Abstract

Experiential learning is the process where learners create meaning from direct experience. This systematic review aimed to examine the effects of experiential learning activities on dietary outcomes (knowledge, attitudes, behaviors) in children. Four databases: Education Research Complete, Scopus, Web of Science and PsychINFO were searched from database inception to 2020. Eligible studies included children 0–12 years, assessed effect of experiential learning on outcomes of interest compared to non-experiential learning and were open to any setting. The quality of studies was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool by two independent reviewers and effect size was calculated on each outcome. Nineteen studies were conducted in primary school, six in pre-school and one in an outside-of-school setting and used nine types of experiential learning strategies. Cooking, taste-testing, games, role-playing, and gardening were effective in improving nutrition outcomes in primary school children. Sensory evaluation, games, creative arts, and storybooks were effective for preschool children. Multiple strategies involving parents, and short/intense strategies are useful for intervention success. Experiential learning is a useful strategy to improve children’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards healthy eating. Fewer studies in pre-school and outside of school settings and high risk of bias may limit the generalizability and strength of the findings.

Keywords:

healthy eating; nutrition; children; preschool; primary school; intervention; systematic review 1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity among children is a global public health concern [1,2]. Excess weight in childhood is associated with an increased risk of developing physical, social, and psychological conditions, overweight and obesity and earlier onset of non-communicable diseases [3,4], such as diabetes [5] and cardiovascular disease [6]. Healthy eating is essential in the early years of life (0–12 years) to ensure optimal growth and development, as well as reducing the risks of life-long health problems [7]. Data from several surveys of fruit and vegetable intake of children conducted globally [8,9,10], ref. [11] have reported low intakes of fruit and vegetables in children of between two to three portions compared to the recommended five portions per day [12]. Given children’s low adherence to nutrition recommendations, interventions that target nutritional knowledge, attitudes and dietary behaviors are needed. Nutrition-related knowledge [13], attitudes [14] and eating behaviors [15,16] learned in childhood have been shown to track into later years; therefore, it is imperative to establish healthy eating behaviors early in life [17]. The World Cancer Research Fund’s Nourishing Framework has provided a repository of global policy actions that promote healthy diets and reduce obesity and identifies behavior change communication as a key policy area [18]. Experiential learning approaches such as gardening and cooking may be more engaging to children compared to more traditional learning approaches, in which children are more passive recipients of the information [19,20]. Positive behaviours, attitudes, and knowledge of healthy eating in children have been successfully demonstrated through using experiential learning approaches [21,22,23]. Experiential learning is beneficial because it exposes children to hands-on experiences and active engagement with activities promoting critical thinking [24]. Experiential learning-based approaches can be a useful strategy to improve children’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards healthy eating because they enable children to experiment, explore, play, and become familiar with materials and concepts that are related to the targeted behaviours [25,26].

In the case of improving children’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards healthy eating, experiential activities such as taste-testing, cooking, gardening, games, and role-play can actively involve children with hands-on experiences, engagement with activities and extend their thinking and curiosity [24,27,28,29]. It may be a particularly useful strategy for pre-school and community settings as these are ideal settings to develop personal understanding, knowledge, skills, and attitudes through active engagement and reflection on their experiences and activities.

Two previous reviews on primary schools have found experiential learning approaches to be effective in improving nutrition-related behaviors, knowledge, and attitudes in children. A systematic review by Dudley et al. [22] also found that school-based interventions that were inclusive of experiential learning strategies, such as cooking, preparing food or gardening were associated with the largest effects in increasing nutritional knowledge, preferences and consumption of fruit and vegetables and reducing energy intake in primary school children compared to interventions without experiential learning components. Another systematic review reported on characteristics of successful nutrition-related experiential learning interventions and found that cooking-related activities and gardening increased children’s willingness to taste unfamiliar foods (e.g., new fruits and vegetables) and increased nutritional knowledge in primary school children [30]. Both reviews provide important contributions to the field; however, these reviews did not include children below five years of age and only focused on the primary/elementary school setting. Additionally, because the review by Charlton and colleagues (2020) aimed to identify the key characteristics of successful nutrition-focused experiential learning interventions for children, only effective interventions were included. Consequently, unbiased estimates of intervention effects (i.e., by comparing effective and ineffective interventions that used the same approach) could not be provided. To extend the existing knowledge in this area, this systematic review aimed to examine the effects of experiential learning activities among a broader age range of children (0–12 years), and in a broader range of settings including both school/pre-school and community settings, to provide a more comprehensive assessment of experiential learning opportunities for children.

2. Methods

This review was registered with PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (no. CRD42018103629) and adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) statement for systematic reviews [31,32] to ensure transparent reporting.

2.1. Search Strategy

Four databases were searched for eligible studies: Education Research Complete, Scopus, Web of Science and Psych Info. Search terms used to obtain relevant studies were guided by the PICO approach: Population children between birth to age 12 years old (Children 0–12 years); Intervention (experiential learning activities); Comparison (no or non-experiential learning activity); Outcome behaviors i.e., food intake, knowledge, attitudes). Reference lists of included studies were also hand searched. The search terms are shown in the table below (Table 1). No limits were applied to the publication date and the search was conducted (“to obtain articles published from database inception to 2020”).

Table 1.

