Abstract

According to a recent national audit, the cost of treating patients in geriatric wards is 20–30% less compared to those treated in internal medicine wards. Yet, geriatric care remains largely underdeveloped in Poland, with few human, material, and financial resources. Despite numerous attempts to raise the profile of geriatrics over the years, little progress has been achieved. In 2019, experts under the President of Poland proposed the creation of a network of Health Centres 75+ as the first pillar of geriatric care. These are meant to provide ambulatory services for older people and coordinate provision of other health and social care services at the county level. The goal is to create a community model of care, whereby older people would receive needed services close to their place of residence, allowing them to live independently for as long as possible. Although the proposal has been welcomed by the geriatric community and the patients, the acute shortages of human, physical, and financial resources raise concerns about its feasibility. However, the new strategic plans for the health system propose solutions that appear to be supportive of the new proposal, and the Office of the President is discussing joining forces with the Ministry of Health to improve its chances of implementation. Given the increasing pace of population ageing and underdeveloped provision of geriatric services, these efforts are very much needed.

1. Introduction

Poland is still a relatively young country compared to other countries in the European Union (EU). Its per capita gross domestic product (GDP) amounts to less than 80% of the average GDP in the EU. In 2019, the share of people aged 65+ in Poland accounted for 18.2% of total population, which is slightly below the EU average of 20.6% [1]. However, this share has been increasing faster in Poland than in other countries (a 4.6 percentage point increase between 2010 and 2020 compared to a 3 percentage point rise in the EU [2]); and is forecast to reach 30% by 2050, surpassing the projected EU average of 29.6% [3]. People aged 75+ accounted for 7% of the total population in Poland in 2020, compared to 9% in the EU, and these shares are forecast to increase to 51% and 57%, respectively, by 2050 [4]. Since older people often suffer from multiple comorbidities, frailty, and functional limitations to daily living tasks, they require more and substantially different health and care services than younger people [5,6,7]. Geriatric patients in Poland suffer from the following problems, comprising both age-related chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes that are common clinical presentations, such as falls and incontinence, that do not fit into specific disease categories but have substantial implications for functionality and life satisfaction [8]: hypertension (60% of geriatric patients), depression (52%), urinary incontinence (48%), falls (41%), dementia (35%), diabetes (31%), heart failure (27%), peptic ulcer disease (22%), protein and energy malnutrition (20%), delirium (19%), iatrogenic syndromes (17%), chronic kidney disease (17%), Parkinson’s disease (16%), and cancer (95) [9]. Older Poles declare having poor health more often compared to their peers in other countries in Europe—in 2019, 30.8% of Poles aged 65+ reported having bad or very bad health compared to 17.8% in the EU on average [10]. This share increases to 41.8% in people over 75 years of age, compared to 23.8% in the EU. The burden of chronic diseases and multimorbidity is also high among older Poles. According to the data collected within the PolSenior survey, up to 80% of people aged 65+ suffer from more than one condition [11] and people over 70 years old suffer from at least three chronic diseases [12]. In terms of performing activities of daily living, 34.1% of Poles aged 65+ report some or severe limitations compared to 26.1% in the EU (2014 data) [13]. These shares increase to, respectively, 36.6% and 28.8% for people aged 75+. All these factors increase the likelihood of the need for medical services among older people, including nursing and social care services.

Geriatric care offers a holistic approach to multiple health problems of older age that accounts for risks such as adverse consequences of polypharmacy, frailty, and mobility limitations [14,15]. Assessment by specialist geriatric teams, coupled with post-discharge interventions at home, has been linked to shorter hospitals stays, fewer readmissions, and fewer nursing home placements, and there is now considerable evidence that social care interventions, including early transfer to nursing homes or own homes with support from community-based health and social care services, can reduce hospital admission and length of stay [16].

