Toxicological Assessment and Potential Protective Effects of Brassica Macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract Against Copper Sulphate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Preparation of Plant Extract

2.2. Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test

2.3. Behavioural Analysis

2.4. CuSO4 Treatment on Zebrafish Embryo

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Evaluation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of B. macrocarpa Extract on Embryo Survival

3.2. Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test on Zebrafish

3.3. Locomotor Behaviour

3.4. Effect of 26 h Exposure to B. macrocarpa Extract on Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Larvae

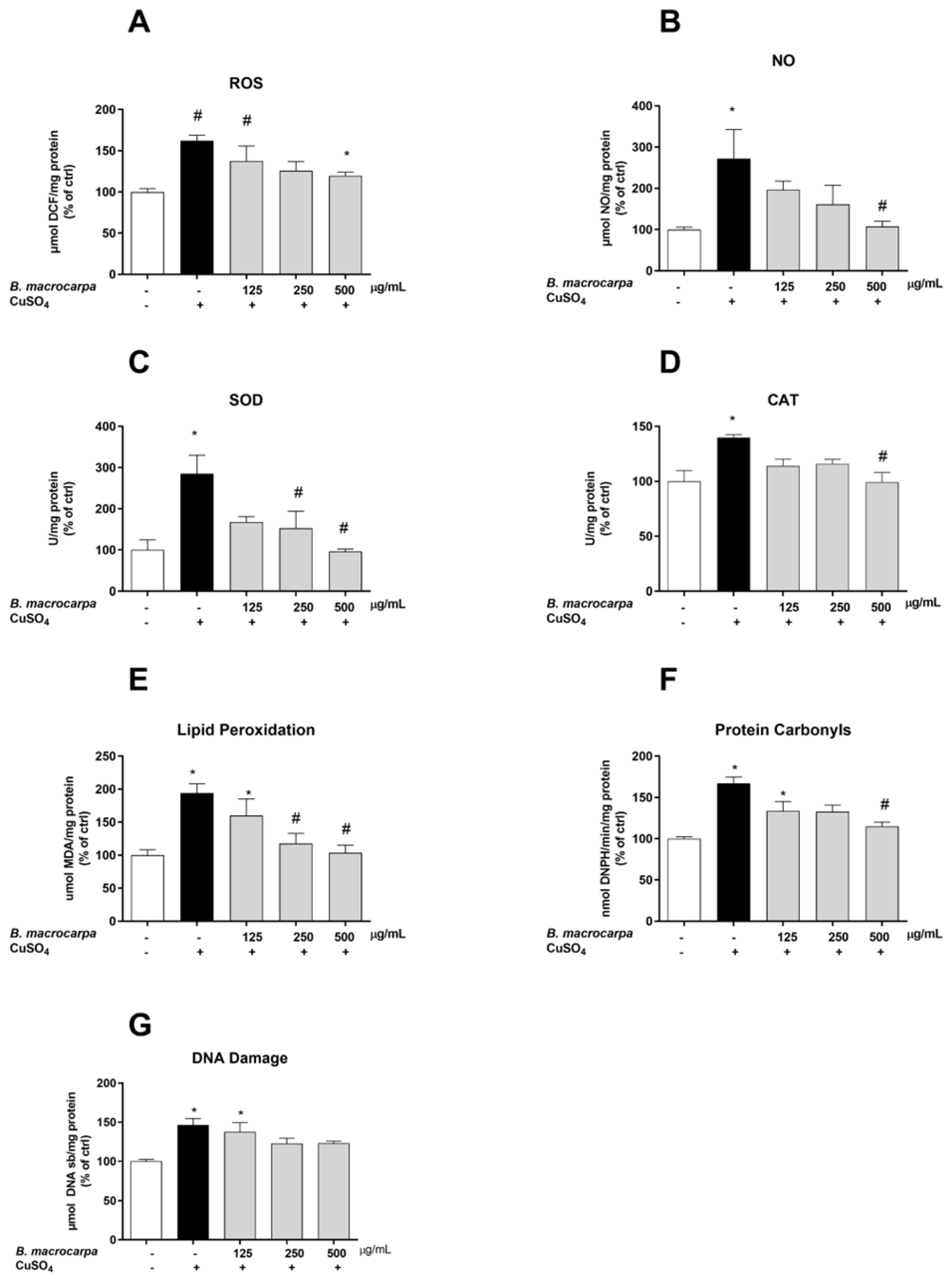

3.5. Antioxidant Effect of B. macrocarpa Extract on CuSO4-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Larvae

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAT | Catalase |

| CuSO4 | Copper Sulphate |

| Hpf | Hours Post-Fertilization |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| OECD | Organization For Economic Cooperation and Development |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

