Abstract

Parentification occurs when youth are forced to assume developmentally inappropriate parent- or adult-like roles and responsibilities. This review thoroughly examines current empirical research on parentification, its outcomes, and related mechanisms to outline patterns of findings and significant literature gaps. This review is timely in the large context of the COVID-19 pandemic, when pandemic-induced responsibilities and demands on youth, and the shifting family role may exacerbate parentification and its consequences. We used the 2020 updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework to identify 95 studies (13 qualitative, 81 quantitative, 1 mixed methods) meeting eligibility criteria. Representation from six continents highlights parentification as a global phenomenon. Using thematic analysis, we identified five themes from qualitative studies and five from quantitative studies. These were further integrated into four common themes: (1) some parentified youth experienced positive outcomes (e.g., positive coping), albeit constructs varied; (2) to mitigate additional trauma, youth employed various protective strategies; (3) common negative outcomes experienced by youth included internalizing behaviors, externalizing problems, and compromised physical health; and (4) youths’ characteristics (e.g., rejection sensitivity, attachment style), perceived benefits, and supports influenced parentification outcomes. Future methodological and substantive directions are discussed.

1. Introduction

Parentification—also known as adultification, spousification, child carers, or role reversal—occurs when youth are forced to assume developmentally inappropriate parent- or adult-like roles and responsibilities. Definitions highlight that parentification is distinct from supervised or monitored higher-order household responsibilities used by parents to promote positive youth development via leadership skills and character-building. Instead, parentified children and adolescents are expected to become pseudo-parents and pseudo-adults long before they are cognitively and physiologically equipped for these roles. Common roles children assume include household earner, self-carer, family-navigator, language and cultural broker, self-educator, counselor, confidant, caregiver, and emotional supporter (for parents and siblings) [1,2,3].

Floundering, resilient, and thriving outcome trajectories of parentified youth may vary depending on social determinants (e.g., social supports, resources) and perceptions (e.g., fairness, benefits) [4]. The implications of parentification expand beyond the parentified individual (e.g., psychological, cognitive, and physical health outcomes) to the family of origin (e.g., sibling outcomes) and intergenerational transmission [1] if parentified individuals have children (25–40% of parentified women report voluntary childlessness [5]).

The prevalence of parentification in the US is unknown. In 2006, Siskowski and colleagues [6] estimated 1.3–1.4 million parentified 8–18-year-olds (2.9% of the population) in the US, an underestimate according to Hooper and colleagues [3]. More recently, it is reported that 2–8% of youth under age 18 are young carers in high-income countries [7]. A recent study of Polish adolescents reported parentification prevalence estimates exceeding 30% during COVID-19 [8].

Now more than ever, understanding the impacts of parentification is a meaningful undertaking when considering the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 resulted in the sudden loss of multiple resources (e.g., childcare, schooling, employment) due to mandated closures, isolation, quarantine, distancing protocols, and the abrupt loss of family members and friends from illness and death. Since March 2020, when COVID-19 began to rapidly spread within the US, nearly 250,000 children lost a caregiver and households with children were more likely to experience financial hardships including the loss of jobs and health insurance [9]. Education was disrupted for over 1.6 billion children with a projected $17 trillion in life-long earning losses, globally [10]. In short, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated contributing factors (e.g., caregiver death; loss of job, income, and health insurance; disrupted education) to parentification.

This systematic review aimed to identify the predictive factors contributing to both positive and negative outcomes of parentification and is timely considering the circumstances forced upon the world by the COVID-19 pandemic. Before delving into the empirical findings, we provide a brief background of the dimensions, sources, and consequences of parentification.

1.1. Dimensions of Parentification

Classic models of parentification differentiate types of parentification based on the function it serves, typically as either instrumental or emotional parentification. Instrumental parentification involves youth assuming the responsibilities to maintain the household (e.g., meals, chores, finances). Emotional parentification requires youth to tend to the emotional needs of family members. This can include becoming a parents’ confidant (e.g., spousification), elevating siblings’ self-esteem, and even promoting harmony among the members. Some parentified youth may fulfill both the instrumental and emotional needs of the family.

Alternatively, researchers have also studied parentification by focusing on the various roles that can be assumed; specifically, parent-focused, sibling-focused, and spouse-focused parentification. The role-based approach emphasizes the role a child takes on, such as becoming a parent to care for their own parents (parent-focused) or siblings (sibling-focused), or even a spouse to their parents (spouse-focused). The function-based and role-based approaches to parentification are not mutually exclusive concepts, as parent-focused parentification could provide either/or possibly both emotional or instrumental functionality.

1.2. Sources of Parentification

Parentification typically results from the intentional or unintentional abdication of parenting responsibilities, child neglect, or child maltreatment by family-of-origin members, especially primary caregivers. The contributing factors of parentification tend to co-occur and there are countless reasons why parents cannot fulfill their role or why children are forced to assume these roles and responsibilities.

Common sources of youth role reversal and role overload include parental illness (e.g., HIV; opioid addiction), parental loss (e.g., death, divorce, incarceration), parental mental illness and physical disability, crises (e.g., displacement via eviction, war, unemployment), dysfunctional family dynamics (e.g., domestic partner violence), and migration (e.g., refugee, immigration). Additionally, parents who were themselves parentified may expect their children to do the same, creating a culture that is passed on for generations [11].

Although the level and degree of impact in the US are unknown, changing US demographics suggest increasing numbers of children are vulnerable to being parentified. In 2019, 26% of youth lived with only one biological parent and 4.0% lived with neither [12]. Parents who work long hours to meet their financial needs may come home with a diminished capacity to attend to household responsibilities and child needs due to fatigue. Living with single parents and parents who experience financial hardships may increase the risk of parentification of these children. With the increasing prevalence of obesity, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, and other chronic health conditions among adults and children, youth in the family without chronic conditions are at greater risk of becoming parentified, tending to the needs of their parents, siblings, or both.

1.3. Consequences of Parentification

As articulated in Minuchin’s family system theory [13], a hierarchy of power exists among the family subsystems, and clear hierarchical boundaries between parents and children are considered to be critical to children’s positive development. The dissolution in or the alteration of the family structural boundaries, as may occur when children are parentified and essentially become the parents, breadwinners, and other roles with power in the family, has important implications for children’s behavioral and moral development. Thus, parentification may be linked to adverse behavioral or life outcomes. Parentification is considered particularly harmful when youth are forced to take on tasks beyond their developmental abilities and when they do not receive adequate support [11,14]. Consistent with this proposition, previous research showed that parentified children experience suboptimal outcomes in adulthood, including higher incidence of depression, anxiety, drug use and addiction, under- and un-employment, poor physical health, and lower educational attainment [15,16,17].

In contrast, it has also been argued in early theoretical work that parentification is not necessarily pathological [18]. When youth assume parental roles of moderate intensity in a time-limited manner and their contributions are appreciated, the parentification experience may instead be adaptive [11]. Parentification could beneficially influence youth development because it provides youth with opportunities to master socialization and coping skills, and be self-reliant, which contribute to healthy identity formation and improved self-esteem. In support of this, early parentification among children of parents with HIV/AIDS were found to have better adaptive coping skills 6 years later [19]. Similarly, parentification was linked to less risky sex among high-risk adolescent girls [20] and with resilience in general [17], although the association may be attributable to other factors such as socioeconomic background.

1.4. Purpose of Current Review

This review provides a thorough examination of current empirical research on parentification, its positive and negative developmental consequences, the heterogeneity of parentification impacts, and related mechanisms. Through the examination of the empirical research, we then outline significant literature gaps and provide future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was guided by the 2020 updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [21,22].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria—Inclusion and Exclusion

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) empirical study including quantitative and/or qualitative primary or secondary data analysis; (2) peer-reviewed publication; (3) include at least one developmental or outcome variable (e.g., mental or physical wellbeing, stress coping, leadership skills, substance use, sexual risk-taking, educational attainment, workforce engagement); (4) written or translated into English; and (5) full text available. Studies could include a wide range of designs and types of data including retrospective, prospective, qualitative, quantitative, experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental studies. Studies were excluded if they were (1) theoretical or review articles with no primary or secondary data; (2) not peer-reviewed (book chapters, reports, theses/dissertations, conference proceedings); and (3) exclusively descriptive of parentification types, prevalence, or incidence with no outcomes reported. If a study did not clearly meet inclusion criteria, two or three authors discussed the study until consensus was reached.

For synthesis, studies were grouped in two ways. First, they were stratified by quantitative versus qualitative and mixed. Then, strata were grouped by study focus: outcomes only (positive, negative, both); outcomes and mechanisms (mediators/moderators).

2.2. Information Sources

To ensure a comprehensive literature search, three databases were searched on 21 August 2021, for relevant articles: PsycInfo, Academic Search Complete, and Web of Science. American Psychological Association PsycInfo is a database of abstracts and articles related to psychological, social, and behavioral science. Academic Search Complete (EBSCO Publishing) is a scholarly database spanning numerous disciplines and includes both open-access and non-open-access peer-reviewed and grey literature (e.g., books, reports). Web of Science database indexes scholarly products (e.g., articles from over 12,000 journals, 148,000 conference presentations) from physical and social sciences, humanities, and arts.

