Abstract

Objective: To conduct a scoping review to determine how past studies have applied the theory of intersectionality, a critical feminist research paradigm, to understand the physical health and mental health outcomes of perinatal people as a step toward addressing maternal health disparities and injustice. The study includes a review of existing research on maternal physical and mental health outcomes, presents the strengths and limitations of existing studies, and provides recommendations on best practices in applying intersectionality in research to address systemic issues and improve outcomes for the perinatal population. Methods: We conducted an extensive literature search across four search engines, yielding 28 publications using the intersectionality framework that focused on the outcomes of perinatal people, with a total sample of 9,856,042 participants. We examined how these studies applied intersectionality and evaluated them based on three areas: conceptualization, research method, and interpretation/findings. Results: Our findings indicate that maternal health researchers have provided good descriptions of the interaction of systemic inequalities and have used analysis that allows for the examination of interlocking and mutually reinforcing social positions or systems. We find that improvement is needed in the areas of conceptualization, reflexivity, and understanding of power structure. Recommendations are provided in the form of a checklist to guide future research toward an impactful approach to addressing perinatal health disparities. Relevance: Our scoping review has implications for improving applied health research to address perinatal health disparities, mortality, and morbidity. Recommendations are given along with references to other tools, and a guidance checklist is provided to support scholars in creating an impactful approach to applying intersectionality in the goal of addressing maternal health disparities.

1. Introduction

The United States is the only developed country that has seen rapidly rising rates of maternal mortality and morbidity over the last 25 years [1]; despite having one of the most expensive healthcare systems in the world [2]. Severe maternal morbidity affects approximately 50,000 to 60,000 U.S. women each year throughout the entire perinatal period, and these numbers are increasing, with the most pronounced disparities being quantified by race, ethnic, socioeconomic, and insurance status [3,4]. Systemic inequality has contributed to these disparities. An increasing number of health researchers have begun to call for a more critical examination of structural issues embedded in social locations and healthcare systems that impact perinatal outcomes [5]. Intersectionality has become a popular research paradigm in population health research to explore structural inequality and bring about social change. However, there exists a lack of basic guidelines on how the intersectionality framework is applied in health sciences. There is an ongoing dialogue about how current research practices attend to the tenets of intersectionality to create real-world policy change and social impact [6]. Although there is no uniform approach to applying intersectionality, scholars have cautioned health researchers against common pitfalls, such as assuming “master” categories (e.g., gender, race, or class) to study [7,8]; summarizing; relying on an additive approaches [9,10]; linear analysis of the main effects based on separate and independent inequalities [11,12]; and lack of reflection on the role of the researchers and the impact of their identities/lived experiences on study design, implementation, and interpretation of research results [10,13,14]. The aim of our study is to conduct a scoping review of existing research to determine how past studies have applied the theory of intersectionality to explore maternal health disparities in physical health and mental health outcomes during the perinatal period (during pregnancy and up to one year of birth).

In addition, our work reviews existing studies and creates a checklist of requirements to help future researchers use intersectionality in maternal health research toward a more impactful approach. The findings provide insights on (1) how previous studies have used a critical approach to understand systemic inequality embedded in the realities of perinatal people, and (2) ways to improve the application of intersectionality toward the development of a checklist of guidelines for perinatal maternal health science. This insight further helps to produce important knowledge on structural inequalities and informs social change to address maternal health disparities in the perinatal period. In addition, our review strictly focuses on maternal physical and mental health outcomes during the perinatal period. We did this because we did not want to assume that the drivers of systemic inequity underlying perinatal health disparities are the same for infant health disparities. We also recognize that an intricate link exists between maternal and infant health disparities [15], especially in birth outcomes and this is a limitation in our approach to exclude all studies related to birth outcomes. Future studies should expand research inquiries on understanding both maternal and infant health disparities from a holistic perspective.

1.1. The Concept of Intersectionality

The initial expression of intersectionality started in the work of the Combahee River Collective (1977/1995), a group of Black feminists who described the simultaneous impact of both sexism and racism [16]. The concept of intersectionality already had deep roots in U.S. social and historical politics among the Black community when in 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw, a scholar in the field of law, coined the term “intersectionality” [17]. Building upon critical race theory [18] and Black feminist thought [19], intersectionality provides a lens to understand lived experiences without reducing individuals to single characteristics. The approach assumes that social identities are not “inseparable and shaped by the interacting and mutually constituting social processes and structures that are influenced by both time and place” [6]. In other words, intersectionality accounts for how different systems of marginalization and privilege are based on one’s positioning to produce the unique experiences of the individual and their community.

While intersectionality was coined in the field of law, it has been widely applied to other fields. These include the fields of social science, humanities, business, and industrial organization. Within these areas, the intersectionality framework helps researchers to conceptualize and contextualize the impact of systemic inequity on different individuals and collective experiences. Intersectionality began to gain more traction in health science and population research over the past decade. Notably, it became a common research paradigm for furthering the understanding of the complexity of health inequities. This has helped health researchers to strive toward structural change to address disparities in the healthcare system [20].

Additionally, the intersectionality framework can be applied to many types of research approaches. For example, existing qualitative studies in health science have applied intersectionality to conceptualize and examine researchers’ and participants’ social positioning [10,21,22]. However, few research studies have focused on the physical health and mental health outcomes of perinatal people, with studies emerging only recently [23,24,25,26,27]. Notably, the work of Sen et al. [28] on gender inequality within a global economic and public health context covered the struggle of pregnant people in rural India from an intersectionality perspective. Our review did not find any studies that used mixed-method approach, which was a limitation of the existing literature. In summary, intersectionality is an important critical theory that holds the potential to bring about social change and address injustice through research.

