Abstract

Identifying determinants of medication non-adherence in patients with multimorbidity would provide a step forward in developing patient-centered strategies to optimize their care. Medication appropriateness has been proposed to play a major role in medication non-adherence, reinforcing the importance of interdisciplinary medication review. This study examines factors associated with medication non-adherence among older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. A cross-sectional study of non-institutionalized patients aged ≥65 years with ≥2 chronic conditions and ≥5 long-term medications admitted to an intermediate care center was performed. Ninety-three patients were included (mean age 83.0 ± 6.1 years). The prevalence of non-adherence based on patients’ multiple discretized proportion of days covered was 79.6% (n = 74). According to multivariable analyses, individuals with a suboptimal self-report adherence (by using the Spanish-version Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale) were more likely to be non-adherent to medications (OR = 8.99, 95% CI 2.80–28.84, p < 0.001). Having ≥3 potentially inappropriate prescribing (OR = 3.90, 95% CI 0.95–15.99, p = 0.059) was barely below the level of significance. These two factors seem to capture most of the non-adherence determinants identified in bivariate analyses, including medication burden, medication appropriateness and patients’ experiences related to medication management. Thus, the relationship between patients’ self-reported adherence and medication appropriateness provides a basis to implement targeted strategies to improve effective prescribing in patients with multimorbidity.

1. Introduction

As the global population is ageing, the prevalence of people living with multimorbidity, defined as the presence of two or more chronic conditions, becomes increasingly common []. Elderly individuals with multimorbidity are associated with poorer health outcomes, including lower health-related quality of life, higher utilization of health care services, increased disability, frailty and mortality [].

Polypharmacy, i.e., the use of five or more medications, is steadily rising in older adults due to the strict application of clinical practice guidelines focused on patients with single chronic conditions []. Medication non-adherence is a frequent consequence of polypharmacy. Among medication non-adherence negative effects are increased morbidity, mortality and costs. Patients with multimorbidity are more likely to have polypharmacy and frailty, making them especially vulnerable to non-adherence and the associated consequences [,].

Adherence to medications is the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed, further divided into three quantifiable phases: initiation, implementation and discontinuation. In accordance with ABC taxonomy, non-adherence can occur due to a late or non-initiation of the prescribed treatment, suboptimal implementation of the dosing regimen or early discontinuation []. Medication non-adherence is a multi-factorial process caused by a highly complex interplay between many modifiable and unmodifiable determinants, which can be categorized into five dimensions (socioeconomic, patient-related, therapy-related, condition-related and health system-related) []. The more complex a treatment regimen, the higher the risk of non-adherence. Medication adherence also changes due to adverse drug events (ADEs) or patients’ inadequate knowledge and/or beliefs about drug therapy []. However, most of the research on medication non-adherence determinants has focused on patients with single chronic conditions despite the urgent need to understand what influences patients with multimorbidity to take their medicines [].

There is no standard criterion available to measure adherence in patients receiving polypharmacy, so appropriate measurement of multiple medication adherence remains a challenge []. Self-report methods are the most frequently used indirect methods for measuring medication adherence []. Nevertheless, the use of self-report measures in monitoring medication adherence remains controversial as they can be biased by a ceiling effect []. In contrast, self-report measures might help inform tailored interventions by identifying individual barriers and beliefs that are influencing medication adherence []. Furthermore, the use of dispensing data has been a staple in adherence measurements due to their validity, relative accessibility and inexpensiveness []. This allows the calculation of quasi-objective measures of adherence such as medication possession ratio (MPR) and proportion of days covered (PDC), based on the percentage of days the patient has medication available. Formulas for derivation of MPR or PDC differ between studies []. Multiple discretized PDC might be considered an estimate of choice due to its sensitivity, specificity and applicability [].

Identifying variables influencing medication non-adherence in patients with multimorbidity by means of appropriate estimates would provide a step forward in developing patient-centered strategies to optimize their care.

