Facilitators and Inhibitors of Lifestyle Modification and Maintenance of KOREAN Postmenopausal Women: Revealing Conversations from FOCUS Group Interview

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

- Introductory (5 min): “How have you been doing since you completed the program?”

- Transition (5 min): “What did it mean to you to maintain healthy lifestyles during your participation in the program or your daily life after the program was over?”

- Main (45 min): “Please talk freely about any factors that helped or hindered you from applying and maintaining healthy lifestyle modifications in daily life”.

- Concluding (5 min): “Here is what you have told me so far. Is there anything missing that I should include? Is there anything else you would like to talk about?”

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethical Consideration

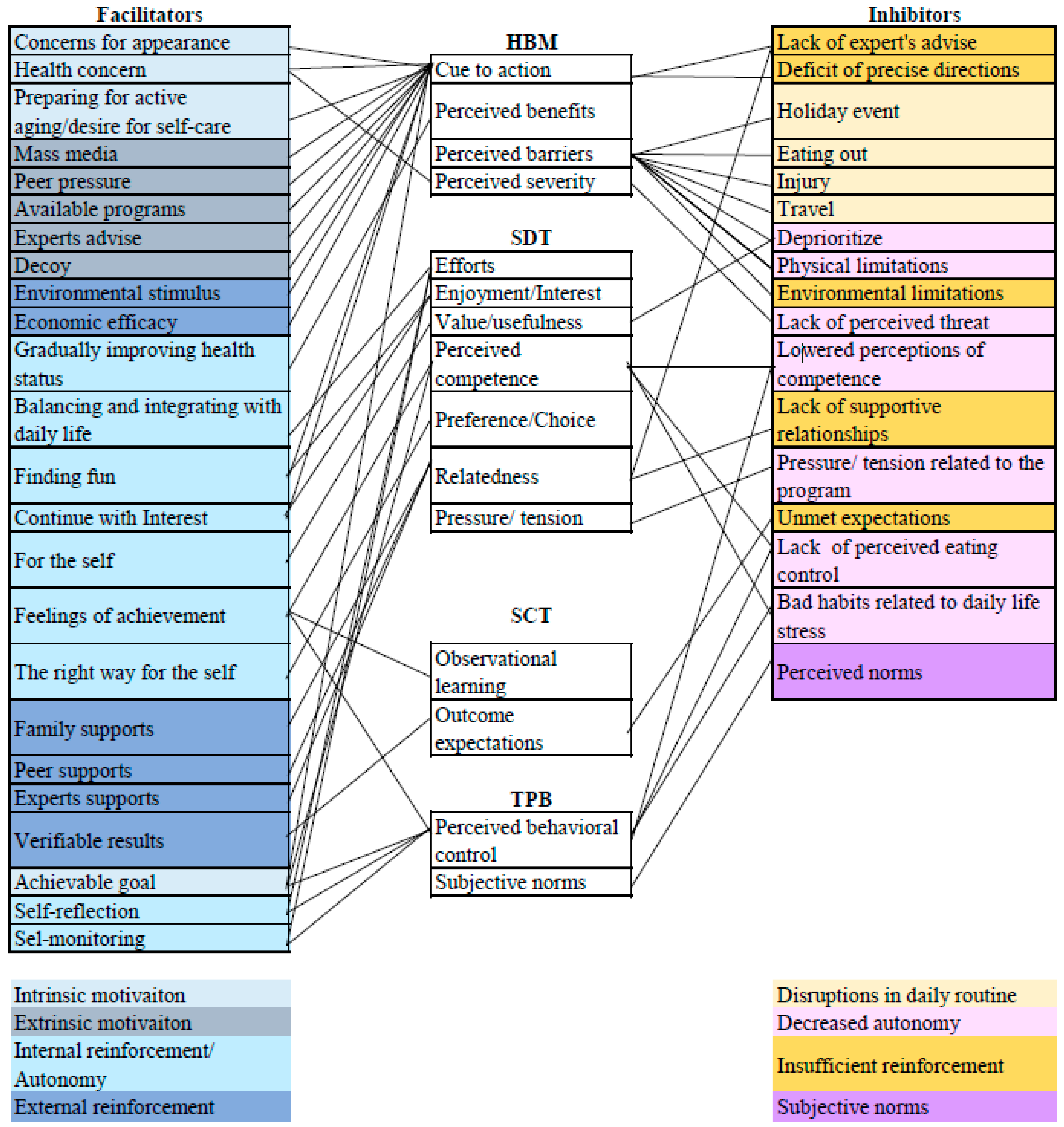

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Codes, Themes, and Subthemes

3.2.1. Taking a Step toward Healthy Behavior Maintenance Using Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivational Factors

I worked out because I was desperate. I have to wear tight clothes when riding a bike. That way, when I see myself, I could see how my fat bulges out on my front and back (FGI1-PM52807).

