Abstract

Associations between prenatal exposure to phthalates, bisphenols and their mixtures and early childhood allergic conditions and asthma were examined. Five hundred and fifty-six mother–child pairs from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort participated. Urine samples collected from mothers during the second trimester of pregnancy were analyzed for phthalates and bisphenols. A child health questionnaire, completed by mothers when children were 12, 24, and 36 months, asked whether children had experienced allergic conditions (i.e., food allergies, eczema, rash) or asthma. In single-chemical models, associations varied with child age. Higher prenatal concentrations of mono-benzyl phthalate (MBzP) were associated with lower odds of eczema at 12 months. At 36 months, higher mono-methyl phthalate (MMP) was associated with increased odds of eczema, whereas higher mono-carboxy-octyl phthalate (MCOP) was associated with reduced odds. Higher prenatal MCOP was also associated with higher odds of rash at 12 months, and higher MMP was associated with higher odds of rash at 36 months. Higher bisphenol S (BPS) was associated with increased odds of asthma at 12 months but decreased odds of eczema and rash at 36 months. Sex-specific effects were also noted. In multi-chemical exposure least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) models, several phthalate metabolites and BPS were selected as the best predictors of eczema and rash at 36 months of age. Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) mixture models suggested that BPS was the most important chemical in predicting eczema in children at 36 months, while MMP and BPS were the most important chemicals in predicting rash at 36 months. Prenatal exposure to certain phthalate metabolites and BPS predicted allergic conditions and asthma in young children, with patterns varying by age and sex. Prenatal exposure to these chemicals may differentially influence immune development and contribute to the development of early-life allergic conditions, with potentially sex-specific susceptibility.

1. Introduction

Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as phthalates and bisphenols is linked with increased risk of allergic conditions and asthma in children [1]. Phthalates are a group of chemicals commonly used as plasticizers in building materials, cosmetics, personal care products, medical equipment, toys and food packaging because of their flexibility, durability and resistant kinking properties [2]. Bisphenols serve as foundational building blocks to create hard, clear polycarbonate plastics and durable epoxy resins used in food and drink can linings, water bottles, electronics, and dental sealants [3]. These chemicals are ubiquitous in the environment and can leach from products into food, water, and dust, resulting in routine exposure through inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption through the skin [4,5].

A growing body of research suggests that EDCs may contribute to the increasing prevalence of allergic conditions and asthma in young children [1,6,7,8]. Both phthalates and bisphenols can cross the placental barrier and disrupt fetal endocrine development [9,10,11]. This could have consequences for integumentary and respiratory systems, including congestion and wheezing, shortness of breath, inflammation, and hives, redness, and itchiness, which are characteristics of allergies and asthma [12]. Over the past 30 years, the prevalence of these conditions has increased substantially in Canada. In Alberta, asthma prevalence increased from 3.9% to 12.3% in females and from 3.5% to 11.6% in males between 1995 and 2015 [13]. National data shows increases in self-reported allergies from 7.1% to 9.3% between 2010 and 2016 [14], and clinical data from Ontario indicate that the prevalence of eczema is greater among children (9.9%) than adults (1.8%) [15]. Furthermore, the overall prevalence of pediatric atopic dermatitis in Canada has been estimated to be 15.1% [16]. EDC exposure has been proposed as a potential contributor to these rising trends [17].

EDCs can influence immune and inflammatory pathways. Mechanistic evidence suggests that bisphenols can interact with estrogen receptors, triggering hormonal imbalances and pro-inflammatory signalling. Bisphenol A (BPA) can bind to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and toll-like receptors, disrupting the balance between immune cells, namely type 1 helper (Th1) cells, which are part of the pro-inflammatory pathways, and type 2 helper (Th2) cells, which regulate the anti-inflammatory response [18]. Prenatal phthalate exposure has been associated with reductions in regulatory T (Treg) cells, which are critical in immune response modulation [19] and may induce epigenetic changes, such as altered DNA methylation [20], which increase susceptibility to allergic disease and asthma later in life [21]. These findings support the hypothesis that prenatal exposure to EDCs may contribute to developmental programming of immune function and influence allergic and asthma outcomes across the lifespan [22,23].

Although previous epidemiological studies have examined associations between prenatal exposure to phthalates or bisphenols and childhood allergic and asthma outcomes, results remain inconsistent and often vary by child sex and timing of exposure assessment [24,25,26,27,28]. Few studies have evaluated which specific EDCs serve as the strongest predictors of these outcomes or considered the combined effects of EDC mixtures during fetal development [25,29,30].

To address these gaps, we examined associations between prenatal exposure to individual phthalates metabolites and BPA and Bisphenol S (BPS), as well as mixture effects of these targeted chemicals, and the development of allergic conditions and asthma in early childhood. Using data from a Canadian pregnancy cohort, we used multiple logistic regression analyses to examine the associations between the individual bisphenols and phthalate metabolites and each allergic and asthma disease outcome. We then applied least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to identify the best predictors of these associations [31] and Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) to assess mixture effects of phthalates and bisphenols [32].

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

This study drew on a subsample of maternal-child pairs (N = 556) from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort [33,34]. Participants were eligible if (1) the mother provided a second trimester urine sample that was quantified for BPA, BPS, and phthalate metabolites and (2) a child health questionnaire was completed by the mother at 12, 24, or 36 months of age.

2.2. Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary, Canada, and the University of Alberta Health Research Biomedical Panel, Edmonton, Canada. Written informed consent was provided by all the women prior to the completion of questionnaires and urine sample collection.

2.3. Exposure Assessment

2.3.1. Phthalates

Maternal urine samples collected in the second trimester of pregnancy (average gestational age = 17 weeks, standard deviation = 2.1) were analyzed at the Alberta Centre for Toxicology, University of Calgary for phthalate metabolites using previously described analytical methods [35,36]. Fourteen metabolites were measured: mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxy-hexyl) phthalate (MEHHP), mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate (MEOHP), mono(2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate (MECPP), mono-benzyl phthalate (MBzP), mono-carboxy-octyl phthalate (MCOP), mono-carboxy-isononyl phthalate (MCNP), and mono-isononyl phthalate (MNP), mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP), mono-iso-butyl phthalate (MiBP), mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP), mono-methyl phthalate (MMP), mono-cyclohexyl phthalate (MCHP), and mono-n-octyl phthalate (MOP). MCHP and MOP were excluded from the analyses due to low detection frequency (<50%).

The di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalates (DEHP), MECPP, MEHHP, MEOHP and MEHP were summed to obtain the molar concentration of ΣDEHP. The molar sum (nmol/mL) was calculated by dividing each metabolite concentration by its molecular weight and summing the resulting values.

Metabolites were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) (QTRAP 5500, AB Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada) operating in negative multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. An Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, LabX, Mississauga, ON, Canada), was used to separate the metabolites on a 100 Å ~ 2.1 mm BetaSil Phenyl Column (Thermo Scientific, Burlington, ON, Canada) with a 10 μL injection volume and a constant column temperature of 40 °C. Metabolites were identified based on two MRM transitions at the expected retention time. The limit of detection (LOD) for all phthalate metabolites was 0.10 μg/L. Consistent with recommended practice, values below the LOD were assigned the value of LOD/√2 [37].

2.3.2. Bisphenols

Second trimester maternal urine samples (mean gestational age = 17 weeks, standard deviation = 2.1 weeks) were analyzed for total (conjugated + free) bisphenol concentrations using previously described methods [35,38,39]. Briefly, metabolites were deconjugated by incubation with a mixture of β-glucuronidase and sulfatase. Total bisphenols were quantified using online solid-phase extraction coupled to HPLC-MS/MS and an Orbitrap Elite hybrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The LODs were 0.32 µg/mL for BPA and 0.10 µg/mL for BPS. Concentrations below the LOD were assigned values of LOD/√2 [37].

