Abstract

This scoping review explores the patterns of heteronormativity in healthcare sectors across Africa and its impact on the health and well-being of LGBTIQ+ individuals. By analyzing publications from major academic databases, this study identifies key themes and research gaps in the discourse on LGBTIQ+ health and heteronormativity in Africa. The findings underscore the urgent need to address these heteronormative barriers in alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (good health and well-being) and SDG 10 (reduced inequalities). Addressing heteronormativity in healthcare is essential for promoting equitable, inclusive healthcare systems and improving health outcomes for LGBTIQ+ populations across the continent.

1. Introduction

A substantial body of literature on sexualities in Africa has established that LGBTIQ+ identities are often exposed to intolerance and limited acceptance due to the perpetuation of heteronormative ideologies [1,2,3,4]. The term heteronormativity was coined by Warner [5], who argued against the universalization of a heterosexual worldview that excluded possibilities of sexual diversity. Warner [5], in conjunction with Katz [6], questions the naturalization of heterosexuality by arguing that it is not a natural existence but a historically invented mode of sexual organization that was intended to be universal, unchanging, and essential. Heterosexuality, therefore, represents a specific sexual–political institution that establishes distinct expectations for its members and marginalizes those who fail to conform to dominant heterosexual norms [6]. Thus, the invention and universalization of the institution of heterosexuality informed the construction of compulsory heterosexual expectations within various social spaces, compelling individuals to be sexually attracted to members of the opposite sex and desire the heterosexual family organization [7]. In addition, the institution of compulsory heterosexuality prioritizes the reproductive nature of sexual relations, consequently excluding sexual behaviors that are non-reproductive, inter-alia same-sex sexual relations. Butler [8] teaches us that heterosexual norms are structured within a matrix that delineates a tripartite relationship between sex, sexual identity, and the gendered norms of masculinity and femininity, which are conventionally associated with specific bodies. Heteronormativity is, therefore, a sociocultural norm that recognizes heterosexuality as the only way to express a sexual identity, with no other possibilities [9]. Heteronormative ideologies emphasize the procreational character of sexual relationships, normalizing heterosexuality, while rendering other expressions of sexuality unnatural. Within a heteronormative framework, male and female sexual bodies are assumed to align with masculine and feminine gendered categories and the binary gendered desire for the opposite sex [8].

While the concept of heteronormativity was originally coined and first applied in the Global North, scholars from the Global South, particularly in Africa, have highlighted its relevance and significance, often demonstrating how it hinders the recognition of sexual minority identities and contributes to their exclusion and persecution in diverse contexts [10]. Dominant sexuality discourses in African countries are rooted in heteronormative worldviews that are guided by religious doctrines and African cultural traditions that are intolerant of sexual diversity [11]. The implementation of these anti-gay laws and punishments are informed by heteronormative religious doctrines, specifically from the Christian and Islamic religions, which most African subscribe to. They are also driven by the idea that African cultural traditions do not recognize sexual relations between men or women.

These heteronormative ideologies have contributed to legal frameworks and social structures that marginalize LGBTIQ+ individuals across the African continent. A key argument among many African societies is that diverse sexual identities are Western imports that never existed in Africa [12,13,14]; however, some scholars challenge this claim, by demonstrating that sexual minority identities have always existed in Africa, even before the colonization of most African countries and were incorporated into African cultural traditions and social structures in various ways [1,2,3,4]. In their writings, these scholars highlight historical accounts, indigenous practices, and oral traditions that acknowledge same-sex desires and non-binary gender identities and challenge the view that diverse sexual identities are foreign to African societies. They instead argue that the colonization of Africa, and the imposition of Western morality and legal systems, led to the suppression and criminalization of alternative expressions of gender and sexuality in Africa [4,9,15]. Additionally, religious ideologies, particularly Christian and Muslim, have been used to argue against same-sex sexual desires and relationships, which has informed unjust legal frameworks and policies that ban alternative expressions of sexuality in many African countries [14,16]. Colonial legal and religious systems played a significant role in the oppression and criminalization of sexual minority identities in many African countries [1,3,17,18], indicating the degree of intolerance and lack of acceptance of sexual diversity across the continent. These unjust legal frameworks inform the stigmatization, discrimination, and exclusion of LGBTIQ+ individuals in various social contexts, including homes, schools, workplaces, religious institutions, universities, and the health sector [19]. Thus, heteronormative ideologies are embedded in these institutions, limiting the expression of sexually diverse identities and limited access for LGBTIQ+ communities. Although access to quality healthcare services is considered a basic human right globally, the international literature has established that for LGBTIQ+ people, access is often hindered by heteronormative ideologies and cultures that do not recognize sexual diversity. This is particularly evident in African countries where sexual minority individuals are exposed to homophobic violence and intimidation [10,16]. While some African countries, such as South Africa, legally prohibit the discrimination of people based on their sexual identities, research has established that heteronormativity is still evident and forms part of the workplace cultures in healthcare institutions, affecting how LGBTIQ+ people are treated when they seek medical attention [20,21]. Inclusive legal frameworks, such as those of South Africa and Mozambique, two of the few countries in Africa that fully recognize sexual diversity and protect the rights of sexual and gender minorities, do not guarantee the elimination of heteronormative expectations that dictate how people should express their sexual identities and perform their gender identities. As such, many LGBTIQ+ people in Africa live in fear and may avoid seeking medical assistance, especially for illnesses that require them to disclose their sexual identities [21,22]. The hindrance and limited access to healthcare services significantly affects the wellbeing of sexual minority individuals who are vulnerable to mental health issues, Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). The increased burden of HIV and STIs amongst the LGBTIQ+ community is also informed by the heteronormative barriers to access and use of HIV and STI prevention services in different African countries [19,23]. Heteronormative ideologies inform medical training and health policies, often neglecting the unique health needs of LGBTIQ+ individuals. The absence of inclusive healthcare structures exacerbates disparities in mental health, HIV prevention, and access to sexual and reproductive health services for sexual minorities [24,25]. Irrespective of the growing recognition of these issues, no comprehensive review has examined the extent of heteronormativity in African healthcare systems. Previous reviews such as those conducted by Müller & Hughes [26] and Newman-Valentine & Duma [27] have addressed specific aspects of LGBTIQ+ health, particularly in South Africa. However, none of these reviews explored the broader patterns of heteronormativity in healthcare institutions across Africa. This scoping review seeks to address this gap by mapping the existing literature on the social and structural barriers that LGBTIQ+ people encounter in healthcare settings across various African countries.