The purpose of this Perspective piece is to describe the latest key policy proposal to improve provision of geriatric care in Poland put forward in 2019, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which focuses on the introduction of a network of ambulatory centres for people aged 75+ as the main pillar of geriatric care. Section 2 provides the policy background and describes earlier efforts to improve care for older people in Poland. Section 3 describes the content of the new policy proposal in more detail. Section 4 discusses factors that may affect its implementation, including by assessing the positions of key stakeholders towards the proposal, should the works on the proposal be resumed if the pandemic is able to be better controlled. Finally, Section 5 concludes and offers policy recommendations.

2. Policy Background

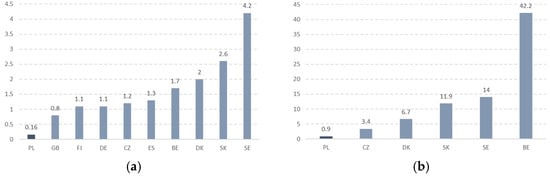

Since the early 2000s, numerous calls have been made to develop provision of geriatric care in Poland, with health policy analysts noting the large gap between geriatric resources in Poland compared to some countries in Europe, including the neighbouring Czechia and Slovakia (Figure A1 in Appendix A). Experts from the Polish Society of Gerontology have argued that development of geriatric care is desirable not only for social and ethical, but also for economic reasons, as it can extend the number of years lived in good health and improve functional mobility, thus reducing the need for health and care services [17]. A report by the Supreme Audit Office from 2015 found that the cost of treatment of patients in geriatric wards was 20–30% less than that of patients treated in internal medicine wards, and the annual cost of their pharmaceutical care was 10% lower [18]. Cost-effectiveness of simple geriatric interventions, such as comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) or preventive home visits are also well established (e.g., [19,20]).

Yet, geriatric resources have seen little improvement. According to the Supreme Chamber of Physicians and Dentists, in 2019, Poland had 502 physicians with a geriatric specialisation, of whom 488 (or approx. 0.7 per 10,000 people aged 65+) were professionally active [21] (the Ministry of Health provides a slightly lower number—462; [22]). However, it must be noted that only about half of physicians with a specialisation in geriatrics work as geriatricians [23] and that geriatrics is typically the second specialisation chosen by internal medicine or family medicine physicians, whose numbers have been falling over the years [22]. According to the National Consultant in Geriatrics, the recommended number of geriatricians should be 7.8 per 100,000 inhabitants, compared to the current number of 1.2 per 100,000 [22]. The number of nurses specialising in geriatrics in 2019 amounted to 2552 (or approx. 3.7 per 10,000 people aged 65+) [21].

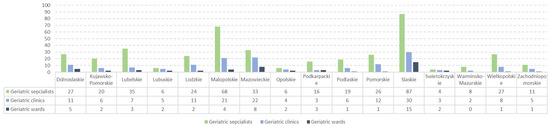

Since 2015, there has been at least one geriatric care ward in all regions except one (Warmińsko-mazurskie in the north-east). Most of them are located in the Silesian region (southern Poland), which is forecast to become one of the oldest regions in Poland by 2030 and where geriatrics has been declared a regional priority (Figure A2 in Appendix A) [24]. The Mazowieckie region, where Poland’s capital (Warsaw) is located, had the second highest number of geriatric wards in 2019. Despite these improvements, resources remain insufficient [25]. For example, geriatric clinics can be found in only 41 of 374 counties, with the highest numbers located in Cracow (8) and Warsaw (9) [26].

Numerous efforts have been made over the past two decades to raise the profile of geriatrics in Poland, starting with the recognition of geriatrics as a priority area for specialist medical training (Table 1). These attempts have been led by various actors, including the community of geriatric specialists, the Ministry of Health, the Civil Rights Ombudsman, and the President of Poland, and should be seen in the contexts of the provision of long-term care (LTC) and social care services, which are also seen as largely underdeveloped in Poland [27,28]. The need to strengthen provision of geriatric care has been recognised in numerous conferences, seminars, and reports. For example, a report published in 2015 by the National Audit Office drew attention to the deficits of geriatric services in Poland and the urgent need to build an effective system of care for older people, complete with a support system for their next of kin [18]. These calls were reiterated in another National Audit Office report published in 2021 [9].

Table 1.

Key policy changes in geriatric care and related areas, 2000–2021.

