Abstract

The recently developed scheduled mobile-telephone referral model (DETELPROG) has achieved especially important results in reducing waiting days for patients, but it has been decided to explore what barriers and positive aspects were detected by both primary care physicians (PCPs) and hospital attending physicians (HAPs) regarding its use. For this, a qualitative descriptive study was carried out through six semi-structured interviews and two focus groups in a sample of eleven PCPs and five HAPs. Interviews were carried out from September 2019 to February 2020. Data were analysed by creating the initial categories, recording the sessions, transcribing the information, by doing a comprehensive reading of the texts obtained, and analysing the contents. The results show that DETELPROG gives the PCP greater prominence as a patient’s health coordinator by improving their relationship and patient safety; it also improves the relationship between PCP and HAP, avoiding unnecessary face-to-face referrals and providing safety to the PCP when making decisions. The barriers for DETELPROG to be used by PCP were defensive medicine, patients’ skepticism in DETELPROG, healthcare burden, and inability to focus on the patient or interpret a sign, symptom, or diagnostic test. For HAP, the barriers were lack of confidence in the PCP and complexity of the patient. As a conclusion, DETELPROG referral model provides a lot of advantages and does not pose any new barrier to face-to-face referral or other non-face-to-face referral models, so it should be implemented in primary care.

1. Introduction

The DETELPROG (“Scheduled Telephone Referral”, from its acronym in Spanish) is a referral model that improves patients’ waiting times and unnecessary commuting with respect to face-to-face referral. It also considerably decreases waiting days for the resolution of the process through which the patient was referred to hospital, avoiding second face-to-face consultation with the hospital physician in almost all cases [1,2]. The evolution of this sophisticated and protocolised health attention model requires greater involvement and prominence of both primary care physicians (PCPs; Médicos de Atención Primaria—Spanish acronym MAP) and hospital attending physicians (HAP; Médicos de Atención Hospitalaria or Internistas—Spanish acronym MI), who should function to support primary care and not as a distinct level of healthcare [3]. Countries with prioritised primary care investments are better prepared to achieve sustainable development goals than those with hospital-centred systems [4]. This need has already been perceived by the Spanish government and the regional government of Andalusia, where our research project is developed, creating two strategic plans to strengthen primary care health attention within the public health system. In this coordination between rural or urban health centres and hospitals, the development of information and communication technologies is fundamental [5,6].

For the coordination between primary care and hospital care, there is strong evidence in favour of electronic referral interventions and interventions that include consultations with specialists prior to referral [7], which improve the problem of waiting lists for specialised consultations that are of so great concern in a large number of developed countries [8,9,10,11], and of course in Spain, where the waiting time average is 88 days [12], being this the main problem perceived by citizens regarding the health system [13]. The information and communication technologies implemented for this need can be classified into secure virtual asynchronous consultation platforms between primary care and hospital care (e-consultation), real-time mobile-phone consultations (curbside consultation), and scheduled mobile-phone or video conferencing consultations.

E-Consultations are platforms that have been widely developed in many countries [7,8,9,10,11,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] with a positive impact on accessibility, avoidance of unnecessary commuting and consultation, waiting times, training of professionals, communication and interprofessional information, acceptability, cost, and satisfaction of patients and professionals, although there are few data on morbidity and mortality [8,14,27].

As barriers, e-consultations require significant technological changes, investment, institutional involvement, leadership, and unpaid work burden for professionals. In addition, there are legal doubts about liability among professionals, occasional delays in receiving responses, and difficulties in monitoring patients and convincing managers and physicians to implement and use, respectively, e-consultation [21,22,26].

On the other hand, real-time mobile-phone consultations (curbside consultation) are a common practice in which benefits are obtained in waiting times, decreased face-to-face appointments in specialised consultation, and patient and professional satisfaction [3]; but also serious communication problems, incomplete or fragmented information, difficulty choosing the colleague to consult, unpredictable interruptions with unscheduled time expense, etc., usually related to the unschedulable aspect of such queries [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Finally, scheduled mobile-phone or videoconferencing consultations have generally been implemented in rural areas where patients have significant accessibility issues to hospital care consultations. In this sense, they are similar to traditional face-to-face consultations regarding clinical efficacy [35], and also share benefits, without sharing barriers, with the above consultation methods [1,2,36]. However, they do require expensive technology and there are still few studies on this matter, especially in the field of psychiatry.