Search terms.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cluster/group RCTs (CRCTs) reported in original, peer-reviewed articles. Studies were excluded if they were not published in English, were non-experimental designs or were reviews or opinion articles and were not an outcome of interest. A post hoc protocol deviation was made to exclude non-randomized controlled trials and non-controlled trials because of the higher than anticipated number of RCTs and CRCTs identified. Only RCTs and CRCTs were included as these were deemed to be the most robust level of evidence. Eligible studies were identified using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Out-comes (PICO) framework.

Population: For the purpose of this review, children were defined as those aged between birth to age 12 years old (0–12 years). Studies were included if the mean age of participants was between 0–12 years and excluded if the mean age of participants was above 12 years at baseline of the intervention. This age range was selected for this review because children 0–5 years were not included in the previous reviews and children 0–5 and 5–12 years perhaps are more likely to have similar approaches of learning healthy eating while, due to differences in nutrition requirements and other environmental influences in older age/adolescents, distinct intervention strategies may be needed [33]. Intervention: Studies were included where the intervention was inclusive of an experiential learning activity, with one or more of the following characteristics: (1) children played a central role in the activity, allowing them to engage with and explore the phenomena; (2) the activity went beyond the provision of information, purely instruction, encouragement, equipment or change to the environment; (3) the activity required children’s input and children had to physically do something as part of the learning activity; (4) the children had a level of autonomy in completing some part of the activity that required them to be creative, problem-solve, be reflective; (5) the activity invoked the children’s thoughts as well as a sense of taste, touch, smell, feel; (6) the activities were specifically designed to have a learning experience that enhanced healthy eating measured post-intervention; (7) the activities had a clear learning task or skill as the outcome; (8) the children had direct exposure to the phenomena being studied; (9) the activity was coordinated/ facilitated by a leader such as a teacher or an educator, farmer, or parent; and (10) the facilitator(s) provided the structure for the activity such as basic instruction, posing questions to invoke problem-solving, creative thinking or reflection. The study was excluded if there was no experiential activity for children as part of the intervention. Setting: Studies were included from all settings (e.g., school, after school programs, preschools/early childhood education and care centers, farms, and school canteens) and there was no exclusion based on the study setting. Outcome: a study was included if it had at least one outcome related to food or nutrition behavior, attitudes, or knowledge. A post hoc protocol deviation was made to exclude studies where the outcome was physical activity because of the higher than anticipated number of studies identified. Studies investigating effects on physical activity outcomes will be reported in a separate review.

2.3. Study Selection

Study records were imported into EndNote reference software version X9 (Clarivate Analytics, London, UK). Duplicate studies were removed, and two reviewers (M.L.H. and G.N.) independently screened the titles and abstracts. All studies included by at least one reviewer were then assessed for inclusion by the two reviewers (M.L.H. and G.N.) at the full-text stage. Where discrepancies of inclusion/exclusion existed, discussions were conducted between the reviewers to reach a consensus.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data for the included studies were extracted using a standardized data extraction table (Table 2) devised by one reviewer (S.D.V.) and discussed with the author group. The information collected included study authors/year of publication, country of study, study design, theoretical framework used, study sample (size, age of participants), intervention (duration, experiential-based learning activities, outcome measures/tools) and results. A second reviewer (D.P.C.) verified the information extracted to reduce error and bias.

Table 2.

Experiential learning interventions and healthy eating outcomes in children.

2.5. Risk of Bias Appraisal

To assess the potential risk of bias of included studies, the revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) [34] was independently completed by two reviewers (S.D.V. and Z.Z.), with two additional reviewers (R.A.J. and D.P.C.) consulted if consensus could not be reached. This tool examines five domains: the randomization process; deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention or effect of adhering to intervention); missing outcome data; measurement of the outcome; and selection of the reported results. We used the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) criteria for overall risk-of-bias judgement [35]. The overall risk-of-bias was judged using the following criteria: (1) low risk of bias—the study was judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains for this result,(2) some concerns—the study is judged to raise some concerns in at least one domain for this result, but not to be at high risk of bias for any domain (3) high risk of bias—the study was judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain for this result or the study is judged to have some concerns for multiple domains in a way that substantially lowers confidence in the result [35].

2.6. Data Synthesis and Analysis

To enable comparison between studies and estimate the relative magnitude of the effect of the interventions, effect sizes for the difference between the intervention and control groups on each outcome measure (increased intake of fruits and vegetables/decreased consumption of unhealthy foods, increased preference for healthy foods/decreased preference for unhealthy foods, and increased nutritional knowledge) were calculated, regardless of their statistical significance. Firstly, the pooled SD was calculated by using the following equation from Cohen [36]:

where: SD1 is the standard deviation of the intervention group, SD2 is the standard deviation of control group 2, n1 is the size of the intervention group and n2 is the size of the control group. The mean difference between the intervention and control groups was divided by the standard deviation (SD) for both groups (pooled standard deviation SD). Effect sizes were then calculated using the Cohen’s d formula: d = (M1—M2)/SD pooled [37], where M1 is the mean of the intervention group, M2 is the mean of the control group and SDp is the pooled standard deviation for both groups.

