Abstract

Background: Adopting advanced digital technologies as diagnostic support tools in healthcare is an unquestionable trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their accuracy in suggesting diagnoses remains controversial and needs to be explored. We aimed to evaluate and compare the diagnostic accuracy of two free accessible internet search tools: Google and ChatGPT 3.5. Methods: To assess the effectiveness of both medical platforms, we conducted evaluations using a sample of 60 clinical cases related to urological pathologies. We organized the urological cases into two distinct categories for our analysis: (i) prevalent conditions, which were compiled using the most common symptoms, as outlined by EAU and UpToDate guidelines, and (ii) unusual disorders, identified through case reports published in the ‘Urology Case Reports’ journal from 2022 to 2023. The outcomes were meticulously classified into three categories to determine the accuracy of each platform: “correct diagnosis”, “likely differential diagnosis”, and “incorrect diagnosis”. A group of experts evaluated the responses blindly and randomly. Results: For commonly encountered urological conditions, Google’s accuracy was 53.3%, with an additional 23.3% of its results falling within a plausible range of differential diagnoses, and the remaining outcomes were incorrect. ChatGPT 3.5 outperformed Google with an accuracy of 86.6%, provided a likely differential diagnosis in 13.3% of cases, and made no unsuitable diagnosis. In evaluating unusual disorders, Google failed to deliver any correct diagnoses but proposed a likely differential diagnosis in 20% of cases. ChatGPT 3.5 identified the proper diagnosis in 16.6% of rare cases and offered a reasonable differential diagnosis in half of the cases. Conclusion: ChatGPT 3.5 demonstrated higher diagnostic accuracy than Google in both contexts. The platform showed satisfactory accuracy when diagnosing common cases, yet its performance in identifying rare conditions remains limited.

1. Introduction

Since the introduction of early data processing machines in the 1940s, researchers across diverse disciplines have been captivated by their possible uses, with researchers in the medical field showing particular interest [1]. As early as 1959, Brodman and colleagues demonstrated that a trained computerized system could identify patterns in a group of symptoms reported by patients and suggest possible diagnoses, performing comparably to physicians receiving the same information [2]. From that point forward, data analytics technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) gained prominence in several medical fields, including public health, medical image analysis, and clinical trials, among others [3].

The increasing capability of these tools to integrate information has allowed researchers to envision diagnostic applications far beyond what Broadman presented. It is now possible to input a patient’s symptoms into everyday search tools and receive a list of likely diagnoses [3,4]. Tang and Ng explored this utility in 2006, when they assessed the frequency of accurate diagnoses provided when specific disease symptoms were searched on Google, the leading internet search site [5].

In addition to search tools, new AI chatbots have recently been used to explore this field [6]. Among the most notable advancements is OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer, ChatGPT 3.5. Unlike conventional search engines that return pages based on keyword matching, ChatGPT 3.5 generates real-time responses, drawing from a vast database [7,8]. Internet users can access version 3.5 for free, as it is the most recent version available at no cost.

Given their capabilities for continuous and incremental learning, rapid summarization of textual data, and generation of natural language responses, large language models (LLMs) have been widely applied across various domains, notably in medical training [9]. These models efficiently assimilate and synthesize vast amounts of information, making them valuable tools for educational purposes in healthcare settings. In this setting, medical education has moved towards a competency-based education paradigm. Generative AI technologies have been increasingly employed in new competencies training for doctors and medical graduates [9]. AI-enhanced predictive models for risk stratification have shown great potential in the healthcare sector, especially in reducing diagnostic errors and improving patient safety.

In this context of evolving information technologies and their increasingly pervasive integration in medicine, this study aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy and compare the agreement of two prominent online search tools, Google and ChatGPT 3.5, for urological conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

This pilot study was conducted between April and June 2023, in which the diagnostic properties of the Google and ChatGPT 3.5 platforms were assessed. These tools were evaluated based on the responses to 60 clinical cases related to urological pathologies, divided into “prevalent conditions” and “unusual conditions”. Questions were formulated in Portuguese.

In the first group, 30 descriptions summarized the typical clinical presentation of prevalent urological diseases, published by the European Association of Urology and UpToDate guidelines (Table 1). In the second group, the remaining 30 cases were based on reports published between 2022 and 2023 in Urology Case Reports, selected based on the typicality of their manifestations (Table 2). Questions requiring extensive evaluation for specific diagnoses were excluded.