The main aim of this study was to examine factors associated with the likelihood of medication non-adherence among non-institutionalized older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy admitted to an intermediate care center.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Participants

This was a cross-sectional study representing a substudy of a quasi-experimental (before–after) research, the main goal of which was to assess the efficacy of a patient-centered prescription model to improve medication adherence and effective prescribing (defined as the process by which a provider selects the best medication regimen for accomplishing clinical and patient-centered goals after weighing shared decision making) [] in 93 patients with multimorbidity. The study setting was a convalescent and rehabilitation ward in San Jaume de Manlleu Hospital, a 66-bed intermediate care step-down community hospital located close to Vic University Hospital, an acute care teaching hospital. Both are referral care centers for the Osona county, a mixed urban–rural district in Barcelona, Spain, with a population of 160,000 inhabitants, 3.3% aged 85 years or more.

Patients were consecutively considered for inclusion if they met the following eligibility criteria: older people (≥65 years) with ≥2 chronic conditions (from the expanded diagnostic clusters within the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) system) [] who were receiving polypharmacy (≥5 regularly scheduled long-term (≥3 months) medications) before hospital admission. Patients were excluded from study participation if any of the following was applicable: limited life expectancy (using NECPAL CCOMS-ICO® tool criteria) [], nursing home residents or hospital admissions during the 6 months prior to inclusion in the study (to ensure an appropriate assessment of medication adherence). Potential participants were screened for eligibility before hospital discharge. In case of agreeing to participate, they were assigned a code number prior to data entry to maintain anonymity. From April 2019 to February 2020, potential participants were enrolled in the study if informed consent was provided by them or by their relatives in case of them being unable to provide consent, as approved by the ethics committee. Recruitment finished just before COVID-19 outbreak hit the Osona county.

Recommendations from STROBE guideline [] and ESPACOMP Medication Adherence Reporting Guideline (EMERGE) [] were followed.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Demographic and Clinical Data

The following demographic and clinical data were collected: age, sex, chronic conditions (from the expanded diagnostic clusters within the Johns Hopkins University ACG system) [], frailty index (Frail-VIG) [], Barthel index for activities of daily living [] and cognitive impairment (MMSE) []. Demographic and clinical data were collected from patient’s electronic medical records and by interviewing the patient and/or main caregiver. Frailty index, Barthel index and cognitive status corresponded to the patient’s status before hospitalization

2.2.2. Medication-Related Data

The following medication-related data were collected:

- Long-term medications: Estimated as the sum of every regularly scheduled medication intended to be administered for a period ≥ 3 months.

- Hyperpolypharmacy: Also known as excessive polypharmacy, defined as the use of 10 or more regularly scheduled long-term medications [].

- Medication regimen complexity: Assessed as a continuous variable for all long-term medications (defined as regularly scheduled long-term medications plus when required (prn) medications) on admission using the Spanish-version Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI) []. Furthermore, regimen complexity was also categorized as low (equivalent to MRCI < 20), medium–high (MRCI 20–39.5) or excessive (MRCI ≥ 40).

- Anticholinergic and sedative risk score: Assessed by using the Drug Burden Index (DBI) [,] for every regularly scheduled long-term medication prescribed before admission.

- Potentially inappropriate prescribing (PIP). Every patient’s treatment plan was analyzed by a geriatrician and a clinical pharmacist through the 4-stage patient-centered prescription (PCP) model, which centers therapeutic decisions on the patient’s global assessment. Such an approach represents an advanced medication review framework [], which has been associated with reducing inappropriate prescribing and medication burden in patients with multimorbidity [,,]. The PCP model was developed by the Central Catalonia Chronicity Research Group (C3RG) and its implementation in clinical practice is recommended by the Department of Health, Government of Catalonia (Spain) for elderly and frail patients with multimorbidity []. PIP was considered on admission in any of the following circumstances: absence of evidence-based indication, dosing unnecessarily high considering the patient’s specific therapeutic objectives, unacceptable ADEs, contraindicated drug–drug interaction, unnecessary therapeutic duplication, inappropriate dosing or pharmaceutical dosage form or any prescription characterized as potentially inappropriate by the American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated Beers criteria® []. PIP was assessed as a continuous variable and categorized as moderate (≥2) and high (≥3) PIP burden.