Finally, the studies were divided into two categories according to the age of the intervention participants; that is, pre-school and primary school and mean effect size was then calculated for each study by dividing the sum of all effect sizes by the number of effect sizes (for healthy/unhealthy foods separately) for behavior, attitude, and knowledge outcomes. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (<0.2), medium (0.2–0.8), and large (>0.8) [36].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

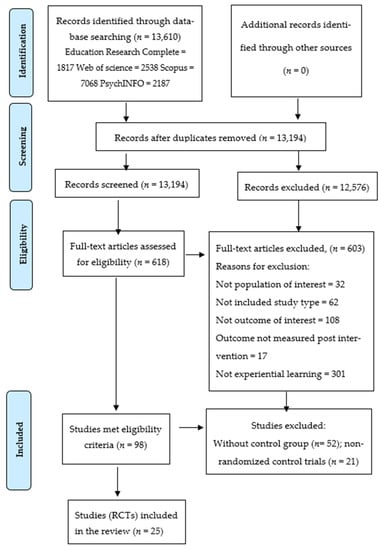

Ninety-eight studies described healthy eating-related outcomes in children. Of these, 52 studies did not have a control group and 21 studies were non-randomized controlled trials, thus were excluded. In total, 25 eligible studies were included in the final review, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process. (PRISMA flow diagram [32]).

3.2. Study and Intervention Characteristics

The characteristics of the studies and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Of the 25 included studies, nine were RCTs and 17 were CRCTs. Six studies involved children aged 0–five years and 19 studies involved children aged six–12 years. Most of the included studies (16/25) were conducted in the United States, with the remainder in England (n = 1), Spain (n = 2), Norway (n = 2), Belgium (n = 1), Lebanon (n = 1), Nepal (n = 1) and Bhutan (n = 1). A number of studies were underpinned by a number of different theoretical frameworks including Social Cognitive Theory (n = 8, [45,47,48,49,50,53,54,61]), Social Learning Theory (n = 1, [44]), Intervention Mapping Protocol (n = 1, [38]) Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory (n = 1, [43]), Chronic Care Model (n = 1, [41]) and Social-Ecological Model (n = 1, [51]). Though nearly half of the studies (12/25) did not report the use of any theoretical model in the intervention development [39,40,42,46,52,55,56,57,58,59,60,62].

The majority (18/25) of studies were conducted in the primary school setting [44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62], six in pre-school settings [38,39,40,41,42,43] and one in a non-school or education setting, namely scout camps [49]. Nearly three-quarters of the studies (16/25) had a high risk of bias. Eight studies were graded as having ‘some concerns’ [39,49,50,52,56,57,60,62] while only one study was rated as having a low risk of bias [42]. Overall, the included intervention studies had low methodological quality due to three of the domains consistently being rated low quality for most of the included studies, which may impact the validity of the results. The assessment domains that consistently were rated as low quality included missing outcome data, risk of bias in the measurement of the outcome and risk of bias in the selection of the reported result (see Supplementary Table S1). Of the 25 studies, nine [39,40,43,45,47,48,51,58,61] studies involved parents directly in the intervention activities with children. Of the nine studies that directly involved parents, three were conducted in the preschool setting.

3.3. Experiential Learning Activities

Nine types of experiential learning activities were used across the 25 studies, which included: (1) Taste-testing (i.e., children tasting food products (n = 19)); (2) Games (i.e., guessing food, food labelling competitions, card/board games, fun play, mystery bag (n = 8)); (3) Creative/art activities (i.e., coloring, drawing, collage, portraits, art and craft on fruits and vegetables, fruit and vegetable charts, posters/pamphlets (n = 10)); (4) Storybooks (i.e., making food-related stories (characters) (n = 6)); (5) Shopping list development and food purchasing (i.e., creating a shopping list, selecting food/meals, simulated shopping and food classifications, imaginary trips to supermarket and gardens (n = 7)); (6) Food preparation and cooking/preparing foods, fruit and vegetables, snacks and other foods/meals (n = 7)); (7) Calculations/recording (i.e., sugar and fat, veggie math, three-day fruit and vegetable intake, the personal food pyramid and other math activities with food (n = 5)); (8) Sensory evaluation (i.e., smell, feel, sight and sound of foods (n = 4)); and (9) Gardening (i.e., planting and harvesting of fruits or vegetables (n = 2)) (see Supplementary Table S2).

The types of activities used in interventions with preschool-aged children (in early childhood education and care settings) and with primary school-aged children (in primary schools and community settings) were mostly similar, although activities used in early years education and care settings were targeted to earlier developmental stages using sensory play, storybooks, songs, and creative art activities. Of the six studies with preschool children, four studies focused entirely on experiential learning activities [38,40,42,43] while two studies [39,41] combined experiential activities with nutrition education lessons (i.e., a theory-based component). Of the 19 studies conducted with primary school-aged children, seven studies focused entirely on experiential learning activities [45,46,47,49,56,57,62] while 12 studies combined experiential activities with nutrition education [44,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,58,59,60,61].

3.4. Intervention Effects

The effect sizes of the intervention (experiential learning activities) on the outcomes; behavior, attitudes, and knowledge (healthy foods and unhealthy foods) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Experiential learning activities and effect sizes on outcomes (Healthy foods and unhealthy foods).

Table 3 highlights the experiential learning activities and effect sizes on outcomes which were grouped as healthy foods and unhealthy foods. (Healthy foods/ Unhealthy foods = see Table 2).

In preschool-aged children, five studies [38,40,42,43] measured behavior change. Two of these [42,43] reported small effects for healthy foods (increasing fruit and vegetable consumption), with both involving sensory evaluations such as feeling/touching fruits and vegetables, or food drawing and coloring activities and games and [43] involved parents in the intervention activities. Only one study in this age group measured changes to children’s attitudes towards healthy foods [42]. This study reported a statistically significant but small mean effect (Md = 0.23) on changing preschool children’s preferences for, and self-efficacy and willingness to taste, unfamiliar fruits and vegetables. This intervention used multiple experiential learning activities including taste-testing, sensory evaluation, games, storybooks, and creative/art activities. One study measured change in nutrition-related knowledge [39] but effect sizes could not be calculated due to missing data.