Table 1.

Prevalent urological conditions.

Table 2.

Unusual urological conditions.

Each clinical case was inputted into Google Search and ChatGPT 3.5, and the results were categorized as “correct diagnosis”, “likely differential diagnosis”, and “incorrect diagnosis”, according to the blind and random judgment of a panel of three experts. For Google Search, a new incognito window in the browser with no linked account was used to minimize any influence from previous search history, and the first three displayed results were considered for diagnostic categorization. For ChatGPT 3.5, a specific individual account was created to reduce the influence of prior searches. Regarding the use of AI or AI-assisted technologies, Google and ChatGPT 3.5 were employed exclusively to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of each AI platform based on the responses to 60 clinical cases related to urological pathologies.

The findings of this study were described in absolute numbers and corresponding percentages. The Chi-square test was used for proportion comparison, and the Kappa test was employed to assess agreement between the instruments. “All tests are two-tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant”. We utilized GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 for Windows, provided by GraphPad Software from Boston, MA, USA, for the statistical analysis and to create the graphical representations of the data.

3. Results

Both platforms showed promising results when dealing with prevalent urological cases in daily practice. Google Search demonstrated a correct diagnosis, likely differential diagnosis, and incorrect diagnosis in 16 (53.3%), 7 (23.3%), and 7 (23.3%) of the clinical cases. ChatGPT 3.5 outperformed Google, providing a correct diagnosis in 26 (86.6%) cases and offering likely differential diagnoses in 4 (13.3%) cases, with no incorrect diagnoses (p = 0.004).