Despite these efforts and calls, little actual progress has been made in strengthening the role of geriatrics in the health system. On the contrary, its position has been recently weakened. For example, geriatrics has been omitted from the health need maps developed since 2015, which is a planning tool that is meant to improve contracting of health services by the public payer (the National Health Fund, NHF). Geriatrics is also largely missing from the hospital network introduced in 2017, on the basis of which the NHF contracts hospital services, where geriatrics was constrained to the 3rd level of hospital provision (i.e., mainly regional hospitals). Geriatric wards operating in the 1st and 2nd reference level hospitals (i.e., mainly in county hospitals) are not included in the network, which means they do not benefit from lump-sum contracting that is awarded to hospitals included within the network [29]. Public coverage of geriatric syndromes remains minimal and the few services that are included are underpriced, despite the recognised potential savings that provision of such services could bring [18]. For example, CGA, which is an important element of geriatric care, is not financed at the level of primary and outpatient specialist care, and geriatric rehabilitation is not financed by the NHF (it can be provided at medical nursing homes (Zakład Opiekuńczo–Leczniczy, ZOL) and is financed from the state or paid for privately by the patients).

Given the existing shortages of dedicated geriatric services, older patients usually seek medical care from primary health care (PHC) doctors, constituting the key users of primary care services [18]. Since this patient group often suffers from complex health problems, PHC doctors are compensated with higher capitation rates for older patients on their lists—2.7 times higher for people aged 66–75 and 3.1 times higher for people over 75 years of age. Higher capitation rates are also applied for residents of social welfare homes (Dom pomocy społecznej, DPS) (3.1 times higher) and patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and thyroid diseases (3.2 times higher) [30]. Coordination of health and care services for older patients, and exchange of information between the various elements of the health and social care systems, are perceived to be among the biggest problems faced by the PHC doctors [11].

3. Policy Content

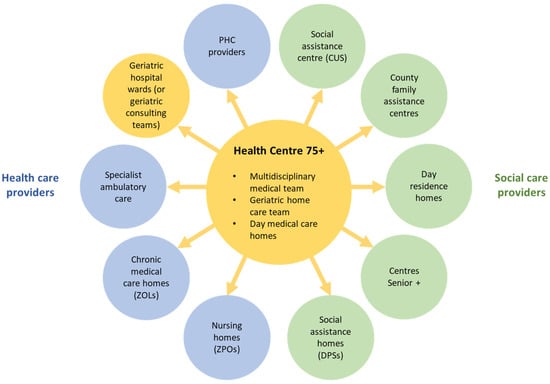

In 2019, a team of experts associated with the National Development Council under the President of Poland and the Ministry of Health put forward a new proposal to improve geriatrics and care for older people more generally [31]. Its central idea is the creation of a network of Health Centres 75+—one in each county, i.e., one per about 100,000 inhabitants—providing ambulatory services for older people as the first pillar of geriatric care in Poland. These Centres could operate either out of county hospitals or larger PHC practices. The role of these Centres is to coordinate, in cooperation with family physicians and social assistance institutions, care for older people at the county level (Figure 1). This is meant to include not only geriatric diagnostic and treatment services, but also social care and rehabilitation services, and relevant services provided by the local self-governments and nongovernmental organisations. Older people attending these Centres would be looked after by an interdisciplinary team, which should include, among others, a geriatrician, a psychiatrist, and a physiotherapist, and would be assigned a treatment coordinator. The new Centres will comprise day medical care homes providing medical services for older people requiring rehabilitation services after hospital discharge and home care teams supporting patients at their homes. The model also foresees that the Health Centres 75+ would employ health educators to provide family and other informal carers with basic information on care and medical procedures. The goal is to create a community model of care, whereby medical and social services for older people are provided close to their place of residence, in order to support them in living independently for as long as possible, and to reduce the number of hospitalisations.

Figure 1.

Proposed organisation of care for older people organised around Health Centres 75+. Source: Authors based on [31]. Notes: CUS = Centrum Usług Społecznych (social assistance centre); DPS = dom pomocy społecznej (soccial assistance home); ZPO = zakład pielęgnacyjno-opiekuńczy (nursing home).