The research team developed the DETELPROG, which achieved very important results in reducing waiting days for patients. However, on the other hand, it is surprising the low utilisation of this new referral model by PCP [1,2]. As a result, it has been decided to explore, through qualitative methodology, what barriers and positive aspects were detected by both PCP and HAP regarding the use of DETELPROG referral with the aim of finding areas of improvement and aspects to enhance in a possible, more widespread implementation in a rural health area or in other related areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

Qualitative descriptive study where a semantic content analysis was performed through six semi-structured interviews and two focus groups.

2.2. Study Population

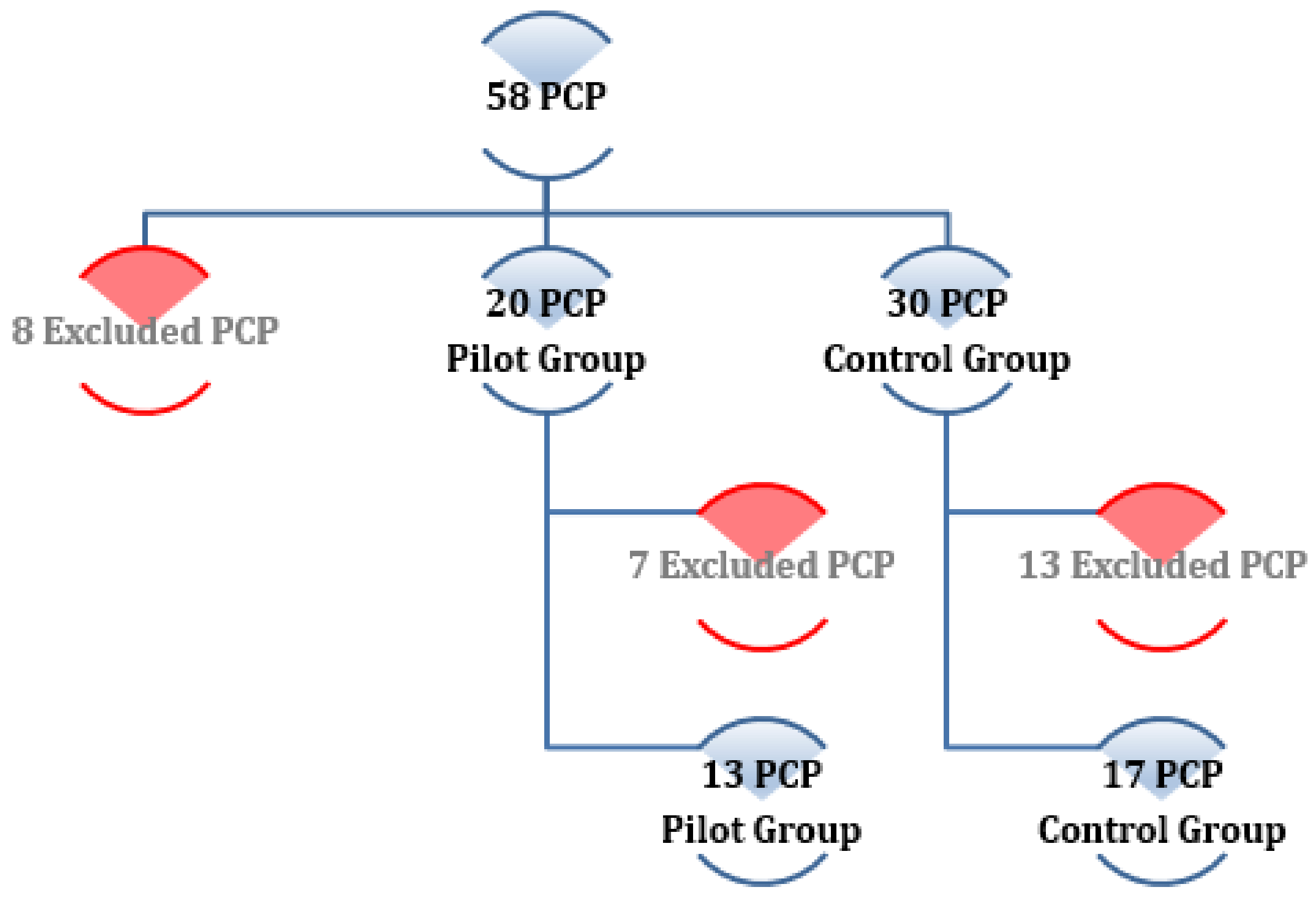

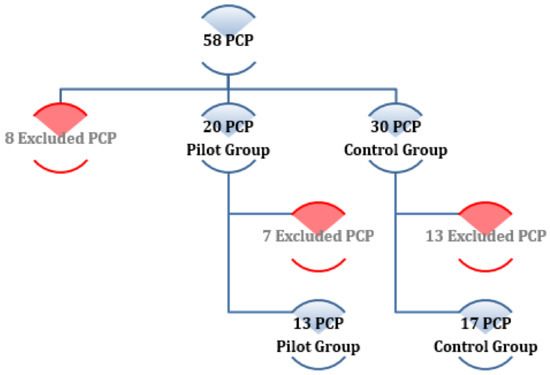

The study population was a finite population made up of the five HAPs who provided consultation at the Rio Tinto hospital (the internal medicine service consists of seven HAPs in total) and the 13 PCP who formed the pilot group of the DETELPROG study [1,2], who had the possibility of receiving or performing scheduled mobile-phone referrals during the study period (there are 58 PCP with medical quota in the health area).

The group of five HAPs was composed of two key informants, who were interviewed through a semi-structured interview, and three HAPs in the focal group. Of the 13 PCP, two of them were discarded from the study because they did not need to perform any referral to internal medicine in either period of the study, resulting in 11 PCPs (two key informants who were interviewed through a semi-structured interview, adding to the nine PCP in the focal group). Figure 1 shows the randomised selection process of PCP at the start of the DETELPROG project [1,2].

Figure 1.

Primary Care Physicians’ sampling selection scheme of the DETELPROG study [1,2]. PCP: Primary Care Physicians.

The sociodemographic variables of the sample are found in Table 1. There were three women and two men in the HAP group, aged between 45 and 67 years (median = 60; mean = 57.4; SD = 9.2). Two of the HAPs had worked as PCPs at the beginning of their working lives. As for the years of work experience, they had worked between 19 and 41 years, with a median of 37 years. With respect to PCPs, six of them were women and seven were men, aged between 37 and 66 years (median = 60; mean = 54.55; SD = 10.76).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of sample.

2.3. Selection of Participants

- Inclusion criteria: Being a finite and accessible population, the study was carried out with all the members of the study population who wished to participate in it.

- Exclusion criteria: those PCP and HAP who did not participate in the DETELPROG study or any referral process.

- Key informants: They are participants who, due to the following characteristics, are interesting enough to have their opinions analysed through a semi-structured interview in a deeper way.