In primary school-aged children, sixteen studies [44,45,46,47,49,50,51,53,54,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] measured food-related behavior change. Effect sizes were able to be calculated for eight studies in which the duration of intervention lasted between two and eighteen months [47,48,51,52,53,54,57,58]. Two of these [47,61] had large, significant mean effects (Md = 1.0) in relation to healthy foods (fruits and vegetable intake). Multiple combinations of experiential learning activities were reported by these studies, including games, role-playing food preparation/cooking, school gardens, and taste-testing. Two of the studies [47,61] with high effects on increasing intake of healthy foods had involved parents directly in the intervention activities. One study [61] also combined experiential learning activities with nutrition education classroom lessons. Three additional studies [56,59,62] reported medium effects (Md = 0.4). One of these studies [59] was moderately effective in increasing the consumption of healthy foods (fruits and vegetables) through school gardening and taste-testing over one school year however they also included nutrition education lessons. The other two studies [56,62] were moderately effective in reducing consumption of unhealthy foods and used a range of experiential learning activities such as food preparation/cooking, taste-testing, games, creative art activities, sensory evaluation [62] and one study additionally used simulated food purchasing [56].

The remaining seven studies [48,49,51,53,54,57,58] had small (Md = 0.2) but significant effects for increasing consumption of healthy foods (fruits and vegetables) [48,57,58] or reducing consumption of unhealthy foods such as sugar-sweetened beverages [49] chips and sugar-sweetened drinks [54], sweet snacks, fast foods [53] or intakes of sodium, sugar, and total calories [51]. Six [48,49,51,53,54,57] of the seven studies used a range of experiential learning activities, such as food preparation/cooking, taste-testing, games, songs, creative/art activities, storybooks and, role-playing, while one [58] focused only on gardening. Most of these studies (5/8) [48,49,51,53,54] combined experiential learning with nutrition education lessons. Half of these studies (4/8) [48,49,54,57] had an intervention duration between three to six months, while three studies [51,53,58] had a duration ranging between one to two years.

Eight studies [47,49,52,54,56,57,58,62] conducted with primary school-aged children measured changes in children’s attitudes towards healthy eating, such as self-efficacy and willingness to try new foods. One of these studies [58], involving a two-year school-based gardening program, had a large significant effect (d = 1.12) on increasing attitudes related to healthy eating (preferences and self-efficacy for choosing fruits and vegetables). Three studies [47,49,54] had a medium significant effect (Md = 0.7) on improving attitudes towards healthy and unhealthy foods. All studies that reported large or medium effects used a range of experiential learning activities including food preparation, taste-testing, games, role-plays, and storybooks. The duration of these interventions was between two to four months. One study [49] was conducted in a scout camp setting, another [47] included home-based activities, and one [54] included nutrition education lessons in a school classroom. The remaining four studies [52,56,57,62] had small effects (Md = 0.29) on changing preferences and self-efficacy for healthy foods, including choosing/liking of fruits [57], fruits and vegetables [52,62], and willingness to choose unfamiliar fruits and vegetables [62]. All four studies used a variety of experiential learning activities, such as simulated food purchasing, food preparation, taste-testing, games, storybooks, and creative/art activities. These studies were of short duration, ranging from single sessions to a period of four months. Two studies [54,58] combined nutrition education classroom lessons with experiential learning activities.

Ten studies [39,47,48,51,52,53,54,55,57,58] measured change in primary school-aged children’s knowledge regarding food, nutrition or healthy eating. Of the eight studies for which effect sizes could be calculated [47,48,51,52,53,54,57,58], four [52,53,54,58] had a large effect (Md = 1.1) and reported significant effects on increasing knowledge about healthy eating (nutrition, fruits, and vegetables). Of these four studies, three [52,53,54] used a range of experiential learning activities, such as food preparation, taste-testing and games combined with nutrition education lessons. One of the studies [58] included only gardening. Two of these studies were conducted over one to two months [52,53,54], while two took place over one to two years [47,59]. The remaining four studies [47,48,51,57] had a small effect (Md = 0.01) on increasing children’s knowledge of healthy foods and these studies used a range of experiential learning activities, such as food preparation/cooking, taste-testing, games, songs, creative/art activities, storybooks, and role-playing. Three studies [48,51,57] combined nutrition education with experiential learning activities. The duration of the interventions ranged between two to six months [47,48,57] and two years [51].

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effectiveness of experiential learning interventions conducted in pre-schools, primary schools, and community settings for improving healthy eating related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour in children aged birth to 12 years. Interventions with pre-school aged children that applied strategies such as sensory evaluation activities, playing games, storybooks, role-modelling and creative art activities tended to have a large effect on food behaviours and attitudes. However, there were fewer studies conducted in preschool-aged children compared to older children and the effects were smaller, therefore less evidence of effective experiential learning approaches was found for this age group. Most of the included intervention studies were conducted in the primary school setting, and those that used strategies such as food preparation/cooking, taste-testing, games, role-playing, and gardening, had the greatest effect across the three outcomes (behaviour, attitude, and knowledge) in this age group. There was only one study conducted in a community setting (i.e., a scout’s camp) and it reported a small intervention effect.