2.3. Search Strategy

For each database, articles available from the inception date until July 2021 were included. MESH and Boolean search terms were used to generate relevant articles. Parentification is known by other related terms, including spousification, adultification, and role reversal. Therefore, these and their related terms (denoted by *) were searched. Further, the search was contingent (using AND) on outcome-related terms (e.g., outcome, resilience, thriving, effect) to answer the research question. Article search results (record data including title, authors, publication date, journal name, and abstract) for resultant articles were exported to Excel and imported into SPSS to remove duplicates. Table 1 summarized search terms by database and the number of resultant articles by the database.

Table 1.

Search Algorithms and Articles Generated by Database.

2.4. Selection and Data Collection Processes

This dataset was divided across three authors (JKD, FRC, and MKN) for the initial review of titles and abstracts for eligibility. Ambiguous articles were cross-checked by a different reviewer. For a few unclear articles, the three authors (JKD, FRC, and MKN) discussed the article until a consensus was reached about inclusion or exclusion status. Then, the resulting list of articles was divided in half for a full article review and data abstraction (Round 1). Two of the authors (MKN, AMC) independently abstracted descriptive data from articles (participants, study design, data type, parentification measures used, main findings, category of study) and flagged ambiguous articles for review by the first two authors and noted articles that did not meet eligibility criteria. Next, half of the assigned articles were cross-validated by a different reviewer for verification of abstracted data and relevance. Then, the list of articles for each reviewer was stratified by quantitative or qualitative type and randomly divided into Tiers 1, 2, and 3.

The team met to discuss additional data fields to abstract including specific outcomes, positive or negative relationship direction, significance, and future directions. Then, two reviewers read assigned Tier 1 articles, updated existing fields, and abstracted data for new fields (Round 2). These results were reviewed by the first two authors and the full team met to discuss the process of data abstraction. Then, the reviewers (MKN and AMC) continued abstracting data for Tier 2 and Tier 3 articles and flagged any challenging articles for JKD and FRC to review. In Round 3, cited studies discovered through article review that met the inclusion criteria were also included and data were abstracted. Every article was reviewed independently by at least two reviewers.

2.5. Data Items

Data items extracted for eligible articles are listed and defined in Table 2. Most data items are standard and are discussed below. Both positive and negative outcomes were included. This scoping review intentionally optimized study inclusion by broadly defining relevant outcomes and not placing temporal restrictions on outcomes (e.g., early childhood, adolescence, adulthood). The exposure variable of interest was parentification and no temporal restrictions were placed on when this experience occurred.

Table 2.

Data Item List, Definition, and Format.

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

Every article was reviewed independently by at least two reviewers. Studies were cross-verified for relevance by at least one additional independent coder. If questions persisted, a third independent coder reviewed the article, and a fourth reviewer was engaged only in ambiguous cases for which their content expertise was needed. As needed, discussions were conducted until a consensus for inclusion was reached.

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [23] facilitated study risk of bias, rigor, and quality assessment. Authors independently assessed each article on five components relevant to the article type (e.g., qualitative, quantitative descriptive) with “yes”, “no”, and “can’t tell” designations. The tool was adapted to include partial credit for some criteria, including screening items that required a specified research question to receive a “yes” designation. If articles included a purpose, aim, or objective statement, they were further reviewed. Further, subcriteria were created for double-barreled or complex criteria. For example, five subcriteria criteria—inclusion, exclusion, response rate mentioned, and sampling strategies detailed—were used to assess whether a study represented the target population for quantitative studies. Partial credit was given, and overall quality ratings were adjusted to no, low, moderate, or high. At least 10% of articles were cross-validated by a second independent reviewer. Interrater questions about meeting criteria and sub-criteria were noted. Discrepancies between reviewers (~5%) were discussed as a team and resolved.

2.7. Synthesis Methods

For study characteristics and parentification and outcome measures results, patterns of findings were quantified by count. For substantive findings, we utilized the six steps of thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke [24]. The first three steps—data familiarity, initial coding, theme generation—were undertaken by independent reviewers separately for qualitative studies and quantitative studies. The second three steps—theme review, theme definition and naming, and report development—involved coders across both study types. Additional details for the six steps are as follows. Data familiarity involved reading each study. Independent reviewers initially coded studies using inductive open-coding (identifying major and subcodes and definitions). Themes were generated based on shared or associated codes. Themes were reviewed by the coders and then by the larger team. Once themes were agreed upon, definitions and names were drafted and them finalized. Last, these were written up for the manuscript. Objectivity was promoted via multiple approaches. First, each study was read, coded, and themed by independent reviewers. Summaries of themes were written by reviewers leading each article. Second, themes were generated for qualitative articles and quantitative articles separately followed by integration analyses conducted for the two study types. Last, these themes were reviewed by other team members before team discussions that centered on description meaning and wording, theme consistency and inconsistency by study types, integration of themes across studies, and consensus of final themes to include in the report.

2.8. Certainty Assessment

For quantitative studies, MMAT includes criteria related to the use of confounders. For mixed methods studies, one criterion assesses whether study components adhere to quality standards of quantitative and qualitative traditions. For quantitative studies, the criterion was assessed using four sub-criteria: any confounders included, relevant demographic characteristics used, other (non-demographic) confounders (e.g., pre-exposure outcome levels; the age of parentification onset), and use of sophisticated statistics to model potential confounders.

3. Results

The result section is organized into several parts. First, the study selection and characteristics are described (Table 3). Second, measurement patterns regarding parentification (Table 4) and outcomes (Table 5) are shown. Third, study findings are presented as themes by design and analytic approaches (quantitative followed by qualitative and mixed). Last, theme patterns are synthesized across the study design.

