Scope and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- V4_Airport/Border/Airline Staff

- V4_Educators

- V4_Factory workers

- V4_Frontline retail workers

- V4_Frontline/essential workers (when subcategories not specified)

- V4_Government officials

- V4_Healthcare workers/carers (excluding care home staff)

- V4_Military

- V4_Other “high contact” professions/groups (taxi drivers, security guards)

- V4_Police/first responders

- V4_Religious/Spiritual Leaders

- V4_Staff working in an elderly care home

3. Results

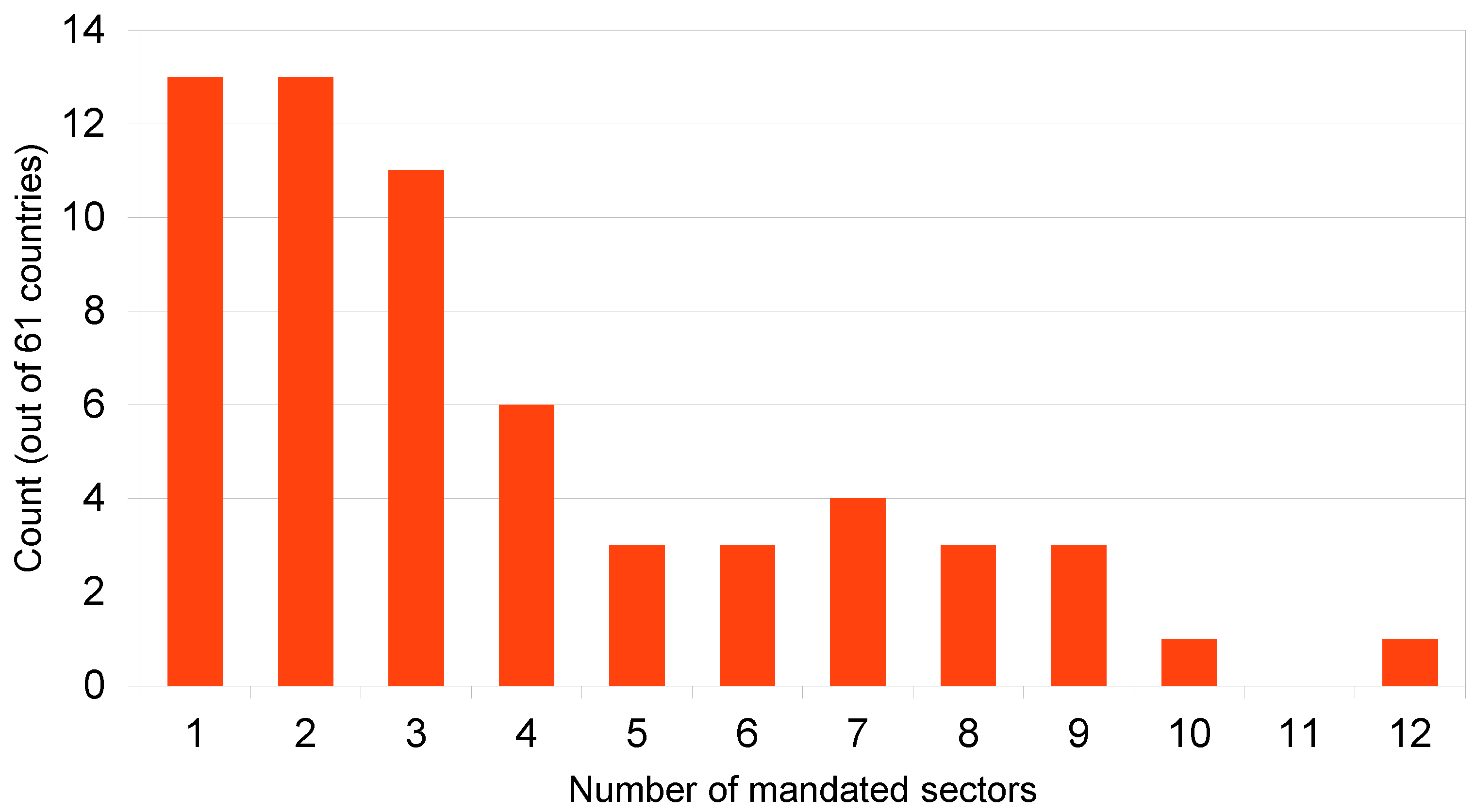

3.1. Frequencies of Workplace Vaccination Mandates

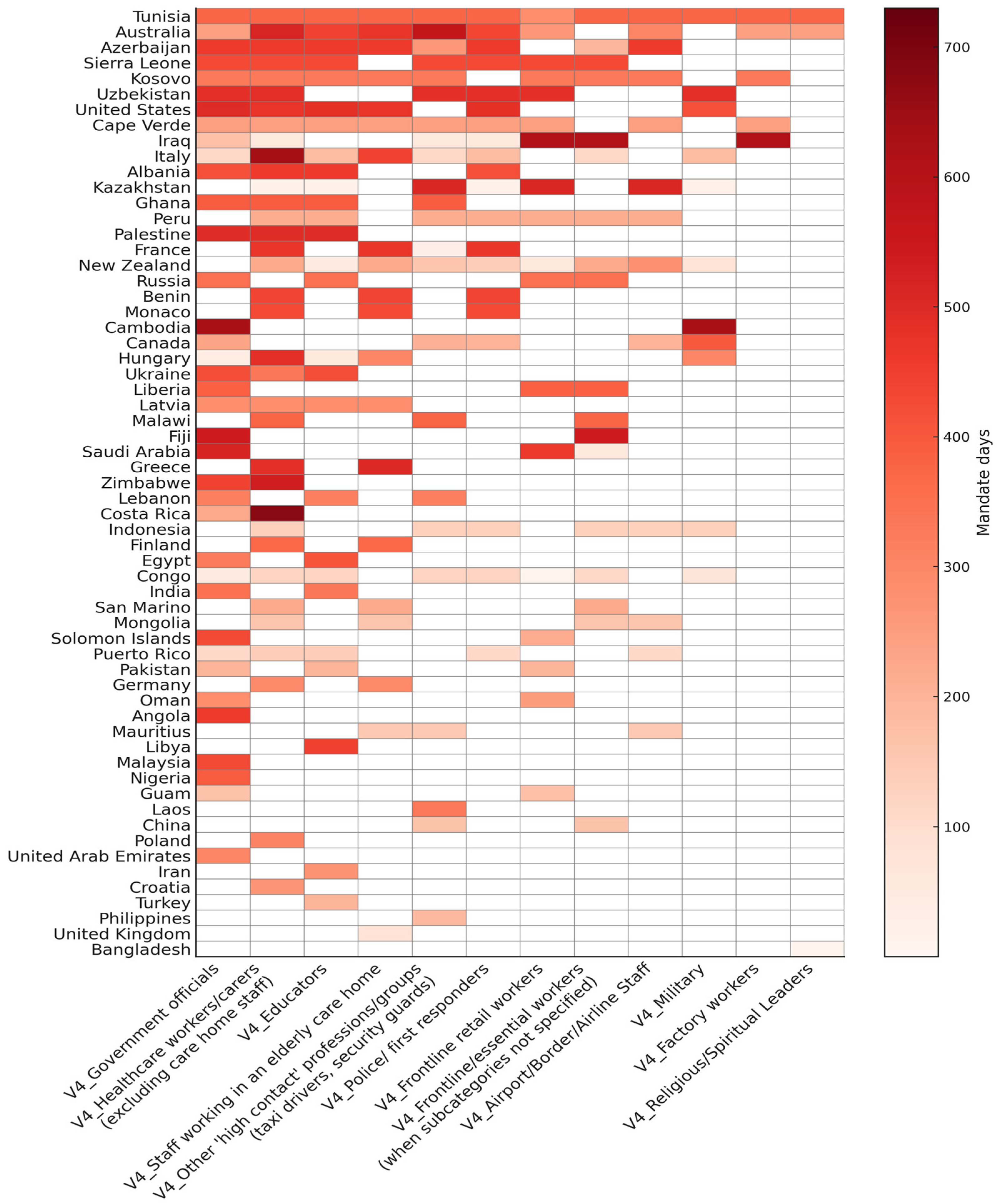

3.2. Duration of Mandates by Sector and Country

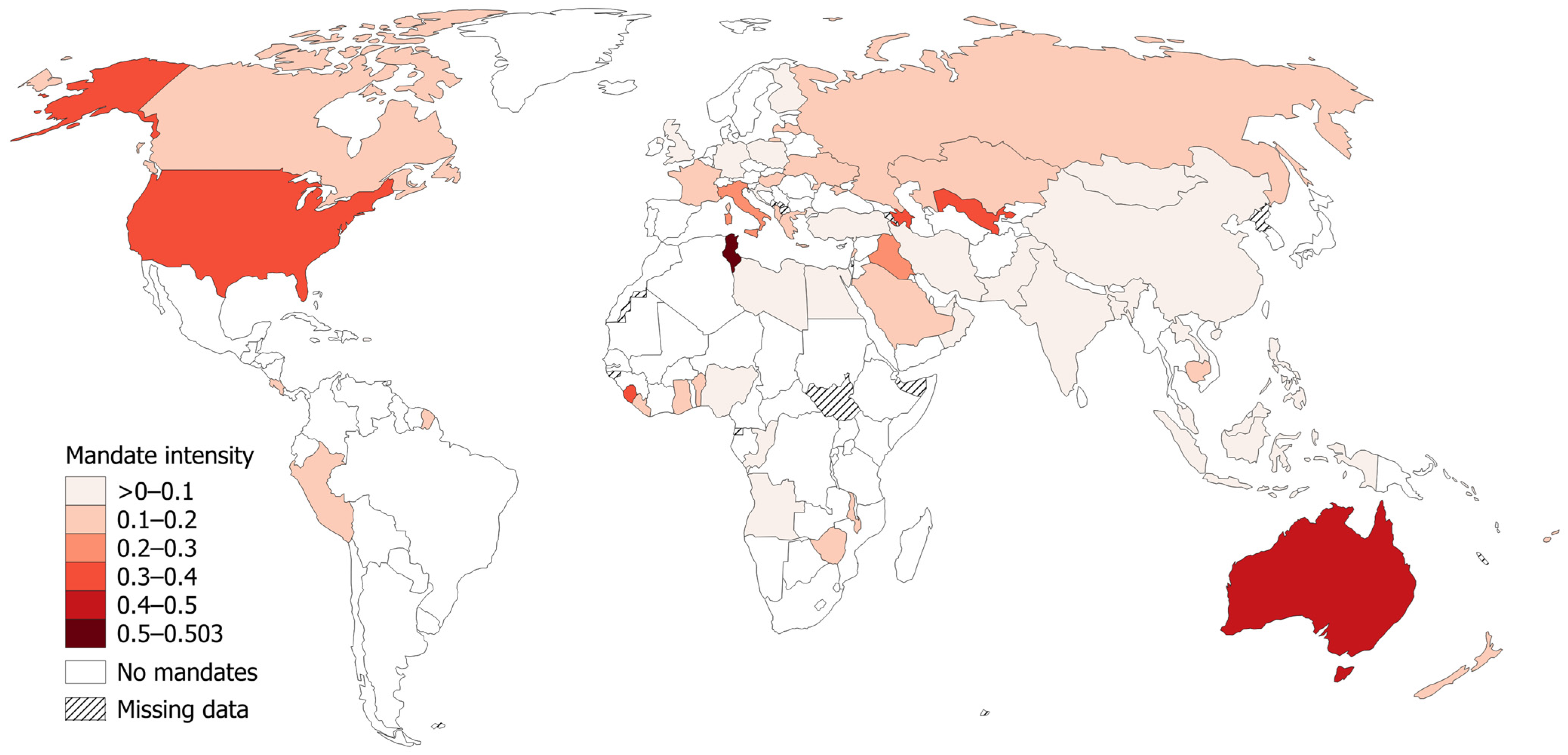

3.3. Global Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates

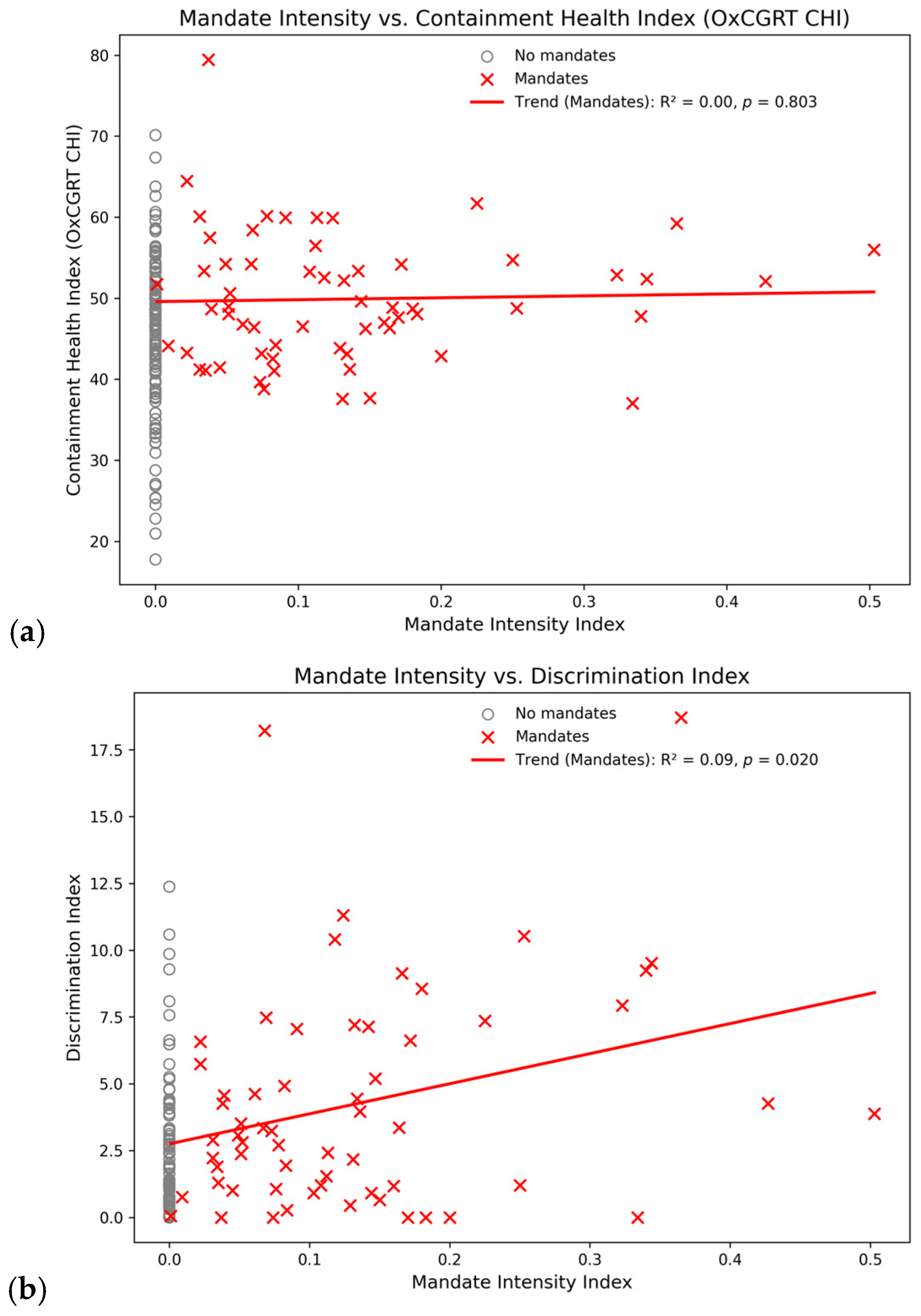

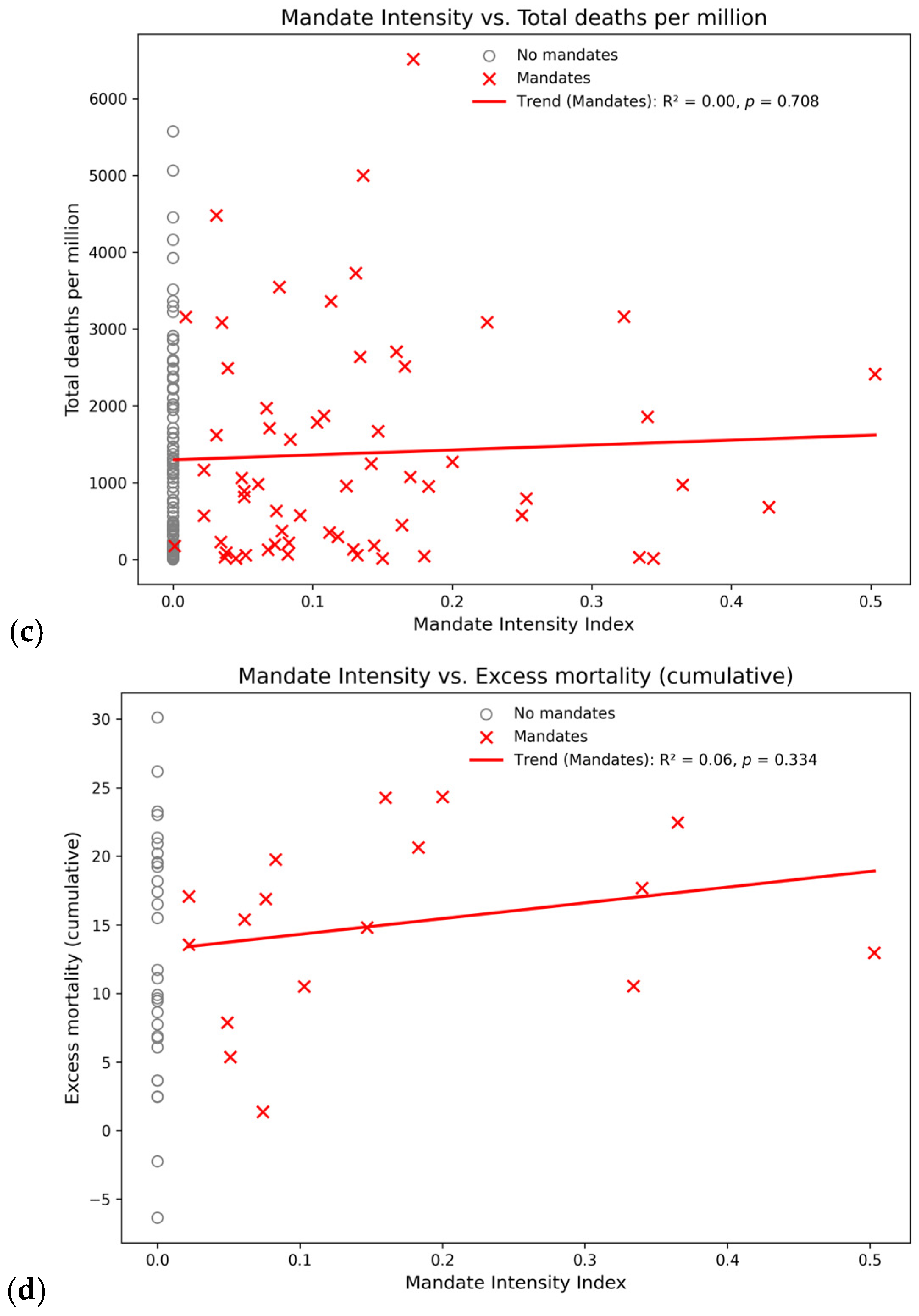

3.4. Correlation of Workplace Mandates with Related Public Health Measures and Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. UN Chief: Global Vaccination Plan is ‘Only Way Out’ of the Pandemic. UN News. 31 November 2021. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1106792 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Doshi, P. Will COVID-19 vaccines save lives? Current trials aren’t designed to tell us. BMJ 2020, 21, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gostin, L.O.; Salmon, D.A.; Larson, H.J. Mandating COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA 2021, 325, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, M.M.; Opel, D.J.; Benjamin, R.M.; Callaghan, T.; DiResta, R.; Elharake, J.A.; Flowers, L.C.; Galvani, A.P.; Salmon, D.A.; Schwartz, J.L.; et al. Effectiveness of vaccination mandates in improving uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in the USA. Lancet 2022, 400, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, E.; Chimowitz, M.; Long, T.; Varma, J.K.; Chokshi, D.A. The effect of a proof-of-vaccination requirement, incentive payments, and employer-based mandates on COVID-19 vaccination rates in New York City: A synthetic-control analysis. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e754–e762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, B.L.; Amiel, P.J.; Ternier, A.; Helmy, H.; Lim, S.; Chokshi, D.A.; Zucker, J.R. Increases in COVID-19 Vaccination Among NYC Municipal Employees After Implementation of Vaccination Requirements. Health Aff. 2022, 42, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, S.K.; Tabaei, B.P.; Culp, G.M.; Levin-Rector, A.; Kishore, N.; Baumgartner, J. Effects of Return-to-Office, Public Schools Reopening, and Vaccination Mandates on COVID-19 Cases Among Municipal Employee Residents of New York City. J. Occup. Environ. 2023, 65, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferranna, M.; Robinson, L.A.; Cadarette, D.; Eber, M.R.; Bloom, D.E. The benefits and costs of U.S. employer COVID-19 vaccine mandates. Risk Anal. 2023, 43, 2053–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. As Employers and Colleges Introduce COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates, Wider Use “Remains an Open Question”. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e210874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, M.B.; Kates, J. Key Questions About COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) Brief. 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/key-questions-about-covid-19-vaccine-mandates/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Golos, A.M.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Ritter, A.Z.; Bair, E.F.; Chapman, G.B. Effects of an Employee COVID-19 Vaccination Mandate at a Long-Term Care Network. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, D. COVID-19 vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 375, n2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, S.J. Mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for healthcare workers: All employers are bound by health and safety laws to reduce risk. BMJ 2021, 375, n3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, K.; Roberts, L.; Blyth, C.C.; Carlson, S.J. Western Australian health care workers’ views on mandatory COVID-19 vaccination for the workplace. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.; Dunikoski, L.; Brantner, R.; Fletcher, D.; Saltzberg, E.E.; Urdaneta, A.E.; Wedro, B.; Giwa, A. An ethical analysis of the arguments both for and against COVID-19 vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 64, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Kingori, P. No Jab, No Job? Ethical Issues in Mandatory COVID-19 Vaccination of Healthcare Personnel. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K.; De Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, J.; Savulescu, J.; Brown, R.C.H.; Wilkinson, D. The unnaturalistic fallacy: COVID-19 vaccine mandates should not discriminate against natural immunity. J. Med. Ethics 2022, 48, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.; Ndlovu, L.; Baiyegunhi, O.O.; Lora, W.S.; Desmond, N. Coercive public health policies need context-specific ethical justifications. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 2024, 43, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozik, E. Public health ethics: Critiques of the “new normal”. Monash Bioeth. Rev. 2022, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, M. Ethics of vaccine refusal. J. Med. Ethics 2022, 48, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraaijeveld, S.R.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E. A Scalar Approach to Vaccination Ethics. J. Ethics 2024, 28, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron-Blake, E.; Tatlow, H.; Andretti, B.; Boby, T.; Green, K.; Hale, T.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Pott, A.; Wade, A.; et al. A panel dataset of COVID-19 vaccination policies in 185 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Andrea, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Mandatory for Federal Workers by End of October, Trudeau Announces. Global News. 6 October 2021. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/8246863/trudeau-announce-covid-19-vaccine-mandate-impact-federal-workers-travel/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19 (Working Paper, Version 15 BSG-WP-2020/032). 2023. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/BSG-WP-2020-032-v15.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Gavrilov, D.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Ferguson, D. Coronavirus: Returning to Work (No. CBP 8916). United Kingdom, House of Commons Library. 2021. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8916/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ahmed, A.A. If Re-Elected, Trudeau Liberals Will Mandate Proof of Vaccination Without ‘Fear of Legal Action.’ The Post Millennial. Available online: https://thepostmillennial.com/trudeau-liberals-proof-of-vaccination (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention L’Obligation Vaccinale. Web Page (Archived), Government of France. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20230213232129/https://sante.gouv.fr/grands-dossiers/vaccin-covid-19/je-suis-un-professionnel-de-sante-du-medico-social-et-du-social/obligation-vaccinale (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Eurostat Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Web Page, European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Deaths_during_the_COVID-19_pandemic (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Klibi, S. Tunisia: Legal Response to COVID-19. In The Oxford Compendium of National Legal Responses to COVID-19; Jeff, K., Octávio, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Available online: https://oxcon.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law-occ19/law-occ19-e48 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- State Government of Victoria Information for Industry and Workers Required to be Vaccinated. 2021. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20211012060800/https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/information-workers-required-be-vaccinated (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Azerbaijan. On Amendments to Decision No. 151 of 26 May 2021 On Measures Regarding the Extension of the Special Quarantine Regime and the Lifting of Certain Restrictions (Decision No. 229). Available online: https://nk.gov.az/az/document/5476/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Baldor, L.C. New Law Ends COVID-19 Vaccine Mandate for US Troops. AP News. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/biden-lloyd-austin-e4047962b92087be278c6886e2e2d0c5 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- República de Cabo Verde. Conselho de Ministros, Resolução nº 82/2021. Boletim Oficial Suplemento, I Série, No. 81. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250620043852/https://covid19.cv/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/bo_23-08-2021_81.pdf (accessed on 23 August 2021).