References

- Ahmed, A.U. An Overview of Inflammation: Mechanism and Consequences. Front. Biol. 2011, 6, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and Physiological Roles of Inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugrin, J.; Rosenblatt-Velin, N.; Parapanov, R.; Liaudet, L. The Role of Oxidative Stress during Inflammatory Processes. Biol. Chem. 2014, 395, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, T.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y.; Blachier, F.; Tossou, M.C.B.; Rahu, N. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 7432797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Disease; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780128032701. [Google Scholar]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Rani, R.; Ganie, S.Y.; Sheikh, T.A.; Javaid, D.; Qadri, S.S.; Pramodh, S.; Alsulimani, A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Harakeh, S.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wu, N.; Xu, M.; Du, H.; Wu, J.; Tu, Y. Antioxidant Stress and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Egg White Proteins and Their Derived Peptides: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and Organ Damage: A Current Perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, F.; Astegiano, M.; Maina, M.; Leonarduzzi, G.; Poli, G. Polyphenol Supplementation as a Complementary Medicinal Approach to Treating Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4851–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicio, A.; Sut, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Bruno, M.; Luparello, C.; Serio, R.; Zizzo, M.G. Chemical Characterization and Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activity Evaluation of the Ethanol Extract from the Bulbs of Pancratium maritimun Collected in Sicily. Molecules 2023, 28, 3986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocariu, R.O.; Balmus, I.M.; Lefter, R.; Hritcu, L.; Ababei, D.C.; Ciobica, A.; Copaci, S.; Mot, S.E.L.; Copolovici, L.; Copolovici, D.M.; et al. Camelina Sativa Methanolic and Ethanolic Extract Potential in Alleviating Oxidative Stress, Memory Deficits, and Affective Impairments in Stress Exposure-Based Irritable Bowel Syndrome Mouse Models. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 9510305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattosinhos, P.d.S.; Sarandy, M.M.; Novaes, R.D.; Esposito, D.; Gonçalves, R.V. Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Skin Regenerative Potential of Secondary Metabolites from Plants of the Brassicaceae Family: A Systematic Review of In vitro and In vivo Preclinical Evidence (Biological Activities Brassicaceae Skin Diseases). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Segaran, G.; Sundar, R.D.V.; Settu, S.; Sathiavelu, M. Brassicaceae—A Classical Review on Its Pharmacological Activities. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2019, 55, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cicio, A.; Serio, R.; Zizzo, M.G. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Brassicaceae-Derived Phytochemicals: In vitro and In vivo Evidence for a Putative Role in the Prevention and Treatment of IBD. Nutrients 2023, 15, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokayya, S.; Li, C.J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, C.H. Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. Capitata) Phytochemicals with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 6657–6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicio, A.; Aloi, N.; Sut, S.; Longo, V.; Terracina, F.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Zizzo, M.G.; Bruno, M.; Ilardi, V.; Colombo, P.; et al. Chemical Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging, and Cellular Antioxidant Properties of the Egadi Island Endemic Brassica macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, C.A.; Peterson, R.T. Zebrafish as Tools for Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zon, L.I.; Peterson, R.T. In vivo Drug Discovery in the Zebrafish. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belo, M.A.A.; Oliveira, M.F.; Oliveira, S.L.; Aracati, M.F.; Rodrigues, L.F.; Costa, C.C.; Conde, G.; Gomes, J.M.M.; Prata, M.N.L.; Barra, A.; et al. Zebrafish as a Model to Study Inflammation: A Tool for Drug Discovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 144, 112310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, C.; Boix, N.; Teixido, E.; Marizande, F.; Cadena, S.; Bustillos, A. The Zebrafish Embryo as a Model to Test Protective Effects of Food Antioxidant Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, C.D.; Jayawardena, U.A. Toxicity Assessment of Herbal Medicine Using Zebrafish Embryos: A Systematic Review. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 7272808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forn-Cuní, G.; Varela, M.; Pereiro, P.; Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. Conserved Gene Regulation during Acute Inflammation between Zebrafish and Mammals. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Shi, F.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Chu, J. Protective Effect of Surfactin on Copper Sulfate-Induced Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Hepatic Injury in Zebrafish. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 65, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzarin, G.A.B.; Félix, L.M.; Monteiro, S.M.; Ferreira, J.M.; Oliveira, P.A.; Venâncio, C. Anti-Inflammatory, Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Thymol and 24-Epibrassinolide in Zebrafish Larvae. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 11297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, J.R. Zebrafish: Development of a Vertebrate Model Organism. Curr. Protoc. Essent. Lab. Tech. 2018, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, D.J. Probit Analysis: A Statistical Treatment of the Sigmoid Response Curve, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, R.; Venâncio, C.A.S.; Félix, L.M. Toxic Effects of a Mancozeb-Containing Commercial Formulation at Environmental Relevant Concentrations on Zebrafish Embryonic Development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21174–21187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.M.; Antunes, L.M.; Coimbra, A.M.; Valentim, A.M. Behavioral Alterations of Zebrafish Larvae after Early Embryonic Exposure to Ketamine. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Le, H.D.; Nguyen Thi Kim, T.; Pham The, H.; Nguyen, T.M.; Cornet, V.; Lambert, J.; Kestemont, P. Anti–Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of the Ethanol Extract of Clerodendrum Cyrtophyllum Turcz in Copper Sulfate-induced Inflammation in Zebrafish. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, C.; Yu, K.; Shi, X.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Lam, P.K.S.; Wu, R.S.S.; Zhou, B. Hexabromocyclododecane-Induced Developmental Toxicity and Apoptosis in Zebrafish Embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2009, 93, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.M.; Vidal, A.M.; Serafim, C.; Valentim, A.M.; Antunes, L.M.; Monteiro, S.M.; Matos, M.; Coimbra, A.M. Ketamine Induction of P53-Dependent Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, L.M.; Vidal, A.M.; Serafim, C.; Valentim, A.M.; Antunes, L.M.; Campos, S.; Matos, M.; Monteiro, S.M.; Coimbra, A.M. Ketamine-Induced Oxidative Stress at Different Developmental Stages of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 61254–61266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, S.-Y.; Zheng, L. Sulforaphane Attenuates Ethanol-Induced Teratogenesis and Dysangiogenesis in Zebrafish Embryos. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kassie, F.; Mersch-Sundermann, V. Induction of Apoptosis in Tumor Cells by Naturally Occurring Sulfur-Containing Compounds. Mutat. Res./Rev. Mutat. Res. 2005, 589, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadir, N.H.A.; David, R.; Rossiter, J.T.; Gooderham, N.J. The Selective Cytotoxicity of the Alkenyl Glucosinolate Hydrolysis Products and Their Presence in Brassica Vegetables. Toxicology 2015, 334, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, X.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Q. Specific Nanotoxicity of Graphene Oxide during Zebrafish Embryogenesis. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, L.Y.; Golombek, S.K.; Mertens, M.E.; Pan, Y.; Laaf, D.; Broda, J.; Jayapaul, J.; Möckel, D.; Subr, V.; Hennink, W.E. In vivo Nanotoxicity Testing Using the Zebrafish Embryo Assay. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 3918–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobanska, M.; Scholz, S.; Nyman, A.M.; Cesnaitis, R.; Gutierrez Alonso, S.; Klüver, N.; Kühne, R.; Tyle, H.; de Knecht, J.; Dang, Z.; et al. Applicability of the Fish Embryo Acute Toxicity (FET) Test (OECD 236) in the Regulatory Context of Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.W.; Zang, C.R.; Li, Q.C.; Sun, B.; Mei, X.P.; Bai, L.; Shang, X.M.; Deng, Y.; Xiao, Y.Q.; Ghiladi, R.A.; et al. Hydrothermally Derived Green Carbon Dots from Broccoli Water Extracts: Decreased Toxicity, Enhanced Free-Radical Scavenging, and Anti-Inflammatory Performance. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, R.; Pelster, B.; Schwerte, T. How Does Blood Cell Concentration Modulate Cardiovascular Parameters in Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio)? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2007, 146, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Li, C.Q. Zebrafish: A Predictive Model for Assessing Drug-Induced Toxicity. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Mitra, S.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative Stress: An Essential Factor in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Mucosal Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Prather, E.R.; Stetskiv, M.; Garrison, D.E.; Meade, J.R.; Peace, T.I.; Zhou, T. Inflammaging and Oxidative Stress in Human Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Treatments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidinger, A.; Kozlov, A.V. Biological Activities of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: Oxidative Stress versus Signal Transduction. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Guru, A.; Sudhakaran, G.; Pachaiappan, R.; Mahboob, S.; Al-ghanim, K.A.; Al-misned, F.; Juliet, A.; Gobi, M.; Arokiaraj, J. Copper Sulfate Induced Toxicological Impact on In-Vivo Zebrafish Larval Model Protected Due to Acacetin via Anti-Inflammatory and Glutathione Redox Mechanism. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C 2022, 262, 109463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Cordeiro, M.L.; de Queiroz Aquino-Martins, V.G.; da Silva, A.P.; de Souza Paiva, W.; Silva, M.M.C.L.; Luchiari, A.C.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Scortecci, K.C. Bioactivity of Talisia Esculenta Extracts: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Action on RAW 264.7 Macrophages and Protective Potential on the Zebrafish Exposed to Oxidative Stress Inducers. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, P.; Xue, M.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Z.; Xu, C.; Fan, Y.; Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; Wu, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Rice Bran Oil Extract in Copper Sulfate-Induced Inflammation in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 136, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; D’Amato, A.; Karav, S.; Tripodi, G.; Aiello, G.; Baldelli, S.; Lombardo, M.; D’Amato, A.; Karav, S.; et al. Glucosinolates in Human Health: Metabolic Pathways, Bioavailability, and Potential in Chronic Disease Prevention. Foods 2025, 14, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, L.; Lv, Y.; Li, L.; Dong, Q. Sulforaphane Protects against Oxidative Stress-induced Apoptosis via Activating SIRT1 in Mouse Osteoarthritis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, F.; Maugeri, A.; Laurà, R.; Levanti, M.; Navarra, M.; Cirmi, S.; Germanà, A. Zebrafish as a Useful Model to Study Oxidative Stress-Linked Disorders: Focus on Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuno, A.; Benavente-Garcia, O.; Castillo, J.; Alcaraz, M.; Vicente, V.; Del Rio, J.A. Beneficial Action of Citrus Flavonoids on Multiple Cancer-Related Biological Pathways. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2007, 7, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, Dietary Sources, Metabolism, and Nutritional Significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Contaminant-Induced Oxidative Stress in Fish: A Mechanistic Approach. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 42, 711–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Mayo, J.C.; Sainz, R.M.; Antolín, I.; Herrera, F.; Martín, V.; Reiter, R.J. Regulation of Antioxidant Enzymes: A Significant Role for Melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2004, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Zhu, J.; Shen, C.; Cui, Y.; Du, J.; Chen, X. The Effects of Cobalt on the Development, Oxidative Stress, and Apoptosis in Zebrafish Embryos. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 150, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Development Parameters | 0 μg/mL. | 125 μg/mL. | 250 μg/mL. | 500 μg/mL. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malformations (%) | 10.00 ± 4.08 | 15. 00 ± 6.44 | 10.00 ± 5.77 | 10.00 ± 5.7 |