Geriatric hospital wards are meant to constitute the second pillar of the new model. The proposal assumes increasing the number of geriatric wards to 100–120, i.e., approximately one ward per 300,000–350,000 inhabitants. This is not meant to lead to an increase in the number of hospital beds; instead, the proposal suggests transformation of some of the existing hospital beds into geriatric care beds. Every geriatric ward is meant to serve 3–4 Health Centres 75+. These wards would take over geriatric patients from other hospital wards, and serve geriatric patients referred to by the Health Centres 75+. After discharge, patient files would be passed to the Centres with recommendations for any follow-up medical care.

The model further assumes that every person aged 75+ would undergo a basic geriatric assessment at the PHC level to detect any significant health problems and determine the degree of independence so that they can start treatment and be connected with other (social care) services they need as early as possible. Patients identified as geriatric patients would undergo a CGA by a geriatric medical team at the Centre led by a treatment coordinator.

4. Discussion

The draft law on Health Centres 75+ was expected to be referred to the parliament in the first half of 2020, but this was postponed due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. This prevented a broader public debate over the proposal. Nevertheless, positions of the key stakeholders can be discerned from various reports, press articles, and expert opinions.

The Office of the President has clearly been the driving force behind the policy proposal, but needs support from other stakeholders, particularly from the Ministry of Health, to pass the proposal into the law. The proposal has been welcomed by geriatric physicians and patients (as represented, for example, by Patients’ Rights Ombudsman and the Coalition ‘To help the dependent’), but these and other stakeholders share much scepticism about its feasibility [11]. The key reasons for concern are the acute shortages of human and physical resources (geriatricians, geriatric nurses, and geriatric wards) and the very low level of financing of both geriatrics, and long-term (and social) care and rehabilitation services, which are all in in dire need of investment [12]. There is also a lack of clarity about patient pathways at the intersection of the new model with PHC, outpatient specialist care, and social care services; for example, many residents of social welfare homes are currently not registered with a family doctor [32,33].

The position of the PHC physicians and the counties has so far been ambivalent since there is no detailed information about the patient pathways within the new model or about its funding. PHC doctors may see the Centres as an opportunity to relieve them of some of their duties, while at the same time ensuring better care for geriatric patients and improving coordination of services [11,34]. However, since they also receive high capitation rates for treating older patients (see above), they may be reluctant to lose this stream of income. The counties, who are meant to be the founders of the new Centres, may not be inclined to take on more responsibilities without receiving additional funding, as their health budgets are currently very limited [35,36]. At the same time, they may be under pressure to respond to the demands of their local populations, which are increasingly older and progressively better organised, such as in the Senior Councils, which have increased in numbers in recent years, and which can exert influence over social and health policies [37,38].

The Ministry of Health, the stakeholder with the most influence in the system, has so far not shown much support for the project. In addition to the reasons outlined above, other reasons for this may include poor cooperation between the Ministry and the social care sector, and the lack of clarity about the division of costs between health and social care in the proposed model. There is also a concern that the introduction of a dedicated solution for geriatric patients may lead to demands for similar solutions from other population groups. Finally, the Ministry may not feel much ownership over the project since it was driven by the Office of the President.

The National Reconstruction Plan, which at the time of writing (May 2022) was yet to be approved by the European Commission, will—if approved—trigger a release of funds from the EU’s Reconstruction Fund that can be used for implementing health sector and other reforms. These are set out in the National Transformation Plan for 2022–2026 published in late 2021, which is an executive act and has been guided by the framework document for the health sector—’Healthy future. Strategic framework for the development of the health care system for the years 2021–2027, with a perspective until 2030’. Although the Plan does not directly support the creation of Health Centres 75+, it makes a series of recommendations in the area of geriatrics and long-term care that are compatible with this policy idea. With respect to geriatrics, the Plan focuses on improving quality of and access to hospital care, calling for a transformation of at least 850 hospital beds in wards with low occupancy rates into geriatric beds. With respect to long-term care, the Plan foresees several actions including: (1) transformation of some of existing hospital beds into long-term care beds providing residential nursing and care services; (2) development of community long-term care in Day Medical Care Homes (Dzienny Dom Opieki Medycznej, DDOM) and inclusion of services provided in these homes in the basket of guaranteed services; (3) inclusion of long-term care services provided by medical caregivers (Table 1) in the basket of guaranteed services; and (4) development of a training programme and a psychological support programme for informal carers who look after older people with limitations in daily living activities. All these measures can be seen as supportive from the perspective of the proposed Health Centres 75+ model.