- Paterlini, M. COVID-19: Italy makes vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ 2021, 373, n905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euronews Italy First in Europe to Require All Employees to Have COVID Health Pass. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2021/09/16/italy-set-to-be-first-in-europe-to-require-all-employees-to-have-covid-health-pass (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Rinner, C.; Uda, M.; Manwell, L. A Global Index to Quantify Discrimination Resulting from COVID-19 Pandemic Response Policies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinner, C. Unexpected patterns in the global COVID-19 pandemic data. Int. J. Sch. Res. Multidiscip. Stud. 2023, 3, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T.; Reiss, D.R. Workplace Vaccine Mandates. In Vaccine Law and Policy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C. Is COVID-19 “vaccine uptake” in postsecondary education a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry. Health 2024, 28, 831–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardosh, K.; Krug, A.; Jamrozik, E.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Prasad, V.; Makary, M.A.; Baral, S.; Høeg, T.B. COVID-19 vaccine boosters for young adults: A risk benefit assessment and ethical analysis of mandate policies at universities. J. Med. Ethics 2024, 50, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singanayagam, A.; Hakki, S.; Dunning, J.; Madon, K.J.; Crone, M.A.; Koycheva, A.; Derqui-Fernandez, N.; Barnett, J.L.; Whitfield, M.G.; Varro, R.; et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B. 1.617. 2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: A prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N. Is resistance to COVID-19 vaccination a “problem”? A critical policy inquiry of vaccine mandates for healthcare workers. AIMS Public Health 2024, 11, 688–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N.; Moncrieffe, R. COVID-19 vaccination decisions and impacts of vaccine mandates: A cross sectional survey of healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada. J. Public Health Emerg. 2024, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C.; Hemsing, N.; Moncrieffe, R. “It isn’t about health, and it sure doesn’t care”: A qualitative exploration of healthcare workers’ lived experience of the policy of vaccination mandates in Ontario, Canada. J. Public Health Emerg. 2025, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, L.F.; Begley, A. COVID-19 vaccination requirements for Ireland’s healthcare students. Crit. Soc. Policy 2023, 43, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Gandsman, A. Polarizing figures of resistance during epidemics. A comparative frame analysis of the COVID-19 freedom convoy. Crit. Public Health 2023, 33, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, M.A.; Parmet, W.E.; Reiss, D.R. Employer-Mandated Vaccination for COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, M.A. COVID Vaccine Mandates and Religious Accommodation in Employment. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2022, 52, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, L.G.; Lüthy, A.; Ramanathan, P.L.; Baldesberger, N.; Buhl, A.; Schmid Thurneysen, L.; Hug, L.C.; Suggs, L.S.; Speranza, C.; Huber, B.M.; et al. Healthcare professional and professional stakeholders’ perspectives on vaccine mandates in Switzerland: A mixed-methods study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 7397–7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Trujillo, J.; Waldman, D. Latest Developments on Vaccine Mandates in Latin America. Seyfarth, Legal Update. Available online: https://www.seyfarth.com/news-insights/latest-development-on-vaccine-mandates-in-latin-america.html (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- World Law Group. Mexico: Q&A—Employer COVID-19 Vaccination Policies (Updated). Available online: https://www.theworldlawgroup.com/membership/news/mexico-q-a-employer-covid-19-vaccination-policies (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Wood, D. Mexican President Says No Need to Show Proof of Vaccination. TravelPulse NorthStar. Available online: https://www.travelpulse.com/news/destinations/mexican-president-says-no-need-to-show-proof-of-vaccination (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Bloomberg Japan Leads the G-7 in COVID Shots Without a Mandate in Sight. The Malaysian Reserve, 16 November 2021. Available online: https://themalaysianreserve.com/2021/11/16/japan-leads-the-g-7-in-covid-shots-without-a-mandate-in-sight/ (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Swerling, G.; Riley-Smith, B. Exclusive: U-turn on Mandatory COVID Vaccinations for NHS and Social Care Workers: Sajid Javid Set to Scrap Requirements After Warnings that Jabs Policy Could Lead to Shortage of 80,000 Workers. The Telegraph. 31 January 2022. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2022/01/30/front-line-health-staff-no-longer-need-covid-vaccines/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Doshi, R.H.; Nsasiirwe, S.; Dahlke, M.; Atagbaza, A.; Aluta, O.E.; Tatsinkou, A.B.; Dauda, E.; Vilajeliu, A.; Gurung, S.; Tusiime, J.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage—World Health Organization African Region, 2021–2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havyarimana, M. Burundi’s COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign Accelerates. Gavi VaccinesWork. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/burundis-covid-19-vaccination-campaign-accelerates (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Ontario Ministry of Health. Ontario Makes COVID-19 Vaccination Policies Mandatory for High-Risk Settings. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1000750/ontario-makes-covid-19-vaccination-policies-mandatory-for-high-risk-settings (accessed on 17 August 2021).