3.1. Included Study Description

3.1.1. Study Selection

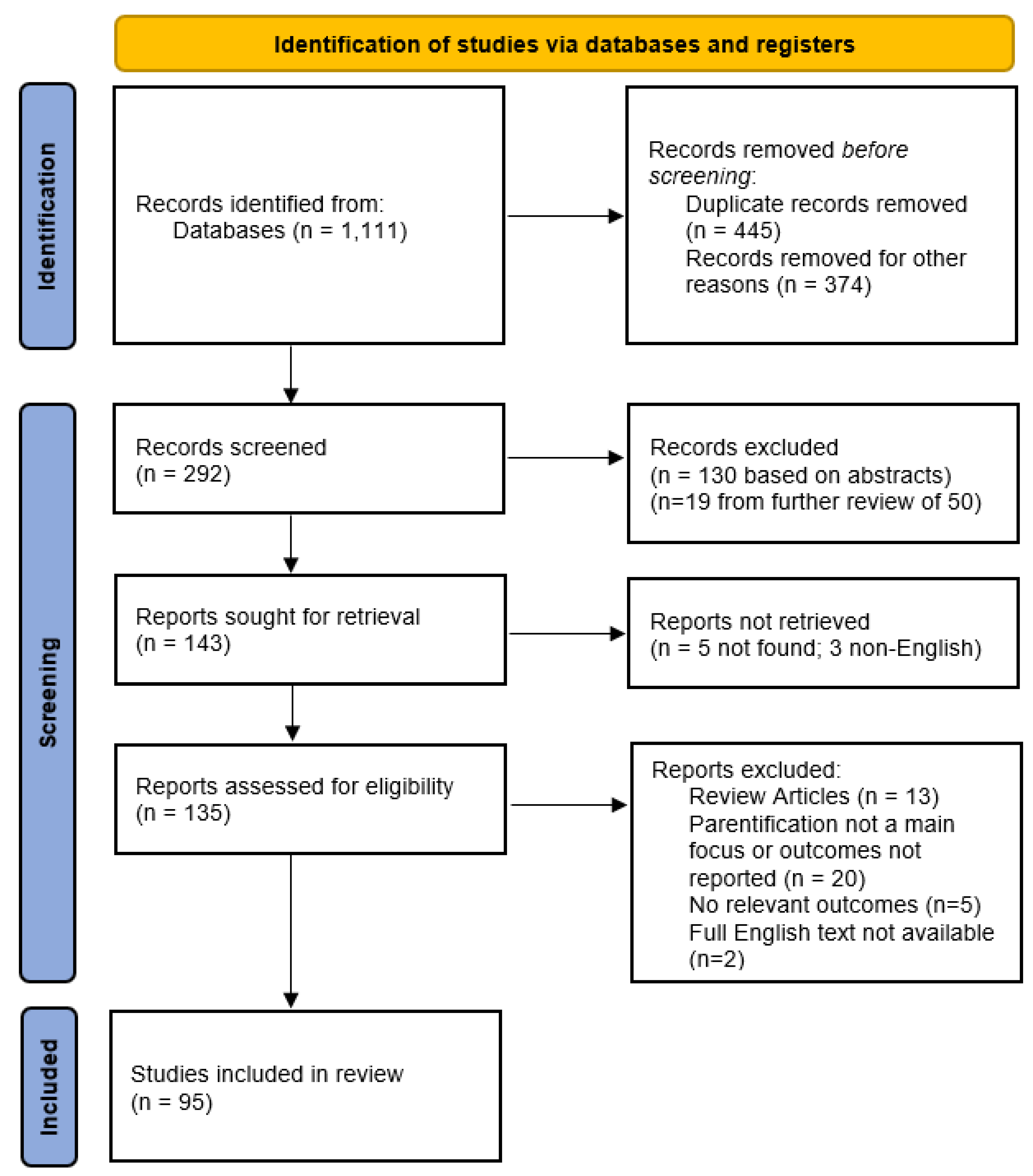

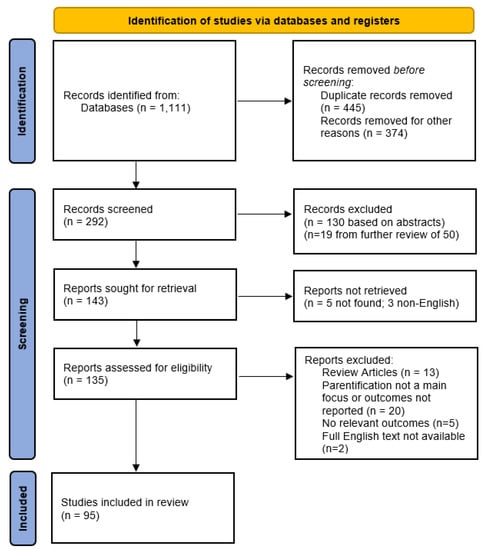

A total of 1111 articles were retrieved across three databases (227 from PsycInfo; 313 from Academic Search Complete; 571 from Web of Science). Of these, 445 were duplicates and 374 were removed for other reasons (e.g., review articles, no outcomes included, no mention of parentification or related terms or constructs). The manual screening was performed on 292 abstracts and 149 were excluded for not meeting inclusion or meeting exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 143 articles, 135 could be retrieved for eligibility assessment, 40 of which were excluded. The 40 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria of our review; specifically, these articles were review articles (n = 13), did not include exposure (i.e., at least some participants reporting parentification experiences) or outcome variables (n = 21), reported irrelevant outcomes (n = 4), or summaries in English but the English full-text article could not be located (n = 2). This review focuses on 95 articles successfully screened and meeting all eligibility criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram outlining inclusion and exclusion processes is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Article Search, Screening, Exclusion, and Inclusion.

3.1.2. Study Characteristics

Table 3 shows study characteristics for one mixed-methods [25], 13 qualitative [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38], and 81 quantitative [3,8,17,19,20,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114] studies included in this review (n = 95; ordered alphabetically within study type). Four papers were published before 2000, 20 between 2000 and 2010, 57 between 2011 and 2019, and 14 after 2020. A total of 55 studies (58%) were conducted in the United States, 19 in Europe (20%), eight in the Middle East (8%), seven in Asia (7%), five in Canada (5%), and one in Africa (1%). All studies used non-random sampling methods to recruit participants.

Studies varied greatly in sample size (quantitative study range: 41–1796; qualitative study range: 2–34; mixed: 128). Among the quantitative (including one mixed-methods) studies, 17 had fewer than 100 participants, 24 had between 100 and 199, 14 had between 200 and 299, and 24 had 300 or more participants. Among the qualitative studies, six had fewer than ten participants and seven had ten or more participants. Forty-five studies included adults, 27 studies included adolescents, and 20 studies included children. Participants’ ages varied across studies, ranging from 19 to 67 among adults, 11 to 21 among adolescents, and three months old to 17 years old among children. Two studies did not explicitly specify the age of the participants. Forty-six studies (48%) sampled school-aged populations (6–18 years old), and 34 studies (35%) focused on college-students, suggesting the use of convenience samples and potential selection effects (e.g., higher income; higher education). Most studies (45%) focused on adult retrospective accounts of parentification experiences. Furthermore, most participants in the studies were female. The overrepresentation of females presents a research gap in understanding parentification among males.

Twenty-six studies included parent-child dyads or triads, 19 of which were mother-child dyads. This disproportionate focus on mother-child dyads reveals a gap within the literature exploring fathers’ and sons’ perspectives on parentification. Six studies (6%) included populations of children with HIV/AIDS-infected mothers. Five studies (5%) included populations of typically developing (TD) siblings who reported having a sibling with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Five studies (5%) included immigrant and refugee populations. Two studies included clinical populations or cases.

Table 3.

General Characteristics of Studies.

Table 3.

General Characteristics of Studies.

| Author(s) | Year | Sample Size | Participants | Participants’ Age^ | Participants’ Sex (Female) | Sample Context | Country | Study Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayseless et al. [25] | 2004 | 128 quan; 16 qual | Adults | 37.4 (SD = 12.6) | 53.13% | Community sample | Canada | Mixed |

| Callaghan et al. [26] | 2016 | 2 sibling dyads | Children | range: 7–11 | 25% | Families affected by domestic violence; case studies drawn from the larger interviews | UK | Qual |

| Chademana, and van Wyk [27] | 2021 | 7 | Children | 17.57 (range: 14–20) | 14.29% | Selected based on survey findings; orphans living in child- and youth-headed households in Zimbabwe | Zimbabwe | Qual |

| Chee et al. [28] | 2014 | 5 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 40 (range: 28–54, mothers); 10.4 (range: 7–12, children) | not specified | Low-income families | Singapore | Qual |

| Collado [29] | 2021 | 10 | Young adults | range: 19–23 | 60% | Convenience sampling; young adult children among internally displaced, refugee families due to political conflict | Philippines | Qual |

| Gelman and Rhames [30] | 2018 | 4 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 47.5 (range: 43–51, mothers); 18 (range: 15–20, children) | 62.50% (children) | Children living at home with a parent with younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia | US | Qual |

| Kabat [31] | 1996 | 2 (mother-daughter dyads) | Adults | 18 and 23 (daughters) | 100% | Clinical case studies | US | Qual |

| Keigher et al. [32] | 2005 | 7 | Mothers | 42 (range: 39–45) | 100% | Mothers with HIV | US | Qual |

| Kosner et al. [33] | 2014 | 34 | Adolescents, young adults | 16 (range: 15–18, adolescents); 25.70 (range: 23–31, young adults) | 64.71% | Young immigrants to Israel from the former Soviet Union during adolescence; adolescents’ current experiences and Young adults’ retrospective accounts | Israel | Qual |

| Petrowski and Stein [34] | 2016 | 10 | Adults | 20.1 (SD = 1.37) | 100% | College students; women with mothers diagnosed with a long-term mental illness | US | Qual |

| Rizkalla et al. [35] | 2020 | 23 | Mothers | 37.62 (SD = 8.93) | 100% | Syrian refugee families, mothers’ accounts | US | Qual |

| Saha [36] | 2016 | 30 | Adolescents | range: 11–18 | not specified | High school students; middle socioeconomic status; first-born child with siblings | India | Qual |

| Tahkola et al. [37] | 2020 | 18 | Young adults | 25.4 (range: 18–32) | 77.78% | Finnish young adults with foster care background | Finland | Qual |

| Tedgård et al. [38] | 2019 | 19 | Adults | range: 21–40 (mothers), range: 27–40 (fathers) | 68.42% | Parent of children between 1 and 5 years old; parents grew up with drug-abusing parents | Sweden | Qual |

| Abraham and Stein [39] | 2013 | 116 | Adults | 19.79 (SD = 2.34) | 81% | Emerging adults who have a mother with/without mental illness and poor psychological adjustment | US | Quan |

| Arellano et al. [40] | 2018 | 1796 | Adults | 21.23 (SD = 5.25) | 79.99% | College students | US | Quan |

| Baggett et al. [41] | 2015 | 1632 | Adults | 19.29 (SD = 1.36) | 100% | College students | US | Quan |

| Beffel and Nuttall [42] | 2020 | 108 | Adults | 20.37 (SD = 1.55) | 69.44% | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | US | Quan |

| Borchet and Lewandowska-Walter [43] | 2017 | 264 | Late adolescents | 21.39 (SD = 2.52) | 87.50% | Individuals | Poland | Quan |

| Borchet et al. [46] | 2016 | 89 family triads (31 mothers, 27 fathers, 31 late adolescents) | Triads of father, mother and late adolescents | 49.58 (SD = 5.14, mothers); 51.04 (SD = 5.32, fathers); 22.58 (SD = 1.52, late adolescents) | 53.45% (parents), 64.52% (adolescents) | Family triads; families recruited through students | Poland | Quan |

| Borchet et al. [8] | 2021 | 191 | Adolescents | 14.61 (SD = 1.26) | 55% | High school students | Poland | Quan |

| Borchet, Lewandowska-Walter, Polomski, and Peplinska [44] | 2020 | 641 | Adolescents | 14.96 (SD = 0.36) | 60.70% | College students | Poland | Quan |

| Borchet, Lewandowska-Walter, Polomski, Peplinska, and Hooper [45] | 2020 | 218 | Late adolescents | 21.37 (SD = 2.49) | 86.20% | Majority self-identified college students | Poland | Quan |

| Boumans & Dorant [47] | 2018 | 297 | Adults | 18.9 (SD = 1.64) | 82.87% | College students; carers/non-carers | Netherlands | Quan |

| Burton et al. [48] | 2018 | 314 | Adolescents | range: 12–13 (63.7%) | 50.60% | Middle and high school students | US | Quan |

| Carroll & Robinson [49] | 2000 | 207 | Adults | range: 18–25 (72%) | 87.92% | College students; have/do not have alcoholic and/or workaholic parents | US | Quan |

| Castro et al. [50] | 2004 | 213 | Adults | 31 (range: 20–59) | 85% | College students in clinical and counseling psychology graduate programs | US | Quan |

| Champion et al. [51] | 2009 | 72 (mother-adolescent dyads; 34 with depression & 38 without depression) | Mothers, adolescents | 41.7 (SD = 5.13, mothers); 12.2 (SD = 1.07, adolescents) | 50% (adolescents) | Mother with/without history of depression from urban area | US | Quan |

| Chen and Panebianco [52] | 2020 | 132 | Adolescents | 14.38 (SD = 2.03) | 39.39% | Middle and high school students with at least one parent with a chronic illness | US | Quan |