2.4. Outcome Assessment: Food Allergy, Eczema, Rash, and Asthma

Mothers completed an adapted version of the Child Health Questionnaire, a validated measure [40], when children were 12, 24, and 36 months of age. The questionnaire assessed common health conditions during the preceding 12 months, including food allergies, skin problems (e.g., rashes, eczema), and respiratory symptoms indicative of asthma (e.g., wheezing or whistling in the chest). Mothers reported whether their child had experienced each condition (yes/no) and could provide additional descriptive information. Child health outcomes were based exclusively on maternal report; no clinical assessments or medical records were available to validate parent-reported outcomes. Food allergy reports were interpreted according to the criteria for oral allergy syndrome [41,42,43]. Skin conditions, were coded as present if mothers reported eczema or dermatitis, including parent-reported diagnoses [42]. Reactions to irritants such as bug bites, chlorine or soaps were excluded due to their non-specific nature. Information on skin conditions was available only at the 12- and 36-month assessments. Asthma was coded as present if mothers reported asthma, use of a puffer, wheezing, difficult breathing or chronic cough [44].

2.5. Covariates

Potential confounders were identified a priori based on previous literature [8,24,25,45,46,47]. Maternal sociodemographic and biological covariates included educational attainment (university degree/postgraduate, high school/technical/trade school), marital status (married or cohabiting, single, divorced, separated or widowed), parity (0, 1, 2), household income (<$70,000, ≥$70,000), age at delivery (<25 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, ≥35 years), pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–30.0, >30 kg/m2). Child covariates included gestational age at birth (<37 gestational week, ≥37 gestational week), child sex (male, female). Maternal self-reported race was categorized as white or non-white. Urinary creatinine concentration was included to account for dilution variability in urinary phthalate metabolite and bisphenol measurements.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Concentrations of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols were natural log (ln) transformed to reduce the influence of extreme values and to improve interpretability, an approach commonly used in environmental exposure analyses [48]. We summarized sociodemographic characteristics using means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables, and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. The prevalence and incidence of each health outcome was calculated.

Multiple logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between the individual phthalate metabolites and bisphenols (i.e., single exposure models) and each allergic and asthma-related outcome. We calculated crude, adjusted, and sex-stratified odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Models were adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, race, household income, parity, child sex, gestational age at birth, and creatinine. Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05; borderline significance was identified as α = 0.10. To address multiple testing, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control for false discovery rate (FDR) at p < 0.05 [49].

Because birth weight has been associated with early childhood allergic conditions and asthma [50,51,52], we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding infants with low birth weight (<2500 g) and high birth weight (>4500 g).

To identify the chemical metabolites most predictive of each outcome, we first applied LASSO penalized regression [31,53,54] to all exposures (i.e., 12 phthalates, 2 bisphenols). LASSO simultaneously performs variable selection and shrinkage [31,55], which reduces the risk of overfitting and improves interpretability by yielding sparse models with more precise coefficient estimates [31]. Ten-fold cross-validation was used to select the optimal values of lambda (λ) corresponding with the minimum mean squared error (MSE) as recommended [56]. Metabolites with coefficients not shrunk to zero were retained as predictors. We then applied double LASSO logistic regression [57,58], including all 14 chemical exposures. Double LASSO corrects for LASSO’s shrinkage bias (if any) [58,59], improves predictive accuracy, and avoids over-selection of spurious predictors relative to linear, logistic, polynomial, or ridge regression [31,60]. It also reduces error as it does not over-select potentially spurious covariates, which increases the statistical power to identify the chemicals most predictive of allergic and asthma outcomes [57,58]. Statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported; for these analyses, borderline significance was identified as α = 0.10. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS Version 28 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA, 2019) and Stata Version 19.5 (Stata Corp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA).

We next evaluated mixture effects using BKMR, a non-parametric Bayesian variable selection method using the bkmr R package (version 4.4.0). BKMR was implemented using a probit link to accommodate binary outcomes (e.g., eczema vs. no eczema) using 20,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo iterations [61]. Exposures were grouped into group 1, phthalate metabolites (i.e., MMP, MEP, MBP, MiBP, MECPP, MEHHP, MEOHP, MEHP, MBzP, MCOP, MNP, MCNP) and group 2 bisphenols (i.e., BPA, BPS). For each group, we estimated posterior inclusion probabilities (group PIPs). Conditional PIPs were then calculated for the individual chemicals within each group. PIPs values range from 0 to 1, and a threshold of ≥0.5 was used to identify the groups or chemicals with meaningful inclusion probabilities [62,63].

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

Mother–child pairs (N = 556) were primarily white (86.2%). Average maternal age at delivery was 32 years (SD ± 3.94; range = 16.6 to 42.8 years). Most participants had a university education (72.8%) and were married or cohabiting with a partner (96.2%). Over half (55.4%) of the participants were first time mothers, with an average pre-pregnancy BMI of 24.7 (SD ± 5.1) kg/m2. Most of the children were born at or after 37 weeks’ gestation (92.6%), with an average birth weight of 3364.9 g (SD ± 538.6 g), and 51.4% were males (Table 1). Significant differences were observed between the study subsample and the original APrON cohort for some sociodemographic characteristics. The sociodemographic characteristics of the study population by sex of the child are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the APrON subsample included in the present study and the overall APrON cohort.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the APrON subsample included in the present study by sex of the child (N = 549; 7 missing information on child sex).

3.2. Maternal Chemical Exposures

Detection rates and distributions of the phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are presented in Table 3. Detection rates exceeded 98% for all phthalate metabolites, except for MCNP, which had a detection rate of 91%. Among the metabolites, MEP showed highest geometric mean urinary concentration (50.4 µg/L), whereas MCHP and MOP had the lowest geometric means (0.1 µg/L). For bisphenols, the detection rate was 92.3% for BPA and 58.6% for BPS.

Table 3.

Detection rates and distribution of maternal concentrations (µg/L) of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols in urine.

Spearman correlation coefficients for ln-transformed urinary concentrations of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are shown in Table S1. Overall, metabolites were positively correlated, with coefficients ranging from ρ = 0.14 to 0.98. As expected, the DEHP metabolites (i.e., MEOHP, MEHHP, MECPP, MEHP) were strongly intercorrelated (ρ ≥ 0.80 to 0.98, p < 0.05). The correlations between bisphenols and phthalate metabolites ranged from ρ = 0.18, p < 0.05 to ρ = 0.50, p < 0.05.

3.3. Prevalence and Incidence of Food Allergy, Eczema, Rash, and Asthma

The prevalence of food allergies was 7.2%, 18.5% and 28.1% at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively. Eczema prevalence was 18.9% at 12 months and increased to 35.4% at 36 months, while rash prevalence rose from 33.9% at 12 months to 61.1% at 36 months. Asthma prevalence was low but increased from 0.4% at 12 months to 1.9% at 24 months and 5.7% at 36 months (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence and incidence of food allergies, eczema, rash, and asthma at 12, 24, and 36 months.

Incidence patterns differed somewhat from prevalence. The incidence of food allergies increased from 7.2% at 12 months to 11.3% at 24 months but declined to 9.5% at 36 months. Incidence of eczema decreased from 18.9% at 12 months to 16.5% at 36 months, and rash incidence declined from 33.9% at 12 months to 27.1% at 36 months. In contrast, the incidence of asthma steadily increased with age from 0.4% at 12 months to 1.6% at 24 months and 3.9% at 36 months (see Table 4).

3.4. Associations Between Single Chemical Exposures and Maternal Reported Food Allergy, Eczema, Rash, and Asthma

In adjusted logistic regression models, prenatal phthalate exposures were not associated with food allergies at any age (Table 5). Higher maternal MBzP concentrations were associated with lower odds of eczema at 12 months (AOR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.97, p = 0.03) (Table 5). At 36 months, higher maternal MMP was associated with increased odds of eczema (AOR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.00–1.68, p = 0.04), whereas MCOP was associated with reduced odds (AOR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.64–0.96, p = 0.02). Higher prenatal MCOP was also associated with higher odds of rash at 12 months (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.03–1.41, p = 0.01), and higher MMP was associated with higher odds of rash at 36 months (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.08–1.69, p = 0.008). No associations were observed between prenatal phthalates and asthma.

Table 5.

