Abstract

Objective: To understand the methodological approaches taken by various research groups and determine the kinematic variables that could consistently and reliably differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals. Methods: MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL Complete via EBSCO, EBSCOhost, SPORTDiscus, and Scopus were searched from inception until 31 December 2021, using key terms related to concussion, mild traumatic brain injury, gait, cognition and dual task. Studies that reported spatiotemporal kinematic outcomes were included. Data were extracted using a customised spreadsheet, including detailed information on participant characteristics, assessment protocols, equipment used, and outcomes. Results: Twenty-three studies involving 1030 participants met the inclusion criteria. Ten outcome measures were reported across these articles. Some metrics such as gait velocity and stride length may be promising but are limited by the status of the current research; the majority of the reported variables were not sensitive enough across technologies to consistently differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals. Understanding variable sensitivity was made more difficult given the absence of any reporting of reliability of the protocols and variables in the respective studies. Conclusion: Given the current status of the literature and the methodologies reviewed, there would seem little consensus on which gait parameters are best to determine return to play readiness after concussion. There is potential in this area for such technologies and protocols to be utilised as a tool for identifying and monitoring concussion; however, improving understanding of the variability and validity of technologies and protocols underpins the suggested directions of future research. Inertial measurement units appear to be the most promising technology in this aspect and should guide the focus of future research. Impact: Results of this study may have an impact on what technology is chosen and may be utilised to assist with concussion diagnosis and return to play protocols.

1. Introduction

Concussions are a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) that individuals can experience through sport that are frequently missed or underestimated resulting in individuals returning to sport earlier than they should, increasing the risk of sustaining a musculoskeletal injury [1,2] or leading to further brain damage if a second concussion is experienced in close proximity to the first event [3,4]. There is a need to have protocols that can assess the extent of the concussion experienced while also determining readiness for return to activity. Typical methods of assessing concussions are clinical assessments which consider physical and mental attributes such as balance and memory, respectively [5]. These assessments are generally tested as two separate elements, yet researchers have suggested that a dual task (DT) assessment that combines physical and mental testing provides a more accurate understanding of concussion than standalone walking and cognitive assessments [6,7,8,9,10].

Protocols incorporating a cognitive task alongside a gait assessment are becoming frequently utilised to evaluate the effects of concussion [11,12,13]. The Stroop test, which involves participants responding to an auditory or visual cue whilst undergoing locomotion, requires equipment to facilitate the test and record the accuracy and speed of responses [6,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Other more common cognitive dual tasks include reciting the months of the year in reverse order, subtracting by sixes or sevens from a given number, or spelling common five letter words in reverse, while walking along a level walkway [7,11,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Gait variables such as walking speed, stride length and cadence are quantified to determine any variability through the introduction of a cognitive task [11,12,23,32,33].

To measure the physical variables, 3D motion capture (3D MOCAP) and/or force plates are commonly used to differentiate between concussive diagnoses by assessing postural balance and control [6,7,9,11,14,15,16,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,34]. Inertial measurement units [8,31,32,33,35,36] and accelerometers [18] are other forms of technology that have been used for DT concussion gait analysis. However, whether certain technologies and/or certain variables are better suited to discriminating between concussed and non-concussed diagnoses is unknown. Of particular interest to the authors and that which provides the purpose of this scoping review was understanding the methodological approaches taken by various research groups and determining those variables that could consistently and reliably differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