| Chen et al. [53] | 2018 | 83 | Adults | 21.37 (SD = 1.87) | 60% | Transitional-aged youth | US | Quan |

| Cho and Lee [54] | 2019 | 316 | Adults | 21.86 (range: 18–29) | 66.10% | College students | Korea | Quan |

| Cimsir and Akdogan [55] | 2021 | 147 | Adults | 20.20 (SD = 1.12) | 74.10% | College students | Turkey | Quan |

| Dragan and Hardt [56] | 2016 | 508 (Poland), 500 (Germany) | Adults | 38.7 (SD = 14.4, Poland); 44.8 (SD = 16.1, Germany) | 56.3% (Poland), 50.0% (Germany) | Subjects all registered with a market research company | Poland, Germany | Quan |

| Duval et al. [57] | 2018 | 263 | Adolescents | 17.08 (SD = 4.45) | 78% | High school and college students | Canada | Quan |

| Fitzgerald et al. [58] | 2008 | 499 | Adults | 19.29 (SD = 1.95) | 100% | College students | US | Quan |

| Fortin, A., et al. [59] | 2011 | 79 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 37.72 (SD = 5.78, mothers); 10.26 (SD = 1.27, children) | 48.10% (children) | Children exposed to domestic violence | Canada | Quan |

| Godsall et al. [60] | 2004 | 416 | Children | 14.09 (SD = 1.68) | 45.20% | High-functioning/low-functioning children; students | US | Quan |

| Golan and Goldner [61] | 2019 | 80 | Adults | 33.47 (SD = 4.76) | 100% | Young, first-time Jewish mothers of children aged 12–36 months | Israel | Quan |

| Goldner et al. [62] | 2017 | 351 | Adolescents | 14.00 (SD = 0.69) | 53% | Middle school students | Israel | Quan |

| Goldner et al. [63] | 2019 | 334 | Adolescents | 13.95 (SD = 0.69) | 55% | Convenience sample; drawn from mid- to high-SES middle schools | Israel | Quan |

| Hoffman and Shrira [64] | 2019 | 341 (parent-adult dyads) | Adults | 80.05 (SD = 6.10, parents); 53.50 (SD = 5.57, children) | 65.4% (parents), 64.2% (adult offspring) | Community sample; Jewish parents of European origin born before 1945 and their offspring born after 1945; parents were alive during World War II and either Holocaust survivors or had no Holocaust background | Israel | Quan |

| Hooper, Doehler et al. [65] | 2012 | 51 (parent-adolescent dyads) | Parents, adolescents | 41.74 (SD = 6.64, parents); 13.80 (SD = 1.28, adolescent) | 92% (parents), 51% (children) | Rural community sample | US | Quan |

| Hooper et al. [17] | 2008 | 156 | Adults | 22.45 (SD = 6.04) | 69.20% | College students | US | Quan |

| Hooper et al. [66] | 2015 | 977 | Adults | 21.39 (SD = 5.84) | 81% | College students | US | Quan |

| Hooper, Wallace et al. [3] | 2012 | 314 | Adults | 22.57 (SD = 6.19, Black); 20.37 (SD = 1.91, White) | 56.05% | College students | US | Quan |

| Jankowski and Hooper [67] | 2014 | 565 | Adults | 20.78 (SD = 3.79) | 81.20% | College students | US | Quan |

| Jankowski et al. [68] | 2013 | 783 | Adults | 20.92 (SD = 3.73) | 76.40% | College students | US | Quan |

| Katz et al. [69] | 2009 | 163 | Adults | >18 (not specified) | 100% | College students; grew up in an intact family with one mother and one father | US | Quan |

| Khafi et al. [70] | 2014 | 143 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 10.17 (SD = 1.59, children, T1); 14.89 (SD = 1.60, children, T2) | 52.40% (children) | Sample overrepresents mothers with anxiety, affective, and/or substance use disorders; predominantly low-income | US | Quan |

| King and Mallinckrodt [71] | 2000 | 65 | Adults | 22.41 (SD = 3.21, clinical); 21.53 (SD = 1.64, nonclinical) | 85% (clinical), 69% (nonclinical) | College students; clinical/nonclinical samples | US | Quan |

| Lester et al. [72] | 2010 | 264 (mother- adolescent dyads) | Mothers, adolescent | 40.6 (SD = 5.78, mothers); 15.6 (SD = 2.4, adolescent) | 58% (adolescent) | Adolescent with HIV/AIDS-infected mothers, or adolescent of neighborhood control mothers | US | Quan |

| Macfie et al. [74] | 2008 | 138 families | Families (mothers, fathers, children) | 27 (range: 18–35, mothers); prenatally, 3 mos., 12 mos., 24 mos., 60 mos., 70 mos. (children) | 54.35% (children) | First-time parents | US | Quan |

| Macfie et al. [73] | 2005 | 57 | Families (mothers, fathers, adolescents) | 27 mos. (children, Wave 1); 70 mos. (children, Wave 2); 26 (mothers); 28 (fathers) | 52.63% (children) | Rural families; waves of data collected on families at 27 months and 70 months from the child’s birth. | US | Quan |

| Madden and Shaffer [75] | 2016 | 52 | Adults | 19.49 (SD = 1.39) | 80.70% | College students | US | Quan |

| McGauran et al. [76] | 2019 | 137 | Adults | 36.90 (SD = 13.91, offender from probation service); 31.83 (SD = 13.25, non-offender) | 8% (offender), 69% (non-offender) | Offender/non-offender samples; all white | UK | Quan |

| McMahon and Luthar [77] | 2007 | 356 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 38.23 (SD = 6.20, mothers); 12.09 (SD = 2.80, children) | 54% (children) | Urban, low-income children living with biological mothers; includes mothers (a) with drug problem, (b) with psychiatric problem, or (c) none of the two | US | Quan |

| Murrin et al. [78] | 2021 | 108 | Adults | 20.37 (SD = 1.55) | 69.44% | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | US | Quan |

| Nebbitt and Lombe [79] | 2010 | 238 | Adolescents | 15.62 (SD = 2.08) | 47.48% | African Americans living in urban, public housing developments | US | Quan |

| Nuttall et al. [82] | 2012 | 374 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 21.47 (SD = 5.32, mothers); prenatally, 12 mos., 36 mos. (children) | 49% (children) | Community sample; high-risk, first-time adolescent and adult mothers | US | Quan |

| Nuttall, Ballinger et al. [80] | 2021 | 374 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 21.47 (SD = 5.32, mothers); 36 mos. (children) | 49% (children) | Majority of mother sample were non-White (78.4%) and unmarried (74%) | US | Quan |

| Nuttall et al. [81] | 2018 | 108 | Adults | 20.37 (SD = 1.55) | 69.44% | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | US | Quan |

| Nuttall et al. [84] | 2019 | 110 mother-child dyads | Mothers, children | 30.76 (SD = 7.04) | 55% | Predominantly low-income and ethnic minorities; college students; psychosis-proneness sample | US | Quan |

| Nuttall, Valentino, et al. [83] | 2021 | 235 family triads | Families (mothers, fathers, children) | 35.02 (SD = 5.60, mothers, Wave 1); 36.84 (SD = 6.15, fathers, Wave 1); 6.00 (SD = 0.48, children, Wave 1) | 45% (children) | Data collected when children were in kindergarten (Wave 1), first grade (Wave 2), and second grade (Wave 3) | US | Quan |

| Oznobishin and Kurman [85] | 2009 | 184 (Study 1), 180 (Study 2) | Adults, adolescents | 23.73 (SD = 2.23, Study 1); 16.73 (SD = 0.94, Study 2) | 60.87% (Study 1), 57.78% (Study 2) | College students (Study 1) and high school students (Study 2); both studies include immigrant or Israeli-born | Israel | Quan |

| Peris et al. [86] | 2008 | 83 family triads | Families (mothers, fathers, adolescents) | 15.26 (range: 14–18, adolescents) | 48% (children) | Family triads, longitudinal design | US | Quan |

| Perrin et al. [87] | 2013 | 120 | Adults | 19.4 (SD = 1.52) | 57.67% | College students | Canada | Quan |

| Prussien et al. [88] | 2018 | 78 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 38.68 (SD = 7.52, mothers); 10.35 (SD = 3.67, children) | 45% (children) | Mothers with children diagnosed with cancer | US | Quan |

| Rodriguez and Margolin [89] | 2018 | 80 (mother-adolescent dyads) | Mothers, adolescents | 16 (SD = 1.2) | 53.75% (children) | Adolescents in active-duty military families | US | Quan |

| Rogers and Lowrie [90] | 2016 | 226 | Adults | 39.0 (SD = 16.3) | 50.90% | Age ranged from 19 to 92 years old; 82.4% Caucasian | UK | Quan |

| Sang et al. [20] | 2014 | 176 (mother-daughter dyads) | Mothers, daughters | 40.89 (SD = 7.13, mothers); 15.8 (SD = 1.55, daughters) | 100% | African American and Hispanic mother; HIV-negative daughter; low-income inner-city, recruited in agencies that provided services to HIV-infected women; victims of intimate partner violence, and those in substance use recovery | US | Quan |

| Schier et al. [91] | 2015 | 500 (extraction), 500 (cross-validation) | Adults | 44.8 (SD = 16.1; extraction), 39.3 (SD = 11.2; cross-validation) | 50% (extraction), 55% (cross-validation) | Internet survey; extraction and cross-validation samples | Germany | Quan |

