) exhibited clinical signs. Most prominent were signs related to local irritation, aversion behaviour, or activity stimulation, including increased bedding-moving behaviour (3/5, 60%) and increased salivation (2/5, 40%), both observed shortly after administration and resolving spontaneously (Figure 1A).

All animals in the male high-dose (HD) CAVACURMIN® group (5/5, 100%) displayed clinical signs. The most frequent were increased salivation (100%), bedding-moving behaviour (100%), and activity stimulation-related signs. One male also showed slightly reduced spontaneous activity and abnormal breathing, suggesting mild transient effects (Figure 1A).

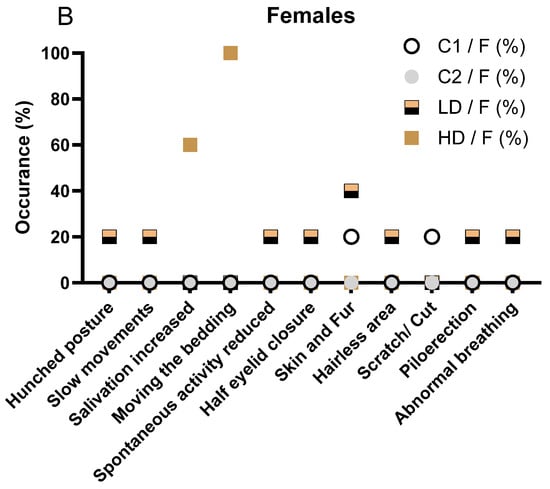

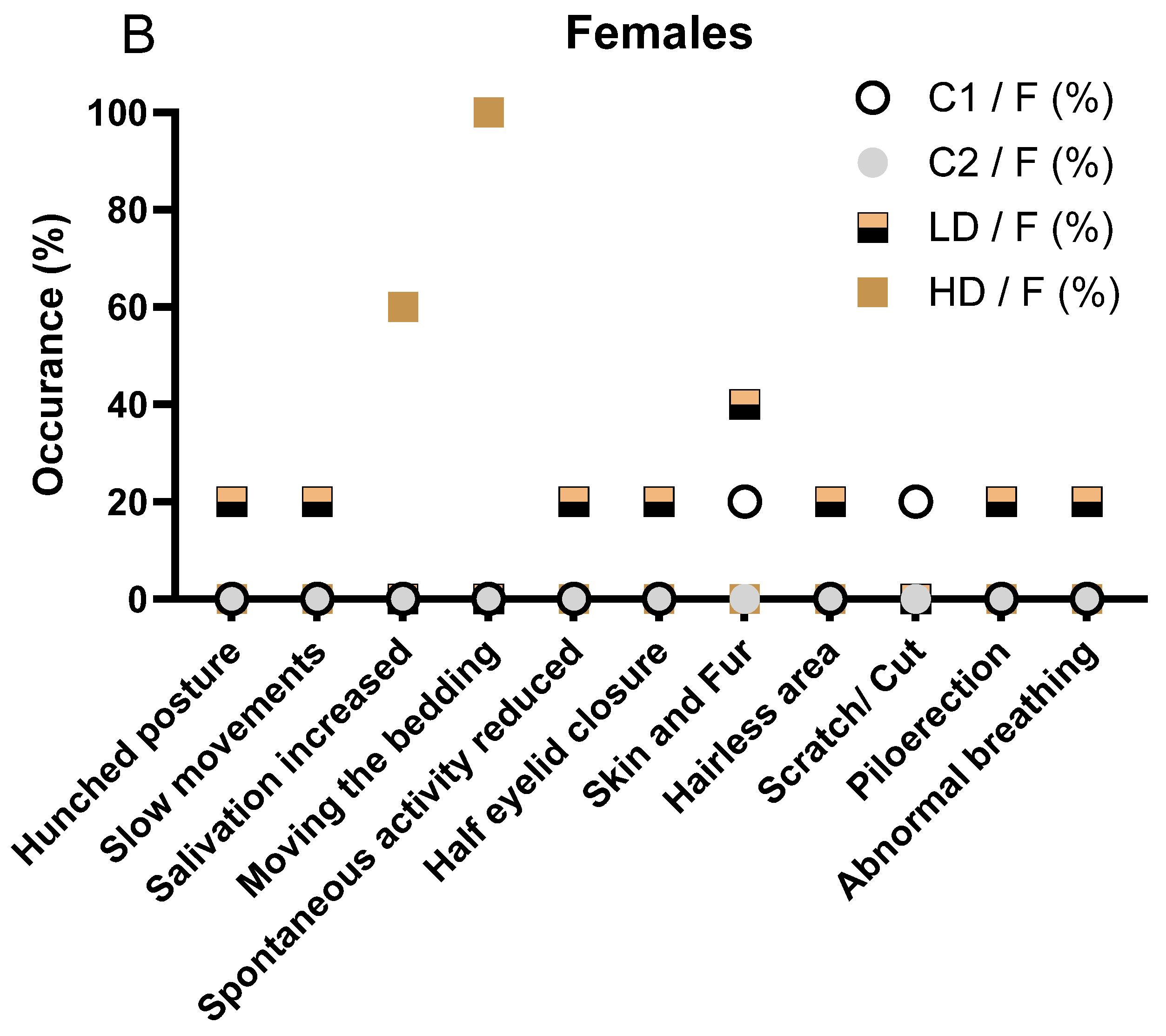

Signs observed in the female LD group included hunched posture, slow movements, reduced spontaneous activity, piloerection, half eyelid closure, and minor skin alterations (hairless area). These events were infrequent and isolated to individual animals (Figure 1B). The females in the HD group predominantly exhibited increased salivation (3/5, 60%) and bedding-moving behaviour (5/5, 100%), both occurring shortly after dosing. These findings are consistent with a local irritant response to the test item. Importantly, no systemic toxicity-related signs, such as hunched posture or reduced activity, were recorded in this group (Figure 1B).

