Perceptions of Health in the Denver Refugee Community: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

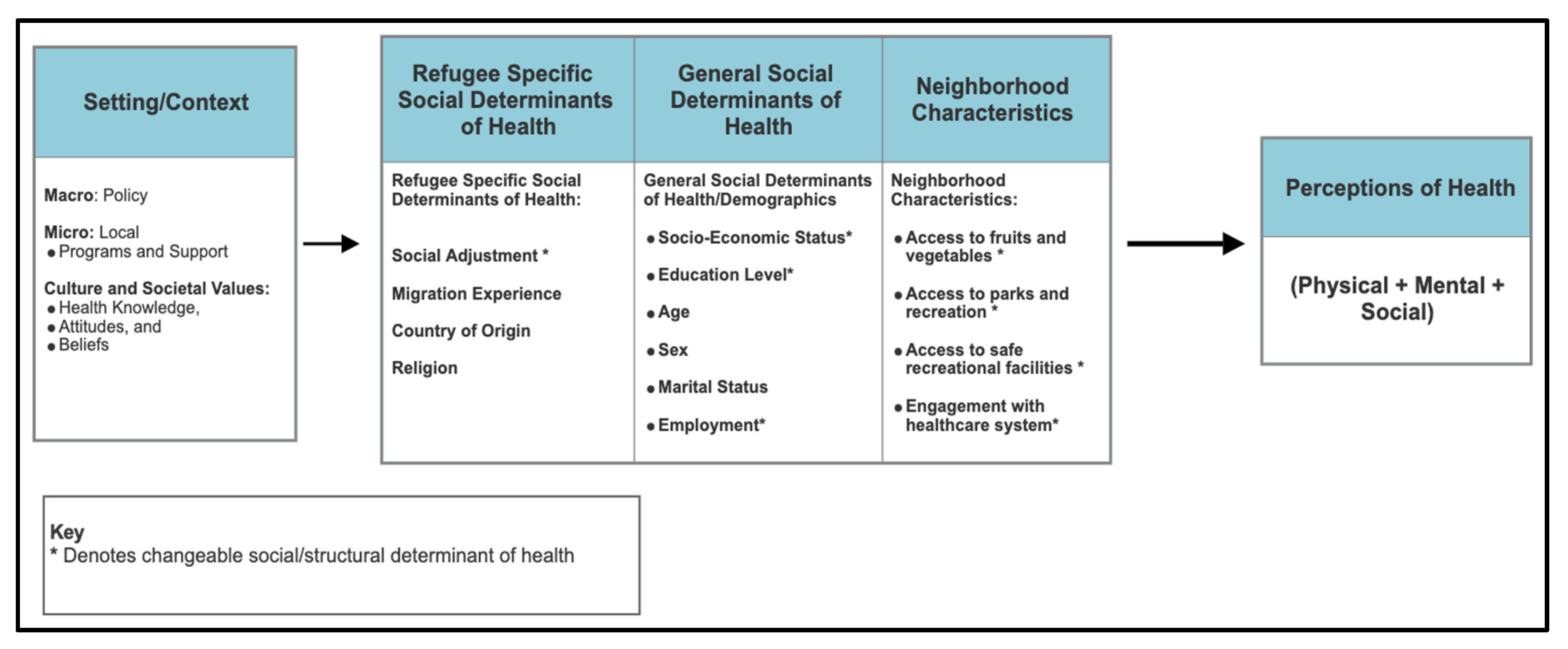

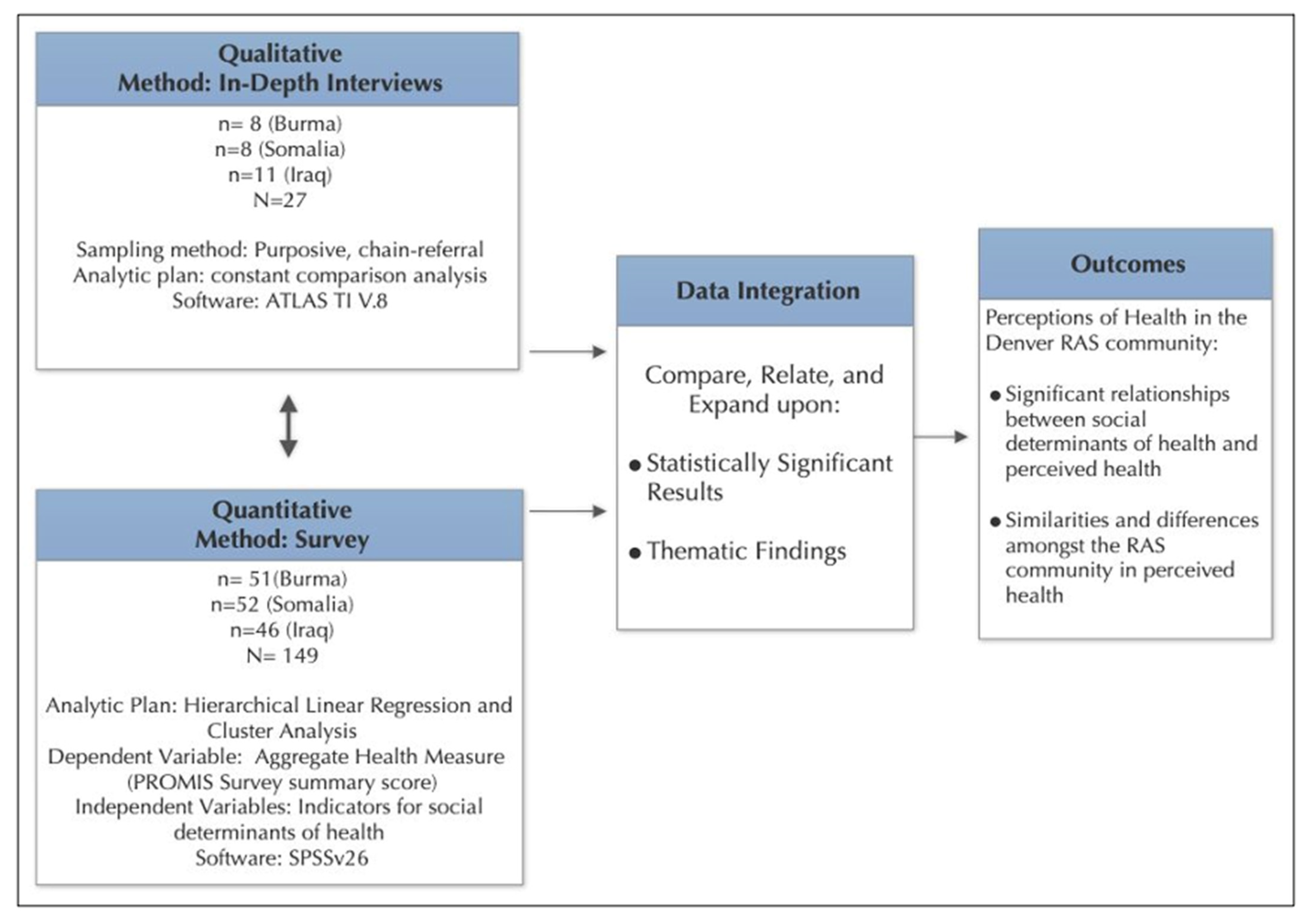

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Community-Based Research Network (CBRN)

2.3. Quantitative Methods

2.3.1. Recruitment and Survey Administration

2.3.2. Dependent Variable

2.3.3. Independent Variables

2.3.4. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Methods

2.4.1. Interview Design and Procedures

2.4.2. Interview Sampling and Participants

2.4.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.5. Integration of Methods

