In our recently published meta-analysis, due to an oversight, we treated urinary As concentration data reported by Tsinovoi et al. [1] instead as drinking water As data. This oversight impacted, in minor way, our linear and non-linear published dose-response models for combined fatal and non-fatal strokes. The oversight does not impact, in any way, any of our other published [2] dose-response models.

We corrected both Table 1 and Supplementary Materials Table S1; the exposure media for Tsinovoi et al. [1] is changed to ‘urinary As (µg/g creatinine)’ from ‘water As (µg/L)’. Accordingly, we modified dose-response models (Table 2) and goodness of fit parameters (Table 3) for the relationships between drinking water As and combined fatal and non-fatal risks of strokes in the corrected Manuscript [2]. These are based on using Equation (3) of Xu et al. [2] to calculate equivalent drinking water As concentrations from the reported urinary As values from Tsinovoi et al. [1]. Over the drinking water arsenic concentration range 1 to 50 µg/L, the absolute differences between the originally published and corrected relative risks (RR) for the linear and non-linear dose-response models for combined fatal and non-fatal stroke risks are all < 0.001 and < 0.020 respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included for dose-response meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Pooled relative risks (95% CIs) for different types of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and clinic markers in relation to water arsenic concentrations.

Table 3.

Goodness-of-fit assessment.

We also made the required corrections in Figure 1 and Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S2, although these are almost identical to the original figures.

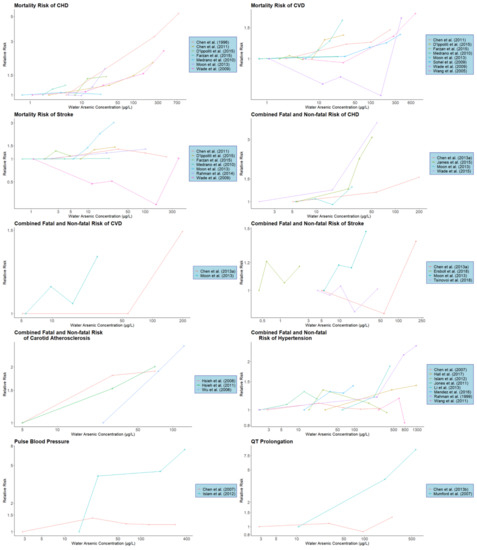

Figure 1.

Individual study dose-response characteristics for various CVD subtypes or biomarkers. Arsenic concentrations refer to the observed or estimated median arsenic concentrations for the given concentration category. Lines connect the dose-response data for each study and are for illustrative purposes only (CVD: cardiovascular disease; CHD: coronary heart disease).

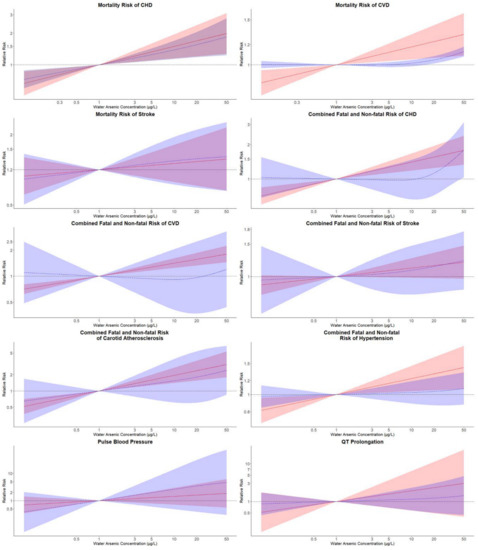

Figure 2.

Pooled log-linear and non-linear relative risks and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of different CVD endpoints in relation to the estimated drinking water arsenic concentration. Pooled log-linear and non-linear relative risks of CVD endpoints were estimated for drinking water arsenic concentrations with reference to an arsenic concentration of 1 µg/L. Solid lines (red) correspond to pooled relative risks of linear models with their 95% CIs represented as shaded regions (red). Pooled relative risks of non-linear models were represented by long-dash lines (blue) and their 95% CIs were plotted as shaded areas (blue). Log-linear models were estimated with log-transformed estimated drinking water arsenic concentration and non-linear associations were estimated from models with restricted cubic splines of log-transformed water arsenic concentration with knots at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles of log-transformed water arsenic (CVD: cardiovascular disease; CHD: coronary heart disease).

Lastly, we note that the corrections to the linear and non-linear dose-response models for combined fatal and non-fatal risks of strokes as a function of drinking water arsenic concentration show the same trends as in the original publication and, in particular, over the relatively low concentration range in the scope of the study, there remains no significant association in the data collated between drinking water As concentration and the combined fatal and non-fatal risks of stroke.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/23/8947/s1, Figure S1: Flow diagram of study selection procedure, Figure S2: Association of CVD endpoints with drinking water arsenic concentrations, Figure S3: Funnel Plots for the analysis of publication bias, Table S1: Epidemiological studies of arsenic (As) exposure and cardiovascular disease (CVD) included in the systematic review, Table S2: Egger’s regression test of funnel plot asymmetry, Table S3: Pooled relative risks (95% confidence intervals) for different CVD types and clinical markers in relation to drinking water arsenic concentrations with the exclusion of studies which do provide drinking water As concentrations directly, Table S4: Pooled relative risks (95% confidence intervals) for different CVD types and CVD markers in relation to drinking water arsenic concentrations lower than 100 ppb.

Funding

LX was funded by the University of Manchester.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Matt Gribbins (Emory University) for drawing this error to our attention.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Tsinovoi, C.L.; Xun, P.C.; McClure, L.A.; Carioni, V.M.O.; Brockman, J.D.; Cai, J.W.; Guallar, E.; Cushman, M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Howard, V.J.; et al. Arsenic exposure in relation to ischemic stroke the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study. Stroke 2018, 49, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Mondal, D.; Polya, D.A. Positive association of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with chronic exposure to drinking water Arsenic (As) at concentrations below the WHO provisional guideline value: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).