The social exclusion and lack of recognition of LGBTIQ+ people in health facilities undermine international efforts towards achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), particularly SDG 3 on good health and well-being and SDG 10 on reduced inequalities. The primary aim of this scoping review is to identify and summarize the literature on the impact of heteronormativity on the healthcare experiences of sexual minority individuals in Africa. Exploring the various ways in which heteronormative ideologies inform policies, medical training, and healthcare providers’ interactions with patients helps to bring forth the barriers LGBTIQ+ individuals encounter in healthcare. Consequently, this scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is the scope and nature of the existing literature on heteronormativity in African healthcare settings? Ultimately, this scoping review focuses on identifying key themes, research gaps, and policy implications in the literature, with the goal of informing future interventions and reforms that are aimed at promoting inclusive healthcare.

The heterogeneity of laws regulating LGBTIQ+ rights in various African countries presents challenges in drawing broad conclusions. In some countries, sexual minority identities are criminalized and punishable by law, while others offer varying degrees of legal recognition and protection (1,17,18]. In Nigeria, Uganda, and Ghana, homosexuality is criminalized and punishable by imprisonment and, in extreme cases, the death penalty [17,28]. Countries such as Tanzania and Sudan have also employed strict anti-LGBTIQ+ laws that contribute to the continuing social stigma that leads to the avoidance of healthcare services due to fear of discrimination [29]. In contrast, South Africa has progressive legal frameworks that protect sexual minority rights; however, studies have demonstrated that heteronormative biases persist in healthcare settings, affecting access to quality healthcare services [20,21]. Same-sex relationships were decriminalized in Mozambique in 2015 through its revised penal code, yet some reports indicate that LGBTIQ+ people still experience discrimination when seeking healthcare services [30]. Botswana has made significant strides in recognizing sexual minority rights by decriminalizing same-sex relationships in 2019, but systematic challenges remain in healthcare institutions [28]. This scoping review acknowledges these differences and considers how legal contexts inform the healthcare experiences of sexual minority individuals. Where necessary, the literature will be contextualized to reflect variations in healthcare access based on the legal and social contexts of these African countries. In examining the existing literature on heteronormativity in African healthcare institutions, this scoping review highlights the urgent need to address discriminatory practices that hinder sexual minority individuals from accessing equitable healthcare. Addressing heteronormativity in healthcare is crucial to fostering inclusive and non-discriminatory healthcare environments that uphold the rights and dignity of all individuals, irrespective of their gender and sexual identities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Typology, Research Question, Aims, and Justification

A scoping review methodology was chosen to address the research question: What is the scope and nature of the existing literature on heteronormativity in African healthcare settings? Scoping reviews are effective for broadening the understanding of topics that have yet to be fully explored, as they systematically chart the existing body of evidence and identify gaps in the knowledge [31,32]. In the context of heteronormativity and healthcare in Africa, this approach allows for a comprehensive overview of how societal norms surrounding sexuality influence healthcare systems, practices, and outcomes, with particular attention to how these factors affect LGBTIQ+ populations. Given that heteronormativity is a key determinant of health inequities, especially in contexts where LGBTIQ+ individuals may face legal and social stigma, mapping out the existing literature will offer valuable insights into the scope and depth of research in this area.

This scoping review is guided by the six-stage framework developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute [33], which provides a systematic process for identifying, selecting, and synthesizing relevant studies. The stages involve defining the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting studies for inclusion, charting the data, collating and summarizing the findings, and finally, reporting the results. Through this approach, this study will not only assess the available literature but will also help to identify critical gaps in the knowledge, providing a foundation for future research aimed at addressing the health disparities faced by LGBTIQ+ communities in Africa. By mapping the literature on heteronormativity in healthcare, this study will contribute to broader discussions on healthcare equity and the steps needed to help African countries achieve SDG 3 and SDG 10, promoting access to respectful and inclusive healthcare for all populations, regardless of gender and sexual identity.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Search Strategy

To gather the relevant academic documents for this study, the researchers employed a systematic approach utilizing a variety of reputable databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. These databases were chosen for their comprehensive access to a wide range of scholarly sources, such as peer-reviewed journal articles, theses, book chapters, and books, all of which met the study’s inclusion criteria. The scoping review specifically focused on studies conducted in Africa, this is mainly due to Africa’s distinct socio-cultural and political contexts, which has been shaped by colonial histories, religious conservatism, and legal barriers, significantly influence LGBTQI+ healthcare experiences [34]. Limiting the review to this region ensures contextually relevant insights into these unique challenges. To maintain academic rigor, only peer-reviewed articles are included, as they undergo expert evaluation, enhancing the credibility and reliability of findings [31]. Additionally, restricting the review to English-language articles ensures accessibility and consistency in analysis, particularly due to the researchers lacking proficiency in other languages in Africa such as French, Portuguese, and Spanish [35]. While this may exclude some perspectives, English remains the universal language in academic publishing, ensuring broad coverage of the relevant literature.