I reached menopause when I was 56. My weight gradually and continuously increased from that time on. Day after day, I would keep breaking the record. I felt quite miserable as I could no longer fit into nice clothes (FGI2-PM52808).

I think the desperate desire to get healthy after falling sick is more important. I found myself working harder to maintain a healthy lifestyle after I became sick (FGI3-PM51903).

This time, I felt the desperate need to not gain any more weight and not let my sugar levels rise since my weight had been continuously increasing. I worked out very hard after I started participating in this program. I began to lose weight as a result… (FGI2-PM52404)

We are aware that whereas people in our generation take care of our parents, people in the current generation would never do such a thing. We need to stay healthy to be able to take care of ourselves instead of being taken care of by our children. The idea that I need to take care of my own health seems to motivate me (FGI4-PM52305).

Whenever I eat, I would tell myself it’s not right as a parent to make my children feel worried. I’ve been trying to resist unhealthy food and eat something healthier (FGI3-PM52601).

I think it would be easy if I have a goal. I once got rid of hypertension by exercising. I started participating in the program hoping to reduce my medication use if not completely stop it, with that goal in mind… or the goal to lose weight… I don’t want to regain the weight that I lost (FGI3-PM51903).

3.2.2. Lifestyle Rebalancing under the Self-Regulation Employing Internal and External Reinforcement

Even on a hot summer day, even when it was raining, I made sure to walk on Wednesdays since Wednesdays were set as the “Walking Day”. On rainy days, the three of us would be walking in white raincoats (laughing). It was fun too. Walking was an extra source of fun aside from volunteering on Wednesdays. I had a lot of fun losing weight this summer (FGI2-PM52905).

The reason why I am extending my participation is that I determined to increase my muscle mass for the next three months. I got curious about how much effort would be needed to gain how much muscle mass. Now that I can check my muscle mass on my own… (FGI2-PM52404).

It’s for me… It’s not for others. Even if I feel lazy, I still need to do it because it’s for myself. I think I did it just as how we live through our daily life (FGI4-PM53001).

I enjoy walking, so walking seems to work best for me. Everyone has a different method that works for them. To me, it was walking (FGI4-PM53001).

I would exercise early in the morning, but some days, I feel tempted to just go home and sleep more. But once I beat that temptation and come back home after completing my exercise, I can start my day in a good mood (FGI2- PM52905).

I started out by walking. I noticed others were also walking. Once, a young person was jogging not too fast like this, and I tried to do the same, and it worked (FGI4- PM51602).

I wouldn’t call what I did an exercise, but whenever I had some free time during daily life, or there was sufficient time between one schedule and another, I would walk instead of taking the subway. I would walk around an hour this way (FGI1-PM52807).

I forced myself to do what I didn’t want to do and walked 10,000 steps once per week. I tried to walk over 10,000 steps within a week or walk at least one hour per day. Although I am doing the same thing over and over, it is hard to keep the habit of walking. I think being consistent is challenging. But over time, I slowly got used to walking (FGI2-PM52405).

Since I needed to fill out the checklist… I didn’t want to leave too many checkboxes empty, so I tried my best (FGI1-PM52801).

I already knew that my lifestyle was blamed to be fat. But when I checked one by one in this program, it seems clear that I was getting fat because of things that I should have changed (FGI2-PM52405.)

Seeing numerical improvements helped me understand my progress and motivated me to work harder (FGI4-PM53001).

Since I knew precise results would come out after a few months, I worked harder to achieve better results. When there are no accurate data to show your progress, you tend to slack off even if you were determined in the beginning. Now, I think about how my cholesterol levels would change in a blood test a few months later and am careful about what I eat (FGI2-PM52808).

3.2.3. Failure to Integrate Healthy Habits into a Lifestyle

My thyroid conditions make me feel weak and lethargic. I keep skipping exercises by making excuses about my thyroid conditions. It’s actually difficult for me to move. You know what I mean… I feel very tired and crave sweets. I gained two kilograms as a result, and it’s been hard to lose the gained weight (FGI3-PM52805).