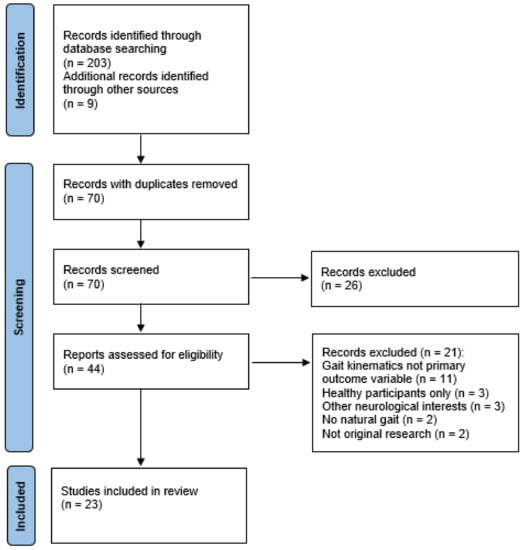

A scoping review was conducted guided by the standards presented by the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [37]. This review aimed to examine the methodological approaches, determine those variables that could consistently and reliably differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals, identify limitations of current technologies and related protocols and, finally, to outline areas of future research for concussion assessment. MEDLINE via PubMed, CINAHL Complete via EBSCO, EBSCOhost, SPORTDiscus and Scopus databases were searched for relevant articles from the inception of the databases until 31 December 2021. The search strategy included five concepts (concussion, mTBI, cognition, gait and dual task) and a combination of key words to adapt to each database. From the initial screening, 70 articles were identified, and titles and abstracts were screened to determine relevance to review. Forty-four full-text articles were examined to determine inclusion eligibility. Reference lists of included articles were searched for other potentially relevant information. A total of 23 articles were identified as being eligible for full-text review and subsequent analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of the study selection process. The flow of information through the review phases is depicted, detailing the number of articles that were included and excluded in the review, with reasons for exclusions.

2.2. Study Selection

Studies were included if a steady state DT walking assessment was used; the DT involved a cognitive task paired with a steady state gait task; individuals had a concussion, either through sport or other activity, or mild traumatic brain injury with healthy individuals used as control subjects; and kinematic walking measures were reported. There were no restrictions placed on the age or gender of participants. Articles were excluded if steady-state gait was not the primary dependent variable of cognitive task performance, such as reaction time, tandem gait, balance or gait termination time. Review articles and case studies were excluded. Full-text articles were retrieved and scanned when inclusion could not be determined by screening titles and abstracts. Articles that involved all healthy participants or those with a more severe brain injury were excluded from the analysis. Risk of bias was mitigated in this research, given the focus was more a technological/methodological critique rather than a review of the outcome measures and findings as such.

2.3. Data Extraction

One reviewer (C.M.) extracted the data using a customised designed standardised Excel database (version 2201, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) which was validated by a secondary reviewer (J.C.). General study information (i.e., author, year), subject characteristics (i.e., sample size, age, concussion history, sport/activity), type of study (i.e., cross-sectional and prospective), methods of assessment (i.e., testing equipment, environment, protocol) and primary outcome measures (e.g., means and standard deviations of average gait velocity) were extracted. Descriptive information relating to the sport and performance level were used to categorise each of the participants. A wide array of definitions for elite, sub-elite and novice athletes exist (30). Therefore, in order to clearly differentiate between groups with concussions, skill level was grouped according to the level at which participants were competing. National or regional representatives were classified as elite athletes. Participants competing at university or collegiate (Uni/Col) were categorised as sub-elite. Recreational athletes were deemed as such (Rec) and those who did not experience a sport-related concussion were classified as NoSport. Adolescent athletes were categorised as high school (HS) athletes.

2.4. Role of the Funding Source

This scoping review was funded by Movement Solutions. The funder played no role in the design, collation, synthesis and writing of this review.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

Eight of the twenty-three articles (35%) employed prospective designs, with assessments at two to five time points over the course of the study [6,7,11,18,24,25,33,38]. Fifteen articles (65%) utilised cross-sectional designs [12,13,15,16,20,21,22,23,28,31,32,36,39,40,41]. The total number of participants used across the studies was 1030, with 474 participants categorised as concussed subjects and 556 participants categorised as non-concussed controls. Due to the lack of detail provided, it is unclear as to whether there was any repeated usage of sample groups. Grade II concussion parameters described by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) were detailed in seven articles [11,21,22,23,24,25,28] and seven articles used the latest Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport (CsoCiS) [6,7,18,31,32,38,40]. One article used the Veteran Health Affairs/Department of Defence mTBI criteria for concussion diagnosis [36] and seven articles did not state the method of concussion diagnosis [13,15,20,33,39,41]. Concussions were diagnosed by certified athletic trainers and/or medical professionals in 17 articles [6,7,11,12,13,15,21,24,25,28,31,32,33,38,39,40,41]; however, the remaining six did not state who diagnosed the concussions of the participants [16,18,20,22,23,36].