The search strategy was designed to capture a broad spectrum of the relevant literature by utilizing specific keywords aligned with the research objectives. Key search terms included “heteronormativity”, “healthcare”, “LGBTQI”, and “Africa”. Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) were strategically applied to refine the search and ensure that only the most pertinent documents were selected. The review focused on the literature published within the past 19 years (2005–2024) to capture the latest insights into the role of heteronormativity in healthcare settings and inform future research directions and potential interventions. The primary search keywords included heteronormativity, healthcare or health, LGBTQI or lesbian or gay or bisexual or transgender or queer or intersex, and Africa. To enhance the search strategy and ensure broader coverage, secondary search keywords incorporated heteronormativity, healthcare or health, LGBTQI or lesbian or gay or bisexual or transgender or queer or intersex, along with Africa and its regional subdivisions: Southern Africa, West Africa, East Africa, North Africa, and Central Africa. This approach aimed to capture relevant studies across different geographical contexts and terminologies. Table 1 and Table 2 below outlines the search terms that we used and the eligibility criteria that were followed in the selection of studies that were relevant to the scoping review.

Table 1.

Search terms used.

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

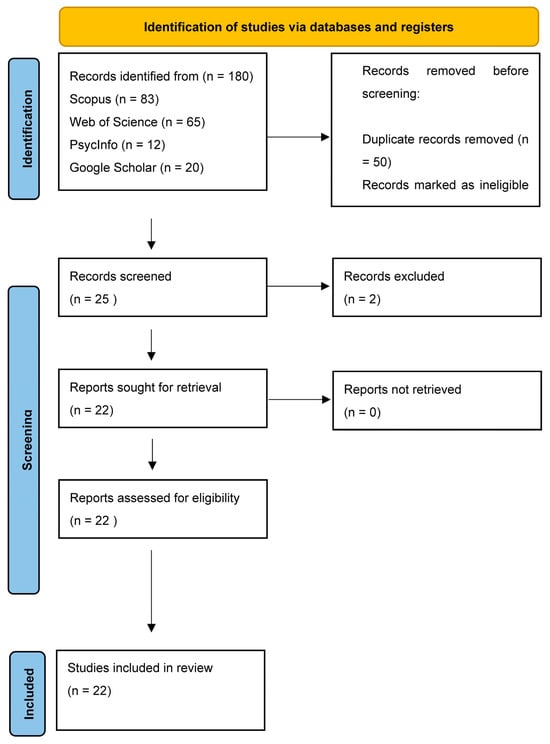

Once the search process was completed, all identified studies were imported into Covidence™ for further analysis. Covidence™ automatically removed any duplicate entries, ensuring that only unique studies were considered. The screening process was carried out in two stages: title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening. During each stage, studies were excluded if it was determined that they did not meet the pre-established eligibility criteria. To ensure consistency and minimize bias, two authors independently screened the articles at both stages. In cases of disagreement, the issue was resolved through discussion or by consulting a third author. The final study selection process was documented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) flow diagram [36]. This systematic approach to study selection helped to maintain transparency and rigor throughout the review process.

2.4. Data Analysis

This study utilized Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA), as outlined by Braun and Clarke [37], to investigate key themes and patterns within the literature on heteronormativity and healthcare in Africa. This approach was well-suited to the research aims, as it supports the systematic identification of recurring ideas while aligning with the interpretivist framework that informs this study [38]. RTA enables an in-depth exploration of how heteronormative structures influence healthcare policies, access, and experiences, particularly for sexual and gender minorities. By emphasizing a flexible and iterative engagement with data, this method allows themes to emerge organically rather than being confined to predefined categories, facilitating a deeper understanding of the relationship between heteronormativity and healthcare in African contexts.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1, only 180 articles were identified and imported into Covidence. A total of 22 papers met our eligibility criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the 22 included publications, 21 were primary research papers, while 2 were review papers. Of these, 22 were journal articles, and 1 was a PhD thesis. Most of the studies (n = 16) were conducted in South Africa. One paper included studies conducted in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, respectively, while another focused on five countries in Southern Africa, with notable representation from three French-speaking countries: Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, and Senegal. Overall, the studies included in this review represented regions in Southern, Western, and Eastern Africa. The participants mainly consisted of LGBTQI individuals in Africa.