No animals in any group displayed musculoskeletal or pulmonary abnormalities beyond the isolated cases in the LD group. The absence of clinical signs in the C2 group supports the interpretation that the observed signs in the treated groups are test item-related and dose-dependent but largely limited to local reactions rather than systemic toxicity.

The observed salivation and bedding-moving behaviour in both LD and HD groups were immediate post-dose events, likely reflecting a local or sensory irritant effect of curcumin, rather than systemic toxicity. No musculoskeletal, dermatological, or ocular signs were observed in treated animals, and isolated signs such as reduced spontaneous activity or abnormal breathing were rare and not dose dependent. Overall, the pattern in male animals mirrors that seen in females, with a clear dose-dependent increase in non-systemic, transient clinical signs suggestive of local irritation. The detailed description of all clinical observations is also available in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 1.

Clinical signs observed in male (A) and female (B) rats during the 28-day treatment period. (A) Incidence of clinical signs in male animals, stratified by treatment group (C1: vehicle; C2: CAVAMAX® W8 at 2555 mg/kg bw/day), a low CAVACURMIN® dose (LD: 2000 mg/kg bw/day), and a high CAVACURMIN® dose (HD: 3500 mg/kg bw/day) group. Doses were administered twice daily (2 × 10 mL/kg bw) for 28 consecutive days (Table 1). (B) Equivalent data for female animals. Signs included increased salivation, bedding-moving behaviour, piloerection, hunched posture, and abnormal breathing. Data reflect non-systemic, transient signs consistent with local irritant effects of the test item.

Figure 1.

Clinical signs observed in male (A) and female (B) rats during the 28-day treatment period. (A) Incidence of clinical signs in male animals, stratified by treatment group (C1: vehicle; C2: CAVAMAX® W8 at 2555 mg/kg bw/day), a low CAVACURMIN® dose (LD: 2000 mg/kg bw/day), and a high CAVACURMIN® dose (HD: 3500 mg/kg bw/day) group. Doses were administered twice daily (2 × 10 mL/kg bw) for 28 consecutive days (Table 1). (B) Equivalent data for female animals. Signs included increased salivation, bedding-moving behaviour, piloerection, hunched posture, and abnormal breathing. Data reflect non-systemic, transient signs consistent with local irritant effects of the test item.

Table 1.

Haematological Parameters in male and female Rats on Day 29 Following 28-Day Repeated Oral Dosing of CAVACURMIN®. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5 per sex per group). No statistically significant differences were observed between the treated and control groups. C1 = vehicle control (0.5% CMC); C2 = placebo control (CAVAMAX® W8 alone); LD = CAVACURMIN® low dose; HD = CAVACURMIN® high dose. WBC = white blood cell count; RBC = red blood cell count; HGB = haemoglobin concentration; HCT = haematocrit; PLT = platelet count.

Table 1.

Haematological Parameters in male and female Rats on Day 29 Following 28-Day Repeated Oral Dosing of CAVACURMIN®. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 5 per sex per group). No statistically significant differences were observed between the treated and control groups. C1 = vehicle control (0.5% CMC); C2 = placebo control (CAVAMAX® W8 alone); LD = CAVACURMIN® low dose; HD = CAVACURMIN® high dose. WBC = white blood cell count; RBC = red blood cell count; HGB = haemoglobin concentration; HCT = haematocrit; PLT = platelet count.