- Self-reported adherence. A self-report measure of medication adherence was performed by using the Spanish-version Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS-e) []. This scale consists of 12 items that assess patients’ ability to take and refill medications. Response options are on a Likert scale with responses of “none”, “some”, “most” or “all” of the time, which are given values from 1 to 4. Items were written so that a lower score is indicative of better medication adherence. The ARMS-e total score ranges from 12 to 48. Therefore, a patient that does not have any non-adherence issue will score 12, with higher scores indicating worst adherence. Written permission for conducting adherence assessments was obtained from the original developer of the English-version ARMS []. ARMS-e total score, based on an ordinal scale, was dichotomized through the median score using a cutoff value of 12 (optimal self-reported adherence = 12 and suboptimal self-reported adherence > 12).

- Medication management at home: Patients were grouped on three levels (independent, partially or totally assisted) with regard to their autonomy for medication administration and medication refills before hospital admission.

- Multiple discretized PDC: Medication adherence was assessed during a 6-month period before admission using the multiple discretized PDC, which was considered the main dependent variable. PDC for all regularly scheduled long-term medications was estimated as the sum of the days supplied for each medication according to electronic linked pharmacy claims data. At least two prescription refill dates during a period ≥ 90 days were required for each medication to calculate this ratio. The PDC rate was converted to a percentage based on the percentage of days covered by dispensed medication. Patients were considered adherent if PDC for each medication was ≥80% (excluding last refill) [].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 27.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results for categorical variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and results for continuous variables as means and standard deviations (SD) if they followed a normal distribution, or as the median and inter-quartile range (IQR) if they did not follow a normal distribution.

Comparisons between adherent and non-adherent patients (by considering their multiple discretized PDC before admission) were performed using Student’s t test for parametric continuous variables (normally distributed) or the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric continuous variables (not normally distributed). The chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate) was applied to compare categorical variables between adherent and non-adherent patients.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of each predictor on medication non-adherence before admission. The multivariate model was used for variables that had a p value < 0.10 in the bivariate analyses using stepwise regression.

Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value of 0.05.

3. Results

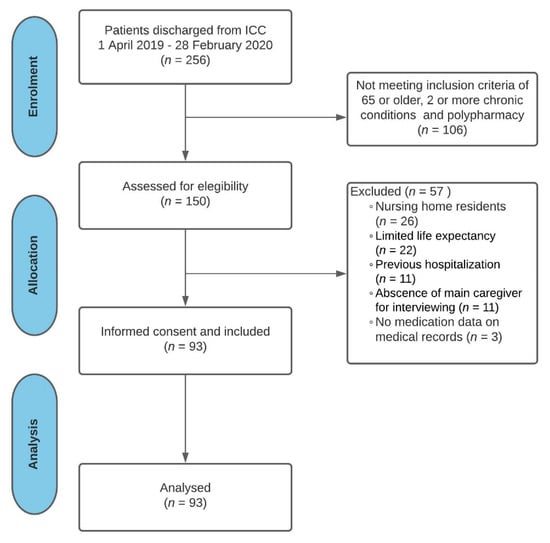

Out of the 256 patients who were eligible to participate in the study, a total of 93 non-institutionalized older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy were finally included (Figure 1). Table 1 shows demographics in addition to clinical and medication characteristics of the study participants.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram: study participation and selection process. Abbreviations: ICC: intermediate care center.

Table 1.

Characteristics of non-institutionalized older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy admitted to an intermediate care center by medication adherence level.

The average age was 83.0 (SD 6.1) years, and the majority of patients were female (65.6%, n = 61). The patients had a mean number of chronic conditions of 7.4 (SD 1.8). About 80.7% (n = 75) had mild or moderate frailty, 53.8% (n = 50) had mild-to-moderate dependence for activities of daily living and 43% (n = 40) had cognitive impairment.