3.2. Participants

From the 1030 participants, 54% were male and 49% were female; the sex of the participants was not reported in one study [25]. There was insufficient detail provided in each of the studies to determine if there was any overlap of sample groups. The age of participants most commonly ranged between 13 and 22, often being high school and university students and athletes. One study involved adults over 64 years of age [39]. The majority of concussions experienced by participants were sport-related, with the sporting level ranging from elite athletes, intercollegiate athletes, and high school athletes to local and recreational athletes. Three studies included subjects who had sustained a concussion through activities of daily living [24,25,38]. Subjects experienced concussion through a variety of sports with the most common sports reported being football, American football and ice hockey (n = 2) [31,33].

3.3. Gait Protocol

The description of the gait protocols can be seen in Table 1. The most common distance covered for the protocols was between 8 and 10 m (n = 11 [11,12,13,15,21,22,24,25,28,33,39]). All 23 articles (100%) involved participants walking at a self-selected pace, 14 of which had participants walking barefoot [6,7,11,18,21,23,24,25,31,32,33,36,38,40]. Testing locations were described as a laboratory (n = 6) [11,12,13,15,20,23], walkway or hallway (n = 12) [6,7,18,21,22,24,25,31,33,38,39,41] or were unspecified (n = 5) [16,28,32,36,40]. The most frequent number of trials used across the articles was five trials per testing condition (n = 9) [11,12,20,21,25,28,32,39,40], followed by between eight and ten trials (n = 4) [6,7,15,38]. The amount of practice trials varied from one [18], four [13,15] and “several” [22,23,28]. In most circumstances (17 articles–74%) it was not stated whether any practice or familiarisation took place. Inter-trial rest periods were described as being 30 s [12] and “several minutes” [23]; however, for the most part (91% of articles) the rest periods were not detailed. Level walking as a single-task (ST) assessment protocol was used in 21 studies [6,7,11,12,13,15,16,20,21,22,23,24,25,28,31,32,33,36,38,39,41]; two articles did not include a ST assessment [18,40]. There was considerable variation in the number of testing occasions for each study: eight articles had one testing occasion up to 72 h [21,23,28], 5–7 days [20,31,32,40] or 4–15 weeks [41] post-concussion; three articles included four testing occasions at time points of up to 72 h, 5–7 days, 2 weeks and 1 month post-concussion [11,24,25]; five testing occasions were utilized in four articles at time points of up to 72 h, 5–7 days, 2 weeks, 1 month and 2 months post-concussion [6,7,18,38]; one article [33] had two testing occasions with the initial occasion up to 21 days post-concussion and the second occasion occurring once no symptoms were being experienced; one article incorporated one testing occasion and did not detail how soon participants were recruited following a concussion being experienced [22]; six articles had one testing occasion, where participants had experienced a concussion during their lifetime (“history of concussion”) [12,13,15,16,36,39].

Table 1.

Sample groups and protocols from reviewed studies.

3.4. Cognitive Task

Eight different cognitive tasks were utilised in the DT gait protocols across the 23 studies (see Table 1). These included: spelling a common five letter word backwards; subtracting by sixes and/or sevens; reciting the months of the year in reverse; auditory Stroop; visual Stroop; and Brooks’ spatial memory task, verbal fluency, and arithmetic. The most commonly used DT cognitive tasks (n = 14) were spelling common five letter words backwards, subtracting by sixes and/or sevens and reciting the months of the year in reverse [6,11,16,20,21,22,23,24,25,28,31,32,33,40,41]. An auditory Stroop assessment was the next most common cognitive task (n = 6) [6,7,18,20,36,38], followed by a visual Stroop test [13,15,16] and a verbal fluency task [13,16,41] (both n = 3). All 23 studies included at least one DT assessment. In terms of the number of cognitive tasks used within each methodology, a single DT assessment was used in seven articles [6,12,15,18,36,38,39], two different DT tests were used in two articles [20,41], three different cognitive tasks were used in six articles [7,11,13,16,24,25] and eight articles randomised participants’ single DT trial from three DT options [21,22,23,28,31,32,33,40].