Associations between maternal urinary concentrations of phthalates, and food allergies, eczema, rash and asthma at 12, 24, and 36 months. Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For bisphenols, higher prenatal BPS concentrations showed a trend for increased odds of asthma at 12 months (AOR 2.15, 95% CI = 0.88–5.23, p = 0.08), but reduced odds of eczema (AOR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.56–0.93, p = 0.01) and rash (AOR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.67–0.98, p = 0.03) at 36 months. Prenatal BPA concentrations were not associated with any outcomes (Table 6).

Table 6.

Associations between maternal urinary bisphenol concentrations and child food allergies, eczema, rash and asthma at 12, 24, and 36 months. Results are presented in adjusted odd ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for correction for multiple comparisons, none of the above associations remained statistically significant (adjusted p-value > 0.05).

3.5. Sex-Stratified Associations Between Single Chemical Exposures and Maternal Reported Food Allergy, Eczema, Rash, and Asthma

Among females, associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and allergic or asthma outcomes varied by age. At 24 months, prenatal MMP was associated with lower odds of food allergies (AOR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.36–0.93, p = 0.02), whereas at 36 months, MMP was associated with higher odds of food allergies (AOR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.06–2.42, p = 0.02). Higher prenatal MEP (AOR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.52–0.92, p = 0.01) and MiBP (AOR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41–0.95, p = 0.02) were associated with lower odds of eczema at 12 months; however, higher prenatal MCNP (AOR =1.25, 95% CI = 1.05–1.50, p = 0.01) and MBzP (AOR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.00–1.69, p = 0.04) were associated with increased odds of eczema. For rash, higher MEP (AOR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.61–0.95, p = 0.02) was protective at 12 months. At 36 months, higher MCOP (AOR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.06–0.90, p = 0.03) and MNP (AOR =0.38, 95% CI = 0.15–0.91, p = 0.03) were associated with lower odds of asthma (see Table S2).

In males, higher MBzP was associated with lower odds of rash (OR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.55–0.96, p = 0.02) and eczema (AOR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.46–0.92, p = 0.01) at 12 months, whereas higher MCOP was associated with higher odds of rash at the same age (AOR =1.34, 95% CI = 1.08–1.66, p = 0.007). At 36 months, higher prenatal MMP was associated with increased odds of eczema (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.02–2.12, p = 0.03) and rash (OR =1.45, 95% CI = 1.06–1.98, p = 0.02) (see Table S2).

For bisphenols, higher prenatal BPS was associated with lower odds of food allergy at 24 months in females (AOR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.39–1.04, p = 0.07) and at 36 months in males (AOR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.36–0.98, p = 0.04) (see Table S3). A trend association was noted between BPS and eczema in females at 36 months (AOR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.48–1.02, p = 0.06). In males, BPS displayed a trend association with asthma at 12 months (AOR = 3.24, 95% CI = 0.97–10.01, p = 0.05). BPA was not significantly associated with eczema, rash, or asthma in either males or females at any age.

After applying the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for correction for multiple comparisons, none of the above associations remained statistically significant (adjusted p-value > 0.05).

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

In a sensitivity analysis excluding infants with low and high birthweight (N = 46), all statistically significant associations in the adjusted logistic regression models remained significant, supporting the robustness of main findings.

3.7. Multiple Chemical Exposure Models

In the LASSO model for eczema at 36 months, MMP, MEP, MEHP, MECPP, MCOP, MCNP and BPS were selected as the best predictors, yielding an MSE of 0.0162 (Figure S1A). In the subsequent double LASSO logistic regression that included all phthalate metabolites and bisphenols, MMP was positively associated with eczema (AOR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.07–1.88, p = 0.01), whereas MCOP (AOR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.89, p = 0.006) and BPS (AOR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.57–0.93, p = 0.01) were inversely associated (Table 7).

Table 7.

Associations between prenatal phthalate metabolite and bisphenol concentrations and child eczema and rash at 36 months of age estimated using double LASSO regression. Results are presented as adjusted odd ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For rash at 36 months of age, the LASSO model selected MMP, MEHP, MEOHP, MCOP and BPS as the best predictors (MSE log λ = 0.0219; Figure S1B). The double LASSO logistic regression revealed positive associations for MMP (AOR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.11–1.81, p = 0.005) and MEHP (AOR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.11–2.00, p = 0.007), and inverse associations for MCOP (AOR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.69–0.98, p = 0.03) and BPS (AOR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.66–0.96, p = 0.01) (Table 7).

As LASSO models identified predictors of eczema and rash at 36 months, we conducted BKMR analyses to evaluate the joint and chemical group effects of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols on these outcomes. Tables S4 and S5 summarize the hierarchical variable selection results for group and conditional PIPs for eczema and rash, respectively

For eczema at 36 months, bisphenols demonstrated the highest group-level PIP (0.69), indicating a strong contribution of this chemical class, followed by phthalates with a moderate group PIP of 0.47. For rash at 36 months, both bisphenols and phthalates showed high group-level importance (bisphenols: PIP = 0.65; phthalates: PIP = 0.53; Table S5). Conditional PIPs within each chemical class were generally low (<0.20), but BPS consistently exhibited high conditional importance for both eczema (conditional PIP = 0.87) and rash (conditional PIP = 0.88). A moderate conditional PIP was observed for MMP in relation to rash (conditional PIP = 0.47) (Table S5).

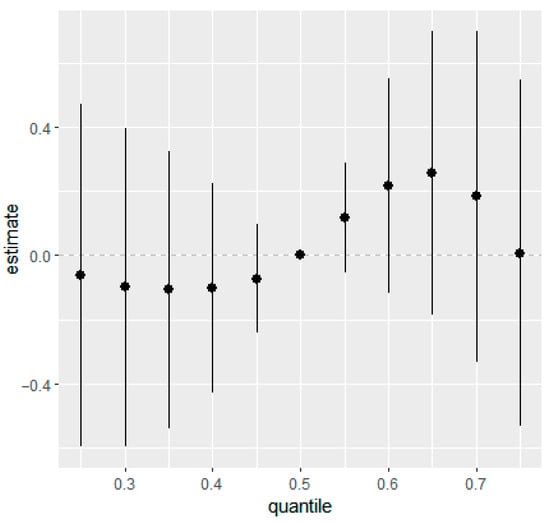

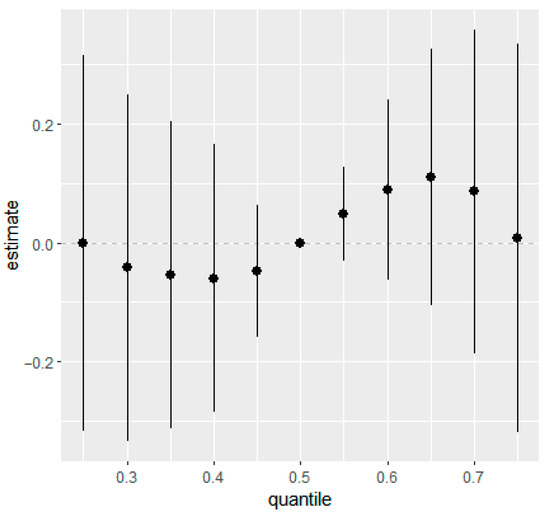

Sex-stratified BKMR model showed similar patterns. Among females, phthalates exhibited a group PIP of 0.64 for eczema, followed by bisphenols (group PIP = 0.49; Table S6). Among males, bisphenols had a group PIP of 0.68 for rash, while phthalates showed a lower group PIP of 0.40 (Table S7). Consistent with the overall models, BPS showed high conditional PIPs in both sex-stratified models, 0.72 for eczema in females and 0.80 for rash in males. MMP again showed a moderate conditional PIP for rash in males (conditional PIP = 0.30) (Table S7).

Univariate exposure–response functions demonstrated mostly weak associations across overall and sex-stratified BKMR models (Figures S2–S5). Each graph depicts the association between one natural log-transformed analyte and the outcome while holding all other exposures at their median values. The posterior mean estimates (blue lines) were generally close to the null, and 95% confidence intervals (grey shaded areas) were narrow to moderately wide, indicating varying but generally limited precision.