Patients were receiving an average of 8.8 (SD 2.8) regularly scheduled long-term medications, 62% (n = 57) of them being exposed to moderate-high or excessive medication regimen complexities. Moreover, a high prevalence of PIP was characterized with at least one PIP detected in almost every patient (98.9%, n = 92). Most of the study population (75.3%, n = 70) reported a suboptimal adherence despite a substantial proportion of them being partially or totally assisted for medication refills (62.4%, n = 58) or medication administration (50.5%, n = 47) at home.

The prevalence of non-adherence based on patients’ multiple discretized PDC was 79.6% (n = 74). Differences in demographic, clinical and medication characteristics between non-adherent and adherent patients in accordance with their multiple discretized PDC are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between both groups.

According to the bivariate analyses (Table 2), being exposed to a higher number of regularly scheduled long-term medications was positively associated with the likelihood of being non-adherent (OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.13–1.89, p = 0.004). In the same manner, a 1-point increase in medication regimen complexity was associated with 7% higher odds of being non-adherent (OR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.01–1.34, p = 0.025). Compared with those with low medication regimen complexities, the OR for those exposed to moderate-high medication regimen complexities was 5.94 (95% CI 1.73–20.32, p = 0.005). Furthermore, hyperpolypharmacy was also associated with a higher probability of being non-adherent (OR = 4.06, 95% CI 1.09–15.15, p = 0.037).

Table 2.

Logistic regression examining factors associated with medication non-adherence in older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy admitted to an intermediate care center.

A positive association between medication appropriateness and medication adherence was revealed through the OR for those exposed to high PIP burden (OR = 4.53, 95% CI 1.22–16.89, p = 0.024).

Further, a 1-unit increase in ARMS-e total score was associated with a 38% increase in patients’ odds of being non-adherent (OR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.13–1.67, p = 0.001). Similarly, suboptimal self-reported adherence (equivalent to ARMS > 12 points) was also significantly associated with medication non-adherence (OR = 9.82, 95% CI 3.17–30.42, p < 0.001).

The following variables, although not significantly associated with medication non-adherence at bivariate analyses, were included in the multivariate regression model due to a p value < 0.10: number of chronic conditions, number of PIP, moderate PIP and being partially assisted for medication refills at home.

Based on the multivariable logistic regression model (Table 2), individuals with a suboptimal self-reported adherence were more likely to be non-adherent to medications (OR = 8.99, 95% CI 2.80–28.84, p < 0.001). Having a high PIP burden (OR = 3.90, 95% CI 0.95–15.99, p = 0.059) was barely below the level of significance.

4. Discussion

By using pharmacy claims data to estimate multiple discretized PDC, this study examined factors associated with medication non-adherence in non-institutionalized older patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy, most of them with clinical frailty, dependence for activities of daily living and regularly exposure to a high medication burden. The results demonstrated that suboptimal self-reported adherence characterized by using the Spanish-version ARMS is strongly associated with medication nonadherence based on pharmacy claims data. In addition, being exposed to a high PIP burden appears to also influence medication non-adherence. These two factors combined seem to capture most of the non-adherence determinants identified in bivariate analyses, including medication burden, medication appropriateness and patients’ experiences related to medication taking and refills.

Our results highlight the relevance of effective prescribing regarding the care of older patients with multimorbidity. Medication appropriateness and effective prescribing are both close but not interchangeable terms as the latter includes discussion of solutions to patients’ perceived barriers to obtaining and taking medications that are part of an agreed-upon treatment plan []. Medication adherence and medication appropriateness are therefore necessarily linked through effective prescribing. Considering our results, the use of subjective and objective measures within strategies aimed to enhance effective prescribing would lead us a systemic approach to identify patients at risk for medication non-adherence.

Our results are consistent with previous findings focused on the assessment of factors related to medication non-adherence among chronic patients. Medication burden assessed through the number of long-term medications, prevalence of hyperpolypharmacy or medication regimen complexity is a well-established determinant that negatively affects medication adherence [,,]. Our findings would reinforce prior evidence through a sample of frail patients with multimorbidity.