- o

- Key informant PCP 1: the PCP that most rejected DETELPROG (21 rejections of 36 referrals).

- o

- Key informant PCP 2: the PCP that least rejected DETELPRG (0 rejections of 14 referrals).

- o

- Key informant HAP 1 and 2: two HAP who had worked in primary care as PCP years earlier were selected for their dual perspective.

2.4. Data Collection

A focus group was created for PCPs (nine participants) and another one for HAPs (three participants). Subsequently, four semi-structured interviews were done with the key informants, two with the PCP key informants, and two with the HAP key informants. Recordings were made from 3 September 2019, when the PCP focus group was created, to 28 February 2020.

The interviewer-moderator, in all cases, was the main researcher, workmate PCP of all the participants. An observer was also used for nonverbal language annotation for the focus groups.

Prior to the call and with the aim of not disregarding any barriers or benefits detected by the interviewees, researchers agreed to develop an interview script (see Files S1 and S2) asking about DETELPROG’s barriers and benefits as compared to face-to-face referral, at each stage of the interview (from the PCP’s referral to discharge by the HAP), and also taking into account the problems identified in studies on other non-face-to-face referral models found in the literature review.

2.5. Barriers in Data Collection

For the organisation of the PCP focus group, many difficulties arose for the call, but we managed to summon the participants in a restaurant located at equidistant distance from the work centres of the PCPs, and the recording was made at the beginning of the meal.

For the organisation of the HAP focus group, participants preferred to make the recording in the meeting room of their service without any convening problems. The last 5 min were not recorded because the memory of the recorder got full, and it stopped recording. To solve this setback and because both the interviewer and the observer agreed that there was no relevant information in those unrecorded minutes, (the problem was detected within few minutes of finishing the focus group interviews), it was decided not to incorporate anything else into the transcription of the recorded audio.

Individual interviews were conducted without any problems, by appointment, at the place and time proposed by the interviewee.

To perform semantic analyses, the main researcher had to be trained in the use of Nvivo version 12 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and then, train two other members of the group to make a correct triangulation when the time of analysis came. For the agreement, when establishing the final categories, the unanimous agreement was always reached for the designation of the category and for its definition. The agreement was also sought, at least by two of the three researchers, for the encoding of the data and of removed data by the three researchers whenever they considered these not useful.