1.2. Current Study

The objective of our scoping review is to examine how existing research in maternal health has applied intersectionality in their study approach and conceptualization. We focus on how the application of intersectionality has been used to explore health disparities in maternal physical health and mental health outcomes during the perinatal period. The goal of our study is to learn about the strengths and limitations of existing works, and to provide recommendations regarding best practices, as well as a checklist for future research, to study maternal health disparities. In our study, we defined the intersectionality framework as a critical constructivist research paradigm with a focus on examining the interactions of multiple systems of oppression, power, and privilege that have shaped the lived experiences of people. To this end, the intersectionality framework also examines power positionalities of the healthcare system and all stakeholders from historical and cultural contexts in the field of perinatal health. To evaluate all studies included in our scoping review, we identified a list of research questions (Table 1) inspired by, and adapted from, colleagues [6,7]:

Table 1.

Research Questions.

Based on our analysis and results, we considered additional questions to determine recommendations for future research. These questions included: what are the strengths and limitations of existing studies? How do we develop a checklist of guidelines for a research approach based on intersectionality to produce empirical evidence, balance research power among stakeholders, and translate learned knowledge into real-life impact rooted in social justice values?

2. Methods

The current scoping review followed the framework and method developed by Arksey and O’Malley [29], as well as recommendations from the work of Munn et al. [30]. Our steps included: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

2.1. Identifying Studies

To identify relevant literature, we conducted a search across four search engines: Google Scholar, EBSCO, PsycINFO, and PubMed. Keywords used to identify studies included combinations of the following terms: “depress*” OR “anxiety” OR “anxious” OR “mental” OR “psychological” OR “physical” OR “medical” OR “stress” OR “distress” OR “cardiovascular” OR “cardiomyopathy” OR “cardiac” OR “hypertension” OR “preeclampsia” OR “diabetes” OR “obesity” OR “infection” OR “hemorrhage” OR “eclampsia” OR “abruptio placentae” OR “placenta previa” OR “asthma” OR “respiratory” OR “mortality” OR “morbidity” OR “comorbid” AND “maternal” OR “perinatal” OR “pregnancy” OR “*partum” OR “antenatal” OR “postnatal” OR “prenatal” AND “intersectionality” OR “positionality” OR “positioning” OR “reflexivity”. We used intersectionality and positionality as synonyms in our search strategy to achieve a broader search. Duplicates, dissertations, theses, and/or studies of insufficient relevance were excluded. We included studies with original research that were published in English, and which strictly examined perinatal health outcomes through an intersectional perspective.

2.2. Literature Selection

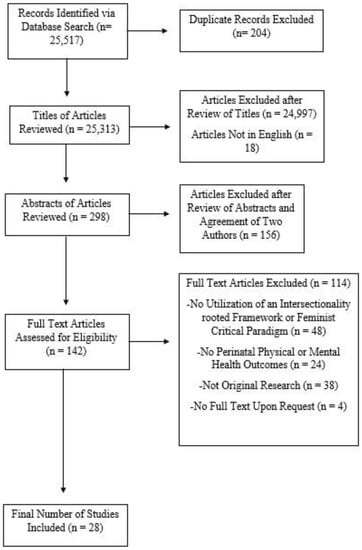

Initially, our search produced 25,517 records. We excluded 204 duplicate articles, and then further excluded articles if their titles did not allude to a focus on perinatal maternal health outcomes. After excluding these titles, 298 pieces of literature remained. Both authors read the abstracts of all remaining articles to determine eligibility. Studies of birth outcomes that focused on preterm birth and low-birth weight were then excluded, as these outcomes overlapped with infant health outcomes. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion included: (1) use of an intersectionality framework in the research approach/design, (2) inclusion of at least one maternal physical or mental health outcome during the perinatal period (from pregnancy to up to one year of birth), (3) written in English, and (4) inclusion of original research and not a review or opinion. After determining eligibility, a total of 32 research papers remained. Certain articles were not directly accessible because they were locked behind a paywall or did not have the full-text version. For articles that were not directly accessible, we attempted to access them through an interlibrary loan or by contacting the authors directly. After discarding inaccessible articles, 28 eligible, original articles remained. Our final sample included 28 published original research articles with a total sample of 9,856,042 participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the search and criteria for inclusion in our scoping review.

2.3. Charting and Summarizing Data

We first created a standardized worksheet to evaluate the 28 published research articles and to summarize the data. This worksheet included the findings of each article and the research questions used to evaluate each study individually. We reviewed, analyzed, and summarized the results. To provide a cohesive analysis of the studies, we utilized a standardized form to evaluate the studies based on each research question. There was a column for each research question, and any details about each study that directly answered the research question were extracted and charted under each column by both authors. We determined that if a research study included at least one detail or one step that directly answered our research question, it was considered “satisfied” for our evaluation. Each author evaluated each study independently and we met together seven times to discuss differences and to reach a consensus. Differences in our evaluation were discussed and each reviewer spent additional time revisiting each study. Consensus was reached based on an iterative process of reviewing and evaluating until all differences were resolved. We summarize our results in two tables: Table 2 displays the characteristics of each study, which Table 3 shows a summary of the findings based on our research questions. A checklist is presented in Table 4 to guide researchers on how to apply intersectionality in future studies.

