“I’m Not Right to Drive, but I Drove out the Gate”: Personal and Contextual Factors Affecting Truck Driver Fatigue Compliance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Site Selection

2.2. Recruitment Process

2.3. Participants

2.4. Semi-Structured Interview Measures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

- (1)

- Personal factors influence TDF risk and compliance behaviour.

- (a)

- Personal financial viability and payment methods influence TDF risk behaviour.

- (b)

- Fatigue risks for owner-operators and small companies.

- (2)

- Inflexible enforcement and financial impacts affect fatigue.

- (3)

- Organisational practices affect TDF risks.

- (a)

- Electronic monitoring may reduce TDF risks.

- (b)

- Fixed roadside monitoring cameras can increase TDF risk.

3.1. Personal Factors Influence TDF Risk and Compliance Behaviour

“I’m fatigued, I’m not right to drive, but I still showed up for work, I still started the truck and still drove out the gate”(Rowan, truck driver, 49),

“So long as they make that phone call [to discuss personal issues affecting fatigue], you can manage it. But if they fear for their job, they’re going to come to work and put everyone at risk, including themselves”(Harry, transport manager, 55 years old).

3.1.1. Personal Financial Viability and Payment Methods Influence TDF Risk Behaviour

“Drivers who are on hourly rates take it all in their stride because they’re still getting paid. Guys who are on trip money, who have to wait for two hours while everybody dicks you around, is technically not getting paid”(Warren, driver, 65).

3.1.2. Fatigue Risks for Owner-Drivers and Small Companies

“They can’t just do Sydney [to] Melbourne [900 km] twice a week, they’ve actually got to do it five or six times to be able to pay themselves a reasonable wage because the rate of the freight has been screwed down that much”(Lachie, driver, 56).

3.2. Inflexible Enforcement and Financial Impacts Affect Fatigue

“The rules don’t coincide with the human experience, which is individual to every person”(Vicki, driver, 49).

“You send 10 trucks down the road overloaded and with tired drivers in them. How many are gonna get caught? Probably only if something goes wrong”(Aaron, manager, 62).

3.3. Organisational Practices Affect TDF Risk

“You felt brave enough to say to your boss, I can’t do that cause I got to have a 7 h break. And thought OK, well maybe these fatigue laws work.”(David, driver, 58)

3.3.1. Electronic Monitoring May Reduce TDF Risks

“I love it. It’s so easy, so simple, it tells you what you can and can’t do. The only trouble is you can’t cheat it. With an electronic logbook, you’re out of hours, you stop. With a paper book, I’ll just drive to my destination then just manipulate the driving time.”(Oscar, driver, 59).

3.3.2. Fixed Roadside Monitoring Cameras Can Increase TDF Risk

“push themselves to get past these cameras to have a [mandatory 7 h continuous stationary] rest on the other side, [which] is a dangerous thing”(Oscar, driver, 59).

4. Discussion

4.1. Family-Friendly Work Practices and Safety Culture

4.2. Technology Promising Better Fatigue Management

4.3. Recommendations

- (1)

- Co-develop strategies within fatigue management systems to account for personal factors likely to influence drivers’ intentions regarding TDF and support them to engage in safer and healthier TDF practices.

- (2)

- Facilitate the development, provision and promotion of standardized education resources and programs for truck drivers’ families so they can better support drivers to maintain restorative rest practices and healthy lifestyles.

- (3)

- Implement flexible scheduling to better enable truck drivers to rest as required.

- (4)

- Furthermore, it is recommended that industry peak bodies and the government perform the following: Reduce or prohibit the use of incentive payments in favour of hourly payments that include remuneration for delays and waiting times when loading or unloading.

- (5)

- Redefine the regulatory definition of ”rest” to ensure it directs restorative rest during both pre-shift and in-shift rest periods. This could include allowing rest periods at any time after 2 h of driving, and 20 min rest periods to enable a 15 min ”power nap”. For such provisions to be workable, they may need to occur in concert with the infrastructure improvements (e.g., dedicated truck driver rest areas) identified in recent research [6].