4. Findings

The following themes were identified:

4.1. Theme 1: Heteronormativity and Structural Barriers in Healthcare

Healthcare spaces in many African contexts are structured around policies that fail to recognize or address the specific health needs of LGBTIQ+ individuals. As scholars such as Ratele [39] and Currier [24] have noted, the absence of inclusive health policies reflects broader socio-political structures that marginalize queer identities, often portraying them as deviant or un-African. These policies contribute to the systemic exclusion of LGBTIQ+ individuals from mainstream healthcare services, reinforcing heteronormativity as the standard for health and well-being. Furthermore, the historical and cultural framing of queerness as pathological—rooted in colonial-era laws and religious dogma—continues to shape contemporary healthcare practices, leading to the invisibilization of sexual and gender minorities within national health systems. This exclusion forces LGBTIQ+ individuals to either forego essential healthcare or seek services in environments where they may not feel safe or affirmed.

The pervasive stigma and discrimination experienced by LGBTIQ+ individuals in healthcare settings have far-reaching consequences on their health-seeking behaviors and overall well-being. Studies by Müller [34] and Fay et al. [40] illustrate how men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender persons, in particular, face prejudicial treatment from healthcare providers, often resulting in the denial of services, substandard care, or outright hostility. Such discrimination discourages LGBTIQ+ individuals from accessing healthcare facilities, leading to delays in seeking treatment and increased health vulnerabilities. This aligns with research by Logie et al. [41], which demonstrates how stigma in healthcare settings exacerbates health disparities among LGBTIQ+ populations, particularly in relation to HIV prevention, mental health services, and sexual and reproductive healthcare. The intersection of institutional bias and individual prejudice creates a healthcare environment that is not only exclusionary but also actively harmful to LGBTIQ+ persons who require competent and affirming medical attention.

The marginalization of LGBTIQ+ individuals within public healthcare systems is further compounded by their invisibility in health education and training programs. Research by Epprecht [1] has highlighted how medical and nursing curricula in many African countries lack substantive content on LGBTIQ+ health, leaving healthcare providers ill equipped to provide competent care. This lack of education reinforces discriminatory attitudes among health professionals, as seen in campus healthcare settings where LGBTIQ+ students report experiencing significant prejudice from university medical staff [42]. As a result, LGBTIQ+ individuals are often forced to develop subversive strategies to access care, such as withholding information about their sexual or gender identities to avoid mistreatment. However, as Mogotsi, I., et al. [43] argue, these coping mechanisms are unsustainable and place the burden of navigating discriminatory systems on individuals rather than prompting necessary structural reforms.

4.2. Theme 2: Barriers to Healthcare Access for LGBTIQ+ Individuals and Its Impact

LGBTIQ+ individuals face significant structural and social barriers to healthcare access, often driven by stigma, discrimination, and legal restrictions. Fear of disclosure due to stigma prevents many from seeking timely medical care, as accessing services can expose them to harassment or legal repercussions in contexts where homosexuality is criminalized [41]. Healthcare access is frequently contingent on conforming to heteronormative norms, forcing individuals to suppress their identities to receive appropriate care [34]. Transgender men and “tomboys” experience additional obstacles, including outright denial of services, while women who have sex with women (WSW) often encounter healthcare professionals who dismiss their sexual and reproductive health needs due to misconceptions about their risk factors [24,44]. Economic constraints, fear of being outed, shame, and direct refusal of care further limit healthcare access, compounding the effects of systemic exclusion [20]. Additionally, rejection by family and community intensifies social isolation, leading to poor mental health outcomes, including depression and engagement in risky sexual behavior as a coping mechanism [43]. The lack of robust social support systems further exacerbates these vulnerabilities, reinforcing cycles of health inequities [45]. Addressing these disparities requires comprehensive policy reforms, LGBTIQ+ inclusive healthcare training, and legal protections to dismantle the barriers that sustain health inequities for LGBTIQ+ populations.

4.3. Theme 3: The Role of Healthcare Providers in LGBTIQ+ Health Outcomes

Despite the growing recognition of LGBTIQ+ health needs, gender-affirming care remains largely unavailable or dependent on the discretion of individual healthcare providers, as institutional support and policy frameworks for such services are often lacking [44]. The absence of structured training in LGBTIQ+ health results in a widespread lack of competence among healthcare professionals, reinforcing discriminatory attitudes and exclusionary practices [34]. Many healthcare providers operate with deeply ingrained biases, which manifest as gatekeeping behaviors, refusal of care, or the imposition of heteronormative treatment approaches that fail to address the unique health concerns of sexual and gender minorities [43]. This institutionalized discrimination underscores the urgent need for comprehensive professional training and sensitization programs that equip healthcare workers with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide inclusive, nonjudgmental, and affirming care to LGBTIQ+ individuals [25]. Without such systemic interventions, LGBTIQ+ individuals will continue to face barriers to essential healthcare services, exacerbating health disparities and reinforcing cycles of marginalization and inequality.

4.4. Theme 4: The Role of Law, Policy, and Institutional Structures

Legal frameworks that criminalize homosexuality significantly shape healthcare access and treatment for LGBTIQ+ individuals, reinforcing stigma and deterring them from seeking necessary medical care [40]. Weak policy enforcement mechanisms fail to protect sexual and gender minorities from discrimination within healthcare settings, leaving them vulnerable to mistreatment by healthcare providers who may hold prejudiced views [34]. The African human rights system has largely been ineffective in addressing violations of LGBTIQ+ healthcare rights, as regional institutions often defer to national sovereignty on matters related to sexual and gender identities [46]. Policy reforms that explicitly recognize and integrate LGBTIQ+ health needs into national health agendas are essential for fostering gender-sensitive and inclusive healthcare services [47]. Structural changes within healthcare institutions—such as provider sensitization programs, the inclusion of LGBTIQ+ health in medical curricula, and the implementation of affirmative policies—are crucial to creating safer and more equitable healthcare environments [25]. Strengthening legal protections for LGBTIQ+ persons, alongside intentional policy shifts, is fundamental to ensuring their right to health and combating systemic discrimination in healthcare across the African continent [48].