Table 2.

Study Characteristics.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Study Using Intersectionality.

Table 4.

Guideline Checklist to Apply Intersectionality Framework in Perinatal Health Research.

3. Results

We included 28 published articles conducted on perinatal health outcomes. The majority of the studies (n = 16) were conducted in the United States and 12 studies were conducted in other locations (Israel, India, Australia, Romania, North America, Vietnam, Tunisia, Ireland, South Africa, Europe, and England). Out of these 28 original research articles, 11 used quantitative methods and 17 used qualitative methods. For this review, we were unable to find any mixed-method studies. For additional study characteristics, please refer to Table 2. In the following sections, we present our results which are based on the three main areas outlined in Table 1: conceptualization, research method, and interpretation/findings. We also display the quantitative and qualitative studies separately for a clear demonstration of the results.

3.1. Use of Intersectionality in Study Conceptualization

We examined studies for whether they discussed the effects of systems of inequality (i.e., racism, sexism, colonialism, etc.) on perinatal health outcomes. This was done in addition to examining the interactions of demographic and social identities among the studied population (Table 1, research question 1). We also assessed whether studies framed their research topic within the historical and current cultural, societal, and/or situational context (Table 1, research question 2). For example, a study on rural Aboriginal communities included the historical, social, and economic contexts of a rural population situated within the broader context of global economics and neocolonialism [20]. Another example study on gendered racism and maternal mortality focused on how the historical and current context of medical practices and reproductive rights within a state framed the experiences of Black, pregnant women [26]. By considering the history of reproductive rights in the US at the state level, Patterson and colleagues [26] accounted for the socio-historical context and structural power relations that shaped perinatal health disparities.

Overall, all 28 studies discussed the effects of multiple systems of oppression and structural inequality on the health outcomes of the perinatal population (Table 1, research question 1). Five of the quantitative studies used social and demographic variables as proxies to study the interaction of multiple systems of inequality on perinatal health outcomes. One example is Albright et al. [23], which used demographic variables such as age, race/ethnicity, annual income, state of residence, and veteran status as proxies by comparing them against mental distress, current cigarette use, and alcohol consumption of participants. Few studies (n = 5) included structural and contextual variables, such as poverty levels, crime rates, or state policies on reproductive care, to examine macro and meso-level social factors that impacted intersectional positions. For example, Seng et al. [37] included indicators that reflected both structural inequality factors, such as low education levels and poverty, and contextual factors, such as crime rate and trauma exposure, to operationalize meso- or interpersonal-level factors. Nine studies also included self-reported scales of perceived discrimination, such as gendered racial discrimination or everyday discrimination experiences, to account for the lived exposures of systemic inequities and social processes. For example, Clarke et al. [31] used subscales to measure stressors such as gender role strain, racial stereotyping, and racism/sexism in the workplace. Our findings also showed the most common methods in assessing intersectionality effects were regression with interaction terms, models using stratification, and categorized intersectional positions. These findings aligned with three systemic reviews to show that this was also a pattern across health science and public health research [13,60,64].

On the other hand, all identified qualitative studies included open-ended questions to examine the interaction of systems of marginalization on the lived experiences of participants. In summary, across both quantitative and qualitative studies, a total of 25 studies that framed their research topics within the current cultural, societal, and/or situational context. Only 18 of these 25 studies described the historical context that framed their research population (fulfilled both research questions 1 and 2 in Table 1). In summary, 18 papers (approximately 64%) fulfilled both research questions (Table 1, questions 1 & 2) in this section (see Table 3 for full analysis).

Quantitative Research. Among the quantitative research studies, 5 of the 13 studies fulfilled all research questions (Table 1, questions 1 & 2). The remaining 8 studies had a tendency to examine the interactions of systems of inequalities but did not frame the research question within the current cultural, societal, and/or situational context (see Table 3). One excellent example of a study that fulfilled both questions was by Rosenthal and Lobel [27]. This study measured the lived experiences of gendered racism using a scale rather than relying on interaction analysis of demographic variables to account for lived exposure of social and structural inequities. Furthermore, they analyzed historically rooted stereotypes that influence the experiences of oppression by perinatal Black and Latina women. For example, they discussed stereotypes related to sexuality and motherhood such as the “welfare queen” and “sexual siren” [27]. Rosenthal and Lobel [27] also extended their discussion to describe the history of medical experimentation on the studied population within the United States. In particular, they looked at the impact of forced sterilization of Black and Latina women. They were able to provide both a historical and current background to contextualize the health disparities experienced by perinatal Black and Latina women. Another example of a quantitative study that fulfilled both questions was the work of Patterson et al. [26]. This study framed their work within a historical context by taking into account the political environment in terms of reproductive justice within different states of the United States. They discussed and examined the supportability on reproductive rights within each state and the impact of state policies on maternal health outcomes.

Qualitative Research. There were a total of 17 qualitative studies. All of them met the criteria for fulfilling research question 1 from Table 1. Thirteen of them fulfilled question 2 by framing their research topics within the current and historical context (see Table 3 for full analysis). A good example was a study by Mehra et al. [48], where they discussed gendered racism within the economic, reproductive rights, and social justice contexts. They described historical and current stereotypes that stigmatized Black motherhood, such as the sexist, racist presentation of the “welfare mother” and the sexually aggressive “Jezebel” [48]. This study was able to explore both the interactions of social positioning and systemic forces within the social and historical contexts of the lived experiences of Black pregnant women.

