Abstract

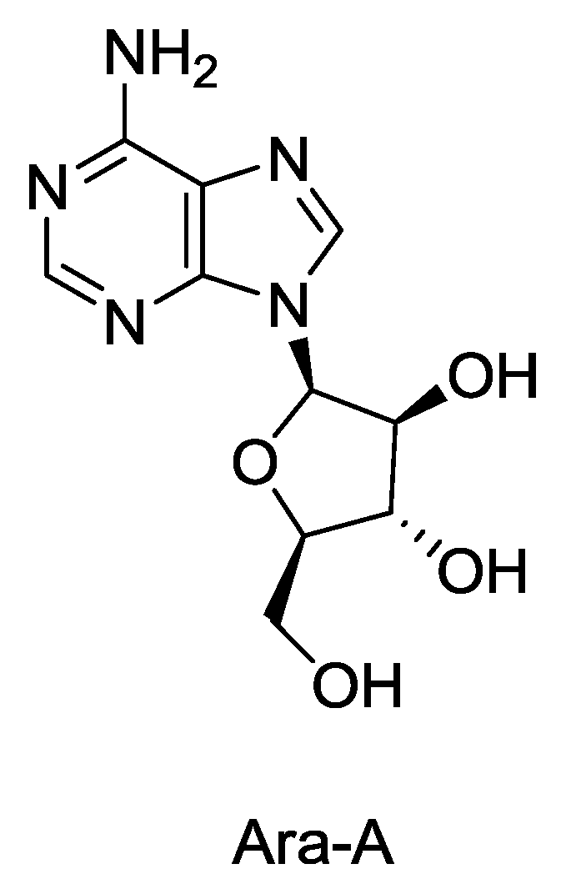

Marine sponges are currently one of the richest sources of pharmacologically active compounds found in the marine environment. These bioactive molecules are often secondary metabolites, whose main function is to enable and/or modulate cellular communication and defense. They are usually produced by functional enzyme clusters in sponges and/or their associated symbiotic microorganisms. Natural product lead compounds from sponges have often been found to be promising pharmaceutical agents. Several of them have successfully been approved as antiviral agents for clinical use or have been advanced to the late stages of clinical trials. Most of these drugs are used for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV). The most important antiviral lead of marine origin reported thus far is nucleoside Ara-A (vidarabine) isolated from sponge Tethya crypta. It inhibits viral DNA polymerase and DNA synthesis of herpes, vaccinica and varicella zoster viruses. However due to the discovery of new types of viruses and emergence of drug resistant strains, it is necessary to develop new antiviral lead compounds continuously. Several sponge derived antiviral lead compounds which are hopedto be developed as future drugs are discussed in this review. Supply problems are usually the major bottleneck to the development of these compounds as drugs during clinical trials. However advances in the field of metagenomics and high throughput microbial cultivation has raised the possibility that these techniques could lead to the cost-effective large scale production of such compounds. Perspectives on biotechnological methods with respect to marine drug development are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Marine sponges (phylum Porifera) are among the oldest multicellular invertebrate organisms [1] exhibiting a wide variety of colors and shapes. About 8,000 species of sponges, inhabiting different marine and freshwater ecosystems have been described to date [2]. Marine sponges are a rich source of potent natural products, some of which are considered as highly significant lead compounds for drug development. Most of these are secondary metabolites produced by the sponges [3] which may be produced to defend themselves against pathogenic bacteria, algae, fungi and other potential predators; a system they have developed during the process of evolution throughout thousands of years. More than 5,300 different natural compounds have been discovered from sponges and their associated microorganisms, and every year several hundred new compounds are being added [4].

Antiviral compounds are currently of particular interest since viral diseases (e.g., HIV, H1N1, HSV, etc.) have become major human health problems in recent decades. The ability of a virus to rapidly evolve and develop resistance to existing pharmaceuticals calls for continuing development of new antiviral drugs. Several lead antiviral compounds have been isolated from marine sponges, and there has been a consistent effort to identify new compounds.

The nucleosides spongothymidine and spongouridine were the first compounds isolated from a marine sponge (Tethya crypta) [5,6] which further led to the synthesis of Ara-C, an anticancer agent and Ara-A, the first antiviral drug. Ara-A inhibits viral DNA synthesis by conversion into adenine arabinoside triphosphate which inhibits viral DNA polymerase and DNA synthesis of herpes, vaccinica and varicella zoster viruses. It has been used clinically for treatment of herpes virus infection. Ara-A was the only sponge derived compound which was approved by the US FDA as an antiviral drug, although its marketing was later stopped as it was found to be less efficient and more toxic than the newer drug acyclovir (Zovirax) [7,8]. In addition to nucleosides, marine sponges are also the source of many alkaloids, sterols, terpenes, peptides, fatty acids, peroxides, etc. exhibiting the remarkable chemical diversity of compounds found in these organisms [9].

Several other sponge derived antiviral compounds are in preclinical/clinical trials for various diseases. However significant problems associated with these compounds have been a major limitation in the drug development and approval process. This is primarily due to the many technological challenges in detecting, isolating, characterizing, and scaling up production of bioactive compounds from marine sponges. To solve the critical supply problem, several efforts are being made in sponge farming, metagenomics and microbial cultivation, which are discussed below. Here we focus on existing or promising antiviral lead compounds from marine sponges which may have the potential to be future drugs.