4.5. Theme 5: The Need for Inclusive Medical Curriculum and Training

Medical and nursing curricula across Africa largely exclude comprehensive LGBTIQ+ health content, leaving healthcare professionals unprepared to address the specific health needs of sexual and gender minorities [34]. The absence of structured training on LGBTIQ+ health perpetuates gaps in knowledge, reinforcing discriminatory attitudes and limiting access to appropriate care [49]. Additionally, existing curricula fail to create spaces where students can critically engage with and challenge their biases, resulting in healthcare providers who may consciously or unconsciously uphold heteronormative healthcare practices [9]. Given the disproportionate burden of HIV, mental health challenges, and sexual health disparities within LGBTIQ+ communities, integrating these topics into medical education is essential for fostering inclusive and competent healthcare systems [50]. Training programs that explicitly address the intersection of sexuality, gender identity, and health can enhance provider competence and ensure that LGBTIQ+ individuals receive affirming and equitable care [24].

4.6. Theme 6: The Intersection of Colonialism, Religion, and LGBTIQ+ Health

Colonial-era laws and religious doctrines continue to play a significant role in the oppression of LGBTIQ+ individuals in Africa, often embedding discriminatory practices into societal structures [1]. These laws, combined with entrenched social norms rooted in colonial and religious values, perpetuate stigma and discrimination, particularly in healthcare settings, where LGBTIQ+ individuals often face barriers to access and quality care [51]. Addressing this structural discrimination requires dismantling the inherited oppressive legal frameworks and fostering a cultural shift toward inclusivity and equity in both public and private spheres [52]. Such reforms are essential for ensuring that LGBTIQ+ populations are protected and have equitable access to health and social services.

In Table 3 below, we provide a description of the thematic categories that were derived from data analysis. This is followed by Table 4, which provides brief descriptions of the articles that were selected and included in the scoping review.

Table 3.

Thematic categories derived from data analysis.

Table 4.

Overview of articles included in the scoping review.

5. Discussion

The findings from this scoping review highlight the pervasive heteronormative barriers LGBTIQ+ individuals encounter in accessing equitable healthcare in many African contexts. As noted in the themes, heteronormativity and structural barriers within healthcare systems significantly hinder the well-being of sexual and gender minorities. The lack of inclusive health policies, as identified by Ratele [39] and Currier [24], perpetuates systemic exclusion by reinforcing heteronormative standards that marginalize LGBTIQ+ individuals. This exclusion is further compounded by the legacy of colonial-era laws and religious doctrines, which continue to frame LGBTIQ+ identities as deviant or pathological. This historical context not only shapes public attitudes but also informs healthcare practices, leading to the invisibility of LGBTIQ+ individuals within national health systems [41]. Such exclusion forces LGBTIQ+ people to navigate unsafe healthcare spaces or forgo essential services, which exacerbates health disparities and increases vulnerability to conditions such as HIV, mental health issues, and sexual health complications.

The findings demonstrate that the stigma and discrimination that LGBTIQ+ individuals experience in healthcare settings further intensify these barriers to healthcare. Studies by Müller [34] and Fay et al. [40] demonstrate how healthcare providers often treat LGBTIQ+ individuals with hostility, resulting in the denial of care or substandard treatment. These discriminatory practices discourage LGBTIQ+ individuals from seeking medical attention, thereby delaying necessary interventions and increasing health risks. As Mogotsi, I. et al. [43] point out, individuals may adopt coping strategies, such as withholding information about their sexual orientation or gender identity, to avoid mistreatment. However, these strategies are unsustainable and place an unfair burden on individuals, rather than prompting necessary reforms to address the underlying biases within healthcare systems. Logie et al. [41] emphasize that stigma not only affects health-seeking behaviors but also exacerbates existing health disparities, particularly in areas like HIV prevention, mental health services, and sexual health care, where LGBTIQ+ individuals are already disproportionately affected.

The role of healthcare providers in shaping LGBTIQ+ health outcomes is critical, as evidenced by the limited availability of gender-affirming care and the lack of training on LGBTIQ+ health. Reisner et al. [44] and Müller [34] highlight that the absence of structured training programs in many African countries results in healthcare professionals being ill equipped to provide competent, inclusive care. This lack of training reinforces discriminatory attitudes and exclusionary practices that harm LGBTIQ+ individuals. As Poteat et al. [25] argue, without comprehensive professional training and sensitization programs, healthcare providers are likely to perpetuate institutionalized discrimination through gatekeeping behaviors and the imposition of heteronormative treatment approaches. The need for LGBTIQ+-inclusive medical curricula is further emphasized by Singh et al. [72], who stress that integrating LGBTIQ+ health issues into medical and nursing training is crucial to developing a healthcare workforce that is both competent and compassionate in providing care to sexual and gender minorities.