| Shaffer and Egeland [92] | 2011 | 196 (mother-offspring dyads) | Mothers, offsprings | Longitudinal: offspring followed from 24 mos initially to adolescent years (age 13, 16, 17.5 years) | 42.85% (offspring) | Mother of low socioeconomic status recruited through a public health clinic for prenatal care | US | Quan |

| Sheinbaum et al. [93] | 2015 | 214 | Adults | 21.4 (SD = 2.4) | 78% | College students | Spain | Quan |

| Shin and Hecht [94] | 2012 | 697, 605, and 526 across Waves 4, 5, 6 | Adolescents | 12.31 (SD = 0.58) | 53% | Mexican-heritage; middle school students; use Wave 4–6 only | US | Quan |

| Stein et al. [95] | 1999 | 183 (parent-adolescent dyads) | Parents, adolescents | 37.67 (SD = 5.64, parents); 14.75 (SD = 2.07, children) | 80% (parents), 54% (adolescent) | Non-infected adolescents of parents with AIDS | US | Quan |

| Stein et al. [19] | 2007 | 213 | Adolescents | 14.9 (range: 11–19) | 56% | Children with HIV/AIDS-infected mothers | US | Quan |

| Sullivan et al. [96] | 2018 | 1441 | Adolescents | grades 7, 9, and 11 (proxy for age) | 50.87% | Middle and high school students | US | Quan |

| Telzer and Fuligni [97] | 2009 | 752 | Adolescents | 14.88 (SD = 0.39) | not provided | High school students; ethnically diverse sample of adolescents from predominantly Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds | US | Quan |

| Titzmann [98] | 2012 | 382 (mother-adolescent dyads) | Mothers, adolescent | 15.2 (SD = 2.55, adolescent) | 56.54% (children) | Ethnic (185) and 197 native German families | Germany | Quan |

| Titzmann and Gniewosz [99] | 2018 | 185 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 15.7 (SD = 2.7, children) | 60.4% (children) | Ethnic German immigrant mother-adolescent dyads from the former Soviet Union | Germany | Quan |

| Tomeny et al. [101] | 2017a | 60 | Adults | 29.65 (SD = 13.17) | 85% | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | US | Quan |

| Tomeny et al. [100] | 2017b | 41 | Adults | 25.83 (SD = 5.36) | 80% | Typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | US | Quan |

| Tompkins [102] | 2007 | 43 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 12.8 (range: 9–16, children) | not specified | Children with HIV/AIDS-infected mother (23) vs. children with HIV-seronegative mother (20). | US | Quan |

| van der Mijl and Vingerhoet [103] | 2017 | 265 | Adults | 20.2 (SD = 3.1) | 73% | College students | Netherlands | Quan |

| Van Loon et al. [104] | 2017 | 118 | Adolescents | 13.47 (SD = 1.40) | 50.80% | Adolescents living with a parent with mental health problems | Netherlands | Quan |

| Walsh et al. [105] | 2006 | 140 (Study 1), 123 (Study 2) | Adolescents | 16.8 (SD = 5.60, Study 1); 16.96 (SD = 1.39, Study 2) | 45.7% (Study 1), 47% (Study 2) | Study 1: Immigrants from former Soviet Union in Israel vs. Israel born; Study 2: Immigrants from former Soviet Union in Israel | Israel | Quan |

| Wang et al. [106] | 2017 | 1073 | Children | range: 9–17.7 (grades 3–12) | 51.80% | Two elementary school and three high school students | China | Quan |

| Wei et al. [114] | 2020 | 1648 | Adolescents | Junior and senior high students (age not specified) | 46.30% | Junior and senior high school students | Taiwan | Quan |

| Wells and Jones [108] | 1998 | 124 | Adults | 21 (range: 17–48) | 65% | College students | US | Quan |

| Wells and Jones [109] | 2000 | 197 | Adults | 21 (range: 17–38) | 65% | College students | US | Quan |

| Wells et al. [107] | 1999 | 200 | Adults | 21 (range: 17–48) | 65% | College students | US | Quan |

| Williams and Francis [110] | 2010 | 99 | Adults | 23.76 (SD = 5.55) | 84% | College students | Canada | Quan |

| Woolgar and Murray [111] | 2010 | 94 (55 depressed and 39 nondepressed mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 60.3 mos. (SD = 0.84, index); 60.5 mos. (SD = 0.94, control) | 46% (index children), 53% (control children) | Community sample; children and mothers with/without postnatal depression; index and control groups | UK | Quan |

| Yew et al. [112] | 2017 | 419 | Adults | 21.9 (SD = 2.04) | 62.80% | College students in clinical and nonclinical academic programs | Malaysia | Quan |

| Zvara et al. [113] | 2018 | 557 (mother-child dyads) | Mothers, children | 25.6 (SD = 6.1, mothers); 7.7 (SD = 1.5, children) | 49.6% (children) | Rural, low-income families | US | Quan |

^ For participant age, range is reported if mean and standard deviation are not provided. Notes: Qual = qualitative; Quan = quantitative; Mixed = mixed methods. Lester, P., et al., 2010 [72]: Participants are characterized as adolescents in this review despite that they were referred to as children in the original publication. The reason is that the youth were aged 13 to 19 years; Cimsir, E. and Akdogan, R., 2021 [55]: It contains 5 studies; only Study 5 characteristics are reported here because the first 4 studies are all about development of the emotional incest scale and its validation.

3.2. Risk of Bias and Certainty Assessment

As noted above, MMAT criteria ratings were used to assess study risk of bias, rigor, and quality. For the 13 qualitative studies and one mixed methods study (which reported primarily qualitative data), approximately 86% explicitly described appropriate research questions or objectives, data collection methods, findings, and interpretation, whereas the remaining 14% provided some description or narrative to substantively meet the criteria. Nearly 86% had medium to high coherence between data, analysis, and interpretation for at least one study aim or objective. Given these high MMAT criteria ratings, it was concluded that the risk of bias was low, and the study quality was high for the qualitative/mixed studies included in this review. Across the 81 quantitative articles, about 67% used appropriate measures for intervention/exposure and outcomes, nearly 73% specified at least one inclusion or exclusion criteria related to the target population, and 65% met at least one of the criteria for analyses that accounted for confounders. The authors relied on substantive comments rather than calculated scores, as encouraged by tool developers. We conclude that our review reflects a minimum risk of bias as it comprehensively incorporates the study literature.

3.3. Measurement Pattern Synthesis

3.3.1. Parentification Measures

Original measure names and descriptions as well as study-specific modifications and psychometric properties are presented in Table 4 for 11 unique measures used by two or more studies (10 measures were only used by one study; not shown). Measures are organized by frequency of use (alphabetically for tied measures) and studies within a measure are alphabetically ordered by first author’s last name. Studies using more than one measure appear more than once in Table 4. Reliabilities were generally acceptable (α: 0.70 to 0.95) with a few exceptions. Of the 78 total entries across 21 measures, 53 (67.9%) made modifications to the original measures. Common modifications to original measures included using select subscales, reducing the number of items, or adopting peer-reviewed translations. Languages in which measures have been administered include Dutch, English, French, German, Hebrew, Polish, and Russian.

The most frequently used measure (n = 18) was the Parentification Questionnaire (PQ). It was first developed by Sessions and first presented in its 42-item format with psychometric properties in a thesis [115]. The original measure includes three subscales assessing instrumental and emotional parentification and perceived unfairness. A few studies used only one or two of the original subscales. Reliabilities ranged from 0.61 to 0.92 with four studies having Cronbach alphas below 0.70 and typically included younger participants (adolescents or young adults).

The second most commonly used measure (n = 14), the Parentification Inventory (PI), was developed by Hooper [116]. The 22-item scale includes three subscales: parent-focused parentification (PFP), sibling-focused parentification (SFP), and perceived benefits of parentification (PBP). Alphas ranged from 0.58 to 0.89 with the SFP characterized by lower reliability. The third most often used measure (n = 10) was the Parentification Scale (PS), which was developed by Mika and colleagues [117]. This 30-item scale includes four subscales: (1) child is parent to parent; (2) child is spouse to parent; (3) child parents siblings; and (4) child acts in all three ways. Alphas ranged from 0.57 to 0.95.

A less commonly used measure (n = 7), the Filial Responsibility Scale, Adult Version (FRS), developed by Jurkovic, Thirkield, and Morrell [118], includes 60 items to assess six subscales: Past and Current Instrumental Caregiving, Past and Current Emotional Caregiving, and Past and Current Unfairness. Alphas ranged from 0.74 to 0.94. The Parentification Questionnaire for Youth (PQ-Y), developed by Godsall and Jurkovic [119] and modified from the adult version [120], was used by five studies. It includes 20 items that assess emotional and instrumental parentification without explicit subscales. Alphas ranged from 0.64 to 0.80. Six measures detailed in Table 4 were used by three (Family Structure Survey and Inadequate Boundaries Questionnaire) or two studies (Child Caretaking Scale, Childhood Questionnaire, Parent–Child Boundaries Scale III, and Relationship with Parents Scale).

Several parentification measurement patterns were observed. First, studies typically focused on role-based (e.g., sibling-focused) or function-based (e.g., emotional) parentification, and it is not common that studies assess all these dimensions of parentification. Second, there is a dearth of measures designed to capture the parentification of youths either assessing their current experiences of parentification or retrospective parentification accounts of earlier experiences. Studies that included youth or youth measures reported lower reliabilities, suggesting effort should be made to develop a more reliable measure for youth. Third, most measures assessed adult retrospective accounts of parentification during childhood. Only one of seven studies using the Filial Responsibility Scale, Adult Version used current subscales, whereas the others focused on past subscales.