2.6. Data Analysis

A content analysis of the collected data was carried out. Initially, the categories agreed by the research group and which emerged from the literature review were the following:

- o

- Decision making of the most appropriate type of referral.

- o

- Informed verbal and written consent.

- o

- Technical and programme characteristics for the request of the first appointment.

- o

- Communication with the HAP.

- o

- Technical details (phone, computer, …).

- o

- Interpersonal characteristics (decision making, attitudes, …).

- o

- Patient follow-up.

- o

- PCP-Patient relationship.

- o

- PCP-HAP relationship.

The subsequent process was carried out:

- Recording: interviews and focus groups were recorded in digital format with prior informed consent of the participants.

- Transcript: all recorded data were literally transcribed into a writting computerised processor.

- Comprehensive reading of texts: once the recordings were transcribed, a preliminary reading of these texts was made to correct transcription errors.

- Analysis of the contents: a semantic analysis was carried out in two phases:

- (1)

- Identification of relevant segments of the text (Encoding of transcriptions): Transcripts were encoded by 3 members of the research team, who subsequently agreed on the different categories and their final definitions (Table 2).

Table 2. Final categories.

Table 2. Final categories. - (2)

- Profile analysis: Once the final categories were agreed and all recordings were transcribed, all transcripts were encoded and the transcription content analysis was performed by categories and divided by HAP and PCP profiles, with the help of the Nvivo 12 software (Table 3).

Table 3. Verbatim quote table per categories.

Table 3. Verbatim quote table per categories.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the province of Huelva. In addition, for its randomised clinical trial phase, this project has been registered with clinical trial registration number ACTRN12617001536358.

Prior to the interview, the informed written consent of the participants was requested, and the protection and confidentiality of the information and personal data were guaranteed. The information obtained was treated in such a way that it was not possible to identify the participants. The processing of the data was done in accordance with Organic Law 15/1999 [37] on data protection and Royal Decree 994/1999 [38] on the security of automated files containing personal data.

3. Results

Most participants agreed that DETELPROG offers more prominence to the PCP as a coordinator of patients’ health problems, providing with more problem-solving capacity and allowing greater access to complementary tests, not currently available for PC, thus making the PCP part of the diagnostic and therapeutic decisions made by HAPs.

Comparing DETELPROG with immediate telephone means, PCPs and HAPs complained that immediate telephone means caused lower-quality work burden and information as it was not scheduled; only one PCP considered both means similar. Mailing was considered more impersonal and incomplete because it provided less information than DETELPROG and also offered more indeterminate times. The peace of mind it gives PCP to speak directly to their hospital workmate was greater than via email.

With regard to the overall assessment, for all PCPs, it was a very useful choice for referrals and, in all cases, they would use it on a regular basis if it were implemented. In the case of HAPs, this means was found useful, but with nuances (referral for easy matters, simple patients, request for a clearly indicated complementary test, for certain protocolised pathologies, among others).

On the ethical-legal implications, HAPs had doubts about the legal implications and their degree of legal liability in case of a problem appearing with any patient. In asking PCPs about this issue, they all felt that everyone had the responsibility for what they were doing.

In the preparation of the consultation for PCPs, which was a greater job than for a face-to-face referral, they did not express difficulties or points for improvement. No HAP had made any prior preparation.

All respondents agreed that DETELPROG improved the PCP-HAP relationship, but mostly in the long term, as in the case of this study, it involved few months and, thus, few mobile-phone referrals. As for the physician-patient relationship, there is a dichotomy between the parties: HAPs agreed that, with DETELPROG, the relationship was lost and, on the contrary, for PCPs, the relationship was strengthened.

PCP-HAP-patient communication was considered very positive by all interviewees, but while it is true that the quality and quantity of information was much richer when sharing the patient via DETELPROG than through the traditional paper format of face-to-face referral, the reliability of the information due to the fact that HAPs cannot physically see the patient raises concerns about the possibility of losing important patient data. When agreeing on the complementary tests, treatments, follow-up, reviews etc. to be carried out, there were different attitudes: following the proposals of the PCP, following those of the HAP, or conducting a constructive discussion between both physicians and the patient. In this regard, all the interviewees expressed enormous satisfaction in this regard, and there was always agreement between the parties, with the exception of a single occasion.

With regard to quantitative improvements in waiting times and decreased commuting, everyone was aware and highlighted them.