| Male Rats | |||||

| Group | WBC [109/L] | RBC [1012/L] | HGB [g/dL] | HCT [%] | PLT [109/L] |

| C1/M | 5.29 ± 1.34 | 9.12 ± 0.34 | 16.54 ± 0.78 | 48.68 ± 1.64 | 925.80 ± 85.79 |

| C2/M | 5.22 ± 1.40 | 9.10 ± 0.55 | 16.36 ± 0.60 | 48.06 ± 1.89 | 855.60 ± 77.70 |

| LD/M | 5.78 ± 1.63 | 8.66 ± 0.25 | 15.98 ± 0.23 | 46.38 ± 1.10 | 924.60 ± 126.39 |

| HD/M | 6.73 ± 1.74 | 8.55 ± 0.49 | 15.80 ± 1.18 | 46.70 ± 1.66 | 915.00 ± 137.89 |

| Female Rats | |||||

| Group | WBC [109/L] | RBC [1012/L] | HGB [g/dL] | HCT [%] | PLT [109/L] |

| C1/F | 2.90 ± 0.70 | 8.30 ± 0.40 | 15.50 ± 0.60 | 44.80 ± 1.90 | 933.80 ± 102.00 |

| C2/F | 4.30 ± 0.80 | 8.50 ± 0.30 | 15.40 ± 0.50 | 45.50 ± 1.50 | 867.80 ± 176.50 |

| LD/F | 5.30 ± 2.10 | 8.20 ± 0.50 | 15.60 ± 0.60 | 45.60 ± 2.20 | 970.80 ± 81.10 |

| HD/F | 4.80 ± 1.60 | 8.10 ± 0.20 | 15.30 ± 0.60 | 45.50 ± 1.60 | 1068.00 ± 94.90 |

3.4. Systemic Toxicity and Observations

3.4.1. Body Weight

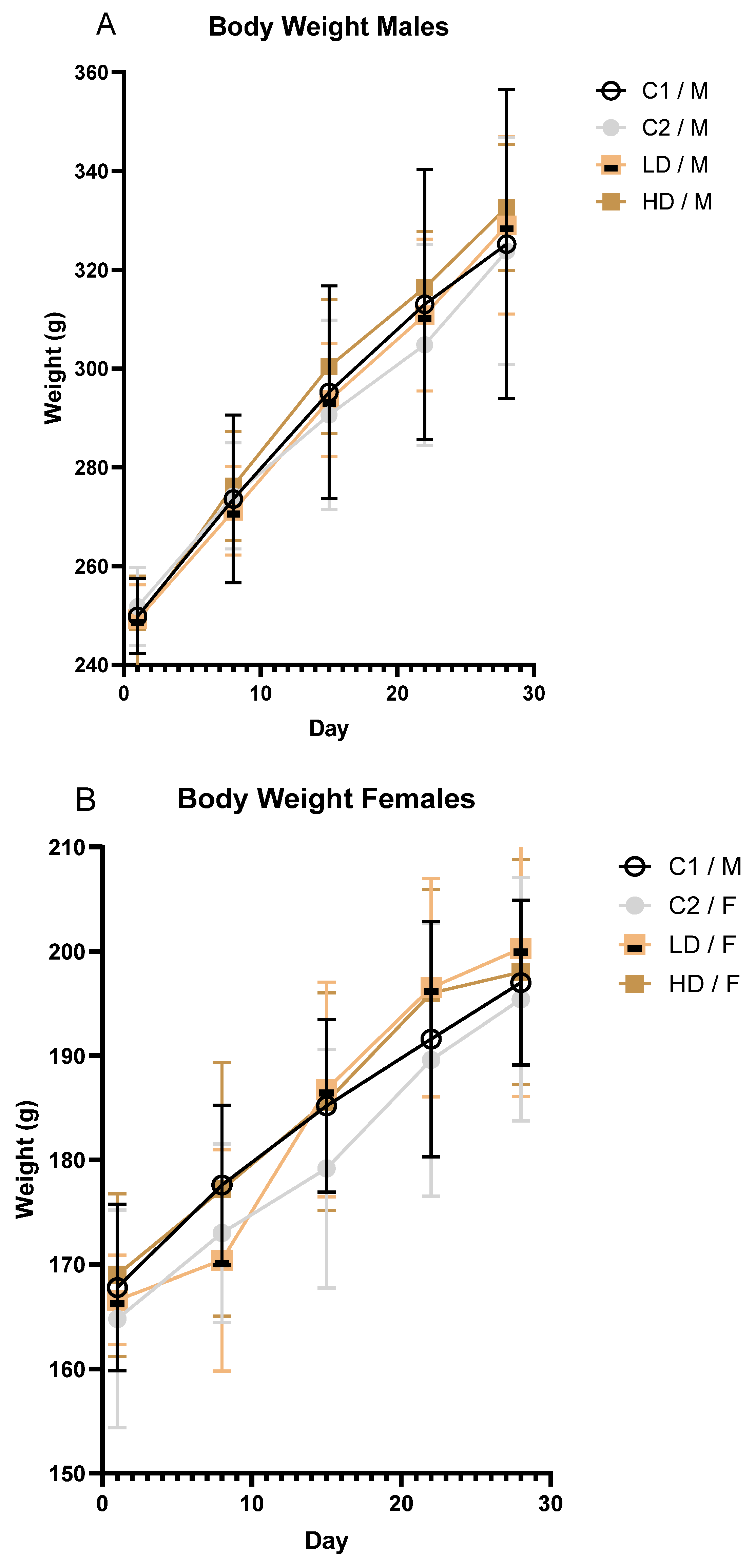

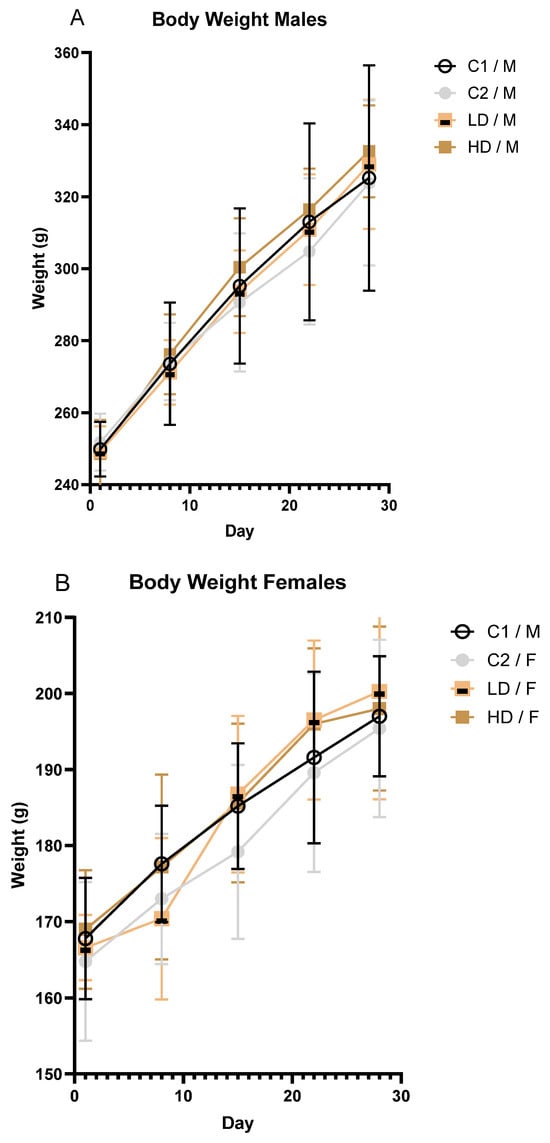

To investigate whether and how the exposure to the test item affects body weight over time in male and female rodents, body weights were recorded at regular intervals. Mean body weight increased steadily across all groups during the study. No toxicologically significant differences were observed between treated and control animals of either sex (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Body weight progression in male (A) and female (B) rats over the 28-day treatment period. Mean body weight (± SD) of male (A) and female (B) rats by treatment group over time.

3.4.2. Food Consumption

To assess whether the test item influences feeding behaviour or food intake during the observation period, mean daily food consumption was recorded and compared in one animal of each group. Food consumption was not affected by the test item. Average daily intake in treated animals (both sexes) was comparable to that of controls throughout the study (Supplementary Table S3).

3.4.3. Haematology

To determine whether the test item affects haematological parameters in a dose-dependent manner, standard haematology analyses were performed at the end of the treatment period.