- (6)

- Encourage compliance organisations to refocus activities towards others in the chain of responsibility. This can incentivise companies to engage in safer TDF practices that support drivers and reduce the inequity of driver-focused enforcement.

- (7)

- Play a leading role in financing, developing and promoting industry-standardised training and technologies such as e-diaries and e-monitors for all drivers and companies, with a particular focus on enabling small companies to access these resources.

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Practical and Theoretical Contributions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GVM | Gross Vehicle Mass |

| TDF | Truck Driver Fatigue |

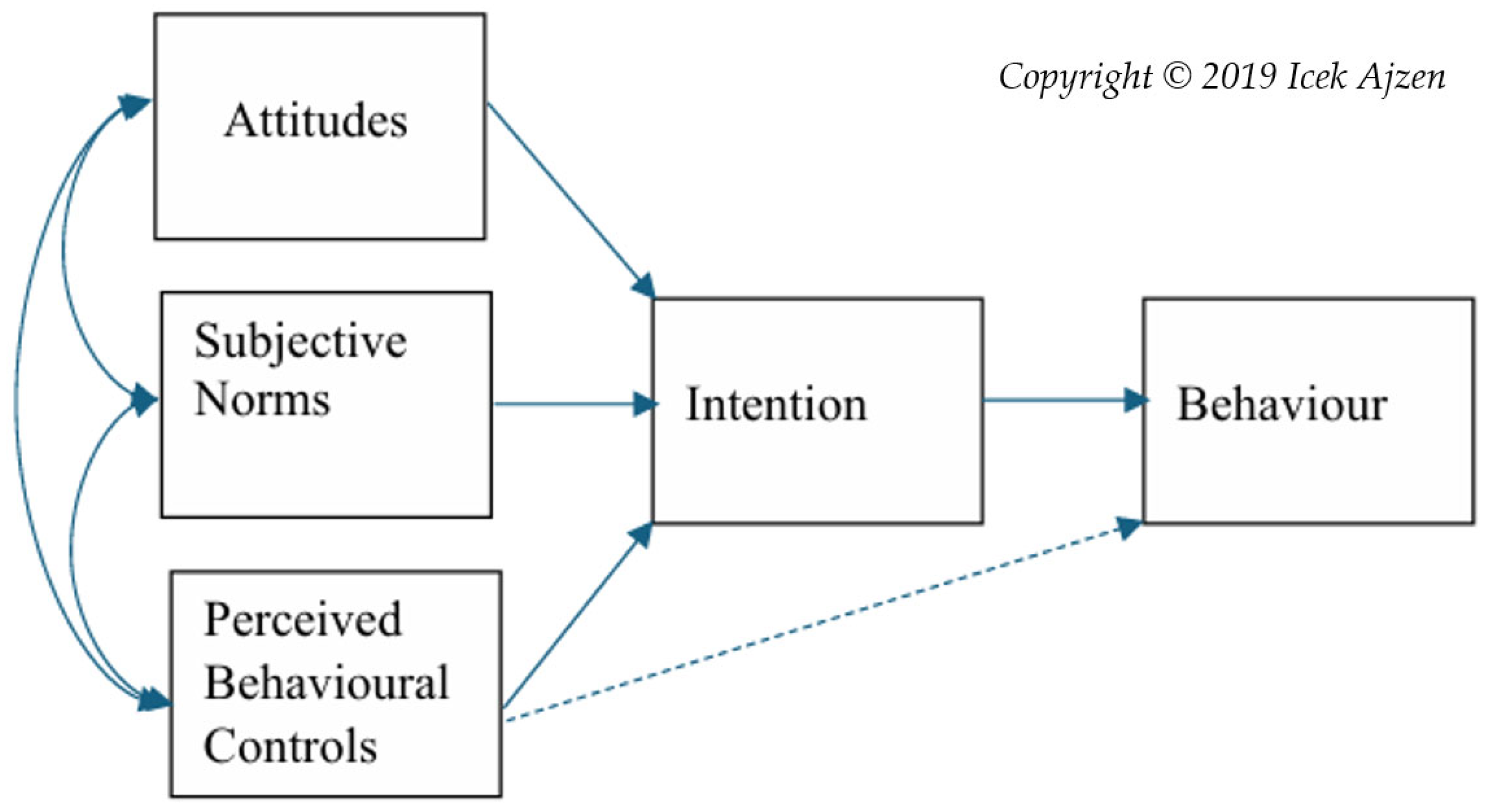

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| HVNL | Heavy Vehicle National Law |

| WHS | Workplace Health and Safety |

Appendix A. Participation Texts—Truck Drivers and Transport Managers

Appendix B. Interview Schedule—Truck Drivers

- 1.

- Demographics and Experience

- 2.

- Learning about truck driver fatigue and fatigue management

- 3.

- Beliefs, attitude—RQ 2—How these shape compliance/non-compliance

- 4.

- Subjective norms—RQ 3—Key Influences on compliance/non-compliance

- 5.

- Perceptions of behavioural control—RQ 4—How easy/difficult it is to comply/not comply with the behaviour (compliance/non-compliance with driver fatigue guidelines/laws/company rules)

Appendix C. Interview Schedule—Transport Managers