Nevertheless, the negative association between cumulative PIP and medication adherence reported in our study has not been characterized before in patients with multimorbidity. This is of particular importance due to the high prevalence of PIP in older patients admitted to intermediate care facilities []. PIP has been related to higher incidence of ADEs [,], which could negatively affect medication adherence, thereby explaining the link between PIP and medication adherence. Moreover, medication burden has been identified as a risk factor for PIP and ADEs [,], thus reinforcing the usefulness of PIP as a predictor of medication non-adherence.

Furthermore, evidence regarding an association between ARMS scores and pharmacy claims data has been lacking to date in very elderly patients with frailty. The ARMS-e has been cross-culturally adapted to Spanish, but a formal validation is still not available []. In the meantime, self-report adherence measures using the ARMS-e seem to reflect medication adherence estimated through a quasi-objective measure such as the multiple discretized PDC. Previous association suggests the usefulness of the ARMS-e for a qualitative screening of non-adherent elderly patients with multimorbidity.

Since ARMS allows the assessment of patients’ experiences related to medication taking and refills, our results would be consistent with those of Kvarnström et al., pointing out communication and information on medicines among the critical factors for medication adherence []. This is aligned with growing consensus about including patients’ experiences and preferences within advanced medication review frameworks to overcome medication adherence barriers and align medication therapies with patients’ goals of care [].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing factors associated with medication non-adherence by using the multiple discretized PDC, which has shown to double specificity as compared to other quasi-objective adherence measures such as the mean PDC or MPR []. This fact might justify the low adherence rates described in our study in comparison with previous research []. According to simulation modeling conducted by Pedkenar et al. [] there might be a more accurate estimate, but its implementation would be limited because of its advanced technical requirements.

Further, amongst the strengths of our study we also highlight the greater knowledge it provides on the characteristics of patients with multimorbidity admitted to a scarcely explored setting. Moreover, it empirically suggests for the first time the existence of an association between medication non-adherence and medication appropriateness.

The authors acknowledge the small sample size as the study main limitation. This is because sample size was estimated to test the primary hypothesis in a quasi-experimental (before–after) research. Nevertheless, this might have negatively affected statistical power, including the value barely below the level of significance for high PIP burden found in the multivariate analyses. Thereby, previous results warrant further investigation.

In addition, the use of the PIP burden as an estimate of medication appropriateness is not sufficiently standardized according to published literature. However, the association of cumulative PIP with poorer health outcomes in older people combined with the high prevalence of PIP in older patients with multimorbidity exposed to polypharmacy would support their use [,,].

Additionally, medication adherence might be overestimated by using dispensing data from a six-month period due to situations such as drug oversupply or stockpiling []. Their influence on medication adherence estimates would be attenuated by the existence in the study setting of limitations for medication dispensing for periods longer than a month. Further, PDC accounts for overlapping days supplied to allow a more conservative estimate of adherence than MPR [].

Finally, we cannot extend our results to every patient with multimorbidity because our findings are probably influenced by the high burden of PIP observed in study participants.

Despite its limitations, the present study provides new evidence regarding the need to implement patient-centered strategies aimed at improving effective prescribing in patients with multimorbidity to enhance both medication appropriateness and adherence. Such approaches should consider both objective and subjective medication adherence predictors as PIP burden and self-reported medication adherence, respectively. How these approaches would be feasibly implemented in clinical practice represents a future challenge. To date, strategies centered on enhancing effective prescribing have mainly been driven by pharmacists and focused on the relevance of educational aspects to optimize medication management and adherence []. Our results suggest effective prescribing should be more widely addressed by also considering interdisciplinary collaboration and medication appropriateness issues.

Further, ARMS has been proposed as a useful tool for identifying patients at risk of being non-adherents due to a suboptimal implementation of the dosing regimen and/or early discontinuation []. Future research might also explore how PIP burden influences medication adherence phases as per the ABC taxonomy [].