3.2. Use of Intersectionality in the Research Method

For research methods, we evaluated the studies based on whether the authors mentioned power differences or dynamics that contextualized perinatal health disparities and the role of researchers within the socio-historical hierarchies (Table 1, research question 3). We also looked for studies that actively addressed the power differential, such as engaging key stakeholders in their research design and implementation to address the power differences and to include the voices of stakeholders when making important decisions (Table 1, research question 4). Along this line, we assessed whether researchers reflected on their identities, their roles in the research hierarchy, and how these factors impacted their decisions in designing, implementing, and analyzing the study. Lastly, we evaluated studies based on whether they used a multidimensional analysis to study intersectionality (Table 1, research question 5). Using a method that allows for multidimensionality is important when working with an intersectionality framework because of the impacts of the interlocking social positions of power. Therefore, it is impossible to pinpoint which social identities or processes are the most salient at any given time.

Our findings showed that the majority of studies (n = 19) did not discuss the social power relations that contextualize health disparities and their roles within the research hierarchy (Table 3). Seven out of the 28 studies engaged with stakeholder groups to allow for power sharing in determining their research approach and implementation. Furthermore, another 7 of 28 studies accounted for the impact of researcher positionality and/or lived experience on data collection and analysis. Additionally, almost all of the studies (n = 23) used data collection and analysis to allow a multidimensional understanding of intersectionality rather than relying on an additive approach. However, given that we only evaluated studies based on reflexivity and consideration of addressing power dynamics, only 4of the 28 studies (13%) in our scoping review met the criteria for satisfaction in this section (Table 3).

Quantitative Research. Within the quantitative studies, none met all of the criteria to satisfy our research questions in this section (Table 1, questions 3, 4 & 5). Most studies (n = 10) did not discuss the context of social and structural power or acknowledged the power differential in their research approaches. Further, most studies did not provide a positionality or reflexive description for their chosen methods and resulting interpretation. One quantitative study did include a stakeholder group to account for power imbalances during research design and implementation. For example, Vedam et al. [38] incorporated a stakeholder group of community agency leaders, clinicians, and researchers to develop research questions and adapt survey instruments for their study. This consultation allowed the researchers to work with stakeholders to develop survey items that best captured their unique perspectives and lived experiences. While Vedam et al. [38] did not discuss their reflexive process, the inclusion of a stakeholder group reflected their attention to issues of power within their study.

Furthermore, based on the recent metaanalyses of colleagues [13,60,64], quantitative methods are still adapting and developing to accommodate the core tenets of intersectionality. Our finding aligned with those of Bauer and colleagues [13] and Guan and colleagues [60] which showed that the majority of studies in our review used regression models with interaction terms to identify unique impacts of interlocking social positions and power. Although most statistical methods have the potential to explore intersectional effects, scholars suggest future researchers to provide a rationale for why they select a specific method or approach, to clarify underlying assumptions, biases and limitations of their methods, and explain how their chosen approach can be interpreted in the context of social and structural power [13,60]. We highlight here the most common methods to study intersectionality [13,60,64] in health science research: (1) regression with interaction terms (e.g., linear and other models with identity factors, multiplicative and other models with logit or log links, ANOVA-based methods, chi-square, t-tests), (2) additive and multiplicative scaling, (3) cross-classified variables, and (4) stratification. In addition, leading intersectionality scholars have asserted that the assessment of additive scale interaction is the most relevant for health-related research because it is a representation of intersectional multiplicativity [8,9]. Additive scale interaction is also noted to be helpful and more informative for clinical decision making and public health interventions [60,65].

Qualitative Research. Six of the 17 qualitative studies discussed the context of social and structural power as well as utilized a stakeholder group to account for power differences and to reflect upon the impact of the lived experiences of the researcher on the process of data collection and analysis (Table 3). Additionally, 13 studies incorporated a method to study identities at the multidimensional level (Table 1, question 5). One example was a study by Taylor et al. [52], which engaged a group of community members with lived experiences in data analysis and interpretation of results. This allowed for the voices of both researchers and stakeholders to be heard, and more importantly, be included in the data analysis and interpretation stages. This study also provided critical reflections on the experiences of the first author working in perinatal mental health and the experiences of the last author regarding the utilization of perinatal mental health. Lastly, Taylor et al. [52] framed their interview questions without prioritizing specific identities/experiences so that participants could describe their lived journey based on what they thought was important. For example, the research team asked questions such as: “Can you start by telling me a bit about your pregnancy?” and “How were things after birth?” [52]. The questions were framed so that the participants could reflect and describe social identities or processes that felt most salient to them.

3.3. Use of Intersectionality in the Interpretation and Findings of the Study

We determined whether the studies provided the context of structural barriers or inequity on the physical and mental health outcomes of perinatal women (Table 1, research question 6). Similar to the research method, we also assessed whether the researchers reflected on how their lived experiences and identities influenced the interpretation of the results (Table 1, research question 7). Our results showed that 25 of the studies mentioned the impact of systemic inequity on perinatal health outcomes. In contrast, only 6 out of 28 studies provided lived experience reflections from the researcher and how they potentially impacted the interpretation of the results. Only 5 studies satisfied both evaluation criteria in this section (Table 3).