- 1.

- Demographics and Experience

- 2.

- Learning about truck driver fatigue and fatigue management

- 3.

- Beliefs, attitude—RQ 2—How these shape compliance/non-compliance

- 4.

- Subjective norms—RQ 3—Key Influences on compliance/non-compliance

- 5.

- Perceptions of behavioural control—RQ 4—How easy/difficult it is to comply/not comply with the behaviour (compliance/non-compliance with driver fatigue rules/regulations/laws/guidelines)

References

- Friswell, R.; Williamson, A. Comparison of the fatigue experiences of short haul light and long distance heavy vehicle drivers. Saf. Sci. 2013, 57, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.E.; Desai, A.V.; Grunstein, R.R.; Hukins, C.; Armstrong, J.G.; Joffe, D.; Swann, P.; Campbell, D.A.; Pierce, R.J. Sleepiness, Sleep-disordered Breathing, and Accident Risk Factors in Commercial Vehicle Drivers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin-Brown, C.M.; Filtness, A.J. Introduction. In The Handbook of Fatigue Management in Transportation: Waking up to the Challenge, 1st ed.; Rudin-Brown, C.M., Filtness, A.J., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Accident Research and Road Safety-Queensland (CARRS-Q). Sleepiness and Fatigue; Queensland University of Technology: Brisbane City, QLD, Australia, 2015; Available online: https://research.qut.edu.au/carrs-q/wp-content/uploads/sites/296/2020/06/Sleepiness-and-fatigue-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2019).