3. Discussion

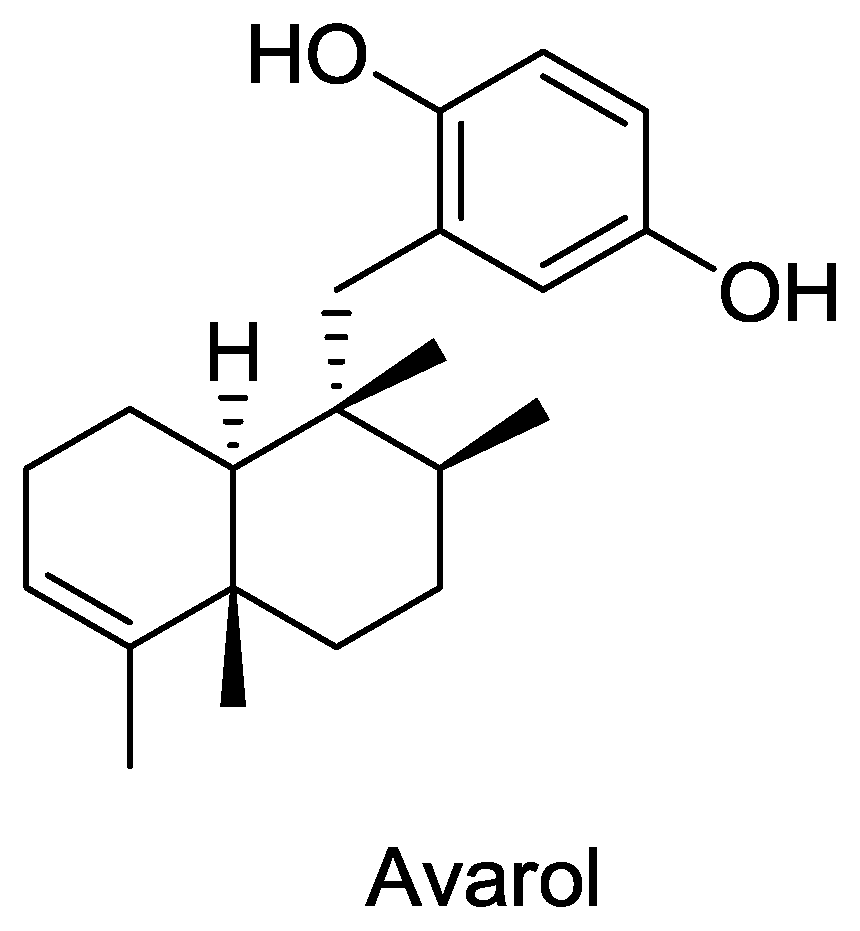

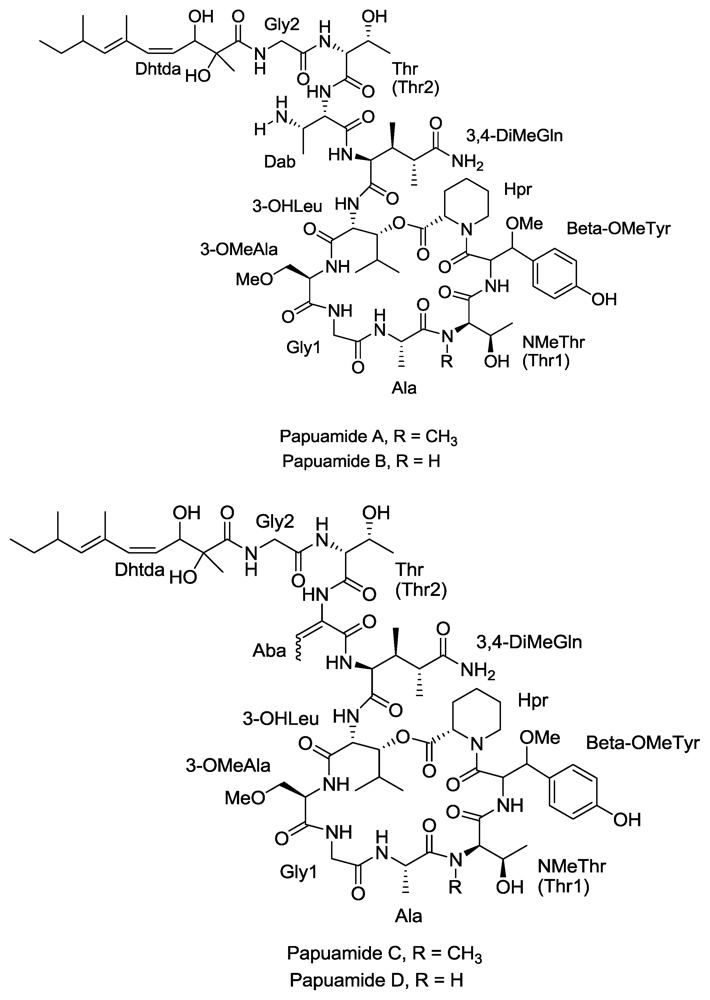

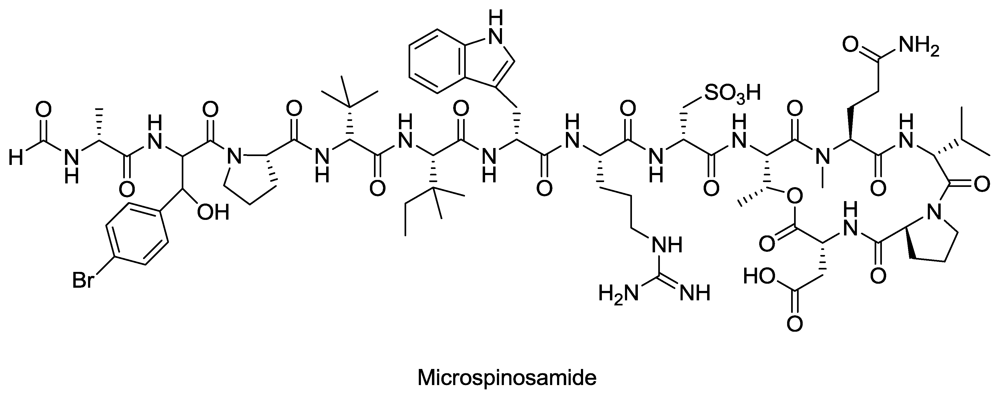

A total of 40 compounds have been officially approved for clinical use in the treatment of various viral ailments and at least half of them are used for the treatment of HIV infection [84]. Most of the sponge-derived compounds have also been screened for anti-HIV activity, showing the interest and potential importance of this field. This has led to the discovery of many compounds with anti-HIV activity, such as avarol, microspinosamide, papuamides A–D etc. Although many antiviral lead compounds have been derived from sponges, none of them has yet been approved as a drug (except Ara-A which is no longer in use). One of the reasons for this is the difficulty in obtaining a sustainable supply of these complex molecules for pre-clinical and clinical trials [85]. Most of the pharmaceutically interesting compounds found in sponges are present in minute amounts. For example, in order to obtain even 300 mg of halichondrins, a potent cytostatic polyketide of sponge origin, 1 metric ton of the sponge Lissodendoryx sp. must be extracted [86]. In addition, it is difficult to chemically synthesize most of these compounds due to their highly complex structures. In addition, the very long drug development process [87] makes this problem even more challenging. It is clear that such a large amount of biomass of marine sponges cannot be harvested from nature, and in the event that it were it would put these species at risk of extinction. More environmentally friendly and economically feasible strategies are clearly needed. Mariculture of sponges for large scale production of these compounds is an option but insufficient knowledge of the conditions and specific parameters for the growth and cultivation of sponges in the laboratory are the limiting factors. Culturing cells and primmorphs for production of metabolites may be feasible in the future but at present this technique is unable to produce large amount of biomass [88].

A growing body of evidence suggests that marine natural products may be the products of bacterial symbionts of sponges [89,90]. The Faulkner group demonstrated for the first time that natural products from sponges could be of bacterial origin [91]. Microorganisms associated with sponges have been characterized into 14 different phyla and their diversity and biotechnological importance have been reviewed [92]. Isolation and cultivation of sponge-associated microorganisms (microbial fermentation) producing the bioactive natural products is also another option for the large scale production of compounds of interest [93,94]. The success of this strategy depends on many factors. The majority of sponge associated microorganisms are difficult to culture [95,96]. Improved culturing of sponge associated microorganisms by supplementing the media with sponge extract [97] or catalase and sodium pyruvate [98] has been reported, but the proportion of total cultured bacteria has remained low. Only 0.06 and 0.1% of total bacteria could be cultured from the sponges Candidaspongia flabellate [99] and Rhopaloeides odorabile [97]. Furthermore, microorganisms isolated from sponges may not necessarily produce the same compound due to the requirement of intermediate compound/s from the host. Some bacteria also stop producing the compound of interest after a certain time on artificial media, which may be caused by a number of genetic factors linked to lack of selective pressure in culture [100]. To develop successful sponge culturing methods it is essential to understand the biology and natural living conditions of the sponges affecting growth and metabolite production. Various methods to culture sponges and sponge symbionts have been reviewed previously [101,102]. The attempts to develop and grow in vitro cell lines from sponges from metabolite production have also been reported [103].

