Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Questionnaire

2.2. Ethical Permission

2.3. COVID-19 Knowledge Score (K-Score) Calculation

2.4. Anxiety Score Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. Knowledge of COVID-19 Transmission, Prevention and Control

3.3. Attitude Towards COVID-19

3.4. Correlation of COVID-19 Knowledge to Different Variables

3.5. Anxiety Level in Relation to Other Variables

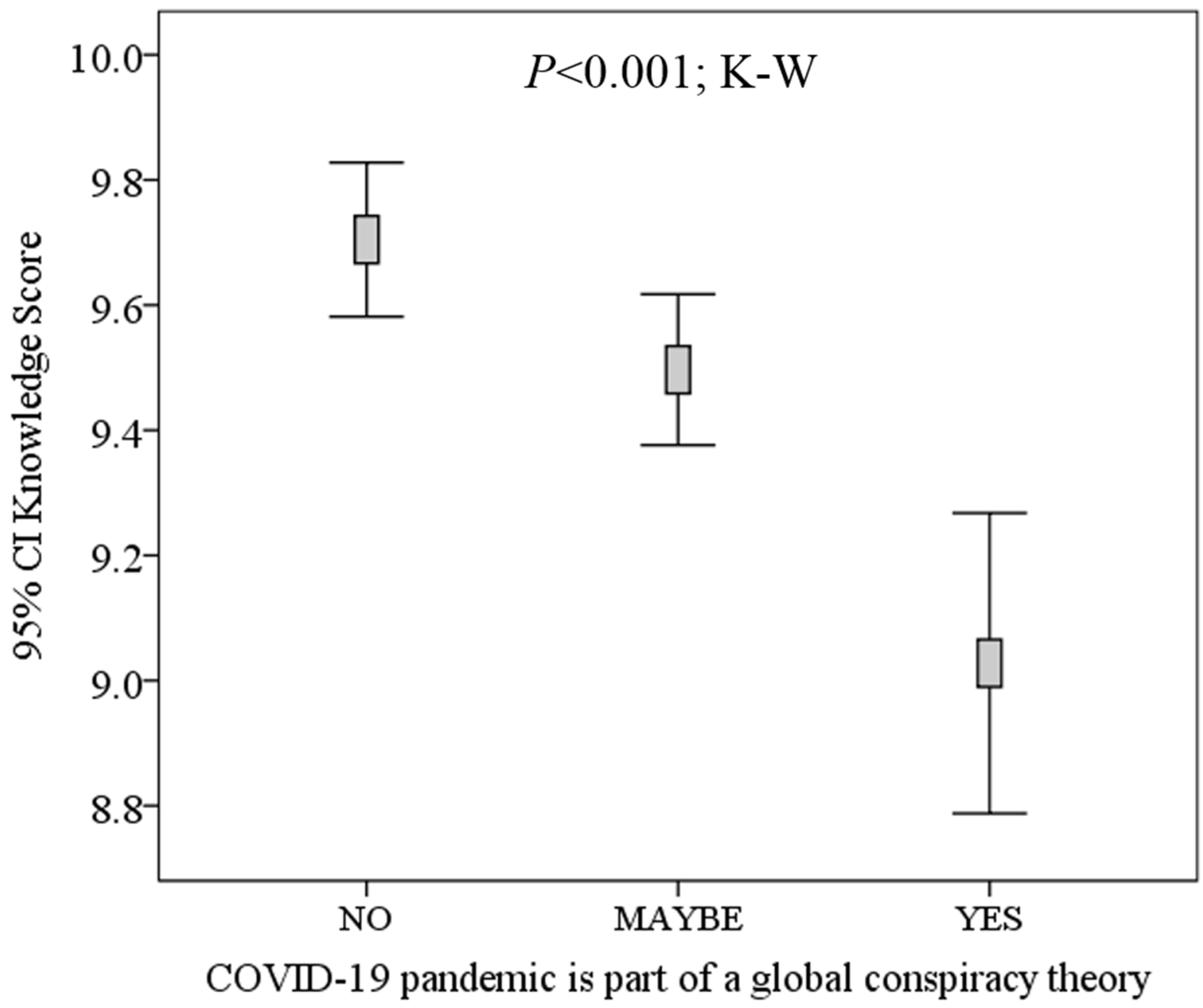

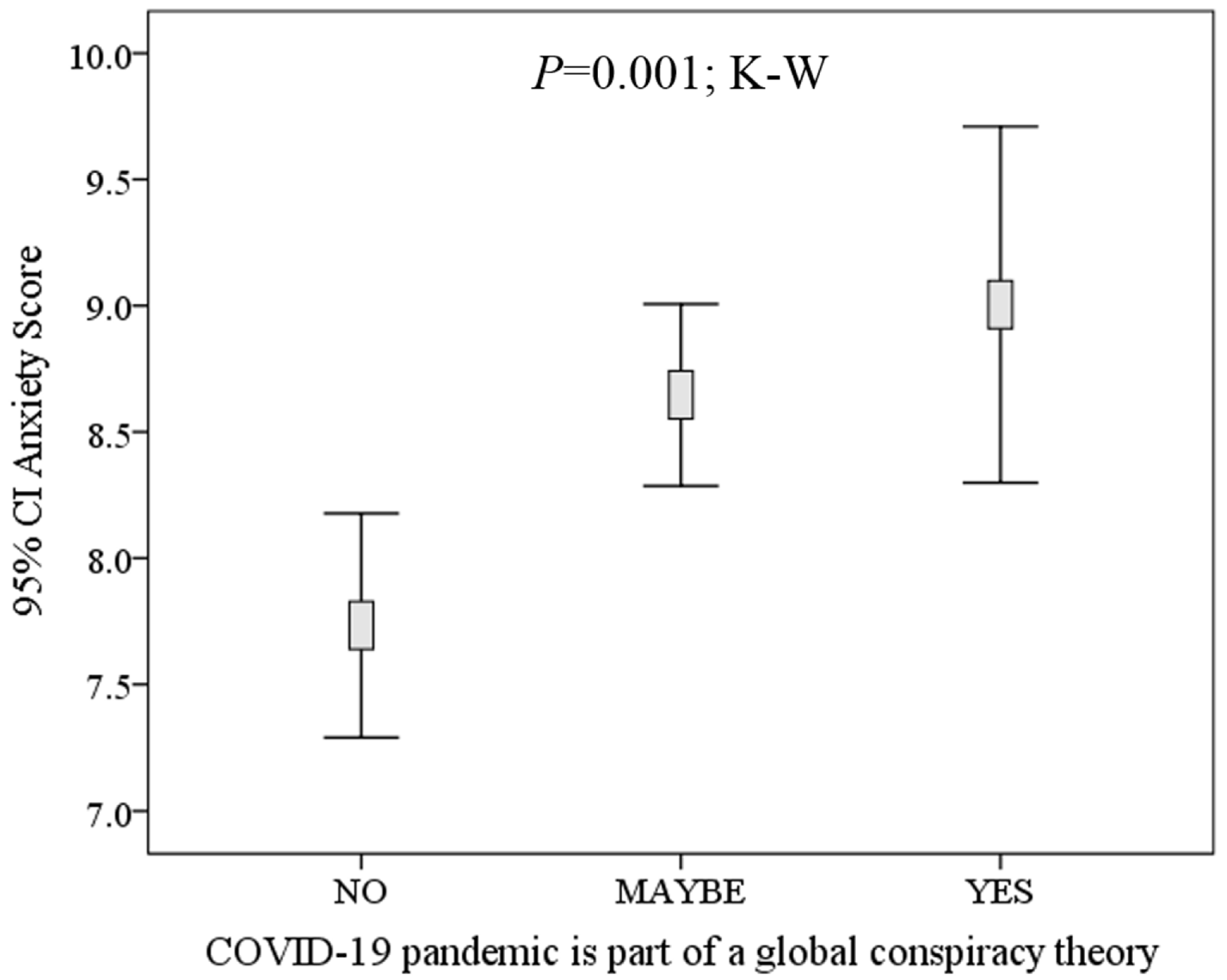

3.6. Association of Belief in Conspiracy with Other Variables

3.7. Sources of Information Regarding COVID-19

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| GAD-7 | 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale |

| JOD | Jordanian dinar |

| K-score | COVID-19 knowledge score |

| K–W | Kruskal-Wallis test |

| MERS | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| MoH | Jordanian Ministry of Health |

| M–W | Mann-Whitney U test |

| SARS | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| UJ | University of Jordan |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| χ2 | Chi-squared test |

References

- Graham, B.S.; Sullivan, N.J. Emerging viral diseases from a vaccinology perspective: Preparing for the next pandemic. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, N.D.; Dunavan, C.P.; Diamond, J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 2007, 447, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morens, D.M.; Daszak, P.; Taubenberger, J.K. Escaping Pandora’s Box—Another Novel Coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1293–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahase, E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ 2020, 368, m1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Wan, S.; Xiang, Y.; Fang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B.; Hu, Y.; Lang, C.; Huang, D.; Sun, Q.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Cardona-Ospina, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Ocampo, E.; Villamizar-Peña, R.; Holguin-Rivera, Y.; Escalera-Antezana, J.P.; Alvarado-Arnez, L.E.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Henao-Martinez, A.F.; et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 34, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.J.; Mao, Y.P.; Ye, R.X.; Wang, Q.Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, B.; Mao, J.; Fu, J.; Shang, S.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, T. Epidemiological analysis of COVID-19 and practical experience from China. J. Med. Virol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). How COVID-19 Spreads. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- World Health Organization. WHO: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Mian, A.; Khan, S. Coronavirus: The spread of misinformation. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.S.; Oh, A.; Klein, W.M.P. Addressing Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media. JAMA 2018, 320, 2417–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Arguel, A.; Neves, A.L.; Gallagher, A.M.; Kaplan, R.; Mortimer, N.; Mendes, G.A.; Lau, A.Y. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenblum, R.; Bates, D.W. Patient-centred healthcare, social media and the internet: The perfect storm? BMJ Qual. Saf. 2013, 22, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, J.; Shaw, R. Corona Virus (COVID-19) “Infodemic” and Emerging Issues through a Data Lens: The Case of China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucci, V.; Moukaddam, N.; Meadows, J.; Shah, S.; Galwankar, S.C.; Kapur, G.B. The Forgotten Plague: Psychiatric Manifestations of Ebola, Zika, and Emerging Infectious Diseases. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2017, 9, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.S.; Chee, C.Y.; Ho, R.C. Mental Health Strategies to Combat the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 beyond Paranoia and Panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 2020, 49, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- van Prooijen, J.W.; van Vugt, M. Conspiracy Theories: Evolved Functions and Psychological Mechanisms. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V.; Voracek, M.; Stieger, S.; Tran, U.S.; Furnham, A. Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition 2014, 133, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelela, N.; Venter, W.D.; Pillay, Y.; Barron, P. A Political and Social History of HIV in South Africa. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015, 12, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benecke, O.; DeYoung, S.E. Anti-Vaccine Decision-Making and Measles Resurgence in the United States. Glob. Pediatric Health 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Jordan. About UJ. Available online: http://www.ju.edu.jo/Pages/AboutUJ.aspx (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Johnson, S.U.; Ulvenes, P.G.; Oktedalen, T.; Hoffart, A. Psychometric Properties of the General Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) Scale in a Heterogeneous Psychiatric Sample. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Decker, O.; Müller, S.; Brähler, E.; Schellberg, D.; Herzog, W.; Herzberg, P.Y. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med. Care 2008, 46, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Fang, Z.; Hou, G.; Han, M.; Xu, X.; Dong, J.; Zheng, J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 287, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depoux, A.; Martin, S.; Karafillakis, E.; Bsd, R.P.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Larson, H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Su, K.P. Using psychoneuroimmunity against COVID-19. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlani-Duault, L.; Ward, J.K.; Roy, M.; Morin, C.; Wilson, A. Tracking online heroisation and blame in epidemics. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e13–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A. Evolutionary analysis of the dynamics of viral infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.E.; Chen, L.H. Travellers give wings to novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sejvar, J.J. West nile virus: An historical overview. Ochsner J. 2003, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Li, J.; Carr, M.J.; Duchene, S.; Shi, W. The Asian Lineage of Zika Virus: Transmission and Evolution in Asia and the Americas. Virol. Sin. 2019, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí Saéz, A.; Weiss, S.; Nowak, K.; Lapeyre, V.; Zimmermann, F.; Düx, A.; Kühl, H.S.; Kaba, M.; Regnaut, S.; Merkel, K.; et al. Investigating the zoonotic origin of the West African Ebola epidemic. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuto, D.; Giovanetti, M.; Salemi, M.; Prosperi, M.; De Flora, C.; Junior Alcantara, L.C.; Angeletti, S.; Ciccozzi, M. The global spread of 2019-nCoV: A molecular evolutionary analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health 2020, 114, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derek Lowe. Hydroxychloroquine Update for April 6. Available online: https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2020/04/06/hydroxychloroquine-update-for-april-6 (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Ye, F.; Xu, S.; Rong, Z.; Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Deng, P.; Liu, H.; Xu, X. Delivery of infection from asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 in a familial cluster. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, L.T.; Nguyen, T.V.; Luong, Q.C.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, H.T.; Le, H.Q.; Nguyen, T.T.; Cao, T.M.; Pham, Q.D. Importation and Human-to-Human Transmission of a Novel Coronavirus in Vietnam. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Association of Blood Banks (AABB). Message to Blood Donors during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: http://www.aabb.org/advocacy/regulatorygovernment/Documents/Message-to-Blood-Donors-During-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Chang, L.; Yan, Y.; Wang, L. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Coronaviruses and Blood Safety. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2020, 34, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, C.P.; Asnaani, A.; Litz, B.T.; Hofmann, S.G. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, Y.J.; Deyoung, C.G.; Hirsh, J.B. Gender Differences in Personality across the Ten Aspects of the Big Five. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, K.M.; Sutton, R.M.; Cichocka, A. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 26, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health (MoH) J. Coronavirus Disease 2019. Available online: https://corona.moh.gov.jo/ar (accessed on 10 April 2020).