Legal frameworks and policies also play a significant role in shaping healthcare access for LGBTIQ+ individuals. The criminalization of homosexuality in many African countries, as discussed by Fay et al. [40] and Ekine and Abbas [46], not only stigmatizes LGBTIQ+ identities but also deters individuals from seeking necessary healthcare for fear of legal repercussions. Furthermore, limited policy enforcement, particularly in countries that legally recognize the rights of LGBTIQ+ individuals, often leaves LGBTIQ+ individuals vulnerable to discrimination within healthcare settings, where healthcare providers may act with impunity [34]. The African human rights system, according to Farmer, M. [52], has often failed to address these violations effectively, as regional institutions defer to national sovereignty on matters related to sexual orientation and gender identity. To disrupt these barriers, comprehensive policy reforms are necessary, including legal protections for LGBTIQ+ persons and the implementation of affirmative policies that promote inclusive healthcare. As Baral et al. [47] suggest, these reforms are essential for fostering gender-sensitive and inclusive healthcare services that address the specific needs of LGBTIQ+ populations and ensure their right to health and social services.

Ultimately, we argue that the available literature on heteronormativity in healthcare, although limited, highlights the pervasiveness of heteronormative ideologies and their limitations to healthcare for sexual and gender minorities. Much of the literature is situated in South Africa, which is a point of concern considering that most African countries do not acknowledge and protect the rights of LGBTIQ+ communities. While resistance from African governments to legally recognize LGBTIQ+ rights remains prevalent, we contend that fundamental human rights, particularly the right to access healthcare, must take precedence. Healthcare institutions in Africa should prioritize addressing the health needs of sexual and gender minorities, ensuring that care is provided without reinforcing heteronormative ideologies and expectations. While many African countries claim to be democratic states, heteronormative intolerance and the lack of acceptance both on a legal and social basis in many continues to undermine LGBTIQ+ individual’s right to access quality healthcare. Furthermore, it undermines international efforts, made through the SDGs to reduce inequalities and improve access to healthcare, affecting Africa’s progress in achieving these goals. These arguments underscore the need for systemic change within healthcare systems, including policy reforms, education, and training, to address the heteronormative barriers faced by LGBTIQ+ individuals in accessing equitable and inclusive healthcare across Africa.

6. Limitations

The scoping review was limited by the availability of academic sources within the selected databases, which may have affected the comprehensiveness of the included literature. As noted by Tricco et al. [73], database selection plays a crucial role in determining the breadth of literature included in a review, and focusing on specific databases may inadvertently exclude relevant studies. Moreover, studies published in languages not covered in this review could have been overlooked, reducing the study’s global scope [74]. Expanding language inclusion and diversifying database coverage in future research would help to mitigate this limitation and provide a more inclusive view of the topic.

7. Conclusions

This scoping review identified significant themes of heteronormativity in African health institutions. The themes unpacked in this article not only highlight the heteronormative barriers to healthcare in various African contexts but the urgency in dealing with these barriers that hinder LGBTIQ+ communities’ access to quality healthcare. It is concerning that even in a country such as South Africa, where sexual and gender minorities are protected by the constitution and other legal frameworks, LGBTIQ+ individual’s access to quality healthcare is hindered by heteronormative ideologies that are perpetuated and enforced on a social level by health practitioners. The primary aim of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is to transform our world into a better place, where everyone can enjoy good health, justice, and prosperity [75]. African nations must not selectively heed this call, but promote a complete transformation of their health systems, to ensure that people are not left behind or excluded based on how they identify their gender and sexual identities.

Ethical Considerations

This scoping review adhered to ethical considerations, which are outlined in this section. Unlike primary research involving human participants, scoping reviews generally do not require ethical approval; however, researchers must ensure the accurate and unbiased selection, analysis, and reporting of the literature to maintain research credibility (Peters et al., 2020 [33]). This review exclusively included peer-reviewed journal articles, excluding the grey and unpublished literature, to uphold data reliability and consent principles (Tricco et al., 2018 [73]). Additionally, ethical principles such as proper citation, avoiding plagiarism, and preventing misrepresentation of findings were strictly followed throughout the research process (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 [31]). Transparency in methodology was maintained, and this scoping review adhered to established frameworks, including those proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, thereby strengthening its ethical rigor (Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010 [76]).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.R. and T.B.M.; methodology, L.M.R. and T.B.M.; formal analysis, L.M.R. and T.B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.R. and T.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this scoping review are derived from publicly available published sources, which are cited in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Epprecht, M. Sexuality and Social Justice in Africa: Rethinking Homophobia and Forging Resistance; Zed Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Matebeni, Z. The State of LGBT Rights in Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies; Yacob-Haliso, O., Falola, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Msibi, T. The Lies We Have Been Told: On (Homo) Sexuality in Africa. Afr. Today 2011, 58, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyeck, S.N.; Epprecht, M. Sexual Diversity in Africa: Poitics, Theory, and Citizenship; McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, M. Introduction: Fear of a Queer Planet. Soc. Text 1991, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, J. The Invention of Heterosexuality. Social. Rev. 1990, 20, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, A. Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 1980, 5, 631–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tamale, S. (Ed.) African Sexualities: A Reader; Pambazuka Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mkhize, S.P.; Mthembu, A. Unpacking Pervasive Heteronormativity in Sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunity to Embrace Multiplicity of Sexuality. Progress Human Geogr. 2021, 47, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epprecht, M. The Making of ‘African Sexuality’: Early Sources, Current Debates. Hist. Compass 2010, 8, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoma, K. The Paradox and Tension of Moral Claims: Evangelical Christianity, the Politicization and Globalization of Sexual Politics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Crit. Res. Relig. 2014, 2, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoma, K. Christianity, Globalization, and Protective Homophobia: Democratic Contestation of Sexuality in Sub-Saharan Africa; Palgrave Macmillan: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mthembu, S. Homosexuality is not Contemporary in South Africa: The Perceptions of Traditional and Religious Leaders towards Homosexuality. Afr. J. Gend. Soc. Dev. 2023, 12, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amory, D.P. “Homosexuality” in Africa: Issues and Debates. Afr. Stud. Rev. 1997, 25, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, L.; Howell, S. ‘Unnatural’, ‘Un-African’ and ‘Ungodly’: Homophobic Discourse in Democratic South Africa. Sexualities 2014, 17, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salako, P.; LGBTQ+ Nigerians Fear Violence After Sharia Court Death Sentence. Thomson Reuters Foundation News. 2022. Available online: https://news.trust.org/item/20220718141432-pt52j (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Asante, G.A. Anti-LGBT Violence and the Ambivalent (Colonial) Discourses of Ghanaian Pentecostalist-Charismatic Church Leaders. Howard J. Commun. 2020, 31, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssekanatte, T.; Isunju, J.B.; Naume, M.; Buregyeya, E.; Mugambe, R.; Wanyenze, R.K.; Bukenya, J.N. Barriers to Access and Utilisation of HIV/STIs Prevention and Care Services among Trans-Women Sex Workers in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area, Uganda. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 932. [Google Scholar]

- Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A.H. Citizenship Rights, Discrimination and Stigmatisation of LGBTI Students by Health Care Services at a South African Rural-Based University. Agenda 2016, 30, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeza, E. LGBTPQ Youth Negotiating Access to Sexual Health Education and Resources in a Rural South African University. J. Homosex. 2022, 69, 1449–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awondo, P.; Geschiere, P.; Reid, G. Homophobic Africa? Toward a More Nuanced View. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2012, 55, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fu, H.; Kaminga, A.C.; Li, Z.; Guo, G.; Chen, L.; Li, Q. Prevalence of Depression or Depressive Symptoms among People Living with HIV/AIDS in China: A systematic Review and Meta Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, A. Out in Africa: LGBT Organizing in Namibia and South Africa; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, T.; German, D.; Kerrigan, D. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Sci. Med. 2013, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, A.; Hughes, T.L. Making the Invisible Visible: A Systematic Review of Sexual Minority Women’s Health in Southern Africa. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Valentine, D.D.; Duma, S.E. Transsexual Women’s Journey Towards a Heteronormative Health Care System: Gender and Equity. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2014, 20 (Suppl. S1), 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, G. Progress and Setbacks on LGBT Rights in Africa—An Overview of the Last Year. The Daily Maverick. 2022. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-06-22-progress-and-setbacks-on-lgbt-rights-in-africa-an-overview-of-the-last-year/ (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- Amnesty International. Africa: LGBTI People Face ‘Relentless’ Oppression After Surge in Discriminatory Laws—New Briefing. 2024. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/africa-lgbti-people-face-relentless-oppression-after-surge-discriminatory-laws-new (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Gamariel, F.; Isaakidis, P.; Tarquino, I.A.; Beirão, C.J.; O’Connell, L.; Mulieca, N.; Gatoma, H.P.; Cumbe, F.J.; Venables, E. Access to Health Services for Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Beira, Mozambique: A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0228307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Social Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors when Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A. Health for all? Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and the Implementation of Universal Health Coverage in South Africa. Health Human Rights J. 2017, 18, 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; Research Designs; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratele, K. The World Looks Like This from Here: Thoughts on African Psychology; Wits University Press: Ohannesburg, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, H.; Baral, S.D.; Trapence, G.; Motimedi, F.; Umar, E.; Iipinge, S.; Beyrer, C. Stigma, Health Care Access, and HIV Knowledge Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Malawi, Namibia, and Botswana. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Perez-Brumer, A.; Jenkinson, J.; Madau, V.; Nhlengethwa, W.; Baral, S. Marginalization and Social Change Processes among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons in Swaziland: Implications for HIV Prevention. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A.H.; Sandy, P.T. Religion-Related Stigma and Discrimination Experienced by Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Students at a South African Rural-Based University. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogotsi, I.; Otchere, Y.O.; Botchway, I.; Muthoni, Y.; Gariseb, R.; Ramalepe, L.M. Psychosocial correlates of LGBTIQ+ experiences in selected African countries: Reimagining LGBTIQ+ research. J. Soc. Issues 2024, 80, 1079–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; White Hughto, J.M.; Pardee, D.; Sevelius, J. Syndemics and Gender Affirmation: HIV Sexual Risk in Female-To-Male Trans Masculine Adults Reporting Sexual Contact with Cisgender Males. Int. J. STD AIDS 2016, 27, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Merwe, L.J.; Pienaar, A.J. Exploring the health care challenges faced by LGBTQI+ individuals in South Africa: A narrative review. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2020, 62, e1–e6. [Google Scholar]