Table 4.

Parentification Measures—Descriptions, Modifications, and Reliabilities.

Table 4.

Parentification Measures—Descriptions, Modifications, and Reliabilities.

| Measure Name & Description | Literature | Participant Group | Modifications | Alpha | Sample Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Parentification Questionnaire (PQ) [115]: 42 Items, self-report, rate from 1 (usually not true/strongly disagree) to 5 (usually true/strongly agree) or true/false; 3 subscales: emotional and instrumental parentification, and perceived unfairness [17]: says only instrumental and emotional) (one article said that there are no official subscales). Includes emotional, expressive, and physical statements. The questions were summed. | Arellano et al., 2018 [40] | Adults | Use continuous PQ subscale scores and dichotomized subscale scores (subscales dichotomized into never/rarely experienced as scored less than 2 vs. some/repeated experiences as scored 2 and above); This study also used Parentification Inventory | Instrumental: 0.85 Emotional: 0.85 Unfairness: 0.92 | College students |

| PQ | Carroll and Robinson, 2000 [49] | Adults | None | None reported | College students; have/do not have alcoholic and/or workaholic parents |

| PQ | Castro et al., 2004 [50] | Adults | None | None reported | College students in clinical and counseling psychology graduate programs |

| PQ | Hooper et al., 2008 [17] | Adults | None | Emotional: 0.75 Instrumental: 0.80 | College students |

| PQ | Jankowski and Hooper, 2014 [67] | Adults | Only used the perceived unfairness scale (PQ-UN) | Perceived Unfairness: 0.89 | College students |

| PQ | Jankowski et al., 2013 [68] | Adults | None | Instrumental: 0.84 Emotional: 0.84 Perceived Unfairness: 0.90 | College students |

| PQ | McGauran et al., 2019 [76] | Adults | None | 0.83 | Offender/non-offender samples; all white |

| PQ | Oznobishin and Kurman, 2009 [85] | Study 1: Adults Study 2: Adolescents | Study 1: Combined PQ with Parent–Child Role Reversal Scale from the Family Structure Survey [121] (49 items total); Two factors emerged: child dominance (16 items) and family support (9 items) Study 2: Child dominance (27 items; from Study 1 and other role reversal questionnaires assessing emotional and instrumental) Both studies: translated into Hebrew and Russian | Study 1: child dominance: 0.80 (immigrants); 0.85 (Israeli- born) Study 2: child dominance: 0.89 (immigrants); 0.91 (Israeli-born) | College students (Study 1) and high school students (Study 2); both studies include immigrant or Israeli-born |

| PQ | Rogers and Lowrie, 2016 [90] | Adults | Only used 21 items without specification what items they selected | Age ranged from 19 to 92 years old; 82.4% Caucasian | |

| PQ | Titzmann, 2012 [98] | Adolescents and their mothers | Translated into Russian and German; Used 2 subscales: Emotional and instrumental [17,110]; Items based on PQ and Parentification scale [117,120]; Emotional and Instrumental: mean of five items rated on a six-point scale | Emotional: 0.70 Instrumental: 0.69 | Ethnic (185) and 197 native German families |

| PQ | Titzmann and Gniewosz, 2018 [99] | Adolescents and their mothers | Only assessed instrumental; mean of 5 items; 6 pt Likert scale; based on Parentification Scale [117] too | Instrumental: 0.69 | Ethnic German immigrant mother-adolescent dyads from the former Soviet Union |

| PQ | Van der Mijl and Vingerhoets, 2017 [103] | Adults | None | 0.84 | College students |

| PQ | Wei et al., 2020 [114] | Young adults | Three items were used from each subscale | Instrumental: 0.61 Emotional: 0.66 Perceived fairness: 0.77 | Junior and senior high school students |

| PQ | Wells and Jones, 1998 [108] | Adults | None | None reported | College students |

| PQ | Wells and Jones, 2000 [109] | Adults | None | None reported | College students |

| PQ | Wells et al., 1999 [107] | Adults | None | None reported | College students |

| PQ | Williams and Francis, 2010 [110] | Adults | None | None reported | College students |

| PQ | Yew et al., 2017 [112] | Adults | None | 0.79 | College students in clinical and nonclinical academic programs |

| The Parentification Inventory (PI) [122,123]: adult self-report, 22 items on a 1 (never true) to 5 (always true) response scale; three subscales include parent-focused parentification (PFP), sibling-focused parentification (SFP), and perceived benefits of parentification (PBP). Scales are summed and averaged | Arellano et al., 2018 [40] | Adults | NA as an option on PI; Only parent-focused and sibling-focused parentification subscales; subscales were dichotomized (rarely or never experienced vs. those who had some level of or repeated experience); Also used the PQ [118] | Parent-focused: 0.78 Sibling-focused: 0.65 | College students |

| PI | Beffel and Nuttall, 2020 [42] | Adults | None | PFP: 0.83 SFP: 0.79 PBP: 0.88 | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) |

| PI | Borchet and Lewandowska-Walter, 2017 [43] | Late adolescents | Experimental version of the Polish adaptation | PFP: 0.80 SFP: 0.58 PBP: 0.81 | Individuals |

| PI | Borchet et al., 2016 [46] | Late adolescents and their parents | Used Kwestionariusz Parentyfikacji (KP)- experimental version of the Polish adaptation of the PI | PFP: 0.75 SFP: 0.60 PBP: 0.89 | Family triads; families recruited through students |

| PI | Borchet, Lewandowska-Walter, Połomski, Peplińska, and Hooper, 2020 [45] | Late adolescents | Used a Polish adaptation of PI; used the perceived benefits of parentification subscale only | PBP: 0.77 | School students |

| PI | Burton et al., 2018 [48] | Early adolescents | None | PFP: 0.82 SFP: 0.63 PBP: 0.85 | Middle and high school students |

| PI | Chen et al., 2018 [53] | Adolescents (18–24) | Used 19-item three-factor structure of the scale: household responsibility, perceived benefits, and spousal parentification | Household responsibility: 0.87; Perceived benefits: 0.84; Spousal parentification: 0.77 | Transitional-aged youth |

| PI | Cimsir and Akdogan, 2021 [55] | Adults | Only used PFP subscale; adapted the PI into Turkish: Factor structure varied slightly for subscales (Turkish culture normalizing parentification) | PFP: 0.84 | College students |

| PI | Hooper et al., 2015 [66] | Adults | None | Total Sample: PFP: 0.79 SFP: 0.58 PBP: 0.80 | College students |

| PI | Hooper, Wallace et al., 2012 [3] | Adults | None | PFP: 0.83 SFP: 0.80 PBP: 0.80 Black: PFP: 0.83 SFP: 0.76 PBP: 0.80 White: PFP: 0.85 SFP: 0.79 PBP: 0.81 | College students |

| PI | Murrin et al., 2021 [78] | Adults | Only mentions PFP and SFP; likely only used 19 items | PFP: 0.83 SFP: 0.79 | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) |

| PI | Nuttall et al., 2018 [81] | Adults | None | PFP: 0.83 SFP: 0.79 PBP: 0.88 | College students; TD who reported having a sibling with ASD |

| PI | Tomeny, Barry, and Fair, 2017 [101] | Adults | Only used PFP and SFP | Each of the PI subscales ranged from 0.64 to 0.88 | College students; TD who reported having a sibling with ASD |

| PI | Tomeny, Barry, Fair, and Riley, 2017 [100] | Adults | 1 item removed from SFP to improve internal consistency | SFP: 0.72–0.88 | TD who reported having a sibling with ASD |

| Parentification Scale [117]: adult self-report, 30 items on a 1 (never or does not apply) to 5 (very often) response scale; subscales where child is functioning (1) as a parent to parent(s), (2) as a spouse to parents, (3) as a parent to sibling(s), and (4) in ways which transcend these subtypes. Includes particular subtypes (e.g., consoler, adviser, confidant, or peacemaker). Questions asked how often behavior occurred before the age of 14 and how often it occurred between the ages of 14 and 16. Differential weights were assigned to the questions depending on the age and physical/emotional burden | Fitzgerald et al., 2008 [58] | Adults | Only used 3 subscales (acting as a parent to parent, spouse to parent, and parent to siblings); Items were summed | Parent to parent: 0.76 Spouse to parent: 0.78 Parent sibling: 0.86 | College students |

| PS | Perrin et al., 2013 [87] | Adults | Only used 1 item from Parental Role with Parents subscale; The final scale included 17 items; Items were also drawn from Parent-Child Boundaries Scale III [124], Family Structure Survey [121], and Filial Responsibility Scale-Adult; Item sets asked about mothers and fathers | 17-item Parentification Scale created; Mothers: 0.94 Fathers: 0.93 | College students |

| PS | Sang et al., 2014 [20] | Adolescents and their mothers | Only used 3 of 4 subscales: (a) spousal role vis-a-vis parents (8 items); (b) parental role vis-a-vis parents (6 items); (c) parental role vis-a-vis siblings (12 items) | Range: 0.84 to 0.92 | Black and Hispanic mother; HIV-negative daughter; low-income inner-city sample recruited in agencies that provided services to HIV-infected women; victims of intimate partner violence; and those in substance use recovery |

| PS | Shin and Hecht, 2012 [94] | Adolescents | Two items from Parentification scale operationalized problem-solving parentification; 5 point scale, but went from strongly disagree to strongly agree; used FRS as well | None reported | Mexican-heritage; middle school students; use Wave 4–6 only |