| Mandate Intensity Index | Country * | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| 0.503 | Tunisia | 1. |

| 0.427 | Australia | 2. |

| 0.365 | Azerbaijan | 3. |

| 0.344 | Sierra Leone | 4. |

| 0.340 | Kosovo | 5. |

| 0.334 | Uzbekistan | 6. |

| 0.323 | United States | 7. |

| 0.253 | Cape Verde | 8. |

| 0.250 | Iraq | 9. |

| 0.225 | Italy | 10. |

| Non-Zero Countries | All Countries | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace Mandate Intensity vs. Related Indicators | p_Value | R_Squared | p_Value | R_Squared |

| Containment and Health Index | 0.803 | 0.00 | 0.030 | 0.03 |

| Discrimination Index | 0.020 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Total COVID-19 deaths per million | 0.708 | 0.00 | 0.280 | 0.01 |

| Excess mortality cumulative | 0.334 | 0.06 | 0.224 | 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rinner, C.; Uda, M.; Manwell, L. Scope and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010037

Rinner C, Uda M, Manwell L. Scope and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleRinner, Claus, Mariko Uda, and Laurie Manwell. 2026. "Scope and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates During the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010037

APA StyleRinner, C., Uda, M., & Manwell, L. (2026). Scope and Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Workplace Vaccination Mandates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010037