Quantitative Research. None of the quantitative studies fulfilled both questions for this section (Table 1, questions 6 & 7). Despite this, all of the studies discussed the impact of systemic inequity on the health outcomes of the perinatal population. One study described forms of discrimination at the individual level, such as verbal abuse during provider interactions, disregard for autonomy, and rights to medical information [38]. Others described oppression at the macro level, including the impact of unequally distributed wealth, lack of social support, barriers to health care access, and barriers to upward mobility [36,66].

Qualitative Research. Only five of the qualitative studies fulfilled both research questions in this section (Table 1, questions 6 & 7). For example, Altman et al. [24] discussed how structural factors, such as historically racist and patriarchal systems withing the United States impacted patient–provider communication and healthcare delivery. Additionally, they provided a statement on how the lived experiences of the authors influenced the data interpretation. The researchers reflected upon how their racial identities and positions as healthcare providers shaped their interpretation of their findings.

4. Discussion

Maternal mortality and morbidity are currently critical issues in the United States, with alarming disparities among perinatal minoritized populations, who face multiple systems of oppression within the existing social structure of power. Intersectionality has the potential to move health science toward reducing maternal mortality and morbidity, addressing disparities, and transforming social hierarchies responsible for inequality [20,60]. As more maternal health researchers continue to develop methods and apply intersectionality to address perinatal inequities, our findings shed light on areas of strength and places for improvement so that future research can apply intersectionality in more impactful ways and strive toward improving perinatal health outcomes. Importantly, our review develops a checklist of considerations (see Table 4) to improve research approaches toward fostering systemic change and challenging current social and structural power that contribute to health disparities.

4.1. Conceptualization and Research Goals

Most of the studies reviewed here described current contexts that shape systemic disparities in both their conceptualization and interpretation sections. However, few of the studies discuss the socio-historical hierarchies that are responsible for power differential and current disparities and injustices. Similar to the explanations provided by Hankivsky [6] and Hancock [8], our findings demonstrate the common issue of inadequate conceptualization in research that uses intersectionality. This is especially prevalent when the studied categories are rooted in social processes and construction within existing power relations. To address this limitation, we urge researcher to follow the suggestions of intersectionality colleagues [6,13,60] to: (1) justify the use of intersectionality in an analytical approach, (2) explain how intersectional effects are examined through the chosen method, (3) draw connections between biological, historical, and social processes to help advance understandings of specific categories and illuminate why social context and power relations are so important for the construction of gendered health outcomes. An excellent example of the construction of gendered health outcomes that would be useful to reference is that from MacDonald et al. [45], which considered how pregnancy and the desire to be pregnant are seen as inherently feminine in Western culture, which could impact the experience of transmasculine individuals who desired to be pregnant.

Furthermore, we recommend researchers review our checklist along with other guidelines of conceptualization from leading intersectionality scholars [6,7,11,54,55]. For example, McCall [54] describes the differences between intracategorical approaches (i.e., focus on complexity of experience within a particular social position or intersection), intercategorical approaches (i.e, focus on heterogeneity across a range of intersections), and anticategorical approaches (i.e. the critique of rigid social categorization itself). Bauer et al. [13] concluded that most research works were intercategorical, which focused on describing inequalities across intersections. There needs to be more expansion in terms of other types of approaches because repeatedly documenting inequalities, even in finer intersectional detail, can serve to reinforce ideas of inherent differences between groups rather than to point towards actionable solutions [9]. Intersectionality is developed and rooted in Black feminist activism, so its main principle ties to the goal of advancing social justice [60,62]. Researchers should not disconnect, dilute, or depoliticize its original function in social change. Researchers should begin to incorporate social justice values and agendas into their conceptualization and research design [62]. The goal of intersectionality research should work toward identifying clear and implementable solutions to advance health equity and social justice [13,60].

4.2. Review of Research Methods

Our analysis shows that all included research studies recognized the impact of the interaction of systemic forces and identities on perinatal physical health and mental health outcomes. Almost all of the studies also used data analysis approaches to account for the interaction of multiple social systems and identities. However, the majority of studies focused on social identity factors rather than structural factors embedded in existing social processes (i.e., racism, sexism, or ableism). These findings are consistent with several recent systemic reviews on quantitative studies [13,60,64], which discuss how research approaches often do not contextualize their results within broader systems of power and oppression. On the other hand, qualitative studies have done a better job of acknowledging power structure and considering power differential in the research process. In summary, selection of research method highlights the researchers’ assumptions and biases. This process needs to continue to be developed because intersectionality does not originate as an empirically testable framework. Scholars routinely discuss the absence of guidelines and challenges regarding the appropriateness of different methods to capture the complexity of the tenets of intersectionality, especially when researchers overlook factors related to social power [13,57,60].