Metagenomics is another strategy that has been used successfully to identify the biosynthetic origin of natural products. This procedure involves the genomic analysis of the total DNA in an organism and its symbionts. In the past few years metagenomics has emerged as a potential solution for genetic characterization of unculturable bacteria associated with marine sponges [104]. The method involves direct extraction and cloning of DNA from a group of bacteria and its genomic sequencing [105]. Initial efforts included the identification and isolation of gene clusters responsible for production of secondary metabolites involved in biosynthetic pathways, such as polyketide synthase (PKS) gene clusters [106,107]. Another study reported the cloning of chondramide biosynthesis cluster from C. crocatus, a myxobacterium [108]. The metagenomic approach was also employed for characterizing sponge-specific candidate phylum “Poribacteria” [109,110] and a new molybdenum-containing oxidoreductase and transmembrane proteins were identified [110]. The gene clusters identified using metagenomics approach is a step forward towards solving the problem of mass production of relevant natural products which further depends on the expression of the isolated gene clusters in relevant host. Heterologous expression vectors have been used to express the PKS biosynthetic clusters in Pseudomonas putida [111,112]. Other examples of expression hosts include E. coli [111–115], Myxobacteria and Streptomyces [116,117] used for expression of various biosynthetic pathways. Long et al. [118] applied the expression based techniques to identify expressing clones. The isolation of compounds from marine metagenomes is successful to a limited extent but this technology has been effectively employed on soil metagenomes where several antibiotics have been isolated using metagenomic approaches [119–122]. Although these studies demonstrate the success achieved by using the metagenomics approach there are still some technological issues related to this approach which must be overcome. Studies have provided compelling evidences that natural products known as polyketides are structurally similar in sponges and symbiont bacteria [2,123]. It has been made clear that these bacteria are the key producers of polyketides [124,125]. The complexity of the genomes of the group of organisms makes it very difficult to identify the target genome, and is further complicated by the use of inappropriate host organisms for cloning and expression [105,126] as well as the large size of the gene clusters [127]. The obstacles are manifold since sponges play host to a wide diversity of organisms such as bacteria, fungi, protists etc [128] resulting in a complex community. The expression of such complex metagenome will not be feasible in simple expression systems such as E. coli. The complex expression systems are needed to achieve the success in case of sponges [104]. To overcome the challenges associated with successful implementation of metagenomics approach, new methods have been developed and tested recently. One possible future direction could be to perform sequence based screens in order to identify enzymes that have been shown to be involved in the synthesis of anti-viral compounds. This strategy has been successfully developed and implicated to known polyketide synthase genes in an effort to identify new polyketides [129]. Other recently developed phylogenetic approaches can be applied to study the structure and function of biosynthetic enzymes as well as to isolate target gene clusters [130]. The metagenomic libraries can also be screened for antiviral activities by tailoring the methodologies previously used to identify natural-product clusters using genome sequence tags (GSTs). GSTs are the parts of the genes that can be used as probes to screen for similar genes in a clonal library. Any clone containing a GST can be a potential candidate for screening of novel natural-product gene clusters. This approach has been utilized to identify more than 450 natural-product clusters [131].

4. Conclusions

The literature regarding antiviral compounds from sponges shows the significance of marine natural products in the drug discovery and development process. With advancement of technologies a new generation of potent and effective antiviral agents may be obtained from these sources. Sequence based screens, metagenomic clonal library screening using GSTs and other phylogenetic approaches could provide a new future dimension in search for antiviral natural compounds from sponges. The successes in metagenomics coupled with heterologous expression and high throughput microbial cultivation techniques could pave the way for commercial production of such compounds in the future, greatly facilitating their analysis and commercialization.

- Samples Availability: Not applicable.

References

- Bergquist, P. Sponges; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, D; Cragg, G. Marine natural products and related compounds in clinical and advanced preclinical trials. J. Nat. Prod 2004, 67, 1216–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, AS; Daum, T; Miiller, WEG. Secondary Metabolites from Marine Sponges; Ullstein-Mosby Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, DJ. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep 2002, 19, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, W; Feeney, RJ. The isolation of a new thymine pentoside from sponges. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1950, 72, 2809–2810. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, W; Feeney, RJ. Contributions to the study of marine products. XXXII. The nucelosides of sponges. I. J. Org. Chem 1951, 16, 981–987. [Google Scholar]

- Shepp, DH; Dandliker, PS; Meyers, JD. Treatment of varicella-zoster virus infection in severely immunocompromised patients. A randomized comparison of acyclovir and vidarabine. N. Engl. J. Med 1986, 314, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, RJ; Gnann, JW, Jr; Hinthorn, D; Liu, C; Pollard, RB; Hayden, F; Mertz, GJ; Oxman, M; Soong, SJ. Disseminated herpes zoster in the immunocompromised host: a comparative trial of acyclovir and vidarabine. The NIAID Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. J. Infect. Dis 1992, 165, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt, JW; Copp, BR; Munro, MH; Northcote, PT; Prinsep, MR. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep 2005, 22, 15–61. [Google Scholar]

- Privat de Garilhe, M; de Rudder, J. Effect of 2 arbinose nucleosides on the multiplication of herpes virus and vaccine in cell culture. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci 1964, 259, 2725–2728. [Google Scholar]

- Field, H; De Clercq, E. Antiviral drugs-a short history of their discovery and development. Microbiol. Today 2004, 31, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, AMS; Glaser, KB; Cuevas, C; Jacobs, RS; Kem, W; Little, RD; McIntosh, JM; Newman, DJ; Potts, BC; Shuster, DE. The odyssey of marine pharmaceuticals: a current pipeline perspective. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2010, 31(6), 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Shope, TC; Kauffman, RE; Bowman, D; Marcus, EL. Pharmacokinetics of vidarabine in the treatment of infants and children with infections due to herpesviruses. J. Infect. Dis 1983, 148, 721–725. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, B; Kielty, J; Miller, F. Effect of a novel adenosine deaminase inhibitor (co-vidarabine, co-V) upon the antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo of vidarabine (Vira-Atm) for DNA virus replication. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 1977, 284, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R; Tucker, B; Kinkel, A; Barton, N; Pass, R; Whelchel, J; Cobbs, C; Diethelm, A; Buchanan, R. Pharmacology, tolerance, and antiviral activity of vidarabine monophosphate in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 1980, 18, 709. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama, T; Kurokawa, M; Shiraki, K. Characterization of the DNA polymerase gene of varicella-zoster viruses resistant to acyclovir. J. Gen. Virol 2001, 82, 2761–2765. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki, K; Namazue, J; Okuno, T; Yamanishi, K; Takahashi, M. Novel sensitivity of acyclovir-resistant varicella-zoster virus to anti-herpetic drugs. Antiviral Chem. Chemother 1990, 1, 373–375. [Google Scholar]

- Doering, A; Keller, J; Cohen, S. Some effects of D-arabinosyl nucleosides on polymer syntheses in mouse fibroblasts. Cancer Res 1966, 26, 2444. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett, W; Cohen, SS. Two approaches that increase the activity of analogs of adenine nucleosides in animal cells. Cancer Res 1975, 35, 1547–1554. [Google Scholar]