3. Results

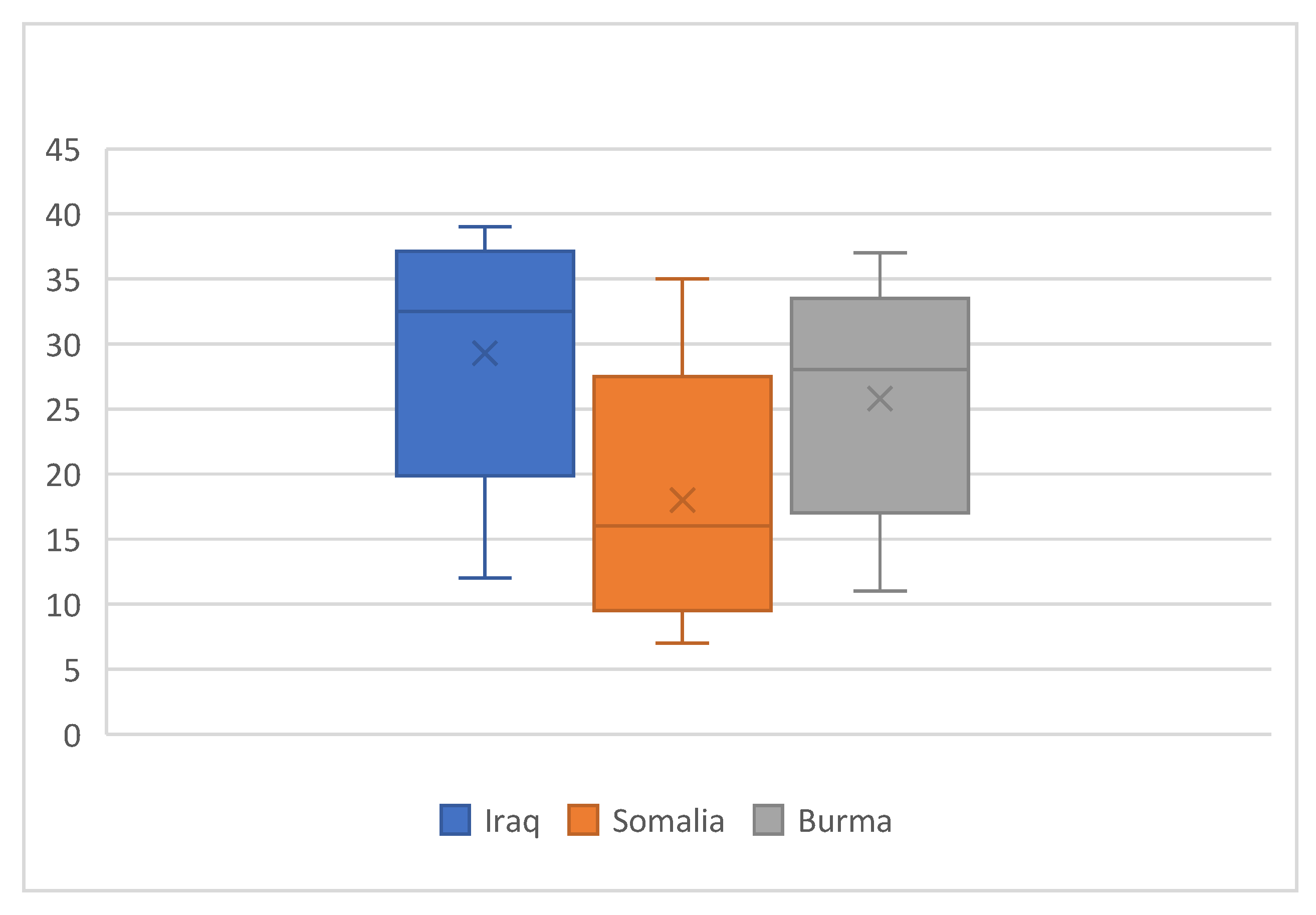

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Findings

“For me… you have to [be] healthy both spiritual and physical. Sometimes I experience, I have physically, we healthy, we strong enough, but inside, sometimes, we’re not strong…physically we strong, but we are weak in spiritual.”—Respondent from Burma

“…health is people who comes together and greet each other and hug each other, and talk to each other.”—Respondent from Somalia

“Anytime I don’t feel sick, I feel happy. If I feel worried about people in Africa, that we left them behind. When you feel something is wrong with your family who is with you right now, that’s when you feel sick”—Respondent from Somalia

“There’s a lot of people who don’t like to see the doctor unless they are very sick, like an emergency. They just wanna go around and socialize with the community…Just asking questions each other and saying, “How do you stay healthy?”—Respondent from Somalia

“In Iraq, it was everyday story with all the politics and the news and the bombs and the challenges that I had in my life and the threats. It [physical condition] was severe. Now, I think it’s more controllable. My mental health affected my physical health”—Respondent from Iraq