3.5. Equipment

The equipment used in the articles reviewed can be observed in Table 2. Motion capture (3D MOCAP) was used in 16 articles [6,7,11,13,15,16,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,28,38,39]. The number of markers placed on bony landmarks mostly ranged between 25 and 32 (n = 12) [6,7,11,18,21,22,23,24,25,28,38,39], with one group of researchers utilising 16 markers [20] and three research groups using four markers [13,15,16]. The number of cameras used ranged between six and ten (n = 12) [6,7,11,16,18,21,22,23,24,25,28,38]; however, four research groups did not state how many cameras were used [13,15,20,39]. The most widely used sampling rate was 60 Hz (n = 10) [6,7,11,18,21,22,23,25,28,38], where other researchers sampled data at 100 Hz [15], 120 Hz [20] and 240 Hz [39]. The sampling rate was not stated in three papers [13,16,24]. Marker trajectory data was filtered using a low-pass fourth order Butterworth filter by 11 research groups (69%), with a cut-off filter of 6 Hz [13,15] and 8 Hz [6,7,11,16,21,22,23,25,28,38] being the most common cut off frequencies. The method of data filtering was not stated in five articles [16,18,20,24,39].

Table 2.

Equipment and technologies utilised in reviewed studies.

Nine research groups utilised force plates in conjunction with 3D MOCAP [6,7,11,21,22,23,24,25,38]; two in-series force plates were used in six articles [11,21,22,23,24,25] and three articles used three in-series force plates [6,7,38]. A sampling rate of 960 Hz was used in all but two articles [6,7,11,21,22,23,25,38], with the sampling rate not being specified in these studies [20,24].

Inertial measurement units (IMU) were utilised by five research groups [31,32,33,36,40]. IMUs were placed on the lumbosacral junction and dorsum of each foot (n = 4) and recorded data at a sampling rate of 128 Hz [31,32,33,40]. One article placed IMUs on the dorsum of each foot, forehead, lumbar spine and sternum, with the sampling rate not being specified [36]. A single research group utilised an accelerometer in combination with 3D MOCAP [18]. The accelerometer was attached at the L5 vertebrae and collected data at a sampling rate of 128 Hz.

Three articles used a microphone to record participants’ responses during their respective DT [6,7,15]. A GAITRite walkway, sampling at 80 Hz, was used to collect gait data in one article [12]. One article utilised a manual stopwatch to time participants’ gait [41].

3.6. Outcome Measures

The outcome measures of interest are detailed in Table 3. Gait velocity was the most studied measure in terms of identifying concussive gait impairments. No significant differences in gait velocity across all monitored time periods were reported in ten articles [6,12,13,15,20,21,24,25,39,41], whereas significant differences were reported in 13 articles [7,11,16,18,22,23,28,31,32,33,36,38,40]; the most common differences were found with concussed individuals having a slower gait velocity at <72 h after injury (n = 7) [7,11,18,22,23,28,38] and 5–7 days after injury (n = 5) [7,18,31,32,40]. Concussed subjects had a slower gait velocity in four articles [6,7,21,24], yet this difference was not enough to be considered significant.

Table 3.

Variables and outcome measures in reviewed articles.

In terms of the stride/step parameters (length, time, width), stride/step length seemed to be the more sensitive of the measures, with six out of 12 research groups reporting significant differences between concussed and non-concussed gait [11,21,32,33,36,40]. Significant differences in stride/step length were reported at <72 h post-concussion (n = 2) [11,21], 5–7 days (n = 2) [20,32], 2 weeks (n = 2) [11,33] and with historic concussions (n = 2) [33,36]. Five research groups utilised stride time, with two groups reporting significant differences at <72 h post-concussion [22,23] and one group reporting significant differences with historic concussion [36]. All eight of the articles that reported stride/step width measures found no significant differences [6,11,12,21,22,23,28,39].

Regarding cadence and double support, there was a paucity of researchers investigating the sensitivity of these measures over time, with double supporting having largely been discussed with historic concussion subjects only (n = 4) [12,33,36,39]. Two out of four articles which included double support analysis found a significant increase in double support duration for historically concussed individuals [12,36].

Of the five articles that used IMUs to differentiate between concussed and non-concussed subjects, significant differences were reported regarding gait speed (n = 5) [31,32,33,36,40], stride length (n = 4) [32,33,36,40], cadence (n = 2) [32,33], stride time (n = 1) [36] and double support (n = 1) [36].