Many scholars across disciplines caution about the methodological issues of misrepresentation and inaccurate interpretation of demographic intersectional effects, especially in quantitative studies [13,64,67]. In a recent systemic review, Bauer and colleagues [13] critiqued common quantitative approaches, which included regression models with interaction terms between two or more social positions. These interaction terms often did not clearly distinguish between regression analyses of intersectional inequalities versus causal effects. Neither did they provide the rationale behind choice of multivariable analyses. We agree with colleagues [13,60], and recommend researchers to do more reflexive reflection about their chosen method including describing their rationale, limitations, or biases/assumptions inherent in their research, as well as how intersectionality framework is applied within their approaches. The process of making these explicit may also drive a deeper engagement with ideas in foundational and methods literature and require researchers to question the power structure embedded in the socio-historical construction of their categories as well as the limits of categorization [13]. We recommend researchers also review guidelines for quantitative research methods through the work of Guan et al. [60], Phillips et al. [64], Bauer et al. [13], and qualitative methods through the work of Bowleg [10,57], and Choo and Ferree [12].

4.3. Accounting for Social and Structural Power Relations toward a Stakeholder-Engaged Approach

Our results demonstrate that few studies account for broader social power relations within existing hierarchies. Notably, few researchers described their reflexive process on how their lived experiences and identities impacted their selections of research design, implementation, analysis, and interpretation. This finding is not new and is a part of the ongoing discussion about challenges in conducting intersectionality research and the importance of exploring epistemological assumptions made by the researcher when forming the methodology [8,10,14,68]. Leading intersectionality scholars [6,13,14,55,59,60] have urged researchers to reflect on their decisions during the research process and on power relations that are responsible for health disparities so that researchers are not replicating the patterns of exploitation and marginalization of studied populations. Previous tainted medical projects, such as the Tuskegee syphilis experiment in the Black community, the 1956 birth control trial among poor uneducated Puerto Rican women, or the forced sterilization of Black and Latina women, for the basis for mistrust and power differences between the studied population and health scientists. We take the stand that health science research should begin to address the power dynamics and be accountable in producing knowledge to make impact and challenge existing social and structural power relations, which contribute to current health disparities and injustices.

As a part of recognizing the power dynamics and striving toward larger social and political change, researchers need to pay attention to the power and the assumptions that they hold with regard to the research process. To this end, community-engaged, patient-engaged, or stakeholder-engaged research has been documented to be valued approaches due to their effectiveness in reducing health inequities, creating impact, and challenging the existing power hierarchy [69,70]. Findings from 126 studies funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) showed that contributions from stakeholders could be incorporated in all phases of the research process. This includes conceptualization, design, intervention, recruitment/retention, data collection/analysis, and dissemination [69]. Forsythe and colleagues [69] summarized the engagement effects into four themes: (1) acceptability (research agenda, goals and interventions were well received and aligned with stakeholder values and needs), (2) feasibility (roadblocks to effective implementation could be eliminated), (3) rigor (research choices that minimize bias and enhance data quality), and (4) relevance (research that creates impact for the community, patients, and providers). One study example was Taylor et al. [52], which used a lived experience group to create and revise research questions. They also collaborated with this group to draw out themes during data analysis to ensure that the experiences of women with perinatal depression were accurately reflected and interpreted by the stakeholders’ lived experiences. By doing this, their team began to address the power imbalance between researcher and participant. This allowed the study to produce results that were relevant to the population of interest as well as making real-world impact in the community as a part of the data dissemination process.

4.4. Checklist to Apply Intersectionality Framework

Table 4 presents our checklist, which builds upon previous research recommendations and methods that focus on person-centered and system-centered approaches as well as community-engaged partnerships through trusted relationships, power sharing, and transparency. When possible, we recommend researchers attempt to incorporate all steps of our checklist and consider all guiding questions in Table 3. We recognize that researchers do encounter limitations in their research approach based on their research questions and the types of data available. These limitations can be exacerbated by limited opportunities to engage stakeholders for secondary analysis. We, however, support the recommendation that intersectionality scholars need to ensure future researchers should be explicit regarding the explanation of aims, hypotheses, limitations, and application of intersectionality within their research approaches. These criteria recommend future researchers discuss the cultural, societal, and/or situational contexts of the intersectional positions that they study. The researchers are encouraged to describe the systems of oppression and power that shape/contextualize health outcomes, and justify for the selection of analytical method to capture intersectional effects. We recommend researchers to engage stakeholders whenever the design allows even at the last stage of the dissemination process. Lastly, although we do not think all research designs require reflexivity, we urge researchers to continuously reflect on where they are located in the hierarchy so that they do not perpetuate more experiences of marginalization in the research process [59]. By taking these steps, researchers will already begin to make an impact on addressing systemic health inequalities and injustices, especially when working with minority communities. Moreover, the intersectionality framework is rooted in social justice and activism. Hence, future researcher should be intentional in its research goal toward identifying clear and implementable solutions which can be used to advance health equity and challenge existing social hierarchies [60,62].

To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first scoping review in the field of perinatal health and mental health which looks at the application of the intersectionality framework. Our review provides a comprehensive understanding of how existing research has incorporated intersectionality in conceptualization and research design in addressing perinatal mortality, morbidity, and disparity. We recognize that a limitation of our study is that we only used published studies written in English. All of the included studies had perinatal women’s physical and mental health outcomes while excluding preterm birth and low-birth weight studies. This represents a limitation in our inclusion criteria as we recognized that birth outcomes were critical to both maternal and infant health disparities. Furthermore, we could not conclude that the results in our review would apply to the fields of infant and child health. We also included studies that only incorporated intersectionality in their conceptualization and research design, so we could not comment on the rest of the research literature on perinatal health outcomes that did not use the intersectionality framework. Additionally, four studies were excluded after all efforts had been made to gain access to them. Our sample also does not include any mixed-method studies, which demonstrates that this approach is lacking. Future research needs to explore these mixed methods more, as mixed methods have the potential to capture more tenets of intersectionality [6].