| Characteristic | N 1 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (median, SD 2) | 21 (3.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 394 (25.6) |

| Female | 1145 (74.4) |

| Nationality | |

| Jordanian | 1386 (90.2) |

| Non-Jordanian3 | 151 (9.8) |

| Program 4 | |

| BSc | 1378 (89.5) |

| MSc | 138 (9.0) |

| PhD | 24 (1.6) |

| Schools 5 | |

| Health6 | 664 (48.5) |

| Scientific7 | 392 (28.6) |

| Humanities8 | 313 (22.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 1440 (94.1) |

| Married | 85 (5.6) |

| Divorced | 6 (0.4) |

| Monthly income 9 | |

| Less than JOD 50010 | 397 (25.8) |

| JOD 500–1000 | 646 (41.9) |

| More than JOD 1000 | 497 (32.3) |

| Feature | Nationality | Gender | Schools of UJ 1 | Monthly Income of the Family 2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordanian | Non-Jordanian 3 | Male | Female | Health and Scientific Schools 4 | Humanities Schools 5 | Less than JOD 500 6 | JOD 500–1000 | More than JOD 1000 | ||||||

| Survey item | Response | N 7 (%) | N (%) | p-value 8 | N (%) | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | N (%) | p-value | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p-value |

| Is COVID-19 dangerous? 9 | Not dangerous | 26 (1.9) | 7 (4.6) | 0.020 | 9 (2.3) | 24 (2.1) | <0.001 | 24 (2.3) | 8 (2.6) | <0.001 | 10 (2.5) | 10 (1.5) | 13 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Moderately dangerous | 965 (69.6) | 112 (74.2) | 233 (59.1) | 845 (73.8) | 782 (74.1) | 191 (61.0) | 236 (59.4) | 469 (72.6) | 374 (75.3) | |||||

| Very dangerous | 395 (28.5) | 32 (21.2) | 152 (38.6) | 276 (24.1) | 250 (23.7) | 114 (36.4) | 151 (38.0) | 167 (25.9) | 110 (22.1) | |||||

| Coronavirus infection can be treated using an antibiotic | Correct response | 1226 (88.5) | 137 (90.7) | 0.403 | 348 (88.3) | 1016 (88.7) | 0.826 | 965 (91.4) | 249 (79.6) | <0.001 | 337 (84.9) | 577 (89.3) | 451 (90.7) | 0.018 |

| Incorrect response | 160 (11.5) | 14 (9.3) | 46 (11.7) | 129 (11.3) | 91 (8.6) | 64 (20.4) | 60 (15.1) | 69 (10.7) | 46 (9.3) | |||||

| There is a vaccine available for COVID-19 | Correct response | 1288 (92.9) | 143 (94.7) | 0.414 | 370 (93.9) | 1062 (92.8) | 0.436 | 990 (93.8) | 284 (90.7) | 0.065 | 359 (90.4) | 602 (93.2) | 472 (95.0) | 0.029 |

| Incorrect response | 98 (7.1) | 8 (5.3) | 24 (6.1) | 83 (7.2) | 66 (6.3) | 29 (9.3) | 38 (9.6) | 44 (6.8) | 25 (5.0) | |||||

| Summer heat can kill the COVID-19 virus | Correct response | 820 (59.2) | 98 (64.9) | 0.172 | 235 (59.6) | 684 (59.7) | 0.974 | 701 (66.4) | 135 (43.1) | <0.001 | 198 (49.9) | 388 (60.1) | 333 (67.0) | <0.001 |

| Incorrect response | 566 (40.8) | 53 (35.1) | 159 (40.4) | 461 (40.3) | 355 (33.6) | 178 (56.9) | 199 (50.1) | 258 (39.9) | 164 (33.0) | |||||

| Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic is part of a global conspiracy theory? | No | 458 (33.0) | 58 (38.4) | 0.402 | 163 (41.4) | 355 (31.0) | 0.001 | 395 (37.4) | 82 (26.2) | <0.001 | 101 (25.4) | 213 (33.0) | 204 (41.0) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 228 (16.5) | 24 (15.9) | 51 (12.9) | 202 (17.6) | 144 (13.6) | 69 (22.0) | 80 (20.2) | 107 (16.6) | 66 (13.3) | |||||

| Maybe | 700 (50.5) | 69 (45.7) | 180 (45.7) | 588 (51.4) | 517 (49.0) | 162 (51.8) | 216 (54.4) | 326 (50.5) | 227 (45.7) | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Yaseen, A.; Al-Haidar, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4915. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144915

Sallam M, Dababseh D, Yaseen A, Al-Haidar A, Ababneh NA, Bakri FG, Mahafzah A. Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):4915. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144915

Chicago/Turabian StyleSallam, Malik, Deema Dababseh, Alaa’ Yaseen, Ayat Al-Haidar, Nidaa A. Ababneh, Faris G. Bakri, and Azmi Mahafzah. 2020. "Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 14: 4915. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144915

APA StyleSallam, M., Dababseh, D., Yaseen, A., Al-Haidar, A., Ababneh, N. A., Bakri, F. G., & Mahafzah, A. (2020). Conspiracy Beliefs Are Associated with Lower Knowledge and Higher Anxiety Levels Regarding COVID-19 among Students at the University of Jordan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 4915. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144915