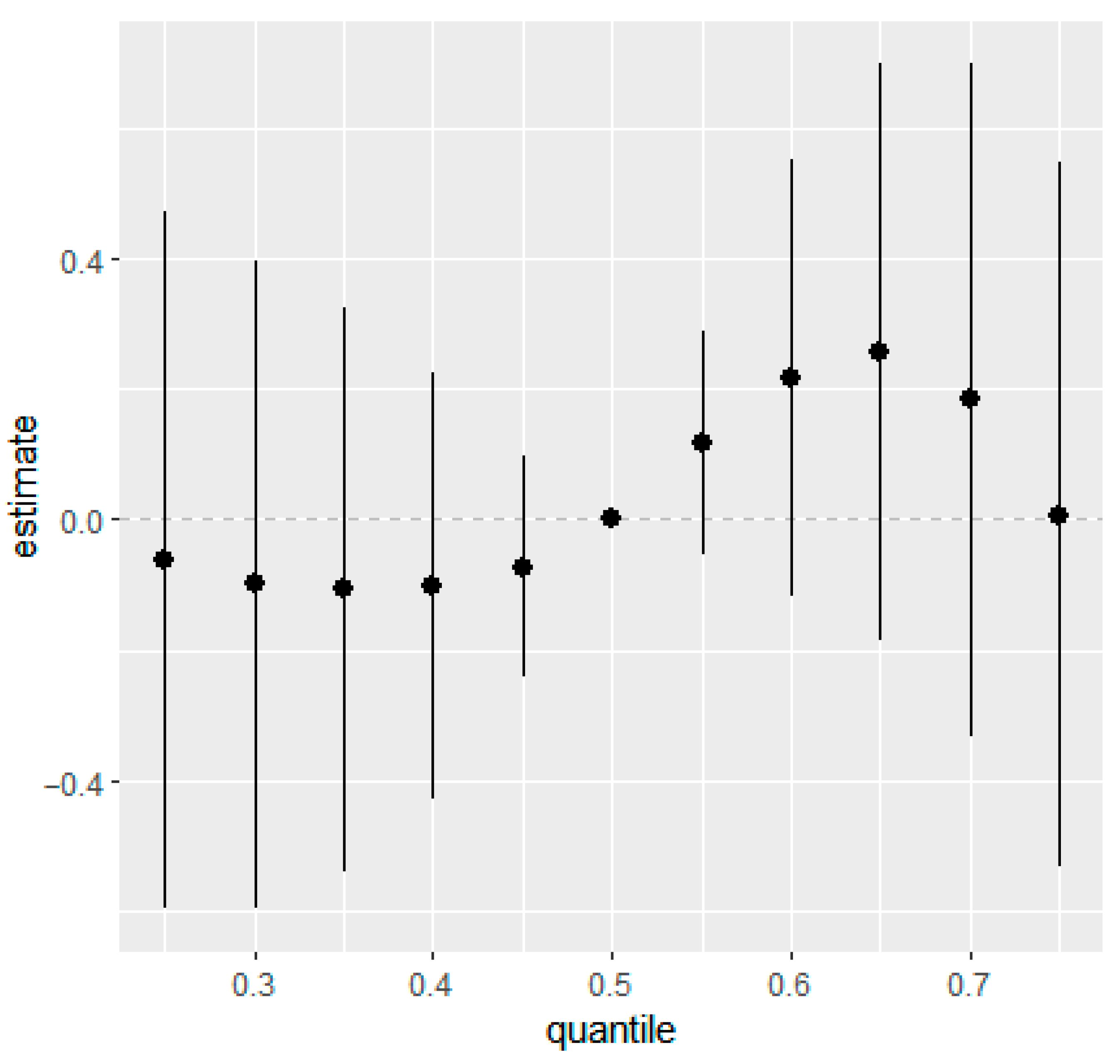

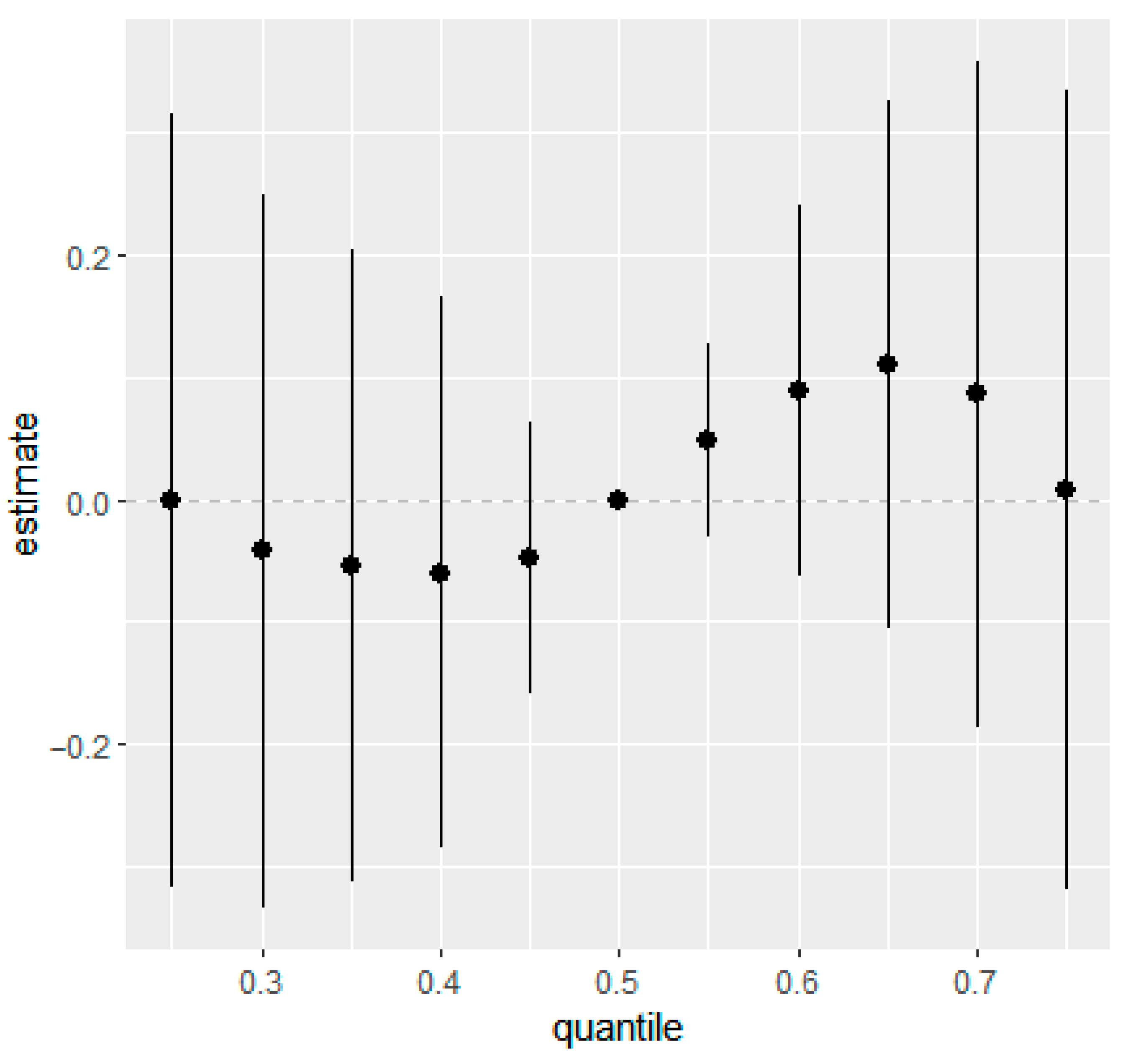

Similarly, overall mixture response functions showed week associations for eczema and rash at 36 months in the combined (Figure 1 and Figure 2) and the sex-stratified models (Figures S6 and S7). Posterior mean estimates of the change in outcome risk across quantiles of joint exposure mixture were close to zero at lower quantiles and displayed increasing trends only at higher quantiles (≥0.6). However, the 95% CIs were wide and generally overlapped zero, indicating substantial uncertainty and no statistically robust evidence of associations between higher prenatal mixture exposures and increased eczema or rash risk.