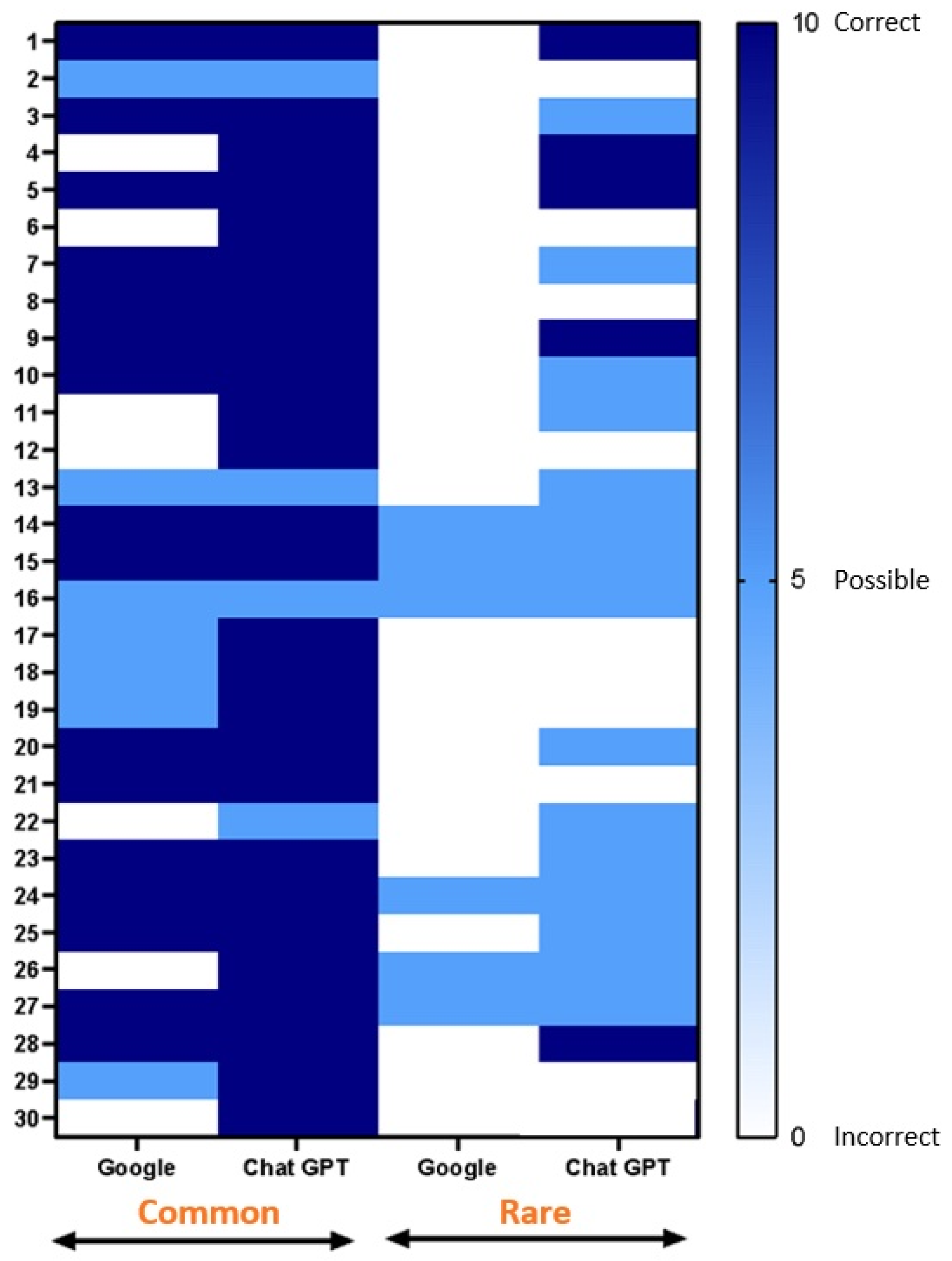

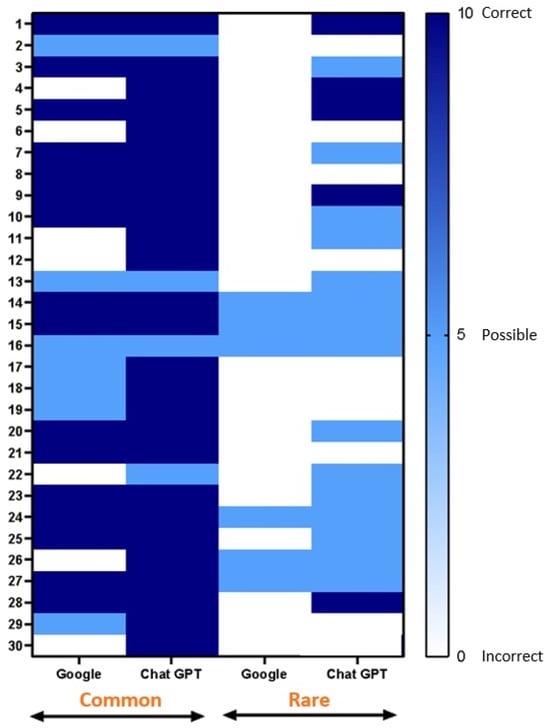

Regarding the unusual urological conditions, the performances of the two platforms significantly diverged. Google could not provide any correct diagnosis but offered likely differential diagnoses in six (20%) cases. Google outputted an incorrect diagnosis in the remaining 24 (80%) cases. Nevertheless, ChatGPT 3.5 had moderate success in diagnosing rare conditions, with a correct diagnosis in five (16.6%) cases. Notably, it provided a likely differential diagnosis in 15 (50%) cases. However, it is important to note that the platform provided an incorrect diagnosis in 10 cases, constituting 33.3% of the instances evaluated (p = 0.0012). The results are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic accuracy of Google and ChatGPT for urologic clinical cases. Common cases are represented on the left side, and rare cases are on the right. To determine the diagnostic accuracy of each platform, the outcomes were classified into three categories: correct diagnosis (dark blue), likely differential diagnosis (light blue), and incorrect diagnosis (white).

In a comparative accuracy analysis, ChatGPT 3.5 was significantly superior to Google. The platform provided correct diagnoses or proposed suitable differential diagnoses in 50 (83.3% 71.7–90.80 95%CI) out of 60 cases, in contrast to Google’s performance of 29 (48.3% 36.1–60.7 95%CI) out of 60 cases (OR = 3.62 1.50–8.73 95%CI p < 0.001). There was low agreement between both diagnostic instruments (Kappa = 0.315).

4. Discussion

This study showed that ChatGPT 3.5 demonstrated superior diagnostic capabilities compared to Google in real-life urological scenarios. Both platforms varied in performance depending on the complexity and rarity of urological conditions. While Google remained moderately effective in prevalent urological cases, its performance reduced significantly in unusual urological conditions. ChatGPT 3.5 showed high diagnostic accuracy in common urological diseases and moderate success in diagnosing rare and uncommon conditions.