I do think that I need to work out, but the busy schedule I set for myself keeps me from working out (FGI3-PM52303).

I feel so pathetic and depressed. I would try but failed. I would see how weak-willed I am and feel unenergetic. And then again, I would tell myself to try again. Even then, I’d still feel unenergetic for a long time. I’m so pathetic (FGI4-PM51602).

I love sweets. My head tells me not to eat them, but once I see them, I can’t help it. I think that’s the problem (FGI4-PM52004).

I spend a lot of my time with kids, and I love eating. I can’t help but eat some of my kids’ snacks… I think I felt stressed about having my alone time taken away by the kids and tried to cope with the stress by eating, which resulted in my weight gain (FGI2-PM52905).

To me, the pressure to keep up was very stressful. I felt like if I didn’t keep up, I would fall behind everyone else. Having to fill out the self-check list on the computer according to the schedule was too much for me, so I just gave up (FGI3-PM61903).

3.2.4. Inappropriate Supportive Strategy

I didn’t want to hike alone, so I just didn’t go hiking. My blood pressure started rising again after I stopped hiking (FGI3-PM51903).

I had fun exercising during the program, but I couldn’t get myself to exercise alone at home (FGI1-PM52601).

You know how you feel when your results do not reach your expectations. When we were young, we would eat a lot but if you exercise one day, you’d see the effect of it the next day. Now, even after three or four days, we don’t see any improvements because we’re old. Since we’re not seeing immediate improvements, it’s harder to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Seeing even just a small improvement would motivate us but without seeing any improvement, we can’t get ourselves to it (FGI4-PM52004).

I was hopeful that since doing I was something that I never used to do, I would see drastic improvements, but that was not the case… and it made me skeptical. Since there were no immediate improvements… (FGI4-PM52004).

I used to go to the gym to ride a bike machine and run on a treadmill, but the air inside the gym felt so suffocating. I ended up not going to the gym often… (FGI1-PM52801).

When it’s raining heavily, I don’t go out. When there’s no one outside, it’s scary. The Han River is bustling with people even after midnight. At the Ttukseom Park, you can go out any time to exercise, but even there, it’s scary when it’s rainy and dark with no people around… (FGI1-PM52101).

What I really hate is when a friend brings brown rice to our hangout session because she’s on a diet. I hate that! She shouldn’t have come! Her doing that really breaks the atmosphere. I get that she’s strong-willed and may later be successful with weight loss, but I let myself eat when we’re hanging out. I guess it’s just different opinions, but people like her ruin my mood. How can you bring a lunch like that? I just let myself loose when we’re hanging out and eat to my heart’s content. That’s why I have all this fat (FGI3-PM52306).