“When we feel healthy…we are happy.”—Respondent from Burma

“I was calm this morning. I didn’t have anything to worry. Yeah, I was just happy this morning. Nothing that I feel like—there’s nothing I’m thinking about.”—Respondent from Somalia

They’re happy. The group is happy. You go to the bus and you see someone, and say, “Hi.” They say, “Hi.”—Respondent from Somalia

Sometimes, when she hear[s] good news, that time she feels happy, when she sleeps good, and she’s not stressed out. There’s nothing that she can think of, and she feels good. That’s when she feels healthy.—Respondent from Iraq

3.3. Qualitative and Quantitative Data Convergence

3.3.1. Burma

“it’s not just physical health, it will be both physical and mental… I always share my recent trip, that’s why I feel like I wasn’t tired physically or emotionally, and that’s when I feel like that’s what health mean to me, just quiet and enjoy the moment.”—Respondent from Burma

3.3.2. Somalia

“If people don’t have a relationship, that would be unhealthy. Like if the community don’t have a relationship, they don’t talk to each other. No matter who they are, or where they’re from. The community who lives each other should be talking to each other. They should be knowing each other”—Respondent from Somalia

3.3.3. Iraq

“when [I] hear health, it’s somebody stays in a safe place with good condition, and that’s the important thing.”—Respondent from Iraq

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Quantitative Results

4.2. Interpretation of Qualitative Findings and Emergent Constructs of Health

4.3. Integration of Mixed-Methods Findings

4.3.1. Burma

4.3.2. Somalia

4.3.3. Iraq

4.4. Implications of Integrated Findings

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDOH | Social Determinants of Health |