No statistically significant differences were observed in any haematological parameters in male animals. For WBCs, despite the large effect size in both sexes, the difference was not significantly different due to the large variability among the animals. In females, a dose-dependent but statistically non-significant increase in platelet count (PLT) was observed (LD: +4%; HD: +14% vs. control C1). Two HD females had values above the historical control range. Although potentially test item-related, the low magnitude of the change and lack of statistical significance indicated no toxicological relevance.

3.4.4. Clinical Biochemistry (Blood Biomarkers)

To evaluate potential organ-specific toxicological effects, a panel of standard serum biochemistry parameters in blood was assessed on Day 29. These parameters provide insight into the functional status of key organs, particularly the liver and kidneys. The presence of alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) and aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) in blood serves as a sensitive indicator of hepatocellular injury, while alkaline phosphatase (AP) is associated with cholestatic liver damage and bone turnover. Creatinine (Crea) and urea are widely used markers of renal function, reflecting glomerular filtration and nitrogen metabolism, respectively. Total protein (TP) and albumin (ALB) offer additional information on nutritional and hepatic synthetic status, as well as systemic inflammation.

The measured values for each group, along with their standard deviations and percentage deviation from control, are summarised below and in Supplementary Table S4.

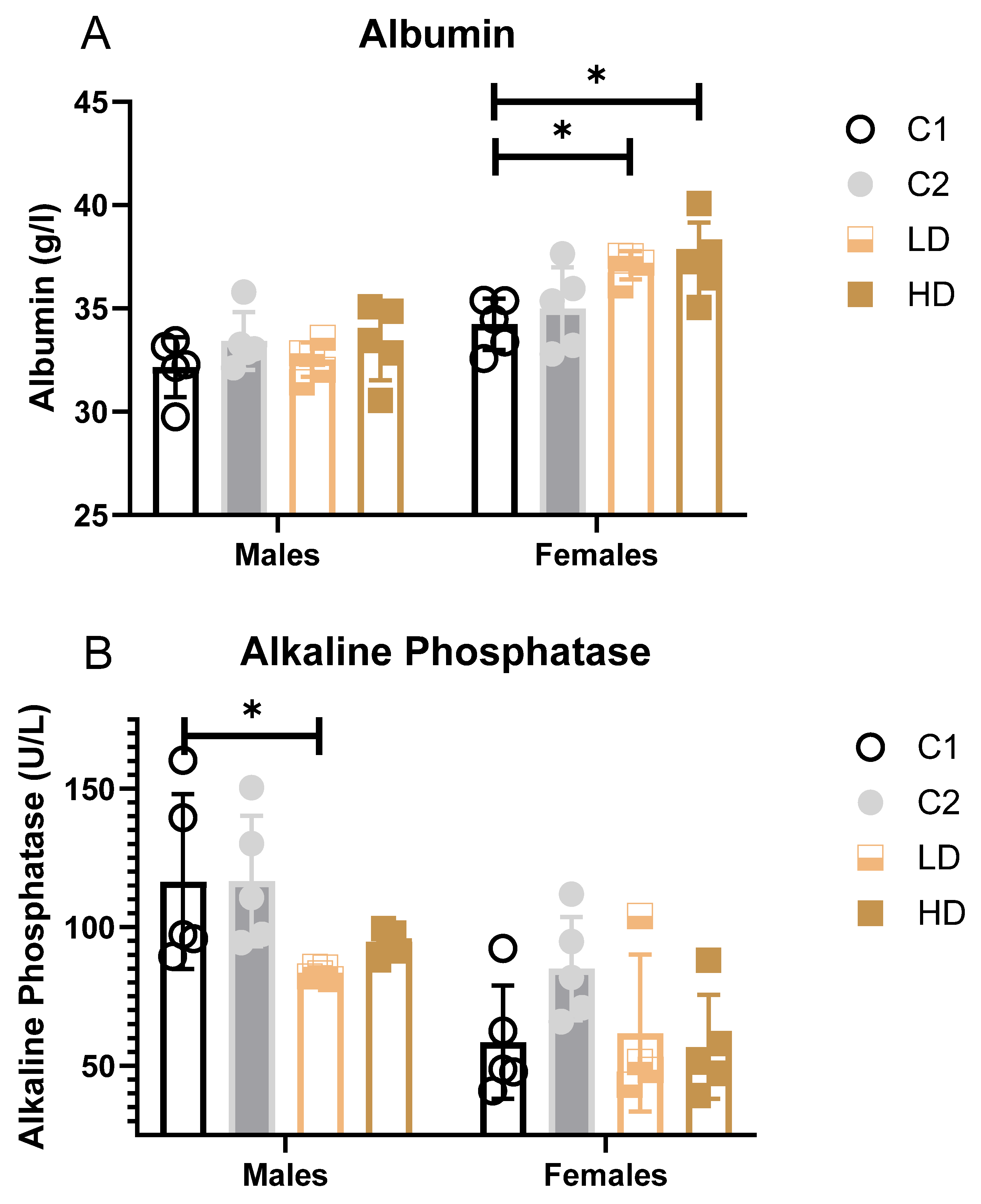

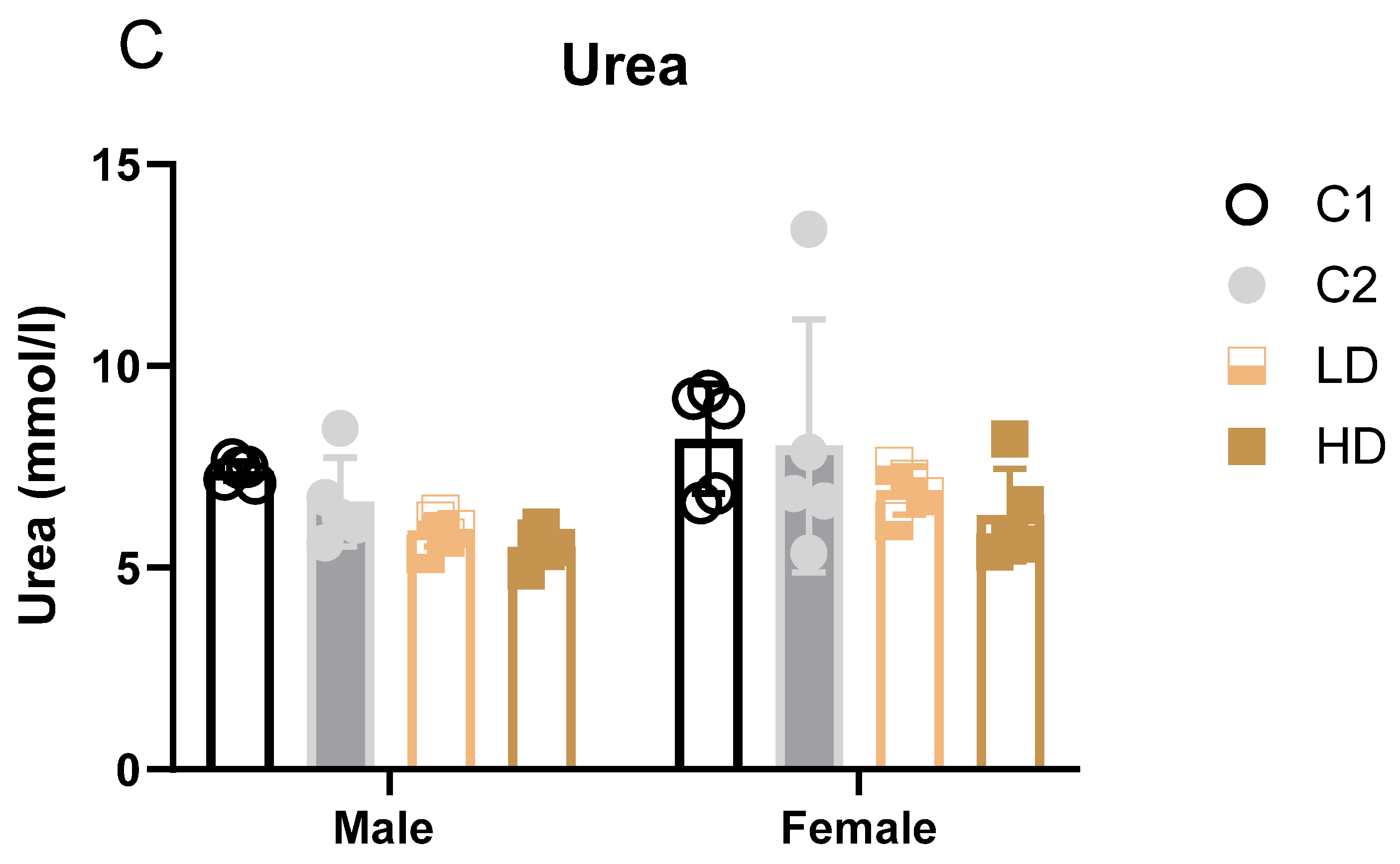

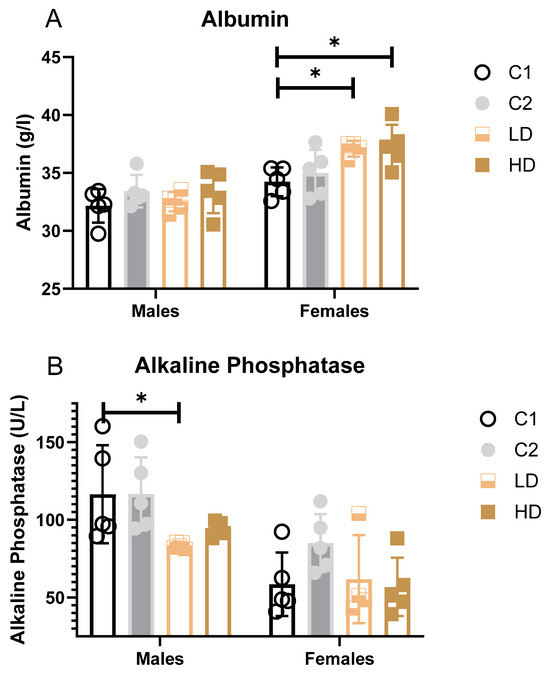

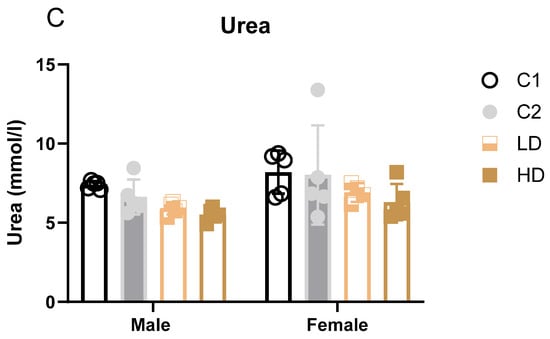

Parameters that showed statistically significant differences between groups (blood albumin, alkaline phosphatase, and urea) are additionally illustrated as bar graphs to facilitate visual comparison.

Liver markers: ALAT decreased significantly in C2 and LD and showed a trend across groups, suggesting a degree of hepatoprotection rather than injury. Albumin increased in females of both dose groups (LD: +8%; HD: +9% vs. control C1). While some values exceeded the historical control range, the change was not considered toxicologically significant (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Serum clinical biochemistry parameters with significant group differences. Bar graphs showing group means (± SD) for (A) serum albumin, (B) alkaline phosphatase, and (C) urea in rats on Day 29. Statistically significant differences from the C1 control group are indicated. * p < 0.05 vs. vehicle control (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett post-test).

Alkaline Phosphatase (AP): A statistically significant decrease was observed in LD males (−28% vs. C1); however, all individual values remained within the historical range (Figure 3B).