I felt so weak after I lost around one kilogram. I told my friends I felt weak, and my friends told me, “Hey, it’s because you lost weight. Just eat” (laughing). They told me that “people who eat well” look well and that when you lose weight at our age, you are bound to feel weak (FGI2-PM52808).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El Khoudary, S.R.; Greendale, G.; Crawford, S.L.; Avis, N.E.; Brooks, M.M.; Thurston, R.C.; Karvonen-Gutierrez, C.; Waetjen, L.E.; Matthews, K. The menopause transition and women’s health at midlife: A progress report from the study of women’s health across the nation (swan). Menopause 2019, 26, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, E.O.; Choe, M.A. Korean women’s attitudes toward physical activity. Res. Nurs. Health 2004, 27, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shufelt, C.L.; Pacheco, C.; Tweet, M.S.; Miller, V.M. Sex-specific physiology and cardiovascular disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1065, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.; Mulvagh, S.L.; Merz, C.N.B.; Buring, J.E.; Manson, J.E. Cardiovascular disease in women: Clinical perspectives. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1273–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Snetselaar, L.G.; Wallace, R.B.; Caan, B.J.; Rohan, T.E.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Shadyab, A.H.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Manson, J.E. Association of normal-weight central obesity with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among postmenopausal women. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e197337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renehan, A.G.; Howell, A. Preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. Lancet 2005, 365, 1449–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubert, K.A.; Clark, N.G.; Smith, R.A. Patient-centered prevention strategies for cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2007, 4, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, E.; Collazo-Clavell, M.L.; Faubion, S.S. Weight gain in women at midlife: A concise review of the pathophysiology and strategies for management. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimlou, V.; Charandabi, S.M.-A.; Malakouti, J.; Mirghafourvand, M. Effect of counselling on health-promoting lifestyle and the quality of life in iranian middle-aged women: A randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; Lindholm, L.; Norberg, M.; Schoffer, O.; Klug, S.J.; Norström, F. The cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting lifestyle change for the prevention of diabetes in a swedish primary care and community based prevention program. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdipour, N.; Shahnazi, H.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Sharifirad, G. The effect of educational intervention on health promoting lifestyle: Focusing on middle-aged women. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2015, 4, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, H.S. Autonomy-supportive, web-based lifestyle modification for cardiometabolic risk in postmenopausal women: Randomized trial. Nurs. Health Sci. 2017, 19, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreidieh, D.; Itani, L.; El Kassas, G.; El Masri, D.; Calugi, S.; Dalle Grave, R.; El Ghoch, M. Long-term lifestyle-modification programs for overweight and obesity management in the arab states: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2018, 14, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollosa, D.N.; Holliday, E.; Hure, A.; Tavener, M.; James, E.L. A 15-year follow-up study on long-term adherence to health behaviour recommendations in women diagnosed with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 182, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, H.; Moradi, R.; Kazemi, A.; Shahshahani, M.S. Determinants of physical activity in middle-aged woman in isfahan using the health belief model. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, D.K.; Huberty, J.L. Middle-aged women’s preferred theory-based features in mobile physical activity applications. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, J.K.; Murray, T.C.; Johnson, S.T.; Elavsky, S. Understanding physical activity intentions and behavior in postmenopausal women: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 18, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.-J.; Kim, H.-S. Applying the modified health belief model (HBM) to korean medical tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Liu, W.C.; Kee, Y.H.; Chian, L.K. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness in the classroom: Understanding students’ motivational processes using the self-determination theory. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the theory of planned behavior in environmental science: A comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyibo, K.; Adaji, I.; Vassileva, J. Social cognitive determinants of exercise behavior in the context of behavior modeling: A mixed method approach. Digit. Health 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.S.; Chung, M.J.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, D.M.; Lee, D.W. An analysis of articles for health promotion behaviors of korean middle-aged. J. Korean Acad. Commun. Health Nurs. 2009, 20, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Annesi, J.J. Mediation of the relationship of behavioural treatment type and changes in psychological predictors of healthy eating by body satisfaction changes in women with obesity. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Zeidi, B.; Kariman, N.; Kashi, Z.; Mohammadi Zeidi, I.; Alavi Majd, H. Predictors of physical activity following gestational diabetes: Application of health action process approach. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metzgar, C.J.; Preston, A.G.; Miller, D.L.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Facilitators and barriers to weight loss and weight loss maintenance: A qualitative exploration. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2015, 28, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samdal, G.B.; Eide, G.E.; Barth, T.; Williams, G.; Meland, E. Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barragan, R.; Rubio, L.; Portoles, O.; Asensio, E.M.; Ortega, C.; Sorlí, J.V.; Corella, D. Qualitative study of the differences between men and women’s perception of obesity, its causes, tackling and repercussions on health. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K.C.; Valentiner, L.S.; Langberg, H. Motivational factors for initiating, implementing, and maintaining physical activity behavior following a rehabilitation program for patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal, qualitative, interview study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevild, C.H.; Niemiec, C.P.; Bru, L.E.; Dyrstad, S.M.; Husebø, A.M.L. Initiation and maintenance of lifestyle changes among participants in a healthy life centre: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S. Obesity in midlifestyle and dietary strategies. Clinacterics 2020, 23, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, A.; Merom, D.; Bull, F.C.; Buchner, D.M.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A. Updating the evidence for physical activity: Summative reviews of the epidemiological evidence, prevalence, and interventions to promote “active aging”. Gerontologist 2016, 56 (Suppl. 2), S268–S280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemamsha, H.; Papadopoulos, C.; Randhawa, G. Understanding the risk and protective factors associated with obesity amongst libyan adults-a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, N.; Légaré, F.; Stacey, D.; Lemieux, S.; Bégin, C.; Lapointe, A.; Desroches, S. Postmenopausal women with abdominal obesity choosing a nutritional approach for weight loss: A decisional needs assessment. Maturitas 2016, 94, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.D. The adaptive behavioral components (ABC) model for planning longitudinal behavioral technology-based health interventions: A theoretical framework. J. Med. Int. Res. 2020, 22, e15563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Rothman, A.J.; Leventhal, A.M.; Intille, S.S. How intensive longitudinal data can stimulate advances in health behavior maintenance theories and interventions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 21 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | Classification | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