The majority of the included studies had used a combination of experiential learning approaches; therefore, the impact of individual experiential learning approaches could not be established. However, a few approaches showed promise and were typically used across the most effective studies. For instance, gardening showed a large effect across the three outcomes (increasing knowledge, preferences and consumption of fruits and vegetables) in studies among primary school-aged children [53,58]. The exception was one study [59] which reported a very low effect due to the reported small study sample. Our findings on the effectiveness of gardening strategy are consistent with other studies among primary school children [63,64], however, these studies had compared an active comparison group with gardening (teacher-led versus expert-led gardening) instead of a control group.

Taste-testing was also commonly used in studies across both age groups and demonstrated a large effect on behavioral outcomes [42,61] however, it was often applied together with sensory evaluation, food preparation, cooking and/or gardening. The exceptions were two studies that had included taste-testing in their intervention and reported a small effect [38,43]. However, these two studies had (1) a lower intervention intensity (six weekly group educational sessions), (2) a low adherence by the intervention group, (3) combined nutrition education with the experiential learning activities, and (4) a smaller sample size (e.g., <100). Previous studies that investigated the effectiveness of taste-testing in primary school curriculum have recommended using experiential learning approaches for desired outcomes [65]. A recent scoping review that examined children’s involvement in meal preparation and the associated nutrition outcomes also found that hands-on meal preparation can instil positive perceptions towards nutrition/healthy foods, and potentially improve children’s diet [66]. Hence our finding is consistent with the existing literature.

Creative art activities such as coloring, drawing, making a collage using food pictures, portraits, art and craftwork and charts on fruit and vegetables, making posters and pamphlets were also utilized consistently in studies with large effect sizes across the age groups and outcomes. These activities were effective when used in combination with other strategies such as cooking and taste-testing. Art and craft activities linking colors (rainbow) with fruit and vegetables possibly broadened children’s knowledge and awareness of eating a variety of fruits and vegetables [67]. However, there is a lack of existing supporting evidence on this potential influence.

In relation to children’s dietary behavior changes, studies that focused on both healthy and unhealthy foods were effective. However, for changing attitudes and knowledge, interventions that focused on providing positive messages related to increased consumption of healthy foods tended to be more effective than those that focused on discouraging unhealthy foods. Furthermore, studies in primary school children with medium to large effects reported using used Social Cognitive Theory SCT in their intervention development [47,53,61]. However, these studies did not specify how the concepts of SCT concepts were incorporated. These interventions may have been effective because SCT explains how children can acquire and maintain behaviour patterns and that behavior, personal and environmental factors interact to describe and predict behaviour change in a reciprocal way [68]. Self-efficacy, outcome expectation, skill mastery and self-regulation are the key concepts of social cognitive theory that can be used to explain and predict behaviour changes [69] Furthermore, knowledge gained through direct involvement in experience is integral to experiential learning [27]. This central idea is found in a range of theories and outlines surrounding experiential learning.

The studies with a short-term intervention duration (up to twelve weeks) for preschool-aged children were also more effective compared to those of longer duration (up to six months) for demonstrated behavior change. However, these studies did not report any follow-up assessments thus it is unclear whether the effects were only short-term or if longer-lasting benefits were produced. The exception was one study [47] that conducted a follow-up assessment eight months after the intervention and reported that effects were maintained.

Regarding the interventions with preschool-aged children, the strategies that seemed more suitable to their developmental stages were effective. The two most promising programs included a study by Dazeley et al. [42] which used sensory evaluation activities (use of senses), especially with fruits and vegetables and reported a large effect. The other study was by Jisoo et al. [43], which focused on storybooks (with visuals) and involved parents completing activities with their children. Younger children perhaps acquire their food preferences by direct contact with foods through sensory experiences such as tasting, feeling, seeing, and smelling foods [70] which might explain why this strategy is effective for this age group. Our finding is similar to recent research [71] which also showed positive results from the exposure to pictures of foods in toddlers.

In contrast, it was also evident that some of the intervention studies that reported smaller effects also used similar experiential learning approaches to those of more effective studies. However, a range of other possible factors, beyond the intervention strategies, may have influenced their relative impact. For example, these studies tended to use child reports of eating behaviors, did not use validated tools to measure behavior, had extended durations but with lower intensity of intervention strategies (e.g., infrequent intervention sessions), and combined experiential learning activities with more didactic classroom sessions.

The relative effectiveness of school-based experiential learning approaches to promote healthy eating in children compared to nutrition education alone was supported in an earlier systematic review and meta-analysis by Dudley et al. [22] They examined the teaching strategies of 49 interventions that reported on healthy eating outcomes for primary school children and found that experiential learning strategies had the largest effects across all outcomes. However, that review did not focus on the effectiveness of different types of experiential learning activities and only included studies conducted in the primary school setting. Similarly, another review by Charlton et al. [30] that focused on school-based experiential learning and nutrition education interventions among primary school children found that interventions that included multiple or a combination of experiential learning strategies increased children’s preferences for, knowledge of, and consumption of healthier foods. Both the earlier reviews included quasi-experimental study designs as well. Our findings extend these reviews by examining only RCT interventions and including pre-school and community settings.

4.2. Implications for Interventions

This review suggests that the experiential learning interventions may be more successful to the extent that they (a) include multiple or a combination of experiential learning strategies in the intervention, indicating that the more diverse the intervention, the more likely it was to be successful, (b) involve parents in the intervention activities, such as models in cooking and gardening which may create awareness, reinforce knowledge gained and encourage healthy behaviours [72], (c) make strategies fun, interesting, realistic, and more engaging for children, which demonstrates the importance of experiential learning (hands-on activities) as they involve processes where the learners actively experience activities, attempt to conceptualize what is observed, and reflect on those experiences [27], (d) are grounded on an effective behaviour change theory such social cognitive theory, (e) are focused on specific and targeted food behaviours for improvement such as “choose vegetables as snacks”.