| Edema (%) | 10.28 ± 4.09 | 10.90 ± 4.12 | 15.27 ± 6.06 | 14.75 ± 2.64 |

| Size (mm) | 3.76 ± 0.05 | 3.78 ± 0.05 | 3.86 ± 0.06 | 3.74 ± 0.06 |

| Angle (°) | 157.17 ± 0.17 | 161.80 ± 1.17 | 160.32 ± 1.29 | 156.24 ± 1.11 |

| Head (mm2) | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| Eye (mm2) | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| Pericardium (mm2) | 0.11 ±0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| Yolk (mm2) | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| Behavioural Parameters | 0 μg/mL. | 125 μg/mL. | 250 μg/mL. | 500 μg/mL. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (cm) | 27.28 ± 945 | 28.51 ± 7.95 | 28.32 ± 10.92 | 17.52 ± 8.75 |

| Speed (mm/s) | 1.14 ± 0.36 | 1.13 ± 0.42 | 0.74 ± 0.15 | 0.71 ± 0.17 |

| Immobility time (%) | 46.56 ± 5.61 | 45.06 ± 4.92 | 40.51 ± 8.04 | 52.00 ± 8.89 |

| Centre distance (mm) | 7.84 ± 0.21 | 7.50 ± 0.17 | 6.64 ± 0.67 | 7.32 ± 0.28 |

| Absolute turn angle (°) | 4.23 ± 0.71 | 4.69 ± 0.46 | 3.93 ± 0.38 | 4.42 ± 0.63 |

| Time in the lit side (%) | 55.43 ± 4.79 | 66.24 ± 5.24 | 63.17 ± 5.53 | 50.13 ± 9.47 |

| Time in the non-stimulus side (%) | 66.77 ± 6.04 | 72.35 ± 8.82 | 53.40 ± 10.94 | 50.65 ± 5.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cicio, A.; Félix, L.M.; Monteiro, S.M.; Bruno, M.; Zizzo, M.G.; Serio, R. Toxicological Assessment and Potential Protective Effects of Brassica Macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract Against Copper Sulphate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. Nutraceuticals 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010003

Cicio A, Félix LM, Monteiro SM, Bruno M, Zizzo MG, Serio R. Toxicological Assessment and Potential Protective Effects of Brassica Macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract Against Copper Sulphate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. Nutraceuticals. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleCicio, Adele, Luís M. Félix, Sandra Mariza Monteiro, Maurizio Bruno, Maria Grazia Zizzo, and Rosa Serio. 2026. "Toxicological Assessment and Potential Protective Effects of Brassica Macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract Against Copper Sulphate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos" Nutraceuticals 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010003

APA StyleCicio, A., Félix, L. M., Monteiro, S. M., Bruno, M., Zizzo, M. G., & Serio, R. (2026). Toxicological Assessment and Potential Protective Effects of Brassica Macrocarpa Guss Leaf Extract Against Copper Sulphate-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. Nutraceuticals, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010003