| Age | 58.6 ± 4.02 | |

| Postmenopausal period (years) | 7.6 ± 5.81 | |

| Socioeconomic class (self-rated) | High | 6 (28.6) |

| Middle | 13 (61.9) | |

| Low | 2 (9.5) | |

| Education level | University degree or above | 13 (61.9) |

| High school education | 6 (28.6) | |

| Middle school | 2 (9.5) | |

| Occupational classification | Housewife | 18 (85.7) |

| Office workers | 3 (14.3) | |

| BMI (body mass index, kg/m2) | Underweight (18.5 or below) | 1 (4.8) |

| Normal weight (18.5–22.9) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Pre-obese (23.0–24.9) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 6 (28.5) | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 1 (4.8) | |

| Facilitators (Participants’ Quotes) | Code | Subtheme | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| I worked out because I was desperate. I have to wear tight clothes when riding a bike. That way, when I see myself, I could see how my fat bulges out on my front and back. | Concerns about appearance | Intrinsic motivation | Taking a step toward healthy behavior maintenance using intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors |

| I reached menopause when I was 56. My weight gradually and continuously increased from that time on. Day after day, I would keep breaking the record. I felt quite miserable as I could no longer fit into nice clothes. | |||

| I was shocked after measuring my waist circumference. I was so embarrassed. My goal was to reduce my waist circumference, and that was it. I was so embarrassed that day. | |||

| This time, I felt the desperate need to not gain any more weight and not let my sugar levels rise since my weight had been continuously increasing. I worked out very hard after I started participating in this program. I began to lose weight as a result. | Health concern | ||

| I have diabetes... I love sweets, but I didn’t know I had diabetes. My father had diabetes, but it didn’t run in my families. I never thought I would have diabetes, but once, my results showed high sugar levels. I even retook the test to make sure the results were correct since I had no idea I had diabetes. Anyways, I really needed to lose weight. They said my sugar levels can be controlled, and I was in a little bit of disbelief, but since I really needed to do it... since something bad could happen if I didn’t... Yeah... I got very scared. | |||

| I think the desperate desire to get healthy after falling sick is more important. I found myself working harder to maintain a healthy lifestyle after I became sick. | |||

| ‘I think it would be easy if I had a goal. I once got rid of hypertension by exercising. I started participating in the program hoping to reduce my medication use if not completely stop it. With that goal in mind… or the goal to lose weight… I don’t want to be fat again. | Achievable goal | ||

| Whenever I eat, I would tell myself it’s not right as a parent to make my children feel worried. I’ve been trying to resist unhealthy food and eat something healthier | Preparing for active aging/desire for self-care | ||

| That could be one of the reasons why I pulled myself together. I think about how I don’t want to become a burden to my children whenever I don’t want to exercise and force myself to dress up and go outside. | |||

| They say, “you need to die well”. I don’t know how long I will live but during what remaining time I have, I want to be healthy and independent and not bother anyone. Whenever I think about this, I get waken up again (laughing). I tell myself I should die well and stay healthy while I’m alive. | |||

| We are aware that whereas people in our generation take care of our parents, people in the current generation would never do such a thing. We need to stay healthy to be able to take care of ourselves instead of being taken care of by our children. The idea that I need to take care of my own health kind of motivated me. | |||

| I don’t really like onions. But once, I made onion pickles after I saw on a television show that onions are good for health. My diet gradually improved unknowingly. When a television show tells you something is good for losing fat, I’d give it a try. | Mass media | Extrinsic motivation | |

| People tell me I look well because they don’t want to directly tell me that I gained weight. Before, people used to tell me I gained a lot of weight. The first few times, I just responded with “Oh, I see...” But I keep hearing it, and it really stresses me out. Nevertheless, these comments from other people motivated me during the program. | Peer pressure | ||

| The act of participating in the program alone made us more alert about taking care of our health. We were mindful about what to record, so we tried to do more exercise. | Available programs | ||

| Even though there was a mountain right in front of my house, I didn’t go out to exercise. There were a plenty of places to exercise. Participating in the program developed my habit of exercising every morning. | |||

| Messages like “You drank too much alcohol” made me become aware of my mistakes. I’d be like, “Oh, I may have indeed drunk a lot”. I once asked if drinking 500 cc of alcohol is considered too much (laughing). The feedbacks I get from time to time provide the opportunity to fix myself. | Experts’ advice | ||