4.3. Implications for Future Research

Based on this review there are recommendations for future research in this area. There are fewer experiential learning healthy eating interventions conducted in pre-school and community settings compared to primary school, thus more studies are needed in these settings. Most of the studies were overall rated as having low methodological quality due to the following factors being consistently rated as low quality: missing outcome data, risk of bias in the measurement of the outcome and risk of bias in the selection of the reported results. Future researchers could focus on addressing these limitations to enhance the quality of the evidence. Our review supports the need for more among preschool-aged children and for settings beyond primary schools, such as communities. Furthermore, most of the included studies did not report the use of any theoretical model in the intervention development, thus it is recommended that future interventions are built on a behavioural theory. For effectiveness, future studies should consider conducting follow-up assessments to understand if intervention effects are maintained. Development of short and intense interventions that are better suited for the specific settings.

4.4. Implications for Policy

For primary school-based experiential learning interventions, to deliver our recommendations to policymakers, factors such as cost, context, dose-response, and sustainability of the intervention should be considered. Policymakers should also focus on specific school food environment policies that improve targeted dietary behaviours such as healthy eating [73].

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

The current review updates and extends the previous reviews and includes studies with a broader age group and interventions delivered outside of school settings. We used broad search terms and a comprehensive inclusion criterion, which yielded many eligible studies which were independently screened by two reviewers. Only RCT and CRCT studies with experiential learning interventions were included, which enhances the internal validity of the review. We calculated effect sizes (Cohen’s d) to quantify the relative effect of the intervention strategies on the outcomes as well as the relative effect on healthy and unhealthy choices across age groups, which has not been done previously. We also assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration tool, which was important for highlighting methodological gaps in the evidence base.

There were a few limitations associated with this review. This review only included papers published in English, therefore we may have not included papers published in other languages. Our review only included RCTs and CRCTs, but not quasi-experimental studies, which would have strengthened the internal validity of our review. However, in relation to studies conducted in schools, it may not always be possible to randomize groups to intervention or control conditions (e.g., if schools were building gardens). Evidence from such studies with less robust designs may still provide useful information about the effectiveness of experiential learning interventions. We were not able to calculate effect sizes for some studies, despite best efforts to obtain further information from study investigators. Given that only one study was conducted outside of the school setting, there was a limited ability to identify effective experiential learning activities for other settings. Likewise, many of the interventions were conducted with school-aged children, rather than with younger age groups. The risk of bias assessments of the studies was generally high, therefore the strength of the conclusions from this review may need to be considered carefully. Lastly, this review is limited to the effects of experiential learning activities on healthy eating outcomes only, and therefore findings are not generalized to other lifestyle behaviours such as physical activity.

5. Conclusions

Experiential learning activities are a useful strategy to improve children’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors towards healthy eating. Strategies such as food preparation/cooking, taste testing, playing games, role-playing, and gardening were found to positively affect nutrition outcomes for primary school-aged children. For preschool-aged children, strategies such as sensory evaluation, taste-testing, interactive games, creative arts activities, and storybooks hold promise, but more research in this age group is needed. Key features of successful interventions included combining multiple strategies, involving parents, being grounded on a theoretical model and delivering shorter but more intense interventions. The findings of this review provide useful insight for future interventions that seek to apply experiential learning to the improvement of healthy eating in children.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph182010824/s1, Table S1: Quality assessment of the included studies, Table S2: Experiential learning strategies used by the included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., D.P.C. and R.A.J.; methodology, D.P.C., R.A.J., B.K., K.C. and S.D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D.V.; writing—review and editing, S.D.V., D.P.C., R.A.J., M.L.H., Z.Z., K.C., B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Grace Norton (GN) for her assistance in conducting the review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Cancer Control Indicators. Overweight and Obesity–Children and Young People. Available online: https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/prevention/overweight-and-obesity/overweight-and-obesity-children-and-young-people (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health: Childhood Overweight and Obesity. Available online: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/ (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- Kelly, A.S.; Barlow, S.E.; Rao, G.; Inge, T.H.; Hayman, L.L.; Steinberger, J.; Urbina, E.M.; Ewing, L.J.; Daniels, S.R. Severe obesity in children and adolescents: Identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 128, 1689–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Why Does Childhood Overweight and Obesity Matter? Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood_consequences/en/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Pulgaron, E.R.; Delamater, A.M. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: Epidemiology and treatment. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, M. Obesity and cardiovascular risk in children and adolescents. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Anzman, S.L. Learning to eat in an obesogenic environment: A developmental systems perspective on childhood obesity. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.; Kristjansdottir, A.G.; Te Velde, S.J.; Lien, N.; Roos, E.; Thorsdottir, I.; Krawinkel, M.; de Almeida, M.D.V.; Papadaki, A.; Ribic, C.H. Fruit and vegetable consumption in a sample of 11-year-old children in ten European countries–the PRO GREENS cross-sectional survey. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2436–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2011–2013. Available online: http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/734DF823586D5AD9CA257B8E0014A387/$File/national%20nutrition%20and%20physical%20activity%20survey%202011-12%20questionnaire.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Cockroft, J.; Durkin, M.; Masding, C.; Cade, J. Fruit and vegetable intakes in a sample of pre-school children participating in the ‘Five for All’project in Bradford. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yngve, A.; Wolf, A.; Poortvliet, E.; Elmadfa, I.; Brug, J.; Ehrenblad, B.; Franchini, B.; Haraldsdóttir, J.; Krølner, R.; Maes, L. Fruit and vegetable intake in a sample of 11-year-old children in 9 European countries: The Pro Children Cross-sectional Survey. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2005, 49, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Volume 916. [Google Scholar]