Regarding organisational characteristics, some participants complained about the lack of personal knowledge between PCPs and HAPs, that sometimes questioned the reliability of information and hindered understanding among physicians. The most permanent cited barrier was the schedule for phoning consultations, which were scheduled amid face-to-face consultations, and sometimes there were delays in HAPs responding to the PCPs because they were busy with an in-person patient in the consultation, something which also delayed PCPs and made HAPs uncomfortable for having their colleague waiting. The 15 min for DETELPROG were appropriate for the interviewees. It is also important to note that two HAP missed previous protocols to consider what type of patients to refer via DETELPROG and how to do so to make it faster and more operational.

For PCPs, it implied a work overburden, although it did not cause them a problem, as it was scheduled. For the HAPs, there was no overburden. There were no technical problems during DETELPROG when PCPs and HAPs were asked about them.

There was consensus that patients who were highly oriented by the PCPs and who clearly needed a specific test which was not accessible to PCPs clearly benefited from DETELPROG. However, as causes of rejection, the HAP focus group mentioned three scenarios: cases by not-well-oriented the PCP, mistrust in data exposed by the PCP, or because they did not find the PCP sufficiently trained to deal with the patient. In those cases, they requested an in-person consultation and started requesting some tests in advance. For one key HAP, there were no limitations except for the exclusion criteria from the study, and for the other one, this was not a suitable type of referral for complex patients, unless it was a patient already known to them. PCPs individually expressed that this means would not be indicated for patients who show a sign, symptom, or have a complementary test that they cannot interpret on their own or focus on it. Sometimes, defensive medicine is the cause of rejection. Also noted, as expressed by Key informant PCP 1, was the usual healthcare burden suffered by PCPs, which causes, in times of burden, to request a face-to-face referral, and which involves less workload. Table 4 shows the main topics where PCPs and HAPs coincide or differ, according to the study categories. Table 5 shows the proposals for improvement made by respondents for 6 of the barriers identified by themselves.

Table 4.

Main points of agreement and disagreement between the PCPs and the HAPs related to barriers and benefits of a telephone referral model.

Table 5.

Proposals for improvements for the detected barriers.

4. Discussion

DETELPROG has provided a reduction in patient commuting to hospital and an improvement in waiting times for a first consultation in internal medicine and for the resolution of the health problem for which the patient was referred [1,2]. In addition, it has been a very positive experience for both PCPs and HAPs and has given PCPs a more leading role as a manager of the healthcare of their patients [4], not only at the primary care level, but also in patients who need management from external hospital consultations. It has also provided PCPs with the ability to obtain complementary tests and treatments for their patients in an agile and consensual way with their hospital colleagues, for which they did not have independent access.

As fundamental advantages with respect to face-to-face referral, as well as e-consultation [21,22,26] and curbside consultation [3,39,40], DETELPROG has decreased waiting times, avoided unnecessary consultations, and improved the quality of face-to-face referrals and medical actions (diagnosis and treatment) by sharing the patient among physicians of both levels of care, thus improving the relationship between physicians, the PCP-patient relationship, and the satisfaction of all parties involved.

With regard to barriers, like e-consultation [21,22,26] and curbside consultation [3,33,40,41], the barriers that HAP noted the most were the loss of direct contact with the patients, which they cannot explore and have to rely on the information provided by the health centre physician, whom they often do not know. Nor are HAPs clear about the ethical-legal implications of their advice on a mobile-phone consultation where they do not physically see the patient, or the implications with respect to informed consent for some complementary tests whose requests they sign without verbally informing patients and having to delegate this essential activity to the PCPs, as is the case in the other models of non-in-person referral.

As compared with previous studies, DETELPROG avoids unnecessary face-to-face consultations, does not cause an overburden in physicians, does not require the implementation of new technologies, and improves specialised care response times, although response times are longer than with non-face models. Previous studies showed that the use of care protocols of healthcare phone calls on the part of receptionists, while trained to operate booking systems, is not effective for fully assessing and managing patients. Under these circumstances, face-to-face consultations looks more efficient than repeating a phone call. For this, immediate information offered by both physicians and nurses while the caller is still on the telephone can dramatically reduce the number of such contacts. In fact, the presence of a nurse acts as an effective filter under these conditions [42]. The same explanation can be offered for the decrease in hospital admissions observed during intervention periods. The literature contrasts with the present research when observing the experience from a triage telephone system that included general practitioners and primary care nurses. This study not only showed a decrease in work overload thanks to telephone consultations, but there were even more consultations, yet distributed among the health centre staff to find prompt and efficient assistance. So, the cost of the used resources did not vary with respect to regular consultations, but users did show their satisfaction for having been assisted on the same day of the consultation [43].