| The professor insisted that I needed to reduce my carbohydrate consumption. She told me to reduce it to two-thirds of the amount that I normally eat and to eat bland side dishes first. Eating bland side dishes first helped me eat less rice. Following her tips, I think I lost weight again. | |||

| The step counter… Part of the reason why I started participating was because I wanted the step counter. | Decoys | ||

| I wouldn’t call what I did an exercise, but whenever I had some free time during daily life, or whenever there was some gap time between one schedule and another, I would walk instead of taking the subway. I would walk around an hour this way. | Efforts (behavioral control) balancing and integrating with daily life | Internal reinforcement/autonomy | Lifestyle rebalancing under the self-regulation employing internal and external reinforcement |

| There’s a famous fish-shaped bun place right in front of my house. I used to buy 2000 won’s worth of buns whenever I passed by that place since they only give you three buns per 1000 won. Now, I don’t give into my temptation and just go my way. | |||

| I forced myself to do what I didn’t want to do and walked 10,000 steps per week. I tried to walk over 10,000 steps within a week or walk at least one hour per day. Although I am doing the same thing over and over, it is hard to keep the habit of walking. I think being consistent is challenging. But over time, I slowly got used to walking. | |||

| After losing weight by exercising, I felt myself looking better. So now, I have my own rule for losing weight. If I gain one kilogram, I control my eating. Using this method, I’ve been able to maintain my weight. | |||

| I eat little even when I’m eating out. Even though I eat less, my weight on the scale keeps increasing. Since I’m forced to eat when I’m eating out with someone, I tend to avoid eating out with others. That was intriguing. | |||

| I never thought I would dance. I had never done it before the program. I found myself enjoying it a lot and actually keeping up with it despite my age. I enjoyed it so much. | Finding fun | ||

| I really like the music. They played the music we used to listen when we were students. I enjoyed losing the drastic weight I gained. I just enjoyed my life. Yeah, it was a lot of fun... | |||

| Even on a hot summer day, even when it was raining, I made sure to walk on Wednesdays since Wednesdays were set as the “Walking Day”. On rainy days, the three of us would be walking in white raincoats (laughing). It was fun too. Walking was an extra source of fun aside from volunteering on Wednesdays. I had a lot of fun losing weight this summer. | |||

| The reason why I am extending my participation is that I determined to increase my muscle mass for the next three months. I got curious about how much effort would be needed to gain how much muscle mass. Now that I can check my muscle mass on my own… | Continue with interest | ||

| I already knew that my lifestyle was blamed to be fat. But when I checked one by one in this program, it seems clear that I was getting fat because of things that I should have changed. | Self-reflection | ||

| Since I needed to fill out the checklist… I didn’t want to leave too many checkboxes empty, so I tried my best. | Self-monitoring | ||

| It’s for me… It’s not for others. Even if I feel lazy, I still need to do it because it’s for myself. I think I did it just as how we live through our daily life. | Value/usefulness | ||

| Seeing numerical improvements helped me understand my progress and motivated me to work harder. | Perceived benefits | ||

| I was very fat in the beginning. I’m still fat now, and I was especially fat here (touching her armpits). One day, I shook my arms as I walked, and my arms felt so much lighter than it used to. They just felt light. At that point, I thought, “Oh, I think I am losing fat now”. But my weight on the scale still doesn’t change. Even then, I still enjoy doing it every day. I feel happy for myself. | |||

| When I hiked five times a week, my health drastically became better. I lost weight, my disc conditions got better. My body just improved overall. It was really good. | |||

| The fat around my waist… (laughing) I used to feel displeased whenever I looked at it in the washroom mirror, but it’s ok. I feel satisfied with myself now. It’s not like others can look at my progress, but I see the effect. | |||

| I would exercise early in the morning, but some days, I feel tempted to just go home and sleep more. But once I beat that temptation and come back home after completing my exercise, I feel achieved and can start my day in a good mood. | Perceived competence | ||

| I started out by walking. I noticed others were also walking... Once, a young person was jogging, not too fast, like this, and I tried to do the same, and it worked. | |||

| After we began to actively walk, I got inspired by people around me who were walking to lose weight although I don’t know how motivated they were to walk. I think people around me had an influence on me. They motivated me to work harder. | |||