3.7. Reliability

None of the studies reviewed established the reliability of the specific protocols they implemented. Four of the articles reviewed referred to reliability of the equipment and protocols established in other studies (Table 4). On reviewing these studies, two research groups investigated the reliability of GAITRite walkway variables, which only one reviewed article used [12]. Montero-Odasso et al. [42] considered gait velocity, step length, stride length, step time, stride time and double support time in single and dual task walking with a cognitively impaired elderly population (average age 76.6 ± 7.3 y). The absolute consistency (coefficient of variation (CV)) ranged from 6.36–18.28% for ST and 11.02–19.27% for DT. In terms of relative consistency, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) ranged from 0.80–0.97 for ST and 0.93–0.97 for DT. The GAITRite walkway was also investigated by Paterson et al. [43], however, the comparison was between younger (20.08 ± 0.7 y) and older (67.93 ± 7.8 y) populations. CVs ranged from 2.33–4.08 %. In terms of relative consistency, ICCs ranged from 0.66–0.94.

Table 4.

Reliability articles cited in reviewed articles.

The GAITRite walkway was also utilised in conjunction with inertial sensors to establish reliability of other technologies using continuous walking protocols. Moore et al. [44] sought to establish the reliability of a wearable accelerometer (AX3) with stroke patients. Within the variables of step velocity, step length, step time, and stance time, the absolute agreement was good (ICC: 0.744–0.797) between AX3 and GAITRite, and moderate–excellent (ICC: 0.831–0.923) between AX3 and Opal inertial sensors. Morris et al. [45] compared GAITRite with Opal inertial sensor data analysed via Mobility Lab across young adults, older adults and adults with Parkinson’s disease. Gait velocity, stride length, cadence and stride time had moderate–excellent absolute agreement (ICC: 0.741–0.998); however, double support time had poor absolute agreement (ICC: 0.213–0.716).

To establish reliability of cognitive tasks while walking, Howell et al. [30] used IMUs to investigate the ST and DT gait of collegiate athletes in both contact and non-contact sports (19.2 ± 1 y) through gait speed, cadence and stride length. This research group only reported relative consistency: the ICCs ranged from 0.68–0.80 for ST and 0.73–0.85 for DT walking.

4. Discussion

Concussions are an increasingly common mild traumatic brain injury that are experienced in sport. To limit misdiagnosis of individuals with concussion and to assist with return to play, there is a need for assessment protocols that incorporate both cognitive and physical elements to allow for a more accurate evaluation of concussive impairment. Assessing gait whilst performing a cognitive task is one such assessment protocol and formed the focus of this review. Of particular interest were the methodological approaches taken by various research groups and determining those protocols and/or variables that could consistently differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals.

The participants involved across the reviewed articles were diverse in sample size (12–122), age (12–68 y), sport (football, cheerleading, horseback riding, to name a few) and competition level (recreational–elite). Sixty-one percent of the reviewed study protocols required participants to partake barefoot, which presents an interesting issue in terms of whether testing should take place with shoes or barefoot, which potentially may affect the clinical outcomes. Counting or spelling backwards seemed to be the easiest of dual tasks to implement given the ease of administration and lack of equipment required, negating the need for extensive set up time. It is suggested that these cognitive tests should be randomised to limit any learning effects.

The most widespread use of equipment involved 3D MOCAP and force plates. While the equipment may be considered to provide more precise information, the cost of the equipment and the expertise required to run, process and analyse the data is a restrictive factor for assessing concussions outside of conducting research. A significant time cost is also involved with processing the information recorded from MOCAP and force plates to generate data for analysis. Equipment that does not require as extensive proficiency or time to process and analyse collected data, such as with inertial sensor technology, may offer a more accessible tool for practitioners in diagnosing and monitoring concussion.

The most common distance that participants were assessed over with dual task gait was 8–10 m. This was largely a result of the space in which the testing was conducted and the available equipment e.g., 2–3 force plates in series and/or in ground with 3D MOCAP. The authors feel that the set-up of such equipment is a limitation, in that testing is restricted to a particular environment (i.e., sports laboratory) which may impede the initial diagnosis and subsequent monitoring of concussed individuals, thus, being detrimental for quicker return to play. More portable technologies (i.e., IMUs) may provide a more accessible and convenient tool that can be utilised within a wide range of environments. If dual task gait analysis of concussive diagnosis is to have any real-world utility, then serious consideration of other technological approaches will be needed.