| PS | Stein et al., 1999 [95] | Adolescents and one of their parents | Parental role with siblings was not used because not applicable to many of the study participants | Adult role-taking: 0.77 Spousal role: 0.75 Parental role: 0.67 | Non-infected adolescents of parents with AIDS |

| PS | Stein et al., 2007 [19] | Adolescents and one of their parents | Parental role with siblings was not used; many participants did not have siblings; used the mean | None reported | Children with HIV/AIDS-infected mothers |

| PS | Titzmann, 2012 [98] | Adolescents and their mothers | Translated into Russian and German; items based on PS and PQ [117,120] (Emotional and Instrumental: mean of five items rated on a six-point scale; selected individual items from subscales) | Emotional: 0.70 Instrumental: 0.69 | Ethnic (185) and 197 native German families |

| PS | Titzmann and Gniewosz, 2018 [99] | Adolescents and their mothers | Only assessed instrumental; mean of 5 items; 6 pt Likert scale; based on PQ [120] too | Instrumental: 0.69 | Ethnic German immigrant mother-adolescent dyads from the former Soviet Union |

| PS | Tompkins, 2007 [102] | Adults and Adolescents | 3 items deleted of the parental role to parent scale due to inadequate reliability (involved fathers or illness) | Mother/Child: Spousal role: 0.76 Parental role to siblings: 0.95/0.86 Non-specific adult responsibilities: 0.78/0.65 Parental role to parent: 0.69/0.71 | Children with HIV/AIDS-infected mother (n = 23) vs. children with HIV-seronegative mother (n = 20) |

| PS | Walsh et al., 2006 [105] | Adolescents | Translated into Hebrew and Russian; Deleted 3 items | Hebrew/Russian: Spousification: 0.73/0.84 Parental role for parents: 0.57/0.79 Parental role for siblings: 0.80/0.87 Nonspecific adult role taking: 0.82/0.78. | Study 1: Immigrants from former Soviet Union in Israel vs. Israel born; Study 2: Immigrants from former Soviet Union in Israel |

| Filial Responsibility Scale, Adult Version (FRS) [118]: adult self-report; 60 items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) response scale; 6 subscales: Past Instrumental Caregiving, Past Emotional Caregiving, Past Unfairness, Current Instrumental Caregiving, Current Emotional Caregiving, Current Unfairness | Cho and Lee, 2019 [54] | Adults | Only used past subscales | Instrumental: 0.74 Emotional: 0.78 Unfairness: 0.87 | College students |

| FRS | Madden and Shaffer, 2016 [75] | Adults | Only used past Emotional and past Instrumental subscales | Emotional: 0.82 Instrumental: 0.80 | College students |

| FRS | Nuttall, Ballinger, Levendosky and Borkowski, 2021 [80] | Adults | Only used three subscales (past) | 0.92 | Majority of mother sample were non-White (78.4%) and unmarried (74%) |

| FRS | Nuttall et al., 2012 [82] | Adults | Only used three subscales (past); summed subscales | 0.92 | Community sample; high-risk, first-time adolescent and adult mothers |

| FRS | Nuttall et al., 2019 [84] | Adults, adolescents | Used past emotional and past instrumental only | Both: 0.78 | Predominantly low-income and ethnic minorities; college students; psychosis-proneness sample |

| FRS | Perrin et al., 2013 [87] | Adults | Only used 4 items from Current Emotional Caregiving subscale (final scale created included 17 items); items written twice (one asked about mothers and one fathers); also used items from Parent- Child Boundaries Scale III [124], Family Structure Survey [121], and Parentification Scale [117]; never to almost always | 17 item Parentification Scale created: Mothers: 0.94 Fathers: 0.93 | College students |

| FRS | Shin and Hecht, 2012 [94] | Adolescents | Used two items from FRS operationalized adult parentification; used the Parentification Scale [117] as well | None reported | Mexican-heritage; middle school students; use Wave 4–6 only |

| Parentification Questionnaire for Youth (PQ-Y) [119]: 20 items, yes/no format, no official subscales, but some more emotional or instrumental in nature; modified version of the PQ-A [120]: items changed to present tense and 3rd grade vocab | Chen and Panebianco, 2020 [52] | Adolescents | Only used Emotional Parentification subscale; created instrumental parentification with 22 items from three other instruments | Kuder-Richardson reliability coefficient was 0.72 | Middle and high school students with at least one parent with a chronic illness |

| PQ-Y | Fortin et al., 2011 [59] | Children and their mothers | Remove 5 items that measured the family’s recognition of the child’s parentification due to reduced instrument reliability | 0.64 reported | Children exposed to domestic violence |

| PQ-Y | Godsall et al., 2004 [60] | Children and adolescents | Item total reduced to 20 (not appropriate for children, and did not meet item total correlation) | 0.76 Cross-validation: 0.75 | High-functioning/low-functioning children; students |

| PQ-Y | Hooper, Doehler et al., 2012 [65] | Adolescent and parent pairs | None | 0.80 | Rural community sample |

| PQ-Y | Van Loon et al., 2017 [104] | Adolescents and one parent | Translated into Dutch; no clear factor structure (emotional vs. instrumental) so used sum score | 0.69 | Adolescents living with a parent with mental health problems |

| Family Structure Survey (FSS) [121]: adult self-report; 50 items on a 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true) response scale; adults’ recalled perceptions of their family interactions on four dimensions of dysfunctional family structure: parent-child over involvement, fear of separation, parent-child role reversal, and marital conflict; total scale scores are not used | King and Mallinckrodt, 2000 [71] | Adults | None | Parent-child role reversal: 0.74 | College students; clinical/nonclinical samples |

| FSS | Oznobishin and Kurman, 2009 [85] | Study 1: Adults Study 2: Adolescents | Study 1: Combined PQ with Parent–Child Role Reversal Scale from the Family Structure Survey [121] (49 items total); Two factors emerged: child dominance (16 items) and family support (9 items) Study 2: Child dominance (27 items; from Study 1 and other role reversal questionnaires assessing emotional and instrumental) Both studies: translated into Hebrew and Russian | Study 1: child dominance: 0.80 (immigrants); 0.85 (Israeli- born) Study 2: Child dominance: 0.89 (immigrants); 0.91 (Israeli-born) | College students (Study 1) and high school students (Study 2); both studies include immigrant or Israeli-born |

| FSS | Perrin et al., 2013 [87] | Adults | Final scale created included 17 items; 3 items from the Parent-Child Role Reversal subscale; also used items from the Parent-Child Boundaries Scale III [124], Filial Responsibility scale and PS [117]; never to almost always | 17 item Parentification Scale created: Mothers: 0.94 Fathers: 0.93 | College students |

| Inadequate Boundaries Questionnaire [125]: adult self-report; 34 items on a 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always) response scale for different types of boundary dissolution with their own mothers as children; dimensions include guilt induction, blurring of psychological boundaries, parentification (emotional and instrumental), triangulation, and the use of psychological control | Golan and Goldner, 2019 [61] | Adults | Made a guilt-psychological control scale and boundaries-parentification scale | Triangulation: 0.87 Blurring boundaries: 0.62 Parentification: 0.87 Boundaries-Parentification: 0.89 | Young, first-time Jewish mothers of children aged 12–36 months |

| IBQ | Goldner et al., 2017 [62] | Adolescents | Parentification (both): 0.74 | Middle school students | |

| IBQ | Goldner et al., 2019 [63] | Adolescents | Completed the Parentification and the Enmeshment with the Mother subscales | Parentification: 0.74 Enmeshment: 0.69 | Convenience sample; drawn from mid- to high-SES middle schools |

| Child Caretaking Scale [126]: child self-report; 30 items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) response scale; designed originally for children living with a mother experiencing psychiatric difficulties | Khafi et al., 2014 [70] | Children and their mothers | 18 items were used to identified emotional (8 items) and instrumental (10 items) subscales | T1 Emotional: 0.59 T2 Emotional: 0.70 T1 Instrumental: 0.66 T2 Instrumental: 0.66 | Sample overrepresents mothers with anxiety, affective, and/or substance use disorders; predominantly low-income |

| CCS | McMahon and Luthar, 2007 [77] | Children and their mothers | 25 items used to define three dimensions of caretaking burden: responsibility to care for mother, responsibility for household chores, and responsibility to care for siblings | Care for mother: 0.63 Household chores: 0.61 Care for siblings: 0.75 | Urban, low-income children living with biological mothers; includes mothers (a) with drug problem, (b) with psychiatric problem, or (c) none of the two |

| Childhood Questionnaire (CQ) [127]: adult self-report; first 14 years; mothers and fathers; 20 items (only including subscales) assess parent-child relationships; dimensions include Perceived Love, Control, Ambition and Role Reversal (4 item scale on SES, individual items on separation and divorce of parents, eventual death of either or both of the parents, and education and occupation of the parents during the subject’s childhood); 4 pt Likert scale from not true at all to absolutely true | Dragan and Hardt, 2016 [56] | Adults | None | None reported | Subjects all registered with a market research company |

| CQ | Schier et al., 2015 [91] | Adults | None | None reported | Internet survey; extraction and cross-validation samples |