| I enjoy walking, so walking worked the best for me. Everyone has a different method that works for them. To me, it was walking. | Preference/ Choice | ||

| I started doing a “Wednesday walk” with other participants from here to Soongsil University. We would walk through the cemetery, and later the other two would walk toward their houses and I toward Singil-dong, which is where I live. We did this once every week together, and it helped a lot. We said we’d do this every Wednesday. | Peer supports | External reinforcement | |

| I asked a person who was also in the program how she did it. She did 30 sit-ups despite the pain. I felt motivated by her. | |||

| Since I knew precise results would be out after a few months, I worked harder to achieve better results. When there are no accurate data to show my progress, I tend to slack off even if I was determined in the beginning. Now, I think about how my cholesterol levels would change in a blood test a few months later and am careful about what I eat. | Verifiable results | ||

| Yes. I didn’t want to participate initially, but my daughter pushed me. She helps me a lot. I personally don’t enjoy exercising and I like eating. I told myself I’d give it my best try and I think I did this time. My health drastically got better. I’m thankful for my daughter. She still monitors what I eat. | Family supports | ||

| I’d forget about the program and get reminded again by a text message. The fact that my coach still cared about me (laughing) motivated me to work harder. | Expert supports | ||

| They show you how many kilometers you have walked so far at the Yangjae Stream. I can calculate how many calories I’ve burned by walking two kilometers. | Environmental stimulus | ||

| You usually go to the gym to work out rather than just working out alone. Since you pay the gym to work out, you work out harder. | Economic efficacy |

| Inhibitors | Code | Subtheme | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| I ended up regaining weight from exercising less and eating on Thanksgiving. | Holiday event | Disruptions in daily routine | Failure to integrate healthy habits into lifestyle |

| I manage to control my appetite from Monday to Friday, and then end up eating again on Saturday and Sunday and regain weight. Even if I do well until Friday, if I end up drinking and eating out, my weight goes back to what it was, and this cycle keeps repeating. There are many occasions where I eat out with my family... and go out to have a drink with others, so it’s hard to stay consistent. | Eating out | ||

| I was lying on the bed with a cast on my left leg which was injured. After that, two of my chest bones broke, so as soon as my leg healed, I had to stay on the bed for another four to six weeks. Then I broke my right leg. I ended up eating snacks a lot since I spent all my time at home. I’d wallow around and keep opening and closing the fridge. I think eating snacks became a habit because of this experience. | Injury | ||

| I also end up breaking the rules when I’m traveling. | Travel | ||

| The stress that accumulated over the course of the day… I also feed my kids all three meals and end up eating with them. I get tired from work and from feeding my kids. I think I tried to cope with the stress by eating. | Bad habits related to daily life stress | Decreased autonomy | |

| I spend a lot of my time with kids, and I love eating. I can’t help but eat some of my kids’ snacks… I think I felt stressed about having my alone time taken away by the kids and tried to cope with the stress by eating, which resulted in my weight gain. | |||

| When you become obsessed… You’re supposed to enjoy it. You tell yourself you have to do something, and that makes it even harder. | Pressure/ tension related to the program | ||

| To me, the pressure to keep up was very stressful. I felt like if I didn’t keep up, I would fall behind everyone else. Having to fill out the self-checklist on the computer according to the schedule was too much for me, so I just gave up. | |||

| I feel so pathetic and depressed. I would try but fail. I would see how weak-willed I am and feel unenergetic. And then again, I would tell myself to try again. Even then, I’d still feel unenergetic for a long time. I’m so pathetic. | Lowered perceptions of competence | ||

| I keep telling myself I’ll start today or tomorrow. I feel so pathetic and feel frustrated with me. My head knows what’s right, but once I see it, I can’t help it. I’d regret and tell myself I shouldn’t have eaten, but I keep making the same mistakes. | |||

| I love sweets. My head tells me not to eat them, but once I see them, I can’t help it. I think that’s the problem. | Lack of perceived eating control | ||

| I love flour. I am a fan of bread. I know it’s not good for you, but my desire for it is stronger. Even if I’m full, I’d eat bread if there’s one. One person told me I’d lose 2–3 kilos by simply cutting off bread. What can I do, though? My desire for bread is just too strong. If I had won during that fight, I would not weight over 50 kg right now. | |||

| I do think that I need to work out, but the busy schedule I set for myself keeps me from working out. | Deprioritize | ||

| I don’t know if it’s because I don’t see any immediate threats to my health, but I keep skipping exercise if I feel a bit tired. | Lack of perceived threat | ||