The Plan also foresees a range of measures to strengthen PHC, including by improving coordination of care, home care, and health promotion. These activities will be informed by learning from the pilot of the PHC PLUS model, which ended in late 2021 (Table 1). This can also be regarded as a positive development, given that the originators of the Health Centre 75+ proposal see PHC as a bridge that that can support development of the Centres before they become fully functional [11]: since family doctors play the role of gatekeepers in the Polish health care system, directing patients to the needed specialist curative and other services, they can, in a similar fashion, direct older patients (e.g., with the use of special screening tests) to services provided at the Health Centres 75+. This could be supported by appropriate adaptations of the specialisation training in family medicine and is seen as a potential means to counter the existing shortages of geriatric staff [11].

The pilot of the Mental Health Centres, which has been implemented since mid-2018 [39], can be seen as an inspiration for the implementation of Health Centres 75+: both geriatric and mental health care suffer from similar problems (relatively low numbers of health professionals, low financing) and require much investment; both Health Centres 75+ and Mental Health Centres involve cooperation with PHC, specialist health services, and social care—the former could thus learn from the experiences of the latter.

Although the initial lack of support from the Ministry of Health has brought the policy proposal to an impasse, the Office of the President and the Ministry of Health are now considering joining forces to overcome it and to rework the policy idea into a joint proposal. This may give it a real chance of being implemented and provide a major opportunity for the development of comprehensive care for older people in Poland.

5. Conclusions

Geriatric care in Poland has found itself in a vicious circle for many years: it has suffered from chronic shortages of geriatric beds and specialists but, at the same time, the numbers of training places and job vacancies have been very low, discouraging medical students from entering the profession and not motivating further investment in geriatric infrastructure. Although the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that work on the draft law on Health Centres 75+ was suspended, the pandemic has drawn more attention to the health and social needs of older people in Poland, offering a window of opportunity to resume the debate about improving provision of services for this population group. The proposed draft seeks to create a community model of care for older people to allow them to live independently for as long as possible and receive the comprehensive, coordinated services they need. Although the proposal has some drawbacks, population ageing and the current lack of geriatric resources make it an important initiative that is worth putting back on the policy agenda and giving it a prominent place in the post-pandemic recovery plans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and formal analysis, A.S., M.G.-S., P.C. and I.K.-B. Resources and writing, A.S., K.B.-M. and N.P.; supervision, P.C. and I.K.-B. Revisions: A.S. and A.F.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to the acknowledge the invaluable work of Ewa Marcinowska-Suchowierska of the Medical Centre of Postgraduate Education in Warsaw, Marek Balicki from the Polish Ministry of Health, and Dorota Wijata from the Office of the National Development Council at the Chancellery of the President of the Republic of Poland, who contributed to the development of the concept of Health Centres 75+ described in this Perspective piece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Geriatric healthcare resources in selected European countries, 2009. (a) Geriatric specialists per 10,000 people aged 65+. (b) Geriatric beds per 10,000 people aged 65+. Source: [40].

Figure A2.

Geriatric healthcare resources in Poland by region, 2019. Note: The number of geriatric specialists shows professionally active geriatricians at the end of 2017 [23]. Source: [41].