- Dicioccio, RA; Srivastava, BI. Kinetics of inhibition of deoxynucleotide-polymerizing enzyme activities from normal and leukemic human cells by 9-beta-d-arabinofuranosyladenine 5′-triphosphate and 1-beta-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine 5′-triphosphate. Eur. J. Biochem 1977, 79, 411–418. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, K; Jacob, S. Selective inhibition of RNA polyadenylation by Ara-ATP in vitro: a possible mechanism for antiviral action of Ara-A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1978, 81, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Hilfinger, JMWZ; Kim, J; Mitchell, S; Breitenbach, J; Amidon, G; Drach, J. Vidarabine Prodrugs as Anti-Pox Virus Agents. Antiviral Res 2006, 70, A14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z; Prudhomme, D; Buck, J; Park, M; Rizzo, C. Stereocontrolled Syntheses of Deoxyribonucleosides via Photoinduced Electron-Transfer Deoxygenation of Benzoyl-Protected Ribo-and Arabinonucleosides. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 5969–5985. [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz, E; Kazimierczuk, Z; Shugar, D. Preparation and properties of the O-methyl derivatives of 9-beta-D-arabinofuranosyladenine. Cancer Biochem. Biophys 1976, 1, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kotra, L; Manouilov, K; Cretton-Scott, E; Sommadossi, J; Boudinot, F; Schinazi, R; Chu, C. Synthesis, biotransformation, and pharmacokinetic studies of 9-(D-arabinofuranosyl)-6-azidopurine: A prodrug for Ara-A designed to utilize the azide reduction pathway. J. Med. Chem 1996, 39, 5202–5207. [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan, C; Shackleton, J; Tollerfield, S; Riley, P. Synthesis and evaluation of some novel phosphate and phosphinate derivatives of araA. Studies on the mechanism of action of phosphate triesters. Nucleic Acids Res 1989, 17, 10171–10177. [Google Scholar]

- Suhadolnik, R; Pornbanlualap, S; Wu, J; Baker, D; Hebbler, A. Biosynthesis of 9-[beta]-arabinofuranosyladenine: Hydrogen exchange at C-2′and oxygen exchange at C-3′of adenosine* 1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1989, 270, 363–373. [Google Scholar]

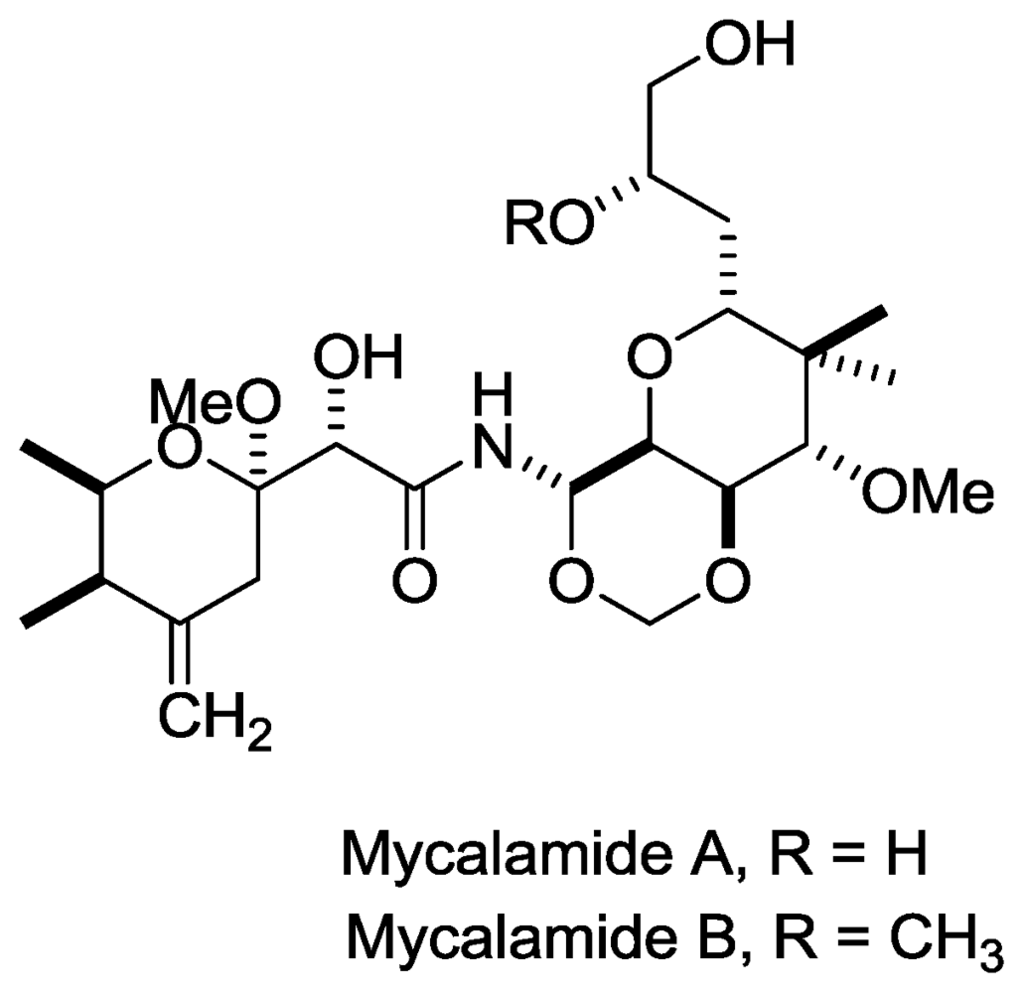

- Perry, N; Blunt, J; Munro, M; Pannell, L. Mycalamide A, an antiviral compound from a New Zealand sponge of the genus Mycale. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 4850–4851. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, NB; Blunt, JW; Munro, MHG; Thompson, AM. Antiviral and antitumor agents from a New Zealand sponge, Mycale sp. 2. Structures and solution conformations of mycalamides A and B. J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Burres, N; Clement, J. Antitumor activity and mechanism of action of the novel marine natural products mycalamide-A and-B and onnamide. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 2935. [Google Scholar]

- Gurel, G; Blaha, G; Steitz, T; Moore, P. The structures of Triacetyloleandomycin and Mycalamide A bound to the large ribosomal subunit of Haloarcula marismortui. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 5010–5014. [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa, N; Ihara, M; Toyota, M. Total Synthesis of (+)-Mycalamide A. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 875–878. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, J; Waizumi, N; Zhong, H; Rawal, V. Total synthesis of mycalamide A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 7290–7291. [Google Scholar]

- Toyota, M; Hirota, M; Hirano, H; Ihara, M. A stereoselective synthesis of the C-10 to C-18 (right-half) fragment of mycalamides employing lewis acid promoted intermolecular aldol reaction. Org. Lett 2000, 2, 2031–2034. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, B; Yang, H; Probst, G. A formal synthesis of (−)-mycalamide A. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, K; Kondoh, Y; Ueda, A; Yamada, K; Goto, H; Watanabe, T; Nakata, T; Osada, H; Aida, Y. Discovery of novel antiviral agents directed against the influenza A virus nucleoprotein using photo-cross-linked chemical arrays. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2010, 394(3), 721–727. [Google Scholar]