As it is a synchronous oral communication, the information transmitted in the three-way call between both physicians and the patient is of higher quality, more adapted to the needs of all the parties involved, more reliable, and richer, resulting in closer collaboration between physicians that makes the PCPs feel more supported when making diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Moreover, it does not require any extraordinary investment since all that was needed was a reorganisation of the services involved [21,22,26]. In addition, it avoided communication problems, incomplete or fragmented data, difficulty in choosing the professional colleague to consult, unpredictable interruptions with unscheduled time spent, etc., typical of immediate telephone consultations [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

As for videoconferencing consultations, there is little data on their advantages and barriers beyond the field of psychiatry. Yet, it is possible to say that DETELPROG does not require technology for videoconferencing.

With respect to the Quadruple Goal to optimise health systems [44], it is considered to be a system that improves the health of the population by decreasing waiting times, which also improves diagnoses and treatments by being agreed by the three parties involved (PCP, HAP and patient), and optimises face-to-face referrals avoiding unnecessary ones. In this sense, there is an improvement in the cost of delays in waiting times and regarding the poor communication that exists in face-to-face referral between physicians (need to repeat complementary tests, repeat therapies, need for more complex therapies to have more evolved frames for longer waiting times, etc.), while, at the same time, lowering the costs for patients by not having to commute to the hospital. Likewise, it improves the satisfaction of medical professionals and, presumably, of the patients who receive the service, as has been manifested by the professionals themselves.

As limitations, DETELPROG is not considered to be a substitution, but a complementary model to face-to-face referral which can accelerate diagnosis and treatment but would not be indicated for patients who are not well oriented by PCPs, for patients who prefer a face-to-face referral, or for patients where the PCP has serious diagnostic doubts or lack of the necessary therapeutic resources. In this last case, DETELPROG may provide appropriate advice, while the in-person appointment, or an advance of such appointment, arrives. The usual care overburden of PCPs may be another limitation causing PCPs to opt, in high-pressure situations, for face-to-face referral in which they discharge responsibility for the study and follow-up of the patient in their hospital colleagues. Despite the high rejection rate by PCP (47%), PCPs express great satisfaction with DETELPROG and do not state important causes of rejection (defensive medicine, healthcare pressure, and the inability to orient the patient or interpret a sign, symptom, or complementary test).

The creation of two focal groups and six semi-structured interviews on a small sample (total of 16 professionals) could be regarded as limiting, but information was obtained from all the physicians who had participated in any DETELPROG and, though with several different nuances, the opinions were quite similar for each of both profiles so, though a bigger sample could add other data, we believe the sample size to be enough to obtain reliable results about the main barriers and benefits of the model.

As points for improvement, we believe that the organisation of regular meetings between physicians at both levels of care, as well as improving the time flexibility for mobile-phone consultation and having clearly stated, and in writing, the ethical-legal implications and a consensus document for monitoring patients with a predominant role of the PCP would be appropriate. It is considered appropriate to incorporate all these proposals, although in the case of implementing specific protocols we believe that it is an appropriate measure for all types of referrals and not specifically for DETELPROG.