- Williamson, A.; Lombardi, D.A.; Folkard, S.; Stutts, J.; Courtney, T.K.; Connor, J.L. The link between fatigue and safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, G.J.; Miles-Johnson, T.; Stevens, G.J. Breaching rest requirements: Perceptions of fatigue management by truck drivers and transport managers. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 114, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transport Commission. Effective Fatigue Management, Issues Paper; NTC: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/fatigue_issues_paper__17_May_2019.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Williamson, A.; Friswell, R. Submission to the National Transport Commission Review of the National Heavy Vehicle Law, Issues Paper: Effective Fatigue Management. 2019. Available online: https://www.nhvr.gov.au/files/201908-1092-nhvr-submission-effective-fatigue-management-hvnl-review-16082019.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Ren, X.; Pritchard, E.; van Vreden, C.; Newnam, S.; Iles, R.; Xia, T. Factors Associated with Fatigued Driving among Australian Truck Drivers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian National University. Social Cost of Road Crashes; Report for the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics; The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. Quarterly Heavy Vehicle Road Deaths. Available online: https://datahub.roadsafety.gov.au/safe-systems/safe-vehicles/quarterly-heavy-vehicle-road-deaths (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Casey, G.J.; Miles-Johnson, T.; Stevens, G.J. Heavy vehicle driver fatigue: Observing work and rest behaviours of truck drivers in Australia. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 104, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Archetti, C.; Savelsbergh, M. Truck driver scheduling in Australia. Comput. Oper. Res. 2012, 39, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavy Vehicle National Law (NSW) No 42 of 2013. Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-2013-42a (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Walter, L.; Broughton, J.; Knowles, J. The effects of increased police enforcement along a route in London. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, C.; Quinlan, M. Economic pressure, multi-tiered subcontracting and occupational health and safety in Australian long-haul trucking. Empl. Relat. 2006, 28, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, L.; O’Neill, S. Evaluating Approaches to Regulating WHS in the Australian Road Freight Transport Industry: Final Report to the Transport Education, Audit and Compliance Health Organisation Ltd. (TEACHO); Macquarie University, Centre for Workforce Futures: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, A.; Friswell, R. The effect of non-driving factors, payment type and waiting and queuing on fatigue in long distance trucking. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 58, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lise, F.; Shattell, M.; Garcia, R.P.; Rodrigues, K.C.; de Ávila, W.T.; Garcia, F.L.; Schwartz, E. Long-Haul Truck Drivers’ Perceptions of Truck Stops and Rest Areas: Focusing on Health and Wellness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, E.; van Vreden, C.; Xia, T.; Newnam, S.; Collie, A.; Lubman, D.; de Almeida Neto, A.; Iles, R. Impact of work and coping factors on mental Health: Australian truck drivers’ perspective. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Pritchard, E.; van Vreden, C.; Collie, A.; Newnam, S.; Lubman, D.I.; Iles, R. Factors associated with psychological distress among Australian truck drivers: The role of personal, occupation, work, lifestyle, and health risk factors. J. Transp. Health 2025, 41, 101973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C. Neoliberalism and the reform of regulation policy in the Australian trucking sector: Policy innovation or a repeat of known pitfalls? Policy Stud. 2015, 37, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, E.; Van Vreden, C.; Iles, R. Driving Health Study Report No 7: Uneven Wear: Health and Wellbeing of Truck Drivers; Insurance Work and Health Group, Faculty of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frontier Economics. HVNL Review Consultation Regulation Impact Statement. 2020. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/HVNLR-consultation-RIS.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- National Transport Commission. Effective Enforcement, Issues Paper; NTC: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/hdp.au.prod.app.ntc-hvlawreview.files/3415/6765/1879/Effective_enforcement_issues_paper.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Adams-Guppy, J.; Guppy, A. Truck driver fatigue risk assessment and management: A multinational survey. Ergonomics 2003, 46, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, M.R.; Morrow, P.C. The Influence of Carrier Scheduling Practices on Truck Driver Fatigue. Transp. J. 2002, 42, 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, P.H.; Marshall, N.S.; James, I.; Quesne, L.L. Investigating driver fatigue in truck crashes: Trial of a systematic methodology. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horberry, T.; Mulvihill, C.; Fitzharris, M.; Lawrence, B.; Lenne, M.; Kuo, J.; Wood, D. Human-Centered Design for an In-Vehicle Truck Driver Fatigue and Distraction Warning System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 5350–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Li, S.; Cao, L.; Li, M.; Peng, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. Driving Fatigue in Professional Drivers: A Survey of Truck and Taxi Drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2015, 16, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, S. Drivers’ fatigue studies. Ergonomics 1997, 40, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Ojiro, D.; Tanaka, T.; Minusa, S.; Kuriyama, H.; Yamano, E.; Watanabe, Y. Relationship between truck driver fatigue and rear-end collision risk. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.O.; Kecklund, G.; Anund, A.; Sallinen, M. Fatigue in transport: A review of exposure, risks, checks and controls. Transp. Rev. 2017, 37, 742–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J. Invisible Influence: The Hidden Forces That Shape Behavior; Simon & Schuster: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, B.; Conner, M. Applying an Extended Version of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Illicit Drug Use Among Students. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1662–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.; Hagger, M. Effects of a brief intervention based on the theory of planned behavior on leisure-time physical activity participation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 470–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles-Johnson, T. LGBTI Variations in Crime Reporting: How Sexual Identity Influences Decisions to Call the Cops. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 215824401349070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Swartz, S. Truck Driver Safety: An Evolutionary Research Approach. Transp. J. 2016, 55, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, P. Addressing Human Factors in the Motor Carrier Industry in Canada; Human Factors and Motor Carrier Safety Taskforce, Canadian Council of Motor Transport Administrators: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.B.A. Crafting Qualitative Research Questions: A Prequel to Design; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Table 06. Employed Persons by Industry Sub-Division of Main Job (ANZSIC) and Sex. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed/latest-release#industry-occupation-and-sector (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Robson, C.; McCartan, K. Real World Research, A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings, 4th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E.; Reck, J.; Fields, J. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, K.R.; Gaulee, U. Interviewing Female Teachers as a Male Researcher: A Field Reflection from a Patriarchal Society Perspective. Qual. Rep. 2023, 28, 2589–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/13620-000 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friswell, R.; Williamson, A. Management of heavy truck driver queuing and waiting for loading and unloading at road transport customers’ depots. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soames Job, R.F.; Graham, A.; Sakashita, C.; Hatfield, J. Fatigue and Road Safety: Identifying Crash Involvement and Addressing the Problem within a Safe Systems Approach. In The Handbook of Operator Fatigue; Matthews, G., Desmond, P.A., Neubauer, C., Hancock, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G.; Desmond, P.A. Stress and Driving Performance: Implications for Design and Training. In Stress, Workload, and Fatigue; Hancock, P.A., Desmond, P.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rowden, P.; Matthews, G.; Watson, B.; Biggs, H. The relative impact of work-related stress, life stress and driving environment stress on driving outcomes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavy Vehicle (Fatigue Management) National Regulation (NSW) (2013 SI 245a). Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/sl-2013-245a (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Honn, K.A.; Dongen, H.P.A.V.; Dawson, D. Working Time Society consensus statements: Prescriptive rule sets and risk management-based approaches for the management of fatigue-related risk in working time arrangements. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.A.; Filtness, A.J.; Anund, A.; Pilkington-Cheney, F.; Maynard, S.; Sjörs Dahlman, A. Exploring sleepiness and stress among London bus drivers: An on-road observational study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 207, 107744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transport Commission. HVNL Review: 2019 Consultation Outcomes, Consultation Report; NTC: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/Summary_of_consultation_outcomes_-_HVNL_Review.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Castanelli, G. Chain of Responsibility, Have we got it upside down. In Truckin’ Life; Kendall, G., Ed.; Truckin’ Life Pty Ltd.: Evans Head, NSW, Australia, 2025; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Delahunty, J. Four Ingredients: New Recipes for Procedural Justice in Australian Policing. Policing 2010, 4, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varet, F.; Granié, M.A.; Carnis, L.; Martinez, F.; Pelé, M.; Piermattéo, A. The role of perceived legitimacy in understanding traffic rule compliance: A scoping review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, P.; Folkard, S. Work Scheduling. In The Handbook of Operator Fatigue; Matthews, G., Desmond, P.A., Neubauer, C., Hancock, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gruchmann, T.; Jazairy, A. Big brother is watching you: Examining truck drivers’ acceptance of road-facing dashcams. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 111, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heavy Vehicle Regulator. Camera Enforcement. Available online: https://www.nhvr.gov.au/safety-accreditation-compliance/on-road-compliance-and-enforcement/camera-enforcement (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Feyer, A.-M.; Williamson, A. Broadening our view of effective solutions to commercial driver fatigue. In Stress, Workload, and Fatigue; Hancock, P.A., Desmond, P.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, D.; Thomas, M.J.W. Fatigue management in healthcare: It is a risky business. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 1493–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, M. Shift work and health. Health Rep. 2002, 13, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Van Vreden, C.; Pritchard, E.; Newnam, S.; Rajaratnam, S.; Lubman, D.; Collie, A.; de Almeida Neto, A.; Iles, R. Driving Health, Report No 8, Determinants of Australian Truck Driver Physical and Mental Health and Driving Performance: Findings from the Telephone Survey; Insurance Work and Health Group, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I.S.; Popkin, S.; Folkard, S. Working Time Society consensus statements: A multi-level approach to managing occupational sleep-related fatigue. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C.O. (Evans Head, NSW, Australia); Forsyth, C.R. (Evans Head, NSW, Australia); Hannifey, R. (Dubbo, NSW, Australia); O’Leary, L. (Canberra, ACT, Australia); Welsh, B. (Tamworth, NSW, Australia). Personal communication, 2025.