- Minale, L; Riccio, R; Sodano, G. Avarol a novel sesquiterpenoid hydroquinone with a rearranged drimane skeleton from the sponge. Tetrahedron Lett 1974, 15, 3401–3404. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, S; Minale, L; Riccio, R; Sodano, G. The absolute configuration of avarol, a rearranged sesquiterpenoid hydroquinone from a marine sponge. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1976, 1976, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, A; Chattopadhyay, P. Synthetic studies of trans-clerodane diterpenoids and congeners: stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-avarol. J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, P; Sun, D; Thornton, A; Muller, W. Inhibition of replication of the etiologic agent of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (human T-lymphotropic retrovirus/lymphadenopathy-associated virus) by avarol and avarone. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1987, 78, 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Batke, E; Ogura, R; Vaupel, P; Hummel, K; Kallinowski, F; Gasić, MJ; Schröder, H; Müllerm, W. Action of the antileukemic and anti-HTLV-III (anti-HIV) agent avarol on the levels of superoxide dismutases and glutathione peroxidase activities in L5178y mouse lymphoma cells. Cell Biochem. Funct 1988, 6, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchino, Y; Nishimura, S; Schröder, H; Rottmann, M; Müller, W. Selective inhibition of formation of suppressor glutamine tRNA in Moloney murine leukemia virus-infected NIH-3T3 cells by Avarol. Virology 1988, 165, 518–526. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, W; Schroder, H. Cell biological aspects of HIV-1 infection: effects of the anti-HIV-1 agent avarol. Int. J. Sports Med 1991, 12, S43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, WE; Schroder, HC; Reuter, P; Sarin, PS; Hess, G; Meyer zum Buschenfelde, KH; Kuchino, Y; Nishimura, S. Inhibition of expression of natural UAG suppressor glutamine tRNA in HIV-infected human H9 cells in vitro by Avarol. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1988, 4, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Loya, S; Hizi, A. The inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase by avarol and avarone derivatives. FEBS Lett 1990, 269, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, H; Bégin, M; Klöcking, R; Matthes, E; Sarma, A; Gašić, M; Müller, W. Avarol restores the altered prostaglandin and leukotriene metabolism in monocytes infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virus Res 1991, 21, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, P; Sun, D; Thornton, A; Miller, W. Inhibition of replication of the etiologic agent of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (human T-lymphotropic retrovirus/lymphadenopathy-associated virus) by avarol and avarone. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1987, 78, 663. [Google Scholar]

- De Giulio, A; De Rosa, S; Strazzulo, G; Diliberto, L; Obino, P; Marongiu, ME; Pani, A; La Colla, P. Synthesis and evaluation of cytostatic and antiviral activities of 3′and 4′-avarone derivatives. Antiviral Chem. Chemother 1991, 2, 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Suhadolnik, R; Pornbanlualap, S; Baker, D; Tiwari, K; Hebbler, A. Stereospecific 2′-amination and 2′-chlorination of adenosine by Actinomadura in the biosynthesis of 2′-amino-2′-deoxyadenosine and 2′-chloro-2′-deoxycoformycin* 1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1989, 270, 374–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, T; Xiang, A; Theodorakis, E. Enantioselective total synthesis of avarol and avarone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1999, 38, 3089–3091. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, W; Bohm, M; Batel, R; De Rosa, S; Tommonaro, G; Muller, I; Schroder, H. Application of cell culture for the production of bioactive compounds from sponges: synthesis of avarol by primmorphs from Dysidea avara. J. Nat. Prod 2000, 63, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W; Grebenjuk, V; Le Pennec, G; Schröder, H; Brümmer, F; Hentschel, U; Müller, I; Breter, H. Sustainable production of bioactive compounds by sponges—cell culture and gene cluster approach: a review. Mar. Biotechnol 2004, 6, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, P; Gustafson, K; McKee, T; Shigematsu, N; Maurizi, L; Pannell, L; Williams, D; de Silva, E; Lassota, P; Allen, T. Papuamides A–D, HIV-Inhibitory and Cytotoxic Depsipeptides from the Sponges Theonella mirabilis and Theonella swinhoei Collected in Papua New Guinea. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 5899–5909. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W; Ding, D; Zi, W; Li, G; Ma, D. Total Synthesis and Structure Assignment of Papuamide B, A Potent Marine Cyclodepsipeptide with Anti-HIV Properties13. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 2844–2848. [Google Scholar]

- Andjelic, C; Planelles, V; Barrows, L. Characterizing the Anti-HIV Activity of Papuamide A. Mar. Drugs 2008, 6, 528–549. [Google Scholar]

- Esté, J; Telenti, A. HIV entry inhibitors. Lancet 2007, 370, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Volpon, L; Besson, F; Lancelin, J. NMR structure of active and inactive forms of the sterol-dependent antifungal antibiotic bacillomycin L. Eur. J. Biochem 2001, 264, 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M; Gustafson, K; Cartner, L; Shigematsu, N; Pannell, L; Boyd, M. Microspinosamide, a new HIV-inhibitory cyclic depsipeptide from the marine sponge Sidonops microspinosa1. J. Nat. Prod 2001, 64, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, M. De Vita, VT, Jr, Hellman, S, Rosenberg, SA, Eds.; AIDS Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1988; pp. 305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Valeria D’Auria, M; Zampella, A; Paloma, LG; Minale, L; Debitus, C; Roussakis, C; Le Bert, V. Callipeltins B and C; bioactive peptides from a marine Lithistida sponge Callipelta sp. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 9589–9596. [Google Scholar]

- Zampella, A; D’Auria, M; Paloma, L; Casapullo, A; Minale, L; Debitus, C; Henin, Y. Callipeltin A, an anti-HIV cyclic depsipeptide from the New Caledonian Lithistida sponge Callipelta sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 6202–6209. [Google Scholar]