| Parent–Child Boundaries Scale III (PBS-III) [124]: is a 53-item self-report measure. Measures general parentification (no empirically supported subscales of emotional or instrumental parentification, but have items indicative of these); 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always) | Perrin et al., 2013 [87] | Adults | 17 items were also drawn from the Filial Responsibility Scale—Adult, Family Structure Survey [121], and Parentification Scale [117]; items were asked about mothers and fathers) | 17 item Parentification Scale created: Mothers: 0.94 Fathers: 0.93 | College students |

| PBS-III | Baggett et al., 2015 [41] | Adults | Only used 6 items; items combined to create global parentification scale | 0.89 | College students |

| Relationship with Parents Scale (RPS) [128]: A 42-item (21 items: mother, 21 items: father) self-report retrospective measure of parent-child role reversal; 5-point scale 1 (strongly disagree)- 5 (strongly agree) | Abraham and Stein, 2013 [39] | Adults | Only used 21 items (Mother version: reflected mothers using guilt to elicit nurturing from them, demanding their attention or company, and their perception of their mother’s competence as a parent) | 0.93 | Emerging adults who have a mother with/without mental illness and poor psychological adjustment |

| RPS | Katz et al., 2009 [69] | Adults | None | Fathers: 0.89 Mothers: 0.92 | College students; grew up in an intact family with one mother and one father |

| Maastricht Parentification Scale [129]: self-report; 22 items on a 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree) response scale for parents reporting on both their own parenting and the parenting of their partner; low scores are indicative of psychological autonomy, whereas high scores are indicative of psychological control; 6 subscales of parentification: emotional care parents, buffer between parents, household care family, financial care family, instrumental care siblings, emotional care siblings | Boumans and Dorant, 2018 [47] | Adults | None | Emotional care parents: 0.78 Buffer between parents: 0.71 Household care family: 0.76 Financial care family: 0.68 Instrumental care siblings: 0.76 Emotional care siblings: 0.71 | College students; carers/non-carers |

| Parentification Questionnaire for Youth (PQY) [44]: self-report, 26 items on a 1 (never true) to 5 (always true) response scale, four subscales: emotional parentification toward parents, instrumental parentification toward parents, sense of injustice, and satisfaction with the role; and two subscales for adolescents who have siblings: instrumental parentification toward siblings and emotional parentification toward siblings. scores are calculated as the mean of the ratings for the subscale items | Borchet et al., 2021 [8] | Adolescents | None | 0.70 to 0.80 | Polish sample; majority self-identified college students |

| Perceived Parental Rearing Behavior Questionnaire [130]: adult self-report; 30 items on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time) response scale; dimensions include transmission, affection, punishing, over-involvement/protection | Hoffman and Shrira, 2019 [64] | Adults | Included 20 items; conceptualizes transmission as role reversal; translated to English | Role reversal: 0.71 Affection: 0.88 Punishing: 0.66 Overinvolvement: 0.70 | Community sample; Jewish parents of European origin born before 1945 and their offspring born after 1945; parents were alive during World War II and either Holocaust survivors or had no Holocaust background |

| Triangulation [131]: 45 items, 1 (totally disagree) to 3 (totally agree); 3 dimensions: cross-generation coalition, scapegoating, parentification | Wang et al., 2017 [106] | Children | 22 items were removed due to length consideration, or lack of association with other items as determined by exploratory factor analysis | Coalition: 0.79 Scapegoating: 0.75 Parentification: 0.72 | Two elementary school and three high school students |

3.3.2. Outcome Measures

Measure names, descriptions, study-specific modifications, and psychometric properties are presented in Table 5 for the constructs studied more than twice. Close to 30% of the studies are not included in Table 5 because they included constructs studied no more than twice. Broadly, the constructs excluded from Table 5 can be grouped into positive life outcomes, family relationships, and clinically relevant outcomes. Constructs in Table 5 are ordered based on the frequency of being studied. Within each construct, measures are ordered from the highest to the lowest frequency. Note that studies may appear multiple times when they investigated more than one construct or used more than one measure for one construct.

The most frequently studied construct was depression (n = 21), followed by internalizing and/or externalizing problems (n = 12). These constructs were all measured with well-validated instruments, and depression had good reliability. However, over half of the studies on internalizing and/or externalizing problems failed to report reliability for their specific studies.

Other negative outcomes include psychological/emotional distress which was often analyzed as a latent variable (n = 8), substance use (n = 10), antisocial behavior (n = 3), and risky sex (n = 3). The last three constructs were behavior-based measures and often measured by indicating the presence or frequency of the behavior [132,133]. Except for three studies that used the same instrument for substance use [3,65,67], no two studies used the same measures for antisocial behavior, risky sex, or substance use. Positive outcomes include self-esteem (n = 5), satisfaction with life (n = 3), and efficacy (n = 3), and they were measured similarly across studies with good reliability.

Several patterns were observed for outcome measures. First, outcome constructs were routinely assessed with well-validated instruments and reported good reliability. Second, only very few studies examined positive outcomes. This focus on adverse outcomes neglects the potential positive outcomes of parentification. Third, when constructs were only studied a couple of times, there is not ample evidence to conclude whether and how these constructs are related to parentification. Fourth, studies that focused on the same constructs only a few times were often conducted by the same researcher groups, which may suggest the limited research scope and lack of attempts to integrate individual research into the broader literature of parentification.

Table 5.

Outcome Measures—Descriptions and Psychometric Properties.

Table 5.

Outcome Measures—Descriptions and Psychometric Properties.

| Outcome Construct | Description | Literature | Sample Context | Modifications | Alpha | Associations with Parentification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) [134]: 21 questions, self-report, rate on a 4-point scale from 0 (absence of symptoms) to 3 (severe presence of symptoms) for depressive symptoms. Items are summed | Arellano et al., 2018 [40] | College students | Used continuous score and the dichotomized score for BDI-II (20 and above high; rest low) | 0.91 | PFP+, SFP ns, EP+, IP+, Unfairness+ |

| Carroll and Robinson, 2000 [49] | College students; have/do not have alcoholic and/or workaholic parents | None | None stated | Overall no direct test | ||

| Hooper, Doehler et al., 2012 [65] | Rural community sample | Adolescent self-report; parent self-report | Parent report: 0.94; Adolescent: 0.92 | Overall ns | ||

| Hooper et al., 2015 [66] | College students | 0.92 | PFP +, SFP +, PBP − | |||

| Hooper, Wallace et al., 2012 [3] | College students | None | Overall: 0.91 Black: 0.90 White: 0.92 | White: PFP ns, SFP ns, PBP −; Black: PFP +, SFP ns, PBP − | ||

| Jankowski et al., 2013 [68] | College students | Used it together with GSI from BSI to create a latent variable of mental health symptoms | 0.92 | Overall + | ||

| Prussien et al., 2018 [88] | Mothers with children diagnosed with cancer | Mother self-reported | 0.93 | Emotional caregiving ns | ||

| The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [135]: 20 items, self-report, rate on a 4-point scale from 0 (rarely or not at all) to 3 (most of the time). Items are summed. | Chen and Panebianco, 2020 [52] | Middle and high school students with at least one parent with a chronic illness | None | 0.90 | EP +, IP ns | |

| Cho and Lee, 2019 [54] | College students | None | 0.91 | EP ns, IP ns, Unfairness + | ||

| Katz et al., 2009 [69] | College students; grew up in an intact family with one mother and one father | None | 0.90 | Role reversal ns | ||

| Murrin et al., 2021 [78] | College students; typically developing (TD) who reported having a sibling with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | None | 0.87 | PFP ns, SFP ns | ||

| Nebbitt and Lombe, 2010 [79] | African Americans living in urban, public housing developments | Rated frequency of symptoms in terms of days per week from 0 (less than 1 day) to 3 (5–7 days) | 0.88 | Household contribution— | ||

| Wang et al., 2017 [106] | Two elementary school and three high school students | None | 0.86 | Coalition +, scapegoating +, Parentification − | ||

| The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [136]: 27-item, self-report, depressed mood. Rate from 0 (once in a while) to 2 (all the time) | Fortin et al., 2011 [59] | Children exposed to domestic violence | Used with the anxiety construct to form a latent variable internalizing problems | 0.84 | Overall + | |

| Khafi et al., 2014 [70] | Sample overrepresents mothers with anxiety, affective, and/or substance use disorders; predominantly low-income | T1: 0.81 T2: 0.87 | T1 IP and T2 dep ns, T1 EP and T2 dep + | |||

| Rodriguez and Margolin, 2018 [89] | Adolescents in active-duty military families | Omitted suicidal ideation item due to ethical and reporting concerns | 0.83 | IP −, EP ns, Observed emotional validation − | ||

| Tompkins, 2007 [102] | Children with HIV/AIDS-infected mother (23) vs. children with HIV-seronegative mother (20) | Only have range for all measures (0.70–0.89) | Mother report child’s parentification—(correlate only) | |||

| The Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) [137]: 18 items, self-report, rate on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). But Depression subscale only has 6 items. Mean score of 6 items for depression | Hoffman and Shrira, 2019 [64] | Community sample; Jewish parents of European origin born before 1945 and their offspring born after 1945; parents were alive during World War II and either Holocaust survivors or had no Holocaust background | Hebrew version; Parent completed interview and offspring completed questionnaires including depression subscale derived from BSI-18 | 0.86 | Role reversal + | |

| Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS-C) [138]: 30 items, self-report, rate on a 5-point scale form 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). 15 items each for the positive affect and negative affect scales | Burton et al., 2018 [48] | Middle and high school students | Positive affective is used as wellbeing; and negative affective is used as depressive symptoms | NA: 0.90 PA: 0.91 | PFP +, SFP ns, PBP − | |