Figure 1.

Overall mixture effect (95% CIs) of prenatal phthalate and bisphenol exposure on eczema at 36 months of age estimated using BKMR. This plot illustrates the change in predicted probability of eczema when all ln-transformed analytes were set simultaneously to a given quantile for their distributions compared to when they are held at their median values. Adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, gestational age at birth, household income, parity, child sex, race, and creatinine.

Figure 2.

Overall mixture effect (95% CIs) of prenatal phthalate and bisphenol exposures on rash in children at 36 months of age estimated from BKMR. This plot illustrates the change in predicted probability of rash when all ln-transformed analytes were set simultaneously to a given quantile for their distributions compared to when they are held at their median values. Adjusted for maternal education, maternal age, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, marital status, gestational age at birth, household income, parity, child sex, race, and creatinine.

4. Discussion

In this prospective birth cohort, we found evidence that prenatal exposure to phthalate metabolites and BPS was associated with allergic conditions and asthma in early childhood. In single chemical models, higher prenatal concentrations of several phthalate metabolites (MMP, MBzP, MCOP) and BPS were associated with increased odds of eczema and rash at 36 months, and asthma at 12 months; however, these associations were attenuated after applying the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for correction for multiple comparisons. We also observed several sex-specific relationships. Among females, MMP, MEP and MiBP were associated with increased odds of food allergies at 24 months and lower odds of eczema and rash at 12 months, whereas MCNP and MBzP were linked to higher odds of eczema at 36 months. In addition, MCOP and MNP were associated with lower odds of asthma in females at 36 months. In males, MMP predicted higher odds of eczema and rash at 36 months of age, while MBzP was associated with lower odds of these outcomes at 12 months. Again, these findings were attenuated after correction for multiple comparisons. Findings from LASSO multi-chemical exposure models were consistent with single chemical analyses. In BKMR mixture models, BPS was the most influential contributor to eczema at 36 months, while MMP and BPS contributed most strongly to rash at the same age. Taken together, these results suggest that prenatal exposure to BPS and specific phthalate metabolites may differentially influence immune development and contribute to early life allergic conditions, with potential sex-specific susceptibility.

Epidemiological evidence supports links between prenatal exposure to phthalates and bisphenols and altered immune function, allergic conditions and asthma in children [24,25,26]. Prenatal exposure to phthalates has been associated with both early onset (0–24 months) and late onset (24–60 months) of eczema [8], and trimester-specific exposure has been linked to wheeze and asthma in males aged four to six years, highlighting potential sex-specific effects [26]. Findings for prenatal BPA exposure have been mixed, with some studies reporting no associations [25], and others reporting increased sex-specific risks of asthma, wheeze, eczema and food allergy [24,27,28]. Research assessing BPS is limited, but recent findings indicated that pregnancy averaged BPS was associated with increased odds of asthma in males [28].

Studies from the REPRO_PL cohort suggest that specific phthalate metabolites may influence allergic outcomes differently across developmental stages. For example, higher maternal MBzP was associated with increased risk of food allergy in children during the first two years of life [46], while higher MEHP predicted increased the risk at 9 years of age [64]. We did not observe associations between phthalate or bisphenol exposures and food allergy in the first three years of life.

Several international birth cohort studies from the USA, France, Greenland, and Ukraine have reported associations between phthalate metabolites (i.e., MBzP, MiBP, MCOP) and childhood eczema [8,65,66]. Cross-sectional evidence from South Korea similarly reported associations between MEP, MBzP, MCOP, MCNP, and DEHP metabolites, and atopic dermatitis in children [67]. Consistent with this literature, we observed a positive association between MMP and eczema at 36 months of age, an inverse association with MCOP at the same age, and a positive association with MBzP at 12 months. We also identified positive associations between MCOP and MMP and rash at 12 and 36 months. Contrary to prior studies reporting associations between prenatal exposure to BPA and eczema [45,68], we did not find evidence for BPA; instead, we observed an inverse association between BPS and eczema at 36 months.

Previous work has also identified MCOP as a predictor of asthma and reduced lung function at age seven [25], whereas our findings indicate that MCOP and MNP were protective against asthma in girls at 36 months. Biological mechanisms underlying these divergent findings remain unclear, but phthalates are known to interact with multiple immune pathways, suggesting the potential for both protective and adverse effects depending on dose, timing, and immunologic context. Research suggests that phthalates may alter cytokine production, reduce regulatory T-cell populations, and exert both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects [19,69,70], potentially leading to complex and chemical-specific patterns of immune disruption.

The concentrations of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols observed in the APrON cohort were consistent with levels reported in other North American populations [71] and are generally considered moderate on a global scale [64,65]. The concentrations were also comparable to those in European cohorts [8,46,72,73] but lower than levels reported in studies from China [2,54], likely reflecting differences in regulatory policies and industrial practices that affect the consumer products used by the general public, and community and workplace exposures.

Emerging evidence suggests that low-level exposure to certain phthalates may elicit a mild, adaptive immune response without triggering substantial inflammation; this could promote immune tolerance and potentially protect against allergic asthma in some cases [26,74]. For example, higher phthalate exposure in healthy adults has been associated with IL-6 levels, a cytokine typically involved in pro-inflammatory responses [69]. Similarly, recent work has shown that higher third-trimester exposure to phthalates such as DMP, DnBP, and DiBP was associated with decreased cord blood immune cell populations (e.g., IL-1β, IL-9, Th2, Treg), whereas another phthalate (i.e., DEP) was positively associated with the immune marker TNF-α [70]. Prenatal exposure to phthalates and bisphenols may also contribute to the development of allergic diseases and asthma by disrupting endocrine and immune pathways [75]. Phthalates can interfere with cytokine and chemokine production [76,77], reduce Treg cell levels [19], and potentially impair immune suppression necessary to prevent atopic dermatitis [78,79]. BPA may promote the production of IL-4 and other Th2-related cytokines, which may heighten allergic susceptibility [80]. Additionally, allergic disease expression may vary across childhood with changes in immune maturation, physical activity, environmental exposures, and metabolism [8,81]. The current body of evidence suggests that phthalate metabolites, BPA and BPS may influence immune pathways in distinct ways, which could contribute to both protective and adverse effects on the development of allergic disease. Further research is needed to elucidate underlying mechanisms and to determine how prenatal exposure to phthalates, bisphenols, and other EDCs contributes to allergic conditions and asthma in childhood.

Relatively few studies have examined mixtures of EDCs in relation to allergic conditions and asthma. CHAMACOS findings identified MCOP as a key contributor to asthma in BKMR models [25], while results from the Hokkaido cohort differed depending on analytic method, with MINP and MEOHP weighted heavily in weighted quantile sums (WQS) models and DINP and DEHP highlighted in BKMR model [30]. A case–control study from Taiwan found that MBzP, MiBP, and MiNP contributed most strongly to asthma in WQS analyses [29]. Our findings add to this emerging body of work by identifying MMP, MCOP and BPS as the most influential predictors of eczema and rash in LASSO models, and BPS and MMP as key contributors to eczema and rash in BKMR models at 36 months. Together, the mixed findings of these mixture analyses underscore the need for further investigations using multiple mixture analysis approaches to clarify the importance of individual chemicals in chemical mixtures.

This study has several strengths, including its prospective design and the availability of extensive prenatal and early-life covariates within the APrON cohort. The use of logistic regression, LASSO, double LASSO and BKMR enabled rigorous evaluation of both single-chemical and mixture effects. However, several limitations warrant consideration. Exposure assessment was based on a single second trimester urine sample, which may not fully capture exposure variability across pregnancy. Postnatal exposure was not measured, limiting our ability to examine combined prenatal and postnatal effects. Breast feeding data were incomplete, precluding evaluation of potential effect modification. Asthma outcomes were broadly defined, potentially inflating prevalence estimates and misclassification. The cohorts’ relatively high socioeconomic status and lack of clinical verification of allergic outcomes may limit generalizability. Finally, none of the overall associations in single chemical models remained statistically significant after correction for multiple comparison, raising the possibility of false positives and emphasizing the need for cautious interpretation.