5. Conclusions

To address rising health disparities, mortality, and morbidity among perinatal people in the United States, we urge researchers to extend their approaches by incorporating intersectionality and following our checklist to create more impactful knowledge that brings about more meaningful social change. It is our goal that our checklist helps researchers by giving them tangible steps in methodology, and it is a place where resources are consolidated so that researchers can continue to expand their methods. Our overarching goal is to further the production of important knowledge on structural inequalities, which can then inform policy change and create a more meaningful impact in addressing health disparities in the perinatal population.

Author Contributions

T.-M.H.H. did the conceptualization, designed the methodology, conducted formal analysis, wrote, prepared, and edited the manuscript, supervised the second author, and received funding acquisition. A.W. did the data curation, and formal analysis, and contributed to writing the manuscript method and result sections. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Office of the Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the Chancellor’s Call to Action to Address Racism and Social Injustice Grant. Funding number H00222.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Karen M. Tabb for her feedback and guidance in the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Douthard, R.A.; Martin, I.K.; Chapple-McGruder, T.; Langer, A.; Chang, S.U.S. Maternal mortality within a global context: Historical trends, current state, and future directions. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanicolas, I.; Woskie, L.R.; Jha, A.K. Health care spending in the united states and other high-income countries. JAMA 2018, 319, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, E.; Zephyrin, L. Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States: A Primer; The Commonwealth Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert, D.L. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020; NCHS Health E-Stats: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2022.

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Johnson, T.L.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, A.-M. When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspect. Politics 2007, 5, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 110, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The Methodological Challenges of Qualitative and Quantitative Intersectionality Research. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J.C. Re-thinking intersectionality. Fem. Rev. 2008, 89, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.Y.; Ferree, M.M. Practicing intersectionality in sociological research: A critical analysis of inclusions, interactions, and institutions in the study of inequalities. Sociol. Theory 2010, 28, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R.; Churchill, S.M.; Mahendran, M.; Walwyn, C.; Lizotte, D.; Villa-Rueda, A.A. Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, L.R. A best practices guide to intersectional approaches in psychological research. Sex Roles 2008, 59, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maternal and Infant Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022.