- Ekine, S.; Abbas, H. Queer African Reader; Pambazuka Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, S.D.; Logie, C.H.; Grosso, A.; Wirtz, A.L.; Beyrer, C. Modified Social Ecological Model: A Tool to Guide the Assessment of the Risks and Risk Contexts of HIV Epidemics in Sexual and Gender Minorities. Glob. Public Health 2013, 8, 1215–1229. [Google Scholar]

- The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association. In State-Sponsored Homophobia Report 2020: Global Legislation Overview; International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Matebeni, Z.; Reddy, V.; Sandfort, T.; Southey-Swartz, I. Queer in Africa: LGBTQI Identities, Citizenship, and Activism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nyanzi, S. Dismantling Reified African Culture Through Localised Homosexualities in Uganda. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Aggleton, P. HIV and AIDS-related Stigma and Discrimination: A Conceptual Framework and Implications for Action. Social Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, M. Navigating the Intersections of Colonial Legacies and LGBT Lives. In Transnational LGBT Activism and UK-Based NGOs: Colonialism and Power; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 205–246. [Google Scholar]

- Meer, T.; Müller, A. “They Treat Us Like We’re not There”: Queer Bodies and the Social Production of Healthcare Spaces. Health Place 2017, 45, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mange, T.; Henderson, N.; Lukelelo, N. “After 25 Years of Democracy we Are Still Stigmatized and Discriminated Against…”: Health Care Experiences of HIV Positive Older Black Gay Men in a Township in South Africa. J. Pract. Teach. Learn. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morison, T.; Lynch, I. We Can’t Help You Here: The Discursive Erasure of Sexual Minorities in South African Public Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. Psychol. Sex. Rev. 2016, 7, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Luz Scherf, E.; Alves Lima Zanatta, M.d.L.; Viana da Silva, M.V.; Da Silva, J.E. Health Care Access by Transgender Persons in South Africa: Gender-Based Discrimination, Human Rights Violations, and The Role of the African Human Rights System. JHT 2022, 1, e1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulemfo, M.D.; Moyo, I.; Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A.H. LGBTQI+ Experiences of HIV Management Services at Primary Healthcare Facilities in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Adv. Public Health 2023, 2023, 1279409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhize, S.P.; Buthelezi, S.; Mkhize, A.M.; Tokwe, L. Beyond the Curriculum: A Gay Medical Student’s Perceptions of Health Sciences Education and Healthcare Access in KwaZulu-Natal. Health SA Gesondheid (Online) 2024, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamazima, S.R. Healthcare Seeking Behavior among Women Who Have Sex with Women in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: A Public Health Lens. EAS J. Nurs. Midwifery 2023, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.; Bristowe, K.; Chidyamatare, S.; Harding, R. ‘They will be Afraid to Touch You’: LGBTI People and Sex Workers’ Experiences of Accessing Healthcare in Zimbabwe—An In-depth Qualitative Study. BMJ Glob. Health 2017, 2, e000168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, S.; Meer, T.; Müller, A. “The Care is the Best You can Give at the Time”: Health Care Professionals’ Experiences in Providing Gender Affirming Care in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A. Health for All? Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and the Implementation of the Right to Access to Health Care in South Africa. Health Human Rights 2016, 18, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Nhamo-Murire, M.; Macleod, C.I. Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) People’s Experiences of Nursing Health Care: An Emancipatory Nursing Practice Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2018, 24, e12606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekola, A.P. An Intersectional Analysis of Gender-Specific Barriers to Adolescent Health Literacy in South Africa. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Gender Studies and Sexuality, Bangkok, Thailand, 19–20 September 2024; Volume 1, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Muranda, T.; Mugo, K.; Antonites, C. HIV is Not for Me: A Study of African Women who Have Sex with Women’s Perceptions of HIV/AIDS and Sexual Health: Focus: Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights and the African Women’s Protocol. Afr. Human Rights Law. J. 2014, 14, 757–786. [Google Scholar]

- Seretlo, R.J.; Smuts, H.; Mokgatle, M.M. Challenges in Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Access for Queer People in Gauteng, South Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2024, 16, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, A.V. Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) Students are Scrambling for Access to Healthcare Services in the Campus Healthcare System: Perceptions of Key Informants. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 2019, 33, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadele, G.; Amde, W.K. Health Needs, Health Care Seeking Behaviour, and Utilization of Health Services among Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A. Teaching Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health in a South African Health Sciences Faculty: Addressing the Gap. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiginton, J.M.; Murray, S.M.; Poku, O.; Augustinavicius, J.; Jackman, K.M.P.; Kane, J.; Baral, S.D. Disclosure of same-sex practices and experiences of healthcare stigma among cisgender men who have sex with men in five sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekoni, A.O. The Right to Health for the Lesbia, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Population in Nigeria—An Exploration of Access to, and Delivery of Healthcare Services. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.S.; Landes, S.J.; Willging, C.E.; Abraham, T.H.; McFrederick, P.; Kauth, M.R.; Shiperd, J.C.; Kirchner, J.E. Implementation of LGBTQ+ Affirming Care Policies in the Veterans Health Administration: Preliminary Findings on Barriers and Facilitators in the Southern United States. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1251565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Zarin, W.; Rios, P.; Nincic, V.; Khan, P.A.; Ghassemi, M.; Langlois, E.V. Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picozzi, M.; Pich, J.; Roberts, L. Language Barriers in Systematic Reviews: A Critical Review of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 94. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly Economic and Social Council. United Nations Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals Report of the Secretary-General; United Nations General Assembly Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).