5. Conclusions

Prenatal exposure to certain phthalate metabolites and BPS may be associated with allergic conditions and asthma in young children, with patterns varying by age and sex. Single-chemical models identified MMP, MBzP, MCOP and BPS as predictors of eczema, rash, and asthma, while mixture analyses highlighted BPS and MMP as the most influential contributors to eczema and rash at 36 months. These findings suggest that BPS and selected phthalate metabolites may disrupt early-life immune development and contribute to allergic outcomes. Future research should incorporate repeated prenatal measurement of exposures and postnatal exposure data and examine sex-specific effects to clarify exposure timing, susceptibility windows, and the influence of sex on the development of allergic conditions and asthma in children.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22121875/s1, Figure S1: LASSO variable trace plots illustrating the coefficient trajectories of phthalate metabolites and bisphenols. The x-axis represents the sum of the absolute values of the penalized coefficients (the L1-norm). Each line shows the penalized coefficient path for one standardized variable in the model. The vertical red line marks the value of lambda (λ) selected through cross-validation; Figure S2: Univariate exposure–response functions of natural log (ln) transformed prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols and eczema in children at 36 months of age. Associations between each analyte and maternal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are plotted while fixing the other analytes at their 50th percentile (95% CI are shown in grey); Figure S3: Univariate exposure–response functions of natural log (ln) transformed prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols and rash in children at 36 months of age. Associations between each analyte and maternal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are plotted while fixing the other analytes at their 50th percentile (95% CI are shown in grey); Figure S4: Univariate exposure–response functions of natural log (ln) transformed prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols and eczema in females at 36 months of age. Associations between each analyte and maternal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are plotted while fixing the other analytes at their 50th percentile (95% CI are shown in grey); Figure S5: Univariate exposure–response functions of natural log (ln) transformed prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols and rash in males at 36 months of age. Associations between each analyte and maternal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols are plotted while fixing the other analytes at their 50th percentile (95% CI are shown in grey); Figure S6: Overall mixture effect (95% CIs) of prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols for eczema in females at 36 months of age using BKMR. This plot illustrated the change in predicted probability of eczema in females when all the ln-transformed analytes are at the respective quantile compared to when they are held at their median values; Figure S7: Overall mixture effect (95% CIs) of prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols for rash in males at 36 months of age estimated using BKMR. This plot illustrated the change in predicted probability of rash in males when all the ln-transformed analytes are at the respective quantile compared to when they are held at their median values; Table S1: Spearman correlations between the environmental chemicals; Table S2: Adjusted sex-stratified associations between maternal urinary concentrations of each phthalate metabolite, and food allergies, eczema, rash and asthma. Results are presented as adjusted odd ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs); Table S3: Adjusted sex-stratified associations between maternal urinary concentrations of BPA and BPS, and food allergies, eczema, rash and asthma. Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs); Table S4: Posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) for prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols in the Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model assessing eczema in children at 36 months of age; Table S5: Posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) for prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols in the Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model assessing rash in children at 36 months of age; Table S6: Posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) for prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols in the Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model assessing eczema in females at 36 months of age; Table S7: Posterior inclusion probabilities (PIPs) for prenatal phthalate metabolites and bisphenols in the Bayesian kernel machine regression (BKMR) model assessing rash in males at 36 months of age.

Author Contributions

D.D. and M.H.S. had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: E.B., D.D. and M.H.S.; Acquisition: E.B., G.E.-M., J.W.M., A.M.M., D.W.K., D.D. and M.H.S. Analysis and interpretation of data: E.B., G.E.-M., J.W.M., A.M.M., D.W.K., D.D. and M.H.S.; Drafting of the manuscript: E.B.; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: E.B., G.E.-M., J.W.M., A.M.M., D.W.K., D.D. and M.H.S. Statistical analysis: E.B., D.D. and M.H.S.; Funding: D.D. and J.W.M.; Administrative, technical, or material support; E.B., G.E.-M., J.W.M., A.M.M., D.W.K., D.D. and M.H.S. Supervision: D.D. and M.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APrON cohort was established by an interdisciplinary team grant from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (formally the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research). Additional funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-1106593 and MOP-123535), the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Exploration/Development Grant 1R21ES021295-01R21) and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation allowed for the collection and analysis of data presented in this manuscript. Postdoctoral salary support was provided to M.H. Soomro through a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant (PG-201909) awarded to D. Dewey and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. G. England-Mason received salary support through a Postgraduate Fellowship in Health Innovation provided by Alberta Innovates, the Ministry of Economic Development, Trade and Tourism, and the Government of Alberta, and a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HTA-472411). The funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary, Canada (Ethics ID: REB14-1702, initial approval date 15 January 2009) and the University of Alberta Health Research Biomedical Panel, Edmonton, Canada (Study ID: Pro00002954, initial approval date 12 February 2009), for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was provided by all the women prior to the completion of questionnaires and urine sample collection.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the APrON study (https://apronstudy.ca) upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study and the whole APrON team, including the investigators, research assistants, graduate and undergraduate students. We acknowledge the significant contributions of the APrON Study Team whose individual members are B.J. Kaplan, C.J. Field, R.C. Bell, F.P. Bernier, M. Cantell, L.M. Casey, M. Eliasziw, A. Farmer, L. Gagnon, G.F. Giesbrecht, L. Goonewardene, D. Johnston, L. Kooistra, N. Letourneau, D.P. Manca, J.W. Martin, L.J. McCargar, M. O’Beirne, V.J. Pop, A.J. Deane, and N. Singhal, and the APrON Management Team, including N. Letourneau (current PI), R.C. Bell, D. Dewey, C.J. Field, L. Forbes, G. Giesbrecht, C. Lebel, B. Leung, C. McMorris, and K. Ross. The APrON cohort was established by an interdisciplinary team grant from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (formally the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| APrON | Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition |

| BKMR | Bayesian kernel machine regression |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| BPS | Bisphenol S |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DEHP | Di (2- ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| ΣDEHP | Molar sum of DEHP metabolites |

| GM | Geometric mean |

| HPLC-MS/MS | High-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| EDCs | Endocrine disrupting chemicals |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| MBP | Mono-n-butyl phthalate |

| MBzP | Monobenzyl phthalate |

| MCHP | Mono-cyclohexyl phthalate |

| MCNP | Monocarboxy-isononyl phthalate |

| MCOP | Monocarboxy-isooctyl phthalate |

| MECPP | Mono (2-ethyl-5-carboxypentyl) phthalate |

| MEHHP | Mono (2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate |

| MEOHP | Mono (2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) phthalate |

| MEHP | Mono (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| MEP | Monoethyl phthalate |

| MiBP | Mono-isobutyl phthalate |

| MMP | Mono-methyl phthalate |

| MNP | Mono-isononyl phthalate |

| MOP | Mono-n-octyl phthalate |

| MRM | Multiple reaction monitoring |

| MSE | Mean squared error |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PIPs | Posterior inclusion probabilities |