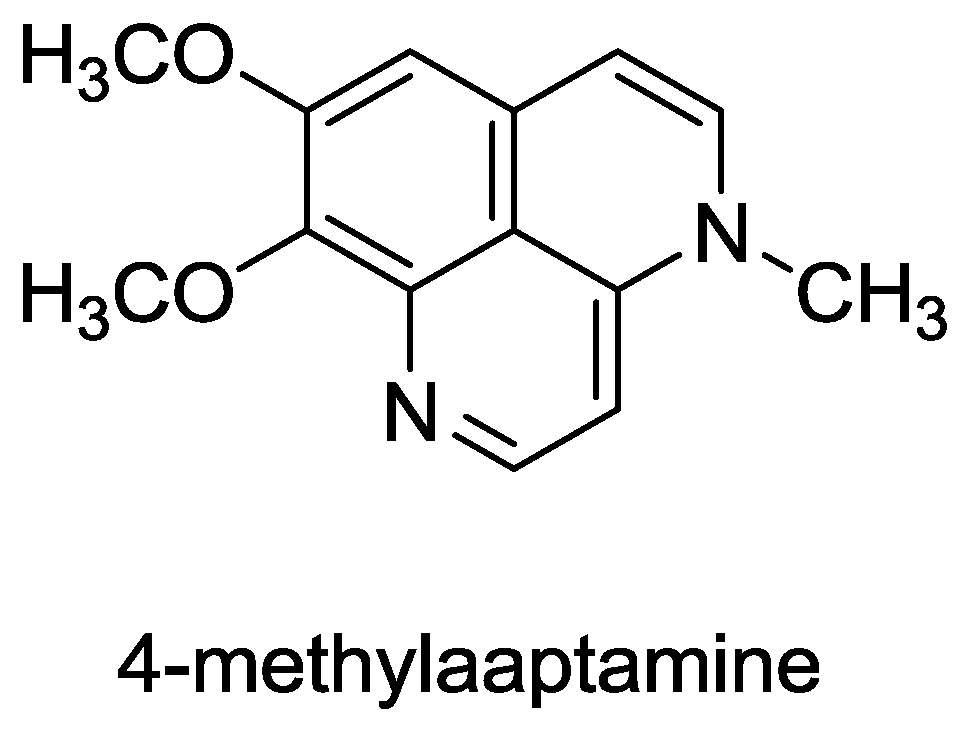

- Coutinho, AF; Chanas, B; e Souza, TML; Frugrulhetti, ICPP; de A Epifanio, R. Anti HSV-1 alkaloids from a feeding deterrent marine sponge of the genus Aaptos. Heterocycles 2002, 57, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, T; Abrantes, J; de A Epifanio, R; Fontes, C; Frugulhetti, I. The Alkaloid 4-Methylaaptamine Isolated from the Sponge Aaptos aaptos Impairs Herpes simplex Virus Type 1 Penetration and Immediate-Early Protein Synthesis. Planta Med 2007, 73, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H; Kobayashi, J; Ohizumi Yoshimasa, Y. Isolation and structure of aaptamine a novel heteroaromatic substance possessing [alpha]-blocking activity from the sea sponge. Tetrahedron Lett 1982, 23, 5555–5558. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, G; Hoffmann, H; Herald, D; McNulty, J; Murphy, A; Higgs, K; Hamel, E; Lewin, N; Pearce, L; Blumberg, P. Antineoplastic agents 491. Synthetic conversion of aaptamine to isoaaptamine, 9-demethylaaptamine, and 4-methylaaptamine. J. Org. Chem 2004, 69, 2251–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, W; Hammond, N; Yousaf, M; Bowling, J; Schinazi, R; Wirtz, S; de Castro Andrews, G; Cuevas, C; Hamann, M. Modification at the C9 position of the marine natural product isoaaptamine and the impact on HIV-1, mycobacterial, and tumor cell activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2006, 14, 8495–8505. [Google Scholar]

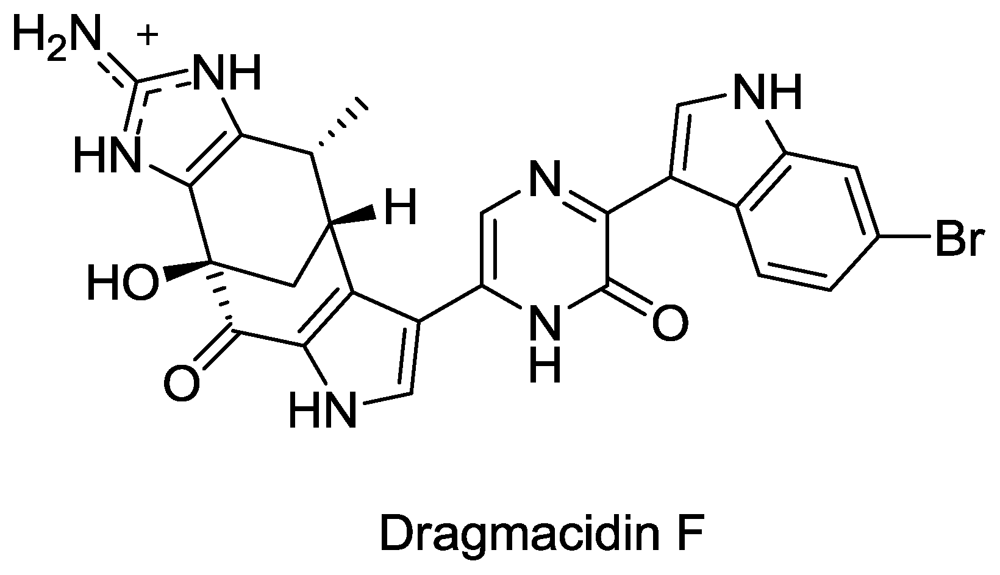

- Cutignano, A; Bifulco, G; Bruno, I; Casapullo, A; Gomez-Paloma, L; Riccio, R. Dragmacidin F: A New Antiviral Bromoindole Alkaloid from the Mediterranean Sponge Halicortex sp. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 3743–3748. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, N; Caspi, D; Stoltz, B. The total synthesis of (+)-dragmacidin F. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 9552–9553. [Google Scholar]