References

- EC. Eurostat [Online Database]. Proportion of Population Aged 65 and over [TPS00028]; European Commission: Luxemburg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Population Structure and Ageing. European Commission, Eurostat. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Population_structure_and_ageing (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- EC. The 2021 Ageing Report. Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070); European Commission: Luxemburg, 7 May 2021; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/ip148_en.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- EC. Eurostat [Online Database]. Population on 1st January by Age, Sex and Type of Projection [PROJ_19NP]; European Commission: Luxemburg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neil, D.O.; Hastie, I.; Williams, B. Developing specialist healthcare for older people: A challenge for the European Union. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2004, 8, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Divo, M.J.; Martinez, C.H.; Mannino, D.M. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. Oct. 2014, 44, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kane, R.L.; Ouslander, J.G.; Resnick, B.; Malone, M.L. Essentials of Clinical Geriatrics; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duque, S.; Giaccardi, E.; van der Cammen, T.J.M. Integrated care for older patients: Geriatrics. In Handbook Integrated Care; Amelung, V., Stein, V., Goodwin, N., Balicer, R., Nolte, E., Suter, E., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NIK. Funkcjonowanie Medycznej Opieki Geriatrycznej [Functioning of Medical Geriatric Care]; Najwyższa Izba Kontroli [Supreme Audit Office]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,25632,vp,28405.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- EC. Eurostat [Online Database]. Self-Perceived Health by Sex, Age and Income Quintile [hlth_silc_10]; European Commission: Luxemburg, 2022; Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=hlth_silc_10 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Grzela, E. Konferencja “Polityka Lekowa”. Pora Zerwać z Systemową Stygmatyzacją Geriatrii [“Pharmaceutical Policy” Conference. It’s Time to Break with the Systemic Stigmatisation of Geriatrics]; Pulsmedycyny.pl: (Online), 21 November 2020; Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/konferencja-polityka-lekowa-focus-na-seniorow-1101715 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- MZ. Zdrowa Przyszłość Zdrowa Ramy Strategiczne Rozwoju Systemu Ochrony Zdrowia na Lata 2021–2027, z Perspektywą do 2030 r. [Healthy Future. Strategic Framework for the Development of the Health Care System for the Years 2021–2027, with a Perspective Until 2030]; Ministerstwo Zdrowia [Ministry of Health]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/zdrowie/zdrowa-przyszlosc-ramy-strategiczne-rozwoju-systemu-ochrony-zdrowia-na-lata-2021-2027-z-perspektywa-do-2030 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- EC. Eurostat [Online Database]. Severity of Bodily Pain by Sex, Age and Level of Activity Limitation [hlth_ehis_pn1d]; European Commission: Luxemburg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fedyk-Łukasik, M. Całościowa Ocena Geriatryczna w Codziennej Praktyce Geriatrycznej i Opiekuńczej [Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Everyday Geriatric Practice]. Geriatria i Opieka Długoterminowa [Geriatrics and Long-Term Care] 1/2015 (1). Available online: https://www.mp.pl/geriatria/wytyczne/131424,calosciowa-ocena-geriatryczna-w-codziennej-praktyce-geriatrycznej-i-opiekunczej (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Stuck, A.E.; Siu, A.L.; Wieland, G.D.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; Adams, J. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet 1993, 342, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechel, B.; Doyle, Y.; Grundy, E.; McKee, M. How Can Health Systems Respond to Population Ageing? Policy Brief 10. World Health Organization, on Behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2009. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/64966/E92560.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Bień, B.; Błędowski, P.; Broczek, K. Standardy postępowania w opiece geriatrycznej, Stanowisko Polskiego Towarzystwa Gerontologicznego opracowane przez Ekspertów Zespołu ds. Gerontologii przy Ministrze Zdrowia [Standards of conduct in geriatric care, Position of the Polish Gerontological Society developed by the experts of the Gerontology Team at the Ministry of Health]. Gerontol. Pol. [Pol. Gerontol.] 