5. Conclusions

DETELPROG is a referral model [1,2] that, besides reducing waiting days for patients and avoiding unnecessary commuting for hospital face-to-face consultations, with the associated benefits and, above all, in periods of pandemics such as the one we are facing now, implies a positive experience for those involved, giving PCPs a more prominent role. Also, it avoids the barriers associated to the lack of programmability of curbside consultations [28,29,30,31,32,33,34] and, as compared to e-consultations [21,22,26], improves the quality of the assistance received and of the information provided to HAPs, the relationship between primary care physicians and hospital attending physicians, and the costs are null. Thus, we consider it an ideal referral model to be used initially, leaving face-to-face referral for those cases agreed by both physicians via DETELPROG, which would imply an optimisation of the health resources, offering a more appropriate assistance to patients by avoiding unnecessary commuting to hospitals, with the associated risks, and without implying any cost.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18105280/s1, File S1. Focus group script PCP-HAP; File S2. Interviews script PCP-HAP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Data curation, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Formal analysis, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Investigation, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Methodology, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Project administration, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Resources, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Software, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Supervision, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G-.S. and E.M.M.-S.; Validation, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Visualization, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Writing—original draft, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S.; Writing—review & editing, L.M.A.-L., V.C.-V., J.J.P.-L., J.G.-S. and E.M.M.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the province of Huelva.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All of this article is provided within the manuscript and its artwork. In addition, for its randomised clinical trial phase, this project has been registered with clinical trial registration number ACTRN12617001536358.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Azogil-López, L.M.; Pérez-Lázaro, J.J.; Ávila-Pecci, P.; Medrano-Sánchez, E.M.; Coronado-Vázquez, M.V. Effectiveness of a new model of telephone derivation shared between primary care and hospital care. Aten Primaria 2018, 51, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azogil-López, L.M.; Pérez-Lázaro, J.J.; Medrano-Sánchez, E.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Coronado-Vázquez, V. DETELPROG Study. Effectiveness of a New Model of Scheduled Telephone Referral from Primary Care to Internal Medicine. A Randomised Controlled Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 688. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D.A.; Sorensen, K.J.; Wilkinson, J.M.; Berger, R.A. Barriers and Decisions When Answering Clinical Questions at the Point of Care. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1962–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hone, T.; Macinko, J.; Millett, C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: What is the role of primary health care in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Lancet 2018, 392, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. Plan de Renovación de la Atención Primaria en Andalucía. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/sobre-junta/planes/detalle/94610.html (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Bienestar Social. Marco Estratégico para la Atención Primaria y Comunitaria. 2019. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/proyectosActividades/docs/Marco_Estrategico_APS_25Abril_2019.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Blank, L.; Baxter, S.; Woods, H.B.; Goyder, E.; Lee, A.; Payne, N.; Rimmer, M. Referral interventions from primary to specialist care: A systematic review of international evidence. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, e765–e774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; Drosinis, P.; Keely, E. Electronic consultation systems: Worldwide prevalence and their impact on patient care—A systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2016, 33, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; Moroz, I.; Afkham, A.; Keely, E. Sustainability of a Primary Care–Driven eConsult Service. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018, 16, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, K.; Catschegn, S.; Cruz, M.; Gleason, N.; Gonzales, R. Analysis of an electronic consultation program at an academic medical centre: Primary care provider questions, specialist responses, and primary care provider actions. J. Telemed. Telecare 2016, 23, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naseriasl, M.; Adham, D.; Janati, A. E-referral Solutions: Successful Experiences, Key Features and Challenges—A Systematic Review. Mater. Soc. Med. 2015, 27, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Sistema de Información de Listas de Espera del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Indicadores resumen [Internet]. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/listaEspera.htm (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Opinión de los Ciudadanos. Barómetro Sanitario. 2018. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/BarometroSanitario/home_BS.htm (accessed on 18 October 2020).