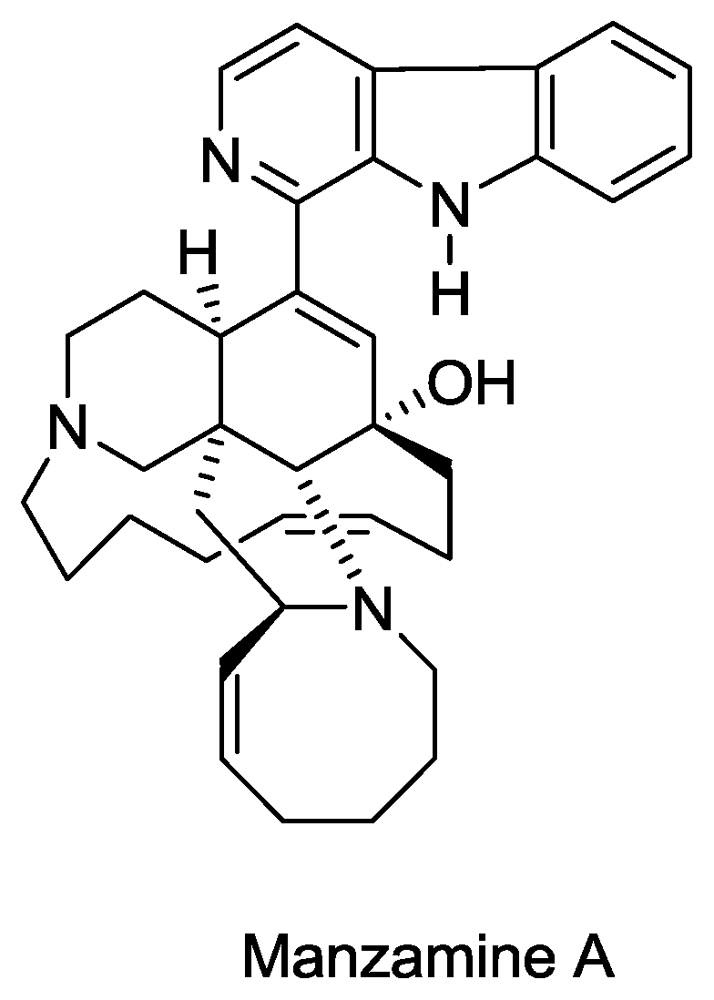

- Sakai, R; Higa, T; Jefford, CW; Bernardinelli, G. Manzamine A, a novel antitumor alkaloid from a sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1986, 108, 6404–6405. [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed, KA; Kelly, M; Kara, UAK; Ang, KKH; Katsuyama, I; Dunbar, DC; Khan, AA; Hamann, MT. New Manzamine Alkaloids with Potent Activity against Infectious Diseases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 1804–1808. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, KV; Santarsiero, BD; Mesecar, AD; Schinazi, RF; Tekwani, BL; Hamann, MT. New Manzamine Alkaloids with Activity against Infectious and Tropical Parasitic Diseases from an Indonesian Sponge. J. Nat. Prod 2003, 66, 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, K; Holmes, M; Higa, T; Hamann, M; Kara, U. In vivo antimalarial activity of the betacarboline alkaloid manzamine A. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 1645. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J; Shen, X; El Sayed, K; Dunbar, D; Perry, T; Wilkins, S; Hamann, M; Bobzin, S; Huesing, J; Camp, R. Marine natural products as prototype agrochemical agents. J. Agric. Food Chem 2003, 51, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J; Rao, K; Choo, Y; Hamann, M. Fattorusso, E, Taglialatela-Scafati, O, Eds.; Manzamine Alkaloids. In Modern Alkaloids: Structure, Isolation, Synthesis and Biology; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2007; pp. 189–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ichiba, T; Corgiat, J; Scheuer, P; Kelly-Borges, M. 8-Hydroxymanzamine A, a beta-carboline alkaloid from a sponge, Pachypellina sp. J. Nat. Prod 1994, 57, 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Edrada, R; Proksch, P; Wray, V; Witte, L; Muller, W; van Soest, R. Four new bioactive manzamine-type alkaloids from the Philippine marine sponge Xestospongia ashmorica. J. Nat. Prod 1996, 59, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, K; Santarsiero, B; Mesecar, A; Schinazi, R; Tekwani, B; Hamann, M. New manzamine alkaloids with activity against infectious and tropical parasitic diseases from an Indonesian sponge. J. Nat. Prod 2003, 66, 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Samoylenko, V; Khan, S; Jacob, M; Tekwani, B; Walker, L; Hufford, C; Muhammad, I. Bioactive (+)-Manzamine A and (+)-Hydroxymanzamine A Tertiary Bases and Salts from Acanthostrongylophora ingens and Their Preparations. Nat. Prod. Commun 2009, 4, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, J; Liao, Y; Ali, A; Rein, T; Wong, Y; Chen, H; Courtney, A; Martin, S. Enantioselective total syntheses of manzamine A and related alkaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 8584–8592. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, M; Hammond, N; Peng, J; Wahyuono, S; McIntosh, K; Charman, W; Mayer, A; Hamann, M. New manzamine alkaloids from an Indo-Pacific sponge. Pharmacokinetics, oral availability, and the significant activity of several manzamines against HIV-I, AIDS opportunistic infections, and inflammatory diseases. J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 3512–3517. [Google Scholar]

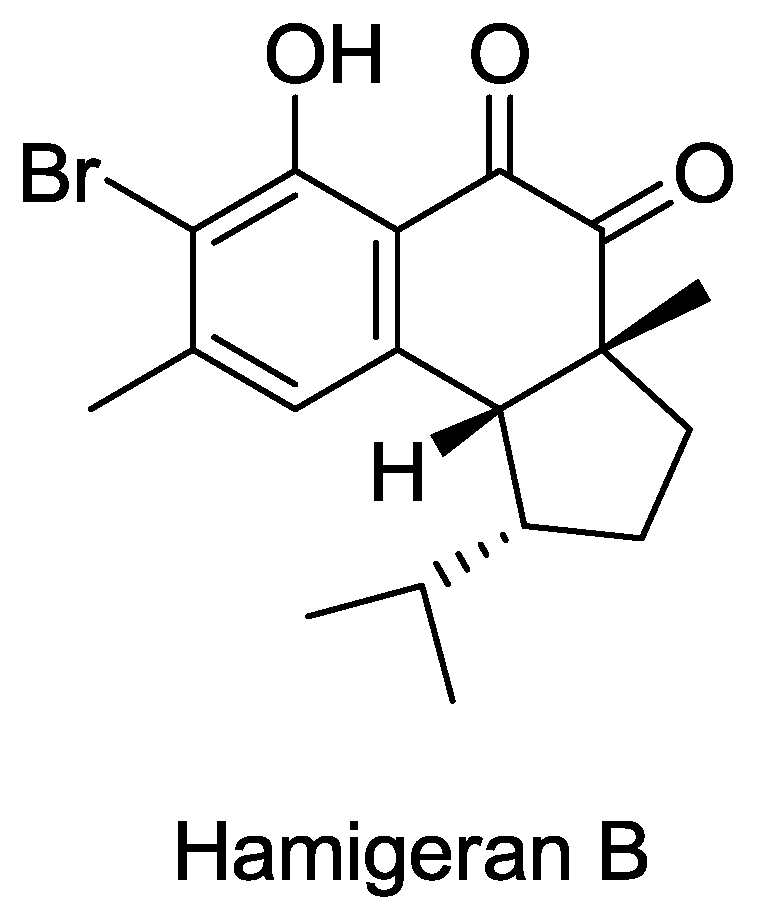

- Clive, DLJ; Wang, J. Stereospecific Total Synthesis of the Antiviral Agent Hamigeran B - Use of Large Silyl Groups to Enforce Facial Selectivity and to Suppress Hydrogenolysis13. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 3406–3409. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, B; Pissot-Soldermann, C; Chen, I; Schroeder, G. An asymmetric synthesis of hamigeran B via a Pd asymmetric allylic alkylation for enantiodiscrimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 4480–4481. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, BM; Pissot-Soldermann, C; Chen, I. A short and concise asymmetric synthesis of hamigeran B. Chemistry 2005, 11, 951–959. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A; Kratz, J; Farias, F; Henriques, A; dos SANTOS, J; Leonel, R; Lerner, C; Mothes, B; Barardi, C; Simões, C. In vitro antiviral activity of marine sponges collected off Brazilian coast. Biol. Pharm. Bull 2006, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Proksch, P; Edrada, R; Ebel, R. Drugs from the seas-current status and microbiological implications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2002, 59, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, J; Lill, R; Hickford, S; Blunt, J; Munro, M. The halichondrins: chemistry, biology, supply and delivery. Drugs Sea 2000, 134–153. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M; Wani, M. Camptothecin and taxol: discovery to clinic—thirteenth Bruce F. Cain Memorial Award Lecture. Cancer Res 1995, 55, 753–760. [Google Scholar]