| My thyroid conditions make me feel weak and lethargic. I keep skipping exercises by making excuses about my thyroid conditions. It’s actually difficult for me to move. You know what I mean… I feel very tired and crave sweets. I gained two kilograms as a result, and it’s been hard to lose the gained weight | physical limitations | ||

| I used to exercise a lot initially. I even walked around Santiago and lost 3 kg but regained the weight in a week. I haven’t seen any change in my weight, not even 0.1 kg loss. There’s no change at all no matter how much I exercise. | Unmet expectations | Insufficient reinforcement | Inappropriate supportive strategy |

| I did eat out a lot, but I was hopeful that my health level would improve. They turned out to have worsened, and it really disappointed me. I felt so discouraged. Plus, my knees have also been hurting. In the past, I used to climb the stairs even when I was tired and enjoyed doing it, but lately, I’ve been careful with exercising. | |||

| You know how you feel when your results are not up to your expectations. When we were young, we would eat a lot but if you exercise one day, you’d see the effect of it the next day. Now, even after three or four days, postmenopausal women like me don’t see any improvements because we’re old. Since we’re not seeing immediate improvements, it’s harder to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Seeing even just a small improvement would motivate us but without seeing any improvement, we can’t get ourselves to it. | |||

| I did a blood test only to find out that my sugar levels hadn’t dropped and felt like this wasn’t working either... I just ended up getting lazier and inconsistent. | |||

| I was hopeful that since I was doing something that I never used to do and I was working hard, I would see drastic improvements, but that was not the case… and it made me skeptical. Since there were no immediate improvements… | |||

| I used to go to the gym to use the bike machine and run on the treadmill, but the air inside the gym felt so suffocating. I ended up not going to the gym often… | Environmental limitations | ||

| When it’s raining heavily, I don’t go out. When there’s no one outside, it’s scary. The Han River is bustling with people even after midnight. At the Ttukseom Park, you can go out any time to exercise, but even there, it’s scary when it’s rainy and dark with no people around… | |||

| The internal medicine doctor didn’t tell me to lose weight contrary to what I expected. I found that a bit strange, but it did make me slack off a bit. | Lack of experts advise | ||

| I think the program was a bit ineffective because they didn’t tell me to walk exactly how many kilometers. | Deficit of precise directions | ||

| I didn’t want to hike alone, so I just didn’t go hiking. My blood pressure started rising again after I stopped hiking | Lack of supportive relationships | ||

| I had fun exercising during the program, but I couldn’t get myself to do the same exercise alone at home. | |||

| What I really hate is when a friend brings brown rice to our hangout session because she’s on a diet. I hate that! She shouldn’t have come! Her doing that really breaks the mood. I get that she’s strong-willed and may later be successful with weight loss, but I let myself eat when we’re hanging out. I guess it’s just different opinions, but people like her ruin my mood. How can you bring a lunch like that? I just let myself loose when we’re hanging out and eat to my heart’s content. That’s why I have all this fat. | Perceived norms | Subjective norms | |

| I felt so weak after I lost around one kilogram. I told my friends I felt weak, and my friends told me, “Hey, it’s because you lost weight. Just eat” (laughing). They told me that people who eat well look well, and that when you lose weight at our age, you are bound to feel weak. | |||

| You’re throwing away the effort of the person who cooked the meal when you’re throwing away a meal. You know they say you need to look good when you die (laughing), so you have to eat. | |||

| I’d just accept one drink and drink maybe half of it just to go along with the mood. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.-R.; Yang, H.-M. Facilitators and Inhibitors of Lifestyle Modification and Maintenance of KOREAN Postmenopausal Women: Revealing Conversations from FOCUS Group Interview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218178

Kim H-R, Yang H-M. Facilitators and Inhibitors of Lifestyle Modification and Maintenance of KOREAN Postmenopausal Women: Revealing Conversations from FOCUS Group Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218178

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hye-Ryoung, and Hwa-Mi Yang. 2020. "Facilitators and Inhibitors of Lifestyle Modification and Maintenance of KOREAN Postmenopausal Women: Revealing Conversations from FOCUS Group Interview" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 21: 8178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218178

APA StyleKim, H.-R., & Yang, H.-M. (2020). Facilitators and Inhibitors of Lifestyle Modification and Maintenance of KOREAN Postmenopausal Women: Revealing Conversations from FOCUS Group Interview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 8178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218178