None of the 3D MOCAP and force plate outcome measures reported were found to be sensitive enough to consistently determine differences between concussed and non-concussed diagnosis during DT walking. Gait velocity, stride/step length and stride/step width were the variables that were most reported on, with significant differences being reported by 31% [11,18,22,23,38] and 25% [11,21] of the reviewed articles for gait velocity and stride/step length, respectively, but no article was found to report significant differences in stride/step width. The majority of articles found no significant differences across the gait variables of interest. Comparatively, articles that utilised IMUs to measure gait velocity and stride/step length reported significant differences in 100% [31,32,33,36,40] and 80% [32,33,36,40] of the articles, respectively. This may indicate that IMU utilisation enables increased accuracy and/or sensitivity due to a closer interaction with the gait movement patterns. It also needs to be noted that the diagnostic value of any gait analysis is enhanced when data is collected over multiple testing occasions. This historic data provides a better insight into any aberrations that may need addressing.

The emergence of inertial sensor technology [31,32,33,36,40] might provide a viable alternative to MOCAP and force plate analyses. The outcome variables reported by the articles that utilised IMUs showed promising consistency in differentiating between concussed and non-concussed diagnoses. It would be interesting to understand whether different sensor placements (e.g., in-sole sensors) offer added sensitivity and accuracy, compared to the sensor arrangements in the bulk of the studies reviewed (lumbosacral, dorsum and foot).

One of the most concerning aspects of all the articles reviewed was the absence of any reporting of the reliability of the outcome measures of interest. Understanding the “noise” or unexplained variability associated with a measure is fundamental to interpreting findings. Only one research group [12] provided evidence regarding the reliability of the GAITRite walkway in elderly and young cohorts, citing the work of Paterson et al. (2008) [43] and Montero-Odasso et al. (2009) [42]. The results were markedly different in that Paterson et al.’s [43] findings were acceptable (CV < 4.08%; ICCs 0.66–0.94), whereas the absolute consistency of Montero-Odasso et al. [42] was not (DT CVs 11.02–19.27%; ICCs 0.93–0.97). This could be attributed to the age of the participants in the latter study. Nonetheless, it needs to be noted that only Martini et al. [12] used the GAITRite walkway as a method of measuring DT gait variables and, therefore, it is problematic to make generalisations to other methodological approaches.

5. Conclusions

However, whether certain technologies and/or variables are better suited in discriminating between concussed and non-concussed diagnoses is unknown.

Of particular interest to the authors was understanding the methodological approaches taken by various research groups and determining those variables that could consistently and reliably differentiate between concussed and non-concussed individuals. In terms of the first foci, MOCAP and force plates were the dominant technologies used to quantify concussed and non-concussed gait. From the literature reviewed, it would seem that none of the gait parameters assessed using MOCAP and force plates used to quantify concussed and non-concussed gait impairments were consistently sensitive enough to determine significant differences between groups, particularly over various time periods/testing occasions. This may mean two things: (1) DT walking is not sufficiently sensitive enough as an assessment to determine concussive diagnosis consistently; or (2) the protocols/technologies that are being used need refining or replacing to enable better concussion detection. For example, it would be interesting to determine if longer distances/large fields of capture enabled better precision of measurement.

With regards to the consistency and reliability of data, there seems to be little attention in the research reviewed on the variability of the measures utilised to quantify gait characteristics. Fundamental to research going forwards, especially with new and innovative technology, is establishing the reliability and smallest worthwhile changes in gait parameters.

Inertial sensor technology has been used in a few studies to date with some promising results around average gait speed and stride length. However, as with the other technologies reviewed, the reliability has not been documented and there may be better placement of sensors than the lumbar and dorsum but researchers have provided a starting point for ongoing investigation. For example, it would be interesting to determine if inertial sensors that quantify the foot–ground interaction (e.g., inner sole sensors) offer any diagnostic benefits in this area.