- Rogers, M.; Johnson, A.; Coffey, Y. Gathering voices and experiences of Australian military families: Developing family support resources. J. Mil. Veteran Fam. Health 2024, 10, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P.K.; Hartley, L.R. Policies and practices of transport companies that promote or hinder the management of driver fatigue. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2001, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartt, A.T.; Hellinga, L.A.; Solomon, M.G. Work Schedules of Long-Distance Truck Drivers Before and After 2004 Hours-of-Service Rule Change. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2008, 9, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Sieber, W.; Collins, J.; Hitchcock, E.; Lincoln, J.; Pratt, S.; Sweeney, M. Truck driver reported unrealistically tight delivery schedules linked to their opinions of maximum speed limits and hours-of-service rules and their compliance with these safety laws and regulations. Saf. Sci. 2021, 133, 105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, P.K.; Hartley, L.R.; Corry, A.; Hochstadt, D.; Penna, F.; Feyer, A.M. Hours of work, and perceptions of fatigue among truck drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 1997, 29, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, S. Just Culture: Balancing Safety and Accountability, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arboleda, A.; Morrow, P.C.; Crum, M.R.; Shelley, M.C. Management practices as antecedents of safety culture within the trucking industry: Similarities and differences by hierarchical level. J. Safety Res. 2003, 34, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nævestad, T.-O.; Blom, J.; Phillips, R.O. Safety culture, safety management and accident risk in trucking companies. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 73, 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, A.; Goedhals-Gerber, L.L.; Bod, A.D. Assessing truck driver fatigue perceptions: Insights from a South African road freight context. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2025, 21, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, C.; Kueny, C.; Murray, S. Establishing links between safety culture, climate, behaviors, and outcomes of long-haul truck drivers. J. Safety Res. 2023, 85, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transport Insurance. NTI’s Guide to the Trucking Industry; National Transport Insurance: Brisbane, Australia, 2016; Available online: http://www.thewordshop.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/NTI-eBook-Editing.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- National Transport Commission. Safe People and Practices, Issues Paper; NTC: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/NTC_Issues_Paper_-_Safe_people_and_practices.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Arlinghaus, A.; Bohle, P.; Iskra-Golec, I.; Jansen, N.; Jay, S.; Rotenberg, L. Working Time Society consensus statements: Evidence-based effects of shift work and non-standard working hours on workers, family and community. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frade, C.; Darmon, I. New modes of business organization and precarious employment: Towards the recommodification of labour? J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2005, 15, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfson, C. The continuing price of Britain’s oil: Business organisation, precarious employment and risk transfer mechanisms in the North Sea petroleum industry. In Governance and Regulation in Social Life: Essays in Honour of W. G. Carson; Brannigan, A., Pavlich, G., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2007; pp. 65–84. Available online: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uwsau/detail.action?docID=293085 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Lovato, N.; Lack, L. The effects of napping on cognitive functioning. Prog. Brain Res. 2010, 185, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A. Countermeasures for Driver Fatigue. In The Handbook of Operator Fatigue; Matthews, G., Desmond, P.A., Neubauer, C., Hancock, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crum, M.R.; Morrow, P.C.; Olsgard, P.; Roke, P.J. Truck Driving Environments and Their Influence on Driver Fatigue and Crash Rates. Transp. Res. Rec. 2001, 1779, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, E.; Bortoletto, M.S.S.; González, A.D.; Mesas, A.E.; Peixe, T.S.; Guidoni, C.M.; de Andrade, S.M. Working conditions and sleepiness while driving among truck drivers. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2019, 20, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, C.; Itaya, A.; Inomata, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yoshida, C.; Nakazawa, M. Working conditions and fatigue in log truck drivers within the Japanese forest industry. Int. J. For. Eng. 2023, 34, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh-Ehrlich, S.; Friedman, L.; Richter, E.D. Working conditions and fatigue in professional truck drivers at Israeli ports. Inj. Prev. 2005, 11, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, H. The Techno-Fix Versus the Fair Cop: Procedural (In)Justice and Automated Speed Limit Enforcement. Br. J. Criminol. 2008, 48, 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster.com. Belief Meaning. 2022. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/belief (accessed on 5 November 2022).