In this comparative study, the LLMs demonstrated proficiency in extracting information and responding to structured inquiries, achieving accuracy rates ranging from 53.3% to 86.6%. ChatGPT, in particular, operates by sequentially predicting word fragments until a complete response is formed. Its architecture effectively processes and integrates complex clinical data, yielding contextually relevant interpretations [10]. In contrast, Google often retrieves more generalized information. ChatGPT utilizes a comprehensive, curated medical dataset, including peer-reviewed articles and clinical case studies, which enhances its ability to provide context-aware responses that adhere to contemporary medical standards. This specialized approach contributes to ChatGPT’s higher diagnostic accuracy in the nuanced field of urology. While ChatGPT is capable of incremental learning, allowing it to retain information from previous interactions to refine future responses [11], this feature was unlikely to influence the results in this study due to using a specific individual account designed to minimize the impact of prior searches.

The study outcomes corroborate the importance of acknowledging the fluctuating efficacy of these tools across various clinical contexts, highlighting both their advantages and the domains that require enhancement. These findings also raise essential questions about the role of AI-based platforms like ChatGPT 3.5 in clinical decision making and education. The exponential growth in medical knowledge exacerbates the challenges faced by healthcare professionals. Estimates suggest that the rate at which medical knowledge expands has significantly accelerated—from taking 50 years to double in 1950, down to just 73 days in 2020 [12]. These rapid advances mean medical students must master 342 potential diagnoses for 37 frequently presented signs and symptoms before graduating [13]. This amount of information can be overwhelming and underscores the growing need for accurate and more efficient diagnostic tools to assist physicians and other healthcare providers.

Internet search engines such as Google have been around for a while and have progressively been utilized within the healthcare and educational sectors [14,15]. In 1999, Graber and colleagues assessed the capacity of online search engines in resolving medical cases, finding that these platforms could correctly answer half of the questions [14]. By 2006, Google had already become the dominant online search tool, providing correct diagnoses in 58% of cases in Tang and Ng’s study [5]. Another study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of medical students before and after consulting Google and PubMed, noting a not statistically significant but interesting 9.9% increase in diagnostic accuracy [16].

More recently, chatbots, which combine AI with messaging interfaces, have emerged as precise tools for generating direct responses [17,18]. A Japanese study showed that ChatGPT 3 achieved a correct diagnostic rate of 93.3% when considering a list of ten probable differential diagnoses [19]. The same platform demonstrated an accuracy rate of 80% in questions about cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and an accuracy of 88% in breast cancer prevention and screening [20,21].

In the field of urology, ChatGPT 3.5’s performance has been variable. In one study, the platform correctly answered 92% of pediatric urology questions [22]. However, the platform’s performance was reduced to 52% in another study on general urological cases [23]. As illustrated by Huynh and colleagues, ChatGPT 3.5 performed poorly in the American Urological Association’s 2022 self-assessment study program, scoring below 30% [24]. Studies evaluating the accuracy of information on urological conditions provided to the general public have shown that while the responses were generally acceptable, they also contained significant inaccuracies [25,26].

We are observing the beginning of a new era in the history of medical education. The COVID-19 pandemic rapidly increased the use of new technologies in medical competencies training. This surge in adoption coincides with the release of ChatGPT, which has gained widespread recognition in educational settings by both teachers and students. At the same time, there have been quick policy adjustments regarding AI’s role in writing and academic publishing [27]. Educational leaders now face the crucial task of understanding the extensive impact of these changes across all aspects of health education and ethical dilemmas [9].

The current study provides valuable insights into existing research by directly comparing the diagnostic effectiveness of Google and ChatGPT 3.5 for urological conditions. Our results indicate that ChatGPT 3.5 outperformed Google in common and rare cases. While the platform showed high precision in diagnosing common urological conditions, it demonstrated moderate success with rarer diseases. These findings offer a promising perspective for integrating such tools in medical education and clinical workflows.