Renal markers: Males showed statistically significant decreases in both dose groups (LD: −20%; HD: −25%). One HD male value was below the historical range. Females showed a non-significant trend toward decreased urea levels (LD: −16%; HD: −23%). All individual values remained within historical limits, except for one animal in group C2 (considered incidental) (Figure 3C). Creatinine remained unchanged. The dose-dependent reduction in blood urea, in the absence of creatinine changes or renal pathology, may indicate physiological variation within normal adaptive limits.

Proteins: Total protein was relatively stable, with no concern for protein loss or synthesis impairment. For all other evaluated parameters not specifically mentioned, no sex-related differences were observed.

All values were compared with the BSL historical control range for Wistar rats (2018–2023). Observed variations for urea, albumin, ALT, and liver weights remained within these physiological limits.

A structured summary and interpretation of all clinical biochemical parameters measured on Day 29 (mean ± SD, n = 5 per group), with statistical annotations and percentage deviations vs. control, is available as Supplementary Table S4.

3.5. Organ Weight and Pathology

3.5.1. Liver Weight

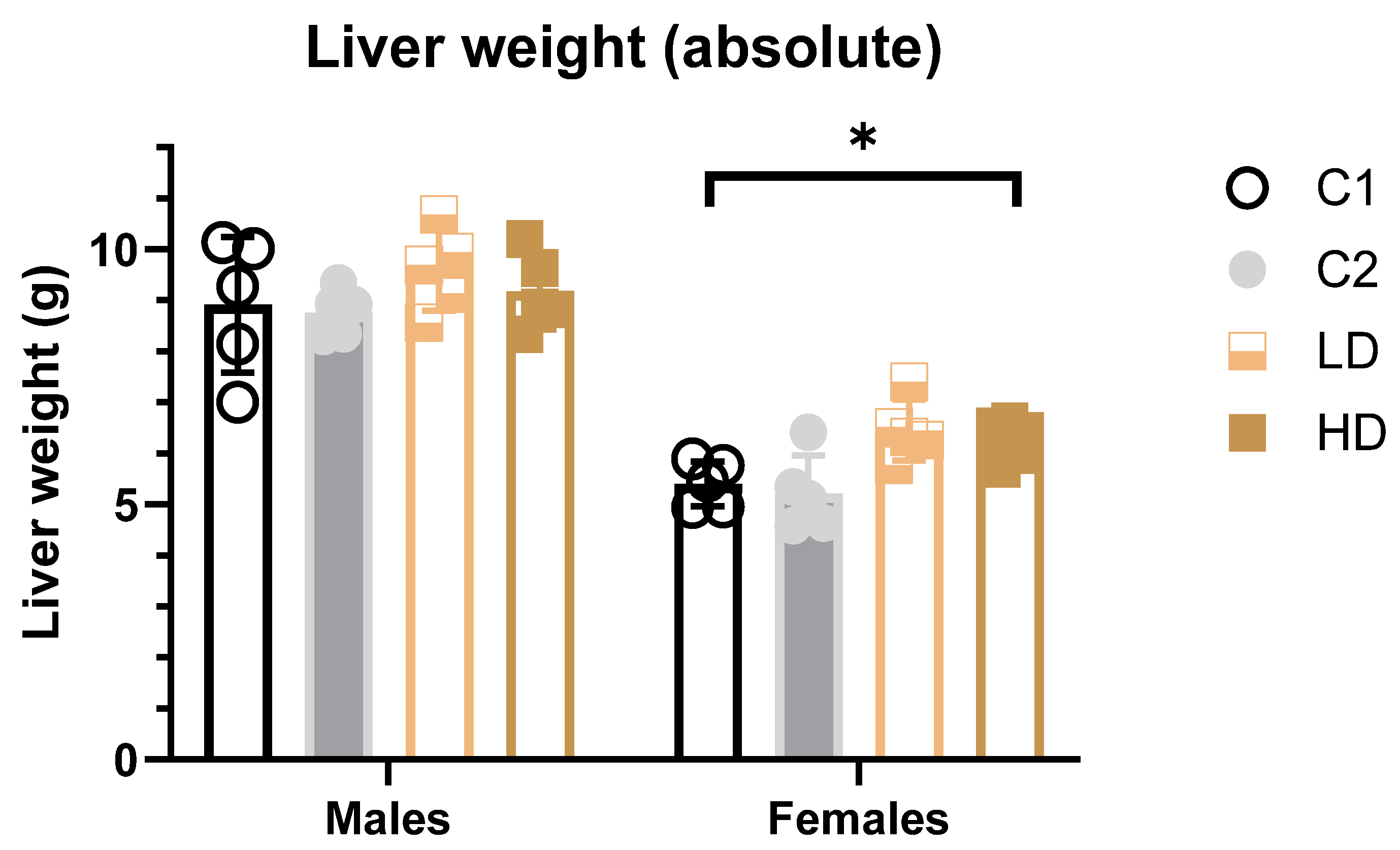

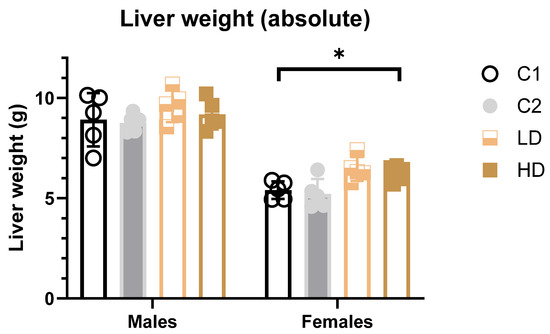

To determine whether the test item alters absolute or relative liver weights, they were recorded and analysed.

Absolute weight: In female HD animals, a significant increase (~14% vs. control C1) in both absolute and relative liver weights was detected. A similar but non-significant increase was noted in the LD group. All values remained within the historical control range, and no such effect was seen in the C2 control group, suggesting the finding may be test item-related but not toxicologically relevant (Figure 4). In male animals, no statistically significant differences in liver weights were observed in animals across dose groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Liver weights (absolute) in male and female rats at study termination. Mean absolute liver weights for female and male rats across all treatment groups. A statistically significant increase in absolute liver weights was observed in HD females (~14% vs. C1 control). No significant effects were observed in males. * p < 0.05 vs. vehicle control (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett post-test).