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Role: | ||

| Truck Drivers | 30 | 6 |

| Transport Managers | 8 | |

| Average Years of Service: | ||

| Truck Drivers | 26 | 12 |

| Transport Managers | 16 | |

| Average Age: | ||

| Truck Drivers (24–76 yrs) | 56 | 54 |

| Transport Managers (30–77 yrs) | 55 |

| Geographical Location | Total |

|---|---|

| New South Wales | 7 |

| Queensland | 14 |

| Victoria | 5 |

| South Australia | 0 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 0 |

| Tasmania | 0 |

| Western Australia | 9 |

| Northern Territory | 1 |

| Jurisdiction Type | Total Number of Drivers |

|---|---|

| Heavy Vehicle National Law | 26 |

| Workplace Health and Safety | 10 |

| Total Number of Drivers | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Category | Per trip | 9 | 25 |

| Per km | 14 | 39 | |

| Per tonne | 1 | 3 | |

| Per day | 1 | 3 | |

| Hourly | 11 | 30 | |

| Payment Motive | Incentive | 24 | 67 |

| Non-incentive | 12 | 33 |

| Load Types: | Total Number of Drivers | % |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk dangerous goods | 4 | 11 |

| Refrigerated goods | 5 | 14 |

| General freight | 17 | 47 |

| Bulk loads (soil, grain etc) | 5 | 14 |

| Oversize/Over-mass loads | 4 | 11 |

| Livestock | 1 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casey, G.J.; Miles-Johnson, T.; Stevens, G.J. “I’m Not Right to Drive, but I Drove out the Gate”: Personal and Contextual Factors Affecting Truck Driver Fatigue Compliance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111724

Casey GJ, Miles-Johnson T, Stevens GJ. “I’m Not Right to Drive, but I Drove out the Gate”: Personal and Contextual Factors Affecting Truck Driver Fatigue Compliance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111724

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasey, Gregory J., Toby Miles-Johnson, and Garry J. Stevens. 2025. "“I’m Not Right to Drive, but I Drove out the Gate”: Personal and Contextual Factors Affecting Truck Driver Fatigue Compliance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111724

APA StyleCasey, G. J., Miles-Johnson, T., & Stevens, G. J. (2025). “I’m Not Right to Drive, but I Drove out the Gate”: Personal and Contextual Factors Affecting Truck Driver Fatigue Compliance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111724