2013, 21, 33–37. Available online: https://gerontologia.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2013-02-1.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- NIK. Opieka Medyczna nad Osobami w Wieku Podeszłym [Medical Care for Older People]; Najwyższa Izba Kontroli [Supreme Audit Office]: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,8319,vp,10379.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Lundqvist, M.; Alwin, J.; Henriksson, M.; Husberg, M.; Carlsson, P.; Ekdahl, A.W. Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive geriatric assessment at an ambulatory geriatric unit based on the AGe-FIT trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zingmark, M.; Norström, F.; Lindholm, L.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Gustafsson, S. Modelling long-term cost-effectiveness of health promotion for community-dwelling older people. Eur. J. Ageing 2019, 16, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wojtyniak, B.; Goryński, P. (Eds.) Sytuacja Zdrowotna Polski i Jej Uwarunkowania, 2020 [The Health Situation in Poland and Its Determinants, 2020]; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego-Państwowy Zakład Higieny [National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene]: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: http://bazawiedzy.pzh.gov.pl/wydawnictwa (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- MZ. Mapa Potrzeb Zdrowotnych na Okres od 1 Stycznia 2022 r. do 31 Grudnia 2026 r. [Map of Health Needs for the Period from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2026]; Ministerstwo Zdrowia [Ministry of Health]: Warsaw, Poland. Available online: http://dziennikmz.mz.gov.pl/DUM_MZ/2021/69/oryginal/akt.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Kostka, T. Opieka Geriatyczna w Polsce [Geriatric Care in Poland]. In Proceedings of the Conference “Cenrum Zdrowia 75+. Zdążyć Przed Demograficznym Tsunami”. [Health Centre 75+. To Make it before the Pandemic], Warsaw, Poland, 10 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowska, E. Sieć Zniosła Geriatrię na Mieliznę [The Network Has Grounded Geriatrics]; Sluzbazdrowia.com.pl: (Online), 11 October 2018; Available online: https://www.sluzbazdrowia.com.pl/artykul.php?numer_wydania=4778&art=15 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- MZ. Krajowy Plan Transformacji na Lata 2022–2026 [National Transformation Plan for 2022–2026]; Ministerstwo Zdrowia [Ministry of Health]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: http://dziennikmz.mz.gov.pl/legalact/2021/80/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- MZ. Obwieszczenie Ministra Zdrowia z Dnia 27 Sierpnia 2021 r. w Sprawie Mapy Potrzeb Zdrowotnych [Notice of the Minister of Health of 27 August 2021 on the Health Needs Map]; Ministerstwo Zdrowia [Ministry of Health]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: http://dziennikmz.mz.gov.pl/DUM_MZ/2021/69/akt.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Sowada, C.; Sagan, A.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Badora-Musiał, K.; Bochenek, T.; Domagała, A.; Dubas-Jakóbczyk, K.; Kocot, E.; Mrożek-Gąsiorowska, M.; Sitko, S.; et al. Poland: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2019, 21, 1–235. Available online: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/poland-health-system-review-2019 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Szatur-Jaworska, B.; Rysz-Kowalczyk, B.; Imiołczyk, B. Sytuacja Osób Starszych w Polsce—Wyzwania i Rekomendacje [Situation of Older People in POLAND—Challenges and Recommendations]; Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich, Komisja Ekspertów ds. Osób Starszych [Civil Rights Ombudsman, Expert Commission on Older People]: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. Available online: https://bip.brpo.gov.pl/sites/default/files/Sytuacja-osob-starszych-w-Polsce.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Bany-Moskal, P.; Chmielewski, M.; Demkow, U.; Duda, P.; Kardas, G.; Leźnicka, M.; Merks, P.; Pakulski, C.; Simka, M.; Sześciło, D.; et al. Geriatria, Opieka Długoterminowa, Opieka Paliatywna [Geriatrics, Long-Term Care, Palliative Care]; Instytut Strategie 2050: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; Available online: https://strategie2050.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Geriatria.