5. Conclusions

The relationship between medication appropriateness and patient experience related to medication taking and refills measured through a self-report adherence method seems to play a key role in medication non-adherence in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy admitted to an intermediate care center. These findings provide a step forward in developing patient-centered strategies focus on improving effective prescribing in older patients with multimorbidity. These strategies should consider interdisciplinary collaboration and medication appropriateness issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-B., D.S.-S., E.P.-J., N.M.-B., C.C.-J. and J.E.-P.; Formal analysis, J.G.-B., D.S.-S., E.P.-J. and N.M.-B.; Methodology, J.G.-B. and E.P.-J.; Writing—original draft, J.G.-B.; Writing—review and editing, D.S.-S., E.P.-J., N.M.-B., C.C.-J. and J.E.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study (ID: PR223) was approved by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the Osona Foundation for Research and Health Education—Vic Consortium Hospital, Barcelona, Spain. The authors certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank study participants and their family members for their participation and interest in the study. The assistance of medical and nurse facility staff is gratefully acknowledged, including Antoni Casals, Joan Carles Rovira, Anna Torné and Anna Ribera.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Vetrano, D.L.; Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Marzetti, E.; Lattanzio, F.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.; Lopez Samaniego, L.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Frailty and Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2019, 74, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Wu, C.; Odden, M.C.; Kim, D.H. Multimorbidity patterns, frailty, and survival in community-dwelling older adults. J. Gerontol.-Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.D.; McMurdo, M.E.T.; Guthrie, B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: The challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Ferrucci, L.; Darer, J.; Williamson, J.D.; Anderson, G. Untangling the Concepts of Disability, Frailty, and Comorbidity: Implications for Improved Targeting and Care. J. Gerontol.-Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2004, 59, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengoni, A.; Onder, G. Guidelines, polypharmacy, and drug-drug interactions in patients with multimorbidity: A cascade of failure. BMJ 2015, 350, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- González-Bueno, J.; Calvo-Cidoncha, E.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; Molist-Brunet, N.; Espaulella-Panicot, J.; Codina-Jané, C. Patient-centered prescription model to improve therapeutic adherence in patients with multimorbidity. Farm. Hosp. 2018, 42, 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès-Puigdemont, N.; Tuneu, L.; Masip, M.; Valls, P.; Puig, T.; Mangues, M.A. Determinants of medication adherence among chronic patients from an urban area: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pednekar, P.P.; Ágh, T.; Malmenäs, M.; Raval, A.D.; Bennett, B.M.; Borah, B.J.; Hutchins, D.S.; Manias, E.; Williams, A.F.; Hiligsmann, M.; et al. Methods for Measuring Multiple Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review–Report of the ISPOR Medication Adherence and Persistence Special Interest Group. Value Health 2019, 22, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardini, A.; Martin, M.T.; Cahir, C.; Lehane, E.; Menditto, E.; Strano, M.; Pecorelli, S.; Monaco, A.; Marengoni, A. Toward appropriate criteria in medication adherence assessment in older persons: Position Paper. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirratt, M.J.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Crane, H.M.; Simoni, J.M.; Czajkowski, S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Aikens, J.E.; Hunter, C.M.; Velligan, D.I.; Huntley, K.; et al. Self-report measures of medication adherence behavior: Recommendations on optimal use. Transl. Behav. Med. 2015, 5, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.M.U.; Caze, A.L.; Cottrell, N. What are validated self-report adherence scales really measuring? A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 77, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Robles, A.; Wiecek, E.; Cutler, R.; Drake, B.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Using Dispensing Data to Evaluate Adherence Implementation Rates in Community Pharmacy. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pednekar, P.; Malmenas, M.M.; Ágh, T.; Bennett, B.; Peterson, A. Measuring multiple medication adherence—Which measure when? Value Outcomes Spotligh 2017, 17–20. Available online: https://www.ispor.org/docs/default-source/publications/newsletter/measuring_multiple_medication_adherence_which_measure_when.pdf?sfvrsn=f9946e55_0 (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- McMullen, C.K.; Safford, M.M.; Bosworth, H.B.; Phansalkar, S.; Leong, A.; Fagan, M.B.; Trontell, A.; Rumptz, M.; Vandermeer, M.L.; Brinkman, W.B.; et al. Patient-centered priorities for improving medication management and adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salisbury, C.; Johnson, L.; Purdy, S.; Valderas, J.M.; Montgomery, A.A. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 61, e12–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Blay, C.; Amblàs, J.; Vila, L.; Costa, X.; Espaulella, J.; Villanueva, A.; Oller, R.; Martori, J.C.; et al. Utility of the NECPAL CCOMS-ICO© tool and the Surprise Question as screening tools for early palliative care and to predict mortality in patients with advanced chronic conditions: A cohort study. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geest, S.; Zullig, L.L.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Helmy, R.; Hughes, D.A.; Wilson, I.B.; Vrijens, B. ESPACOMP medication adherence reporting guideline (EMERGE). Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblàs-Novellas, J.; Martori, J.C.; Espaulella, J.; Oller, R.; Molist-Brunet, N.; Inzitari, M.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Frail-VIG index: A concise frailty evaluation tool for rapid geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Marengoni, A.; Forjaz, M.J.; Jureviciene, E.; Laatikainen, T.; Mammarella, F.; Muth, C.; Navickas, R.; Prados-Torres, A.; Rijken, M.; et al. Multimorbidity care model: Recommendations from the consensus meeting of the Joint Action on Chronic Diseases and Promoting Healthy Ageing across the Life Cycle (JA-CHRODIS). Health Policy 2018, 122, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, R.M.; Anthony, J.C.; Bassett, S.S.; Folstein, M.F. Population-Based Norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by Age and Educational Level. JAMA 1993, 269, 2386–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Valencia, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Cesari, M.; Casas-Herrero, Á.; Inzitari, M.; Martínez-Velilla, N. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1432–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez de la Fuente, J.; Such Diaz, A.; Cañamares-Orbis, I.; Ramila, E.; Izquierdo-Garcia, E.; Esteban, C.; Escobar-Rodríguez, I. Cross-cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Medication Regimen Complexity Index Adapted to Spanish. Ann. Pharmacother. 2016, 50, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, S.N.; Mager, D.E.; Simonsick, E.M.; Cao, Y.; Ling, S.M.; Windham, B.G.; Harris, T.B.; Hanlon, J.T.; Rubin, S.M.; Shorr, R.I.; et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.J.; Walsh, C.; Cahir, C.; Ryan, C.; Williams, D.J.; Bennett, K. Anticholinergic and sedative drug burden in community-dwelling older people: A national database study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griese-Mammen, N.; Hersberger, K.E.; Messerli, M.; Leikola, S.; Horvat, N.; van Mil, J.W.F.; Kos, M. PCNE definition of medication review: Reaching agreement. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2018, 40, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molist Brunet, N.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; Amblàs Novellas, J.; Codina Jané, C.; Gómez-Batiste, X.; McIntosh, J.; Espaulella Panicot, J. Optimizing drug therapy in patients with advanced dementia: A patient-centered approach. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 5, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molist-Brunet, N.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; Puigoriol-Juvanteny, E.; González-Bueno, J.; Solà- Bonada, N.; Cruz-Grullón, M.; Espaulella-Panicot, J. Optimizing drug therapy in frail patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molist-Brunet, N.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; González-Bueno, J.; Garcia-Sánchez, V.; Segura-Martín, L.A.; Codina-Jané, C.; Espaulella-Panicot, J. Therapeutic optimization through goal-oriented prescription in nursing homes. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2021, 43, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departament de Salut. Generalitat de Catalunya. Bases Conceptuals i Model d’atenció per a les Persones fràgils, amb Cronicitat Complexa o Avançada; Departament de Salut: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://salutweb.gencat.cat/web/.content/_ambits-actuacio/Linies-dactuacio/Estrategies-de-salut/Cronicitat/Documentacio-cronicitat/arxius/Model-de-Bases-de-Cronicitat.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Fick, D.M.; Semla, T.P.; Steinman, M.; Beizer, J.; Brandt, N.; Dombrowski, R.; DuBeau, C.E.; Pezzullo, L.; Epplin, J.J.; Flanagan, N.; et al. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar]