References

- Vidal, E.M.; Wickramage, K.P. Tracking migration and health inequities. Bull. World Health Organ. 2024, 102, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations High Comissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2023; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Edberg, M.; Cleary, S.; Vyas, A. A Trajectory Model for Understanding and Assessing Health Disparities in Immigrant/Refugee Communities. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elwell, D.; Junker, S.; Sillau, S.; Aagaard, E. Refugees in Denver and Their Perceptions of Their Health and Health Care. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2014, 25, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, M.S.; Wee, C.C.; McCarthy, E.P.; Davis, R.B.; Ngo-Metzger, Q.; Phillips, R.S. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, G.; Puma, J.; Engelman, A.; Miller, M. The Refugee Integration Survey and Evaluation (RISE): Year Five Final Report—A Study of Refugee Integration in Colorado; Colorado Department of Human Services, Office of Economic Security, Colorado Refugee Services Program: Denver, CO, USA, 2016; Available online: https://brycs.org/clearinghouse/6155/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bollini, P.; Siem, H. No real progress towards equity: Health of migrants and ethnic minorities on the eve of the year 2000. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rfat, M.; Cureton, A.; Mirza, M.; Trani, J.-F. The devastating effect of abrupt US refugee policy shifts. Lancet 2025, 405, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziersch, A.; Miller, E.; Baak, M.; Mwanri, L. Integration and social determinants of health and wellbeing for people from refugee backgrounds resettled in a rural town in South Australia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, F.R.; Lo, E.; Maxwell, A.; Reynolds, P.P. Factors Influencing the Acculturation of Burmese, Bhutanese, and Iraqi Refugees Into American Society: Cross-Cultural Comparisons. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2014, 12, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.; Enticott, J.; Russell, G. Measuring self-rated health status among resettled adult refugee populations to inform practice and policy—A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of State; Bureau of Population; Refugees; Migration (PRM). Refugee Arrivals by State and Nationality. 2021. Available online: https://www.rpc.state.gov/documents/Refugee%20Arrivals%20by%20State%20and%20Nationality%20as%20of%2031%20Jul%202021.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Organization (WHO): Constitution of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.L. The Sociology of Health and Illness. In The SAGE Handbook of Sociology; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2011; pp. 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.; Klassen, A.C.; Plano, V.; Smith, K.C. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Available online: https://obssr.od.nih.gov/sites/obssr/files/Best_Practices_for_Mixed_Methods_Research.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Cresswell, J.W.; Plano-Clark, V.L.; Gutmann, M.L.; Hanson, W.E. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, M.M. The Century of Migration and the Contribution of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2018, 12, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Mixed Methods Research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, M. Linking Science and Policy Through Community-Based Participatory Research to Study and Address Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100 (Suppl. 1), S81–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.B.; Duran, B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promot. Pract. 2006, 7, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N. What Is the Evidence on Effectiveness of Empowerment to Improve Health? Health Evidence Network Report; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copehagen, Denmark, 2006; pp. 1–40. Available online: https://www.equinetafrica.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/WHOequity0301022007.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory. Res. Pract. 2015, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D. Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Rasco, L.M. An ecological framework for addressing the mental health needs of refugee communities. In The Mental Health of Refugees: Ecological Approaches to Healing and Adaptation; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS). Refugees, Asylees, and Secondary Migrants in Colorado, Fiscal Years 1980–2017; CDHS: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. Available online: https://cdhs.colorado.gov (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- ReliefWeb. The World’s Five Biggest Refugee Crises: Afghanistan; ReliefWeb: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/worlds-5-biggest-refugee-crises (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Salganik, M.J.; Heckathorn, D.D. Sampling and Estimation in Hidden Populations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2004, 34, 193–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Soc. Probl. 1997, 44, 174–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics XM//The Leading Experience Management Software; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.B. How Many Subjects Does It Take To Do A Regression Analysis? Multivar. Behav. Res. 1991, 26, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Revicki, D.A.; Spritzer, K.L.; Cella, D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miilunpalo, S.; Vuori, I.; Oja, P.; Pasanen, M.; Urponen, H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: The predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Yan, X.; He, J. The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, C. 2016 Refugees Study; Infakto Research Workshop: Istanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire (English Version). Brfss Published Online First: 2009. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2009brfss.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 26.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.R.; Creech, J.C. Ordinal Measures in Multiple Indicator Models: A Simulation Study of Categorization Error. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, N.J.; Lipsitz, S.R. Multiple Imputation in Practice: Comparison of software packages for regression models with missing variables. Am. Stat. 2001, 55, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, S. Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2014, 5, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.; Warr, D.; Gibbs, L.; Riggs, E. Addressing Ethical and Methodological Challenges in Research with Refugee-background Young People: Reflections from the Field. J. Refug. Stud. 2013, 26, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, H.; Trinidad, S.B. Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, J.P.; LeCompte, M.D. Ethnographic Research and the Problem of Data Reduction. Anthr. Educ. Q. 1981, 12, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.; Ziebland, S.; Mays, N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000, 320, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS. ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. In ATLAS.ti 8 for Windows; ATLAS.ti: Berlin, Germany; Available online: https://atlasti.com/product/v8-windows/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purgato, M.; Tol, W.A.; Bass, J.K. An ecological model for refugee mental health: Implications for research. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2017, 26, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization [WHO]: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852 (accessed on 20 October 2025)ISBN 978 92 4 150085 2.

- Pollenne, D. The Place of Safety in Refugees’ Subjective Well-Being; Refugee Survey Quarterly; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025; Advance online publicatoin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.E.; McMahon, T.; Grech, K.; Samsa, P. Resettlement Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being among Refugees in Australia: Findings from a Service Evaluation. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2021, 22, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Y. Social Media, Digital Resilience, and Knowledge Sustainability: Syrian Refugees’ Perspectives. J. Intercult. Commun. 2025, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. Am. Anthr. 1936, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Dworkin, S.L.; Tong, S.; Banks, I.; Shand, T.; Yamey, G. The men’s health gap: Men must be included in the global health equity agenda. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014, 92, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peersman, W.; Cambier, D.; De Maeseneer, J.; Willems, S. Gender, educational and age differences in meanings that underlie global self-rated health. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A.; Huzurbazar, S.; Todd, M. Gender and the structure of self-rated health across the adult life span. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; A Stone, A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.A.; Acciai, F.; Reyes, A.M. How Health Conditions Translate into Self-Ratings: A comparative study of older adults across Europe. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2014, 55, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwin, C.M.; Yancura, L.A. Effects of stress on health and aging: Two paradoxes. Calif. Agric. 2010, 64, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F. The relationship between happiness and health: Evidence from Italy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 114, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dfarhud, D.; Malmir, M.; Khanahmadi, M. Happiness & Health: The Biological Factors- Systematic Review Article. Iran. J. Public Health 2014, 43, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lindencrona, F.; Ekblad, S.; Hauff, E. Mental health of recently resettled refugees from the Middle East in Sweden: The impact of pre-resettlement trauma, resettlement stress and capacity to handle stress. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008, 43, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Somali Refugee Health Profile; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Tones, K.; Green, J. Health Promotion: Planning and Strategies; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- USA for UNHCR. Protracted Refugee Situations Explained. New York, NY, USA 2020. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/protracted-refugee-situations-explained/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- USA for UNHCR. Somalia Refugee Crisis Explained. 2020. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/somalia-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- USA for UNHCR. Iraq Refugee Crisis Explained. UNHCR. 2019. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/iraq-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Davenport, L.A. Living with the Choice: A Grounded Theory of Iraqi Refugee Resettlement to the U.S. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 38, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, P.; Lockwood-Kenny, K. A Mixed Blessing: Karen Resettlement to the United States. J. Refug. Stud. 2011, 24, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Denver-Metro Area Refugee Survey Population (N= 149) | |||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | |