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- NFZ. Zarządzenie Nr 160/2021/DSOZ Prezesa Narodowego Funduszu Zdrowia z Dnia 30.09.2021 r. w Sprawie Warunków Zawarcia i Realizacji Umów o Udzielanie Świadczeń Opieki Zdrowotnej w Zakresie Podstawowej Opieki Zdrowotnej [Regulation No. 160/2021/DSOZ of the President of the National Health Fund of 30/09/2021 on the Conditions for the Conclusion and Implementation of Contracts for the Provision of Healthcare Services in the Field of Primary Healthcare]; Narowowy Fundusz Zdrowia [National Health Fund]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.nfz.gov.pl/zarzadzenia-prezesa/zarzadzenia-prezesa-nfz/zarzadzenie-nr-1602021dsoz,7420.html (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Prezydent.pl. Konferencja “Centrum Zdrowia 75+” [Conference „Health Centre 75+]; Prezydent.pl: (Online), 10 September 2019; Available online: https://www.prezydent.pl/aktualnosci/wydarzenia/prezydent-na-konferencji-centrum-zdrowia-75,1500 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Grzela, E. Co Dalej z Centrami Zdrowia 75+? [What Next with Health Centres 75+?]; Pulsmedycyny.pl: (Online), 22 May 2020; Available online: https://pulsmedycyny.pl/co-dalej-z-centrami-zdrowia-75-plus-991871 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Jakubiak, K. Największym Problemem Pacjentów Jest Dostępność Świadczeń [The Biggest Challenge for the Patients is Access to Services]; mZdrowie.pl: (Online), 5 May 2021; Available online: https://www.mzdrowie.pl/eksperci/najwiekszym-problemem-pacjentow-jest-dostepnosc-swiadczen/ (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- KLRWP. Centrum Zdrowia 75+ [Health Centre 75+]. Kolegium Lekarzy Rodzinnych w Polsce [College of Family Physicians in Poland]; Klrwp.pl: (Online), 15 September 2019; Available online: https://klrwp.pl/aktualnosci/wpis/757/2019-09-15/centrum-zdrowia-75/pl (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- GUS. Zdrowie i Ochrona Zdrowia w 2019 r. [Health and Health Care in 2019]; Główny Urząd Statystyczny [Chief Statistical Office]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/zdrowie/zdrowie/zdrowie-i-ochrona-zdrowia-w-2019-roku,1,10.html (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- KRRIO. Sprawozdanie z Działalności Regionalnych Izb Obrachunkowych i Wykonania Budżetu Przez Jednostki Samorządu Terytorialnego w 2020 Roku [Report on the Activities of Regional Accounting Chambers and Budget Implementation by the Local Self-Government Units in 2020]; Krajowa Rada Regionalnych Izb Obrachunkowych [Regional Council of the Regional Accounting Chambers]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://rio.gov.pl/download/attachment/96/sprawozdanie_za_2020_r.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Frączkiewicz-Wronka, A.; Kowalska-Bobko, I.; Sagan, A.; Wronka-Pośpiech, M. The growing role of seniors councils in health policy-making for older people in Poland. Health Policy 2019, 123, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błędowski, P. Zmiany w politykach, w tym zdrowotnej i społecznej, wobec starzenia w Polsce i Europie w ostatniej dekadzie. In Badanie Poszczególnych Obszarów Stanu Zdrowia Osób Starszych, w Tym Jakości Życia Związanej ze Zdrowiem; Błędowski, P., Tomasz Grodzicki, T., Mossakowska, M., Zdrojewski, T., Eds.; Gdański Uniwersytet Medyczny: Gdańsk, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MZ. Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z Dnia 27 Kwietnia 2018 r. w Sprawie Programu Pilotażowego w Centrach Zdrowia Psychicznego [Regulation of the Minister of Health of 27 April 2018 on a Pilot Programme in Mental Health Centres]; Ministerstwo Zdrowia [Ministry of Health]: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; Dz.U. 2018 poz. 852. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20180000852/O/D20180852.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Kropinska, S.; Wieczorowska-Tobs, K. Opieka geriatryczna w wybranych krajach Europy [Geriatric care in selected European Countries]. Geriatria [Geriatrics] 2009, 3, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Sytuacja Osób Starszych w Polsce w 2019 Roku [Situation of Older People in Poland in 2019]; Główny Urząd Statystyczny [Chief Statistical Office]: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/osoby-starsze/osoby-starsze/sytuacja-osob-starszych-w-polsce-w-2019-roku,2,2.html (accessed on 16 January 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).