- Bannon, K.; Schwartz, M.B. Impact of nutrition messages on children’s food choice: Pilot study. Appetite 2006, 46, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkilä, V.; Räsänen, L.; Raitakari, O.; Pietinen, P.; Viikari, J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, V.; Escribano, J.; Closa-Monasterolo, R.; Zaragoza-Jordana, M.; Ferré, N.; Grote, V.; Koletzko, B.; Totzauer, M.; Verduci, E.; ReDionigi, A. Unhealthy dietary patterns established in infancy track to mid-childhood: The EU childhood obesity project. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh, E.Z.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.; Kontulainen, S.; Whiting, S.J.; Vatanparast, H. Tracking dietary patterns over 20 years from childhood through adolescence into young adulthood: The Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lioret, S.; McNaughton, S.; Spence, A.; Crawford, D.; Campbell, K. Tracking of dietary intakes in early childhood: The Melbourne InFANT Program. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund. NOURISHING Framework. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/policy-databases/nourishing-framework (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Jarpe-Ratner, E.; Folkens, S.; Sharma, S.; Daro, D.; Edens, N.K. An experiential cooking and nutrition education program increases cooking self-efficacy and vegetable consumption in children in grades 3–8. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 697–705.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmer, S.M.; Salisbury-Glennon, J.; Shannon, D.; Struempler, B. School gardens: An experiential learning approach for a nutrition education program to increase fruit and vegetable knowledge, preference, and consumption among second-grade students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersch, D.; Perdue, L.; Ambroz, T.; Boucher, J.L. Peer reviewed: The impact of cooking classes on food-related preferences, attitudes, and behaviors of school-aged children: A systematic review of the evidence, 2003–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.; Cotton, W.; Peralta, L. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoie-Roskos, M.R.; Wengreen, H.; Durward, C. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake among children and youth through gardening-based interventions: A systematic review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muliasari, D.N. Promoting Critical Thinking through Children’s Experiential Learning. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Early Childhood Education (ICECE 2016), Bandung, Indonesia, 11–12 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Illeris, K. What do we actually mean by experiential learning? Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2007, 6, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCosta, P.; Møller, P.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. Changing children’s eating behaviour-A review of experimental research. Appetite 2017, 113, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Pearson Education, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and education. In The Educational Forum; Taylor & Francis Group: England, UK, 1986; Volume 50, pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloglovsky, M.; Daly, L. Early Learning Theories Made Visible; Redleaf Press: St Paul, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, K.; Comerford, T.; Deavin, N.; Walton, K. Characteristics of successful primary school based experiential nutrition programs: A Systematic Literature Review. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 4642–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ-Brit. Med. J. 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.; Bejarano, C.M.; Cushing, C.C.; Staggs, V.S.; Papa, A.E.; Steel, C.; Shook, R.P.; Sullivan, D.K.; Couch, S.C.; Conway, T.L. Differences in adolescent activity and dietary behaviors across home, school, and other locations warrant location-specific intervention approaches. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Sterne, J.A.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Boutron, I.; Reeves, B.; Eldridge, S. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2 (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Laurence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 19–74. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, C.; Huybrechts, I.; Van Houte, H.; Martens, V.; Wittebroodt, I.; Maes, L. Results from a dietary intervention study in preschools “Beastly Healthy at School”. Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, K.E.; Dunn, C. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among preschoolers: Evaluation of Color Me Healthy. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, R.J.N.; Neelon, S.E. Watch Me Grow: A garden-based pilot intervention to increase vegetable and fruit intake in preschoolers. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Andrade, G.O.; Cespedes, E.M.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Romero-Quechol, G.; González-Unzaga, M.A.; Benítez-Trejo, M.A.; Flores-Huerta, S.; Horan, C.; Haines, J.; Taveras, E.M. Feasibility and impact of Creciendo Sanos, a clinic-based pilot intervention to prevent obesity among preschool children in Mexico City. BMC Pediatrics 2014, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dazeley, P.; Houston-Price, C. Exposure to foods’ non-taste sensory properties. A nursery intervention to increase children’s willingness to try fruit and vegetables. Appetite 2015, 84, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jisoo, H.; Bales, D.W.; Wallinga, C.R. Using Family Backpacks as a Tool to Involve Families in Teaching Young Children About Healthy Eating. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018, 46, 209. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, C.L.; Bishop, D.B.; Taylor, G.; Murray, D.M.; Mays, R.W.; Dudovitz, B.S.; Smyth, M.; Story, M. Changing fruit and vegetable consumption among children: The 5-a-Day Power Plus program in St. Paul, Minnesota. Am. J. Public Health 1998, 88, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bere, E.; Veierød, M.; Bjelland, M.; Klepp, K.I. Free school fruit—Sustained effect 1 year later. Health Educ. Res. 2005, 21, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bere, E.; Veierd, M.B.; Bjelland, M.; Klepp, K.-I. Outcome and process evaluation of a Norwegian school-randomized fruit and vegetable intervention: Fruits and Vegetables Make the Marks (FVMM). Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-L.; Weiss, S.; Heyman, M.B.; Lustig, R.H. Efficacy of a child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy behaviors in Chinese American children: A randomized controlled study. J. Public Health 2009, 32, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, J.A.; Rydell, S.; Kubik, M.Y.; Lytle, L.; Boutelle, K.; Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Dudovitz, B.; Garwick, A.J.O. Healthy Home Offerings via the Mealtime Environment (HOME): Feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes of a pilot study. Obesity 2010, 18, S69–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, R.R.; Behrens, T.K.; Dzewaltowski, D.A. A group-randomized controlled trial for health promotion in Girl Scouts: Healthier troops in a SNAP (Scouting Nutrition & Activity Program). BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Keihner, A.J.; Meigs, R.; Sugerman, S.; Backman, D.; Garbolino, T.; Mitchell, P. The Power Play! Campaign’s School Idea & Resource Kits improve determinants of fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity among fourth-and fifth-grade children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, S122–S129. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D.L.; Katz, C.S.; Treu, J.A.; Reynolds, J.; Njike, V.; Walker, J.; Smith, E.; Michael, J. Teaching healthful food choices to elementary school students and their parents: The Nutrition Detectives™ program. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.E.; Least, C.; Gromis, J.; Lohse, B. Nutrition education intervention improves vegetable-related attitude, self-efficacy, preference, and knowledge of fourth-grade students. J. Sch. Health 2012, 82, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Noonan, C.; Harris, K.J.; Parker, M.; Gaskill, S.; Ricci, C.; Cobbs, G.; Gress, S. Developing and piloting the journey to native youth health program in Northern Plains Indian communities. Diabetes Educ. 2013, 39, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib-Mourad, C.; Ghandour, L.A.; Moore, H.J.; Nabhani-Zeidan, M.; Adetayo, K.; Hwalla, N.; Summerbell, C. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: Findings from Health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, N.M.; Myers, B.M.; Todd, L.E.; Barale, K.; Gaolach, B.; Ferenz, G.; Aitken, M.; Henderson, C.R.; Tse, C.; Pattison, K.O. The effects of school gardens on children’s science knowledge: A randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2858–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allirot, X.; da Quinta, N.; Chokupermal, K.; Urdaneta, E. Involving children in cooking activities: A potential strategy for directing food choices toward novel foods containing vegetables. Appetite 2016, 103, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaChausse, R.G. A clustered randomized controlled trial to determine impacts of the Harvest of the Month program. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Bhattarai, D.R.; Subedi, G.D.; Acharya, T.P.; Chen, H.-P.; Yang, R.-Y.; Kashichhawa, N.K.; Dhungana, U.; Luther, G.C.; Mecozzi, M. Impact of school gardens in Nepal: A cluster randomised controlled trial. J. Dev. Eff. 2017, 9, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Rai, B.B.; Dorji, D.; Chen, H.-P.; Dukpa, T.; Thinley, N.; Sherpa, P.L.; Yang, R.-Y. School gardening in Bhutan: Evaluating outcomes and impact. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keihner, A.; Rosen, N.; Wakimoto, P.; Goldstein, L.; Sugerman, S.; Hudes, M.; Ritchie, L.; McDevitt, K. Impact of California Children’s Power Play! Campaign on fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity among fourth-and fifth-grade students. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherr, R.E.; Linnell, J.D.; Dharmar, M.; Beccarelli, L.M.; Bergman, J.J.; Briggs, M.; Brian, K.M.; Feenstra, G.; Hillhouse, J.C.; Keen, C.L.; et al. A multicomponent, school-based intervention, the Shaping Healthy Choices Program, improves nutrition-related outcomes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 368–379.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allirot, X.; Maiz, E.; Urdaneta, E. Shopping for food with children: A strategy for directing their choices toward novel foods containing vegetables. Appetite 2018, 120, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Evans, C.E.; Nykjaer, C.; Hancock, N.; Cade, J.E. Evaluation of the impact of a school gardening intervention on children’s fruit and vegetable intake: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Christian, M.S.; Evans, C.E.L.; Nykjaer, C.; Hancock, N.; Cade, J.E. Evaluation of the impact of school gardening interventions on children’s knowledge of and attitudes towards fruit and vegetables. A cluster randomised controlled trial. Appetite 2015, 91, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, A.; Larson, M.; Tucker, J.; Strang, M. Classroom nutrition education combined with fruit and vegetable taste testing improves children’s dietary intake. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.M.; Kaur, S.; Koo, H.C.; Mukhtar, F. Involvement of children in hands-on meal preparation and the associated nutrition outcomes: A scoping review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minich, D.M. A review of the science of colorful, plant-based food and practical strategies for “eating the rainbow”. J. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.S.; Winett, R.A.; Wojcik, J.R. Self-regulation, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and social support: Social cognitive theory and nutrition behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2007, 34, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S. The role of food experiences during early childhood in food pleasure learning. Appetite 2016, 104, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston-Price, C.; Butler, L.; Shiba, P. Visual exposure impacts on toddlers’ willingness to taste fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2009, 53, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.M.; Pollock, E.D.; Braun, B. Family influence: Key to fruit and vegetable consumption among fourth-and fifth-grade students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micha, R.; Karageorgou, D.; Bakogianni, I.; Trichia, E.; Whitsel, L.P.; Story, M.; Penalvo, J.L.; Mozaffarian, D. Effectiveness of school food environment policies on children’s dietary behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).