Relative weight: The results of the multiple comparisons (Tukey HSD) against the C1 control group, for both males and females did not show statistically significant differences in liver weight ratio compared to C1 (Supplementary Table S5).

3.5.2. Organ Pathology

To identify whether the test item induces any gross pathological changes in major organs or tissues, macroscopic evaluations were conducted at necropsy.

Males (C1/M, C2/M, LD/M, HD/M): No macroscopic abnormalities were observed in any of the 20 male rats across all dose groups. All examined organs and tissues—including the brain, spinal cord, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, lymphatic tissues, and reproductive organs—were normal in appearance.

Females (C1/F, C2/F, LD/F, HD/F): Most female animals (19/20) showed no macroscopic abnormalities, including in the gastrointestinal, urogenital, or nervous system tissues of females.

In summary, no gross pathological abnormalities were detected in any animals that survived to their scheduled sacrifice, in either the treated or control groups (Supplementary Table S1).

4. Discussion

This 28-day oral toxicity study demonstrates that CAVACURMIN®, a γ-cyclodextrin-complexed curcumin formulation with markedly enhanced bioavailability, was well tolerated in male and female Wistar rats at daily doses up to 3500 mg/kg. No systemic toxicity, adverse effects on survival, or meaningful changes in body weight, food intake, haematology, or gross pathology were observed.

Histopathological evaluation was intentionally excluded, consistent with OECD 408 dose-range-finding guidance, which emphasises clinical observations, organ weights, and serum biochemistry to identify target organs and appropriate dose levels before conducting full 90-day chronic studies. This approach prevents unnecessary animal use while still enabling reliable assessment of systemic tolerance.

The main clinical findings—transient salivation and bedding displacement—were dose-dependent, appeared immediately after gavage, and resolved spontaneously within minutes. These signs are consistent with local sensory or irritant effects rather than systemic toxicity, a pattern reported previously for nanoparticle and micellar curcumin preparations.

A small increase in absolute liver weight (~14%) was observed in high-dose females. However, values remained within historical control ranges and were not accompanied by elevated liver enzymes or pathological changes.

Similar liver weight increases were reported for conventional (low bioavailability) curcumin formulations, which, in general, have also yielded neutral toxicological profiles.

A two-generation reproductive study at high dietary doses (10,000–15,000 ppm) has reported similar small increases in liver weight [16]. A further study with rats and mice reported similar results [24]. In these cases, liver weights generally remained within historical control ranges, were not accompanied by hepatocellular injury or significant enzyme elevations, and were therefore interpreted as adaptive changes (likely reflecting hepatocellular hypertrophy or metabolic enzyme induction) rather than adverse toxicological effects [16,24]. The modest increase in serum albumin observed in CAVACURMIN®-treated females, in the absence of liver pathology or enzyme elevations, may also reflect adaptive variation in protein metabolism and is not considered toxicologically relevant. Similarly, the modest decrease in alkaline phosphatase, observed without accompanying pathology or liver enzyme elevations, reflects normal inter-individual variability in hepatic or bone metabolism. The dose-dependent reduction in blood urea, in the absence of creatinine changes or renal pathology, may reflect a shift in nitrogen metabolism without evidence of renal impairment. For all other evaluated parameters not specifically mentioned, no sex-related differences were observed.

Serum biochemistry changes included a dose-dependent reduction in urea levels in male rats and a modest, statistically significant increase in serum albumin in females. Both parameters remained within historical control ranges and were not associated with clinical signs or pathological findings, rendering them of uncertain toxicological significance.

These biochemical trends likely represent physiological modulation within the normal adaptive range and were not accompanied by histopathological or clinical evidence of toxicity.

Interestingly, a similar biochemical profile was previously observed in a 90-day curcumin-piperine study, where decreased urea and increased albumin were attributed to enhanced nitrogen retention and mild anti-inflammatory modulation.

Haematological evaluations revealed a non-significant trend toward increased platelet counts (PLTs) in LD and HD females. In contrast, no meaningful changes in haematology were observed in male animals.

Importantly, there were no CAVACURMIN®-related effects on mortality, systemic clinical signs, body weight, food consumption, or gross pathology. The absence of relevant differences between the two control groups (vehicle vs. γ-cyclodextrin) further suggests that the carrier substance does not contribute to any observed effects, supporting the use of a single control group in future studies.

As this was a dose-range-finding study, the relatively small group size, limited 28-day duration, and omission of histopathology were intentional design features; while these constrain definitive long-term conclusions, they are appropriate for establishing suitable dose levels for subsequent chronic studies.

Overall, these results align with previous preclinical work showing that curcumin—whether in conventional or enhanced-bioavailability form—has a wide safety margin. The present study fulfils OECD 408 dose-range finding objectives and identifies 3500 mg/kg/day as an appropriate top dose for a subsequent 90-day toxicity study, which will include full histopathological evaluation to establish a definitive NOAEL for regulatory submissions.

5. Conclusions

This 28-day dose-range finding study in male and female Wistar rats demonstrated that CAVACURMIN® was well tolerated at daily doses of 2000 and 3500 mg/kg body weight. Statistically significant changes included a modest increase in serum albumin in low- and high-dose females, and a decrease in serum urea in low- and high-dose males. All values remained within historical control ranges and were unaccompanied by adverse clinical signs, organ pathology, or other indicators of systemic toxicity, suggesting these shifts are non-adverse and potentially reflect favourable physiological modulation.

No treatment-related effects were observed on mortality, overall clinical condition, body weight progression, food consumption, gross pathology, or organ weights in either sex. No meaningful differences were detected between the vehicle and γ-cyclodextrin control groups, indicating that a single control group may be sufficient in future studies.