- Belarbi, E; Gómez, C. Producing drugs from marine sponges. Biotechnol. Adv 2003, 21, 585–598. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, A; Garson, M; Webb, R; Dumdei, E; Charan, R. Cellular origin of chlorinated diketopiperazines in the dictyoceratid sponge Dysidea herbacea (Keller). Cell Tissue Res 1998, 292, 597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, C; Bergquist, P; Harper, M; Faulkner, D; Hooper, J; Haygood, M. Speciation and biosynthetic variation in four dictyoceratid sponges and their cyanobacterial symbiont, Oscillatoria spongeliae. Chem. Biol 2005, 12, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Unson, M; Holland, N; Faulkner, D. A brominated secondary metabolite synthesized by the cyanobacterial symbiont of a marine sponge and accumulation of the crystalline metabolite in the sponge tissue. Mar. Biol 1994, 119, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M; Radax, R; Steger, D; Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2007, 71, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann, R; Graeber, I; Kaesler, I; Szewzyk, U; von Doehren, H. Rapid screening and dereplication of bacterial isolates from marine sponges of the Sula Ridge by intact-cell-MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (ICM-MS). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2005, 67, 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera, A; Sfanos, K; Harmody, D; Pomponi, S; McCarthy, P; Lopez, J. HBMMD: an enhanced database of the microorganisms associated with deeper water marine invertebrates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2005, 66, 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Staley, J; Konopka, A. Measurement of in situ activities of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 1985, 39, 321–346. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, N; Hill, R. The culturable microbial community of the Great Barrier Reef sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile is dominated by an -Proteobacterium. Mar. Biol 2001, 138, 843–851. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, N; Wilson, K; Blackall, L; Hill, R. Phylogenetic diversity of bacteria associated with the marine sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2001, 67, 434. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J; Lord, C; McCarthy, P. Improved recoverability of microbial colonies from marine sponge samples. Microb. Ecol 2000, 40, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Burja, A; Webster, N; Murphy, P; Hill, R. Microbial symbionts of Great Barrier Reef sponges. Mem. Queensl. Mus 1999, 44, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M; Radax, R; Steger, D; Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2007, 71, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A. Farming Sponges to Supply Bioactive Metabolites and Bath Sponges: A Review. Mar. Biotechnol 2009, 11, 669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, M; Martens, D; Wijffels, R. Towards Commercial Production of Sponge Medicines. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 787–802. [Google Scholar]

- Wijffels, R. Potential of sponges and microalgae for marine biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol 2008, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J; Marchesi, J; Dobson, A. Metagenomic approaches to exploit the biotechnological potential of the microbial consortia of marine sponges. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2007, 75, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman, J. Metagenomics: Application of Genomics to Uncultured Microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2004, 68, 669–685. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, TK; Fuerst, JA. Diversity of polyketide synthase genes from bacteria associated with the marine sponge Pseudoceratina clavata: culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Environ. Microbiol 2006, 8, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer, A; Gadkari, R; Reeves, CD; Ibrahim, F; DeLong, EF; Hutchinson, CR. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals Diverse Polyketide Synthase Gene Clusters in Microorganisms Associated with the Marine Sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2005, 71, 4840–4849. [Google Scholar]

- Rachid, S; Krug, D; Kunze, B; Kochems, I; Scharfe, M; Zabriskie, TM; Blöcker, H; Müller, R. Molecular and Biochemical Studies of Chondramide Formation--Highly Cytotoxic Natural Products from Chondromyces crocatus Cm c5. Chem. Biol 2006, 13, 667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Fieseler, L; Horn, M; Wagner, M; Hentschel, U. Discovery of the Novel Candidate Phylum “Poribacteria” in Marine Sponges. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2004, 70, 3724–3732. [Google Scholar]

- Fieseler, L; Quaiser, A; Schleper, C; Hentschel, U. Analysis of the first genome fragment from the marine sponge-associated, novel candidate phylum Poribacteria by environmental genomics. Environ. Microbiol 2006, 8, 612–624. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, F; Ring, M; Perlova, O; Fu, J; Schneider, S; Gerth, K; Kuhlmann, S; Stewart, A; Zhang, Y; Müller, R. Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for methylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis to enable complex heterologous secondary metabolite formation. Chem. Biol 2006, 13, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, S; Gross, F; Zhang, Y; Fu, J; Stewart, A; Müller, R. Heterologous expression of a myxobacterial natural products assembly line in pseudomonads via red/ET recombineering. Chem. Biol 2005, 12, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Khosla, C; Keasling, J. Metabolic engineering for drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2003, 2, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Mutka, S; Carney, J; Liu, Y; Kennedy, J. Heterologous Production of Epothilone C and D in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, J; Marshall, J; Chang, M; Nowroozi, F; Paradise, E; Pitera, D; Newman, K; Keasling, J. High-level production of amorpha-4, 11-diene in a two-phase partitioning bioreactor of metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng 2006, 95, 684–691. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, B; Shah, S. Heterologous expression of epothilone biosynthetic genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 2772. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, B; Khosla, C. Biosynthesis of polyketides in heterologous hosts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2001, 65, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P; Dunlap, W; Battershill, C; Jaspars, M. Shotgun cloning and heterologous expression of the patellamide gene cluster as a strategy to achieving sustained metabolite production. ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S; Chao, C; Clardy, J. New natural product families from an environmental DNA (eDNA) gene cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 9968–9969. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, S; Chao, C; Handelsman, J; Clardy, J. Cloning and heterologous expression of a natural product biosynthetic gene cluster from eDNA. Org. Lett 2001, 3, 1981–1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, D; Brady, S; Bettermann, A; Cianciotto, N; Liles, M; Rondon, M; Clardy, J; Goodman, R; Handelsman, J. Isolation of antibiotics turbomycin A and B from a metagenomic library of soil microbial DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2002, 68, 4301. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, I; Tiong, C; Minor, C; August, P; Grossman, T; Loiacono, K; Lynch, B; Phillips, T; Narula, S; Sundaramoorthi, R. Expression and isolation of antimicrobial small molecules from soil DNA libraries. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2001, 3, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Sipkema, D; Franssen, M; Osinga, R; Tramper, J; Wijffels, R. Marine sponges as pharmacy. Mar. Biotechnol 2005, 7, 142–162. [Google Scholar]

- Piel, J; Hui, D; Wen, G; Butzke, D; Platzer, M; Fusetani, N; Matsunaga, S. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16222. [Google Scholar]

- Sudek, S; Lopanik, N; Waggoner, L; Hildebrand, M; Anderson, C; Liu, H; Patel, A; Sherman, D; Haygood, M. Identification of the putative bryostatin polyketide synthase gene cluster from “Candidatus Endobugula sertula”, the uncultivated microbial symbiont of the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina. J. Nat. Prod 2007, 70, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fortman, JL; Sherman, DH. Utilizing the Power of Microbial Genetics to Bridge the Gap Between the Promise and the Application of Marine Natural Products. ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 960–978. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, MW; Radax, R; Steger, D; Wagner, M. Sponge-Associated Microorganisms: Evolution, Ecology, and Biotechnological Potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 2007, 71, 295–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. Diversity and biotechnological potential of the sponge-associated microbial consortia. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2006, 33, 545–551. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, K; Gurgui, C; Heycke, N; van der Sar, S; Anderson, S; Webb, V; Taudien, S; Platzer, M; Rubio, B; Robinson, S. Polyketide assembly lines of uncultivated sponge symbionts from structure-based gene targeting. Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Hochmuth, T; Piel, J. Polyketide synthases of bacterial symbionts in sponges-Evolution-based applications in natural products research. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1841–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L; An, R; Wang, J; Sun, N; Zhang, S; Hu, J; Kuai, J. Exploring novel bioactive compounds from marine microbes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol 2005, 8, 276–281. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).