Finally, the cost of MOCAP and force plates and the expertise required to run, process and analyse the data is a restrictive factor for assessing concussions outside of conducting research. It is believed that the advent of technological “solutions” such as inertial sensors may enable dual task testing outside of the laboratory given the portability of such devices. If the technology is found to be valid, reliable, accurate and sensitive to changes in gait characteristics, they may provide a viable assessment option that could result in higher utility of dual task walking assessments in the diagnosis of concussion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.J.M. and J.C.; methodology, C.J.M. and J.C.; software, C.J.M.; validation, J.C. formal analysis, C.J.M. and J.C.; investigation, C.J.M.; resources, J.C.; data curation, C.J.M.; writing–original draft preparation, C.J.M.; writing–reviewing and editing, C.J.M. and J.C.; visualisation, C.J.M. and J.C.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material has not been presented previously. This research was funded by Movement Solutions NZ Limited.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study is openly available from the journals as listed in the reference section.

Acknowledgments

The review was not lodged with PROSPERO.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Herman, D.C.; Jones, D.; Harrison, A.; Moser, M.; Tillman, S.; Farmer, K.; Pass, A.; Clugston, J.; Hernandez, J.; Chmielewski, T. Concussion may increase the risk of subsequent lower extremity musculoskeletal injury in collegiate athletes. Sport. Med. 2017, 47, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.R.; Lynall, R.C.; Buckley, T.; Herman, D.C. Neuromuscular control deficits and the risk of subsequent injury after a concussion: A scoping review. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantu, R.C. Dysautoregulation/second-impact syndrome with recurrent athletic head injury. World Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantu, R.C.; Uretsky, M. Consequences of ignorance and arrogance for mismanagement of sports-related concussions: Short-term and long-term complications. In Concussions in Athletics: From Brain to Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Slobounov, S.M., Sebastianelli, W.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- McCrory, P.; Meeuwisse, W.; Dvořák, J.; Aubry, M.; Bailes, J.; Broglio, S.; Cantu, R.C.; Cassidy, D.; Echemendia, R.J.; Castellani, R.J.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport—The 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2017, 51, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Dual-task effect on gait balance control in adolescents with concussion. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Koester, M.C.; Chou, L.-S. The effect of cognitive task complexity on gait stability in adolescents following concussion. Exp. Brain Res. 2014, 232, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fino, P. A preliminary study of longitudinal differences in local dynamic stability between recently concussed and healthy athletes during single and dual-task gait. J. Biomech. 2016, 49, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Single-task and dual-task tandem gait test performance after concussion. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Kirkwood, M.W.; Provance, A.; Iverson, G.L.; Meehan, W.P. Using concurrent gait and cognitive assessments to identify impairments after concussion: A narrative review. Concussion 2018, 3, CNC54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.; Osternig, L.R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Gait stability following concussion. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2006, 38, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.N.; Sabin, M.J.; DePesa, S.A.; Leal, E.W.; Negrete, T.N.; Sosnoff, J.J.; Broglio, S.P. The chronic effects of concussion on gait. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossette, I.; Gagne, M.-E.; Ouellet, M.-C.; Fait, P.; Gagnon, I.; Sirois, K.; Blanchet, S.; Le Sage, N.; McFadyen, B.J. Executive dysfunction following a mild traumatic brain injury revealed in early adolescence with locomotor-cognitive dual-tasks. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1648–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catena, R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. The effects of attention capacity on dynamic balance control following concussion. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2011, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fait, P.; Swaine, B.; Cantin, J.-F.; Leblond, J.; McFadyen, B.J. Altered integrated locomotor and cognitive function in elite athletes 30 days postconcussion: A preliminary study. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2013, 28, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossette, I.; Ouellet, M.-C.; McFadyen, B.J. A preliminary study to identify locomotor-cognitive dual tasks that reveal persistent executive dysfunction after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 96, 1594–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Adolescents demonstrate greater gait balance control deficits after concussion than young adults. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2015, 43, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Monitoring recovery of gait balance control following concussion using an accelerometer. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 3364–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Return to activity after concussion affects dual-task gait balance control recovery. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2015, 47, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomito, M.J.; Kostyun, R.O.; Wu, Y.-H.; Mueske, N.M.; Wren, T.A.L.; Chou, L.-S.; Ounpuu, S. Motion analysis evaluation of adolescent athletes during dual-task walking following a concussion: A multicenter study. Gait Posture 2018, 64, 260–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.; Osternig, L.R.; Lee, H.-J.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. The effect of divided attention on gait stability following concussion. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catena, R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Altered balance control following concussion is better detected with an attention test during gait. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catena, R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Cognitive task effects on gait stability following concussion. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 176, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, T.; Osternig, L.R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Recovery of cognitive and dynamic motor function following concussion. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2007, 41, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, T.; Osternig, L.R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Balance control during gait in athletes and non-athletes following concussion. Med. Eng. Phys. 2008, 30, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catena, R.; Van Donkelaar, P.; Chou, L.-S. Different gait tasks distinguish immediate vs. long-term effects of concussion on balance control. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catena, R.; van Donkelaar, P.; Haltermann, C.I.; Chou, L.-S. Spatial orientation of attention and obstacle avoidance following concussion. Exp. Brain Res. 2009, 194, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Lu, T.-W.; Chou, L.-S. Effect of concussion on inter-joint coordination during divided-attention gait. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 2015, 35, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Stracciolini, A.; Geminiani, E.; Meehan, W.P. Dual-task gait differences in female and male adolescents following sport-related concussion. Gait Posture 2017, 54, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Oldham, J.R.; DiFabio, M.; Vallabhajousula, S.; Hall, E.E.; Ketcham, C.J.; Meehan, W.P.; Buckley, T. Single-task and dual-task gait among collegiate athletes of different sport classifications: Implications for concussion measurement. J. Appl. Biomech. 2017, 33, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Myer, G.D.; Grooms, D.; Diekfuss, J.; Yuan, W.; Meehan, W.P. Examining motor tasks of differing complexity after concussion in adolescents. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.; Buckley, T.; Berkstresser, B.; Wang, F.; Meehan, W.P. Identification of postconcussion dual-task gait abnormalities using normative reference values. J. Appl. Biomech. 2019, 35, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkner, J.; Meehan, W.P.; Master, C.L.; Howell, D.R. Gait and quiet-stance performance among adolescents after concussion-symptom resolution. J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, S.-L.; Osternig, L.R.; Chou, L.-S. Concussion induces gait inter-joint coordination variability under conditions of divided attention and obstacle crossing. Gait Posture 2013, 38, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Lugade, V.; Taksir, M.; Meehan, W.P. Determining the utility of a smartphone-based gait evaluation for possible use in concussion management. Phys. Sportsmed. 2020, 48, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.N.; Parrington, L.; Stuart, S.; Fino, P.C.; King, L.A. Gait performance in people with symptomatic, chronic mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasen, A.L.; Howell, D.R.; Chou, L.S.; Christie, A.D.; Pazzaglia, A.M. Cortical and physical function after mild traumatic brain injury. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2017, 49, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, D.N.; Goulet, G.C.; Gates, D.H.; Broglio, S.P. Long-term effects of adolescent concussion history on gait, across age. Gait Posture 2016, 49, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, D.R.; Stillman, A.; Buckley, T.; Berkstresser, B.; Wang, F.; Meehan, W.P. The utility of instrumented dual-task gait and tablet-based neurocognitive measurements after concussion. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, M.-E.; McFadyen, B.J.; Ouellet, M.-C. Performance during dual-task walking in a corridor after mild traumatic brain injury: A potential functional marker to assist return-to-function decisions. Brain Inj. 2021, 35, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Casas, A.; Hansen, K.T.; Bilski, P.; Gutmanis, I.; Wells, J.L.; Borrie, M.J. Quantitative gait analysis under dual-task in older people with mild cognitive impairment: A reliability study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, K.L.; Hill, K.D.; Lythgo, N.D.; Mashette, W. The reliability of spatiotemporal gait data for young and older women during continuous overground walking. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Hickey, A.; Lord, S.; Del Din, S.; Godfrey, A.; Rochester, L. Comprehensive measurement of stroke gait characteristics with a single accelerometer in the laboratory and community: A feasibility, validity and reliability study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.; Stuart, S.; McBarron, G.; Mancini, M.; Fino, P.C.; Curtze, C. Validity of mobility lab (version 2) for gait assessment in young adults, older adults and Parkinson’ disease. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).