Based on these findings, 3500 mg/kg body weight/day is an appropriate top dose for a subsequent OECD 408-compliant 90-day repeated-dose oral toxicity study. That investigation will incorporate full histopathological evaluation and expanded endpoints to establish a definitive No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) to support regulatory submissions and the continued clinical development of CAVACURMIN®.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010002/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and S.S.; Formal analysis, G.M. and S.S.; Investigation, N.L.R.; Validation, G.M.; Writing—original draft, H.Z. and G.M.; Writing—review and editing, H.Z., M.K. and G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the study was provided by Wacker Chemie AG, Gisela-Stein-Straße 1, 81671 München, Germany.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The following study, intended for publication, was notified to the Government of Upper Bavaria: 28-Day Dose Range Finding Oral Toxicity Study in Wistar Rats with CAVACURMIN®—2024, BSL Munich Study No.: 2200461. Reference number: ROB-55.2-2532.Vet_03-18-63. This study only required notification to the authority; no special approval was necessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

CAVACURMIN® is commercially available. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank BSL BIOSERVICE Scientific Laboratories Munich GmbH for conducting the biosafety testing and the report on which this publication is based.

Conflicts of Interest

M.K. and H.Z. are employees of Wacker Chemie AG, which holds the ownership of the brand name CAVACURMIN®. N.L.R and S.S are employees of the independent GLP contract laboratory BSL BIOSERVICE Scientific Laboratories Munich GmbH. where the study “28-Day Dose Range Finding Oral Toxicity Study in Wistar Rats with CAVACURMIN®–2024, BSL Munich Study No.: 2200461” has been conducted upon request of Wacker Chemie AG. The authors declare that this study received funding from Wacker Chemie AG. The funder commissioned and funded the study and made the decision to publish the results. Data collection, analysis, and interpretation were performed independently by the contract research organisation and the academic authors.

References

- Patil, B.S.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Chidambara Murthy, K.N.; Vikram, A. Bioactive compounds: Historical perspectives, opportunities, and challenges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8142–8160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venigalla, M.; Sonego, S.; Gyengesi, E.; Sharman, M.J.; Münch, G. Novel promising therapeutics against chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 95, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Asgarov, R.; Venigalla, M.; Liang, H.; Niedermayer, G.; Munch, G.; Gyengesi, E. Effects of a solid lipid curcumin particle formulation on chronic activation of microglia and astroglia in the GFAP-IL6 mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venigalla, M.; Gyengesi, E.; Münch, G. Curcumin and Apigenin—Novel and promising therapeutics against chronic neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Kismali, G.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, a component of turmeric: From farm to pharmacy. BioFactors 2013, 39, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.B.; Yan, J.; Liang, H.P. The clinical applications of curcumin: Current state and the future. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2011–2031. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, R.; Lowery, R.P.; Calvanese, A.V.; Joy, J.M.; Purpura, M.; Wilson, J.M. Comparative absorption of curcumin formulations. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.H.; Huang, T.M.; Lin, J.K. Biotransformation of curcumin through reduction and glucuronidation in mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1999, 27, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabur, L.; Pandey, R.; Mikhael, M.; Niedermayer, G.; Gyengesi, E.; Mahns, D.; Munch, G. Pharmacokinetic Analysis of the Bioavailability of AQUATURM((R)), a Water-Soluble Curcumin Formulation, in Comparison to a Conventional Curcumin Tablet, in Human Subjects. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, T.; Makino, Y. Novel curcumin oral delivery systems. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 2807–2821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spitofsky, N.R.; Huang, A.A.; Jalalian, A.; Gallagher, S.; Fink, S. A Case of Turmeric-Induced Hepatotoxicity with Hyperferritinemia. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2025, 19, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, D.; Seyhan, M.F.; Aktoren, O. Cytotoxicity and Alkaline Phosphatase Activity of Curcumin, Aloin and MTA on Human Dental Pulp Cells. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2024, 35, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukavin, N.N.; Popov, A.L.; Anikina, V.A.; Vinnik, D.A.; Bokl, B.A.; Popova, N.R. Excess curcumin causes cytotoxicity of its nanoconjugate with nanoceria. Toxicol. Vitr. 2026, 110, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhaniya, P.; Patel, C.; Muchhara, J.; Bhadja, N.; Mathuria, N.; Vachhani, K.; Soni, M.G. Safety assessment of a solid lipid curcumin particle preparation: Acute and subchronic toxicity studies. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1834–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganiger, S.; Malleshappa, H.N.; Krishnappa, H.; Rajashekhar, G.; Ramakrishna Rao, V.; Sullivan, F. A two generation reproductive toxicity study with curcumin, turmeric yellow, in Wistar rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Hair, C.; Beswick, L. A rare case of turmeric-induced hepatotoxicity. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaizabal Azkue, I.J.; Castiella, A.; Aburruza Ucar, L.; Torrente Iranzo, S.; Zapata Morcillo, E. Turmeric associated liver injury (DILI) with susceptible HLA. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2024, 116, 650–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanese, G.; Agostini, E.; De Angelis, M.V.; Pretore, E.; Galosi, A.B.; Castellani, D. Efficacy of 1-Year Cavacurmin((R)) Therapy in Reducing Prostate Growth in Men Suffering from Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Schizas, N.; Kazazis, C. Potential anticancer properties and mechanisms of action of curcumin. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 645–651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Venigalla, M.; Raju, R.; Munch, G. Pharmacological considerations for treating neuroinflammation with curcumin in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2022, 129, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.; Liang, A.; Rangel, A.; Gyengesi, E.; Niedermayer, G.; Munch, G. High bioavailability curcumin: An anti-inflammatory and neurosupportive bioactive nutrient for neurodegenerative diseases characterized by chronic neuroinflammation. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Test No. 408: Repeated Dose 90-Day Oral Toxicity Study in Rodents; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Toxicology Program. Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Turmeric Oleoresin (Major Component 79–85% Curcumin) in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Feed Studies); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, NC, USA, 1993; pp. 1–275. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.