- Tuot, D.S.; Liddy, C.; Vimalananda, V.G.; Pecina, J.; Murphy, E.J.; Keely, E.; Simon, S.R.; North, F.; Orlander, J.D.; Chen, A.H. Evaluating diverse electronic consultation programs with a common framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liddy, C.; Drosinis, P.; Fogel, A.; Keely, E. Prevention of delayed referrals through the Champlain BASE eConsult service. Can. Fam. Phys. Med. Fam. Can. 2017, 63, e381–e386. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, F.; Posner, G.; Afkham, A.; Liddy, C.; Keely, E. Evaluation of an Electronic Consultation Service in Obstetrics and Gynecology in Ontario. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; Drosinis, P.; Deri Armstrong, C.; McKellips, F.; Afkham, A.; Keely, E. What are the cost savings associated with providing access to specialist care through the Champlain BASE eConsult service? A costing evaluation. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keely, E.; Drosinis, P.; Afkham, A.; Liddy, C. Perspectives of Champlain BASE Specialist Physicians: Their Motivation, Experiences and Recommendations for Providing eConsultations to Primary Care Providers. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2015, 209, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liddy, C.; Afkham, A.; Drosinis, P.; Joschko, J.; Keely, E. Impact of and Satisfaction with a New eConsult Service: A Mixed Methods Study of Primary Care Providers. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2015, 28, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalananda, V.G.; Gupte, G.; Seraj, S.M.; Orlander, J.; Berlowitz, D.; Fincke, B.G.; Simon, S.R. Electronic consultations (e-consults) to improve access to specialty care: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuot, D.S.; Leeds, K.; Murphy, E.J.; Sarkar, U.; Lyles, C.R.; Mekonnen, T.; Chen, A.H.M. Facilitators and barriers to implementing electronic referral and/or consultation systems: A qualitative study of 16 health organizations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Osman, M.; Schick-Makaroff, K.; Thompson, S.; Featherstone, R.; Bialy, L.; Kurzawa, J.; Okpechi, I.G.; Habib, S.; Shojai, S.; Jindal, K.; et al. Barriers and facilitators for implementation of electronic consultations (eConsult) to enhance specialist access to care: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Velden, T.; Schalk, B.W.M.; Harmsen, M.; Adriaansens, G.; Schermer, T.R.; Ten Dam, M.A. Implementation of web-based hospital specialist consultations to improve quality and expediency of general practitioners’ care: A feasibility study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, J.N.; Potapov, A.; Gordon, A.; Jurado, J.; Magana, C.; Knox, M.; Tuot, D. Electronic consultation impact from the primary care clinician perspective: Outcomes from a national sample. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keely, E.; Williams, R.; Epstein, G.; Afkham, A.; Liddy, C. Specialist Perspectives on Ontario Provincial Electronic Consultation Services. Telemed. e-Health 2019, 25, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joschko, J.; Keely, E.; Grant, R.; Moroz, I.; Graveline, M.; Drimer, N.; Liddy, C. Electronic Consultation Services Worldwide: Environmental Scan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; Moroz, I.; Mihan, A.; Nawar, N.; Keely, E. A Systematic Review of Asynchronous, Provider-to-Provider, Electronic Consultation Services to Improve Access to Specialty Care Available Worldwide. Telemed. e-Health 2019, 25, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, M.; Sarcone, E.; Keniston, A.; Statland, B.; Taub, J.A.; Allyn, R.L.; Reid, M.B.; Cervantes, L.; Frank, M.G.; Scaletta, N.; et al. Prospective comparison of curbside versus formal consultations. J. Hosp. Med. 2013, 8, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Sorensen, K.J.; Wilkinson, J.M. Value and Process of Curbside Consultations in Clinical Practice: A Grounded Theory Study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denes, E.; Pinet, P.; Cypierre, A.; Durox, H.; Ducroix-Roubertou, S.; Genet, C.; Weinbreck, P. Spectrum of advice and curbside consultations of infectious diseases specialists. Méd. Maladies Infect. 2014, 44, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarcone, E.; Stella, S.A.; Allyn, R. Curbside consultations: A call for more investigation into a common practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1589–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Sorensen, K.J.; Wilkinson, J.M. In reply—Curbside consultations: A call for more investigation into a common practice. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, A.; Lingard, L. A qualitative study examining tensions in interdoctor telephone consultations. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Mazowita, G.; Ignaszewski, A.; Levin, A.; Barber, C.; Thompson, D.; Barr, S.; Lear, S.; Levy, R.D. Family physician access to specialist advice by telephone: Reduction in unnecessary specialist consultations and emergency department visits. Can. Fam. Phys. Med. Fam. Can. 2016, 62, e668–e676. [Google Scholar]

- Fortney, J.C.; Pyne, J.M.; Turner, E.E.; Farris, K.M.; Normoyle, T.M.; Avery, M.D.; Hilty, D.M.; Unützer, J. Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, A.M.; Lindberg, I.; Söderberg, S. Healthcare personnel’s experiences using video consultation in primary healthcare in rural areas. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2016, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de la Presidencia del gobierno de España. BOE.es—BOE-A-1999-23750 Ley Orgánica 15/1999, de 13 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos de Carácter Personal. [Internet]. Boletin oficial del estado. 1999. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1999-23750 (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Ministerio de la Presidencia del gobierno de España. BOE.es—BOE-A-1999-13967 Real Decreto 994/1999, de 11 de junio, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de medidas de seguridad de los ficheros automatizados que contengan datos de carácter personal. [Internet]. Boletin oficial del estado. 1999. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1999-13967 (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Myers, J.P. Curbside Consultation in Infectious Diseases: A Prospective Study. J. Infect. Dis. 1984, 150, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, D.; Gifford, D.R.; Stein, M.D. Curbside Consultation Practices and Attitudes Among Primary Care Physicians and Medical Subspecialists. JAMA 1998, 280, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappolt, S. Family physicians’ selection of informal peer consultants: Implications for continuing education. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2002, 22, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattimer, V.; George, S.; Thompson, F.; Thomas, E.; Mullee, M.; Turnbull, J.; Smith, H.; Moore, M.; Bond, H.; Glasper, A. Safety and effectiveness of nurse telephone consultation in out of hours primary care: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1998, 317, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.L.; Fletcher, E.; Britten, N.; Green, C.; A Holt, T.; Lattimer, V.; Richards, D.; Richards, S.H.; Salisbury, C.; Calitri, R.; et al. Telephone triage for management of same-day consultation requests in general practice (the ESTEEM trial): A cluster-randomised controlled trial and cost-consequence analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 1859–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).