- González-Bueno, J.; Calvo-Cidoncha, E.; Sevilla-Sánchez, D.; Espaulella-Panicot, J.; Codina-Jané, C.; Santos-Ramos, B. Spanish translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the ARMS-scale for measuring medication adherence in polypathological patients. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kripalani, S.; Risser, J.; Gatti, M.E.; Jacobson, T.A. Development and Evaluation of the Adherence to Refills and Medications Scale (ARMS) among Low-Literacy Patients with Chronic Disease. Value Health 2009, 12, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J.L.; Safford, M.M.; Singh, J.A.; Phansalkar, S.; Slight, S.P.; Her, Q.L.; Lapointe, N.A.; Mathews, R.; O’Brien, E.; Brinkman, W.B.; et al. Patient-centered interventions to improve medication management and adherence: A qualitative review of research findings. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimmer, B.C.; Cross, A.J.; Jokanovic, N.; Wiese, M.D.; George, J.; Johnell, K.; Diug, B.; Bell, J.S. Clinical Outcomes Associated with Medication Regimen Complexity in Older People: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasina, L.; Brucato, A.L.; Falcone, C.; Cucchi, E.; Bresciani, A.; Sottocorno, M.; Taddei, G.C.; Casati, M.; Franchi, C.; Djade, C.D.; et al. Medication non-adherence among elderly patients newly discharged and receiving polypharmacy. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Jover, V.; Mira, J.; Carratala-Munuera, C.; Gil-Guillen, V.; Basora, J.; López-Pineda, A.; Orozco-Beltrán, D. Inappropriate Use of Medication by Elderly, Polymedicated, or Multipathological Patients with Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, G.; Pasina, L.; Cortesi, L.; Cesari, M.; Bergamaschini, L. Inappropriate prescribing in intermediate care facilities. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 1085–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, F.; Cahir, C.; Bennett, K.; Hughes, C.M.; Kenny, R.A.; Fahey, T. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and its association with health outcomes in middle-Aged people: A prospective cohort study in Ireland. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; McDowell, R.; Bennett, K.; Fahey, T.; Smith, S.M. Impact of Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing on Adverse Drug Events, Health Related Quality of Life and Emergency Hospital Attendance in Older People Attending General Practice: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommelein, E.; Mehuys, E.; Petrovic, M.; Somers, A.; Colin, P.; Boussery, K. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in community-dwelling older people across Europe: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevilla-Sanchez, D.; Molist-Brunet, N.; Amblàs-Novellas, J.; Roura-Poch, P.; Espaulella-Panicot, J.; Codina-Jané, C. Adverse drug events in patients with advanced chronic conditions who have a prognosis of limited life expectancy at hospital admission. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 73, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström, K.; Westerholm, A.; Airaksinen, M.; Liira, H. Factors Contributing to Medication Adherence in Patients with a Chronic Condition: A Scoping Review of Qualitative Research. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosworth, H.B.; Fortmann, S.P.; Kuntz, J.; Zullig, L.L.; Mendys, P.; Safford, M.; Phansalkar, S.; Wang, T.; Rumptz, M.H. Recommendations for Providers on Person-Centered Approaches to Assess and Improve Medication Adherence. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bennett, K.; Wallace, E.; Fahey, T.; Cahir, C. Measuring medication adherence in older community-dwelling patients with multimorbidity. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 74, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, D.L.; Lee, T.C.; McDonald, E.G.; Motulsky, A.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Morgan, S.; Buckeridge, D.; Tamblyn, R. Both New and Chronic Potentially Inappropriate Medications Continued at Hospital Discharge Are Associated with Increased Risk of Adverse Events. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, F.; Bennett, K.; Kenny, R.A.; Fahey, T.; Cahir, C. Comparing Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing Tools and Their Association with Patient Outcomes. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, L.M.; Raebel, M.A.; Conner, D.A.; Malone, D.C. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: A proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).