| Self-Reported Health Status Sum Score | 24.43 | 8.33 | 7 | 39 |

| Country of Origin (n = 149) | Denver-Metro Area Refugee Survey Population (n = 149) Frequency (%) | |||

| Burma | 51 (34.2) | |||

| Iraq | 46 (30.9) | |||

| Somalia | 52 (34.9) | |||

| Years in Refugee Camp (n = 129) | ||||

| 0 | 32 (24.8) | |||

| 1 to 5 | 32 (24.8) | |||

| 6 to 10 | 29 (22.5) | |||

| 11 to 15 | 19 (14.7) | |||

| 16+ | 17 (13.2) | |||

| Time in the United States (n = 146) | ||||

| <1–3 years | 33 (22.6) | |||

| 4–5 years | 37 (25.3) | |||

| 6–10 years | 51 (34.9) | |||

| 11+ years | 25 (17.1) | |||

| Social Adjustment (n = 129) | ||||

| No change | 88 (68.2) | |||

| Positive change | 22 (17.1) | |||

| Negative change | 19 (14.7) | |||

| Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Denver-Metro Area Refugee Survey Population (N = 149) |

| Sex (n = 135) | |

| Male | 44 (32.6) |

| Female | 91 (67.4) |

| Age (n = 145) | |

| 18–25 | 29 (20.0) |

| 26–39 | 51 (35.2) |

| 40–54 | 26 (17.9) |

| 55–64 | 19 (13.1) |

| 65+ | 20 (13.8) |

| Employment Status (n = 141) | |

| Employed for wages or self-employed | 63 (44.7) |

| Not Employed | 78 (55.3) |

| Marital Status (n = 134) | |

| Married/Cohabiting | 81 (60.4) |

| Single/Divorced/Widowed | 53 (39.6) |

| Education (n = 130) | |

| None | 21 (16.2) |

| Elementary School | 16 (12.3) |

| Middle School | 13 (10.0) |

| High School | 44 (33.8) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 30 (23.1) |

| Advanced Degree | 6 (4.6) |

| Household Income (n = 141) | |

| <$20,000 | 85 (60.3) |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 35 (24.8) |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 7 (5.0) |

| $40,000–$49,000 | 6 (4.3) |

| >$50,000 | 8 (5.7) |

| Demographic Characteristics of Survey Participants | |

|---|---|

| Variable | Denver-Metro Area Refugee Survey Population (N = 149) |

| Access to a Healthcare Provider (n = 144) | |

| No | 29 (20.1) |

| Yes, one healthcare provider | 69 (47.9) |

| Yes, more than one | 24 (16.7) |

| Don’t know/not sure | 22 (15.3) |

| Access to Parks and Trails (n = 145) | |

| Yes | 114 (78.6) |

| No | 31 (21.4) |

| Religion (n = 149) | |

| Muslim | 104 (69.8) |

| Other religions (e.g., Christian) | 45 (30.2) |

| Access to Healthy Food (n = 147) | |

| Yes | 136 (92.5) |

| No | 11 (7.5) |

| Safe Public Spaces (Safety) (n = 129) | |

| Yes | 94 (72.8) |

| No | 35 (27.1) |

| N = 135 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model Fit | R2 = 0.758 | F = 18.950 (p < 0.001) |