| PPARs | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors |

| Th1 | Type 1 helper |

| Th2 | Type 2 helper |

| T | Treg |

| WQS | Weighted quantile sums |

References

- Kim, E.H.; Jeon, B.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.M.; Han, Y.; Ahn, K.; Cheong, H.K. Exposure to phthalates and bisphenol A are associated with atopic dermatitis symptoms in children: A time-series analysis. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, H. Phthalates and Their Impacts on Human Health. Healthcare 2021, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorchilot, V.S.; Louis, H.; Haridas, A.; Praveena, P.; Arya, S.B.; Nair, A.S.; Aravind, U.K.; Aravindakumar, C.T. Bisphenols in indoor dust: A comprehensive review of global distribution, exposure risks, transformation, and biomonitoring. Chemosphere 2025, 370, 143798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: An Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, E1–E150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. Influences of Environmental Chemicals on Atopic Dermatitis. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 31, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanovic, N.; Irvine, A.D.; Flohr, C. The Role of the Environment and Exposome in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2021, 8, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, M.H.; Baiz, N.; Philippat, C.; Vernet, C.; Siroux, V.; Nichole Maesano, C.; Sanyal, S.; Slama, R.; Bornehag, C.G. Annesi-Maesano I: Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates and the Development of Eczema Phenotypes in Male Children: Results from the EDEN Mother-Child Cohort Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 027002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Henare, K.; Thorstensen, E.B.; Ponnampalam, A.P.; Mitchell, M.D. Transfer of bisphenol A across the human placenta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 393 e391–e397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, M.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Chen, B.; Dong, R. Meconium Exposure to Phthalates, Sex and Thyroid Hormones, Birth Size and Pregnancy Outcomes in 251 Mother-Infant Pairs from Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikantami, I.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Alegakis, A.K.; Karzi, V.; Hatzidaki, E.; Stavroulaki, A.; Vakonaki, E.; Xezonaki, P.; Sifakis, S.; Rizos, A.K.; et al. Phthalate metabolites concentrations in amniotic fluid and maternal urine: Cumulative exposure and risk assessment. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.A. JAMA Pediatrics Patient Page. Atopic Diseases in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bosonea, A.M.; Sharpe, H.; Wang, T.; Bakal, J.A.; Befus, A.D.; Svenson, L.W.; Vliagoftis, H. Developments in asthma incidence and prevalence in Alberta between 1995 and 2015. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.E.; Elliott, S.J.; St Pierre, Y.; Soller, L.; La Vieille, S.; Ben-Shoshan, M. Temporal trends in prevalence of food allergy in Canada. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1428–1430.E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, A.M.; Bai, L.; Eder, L.; Chan, A.W.; Pope, E.; Tu, K.; Jaakkimainen, L. Sociodemographic characteristics and emergency department visits and inpatient hospitalizations for atopic dermatitis in Ontario: A cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open 2022, 10, E491–E499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Barbarot, S.; Gadkari, A.; Simpson, E.L.; Weidinger, S.; Mina-Osorio, P.; Rossi, A.B.; Brignoli, L.; Saba, G.; Guillemin, I.; et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 417–428.E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.N.; Hsieh, C.C.; Kuo, H.F.; Lee, M.S.; Huang, M.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Hung, C.H. The effects of environmental toxins on allergic inflammation. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2014, 6, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Huang, G.; Guo, T.L. Developmental Bisphenol A Exposure Modulates Immune-Related Diseases. Toxics 2016, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberth, G.; Pierzchalski, A.; Feltens, R.; Bauer, M.; Roder, S.; Olek, S.; Hinz, D.; Borte, M.; von Bergen, M.; Lehmann, I.; et al. Prenatal phthalate exposure associates with low regulatory T-cell numbers and atopic dermatitis in early childhood: Results from the LINA mother-child study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1376–1379.E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England-Mason, G.; Merrill, S.M.; Gladish, N.; Moore, S.R.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Letourneau, N.; MacIsaac, J.L.; MacDonald, A.M.; Kinniburgh, D.W.; Ponsonby, A.L.; et al. Prenatal exposure to phthalates and peripheral blood and buccal epithelial DNA methylation in infants: An epigenome-wide association study. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahreis, S.; Trump, S.; Bauer, M.; Bauer, T.; Thurmann, L.; Feltens, R.; Wang, Q.; Gu, L.; Grutzmann, K.; Roder, S.; et al. Maternal phthalate exposure promotes allergic airway inflammation over 2 generations through epigenetic modifications. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, H.X.; Yan, H.Y.; Wu, D.M.; Ping, J. Developmental origins of inflammatory and immune diseases. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 22, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Miller, R. The Impact of Bisphenol A and Phthalates on Allergy, Asthma, and Immune Function: A Review of Latest Findings. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.; Chang, H.; Huo, W.; Zhang, B.; Hu, J.; Xia, W.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and risk of allergic diseases in early life. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, K.; Coker, E.; Rauch, S.; Eskenazi, B.; Balmes, J.; Kogut, K.; Holland, N.; Calafat, A.M.; Harley, K. Prenatal phthalate, paraben, and phenol exposure and childhood allergic and respiratory outcomes: Evaluating exposure to chemical mixtures. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adgent, M.A.; Carroll, K.N.; Hazlehurst, M.F.; Loftus, C.T.; Szpiro, A.A.; Karr, C.J.; Barrett, E.S.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Bush, N.R.; Tylavsky, F.A.; et al. A combined cohort analysis of prenatal exposure to phthalate mixtures and childhood asthma. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.P.; Quiros-Alcala, L.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Calafat, A.M.; Wolff, M.S.; Engel, S.M. Associations of prenatal environmental phenol and phthalate biomarkers with respiratory and allergic diseases among children aged 6 and 7 years. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaylord, A.; Barrett, E.S.; Sathyanarayana, S.; Swan, S.H.; Nguyen, R.H.N.; Bush, N.R.; Carroll, K.; Day, D.B.; Kannan, K.; Trasande, L. Prenatal bisphenol A and S exposure and atopic disease phenotypes at age 6. Environ. Res. 2023, 226, 115630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.W.; Chen, H.C.; Hu, H.Z.; Chang, W.T.; Huang, P.C.; Wang, I.J. Phthalate Exposure and Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress in Childhood Asthma: A Nested Case-Control Study with Propensity Score Matching. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketema, R.M.; Ait Bamai, Y.; Miyashita, C.; Saito, T.; Kishi, R.; Ikeda-Araki, A. Phthalates mixture on allergies and oxidative stress biomarkers among children: The Hokkaido study. Environ. Int. 2022, 160, 107083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1996, 58, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobb, J.F.; Valeri, L.; Claus Henn, B.; Christiani, D.C.; Wright, R.O.; Mazumdar, M.; Godleski, J.J.; Coull, B.A. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 2015, 16, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, B.J.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Leung, B.M.; Field, C.J.; Dewey, D.; Bell, R.C.; Manca, D.P.; O’Beirne, M.; Johnston, D.W.; Pop, V.J.; et al. The Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort study: Rationale and methods. Matern. Child Nutr. 2014, 10, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, N.; Aghajafari, F.; Bell, R.C.; Deane, A.J.; Dewey, D.; Field, C.; Giesbrecht, G.; Kaplan, B.; Leung, B.; Ntanda, H.; et al. The Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) longitudinal study: Cohort profile and key findings from the first three years. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, M.H.; England-Mason, G.; Liu, J.; Reardon, A.J.F.; MacDonald, A.M.; Kinniburgh, D.W.; Martin, J.W.; Dewey, D.; APrON Study Team. Associations between the chemical exposome and pregnancy induced hypertension. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England-Mason, G.; Martin, J.W.; MacDonald, A.; Kinniburgh, D.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Letourneau, N.; Dewey, D. Similar names, different results: Consistency of the associations between prenatal exposure to phthalates and parent-ratings of behavior problems in preschool children. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornung, R.W.; Reed, L.D. Estimation of average concentration in the presence of non-detectable values. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 1990, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Martin, L.J.; Dinu, I.; Field, C.J.; Dewey, D.; Martin, J.W. Interaction of prenatal bisphenols, maternal nutrients, and toxic metal exposures on neurodevelopment of 2-year-olds in the APrON cohort. Environ. Int. 2021, 155, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England-Mason, G.; Liu, J.; Martin, J.W.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Letourneau, N.; Dewey, D.; APrON Study Team. Postnatal BPA is associated with increasing executive function difficulties in preschool children. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, J.; Abetz, L.; Ware, J., Jr. The Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User’s Manual; Health Act CHQ: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovic-Jurekovic, I. Oral allergy syndrome in children. Int. Dent. J. 2015, 65, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrorilli, C.; Caffarelli, C.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: Prediction, progression, and prevention. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 28, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala, O.I.; Choudhary, S.K.; Commins, S.P. Food Allergy. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froidure, A.; Mouthuy, J.; Durham, S.R.; Chanez, P.; Sibille, Y.; Pilette, C. Asthma phenotypes and IgE responses. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 47, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, S.K.; Park, H.; Lee, W.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, Y.C.; Ha, M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, B.E.; Ha, E. Joint association of prenatal bisphenol-A and phthalates exposure with risk of atopic dermatitis in 6-month-old infants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmach, I.; Majak, P.; Jerzynska, J.; Podlecka, D.; Stelmach, W.; Polanska, K.; Ligocka, D.; Hanke, W. The effect of prenatal exposure to phthalates on food allergy and early eczema in inner-city children. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015, 36, e72–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, N.Y.; Lee, C.C.; Wang, J.Y.; Li, Y.C.; Chang, H.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Bornehag, C.G.; Wu, P.C.; Sundell, J.; Su, H.J. Predicted risk of childhood allergy, asthma, and reported symptoms using measured phthalate exposure in dust and urine. Indoor Air 2011, 22, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D.B.; Wilder, L.C.; Caudill, S.P.; Gonzalez, A.J.; Needham, L.L.; Pirkle, J.L. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: Implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, A.; Cichocka-Jarosz, E.; Kwinta, P. Atopic dermatitis and gestational age—Is there an association between them? A review of the literature and an analysis of pathology. Postep. Dermatol. I Alergol. 2023, 40, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooldridge, A.L.; McMillan, M.; Kaur, M.; Giles, L.C.; Marshall, H.S.; Gatford, K.L. Relationship between birth weight or fetal growth rate and postnatal allergy: A systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loid, P.; Goksor, E.; Alm, B.; Pettersson, R.; Mollborg, P.; Erdes, L.; Aberg, N.; Wennergren, G. A persistently high body mass index increases the risk of atopic asthma at school age. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrico, C.; Gennings, C.; Wheeler, D.C.; Factor-Litvak, P. Characterization of Weighted Quantile Sum Regression for Highly Correlated Data in a Risk Analysis Setting. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2015, 20, 100–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Sze-Yin Leung, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Y. Mixed exposure to phthalates and organic UV filters affects Children’s pubertal development in a gender-specific manner. Chemosphere 2023, 320, 138073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, N.; Barnett, A.G.; Sly, P.D.; Knibbs, L.D. Statistical Methodology in Studies of Prenatal Exposure to Mixtures of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: A Review of Existing Approaches and New Alternatives. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 26001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.; Nowak, G. Stabilizing the lasso against cross-validation variability. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2014, 70, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urminsky, O.; Hansen, C.; Chernozhukov, V. The Double-Lasso Method for Principled Variable Selection. PsyArXiv 2019, 2019, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Shi, Z.; Gao, Z. On LASSO for predictive pregression. J. Econom. 2022, 229, 322–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloni, A.; Chernozhukov, V.; Hansen, C. Inference on treatment effects after selection among high-dimentional controls. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2014, 81, 608–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEligot, A.J.; Poynor, V.; Sharma, R.; Panangadan, A. Logistic LASSO Regression for Dietary Intakes and Breast Cancer. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobb, J.F.; Claus Henn, B.; Valeri, L.; Coull, B.A. Statistical software for analyzing the health effects of multiple concurrent exposures via Bayesian kernel machine regression. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, E.; Chevrier, J.; Rauch, S.; Bradman, A.; Obida, M.; Crause, M.; Bornman, R.; Eskenazi, B. Association between prenatal exposure to multiple insecticides and child body weight and body composition in the VHEMBE South African birth cohort. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, M.M.; Berger, J.O. Optimal predictive model selection. Ann. Stat. 2004, 32, 870–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlecka, D.; Gromadzinska, J.; Mikolajewska, K.; Fijalkowska, B.; Stelmach, I.; Jerzynska, J. Longitudinal effect of phthalates exposure on allergic diseases in children. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 125, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, L.A.M.; Lenters, V.; Hoyer, B.B.; Lindh, C.H.; Pedersen, H.S.; Liermontova, I.; Jonsson, B.A.; Piersma, A.H.; Bonde, J.P.; Toft, G.; et al. Prenatal exposure to environmental chemical contaminants and asthma and eczema in school-age children. Allergy 2015, 70, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, A.C.; Whyatt, R.M.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Calafat, A.M.; Perera, F.P.; Goldstein, I.F.; Chen, Q.; Rundle, A.G.; Miller, R.L. Prenatal exposure to butylbenzyl phthalate and early eczema in an urban cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1475–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Huh, D.A.; Moon, K.W. Association between environmental exposure to phthalates and allergic disorders in Korean children: Korean National Environmental Health Survey (KoNEHS) 2015–2017. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2021, 238, 113857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Wu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.S.; Tian, F.L.; Sun, Q.; Wei, W.; Cao, X.; Jia, L.H. Prenatal exposure to bisphenols, immune responses in cord blood and infantile eczema: A nested prospective cohort study in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 112987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, U.C.; Ulriksen, E.S.; Hjertholm, H.; Sonnet, F.; Bolling, A.K.; Andreassen, M.; Husoy, T.; Dirven, H. Immune cell profiles associated with measured exposure to phthalates in the Norwegian EuroMix biomonitoring study—A mass cytometry approach in toxicology. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, A.; Gao, Y.; Collier, F.; Drummond, K.; Thomson, S.; Burgner, D.; Vuillermin, P.; Tang, M.L.; Mueller, J.; Symeonides, C.; et al. Cord blood immune profile: Associations with higher prenatal plastic chemical levels. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, T.E.; Davis, K.; Marro, L.; Fisher, M.; Legrand, M.; LeBlanc, A.; Gaudreau, E.; Foster, W.G.; Choeurng, V.; Fraser, W.D. Phthalate and bisphenol A exposure among pregnant women in Canada—Results from the MIREC study. Environ. Int. 2014, 68, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Casas, M.; Morales, E.; Valvi, D.; Ballesteros-Gomez, A.; Luque, N.; Rubio, S.; Monfort, N.; Ventura, R.; Martinez, D.; et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and phthalates and childhood respiratory tract infections and allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen, R.J.; Carlsen, K.C.; Calafat, A.M.; Hoppin, J.A.; Haland, G.; Mowinckel, P.; Carlsen, K.H.; Lovik, M. Urinary biomarkers for phthalates associated with asthma in Norwegian children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, D.; Marques, C.; Pestana, D.; Faria, A.; Norberto, S.; Calhau, C.; Monteiro, R. Effects of xenoestrogens in human M1 and M2 macrophage migration, cytokine release, and estrogen-related signaling pathways. Environ. Toxicol. 2016, 31, 1496–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, A.; Henao-Mejia, J.; Simmons, R.A. Immune System: An Emerging Player in Mediating Effects of Endocrine Disruptors on Metabolic Health. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, J.; Iwahara, C.; Kawasaki, M.; Yoshizaki, F.; Nakayama, H.; Takamori, K.; Ogawa, H.; Iwabuchi, K. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces production of inflammatory molecules in human macrophages. Inflamm. Res. 2012, 61, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, S.; Roediger, B.; Abtin, A.; Shklovskaya, E.; Fazekas de St Groth, B.; Yamane, H.; Weninger, W.; Le Gros, G.; Ronchese, F. CD326(lo)CD103(lo)CD11b(lo) dermal dendritic cells are activated by thymic stromal lymphopoietin during contact sensitization in mice. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 2504–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Chatila, T.A. Regulatory T cells in allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Barlow, J.L.; Saunders, S.P.; Xue, L.; Gutowska-Owsiak, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.C.; Johnson, D.; Scanlon, S.T.; McKenzie, A.N.; et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2939–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Takamoto, M.; Sugane, K. Exposure to Bisphenol A prenatally or in adulthood promotes T(H)2 cytokine production associated with reduction of CD4CD25 regulatory T cells. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byberg, K.K.; Eide, G.E.; Forman, M.R.; Juliusson, P.B.; Oymar, K. Body mass index and physical activity in early childhood are associated with atopic sensitization, atopic dermatitis and asthma in later childhood. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2016, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).