These platforms can assist urological researchers in analyzing and interpreting data, improving grammar and clarity in scientific manuscripts, and creating educational material. The role of these tools should be viewed as supplemental to the expertise of doctors and healthcare professionals providing patient care. Given the identified limitations, it is evident that both platforms require improvements. The ongoing process of expanding access to medical databases and continuous algorithmic training will increase its future utility. Ethical considerations cannot be overlooked either. There must be extensive discussion about the quality of information these platforms provide and how user privacy is ensured, as sensitive data may be involved. As these platforms evolve, their utility as diagnostic tools may become more robust, promoting more innovative and secure healthcare applications.

Currently, LLMs face significant limitations in medical decision making and diagnostics, including a lack of access to copyrighted private databases, a propensity for generating inaccurate or fabricated information (“hallucinations”), the unpredictability of responses, and constraints on training datasets [10]. The choice of cases included in this study could influence outcomes if they are not representative of the typical spectrum of urological conditions seen in clinical practice. Both platforms’ performance can vary significantly based on how questions are phrased. A study’s reliability may be affected if the prompts do not accurately reflect typical user queries or clinical scenarios. Both ChatGPT and Google continually update their algorithms. The results might not reflect the performance of newer or updated versions of the models. Finally, the diagnosis categories were determined by a panel of experts whose judgments could introduce subjective bias. The criteria for categorization (correct diagnosis, likely differential diagnosis, incorrect diagnosis) may not be uniformly applied.

Despite these challenges, the future of LLMs in medical diagnostics looks promising due to rapid advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms. These models are becoming more proficient at processing the extensive medical literature and patient data, continually improving their diagnostic algorithms. The inclusion of specialized datasets, such as those covering rare diseases or intricate clinical scenarios, enhances their accuracy and relevance in medical settings. As training becomes more comprehensive and detailed, LLMs’ capacity to deliver precise, contextually appropriate medical advice is expected to evolve, significantly enhancing clinical decision support and revolutionizing patient care outcomes. This research paves the way for further research on integrating AI-based tools such as ChatGPT into clinical practice. This approach aims for a quick, reliable diagnosis and potentially enhances patient outcomes while augmenting human expertise.

Our study contributes to a broader discussion about the evolving role of technology in healthcare, specifically in urology, where accurate and timely diagnosis is often critical to treatment success and patient well-being.

5. Conclusions

We demonstrated that ChatGPT 3.5 exhibited superior diagnostic accuracy compared to Google in prevalent and rare urological scenarios. ChatGPT 3.5 displayed acceptable accuracy in cases of habitual conditions but was still relatively limited in rare cases. Such findings allow us to glimpse some of the possible uses of these tools in educational and training processes. Access to medical databases and ongoing development can bring considerable advances, enabling even more robust, innovative, and secure tools and possibly assisting us in caring for people.

Author Contributions

G.R.G., C.M.G. and J.B.J. designed the study. G.R.G. and J.B.J. performed the data acquisition. G.R.G., C.M.G. and J.B.J. analyzed and interpreted data and statistics; G.R.G., C.S.S., R.G.F., V.A., R.B.T., J.C.Z.C., C.M.G. and J.B.J. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this manuscript, we utilized Grammarly AI software (https://www.grammarly.com/ai) to enhance the grammatical quality. The authors developed the manuscript’s content independently with the assistance of AI software. The authors thank the Uros—Grupo de Pesquisa, a collaborative research group at Medical School—Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), for supporting this research. Uros—Grupo de Pesquisa: Ana Clara Silva Oliveira, Anna Paloma Martins Rocha Ribeiro, Ana Samiry da Silva Gomes, Caíque Negreiros Lacerda, Daniela Azevedo da Silva, Fernanda Santos da Anunciação, Isa Clara Santos Lima, Jair Bomfim Santos, Lucas Neves de Oliveira, Lucas Santos Silva, Matheus Maciel Pauferro, Marjory dos Santos Passos, Monique Tonani Novaes, Nathália Muraivieviechi Passos, Randson Souza Rosa, Rodolfo Macedo Cruz Pimenta, Seeley Joseph Machado Monteiro, Taciana Leonel Nunes Tiraboschi, Thifany Novais de Paula, Tyson Andrade Miranda, Virna Silva Mascarenhas, Williane Thamires dos Santos.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mahoney, M.S. The History of Computing in the History of Technology. Ann. Hist. Comput. 1988, 10, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodman, K.; Van Woerkom, A.J.; Erdmann, A.J.; Goldstein, L.S. Interpretation of Symptoms with a Data-Processing Machine. Arch. Intern. Med. 1959, 103, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Antari, M.A. Artificial Intelligence for Medical Diagnostics—Existing and Future AI Technology! Diagnostics 2023, 13, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ng, J.H.K. Googling for a diagnosis—Use of Google as a diagnostic aid: Internet based study. Br. Med. J. 2006, 333, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Pedraza, A.M.; Gorin, M.A.; Tewari, A.K. Defining the Role of Large Language Models in Urologic Care and Research. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, J.M.; Kohane, I.S.; Leong, T.-Y.; Lee, P.; Bubeck, S.; Petro, J. Chatbot for Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1220–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, L.O. ChatGPT for medical applications and urological science. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2023, 49, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.M.; Lundy, N.N.; Issenberg, S.B.; Chandran, L. Reimagining Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Undergraduate Medical Education in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e50903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.J.; Pillai, A.; Deng, J.; Guo, E.; Gupta, M.; Paget, M.; Naugler, C. Assessing the research landscape and clinical utility of large language models: A scoping review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT [Internet]. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Densen, P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2011, 122, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Urushibara-Miyachi, Y.; Kikukawa, M.; Ikusaka, M.; Otaki, J.; Nishigori, H. Lists of potential diagnoses that final-year medical students need to consider: A modified Delphi study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, M.A.; Bergus, G.R.; York, C. Using the World Wide Web to Answer Clinical Questions: How Efficient Are Different Methods of Information Retrieval? J. Fam. Pract. 1999, 49, 520–524. [Google Scholar]