| Independent Variables | B (p-Value) | CI |

| Years spent in a refugee camp | 0.485 (0.269) | (−0.380, 1.350) |

| Length of time in US | −0.604 (0.114) | (−1.354, 0.147) |

| Social Adjustment (Positive Change) | −0.632 (0.671) | (−3.575, 2.311) |

| Country of Origin: Burma | −3.419 (0.030) * | (−6.493, −0.345) |

| Country of Origin: Somalia | −9.155 (<0.001) *** | (−12.258, −6.052) |

| Religion: Muslim | 0.255 (0.813) | (−1.880, 2.390) |

| Age | 1.901 (<0.001) *** | (1.105, 2.698) |

| Sex: Male | −3.252 (<0.001) *** | (−5.158, −1.345) |

| Marital Status: Coupled | 0.348 (0.692) | (−1.383, 2.079) |

| Education Level | −0.999 (<0.001) *** | (−1.584, −0.414) |

| Income | −0.189 (0.630) | (−0.966, 0.587) |

| Employment | −1.757 (0.075) | (−3.692, 0.178) |

| Access to Healthcare | 0.917 (0.511) | (−1.836, 3.670) |

| Access to Healthy Food | 2.606 (0.106) | (−0.566, 5.778) |

| Access to Parks & Trails | −0.208 (0.855) | (−2.455, 2.038) |

| Safe Recreation | −1.915 (0.080) | (−4.067, 0.236) |

| Variable | Interview Participants (n = 27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | |

| Age | 39.3 | 14.7 |

| Years in US | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Sex | Frequency (%) | |

| Male | 7 (25.9) | |

| Female | 20 (74.1) | |

| Country of Origin | Frequency (%) | |

| Iraq | 11 (42) | |

| Burma | 8 (29) | |

| Somalia | 8 (29) | |

| Quantitative Finding | Related Qualitative Theme(s) | Convergence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Older age associated with higher self-rated health | Older adults describe stability, acceptance, and a strong sense of resilience; value routines that support well-being | ✔ | Qualitative accounts of resilience and reframing of adversity align with higher self-reported health among older participants |

| Men report lower health than women | Men emphasize stress related to employment, financial responsibility, and role expectations | ✔ | Men’s narratives of stress and pressure mirror lower self-rated health scores in quantitative data |

| Higher education associated with lower self-rated health | Educated refugees describe downward occupational mobility, unmet expectations, and stress navigating new systems | ✔ | Qualitative themes illuminate why education is associated with perceived health, despite typically protective effects |

| Somali and Burmese origin predict lower health (compared to Iraq) | All interviewees describe trauma, resettlement hardship, and barriers related to environment and the health system | ✔ | Quantitative differences between groups reflect lived experiences described in interviews |

| No significant quantitative associations with SDoH indicators (e.g., access to parks, food, healthcare) | Participants emphasize happiness, daily routines, safety, community belonging, and emotional well-being as core components of health | — | Qualitative data expand beyond measured SDoH variables, highlighting culturally grounded definitions of health not captured in the quantitative model |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boyd, K.; Puma, J.; Lambert-Kerzner, A.; Ingman, B.C.; Alshadood, M.; Kaufman, C.E. Perceptions of Health in the Denver Refugee Community: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121876

Boyd K, Puma J, Lambert-Kerzner A, Ingman BC, Alshadood M, Kaufman CE. Perceptions of Health in the Denver Refugee Community: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121876

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoyd, Katherine, Jini Puma, Anne Lambert-Kerzner, Benjamin C. Ingman, Maytham Alshadood, and Carol E. Kaufman. 2025. "Perceptions of Health in the Denver Refugee Community: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121876

APA StyleBoyd, K., Puma, J., Lambert-Kerzner, A., Ingman, B. C., Alshadood, M., & Kaufman, C. E. (2025). Perceptions of Health in the Denver Refugee Community: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121876