- Combahee River Collective. Combahee River Collective statement. In Words of Fire: An Anthology of African American Feminist Thought; Guy-Sheftall, B., Ed.; (Original work published 1977); New Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 232–240. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1989, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.H. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky, O.; Reid, C.; Cormier, R.; Varcoe, C.; Clark, N.; Benoit, C.; Brotman, S. Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research. Int. J. Equity Health 2010, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.Y.; von Unger, H.; Armbrister, A. Church ladies, good girls, and locas: Stigma and the intersection of gender, ethnicity, mental illness, and sexuality in relation to HIV risk. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyal, L. Challenges in researching life with HIV/AIDS: An intersectional analysis of black African migrants in London. Cult. Health Sex. 2009, 11, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, D.L.; McDaniel, J.; Suntai, Z.; Horan, H.; York, M. Pregnancy and binge drinking: An intersectionality theory perspective using veteran status and racial/ethnic identity. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.R.; Oseguera, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Franck, L.S.; Lyndon, A. Information and power: Women of color’s experiences interacting with health care providers in pregnancy and birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 238, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove-Medows, E.; Thompson, L.; McCracken, L.; Kavanaugh, K.; Misra, D.P.; Giurgescu, C. I wouldn’t let it get to me: Pregnant Black women’s experiences of discrimination. Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2021, 46, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.J.; Becker, A.; Baluran, D.A. Gendered racism on the body: An intersectional approach to maternal mortality in the United States. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 1261–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, L.; Lobel, M. Gendered racism and the sexual and reproductive health of Black and Latina Women. Ethn. Health 2020, 25, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, G.; George, A.; Ostlin, P. Engendering health equity: A review of research and policy. In Engendering International Health: The Challenge of Equity; Sen, G., George, A., Ostlin, P., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, L.S.; Riley, H.E.; Corwin, E.J.; Dunlop, A.L.; Hogue, C.J.R. The unique contribution of gendered racial stress to depressive symptoms among pregnant Black women. Womens Health 2022, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, N.; Ali Saleh-Darawshy, N.; Meiyin, G.; Sergienko, R.; Sestito, S.R.; Geraisy, N. Multiple forms of discrimination and postpartum depression among indigenous Palestinian-Arab, Jewish immigrants and non-immigrant Jewish mothers. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, E.M.; Carmichael, S.L.; Berkowitz, R.L.; Snowden, J.M.; Lyndon, A.; Main, E.; Mujahid, M.S. Racial/ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: An intersectional lifecourse approach. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1518, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, C.S.; Butler, Z.; Everett, B.G. Disparities in smoking during pregnancy by sexual orientation and race-ethnicity. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.; Strobino, D.; Trabert, B. Effects of social and psychosocial factors on risk of preterm birth in Black women. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2010, 24, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Iyer, A. Who gains, who loses and how: Leveraging gender and class intersections to secure health entitlements. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, J.S.; Lopez, W.D.; Sperlich, M.; Hamama, L.; Reed Meldrum, C.D. Marginalized identities, discrimination burden, and mental health: Empirical exploration of an interpersonal-level approach to modeling intersectionality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 2437–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E. The giving voice to mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amroussia, N.; Hernandez, A.; Vives-Cases, C.; Goicolea, I. “Is the doctor God to punish me?!” An intersectional examination of disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth against single mothers in Tunisia. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalibi, N.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Roosevelt, L.; Wojciechowski, K.; Giniel, C. LGBTQ persons’ use of online spaces to navigate conception, pregnancy, and pregnancy loss: An intersectional approach. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2022, 29, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, R. Ambiguous subjects: Obstetric violence, assemblage and South African birth narratives. Fem. Psychol. 2017, 27, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, N.; Abu-Hamad, S.; Berger-Polsky, A.; Davidovitch, N.; Orshalimy, S. Mechanisms for racial separation and inequitable maternal care in hospital maternity wards. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huschke, S. ‘The system is not set up for the benefit of women’: Women’s experiences of decision-making during pregnancy and birth in Ireland. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMasters, K.; Baber Wallis, A.; Chereches, R.; Gichane, M.; Tehei, C.; Varga, A.; Tumlinson, K. Pregnancy experiences of women in rural Romania: Understanding ethnic and socioeconomic disparities. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, T.K.; Walks, M.; Biener, M.; Kibbe, A. Disrupting the norms: Reproduction, gender identity, gender dysphoria, and intersectionality. Int. J. Transgender Health 2021, 22, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, N.; Thomas, H. Choosing motherhood: The complexities of pregnancy decision-making among young black women ‘looked after’ by the state. Midwifery 2014, 30, e72–e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLemore, M.R.; Altman, M.R.; Cooper, N.; Williams, S.; Rand, L.; Franck, L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 201, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Boyd, L.M.; Magriples, U.; Kershaw, T.S.; Ickovics, J.R.; Keene, D.E. Black pregnant women “get the most judgment”: A qualitative study of the experiences of Black women at the intersection of race, gender, and pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues 2020, 30, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.V.; King, J.; Edwards, N.; Dunne, M.P. “Under great anxiety”: Pregnancy experiences of Vietnamese women with physical disabilities seen through an intersectional lens. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 284, 114231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staneva, A.A.; Bogossian, F.; Morawska, A.; Wittkowski, A. “I just feel like I am broken. I am the worst pregnant woman ever”: A qualitative exploration of the “at odds” experience of women’s antenatal distress. Health Care Women Int. 2017, 38, 658–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, N.R.; Heath, N.M.; Lillis, T.A.; McMinn, K.; Tirone, V.; Sha’ini, M. Examining the effectiveness of a coordinated perinatal mental health care model using an intersectional-feminist perspective. J. Behav. Med. 2018, 41, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.L.; Howard, L.M.; Jackson, K.; Johnson, S.; Mantovani, N.; Nath, S.; Sokolova, A.Y.; Sweeney, A. Mums Alone: Exploring the Role of Isolation and Loneliness in the Narratives of Women Diagnosed with Perinatal Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R.; Bartkowski, J.P. Negotiating patient-provider power dynamics in distinct childbirth settings: Insights from Black American mothers. Societies 2019, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L. The complexity of Intersectionality. Signs 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Crenshaw, K.W.; McCall, L. Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs 2013, 38, 785–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R.; Scheim, A.I. Advancing quantitative intersectionality research methods: Intracategorical and intercategorical approaches to shared and differential constructs. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 226, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, O. Health Inequities in Canada: Intersectional Frameworks and Practices; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, B. Situated moral agency: Why it matters? In Education Feminism: Classic and Contemporary Readings; Thayer-Bacon, B.J., Stone, L., Sprecher, K.M., Eds.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, A.; Thomas, M.; Vittinghoff, E.; Bowleg, L.; Mangurian, C.; Wesson, P. An investigation of quantitative methods for assessing intersectionality in health research: A systematic review. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 16, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.; Forsythe, L.; Ellis, L.; Schrandt, S.; Sheridan, S.; Gerson, J.; Konopka, K.; Daugherty, S. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, N.T.; Wiklund, L.O. Intersectionality research in psychological science: Resisting the tendency to disconnect, dilute, and depoliticize. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, L.S.; Zucker, A.N. Quantifying intersectionality: An important advancement for health inequality research. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 226, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.P.; Vafaei, A.; Yu, S.; Rodrigues, R.; Ilinca, S.; Zolyomi, E.; Fors, S. Systematic review of methods used to study the intersecting impact of sex and social locations on health outcomes. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 12, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Knol, M.J. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods 2014, 3, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, S.M.; Ehrenthal, D.B. Stressor landscapes, birth weight, and prematurity at the intersection of race and income: Elucidating birth contexts through patterned life events. SSM Popul. Health 2019, 8, 100460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S.; Welch, H.G. Misunderstandings about the effects of race and sex on physicians’ referrals for cardiac catheterization. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrod, L.R.; Torney-Purta, J.; Flanagan, C.A. Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 706. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, L.P.; Carman, K.L.; Szydlowski, V.; Fayish, L.; Davidson, L.; Hickam, D.H.; Hall, C.; Bhat, G.; Neu, D.; Stewart, L.; et al. Patient engagement in research: Early findings from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N.; Oetzel, J.G.; Sanchez-Youngman, S.; Boursaw, B.; Dickson, E.; Kastelic, S.; Koegel, P.; Lucero, J.E.; Magarati, M.; Ortiz, K.; et al. Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).