- Giustini, D. How Google is changing medicine. Br. Med. J. 2005, 331, 1487–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Ntziora, F.; Makris, G.C.; Malietzis, G.A.; Rafailidis, P.I. Do PubMed and Google searches help medical students and young doctors reach the correct diagnosis? A pilot study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulou, E.; Moussiades, L. Chatbots: History, technology, and applications. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2020, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Dunn, A.G.; Tong, H.L.; Kocaballi, A.B.; Chen, J.; Bashir, R.; Surian, D.; Gallego, B.; Magrabi, F.; Lau, A.Y.S.; et al. Conversational agents in healthcare: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirosawa, T.; Harada, Y.; Yokose, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Kawamura, R.; Shimizu, T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Differential-Diagnosis Lists Generated by Generative Pretrained Transformer 3 Chatbot for Clinical Vignettes with Common Chief Complaints: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, Y.H.; Samaan, J.S.; Ng, W.H.; Ting, P.-S.; Trivedi, H.; Vipani, A.; Ayoub, W.; Yang, J.D.; Liran, O.; Spiegel, B.; et al. Assessing the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, H.L.; Ambinder, E.B.; Bahl, M.; Oluyemi, E.T.; Jeudy, J.; Yi, P.H. Appropriateness of Breast Cancer Prevention and Screening Recommendations Provided by ChatGPT. Radiology 2023, 307, e230424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, U.; Yildiz, O.; Meric, A.; Ayranci, A.; Gelmis, M.; Sarilar, O.; Ozgor, F. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in answering questions related to pediatric urology. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 20, 26.e1–26.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocci, A.; Pezzoli, M.; Lo Re, M.; Russo, G.I.; Asmundo, M.G.; Fode, M.; Cacciamani, G.; Cimino, S.; Minervini, A.; Durukan, E. Quality of information and appropriateness of ChatGPT outputs for urology patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2023, 27, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.M.; Bonebrake, B.T.; Schultis, K.; Quach, A.; Deibert, C.M. New Artificial Intelligence ChatGPT Performs Poorly on the 2022 Self-assessment Study Program for Urology. Urol. Pract. 2023, 10, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczesniewski, J.J.; Tellez Fouz, C.; Ramos Alba, A.; Diaz Goizueta, F.J.; García Tello, A.; Llanes González, L. ChatGPT and most frequent urological diseases: Analysing the quality of information and potential risks for patients. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 3149–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiles, B.B.; Bird, V.G.; Canales, B.K.; DiBianco, J.M.; Terry, R.S. Caution! AI Bot Has Entered the Patient Chat: ChatGPT Has Limitations in Providing Accurate Urologic Healthcare Advice. Urology 2023, 180, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, J. Best practices for implementing ChatGPT, large language models, and artificial intelligence in qualitative and survey-based research. JAAD Int. 2023, 14, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).